Highlights

-

•

Narcissism and Facebook addiction (FA) are positively associated.

-

•

Facebook flow positively mediates the link between narcissism and FA.

-

•

Facebook use intensity positively moderates the link between Facebook flow and FA.

Keywords: Narcissism, Facebook use intensity, Facebook flow, Facebook addiction

Abstract

Introduction

The present study investigated mechanisms that may contribute to the enhanced risk of narcissistic individuals to develop Facebook addiction.

Methods

In a sample of 449 Facebook users (age: M(SD) = 31.07(9.52), range: 18–65) the personality trait narcissism, Facebook flow, intensity of Facebook use, and Facebook addiction were assessed by an online survey.

Results

In a moderated mediation analysis, the positive relationship between narcissism and Facebook addiction was positively mediated by the level of flow experienced on Facebook. Intensity of Facebook use moderated the positive association between Facebook flow and Facebook addiction.

Conclusions

Excessive Facebook use may cause psychological dependence. Narcissistic individuals are at enhanced risk for this form of dependence that is fostered by experience of flow during Facebook use and intensity of Facebook use. Current results should be taken into account, when assessing individuals at risk for pathological Facebook use and when planning specific interventions to deal with it.

1. Introduction

In the 21st century, use of social networking sites (SNSs) belongs to daily life of many people (Pew Research Center, 2018). With more than 2.4 billion members and more than 1.59 billion daily users, Facebook is currently the largest SNS (Roth, 2019). Many individuals often engage in intensive social interaction on Facebook by posting updates of their daily life and by commenting updates of other members. The online exchange contributes to feelings of connectedness, belonging, and social support (Bayer et al., 2018, Brailovskaia and Margraf, 2018, Ellison and Vitak, 2015). Moreover, positive comments and “Likes” set by Facebook friends to the uploaded postings enhance feelings of own popularity (Nadkarni & Hofmann, 2012) – an important reason why particularly individuals with high levels of the personality trait narcissism often tend to intensive Facebook use (Brailovskaia and Bierhoff, 2016, Brailovskaia and Bierhoff, 2018, Buffardi and Campbell, 2008, Gentile et al., 2012). Narcissistic individuals are characterized by an inflated self-view, sense of entitlement and of own grandiosity, as well as a high need for attention and admiration (Rogoza et al., 2018, Rohmann et al., 2012, Twenge et al., 2008). Facebook offers them various functions for self-presentation in superficial social interactions where they get positive feedback that satisfies their need for popularity (Brailovskaia and Margraf, 2019, Carpenter, 2012, Gnambs and Appel, 2018, Marshall et al., 2015, McCain and Campbell, 2018, Ong et al., 2011, Ryan and Xenos, 2011).

However, positive experiences gained on Facebook may foster the development of a strong emotional bond to the SNS (Casale and Fioravanti, 2018, Taylor and Strutton, 2016). This bond is linked to a problematic need to stay permanently online, to continuously upload own updates, and to check the activities of other users, even when this behavior disturbs the observance of obligations at home and at work, contributes to interpersonal difficulties, and impairs social relationships (Andreassen et al., 2017, Kimpton et al., 2016). This phenomenon was termed Facebook addiction (Andreassen, Torsheim, Brunborg, & Pallesen, 2012). Based on the core components of addictive (online) behavior (Griffiths, 2005), Facebook addiction was defined by six typical characteristics (Andreassen et al., 2012): salience (i.e., permanent thinking about Facebook), tolerance (i.e., heightened amounts of Facebook activity are required to attain previous positive effect), mood modification (i.e., mood improvement by Facebook use), relapse (i.e., reverting to higher amounts of Facebook activity after unsuccessful attempts of Facebook use reduction), withdrawal symptoms (i.e., becoming nervous without Facebook use), and conflict (i.e., interpersonal problems caused by intensive Facebook use). Note that Facebook addiction is not recognized as a formal psychiatric disorder (Brailovskaia & Margraf, 2017).

Earlier research demonstrated Facebook addiction to be positively associated with poor sleep quality, depression and anxiety symptoms (Andreassen et al., 2012, Atroszko et al., 2018, Błachnio et al., 2015, Brailovskaia and Margraf, 2017, Brailovskaia et al., 2019, Koc and Gulyagci, 2013, Marino et al., 2018a, Marino et al., 2018b, Ryan et al., 2014, Xie and Karan, 2019). Experience of daily stressors at home and at work positively predicted the level of Facebook addiction (Brailovskaia et al., 2018, Marino et al., 2018a). Moreover, a recent longitudinal study found Facebook addiction to positively predict the level of depression symptoms and of insomnia up to six weeks later (Brailovskaia, Rohmann, Bierhoff, Margraf, & Köllner, 2019). In addition, life satisfaction and resilience were negatively linked to Facebook addiction (Błachnio et al., 2016, Brailovskaia et al., 2018).

Narcissistic individuals were described to be at enhanced risk for the development of Facebook addiction. High intensity of Facebook use was reported to be one of the main causes of this finding (Brailovskaia et al., 2019, Brailovskaia et al., 2018, Koc and Gulyagci, 2013). However, considering that narcissists typically exactly plan and control their social activities (Emmons, 1987), the question arises which further hidden mechanisms may explain why those individuals tend to lose control over their behavior, to experience withdrawal when Facebook usage is not possible, and to neglect their offline social interactions. Thorough identification of such mechanisms might contribute to the protection of narcissistic individuals from the formation of Facebook addiction. This seems to be of great importance for the overall protection of their well-being with regard to the previously reported negative side effects of Facebook addiction (see for example Marino et al., 2018a, Marino et al., 2018b), specifically its contribution to insomnia, depression and anxiety symptoms (Brailovskaia, Rohmann, et al., 2019). Therefore, the main aim of the present study was to understand the factors and mechanisms that link the personality trait narcissism with Facebook addiction.

Considering previous research on online media use – particularly online video gaming –, experience of flow might be such a factor. Video gaming behavior was described to be related to a state of intensive intrinsic enjoyment, also designated as flow experience (Hull et al., 2013, Sweetser et al., 2012). Following the definition of Csikszentmihalyi (1990; p. 4), a flow experience is “the state in which people are so involved in an activity that nothing else seems to matter; the experience is so enjoyable that people will continue to do it even at great cost, for the sheer sake of doing it.” Thus, people engaging in intensive video gaming have an autotelic experience, i.e., they experience intrinsic reward (Csikszentmihalyi, 1975), that generates considerable pleasure and increases the probability that they will repeat this behavior (Rau, Peng, & Yang, 2006).

Based on the positive association of flow experience with gaming behavior, research has set out to investigate the relevance of flow in other forms of media use (Khang, Kim, & Kim, 2013). For instance, flow was found to be positively related to general Internet use (Hoffman & Novak, 2009), as well as online shopping (Bridges and Florsheim, 2008, Jiang and Benbasat, 2004). Several studies focused on use of SNSs (e.g., Chang & Zhu, 2012). Kaur, Dhir, Chen, and Rajala (2016) found empirically a positive association between Facebook use and flow experience. Flow experienced during Facebook use was defined by five core characteristics (Brailovskaia, Rohmann, Bierhoff, & Margraf, 2018): curiosity (i.e., experience of curiosity and interest during Facebook use), enjoyment (i.e., experience of enjoyment and fun during Facebook use), time-distortion (i.e., losing sense of time during Facebook use), focused attention (i.e., intensive focus on the activities conducted on Facebook), and telepresence (i.e., deep immersion into the Facebook world and simultaneously forgetting of the requirements of the offline world). Facebook flow was positively related to self-disclosure on Facebook and had a positive impact on post hoc interpersonal relationships (e.g., becoming closer) (Kwak, Choi, & Lee, 2014).

At a relatively early stage of the investigation of reasons for excessive gaming behavior, similarities between gaming flow and addictive symptoms such as for example experience of enjoyment and distorted sense of time have attracted research attention (Chou & Ting, 2003). Moreover, several investigations reported flow to be a positive predictor of gaming addiction. Individuals who had high levels of gaming flow exhibited an enhanced risk to develop gaming addiction (Hull et al., 2013, Khang et al., 2013, Trivedi and Teichert, 2017, Wu et al., 2013). Similar results were obtained by Brailovskaia, Rohmann, et al. (2018) who focused on Facebook use. They found flow experienced during Facebook activity to positively predict the level of Facebook addiction. The association between one of the core components of Facebook flow namely “telepresence” – that previously was identified as one of the main factors that create flow in the online environment (Hoffman and Novak, 2009, Kwak et al., 2014) – and Facebook addiction was conspicuously strong. On the basis of these findings the authors hypothesized that individuals who tend to deeply immerse into the online world during Facebook use exhibit a specific risk to develop Facebook addiction. Furthermore, in the same study, intensity of Facebook use moderated the link between Facebook flow and Facebook addiction (Brailovskaia, Rohmann, et al., 2018).

Considering this empirical background, the question arises whether it is possible to combine findings considering the relationship between narcissism and Facebook addiction, on the one hand, and Facebook flow and Facebook addiction, on the other hand, to explain the enhanced risk of narcissistic individuals to develop Facebook addiction. Might it be that the link between narcissism and Facebook addiction is mediated by Facebook flow? Positive self-presentation in front of large audiences belongs to the main characteristics of narcissistic persons. With the introduction of SNSs narcissists received for the first time the possibility to reach quickly a large audience regardless of location and time. Investigations that analyzed Facebook activity reported that pages of individuals with enhanced levels of narcissism systematically differ from pages of people with lower narcissism levels. More specifically, narcissists engage in intensive online self-presentation by uploading many attractive pictures, writing many updates, sending many private messages, and joining many discussion groups where they frequently write comments (Brailovskaia and Bierhoff, 2016, Brailovskaia and Bierhoff, 2018, Mehdizadeh, 2010). They typically spend much time on Facebook self-presentation and intensively focus on their online activities. This behavior pattern makes it possible for them to reach a high level of happiness and enjoyment (Brailovskaia & Margraf, 2019). Thus, the process of self-presentation might contribute to their experience of flow on Facebook, and Facebook flow might predict Facebook addiction. The strength of this link might be moderated by intensity of Facebook use – the higher the use intensity, the closer the link between Facebook flow and Facebook addiction (Brailovskaia et al., 2018, Wu et al., 2013).

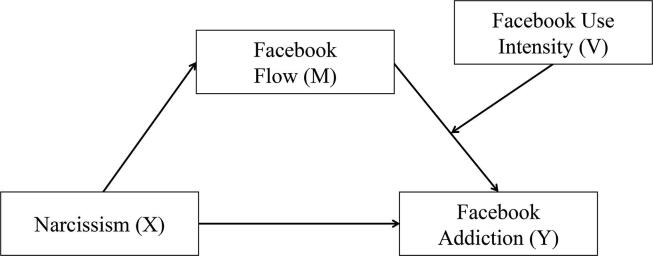

Based on the considerations presented and previous findings, the following hypotheses are formulated to investigate mechanisms that may enhance the risk of narcissistic individuals to develop Facebook addiction. We assume narcissism to be positively linked to Facebook addiction (Hypothesis 1a) and to Facebook flow (Hypothesis 1b); Facebook flow is expected to be positively related to Facebook addiction (Hypothesis 1c). Moreover, Facebook flow is expected to positively mediate the relationship between narcissism and Facebook addiction (Hypothesis 1d). Facebook use intensity is assumed to be positively linked to Facebook flow (Hypothesis 2a) and to Facebook addiction (Hypothesis 2b). Moreover, based on previous findings, Facebook use intensity is expected to moderate the association between Facebook flow and Facebook addiction (Hypothesis 2c). Fig. 1 visualizes the assumed relationships as a moderated mediation model (cf., Hayes, 2013; p. 450).

Fig. 1.

Relationship between narcissism (X), Facebook flow (M), Facebook use intensity (V) and Facebook addiction (Y) (moderated mediation model).

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Procedure and participants

Data of 449 Facebook users (72.2% women; age (years): M = 31.07, SD = 9.52, range: 18–65; occupation: 54.1% employees, 35.9% university students, 3.8% trainees for different professions like baker, 5.1% unemployed persons, 1.1% retirees), who were recruited by participation invitations displayed at public places, like bakeries, and online on various SNSs, have been collected from January to February 2018 via an online survey. The only requirement for participation, which was voluntary and could be compensated by course credits for students, was a current Facebook membership. Implementation of the present study was approved by the responsible Ethics Committee. Participants were properly instructed and provided online their informed consent to participate. No data were excluded. A priori conducted power analyses (G*Power program, version 3.1) revealed that the sample size was sufficient for valid results (power > 0.80, α = 0.05, effect size f2 = 0.15; cf., Mayr et al., 2007).

2.2. Measures

Narcissism. The personality trait narcissism was assessed with the brief German Narcissistic Personality Inventory (G-NPI-13) (Brailovskaia, Bierhoff, & Margraf, 2019). The G-NPI-13 consists of 13 forced-choice items (0 = low narcissism, e.g., “I am not particularly interested in looking at myself in the mirror”, 1 = high narcissism, e.g., “I like to look at myself in the mirror”). Its internal scale reliability was reported to be Cronbach’s α = 0.67/0.73 (Brailovskaia et al., 2019, Gentile et al., 2013). Current reliability: α = 0.67 (confidence interval: 95% CI [0.62, 0.71]).

Facebook use intensity. In correspondence with Wu et al., 2013, Brailovskaia et al., 2018, to assess intensity of Facebook use, we included four indicators: duration of Facebook membership (in months); frequency of daily Facebook use; duration of daily Facebook use (in minutes); emotional connection to Facebook and its integration into the daily life as assessed with the six items of the Facebook Intensity Scale (FIS) (Ellison, Steinfield, & Lampe, 2007), which are rated on a 5-point Likert scale (1 = disagree strongly, 5 = agree strongly; e.g., “Facebook is part of my everyday activity”; earlier reported internal scale reliability: α = 0.85, current reliability: α = 0.84, 95% CI [0.81, 0.86]). A composite index of these four indicators was attained by computing the mean of the z-transformed indicators. The internal reliability of the composite index of α = 0.61 (95% CI [0.55, 0.66]) is tenable given the small number of items.

Facebook flow. Following Brailovskaia, Rohmann, et al. (2018), flow experience related to Facebook use was assessed with the modified version of the “Facebook flow” questionnaire adopted from Kwak et al. (2014). This instrument includes eleven items divided into five subscales based on the core characteristics of Facebook flow (Brailovskaia, Rohmann, et al., 2018). The subscale curiosity (e.g., “Using the Facebook excites my curiosity”), the subscale enjoyment (e.g., “I enjoy using the Facebook”), the subscale time-distortion (e.g., “Time flies when I am using the Facebook”), and the subscale focused attention (e.g., “While using the Facebook, I am deeply engrossed”) comprise two items each. Further three items belong to the subscale telepresence (e.g., “Using the Facebook often makes me forget where I am”). Items are rated on a 5-point Likert scale (1 = disagree strongly, 5 = agree strongly). Internal reliability of the eleven items was previously reported to be α = 0.88 (Brailovskaia, Rohmann, et al., 2018). Current reliability: α = 0.86 (95% CI [0.84, 0.88]).

Facebook Addiction. To assess the level of Facebook addiction over a time frame of the last year, the brief version of the Bergen Facebook Addiction Scale (BFAS) (Andreassen et al., 2012) was used. The BFAS includes six items (e.g., “Felt an urge to use Facebook more and more?”) which are based on the six core addiction features of Facebook addiction (i.e., salience, tolerance, mood modification, relapse, withdrawal, conflict) and are rated on a 5-point Likert scale (1 = very rarely, 5 = very often). This brief version was found to have similarly good psychometric properties as the full-length 18-item version. Earlier studies reported the BFAS to have an internal reliability of α = 0.83-0.86 (Andreassen et al., 2013, Andreassen et al., 2012, Pontes et al., 2016). Current reliability: α = 0.87 (95% CI [0.85, 0.89]).

2.3. Statistical analyses

Statistical analyses were conducted with the Statistical Package for the Social Sciences (SPSS 24) and the macro Process version 2.16.1 (www.processmacro.org/index.html; Hayes, 2013).

In the first step, descriptive statistics of the investigated variables and zero-order bivariate correlations were computed. In the next step, an analysis that integrated the hypothesized mediation model and the hypothesized moderation model (that is a moderated moderation analysis including a conditional indirect effect, see Fig. 1) (Edwards & Lambert, 2007) was run to examine the multiple effects simultaneously (Borau, El Akremi, Elgaaied-Gambier, Hamdi-Kidar, & Ranchoux, 2015) using Process “Model 14”. The moderated mediation effect was assessed by the bootstrapping procedure (10.000 samples) that provides accelerated confidence intervals (CI 95%). The analyses included narcissism (predictor, X), Facebook flow (mediator, M), Facebook use intensity (moderator, V) and Facebook addiction (outcome, Y), controlling for the covariates age and gender. Path a denoted the relationship between narcissism and Facebook flow; path b denoted the relationship between Facebook flow and Facebook addiction; path c′ (the direct effect) denoted the relationship between narcissism and Facebook addiction after the inclusion of Facebook flow and Facebook use intensity in the model.

3. Results

3.1. Descriptive analyses and correlation analyses

On average, participants were members on Facebook for 89.22 months (SD = 28.49; range: 0–168); they visited the SNS on average 7.89 times (SD = 12.23; range: 0–100) a day, and spent there daily on average 80.45 min (SD = 83.15, range: 0–900). The mean FIS level was M = 15.56 (SD = 5.21, range: 6–30). As presented in Table 1, narcissism (range: 0–13) was significantly positively correlated with Facebook flow (range: 11–48) and Facebook addiction (range: 6–29). Facebook flow and Facebook addiction were also significantly positively correlated. The composite index representing Facebook use intensity (range: −1.65–5.16) was significantly positively correlated with Facebook flow, Facebook addiction, and narcissism.

Table 1.

Descriptive statistics and correlations of gender, age, narcissism, Facebook flow, Facebook use intensity and Facebook addiction.

| M (SD) | (2) | (3) | (4) | (5) | (6) | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| (1) Gender | 0.04 | 0.17** | −0.09 | −0.07 | 0.08 | |

| (2) Age | 31.07 (9.52) | −0.02 | 0.11* | 0.12* | −0.02 | |

| (3) Narcissism | 3.72 (2.54) | 0.12* | 0.10* | 0.22** | ||

| (4) FB Flow | 26.87 (7.45) | 0.50** | 0.62** | |||

| (5) FB Use Intensity | 0.00 (0.68) | 0.47** | ||||

| (6) FB Addiction | 9.34 (4.17) | – |

Notes. N = 449; FB = Facebook; M = mean, SD = standard deviation; the variable “FB Use Intensity” represents the composite index of the four indicators: duration of Facebook membership, frequency of daily Facebook use, duration of daily Facebook use, Facebook Intensity Scale.

p < .05.

p < .01.

3.2. Moderated mediation analysis (narcissism, Facebook flow, Facebook use intensity, and Facebook addiction)

Table 2 shows results of the moderated mediation analysis. The overall model was significant (F(6,442) = 46.769, p < .001). The explained variance of the overall model was substantial (R2 = 0.50). The direct effect (path c′) of narcissism on Facebook addiction was significant (p = .019) after controlling for Facebook flow, Facebook use intensity, and their interaction. The conditional indirect effect of narcissism on Facebook addiction through Facebook flow was significant in people with low, medium, and high levels of Facebook use intensity. However, as shown in Table 2, this effect was stronger for participants who expressed a high level of Facebook use intensity (one SD above mean = 0.678), than for participants that expressed a medium level of Facebook use intensity (mean = 0), or a low level of Facebook use intensity (one SD below mean = −0.678). As indicated by the index of moderated mediation, the test of moderated mediation was also significant indicating a significant moderated mediation effect.

Table 2.

Moderated mediation model.

| ß | SE | t | p | 95% CI | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Path a: Narcissism → FB Flow | 0.410 | 0.160 | 2.562 | 0.012 | [0.100, 0.725] |

| Path b: FB Flow → FB Addiction | 0.274 | 0.028 | 9.724 | 0.001 | [0.218, 0.329] |

| Interaction: FB Flow*FB Use Intensity → FB Addiction | 0.149 | 0.033 | 4.584 | 0.001 | [0.085, 0.213] |

| Path c′ (direct effect): Narcissism → FB Addiction | 0.151 | 0.064 | 2.365 | 0.019 | [0.025, 0.276] |

| Conditional Indirect Effects: Narcissism → FB Addiction | |||||

| Narcissism → FB Flow → FB Addiction | |||||

| FB Use Intensity: | |||||

| Low (one SD below mean = −0.678) | 0.071 | 0.031 | [0.017, 0.138] | ||

| Medium (mean = 0) | 0.112 | 0.046 | [0.028, 0.207] | ||

| High (one SD above mean = 0.678) | 0.154 | 0.063 | [0.039, 0.282] | ||

| Index of Moderated Mediation | 0.061 | 0.028 | [0.014, 0.121] | ||

Notes. N = 449; covariates: age and gender, ß=standardized beta, SE = standard error, t = t-test, p = significance, CI = confidence interval; FB = Facebook.

4. Discussion

The present study investigated the relationship between the personality trait narcissism, Facebook flow, intensity of Facebook use, and Facebook addiction in a German sample. The statistical model employed – that is the moderated mediation model – represents a promising approach to examine the hypotheses. The significant results confirm our hypotheses and contribute to a better understanding why narcissistic individuals are at enhanced risk to develop Facebook addiction.

In line with previous findings (Brailovskaia et al., 2018, Casale and Fioravanti, 2018), the personality trait narcissism was positively related to Facebook addiction (confirming Hypothesis 1a). Furthermore, as expected we found a positive link between narcissism and Facebook flow (confirming Hypothesis 1b), as well as between Facebook flow and Facebook addiction (confirming Hypothesis 1c). Facebook flow served as a mediator between narcissism and Facebook addiction (confirming Hypothesis 1d). Additionally, our results revealed a positive association of intensity of Facebook use with Facebook flow (confirming Hypothesis 2a) and with Facebook addiction (confirming Hypothesis 2b). Moreover, Facebook use intensity moderated the link between flow and addiction (confirming Hypothesis 2c).

Current findings might point to one explanation why narcissistic members of Facebook are at risk to develop Facebook addiction. Narcissistic individuals have the talent to present themselves as charming interaction partners and to initiate many superficial social relationships (Campbell et al., 2002, Paulhus, 2001). In contrast to face-to-face interactions that typically allow only the presence of a limited audience and limited ways of self-presentation, on Facebook narcissists receive the possibility to realize their need for self-promotion in front of a large audience. They may close online friendship to as many Facebook users as they want to in a short period of time, may upload as many attractive photos that present different facets of their life as they want to, may write as many status updates as they want to and also as often as they want to, and may write comments in as many discussion groups as they want to in parallel (Brailovskaia & Bierhoff, 2016). As a consequence, they are likely to get online much more attention and admiration that enable them the experience of intensive enjoyment and satisfaction more than in the offline world. These feelings match closely the flow experience (cf., Csikszentmihalyi, 1975). The more admiration narcissistic users perceive to receive on Facebook, the deeper they immerse into the online world which fosters the experience of telepresence. Note that telepresence belongs to core characteristics of online flow and is particularly closely linked to addictive symptoms such as withdrawal when the Facebook world has to be temporarily left (Brailovskaia, Rohmann, et al., 2018). Correspondingly, an additional analysis of the subscales of flow in connection with Facebook addiction revealed that the highest correlation occurred between the scale telepresence and Facebook addiction (r = 0.671, p = .001). Thus, narcissistic users who experience high levels of flow during Facebook use, particularly telepresence, might be at specific risk to develop a psychological dependence to Facebook use. Therefore, flow might be one of the key factors that enhance the relationship between narcissism and Facebook addiction.

Note that in accordance with previous findings on gaming behavior and Facebook activity (Brailovskaia et al., 2018, Wu et al., 2013), Facebook use intensity – that is typically high in narcissistic individuals because of their pronounced desire to be admired by a large audience (Campbell et al., 2002, Paulhus and Williams, 2002) – seems to moderate the relationship between flow and addiction in narcissistic individuals: the higher the use intensity, the stronger Facebook flow may contribute to symptoms of Facebook addiction.

Present findings that contribute to the explanation of the link between narcissism and Facebook addiction are of significant importance, considering that Facebook addiction may negatively impact offline life by increasing interpersonal problems and well-being by contributing to insomnia, depression and anxiety symptoms (Atroszko et al., 2018, Brailovskaia et al., 2019, Kircaburun and Griffiths, 2018a, Marino et al., 2018b). They may be consulted when assessing individuals at risk for problematic Facebook use. In addition, they may inform the planning of specific interventions to deal with problematic Facebook use. Note that earlier research revealed the potential of physical/sportive activities such as jogging, cycling and swimming to reduce the risk of Facebook addiction (Brailovskaia, Teismann, et al., 2018) and to foster well-being (Wunsch, Kasten, & Fuchs, 2017). Narcissists might particularly benefit from this protective factor. Similar to Facebook use, sportive activities contribute to the experience of flow (Drane & Barber, 2016) that is linked to enjoyment and happiness (Csikszentmihalyi, 1975, Csikszentmihalyi, 1990). Therefore, it may be hypothesized that the replacement of online flow (that fosters Facebook addiction in narcissistic individuals) by sportive flow can support narcissistic individuals in reducing their emotional bond to the SNS. Narcissistic need for attention and admiration that drives intensive Facebook use (Davenport, Bergman, Bergman, & Fearrington, 2014), might be at least partly satisfied by positive feedback from their offline environment when achieving sportive goals. Moreover, the more time is spent on sportive activities, the less time remains for Facebook use. Overall this strategy might not only reduce the risk of Facebook addiction, but also protect the well-being of narcissistic individuals.

4.1. Limitations and further research

Even though the current study has the advantage to be based on a quite heterogeneous sample in terms of age distribution and occupation, the gender composition limits the generalizability of present results, because about 72% of respondents were female. We controlled for the variable gender in our statistical analyses to tackle this limitation. Nevertheless, future studies should replicate our results on a basis of a more balanced gender composition.

Given the cross-sectional nature of the present data, we must emphasize that only limited insights into causal relationships may be gained from our results. Nevertheless, by employing a moderated mediation analysis we were able to gain deeper understanding of the psychological processes involved with respect to the link between narcissism and Facebook addiction. In order to draw truly causal conclusions about the determinants of Facebook addiction, the current research design must be extended by studies, which establish a temporal sequence of cause and effect, or by experimental studies (Kraemer et al., 1997). Additionally, future studies investigating Facebook addiction might include physiological markers, such as heart rate, skin conductance, and blood pressure, which are related to problematic Internet use (Reed et al., 2017, Romano et al., 2017). Discovering physiological markers of Facebook addiction could substantially contribute to a better understanding of its development and maintenance.

Furthermore, considering the low reliability of measures used to assess narcissism and intensity of Facebook use, interpretations of current results should be handled with caution. We recommend the planning of future studies to replicate our findings with more reliable instruments. For example, the full-length 40-item NPI version (Raskin & Terry, 1988) could be used to measure the level of narcissism on a highly reliable level. To assess intensity of Facebook use, further indicators such as the frequency of specific activities (for example writing of status updates) might be included in the composite index to enhance its internal consistency.

Facebook is currently the largest social platform where most available research on addictive/problematic social media use was conducted on (e.g., Marino et al., 2018b). However, some previous studies reported addictive use tendencies on further SNSs such as Instagram (Kircaburun & Griffiths, 2018b) or Snapchat (Punyanunt-Carter, De La Cruz, & Wrench, 2017), and on general SNSs use (Andreassen et al., 2017, Casale et al., 2016). Moreover, the focus of the current study was on the grandiose form of narcissism. Previous research reported a positive relationship between the vulnerable form of narcissism and addictive use of SNSs (Casale et al., 2016). Therefore, future studies should investigate whether current findings may be replicated on other social platforms and are applicable to addictive social media use in general, or whether they are specific for Facebook addiction. Furthermore, it should be investigated whether present results are also applicable to vulnerable narcissism.

To sum up, our results indicate that Facebook addiction is systematically related to the personality trait narcissism, Facebook flow, and Facebook use intensity. Although Facebook use provides many benefits for the members of the SNS, like initiating new relationships and keeping in touch with old friends, gathering new information about a plethora of topics, and presenting oneself in a positive light, that may contribute to happiness and pleasure (Kim and Lee, 2011, Liu and Yu, 2013), an excessive Facebook use may cause psychological dependence. Particularly narcissistic individuals seem to be at risk for this dependence. Our findings indicate that Facebook flow as well as intensity of Facebook use represent key factors in the development of Facebook addiction. Longitudinal studies are necessary to further elucidate how these key factors cause this dependency.

Role of Funding Sources

This research did not receive any specific grant from funding agencies in the public, commercial, or not-for-profit sectors.

Contributors

Julia Brailovskaia designed the study, conducted literature searches, provided summaries of previous research studies, and collected and prepared data. Julia Brailovskaia, Hans-Werner Bierhoff, and Elke Rohmann conducted the statistical analysis. Julia Brailovskaia wrote the first draft of the manuscript. Hans-Werner Bierhoff, Elke Rohmann, Friederike Raeder and Jürgen Margraf reviewed and edited the draft. All authors contributed to and have approved the final manuscript.

Declaration of Competing Interest

The authors declare that they have no known competing financial interests or personal relationships that could have appeared to influence the work reported in this paper.

Acknowledgements

None.

Footnotes

Supplementary data to this article can be found online at https://doi.org/10.1016/j.abrep.2020.100265.

Contributor Information

Julia Brailovskaia, Email: Julia.Brailovskaia@rub.de.

Hans-Werner Bierhoff, Email: Hans.Bierhoff@rub.de.

Elke Rohmann, Email: Elke.Rohmann@rub.de.

Friederike Raeder, Email: Friederike.Preusser@rub.de.

Jürgen Margraf, Email: Juergen.Margraf@rub.de.

Appendix A. Supplementary material

The following are the Supplementary data to this article:

References

- Andreassen C.S., Griffiths M.D., Gjertsen S.R., Krossbakken E., Kvam S., Pallesen S. The relationships between behavioral addictions and the five-factor model of personality. Journal of Behavioral Addictions. 2013;2(2):90–99. doi: 10.1556/JBA.2.2013.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Andreassen C.S., Pallesen S., Griffiths M.D. The relationship between addictive use of social media, narcissism, and self-esteem: Findings from a large national survey. Addictive Behaviors. 2017;64:287–293. doi: 10.1016/j.addbeh.2016.03.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Andreassen C.S., Torsheim T., Brunborg G.S., Pallesen S. Development of a Facebook addiction scale. Psychological Reports. 2012;110(2):501–517. doi: 10.2466/02.09.18.PR0.110.2.501-517. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Atroszko P.A., Balcerowska J.M., Bereznowski P., Biernatowska A., Pallesen S., Andreassen C.S. Facebook addiction among Polish undergraduate students: Validity of measurement and relationship with personality and well-being. Computers in Human Behavior. 2018;85:329–338. doi: 10.1016/j.chb.2018.04.001. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Bayer J., Ellison N., Schoenebeck S., Brady E., Falk E.B. Facebook in context (s): Measuring emotional responses across time and space. New Media & Society. 2018;20(3):1047–1067. doi: 10.1177/1461444816681522. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Błachnio A., Przepiorka A., Pantic I. Association between Facebook addiction, self-esteem and life satisfaction: A cross-sectional study. Computers in Human Behavior. 2016;55:701–705. doi: 10.1016/j.chb.2015.10.026. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Błachnio A., Przepiórka A., Pantic I. Internet use, Facebook intrusion, and depression: Results of a cross-sectional study. European Psychiatry. 2015;30(6):681–684. doi: 10.1016/j.eurpsy.2015.04.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Borau S., El Akremi A., Elgaaied-Gambier L., Hamdi-Kidar L., Ranchoux C. Analysing moderated mediation effects: Marketing applications. Recherche et Applications en Marketing (English Edition) 2015;30(4):88–128. doi: 10.1177/2051570715606278. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Brailovskaia J., Bierhoff H.-W. Cross-cultural narcissism on Facebook: Relationship between self-presentation, social interaction and the open and covert narcissism on a social networking site in Germany and Russia. Computers in Human Behavior. 2016;55:251–257. doi: 10.1016/j.chb.2015.09.018. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Brailovskaia J., Bierhoff H.-W. The Narcissistic Millennial Generation: A Study of Personality Traits and Online Behavior on Facebook. Journal of Adult Development. 2018;1–13 doi: 10.1007/s10804-018-9321-1. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Brailovskaia J., Bierhoff H.-W., Margraf J. How to Identify Narcissism With 13 Items? Validation of the German Narcissistic Personality Inventory–13 (G-NPI-13) Assessment. 2019;26(4):630–644. doi: 10.1177/1073191117740625. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brailovskaia J., Margraf J. Facebook Addiction Disorder (FAD) among German students – a longitudinal approach. PLoS One. 2017;12(12):e0189719. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0189719. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brailovskaia J., Margraf J. What does media use reveal about personality and mental health? An exploratory investigation among German students. PLoS One. 2018;13(1):e0191810. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0191810. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brailovskaia J., Margraf J. I present myself and have a lot of Facebook-friends–Am I a happy narcissist!? Personality and Individual Differences. 2019;148:11–16. doi: 10.1016/j.paid.2019.05.022. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Brailovskaia J., Margraf J., Köllner V. Addicted to Facebook? Relationship between Facebook Addiction Disorder, duration of Facebook use and narcissism in an inpatient sample. Psychiatry Research. 2019;273:52–57. doi: 10.1016/j.psychres.2019.01.016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brailovskaia J., Rohmann E., Bierhoff H.-W., Margraf J. The brave blue world: Facebook Flow and Facebook Addiction Disorder (FAD) PLoS One. 2018;13(7):e0201484. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0201484. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brailovskaia J., Rohmann E., Bierhoff H.-W., Margraf J., Köllner V. Relationships between addictive Facebook use, depressiveness, insomnia, and positive mental health in an inpatient sample: A German longitudinal study. Journal of Behavioral Addictions. 2019;8(4):703–713. doi: 10.1556/2006.8.2019.63. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brailovskaia J., Schillack H., Margraf J. Facebook Addiction Disorder (FAD) in Germany. Cyberpsychology, Behavior, and Social Networking. 2018;21(7):450–456. doi: 10.1089/cyber.2018.0140. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brailovskaia J., Teismann T., Margraf J. Physical activity mediates the association between daily stress and Facebook Addiction Disorder (FAD) – a longitudinal approach among German students. Computers in Human Behavior. 2018;86:199–204. doi: 10.1016/j.chb.2018.04.045. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Brailovskaia J., Velten J., Margraf J. Relationship between daily stress, depression symptoms, and Facebook Addiction Disorder in Germany and in the USA. Cyberpsychology, Behavior, & Social Networking. 2019;22(9):610–614. doi: 10.1089/cyber.2019.0165. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bridges E., Florsheim R. Hedonic and utilitarian shopping goals: The online experience. Journal of Business Research. 2008;61(4):309–314. doi: 10.1016/j.jbusres.2007.06.017. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Buffardi L.E., Campbell W.K. Narcissism and social networking web sites. Personality and Social Psychology Bulletin. 2008;34(10):1303–1314. doi: 10.1177/0146167208320061. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Campbell W.K., Rudich E.A., Sedikides C. Narcissism, self-esteem, and the positivity of self-views: Two portraits of self-love. Personality and Social Psychology Bulletin. 2002;28(3):358–368. doi: 10.1177/0146167202286007. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Carpenter C.J. Narcissism on Facebook: Self-promotional and anti-social behavior. Personality and Individual Differences. 2012;52(4):482–486. doi: 10.1016/j.paid.2011.11.011. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Casale S., Fioravanti G. Why narcissists are at risk for developing Facebook addiction: The need to be admired and the need to belong. Addictive Behaviors. 2018;76:312–318. doi: 10.1016/j.addbeh.2017.08.038. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Casale S., Fioravanti G., Rugai L. Grandiose and vulnerable narcissists: Who is at higher risk for social networking addiction? Cyberpsychology, Behavior, and Social Networking. 2016;19(8):510–515. doi: 10.1089/cyber.2016.0189. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chang Y.P., Zhu D.H. The role of perceived social capital and flow experience in building users’ continuance intention to social networking sites in China. Computers in Human Behavior. 2012;28(3):995–1001. doi: 10.1016/j.chb.2012.01.001. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Chou T.-J., Ting C.-C. The role of flow experience in cyber-game addiction. CyberPsychology & Behavior. 2003;6(6):663–675. doi: 10.1089/109493103322725469. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Csikszentmihalyi M. Play and intrinsic rewards. Journal of Humanistic Psychology. 1975;15:41–63. [Google Scholar]

- Csikszentmihalyi M. Cambridge UniversityPress; New York, NY: 1990. Flow: The psychology of optimal performance. [Google Scholar]

- Davenport S.W., Bergman S.M., Bergman J.Z., Fearrington M.E. Twitter versus Facebook: Exploring the role of narcissism in the motives and usage of different social media platforms. Computers in Human Behavior. 2014;32:212–220. doi: 10.1016/j.chb.2013.12.011. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Drane C.F., Barber B.L. Who gets more out of sport? The role of value and perceived ability in flow and identity-related experiences in adolescent sport. Applied Developmental Science. 2016;20(4):267–277. doi: 10.1080/10888691.2015.1114889. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Edwards J.R., Lambert L.S. Methods for integrating moderation and mediation: A general analytical framework using moderated path analysis. Psychological Methods. 2007;12(1):1–22. doi: 10.1037/1082-989X.12.1.1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ellison N.B., Steinfield C., Lampe C. The benefits of Facebook “friends:” Social capital and college students’ use of online social network sites. Journal of Computer-Mediated Communication. 2007;12(4):1143–1168. doi: 10.1111/j.1083-6101.2007.00367.x. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Ellison N.B., Vitak J. Social network site affordances and their relationship to social capital processes. In: Sundar S., editor. The handbook of the psychology of communication technology. Wiley-Blackwell; Boston: 2015. pp. 205–227. [Google Scholar]

- Emmons R.A. Narcissism: Theory and measurement. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology. 1987;52(1):11–17. doi: 10.1037/0022-3514.52.1.11. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gentile B., Miller J.D., Hoffman B.J., Reidy D.E., Zeichner A., Campbell W.K. A test of two brief measures of grandiose narcissism: The narcissistic personality inventory-13 and the narcissistic personality inventory-16. Psychological Assessment. 2013;25(4):1120–1136. doi: 10.1037/a0033192. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gentile B., Twenge J.M., Freeman E.C., Campbell W.K. The effect of social networking websites on positive self-views: An experimental investigation. Computers in Human Behavior. 2012;28(5):1929–1933. doi: 10.1016/j.chb.2012.05.012. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Gnambs T., Appel M. Narcissism and social networking behavior: a meta-analysis. Journal of Personality. 2018;86(2):200–212. doi: 10.1111/jopy.12305. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Griffiths M.D. A ‘components’ model of addiction within a biopsychosocial framework. Journal of Substance Use. 2005;10(4):191–197. doi: 10.1080/14659890500114359. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Hayes A. Guilford Press; London: 2013. Introduction to mediation, moderation, and conditional process analysis. [Google Scholar]

- Hoffman D.L., Novak T.P. Flow online: Lessons learned and future prospects. Journal of Interactive Marketing. 2009;23(1):23–34. doi: 10.1016/j.intmar.2008.10.003. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Hull D.C., Williams G.A., Griffiths M.D. Video game characteristics, happiness and flow as predictors of addiction among video game players: A pilot study. Journal of Behavioral Addictions. 2013;2(3):145–152. doi: 10.1556/JBA.2.2013.005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jiang Z., Benbasat I. Virtual product experience: Effects of visual and functional control of products on perceived diagnosticity and flow in electronic shopping. Journal of Management Information Systems. 2004;21(3):111–147. doi: 10.1080/07421222.2004.11045817. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Kaur P., Dhir A., Chen S., Rajala R. Flow in context: Development and validation of the flow experience instrument for social networking. Computers in Human Behavior. 2016;59:358–367. doi: 10.1016/j.chb.2016.02.039. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Khang H., Kim J.K., Kim Y. Self-traits and motivations as antecedents of digital media flow and addiction: The Internet, mobile phones, and video games. Computers in Human Behavior. 2013;29(6):2416–2424. doi: 10.1016/j.chb.2013.05.027. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Kim J., Lee J.E. The Facebook paths to happiness: Effects of the number of Facebook friends and self-presentation on subjective well-being. Cyberpsychology, Behavior, and Social Networking. 2011;14(6):359–364. doi: 10.1089/cyber.2010.0374. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kimpton M., Campbell M.A., Weigin E.L., Orel A., Wozencroft K., Whiteford C. The relation of gender, behavior, and intimacy development on level of Facebook addiction in emerging adults. Gender and Diversity: Concepts, Methodologies, Tools, and Applications. 2016;6(2):56–67. doi: 10.4018/IJCBPL.2016040104. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Kircaburun K., Griffiths M.D. The dark side of internet: Preliminary evidence for the associations of dark personality traits with specific online activities and problematic internet use. Journal of Behavioral Addictions. 2018;7(4):993–1003. doi: 10.1556/2006.7.2018.109. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kircaburun K., Griffiths M.D. Instagram addiction and the Big Five of personality: The mediating role of self-liking. Journal of Behavioral Addictions. 2018;7(1):158–170. doi: 10.1556/2006.7.2018.15. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Koc M., Gulyagci S. Facebook addiction among Turkish college students: The role of psychological health, demographic, and usage characteristics. Cyberpsychology, Behavior, and Social Networking. 2013;16(4):279–284. doi: 10.1089/cyber.2012.0249. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kraemer H.C., Kazdin A.E., Offord D.R., Kessler R.C., Jensen P.S., Kupfer D.J. Coming to terms with the terms of risk. Archives of General Psychiatry. 1997;54(4):337–343. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.1997.01830160065009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kwak K.T., Choi S.K., Lee B.G. SNS flow, SNS self-disclosure and post hoc interpersonal relations change: Focused on Korean Facebook user. Computers in Human Behavior. 2014;31:294–304. doi: 10.1016/j.chb.2013.10.046. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Liu C.-Y., Yu C.-P. Can Facebook use induce well-being? Cyberpsychology, Behavior, and Social Networking. 2013;16(9):674–678. doi: 10.1089/cyber.2012.0301. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Marino C., Gini G., Vieno A., Spada M.M. The associations between problematic Facebook use, psychological distress and well-being among adolescents and young adults: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Journal of Affective Disorders. 2018;226:274–281. doi: 10.1016/j.jad.2017.10.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Marino C., Gini G., Vieno A., Spada M.M. A comprehensive meta-analysis on Problematic Facebook Use. Computers in Human Behavior. 2018;83:262–277. doi: 10.1016/j.chb.2018.02.009. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Marshall T.C., Lefringhausen K., Ferenczi N. The Big Five, self-esteem, and narcissism as predictors of the topics people write about in Facebook status updates. Personality and Individual Differences. 2015;85:35–40. doi: 10.1016/j.paid.2015.04.039. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Mayr S., Erdfelder E., Buchner A., Faul F. A short tutorial of GPower. Tutorials in Quantitative Methods for Psychology. 2007;3(2):51–59. doi: 10.20982/tqmp.03.2.p051. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- McCain J.L., Campbell W.K. Narcissism and social media use: a meta-analytic review. Psychology of Popular Media Culture. 2018;7(3):308–327. doi: 10.1037/ppm0000137. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Mehdizadeh S. Self-presentation 2.0: narcissism and self-esteem on Facebook. Cyberpsychology, Behavior, and Social Networking. 2010;13(4):357–364. doi: 10.1089/cyber.2009.0257. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nadkarni A., Hofmann S.G. Why do people use Facebook? Personality and Individual Differences. 2012;52(3):243–249. doi: 10.1016/j.paid.2011.11.007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ong E.Y., Ang R.P., Ho J.C., Lim J.C., Goh D.H., Lee C.S., Chua A.Y. Narcissism, extraversion and adolescents’ self-presentation on Facebook. Personality and Individual Differences. 2011;50(2):180–185. doi: 10.1016/j.paid.2010.09.022. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Paulhus D.L. Normal narcissism: Two minimalist accounts. Psychological Inquiry. 2001;12(4):228–230. [Google Scholar]

- Paulhus D.L., Williams K.M. The dark triad of personality: Narcissism, Machiavellianism, and psychopathy. Journal of Research in Personality. 2002;36(6):556–563. [Google Scholar]

- Pew Research Center. (2018, 05. February 2018). Social Media Fact Sheet. Retrieved from http://www.pewinternet.org/fact-sheet/social-media/.

- Pontes H.M., Andreassen C.S., Griffiths M.D. Portuguese validation of the Bergen Facebook Addiction Scale: An empirical study. International Journal of Mental Health and Addiction. 2016;14(6):1062–1073. doi: 10.1007/s11469-016-9694-y. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Punyanunt-Carter N.M., De La Cruz J.J., Wrench J.S. Investigating the relationships among college students' satisfaction, addiction, needs, communication apprehension, motives, and uses & gratifications with Snapchat. Computers in Human Behavior. 2017;75:870–875. doi: 10.1016/j.chb.2017.06.034. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Raskin R., Terry H. A principal-components analysis of the Narcissistic Personality Inventory and further evidence of its construct validity. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology. 1988;54(5):890–902. doi: 10.1037//0022-3514.54.5.890. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rau P.-L.P., Peng S.-Y., Yang C.-C. Time distortion for expert and novice online game players. CyberPsychology & Behavior. 2006;9(4):396–403. doi: 10.1089/cpb.2006.9.396. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Reed P., Romano M., Re F., Roaro A., Osborne L.A., Viganò C., Truzoli R. Differential physiological changes following internet exposure in higher and lower problematic internet users. PLoS One. 2017;12(5):e0178480. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0178480. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rogoza R., Żemojtel-Piotrowska M., Kwiatkowska M.M., Kwiatkowska K. The bright, the dark, and the blue face of narcissism: The Spectrum of Narcissism in its relations to the metatraits of personality, self-esteem, and the nomological network of shyness, loneliness, and empathy. Frontiers in Psychology. 2018;9:343. doi: 10.3389/fpsyg.2018.00343. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rohmann E., Neumann E., Herner M.J., Bierhoff H.-W. Grandiose and vulnerable narcissism. European Psychologist. 2012;17:279–290. doi: 10.1027/1016-9040/a000100. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Romano M., Roaro A., Re F., Osborne L.A., Truzoli R., Reed P. Problematic internet users' skin conductance and anxiety increase after exposure to the internet. Addictive Behaviors. 2017;75:70–74. doi: 10.1016/j.addbeh.2017.07.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Roth, P. (2019, 26 Juli 2019). Nutzerzahlen: Facebook, Instagram, Messenger und WhatsApp, Highlights, Umsätze, uvm. (Stand Juli 2019). allfaceook.de. Retrieved from https://allfacebook.de/toll/state-of-facebook.

- Ryan T., Chester A., Reece J., Xenos S. The uses and abuses of Facebook: A review of Facebook addiction. Journal of Behavioral Addictions. 2014;3(3):133–148. doi: 10.1556/JBA.3.2014.016. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ryan T., Xenos S. Who uses Facebook? An investigation into the relationship between the Big Five, shyness, narcissism, loneliness, and Facebook usage. Computers in Human Behavior. 2011;27(5):1658–1664. doi: 10.1016/j.chb.2011.02.004. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Sweetser P., Johnson D.M., Wyeth P. Revisiting the GameFlow model with detailed heuristics. Journal: Creative Technologies. 2012;2012(3):1–16. [Google Scholar]

- Taylor D.G., Strutton D. Does Facebook usage lead to conspicuous consumption? The role of envy, narcissism and self-promotion. Journal of Research in Interactive Marketing. 2016;10(3):231–248. doi: 10.1108/JRIM-01-2015-0009. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Trivedi R.H., Teichert T. The Janus-Faced Role of Gambling Flow in Addiction Issues. Cyberpsychology, Behavior, and Social Networking. 2017;20(3):180–186. doi: 10.1089/cyber.2016.0453. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Twenge J.M., Konrath S., Foster J.D., Campbell W.K., Bushman B.J. Egos inflating over time: A cross-temporal meta-analysis of the Narcissistic Personality Inventory. Journal of Personality. 2008;76(4):875–901. doi: 10.1111/j.1467-6494.2008.00509.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wu T.-C., Scott D., Yang C.-C. Advanced or addicted? Exploring the relationship of recreation specialization to flow experiences and online game addiction. Leisure Sciences. 2013;35(3):203–217. doi: 10.1080/01490400.2013.780497. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Wunsch K., Kasten N., Fuchs R. The effect of physical activity on sleep quality, well-being, and affect in academic stress periods. Nature and Science of Sleep. 2017;9:117–126. doi: 10.2147/NSS.S132078. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Xie W., Karan K. Predicting Facebook addiction and state anxiety without Facebook by gender, trait anxiety, Facebook intensity, and different Facebook activities. Journal of Behavioral Addictions. 2019;8(1):79–87. doi: 10.1556/2006.8.2019.09. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.