Dear Sir,

The global health pandemic with COVID-19 has hugely impacted the international health community causing significant disruption to routine clinical practices as well as teaching and training. The speed and scale of viral spread have overwhelmed health services across the globe and has required diversion of all clinical resources to save lives and protect health care workers. Redeployment of trainees into medical specialities has virtually halted their training within chosen subspecialties.

Within a few weeks, COVID-19 has forced the surgical community to rapidly adapt to a completely new way of delivering care. Guidelines for the treatment of acute conditions and oncology patients are being re-evaluated. Moreover, each procedure that takes place is being evaluated with regards to potential for both patients and practitioners. COVID-19 has truly changed the way that surgeons of all specialties think, practice and operate.

In these unprecedented times, it is a challenge to facilitate standard teaching and training modules. As it became imperative to maintain social distancing in order to achieve victory over this pandemic, the use of webinars has gained massive popularity within multiple healthcare domains. The General Medical Council (GMC) in setting out the principles for good medical practice, recognises the importance of continuous professional development in order to maintain and develop performance and skills.1 Within this pandemic, it has become imperative that trainees and healthcare professionals are kept engaged within their specialities. From basic telehealth platforms to more complex augmented reality solutions, technology is increasingly being deployed to foster connectivity between surgical teams in order to disseminate best practice and share expertise on a global scale.

Webinars and virtual collaboration platforms, allow the advantage of face to face learning with an interactive exchange in real-time. In addition to this, sufficient learning tools can be provided for a large number of learners, multiple chat functions like live quiz and polls offer helpful learning modalities. Current literature demonstrates that webinars are a reliable tool to deliver a near-normal interaction between the audience and the lecturer.2 , 3 Under normal circumstances, virtual learning is often underutilised since humans are sociable and enjoy a person to person interaction more. However, these virtual environments allow for synchronous sessions which enable the trainer and trainee to share ideas and questions in real-time, located anywhere in the world. The wide variety of webinars available online have provided a new level of convenience in medical education, where learners can engage in gaining education on a platform where online availability can be incorporated easily even within the time constraints of regular working days. Over the past five weeks, we have observed an influx of online teaching modules. The benefits of these sessions are clear; they provide a platform wherein the comfort of the trainee's home; they have access to world-class surgeons providing teaching in real-time. This traditionally was only available if one were to attend a meeting, which in itself is associated with an expense.

We have converted our regular inhouse teaching by utilising video communication through platforms, Zoom, and virtual collaboration and augmented reality platforms, Proximie. The teaching schedule is designed to complement the curriculum for plastic surgery training and address the hot topics caused by the Covid-19 pandemic. Initial feedback from trainees has been extremely positive and judging through the attendance rates at webinars throughout the country we believe this trend of online learning is here to stay.

In our experience, online teaching has provided an easily accessible resource of teaching that is available to use when convenient. This is especially true for many surgeons that adapted to a new work schedule and were redeployed to help in other clinical areas such as intensive care setting resulted in an unpredictable timetable. Furthermore, this form of teaching has provided a break in the physical barriers to training and encouraged interaction in a way that seems more favourable to participants.4 Feedback surveys show a high satisfaction rate from participants. Also, trainees were able to comment on improvement in morale as redeployment to other specialities caused certain anxiety regarding training. Keeping trainees engaged with the speciality is also vital in this time of uncertainty.

Historically, the most common challenges faced during the utilisation of electronic platforms to deliver virtual learning were the technical challenges.5 However, owing to advances in technology and internet connection. High-quality video and sound have been maintained throughout the sessions. Security concerns were raised with platforms like Zoom even with password protection. Though some of the concerns have been addressed it is important to bear this in mind and not share confidential information on these platforms and ensure that your software is frequently updated.

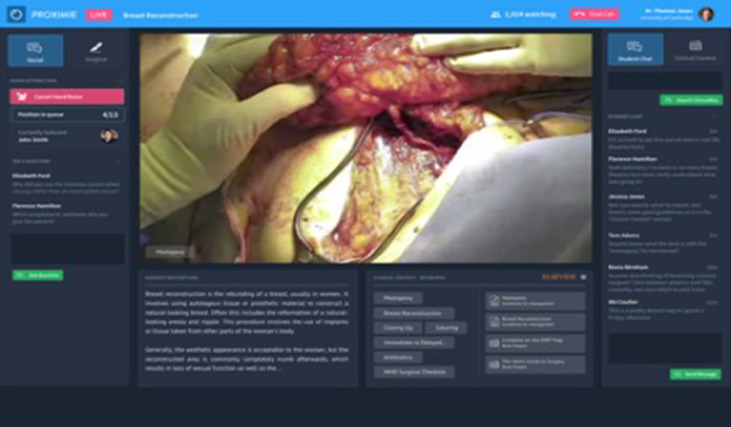

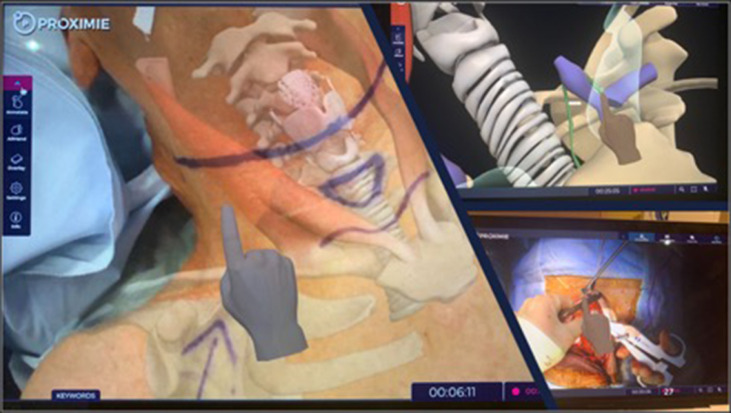

In summary, virtual learning utilising webinars has enabled continuous professional development in our unit and others across the world. In our experience, webinars are highly efficient, flexible and allow surgeons in training to access learning material from a wide geographic area ensuring at the same time, compliance with the social distancing guidance. Online teaching has globalised teaching in pure form and in the future, may replace face-to-face lectures (Figure 1, Figure 2 ).

Figure 1.

Use of video communication for live dial in to the operating room, free tissue transfer surgery in this case.

Figure 2.

Cadaveric Masterclass demonstrating use of virtual platforms in practical learning, display of practical tracheostomy teaching.

References

- 1.Good Medical Practice (2013). [online] Available at: <http://www.gmc-uk.org/guidance/good_medical_practice.asp>[Accessed 28/04/2020].

- 2.Wang S.K., Hsu H.Y. Use of the webinar tool (Elluminate) to support training: the effects of webinar-learning implementation from student-trainers’ perspective. J Interact Online Learn. 2008;7(3):175–194. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Cornelius S. Facilitating in a demanding environment: experiences of teaching in virtual classrooms using web conferencing. Br J Edu Technol. 2013;45(2):260–271. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Gegenfurtner A., Schwab N., Ebner C. There's no need to drive from A to B”: exploring the lived experience of students and lecturers with digital learning in higher education. Bavarian J Appl Sci. 2018;4:310–322. doi: 10.25929/bjas.v4i1.50. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Johnson C., Corazzini K., Shaw R. Assessing the feasibility of using virtual environments in distance education knowledge management & E-Learning. Int J. 2011:5–16. https://www.gmc-uk.org/-/media/documents/good-medical-practice---english-20200128_pdf. [Google Scholar]