Abstract

Objectives:

Gout is a common complication of blood pressure management and a frequently cited cause of medication non-adherence. Little trial evidence exists to inform antihypertensive selection with regard to gout risk.

Methods:

The Antihypertensive and Lipid-Lowering Treatment to Prevent Heart Attack Trial (ALLHAT) was a randomized clinical trial on the effects of first-step hypertension therapy with amlodipine, chlorthalidone, or lisinopril on fatal coronary heart disease or nonfatal myocardial infarction (1994–2002). Trial participants were linked to CMS and VA gout claims (ICD9 274.XX). We determined the effect of drug assignment on gout with Cox regression models. We also determined the adjusted association of self-reported atenolol use (ascertained at the 1-month visit for indications other than hypertension) with gout.

Results:

Claims were linked to 23,964 participants (mean age 69.8±6.8 years, 45% women, 31% black). Atenolol use was reported by 928 participants at the 1-month visit. Over a mean follow-up of 4.9 years, we documented 597 gout claims. Amlodipine reduced the risk of gout by 37% (HR 0.63; 95% CI: 0.51,0.78) compared with chlorthalidone and by 26% (HR 0.74; 95% CI: 0.58,0.94) compared with lisinopril. Lisinopril non-significantly lowered gout risk compared with chlorthalidone (HR 0.85; 95% CI: 0.70,1.03). Atenolol use was not associated with gout risk (adjusted HR 1.18; 95% CI: 0.78,1.80). Gout risk reduction was primarily observed after 1 year of follow-up.

Conclusion:

Amlodipine lowered long-term gout risk compared with lisinopril or chlorthalidone. This finding may be useful in cases where gout risk is a principal concern among patients being treated for hypertension.

Gout is a leading cause of acute, inflammatory arthritis, characterized by severe pain and recurrent flares, that affects over 7.5 million adults in the US.[1] The prevalence of gout is growing, driven in part by the rise of related comorbid conditions, such as obesity and hypertension.[2–4] While diuretic use is a known risk factor for gout,[5] controversy surrounds the role of antihypertensive class in gout risk. Almost all hypertension classes have been associated with gout risk;[6] however, we recently demonstrated that metoprolol (a beta blocker) was associated with a higher risk of gout compared with ramipril and amlodipine. Furthermore, participants assigned ramipril or amlodipine had lower serum uric acid concentrations after 1 year.[7]

The Antihypertensive and Lipid-Lowering treatment to prevent Heart Attack Trial (ALLHAT) was a clinical trial that evaluated the effect of first-step hypertension therapy on fatal coronary heart disease or nonfatal myocardial infarction.[8] ALLHAT compared amlodipine, lisinopril, doxazosin, and chlorthalidone, although the doxazosin arm was ended early due to higher cardiovascular disease (CVD) event rates compared to chlorthalidone. Ultimately, chlorthalidone reduced risk of CVD events compared with amlodipine or lisinopril. In later analyses, ALLHAT investigators linked participants to Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services (CMS) and Veterans Affairs (VA) claims data.[9] However, the relationship between hypertension treatment class and gout claims has not been reported.

In this secondary analysis of ALLHAT, we examined the effect of antihypertensive treatment assignment on gout claims among ALLHAT participants age 65 and older with valid Medicare or Social Security identifiers (required for linkage) during or in extended follow-up after the trial period. We also examined whether self-reported atenolol use was associated with gout during the same period. We hypothesized that chlorthalidone would be associated with a greater risk of gout compared with amlodipine or lisinopril. Based on our prior work, we also hypothesized that atenolol would be associated with a higher risk of gout.[7]

Methods

Study Overview

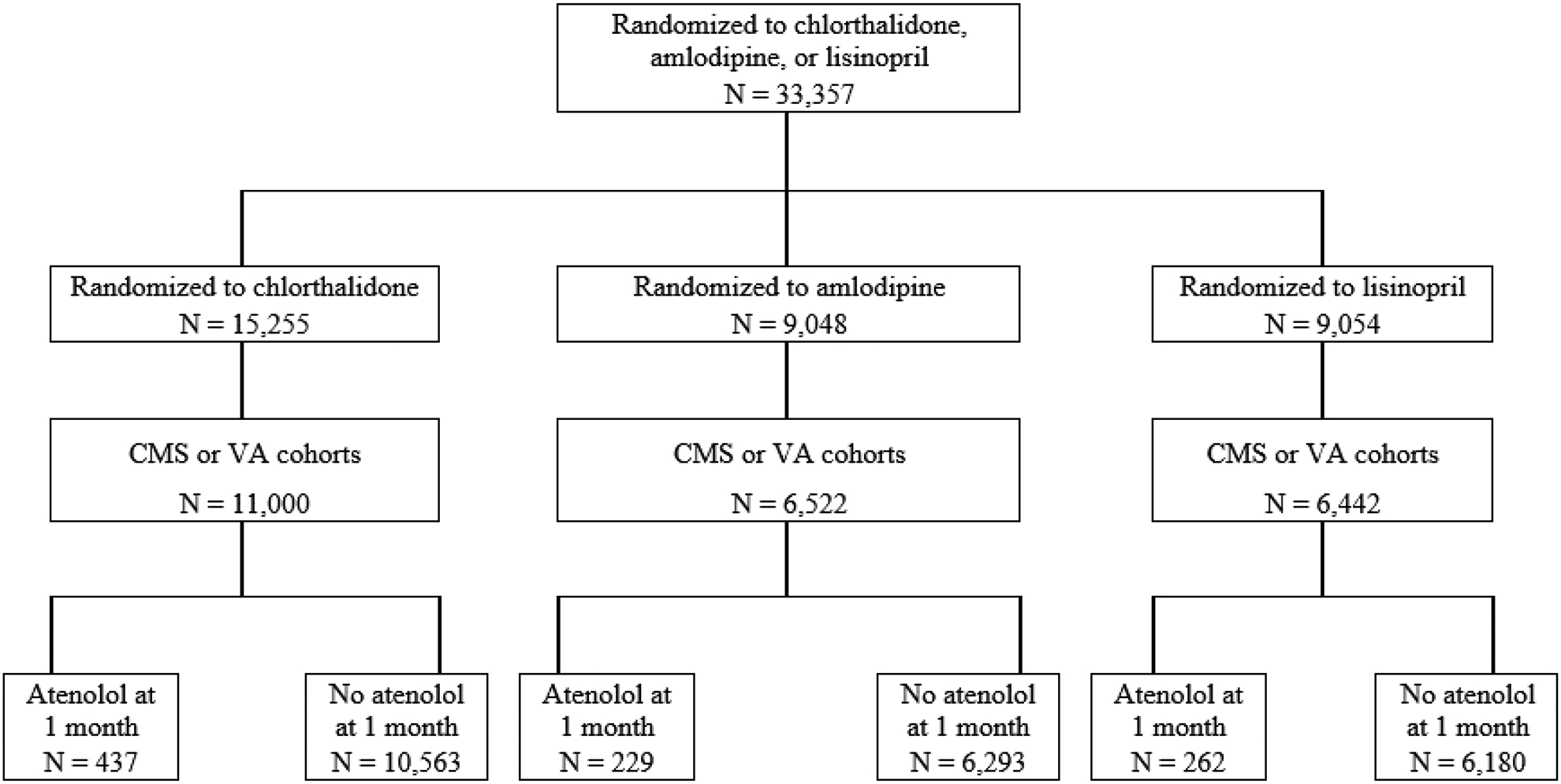

As published previously, ALLHAT was a randomized, double-blind, controlled trial that compared first-step antihypertensive therapies to prevent major CVD outcomes.[8,10] ALLHAT recruited adults age 55 years and older with hypertension and at least 1 risk factor for CHD events (see CONSORT Diagram, Figure 1). The trial was conducted at 623 centers throughout the United States and Canada (1994–1998). Participants were randomly assigned to amlodipine (N=9,048), chlorthalidone (N=15,255), doxazosin (N=9,061), or lisinopril (N=9,054) with trial follow-up through March 2002. However, the doxazosin arm was ended early after observing substantially higher CVD event rates compared to chlorthalidone. After trial completion, participants underwent an extended follow-up phase that ended in 2006 (see CONSORT Diagram, Supplement Figure SF1). Details related to extended follow-up were published previously.[11] Notably there were 5,049 deaths during the trial and 553 Canadian participants excluded from the extension, resulting in 27,755 participants. Among these there were 6,374 deaths post-trial. Monitoring was achieved using national databases (i.e., passive surveillance). The institutional review board (ethics committee) of the University of Texas Health Science Center at Houston and the institutional review boards of each study site approved the initial trial and the extended follow-up. The Beth Israel Deaconess Medical Center institutional review board determined the current analysis was not human subjects research.

Figure 1.

CONSORT diagram of the ALLHAT cohort linked to Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services (CMS) and Veterans Affairs (VA) claims during the in-trial follow-up period

CONSORT diagram for participants randomized to chlorthalidone, amlodipine, or lisinopril from baseline onward, who were in the CMS or VA cohort during the trial follow-up period. Atenolol status was determined during the 1-month visit.

Study Participants

Participation was limited to adults with a systolic blood pressure ≥ 140 mm Hg or diastolic blood pressure ≥ 90 mm Hg and at least one risk factor for coronary heart disease. Coronary heart disease risk factors included previous myocardial infarction, previous stroke, left ventricular hypertrophy, type 2 diabetes, current cigarette smoking, or low high-density lipoprotein cholesterol. Participants with a myocardial infarction, stroke, or angina within 6 months of the study, symptomatic heart failure or ejection fracture < 35%, an elevated serum creatinine (>2 mg/dL), a systolic blood pressure > 180 mm Hg, or a diastolic blood pressure > 110 mm Hg were excluded, as described previously.[8,10] Prior to participation, all participants provided written informed consent.

Study Interventions

In the absence of a safety concern, participants were continued on their antihypertensive regimens until the day they began their randomized study drug. At study entry, each participant was randomized to receive treatment with typically a low dose of 1 of 3 first-line study medications (chlorthalidone, 12.5–25 mg; amlodipine, 2.5–10 mg; or lisinopril, 10–40 mg). Medications were identical in appearance to keep participants masked to drug assignment. Medications were titrated during the first year of the study to achieve the blood pressure goal of systolic blood pressure <140 mm Hg and diastolic blood pressure <90 mm Hg. Visits were scheduled as needed to achieve treatment goals. Following ALLHAT’s original design,[10] if a participant’s blood pressure exceeded the goal despite the maximum dose of the first-line agent, the participant would be started on open label second-line (reserpine, clonidine, atenolol) or third-line (hydralazine) agents. Participants taking atenolol for hypertension prior to study initiation were required to wean off of this treatment as atenolol was a second-line hypertension treatment agent (i.e., atenolol could be started after the maximum dose of the first-line agent was achieved). However, participants on atenolol for reasons other than hypertension prior to study initiation were not required to discontinue it. Since atenolol use was not ascertained at baseline, participants taking atenolol at 1-month were assumed to be taking it at baseline.

Gout

Gout events were based on claims from the CMS and VA hospitalization data (February 1, 1994 through December 31, 2006).[9] Linkage required participants to have valid Medicare or Social Security identifiers; participants without these identifiers were excluded. Participants from Canada or below the age of 65 years at baseline were excluded as they did not have continuous surveillance. While VA data was available for the trial period (1994–2002), it was not available for the post-trial follow-up period (2002–2006). As a result of the VA data not being available after 2002, post-trial analyses were limited to US citizens with Medicare Part A insurance at randomization. Study participants were considered to have gout if claims included an appropriate code (274.XX) based on International Classification of Diseases, Ninth Revision (ICD9). Time to event was based on the minimum follow-up period between baseline and either an event, death, or end of surveillance (administrative censoring). We only included the first gout claim after baseline in all analyses. Recurrent events were not included. Sensitivity analyses were performed, examining both a lagged start by 1 year or a short-term follow-up period that ended 1 year after baseline.

Other Covariates

Population characteristics were documented by trained study personnel following standardized data collection protocols. Demographic characteristics were self-reported (age, sex, black race, Hispanic ethnicity). Auscultatory systolic blood pressure and diastolic blood pressure were measured at baseline after 5 minutes of seated rest. Obesity was defined as a BMI ≥ 30 kg/m2 based on height and weight measurements. Estimated glomerular filtration rate (eGFR) was estimated using the CKD-EPI equation [12] and stage 3–5 chronic kidney disease was defined as an eGFR < 60 ml/min per 1.73 m2. Baseline lipid concentrations were measured using standard assays. History of type 2 diabetes, smoking status (current, former, never), and estrogen use (yes, no) were self-reported. History of CVD (yes, no) was based on self-report or medical records when available.

Statistical Analysis

We reported baseline characteristics as means and proportions across drug assignments and by atenolol use.

We determined the 5-yr cumulative incidence of gout by drug assignment, using Cox regression adjusted for self-reported age, sex, and race (black versus non-black). Kaplan-Meier curves with log-rank tests were used to characterize the cumulative incidence over the following follow-up timeframes: (1) in-trial, (2) in-trial plus extended follow-up period, (3) in-trial lagged by 1-year (to account for a potential latency period), and (4) short-term in-trial with follow-up ending at 1-year (to examine short-term effects).

We determined the relative risks for gout via Cox proportional hazards models. We tested the proportional hazards for treatment by utilizing a time-dependent covariate analysis. For both the in-trial and extension, there was a violation of proportional hazards for the amlodipine versus chlorthalidone and amlodipine versus lisinopril comparisons, wherein there were different hazard ratios for the first year and beyond the first year. As a result, similar to the in-trial analysis, we reported extension findings stratified by 1 year of follow-up.

Models were performed overall and in strata of age (≥75 vs 65–74 years), sex (women, men), race (black, non-black), obesity (BMI >30 vs ≤ 30 kg/m2), history of type 2 diabetes (yes, no), history of CVD (yes, no), stage 3 chronic kidney disease (eGFR < 60 vs ≥ 60 ml/min per 1.73 m2), and baseline estrogen use (yes, no). Differences across strata were evaluated via interaction terms.

We also examined the association between self-reported atenolol use with risk of gout. We determined unadjusted and adjusted cumulative incidence of gout each year up to 5 years by atenolol status. In addition, we determined the unadjusted and age-, sex-, and race-adjusted association of atenolol use with gout using Cox proportional hazard models in strata of drug assignment and overall.

Results

Baseline characteristics

The study population was comprised of 23,964 adults with a mean age at baseline of 69.8 (SD, 6.8) years (Table 1). Participants were 45% women and 31% non-Hispanic black without major differences between randomization arms. There were 928 (3.9%), who reported atenolol use at the 1-month visit. Of note, atenolol use was more common among men, non-Hispanic white participants, and participants with prior CVD.

Table 1.

Baseline characteristics by randomization assignment and by atenolol status, Mean (SD) or %

| Chlorthalidone | Amlodipine | Lisinopril | No Atenolol | Atenolol | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| N=11,000* | N=6,522* | N=6,442* | N=23,036 | N=928 | |

| Age, years | 69.8 (6.8) | 69.8 (6.8) | 69.9 (6.8) | 69.9 (6.8) | 69.1 (6.3) |

| Age ≥ 75 years, % | 23.2 | 23.8 | 24.2 | 23.8 | 19.9 |

| Women, % | 45.1 | 45.5 | 44.2 | 45.2 | 39.9 |

| Race and Ethnicity, % | |||||

| White, non-Hispanic | 49.5 | 50.3 | 49.5 | 48.8 | 71.2 |

| Black, non-Hispanic | 31.1 | 31.3 | 31.0 | 31.8 | 15.0 |

| White Hispanic | 12.0 | 11.5 | 12.3 | 12.1 | 8.0 |

| Black Hispanic | 3.1 | 3.0 | 3.2 | 3.1 | 1.7 |

| Other | 4.4 | 4.0 | 4.1 | 4.2 | 4.1 |

| Systolic blood pressure, mm Hg | 146.6 (15.7) | 146.5 (15.6) | 146.8 (15.6) | 146.5 (15.6) | 149.2 (16.2) |

| Diastolic blood pressure, mm Hg | 83.1 (10.1) | 82.9 (10.1) | 83.0 (10.0) | 83.0 (10.1) | 83.4 (10.3) |

| eGFR, ml/min per 1.73 m2 | 71.3 (17.6) | 71.7 (17.5) | 71.3 (17.6) | 71.5 (17.6) | 69.6 (17.3) |

| eGFR < 60 ml/min per 1.73 m2, % | 25.1 | 23.9 | 25.1 | 24.6 | 29.4 |

| Body mass index, kg/m2 | 29.3 (6.0) | 29.3 (5.9) | 29.3 (5.9) | 29.3 (6.0) | 29.0 (5.6) |

| Obesity, % | 38.9 | 39.0 | 38.8 | 39.0 | 37.7 |

| Type 2 diabetes status, % | 42.6 | 43.0 | 42.2 | 42.9 | 35.5 |

| Prior cardiovascular disease, % | 56.1 | 54.6 | 55.7 | 54.8 | 75.5 |

| HDL cholesterol <35 mg/dL, % | 11.8 | 11.9 | 12.0 | 11.8 | 15.5 |

| Lipid measures, mg/dL | |||||

| Total cholesterol | 215.15 (43.5) | 215.87 (43.8) | 214.10 (41.6) | 215.17 (43.1) | 212.53 (42.8) |

| HDL cholesterol | 46.71 (14.8) | 47.27 (14.9) | 46.53 (14.4) | 46.93 (14.8) | 43.94 (14.1) |

| LDL cholesterol | 135.38 (36.8) | 135.42 (37.2) | 135.28 (35.9) | 135.49 (36.7) | 132.20 (35.9) |

| Smoking Status, % | |||||

| Current | 38.4 | 38.6 | 38.5 | 38.6 | 35.6 |

| Former | 43.1 | 42.5 | 43.2 | 42.7 | 49.5 |

| Never | 18.5 | 18.9 | 18.2 | 18.7 | 15.0 |

| Estrogen use (in women), % | 15.3 | 15.2 | 14.5 | 14.9 | 20.5 |

Reduced denominators (c/a/l) for smoking=11,000/6,521/6,441; BMI/obesity=10,964/6,494/6,422; diabetes=10,222/6,057/5,986; lipids=10,505/6,202/6,116

Abbreviations: HDL, high density lipoprotein; LDL, low density lipoprotein; eGFR, estimated glomerular filtration rate; SD, standard deviation

Effects of Randomized Drug Assignment

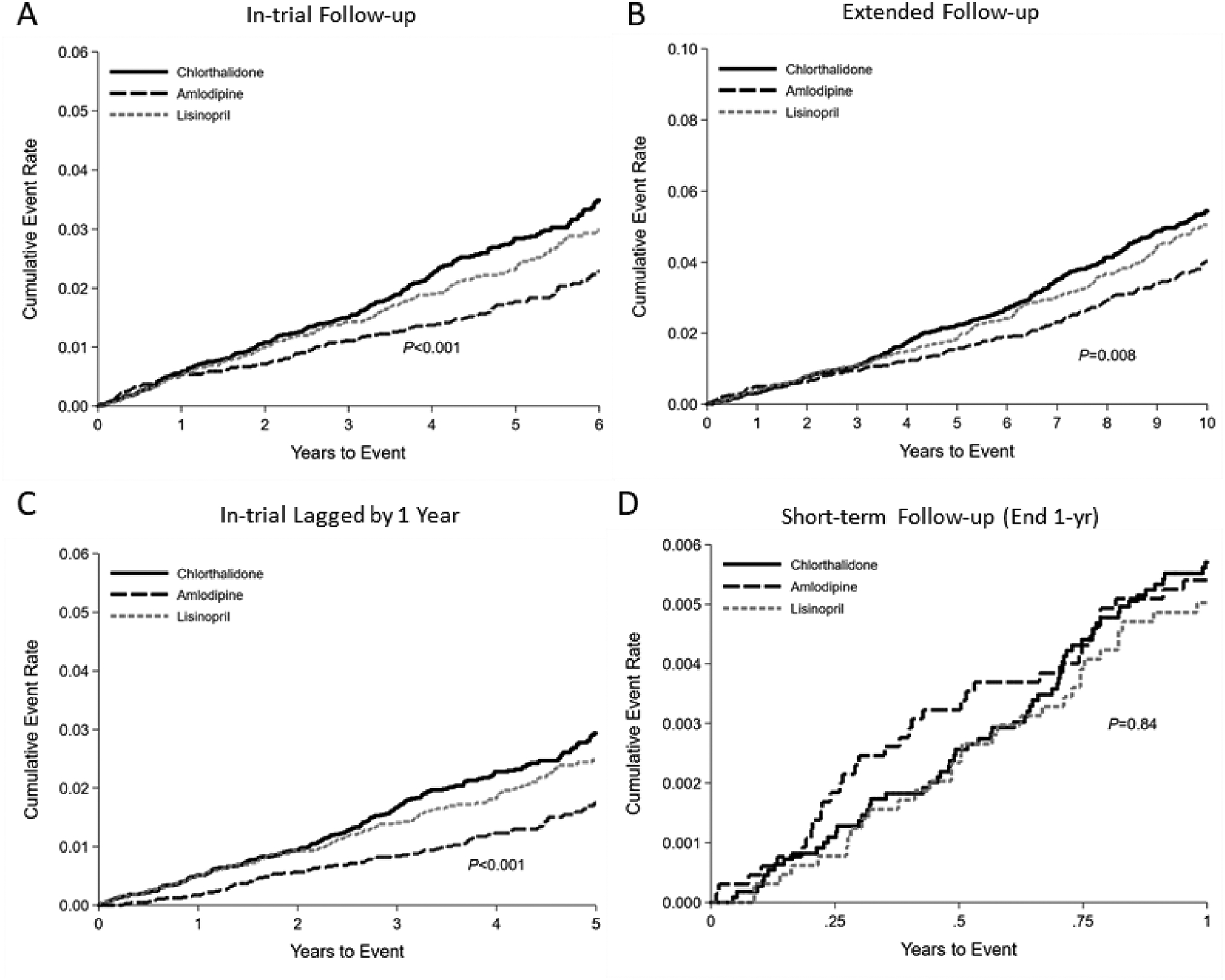

Over a mean of 4.9 years of follow-up, we documented 597 gout claims. The 5-year cumulative incidence of gout adjusted for age, sex, and race was lowest with amlodipine at 1.59 per 100 person-years versus 2.47 per 100 person-years for chlorthalidone and 1.93 per 100 person-years for lisinopril (Supplement Table ST1). This difference in cumulative incidence was observed during the in-trial period as well as with extended follow-up, but not within 1 year of follow-up (Figure 2; Supplement Table ST2).

Figure 2.

Kaplan-Meier cumulative incidence plots of gout during (A) in-trial follow-up, (B) extended follow-up, (C) in-trial follow-up lagged by 1 year, or (D) short-term follow-up, ending at 1-year according to chlorthalidone, amlodipine, or lisinopril assignment.

During the in-trial follow-up period, amlodipine reduced the risk of gout compared to chlorthalidone (HR 0.63; 95% CI: 0.51–0.78) and lisinopril (HR 0.74; 95% CI: 0.58–0.94) (Table 2). These effects were mildly attenuated during extended follow-up, (amlodipine versus chlorthalidone: HR 0.75; 95% CI: 0.63–0.90; amlodipine versus lisinopril: HR 0.82; 95% CI: 0.67–1.00), but stronger when lagged by 1 year (amlodipine versus chlorthalidone: HR 0.55; 95% CI: 0.43–0.71; amlodipine versus lisinopril: HR 0.65; 95% CI: 0.50–0.86). There were no significant differences in gout risk between amlodipine and chlorthalidone or amlodipine and lisinopril within 1 year of follow-up. Furthermore, there were no significant differences in gout risk between chlorthalidone and lisinopril during any follow-up period.

Table 2.

Effect of anti-hypertensive assignment on gout, HR (95% CI)

| Gout (Events/Total) | ||

|---|---|---|

| (597/23,964) | ||

| In-trial | HR (95% CI) | P |

| Amlodipine vs chlorthalidone | 0.63 (0.51–0.78) | <0.001 |

| Lisinopril vs chlorthalidone | 0.85 (0.70–1.03) | 0.10 |

| Amlodipine vs lisinopril | 0.74 (0.58–0.94) | 0.012 |

| Extended follow-up | (763/19,157) | |

| Amlodipine vs chlorthalidone | 0.75 (0.63–0.90) | 0.002 |

| Lisinopril vs chlorthalidone | 0.92 (0.78–1.09) | 0.34 |

| Amlodipine vs lisinopril | 0.82 (0.67–1.00) | 0.051 |

| In-trial lagged by 1-year | (468/23,964) | |

| Amlodipine vs chlorthalidone | 0.55 (0.43–0.71) | <0.001 |

| Lisinopril vs chlorthalidone | 0.85 (0.68–1.05) | 0.12 |

| Amlodipine vs lisinopril | 0.65 (0.50–0.86) | 0.002 |

| Short-term follow-up (end at 1-year) | (129/23,964) | |

| Amlodipine vs chlorthalidone | 0.95 (0.63–1.44) | 0.81 |

| Lisinopril vs chlorthalidone | 0.88 (0.57–1.35) | 0.56 |

| Amlodipine vs lisinopril | 1.08 (0.67–1.74) | 0.76 |

Abbreviations: HR, hazard ratio; CI, confidence interval

Note: These analyses were not adjusted given the randomized design of the trial.

To account for the non-proportional hazards before and after year 1 of the extension, we stratified extension follow-up at year 1. Findings were similar with the in-trial stratified analyses with a stronger protective effect from amlodipine in analyses lagged by 1 year (Supplement Table ST3).

We also examined the effects of drug assignment in strata of age, sex, race, obesity, history of type 2 diabetes, history of CVD, CKD, and estrogen use (Supplement Table ST4). We observed no significant differences across strata.

Effects of Atenolol Use

The cumulative incidence of gout was similar whether or not a participant reported atenolol use at 1-month (Supplement Tables ST5). Similarly, atenolol use was not associated with outcomes overall or within strata of drug assignment (Table 3).

Table 3.

Association of baseline atenolol with gout, HR (95% CI)

| Unadjusted | Age/sex/race Adjusted | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Without atenolol Events/Total | With atenolol Events/Total | HR (95% CI) | P | HR (95% CI) | P | |

| Chlorthalidone | 306/10563 | 12/437 | 1.01 (0.57–1.80) | 0.98 | 1.18 (0.66–2.11) | 0.58 |

| Amlodipine | 116/6293 | 4/229 | 1.03 (0.38–2.78) | 0.96 | 1.10 (0.41–3.00) | 0.85 |

| Lisinopril | 152/6028 | 7/262 | 1.12 (0.53–2.39) | 0.77 | 1.21 (0.56–2.59) | 0.63 |

| Overall | 574/23036 | 23/928 | 1.05 (0.69–1.60) | 0.80 | 1.18 (0.78–1.80) | 0.43 |

Abbreviations: HR, hazard ratio; CI, confidence interval

Note: These analyses are presented unadjusted and adjusted for age, sex, and race/ethnicity as atenolol was not a randomized medication.

Discussion

In this secondary analysis of the ALLHAT study, amlodipine treatment significantly lowered the risk of gout compared with either chlorthalidone or lisinopril. These findings were consistent regardless of baseline characteristics and suggest a potential clinical benefit of this agent (and possibly calcium channel blockers in general) for blood pressure management in patients at risk for gout. Notably, effects were strongest beyond 1 year of follow-up.

The higher risk of gout among participants assigned chlorthalidone is consistent with prior reports.[5,6,13] Thiazide diuretics are known to promote uric acid reabsorption in the proximal tubule,[14] and in one community-based cohort, initiation of thiazide medications was associated with an increase in uric acid of over 0.5 mg/dL over a 3-year period.[5] This excess uric acid contributes to increased development of gout as well as increased frequency of gout flares.[5,15,16]

In our study, assignment to amlodipine was associated with lower gout risk than assignment to lisinopril. This was unexpected. In the AASK trial, we previously demonstrated that both amlodipine and ramipril treatment were associated with lower uric acid, but only ramipril was associated with lower odds of subsequent gout medication use.[7] However, in AASK, the amlodipine arm was stopped prematurely due to inferiority with regards to the primary outcome (progression of kidney disease, incident end stage renal disease, or death). This may account for the lack of association with gout risk in that trial. Similar associations between calcium channel blockers and uric acid have been described.[6,17–21] Calcium channel blockers may inhibit uric acid reabsorption by the URAT1 transporter, causing uricosuria.[18,22,23] Whether amlodipine reduces uric acid or gout flares in populations with established gout represents an important topic for further study.

Baseline atenolol use was not associated with gout risk in ALLHAT. Based on prior work, we predicted that atenolol use would be associated with a higher risk of gout, which was not the case.[7] This could be due in part to other baseline covariates related to atenolol use as atenolol use was not one of the randomized assignments in ALLHAT. Chance may also have played a role, as the number of participants reporting atenolol use was substantially lower than the number assigned to the three primary arms. In AASK, the beta blocker metoprolol was associated with higher uric acid levels measured at the 1-year follow-up visit and a higher risk of long-term gout medication use.[7] Beta blockers have been associated with higher uric acid levels in other studies as well.[21,24,25] Future research is needed to elucidate the apparently different findings observed in ALLHAT and AASK trials.

This study has several limitations. First, events were based on gout claims, which were not available at baseline. In addition, gout history was not assessed at baseline. As a result, the claims identified in our study likely include both participants with no prior history of gout and participants with prior gout. Furthermore, while claims have been shown to be specific, they are insensitive, often representing more severe disease.[26] A lack of less severe events could attenuate our findings. Second, baseline alcohol consumption was not assessed in ALLHAT. Alcohol is a risk factor for both elevated BP and gout. Third, uric acid levels were not measured and we did not have data on urate-lowering therapy, which could also represent a means of ascertaining gout risk (i.e., number on gout treatment). Fourth, our study did not include a randomized assignment of a beta blocker and did not study losartan, which has been shown to have uricosuric effects.[27] Similarly, other common drugs within classes of calcium channel blockers, diuretics, and angiotensin-converting enzyme inhibitors were not included. As a result, we are unable to definitively compare the effects of these commonly used medications on gout risk. Fifth, hazards were not proportional over time and imply that effects on gout may be delayed by 1 year. This is consistent with previous reports suggesting that at least 1 year of urate-lowering therapy is needed to observe an effect on gout flares.[28]

This study has multiple strengths. First, ALLHAT is the largest, randomized trial of antihypertensive class on long-term outcomes, allowing for a robust comparison between antihypertensive agents in over 20,000 participants. Second, ALLHAT included a diverse population of participants with hypertension throughout the U.S., increasing generalizability. Third, we used gout claims as our events, ensuring that all our findings reflect clinically relevant outcomes that impacted the health system even if the least severe were not captured.

Our study is clinically relevant. The prevalence of gout has been rising in the US.2–4 With the introduction of the AHA/ACC hypertension management guidelines,[29] the number of Americans meeting diagnosis thresholds for hypertension has doubled. Given the role of thiazide diuretics among first-line therapies for BP management, we expect that gout prevalence will continue to rise in the U.S. Current gout management guidelines emphasize avoiding diuretics and using losartan, a uricosuric antihypertensive, for treatment of hypertension in patients with gout.[30] However, our study demonstrates a role for calcium channel blockers, specifically amlodipine, in lowering gout risk. While our study was not limited to patients with gout, our findings suggest the potential for substantial reduction of suffering by use of amlodipine in this population. Our study also suggests a potential role of calcium channel blockers for the prevention of gout flares in hypertension populations. Nevertheless, given the primary ALLHAT benefits from chlorthalidone for CVD prevention, the gout prevention benefits observed in our study should be weighed carefully against the benefits of CVD risk reduction, particularly among those with higher risk of CVD events.

In conclusion, our study demonstrated that amlodipine was associated with a lower risk of gout compared with chlorthalidone or lisinopril, which has never been reported prior to this study. These findings suggest that amlodipine may be the most effective agent among those studied in ALLHAT for lowering gout risk. However, other outcomes, such as heart failure, should also be considered when choosing a BP drug. Further research is needed to confirm these findings and to evaluate this medication specifically in a population with both hypertension and gout.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgements

SPJ supported by a NIH/NHLBI K23HL135273.

Abbreviations used:

- ALLHAT

Antihypertensive and Lipid-Lowering Treatment to Prevent Heart Attack Trial

- BP

blood pressure

- SBP

systolic blood pressure

- DBP

diastolic blood pressure

- HR

heart rate or hazard ratio

- OR

odds ratio

- CI

confidence interval

Footnotes

This trial is registered at clinicaltrials.gov: NCT00000542

Conflicts of interest

The authors have no conflicts of interest to report.

References

- 1.Juraschek SP, Kovell LC, Miller ER, Gelber AC. Gout, urate-lowering therapy, and uric acid levels among adults in the United States. Arthritis Care Res (Hoboken) 2015; 67:588–592. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Juraschek SP, Miller ER, Gelber AC. Body mass index, obesity, and prevalent gout in the United States in 1988–1994 and 2007–2010. Arthritis Care Res (Hoboken) 2013; 65:127–132. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Lim SY, Lu N, Oza A, Fisher M, Rai SK, Menendez ME, et al. Trends in Gout and Rheumatoid Arthritis Hospitalizations in the United States, 1993–2011. JAMA 2016; 315:2345–2347. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Zhu Y, Pandya BJ, Choi HK. Prevalence of gout and hyperuricemia in the US general population: the National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey 2007–2008. Arthritis Rheum 2011; 63:3136–3141. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.McAdams DeMarco MA, Maynard JW, Baer AN, Gelber AC, Young JH, Alonso A, et al. Diuretic use, increased serum urate levels, and risk of incident gout in a population-based study of adults with hypertension: the Atherosclerosis Risk in Communities cohort study. Arthritis Rheum 2012; 64:121–129. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Choi HK, Soriano LC, Zhang Y, Rodríguez LAG. Antihypertensive drugs and risk of incident gout among patients with hypertension: population based case-control study. BMJ 2012; 344:d8190. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Juraschek SP, Appel LJ, Miller ER. Metoprolol Increases Uric Acid and Risk of Gout in African Americans With Chronic Kidney Disease Attributed to Hypertension. Am J Hypertens 2017; 30:871–875. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.ALLHAT Officers and Coordinators for the ALLHAT Collaborative Research Group. The Antihypertensive and Lipid-Lowering Treatment to Prevent Heart Attack Trial. Major outcomes in high-risk hypertensive patients randomized to angiotensin-converting enzyme inhibitor or calcium channel blocker vs diuretic: The Antihypertensive and Lipid-Lowering Treatment to Prevent Heart Attack Trial (ALLHAT). JAMA 2002; 288:2981–2997. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Puttnam R, Davis BR, Pressel SL, Whelton PK, Cushman WC, Louis GT, et al. Association of 3 Different Antihypertensive Medications With Hip and Pelvic Fracture Risk in Older Adults: Secondary Analysis of a Randomized Clinical Trial. JAMA Intern Med 2017; 177:67–76. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Davis BR, Cutler JA, Gordon DJ, Furberg CD, Wright JT, Cushman WC, et al. Rationale and design for the Antihypertensive and Lipid Lowering Treatment to Prevent Heart Attack Trial (ALLHAT). ALLHAT Research Group. Am J Hypertens 1996; 9:342–360. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Cushman WC, Davis BR, Pressel SL, Cutler JA, Einhorn PT, Ford CE, et al. Mortality and morbidity during and after the Antihypertensive and Lipid-Lowering Treatment to Prevent Heart Attack Trial. J Clin Hypertens (Greenwich) 2012; 14:20–31. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Levey AS, Stevens LA, Schmid CH, Zhang YL, Castro AF, Feldman HI, et al. A new equation to estimate glomerular filtration rate. Ann Intern Med 2009; 150:604–612. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Hueskes BAA, Roovers EA, Mantel-Teeuwisse AK, Janssens HJEM, van de Lisdonk EH, Janssen M. Use of diuretics and the risk of gouty arthritis: a systematic review. Semin Arthritis Rheum 2012; 41:879–889. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Hagos Y, Stein D, Ugele B, Burckhardt G, Bahn A. Human renal organic anion transporter 4 operates as an asymmetric urate transporter. J Am Soc Nephrol 2007; 18:430–439. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Bruderer S, Bodmer M, Jick SS, Meier CR. Use of diuretics and risk of incident gout: a population-based case-control study. Arthritis & Rheumatology (Hoboken, NJ) 2014; 66:185–196. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Hunter DJ, York M, Chaisson CE, Woods R, Niu J, Zhang Y. Recent diuretic use and the risk of recurrent gout attacks: the online case-crossover gout study. J Rheumatol 2006; 33:1341–1345. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Saruta T, Ogihara T, Saito I, Rakugi H, Shimamoto K, Matsuoka H, et al. Comparison of olmesartan combined with a calcium channel blocker or a diuretic in elderly hypertensive patients (COLM Study): safety and tolerability. Hypertens Res 2015; 38:132–136. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.An G, Liu W, Duan WR, Nothaft W, Awni W, Dutta S. Population pharmacokinetics and exposure-uric acid analyses after single and multiple doses of ABT-639, a calcium channel blocker, in healthy volunteers. AAPS J 2015; 17:416–426. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Ruilope LM, Kirwan B-A, de Brouwer S, Danchin N, Fox KAA, Wagener G, et al. Uric acid and other renal function parameters in patients with stable angina pectoris participating in the ACTION trial: impact of nifedipine GITS (gastro-intestinal therapeutic system) and relation to outcome. J Hypertens 2007; 25:1711–1718. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Miyazaki S, Hamada T, Hirata S, Ohtahara A, Mizuta E, Yamamoto Y, et al. Effects of azelnidipine on uric acid metabolism in patients with essential hypertension. Clinical and Experimental Hypertension 2014; 36:447–453. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Chanard J, Toupance O, Lavaud S, Hurault de Ligny B, Bernaud C, Moulin B. Amlodipine reduces cyclosporin-induced hyperuricaemia in hypertensive renal transplant recipients. Nephrol Dial Transplant 2003; 18:2147–2153. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Hori T, Ouchi M, Otani N, Nohara M, Morita A, Otsuka Y, et al. The uricosuric effects of dihydropyridine calcium channel blockers in vivo using urate under-excretion animal models. J Pharmacol Sci 2018; 136:196–202. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Sugino H, Shimada H. A Comparison of the Uricosuric Effects in Rats of Diltiazem and Derivatives of Dihydropyridine (Nicardipine and Nifedipine). JpnJPharmacol 1997; 74:29–36. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Adverse reactions to bendrofluazide and propranolol for the treatment of mild hypertension. Report of Medical Research Council Working Party on Mild to Moderate Hypertension. Lancet 1981; 2:539–543. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Andersen GS. Atenolol versus bendroflumethiazide in middle-aged and elderly hypertensives. Acta Med Scand 1985; 218:165–172. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.MacFarlane LA, Liu C-C, Solomon DH, Kim SC. Validation of claims-based algorithms for gout flares. Pharmacoepidemiol Drug Saf 2016; 25:820–826. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Würzner G, Gerster JC, Chiolero A, Maillard M, Fallab-Stubi CL, Brunner HR, et al. Comparative effects of losartan and irbesartan on serum uric acid in hypertensive patients with hyperuricaemia and gout. J Hypertens 2001; 19:1855–1860. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Becker MA, MacDonald PA, Hunt BJ, Lademacher C, Joseph-Ridge N. Determinants of the clinical outcomes of gout during the first year of urate-lowering therapy. Nucleosides Nucleotides Nucleic Acids 2008; 27:585–591. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Whelton PK, Carey RM, Aronow WS, Casey DE, Collins KJ, Himmelfarb CD, et al. 2017 ACC/AHA/AAPA/ABC/ACPM/AGS/APhA/ASH/ASPC/NMA/PCNA Guideline for the Prevention, Detection, Evaluation, and Management of High Blood Pressure in Adults: Executive Summary: A Report of the American College of Cardiology/American Heart Association Task Force on Clinical Practice Guidelines. Hypertension 2017; :HYP.0000000000000066. [Google Scholar]

- 30.Zhang W, Doherty M, Bardin T, Pascual E, Barskova V, Conaghan P, et al. EULAR evidence based recommendations for gout. Part II: Management. Report of a task force of the EULAR Standing Committee for International Clinical Studies Including Therapeutics (ESCISIT). Ann Rheum Dis 2006; 65:1312–1324. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.