Abstract

The present study evaluated the in vitro efficacy of miltefosine against cysts of Acanthamoeba spp. belonging to genotypes T3, T4 and T5. Each genotype was incubated with miltefosine at the concentration of 2.42, 4.84, 9.68, 19.36, 38.72 and 77.44 mM for different periods; 1, 3, 5, 7 d at 37 °C. The viability was assessed by staining with 0.4% trypan blue and culturing on NNA medium at 30 °C for 1 month. The results showed 100% eradication of cyst stage of all concentrations, but exhibited a different degree of activity against different genotypes. The MCC of 38.72 mM could kill genotype T4 and T5 after 1 d of incubation, whereas the killing of T3 needed MCC of 77.44 mM at the same incubation time. Miltefosine showed statistically highly significant difference (P < 0.001) in comparison to non-treated control. Although our finding needs to confirm in animal models, this information may be the guideline for optimizing therapy or considered to combine with the other drugs for effective treatment.

Keywords: Acanthamoeba cyst, Miltefosine, Genotypes, Minimal cysticidal concentration

Free-living Acanthamoebae are known to be a causative agent of chronic granulomatous amoebic encephalitis (GAE) and disseminating diseases in immunodeficient individuals and Acanthamoeba keratitis (AK) in immunocompetent individuals (Siddiqui and Khan 2012). Acanthamoeba spp. have been placed into three groups (I, II and III) based on cyst size and shape (Pussard and Pons 1977). However, these criteria have proved unreliable because culture conditions can change cyst morphology (Sawyer and Griffin 1975). Based on 18S rRNA gene sequencing, Acanthamoeba spp. were then classified into 20 different genotypes, T1–T20 (Fuerst et al. 2015). As its abundance, various genotypes of Acanthamoeba are accounted for pathogen including T3, T4, and T5 (Siddiqui and Khan 2012). Genotype T4 is the most commonly isolated in both clinical and environmental samples, and the second most prevalence are genotype T3 and T5 (Ledee et al. 2009). The amoeba’s virulence is related to its genotype and the most virulent is genotype T4 because it has higher potential of binding to host cells than other genotypes (Maghsood et al. 2005). However, previous study had reported that genotype T3 can cause damage on brain microvascular endothelial cells similarly to genotype T4 (Alsam et al. 2003). The treatment of Acanthamoeba keratitis is challenging and the delay of the treatment could lead to blindness. At present, the first-line treatment for AK is the combination therapy of biguanides and diamidines in order to avoid resistant and persistent infection (Carrijo-Carvalho et al. 2017). For treatment of GAE and disseminated amoebic diseases, the mixture of antimicrobial agents is mostly used, but the outcome is rarely successful (Marciano-Cabral et al. 2000). Previous study showed the efficacy of miltefosine for 100% killing of trophozoite with the various degree of effect on different Acanthamoeba strains while cysts were less sensitive and could not achieve complete killing (Mrva et al. 2011; Walochnik et al. 2002). The eradication of Acanthamoeba from the infection site is difficult because under adverse conditions, the amoebas encyst which makes it highly resistant to anti-amoebic drugs. To the best of our knowledge, cysticidal concentration for 100% eradication of miltefosine has not been reported. Therefore, this study aimed to investigate the effective concentration of miltefosine for complete eradication of cyst stage of three Acanthamoeba isolates belonging to genotype T3, T4 and T5 in order to help for clinical practice guidelines.

Materials and methods

In the present study, cysticidal activity of miltefosine was tested on cysts of three Acanthamoeba environmental isolates: T3 (KT897271), T4 (KT897265), and T5, (KT897268) genotypes (Thammaratana et al. 2016). Mature cysts of each isolate were prepared by culturing on 1.5% non-nutrient agar (NNA) seeded with 5 µL of heat-killed Escherichia coli and incubated at 30 °C for 3 weeks. The cysts were harvested, washed in phosphate-buffered saline (PBS) and then treated with 0.5% sodium dodecyl sulfate (SDS) to lyse non-mature cysts, then standardized to be 20 × 104 cysts/mL. Each calibrated amoeba strain was incubated with miltefosine (Sigma, MO, USA) at concentrations; 2.42, 4.84, 9.68, 19.36, 38.72 and 77.44 mM except untreated control tubes, which had only pure phosphate buffer and incubated at 37 °C for 1, 3, 5, and 7 d. In addition, a reference drug control was cysts treated with 0.02% chlorhexidine (Sigma-Aldrich, USA) and incubated under the same conditions. Chlorhexidine [0.02% (0.04 mM)] is expected to kill all cysts/trophozoites. Following incubation, the viability of cysts was determined by staining with 0.4% trypan blue any unstained cyst is viable and stained is non-viable, and then counted for eliminated cysts. All treated samples were also confirmed by culturing on 1.5% NNA medium, incubated at 30 °C for 1 month. The lowest concentration of the miltefosine that exhibits no viable cysts was defined as the minimal cysticidal concentration (MCC). The experiments were carried out at four independent experiments, each in triplicate. Data analysis were made by using SPSS version 19.0 for Windows. Cyst number was calculated as mean ± SD and percent of eliminated cyst. The mean number were analyzed by using ANOVA followed by the Tukey test for post hoc comparisons.

Results and discussion

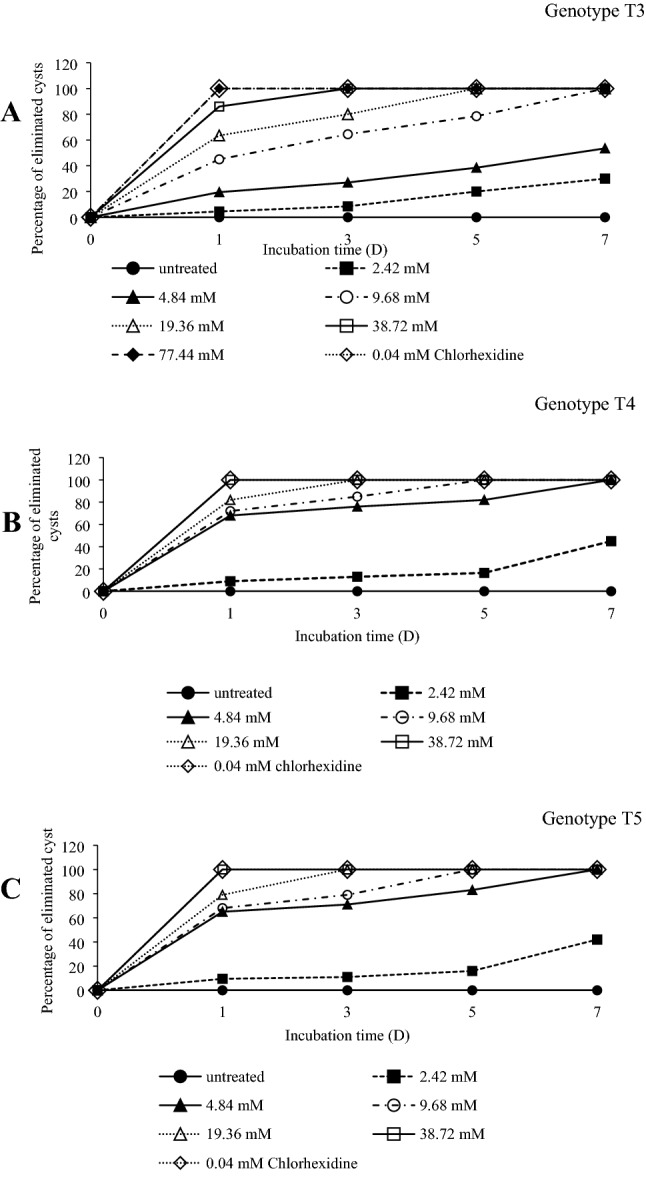

After 7 d of incubation, the PBS control samples of Acanthamoeba spp. of genotypes T3, T4, and T5 contained 19.4 × 104, 19.2 × 104and 19.4 × 104 cells/mL, respectively.For drug control cultures (chlorhexidine), no viable cysts were presented in any genotype at any incubation Time-Point. All tested concentrations of miltefosine can inhibit cyst survival, but exhibited a different degree of activity against different genotypes. The results of eliminated cyst are shown in Fig. 1, and mean number of cysts (mean ± SD) after exposure to drugs are shown in Table 1. Miltefosine showed statistically highly significant difference (P < 0.001) in comparison to non-treated control. The MCC of miltefosine for killing of T4 and T5 after 1 d was 38.72 mM. The MCC for these phenotypes after 3, 5, and 7 d decreased to 19.36, 9.68 and 4.84 mM, respectively. For killing of T3, MCC after 1 d was 77.44 mM and after 3, 5 and 7 d were 38.72, 19.68 and 9.68 mM, respectively. A complete eradication of cysts of genotype T4 and T5 after 1 d was recorded at concentration 38.72 mM and for killing of genotype T3 was at concentration 77.44 mM (Table 1). The altered morphology with cytoplasm destruction after 1 d of incubation with miltefosine of all genotypes are shown in Fig. 2. In untreated cyst of amoeba, the plasma membrane was lined along with the endocystic wall and the double-walled was well shown (Fig. 2a–c). In treated cysts, the separation of plasma membrane from cyst wall and swelling of cyst wall were observed, but more prominent in T4 genotype (Fig. 2e). The cytoplasm contents were aggregated and severely depleted were observed in all genotypes (Fig. 2d–f).

Fig. 1.

Percentage of eliminated cysts of Acanthamoeba species after exposure to miltefosine with various concentrations and incubated at different period. aAcanthamoeba genotype T3; bAcanthamoeba genotype T4 and cAcanthamoeba genotype T5

Table 1.

Percentage of eliminated cysts and Mean ± SD of Acanthamoeba spp. with various concentration of miltefosine and chlorhexidine (positive control)

| Acanthamoeba genotype | Exposure time (d) | Mean ± SD and percentage of eliminated cyst of Acanthamoeba spp. | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Miltefosine with various concentration (mM) | PBS (Non-treated control) | Chlorhexidine (mM) (Positive control) | |||||||

| 2.42 | 4.84 | 9.68 | 19.36 | 38.72 | 77.44 | 0.04 | |||

| Mean ± SD (%) | Mean ± SD (%) | Mean ± SD (%) | Mean ± SD (%) | Mean ± SD (%) | Mean ± SD (%) | Mean ± SD (%) | Mean ± SD (%) | ||

| T3 | 1 | 19.1 ± 0.04*** (4.5) | 16.1 ± 0.01* (19.5) | 11.0 ± 0.05* (45) | 7.3 ± 0.01** (63.5) | 2.8 ± 0.01 (86) | 0.00** (100) | 19.9 ± 0.01 (0.5) | 0.00** (100) |

| 3 | 18.3 ± 0.02*** (8.5) | 14.6 ± 0.03* (27) | 7.1 ± 0.01** (64.5) | 4.0 ± 0.02** (80) | 0.00** (100) | 0.00** (100) | 19.7 ± 0.04 (1.5) | 0.00** (100) | |

| 5 | 16.0 ± 0.02* (20) | 12.3 ± 0.02* (38.5) | 4.3 ± 0.04** (78.5) | 0.00** (100) | 0.00** (100) | 0.00** (100) | 19.6 ± 0.04 (2) | 0.00** (100) | |

| 7 | 14 ± 0.03* (30) | 9.3 ± 0.015**(53.5) | 0.00** (100) | 0.00** (100) | 0.00** (100) | 0.00** (100) | 19.4 ± 0.05 (3) | 0.00** (100) | |

| T4 | 1 | 18.2 ± 0.01*** (9) | 6.4 ± 0.02** (68) | 5.6 ± 0.03** (72) | 16.4 ± 0.01** (82) | 0.00** (100) | 0.00** (100) | 19.8 ± 0.04 (1) | 0.00** (100) |

| 3 | 17.4 ± 0.05* (13) | 4.8 ± 0.01** (76) | 3.0 ± 0.02** (85) | 0.00** (100) | 0.00** (100) | 0.00** (100) | 19.6 ± 0.02 (2) | 0.00** (100) | |

| 5 | 16.7 ± 0.03* (16.5) | 3.6 ± 0.0**1 (82) | 0.00** (100) | 0.00** (100) | 0.00** (100) | 0.00** (100) | 19.3 ± 0.04 (3.5) | 0.00** (100) | |

| 7 | 11 ± 0.01* (45) | 0.00** (100) | 0.00** (100) | 0.00** (100) | 0.00** (100) | 0.00** (100) | 19.2 ± 0.02 (4) | 0.00** (100) | |

| T5 | 1 | 18.1 ± 0.01*** (9.5) | 7.0 ± 0.02** (65) | 6.4 ± 0.01** (68) | 5.0 ± 0.03** (75) | 0.00** (100) | 0.00** (100) | 19.9 ± 0.01 (0.5) | 0.00** (100) |

| 3 | 17.8 ± 0.01* (16) | 5.8 ± 0.04** (71) | 4.2 ± 0.03** (79) | 0.00** (100) | 0.00** (100) | 0.00** (100) | 19.8 ± 0.03 (1) | 0.00** (100) | |

| 5 | 16.8 ± 0.01* (11) | 3.4 ± 0.01** (83) | 0.00** (100) | 0.00** (100) | 0.00** (100) | 0.00** (100) | 19.6 ± 0.02 (2) | 0.00** (100) | |

| 7 | 11.6 ± 0.01* (42) | 0.00** (100) | 0.00** (100) | 0.00** (100) | 0.00** (100) | 0.00** (100) | 19.4 ± 0.01 (3) | 0.00** (100) | |

After incubation with miltefosine and chlorhexidine, mean numbers of survival cysts were compared to non-treated control by using ANOVA

SD standard deviation

**P < 0.001 statistically highly significant difference, *P < 0.05 statistically significant difference, ***P > 0.05 no statistically significant difference

Fig. 2.

Effect of miltefosine against Acanthamoeba cysts of three genotypes after exposure for 1 day, then observed by light microscopy (× 40). a–c Untreated cyst; d T3 treated with concentration of 38.72 mM; e T4 treated with concentration of 38.72 mM and f T5 treated with concentration of 77.44 mM

At present, miltefosine (antineoplastic agent) is used for a treatment of visceral and cutaneous leishmaniasis with various sensitivity depending on the type of species (Esmaeili et al. 2008).For Acanthamoeba inhibition, previous study demonstrated the in vitro study for trophozoicidal activity of miltefosine against difference strains of Acanthamoeba spp. with various concentration and they reported the minimal trophozoicidal concentration (MTC) of miltefosine against A. castellanii was 62.5 µM, and for Acanthamoeba sp. and A. lugdunensis were 250 µM and 500 µM, respectively (Mrva et al. 2011). For cysticidal activity, previous study demonstrated the eradication of the cyst was not completely obtained using miltelfosine, alkylphosphocholine, at the concentration 80 µM after 3 d of incubation, the results just showed killing effect varied from 60 to 80% depend on Acanthamoeba strains (Walochnik et al. 2002). The present study demonstrated MCC of miltefosine for killing of cyst form of Acanthamoeba spp. which are belonging to genotype T3, T4 and T5. The result showed that there was no difference for the concentration 38.72 mM, 19.36 mM, 9.68 mM and 4.84 mM of miltefosine against T4 and T5 after 1, 3, 5 and 7 d, respectively. However, killing of genotype T3 needed higher concentration, 77.44 mM, 38.72 mM, 19.36 mM, 9.68 mM, at the same incubation time. It is obvious that cysticidal concentration is higher than trophozoicidal concentration in the same incubation time. Therefore, successful of killing cyst can be possible by both appropriate concentration and incubation time. The possible reason of previous study failed to kill 100% of cyst form might be using the concentration and time of incubation similar to trophozoicidal assessment (Walochnik et al. 2002). Several studies have reported the chemical composition of Acanthamoeba cysts, and it is reported that the endocyst and ectocyst consists of polysaccharides, mainly cellulose (Weisman 1976). The difference in the resistance of genotype T3, T4 and T5 have been reported (Shoff et al. 2007; Coulon et al.2010). For instance, previous study has reported T3 genotypes is more resistant to multipurpose contact lens cleaning solutions than T4 genotype (Shoff et al. 2007). Therefore, the differences in the resistance of each genotype may partly be due to the thickness of the ectocyst and the amount of cellulose content (Coulon et al.2010). Miltefosine is able to cross the blood–brain barrier (Schuster et al. 2006). Therefore, it has been applied to treat any pathogen causing CNS infection including free-living Acanthamoebae. This study reported the MCC of miltefosine for 100% eradication of Acanthamoeba cysts. Although there might be difference in concentration for treatment of different strains and needs to be confirmed by animal models, this information can be used for clinical practice or combined with the other drug for successful treatment.

Acknowledgements

This study was supported in part by Grants from the following: the Thailand Research Fund (MRG6080065); and was supported in part by the Faculty of Medicine of Khon Kaen University.

Compliance with ethical standards

Conflict of interest

The authors declare that there is no conflict of interest.

Footnotes

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

References

- Alsam S, Sik K, Stins M, Ortega A, Sissons J, Ahmed N. Acanthamoeba interactions with human brain microvascular endothelial cells. Microb Pathog. 2003;35(6):235–241. doi: 10.1016/j.micpath.2003.07.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Carrijo-Carvalho LC, Sant’ana VP, Foronda AS, de Freitas D, de Souza Carvalho FR. Therapeutic agents and biocides for ocular infections by free-living amoebae of Acanthamoeba genus. Surv Ophthalmol. 2017;62(2):203–218. doi: 10.1016/j.survophthal.2016.10.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Coulon C, Collignon A, McDonnell G, Thomas V. Resistance of Acanthamoeba cysts to disinfection treatments used in health care setting. J Clin Microbiol. 2010;48(8):2689–2697. doi: 10.1128/JCM.00309-10. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Esmaeili J, Mohebali M, Edrissian GH, Rezayat SM, Ghazikhansari M, Charehdar S. Evaluation of miltefosine against Leishmania major (MRHO/IR/75/ER): in vitro and in vivo studies. Acta Med Iran. 2008;46(3):191–196. [Google Scholar]

- Fuerst PA, Boonton GC, Crary M. Phylogenetic analysis and the evolution of the 18S rRNA gene typing system of Acanthamoeba. J Eukaryot Microbiol. 2015;62(1):69–84. doi: 10.1111/jeu.12186. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ledee DR, Iovieno A, Miller D, Mandal N, Diaz M, Fell J, Fini ME, Alfonso EC. Molecular identification of T4 and T5 genotypes in isolates from Acanthamoeba keratitis patients. J Clin Microbiol. 2009;47(5):1458–1462. doi: 10.1128/JCM.02365-08. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Maghsood AH, Sissons J, Rezaian M, Nolder D, Warhurst D, Khan NA. Acanthamoeba genotype T4 from the UK and Iran and isolation of the T2 genotype from clinical isolates. J Med Microbiol. 2005;54(Pt8):755–759. doi: 10.1099/jmm.0.45970-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Marciano-Cabral F, Puffenbarger R, Cabral GA. The increasing importance of Acanthamoeba infection. J Eukaryot Microbiol. 2000;47(1):29–36. doi: 10.1111/j.1550-7408.2000.tb00007.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mrva M, Garajová M, Lukáč M, Ondriska F. Weak cytotoxic activity of miltefosine against clinical isolates of Acanthamoeba spp. J Parasitol. 2011;97(3):538–540. doi: 10.1645/GE-2669.1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pussard M, Pons R. Morphologies de la paroi kystique et taxonomie du genre Acanthamoeba (Protozoa, Amoebida) Protistologica. 1977;13(4):557–598. [Google Scholar]

- Sawyer TK, Griffin JL. A proposed new family, Acanthamoebidae n. fam. (order Amoebida), for certain cyst-forming filose amoebae. Trans Am Microsc Soc. 1975;94(1):93–98. doi: 10.2307/3225534. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Schuster FL, Guglielmo BJ, Visvesvara GS. In vitro activity of miltefosine and voriconazole on clinical isolates of freeliving amebas: Balamuthia mandrillaris, Acanthamoeba spp., and Naegleria fowleri. J Eukaryot Microbiol. 2006;53(2):121–126. doi: 10.1111/j.1550-7408.2005.00082.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shoff M, Rogerson A, Schatz S, Seal D. Variable responses of Acanthamoeba strains to three multipurpose lens cleaning solutions. Optom Vis Sci. 2007;84(3):202–207. doi: 10.1097/OPX.0b013e3180339f81. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Siddiqui R, Khan NA. Biology and pathogenesis of Acanthamoeba. Parasites Vectors. 2012;5:1–13. doi: 10.1186/1756-3305-5-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Thammaratana T, Laummaunwai P, Boonmars T. Isolation and identification of Acanthamoeba species from natural water sources in the northeastern part of Thailand. Parasitol Res. 2016;115(4):1705–1709. doi: 10.1007/s00436-016-4911-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Walochnik J, Duchêne M, Seifert K, Obwaller A, Hottkowitz T, Wiedermann G, Eibl H, Aspöck H. Cytotoxic activities of alkylphosphocholines against clinical isolates of Acanthamoeba spp. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 2002;46(3):695–701. doi: 10.1128/AAC.46.3.695-701.2002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Weisman RA. Differentiation in Acanthamoeba castellanii. Annu Rev Microbiol. 1976;30:189–219. doi: 10.1146/annurev.mi.30.100176.001201. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]