Highlights

-

•

Presence of meaning in life is negatively associated with harmful drinking.

-

•

Searching for meaning in life is positively associated with harmful drinking.

-

•

Self-control and value of alcohol mediate the associations between meaning and harmful drinking.

-

•

These psychological mechanisms underlie transitions out of harmful drinking with meaning in life.

Keywords: Alcohol, Demand, Maturing out, Meaning in life, Self-control, Value

Abstract

Introduction

The adoption of adult roles that provide meaning in life is associated with reduced harmful drinking. The current study examined whether this relationship is mediated by increased self-control and reduced value of alcohol.

Methods

Cross-sectional design. 1043 adults (786 females) ≥18 years old completed an online survey. The outcome variable was scores on the Alcohol Use Disorders Identification Test (AUDIT), predictor variables were presence of and search for meaning in life (Meaning in Life Questionnaire), and mediating variables were trait self-control (Brief Self-Control Scale) and the value of alcohol (Brief Assessment of Alcohol Demand).

Results

Presence of meaning in life had a significant negative association (B = −0.01, SE = 0.00, 95% CI −0.02 to −0.00, p = .015), whilst search for meaning in life had a significant positive association (B = 0.01, SE = 0.00, 95% CI 0.01 to 0.02, p = .001) with AUDIT scores. The negative association was mediated by increased self-control (B = −0.09, SE = 0.01, 95% CI −0.12 to −0.06) and decreased value of alcohol (B = −0.02, SE = 0.01, 95% CI −0.04 to 0.00), whilst the positive association was mediated by decreased self-control (B = 0.05, SE = 0.01, 95% CI 0.03 to 0.07) and increased value of alcohol (B = 0.02, SE = 0.01, 95% CI 0.00 to 0.04), thereby supporting our hypotheses.

Conclusions

The relationships between presence and search for meaning in life and harmful drinking are mediated by individual differences in both trait self-control and the value of alcohol.

1. Introduction

Meaning in life (defined as the pursuit of intrinsically valued goals) is inversely associated with harmful drinking (Csabonyi and Phillips, 2017, Schnetzer et al., 2013), and reductions in harmful drinking are preceded by increased self-control (Quinn & Fromme, 2010) and reduced valuation of alcohol (Murphy & Dennhardt, 2016). In the present study we tested the hypothesis that associations between meaning in life and harmful drinking are mediated by self-control and valuation of alcohol.

Harmful alcohol consumption typically peaks and then declines during emerging adulthood (Britton, Ben-Shlomo, Benzeval, Kuh, & Bell, 2015). This “maturing-out” phenomenon (O’Malley, 2004) is often explained through the role incompatibility theory (Yamaguchi & Kandel, 1985) whereby the acquisition of adult roles and responsibilities is in direct conflict with harmful alcohol consumption and AUD (e.g. ‘role socialisation’). These adult roles typically include parenthood, marriage, cohabitation, and employment (Staff et al., 2014, Staff et al., 2010), all of which enable the formation of identity (Piotrowski, Brzezińska, & Pietrzak, 2013) which is related to establishing a sense of ‘meaning in life’ (Negru-Subtirica, Pop, Luyckx, Dezutter, & Steger, 2016). Meaning in life can be separated into ‘presence of meaning’; the extent to which a person pursues intrinsically valued goals and experiences meaning in their life, and the ‘search for meaning’; the extent to which a person is actively seeking meaning in their life. As people age, search for meaning in life declines whilst presence of meaning in life increases (Steger, Oishi, & Kashdan, 2009). Presence of meaning is inversely related to harmful alcohol consumption in young adults (Csabonyi & Phillips, 2017), students (Schnetzer et al., 2013) and people receiving treatment for AUD (Roos, Kirouac, Pearson, Fink, & Witkiewitz, 2015). The relationship between search for meaning in life and alcohol consumption has not been so intensively studied, although one study demonstrated a non-significant association between the two (Csabonyi & Phillips, 2017).

Changes in self-control might be an important psychological mechanism that accompanies the declining search and increasing presence of meaning in life. Self-control reflects the capacity to exert control over thoughts, emotions, and behaviours (de Ridder, Lensvelt-Mulders, Finkenauer, Stok, & Baumeister, 2012), and it is robustly negatively correlated with harmful drinking (de Ridder et al., 2012, Dvorak et al., 2011, Quinn and Fromme, 2010). Self-control is positively associated with presence of meaning in life and negatively associated with search for meaning in life (Li, Salcuni, & Delvecchio, 2019). One study demonstrated that the positive association between self-control and meaning in life was mediated by the perception of having structure in life (Stavrova, Pronk, & Kokkoris, 2018). Therefore, presence of meaning in life may facilitate and maintain self-control through the ability for a person to organise and structure their life, whereas this is potentially lacking in people who are searching for meaning in life. Taken together, increased meaning in life should promote increased self-control, which in turn should be associated with reduced alcohol consumption.

The presence of meaning in life may also alter the valuation of alcohol. Alcohol’s value can be measured through alcohol purchase tasks (Murphy and MacKillop, 2006, Owens et al., 2015) and concurrent choice tasks (Hogarth & Hardy, 2018), and is positively associated with harmful drinking (see MacKillop, 2016, for a review). When a person has valued life goals that are incompatible with harmful alcohol consumption, the benefits of alcohol may be outweighed by its costs (Miller & Rollnick, 2013). Indeed, the presence of meaning in life is inversely associated with the incentive salience of alcohol (Ostafin & Feyel, 2019), although the association between meaning in life and alcohol value has not yet been directly investigated.

The current study investigated whether meaning in life is associated with harmful drinking (assessed with the Alcohol Use Disorders Identification Test; AUDIT), and whether this association is mediated by individual differences in self-control and value of alcohol. Design, hypothesis and analysis strategy were pre-registered (https://aspredicted.org/xw583.pdf). Our hypotheses were:

-

1.

There will be a significant negative association between presence of meaning in life and AUDIT, and a significant positive association between searching for meaning in life and AUDIT.

-

2.

The hypothesised associations between meaning in life and AUDIT will be mediated by self-control and alcohol value.

2. Methods

2.1. Design

This was a cross-sectional observational study. The dependent variable was scores on the AUDIT, which provides an indication of hazardous drinking. Predictor variables included presence of meaning in life, and search for meaning in life. Mediator variables were trait self-control and value of alcohol. We aimed to recruit a minimum of 500 volunteers to have sufficient power to detect a small effect size (r = 0.10) in a mediation analysis with 80% power (Fritz & Mackinnon, 2007). We oversampled because we reached our recruitment target prior to the end of our testing period.

2.2. Participants

We recruited 1,146 (858 female) volunteers (age; M = 36.54, SD = 31.36) through social media platforms (Facebook and Twitter) between February and June 2018. The study was made available internationally. Inclusion criteria were age > 18 years and AUDIT > 0. After removal of outliers and incomplete responses, a total sample of 1,043 (786 female) participants (age; M = 35.51, SD = 12.95) remained (91.1% of the original sample) with ages ranging from 18 to 81 years old. The study was approved by the University of Liverpool research ethics committee, and all participants provided informed consent.

2.3. Measures

2.3.1. Outcome variable

Alcohol Use Disorders Identification Test (AUDIT; Saunders, Aasland, Babor, de la Fuente, & Grant, 1993): The full 10-item AUDIT had acceptable internal reliability, McDonald’s ω = 0.83 (McDonald, 1970, McDonald, 1999).

2.3.2. Predictor variable

The Meaning in Life Questionnaire (MLQ; Steger, Frazier, Oishi, & Kaler, 2006): This 10-item scale measures two dimensions: presence of meaning (how much respondents feel their lives have meaning), and search for meaning (how much respondents are striving to find meaning in their lives). Questions included “I have discovered a satisfying life purpose” and “I am looking for something that makes my life feel meaningful”. Participants responded on a scale ranging from 1 (absolutely untrue) to 7 (absolutely true). Higher scores indicate higher presence of meaning or search for meaning. The MLQ has good internal consistency, test–retest stability, convergent and discriminant validity (Steger et al., 2006). Each subscale had excellent internal reliability; presence, ω = 0.91, search ω = 0.91.

2.3.3. Mediating variables

Brief self-control scale (BSCS; Tangney, Baumeister, & Boone, 2004): This 13-item scale captures the extent to which people feel that they can resist external influences and control their behaviour, for example “I am able to work effectively toward long-term goals”. Participants responded on a 1 (not at all like me) to 5 (very much like me) scale. The BSCS had acceptable internal consistency, ω = 0.82.

Brief Assessment of Alcohol Demand (BAAD; Owens et al., 2015): This 3-item scale captures three indices of alcohol demand: intensity, Omax, and breakpoint. Intensity refers to alcohol consumption independent of price and was measured with the question “If drinks were free, how many would you have?” (Responses were multiple choice and ranged from: 0 to 10 drinks). Omax refers to the maximum expenditure on alcohol across differing prices, and was measured with the question “What is the maximum total amount you would spend on drinking during that drinking occasion?” (Responses were multiple choice, given in pounds, and ranged from £0 to £30 or more). Breakpoint refers to the first price that suppresses consumption to zero and was measured with the question “What is the maximum you would pay for a single drink?” (Reponses were multiple choice, given in pounds, and ranged from £0 to £15 or more). We included a link to a currency converter so that respondents outside of the United Kingdom could provide an accurate answer.

2.3.4. Additional questions

We obtained demographic information on age and gender, and other demographic and lifestyle questions (see Supplementary material).

2.4. Data reduction and analyses

Both subscales of the MLQ demonstrate convergent and discriminant validity (Steger et al., 2006) and previous research using the MLQ has explored these subscales separately and demonstrated dissociable effects for presence of meaning in life and search for meaning in life (Csabonyi and Phillips, 2017, Li et al., 2019). Therefore, we included these subscales of meaning in life separately in our analyses.

Hierarchical regression was used to investigate the associations between meaning in life and AUDIT scores. AUDIT scores were square root transformed to improve the distribution. We adjusted for gender and age because these factors are associated with alcohol use (Chaiyasong et al., 2018).

We computed a composite measure of BAAD because intensity, Omax, and breakpoint were significantly inter-correlated (intensity and Omax, r = 0.54; intensity and breakpoint, r = 0.13; Omax and breakpoint, r = 0.45; all p’s < 0.01), and thus they were z-scored and combined. This was our proxy for alcohol value, which had acceptable internal reliability, ω = 0.70.

PROCESS (Hayes, 2012) was used to investigate whether the associations between meaning in life and AUDIT scores were mediated by trait self-control and / or alcohol value. We calculated bias-corrected, bootstrapped (5000 samples) confidence intervals.

In total, 103 cases were removed prior to analysis. See supplementary materials for justification and a sensitivity analysis that included all cases.

3. Results

Descriptive statistics are presented in supplementary materials. Approximately half of the sample (504 participants; 48.32%) were hazardous or harmful drinkers (AUDIT ≥ 7).

The associations between meaning in life and AUDIT scores (Table 1).

Table 1.

Hierarchical regression predicting AUDIT scores, predictor variables presence of meaning and search for meaning in life, after controlling for age and gender.

| Variable | Cumulative |

Simultaneous |

||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| R2-change | F-change | B | B (SE) | β | p | |

| Step 1 | ||||||

| Age | 0.09 | F(2,1040) = 51.07** | −0.02 | 0.00 | −0.24 | p < .001 |

| Gender | −0.19 | 0.06 | −0.09 | p = .004 | ||

| Step 2 | ||||||

| Presence | 0.02 | F(2,1038) = 11.05** | −0.01 | 0.00 | −0.08 | p = .015 |

| Search | 0.01 | 0.00 | 0.10 | p = .001 | ||

p < .001.

The regression model accounted for 11% of the variance in AUDIT scores (Adjusted R2 = 0.11, F(4,1038) = 31.56, p < .001, Cohen’s f2 = 0.12). Age (95% CI −0.02 to −0.01) and gender (95% CI −0.31 to −0.06) predicted approximately 9% of variance (Cohen’s f2 = 0.10). Presence of meaning in life (95% CI −0.02 to −0.00) and search for meaning in life (95% CI 0.01 to 0.02) predicted an additional 2% of variance (Cohen’s f2 = 0.02).

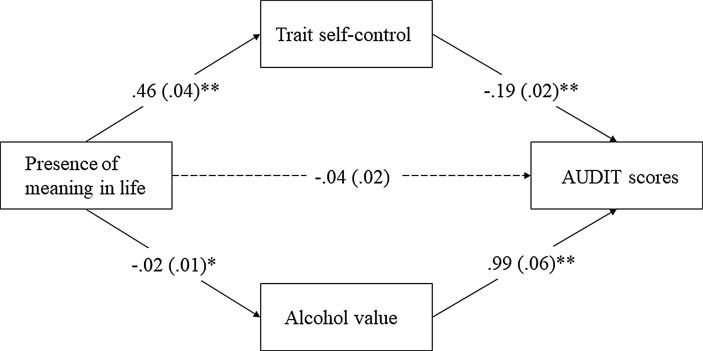

Mediation of the associations between meaning in life and AUDIT scores by self-control and value of alcohol (Fig. 1, Fig. 2).

Fig. 1.

A multiple-mediation pathway of the indirect effect of presence of meaning in life on AUDIT that was mediated by self-control and alcohol value. Values are unstandardized coefficients and standard errors. **p < .001, *p = .05.

Fig. 2.

A multiple-mediation pathway of the indirect effect of search for meaning in life on AUDIT that was mediated by self-control and alcohol value. Values are unstandardized coefficients and standard errors. **p < .001, *p < .05.

The direct effect of presence of meaning in life on AUDIT was not significant (B = −0.04, SE = 0.02, p = .087, 95% CI −0.08 to 0.01). However, the indirect effect of self-control (B = −0.09, SE = 0.01, 95% CI −0.12 to −0.06) was statistically significant and the indirect effect of alcohol value (B = −0.02, SE = 0.01, 95% CI −0.04 to 0.00) was marginally significant (see Fig. 1). Taken together, in the model accounting for all mediators, presence of meaning in life explained 35% of the variance in AUDIT (R2 = 0.35, p < .001). This demonstrates that the negative association between presence of meaning in life and AUDIT was mediated by increased self-control and decreased alcohol value.

Regarding search for meaning in life, the direct effect of search on AUDIT was statistically significant (B = 0.07, SE = 0.02, p < .001, 95% CI 0.03 to 0.11) and the indirect effects of self-control (B = 0.05, SE = 0.01, 95% CI 0.03 to 0.07) and alcohol value (B = 0.02, SE = 0.01, 95% CI 0.00 to 0.04) were statistically significant (see Fig. 2). Taken together, in the model accounting for all mediators, search for meaning in life explained 36% of the variance in AUDIT (R2 = 0.36, p < .001). This demonstrates that the positive association between search for meaning in life and AUDIT was partially mediated by decreased self-control and increased alcohol value.

4. Discussion

As hypothesized, a hierarchical regression demonstrated that elevated AUDIT scores were negatively associated with presence of meaning in life but positively associated with search for meaning in life, after adjusting for demographic factors. In order to explore the observed association between meaning in life and AUDIT, we conducted mediation analyses which showed that both of these associations were mediated by trait self-control and value of alcohol. These findings are a step towards understanding the psychological mechanisms through which increasing presence of meaning in life and reduced search for meaning in life might cause people to reduce their alcohol intake.

Our findings replicate recent research demonstrating that self-control is positively associated with presence of meaning in life and negatively associated with search for meaning in life (Li et al., 2019). Given that having a sense of structure in life has been found to mediate the positive association between presence of meaning in life and self-control (Stavrova et al., 2018), it may be that when a person acquires or enters into adult roles that provide meaning in life this leads to a structured lifestyle (e.g. having children or stable employment and an early waking routine). In turn, this should facilitate self-control which is robustly associated with reduced alcohol consumption (de Ridder et al., 2012, Dvorak et al., 2011, Quinn and Fromme, 2010).

Our study was the first direct investigation of the relationship between meaning in life and the value of alcohol. Our finding that value of alcohol is negatively associated with presence of meaning in life and positively associated with search for meaning in life may be explained by the costs of harmful alcohol consumption (e.g. being hungover for work or childcare) outweighing and outlasting the benefits (e.g. euphoric effects and intoxication) (Miller & Rollnick, 2013). Consequently, the reduced benefit and increased cost of consuming alcohol may result in reductions in the value that is ascribed to alcohol. Indeed, the value of alcohol is positively associated with harmful drinking (MacKillop, 2016), and therefore this should lead to reduced alcohol consumption.

Our study has some important limitations, and our findings identify important avenues for future research. As with all online self-report measures, participants’ responses could have been biased (Rosenman, Tennekoon, & Hill, 2011) and the use of an online convenience sample limits the generalisability of the findings. A further limitation is the use of mediation analyses on cross-sectional, observational data, which may yield biased estimates of effects (Fairchild & McDaniel, 2017). Furthermore, although our findings are robust, meaning in life accounted for only 2% of the variance in AUDIT scores and the effect size was small in magnitude. The decline in drinking during emerging adulthood (Britton et al., 2015), often referred to as “maturing-out” (O’Malley, 2004) may be underpinned by changes in self-control (Littlefield, Sher, & Wood, 2009) and socialisation into social roles that provide meaning in life (Lee, Ellingson, & Sher, 2015). Our findings implicate developmental changes in self-control and alcohol value as candidate psychological mechanisms that may underlie maturing out. Conversely, failures to mature out of harmful drinking during early adulthood could be partly attributed to inflexible self-control and alcohol value. Future prospective or cohort studies are needed to determine the directionality of these associations.

In conclusion, this study demonstrated that meaning in life is associated with harmful drinking, and these associations were mediated by the value of alcohol and trait self-control. These findings have potential implications for our understanding of the psychological mechanisms that underlie developmental transitions out of harmful drinking, or the persistence of harmful drinking into early adulthood.

CRediT authorship contribution statement

Amber Copeland: Conceptualization, Methodology, Software, Formal analysis, Writing - original draft, Visualization, Investigation, Writing - review & editing. Andrew Jones: Software, Supervision, Validation, Writing - review & editing. Matt Field: Conceptualization, Methodology, Supervision, Validation, Writing - review & editing.

Declaration of Competing Interest

All authors declare that they have no conflicts of interest.

Footnotes

Supplementary data to this article can be found online at https://doi.org/10.1016/j.abrep.2020.100258.

Appendix A. Supplementary material

The following are the Supplementary data to this article:

References

- Britton A., Ben-Shlomo Y., Benzeval M., Kuh D., Bell S. Life course trajectories of alcohol consumption in the United Kingdom using longitudinal data from nine cohort studies. BMC Medicine. 2015;13(1):47. doi: 10.1186/s12916-015-0273-z. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chaiyasong S., Huckle T., Mackintosh A.-M., Meier P., Parry C.D.H., Callinan S.…Casswell S. Drinking patterns vary by gender, age and country-level income: Cross-country analysis of the International Alcohol Control Study. Drug and Alcohol Review. 2018;37:S53–S62. doi: 10.1111/dar.12820. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Csabonyi M., Phillips L.J. Meaning in life and substance use. Journal of Humanistic Psychology. 2017;57:1–17. doi: 10.1177/0022167816687674. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- de Ridder T.D., Lensvelt-Mulders G., Finkenauer C., Stok F.M., Baumeister R.F. Taking stock of self-control: A meta-analysis of how trait self-control relates to a wide range of behaviors. Personality and Social Psychology Review. 2012;16(1):76–99. doi: 10.1177/1088868311418749. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dvorak R.D., Simons J.S., Wray T.B. Alcohol use and problem severity: Associations with dual systems of self-control. Journal of Studies on Alcohol and Drugs. 2011;72(4):678–684. doi: 10.15288/jsad.2011.72.678. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fairchild A.J., McDaniel H.L. Best (but oft-forgotten) practices: Mediation analysis. The American Journal of Clinical Nutrition. 2017;105(6):1259–1271. doi: 10.3945/ajcn.117.152546. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fritz M.S., Mackinnon D.P. Required sample size to detect the mediated effect. Psychological Science. 2007;18(3):233–239. doi: 10.1111/j.1467-9280.2007.01882.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hayes, A. F. (2012). PROCESS: A versatile computational tool for observed variable mediation, moderation, and conditional process modeling [White paper]. Retrieved from <http://www.afhayes.com/ public/process2012.pdf>.

- Hogarth L., Hardy L. Alcohol use disorder symptoms are associated with greater relative value ascribed to alcohol, but not greater discounting of costs imposed on alcohol. Psychopharmacology. 2018;235(8):2257–2266. doi: 10.1007/s00213-018-4922-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lee M.R., Ellingson J.M., Sher K.J. Integrating social-contextual and intrapersonal mechanisms of “maturing out”: Joint influences of familial-role transitions and personality maturation on problem-drinking reductions. Alcoholism, Clinical and Experimental Research. 2015;39(9):1775–1787. doi: 10.1111/acer.12816. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li J.-B., Salcuni S., Delvecchio E. Meaning in life, self-control and psychological distress among adolescents: A cross-national study. Psychiatry Research. 2019;272:122–129. doi: 10.1016/J.PSYCHRES.2018.12.033. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Littlefield A.K., Sher K.J., Wood P.K. Is “maturing out” of problematic alcohol involvement related to personality change? Journal of Abnormal Psychology. 2009;118(2):360–374. doi: 10.1037/a0015125. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- MacKillop J. The behavioral economics and neuroeconomics of alcohol use disorders. Alcoholism, Clinical and Experimental Research. 2016;40(4):672–685. doi: 10.1111/acer.13004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McDonald R.P. The theoretical foundations of principal factor analysis, canonical factor analysis, and alpha factor analysis. British Journal of Mathematical and Statistical Psychology. 1970;23(1):1–21. doi: 10.1111/j.2044-8317.1970.tb00432.x. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- McDonald R.P. Test theory: A unified treatment. L. Erlbaum Associates. 1999 [Google Scholar]

- Miller W.R., Rollnick S. 3rd ed. Guilford Press; New York, NY: 2013. Motivational interviewing: Helping people change. [Google Scholar]

- Murphy J.G., Dennhardt A.A. The behavioral economics of young adult substance abuse. Preventive Medicine. 2016;92:24–30. doi: 10.1016/j.ypmed.2016.04.022. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Murphy J.G., MacKillop J. Relative reinforcing efficacy of alcohol among college student drinkers. Experimental and Clinical Psychopharmacology. 2006;14(2):219–227. doi: 10.1037/1064-1297.14.2.219. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Negru-Subtirica O., Pop E.I., Luyckx K., Dezutter J., Steger M.F. The meaningful identity: A longitudinal look at the interplay between identity and meaning in life in adolescence. Developmental Psychology. 2016;52(11):1926–1936. doi: 10.1037/dev0000176. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- O’Malley P.M. Maturing out of problematic alcohol use. Alcohol Research & Health. 2004;28(4):202–204. https://psycnet.apa.org/record/2006-01535-005 Retrieved from. [Google Scholar]

- Ostafin B.D., Feyel N. The effects of a brief meaning in life intervention on the incentive salience of alcohol. Addictive Behaviors. 2019;90:107–111. doi: 10.1016/j.addbeh.2018.10.035. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Owens M.M., Murphy C.M., MacKillop J. Initial development of a brief behavioral economic assessment of alcohol demand. Psychology of Consciousness: Theory, Research, and Practice. 2015;2(2):144–152. doi: 10.1037/cns0000056. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Piotrowski K., Brzezińska A.I., Pietrzak J. Four statuses of adulthood: Adult roles, psychosocial maturity and identity formation in emerging adulthood. Health Psychology Report. 2013;1:52–62. doi: 10.5114/hpr.2013.40469. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Quinn P.D., Fromme K. Self-regulation as a protective factor against risky drinking and sexual behavior. Psychology of Addictive Behaviors. 2010;24(3):376–385. doi: 10.1037/a0018547. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Roos C.R., Kirouac M., Pearson M.R., Fink B.C., Witkiewitz K. Examining temptation to drink from an existential perspective: Associations among temptation, purpose in life, and drinking outcomes. Psychology of Addictive Behaviors. 2015;29(3):716–724. doi: 10.1037/adb0000063. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rosenman R., Tennekoon V., Hill L.G. Measuring bias in self-reported data. International Journal of Behavioural & Healthcare Research. 2011;2(4):320–332. doi: 10.1504/IJBHR.2011.043414. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Saunders J.B., Aasland O.G., Babor T.F., de la Fuente J.R., Grant M. Development of the Alcohol Use Disorders Identification Test (AUDIT): WHO Collaborative Project on Early Detection of Persons with Harmful Alcohol Consumption–II. Addiction. 1993;88(6):791–804. doi: 10.1111/j.1360-0443.1993.tb02093.x. http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/8329970 Retrieved from. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schnetzer L.W., Schulenberg S.E., Buchanan E.M. Differential associations among alcohol use, depression and perceived life meaning in male and female college students. Journal of Substance Use. 2013;18(4):311–319. doi: 10.3109/14659891.2012.661026. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Staff J., Greene K.M., Maggs J.L., Schoon I. Family transitions and changes in drinking from adolescence through mid-life. Addiction. 2014;109(2):227–236. doi: 10.1111/add.12394. http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/24571025 Retrieved from. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Staff J., Schulenberg J.E., Maslowsky J., Bachman J.G., O’Malley P.M., Maggs J.L., Johnston L.D. Substance use changes and social role transitions: Proximal developmental effects on ongoing trajectories from late adolescence through early adulthood. Development and Psychopathology. 2010;22(4):917–932. doi: 10.1017/S0954579410000544. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stavrova O., Pronk T., Kokkoris M.D. Finding meaning in self-control: The effect of self-control on the perception of meaning in life. Self and Identity. 2018;1–18 doi: 10.1080/15298868.2018.1558107. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Steger M.F., Frazier P., Oishi S., Kaler M. The meaning in life questionnaire: Assessing the presence of and search for meaning in life. Journal of Counseling Psychology. 2006;53(1):80–93. doi: 10.1037/0022-0167.53.1.80. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Steger M.F., Oishi S., Kashdan T.B. Meaning in life across the life span: Levels and correlates of meaning in life from emerging adulthood to older adulthood. The Journal of Positive Psychology. 2009;4(1):43–52. doi: 10.1080/17439760802303127. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Tangney J.P., Baumeister R.F., Boone A.L. High self-control predicts good adjustment, less pathology, better grades, and interpersonal success. Journal of Personality. 2004;72(2):271–324. doi: 10.1111/j.0022-3506.2004.00263.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yamaguchi K., Kandel D.B. Dynamic relationships between premarital cohabitation and illicit drug use: An event-history analysis of role selection and role socialization. American Sociological Review. 1985;50(4):530–546. doi: 10.2307/2095437. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.