Abstract

The aim of this study was to evaluate and compare the efficiency of bovine (CW) and buffalo cheese whey (BCW) as encapsulating agents for the spray-drying (SD) of endogenous Lactobacillus pentosus ML 82 and the reference strain Lactobacillus plantarum ATCC 8014. Their protective features were also tested for resistance to storage (90 days, 25 °C), simulated gastrointestinal tract (GIT) conditions, and for their application in orange juice. Survival rates after SD were approximately 95% in all samples tested, meaning both CW and BCW performed satisfactorily. After 90 days of storage, both species remained above 7 log Colony Forming Units (CFU)/g. However, CW generally enabled higher bacterial viability throughout this period. CW microcapsule characteristics were also more stable, which is indicated by the fact that BCW had higher moist content. Under GIT conditions, encapsulated lactobacilli had higher survival rates than free cells regardless of encapsulating agent. Even so, results indicate that CW and BCW perform better under gastric conditions than intestinal conditions. Regarding their use in orange juice, coating materials were probably dissolved due to low pH, and both free and encapsulated bacteria had similar survival rates. Overall, CW and BCW are suitable encapsulating agents for lactic acid bacteria, as they provided protection during storage and against harmful GIT conditions.

Keywords: Probiotics, Spray-drying, Gastrointestinal tract, Functional foods

Introduction

Lactic acid bacteria (LAB) are food-grade microorganisms, which are responsible for causing changes in dairy, meat, and plant products, enhancing sensory properties such as flavor and texture, and increasing shelf life (Asteri et al. 2010). Commercial LAB cultures are widely used in food processing, which inevitably lead to final products that have similar sensory characteristics and technological properties. Autochthonous or endogenous microorganisms, on the other hand, may provide specific aromas and flavors, and are often restricted to a certain region of the globe [e.g., Protected Denomination of Origin (PDO)]. As reported by Mangia et al. (2013), these microorganisms are naturally found in raw materials, equipment, or in the manufacturing environment, and are considered a market differentiation.

In addition, LAB naturally inhabit the human gut (Motta and Gomes 2015) and are commonly associated with the treatment of diseases related to the gastrointestinal tract (GIT) (Wang et al. 2015; Caggia et al. 2015; Greifová et al. 2017). Certain LAB strains are classified as probiotic, which are microorganisms that maintain intestinal flora equilibrium and composition, and thus enhance resistance to pathogens. In other words, probiotics tend to provide health benefits to people who consume them (FAO/WHO 2002). The major obstacles affecting the survival of probiotic microorganisms, which consequently restrict their applicability in food matrices, are low pH and presence of bile salts in the human GIT. Hence, surviving under these conditions is important for these microorganisms to confer health benefits to the host (Del Piano et al. 2011; Tripathi and Giri 2014).

Therefore, the encapsulation of probiotics may provide protection that increases their viability not only under GIT conditions but also during processing and storage. Encapsulation is a process, either physical–chemical or mechanical, that entraps a substance (nucleus) inside another material (encapsulating agent) in order to obtain particles with a diameter that can range from nanometers to a few millimeters (Đorđević et al. 2014). Spray-drying (SD) is an encapsulation technique that has been widely applied for LAB using many edible sources as encapsulating agents due to its high cost–benefit rate (Ghandi et al. 2012; Pérez-Chabela et al. 2013; Liao et al. 2017). Actually, the majority of published reports regarding the SD of LAB involves probiotic microorganisms, e.g., Ranadheera et al. (2015), Huang et al. (2017), Eckert et al. (2017), Nunes et al. (2018), and Rama et al. (2019a).

The major probiotic LAB genera are Lactobacillus and Bifidobacterium (Brinques et al. 2010; Rokka and Rantamäki 2010). Lactobacilli are considered one of the most versatile LAB genus because of their broad applications as starter, non-starter, or probiotic cultures in the food industry (Angmo et al. 2016; Marco et al. 2017; Li and Han 2018). Moreover, their high tolerance to adverse conditions has caused lactobacilli to dominate the flora of several traditional fermented dairy products (Rushdy and Gomaa 2013; Ferrando et al. 2016; Farimani et al. 2016; Picon et al. 2016; Domingos-Lopes et al. 2017). Lactobacillus pentosus, which is the focus of this study, has been reported as fermentation agent of table olives (Tofalo et al. 2014) and Portuguese PDO cheeses (Guerreiro et al. 2014), as well as starter for mushroom preparations (Liu et al. 2016). Its probiotic features have also been described (Jeong et al. 2015; Pérez Montoro et al. 2018), further supporting the versatility of this species.

Probiotic lactobacilli are the object of most reports on SD of LAB. There are many other studies aside from those mentioned above (Rajam et al. 2012; Khem et al. 2016a; Huang et al. 2016; Guergoletto et al. 2017). On the other hand, dairy by-products such as bovine cheese whey (CW) have been successfully employed as encapsulating agents of probiotic lactobacilli, providing satisfactory viability maintenance during SD, storage, and after going through simulated GIT conditions (Lavari et al. 2015; Hugo et al. 2016). Authors claim that this performance is due to the interactions between proteins and lactose, which are primary CW components (Maciel et al. 2014; Khem et al. 2016a). The amount of CW produced annually is approximately 180–190 million tons, of which only 50% is processed (Mollea et al. 2013). This production is estimated to reach 230 million tons (Rama et al. 2019b) by 2023. Since this by-product has a high organic load and is 150 times more pollutant than domestic waste (Gallego-Schmid and Tarpani 2019), it represents an environmental threat if discarded inappropriately (Sansonetti et al. 2009).

For that reason, strategies for the reuse of CW are highly required, and there has been increased interest in non-bovine sources of CW such as buffalo cheese whey (BCW), as this material has a higher concentration of proteins and lactose (Lira et al. 2009; Román et al. 2011), as well as higher content of β-lactoglobuline and α-lactoalbumine compared to CW (Buffoni et al. 2011). Due to this composition, BCW may also be employed for the encapsulation of probiotic LAB. This is the main novelty of the present study as this material has not been evaluated for this purpose, yet. Moreover, the use of both CW and BCW means that valuable by-products are reused, avoiding their disposal as waste and preventing the consequent cost with wastewater treatment. It also leads to added value and biotechnological development in food processing.

Therefore, the aim of this study was to evaluate and compare the efficiency of CW and BCW as encapsulating agents for the SD of two different lactobacilli: an endogenous L. pentosus ML 82, and a reference strain, Lactobacillus plantarum ATCC 8014. This study also aimed to evaluate the survival of encapsulated bacteria throughout the SD process itself and during 90 days storage at 25 °C. During this period, viability was also tested in terms of resistance after going through simulated GIT and after adding encapsulated bacteria to orange juice.

Materials and methods

Microorganisms and media

Lactobacillus pentosus ML 82 strain is endogenous to Taquari Valley (Rio Grande do Sul, Brazil) (Agostini et al. 2018) and L. plantarum ATCC 8014 is a reference strain, used here as positive control. CW and BCW were kindly provided in their liquid form by dairy industries of the Taquari Valley region. These materials were transported under refrigeration and maintained at − 20 °C until further use. Before being used, both were pasteurized in water bath (Marconi® MA127, Brazil) at 67 °C for 60 min. All the reagents evaluated in this study were of analytical grade, and synthetic culture media were purchased from Merck® (Germany).

Composition of bovine and buffalo cheese whey

The CW and BCW used in this study were analyzed regarding total solids (gravimetric method, no. 990.20), fat (Mojonnier method, no. 989.05), protein (Kjeldahl method, no. 991.20), and ash contents (Muffle furnace method, no. 945.46) according to AOAC International (2012). Carbohydrate content was calculated using the difference method, according to Eq. 1, in which TS is total solid content (%), F is fat content (%), P is protein content (%), and A is ash content (%)

| 1 |

Cultivation of L. pentosus ML 82 and L. plantarum ATCC 8014

Both strains underwent the same cultivation process. Initially, an isolated colony was transferred to 50 ml of de Man, Rogosa, and Sharpe (MRS) broth. The culture was incubated at 32 °C for 18 h until it reached an Optical Density at 600 nm (OD600) of 2.0 ± 0.1, which was measured using a spectrometer (Shimadzu® UV-2600, Japan). After this period, 40 mL of culture were transferred to 400 mL of MRS broth and incubated at 32 °C until the culture reached OD600 of 2.0 ± 0.1 (around 12 h) again. All the cultivated volume was then centrifuged at 2790 × g for 10 min at 4 °C and rinsed twice in phosphate buffer (10 mM, pH 7.0). Subsequently, centrifuged LAB were inoculated to 400 ml of either CW or BCW and incubated at 32 °C, until they reached the stationary phase (around 16 h). This procedure followed Eckert et al. (2018). Four different broths resulted from the cultivation step: L. pentosus ML 82 in CW (B1) and in BCW (B2), and L. plantarum ATCC 8014 in CW (B3) and in BCW (B4).

Spray-drying of L. pentosus ML 82 and L. plantarum ATCC 8014

Drying procedures were carried out according to Eckert et al. (2017). Each fermented whey broth (B1, B2, B3, and B4) underwent SD separately using laboratory-scale equipment (Labmaq® MSD 0.5, Brazil) with a 0.8 mm spray nozzle. Air inlet (IT) and outlet (OT) temperatures were 90 °C and 75 °C, respectively, in all procedures. Each feeding solution containing the LAB strain was kept agitated at room temperature (25 °C), and was pumped at a feeding rate of 4.5 ml/min and an airflow of 1.10 m3/min at 0.3 MPa. The resulting powders were stored for 90 days in sterile glass flasks at 25 °C.

Viability of encapsulated bacteria after SD

To determine viability after the SD process, bacteria were counted before and immediately after the culture was submitted to spray-drying. Bacterial counts were determined by serial dilutions in peptone water (0.1% (w/v)), plating in MRS agar, and incubation at 32 °C for 48 h, according to Kim et al. (2008). After the encapsulation process, viable cells were determined after suspending 0.1 g of the dried powder in 10 mL of phosphate buffer (100 mM, pH 7.0). Suspensions were agitated for 15 min at 180 rpm and 20 °C in an orbital agitation incubator (namely shaker, Marconi® MA830, Brazil), in order to dissolve capsules and release viable bacteria. Bacterial counts were again diluted and plated in MRS agar, as described above.

Survival after SD was expressed in log reduction according to Eq. 2, where Nb is the number of viable cells (log Colony Forming Units (CFU)/g dry matter) in the resulting powder, obtained immediately after the encapsulation process, and Na is the number of viable cells (log CFU/g of dry matter) in the feeding solution, before drying

| 2 |

Microcapsule characterization

In order to examine the morphology of microcapsules and estimate their size, powders were fixed with double-sided carbon tape immediately after the drying process, coated with gold on a sputter coater (Quorum® Q150R ES, England), and viewed by scanning electron microscopy (SEM) (Carl Zeiss® LS 10, Germany) in high-vacuum mode (Eckert et al. 2017). After SD, the resulting powders were kept at 25 °C, simulating storage at room temperature (25 °C). Survival of encapsulated bacteria during storage was analyzed in days 0, 7, 15, 30, 45, 60, and 90, as shown in "Viability of encapsulated bacteria after SD", and results are expressed in log CFU/g. Moisture content was evaluated according to AOAC method no. 990.20 (AOAC International 2012), using an oven dryer (Marconi® MA033/5, Brazil) at 105 °C. Water activity (aw) was measured using an AquaLab water activity meter (AquaLab® Lite, United States of America). Color analyses were performed using a colorimeter (Konica Minolta® CM-5, Japan) and a color scale to measure parameters ‘L*’, ‘a*’, and ‘b*’. Samplings were performed for moisture content, water activity, and color analyses at days 0, 45, and 90 of storage.

Survival after simulated gastrointestinal tract

Simulated gastric juice was prepared using pepsin (3 g/l) and NaCl (5 g/l) at pH 2.0, 2.5, or 3.0. Intestinal juice was prepared with pancreatin (1 g/l) and NaCl (5 g/l) at pH 8.0, with or without bile salts (5 g/l of a mixture of sodium cholate and sodium deoxycholate, in a 1:1 ratio). The five solutions were previously sterilized using a filter membrane with 0.22 μm pore diameter (Sartorius Stedim Biotech®, Germany). In order to evaluate encapsulated bacterial survival, 0.1 g of each dried powder was exposed to 1 mL of the previously described solutions. The mixtures were then stirred in an orbital shaker (Marconi® MA830, Brazil) for 15 min at 180 rpm and 20 °C until the capsules were completely released. In the control, 200 μl of non-encapsulated cultures (prepared as described in "Cultivation of L. pentosus ML 82 and L. plantarum ATCC 8014") were also submitted to 1 ml of each simulated GIT solution. Bacterial counts were analyzed after 3 h of exposure to gastric tract and after 4 h of exposure to intestinal tract at 37 °C. For that, serial dilutions in peptone water (0.1% (w/v)) were plated in MRS agar and incubated for 48 h at 32 °C. The survival of microorganisms exposed to each condition was expressed in log CFU/ml. This procedure for measuring survival after simulated GIT was performed according to Eckert et al. (2017). The entire simulated GIT procedure was repeated at 0, 30, 60, and 90 days of storage at 25 °C.

Survival in orange juice

Free and encapsulated bacteria were incorporated into sterilized commercial orange juice (100% natural orange juice) separately, adding either 1 ml of free cells (prepared as shown in "Cultivation of L. pentosus ML 82 and L. plantarum ATCC 8014") or 1 g of dried powder to every 100 mL of orange juice. Samples were homogenized and stored at 4 °C for 90 days. During storage, pH values of the juice were analyzed using a pHmeter (Digimed® DM-22, Brazil). Cell viability was evaluated on days 0, 30, 60, and 90, as described in "Viability of encapsulated bacteria after SD", and is expressed in log CFU/ml.

Statistical analysis

Statistical analyses were performed using Student’s t test (for two samples, e.g. when comparing encapsulating agents) or Analysis of Variance (ANOVA) followed by Tukey’s test (for three or more samples, e.g. when comparing storage days), with significance of 95% (p ≤ 0.05). Analyses were performed using BioEstat 5.3. Graphs were generated using OriginLab 8.0.

Results and discussion

Composition of CW and BCW

Table 1 describes the composition of CW and BCW used in this study, regarding fat, protein, carbohydrate, ash, and moisture contents. Results corroborate the findings reported by Buffoni et al. (2011). In fact, BCW contains approximately twice the amount of proteins than CW, as well as higher lactose contents (Lira et al. 2009; Román et al. 2011). Moreover, Sales et al. (2017) found higher protein values (0.94%) in BCW than those obtained in the present study. Differences in whey composition are caused by several factors such as animal breed, feeding system, and the type of cheese from which whey is derived (Liao et al. 2017). Industrial yields, however, are enhanced by increased concentration of solids in the medium (Buzi et al. 2009).

Table 1.

Physical and chemical composition (%) of bovine cheese whey (CW) and buffalo cheese whey (BCW)

| Media | Composition (%) | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Fat | Protein | Carbohydrate | Ash | Moisture | |

| CW | 0.20 ± 0.01a | 0.34 ± 0.01b | 5.28 ± 0.02b | 0.60 ± 0.03a | 93.58 ± 0.01a |

| BCW | 0.20 ± 0.01a | 0.52 ± 0.02a | 6.19 ± 0.08a | 0.47 ± 0.01b | 92.62 ± 0.06b |

Results are expressed in mean ± standard deviation (n = 3). Different superscript letters in the same column indicate statistical difference (p ≤ 0.05) according to Student's t test

This is especially important regarding SD, since process efficiency as well as survival rate of the exposed microorganisms are positively correlated to the amount of solids remaining in the solution that is fed into the dryer, at least to a certain value, which lies between 20 and 30% according to Huang et al. (2017). These authors found that survival rates of L. casei gradually increased when total solids of drying solutions increased from 5 to 30%. However, the effect seemed to be the opposite at a concentration of 40%: survival decreased, which may be related to the high osmotic pressure of this solution (Huang et al. 2017). The solid content of the materials tested in our study (CW and BCW) are approximately 7%.

Spray-drying of L. pentosus ML 82 and L. plantarum ATCC 8014

Viability of encapsulated bacteria after SD

Table 2 shows the log reduction of encapsulated microorganisms using both materials (CW and BCW). In general, both encapsulating agents were suitable for SD of L. pentosus ML 82 and L. plantarum ATCC 8014. Bacterial survival rates (%) were 94.00 ± 2.37 (L. pentosus, CW), 96.12 ± 1.23 (L. pentosus, BCW), 95.51 ± 1.36 (L. plantarum, CW), and 98.7 ± 1.34 (L. plantarum, BCW). There is no statistical difference (p ≤ 0.05) between these values; thus, it is clear that CW and BCW provided similar protection throughout the process. These results are in agreement with the findings by other authors, which also employed SD of probiotic LAB using CW as encapsulating agent and obtained survival rates higher than 95% (De Castro-Cislaghi et al. 2012; Pinto et al. 2015b; Eckert et al. 2017).

Table 2.

Log reduction of L. pentosus ML 82 and L. plantarum ATCC 8014 after SD, encapsulated in bovine cheese whey (CW) and buffalo cheese whey (BCW)

| Microorganism | Reduction (log CFU/g) | |

|---|---|---|

| CW | BCW | |

| L. pentosus ML 82 | 0.66 ± 0.26a | 0.41 ± 0.13ab |

| L. plantarum ATCC 8014 | 0.48 ± 0.15ab | 0.14 ± 0.15b |

Results are expressed in mean ± standard deviation (n = 3). Different superscript letters indicate statistical difference (p ≤ 0.05) according to Tukey’s test

Furthermore, aside from temperature, one of the most critical factors that affect the survival of microorganisms in SD is the encapsulating agent itself. The selection of suitable materials is very important because it ensures the survival of microorganisms undergoing SD, and because it affects microcapsule efficiency and stability. According to Silva et al. (2014), the ideal encapsulating agent must: (a) not react with the nucleus; (b) maintain the nucleus material inside the capsule; (c) be able to protect the nucleus against environmental conditions, such as oxygen, light, humidity, temperature changes, acidity, and others; (d) not affect the taste of the final product (in case of food applications); and (e) be economically viable. Materials used for the encapsulation of LAB include polysaccharides derived from algae (Carrageenan, alginate), plants (starch and its derivatives, gum Arabic), and fruit (pectin), as well as products resulting from bacterial metabolism (gums such as gellan and xanthan) (Martín et al. 2015). Other polysaccharides such as pullulan and inulin have raised interest due to their prebiotic features, and they may increase the viability of probiotics if added to wall materials (Pinto et al. 2015a; Chlebowska-Smigiel et al. 2017; de Andrade et al. 2019; Chlebowska-Śmigiel et al. 2019). Finally, animal proteins (milk proteins, gelatin, collagen) are also a frequent choice for the encapsulation of bacteria (Martín et al. 2015).

Đorđević et al. (2014) stated that the presence of carbohydrates and proteins is essential for the formation of good capsules, and consequently, for effective bacterial protection. This happens because lactose, for instance, interacts with the phospholipids present in bacterial cell membranes, thereby minimizing damages caused by SD (Maciel et al. 2014). Proteins, on the other hand, suffer denaturation when exposed to the high temperatures employed in this process. Under these conditions, carboxylic and amino groups are available for reactions, increasing hydrophobic forces and hydrogen-sulfide bonds, which lead to an array of changes in protein structure. These changes are responsible for protecting LAB from harsh conditions of drying and storage and they also increase their survival going through the GIT (Khem et al. 2016a). Therefore, a good microorganism survival was expected since CW and BCW contain these nutrients. Nonetheless, it is worth noting that the similar results (p ≤ 0.05) of both dairy by-products tested in this study indicate that their different compositions, especially in terms of protein and carbohydrate content, did not affect their efficiency in protecting the two Lactobacilli, as they both performed satisfactorily.

Microcapsule characterization

Figure 1 shows decreased viability of L. pentosus ML 82 and L. plantarum ATCC 8014 encapsulated in CW and BCW during storage at 25 °C. Under this condition, CW enabled the lowest reductions after 90 days: 2.2 ± 0.27 and 1.77 ± 0.27 log CFU/g for L. pentosus and L. plantarum, respectively. There was no statistical difference (p ≤ 0.05) between these values, which means that both microorganisms lost a similar amount of viable cells during storage when encapsulated in CW. This result is particularly important because endogenous LAB represent a market differentiation, as they are able to provide specific characteristics to food products, reinforcing typicality and regional aspects (Mangia et al. 2013). Thus, the interest in producing such cultures may increase, considering that regional dairy products are a market trend for the next years (ITAL 2017). In addition, BCW-encapsulated L. pentosus had the highest loss of viability in the four samples (3.78 ± 0.16 log CFU/g), which is probably due to the high moisture content observed at the end of storage (15.42 ± 0.07%). Increased moisture leads to wall material degradation and subsequent exposure of living cells to the environment, thus reducing their survival rates (Moncmanová 2007). Reduction of BCW-encapsulated L. plantarum was 2.44 ± 0.24 log CFU/g, which indicates that L. plantarum had better survival (p ≤ 0.05) than L. pentosus when encapsulated in this material. In general, CW had better microorganism viability results during 90 days of storage at 25 °C.

Fig. 1.

Cell viability (log CFU/g) of spray-dried bacteria during 90 days of storage at 25 °C. L. pentosus ML 82 encapsulated in bovine cheese whey (filled square); L. pentosus ML 82 encapsulated in buffalo cheese whey (unfilled circles); L. plantarum ATCC 8014 encapsulated in bovine cheese whey (filled triangles); L. plantarum ATCC 8014 encapsulated in buffalo cheese whey (unfilled inverted triangles)

Khem et al. (2016b) claim that the survival of SD microorganisms may be related to interactions between cell membrane and the protein matrices of capsules, which occur due to hydrophobic forces. Denatured proteins have a higher potential to interact with membranes because of changes in their globular structure, which expose reactive groups and offer better protection to bacterial cells. Due to high temperature, both CW and BCW suffered protein denaturation during SD. BCW was expected to offer better protection during storage due to the higher protein content in this material; however, increased moisture in BCW-encapsulated capsules may have degraded the protein matrix so much so that the interaction with membrane cells decreased. Therefore, cells were more exposed to environmental conditions (oxygen, and temperature changes), and consequently, had higher viability losses.

Still regarding storage, Huang et al. (2017) studied CW-encapsulated Lactobacillus casei BL23 with capsules stored at 4 °C and 25 °C for 6 months. Lower temperature allowed constant viability during the first two months, while a 2-log CFU/g decrease was observed at 25 °C. After 180 days, L. casei reduced by 1 and 4 log CFU/g viable cells when stored at 4 and 25 °C, respectively. These results are better than those obtained in the present study with both microorganisms and encapsulating agents employed for protection, possibly due to the fact that Huang et al. (2017) stored the powders in vacuum bags, which provided better stability to the material. Nonetheless, storage at higher temperatures causes a higher loss in viability, which also corroborates what has been reported by Golowczyc et al. (2011). On the other hand, more than 6 log CFU/g of each LAB were present in the powders analyzed after 90 days, which is the minimum amount of probiotics required for functional foods (FAO/WHO 2002). Considering that keeping the product at room temperature is more economically advantageous, and that it still allowed the maintenance of cell counts, it is acceptable to assume that the long-term storage of CW- and BCW-encapsulated probiotic bacteria using SD is approximately 6 months at room temperature. However, testing this at abusive temperatures is strongly recommended, since mean room temperature may not always be 25 °C.

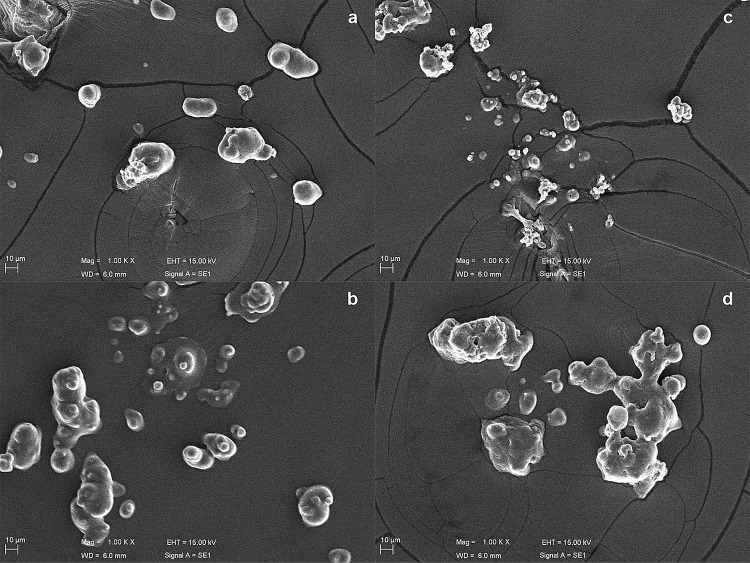

Regarding microcapsule morphology, Fig. 2 shows Scanning Electron Microscopy (SEM) images of both bacteria evaluated in this study, encapsulated in both CW and BCW. All capsules exhibited similar (p ≤ 0.05) morphology, with sizes between 7.77 and 16.87 μm regardless of material, which is in accordance with the sizes expected for SD materials (Behboudi-Jobbehdar et al. 2013; Đorđević et al. 2014). Small-sized capsules are suitable to food processing, because they do not affect product texture and sensory properties; therefore, sizes smaller than 40 μm are required (Duongthingoc et al. 2013). Moreover, it was not possible to visualize bacterial cells outside or on microcapsule surfaces, which confirms encapsulation. Particles also exhibited concavities, which is a characteristic of this type of dried product (Favaro-Trindade et al. 2010). These concavities are temperature-dependent, caused by moderate temperatures, and provide mechanical resistance and solute diffusion (Rodríguez-Huezo et al. 2007). Similar results have been found by other researchers 10.55-μm (Pinto et al. 2015b) and 11.23-μm (De Castro-Cislaghi et al. 2012) using CW as wall material.

Fig. 2.

Scanning electron micrograph (SEM) images of bacteria encapsulated by spray-drying: aL. pentosus ML 82, encapsulated in bovine cheese whey; bL. pentosus ML 82, encapsulated in buffalo cheese whey; cL. plantarum ATCC 8014, encapsulated in bovine cheese whey; dL. plantarum ATCC 8014, encapsulated in buffalo cheese whey. All images have a 1000× magnification and a 10-μm scale

Table 3 shows the development of characteristics (moisture, water activity, and color) of L. pentosus ML 82 powder encapsulated in both materials (CW and BCW), while Table 4 shows the same parameters for L. plantarum ATCC 8014. During storage, there was a gradual and significant (p ≤ 0.05) moisture increase in both microorganisms encapsulated in BCW. The aw of BCW-encapsulated L. pentosus capsules also increased, while this parameter remained the same in BCW-L. plantarum. Lower variations in moisture of CW microcapsules were observed in both microorganisms compared to BCW. Additionally, aw of L. plantarum microcapsules remained stable throughout the storage period, regardless of encapsulating agent. Except for BCW-encapsulated L. pentosus, most results of moisture and water activity obtained in this study lie within the suitable range: Rodríguez-Huezo et al. (2007) claim that moisture is supposed to remain between 4 and 7% for milk-based SD products. On the other hand, aw values of nearly all samples did not fit the recommended range, which is below 0.3 (Tonon et al. 2009; De Castro-Cislaghi et al. 2012). Increased aw may have contributed with binding of particles, observed in Fig. 2, which derives from a heat-induced phenomenon called caking, driven by hygroscopic amorphous lactose, which absorbs water and is converted into α-lactose monohydrate crystals (Fox et al. 2015).

Table 3.

Evolution of the characteristics of CW and BCW L. pentosus ML 82 microcapsules throughout 90 days of storage

| Days | Moisture (%) | aw | Color | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| CW | BCW | CW | BCW | CW | BCW | |

| 0 | 5.50 ± 0.01a,A | 5.26 ± 0.07b,C | 0.380 ± 0.020a,A | 0.361 ± 0.011a,B | L* = 95.17 ± 0.97a,A | L* = 93.73 ± 0.48a,A |

| a* = − 1.31 ± 0.03b,A | a* = − 1.74 ± 0.09a,B | |||||

| b* = 7.97 ± 0.05b,A | b* = 8.52 ± 0.19a,C | |||||

| 45 | 2.63 ± 0.13b,C | 7.69 ± 0.20a,B | 0.389 ± 0.010a,A | 0.344 ± 0.015b,B | L* = 87.72 ± 1.17b,B | L* = 93.03 ± 0.86a,A |

| a* = − 1.10 ± 0.06b,A | a* = − 1.72 ± 0.09a,B | |||||

| b* = 7.06 ± 0.10b,B | b* = 10.92 ± 0.06a,B | |||||

| 90 | 4.60 ± 0.16b,B | 15.42 ± 0.07a,A | 0.393 ± 0.010b,A | 0.549 ± 0.001a,A | L* = 87.60 ± 1.09a,B | L* = 86.02 ± 1.41a,B |

| a* = − 0.87 ± 0.09a,B | a* = − 0.53 ± 0.32a,A | |||||

| b* = 6.14 ± 0.10b,C | b* = 21.37 ± 0.33a,A | |||||

Results are expressed in mean ± standard deviation (n = 3). Different lowercase superscript letters in the same row indicate statistical difference between the encapsulating agents (p ≤ 0.05) according to Student’s t test. Different capital superscript letters in the same column indicate statistical difference between days of storage (p ≤ 0.05) according to Tukey’s test

Table 4.

Evolution of the characteristics of CW and BCW L. plantarum ATCC 8014 microcapsules throughout 90 days storage

| Days | Moisture (%) | aw | Color | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| CW | BCW | CW | BCW | CW | BCW | |

| 0 | 4.03 ± 0.02a,C | 3.32 ± 0.06b,C | 0.299 ± 0.002a,A | 0.316 ± 0.010a,A | L* = 94.32 ± 1.66a,A | L* = 96.65 ± 0.13a,A |

| a* = − 1.20 ± 0.04b,A | a* = − 1.67 ± 0.07a,A | |||||

| b* = 8.61 ± 0.35a,A | b* = 7.58 ± 0.30a,A | |||||

| 45 | 6.44 ± 0.24a,A | 5.53 ± 0.24b,B | 0.359 ± 0.027a,A | 0.302 ± 0.026a,A | L* = 93.94 ± 0.70a,A | L* = 96.50 ± 0.19a,A |

| a* = − 1.09 ± 0.02b,A | a* = − 1.59 ± 0.03a,A | |||||

| b* = 6.52 ± 0.06b,B | b* = 7.90 ± 0.10a,AB | |||||

| 90 | 5.32 ± 0.20b,B | 7.10 ± 0.13a,A | 0.370 ± 0.047a,A | 0.351 ± 0.027a,A | L* = 89.57 ± 1.43a,A | L* = 95.47 ± 0.15b,B |

| a* = − 0.86 ± 0.05b,B | a* = − 1.39 ± 0.12a,A | |||||

| b* = 6.12 ± 0.39b,B | b* = 8.39 ± 0.05a,B | |||||

Results are expressed in mean ± standard deviation (n = 3). Different lower case superscript letters in the same row indicate statistical difference between the encapsulating agents (p ≤ 0.05) according to Student’s t test. Different capital superscript letters in the same column indicate statistical difference between days of storage (p ≤ 0.05) according to Tukey’s test

Microcapsule characteristics directly affect the color of powders, which is considered one of the key parameters for quality of the final product (Sasikumar et al. 2020). Overall, changes in color of spray-dried powders are caused by several biochemical reactions, such as lactose crystallization and migration of free fat to microcapsule surface (Chudy et al. 2015; Ho et al. 2019). In the present study, all microcapsules had high L* values, indicating a tendency towards light (white) coloration, whereas a* values were all negative and b* values were all positive, indicating a tendency towards yellow and green colorations, which agrees with other authors, according to whom whey is a greenish-yellow by-product (Carvalho et al. 2013). The color of L. pentosus ML 82 microcapsules had slight variations throughout storage, except for a sharp increase in b* values of BCW powder, probably due to the absorption of moisture by this material. Combined with the significant (p ≤ 0.05) increase in a* values, this may indicate the occurrence of non-enzymatic browning, also known as Maillard reaction (Palombo et al. 1984; Ho et al. 2019). A few changes in L. plantarum ATCC 8014 microcapsules were also observed over the 90 days. Again, there was a significant (p ≤ 0.05) increase in parameter a*, indicating browning. In general, BCW seems to cause higher variation than CW, which is believed to result from increased moisture observed in this material at the end of storage.

Survival after the simulated gastrointestinal tract

Figure 3 shows the viability of L. pentosus ML 82 and L. plantarum ATCC 8014 encapsulated in CW and BCW while going through the different simulated GIT conditions. This assay was performed at 0, 30, 60, and 90 days of storage at 25 °C. In general, all samples had decreased performance after 30 days, under any GIT conditions; nonetheless, all of them had higher survival rates than free bacteria, with a few exceptions. Under gastric conditions, BCW offered slightly higher protection to L. plantarum than CW, while its protection to L. pentosus was lower. This might be related to strain-dependent resistance (Caggia et al. 2015). However, a sufficient bacterial population (above 7 log CFU/ml) was maintained under all pH conditions at least until 60 days of storage (p ≤ 0.05). After 90 days, both materials lost efficiency, and loss of viability increased; it was higher than 5 log CFU/ml in all samples. De Castro-Cislaghi et al. (2012) evaluated the exposure of CW-encapsulated Bifidobacterium BB-12 to simulated GIT, and observed a 0.73 ± 0.18 log CFU/ml reduction after 180 min of incubation at pH 2.0. Cell counts remained above 7 log CFU/ml for all pH values studied (2, 3, 4 and 6), which is similar to the results obtained in the present study.

Fig. 3.

Cell viability (log CFU/mL) of free and encapsulated bacteria during 90 days of storage ( = free L. pentosus ML 82;

= free L. pentosus ML 82;  = free L. plantarum ATCC 8014;

= free L. plantarum ATCC 8014; = L. pentosus ML 82, encapsulated in bovine cheese whey;

= L. pentosus ML 82, encapsulated in bovine cheese whey;  = L. pentosus ML 82, encapsulated in buffalo cheese whey;

= L. pentosus ML 82, encapsulated in buffalo cheese whey;  = L. plantarum ATCC 8014, encapsulated in bovine cheese whey;

= L. plantarum ATCC 8014, encapsulated in bovine cheese whey;  = L. plantarum ATCC 8014, encapsulated in buffalo cheese whey): a under pH 3.0; b under pH 2.5; c under pH 2.0; d in the presence of bile salts; e in the absence of bile salts. Different letters on top of the bars indicate statistical difference (p ≤ 0.05) in cell viability on the same day of storage

= L. plantarum ATCC 8014, encapsulated in buffalo cheese whey): a under pH 3.0; b under pH 2.5; c under pH 2.0; d in the presence of bile salts; e in the absence of bile salts. Different letters on top of the bars indicate statistical difference (p ≤ 0.05) in cell viability on the same day of storage

On the other hand, higher decrease in viability was observed in the presence of bile salts. Encapsulated bacteria suffered more severely under this condition; they were sometimes even comparable to free cells. This has also been observed in other studies (Huang et al. 2017; Eckert et al. 2017), in which survival rates of CW-encapsulated LAB had a significant reduction in the presence of bile salts. As a matter of fact, this condition is considered a critical point for cell survival under GIT conditions (Ranadheera et al. 2014). This acidic environment along with gastric enzymes such as pepsin, as well as the bile salts secreted in the duodenum, are the major obstacles for probiotic survival in the human organism (Del Piano et al. 2011; Tripathi and Giri 2014). Our results show that CW and BCW provided suitable protection particularly under gastric conditions, but not necessarily so in simulated intestinal tract. Therefore, the different percentage of proteins and lactose between these two materials (Table 1) did not particularly affect their performance as protecting agents against GIT conditions. In other words, higher protein content in BCW was assumed to have allowed better survival of microorganisms under these adverse situations; however, similar CW and BCW results indicate that this was not the case. In fact, low pH and the presence of gastric enzymes may have dissolved the protein coating of capsules, which led to a more significant loss in viability when undergoing intestinal conditions. Even so, encapsulation is clearly advantageous regardless of the material used for microcapsules, because free L. pentosus and L. plantarum had significant reduction in viability compared to encapsulated cells.

Survival in orange juice

Figure 4 shows the survival of free and encapsulated L. pentosus ML 82 and L. plantarum ATCC 8014 stored in commercial orange juice for 90 days. The pH of all samples remained approximately 3.5 throughout the period. Due to low pH, the coating material of the capsules was probably dissolved, which caused a great similarity (p ≤ 0.05) in free and encapsulated bacterial populations in orange juice. In fact, Heidebach et al. (2012) found that microcapsules generated by SD are, in most cases, water soluble, and therefore, cells are rapidly released from their coatings. Even though they were released, bacterial population remained above 7 log CFU/ml in all samples. The resistance of Lactobacillus species to low pH has already been reported by Wu et al. (2014).

Fig. 4.

Cell viability (log CFU/mL) of free and encapsulated bacteria during 90 days of storage in orange juice at 4 °C.  = free L. pentosus ML 82;

= free L. pentosus ML 82;  = free L. plantarum ATCC 8014;

= free L. plantarum ATCC 8014;  = L. pentosus ML 82, encapsulated in bovine cheese whey;

= L. pentosus ML 82, encapsulated in bovine cheese whey;  = L. pentosus ML 82, encapsulated in buffalo cheese whey;

= L. pentosus ML 82, encapsulated in buffalo cheese whey;  = L. plantarum ATCC 8014, encapsulated in bovine cheese whey;

= L. plantarum ATCC 8014, encapsulated in bovine cheese whey;  = L. plantarum ATCC 8014, encapsulated in buffalo cheese whey. Different letters above the bars indicate statistical difference (p ≤ 0.05) in viability between days of storage for the same microorganism and encapsulating agent

= L. plantarum ATCC 8014, encapsulated in buffalo cheese whey. Different letters above the bars indicate statistical difference (p ≤ 0.05) in viability between days of storage for the same microorganism and encapsulating agent

In fact, Lima et al. (2019) found that the daily consumption of orange juice is correlated to the improvement of several health parameters, including increased Bifidobacterium spp. and Lactobacillus spp. populations in gut microflora of the people who participated in this study. The incorporation of LAB probiotic species in orange juice is, therefore, promising. Still, it is worth noting that the efficiency of probiotic bacteria applied in food products depends on the amount ingested (Zhu et al. 2014). The World Health Organization and the Food and Agriculture Organization recommend a minimum amount of 6 log CFU for food to be considered probiotic (FAO/WHO 2002), and the juice samples tested in this study met this requirement. Due to this recommendation, products containing probiotics have significantly increased (Euromonitor International 2016), and yoghurt has been the food the most frequently carries this type of microorganism, although cheese, fruit juices, and cereals are also important carriers (Champagne et al. 2018). Economic reports indicate that the probiotics market reached USD$43 billion in 2017 and is estimated to grow up to USD$59 billion in 2022 (MarketResearch 2016). Therefore, the demand for dried cultures of these microorganisms is expected to increase, and considering whey potential to produce encapsulated probiotic bacteria, the interest in this material may also increase, justifying investments by large industries.

Conclusion

Dairy by-products such as CW are highly pollutant and may represent an environmental problem if discarded inappropriately. Therefore, CW has been widely studied as an encapsulating agent for the protection of probiotic bacteria. Recently, non-bovine sources of CW have gained interest especially due to different protein compositions. CW and BCW were tested as encapsulating agents for the SD of Lactobacillus spp. in this study. To our knowledge, BCW has never been used for this purpose, and this characterizes the main novelty of the present study. Regarding survival after SD, both materials performed similarly, with no significant difference between CW and BCW. During storage, however, CW offered higher protection than BCW, and powder characteristics were better with CW-encapsulated bacteria, especially concerning moisture and water activity. When going through the GIT, BCW-encapsulated L. plantarum ATCC 8014 had higher survival rates, while CW and BCW performed similarly with L. pentosus ML 82. Nonetheless, there was a clear advantage compared to free cells, except when capsules were exposed to bile salts. Finally, when stored in orange juice, both free and encapsulated bacteria were able to maintain viability, especially because low pH may have dissolved the coating materials that protected the bacteria. Therefore, CW and BCW composition did not affect the performance of these two materials as encapsulating agents, and they do offer higher protection to several harmful conditions when encapsulated and free cells are compared, especially during storage and under gastric tract conditions. CW performed better than BCW in this study, forming capsules that were more stable, and were thus able to maintain higher cell viability during storage and under GIT conditions.

Author contributions

All authors contributed with study conception and design. Material preparation, data collection and analysis were performed by AJF and JABSS. The first draft of the manuscript was written by GRRand all authors commented on previous versions of the manuscript. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Funding

We are grateful to Conselho Nacional de Desenvolvimento Científico e Tecnológico (CNPq) for providing the scholarship [Grant: 311655/2017-3]. We also thank Launer Química Indústria e Comércio Ltda, Tecnovates, and Universidade do Vale do Taquari—Univates for their financial support.

Data availability

The authors declare that all data and materials support published claims and comply with field standards.

Compliance with ethical standards

Conflict of interest

The authors declare they have no conflicts of interest.

Footnotes

Gabriela Rabaioli Rama and Ana Júlia Führ have evenly contributed to this paper.

References

- Agostini C, Eckert C, Vincenzi A, et al. Characterization of technological and probiotic properties of indigenous Lactobacillus spp. from south Brazil. 3 Biotech. 2018;8:451. doi: 10.1007/s13205-018-1469-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Angmo K, Kumari A, Savitri BTC. Probiotic characterization of lactic acid bacteria isolated from fermented foods and beverage of Ladakh. LWT Food Sci Technol. 2016;66:428–435. doi: 10.1016/J.LWT.2015.10.057. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- AOAC International . Official methods of analysis of AOAC International. 19. Gaithersburg: AOAC International; 2012. [Google Scholar]

- Asteri I-A, Kittaki N, Tsakalidou E. The effect of wild lactic acid bacteria on the production of goat’s milk soft cheese. Int J Dairy Technol. 2010;63:234–242. doi: 10.1111/j.1471-0307.2010.00564.x. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Behboudi-Jobbehdar S, Soukoulis C, Yonekura L, Fisk I. Optimization of spray-drying process conditions for the production of maximally viable microencapsulated L. acidophilus NCIMB 701748. Dry Technol. 2013;31:1274–1283. doi: 10.1080/07373937.2013.788509. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Brinques GB, Peralba MC, Ayub MAZ. Optimization of probiotic and lactic acid production by Lactobacillus plantarum in submerged bioreactor systems. J Ind Microbiol Biotechnol. 2010;37:205–212. doi: 10.1007/s10295-009-0665-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Buffoni JN, Bonizzi I, Pauciullo A, et al. Characterization of the major whey proteins from milk of Mediterranean water buffalo (Bubalus bubalis) Food Chem. 2011;127:1515–1520. doi: 10.1016/J.FOODCHEM.2011.02.008. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Buzi KA, Pinto JPAN, Ramos PRR, Biondi GF. Microbiological analysis and electrophoretic characterization of mozzarella cheese made from buffalo milk. Ciência e Tecnol Aliment. 2009;29:07–11. doi: 10.1590/S0101-20612009000100002. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Caggia C, De Angelis M, Pitino I, et al. Probiotic features of Lactobacillus strains isolated from Ragusano and Pecorino Siciliano cheeses. Food Microbiol. 2015;50:109–117. doi: 10.1016/J.FM.2015.03.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Carvalho F, Prazeres AR, Rivas J. Cheese whey wastewater: characterization and treatment. Sci Total Environ. 2013;445–446:385–396. doi: 10.1016/J.SCITOTENV.2012.12.038. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Champagne CP, Gomes da Cruz A, Daga M. Strategies to improve the functionality of probiotics in supplements and foods. Curr Opin Food Sci. 2018;22:160–166. doi: 10.1016/J.COFS.2018.04.008. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Chlebowska-Smigiel A, Gniewosz M, Kieliszek M, Bzducha-Wrobel A. The effect of pullulan on the growth and acidifying activity of selected stool microflora of human. Curr Pharm Biotechnol. 2017;18:121–126. doi: 10.2174/1389201017666161229154324. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chlebowska-Śmigiel A, Kycia K, Neffe-Skocińska K, et al. Effect of pullulan on physicochemical, microbiological, and sensory quality of yogurts. Curr Pharm Biotechnol. 2019;20:489–496. doi: 10.2174/1389201020666190416151129. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chudy S, Pikul J, Rudzińska M. Effects of storage on lipid oxidation in milk and egg mixed powder. J Food Nutr Res. 2015;54:31–40. [Google Scholar]

- da Silva PT, Fries LLM, de Menezes CR, et al. Microencapsulation: concepts, mechanisms, methods and some applications in food technology. Ciência Rural. 2014;44:1304–1311. doi: 10.1590/0103-8478cr20130971. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- de Andrade DP, Ramos CL, Botrel DA, et al. Stability of microencapsulated lactic acid bacteria under acidic and bile juice conditions. Int J Food Sci Technol. 2019;54:2355–2362. doi: 10.1111/ijfs.14114. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- De Castro-Cislaghi FP, Silva CDRE, Fritzen-Freire CB, et al. Bifidobacterium Bb-12 microencapsulated by spray drying with whey: survival under simulated gastrointestinal conditions, tolerance to NaCl, and viability during storage. J Food Eng. 2012;113:186–193. doi: 10.1016/j.jfoodeng.2012.06.006. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Del Piano M, Carmagnola S, Ballarè M, et al. Is microencapsulation the future of probiotic preparations? The increased efficacy of gastro-protected probiotics. Gut Microbes. 2011;2:120–123. doi: 10.4161/gmic.2.2.15784. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Domingos-Lopes MFP, Stanton C, Ross PR, et al. Genetic diversity, safety and technological characterization of lactic acid bacteria isolated from artisanal Pico cheese. Food Microbiol. 2017;63:178–190. doi: 10.1016/J.FM.2016.11.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Đorđević V, Balanč B, Belščak-Cvitanović A, et al. Trends in encapsulation technologies for delivery of food bioactive compounds. Food Eng Rev. 2014;7:452–490. doi: 10.1007/s12393-014-9106-7. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Duongthingoc D, George P, Katopo L, et al. Effect of whey protein agglomeration on spray dried microcapsules containing Saccharomyces boulardii. Food Chem. 2013;141:1782–1788. doi: 10.1016/J.FOODCHEM.2013.04.093. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Eckert C, Agnol WD, Dallé D, et al. Development of alginate-pectin microparticles with dairy whey using vibration technology: effects of matrix composition on the protection of Lactobacillus spp. from adverse conditions. Food Res Int. 2018;113:65–73. doi: 10.1016/j.foodres.2018.07.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Eckert C, Serpa VG, Felipe dos Santos AC, et al. Microencapsulation of Lactobacillus plantarum ATCC 8014 through spray drying and using dairy whey as wall materials. LWT Food Sci Technol. 2017;82:176–183. doi: 10.1016/j.lwt.2017.04.045. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Euromonitor International (2016) Probiotics: Evolution of digestion and immune support probiotics. Euromonitor International Global Head of Health and Wellness Research. https://www.euromonitor.com/probiotics-evolution-of-digestion-and-immune-support-probiotics-part-one/report. Accessed 17 Sept 2019

- FAO/WHO Guidelines for the evaluation of probiotics in food. Joint FAO/WHO Work Group Rep Draft Guide Eval Probiot Food. 2002 doi: 10.1111/j.1469-0691.2012.03873. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Farimani RH, Najafi MBH, Bazzaz BSF, et al. Identification, typing and functional characterization of dominant lactic acid bacteria strains from Iranian traditional yoghurt. Eur Food Res Technol. 2016;242:517–526. doi: 10.1007/s00217-015-2562-3. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Favaro-Trindade CS, Santana AS, Monterrey-Quintero ES, et al. The use of spray drying technology to reduce bitter taste of casein hydrolysate. Food Hydrocoll. 2010;24:336–340. doi: 10.1016/J.FOODHYD.2009.10.012. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Ferrando V, Quiberoni A, Reinheimer J, Suárez V. Functional properties of Lactobacillus plantarum strains: a study in vitro of heat stress influence. Food Microbiol. 2016;54:154–161. doi: 10.1016/J.FM.2015.10.003. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Fox PF, Uniacke-Lowe T, McSweeney PLH, O’Mahony JA (2015) Heat-induced changes in milk. In: Dairy Chemistry and Biochemistry. Springer International Publishing, Cham, pp 345–375. 10.1007/978-3-319-14892-2_9

- Gallego-Schmid A, Tarpani RRZ. Life cycle assessment of wastewater treatment in developing countries: a review. Water Res. 2019;153:63–79. doi: 10.1016/J.WATRES.2019.01.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ghandi A, Powell IB, Chen XD, Adhikari B. The Effect of dryer inlet and outlet air temperatures and protectant solids on the survival of Lactococcus lactis during spray drying. Dry Technol. 2012;30:1649–1657. doi: 10.1080/07373937.2012.703743. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Golowczyc MA, Silva J, Teixeira P, et al. Cellular injuries of spray-dried Lactobacillus spp. isolated from kefir and their impact on probiotic properties. Int J Food Microbiol. 2011;144:556–560. doi: 10.1016/j.ijfoodmicro.2010.11.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Greifová G, Májeková H, Greif G, et al. Analysis of antimicrobial and immunomodulatory substances produced by heterofermentative Lactobacillus reuteri. Folia Microbiol (Praha) 2017;62:515–524. doi: 10.1007/s12223-017-0524-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Guergoletto KB, Busanello M, Garcia S. Influence of carrier agents on the survival of Lactobacillus reuteri LR92 and the physicochemical properties of fermented juçara pulp produced by spray drying. LWT. 2017;80:321–327. doi: 10.1016/J.LWT.2017.02.038. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Guerreiro J, Monteiro V, Ramos C, et al. Lactobacillus pentosus B231 isolated from a Portuguese PDO cheese: production and partial characterization of its bacteriocin. Probiotics Antimicrob Proteins. 2014;6:95–104. doi: 10.1007/s12602-014-9157-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Heidebach T, Först P, Kulozik U. Microencapsulation of probiotic cells for food applications. Crit Rev Food Sci Nutr. 2012;52:291–311. doi: 10.1080/10408398.2010.499801. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ho TM, Chan S, Yago AJE, et al. Changes in physicochemical properties of spray-dried camel milk powder over accelerated storage. Food Chem. 2019;295:224–233. doi: 10.1016/J.FOODCHEM.2019.05.122. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Huang S, Rabah H, Jardin J, et al. Hyperconcentrated sweet whey, a new culture medium that enhances Propionibacterium freudenreichii stress tolerance. Appl Environ Microbiol. 2016;82:4641–4651. doi: 10.1128/AEM.00748-16. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Huang S, Méjean S, Rabah H, et al. Double use of concentrated sweet whey for growth and spray drying of probiotics: towards maximal viability in pilot scale spray dryer. J Food Eng. 2017;196:11–17. doi: 10.1016/j.jfoodeng.2016.10.017. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Hugo AA, Bruno F, Golowczyc M. Whey permeate containing galacto-oligosaccharides as a medium for biomass production and spray drying of Lactobacillus plantarum CIDCA 83114. LWT Food Sci Technol. 2016;69:185–190. doi: 10.1016/j.lwt.2016.01.031. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- ITAL . Brasil dairy trends 2020: Tendências do mercado de produtos lácteos. 1. Campinas: ITAL; 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Jeong JJ, Kim KA, Jang SE, et al. Orally administrated Lactobacillus pentosus var. plantarum C29 ameliorates age-dependent colitis by inhibiting the nuclear factor-kappa B signaling pathway via the regulation of lipopolysaccharide production by gut microbiota. PLoS ONE. 2015;10:e0116533. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0116533. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Khem S, Small DM, May BK. The behaviour of whey protein isolate in protecting Lactobacillus plantarum. Food Chem. 2016;190:717–723. doi: 10.1016/j.foodchem.2015.06.020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Khem S, Bansal V, Small DM, May BK. Comparative influence of pH and heat on whey protein isolate in protecting Lactobacillus plantarum A17 during spray drying. Food Hydrocoll. 2016;54:162–169. doi: 10.1016/j.foodhyd.2015.09.029. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Kim S-J, Cho SY, Kim SH, et al. Effect of microencapsulation on viability and other characteristics in Lactobacillus acidophilus ATCC 43121. LWT Food Sci Technol. 2008;41:493–500. doi: 10.1016/J.LWT.2007.03.025. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Lavari L, Ianniello R, Páez R, et al. Growth of Lactobacillus rhamnosus 64 in whey permeate and study of the effect of mild stresses on survival to spray drying. LWT Food Sci Technol. 2015;63:322–330. doi: 10.1016/j.lwt.2015.03.066. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Li L, Han NS (2018) Application of lactic acid bacteria for food biotechnology. In: Emerging Areas in Bioengineering. Wiley-VCH Verlag GmbH & Co. KGaA, Weinheim, Germany, pp 375–398. 10.1002/9783527803293.ch22

- Liao LK, Wei XY, Gong X, et al. Microencapsulation of Lactobacillus casei LK-1 by spray drying related to its stability and in vitro digestion. LWT Food Sci Technol. 2017;82:82–89. doi: 10.1016/j.lwt.2017.03.065. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Lima ACD, Cecatti C, Fidélix MP, et al. Effect of daily consumption of orange juice on the levels of blood glucose, lipids, and gut microbiota metabolites: controlled clinical trials. J Med Food. 2019;22:202–210. doi: 10.1089/jmf.2018.0080. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lira HL, da Silva MCD, Vasconcelos MRS, et al. Microfiltração do soro de leite de búfala utilizando membranas cerâmicas como alternativa ao processo de pasteurização. Ciência e Tecnol Aliment. 2009;29:33–37. doi: 10.1590/s0101-20612009000100006. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Liu Y, Xie XX, Ibrahim SA, et al. Characterization of Lactobacillus pentosus as a starter culture for the fermentation of edible oyster mushrooms (Pleurotus spp.) LWT Food Sci Technol. 2016;68:21–26. doi: 10.1016/j.lwt.2015.12.008. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Maciel GM, Chaves KS, Grosso CRF, Gigante ML. Microencapsulation of Lactobacillus acidophilus La-5 by spray-drying using sweet whey and skim milk as encapsulating materials. J Dairy Sci. 2014;97:1991–1998. doi: 10.3168/jds.2013-7463. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mangia NP, Murgia MA, Garau G, et al. Suitability of selected autochthonous lactic acid bacteria cultures for Pecorino Sardo Dolce cheese manufacturing: influence on microbial composition, nutritional value and sensory attributes. Int J Dairy Technol. 2013;66:543–551. doi: 10.1111/1471-0307.12072. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Marco ML, Heeney D, Binda S, et al. Health benefits of fermented foods: microbiota and beyond. Curr Opin Biotechnol. 2017;44:94–102. doi: 10.1016/j.copbio.2016.11.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- MarketResearch (2016) The world cheese market report 2000–2023. https://pmfood.dk/upl/9735/WCMINFORMATION.pdf. Accessed 17 Sept 2019

- Martín MJ, Lara-Villoslada F, Ruiz MA, Morales ME. Microencapsulation of bacteria: a review of different technologies and their impact on the probiotic effects. Innov Food Sci Emerg Technol. 2015;27:15–25. doi: 10.1016/j.ifset.2014.09.010. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Mollea C, Marmo L, Bosco F. Valorisation of cheese whey, a by-product from the dairy industry. Food Ind. 2013 doi: 10.5772/53159. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Moncmanová A (2007) Environmental factors that influence the deterioration of materials. In: Environmental Deterioration of Materials. WIT Press, United Kingdom, pp 1–25. 10.2495/978-1-84564-032-3/01

- Motta ADS, Gomes MDSM. Technological and functional properties of lactic acid bacteria: the importance of these microorganisms for food. Rev do Inst Laticínios Cândido Tostes. 2015;70:172. doi: 10.14295/2238-6416.v70i3.403. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Nunes GL, Motta MH, Cichoski AJ, et al. Encapsulation of lactobacillus acidophilus la-5 and bifidobacterium bb-12 by spray drying and evaluation of its resistance in simulated gastrointestinal conditions, thermal treatments and storage conditions. Cienc Rural. 2018;48:1–11. doi: 10.1590/0103-8478cr20180035. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Palombo R, Gertler A, Saguy I. A simplified method for determination of browning in dairy powders. J Food Sci. 1984;49:1609–1609. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2621.1984.tb12855.x. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Pérez-Chabela ML, Lara-Labastida R, Rodriguez-Huezo E, Totosaus A. Effect of spray drying encapsulation of thermotolerant lactic acid bacteria on meat batters properties. Food Bioprocess Technol. 2013;6:1505–1515. doi: 10.1007/s11947-012-0865-y. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Pérez Montoro B, Benomar N, Caballero Gómez N, et al. Proteomic analysis of Lactobacillus pentosus for the identification of potential markers of adhesion and other probiotic features. Food Res Int. 2018;111:58–66. doi: 10.1016/j.foodres.2018.04.072. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Picon A, Garde S, Ávila M, Nuñez M. Microbiota dynamics and lactic acid bacteria biodiversity in raw goat milk cheeses. Int Dairy J. 2016;58:14–22. doi: 10.1016/j.idairyj.2015.09.010. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Pinto SS, Fritzen-Freire CB, Benedetti S, et al. Potential use of whey concentrate and prebiotics as carrier agents to protect Bifidobacterium-BB-12 microencapsulated by spray drying. Food Res Int. 2015;67:400–408. doi: 10.1016/J.FOODRES.2014.11.038. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Pinto SS, Verruck S, Vieira CRWW, et al. Influence of microencapsulation with sweet whey and prebiotics on the survival of Bifidobacterium-BB-12 under simulated gastrointestinal conditions and heat treatments. LWT Food Sci Technol. 2015;64:1004–1009. doi: 10.1016/j.lwt.2015.07.020. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Rajam R, Karthik P, Parthasarathi S, et al. Effect of whey protein-alginate wall systems on survival of microencapsulated Lactobacillus plantarum in simulated gastrointestinal conditions. J Funct Foods. 2012;4:891–898. doi: 10.1016/j.jff.2012.06.006. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Rama G, Kuhn D, Beux S, et al. Cheese whey and ricotta whey for the growth and encapsulation of endogenous lactic acid bacteria. Food Bioprocess Technol. 2019;13:308–322. doi: 10.1007/s11947-019-02395-8. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Rama GR, Kuhn D, Beux S, et al. Potential applications of dairy whey for the production of lactic acid bacteria cultures. Int Dairy J. 2019;98:25–37. doi: 10.1016/j.idairyj.2019.06.012. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Ranadheera CS, Evans CA, Adams MC, Baines SK. Effect of dairy probiotic combinations on in vitro gastrointestinal tolerance, intestinal epithelial cell adhesion and cytokine secretion. J Funct Foods. 2014;8:18–25. doi: 10.1016/J.JFF.2014.02.022. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Ranadheera CS, Evans CA, Adams MC, Baines SK. Microencapsulation of Lactobacillus acidophilus LA-5, Bifidobacterium animalis subsp. lactis BB-12 and Propionibacterium jensenii 702 by spray drying in goat’s milk. Small Rumin Res. 2015;123:155–159. doi: 10.1016/j.smallrumres.2014.10.012. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Rodríguez-Huezo ME, Durán-Lugo R, Prado-Barragán LA, et al. Pre-selection of protective colloids for enhanced viability of Bifidobacterium bifidum following spray-drying and storage, and evaluation of aguamiel as thermoprotective prebiotic. Food Res Int. 2007;40:1299–1306. doi: 10.1016/J.FOODRES.2007.09.001. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Rokka S, Rantamäki P. Protecting probiotic bacteria by microencapsulation: challenges for industrial applications. Eur Food Res Technol. 2010;231:1–12. doi: 10.1007/s00217-010-1246-2. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Román A, Wang J, Csanádi J, et al. Experimental investigation of the sweet whey concentration by nanofiltration. Food Bioprocess Technol. 2011;4:702–709. doi: 10.1007/s11947-009-0192-0. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Rushdy AA, Gomaa EZ. Antimicrobial compounds produced by probiotic Lactobacillus brevis isolated from dairy products. Ann Microbiol. 2013;63:81–90. doi: 10.1007/s13213-012-0447-2. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Sales DC, Rangel AHN, Urbano SA, et al. Buffalo milk composition, processing factors, whey constituents recovery and yield in manufacturing Mozzarella cheese. Food Sci Technol. 2017;38:328–334. doi: 10.1590/1678-457x.04317. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Sansonetti S, Curcio S, Calabrò V, Iorio G. Bio-ethanol production by fermentation of ricotta cheese whey as an effective alternative non-vegetable source. Biomass Bioenerg. 2009;33:1687–1692. doi: 10.1016/j.biombioe.2009.09.002. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Sasikumar R, Das M, Sahu JK, Deka SC. Qualitative properties of spray-dried blood fruit (Haematocarpus validus) powder and its sorption isotherms. J Food Process Eng. 2020 doi: 10.1111/jfpe.13373. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Tofalo R, Perpetuini G, Schirone M, et al. Lactobacillus pentosus dominates spontaneous fermentation of Italian table olives. LWT Food Sci Technol. 2014;57:710–717. doi: 10.1016/j.lwt.2014.01.035. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Tonon RV, Brabet C, Pallet D, et al. Physicochemical and morphological characterisation of açai (Euterpe oleraceae Mart.) powder produced with different carrier agents. Int J Food Sci Technol. 2009;44:1950–1958. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2621.2009.02012.x. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Tripathi MK, Giri SK. Probiotic functional foods: survival of probiotics during processing and storage. J Funct Foods. 2014;9:225–241. doi: 10.1016/J.JFF.2014.04.030. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Wang G, Li D, Ma X, et al. Functional role of oppA encoding an oligopeptide-binding protein from Lactobacillus salivarius Ren in bile tolerance. J Ind Microbiol Biotechnol. 2015;42:1167–1174. doi: 10.1007/s10295-015-1634-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wu C, He G, Zhang J. Physiological and proteomic analysis of Lactobacillus casei in response to acid adaptation. J Ind Microbiol Biotechnol. 2014;41:1533–1540. doi: 10.1007/s10295-014-1487-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhu Y-H, Li X-Q, Zhang W, et al. Dose-dependent effects of Lactobacillus rhamnosus on serum interleukin-17 production and intestinal T-cell responses in pigs challenged with Escherichia coli. Appl Environ Microbiol. 2014;80:1787–1798. doi: 10.1128/AEM.03668-13. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Data Availability Statement

The authors declare that all data and materials support published claims and comply with field standards.