Highlights

-

•

Social norms influence problematic social media use.

-

•

Difficulties in emotion regulation are associated with problematic social media use.

-

•

Facilitating use of e-motions predicts problematic social media use.

-

•

Peer influence and emotion regulation are relevant in this context.

Keywords: Problematic social media use, Social norms, Emotion regulation, Peer influence

Abstract

Introduction

Being constantly connected on social media is a “way of being” among adolescents. However, social media use can become “problematic” for some users and only a few studies have explored the concurrent contribution of social context and emotion regulation to problematic social media use. The current study aimed to test: (i) the influence of friends (i.e., their social media use and group norms about social media use); and (ii) the effects of difficulties in emotion regulation and so-called “e-motions” on adolescents’ problematic social media use.

Methods

A cross-sectional study was conducted in Italian secondary schools. An online questionnaire was administered to 761 adolescents (44.5% females; Mage = 15.49 years; SDage = 1.03).

Results

Path analysis showed that social norms were directly associated with problematic social media use and friends’ social media use was associated with the frequency of social media use, which, in turn, was associated with problematic use. Difficulties in emotion regulation were directly and indirectly linked to problematic social media use via frequency of use and facilitating use of e-motions.

Conclusions

These findings provide support for the importance of both peer influence and emotion regulation in this context. Social norms and emotion regulation should be considered in prevention programs addressing problematic social media use in adolescents.

1. Introduction

‘Social media’ is an umbrella term comprising social networking sites and messenger platforms representing the most used applications by adolescents along with online videogames (Wartberg, Kriston, & Thomasius, 2020). Nowadays, using social media and being “always online” is normative for teenagers born in a technological world in which interacting with others online is considered the status quo (Griffiths & Kuss, 2017). Not missing out, staying up to date and being constantly connected are some of the reasons why engagement in social media is a “way of being” rather than a mere activity (Griffiths & Kuss, 2017, p. 49). From this viewpoint, it not surprising that spending a lot of time online is a habitual behavior which can lead to negative consequences (Bányai et al., 2017, Griffiths and Kuss, 2017).

Despite the current lack of a clinical classification (e.g., Hawk, van den Eijnden, van Lissa, & ter Bogt, 2019), Problematic Social Media Use (henceforth PSMU) has been linked to both “addiction-like” symptoms (i.e., compulsion, salience, tolerance, withdrawal) and Internet-specific features (e.g., preference for online social interaction and the constant connectivity) that have been found to lead to impairments in everyday life (e.g., Billieux et al., 2015, Marino et al., 2017, van den Eijnden et al., 2016). Social media use becomes “problematic” when it causes distress to users, including impaired social and emotional functioning, and lower subjective well-being (Marino, 2018). Numerous studies have found an association between PSMU and several psychosocial health outcomes, such as depressive symptoms and social isolation (e.g., Marino et al., 2018a, Shensa et al., 2017). Furthermore, users with certain characteristics are more likely to engage in PSMU: for example, adolescents showing strong coping and conformity motives to use social media (Marino, Mazzieri, Caselli, Vieno, & Spada, 2018b) or people with poor emotion regulation (i.e., with specific personality traits like low levels of emotional stability [e.g., Marino et al., 2016] and narcissism [e.g., Casale and Fioravanti, 2018, Hawk et al., 2019]).

Although, a myriad of possible antecedents of PSMU has been proposed (Marino, Gini, Vieno, & Spada, 2018c), few studies have explored the concurrent contribution of social context and emotion regulation to PSMU. Therefore, the current study aimed to test the influence of friends (i.e., their social media use and group norms about social media use) on adolescents’ problematic social media use. Moreover, we aimed at testing the effects of difficulties in emotion regulation and so-called “e-motions” on adolescents’ PSMU.

1.1. Problematic social media use and social norms

Lack of research about the role of the social context (in this study conceptualized in terms of friendship relationships) in influencing adolescents’ online behavior is surprising, since developmental research has repeatedly confirmed the strong effect of peer influence, through different mechanisms that include adherence to peer group norms, homophily, social identity concerns, and others (Prinstein & Dodge, 2008). Friendship groups, like other social groups, are characterized by social norms and standards of behaviour that may, implicitly or explicitly, confer varying levels of approval toward a behaviour. However, we still know little about whether group norms can affect adolescents’ (mis)use of social media.

It has been recently proposed that increased adoption of social media among adolescents may shape peer relationships and youth behaviour in a developmental period when processes of peer influence and socialization of attitudes and behaviour among peers are particularly strong (Nesi et al., 2018a, Nesi et al., 2018b). On the one hand, adolescents’ online behaviour and social interactions reflect their offline experiences and, therefore, we should expect to see continuity between offline and online contexts (Mikami & Szwedo, 2011); moreover, it has been suggested that developmental issues and challenges are mostly the same in the offline and online contexts (Subrahmanyam & Smahel, 2011). On the other hand, key characteristics of the online context, and social media in particular (e.g., asynchronicity, permanence, publicness, cue absence, availability, etc.), may also be important in shaping youth’s beliefs, emotions, and behaviour (Nesi, Choukas-Bradley, & Prinstein, 2018a). Among these features of social media, availability, in particular, refers to the fact that social media content can be easily accessed and shared, and that users can easily start a contact or join a network, regardless of physical location or time of the day. One potential effect of the constant availability of social media is amplified expectations and demands within friendships, such as increased expectations of constant accessibility. For example, young adults have reported feeling intense pressure to be accessible to friends, at all times (Fox & Moreland, 2015), and that social media requires an intensive investment in their availability and communication with friends (Niland Lyons, Goodwin, & Hutton, 2015). Similar or even stronger pressure to be always available on social media might exist among adolescents. For example, one study found that adolescents expected to be disliked by friends if they did not reply immediately to e-mails (Katsumata, Matsumoto, Kitani, & Takeshima, 2008). Such pressure and related fear of negative consequences may represent a risk factor not only for adolescents’ frequent use of social media, but most importantly for their problematic use.

No studies, however, have tested whether adolescents’ PSMU could be influenced by friends’ use of social media and by group norms and expectations about that use. In the present work, friends’ use of social media was conceptualized in terms of adolescents’ perception of the frequency with which their friends use social media (paralleling their evaluation of their own use of social media). Consistent with between-friends similarity, we expected that higher (perceived) frequency of use by friends would be associated with higher frequency of use by participants that, in turn, would be associated with their PSMU. Group norms and expectations about social media use (henceforth “social norms”) were conceptualized as the extent to which the use of social media is valued, reinforced, and expected within the group of friends. We anticipated that these norms would be associated with adolescents’ PSMU both directly and indirectly via higher frequency of use by participants.

1.2. Problematic social media use and e-motions

Regarding individual characteristics associated with PSMU, one area, that still remains understudied, is the emotional domain. Gratz and Roemer (2004) defined emotion regulation in terms of evaluations of one’s own emotions (i.e., awareness, understanding and acceptance of emotions) and ability to control behaviors regardless of negative emotional state, and to use situationally appropriate emotion regulation strategies. It follows that difficulties in emotion regulation refer to the failed effort to modulate emotional arousal. Deficits in emotion regulation emerged as a risk factor in different problematic behaviours, including adults’ problematic Internet and Facebook use (Casale et al., 2016, Hormes et al., 2014, Yu et al., 2013). It has indeed been shown that using social media (like Facebook) as a means of mood regulation is one of the specific features characterizing problematic use and that difficulties in emotion regulation contribute to maintain problematic patterns of use via negative reinforcement (Marino et al., 2019). With respect to adolescents, youth low in emotional stability are more likely to engage in problematic Facebook use if they use the social network to regulate their mood, seek reassurance, and cope with negative affect (Marino et al., 2016, Marino et al., 2018b). Similarly, Spada and Marino (2017) have highlighted the use of the Internet as a strategy to control ‘unwanted’ emotional states (Casale et al., 2018, Spada et al., 2008).

However, an important gap in the literature is the lack of understanding of how users with difficulties in emotion regulation actually attempt to express and manage emotions on social media.

The multidimensional concept of “e-motions” has been recently proposed by Zych and colleagues (2017) referring to: (i) emotional expression and perception online, (ii) beliefs about the facilitating role of emotion-expression on social media in overcoming personal difficulties, and (iii) the understanding of online contacts’ emotions. The authors showed that e-motions are linked to some aspects of emotional intelligence and also to difficulties in identifying feelings (Zych, Ortega-Ruiz, & Marín-López, 2017). For the purpose of the current study, we focused on two specific dimensions of the E-motions Questionnaire (Zych et al., 2017), namely “e-motional expression” and “facilitating use of e-motions”, because these constructs reflect behaviors and beliefs related to online mood regulation that may be crucial in developing a problematic pattern of social media use. Specifically, it is plausible that “e-motional expression” (that is, using emoji to communicate own emotional state to others, and posting how one is feeling in different situations) might be responsible for the escalation of PSMU symptoms like preoccupation and compulsive use. Moreover, a strong belief that the expression of emotions on social media may improve relationships and help in thinking as well as making decisions (i.e., “facilitating use of e-motions”) might have a potential role in worsening salience and withdrawal/coping symptoms in PSMU.

Following this line of reasoning, we expected that adolescents experiencing difficulties in emotion regulation would be more likely to overcome such difficulties by engaging in e-motions expression/facilitation that, instead, would have a negative impact on the overall level of PSMU.

1.3. Aim of the current study

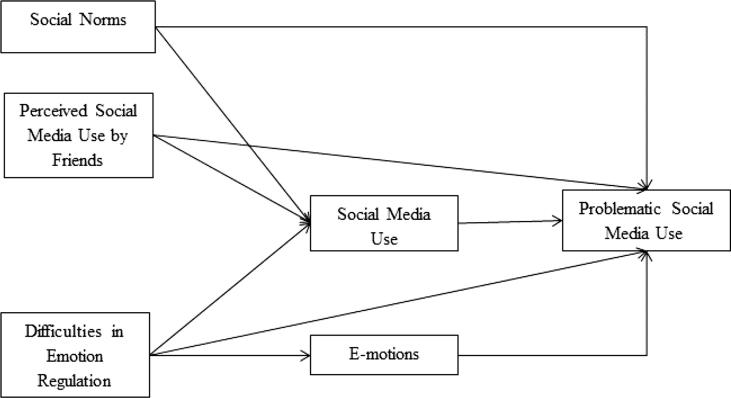

The conceptual model (Fig. 1), based on the above-mentioned theories and previous empirical work (Marino et al., 2016), was designed to test the following hypotheses. First, we hypothesized that adolescents’ PSMU would be influenced by the extent to which social media is used and valued in their immediate social context, that is, the peer group. Specifically, we hypothesized a positive direct effect of social norms on PSMU (H1a) and an indirect effect on PSMU via participants’ social media use (H1b). Similarly, we hypothesized a positive direct association between (perceived) social media use by friends and PSMU (H2a) and an indirect association with PSMU via participants’ own use of social media (H2b). Second, regarding individual characteristics, we hypothesized that emotion regulation would contribute to explain adolescents’ PSMU. Specifically, we expected that difficulties in emotion regulation would be linked to adolescents’ frequent use of social media and, thus, to PSMU (H3). Moreover, we hypothesized that difficulties in emotion regulation may be associated with more use of “e-motions” which, in turn, might worsen PSMU (H4). Age and gender are also included as control variables.

Fig. 1.

Hypothesized model.

2. Method

2.1. Participants and procedure

Participants were adolescents from Italian public secondary schools randomly selected in a Northern-East region of Italy who were asked to voluntarily participate in the study. Permission was first sought from the school principals and then signed active consent was obtained from parents (85% of the parents agreed) or from participants who were 18 or 19 years old. The final sample included 761 participants (44.5% females) with an average age of 15.49 years (SD = 1.03; age range = 13–19 years).

Participants completed anonymous self-report questionnaires during a regular school-day in school computer rooms and in the presence of the class teacher. Prior to data collection, participants were assured confidentiality and they were told that they could withdraw from the study at any time with no consequences. After completing the questionnaires, participants were thanked for their participation and researchers answered any questions raised. The research protocol was approved by the local Ethics Committee for Psychological Research.

Participants were first asked to list the social media they used. The most popular social media were Instagram (89.5%), WhatsApp (74.8%), and Facebook (50.2%). Other common social media were YouTube (32.3%) and Snapchat (28.4%). The majority of participants (69.4%) reported to use three or more social media.

2.2. Measures

Problem atic Social Media Use. PSMU was assessed through the Social Media Disorder Scale (van den Eijnden et al., 2016) validated for Italian adolescents by the authors of the original scale but not yet published. The scale includes 9 items, rated on a 5-point scale (from 1 “never” to 5 “very often”), which cover several criteria for PSMU described by van den Eijnden and colleagues (2016): preoccupation (e.g., “During the last year have you found that you can't think of anything else but the moment that you will be able to use social media again?”), preoccupation/salience (e.g., “Have you neglected homework because you are spending more time online?”), conflicts (e.g., “Have you been reprimanded by your parents or your friends about how much time you spend online?”), and withdrawal symptoms and coping (e.g., “Do you feel nervous when you are offline and is that feeling relieved when you do go back online?”). The Cronbach’s alpha for the scale in this sample was 0.76 (95% CI 0.74–0.78). A confirmatory factor analysis (CFA) was performed using DWLS estimator (Jöreskog & Sörbom, 1993) to test for the construct validity of the measure. The CFA confirmed an adequate fit between the model and the data: χ2(27) = 57.781, p < .001; CFI = 0.98; NNFI = 0.97; RMSEA = 0.039, 90% CI [0.025, 0.053]. All the standardized loadings were significant at the p < .001 level (mean loading = 0.52) thus showing item convergent validity (Anderson & Gerbing, 1988).

Social media use. Frequency of social media use was measured using a single item (1 “never” to 5 “very often”), with participants rating how often they are online on social media in a day (Marino et al., 2016, Siciliano et al., 2015).

Social norms. Social norms were measured with 4 items taken from a study on problematic Facebook use (Marino et al., 2016, Dholakia et al., 2004) and adapted to social media use (e.g., “My friends think that I should spend a lot of time on social media”, “My friends think that it is important that I use social media a lot”). Items are rated on a 5-point scale (1 “not at all” to 5 “very much”). The Cronbach’s alpha for the scale was 0.72 (95% CI 0.68–0.75).

Perceived social media use by friends. The perceived frequency of social media use by friends was measured using a single item (1 “never” to 5 “very often”), with participants rating how often they think their friends are online on social media in a day. This item paralleled the one used to assess participants’ frequency of social media use (Marino et al., 2016, Siciliano et al., 2015).

Difficulties in emotion regulation. The Italian version of the Difficulties in Emotion Regulation Strategies (DERS; Sighinolfi, Norcini Pala, Chiri, Marchetti, & Sica, 2010) was used. The 36 items are rated on a 5-point scale (from 1 “almost never” to 5 “almost always”) and cover six dimensions, labeled: lack of emotional awareness, lack of emotional clarity, difficulties controlling impulsive behaviors when distressed, difficulties engaging in goal-directed behavior when distressed, non-acceptance of negative emotional responses, and limited access to effective emotional regulation strategies. In the current study, answers on the 36 items were averaged to obtain an overall score for difficulties in emotion regulation (Sighinolfi et al., 2010). The Cronbach’s alpha for the scale was 0.90 (95% CI 0.89–0.91).

E-motions. We used the E-motions questionnaire (Zych et al., 2017) that comprises 21 items rated on a 5-point scale (from 1 “completely disagree” to 5 “completely agree”). Items were translated from English to Italian by two independent researchers and back-translated in English by one bilingual psychologist expert in the field. The scale covers four dimensions: e-motional expression (e.g., “I express my emotions on social media”); e-motional perception; facilitating use of e-motions (e.g., “Perceiving the emotions of my contacts on social media helps me to think”); understanding and management of e-motions. For the purpose of the current study only e-motional expression (4 items; Cronbach’s alpha = 0.62 (95% CI 0.57–0.66)) and facilitating use of e-motions (6 items; Cronbach’s alpha = 0.81 (95% CI 0.79–0.83)) were used.

2.3. Data analyses

First, correlations among all the study variables were computed. Then, a path analysis using Mplus 8.3 (Muthén & Muthén, 1998-2017) was conducted to test the hypothesized model (Fig. 1). The covariance matrix of the observed variable was analyzed with a Robust Maximum Likelihood method estimator and bias-corrected bootstrap confidence intervals with 5,000 bootstrapped iterations were used for calculating indirect effects, which were considered significant if their 95% confidence interval did not include zero. The “type = complex” feature in Mplus was used to account for dependency among observations (i.e., students nested within classes) through the Hubert-White sandwich estimator. In the tested model, PSMU was the dependent variable, social norms, friends’ use, and difficulties in emotion regulation were the independent variables, and participants’ social media use and the two e-emotions dimensions were the mediators. Age and gender were included as control variables as the latter has been found to be a controversial factor in PSMU (Marino et al., 2018a).

To evaluate the goodness of fit of the model we considered the R2 of each endogenous variable and the total coefficient of determination (TCD; Bollen, 1989, Jӧreskog and Sӧrbom, 1996).

3. Results

Descriptive statistics of the study variable are reported in Table 1. Correlations are reported in Table 2. As expected, PSMU was found to be positively associated with all other variables.

Table 1.

Descriptive statistics of the study variables.

| M (SD) | Skewness (SE) | Kurtosis (SE) | |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1. PSMU | 1.65 (0.53) | 1.17 (0.09) | 1.70 (0.18) |

| 2. Social Norms | 1.74 (0.66) | 0.95 (0.09) | 0.55 (0.18) |

| 3. SM Use | 4.09 (1.05) | −1.05 (0.09) | 1.01 (0.18) |

| 4. Friends Use | 4.63 (0.58) | −1.77 (0.09) | 4.90 (0.18) |

| 5. DER | 2.36 (0.57) | 0.70 (0.09) | 0.54 (0.18) |

| 6. E-motional Expression | 2.10 (0.70) | 0.69 (0.09) | 0.82 (0.18) |

| 7. Facilitating E-motions | 1.56 (0.65) | 1.62 (0.09) | 2.69 (0.18) |

| 8. Age | 15.49 (1.04) | 0.18 (0.09) | −0.25(18) |

Notes: N = 746; PSMU = Problematic Social Media Use; SM Use = Social Media Use; Friends Use = Perceived social media use by friends; DER = Difficulties in emotion regulation.

Table 2.

Correlations between the study variables.

| M (SD) | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 | 8 | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1. PSMU | 1.65 (0.53) | 1 | |||||||

| 2. Social Norms | 1.74 (0.66) | 0.38** | 1 | ||||||

| 3. SM Use | 4.09 (1.05) | 0.30** | 0.04 | 1 | |||||

| 4. Friends Use | 4.63 (0.58) | 0.10** | 0.08* | 0.32** | 1 | ||||

| 5. DER | 2.36 (0.57) | 0.46** | 0.23** | 0.23** | 0.11** | 1 | |||

| 6. E-motional Expression | 2.10 (0.70) | 0.34** | 0.19** | 0.39** | 0.13** | 0.32** | 1 | ||

| 7. Facilitating E-motions | 1.56 (0.65) | 0.38** | 0.30** | 0.18** | 0.05 | 0.35** | 0.49** | 1 | |

| 8. Age | 15.49 (1.04) | −0.08* | −0.10** | 0.07 | 0.05 | −0.03 | −0.03 | −0.04 | 1 |

| 9. Gender | – | −0.11** | 0.03 | −0.23** | −0.03 | −0.18** | −0.15** | 0.04 | −0.01 |

Notes: N = 746; **p < .001; *p < .01; PSMU = Problematic Social Media Use; SM Use = Social Media Use; Friends Use = Perceived social media use by friends; DER = Difficulties in emotion regulation; gender: females = 0, males = 1.

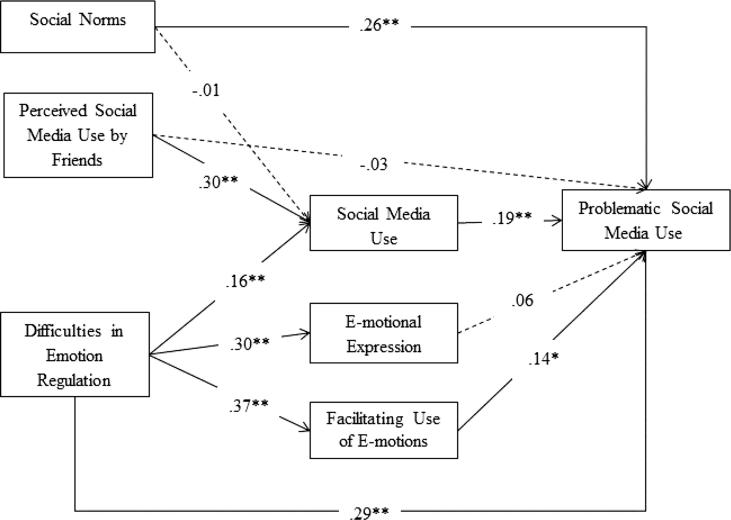

Findings from the path analysis are shown in Fig. 2. Regarding the direct effects, social norms were positively associated to PSMU but not to social media use that was instead positively associated with the outcome. Conversely, friends’ use was positively associated to social media use, but not directly associated to PSMU. With regard to emotional variables, difficulties in emotion regulation were significantly associated to PSMU and to the three mediators. E-motional expression was the only mediator non-significantly associated to PSMU.

Fig. 2.

Model of the inter-relationships between the study variables. Notes: N = 746; **p < .001; *p < .01. For sake of clarity, the effects of control variables (age and gender) are not reported, but are available upon request to the first author.

The model explained 34% of the variance of PSMU. Explained variance for the mediators was 18% for social media use, 11% for e-motional expression, and 14% for facilitating use of e-motions. The model had a good fit to the observed data, as indicated by the total amount of explained variance of TCD = 0.49, a value that corresponds to a correlation of r = 0.70, that is, a large effect size (Cohen, 1988).

Along with the direct paths, three indirect effects were found significant (Table 3). The strongest indirect associations were found between friends’ use and PSMU via social media use and between difficulties in emotion regulation and PSMU via facilitating use of e-motions. The indirect association between difficulties in emotion regulation and PSMU via social media use was smaller but still significant.

Table 3.

Standardized indirect effects of social norms and difficulties in emotion regulation on problematic social media use via social media use and e-motions.

| Independent variable | Mediator | PSMU |

||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| ES | 95% CI | |||

| Social Norms | SM Use | −0.002 | −0.022 | 0.014 |

| Friends Use | SM Use | 0.051 | 0.035 | 0.068 |

| DER | SM Use | 0.029 | 0.018 | 0.043 |

| E-motional Expression | 0.016 | −0.005 | 0.042 | |

| Facilitating E-motions | 0.049 | 0.013 | 0.094 | |

Note. ES = estimate; 95% CI = bias-corrected bootstrapped confidence interval; PSMU = Problematic Social Media Use; SM Use = Social Media Use; Friends Use = Perceived social media use by friends; DER = Difficulties in emotion regulation.

4. Discussion

Overall, the study confirmed that both features of the social context and emotion regulation contribute to explain frequency of social media use and PSMU among adolescents. First, results of the path analysis showed that the social context, defined by friendship relationships, plays a significant role in explaining adolescents’ PSMU. This finding adds to the current literature about this phenomenon that has largely focused on individual risk factors (Marino et al., 2018c), overlooking, in particular, social and peer influences. It is noteworthy that friends’ use of social media and social norms about social media use had a differential effect. On the one hand, adolescents’ perception of the frequency of use of social media by friends was positively associated with their own frequency of use, but not to their level of problematic use. This finding confirms, and extends, the literature about between-friends similarity (e.g., Mazur & Richards, 2011) indicating significant commonality of social media behaviour among friends. Since teens mainly engage in social media use in order to interact with close friends (e.g., Lenhart, 2015), it would appear that the more they perceive their friends’ use to be frequent, the more they are likely to use social media themselves. In turn, their own frequency of use increases the levels of PSMU. On the other hand, social norms predicted PSMU directly, whereas it was not significantly associated with adolescents’ frequency of use. Although we also expected this second association to emerge, this result suggests that peer pressure to use social media very frequently and expectations of constant availability in social media may be a direct risk factor for PSMU, which does not necessarily entail higher frequency of use per se. This is consistent with recent claims that problematic use of social media and Internet in general cannot be reduced to highly frequent use, that is, more time spent online (Marino et al., 2018c) and to theoretical suggestions about the potential role of social media features, such as constant availability, to shape online relations and behaviours of adolescents (Nesi et al., 2018a, Nesi et al., 2018b). Moreover, the effect of peer normative pressure is consistent with studies that have found people with higher conformity motives to use social media to be at increased risk of problematic use (Marino et al., 2018b). Finally, these findings and explanations evoke what has been recently labeled “availability stress”, indicating the distress “resulting from beliefs about others’ expectations that the individual respond and be available by digital means” (Steele, Hall, & Christofferson, 2019, p.4). From the perspective of prevention and intervention programs targeting adolescents’ misuse of social media, this finding clearly indicates the need to include discussions about social norms and expectations within the peer group, as well as activities aimed at increasing youth’s awareness and ability to resist peer pressure.

Regarding emotion regulation, findings confirmed that difficulties in emotion regulation significantly contribute to PSMU both directly and indirectly, via frequency of social media use and facilitating use of e-motions. The direct path, and the first indirect path, indicate that adolescents with difficulties in handling emotions are more likely to frequently use social media, and to incur in PSMU. A vast body of research has shown that problematic users are driven to use social media in the attempt to deal with unmanageable internal states online (for example, seeking distraction and avoiding emotional experiences) but, on the contrary, they frequently experience a negative mood modification (e.g., Hoge, Bickham, & Cantor, 2017). The second indirect path suggests that experiencing difficulties in emotion regulation increases adolescents’ beliefs about the usefulness of expressing emotions on social media for challenging tasks, such as improving interpersonal relationships and making decisions. Interestingly, although the bivariate correlation suggests that communicating own emotional state on social media is associated with a problematic pattern of social media use, the lack of a significant path between e-motions expression and PSMU in the overall model suggests that the crucial process associated with problematic use is the emphasis on expressing emotions on social media as a preferential tool for overcoming difficulties or strengthening relationships (i.e., “facilitating use of e-motions”), rather than mere expression of emotions online. This could maintain a vicious cycle in which the unique benefit of social media use for emotion regulation is sustained and it reinforces the belief of not being able to cope with emotions, thoughts, and decisions offline (Marino et al., 2019). Moreover, beliefs about the facilitating use of e-emotions might be linked to a strong preference for online social interactions (POSI; Caplan, 2010), as users can escape the discomfort of face-to-face interactions, feeling more comfortable in sharing emotions online. However, POSI, considered as one of the typical features of PSMU, puts user at greater risk to develop addictive symptoms because it represents the preferred way for social interaction and self-disclosure (Marino et al., 2017).

One important limitation of the current study is the cross-sectional design, which does not allow us to make definitive conclusions about the directionality of the effects. Indeed, the other way round is also plausible in that problematic users might be prone to use social media more often (thus indirectly influencing both social norms and friends’ use). Additionally, it could also be the case that PSMU is an antecedent of emotion dysregulation as previous studies indicated that problematic uses of technology are likely to co-occur with emotional distress among children and adolescents (e.g., Marino et al., 2018a, Restrepo et al., 2019). As a second limitation, the responses to the single item assessing the perceived frequency of social media use might be influenced by personal beliefs about what is considered “often” or “very often”. Therefore, future studies should assess this behavior in a more objective way, for example by asking participants to rate the number of times they access their social media and the amount of time they spend online.

Moreover, there are certainly other features of the social context of adolescents and of their internal regulatory processes that we did not consider in our model and merit future investigation. Nonetheless, this study adds to the growing literature about PSMU by showing the relative contribution of both social context and emotion-related aspects in adolescents’ social media use. Moreover, potential implications for practice can be highlighted. Results could inform preventive programs indicating that social-emotional approaches might be of value in tackling PSMU among adolescents. For example, social and emotional learning (SEL) has been demonstrated to be effective in modifying social dynamics and improving emotional skills (Durlak, Weissberg, Dymnicki, Taylor, & Schellinger, 2011).

Role of funding sources

This research did not receive any specific grant from funding agencies in the public, commercial, or not-for-profit sectors.

Contributors

Authors A, B, D, and E designed the study. Authors A and C wrote the protocol. Author A, B and C conducted literature searches and provided summaries of previous research studies. Author A and B conducted the statistical analysis. Author A wrote the first draft of the manuscript. Authors D and E performed study supervision. All authors contributed to and have approved the final manuscript.

Declaration of Competing Interest

None.

References

- Anderson J.C., Gerbing D.W. Structural equation modeling in practice: A review and recommended two - step approach. Psychological Bulletin. 1988;103:411–423. doi: 10.1037/0033-2909.103.3.411. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Bányai F., Zsila Á., Király O., Maraz A., Elekes Z., Griffiths M.D. Problematic social media use: Results from a large-scale nationally representative adolescent sample. PLoS One. 2017;12(1) doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0169839. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Billieux J., Maurage P., Lopez-Fernandez O., Kuss D.J., Griffiths M.D. Can disordered mobile phone use be considered a behavioral addiction? An update on current evidence and a comprehensive model for future research. Current Addiction Reports. 2015;2:156–162. doi: 10.1007/s40429-015-0054-y. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Bollen, K. A. (1989). Structural equations with latent variables. New York: Wiley. http://dx.doi.org/10.1002/9781118619179.

- Caplan S.E. Theory and measurement of generalized problematic Internet use: A two-step approach. Computers in Human Behavior. 2010;26:1089–1097. doi: 10.1016/j.chb.2010.03.012. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Casale S., Caplan S.E., Fioravanti G. Positive metacognitions about Internet use: The mediating role in the relationship between emotional dysregulation and problematic use. Addictive Behaviors. 2016;59:84–88. doi: 10.1016/j.addbeh.2016.03.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Casale S., Fioravanti G. Why narcissists are at risk for developing Facebook addiction: The need to be admired and the need to belong. Addictive Behaviors. 2018;76:312–318. doi: 10.1016/j.addbeh.2017.08.038. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Casale S., Rugai L., Fioravanti G. Exploring the role of positive metacognitions in explaining the association between the fear of missing out and social media addiction. Addictive Behaviors. 2018;85:83–87. doi: 10.1016/j.addbeh.2018.05.020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cohen, J. (1988). Statistical power analysis for behavioral science (2nd ed). Hillsdale, N.J.: Erlbaum. http://dx.doi.org/10.4324/9780203771587.

- Dholakia U.M., Bagozzi R.P., Pearo L.K. A social influence model of consumer participation in network-and small-group-based virtual communities. International Journal of Research in Marketing. 2004;21:241–263. doi: 10.1016/j.ijresmar.2003.12.004. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Durlak J.A., Weissberg R.P., Dymnicki A.B., Taylor R.D., Schellinger K.B. The impact of enhancing students’ social and emotional learning: A meta-analysis of school-based universal interventions. Child Development. 2011;82(1):405–432. doi: 10.1111/j.1467-8624.2010.01564.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fox J., Moreland J.J. The dark side of social networking sites: An exploration of the relational and psychological stressors associated with Facebook use and affordances. Computers in Human Behavior. 2015;45:168–176. doi: 10.1016/j.chb.2014.11.083. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Gratz K.L., Roemer L. Multidimensional assessment of emotion regulation and dysregulation: Development, factor structure, and initial validation of the difficulties. Journal of Psychopathology and Behavioral Assessment. 2004;26:41–54. [Google Scholar]

- Griffiths M.D., Kuss D. Adolescent social media addiction (revisited) Education and Health. 2017;35(3):49–52. [Google Scholar]

- Hawk S.T., van den Eijnden R.J., van Lissa C.J., ter Bogt T.F. Narcissistic adolescents' attention-seeking following social rejection: Links with social media disclosure, problematic social media use, and smartphone stress. Computers in Human Behavior. 2019;92:65–75. doi: 10.1016/j.chb.2018.10.032. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Hoge E., Bickham D., Cantor J. Digital media, anxiety, and depression in children. Pediatrics. 2017;140(Supplement 2):S76–S80. doi: 10.1542/peds.2016-1758G. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hormes J.M., Kearns B., Timko C.A. Craving Facebook? Behavioral addiction to online social networking and its association with emotion regulation deficits. Addiction. 2014;109(12):2079–2088. doi: 10.1111/add.12713. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jöreskog K.A., Sörbom D. Scientific Software; Chicago, IL: 1993. LISREL 8: Structural equation modelling with the SIMPLIS command language. [Google Scholar]

- Jӧreskog K.G., Sӧrbom D. Scientific Software International; Chicago: 1996. LISREL 8: User’s reference guide. [Google Scholar]

- Katsumata Y., Matsumoto T., Kitani M., Takeshima T. Electronic media use and suicidal ideation in Japanese adolescents. Psychiatry and Clinical Neurosciences. 2008;62(6):744–746. doi: 10.1111/j.1440-1819.2008.01880.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lenhart, A. (2015). Teens, technology, and friendships. Pew Research Center. August 6, 2015. Retrieved Online March 18, 2019 from http://www.pewinternet.org/2015/08/ 06/teens-technology-and-friendships/.

- Marino C. Quality of Social Media Use May Matter More than Frequency of Use for Adolescents’ Depression. Clinical Psychological Science. 2018;6(4):455. doi: 10.1177/2167702618771979. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Marino C., Caselli G., Vieno A., Lenzi M., Nikčević A.V., Spada M.M. Emotion Regulation and Desire Thinking as Predictors of Problematic Facebook Use. Psychiatric Quarterly. 2019;90(2):405–411. doi: 10.1007/s11126-019-09628-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Marino C., Gini G., Vieno A., Spada M.M. The associations between problematic Facebook use, psychological distress and well-being among adolescents and young adults: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Journal of Affective Disorders. 2018;226:274–281. doi: 10.1016/j.jad.2017.10.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Marino C., Gini G., Vieno A., Spada M.M. A Comprehensive Meta-Analysis on Problematic Facebook Use. Computers in Human Behavior. 2018;83:262–277. doi: 10.1016/j.chb.2018.02.009. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Marino C., Mazzieri E., Caselli G., Vieno A., Spada M.M. Motives to use Facebook and problematic Facebook use in adolescents. Journal of Behavioral Addictions. 2018;7(2):276–283. doi: 10.1556/2006.7.2018.32. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Marino C., Vieno A., Altoè G., Spada M.M. Factorial validity of the Problematic Facebook Use Scale for adolescents and young adults. Journal of Behavioral Addictions. 2017;6(1):5–10. doi: 10.1556/2006.6.2017.004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Marino C., Vieno A., Pastore M., Albery I.P., Frings D., Spada M.M. Modeling the contribution of personality, social identity and social norms to problematic Facebook use in adolescents. Addictive Behaviors. 2016;63:51–56. doi: 10.1016/j.addbeh.2016.07.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mazur E., Richards L. Adolescents' and emerging adults' social networking online: Homophily or diversity? Journal of Applied Developmental Psychology. 2011;32(4):180–188. doi: 10.1016/j.appdev.2011.03.001. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Mikami A.Y., Szwedo D.E. Social networking in online and offline contexts. In: Levesque R.J.R., editor. Encyclopedia of Adolescence. Springer; New York, NY: 2011. pp. 2801–2808. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Muthén L.K., Muthén B.O. Seventh Edition. Muthén & Muthén; Los Angeles, CA: 1998. Mplus User’s Guide. [Google Scholar]

- Nesi J., Choukas-Bradley S., Prinstein M.J. Transformation of adolescent peer relations in the social media context: Part 1—a theoretical framework and application to dyadic peer relationships. Clinical Child and Family Psychology Review. 2018;21(3):267–294. doi: 10.1007/s10567-018-0261-x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nesi J., Choukas-Bradley S., Prinstein M.J. Transformation of adolescent peer relations in the social media context: Part 2—application to peer group processes and future directions for research. Clinical Child and Family Psychology Review. 2018;21(3):295–319. doi: 10.1007/s10567-018-0262-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Niland P., Lyons A.C., Goodwin I., Hutton F. Friendship work on Facebook: Young adults’ understandings and practices of friendship. Journal of Community and Applied Social Psychology. 2015;25(2):123–137. doi: 10.1002/casp.2201. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Prinstein M.J., Dodge K.A. Guilford; New York: 2008. Understanding peer influence in children and adolescents. [Google Scholar]

- Restrepo, A., Scheininger, T., Clucas, J., Alexander, L., Salum, G., Georgiades, K., ... & Milham, M. (2019). Problematic Internet Use in Children and Adolescents: Associations with psychiatric disorders and impairment. medRxiv, 19005967. 10.1101/19005967. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- Shensa A., Escobar-Viera C.G., Sidani J.E., Bowman N.D., Marshal M.P., Primack B.A. Problematic social media use and depressive symptoms among U.S. young adults: A nationally-representative study. Social Science and Medicine. 2017;182:150–157. doi: 10.1016/j.socscimed.2017.03.061. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Siciliano V., Bastiani L., Mezzasalma L., Thanki D., Curzio O., Molinaro S. Validation of a new Short Problematic Internet Use Test in a nationally representative sample of adolescents. Computers in Human Behavior. 2015;45:177–184. doi: 10.1016/j.chb.2014.11.097. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Sighinolfi C., Norcini Pala A., Chiri L.R., Marchetti I., Sica C. Traduzione e adattamento italiano del Difficulties in Emotion Regulation Strategies una ricerca preliminare [The Italian version of the Difficulties in Emotion Regulation Scale (DERS): Preliminary data] Psicoterapia Cognitiva e Comportamentale. 2010;16(2):141–170. [Google Scholar]

- Spada M.M., Langston B., Nikčević A.V., Moneta G.B. The role of metacognitions in problematic Internet use. Computers in Human Behavior. 2008;24(5):2325–2335. doi: 10.1016/j.chb.2007.12.002. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Spada M.M., Marino C. Metacognitions and emotional regulation as predictors of problematic Internet use in adolescents. Clinical Neuropsychiatry. 2017;14(1):59–63. [Google Scholar]

- Steele R.G., Hall J.A., Christofferson J.L. Conceptualizing Digital Stress in Adolescents and Young Adults: Toward the Development of an Empirically Based Model. Clinical Child and Family Psychology Review. 2019 doi: 10.1007/s10567-019-00300-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Subrahmanyam K., Šmahel D. Springer; New York: 2011. Digital youth: The role of media in development. [Google Scholar]

- van den Eijnden R.J., Lemmens J.S., Valkenburg P.M. The social media disorder scale. Computers in Human Behavior. 2016;61:478–487. doi: 10.1016/j.chb.2016.03.038. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Wartberg L., Kriston L., Thomasius R. Internet gaming disorder and problematic social media use in a representative sample of German adolescents: Prevalence estimates, comorbid depressive symptoms and related psychosocial aspects. Computers in Human Behavior. 2020.;103:31–36. doi: 10.1016/j.chb.2019.09.014. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Yu J.J., Kim H., Hay I. Understanding adolescents’ problematic Internet use from a social/cognitive and addiction research framework. Computers in Human Behavior. 2013;29(6):2682–2689. doi: 10.1016/j.chb.2013.06.045. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Zych I., Ortega-Ruiz R., Marín-López I. Emotional content in cyberspace: Development and validation of E-motions Questionnaire in adolescents and young people. Psicothema. 2017;29(4):563–569. doi: 10.7334/psicothema2016.340. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]