Abstract

Rats are recognized as reservoir hosts of several pathogens that pose a threat to human health. Although rats are reported to be hosts of a large number of pathogens, a survey of Capillaria hepatica carried by rats in various settings such as residential, agroforestry, and agricultural areas in the Philippines has not been conducted. A total of 90 rats composed of Rattus norvegicus, Rattus tanezumi, and Rattus exulans were collected through trapping in selected residential, agroforestry, and agricultural areas in Los Baños Laguna, Philippines. The overall prevalence of C. hepatica among rats was 21.11%. Among the rat species collected, R. norvegicus showed the highest prevalence (55.56%), followed by R. exulans (14.29%), then R. tanezumi (5.36%) (differences significant at p < 0.05). Moreover, residential areas had the highest prevalence of C. hepatica infection (50%), followed by agroforestry and agricultural areas at 6.7% each (significant at p < 0.05). However, the difference in C. hepatica infection between male (11.43%; 4/35) and female (27.27%; 15/55) rats was not significant (p > 0.05). Most of the infected rats were moderately infected (68.42%), while few were lightly and severely infected (15.78% each). Lastly, the presence of C. hepatica in liver is suggestive of presence of lymphocytes, amyloid, granuloma, and the occurrence of necrosis, hypertrophy, fibrosis, and cholestasis in the liver of the host. Capillariasis could be occurring in Philippine human populations, hence there is need for screening the population with appropriate means and to create awareness of this emerging disease.

Keywords: Capillaria hepatica, Liver, Rats, Philippines, Prevalence, Histopathology

Introduction

Rats play an important ecological role in terrestrial ecosystems (Aplin et al. 2003). However, due to anthropogenic impacts such as land use, habitat and biodiversity loss, these animals tend to move to human habitations (Salibay and Luyon 2008). Rattus spp. are known as agricultural pests which feed on crops and damage properties (Aplin et al. 2003). They are also known as vectors of many pathogenic bacteria and serve as carriers of ectoparasites, and reservoir hosts of zoonotic parasites (Singla et al. 2013). The commonly widespread rats and continuously growing in number in the Philippines are Brown rats (Rattus norvegicus), Pacific rats (Rattus exulans), and Asian house rats (Rattus tanezumi) (Heaney et al. 1998). These rats are categorized as least concern in International Union for Conservation of Nature (IUCN) (Salibay and Luyon 2008).

Rats are capable of transmitting Capillaria hepatica. Capillaria hepatica causes hepatic capillariasis with no specific signs or symptoms in the host, but can manifest as acute or subacute hepatitis, hypereosinophilia, anemia, chronic fever which can even become fatal without proper treatment (Aghdam et al. 2015). Thiabendazole and Albendazole are the drugs used to treat hepatic capillariasis. Moreover, diagnoses for hepatic capillariasis include liver biopsy, needle biopsy, or autopsy (Centers for Disease Control and Prevention 2012). On the other hand, analyzing stool samples for C. hepatica is not applicable due to its complex life cycle.

Capillaria hepatica is a nematode known to have a complex life cycle since eggs are known to be liberated and infective via the decay of an infected host (natural death) or through digestion of the liver of an infected host either by another organism or the same species (cannibalism) (Farhang-Azad 1977). The female C. hepatica deposits its unembryonated eggs along sinous tracts in the liver, which eventually become encapsulated as an immune reaction of the host resulting to hepatic fibrosis (Mowat et al. 2009; De Souza et al. 2006; Oliveira et al. 2004). On the other hand, infective eggs or embryonated eggs hatch in the intestine of the organism releasing the larvae. The larvae then migrates to the liver via the portal vein and takes about a month to mature sexually and mate (Centers for Disease Control and Prevention 2016).

Furthermore, C. hepatica has a broad host range consisting of at least eighty (80) species of rodents of family Muridae and infecting at least 24 other mammalian families including humans have been reported (Fuehrer et al. 2011). Despite being distributed almost worldwide and in a wide range of reservoir hosts, only 163 reported cases of infection of C. hepatica in humans consisting of 72 reports of hepatic capillariasis, 13 reports of confirmed infection serologically, and 78 cases of spurious infection have been gathered (Fuehrer et al. 2011). Spurious infections where humans ingest unembryonated eggs of C. hepatica that are eventually released via the feces were recorded more than the hepatic capillariasis itself. It is because hepatic capillariasis has a tendency to be misdiagnosed as hepatic coccidiosis and other liver diseases such as hepatitis A, B, or C, and leptospirosis due to its common symptoms (Mowat et al. 2009; Li et al. 2010; Da Rocha et al. 2015). Since C. hepatica symptoms are commonly misdiagnosed, it is of importance to study its epidemiology, particularly its prevalence in rat hosts that now co-inhabit with humans.

Although C. hepatica infection is reported to be common among rats, C. hepatica infection among Rattus spp. found in the Philippines has not been fully understood. Furthermore, there were no reported cases of C. hepatica infections in humans in the country although this absence could either be a result of underreporting or misdiagnosis. Horiuchi et al. (2013), however, reported the presence of Capillaria sp. eggs in soil from Los Baños Laguna. Hence, the present study was conducted to contribute as baseline information on C. hepatica infection and its histopathological features in Rattus spp. collected in the Philippines.

Materials and methods

Ethical considerations

Prior to the conduct of study, the Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee (IACUC) of the University of the Philippines Los Baños approved the experimental protocol with assigned protocol number IBS-2016-01.

Study site

Los Baños is a home to a variety of terrestrial ecosystems such as agricultural, residential, and forest reserve (Fig. 1). The Mount Makiling Forest Reserve (MFR) comprises a large part of Los Baños (Magcale-Macandog et al. 2011). Mt. Makiling has a remarkable record of faunal and flora diversity which is why it is listed as one of the hotspots in the Philippines (Salibay and Luyon 2008). MFR is a home to 59 endemic avian species, 52 species of reptilian, and 25 species of amphibian. On the other hand, rodents and bats are found to be the most diverse groups. MFR is also a home to 15 endemic species of angiosperms and almost to an estimated 2038 species, 19 sub-species, 167 varieties, and many cultivars of flowering plants and ferns (Lapitan et al. 2013). And although there are municipal ordinances on waste management, poor hygiene and sanitation are still observed in adjacent areas of MFR, particularly near human habitations.

Fig. 1.

Land cover of Los Baños Laguna, Philippines

Sampling design and sample collection

The study secured permits from Makiling Center for Mountain Ecosystems (MCME) and from barangays for collection of samples in selected sampling sites. Ocular inspection of potential sampling sites was also conducted before data sampling. A random number generator was used to determine ten (10) sampling points each separated by a 500-m distance to avoid pseudoreplication. A total of 90 wild Rattus spp. were collected using baited live traps and snap traps from MFR and its adjacent areas. Two (2) lab-bred rats (Sprague–Dawley) were used as control for the histology of rat liver.

Sampling size was computed using Gpower 3 Statistical Software with a predicted prevalence of 35% of C. hepatica at 80% statistical power and 95% confidence level. To increase the precision of the sample, a total of 90 rats were collected, 30 each from the various sites namely—agroforest in MFR, residential and agricultural areas adjacent to MFR.

The traps were set in the afternoon and were collected the next day to check for presence of rats. Animals other than Rattus spp. were released. Trapped rats were immediately transported to the laboratory prior to sedation and dissection. IACUC protocol was followed in euthanizing the rats by using isoflurane as an inhalant anaesthesia followed by cervical dislocation.

Collection and processing of parasite

Biometrics, sex, and morphological appearance of the sedated rats were recorded by measuring the body weight, body length, tail length, ear length, and hind foot length. The rats were dissected and their livers were collected. Gross inspection for the presence of C. hepatica was done through the presence of milky spots on the lobes of the liver. In addition, the livers were subjected to artificial digestion, using pepsin-HCl solution, to further confirm the presence of adult worms and/or eggs of C. hepatica using light microscope. Worm from the lesions of the liver was also mounted on slides for further confirmation of C. hepatica infection.

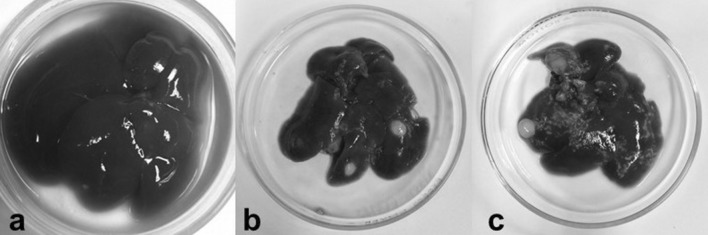

Relative intensity of infection with C. hepatica was recorded as light, moderate, and severe infections following the characterization used by Childs et al. (1988). Infections were considered as light if only a single lobe of liver is parasitised and discrete lesions were observed. It is graded moderate if more than one lobe of liver is involved and less than 50% of the whole liver is infected. Lastly, it is graded as severe if two or more lobes of liver are infected and more than 50% of the liver is parasitized (Fig. 2).

Fig. 2.

Relative intensity of C. hepatica infection as characterized by Childs et al. (1988). a Light, b Moderate, c Severe

Histological processing of liver samples

A portion of the infected liver tissues was excised for histological processing. The samples were placed in individual containers with fixative using Bouin’s solution and were properly labeled. Standard protocol for histological preparations was followed which included washing, dehydration with increasing grade of alcohol, clearing, embedding, and sectioning. The tissues were sectioned at 5 μm, stained with hemotoxylin and eosin, and were mounted and observed under light microscope at low power and high power magnification for histological observations. The pathological manifestations of C. hepatica on the histology of the livers of the Rattus spp. were recorded. In addition, histological sections of liver tissues from control rats were observed and recorded for comparison with the infected and uninfected tissues.

Data analyses

Shapiro–Wilk Normality test was used to determine the normality of the data collected in the study. Chi square test of independence was used to compare the prevalence of C. hepatica between sexes of rats, and among various sampling sites. On the other hand, Fisher’s exact test was used to compare the prevalence of C. hepatica infection among sites and among species of rats. The Fisher’s exact test was also used to compare the relative intensity of C. hepatica among rat species, among various sampling sites, and between sexes of rats. Inferential statistics was analyzed using IBM SPSS software version 25, Rstudio Version 1.0.136, and Quantitative Parasitology version 3.0.

Prevalence and Relative Abundance were computed as follows:

All data were analyzed at 95% level of confidence. Lastly, descriptive characterization of the histological sections of C. hepatica-infected and uninfected liver of rats was done to record possible effects of the parasite to the host.

Results and discussion

Rattus spp. collected

A total of 90 rats were collected (from July 2017 to February 2018) in MFR and its adjacent areas such as residential and agricultural areas in Los Baños, Philippines. Three species of rats were collected and identified namely—R. norvegicus, R. tanezumi, and R. exulans. Morphological differences (body length, tail length, ear length, hindfoot length, and the color of the fur) were considered in identifying the species of rats. During the experiment, two Rattus everetti were trapped from agroforest in MFR. They were released immediately as this species is included in the IUCN’s red list as this is endemic to the Philippines. Shrews, mice, and frogs were also occasionally caught during the collection of samples and were released immediately.

Twenty-seven R. norvegicus was collected and based from the results, R. norvegicus was collected only from residential areas. According to Brooks et al. (1987) and Traweger et al. (2006), these rats are known to inhabit areas with poor waste management and sanitation. These species are also known to prefer living in proximity to ponds, rivers, and sewers. Furthermore, Aplin et al. (2003) stated that R. norvegicus possess a high reproduction rate, and adaptive and opportunistic behavior which enabled them to successfully live, inhabit, and survive in communities especially in urban areas. These rats are also known to feed on human refused and stored food and cause damage to human properties such as furniture and clothes. Presence of R. norvegicus in some of the residential areas of the study may imply poor waste management and sanitation. On the other hand, absence of these rats in agroforestry and agricultural areas suggests that these areas are of good waste management and sanitation.

Meanwhile, R. tanezumi was found from all the sampling sites. Fifty-six (56) R. tanezumi was collected—three (3) from residential areas, thirty (30) from agroforestry, and twenty-three (23) from agricultural areas. Along with R. norvegicus, R. tanezumi is increasingly found in human habitations or in disturbed places like urban areas due to conversion of lowland forests to agricultural lands (Heaney et al. 1999; Salibay and Claveria 2005; Sumangali et al. 2012). However, R. tanezumi was also found in agroforestry and agricultural areas. According to Singleton (2003), R. tanezumi can feed on human stored food, rice crops, and other plants making it abundant in all the sites. It can feed on almost anything but mostly, it feeds on rice crops and other plants which makes it an agricultural pest. Additionally, Aplin et al. (2003) described R. tanezumi as opportunistic since a relationship between the rice crop maturation and harvesting, and its abundance has been found in the Philippines. Singleton (2003) stated that the damage R. tanezumi cause by feeding on rice crops causes a significant annual yield loss to the Philippines.

On the other hand, seven (7) R. exulans was only captured in agricultural areas together with R. tanezumi since R. exulans are known to feed on mostly rootcrops, rice, coconut, corn, fruits, and sugarcane (Aplin et al. 2003). According to Aplin et al. (2003) R. exulans has been reported as a significant field pest of rice crops. The factors that may have influenced the observed distribution of R. norvegicus, R. tanezumi, and R. exulans are their preferred food or diet, the availability of the preferred food, the behavior and ability of these rats to utilize different sites or habitats.

Prevalence and relative intensity of C. hepatica in Rattus spp.

Capillaria hepatica was observed from the livers of 19 rats collected (Fig. 3a). The presence of yellowish to milky lesions on the surface of the liver suggests the presence of C. hepatica (Ceruti et al. 2001). Further confirmation of C. hepatica is seen in Fig. 3b showing the typical bipolar striated eggs inside the body of C. hepatica. Livers showing no lesions were identified as uninfected. Artificially digested livers showing absence of the typical bipolar striated eggs and worm were also identified as uninfected.

Fig. 3.

R. norvegicus liver infected with C. hepaticaa Yellowish lesions (yellow arrow) at the surface of liver suggesting the presence of C. hepatica, bC. hepatica with eggs (red arrow) inside (400×) obtained from an infected liver. Note the presence of striations and bipolar plugs as diagnostic feature of its egg (color figure online)

Prevalence and relative intensity of C. hepatica infection among rat species

Prevalence of C. hepatica infection in relation to the specific rat species collected from various sampling sites is shown in Table 1. The overall prevalence of C. hepatica infection in MFR and its adjacent areas was 21.11% (19/90), where the highest infection was observed in R. norvegicus (55.6%), followed by R. exulans (14.29%), and lastly R. tanezumi (5.36%). The comparison of prevalence of C. hepatica among different rat species is statistically significant at p = 7.377 × 10−7.

Table 1.

Prevalence of C. hepatica infection of Rattus spp. from various sites in MFR and its adjacent areas

| Species | Prevalence (%) | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Residential (n = 30) | Agroforestry (n = 30) | Agricultural (n = 30) | Total (P%)* | |

| R. norvegicus (n = 27) | 55. 6 (15) | – | – | 55.6 (15) |

| R. tanezumi (n = 56) | 0 | 6.67 (2) | 4.35 (1) | 5.36 (3) |

| R. exulans (n = 7) | – | – | 14.29 (1) | 14.29 (1) |

| Total P(%)** | 50 (15) | 6.67 (2) | 6.67 (2) | 21. 11 (19) |

*Statistically significant at p < 0.05

**Statistically significant at p < 0.05, X2= 22.55

Among the rat samples collected, R. norvegicus had the highest prevalence for C. hepatica infection. R. norvegicus is considered as a primary host and a reservoir host of C. hepatica in Eurasia (Ceruti et al. 2001; Spratt and Singleton 2001). Rattus norvegicus has been known to be commonly infected by C. hepatica according to the studies conducted in other countries such as in USA (Childs et al. 1988), in Malaysia (Sinniah et al. 1979; Shafiyyah et al. 2012), in Crotia (Stojcevic et al. 2004), and also in Norway (Farhang-Azad 1977). The reported prevalence of C. hepatica infection among R. norvegicus has varied from 11 to 88% (Easterbrook et al. 2007; Kataranovski et al. 2010). Furthermore, according to Luttermoser (1938) and Layne (1968), C. hepatica infection causes low pathogenicity to R. norvegicus but exhibits a high prevalence, which suggests the role of R. norvegicus as the reservoir host of this parasite. In addition, these rat species are known to thrive in places lacking sanitation or proper waste disposal making them the perfect host or vectors of certain parasites (Baker 2008). As described by Shaffiyah et al. (2012), R. norvegicus are opportunistic and highly adaptive to a wide range of conditions enabling them to successfully inhabit and survive in urban areas. Since R. norvegicus was relatively the most abundant in residential areas, it is possible that it was the species of rats that was most infected and had encountered C. hepatica in this study. Twenty-seven (27) adult rats of this species may have provided a sufficient number of host and favored the transmission and life cycle of the life cycle of C. hepatica.

As for the relative intensity, Table 2 shows that among the collected R. norvegicus, 12 (44.44%) have moderate infection while three (11.11%) have a severe infection. On the other hand, the only infected R. exulans has light infection while the infected R. tanezumi have light and moderate infection. Fisher’s Exact Test revealed that there is significant difference among the association of intensity of C. hepatica infection with the species of rats at p = 0.01058. This highly aggregated pattern of distribution of parasites could be a strategy of the parasites to keep a healthy host population (Baker 2008). If all the individual hosts are heavily infected, this could pose a threat to the survival of the parasites—endangered host means endangered parasite. This may also explain the high proportion of uninfected hosts in this study.

Table 2.

Relative intensity (%) of C. hepatica infection among Rattus spp. from various sites in MFR and its adjacent areas

| Species | Uninfected | Relative intensity (%) | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Light | Moderate | Severe | ||

| R. norvegicus (n = 27) | 44.44 | 0 | 44.44 | 11.11 |

| R. tanezumi (n = 56) | 94.64 | 1.79 | 5.71 | 0 |

| R. exulans (n = 7) | 85.71 | 14.29 | 0 | 0 |

| Total* | 78.89 | 15.79 | 68.42 | 15.79 |

*Statistically significant at p < 0.05

Prevalence and intensity of C. hepatica infection among different sites

The overall prevalence of C. hepatica infection among the sites regardless of rat species is shown in Table 3. Residential areas had the highest prevalence of C. hepatica infection with 15 infected rats (50%) followed by both the agroforestry and agricultural areas with 2 rats infected (6.7%). The difference in the prevalence of C. hepatica infection among the sites was significant at p = 2.554 × 10−5. The same results were observed in the study of Shafiyyah et al. (2012) wherein C. hepatica was prevalent in urban areas. Furthermore, Shafiyyah et al. (2012) observed poor hygiene and sanitation in the site where they conducted their study. R. norvegicus was relatively the abundant rat species in residential areas near MFR. R. norvegicus according to Brooks et al. (1987) and Traweger et al. (2006), are known to thrive in places lacking sanitation or proper waste disposal. This may indicate that the relative abundance of R. norvegicus in residential areas reflects the sanitation and waste management of the area.

Table 3.

Prevalence and relative intensity of C. hepatica infection of rats from different sites in MFR and its adjacent areas

| Site | Prevalence (%) | Relative intensity (%) | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Light | Moderate | Severe | ||

| Residential (n = 30) | 50 (15) | – | 40 (12) | 10 (3) |

| Agroforestry (n = 30) | 6.67 (2) | 6.67 (2) | – | – |

| Agricultural (n = 30) | 6.67 (2) | 3.33 (1) | 3.33 (1) | – |

| Total (N = 90)* | 21.11 | 15.79 | 68.42 | 15.79 |

*Statistically significant at p < 0.05

The observed presence of the paratenic hosts of C. hepatica such as dogs, cats, humans, and others in residential areas possibly contributed to the prevalence of infection through interspecific and intraspecific interactions such as predation and cannibalism, respectively. Through these interactions, eggs of C. hepatica are readily released into the environment. The possible paratenic hosts may have contributed to the spreading of C. hepatica and therefore, provide continuity to its life cycle and transmission.

With regards to the relative intensity, 15.79% (3/19) of the infected rats had an intensity of light, then 68.42% (13/19) of the infected rats had an intensity of moderate, and 15.79% (3/19) of the infected rats had an intensity of severe as seen in Table 3. Moreover, most of the infection was observed in residential areas particularly having a moderate infection. Fisher’s Exact Test revealed that there is a significant difference in the relative intensity of C. hepatica infection in relation to the sites where the infected rats were collected at p = 0.01058.

Most of the infection was seen in residential areas due to the presence of the rats (R. norvegicus) susceptible to C. hepatica infection as well as the presence of paratenic hosts such as cats and dogs. Previous studies showed that a moderate infection, as observed in this research, was intended for maintaining a healthy population among the host (Baker 2008). By maintaining the population, the chance of disseminating and transmitting the eggs of C. hepatica is ensured.

Prevalence and relative intensity of C. hepatica infection of Rattus spp. in relation with sex

There were 55 female rats and 35 male rats collected from the sampling sites. 15 female rats out of 55 (27.27%) and 4 male rats out of 35 (11.43%) were infected (see Fig. 4). However, there was no significant difference for C. hepatica prevalence between females and males of Rattus spp., p > 0.05, X2 = 3.224. Meanwhile, the relative intensity of infection was mostly moderate for both infected male (50%) and female rats (73.33%). However, most of the collected rats were uninfected (71%). Among the male rats infected, 25% (1/4) had a light infection as well as moderate one. On the other hand, 73.33% (11/15) females had a moderate infection while 13.33% (2/15) had a light as well as severe infection. Yet, the difference between the relative intensities of C. hepatica infection between the sexes was not significant. The data suggested that C. hepatica has no sex preference among the rats examined because there is no association observed between C. hepatica infection and sex. Resendes et al. (2009), Simões et al. (2014), Ceruti et al. (2001) and Kataranovski et al. (2010) have similar findings showing that sex was not associated with the intensity and prevalence of C. hepatica infection.

Fig. 4.

Prevalence and relative intensity of C. hepatica infection between 35 male and 55 female rats (not significant, p > 0.05)

Based from the results obtained, infection with C. hepatica in rats appeared to be influenced by the specific type of rat species and its particular habitat. Residents in the residential areas where the rats were collected can be at risk of C. hepatica infection as rodents serve as museum of zoonotic infections (Singla et al. 2013). Therefore, improvement of rat control, sanitation, and waste management is a must to prevent transmission of C. hepatica.

Histopathology of C. hepatica-infected liver of Rattus spp.

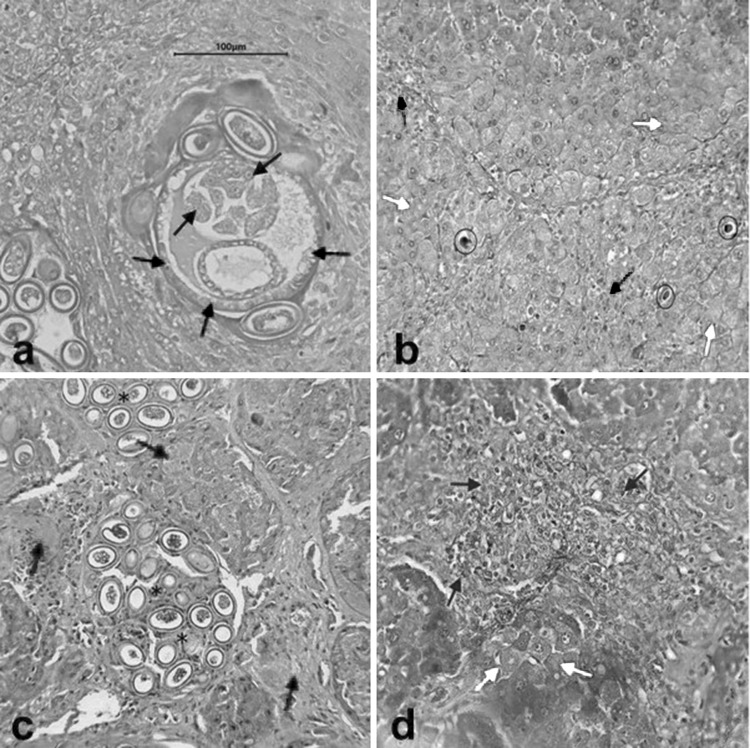

Liver is known for its different functions for metabolism, excretion, bile secretion, and digestion (Silbernagl et al. 2009). A normal liver is described with hepatocytes or liver cells radiating from each central vein. The irregular spaces between the hepatocytes are known as hepatic sinusoids (Thoolen et al. 2010). Figures 5 and 6 show the manifestations of the presence of C. hepatica in the livers of the rats collected. The presence of C. hepatica was further confirmed from histological sections by the presence of sections of an adult worm and the scattered and clustered typical bipolar striated eggs in the infected livers (Fig. 5). Possible presence of lymphocytes, amyloid, granuloma and occurrence of fibrosis, hypertrophy, cholestasis, and necrosis were also observed in C. hepatica-infected livers (see Figs. 5, 6).

Fig. 5.

Cross section of an infected liver showing a an adult worm and its stichocytes (black arrow) and bacillary bands (red arrow), b Councilman bodies (encircled), necrotic hepatocytes (green arrow), and hypertrophic hepatocytes (yellow arrow), c clustered C. hepatica eggs (asterisk) and amyloid deposition (orange arrow), d accumulation of bile (blue arrow) within the liver and presence of hypertrophic hepatocytes (yellow arrow) (400×) (color figure online)

Fig. 6.

Fibrosis (F) and presence of granuloma (G) consisting of lymphocytes (asterisk) in a uninfected liver of Capillaria hepatica and bC. hepatica-infected liver showing carcass (black arrow) of C. hepatica eggs (400×)

Presence of stichocytes and bacillary bands were observed in a sectioned adult of C. hepatica (Fig. 5a). According to Wright (1961), stichocytes and bacillary bands is one of the morphological characteristics of capillarids including C. hepatica. He also stated that bacillary bands are narrow lateral bands that extend to the entire length of the body while stichocytes are thin, muscular cells surrounding the esophagus of an adult worm. Bacillary bands are composed of cuticular pores, each glandular cell located in the hypodermis suggesting its function in formation of cuticle and role in ion regulation (Gutierrez 2000). Meanwhile, stichocytes contain mitochondira and golgi apparatus suggesting its secretory function. Miliotis and Bier (2003) stated that stichocytes are used for secreting antigenic material effective in inducing an immune response in the host.

The occurrence of necrosis, fibrosis, and other cells such as leukocytes were the possible response of the host to the infection of C. hepatica. Figure 5b shows hepatocytes each with smaller and condensed nucleus. According to Young et al. (2009), dead hepatocytes are stained pink due to degeneration of structural proteins. On the other hand, smaller and condensed nucleus is a result of progressive chromatin clumping as a result of reduced pH from terminal anaerobic metabolism of the cells. The shrinking and condensing of the nucleus of the hepatocytes as well as the early cytoplasmic vacuolation is also known as pyknosis (Young et al. 2009). Hepatocytes that underwent pyknosis are known as Councilman bodies. Pyknotic hepatocytes undergo necrosis or cell death. According to Thoolen et al. (2010), necrotic hepatocytes (black arrow) on the other hand, are dead hepatocytes that lost their cytoplasmic and nuclear details. The presence of C. hepatica worm and its eggs may have caused necrosis.

Swollen hepatocytes or liver cells that undergone hypertrophy were also observed (Fig. 5b). Hypertrophy is a condition characterized by an increase in size of cells. According to Young et al. (2009), this is caused by the accumulation of water of the cells due to the incapacity of the cells to maintain the balance between the ions and fluids. Presence of C. hepatica worms and its eggs in the liver parenchyma may have blocked the normal flow of ions and fluids resulting to swelling of hepatocytes. Severe cases of hypertrophy may lead to hepatomegaly or the abnormal enlargement of the liver (Young et al. 2009).

Meanwhile, the appearance of C. hepatica-infected rat liver suggested deposition of amyloid protein (Fig. 5c). Amyloidosis is a condition characterized by extracellular deposition of the protein amyloid (Young et al. 2009). It is a pink-staining ribbon-like deposit within the hepatic sinusoids. Amyloid may be deposited in tissues and/or in organs. In hepatic amyloidosis, amyloid is deposited in the space of Disse, between sinuoidal lining cells and the hepatocytes (Young et al. 2009). This is caused by the enlargement of the liver (hepatomegaly). As mentioned earlier, one of the observed manifestations of C. hepatica infection was hypertrophy (Fig. 5b) that may have induced the observed amyloidosis. According to Shin (2011), this condition may cause hepatic failure and portal hypertension. Shin (2011) added that severe cases in humans might be fatal especially when heart or kidney is involved.

On the other hand, Fig. 5d is suggestive of cholestasis showing bile (brown stained within the parenchyma of the liver). Cholestasis as described by Young et al. (2009) is the accumulation of bile within the liver as a consequence of obstruction of the bile flow. Obstruction might be due to the presence of eggs and the worm itself within the parenchyma of the liver, presence of dead or scarred hepatocytes, and hypertrophic or swollen cells. Young et al. (2009) also added that cholestasis is a common feature of liver damage caused by a destroyed bile duct or by hepatocytes that are unable to secrete bile.

Meanwhile, the uninfected C. hepatica liver showed evidence of immunologic response of the host (Fig. 6a). The liver was identified as uninfected since no eggs or worm of C. hepatica was present even after artificially digesting the whole liver. Presence of fibrosis in the uninfected liver suggests that the rat was ill. According to Young et al. (2009), fibrosis is characterized as an aggregate of fibrous tissue surrounding dead hepatocytes or pyknotic hepatocytes. Collagen is then remodeled to repair the stressed and infected area. Granuloma formation on the other hand is associated with infection, cell death, and immune mediated response (Thoolen et al. 2010). According to Thoolen et al. (2010), granuloma may be classified depending on the kind of infiltrating cells such as lymphocytes, monocytes, and plasma cells. The same manifestations were observed in the C. hepatica-infected liver (Fig. 6b). Exposure to the environment may have caused illness to the uninfected C. hepatica-rat resulting to fibrosis and formation of granuloma. On the other hand, the occurrence of fibrosis and presence of granuloma in the C. hepatica-infected liver may have been caused by the presence of the parasite itself since these manifestations are common response of a host to infection (Young et al. 2009). Furthermore, carcasses of C. hepatica eggs were present in surrounded by the fibrous tissue (Fig. 6b). This shows the response of the host to the infection.

Recommendations

This study recommends studies on transmission dynamics of Capillaria hepatica in Philippine rats for there are no available references. Procurement of fecal samples of rats and paratenic hosts, and soil samples are also suggested for the extent of environment contamination of C. hepatica. Finally, educational campaign should be done to increase public’s awareness on diseases transmitted by rats. Increased awareness in the community regarding zoonotic diseases is also important to further prevent people from exposure to parasite infections.

Acknowledgements

The authors wish to acknowledge MODECERA (Monitoring and Detection of Ecosystem Changers for Enhancing Resilience and Adaptation in the Philippines) for their assistance in collection of samples. Mr. Leonardo A. Estaño is also acknowledged for generating the map for this study.

Author contribution statement

MHQ and VGP did the research conceptualization and manuscript writing. MHQ also conducted the experiment, data analyses, and field data gathering.

Compliance with ethical standards

Conflict of interest

The authors declare that they have no conflict of interest.

Footnotes

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Contributor Information

Maria Henrietta D. P. Quilla, Email: mdquilla3@up.edu.ph

Vachel Gay V. Paller, Email: vvpaller@up.edu.ph

References

- Aghdam MK, Karimi A, Amanati A, Ghoroubi J, Khoddami M, Shamsian BS, Far SZ. Capillaria hepatica, A case report and review of the literatures. Arch Pediatr Infect Dis. 2015 doi: 10.5812/pedinfect.19398. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Aplin KP, Brown PR, Jacob J, Krebs CJ, Singleton GR. Field methods for rodent studies in Asia and the Indo-Pacific. Canberra: Australian Centre for International Agricultural Research; 2003. [Google Scholar]

- Baker DG, editor. Flynn’s parasites of laboratory animals. New York: Wiley; 2008. [Google Scholar]

- Brooks JE, Rowe FP, World Health Organization, Division of Vector Biology and Control (1987) Rodents: training and information guide. World Health Organization

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (2012) Parasite Capillariasis (also known as Capillaria infection). https://www.cdc.gov/parasites/capillaria/faqs.html. Accessed 11 July 2017

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (2016) Hepatic capillariasis. https://www.cdc.gov/dpdx/hepaticcapillariasis/index.html. Accessed 08 July 2017

- Ceruti R, Sonzogni O, Origgi F, Vezzoli F, Cammarata S, Giusti AM, Scanziani E. Capillaria hepatica infection in wild brown rats (Rattus norvegicus) from the urban area of Milan, Italy. Zoonoses Public Health. 2001;48(3):235–240. doi: 10.1046/j.1439-0450.2001.00436.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Childs JE, Glass GE, Korch GW., Jr The comparative epizootiology of Capillaria hepatica (Nematoda) in urban rodents from different habitats of Baltimore, Maryland. Can J Zool. 1988;66(12):2769–2775. doi: 10.1139/z88-404. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Da Rocha EJGD, Basano SDA, Souza MMD, Honda ER, Castro MBD, Colodel EM, Silva JCD, Barros LP, Rodrigues ES, Camargo LMA. Study of the prevalence of Capillaria hepatica in humans and rodents in an urban area of the city of Porto Velho, Rondônia, Brazil. Rev Inst Med Trop Sao Paulo. 2015;1:39–46. doi: 10.1590/s0036-46652015000100006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- De Souza MM, Tolentino M, Assis BC, Gonzalez ACDO, Silva TMC, Andrade ZA. Pathogenesis of septal fibrosis of the liver. (An experimental study with a new model) Pathol Res Pract. 2006;202(12):883–889. doi: 10.1016/j.prp.2006.07.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Easterbrook JD, Kaplan JB, Vanasco NB, Reeves WK, Purcell RH, Kosoy MY, Glass GE, Watson J, Klein SL. A survey of zoonotic pathogens carried by Norway rats in Baltimore, Maryland, USA. Epidemiol Infect. 2007;135:1192–1199. doi: 10.1017/S0950268806007746. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Farhang-Azad A. Ecology of Capillaria hepatica (Bancroft 1893)(Nematoda). II. Egg-releasing mechanisms and transmission. J Parasitol. 1977;63:701–706. doi: 10.2307/3279576. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fuehrer HP, Igel P, Auer H. Capillaria hepatica in man—an overview of hepatic capillariosis and spurious infections. Parasitol Res. 2011;109(4):969–979. doi: 10.1007/s00436-011-2494-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gutierrez Y. Diagnostic pathology of parasitic infections with clinical correlations. New York: Oxford University Press; 2000. [Google Scholar]

- Heaney LR, Balete DS, Dolar ML, Alcala AC, Dans ATL, Gonzales PC, Ingle NR, Lepiten MV, Oliver WLR, Ong PS, Rickart EA, Tabaranza BR, Utzurrum RCB. A synopsis of the mammalian fauna of the Philippine Islands. Fieldiana: Zool, n.s. 1998;88:1–61. [Google Scholar]

- Heaney LR, Balete DS, Rickart EA, Utzurrum RCB, Gonzales PC. Mammalian diversity on Mount Isarog, a threatened center of endemism on southern Luzon Island, Philippines. Fieldiana. Zool. 1999;95:1–62. [Google Scholar]

- Horiuchi S, Paller VG, Uga S. Soil contamination by parasite eggs in rural village in the Philippines. Trop Biomed. 2013;30(3):495–503. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kataranovski M, Zolotarevski L, Belij S, Mirkov I, Stošić J, Popov A, Kataranovski D. First record of Calodium hepaticum and Taenia taeniaeformis liver infection in wild Norway rats (Rattus norvegicus) in Serbia. Arch Biol Sci. 2010;62(2):431–440. doi: 10.2298/ABS1002431K. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Lapitan FRG, Magcale-Macandog DB, Raymundo MDS, Dela Cruz AG. Makiling biodiversity information system (MakiBIS): development of an online species information system for Mount Makiling. J Nat Stud. 2013;12(1):1–11. [Google Scholar]

- Layne JN. Host and ecological relationships of the parasitic helminth Capillaria hepatica in Florida mammals. Zoologica, NY. 1968;53(4):107–123. [Google Scholar]

- Li CD, Yang HL, Wang Y. Capillaria hepatica in China. World J Gastroenterol. 2010;16(6):698. doi: 10.3748/wjg.v16.i6.698. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Luttermoser GW. An experimental study of Capillariahepática in the rat and the mouse. Am J Hyg. 1938;27(2):321–340. [Google Scholar]

- Magcale-Macandog DB, Balon JL, Engay KG, Nicopior OBS, Luna DA, Dela Cruz CP. Assessment of the environmental degradation and proposed solutions in the Los Baños subwatershed through participatory approaches. J Nat Stud. 2011;10(2):1–15. [Google Scholar]

- Miliotis MD, Bier JW, editors. International handbook of foodborne pathogens. Boca Raton: CRC Press; 2003. [Google Scholar]

- Mowat V, Turton J, Stewart J, Lui KC, Pilling AM. Histopathological features of Capillaria hepatica infection in laboratory rabbits. Toxicol Pathol. 2009 doi: 10.1177/0192623309339501. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Oliveira L, Souza MMD, Andrade ZA. Capillaria hepatica-induced hepatic fibrosis in rats: paradoxical effect of repeated infections. Rev Soc Bras Med Trop. 2004;37(2):123–127. doi: 10.1590/S0037-86822004000200001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Resendes AR, Amaral AFS, Rodrigues A, Almeria S. Prevalence of Calodium hepaticum (Syn. Capillaria hepatica) in house mice (Mus musculus) in the Azores archipelago. Vet Parasitol. 2009;160(3):340–343. doi: 10.1016/j.vetpar.2008.11.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Salibay CC, Claveria FG. Serologic detection of Toxoplasma gondii infection in Rattus spp collected from three different sites in Dasmarinas, Cavite,Philippines. SE Asian J. Trop. Med. 2005;36:46. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Salibay C, Luyon HAV. Distribution of native and nonnative rats (Rattus spp.) along elevational gradient in a Tropical Rainforest of Southern Luzon, Philippines. Ecotropica. 2008;14(2):129–136. [Google Scholar]

- Shafiyyah CS, Jamaiah I, Rohela M, Lau YL, Aminah FS. Prevalence of intestinal and blood parasites among wild rats in Kuala Lumpur, Malaysia. Trop Biomed. 2012;29(4):544–550. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shin YM. Hepatic amyloidosis. Korean J Hepatol. 2011;17(1):80. doi: 10.3350/kjhep.2011.17.1.80. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Silbernagl S, Despopoulos A, Gay WR, Rothenburger A, Wandrey SON. Color atlas of physiology. Stuttgart: Thieme; 2009. [Google Scholar]

- Simões RO, Luque JL, Faro MJ, Motta E, Maldonado JR. Prevalence of Calodium hepaticum (syn. Capillaria hepatica) in Rattus norvegicus in the urban area of Rio de Janeiro, Brazil. Rev Inst Med Trop Sao Paulo. 2014;56(5):455–457. doi: 10.1590/s0036-46652014000500016. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Singla N, Singla LD, Gupta K, Sood NK. Pathological alterations in natural cases of Capillaria hepatica infection alone and in concurrence with Cysticercus fasciolaris in Bandicota bengalensis. J Parasit Dis. 2013;37(1):16–20. doi: 10.1007/s12639-012-0121-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Singleton G. Impacts of rodents on rice production in Asia. Los Baños: IRRI; 2003. [Google Scholar]

- Sinniah B, Singh M, Anuar K. Preliminary survey of Capillaria hepatica (Bancroft, 1893) in Malaysia. J Helminthol. 1979;53(2):147–152. doi: 10.1017/S0022149X00005897. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Spratt DM, Singleton GR. Parasitic diseases of wild mammals. 2. London: Manson Publishing; 2001. Hepatic capillariasis; pp. 365–379. [Google Scholar]

- Stojčević D, Mihaljević Ž, Marinculić A. Parasitological survey of rats in rural regions of Croatia. Vet Med (Czech) 2004;49(3):70–74. doi: 10.17221/5679-VETMED. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Sumangali K, Rajapakse RPVJ, Rajakaruna RS. Urban rodents as potential reservoirs of zoonoses: a parasitic survey in two selected areas in Kandy district. Ceylon J Sci Biol Sci. 2012;41(1):71–77. doi: 10.4038/cjsbs.v41i1.4539. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Thoolen B, Maronpot RR, Harada T, Nyska A, Rousseaux C, Nolte T, Malarkey DE, Kaufman W, Kuttler K, Deschl U, Nakae D, Gregson R, Vinlove MP, Brix AE, Singh B, Belpoggi F, Ward JM. Proliferative and nonproliferative lesions of the rat and mouse hepatobiliary system. Toxicol Pathol. 2010;38(7_suppl):5S–81S. doi: 10.1177/0192623310386499. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Traweger D, Travnitzky R, Moser C, Walzer C, Bernatzky G. Habitat preferences and distribution of the brown rat (Rattus norvegicus Berk.) in the city of Salzburg (Austria): implications for an urban rat management. J Pest Sci. 2006;79(3):113–125. doi: 10.1007/s10340-006-0123-z. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Wright KA. Observations on the life cycle of Capillaria hepatica (Bancroft, 1893) with a description of the adult. Can J Zool. 1961;39(2):167–182. doi: 10.1139/z61-022. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Young B, Stewart W, O’dowd G. Wheater’s basic pathology: a text. Atlas and review of histopathology. London: Churchill Livingstone; 2009. [Google Scholar]