Abstract

The ear mite Otodectes cynotis is a parasite of cats and dogs of considerable veterinary importance, being the most common etiological agent of otitis externa in pets. This study investigates the presence of this parasite in 296 cats from Murcia municipality (SE Spain), and describes possible factors associated with the infestation. Cats were grouped by sex, age, lifestyle, season and provenience. Scraping samples were examined by a microscope to identify the mite. Chi square test was computed and odds ratio was used to measure the association of risk factors with parasite prevalence. Additionally, the spatial distribution of prevalences was investigated and represented through GIS software. Around 30% of the cats (CI95 25–35%) were found positives to O. cynotis. The mite infestation was significantly higher in adult cats, during the winter and in individuals from peri-urban areas. The ectoparasite was found to be widely distributed in the cat population of the study area, with an increased risk of infestation in specific peri-urban areas. The results highlight that O. cynotis is a common parasite in areas with Mediterranean semi-arid climate. Given the importance of otodectic mange, and considering that O. cynotis is not a parasite specific to cats, but may also affect dogs and wild carnivores, the information provided by this study is of great value to both pet owners and veterinarian practitioners, and it might help to implement appropriate preventive and control strategies, mainly in free-roaming cats.

Keywords: Free-roaming cat, Ear mite, Risk factors, Spatial distribution, Semi-arid climate, Spain

Otodectes cynotis (Hering 1838) is a parasitic mite (Acari: Psoroptidae) located in the ear canal of cats and dogs. Otodectic mange causes otitis characterized by ceruminous gland hyperplasia (Van der Gaag 1986), which induces intense pruritus, with consequent scratching, self-mutilations and head shaking. It is the main cause of otitis externa in dogs and cats (Lohse et al. 2002; Peregro et al. 2013). Otodectes cynotis has also been described in a broad range of hosts worldwide, including several species of wild carnivores (Lohse et al. 2002; Moriarty et al. 2015). Although it does not represent a major public health problem, self-limiting of otodectic mange has been described in humans. Otodectes cynotis is an obligate ectoparasite, but it is able to survive for several days outside the host, depending on environmental factors (Otranto et al. 2004). The main route of transmission is by direct contact, usually among cats of the same colony (Farkas et al. 2007). Otodectic mange is responsible for more than 50% of the cases of otitis externa in cats (Farkas et al. 2007; Yang and Huang 2016). In severe infestations, O. cynotis cause otitis media, and when ectopic, they often leads to dermatitis on head, neck, tail and trunk (Tonn 1961); however, cats may often be asymptomatic (Sotiraki et al. 2001). Although the parasite affects all types of cats, it has been more often described in cats kept in shelters and in feral cats, since contact with infected animals is more likely (Peregro et al. 2013). Very few studies comparing the presence of O. cynotis in urban and peri-urban cat populations, are currently available. To fill this gap, this study was carried out to gather information on the epidemiology of the disease in urban and peri-urban areas with a semi-arid Mediterranean climate. The ear mite infestation was investigated on 296 cats sacrificed in the period 2005–2007 at “El Centro Municipal de Control de Zoonosis de la ciudad de Murcia” (CMCZ), the main animal shelter for Murcia city and its peri-urban districts (Murcia Region, SE Spain). Most of the cats were feral and free-roaming animals living in colonies, trapped by official municipal services, but also animals left by owners. To prevent the spread of infectious agents, cats are placed in single cages where good hygiene management was applied. Until recently, regional legislation allowed the sacrifice of cats admitted to the CMCZ after a certain period of time. All the animals of our study were sacrificed, according to Spanish law, by the official veterinary services. Based on the postmortem examination, as well as the information provided by the official veterinary services, cats were grouped by sex, age, lifestyle, season and provenience (urban and peri-urban areas). Three classes were considered for age: young (till 6 months old), subadult (between 6 and 12 months old) and adult (more than 12 months old). Regarding lifestyle, the cats were classified in: feral (cats living without human supervision), domestic outdoor (cats with an owner but living most of the time outdoor) and domestic indoor (cats with owner and living most of the time indoor). Immediately after the euthanasia, both ear canals were accurately scraped, and the scraping was examined by a microscope to search and identify the mites according to Sweatman (1958). Chi square test was computed for each category (significance level of 0.05) and odds ratio was used as a measure of the association with risk factors. Statistical analysis was performed using Epi Info™ 7.0 (Dean et al. 2011). The spatial distribution of prevalences was investigated by building a map with QGIS 3.6.0 (QGIS Development Team 2017). Otodectes cynotis was detected in 88 cats out of 296 (30%, CI95 25–35%). Relative prevalence of infestation was evaluated for all the categories (Table 1).

Table 1.

Prevalence of Otodectes cynotis in 296 cats from Murcia municipality (SE Spain) by categories

| Category | Prevalence (%) | CI95 (%) |

|---|---|---|

| Age | ||

| Young | 14 | 3–25 |

| Subadult | 21 | 7–35 |

| Adult | 34 | 28–40 |

| Sex | ||

| Male | 30 | 22–38 |

| Female | 29 | 22–36 |

| Lifestyle | ||

| Feral | 32 | 26–38 |

| Outdoor | 19 | 5–33 |

| Indoor | 29 | 18–40 |

| Season | ||

| Autumn | 27 | 20–34 |

| Winter | 45 | 31–59 |

| Spring | 26 | 16–36 |

| Summer | 30 | 12–49 |

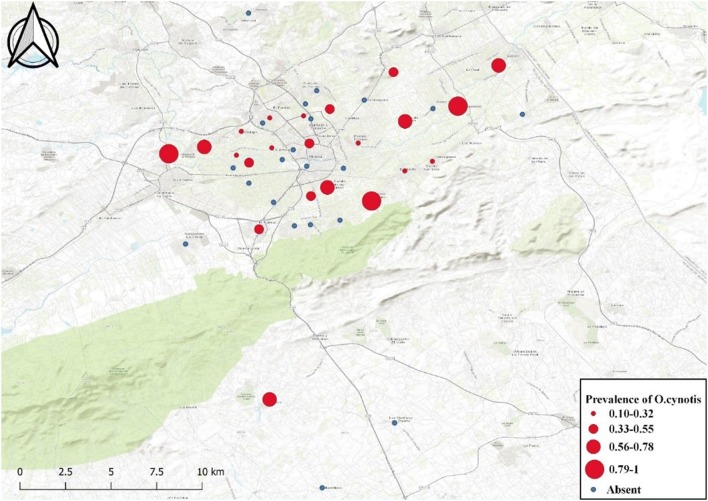

No significant differences were found for lifestyle and sex. On the contrary, the risk of infestation was significantly higher for adult (OR = 2.5, CI95 1.24–4.8) and during winter (OR = 2.2, CI95 1.2–4). The result of spatial analysis showed a higher prevalence in peri-urban districts, rather than in Murcia city (Fig. 1).

Fig. 1.

Prevalence of O. cynotis in 296 cats from urban and periurban areas of Murcia municipality (SE Spain)

In particular, a significant higher risk of parasite occurrence was highlighted in two peri-urban areas: Corvera (OR = 3.5, CI95 1.4–8.6) and Zarandona (OR = 2.5, CI95 0.96–6.57). The present study offers an overview of O. cynotis prevalence in cats from a municipality that includes a clearly urban central area (Murcia city) surrounded by rural communities. The global prevalence observed indicates that O. cynotis is a widespread parasite in the cat population of the study area. This prevalence is higher than the ones found in other on free-roaming cats, ranging from 1% to 10.6% (Coman et al. 1981; Duarte et al. 2010; Montoya et al. 2018). On the contrary, our results are more in line with those described by Sotiraki et al. (2001) in Greece (prevalence of 25.5% in cats), and Akucewich et al. (2002) and Perego et al. (2013), (prevalences of 37% and 55.1% respectively in feral cats in Florida and northern Italy). In accordance with other authors, no significant effect of sex on prevalence has been found (Sotiraki et al. 2001; Perego et al. 2013; Acar and Altinok Yipel 2016). Lifestyle also has no significant effect on risk of infestation. This result, although in line with several authors (Sotiraki et al. 2001; Perego et al. 2013), contradicts with others indicating that infestation is more likely in animals having outdoor access, due to the high infectivity of O. cynotis and the higher contact rate in feral and free-roaming cats (Dégi et al. 2010; Acar and Altinok Yipel 2016). A possible explanation of this contrasting results could be due to the underestimation of the prevalence in studies based on diagnosis of swab samples extracted from the ear canal of live cats or through the detection of mites by otoscopic examination (Lefkaditis et al. 2009). In our study, the detection of O. cynotis mites was done postmortem by microscopic examination of the entire ear canal by scraping, which ensures a high sensitivity of the diagnostic method and reduces the possibility of false negatives. Moreover, it should be noted that Sotiraki et al. (2001) found that 13.6% of indoor cats living without contact with other pets were parasitized by O. cynotis and, in the case of indoor cats sharing household with other pets, the prevalence was 42%. These results highlight that this mite is widely distributed and can appear even in indoor cats without apparent contact with other pets. Based on our results, otodectic scabies seems to be a disease more frequent in urban areas than previously thought, both in stray cats and pet cats. The results of our study indicate that cats living in peri-urban areas have a higher risk of becoming infected by O. cynotis. The rural landscape allows the existence of microclimates that could favor the environmental persistence of the mite, as demonstrated for other parasites (Sanchis-Monsonís et al. 2019). According to Otranto et al. (2004), the mite can survive up to 12 days if the temperature does not exceed 14 °C and relative humidity ranges between 58 and 83%. Its survival decreases rapidly with increasing temperature and dryness. Although the municipality of Murcia present a semi-arid dry climate, the survival of the mite may be favored by the existence of orchards and irrigated areas. In addition, cats in rural areas spend most of their life outside, which facilitates contact rate with other cats (Beugnet et al. 2014) or with other species potentially carrying the mite (Lohse et al. 2002). We have found that prevalence increases significantly with age, which is in line with the results described in previous studies (Lefkaditis et al. 2009; Beugnet et al. 2014; Acar and Altinok Yipel 2016). Infestation in kittens, usually originates from the mother (Farkas et al. 2007), and Lefkaditis et al. (2009) found a higher prevalence in 3-6-month-old kittens than in those less than 3 months old, due to more frequent social interactions. Adult cats have more frequent social bonds; they often sleep in contact with more congeners and mutually rub against each other (Alger and Alger 2003). This leads to a higher contact rate and, therefore, to a higher risk of transmission. In this respect, we must remember that, although the usual location of O. cynotis is the ear canal, infective mites can be found also on the body surface of the cat (Tonn 1961), which would support the hypothesis that transmission is linked to the gregarious behaviour of the cat. Finally, an increased risk of O. cynotis infestation in the winter was observed. Our study area is characterized by mild winters, while the rest of the seasons tend to be drier and warmer. Therefore, in areas with a semi-arid Mediterranean climate, the coldest months may be the most favourable to mite transmission. This could be due to a greater survival of mites on the surface of the host or even outside the host, facilitating the transmission (Otranto et al. 2004). However, further research is needed to determine the influence of environmental conditions on otodectic mange. In conclusion, O. cynotis was found to be present with high prevalence in the cat population of Murcia municipality, with higher risk of infestation in adult cats and in peri-urban areas, and higher number of cases in winter. Today, the legislation of Murcia Region requires municipalities to manage the colonies of stray cats, based on Trap–Neuter–Return programs. This “no-kill” policy cause a proliferation of cat colonies over the last few years. According to the new legislation, it is an obligation of municipalities to control and monitor these colonies. Considering that the presence of cats with this mite infestation poses a health hazard to other animals, whether congeners, dogs or even humans, the identification of colonies, categories and areas at higher risk of mite infestation is pivotal to implement an optimal strategy for the prevention and control of otodectic mange. In this sense, public awareness is advocated, especially in rural areas where the risk of infestation is higher, therefore, specific management is needed.

Acknowledgements

This work was supported by the Ayuntamiento de Murcia (Comunidad Autónoma de la Región de Murcia, Spain).

Author contributions

All authors contributed to the study conception and design. Collection and identification of the parasites was done by Guillermo Doménech, data analysis were performed by Angela Fanelli. The first draft of the manuscript was written by Angela Fanelli. Paolo Tizzani and Carlos Martinéz-Carrasco reviewed the article. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Funding

Not applicable

Compliance with ethical standards

Conflict of interest

None of the authors has any financial or personal relationships that could inappropriately influence or bias the content of the paper.

Ethical approval

Not applicable.

Footnotes

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Angela Fanelli and Guillermo Doménech have contributed equally to this paper.

Contributor Information

Angela Fanelli, Email: angela.fanelli@unito.it.

Paolo Tizzani, Email: paolo.tizzani@unito.it.

Carlos Martínez-Carrasco, Email: cmcpleit@um.es.

References

- Acar A, Altinok Yipel F. Factors related to the frequency of cat ear mites (Otodectes cynotis) Kafkas Univ Vet Fak Derg. 2016;22:75–78. [Google Scholar]

- Akucewich LH, Philman K, Clark A, Gillespie J, Kunkle G, Nicklin CF, Greiner EC. Prevalence of ectoparasites in a population of feral cats from north central Florida during the summer. Vet Parasitol. 2002;109:129–139. doi: 10.1016/S0304-4017(02)00205-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Alger J, Alger S. Cat culture: the social world of a cat shelter. Philadelphia: Temple University Press; 2003. p. 256. [Google Scholar]

- Beugnet F, Bourdeau P, Chalvet-Monfray K, Cozma V, Farkas R, Guillot J, Halos L, Joachim A, Losson B, Miró G, Otranto D, Renaud M, Rinaldi L. Parasites of domestic owned cats in Europe: co-infestations and risk factors. Parasit Vectors. 2014;7:291. doi: 10.1186/1756-3305-7-291. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Coman BJ, Jones EH, Driesen MA. Helminth parasites and arthropods of feral cats. Aust Vet J. 1981;57:324–327. doi: 10.1111/j.1751-0813.1981.tb05837.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dean AG, Arner TG, Sunki GG, Friedman R, Lantinga M, Sangam S, Zubieta JC, Sullivan KM, Brendel KA, Gao Z, Fontaine N, Shu M, Fuller G, Smith DC, Nitschke DA, Fagan RF (2011) Epi InfoTM, a database and statistics program for public health professionals

- Dégi J, Cristina RT, Codreanu M. Researches regarding the incidency of infestation with Otodectes cynotis in cats. Vet Med. 2010;56:84–92. [Google Scholar]

- Duarte A, Castro I, Pereira da Fonseca IM, Almeida V, Madeira de Carvalho LM, Meireles J, Fazendeiro MI, Tavares L, Vaz Y. Survey of infectious and parasitic diseases in stray cats at the Lisbon Metropolitan Area, Portugal. J Feline Med Surg. 2010;12:441–446. doi: 10.1016/j.jfms.2009.11.003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Farkas R, Germann T, Szeidemann Z. Assessment of the Ear Mite (Otodectes cynotis) Infestation and the Efficacy of an Imidacloprid plus Moxidectin Combination in the Treatment of Otoacariosis in a Hungarian Cat Shelter. Parasitol Res. 2007;101:35–44. doi: 10.1007/s00436-007-0609-5. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Lefkaditis MA, Koukeri SE, Mihalca AD. Prevalence and intensity of Otodectes cynotis in kittens from Thessaloniki area, Greece. Vet Parasitol. 2009;163:374–375. doi: 10.1016/j.vetpar.2009.04.027. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lohse J, Rinder H, Gothe R, Zahler M. Validity of species status of the parasitic mite Otodectes cynotis. Med Vet Entomol. 2002;16:133–138. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2915.2002.00355.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Montoya A, García M, Gálvez R, Checa R, Marino V, Sarquis J, Barrera JP, Rupérez C, Caballero L, Chicharro C, Cruz I, Miró G. Implications of zoonotic and vector-borne parasites to free-roaming cats in central Spain. Vet Parasitol. 2018;251:125–130. doi: 10.1016/j.vetpar.2018.01.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Moriarty ME, Vickers TW, Clifford DL, Garcelon DK, Gaffney PM, Lee KW, King JL, Duncan CL, Boyce WM. Ear mite removal in the Santa Catalina Island fox (Urocyon littoralis catalinae): controlling risk factors for cancer development. PLoS ONE. 2015;10(12):e0144271. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0144271. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Otranto D, Milillo P, Mesto P, De Caprariis D, Perrucci S, Capelli G. Otodectes cynotis (Acari: Psoroptidae): examination of survival off-the-host under natural and laboratory conditions. Exp Appl Acarol. 2004;32:171–179. doi: 10.1023/B:APPA.0000021832.13640.ff. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Perego R, Proverbio D, Bagnagatti De Giorgi G, Della Pepa A, Spada E. Prevalence of otitis externa in stray cats in northern Italy. J Feline Med Surg. 2013;16(6):483–490. doi: 10.1177/1098612X13512119. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- QGIS Development Team (2017) QGIS geographic information system. Open Source Geospatial Foundation

- Sanchis-Monsonís G, Fanelli A, Tizzani P, Martínez-Carrasco C. First epidemiological data on Spirocerca vulpis in the red fox: a parasite of clustered geographical distribution. Vet Parasitol Reg Stud Rep. 2019;18:100338. doi: 10.1016/j.vprsr.2019.100338. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sotiraki ST, Koutinas AF, Leontides LS, Adamama-Moraitou KK, Himonas CA. Factors affecting the frequency of ear canal and face infestation by Otodectes cynotis in the cat. Vet Parasitol. 2001;96:309–315. doi: 10.1016/S0304-4017(01)00383-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sweatman GK. Biology of Otodectes cynotis, the ear canker mite of carnivores. Can J Zool. 1958;36:849–862. doi: 10.1139/z58-072. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Tonn RJ. Studies on the ear mite Otodectes cynotis, Including life cycle. Ann Ent Soc Am. 1961;54:416–421. doi: 10.1093/aesa/54.3.416. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Van der Gaag I. The pathology of the external ear canal in dogs and cats. Vet Quart. 1986;8:307–317. doi: 10.1080/01652176.1986.9694061. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yang C, Huang HP. Evidence-based veterinary dermatology: a review of published studies of treatments for Otodectes cynotis (ear mite) infestation in cats. Vet Dermatol. 2016;27(4):221-e56. doi: 10.1111/vde.12340. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]