Significance

Understanding the factors that influence social capital formation is of great interest to social scientists and policy makers. In this paper, we make two contributions to our understanding of its origins. First, using a series of historical and contemporary measures of social capital, we show that early investments in state capacity, as measured by the spatial expansion of the federal postal network in the United States, strongly predicts higher contemporary levels of social capital. Second, we show the existence of an important informational channel through which early investments in state capacity persisted. Namely, the spread of the postal network strongly predicts the location of local newspapers. These findings indicate that the recent declines in local newspapers may harm social capital.

Keywords: social capital, state capacity, long-run legacies, transmission mechanisms, local newspapers

Abstract

Social capital has been shown to positively influence a multitude of economic, political, and social outcomes. Yet the factors that affect long-run social capital formation remain poorly understood. Recent evidence suggests that early state formation, especially investments in state capacity, are positively associated with higher levels of contemporary social capital and other prosocial attitudes. The channels by which early state capacity leads to greater social capital over time are even less understood. We contribute to both questions using the spatial and temporal expansion of the US postal network during the 19th century. We first show that county-level variation in post office density is highly correlated with a bevy of historical and contemporary indicators of social capital (e.g., associational memberships, civic participation, health, and crime). This finding holds even when controlling for historical measures of development and contemporary measures of income, inequality, poverty, education, and race. Second, we provide evidence of an informational mechanism by which this early investment in infrastructural capacity affected long-run social capital formation. Namely, we demonstrate that the expansion of the postal network in the 19th century strongly predicts the historical and contemporary location of local newspapers, which were the primary mode of impersonal information transmission during this period. Our evidence sheds light on the role of the state in both the origins of social capital and the channels by which it persists. Our findings also suggest that the consequences of the ongoing decline in local newspapers will negatively affect social capital.

Since coming to prominence roughly three decades ago (1, 2), the consequences of social capital have received an enormous amount of scholarly attention. It is widely theorized that social capital helps groups overcome collective action problems in the production of collective goods (3, 4). Using both cross-national and within-country evidence, higher levels of social capital are associated with faster economic growth (5), greater economic (6) and financial (7) development, better health outcomes (8), less property crime (9) and fewer homicides (10). Social capital has also been found to be important for political accountability (11), political participation (12), governance (13, 14), support for social insurance (15), and the functioning of democracy (2, 16).

Due to the multitude of channels through which social capital is shown to interact with many facets of economic, political, and social development, it is critical to better understand the factors influencing its origins and persistence. In this vein, recent work has shown that early investments in formal state capacity have long-run effects on prosocial attitudes and norms of cooperation (17, 18), propensity to follow rules and laws (19), and corruption (20). Yet the mechanisms by which these early investments affected initial social capital formation or the transmission channels by which long-ago formal capacity influenced contemporary levels of social capital remain a black box.

This study makes two contributions. First, we explore the role that early investments in infrastructural state capacity can play in developing higher social capital over the long run. Mann famously defined “infrastructural power” as the “institutional capacity of the state to actually penetrate civil society, and to implement logistically political decisions throughout the realm” (ref. 21, p. 189). We investigate this using the spatial location of US federal post offices during the 19th century as a proxy for spatial and temporal variation within the United States in early infrastructural capacity. Not only was the creation of the postal network the federal government’s primary state-building effort during the early postindependence period, historians and social scientists have argued that this investment substantially enhanced US public administrative capacities (22–24). The development “of the world’s most efficient postal service” is also seen as being critical for allowing “places far from the Eastern seaboard to become full participants in national life” (ref. 25, p. 541).

We begin by linking this investment in the postal network to the development of civic and religious associations over the 19th and early 20th centuries, the expansion of which has been identified as a key driver of early American political and social development (25–29). We then show, using a number of contemporary indicators of social capital, such as associational memberships, turnout, health, and crime, that the consequences of these early investments in the postal network on social capital persist to this day. This relationship remains strong even when controlling for a host of mediating factors, and subjecting our findings to numerous robustness checks. Thus, unlike previous studies using border discontinuity designs to show that areas within the boundaries of early states have higher social capital today (19, 20), we provide evidence, within the same border, that investments in formal capacity had an independent effect. Furthermore, our design goes further by identifying specific forms of state building that influenced long-run social capital formation.

Second, and perhaps more importantly, we offer direct evidence of a channel through which early infrastructural capacity affected long-run social capital formation. Namely, we show that post office expansion strongly predicts the location of newspapers over the 19th century, a relationship which we show persists for over a hundred years. Our evidence indicates that the federal government’s investment in the postal network was important for facilitating information transmission which sowed the seeds for social capital for decades, if not centuries, to come. At the same time, our findings suggest that the ongoing decline of local newspapers could have severe consequences on social capital.

Investments in State Capacity: The Postal Network

The impediments to long-distance communication in the large and sparsely populated colonial America were substantial, especially as one moved into the frontiers off the Atlantic coast. At the time of independence, there were 75 post offices, mostly in the country’s few coastal towns. With the passage of the Post Office Act of 1792, the federal government sought to create a rapid communication network that connected all of the country’s far-flung regions. The success of this program is staggering. Between 1790 and 1860, when the number of post offices reached nearly 29,000, post offices per 10,000 residents rose from 0.2 to 9.2. Furthermore, in 1841, postmasters not only outnumbered total military personnel but, alone, comprised nearly 80% of all civilian federal employees. Hence, it is unsurprising that, according to one historian, “for the vast majority of Americans the postal system was the central government” (ref. 23, p. 3).

The fledgling federal government’s investment in the postal network was critical for a few key reasons. For one, the approximately 4 million US residents in 1790 were thinly spread across thousands of miles, a space that would only grow larger with the country’s territorial expansion to the Pacific coast. Because mail was not delivered directly to residential addresses until late in the 19th century, spatial proximity to a post office was crucial to being connected to everyday economic and political life (23–25). As the primary mode of long-distance communication during most of this period, the postal network was also critical for increasing administrative capacity and facilitating routine collective action of federal and subnational public officials (23).

The explosive early expansion of the postal network provides an ideal setting to study the consequences of this investment. Since Congress’s primary goal was to connect the residents of the large and sparsely populated country, noneconomic factors dominated the choice of post office sitings in the first half of the 19th century (23, 24).* The often idiosyncratic choice for new routes even led President James Monroe (1817–1825) to remark on the many remote post offices in which “not a single letter is ever sent there, to any person but [the postmaster]” (quoted in ref. 23, p. 51). The rapid rate of growth in the early national period meant that communities faced few meaningful political impediments to receiving a post office. A Michigan congressman remarked, in the 1850s, that “in the 25 years he had been in Congress, not a single application for a new mail route had been denied” (quoted in ref. 23, p. 51).

Numerous intervening factors influenced spatial variation in the federal investment in the postal network. In particular, the Civil War affected the regional distribution in the growth of post offices. The victorious Northern states saw their proportion of new post offices rise markedly compared to the South.† Post office sitings also become more closely linked to federal politics in the postwar period (24). Yet, key to our argument, the underlying spatial structure of the postal network was largely established during this early period, as the overall rate of post office growth slowed significantly after 1850.‡

Scholars have increasingly exploited the federal government’s permissive and substantial early expansion of the postal network to study the consequences of this effort. Not only has post office density been shown to predict county-level economic development in the 19th century, but counties with greater post office density at the end of the 19th century have higher per capita income today (24). The spread of post offices over the 19th century has also been shown to predict the spatial location of patenting (22).

Research Design, Data, and Results

We first investigate how the growth of the postal network over the 19th century influenced social capital formation over the 19th and early 20th centuries. We then explore whether this relationship persists through to today. Data and code to replicate all models and results that follow are available at https://doi.org/10.7910/DVN/EPBPMJ.

Historical Post Office Data.

For our primary explanatory measure, we gather data on the number of post offices by county—the lowest administrative level at which most historical data are available—decennially, beginning with 1800 and proceeding to 1890. Following other scholars in this literature (22, 24), we operationalize our postal count variable by taking the natural logarithm of the number of county post offices (plus one, to deal with counties having zero post offices). All results hold if this variable is replaced with post offices per capita.

Historical Economic, Demographic, and Political Controls.

Given the concern that both the historical location of post office sitings and observed social capital could be due to various economic and political factors, we include the following controls in each of the analyses we conduct. We follow (24) and control for county population (logged), population density (i.e., population per square mile, also logged), percentage African American, percentage foreign born, and the per capita value of manufacturing output (30), each of which are measured in the same census decade as post offices. Since post office expansion in the post-Civil War period became more influenced by transportation networks and federal politics, we also control for the (logged) total county mileage of rail length, and the presidential and congressional vote shares received by the winning candidate and party, respectively, during the most recent national election (31).§

Historical Social Capital Data.

Due to the absence of other direct indicators of social capital, we focus on measuring historical associational development in the United States. This period, beginning just prior to the US Civil War through the early 20th century, roughly coincides with the so-called “Golden Age of Fraternity,” a time in which membership in civic associations of both religious and secular varieties was at its apogee (28). These institutions include churches, as well as fraternal organizations such as the Freemasons, Odd Fellows, the General Federation of Women’s Clubs, and the like (25, 27, 33). Beyond organizational memberships, this was also a time of great political engagement through associations. Citizens across the nation petitioned the government over a whole host of issues, ranging from slavery to the treatment of Native Americans to temperance, and so forth (26).

First, we measure church membership at several points in time during this period—1850, 1860, 1906, 1916, 1926, and 1936. The first two of these years’ data come from the decennial census (30), whereas the last four come from the (subsequently discontinued) US Census on religious affiliation (34). Each of these sources includes data on membership for virtually all active religious denominations.

As for nonreligious measures, we rely on data from Gamm and Putnam (27) on the number of Freemasons and Odd Fellows lodges, the number of women’s associations, and the overall level of associational membership for the period of 1900–1960. These data were carefully culled from city directories’ lists of associations and represent one of the best collections of such associational membership during the early 20th century. Additionally, we leverage Carpenter and Moore’s (26) comprehensive database of antislavery petition signatures between 1832 and 1845. These data measure the total number of signatures per population across petitions sent to Congress in opposition to slavery during this time frame. Foreshadowing our analysis on the mechanism of persistence between the postal network and social capital formation, we also include the number of local newspapers at the county level in 1840 as measured by the 1840 Census (30). For ease of comparison in what follows, each of these variables is measured per 1,000 county population. Finally, we also collect data on presidential turnout between 1824 and 1860, which we measure as a percentage of the adult white male population during each election. In the interest of space, we only report here the estimate for the election of 1860 (an extremely contentious and high-turnout election).¶

The Postal Network and Historical Social Capital Formation.

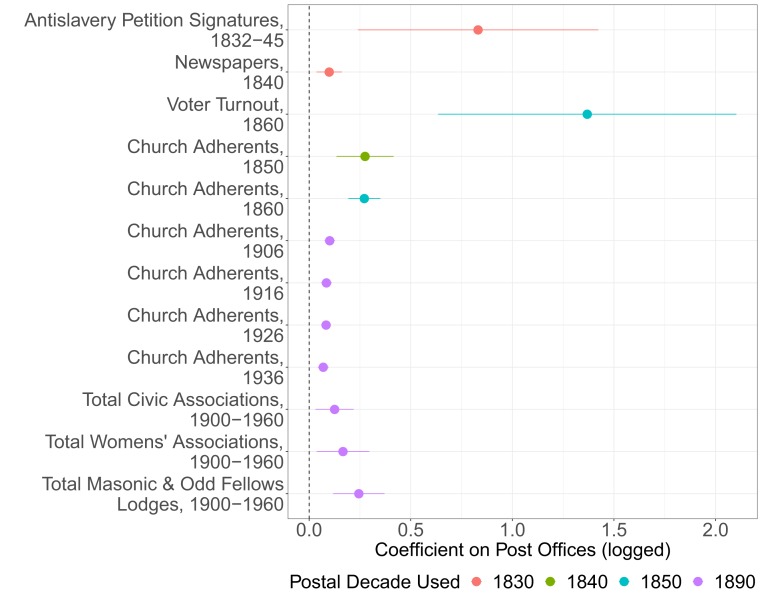

To analyze the influence of the postal network on early associational development, we run linear regressions of each of these outcomes on the logged number of post offices by county as well as the controls described previously. All models also include state fixed effects. In this and all subsequent figures, we focus on the coefficient on the variable of interest—here, logged post offices one decade or more prior to the time at which our various social capital outcomes are measured. The results from each model are depicted graphically in Fig. 1; 95% CIs are shown using horizontal line segments.

Fig. 1.

Growth of the postal network fostered early associational development. Dots and line segments are regression coefficients and CIs, respectively.

We see that the number of past post offices is significantly correlated to each outcome, even after accounting for various confounders. The substantive magnitudes of these estimates are also large. For instance, a 25% increase in the number of county-level post offices in 1830 is associated with about 2.07 more signatures per 1,000 persons; this would move a county from one of the least active (in terms of petitioning activity) to one of the most. In Fig. 1, we note that even outcomes fairly distant from the time period at which post offices are measured are still nonetheless significantly correlated. We address concerns of reverse causality in SI Appendix.#

Long-Run Influence on Social Capital.

We now examine the extent to which state capacity in the late 19th century—captured by the number of post offices by county as of 1890—is associated with contemporary levels of social capital. We continue to control for the previously described 1890 county-level demographic, economic, and geographic factors. In the analyses that follow, we refer to these controls as 1890 Covariates.

Contemporary Economic and Demographic Controls.

For our analyses of the long-run impacts of the late 19th-century postal network, we include a number of contemporary county-level controls which have been identified in the literature as important determinants of social capital. First, we include a county-level measure of income per capita in 2010 (35), as income has been shown to affect prosocial attitudes (36). Scholars have also shown that inequality negatively influences social capital (37). Thus, we include a county-level measure of the Gini coefficient (38). Scholars on the determinants of crime emphasize the influence of poverty (9). As such, we include the county-level poverty rate (38). We also include the proportion of adults with at least a college education (38), as scholars have also shown that more education increases civic capital and participation (39). Lastly, diversity and ethnic heterogeneity has been shown to undermine social capital and trust (40). We therefore include the share of each county’s population who are non-Hispanic white in 2010 (38).

Contemporary Social Capital Data.

We collect a number of indicators that capture various dimensions of contemporary social capital. For contemporary associational density, we employ data on the number of county social organizations, gathered by Rupasingha et al. (41). Civic Associations includes the number of religious institutions, the number of secular civic organizations, the number of bowling centers, the number of fitness and recreational sports centers, the number of golf courses and country clubs, and the number of sports teams and clubs. We also generate a composite number of organizations, which we call Social Organizations, that includes both the civic associations and the number of business, labor, and political organizations. In addition to both of these sorts of associations, we also examine the number of nonprofit organizations present in the county. We complement these data on associations with data on voter turnout in the 2012 presidential election, measured as the number of votes cast divided by the US Census’s estimate of the voting age population (41).

We also include outcomes, such as health, that are frequently found to be associated with higher social capital (8, 42). Specifically, we gather data on county-level mortality rates (43), premature mortality rates (44), and the percentage of adults without health insurance (45). The key distinction between these two measures of mortality is that the premature measure captures the average the number of years of life lost relative to what would be expected under normal, healthy conditions. As such, this variable captures deficiency in health outcomes as a result of a whole host of negative causes (e.g., the environment, smoking, and homicide).

Given extant linkages between crime and social capital (9, 10), we also use crime data (measured by county in 2010) from the Federal Bureau of Investigation (46). We focus on a number of key indicators, all measured as rates per 100,000 population: the drug arrest rate, the rape arrest rate, the murder arrest rate, and a composite measure of all three.

Last, continuing with our linking of post office density and newspapers, as well as following long-standing arguments about the decline of newspapers as either a product or cause of the decline in social capital (2, 47), we include the number of county-level daily local newspapers in 2000 (48).

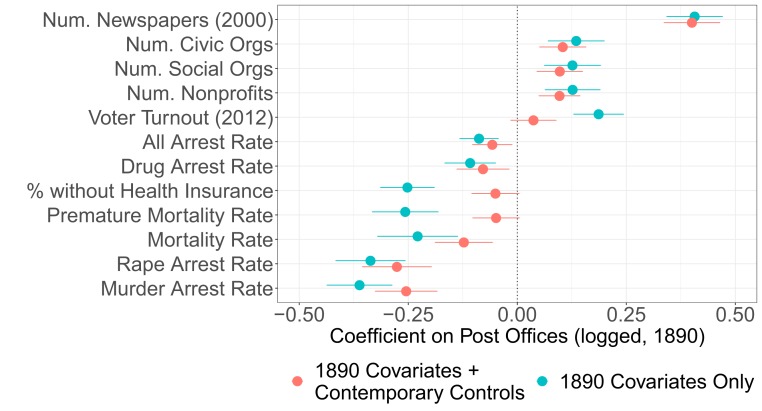

The Postal Network and Contemporary Social Capital.

For each of the contemporary outcomes listed above, we run linear regressions of these variables (all on a logged scale, save for voter turnout), first on just the 1890 Covariates and then including the contemporary controls (i.e., income per capita, percent of adults with at least a BA degree, poverty rate, Gini coefficient, and percent non-Hispanic white). Fig. 2 shows the coefficient on the logged number of post offices in 1890 on each of the outcomes, disaggregating by whether the model includes the 1890 controls or includes both 1890 and contemporary controls. We see that, regardless of the controls used, the number of post offices in 1890 has a strong, positive relationship to the various measures of social capital. More post offices in 1890 is positively associated with positive outcomes (more newspapers, more civic organizations, more social organizations, and more nonprofit organizations) and negatively associated with negative outcomes (fewer arrests of any type and lower mortality). The results, save a few exceptions, remain robust to the inclusion of a whole battery of historical and contemporary controls that should, in principle, explain nearly all of the variability across the various outcomes. These models, combined with those shown in Fig. 1, provide strong evidence that the early investments in the postal network set the seeds for social capital more than a hundred years later.∥

Fig. 2.

The number of post offices in 1890 predicts contemporary social capital. Dots and line segments are regression coefficients and CIs, respectively.

Mechanisms: Post Offices and Local Newspapers

While we have established that the development of the postal network influenced both historical and contemporary social capital formation, we have yet to provide evidence of a clear mechanism for why this should be the case. This persistence is puzzling given that the benefits of proximity to a post office declined in the 20th century with the implementation of direct delivery to all households across the country, as well as numerous advances in communication technologies. That said, we show, in Figs. 1 and 2, that the relationship between post offices in the 19th century and both the historical and contemporary incidence of local newspapers is strong. These findings are consistent with our contention that the basis for the long-run impacts of early state capacity on social capital derives, in part, from facilitating information transmission. Specifically, we argue that the establishment and expansion of the postal network over the 19th century was a key determinant in the spatial location of local newspapers.

Given that newspapers were the primary source of impersonal information transmission in this period, proximity to local newspapers could have affected social capital formation through a number of channels. For one, a local press is critical for informing voters and holding elected officials accountable (49). With greater accountability and therefore increasing quality of governance (e.g., less corruption and waste, more public goods), trust in formal institutions should rise (13, 50). Indeed, there is evidence that local newspaper entry between 1869 and 1928 is associated with reduced corruption (51) and increasing political participation (48). In addition to influencing prosocial attitudes, local access to newspapers should lower informational impediments to collective action and make it easier for groups to coordinate and organize (52). Newspapers were also a key vehicle for political party development in the 19th century (48). Further support for our claims about the importance of local newspapers is evident in the recent research on the consequences of the contemporary declines in local newspapers in the United States. These declines are associated with falling civic participation (53, 54), greater polarization (55, 56), and lower quality of governance (57, 58).

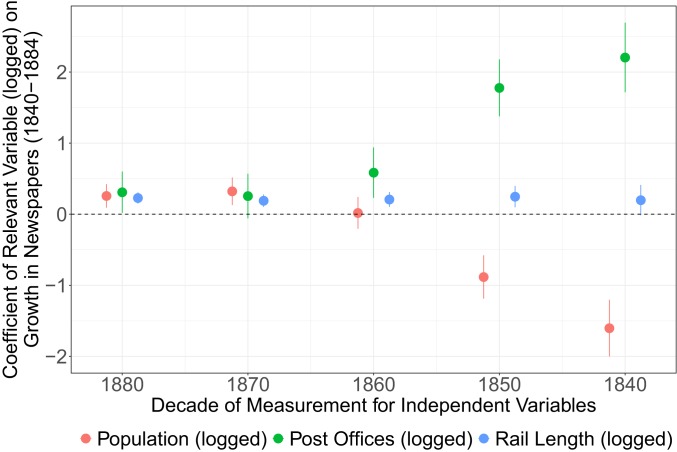

If our claims are correct, then the growth of the postal network should predict the growth in newspapers during the 19th century. We test this by investigating the influence of post offices on the change in county-level newspapers between 1840 and 1884.** We combine data from refs. 30 and 48 on the number of newspapers in 1840 and 1884, respectively, to construct a variable measuring the county-level change in the number of newspapers over this period.

We test our anticipatory hypothesis by running a series of regressions using this variable as the outcome of interest. In addition to our primary measure of post offices by county (plus one, logged), we also report the estimates for railway length (logged), and county population (logged). With the advent of the Railway Mail Service in 1864, the postal service became more reliant on the railway network (32). Population should also be a key predictor of the number of local newspapers. The results of these regressions are shown in Fig. 3. Across all models, the outcome is the same. In the first model, we use the number of post offices, rail length, and population in 1880 as the controls. For subsequent models, we lag each of these variables back by decade (i.e., using post office, railway mileage, and population counts in 1870, 1860, 1850, and 1840).

Fig. 3.

Early post offices predict subsequent growth in newspapers, 1840–1884. Dots and line segments are regression coefficients and CIs, respectively.

It is readily apparent from Fig. 3 that the importance of the number of post offices in predicting the growth in newspapers increases the farther back in time we lag. Surprisingly, the strongest relationship we observe is when we use the post office counts from 1840, thereby providing substantial evidence of the persistent nature of this relationship. In turn, this lends considerable support to our argument that the infrastructural investments in creating the postal network reduced communication costs, fostered greater information transmission, and, thereby, greatly impacted communities’ levels of social capital long thereafter.††

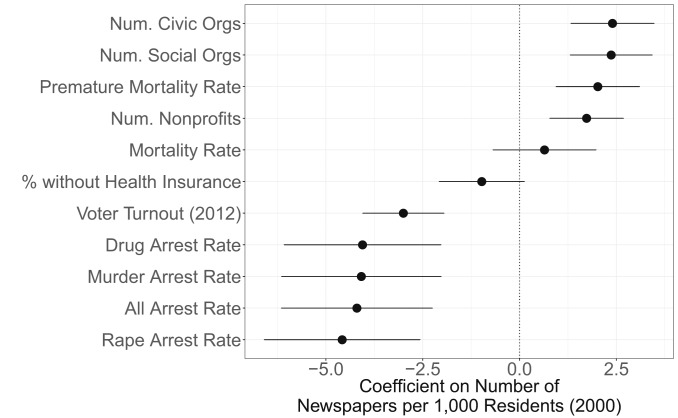

Decline in Local Newspapers and Social Capital.

We conclude by providing suggestive evidence that this historical relationship between local newspapers and social capital continues to this day. We do so by rerunning each model of the contemporary social capital outcomes from Fig. 2 but replacing the post office predictor with the number of newspapers per 1,000 inhabitants in the year 2000. The results are presented in Fig. 4. The estimates are largely consistent with our earlier findings. The number of newspapers is associated with higher associational density and lower crime. In SI Appendix, Fig. S8, we repeat this exercise, replacing newspapers in 2000 with 1) the number of newspapers in 1884 and 2) the change in the number of newspapers between 1884 and 2000, both measured per 1,000 inhabitants. The results are again largely unchanged. An implication of all of these findings is that the ongoing decline in local newspapers will have negative, if spatially uneven, consequences on social capital in the United States.

Fig. 4.

Newspapers in 2000 predict contemporary social capital. Dots and line segments are regression coefficients and CIs, respectively.

Discussion

The determinants of the spatial variation in American associational activity and social capital have long been of interest to scholars (2, 25–29, 33). Previous work has focused on factors such as electoral competition and the regionally differentiated effects of the Civil War as drivers of the spatial variation in associational development during the late 19th and early 20th century (33). We contribute to this literature by demonstrating the complementary role that the establishment of the US postal network had on the formation and persistence of higher levels of social capital. Using various measures of associational development between the 1830s and today, we find strong support that the expansion of the postal network predicts spatial variation in both short-term and long-term social capital.

Our arguments and findings speak to a number of additional literatures across the social sciences. First, we contribute to a growing literature investigating the importance of early investments in state capacity on long-run social capital (17, 18, 20). We also contribute to a rich literature on the importance of state capacity on long-run development (17, 24, 59, 60). While the correlations we report should not be interpreted as strictly causal, our study provides evidence of a key informational channel by which greater infrastructural capacity affects long-run outcomes. Namely, our evidence suggests that the expansion of the postal network significantly influenced the location of local newspapers. We theorize that this affected local social capital by facilitating information transmission. We support this claim by linking post office density through local newspapers to greater associational memberships from the early 19th century through to today. Our findings indicate that the type of state capacity building matters. That is, investments that encourage and facilitate citizen participation are more conducive to prosocial outcomes than forms of state capacity building that enable authoritarian rulers (e.g., strengthening the military bureaucracy).

Lastly, our work highlights the threat to social capital from the ongoing, long-run decline in the local newspaper industry. Our findings suggest that the consequences of this decline, especially if other sources of similar information do not replace newspapers’ vital role, will harm overall social capital.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

We thank Ron Rogowski, Cristian Pop-Eleches, and three anonymous reviewers for helpful feedback.

Footnotes

The authors declare no competing interest.

*Empirical support for this claim comes from Rogowski et al. (24), who find no evidence that economic growth predicts post office sitings in the 19th century.

†In SI Appendix, Table S1, we show that post office growth in the South stagnated after the war.

‡We provide evidence for this claim in SI Appendix. In SI Appendix, Fig. S2, we show that the growth in the number of post offices relative to population plateaued by the mid-19th century. In SI Appendix, Fig. S7, we correlate the number of post offices in each county, by decade, with its past values. The correlations over time are extremely stable, indicating that, while the network continued to grow, the overall spatial network structure was established early in the nation’s history.

§SI Appendix, Fig. S1 addresses concerns of causal ordering between the growth of railway and postal networks. Specifically, we show that post office network growth predicts railway growth (and not vice versa). This is consistent with Carpenter’s claim that, “Even with the rapid expansion of railway delivery routes into the nations rural interior, the structure of postal delivery before 1896 remained little altered from the antebellum postal network” (ref. 32, p. 138).

¶In SI Appendix, Fig. S4, we offer a more robust examination of turnout involving all elections between 1824 and 1860. The results are consistent with the estimate for 1860.

#We use the two prewar outcome variables measured as a panel—church adherents and voter turnout—to address concerns regarding the causal ordering of post office growth and social capital. In SI Appendix, Fig. S3, we use past post offices to predict subsequent church adherents, and vice versa. In SI Appendix, Fig. S4, we do the same procedure with voter turnout. We find robust support that a higher number of post offices predicts higher subsequent levels of church adherents and turnout.

∥SI Appendix contains a number of robustness checks. SI Appendix, Fig. S5 replaces 1890 post offices with a residualized measure thereof—namely, we predict post offices using rail length, county population, as well as presidential vote shares and calculate residuals, themselves measures of “abnormal” counts of post offices based on these structural factors. SI Appendix, Fig. S6 reruns the main models, replacing post offices in 1890 with the same measure from each decade between 1850 and 1880. The results, in all cases, remain largely unchanged. These results are unsurprising given the stability of the postal network, as shown in SI Appendix, Fig. S7.

**Our ability to investigate this in the pre-Civil War period is limited because systematic county-level newspaper data before 1869 is, to our knowledge, only available for 1840.

††Given the already mentioned concerns about the effects of increased patronage and the introduction of the Railway Mail Service following the Civil War, we rerun the models from this section in SI Appendix, replacing newspaper counts from 1884 with equivalent numbers from 1869. The results (SI Appendix, Table S2) match the estimates reported in Fig. 3.

This article is a PNAS Direct Submission.

Data deposition: Data and code to replicate all models and results that follow are available at https://doi.org/10.7910/DVN/EPBPMJ.

This article contains supporting information online at https://www.pnas.org/lookup/suppl/doi:10.1073/pnas.1919972117/-/DCSupplemental.

References

- 1.Coleman J. S., Social capital in the creation of human capital. Am. J. Sociol. 94, S95–S120 (1988). [Google Scholar]

- 2.Putnam R. D., et al. , Bowling Alone: The Collapse and Revival of American Community (Simon & Schuster, 2000). [Google Scholar]

- 3.Engbers T. A., Thompson M. F., Slaper T. F., Theory and measurement in social capital research. Soc. Indicat. Res. 132, 537–558 (2017). [Google Scholar]

- 4.Guiso L., Sapienza P., Zingales L., “Civic capital as the missing link” in Handbook of Social Economics (Elsevier, 2011) vol. 1, pp. 417–480. [Google Scholar]

- 5.Algan Y., Cahuc P., Inherited trust and growth. Am. Econ. Rev. 100, 2060–2092 (2010). [Google Scholar]

- 6.Tabellini G., Culture and institutions: Economic development in the regions of europe. J. Eur. Econ. Assoc. 8, 677–716 (2010). [Google Scholar]

- 7.Guiso L., Sapienza P., Zingales L., The role of social capital in financial development. Am. Econ. Rev. 94, 526–556 (2004). [Google Scholar]

- 8.Arezzo M. F., Giudici C., Social capital and self perceived health among European older adults. Soc. Indicat. Res. 130, 665–685 (2017). [Google Scholar]

- 9.Buonanno P., Montolio D., Vanin P., Does social capital reduce crime? J. Law Econ. 52, 145–170 (2009). [Google Scholar]

- 10.Robbins B., Pettinicchio D., Social capital, economic development, and homicide: A cross-national investigation. Soc. Indicat. Res. 105, 519–540 (2012). [Google Scholar]

- 11.Nannicini T., Stella A., Tabellini G., Troiano U., Social capital and political accountability. Am. Econ. J. Econ. Pol. 5, 222–250 (2013). [Google Scholar]

- 12.Inglehart R., Norris P., Rising Tide: Gender Equality and Cultural Change Around the World (Cambridge University Press, 2003). [Google Scholar]

- 13.Robbins B. G., Institutional quality and generalized trust: A nonrecursive causal model. Soc. Indicat. Res. 107, 235–258 (2012). [Google Scholar]

- 14.Putnam R. D., Leonardi R., Nanetti R. Y., Making Democracy Work: Civic Traditions in Modern Italy (Princeton University Press, 1993). [Google Scholar]

- 15.Daniele G., Geys B., Interpersonal trust and welfare state support. Eur. J. Polit. Econ. 39, 1–12 (2015). [Google Scholar]

- 16.Paxton P., Social capital and democracy: An interdependent relationship. Am. Socio. Rev. 39, 254–277 (2002). [Google Scholar]

- 17.Dell M., Lane N., Querubin P., The historical state, local collective action, and economic development in Vietnam. Econometrica 86, 2083–2121 (2018). [Google Scholar]

- 18.Guiso L., Sapienza P., Zingales L., Long-term persistence. J. Eur. Econ. Assoc. 14, 1401–1436 (2016). [Google Scholar]

- 19.Lowes S., Nunn N., Robinson J. A., Weigel J. L., The evolution of culture and institutions: Evidence from the Kuba Kingdom. Econometrica 85, 1065–1091 (2017). [Google Scholar]

- 20.Becker S. O., Boeckh K., Hainz C., Woessmann L., The empire is dead, long live the empire! Long-run persistence of trust and corruption in the bureaucracy. Econ. J. 126, 40–74 (2016). [Google Scholar]

- 21.Mann M., The autonomous power of the state: Its origins, mechanisms and results. Eur. J. Sociol. 25, 185–213 (1984). [Google Scholar]

- 22.Acemoglu D., Moscona J., Robinson J. A., State capacity and american technology: Evidence from the nineteenth century. Am. Econ. Rev. 106, 61–67 (2016). [Google Scholar]

- 23.John R. R., Spreading the News: The American Postal System from Franklin to Morse (Harvard University Press, 1995). [Google Scholar]

- 24.Rogowski J., Gerring J., Maguire M., Cojocaru L., State infrastructure and economic development: Evidence from postal systems. Am. J. Polit. Sci., in press. [Google Scholar]

- 25.Skocpol T., Ganz M., Munson Z., A nation of organizers: The institutional origins of civic voluntarism in the United States. Am. Polit. Sci. Rev. 94, 527–546 (2000). [Google Scholar]

- 26.Carpenter D., Moore C. D., When canvassers became activists: Antislavery petitioning and the political mobilization of American women. Am. Polit. Sci. Rev. 108, 479–498 (2014). [Google Scholar]

- 27.Gamm G., Putnam R. D., The growth of voluntary associations in America, 1840–1940. J. Interdiscip. Hist. 29, 511–557 (1999). [Google Scholar]

- 28.Kaufman J., For the Common Good?: American Civic Life and the Golden Age of Fraternity (Oxford University Press, 2003). [Google Scholar]

- 29.Skocpol T., Diminished Democracy: From Membership to Management in American Civic Life (University of Oklahoma Press, 2013), vol. 8. [Google Scholar]

- 30.Ruggles S., et al. , IPUMS USA: Version 9.0 [dataset] (IPUMS, Minneapolis, MN, 2019). [Google Scholar]

- 31.Atack J., Historical geographic information systems (GIS) database of U.S. Railroads for 1826–1890. https://cdn.vanderbilt.edu/vu-my/wp-content/uploads/sites/133/2019/04/14090344/RR1826-1911Modified0509161.zip. Accessed 1 February 2010.

- 32.Carpenter D. P., State building through reputation building: Coalitions of esteem and program innovation in the national postal system, 1883–1913. Stud. Am. Polit. Dev. 14, 121–155 (2000). [Google Scholar]

- 33.Crowley J. E., Skocpol T., The rush to organize: Explaining associational formation in the United States, 1860s-1920s. Am. J. Polit. Sci. 45, 813–829 (2001). [Google Scholar]

- 34.Department of Commerce and Labor, Bureau of the Census , Censuses of Religious Bodies, 1906-1936 (Bureau of the Census, Ann Arbor, MI, 1992). [Google Scholar]

- 35.US Bureau of Economic Analysis , “Personal income by county, metro, & other areas” (2018). https://apps.bea.gov/regional/histdata/releases/0412lapi/index.cfm. Accessed 2 November 2019.

- 36.Abascal M., Baldassarri D., Love thy neighbor? Ethnoracial diversity and trust reexamined. Am. J. Sociol. 121, 722–782 (2015). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Mikucka M., Sarracino F., Dubrow J. K., When does economic growth improve life satisfaction? Multilevel analysis of the roles of social trust and income inequality in 46 countries, 1981–2012. World Dev. 93, 447–459 (2017). [Google Scholar]

- 38.US Census Bureau , “American community survey, 2012-2016, 5-year estimates” (Tables B19083, DP03, DP02, DP05) (2017). https://data.census.gov. Accessed 13 October 2019.

- 39.Milligan K., Moretti E., Oreopoulos P., Does education improve citizenship? Evidence from the United States and the United Kingdom. J. Publ. Econ. 88, 1667–1695 (2004). [Google Scholar]

- 40.Dinesen P. T., Sønderskov K. M., Ethnic diversity and social trust: Evidence from the micro-context. Am. Socio. Rev. 80, 550–573 (2015). [Google Scholar]

- 41.Rupasingha A., Goetz S. J., Freshwater D., The production of social capital in US counties. J. Soc. Econ. 35, 83–101 (2006). [Google Scholar]

- 42.d’Hombres B., Rocco L., Suhrcke M., McKee M., Does social capital determine health? Evidence from eight transition countries. Health Econ. 19, 56–74 (2010). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.National Center for Health Statistics , “Compressed mortality file, 1999-2016” (CDROM Ser. 20, No. 2V, National Center for Health Statistics, Hyattsville, MD, 2017).

- 44.University of Wisconsin Population Health Institute , County Health Rankings (University of Wisconsin Population Health Institute, 2019). [Google Scholar]

- 45.US Census Bureau ; American Community Survey , “American Community Survey, 2012-2016, 5-year estimates” in Selected Characteristics of Health Insurance Coverage in the United States (US Census Bureau, 2017), Table S2701. [Google Scholar]

- 46.Federal Bureau of Investigation , “Uniform crime reporting program data: County-level detailed arrest and offense data, United States, 2014” (ICPSR 36399, Inter-university Consortium for Political and Social Research, 2017).

- 47.Shah V., Nojin Kwak R. L. H. D., “connecting” and” disconnecting” with civic life: Patterns of internet use and the production of social capital. Polit. Commun. 18, 141–162 (2001). [Google Scholar]

- 48.Gentzkow M., Shapiro J. M., Sinkinson M., The effect of newspaper entry and exit on electoral politics. Am. Econ. Rev. 101, 2980–3018 (2011). [Google Scholar]

- 49.Besley T., Principled Agents?: The Political Economy of Good Government (Oxford University Press, 2006). [Google Scholar]

- 50.Freitag M., Bühlmann M., Crafting trust: The role of political institutions in a comparative perspective. Comp. Polit. Stud. 42, 1537–1566 (2009). [Google Scholar]

- 51.Gentzkow M., Glaeser E. L., Goldin C., “The rise of the fourth estate. How newspapers became informative and why it mattered” in Corruption and Reform: Lessons from America’s Economic History (University of Chicago Press, 2006), pp. 187–230. [Google Scholar]

- 52.Chwe M. S. Y., Communication and coordination in social networks. Rev. Econ. Stud. 67, 1–16 (2000). [Google Scholar]

- 53.Shaker L., Dead newspapers and citizens civic engagement. Polit. Commun. 31, 131–148 (2014). [Google Scholar]

- 54.Hayes D., Lawless J. L., The decline of local news and its effects: New evidence from longitudinal data. J. Polit. 80, 332–336 (2018). [Google Scholar]

- 55.Darr J. P., Hitt M. P., Dunaway J. L., Newspaper closures polarize voting behavior. J. Commun. 68, 1007–1028 (2018). [Google Scholar]

- 56.Hetherington M. J., Rudolph T. J., Why Washington Won’t Work: Polarization, Political Trust, and the Governing Crisis (University of Chicago Press, 2015). [Google Scholar]

- 57.Gao P., Lee C., Murphy D., Financing dies in darkness? The impact of newspaper closures on public finance. J. Financ. Econ. 135, 445–467 (2019). [Google Scholar]

- 58.Snyder J. M. Jr, Strömberg D., Press coverage and political accountability. J. Polit. Econ. 118, 355–408 (2010). [Google Scholar]

- 59.Dincecco M., Katz G., State capacity and long-run economic performance. Econ. J. 126, 189–218 (2014). [Google Scholar]

- 60.Acemoglu D., Garcia-Jimeno C., Robinson J., State capacity and economic development: A network approach. Am. Econ. Rev. 105, 2364–2409 (2015). [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.