Abstract

OBJECTIVE.

Vascular Ehlers-Danlos syndrome (vEDS) is a rare disorder and one of 13 types of Ehlers-Danlos syndrome (EDS). The syndrome results in aortic and arterial aneurysms and dissections at a young age. Diagnosis is confirmed with molecular testing via skin biopsy or genetic testing for COL3A1 pathogenic variants. We describe a multi-institutional experience in the diagnosis of vEDS from 2000 to 2015.

METHODS.

This is a multi-institutional cross-sectional retrospective study of individuals with vEDS. The institutions were recruited through the Vascular Low Frequency Disease Consortium. Individuals were identified using the International Classification of Diseases (ICD)-9 and 10-CM codes for EDS (756.83 and Q79.6). Review of records was then performed to select individuals with vEDS. Data abstraction included demographics, family history, clinical features, major and minor diagnostic criteria, and molecular testing results. Individuals were classified into two cohorts and then compared: those with pathogenic COL3A1 variants and those diagnosed by clinical criteria alone without molecular confirmation.

RESULTS.

Eleven institutions identified 173 (35.3% male, 56.6% Caucasian) individuals with vEDS. Of those, 11 (9.8%) had non-pathogenic alterations in COL3A1 and were excluded from the analysis. Among the remaining individuals, 86 (47.7% male, 68% Caucasian, 48.8% positive family history) had pathogenic COL3A1 variants and 76 (19.7% male, 19.7% Caucasian, 43.4% positive family history) were diagnosed by clinical criteria alone without molecular confirmation. Compared to the cohort with pathogenic COL3A1 variants, the clinical diagnosis only cohort had a higher number of females (80.3% vs. 52.3%, P<.001), mitral valve prolapse (10.5% vs. 1.2%, P=.009), and joint hypermobility (68.4% vs. 40.7%, P<.001). Additionally, they had a lower frequency of easy bruising (23.7% vs. 64%, P<.001), thin translucent skin (17.1% vs. 48.8%, P<.001), intestinal perforation (3.9% vs. 16.3%, P=.01), spontaneous pneumo/hemothorax (3.9% vs. 14%, P.03), and arterial rupture (9.2% vs. 17.4%, P=.13). There were no differences in mortality or age of mortality between the two cohorts

CONCLUSIONS.

This study highlights the importance of confirming vEDS diagnosis by testing for pathogenic COL3A1 variants rather than relying on clinical diagnostic criteria alone given the high degree of overlap with other forms genetically triggered arteriopathies. As not all COL3A1 variants are pathogenic, interpretation of the genetic testing results by an individual trained in variant assessment is essential to confirm the diagnosis. Accurate diagnosis is critical and has serious implications for lifelong screening and treatment strategies for the affected individual and family members.

Keywords: Vascular Ehlers-Danlos Syndrome, COL3A1 mutation, Vascular genetic testing, Heritable arteriopathies

Table of Contents summary

In this multi institutional cross-sectional retrospective Vascular Low Frequency Disease Consortium study of 173 individuals diagnosed with vEDS based on clinical criteria, genetic testing for pathogenic COL3A1 variants was used to confirm the final diagnosis in 86 patients.

INTRODUCTION

The Ehlers-Danlos syndromes (EDS) are a group of 13 heritable connective tissue disorders generally characterized by joint hypermobility, skin hyperextensibility, and tissue fragility.1 Vascular Ehlers-Danlos syndrome (vEDS), previously called Ehlers-Danlos syndrome type IV, is one of the subtypes with an estimated frequency of 1/50,000and accounts for 5% of all EDS cases.2,3 The syndrome results from heterozygous mutations in the COL3A1, which encodes type III collagen.4 The effect of the pathogenic COL3A1 variants includes the production of defective type III collagen or the reduction in the quantity of type III collagen. The clinical manifestations include spontaneous arterial dissections, aneurysms, and rupture at a young age. Additionally, affected individuals are at increased risk for spontaneous intestinal perforation and pregnancy related uterine rupture.2,5,6 Consequently, individuals with vEDS have been reported to have average life expectancy less than 50 years with mortality usually related to arterial rupture or complications related to arterial repairs in these circumstances.2,7

Establishing the diagnosis in vEDS is challenging due to its rarity and heterogeneous clinical presentation.8,9 The diagnosis is suspected based on clinical findings and confirmed by molecular resting. Molecular testing includes biochemical testing via a skin biopsy and genetic testing for pathogenic COL3A1 variants (the latter is the predominant contemporary mode of diagnosis).1,2 We describe a multi-institutional experience in the diagnosis of vEDS and compare the demographics and clinical characteristics of individuals diagnosed using clinical diagnostic criteria only and those in whom the diagnosis was confirmed via molecular testing.

METHODS

This is a multi-institutional retrospective cohort study of individuals diagnosed with vEDS between January 1, 2000 and December 31, 2015. The institutions were recruited through the Vascular Low Frequency Disease Consortium (University of California-Los Angeles Division of Vascular Surgery).10 A call for participation to institutions was sent through electronic mail. Each participating center obtained Institutional Review Board (IRB) approval from their home institution. The IRBs waived the patient consent process due to minimal patient risk. Data were collected by each institution’s respective investigator(s), transmitted in a de-identified fashion to the University of Washington, and stored using a password-encrypted database maintained by the University of Washington.

Individuals were identified with International Classification of Diseases (ICD)-9-CM code 756.83 or ICD-10-CM code Q79.6 for EDS as coded in the electronic medical records. This diagnostic code includes vEDS and an additional 12 subtypes of EDS.1 Review of these case records was then performed to select individuals with vEDS based on the documentations in the medical records by providers caring for the patients. Individuals with the other 12 forms of EDS were excluded. Data regarding demographics, current age, age at diagnosis, family history (defined as a family history of vEDS, aortic or arterial aneurysms and dissections, and/or sudden death) were abstracted.

The major and minor clinical diagnostic criteria for the cohort were reviewed. The major diagnostic criteria for vEDS include arterial rupture, intestinal rupture, uterine rupture during pregnancy, and family history of vEDS.1,11 All arterial events (defined as aortic/arterial aneurysm, pseudoaneurysm, dissection, fistula, or rupture) were reviewed and noted. The minor diagnostic criteria include the following1,11:

Hypermobility of small joints.

Easy bruising that occurs spontaneous or with minimal trauma.

Thin translucent skin that is especially noticeable on the chest and abdomen.

Characteristic facial appearance8, which includes thin lips and philtrum, small chin, thin nose, large eyes, and attached ear lobes.8

Skin hyperextensibility.

Early-onset varicose veins.

Tendon or muscle rupture.

Pneumothorax/hemothorax (PTX, HTX).

Talipes equinovarus (clubfoot).

Arteriovenous carotid-cavernous sinus fistula (CCF).

Method of vEDS diagnosis was also reviewed. This included whether the diagnosis was made clinically without molecular confirmation or diagnosis that included molecular confirmation: biochemical testing of a skin biopsy confirming disruption of the type III collagen fibrils, and genetic testing for pathogenic mutations in COL3A1. Genetic testing results including the COL3A1 variant and protein effect were reviewed by a single geneticist (PHB) and classified for pathogenicity. COL3A1 variants were considered pathogenic (causative) if they met any of the following criteria in keeping with the ACMG guidelines3,7,12:

-

-

The variant resulted in substitution for a glycine residue in the Gly-X-Y repeats of the triple helical domain thus disrupting the type III collagen folding process and leading to production of a minimal amount of normal collagen. This type of mutation is called a missense mutation and is the most common type of mutation affecting COL3A1.

-

-

22The variant altered the canonical splice acceptor site (−1G, −2A) or donor site (+1G, +2T). This type of mutation can lead to exon skip and splice site mutations by creating a frameshift that result in exon (s) deletion leading to defective collagen production similar to missense mutations.

-

-

The variant creates premature termination codon either directly or through a frameshift. This type of mutation leads to a haploinsufficiency mutations (null mutation) and results in production of half the normal amount of type III collagen. The individuals affected by this type of mutation present at a later age and have milder arterial disease than those who have the missense or exon skipping mutations.

Variants were considered non-pathogenic if they created amino acid substitutions in the amino-terminal propeptide or altered X or Y-position amino acids in the triple helical domain and as such are not pathogenic3,5,13

Individuals were classified into two cohorts: pathogenic COL3A1 variants cohort and clinical diagnosis only cohort (no molecular confirmation). The demographics, major and minor diagnostic criteria, and arterial events between in the two cohorts were compared. Age results are presented as means and standard deviation. Age means were compared in the two cohorts using the Student t-test. Categorical data, including sex, presence of specific co-morbidities and diagnostic criteria, were compared between the two cohorts using the Pearson χ2 test. The comparison of all-cause mortality was performed using a Kaplan–Meier survival curve with Log-rank test comparison of the curves. The assumptions of Kaplan-Meier analysis were met: the event status is mutually exclusive between censored and mortality, the survival time is precisely measured and recorded, left-censoring is not occurring as the starting point of the survival time is clearly defined and recorded, censoring and the event (mortality) are independent, there is no secular trend over time that biases the mortality, the number and pattern of censoring in the two groups is similar. All statistical tests were two-sided and a P-value < .05 was considered statistically significant. Statistical analysis was performed using Microsoft Excel 2007 software (Microsoft, Redmond, WA) and SPSS version 19 for Windows (SPSS, Inc., Chicago, IL).

RESULTS

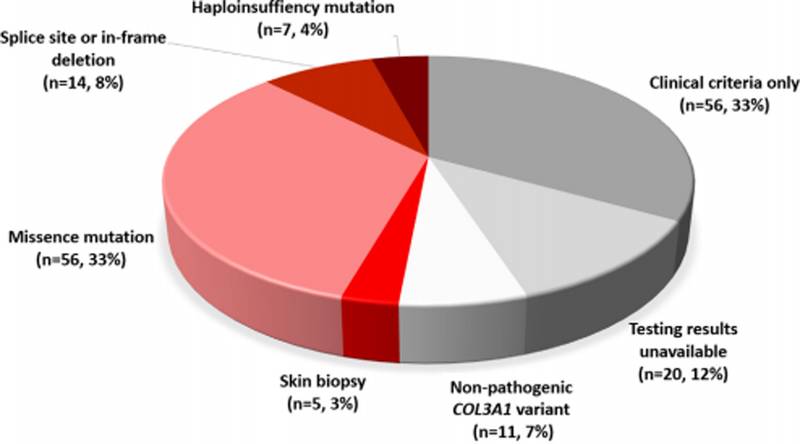

A total of 173 (35.3% male, 56.6% Caucasian) individuals were identified by chart review as having a diagnosis of EDS during the study period at 11 institutions: 9 in the United States (n= 149) and one each Germany (n=5) and Italy (n=19). Non-pathogenic alterations in COL3A1 were found in 11 (9.8%) who underwent genetic testing and as such they did not have vEDS and were excluded from subsequent analysis [N-terminal propeptide amino acid substitutions in the amino-terminal propeptide (n=3) and altered X or Y-position amino acids in the triple helical domain (n=8)]. Among the remaining individuals, 86 (47.7% male, 68% Caucasian, 48.8% positive family history) had pathogenic COL3A1 variants (Figure 1). Diagnosis of vEDS was made by clinical criteria only in 56 (34.5%) individuals. An additional 20 (12.3%) were noted to carry the diagnosis of vEDS but data from the genetic testing were unavailable for review and could not be obtained. A sensitivity analysis was performed and this demonstrated substantial differences between this group and the cohort with pathogenic COL3A1 variants, thus they were included in clinical diagnosis only cohort. In the end, 76 individuals (19.7% male, 19.7% Caucasian, 43.4% positive family history) were included in the clinical diagnosis only cohort

Fig 1.

Method of diagnosis of 173 patients identified as having vascular Ehlers-Danlos syndrome (vEDS).

Cohort with Pathogenic COL3A1 variants

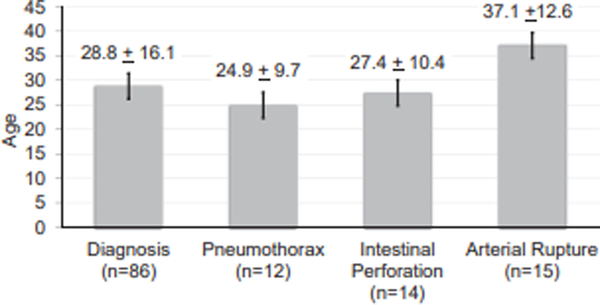

The diagnosis of vEDS was confirmed by genetic testing in 82 (50.6%) individuals, and by skin biopsy in 5 (3.1%) individuals. There was no difference in the age of diagnosis between males and females (28.2 ± 17.4 years vs. 29.4 ± 15.1 years, P=.748). Individuals with a family history of vEDS (not including children with vEDS) were younger at the age of diagnosis compared to those without a family history (21.3 ± 13.6 years vs 30.2 ± 13.7 years, P=.008). In contrast, among those with a child diagnosed with vEDS (n=11), the age of diagnosis was significantly older compared to the rest of the cohort (47.4 ± 18.8 years vs 26.5 ± 14.3 years, P<.001). There was the stepwise age increase with given complications so that spontaneous pneumothorax (n=12, 66.7% male) occurring at a younger age than spontaneous intestinal perforation (n=14, 42.3% male) and arterial rupture (n=15, 33.3% male) (Figure 2).

Fig 2.

Mean ± standard deviation age at diagnosis, at first spontaneous pneumothorax, at first intestinal perforation, and at first arterial rupture among individuals with vascular Ehlers-Danlos syndrome (vEDS) with confirmed pathogenic COL3A1 variants.

Comparison of the clinical features between the two cohorts

The clinical diagnosis only cohort had a significantly higher number of females compared to the cohort with pathogenic COL3A1 variants (80.3% vs. 52.3%, P<.001) and a significantly higher frequency of mitral valve prolapse (10.5% vs. 1.2%, P=.009). There were also differences in the frequency of minor and major clinical diagnostic (Table I). Among the minor diagnostic criteria, there was a significantly higher frequency of joint hypermobility (68.4% vs. 40.7%, P<.001), a significantly lower frequency of easy bruising (23.7% vs. 64%, P<.001) and thin translucent skin (17.1% vs. 48.8%, P<.001). In terms of major diagnostic criteria, this cohort had a significantly lower frequency of arterial rupture, intestinal perforation, and spontaneous pneumo/hemothorax (Table I). The number of arterial events was significantly higher among those with pathogenic COL3A1 variants (Table II).

Table I.

Demographics, major, and minor diagnostic criteria of 162 individuals with vascular Ehlers-Danlos WEDS) syndrome at 11 institutions

| Variable | Pathogenic COLSA1 variants (n − 86) | Clinical diagnosis of vEDS (n − 76) | P value |

|---|---|---|---|

| Age at diagnosis | 28.8 ± 16.2 | 27.3 ± 12.5 | 0.636 |

| Male | 41 (47.7) | 15 (19.7) | <0.001 |

| Race | <0.001 | ||

| Caucasian | 74 (86) | 15 (19.7) | |

| Multi-racial | 7 (8.1) | 3 (3.9) | |

| African American | 1 (0.9) | 0 | |

| Native American | 1 (0.9) | 0 | |

| Unknown | 3 (3.5) | 58 (76.3) | |

| Comorbid conditions | |||

| Hypertension | 19 (22.1) | 11 (14.5) | 0.213 |

| Deep vein thrombosis | 13 (15.1) | 6 (7.9) | 0.154 |

| Mitral valve prolapse | 1 (1.2) | 8 (10.5) | 0.009 |

| Smoker (past or current) | 17 (19.8) | 26.3 (20) | 0.322 |

| Family historya | 42 (48.8) | 33 (43.4) | 0.490 |

| Major complications | |||

| Arterial rupture | 15 (17.4) | 7 (9.2) | 0.127 |

| Any arterial pathologyc | 53 (61.6) | 16 (21.1) | <0.001 |

| Intestinal perforation | 14 (16.3) | 3 (3.9) | 0.011 |

| Uterine ruptureb | 4 (18.2) | 0 | 0.019 |

| Minor Diagnostic Criteria | |||

| Hypermobility of small joints | 35 (40.7) | 52 (68.4) | <0.001 |

| Easy bruising | 55 (64) | 18 (23.7) | <0.001 |

| Thin, translucent skin | 42 (48.8) | 13 (17.1) | <0.001 |

| Characteristic facial features | 27 (31.4) | 6 (7.9) | <0.001 |

| Skin hyperextensibilty | 12 (14) | 10 (13.2) | 0.883 |

| Early-onset varicose veins | 13 (15.1) | 2 (2.6) | 0.006 |

| Tendon or muscle rupture | 9 (10.5) | 6 (7.9) | 0.573 |

| Spontaneous Pneumo/hemothorax | 12 (14) | 3 (3.9) | 0.028 |

| Carotid-cavernous fistula | 4 (4.7) | 1 (1.3) | 0.221 |

| Clubfoot | 8 (9.3) | 3 (3.9) | 0.176 |

| Follow up Duration post diagnosis | 8.2 ± 8.2 | 9.8 ± 8.8 | 0.349 |

| Mortality | 13 (15.1%) | 6 (7.9%) | 0.154 |

The P value is for the comparisons between those with molecular confirmation showing pathogenic COL3AI variants and those diagnosed using clinical criteria without molecular confirmation. Values are presented as number (%) or mean z standard deviation.

Family history of vEDS, aortic & arterial aneurysms and dissections, sudden death

Of 52 patients who had pregnancies.

Defined as defined as aortic/arterial aneurysm, pseudoaneurysm, dissection, fistula, or rupture.

Table II.

Demographics of individuals with vascular Ehlers-Dantos syndrome 1 vEDS) iMio experiervced an arterial event.

| Variable | Pathogenic COL3A1 variants (n − 55) | Clinical diagnosis of vEDS (n − 16) | P value |

|---|---|---|---|

| Male | 27 (50.9) | 10 (62.5) | 0.417 |

| Caucasian | 47 (88.7) | 11 (68.8) | 0.056 |

| Comorbid conditions | |||

| Hypertension | 17 (32.1) | 3 (18.8) | 0.303 |

| Deep vein thrombosis | 12 (22.6) | 3 (18.8) | 0.741 |

| Smoker (past or current) | 12 (22.6) | 2 (12.5) | 0.377 |

| Family historya | 30 (56.6) | 6 (37.5) | 0.180 |

| Minor Diagnostic Criteria | |||

| Spontaneous Pneumo/hemothorax | 7 (13.2) | 2 (12.5) | 0.941 |

| Carotid-cavernous fistula | 4 (7.5) | 1 (6.3) | 0.861 |

| Hypermobility of small joints | 17 (32.1) | 10 (62.5) | 0.029 |

| Easy bruising | 32 (60.4) | 10 (62.5) | 0.879 |

| Thin, translucent skin | 26 (49.1) | 5 (31.3) | 0.209 |

| Characteristic facial features | 16 (30.2) | 6 (37.5) | 0.582 |

| Skin hyperextensibilty | 8 (15.1) | 4 (25) | 0.360 |

| Early-onset varicose veins | 8 (15.1) | 2 (12.5) | 0.796 |

| Tendon or muscle rupture | 5 (9.4) | 2 (12.5) | 0.722 |

| Clubfoot | 6 (11.3) | 1 (6.3) | 0.556 |

| Age at first arterial diagnosis | 34.6 ±12.5 | 35.1 ±12.5 | 0.877 |

| Age at first arterial diagnosis (Males) | 32.8 ±14.1 | 37.1 ±12.8 | 0.423 |

| Age at first arterial diagnosis (Females) | 34.4 ±11.7 | 32.2 ±12.6 | 0.674 |

| Diagnosis established prior to index arterial pathology diagnosis | 21 (38.9) | 9 (56.3) | 0.218 |

| Arterial Rupture | 15 (17.4) | 7 (9.2) | 0.127 |

| Arterial pathologyb | |||

| Carotid and Vertebral arteries | 19 (22.1) | 3 (3.9) | 0.001 |

| Age | 32.6 ±12.5 | 21.3 ±2.5 | 0.060 |

| Aorta | 17 (19.8) | 2 (2.6) | 0.001 |

| Age | 37.1 ±15.8 | 40 ±12.7 | 0.805 |

| Mesenteric arteries | 22 (25.6) | 7 (9.2) | 0.007 |

| Age | 40.1 ±11.3 | 34.2 ±12.2 | 0.216 |

| Renal arteries | 12 (14) | 4 (5.3) | 0.064 |

| Age | 38.3 ±9.4 | 32.8 ±105 | 0.417 |

| Iliac arteries | 17 (19.8) | 5 (6.6) | 0.014 |

| Age | 38.2 ±9.4 | 40 ±13.7 | 0.766 |

| Follow up post first arterial pathology diagnosis (years) | 7.2±6 | 6.2±7.2 | 0.579 |

The P value is for the comparisons between those with molecular confirmation showing pathogenic COL3AI variants and those diagnosed using clinical criteria without molecular confirmation. Values are presented as number (%) or mean z standard deviation.

of vEDS, aortic & arterial aneurysms and dissections, sudden death

Defined as defined as aortic/arterial aneurysm, pseudoaneurysm, dissection, fistula, or rupture..

Mortality

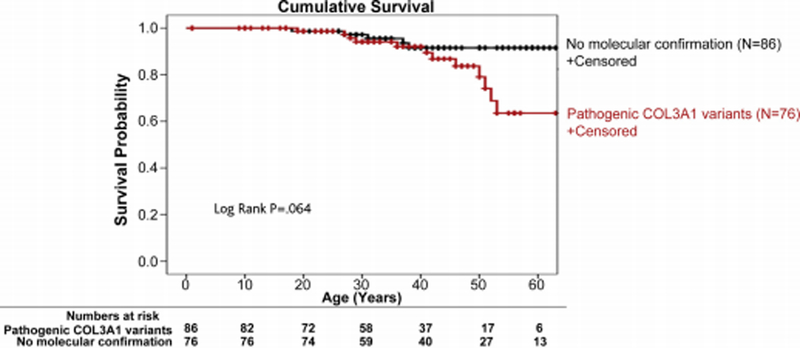

There were no differences in all-cause mortality (Figure 3) between the cohort with pathogenic COL3A1 variants and the cohort diagnosed without molecular confirmation (Table I). In the cohort with pathogenic COL3A1 variants, the mean follow up from the time of diagnosis was 8.2 ± 8.28 years. There were 13 (15.1%) deaths at a mean age of 40.3 ± 15.5. Causes of death were due to the following: 2 due to strokes, 1 due to a coronary artery dissection, 1 due to ventricular rupture, 2 related to artic dissections, 1 related to hemothorax, 1 due to mesenteric arterial ruptures, and in the rest of the cases, the cause was unknown. In the cohort without molecular confirmation, the mean follow up from the time of diagnosis was 9.8 ± 8.8 years. There were 6 (7.8%) deaths in this group (mean age 35.8 ± 15.6 years). Causes of deaths were noted as a hemorrhagic stroke (n=1), dissection and rupture without further detail (n=1), complications from a perforated viscus (n=1), and unknown (n=3).

Fig 3.

Kaplan-Meier estimate of cumulative survival in individuals with vascular Ehlers-Danlos syndrome (vEDS). Individuals with confirmed diagnosis showing pathogenic COL3A1 variants are compared with individuals diagnosed using clinical criteria without additional molecular testing.

DISCUSSION

Due to its rarity and heterogeneous presentation, the diagnosis of vEDS can be difficult even for experienced clinicians. This contemporary experience from 11 institutions highlights the challenges related to an accurate diagnosis of vEDS. In this cohort, one third of the individuals were given the diagnosis of vEDS based on clinical criteria alone without confirmatory molecular testing in the form of skin biopsy or genetic testing for pathogenic variants in COL3A1. The demographics and disease manifestations among this group make it clear that this was a different group than those with pathogenic COL3A1 variants. In fact, their most common features were more consistent with hypermobile EDS or classical EDS than with vEDS (both in which skin hyperextensibility and generalized joint hypermobility are major diagnostic criteria).1,14 This suggests that at least for this cohort, the diagnosis of vEDS in the absence of confirmatory testing cannot be trusted. In the period that overlaps the time span for this study, gene discovery studies had identified more than a dozen genes associated with aneurysms and dissections. Some of those conditions overlap clinically with vEDS such as other forms of EDS that result from mutations in COL5A1 and COL1A1.1 Thus while the major and minor diagnostic clinical criteria can be used to help raise the suspicion for a vEDS the diagnosis must be confirmed by genetic testing. In vEDS, the major diagnostic criteria have high diagnostic specificity.1 Even when these diagnostic clinical criteria are present, molecular testing is essential to confirm the diagnosis.

A confirmation of the diagnosis by molecular testing is critical for several reasons. Not only are there clinical features overlap with the other subtypes of EDS, there are clinical features overlap with other heritable connective tissues disorders and genetically triggered arteriopathies that result from mutations in the genes involved in the transforming growth factor-beta (TGF-β) signaling pathway, extracellular matrix production, and aortic smooth muscle cells development and function.2,15–19 Establishing the correct diagnosis has serious implications of lifelong surveillance, medical and surgical management recommendations, and pregnancy planning for the patient and family members.2,8 The diagnosis can be confirmed by obtaining a skin biopsy or by genetic testing for pathogenic variants in the COL3A1, but the latter is the contemporary approach to diagnosis.2

As not all COL3A1 variants are pathogenic, the interpretation of the genetic testing results by an individual trained in variant assessment in keeping with the ACMG guidelines3,7,12 is essential to establishing the diagnosis. We found that nearly 10% of individuals in whom at least some of the clinical criteria for vEDS were met had non-pathogenic COL3A1 variants and with current criteria did not have vEDS. This, too, has substantial implications for the individuals and their family members as previously mentioned.

Accurate diagnosis of vEDS has research implications. An example derives from the BBEST celiprolol trial, which aimed to assess if celiprolol (a long acting β1 adrenergic receptor antagonist with partial β2 adrenergic receptor agonist) would reduce the risk of arterial dissections and ruptures in treated individuals.20 In this trial, the 53 enrolled individuals had the diagnosis of vEDS made by clinical criteria alone and only 33 were found to have a pathogenic COL3A1 variant (52% in the celiprolol arm and 71% of the controls). The trial concluded that celiprolol reduced arterial rupture after extended treatment, based in part on the whole cohort. The presence of a misidentified, disease process in those patients diagnosed by clinical criteria only suggests that the trial’s experimental group was populated with patients at less (or more) risk for arterial events than the control group. Celiprolol is currently unavailable in the United States. Medical management in vEDS has been extrapolated from this study (use of beta-blockers) as well as management of Marfan syndrome (use of atenolol and losartan) without additional trials in place.20–22 A pragmatic trial to evaluate the role of anti-impulse therapy in patients with vEDS is still necessary to establish efficacy for celiprolol or other beta-blockers.

In this study, vEDS diagnosis was made at an earlier age in the setting of a family history of other family members with vEDS or a history of aortic or arterial aneurysms or dissections. This has been previously demonstrated2 and highlights an opportunity for early diagnosis.23 However, the family history is frequently absent as 50% people in whom the diagnosis of vEDS is made have de novo mutations in COL3A1 and the patient is the first in their family to have the mutation.3,5 An additional window of opportunity for early diagnosis is at the time of presenting with a spontaneous pneumothorax, as this appears to present at a younger age with male predominance compared to individuals presenting with intestinal or arterial events as demonstrated in this series and in a recent report on a separate cohort of patients with vEDS.24

This study demonstrates the limits related to the use of a diagnostic code when it does not discriminate among different bases for a common “disorder”. All 13 types of EDS are included in a single diagnostic code in both ICD-9 and ICD-10 (Q79.6). This creates confusion among clinicians and individuals with limited experience with vEDS and prevents the use of administrative data sets the study of vEDS. As a result, there is a call for creation of separate ICD codes for the different subtypes by the patient advocacy groups.

The study is limited by the relative small numbers of cases. The syndrome is rare thus, accruing large numbers for analysis is challenging even in multi institutional study designs. By virtue of the study design, it was not possible to ascertain systematically how these individuals in this cohort came to clinical attention and as such, this cohort may not be representative of the entire vEDS population. In this cohort, over half of the individuals in this cohort had an arterial event and the median age of death (38.5 years) was younger than was has been previously reported (51 years).7,25 The younger death is, in part, could be due to the identifications of individuals with a severe phenotype who are identified because of a complication. Additionally, due to the rarity of vEDS, few clinicians have encountered affected individuals and as such, this could lead to under recognition of the milder phenotypes. Despite these limitations, the study adds to our understanding of vEDS and the importance of accurate diagnosis.

CONCLUSIONS

This study highlights the importance of confirming vEDS diagnosis by testing for pathogenic COL3A1 variants rather than making the diagnosis by using clinical diagnostic criteria alone. This is highly relevant as the clinical features of vEDS overlap with those of other forms of EDS and other genetically triggered arteriopathies. Interpretation of the testing results by an individual trained in variant assessment is essential to confirm the diagnosis given that not all variants of COL3A1 are pathogenic. Accurate diagnosis is critical and has serious implications for lifelong screening and treatment strategies for the affected individual and family members as well as for research to identify treatments, genetic modifiers, and outcomes.

Article Highlights.

Type of Research:

Multi-institutional descriptive cross sectional study of the Vascular Low Frequency Disease Consortium.

Key Findings:

Out of 173 individuals diagnosed with vEDS based on clinical criteria, genetic testing for pathogenic COL3A1 variants was used to confirm the final diagnosis in 86 patients.

Take Home Message:

Clinical criteria alone is inadequate to establish the diagnosis of vEDS and genetic testing for pathogenic COL3A1 variants appears important. Accurate diagnosis is critical and has serious implications for lifelong screening, medical, and surgical management strategies for the affected individual and family members.

Acknowledgments

The authors acknowledge Binod Shrestha (Department of Cardiovascular and Vascular Surgery, at the University of Texas Health Science Center at Houston) for assisting with data collection at the University of Texas Health Science Center at Houston.

Funding:

The research was supported in part the National Center for Advancing Translational Sciences of the National Institutes of Health under Award Number UL1TR000423 (SS), in part by funds from the Freudmann Fund for Translational Research in Ehlers-Danlos syndrome at the University of Washington (PHB), and in part by the National Institute of Health (NIDDK 1K08DK107934) (KW). The content is solely the responsibility of the authors and does not necessarily represent the official views of the National Institutes of Health.

Presentation:

This work was presented in part at the Society for Clinical Vascular Surgery 45th Annual symposium, March 2017

Footnotes

Conflicts of Interest: None

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References

- 1.Malfait F, Francomano C, Byers P, Belmont J, Berglund B, Black J, et al. The 2017 international classification of the Ehlers-Danlos syndromes. Am J Med Genet C Semin Med Genet 2017; 175: 8–26. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Byers PH, Belmont J, Black J, De Backer J, Frank M, Jeunemaitre X, et al. Diagnosis, natural history, and management in vascular Ehlers-Danlos syndrome. Am J Med Genet C Semin Med Genet 2017; 175: 40–7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Pepin M, Schwarze U, Superti-Furga A, Byers PH. Clinical and genetic features of Ehlers-Danlos syndrome type IV, the vascular type. N Engl J Med 2000; 342: 673–80. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Pope FM, Martin GR, Lichtenstein JR, Penttinen R, Gerson B, Rowe DW, et al. Patients with Ehlers-Danlos syndrome type IV lack type III collagen. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 1975; 72: 1314–6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Pepin MG, Murray ML, Byers PH. Vascular Ehlers-Danlos Syndrome. In: Adam MP, Ardinger HH, Pagon RA, et al. , eds. GeneReviews(R) Seattle (WA); 1993. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Murray ML, Pepin M, Peterson S, Byers PH. Pregnancy-related deaths and complications in women with vascular Ehlers-Danlos syndrome. Genet Med 2014; 16(12): 874–80. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Pepin MG, Schwarze U, Rice KM, Liu M, Leistritz D, Byers PH. Survival is affected by mutation type and molecular mechanism in vascular Ehlers-Danlos syndrome (EDS type IV). Genet Med 2014; 16: 881–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Shalhub S, Black JH 3rd, Cecchi AC, Xu Z, Griswold BF, Safi HJ, et al. Molecular diagnosis in vascular Ehlers-Danlos syndrome predicts pattern of arterial involvement and outcomes. J Vasc Surg 2014; 60: 160–9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Eagleton MJ. Arterial complications of vascular Ehlers-Danlos syndrome. J Vasc Surg 2016; 64: 1869–80. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Harlander-Locke MP, Lawrence PF. The Current State of the Vascular Low-Frequency Disease Consortium. Ann Vasc Surg 2017; 38: 8–9. [Google Scholar]

- 11.Beighton P, De Paepe A, Steinmann B, Tsipouras P, Wenstrup RJ. Ehlers-Danlos syndromes: revised nosology, Villefranche, 1997. Ehlers-Danlos National Foundation (USA) and Ehlers-Danlos Support Group (UK). Am J Med Genet 1998; 77: 31–7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Leistritz DF, Pepin MG, Schwarze U, Byers PH. COL3A1 haploinsufficiency results in a variety of Ehlers-Danlos syndrome type IV with delayed onset of complications and longer life expectancy. Genet Med 2011; 13: 717–22. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Schwarze U, Schievink WI, Petty E, Jaff MR, Babovic-Vuksanovic D, Cherry KJ, et al. Haploinsufficiency for one COL3A1 allele of type III procollagen results in a phenotype similar to the vascular form of Ehlers-Danlos syndrome, Ehlers-Danlos syndrome type IV. Am J Hum Genet 2001; 69: 989–1001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Brady AF, Demirdas S, Fournel-Gigleux S, Ghali N, Giunta C, Kapferer-Seebacher I, et al. The Ehlers-Danlos syndromes, rare types. Am J Med Genet C Semin Med Genet 2017; 175: 70–115. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Milewicz DM, Regalado E. Heritable Thoracic Aortic Disease Overview. In: Pagon RA, Adam MP, Ardinger HH, et al. , eds. GeneReviews(R) Seattle (WA); 1993. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Brownstein AJ, Kostiuk V, Ziganshin BA, Zafar MA, Kuivaniemi H, Body SC et al. Genes Associated with Thoracic Aortic Aneurysm and Dissection: 2018 Update and Clinical Implications. Aorta (Stamford) 2018; 6: 13–20. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Karimi A, Milewicz DM. Structure of the Elastin-Contractile Units in the Thoracic Aorta and How Genes That Cause Thoracic Aortic Aneurysms and Dissections Disrupt This Structure. Can J Cardiol 2016; 32: 26–34. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Regalado ES, Mellor-Crummey L, De Backer J, Braverman AC, Ades L, Benedict S, et al. Clinical history and management recommendations of the smooth muscle dysfunction syndrome due to ACTA2 arginine 179 alterations. Genet Med 2018. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Milewicz D, Hostetler E, Wallace S, Mellor-Crummey L, Gong L, Pannu H, et al. Precision medical and surgical management for thoracic aortic aneurysms and acute aortic dissections based on the causative mutant gene. J Cardiovasc Surg (Torino) 2016; 57: 172–7. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Ong KT, Perdu J, De Backer J, Bozec E, Collignon P, Emmerich J, et al. Effect of celiprolol on prevention of cardiovascular events in vascular Ehlers-Danlos syndrome: a prospective randomised, open, blinded-endpoints trial. Lancet 2010; 376: 1476–84. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Lacro RV, Dietz HC, Sleeper LA, Yetman AT, Bradley TJ, Colan SD,et al. Atenolol versus losartan in children and young adults with Marfan’s syndrome. N Engl J Med 2014; 371: 2061–71. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Milleron O, Arnoult F, Ropers J, Aegerter P, Detaint D, Delorme G,et al. Marfan Sartan: a randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled trial. Eur Heart J 2015; 36: 2160–6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Hicks KL, Byers PH, Quiroga E, Pepin MG, Shalhub S. Testing patterns for genetically triggered aortic and arterial aneurysms and dissections at an academic center. J Vasc Surg 2018. September;68:701–711 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Shalhub S, Sanchez D, Dua A, Arellano N, McDonnell NB, Milewicz DM. Spontaneous pneumothorax and hemothorax frequently precede the Arterial and Intestinal complications of Vascular Ehlers Danlos syndrome. Am J Med Genet A. 2019. February 22 [Epub ahead of print] [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Frank M, Albuisson J, Ranque B, Golmard L, Mazzella JM, Bal-Theoleyre L, et al. The type of variants at the COL3A1 gene associates with the phenotype and severity of vascular Ehlers-Danlos syndrome. Eur J Hum Genet 2015; 23: 1657–64. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]