Summary

Prior studies have supported the effectiveness of the use of Lay Health Workers (LHWs) as an intervention model for managing chronic health conditions, yet few have documented the mechanisms that underlie the effectiveness of the interventions. This study provides a first look into how LHWs delivered a family-based intervention and the challenges encountered. We utilize observation data from LHW-led educational sessions delivered as part of a randomized controlled trial (RCT) designed to test a LHW outreach family-based intervention to promote smoking cessation among Vietnamese American smokers. The RCT included experimental (smoking cessation) and control (healthy living) arms. Vietnamese LHWs were trained to provide health information in Vietnamese to groups of family dyads (smoker and family member). Bilingual, bicultural research team members conducted unobtrusive observations in a subset of LHW educational sessions and described the setting, process and activities in structured fieldnotes. Two team members coded each fieldnote following a grounded theory approach. We utilized Atlas.ti qualitative software to organize coding and facilitate combined analysis. Findings offer a detailed look at the ‘black box’ of how LHWs work with their participants to deliver health messages. LHWs utilized multiple relational strategies, including preparing an environment that enables relationship building, using recognized teaching methods to engage learners and co-learners as well as using humor and employing culturally specific strategies such as hierarchical forms of address to create trust. Future research will assess the effectiveness of LHW techniques, thus enhancing the potential of LHW interventions to promote health among underserved populations.

Keywords: lay health worker, smoking cessation, diet and physical activity, Vietnamese Americans

INTRODUCTION

The use of lay health workers (LHW) to address health disparities and inequities has a long history in Latin America and around the world. LHWs have been known by many different names (e.g. lay health advisors, peer educators, community health workers, promotoras) (Rodney et al., 1998; Hunter et al., 2004; Mock et al., 2006). They are members of the community of focus who speak the same language and share similar cultural backgrounds and/or social connections; because of their backgrounds and connections, they can be effective in delivering health messages in a trusted and culturally appropriate manner (Pasick et al., 2009). LHWs have been shown to be effective in addressing health disparities (Nguyen et al., 2016; Finlayson et al., 2017), improving health outcomes (Patel et al., 2011; Hsu et al., 2016; Puchalski Ritchie et al., 2016; Viramontes et al., 2017) and improving health- and screening-related behaviors (Han et al., 2008; Hou et al., 2011; Byrd et al., 2013; deRosset et al., 2014; Fernandez et al., 2014; Juon et al., 2016) There are however important differences between programs in the status LHWs hold and the roles they play. In many programs, LHWs are central to outreach activity and work directly with community members to provide social support (Navarro et al., 1998; Mock et al., 2006; Taylor et al., 2010), offer practical assistance to facilitate access to health care (Burke et al., 2004a,b; Taylor et al., 2009; Kim et al., 2016) and provide health education, counseling and case management (Kim et al., 2016). Recent research has attempted to delineate the appropriate roles and skills LHWs should have (Nemcek and Sabatier, 2003; Glenton et al., 2013; South et al., 2013) and has identified cancer prevention and cardiovascular disease as the most common health targets of LHW interventions (Kim et al., 2016).

LHWs’ involvement in addressing health disparities dates back to the 1950s (Mock et al., 2006; Molokwu et al., 2016) where LHWs emerged in Latin America as part of the liberation theology movement influenced by Paolo Friere’s approach to popular education (Mock et al., 2006; Pérez and Martinez, 2008). In the United States, LHWs appeared in the 1960s as part of the new careers program of the Great Society Domestic Programs (Nemcek and Sabatier, 2003; Pérez and Martinez, 2008). These positions gained federal government support through the Federal Migrant Health Act of 1962 and the Economic Opportunity Act of 1964 (Zuvekas et al., 1999; Nemcek and Sabatier, 2003). LHW programs waned in the US in the 1970s and early 1980s and reemerged in the late 1980s and 1990s primarily in migrant and farmworker communities (Nemcek and Sabatier, 2003; Pérez and Martinez, 2008). Since 2008, Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services has allowed Medicaid to reimburse community health workers among other listed non-clinically licensed providers to provide preventive services ordered by physicians or licensed healthcare providers (Rosenthal et al., 2010; ASTHO n.d.).

The American Public Health Association’s Community Health Worker Section supported the Community Health Worker Core Consensus Project that developed a set of recommendations for core community health worker roles, skills and qualities (C3 Project, 2013). Table 1 details the skills outlined, which were drawn from community health worker programs across the United States.

Table 1:

APHA CHW section skills recommendations (C3 Project, n.d., p. 3)

| Community Health Worker Skills |

|---|

| Communication |

| Interpersonal and Relationship Building |

| Service Coordination and Navigation |

| Capacity Building |

| Advocacy |

| Education and Facilitation |

| Individual and Community Assessment |

| Outreach |

Despite this long history and such detailed delineation of skills, data is still scant on the processes by which LHWs do their work (Lewin et al., 2005; Glenton et al., 2011, 2013). A systematic review of 61 LHW interventions published through 2014 concluded that LHW interventions are effective particularly in underserved and minority populations, yet few of these studies describe or document the mechanisms that underlie the effectiveness of these interventions (Kim et al., 2016). A 2013 Cochrane Review argued, ‘For LHW programs to be effective, we need better understanding of the factors that influence their success and sustainability’ (Glenton et al., 2013). This study aims to identify and describe the processes through which LHWs promoted either (i) smoking cessation, or (ii) healthy eating and physical activity among Vietnamese American smokers and their family members. The study utilizes observation data from LHW-led educational sessions delivered as part of a randomized controlled trial (RCT) designed to test a LHW outreach family-based intervention to promote smoking cessation among Vietnamese American male smokers. The LHW-delivered family-based smoking cessation intervention was developed and tested in a feasibility study that yielded promising smoking abstinence rates at 3-months (Tsoh et al., 2015). The goals of this qualitative study are to describe how LHWs delivered the family-based intervention on two different health topics and the challenges they encountered.

METHODS

We partnered with two community-based organizations to recruit and train 18 Vietnamese women and men (9 per CBO) to serve as LHWs. LHW eligibility criteria were: age 18 and older, self-identified as Vietnamese, able to speak and read Vietnamese, had not smoked cigarettes in the past 12 months and had never received certification or licensure in the US as a health professional. Each LHW was paid $1,200 for approximately 50 hours of work that included receiving training, conducting outreach activities (recruiting smoker-family dyad participants, conducting education sessions and follow-up telephone calls), as well as completing study documentation. LHWs participated in three 4-hour training sessions. The first session provided an overview of the research project and recruitment procedures. Following this introduction, LHWs recruited participants. Our partner CBOs worked with LHWs through their social networks to recruit 107 dyads. Each dyad included one smoker and one family member. Eligibility criteria for smokers included: age 18 and older, self-identified ethnic Vietnamese, able to speak and read Vietnamese and having smoked daily in the previous 7 days. Eligible family members were those living in the same household as the participating smoker. All participants received a $70 incentive after completing three assessment telephone interviews. Of note, participants were reimbursed only for their time completing the research assessment, not for attending or participating in the intervention activities led by the LHWs. All research activities were conducted in Northern California.

LHWs were not randomized into either the Smoking Cessation (SC, experimental) or Healthy Living (HL, control) groups until they had completed recruitment of at least six eligible smoker-family dyads (See Tsoh et al., 2015 for further detail on the RCT). After randomization, LHWs participated in two training sessions on the assigned health topic. Each LHW received a Vietnamese-language flipchart to use in their education sessions explaining either (i) the harms of smoking, possible strategies and tools to use for quitting and ways family members can provide support; or (ii) the importance of exercise and healthy diet, components of a balanced diet and physical activity options and ways family members can support each other. All training and intervention activities were conducted in Vietnamese.

LHWs were instructed to limit each of the two small group education sessions to 90 minutes or less, to include two to three dyads in each session, to ensure readability of the flipchart for each participant and to optimize participants’ engagement in discussions. The training focused on mastery of the flip chart content. Facilitation style and delivery were not addressed. Instead, LHWs were asked to use the style and approach they felt would be most comfortable and effective to deliver health information. The first session aimed to provide information on the importance of the health issue and resources and tools available. The second session aimed to provide a quick review of the key information learned in the first session, additional information related to the health topic and discussion of commonly asked questions. At the end of both sessions, LHWs were instructed to engage participants in setting their personal and/or family goals by filling out the ‘Healthy Family Action Plan’. The Action Plan was a form on which participants identified actions that each would take individually with support from the other over the course of the coming week to move toward their health goals. For smokers this might include calling the Vietnamese language smoker quitline, or talking with their doctor about nicotine-replacement therapy (NRT). For their family members this might include making smokers’ favorite snacks to help with cravings, or more consistently enforcing indoor smoking bans. In the Healthy Living group, actions might include walking together more, or cutting down on rice consumption. If participants wanted to discuss smoking in the healthy living group, or diet/nutrition in the smoking cessation group, LHWs were instructed to answer questions as appropriate, to redirect to the topic at hand and to defer answers to questions not addressed on the flip chart to a follow-up conversation. LHWs made two follow-up phone calls, each within 1 to 2 weeks after the education sessions to each participant to answer questions, review progress on the Healthy Family Action Plan and encourage participants to continue their participation.

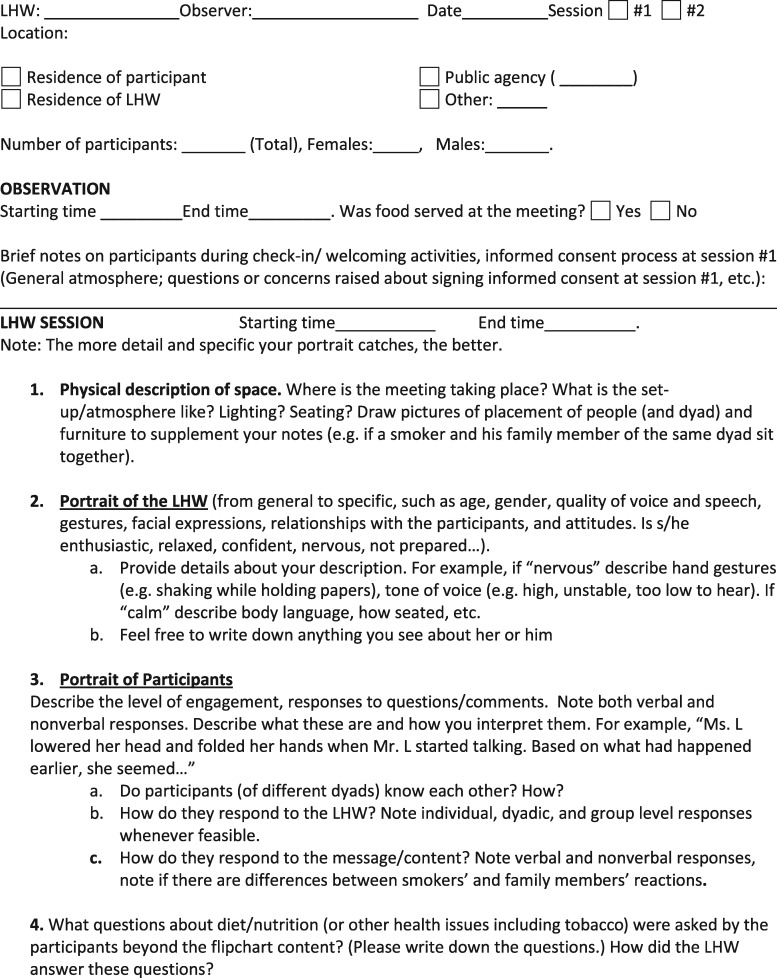

Bilingual, bicultural research team members conducted unobtrusive observations in a subset of LHW educational sessions to collect descriptive data—recorded in field notes—about the setting, process and activities. Observers took photographs and recorded detailed field notes immediately after each LHW session on a structured form (Figure 1 ) that requested description of: (i) educational session context (e.g. home décor and neighborhood, how LHWs used the physical space during the session, food provided, etc.), (ii) LHW and participants (age and gender) and (iii) LHW/participant interactions (facial expressions, hand gestures, speech, posture, knowledge of material, presentation style, etc.) (Bernard, 2010). The forms included a space to either insert photographs or draw a map of where participants were seated. The photographs and maps supported observer notes describing the impact of space/seating arrangement on session delivery. One team member observed each session. Observers were trained to remain on the sidelines with other research staff and to disrupt session flow as minimally as possible (Fetterman, 1997; Bernard 2010). Observation notes were recorded in English. Both LHWs and their participants provided written consent for the possibility of being observed prior to participation in the study. In addition, at the beginning of each observed session, we requested verbal consent from the LHW and each participant to observe the session and to take photographs.

Fig. 1.

Observation form.

Two team members coded each observational field note following a grounded theory approach (Charmaz, 2006) and met weekly to discuss codes and emergent themes. Where there was disagreement, discussion continued until consensus was reached. Emerging themes and case examples were discussed with the larger research team in monthly meetings. We utilized Atlas.ti qualitative software (ATLAS.ti Scientific Software Development GmbH, Berlin, 2013) to organize the coding and facilitate the combined analysis. The University of California San Francisco Institutional Review Board approved all study procedures.

RESULTS

Our CBO partners recruited seven men and eleven women to work as LHWs. The average age of the nine LHWs was 55.7 years old. LHW demographic characteristic are detailed in Table 2 . A majority of LHWs had some college education and beyond (82.4%) and 55.5% reported limited English proficiency (spoke English less than ‘well’). Among the 18 LHW who were recruited, one-third had had prior experience as a LHW in other research studies. LHWs reported wanting to learn, family concerns, LHW incentive and value of the experience for future employment as motivations for participating in the study. Demographic characteristics of the 55 smoker/family member dyads observed are detailed in Table 3 . The average age of the 55 male smoker participants was 56.2 years old, 89.1% spoke English less than ‘well’, 40% had an annual household income less than $20 000 per year, 56.5% were employed and 38.2% had not completed high school. The 55 family member participants included 6 men and 49 women; their average age was 53.1. Family members had similar sociodemographic characteristics as the smokers: 94.6% spoke English less than ‘well’, 49.1% were employed and 38.2% had not completed high school.

Table 2:

Lay health worker characteristics (N= 18 LHWs)

| n (%) or mean (SD, range) | |

|---|---|

| Age Mean | 55.6 (12.6, 25 – 72) |

| <50 | 4 (22.2%) |

| 50 – 64 | 9 (50.0%) |

| 65+ | 5 (27.8%) |

| Gender | |

| Male | 7 (38.9%) |

| Female | 11 (61.1%) |

| Education | |

| <High school | 0 (0.0%) |

| High school | 3 (16.7%) |

| Some college or beyond | 15 (83.3%) |

| Employment | |

| Employed | 9 (50%) |

| Unemployed | 1 (5.6%) |

| Homemaker | 0 (0.0%) |

| Student/retired | 8 (44.4%) |

| Spoken English Proficiency | |

| Fluent/Well | 8 (44.5%) |

| Limited (so-so, poor, not at all) | 10 (55.5%) |

| Former Lay Health Worker Experience | |

| Yes | 6 (33.3%) |

| No | 12 (66.7%) |

Table 3:

Smokers and family characteristics (N=55 Smoker-Family Dyads)

| Smokers, n (%) or mean (SD, range) | Family member participants, n (%) or mean (SD, range) | |

|---|---|---|

| Age Mean (SD, Range) | 56.2 (13.5, 20 – 77) | 53.1 (15.0, 19 – 75) |

| <50 | 15 (27.3%) | 15 (27.3%) |

| 50 – 64 | 23 (41.8%) | 32 (58.2%) |

| 65+ | 17 (30.9%) | 8 (14.5%) |

| Gender | ||

| Male | 55 (100.0%) | 6 (10.9%) |

| Female | 0 (0%) | 49 (89.1%) |

| Relationship to Smoker | ||

| Spouse | Not Applicable | 35 (63.6%) |

| Parent/child | – | 6 (11.0%) |

| Sibling | – | 3 (5.5%) |

| Other | – | 11 (20.0%) |

| Education | ||

| <high school | 18 (32.7%) | 21 (38.2%) |

| High school | 8 (14.5%) | 16 (29.1%) |

| Some college or beyond | 29 (52.7%) | 17 (30.9%) |

| Don’t Know/Refused | 0 (0.0%) | 1 (`1.8%) |

| Marital Status | ||

| Married/Living with partner | 41 (74.5%) | 41 (74.5%) |

| Employment | ||

| Employed | 31 (56.5%) | 27 (49.1%) |

| Unemployed | 5 (9.1%) | 2 (3.6%) |

| Homemaker | 0 (0.0%) | 18 (32.7%) |

| Student/retired | 10 (18.2%) | 7 (12.8%) |

| Unable to work/Other/Don’t know/refused | 9 (16.4%) | 1 (1.8%) |

| Annual Household Income | ||

| <$20 000 | 22 (40.0%) | 23 (41.8%) |

| $20 000 and above | 19 (34.5%) | 13 (23.6%) |

| Don’t Know/Refused | 14 (25.5%) | 19 (34.5%) |

| Spoken English Proficiency | ||

| Fluent/Well | 6 (10.9%) | 3 (5.4%) |

| Limited (so-so, poor, not at all) | 49 (89.1%) | 52 (94.6%) |

| Smoking status | ||

| Never smoked >100 cigarettes in lifetime | 0 (0.0%) | 52 (94.5%) |

| Former smoker | 0 (0.0%) | 3 (5.5%) |

| Current smoker | 55 (100.0%) | 0 (0.0%) |

| Cigarettes smoked per day Mean (SD, Range) | 7.4 (5.9, 1 – 23) | 0 (0.0%) |

| Years smoked Mean (SD, Range) | 30.2 (17.5, 1 – 60) | Not applicable |

| Intention to quit smoking in next 6 months | ||

| Yes | 42 (80.8%) | Not applicable |

| No | 13 (19.2%) | – |

Note: Column percentages may not add up to 100.0% due to rounding.

We observed 25 LHW educational sessions consisting of 2 to 4 dyads per group. The average duration of the sessions was 60 minutes (range: 37 to 94 minutes). Slightly over half (56%) of these observations were of Healthy Living (HL) sessions and 64% were of the first educational session. Among the observed sessions, 17 (68%) had 3 dyads present, 7 (28%) had 2 dyads and 1 (4%) had 4 dyads. Out of the 18 LHWs, 13 (72%) had one of their educational sessions observed, 4 (22%) had one first and one second session observed and 1 (6%) had 4 (two first and two second) sessions observed. The LHWs who had multiple sessions observed were observed by the same team member across sessions. Because the first and second sessions covered different material, observation notes captured the differences in content shared and questions asked. There was some variation in detail across observers’ notes, but all covered the basic descriptions requested in the structured observation form: session setting and physical space, LHW and participants and LHW/participant interactions.

In the following, we highlight aspects of LHW preparation, facilitation strategies and cultural communication practices observed as examples of how LHWs delivered the experimental (Smoking Cessation) and control (Healthy Living) intervention materials and the challenges they encountered.

LHW process: preparation

About 44% of sessions took place in homes of LHWs, 36% at the home of the CBO coordinator, 2 at a participant’s home and 3 in a CBO office. Holding sessions in homes helped to create a warm and comfortable atmosphere. LHWs served food and refreshments, arranged the physical space so that all participants could easily view the flip chart and, if participants knew each other prior to the meeting, spent time in casual conversation prior to beginning the session.

Observation notes from LHW sessions recorded examples of LHWs making ‘dessert and fruit for everyone’, arriving early and staying late and introducing the research staff ‘twice to be sure everyone knew who we were’. Other notations relevant to preparation include style of dress (professional), ensuring everyone could see the materials being presented and assisting movement if necessary and setting and respecting ground rules.

Because the Healthy Living (HL) sessions addressed nutrition and physical activity, at times participants expressed concern about the food that was offered in the session. For example, in one meeting the LHW noticed that participants seemed hesitant to try the dip she had offered. Some present voiced concern about the fat content in cheese. She assured them that it was fat-free cheese and that her husband had prepared the dip himself. In response, participants eagerly tried the dip and expressed appreciation for the care involved in serving a homemade snack.

Several sessions took place in an office or community space, which was difficult for the LHW to control and sometimes undermined his/her ability to keep the participants focused on the topic at hand. These spaces posed challenges for organizing chairs so that all participants could see the flip chart, resulting in those out of view engaging with their phones rather than the material presented. Another challenge was noise level. When held in an office on a busy street, traffic noise was disruptive. Thus, while LHWs generally worked to create a comfortable environment in which to share health information, jokes and stories, at times the context in which the sessions took place created challenges that were almost impossible to overcome.

Cultivating a friendly and supportive environment

Unlike many LHW programs, LHWs in this study worked closely with participating CBOs and reached beyond their own circles to recruit participants at supermarkets and other community settings. We highlight this because much of the literature suggests that LHWs are effective due to their personal connections to participants. In our study, at times there was little familiarity prior to the gathering between the LHW and participants and between participants themselves. In these cases, most prominent in the first session, the LHW had to work to create an atmosphere of comfortable conversation and sharing. At times, the LHW had a social connection to one or more of the participants, but not the others. One LHW, for example, recruited participants from the agency where she worked with recently arrived Vietnamese immigrants. The level of familiarity became evident in the forms of communication (e.g. asking about each other’s families) and the linguistic forms of address selected. Examples were recorded in field notes:

All the participants knew each other really well and they all seemed to know the LHW well, which is evident by the way they talked about her house and family. The atmosphere was lively and everyone was friendly towards one another (HL_Session 1_LHW_F)

The LHW was very excited to meet his participants, hugging and patting everyone and asking how their day was. It seemed like the LHW was close to each of the couples and the couples themselves were also close with each other as indicated by their actions before the session began. When I [observer] arrived, there were already some pastries on the table and bottled water for everyone. And for the break he brought out food made by his wife. Overall, he was prepared to make everyone feel welcome in his home. (HL_Session1_LHW_M)

LHWs used communication and facilitation skills to transform initial formal interactions into more comfortable and familiar ones by the end of the session. For example, in a session in which the following was recorded at the beginning, ‘None of the participants spoke to the LHW at the table. While he was reviewing his presentation, the participants did not seem to be familiar with him, nor were they familiar with each other’ (SC_Session 1_LHW_M), the LHW successfully turned things around by encouraging participants to ask questions and engage with each other. Before the session, he asked for permission to address participants either as ‘Anh’ or ‘Chi’, which in Vietnamese means ‘brother’ or ‘sister’, forms of respectful address. This is particularly noteworthy due to his age status (in his late 70's); these forms of address equalize status among participants of different ages. He also asked everyone to introduce themselves and assured that they could all see the flip chart. Throughout the session, he listened carefully to everyone’s opinions and did not push anyone for answers. He stopped often during his presentation to ask participants for their thoughts.

When this LHW asked participants whether money, health or relationship was the most important, one participant responded that all three were and another responded, ‘smoking is also important. When you smoke with your co-workers, you are building relationships at work. These connections will then help you make money to care for your family’. In response, the wife of one of the smokers noted that this may have been the case in Vietnam, ‘but in America people don’t do that’. A third participant commented, ‘I understand the consequences of smoking, but I think that smoking is also a way of greeting, a way to make friends. If others are smoking and we refuse, then it would seem impolite’. In response to the LHW’s question ‘Why do we smoke?’ (note, the use of ‘we’ rather than ‘you’), one participant responded, ‘Every time I’m sad, I’ll smoke’. Another added,

I’ve been smoking since I was 10. I didn’t know how to smoke, so my brother invited me to try it. The first time I tried it, I choked. Since we lived on a farm [in Vietnam] it would often get cold. Whenever I smoked, I felt warm. Eventually it became a habit. Other people would try to wean off, or they would chew nicotine gum. For me, I do it cold turkey. I’ve stopped many times, every 2–3 years, but then I feel sad sometimes and start smoking again (SC_Session 1_LHW_M).

The supportive environment cultivated during the session also encouraged humor in the conversations among the participants. For example, in response to the question posed by a participant about how long it takes to smoke a cigar, another participant (not the LHW) answered, ‘It takes 5 minutes to smoke a cigar and another 5 minutes to argue with one’s wife’, which made everyone laugh.

As this example highlights, field notes recorded the transformation of stilted or somewhat restrained settings into comfortable sites for conversation and sharing about families, children and experiences in Vietnam by the end of the session.

Presentation styles and strategies

Our observations highlighted variation in LHW presentation styles. Some LHWs followed the flipcharts closely, covering the material in a didactic lecture-like manner. Others were more conversational in their approach and interspersed information from the flip chart with personal stories or questions. Some encouraged dialogue and used humor to communicate points, while others limited the conversation to the information in the flip chart.

A technique we observed was the use of real-life examples in response to participants’ questions. LHWs also used these examples to steer the conversations back to key learning points. For example, one of the participants in a first HL session jokingly said, ‘I know you have to cut down [on the amount of food] but what about bun bo hue (a popular Vietnamese soup with beef and rice vermicelli)? Of course we need to eat an entire bowl of that!’ Everyone laughed in response. The LHW steered the conversation back toward healthy eating by saying ‘Bun bo hoe is very good but you can definitely make it healthier by adding more vegetables!’ (HL_Session1_LHW_F).

LHWs also used tangible examples to clarify challenging information. In a HL session focused on teaching participants how to read nutrition labels, a LHW went beyond pointing to examples on the flip chart to walk over to her kitchen cabinet, pull out a can of food and show the participants where to look for each category. She showed them where ‘total fat’ content is printed in bold on the label.

LHWs asked questions of individual participants related to the content. For example, at the first SC session, LHWs asked ‘How old were you when you started smoking?’ The question spurred discussion, supported ongoing conversation among participants and acknowledged efforts each was making to achieve the goals they had elaborated on their Family Action Plan. One LHW asked participants to speak about the difficulty of quitting smoking at the beginning of the session. This set a tone for dialogue and sharing. Another asked participants about the triggers or reasons that they smoke.

In a second SC session, a LHW asked what participants had done since completing the ‘Healthy Family Action Plan’. One participant reported talking to his family about it and that his wife who was visiting Vietnam kept calling him on the phone to convince him to quit smoking. Another reported calling the quitline unsuccessfully. He tried it two or three times and only received an answer in English. Another participant, a father going through the intervention to support his son’s quitting smoking, said that he had called for his son, reached the Vietnamese line and they offered to send him nicotine patches and free information. He then encouraged others to call, noting that it is open until 9 pm. The LHW then offered to help the participant who had had trouble reaching the Vietnamese language line complete the call after the session.

This LHW used skillfully placed questions to support dialogue and exploration of challenges to quitting smoking, which encouraged conversation among participants, both within and outside of a family dyad in the session. For example, when the Father mentioned above said he didn’t like the smell of smoking and that ‘I don’t get why people say smoking helps them concentrate. To me, the smell is really distracting’. The LHW responded by asking, ‘Then why do you think people smoke?’ A wife of one of the smokers replied, ‘Because once you decide to try it, it is addicting’. Her husband continued, ‘People smoke to socialize. You smoke because there are certain moments when you need to take a break and think about what to say next. Smoking helps with that’. To this, the LHW asked another question, ‘What does everyone think about this statement?’ When a smoker participant said he agreed, the LHW responded with, ‘Yes, but remember that health is still more important’ (SC_Session2_LHW_F).

In this same SC session, the LHW was faced with the difficult topic of the deleterious effects of quitting smoking. A participant suggested that quitting tobacco causes people to gain weight and die. Another participant responded, ‘I know someone who quit right away and the sudden nicotine craving killed him’. The LHW probed the speaker for more information about this case, suggesting that he may have died from smoking related complications, rather than from quitting. Another participant responded, ‘I’ve also heard about other people dying because they quit’. The LHW answered by saying, ‘I had a healthy brother who died from a stroke. It was unexpected and came out of nowhere. You can’t really say that quitting caused his death. Before you make those claims, you need to confirm it with the doctor because untrue claims can be harmful to people who are smoking but need to quit’ (SC_Session2_LHW_F).

Verbal and non-verbal communication

We observed linguistic and nonverbal techniques LHWs used to communicate warmth and respect. This was especially important when the LHW was younger than the other participants. Nonverbal strategies included hand gestures and facial expressions. One LHW smiled often and made use of hand gestures to engage the participants. She made sure to pause and ask if participants had any questions and made sure everyone participated. Seeing that only four of the participants had spoken through the session, she politely invited the last two (mother and son) to share their thoughts. This motivated the woman to open up about wanting her son (smoker) to exercise more.

Verbal expressions included linguistically appropriate terms of address, firmness of tone and gentle form of speaking. One LHW was noted as having a firm and professional tone of voice; making sure everyone was together and on the same page; asking at the beginning if everyone could see the flipchart and looking around at the group and pointing when turning the pages. He gave clear instructions on what to do (HL_Session1_LHW_M). Another LHW spoke with a loud and clear voice. She stood the entire session so her voice projected. She also repeated important phrases to get the participants to pay close attention (SC_Session2_LHW_F). A participant commented on the soothing effect of the LHW’s voice at the close of the session, stating, ‘The good thing is that you have a way of making things easier for me to understand and that makes us want to quit right away. Your voice is also gentle and calming. Whenever I speak with my doctor he wants me to quit too, but he does not speak gently’ (SC_Session2_LHW_F)

LHW experience/expertise

Because our research team has conducted a number of LHW interventions on other health topics with the Vietnamese community (Mock et al., 2007; Nguyen et al., 2009, 2015), we were able to draw upon a pool of experienced LHWs. In the course of the study, the value of this experience when compared with newer LHWs who were less sure of their abilities to explain the research project and the specific content of the flip chart to participants became clear. Less experienced LHWs tended to approach the sessions in a more didactic, less dialogic manner. While they also prepared food for participants and worked to communicate information contained in the flip chart, they communicated insecurity through avoidance of eye contact and ‘sticking to the script’ rather than interspersing personal stories to elaborate points. At the beginning of the presentation in her first session, a young LHW, for example, spoke very quickly, stumbled over her words and had to pause to find her place again. She interrupted her presentation to return to a previous page of the flip chart to check to see if she had missed anything. She asked participants to let her know if she was going through the material too quickly, but no one did so.

Gender and age also impacted LHWs performance. All LHWs followed the cultural pattern of showing respect to those with authority and high social position. Age was also an important moderator of interactions. The LHWs were attentive to this and ensured that everyone was treated with respect by addressing everyone using proper pronouns, for example Co and Chu (Aunt and Uncle) if the LHW was much younger, or Anh and Chi (Brother and Sister). Importantly, one LHW, much older than the participants in the session, used these linguistic norms to encourage participation. Like the LHW mentioned above, she addressed everyone with ‘Chi and Anh’ which is usually used to refer to someone who is a few years older. By doing this, the LHW gave the participants more power, even though they were younger, to encourage them to share their opinions (SC_Session2_LHW_F).

CONCLUSIONS

Prior studies have supported the effectiveness of the use of LHWs as an intervention model for managing chronic health conditions such as diabetes, hypertension, cardiovascular diseases and changing health behaviors such as adopting cancer screening and increasing medical adherence, yet few have documented the mechanisms that underlie the effectiveness of the interventions (Glenton et al., 2013; Kim et al., 2016). This is the first study, to our knowledge, using field notes of live observations of LHW-led education group sessions to document how LHWs deliver the targeted health messages to promote smoking cessation, healthy eating and physical activity among Vietnamese American families.

Our findings are consistent with previous research (South et al., 2013) that LHWs act as cultural bridges, using their language skills and cultural insights to connect with the socially excluded or those who otherwise experience barriers to accessing professional expertise/health care. The training LHWs underwent as a part of this study intentionally left latitude for them to conduct the educational sessions in the manner they were most comfortable with/that they thought would be most effective, trusting that they would use an approach that would be culturally and socially appropriate.

The ‘how’s’ that this study revealed were the processes of preparation, cultivating a friendly and inclusive social environment, using a combination of presentation strategies to deliver health messages that were personally relevant and memorable, engaging participants via warm and respectful verbal and non-verbal communication and drawing from the LHWs’ own expertise and prior experience to facilitate comprehension and application of knowledge to action. There were no meaningful differences in observations across the two groups, other than the fact that members of the healthy living group sometimes brought up questions about smoking. As noted in Table 1, these ‘how’s’ are well aligned with some of the skills recommended for CHWs by the American Public Health Association.

There are limitations of the current study as these findings are based on a family-based intervention that involved both male daily smokers and their non-smoking predominantly female family members from the Vietnamese American community. Thus, the interactions observed might not be generalizable to other contexts and might not be generalizable outside of Vietnamese American community. Further, findings are drawn from observation fieldnotes made by individual observers. While observers were trained to follow a structured observation guide, there are unavoidable individual perspectives and subjectivity in selecting and in reporting the elements.

Our study offers a first detailed look at the ‘black box’ of how LHWs work with their participants to deliver health messages. LHWs use a range of relational strategies to facilitate the delivery of health information to their participants. These strategies include preparing an environment that enables relationship building, using recognized teaching methods such as engaging the learner and co-learners as well as using humor and employing culturally specific strategies such as using hierarchical forms of address to create trust. Further research is needed to assess if these relational methods lead to behavioral change among participants and if these skills can be taught, in order for the promise of LHWs as a low-cost, culturally-appropriate way to promote health among underserved and minority populations to be fulfilled. In our future research, we plan to triangulate observational data with behavioral outcomes measured in our follow-up survey to assess effectiveness of the LHW techniques. Specifically, we will identify sessions in which particular techniques are evident (e.g. use of personally relevant and memorable presentation strategies) and link participant outcome data (e.g. reported calls to the Vietnamese quit line or NRT use) to session participants. Linking LHW techniques with behavioral outcomes in this way will enable identification of particularly effective techniques that can be cultivated and taught, thus enhancing the potential of LHW interventions.

FUNDING

This research was supported by the Tobacco-Related Disease Research Program (22RT-0089H). Additional support was provided by the National Institute on Drug Abuse (R01DA036749).

ETHICS STATEMENT

The University of California San Francisco Institutional Review Board approved all study procedures. Lay health workers (LHW) and their participants provided written consent for the possibility of being observed prior to participation in the study. In addition, at the beginning of each observed session, we requested verbal consent from both the LHW and each participant to observe the session and to take photographs.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

The authors wish to express their gratitude to the project lay health workers, the study participants, partnering agencies and their project coordinators (Anita Kearns at Vietnamese Voluntary Foundation—VIVO and Mai Pham at Immigrant Resettlement & Cultural Center—IRCC).

REFERENCES

- ATLAS.ti Scientific Software Development GmbH, Berlin (2013) Atlas.ti 7 (Version 7.1). Berlin: Atlas.ti. [Google Scholar]

- Bernard H. R. (2010) Research Methods in Anthropology: Approaches. Lanham, MD: Altamira Press. [Google Scholar]

- Burke N. J., Jackson J. C., Thai H. C., Lam D. H., Chan N., Acorda E., et al. (2004a) ‘Good health for new years’: development of a cervical cancer control outreach program for Vietnamese immigrants. Journal of Cancer Education: The Official Journal of the American Association for Cancer Education ,19, 244–250. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Burke N. J., Jackson J. C., Thai H. C., Stackhouse F., Nguyen T., Chen A., et al. (2004b) ‘Honoring tradition, accepting new ways’: development of a hepatitis B control intervention for Vietnamese immigrants. Ethnicity & Health ,9, 153–169. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Byrd T. L., Wilson K. M., Smith J. L., Coronado G., Vernon S. W., Fernandez-Esquer M. E., et al. (2013) AMIGAS: a multicity, multicomponent cervical cancer prevention trial among Mexican American women. Cancer ,119, 1365–1372. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- C3 Project (2013) The Community Health Worker Core Consensus (C3) Project: 2016 Recommendations on CHW roles, skills and qualities. Retrieved from https://sph.uth.edu/dotAsset/55d79410–46d3–4988-a0c2–94876da1e08d.pdf (last accessed 6 October 2018). [Google Scholar]

- Charmaz K. (2006) Constructing Grounded Theory: A Practical Guide through Qualitative Analysis ,1st edition, SAGE Publications Ltd, Thousand Oaks, CA. [Google Scholar]

- deRosset L., Mullenix A., Flores A., Mattia-Dewey D., Mai C. T. (2014) Promotora de salud: promoting folic acid use among Hispanic women. Journal of Women’s Health, 23, 525–531. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fernandez M. E., Savas L. S., Lipizzi E., Smith J. S., Vernon S. W. (2014) Cervical cancer control for Hispanic women in Texas: strategies from research and practice. Gynecologic Oncology ,132, S26–S32. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fetterman D. M. (1997). Ethnography: Step-by-Step, Applied Social Research Methods Series, 2nd edition, Vol. 17, Sage Publications Inc, Thousand Oaks, CA. [Google Scholar]

- Finlayson T. L., Asgari P., Hoffman L., Palomo-Zerfas A., Gonzalez M., Stamm N., et al. (2017) Formative research: using a community-based participatory research approach to develop an oral health intervention for migrant Mexican families. Health Promotion Practice ,18, 454–465. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Glenton C., Colvin C. J., Carlsen B., Swartz A., Lewin S., Noyes J., et al. (2013) Barriers and facilitators to the implementation of lay health worker programmes to improve access to maternal and child health: qualitative evidence synthesis. Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews , (10), CD010414. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Glenton C., Lewin S., Scheel I. B. (2011) Still too little qualitative research to shed light on results from reviews of effectiveness trials: a case study of a Cochrane review on the use of lay health workers. Implementation Science: IS, 6, 53. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Han H.-R., Lee H., Kim M. T., Kim K. B. (2008) Tailored lay health worker intervention improves breast cancer screening outcomes in non-adherent Korean-American women. Health Education Research ,24, 318–329. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hou S.-I., Sealy D.-A., Kabiru C. W. (2011) Closing the disparity gap: cancer screening interventions among Asians–a systematic literature review. Asian Pacific Journal of Cancer Prevention: APJCP ,12, 3133–3139. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hsu L. L., Green N. S., Donnell Ivy E., Neunert C. E., Smaldone A., Johnson S., et al. (2016) Community health workers as support for sickle cell care. American Journal of Preventive Medicine ,51, S87–S98. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hunter J. B., de Zapien J. G., Papenfuss M., Fernandez M. L., Meister J., Giuliano A. R. (2004) The impact of a promotora on increasing routine chronic disease prevention among women aged 40 and older at the U.S.-Mexico border. Health Education & Behavior ,31(Suppl. 4), 18S–28S. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Juon H.-S., Strong C., Kim F., Park E., Lee S. (2016) Lay health worker intervention improved compliance with hepatitis B vaccination in Asian Americans: randomized controlled trial. PloS One ,11, e0162683. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kim K., Choi J. S., Choi E., Nieman C. L., Joo J. H., Lin F. R., et al. (2016) Effects of community-based health worker interventions to improve chronic disease management and care among vulnerable populations: a systematic review. American Journal of Public Health ,106, e3–e28. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lewin S. A., Dick J., Pond P., Zwarenstein M., Aja G., van Wyk B., et al. (2005) Lay health workers in primary and community health care. The Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews , (1), CD004015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mock J., McPhee S. J., Nguyen T., Wong C., Doan H., Lai K. Q., et al. (2007) Effective lay health worker outreach and media-based education for promoting cervical cancer screening among Vietnamese American women. American Journal of Public Health ,97, 1693–1700. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mock J., Nguyen T., Nguyen K. H., Bui-Tong N., McPhee S. J. (2006) Processes and capacity-building benefits of lay health worker outreach focused on preventing cervical cancer among Vietnamese. Health Promotion Practice ,7, 223S–232S. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Molokwu J., Penaranda E., Flores S., Shokar N. K. (2016) Evaluation of the effect of a promotora-led educational intervention on cervical cancer and human papillomavirus knowledge among predominantly Hispanic primary care patients on the US-Mexico border. Journal of Cancer Education: The Official Journal of the American Association for Cancer Education ,31, 742–748. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Navarro A. M., Senn K. L., McNicholas L. J., Kaplan R. M., Roppé B., Campo M. C. (1998) Por La Vida model intervention enhances use of cancer screening tests among Latinas. American Journal of Preventive Medicine ,15, 32–41. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nemcek M. A., Sabatier R. (2003) State of evaluation: community health workers. Public Health Nursing (Boston, Mass.) ,20, 260–270. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nguyen B. H., Luong N. T., Lehr K. T., Marlow E., Vuong Q. N. (2016) Community participation in health disparity intervention research in Vietnamese American community. Progress in Community Health Partnerships: Research, Education and Action ,10, 207–215. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nguyen B. H., Stewart S. L., Nguyen T. T., Bui-Tong N., McPhee S. J. (2015) Effectiveness of lay health worker outreach in reducing disparities in colorectal cancer screening in Vietnamese Americans. American Journal of Public Health ,105, 2083–2089. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nguyen T. T., Le G., Nguyen T., Le K., Lai K., Gildengorin G., et al. (2009) Breast cancer screening among Vietnamese Americans. A randomized controlled trial of lay health worker outreach. American Journal of Preventive Medicine ,37, 306–313. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pasick R. J., Barker J. C., Otero-Sabogal R., Burke N. J., Joseph G., Guerra C. (2009) Intention, subjective norms and cancer screening in the context of relational culture. Health Education & Behavior: The Official Publication of the Society for Public Health Education ,36, 91S–110S. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Patel V., Weiss H. A., Chowdhary N., Naik S., Pednekar S., Chatterjee S., et al. (2011) Lay health worker led intervention for depressive and anxiety disorders in India: impact on clinical and disability outcomes over 12 months. The British Journal of Psychiatry: The Journal of Mental Science ,199, 459–466. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pérez L. M., Martinez J. (2008) Community health workers: social justice and policy advocates for community health and well-being. American Journal of Public Health ,98, 11–14. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Puchalski Ritchie L. M., van L., Makwakwa M., Chan A., Hamid A. K., Kawonga J. S., H., et al. (2016) The impact of a knowledge translation intervention employing educational outreach and a point-of-care reminder tool vs standard lay health worker training on tuberculosis treatment completion rates: study protocol for a cluster randomized controlled trial. Trials ,17, 439. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rodney M., Clasen C., Goldman G., Markert R., Deane D. (1998) Three evaluation methods of a community health advocate program. Journal of Community Health ,23, 371–381. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rosenthal E. L., Brownstein J. N., Rush C. H., Hirsch G. R., Willaert A. M., Scott J. R., et al. (2010) Community health workers: part of the solution. Health Affairs (Project Hope) ,29, 1338–1342. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- South J., White J., Branney P., Kinsella K. (2013) Public health skills for a lay workforce: findings on skills and attributes from a qualitative study of lay health worker roles. Public Health ,127, 419–426. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Taylor V. M., Hislop T. G., Tu S.-P., Teh C., Acorda E., Yip M.-P., et al. (2009) Evaluation of a hepatitis B lay health worker intervention for Chinese Americans and Canadians. Journal of Community Health ,34, 165–172. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Taylor V. M., Jackson J. C., Yasui Y., Nguyen T. T., Woodall E., Acorda E., et al. (2010) Evaluation of a cervical cancer control intervention using lay health workers for Vietnamese American women. American Journal of Public Health ,100, 1924–1929. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tsoh J. Y., Burke N. J., Gildengorin G., Wong C., Le K., Nguyen A., Chan J. L., Sun A., McPhee S. J., Nguyen T. T. (2015) A social network family-focused intervention to promote smoking cessation in Chinese and Vietnamese American male smokers: A feasibility study. Nicotine, Tobacco, & Research, Tobacco Related Health Disparities Special Theme Issue ,17, 1029–1038. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Viramontes O., Swendeman D., Moreno G. (2017) Efficacy of behavioral interventions on biological outcomes for cardiovascular disease risk reduction among Latinos: a review of the literature. Journal of Racial and Ethnic Health Disparities ,4, 418–424. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zuvekas A., Nolan L., Tumaylle C., Griffin L. (1999) Impact of community health workers on access, use of services and patient knowledge and behavior. The Journal of Ambulatory Care Management ,22, 33–44. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]