To the Editor:

The health emergency caused by the COVID-19 pandemic led to a state of alarm being declared in Spain on 14 March 2020. Consequently, substantial changes were needed to reorganize Spanish health services. However, there has also been growing concern about diseases unrelated to COVID-19. To ensure continuity of quality health care for patients with heart disease, it is important to differentiate between deferrable and nondeferrable activity with specific objectives. At our hospital, this has meant that most scheduled activities were postponed. This scientific letter describes the gradual development of health care protocols for our Outpatient Cardiology Department. This organizational approach was developed to stratify patients, thus allowing patients in poor clinical condition to be seen personally and patients with stable disease to avoid in-person visits.

In the first phase (11-16 March 2020), a telephone follow-up protocol was implemented and in-person care was maintained for new patients with the relevant additional tests, based on the usual model aimed at rapid resolution. table 1 summarizes the care provided in the first 48 hours to a total of 278 patients during phase 1: 202 (72.7%) telemedicine visits and 76 (27.3%) new in-person visits. Among these, 14 (18.4%) new patients decided not to attend and follow-up visits were conducted with all patients except for 12 (5.9%), for whom telephone contact was not achieved and new appointments were made. In the second phase, all new and follow-up visits were performed remotely. This organizational structure requires the same number of cardiologists as in-person visits, but allows physicians at higher risk of contagion to be assigned to these positions.

Table 1.

Reasons for visit, history of heart disease, and actions taken in 278 patients

| Type | Age, y | Women | Reason for visit/heart disease | Tests performed | Treatment | Follow-up, mo | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| New, in-person |

76 (27) |

59 ± 19 |

38 (61.3) |

Chest pain |

12 (19.3) |

Electrocardiogram |

53 (85.5) |

Discharge |

35 (56.2) |

8 ± 10 |

| Symptoms of HF |

6 (9.7) |

TTE |

40 (64.5) |

Treatment changes |

8 (12.9) |

|||||

| Palpitations |

11 (17.7) |

Stress test |

5 (6.5) |

Additional tests |

21 (33.8) |

|||||

| Dizziness/syncope |

3 (4.8) |

|||||||||

| Murmur |

3 (4.8) |

|||||||||

| ECG abnormalities |

9 (14.5) |

|||||||||

| Family screening |

9 (14.5) |

|||||||||

| Other |

9 (14.5) |

|||||||||

| Follow-up visits, telemedicine visit | 202 (73) | 66 ± 17 | 78 (41.1) | Ischemic heart disease |

50 (26.3) |

— |

Discharge |

38 (20.0) |

9 ± 5 | |

| Valvular heart disease |

35 (18.4) |

Treatment changes |

42 (22.1) |

|||||||

| HF |

23 (12.1) |

Additional tests |

106 (55.8) |

|||||||

| Cardiomyopathies |

17 (8.9) |

|||||||||

| Arrhythmias |

38 (20) |

|||||||||

| Congenital heart disease |

9 (4.7) |

|||||||||

| Pulmonary hypertension |

5 (2.6%) |

|||||||||

| Other | 13 (6.8) | |||||||||

ECG, electrocardiography; HF, heart failure; TTE, transthoracic echocardiography.

The values are expressed as No. (%) or mean ± standard deviation.

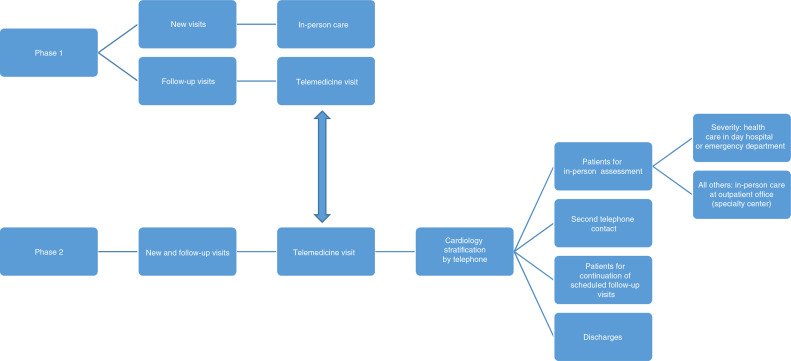

An e-mail address was created for patients to send previous reports, electrocardiograms, and additional tests already carried out. Following telephone contact, the clinicians decided which patients required urgent assessment and which patients could be deferred, allowing discharges and appointments to be arranged for preferential or scheduled evaluations (figure 1 ). Last, a second telephone contact was possible for patients with any changes in treatment, to check on tolerance and ensure clinical stability.

Figure 1.

Organizational chart for Outpatient Cardiology Department visits during the SARS-CoV-2 pandemic.

As shown in table 1, telemedicine visits proved to be suitable for medical discharges, medication changes, and additional medical tests. A subsequent clinical follow-up visit was scheduled for a mean of 9 ± 5 months later. This organizational model currently offers telemedicine to 575 follow-up patients and 125 new patients each week. These telephone calls resulted in only 2 to 4 (1.7%-3.5%) of these patients selected for priority in-person evaluation each day, most of them patients with symptomatic ischemic heart disease and decompensated heart failure.

We developed the following protocol for in-person care: a) initial nurse triage, with a brief medical history, including potential COVID-19 infection symptoms (fever, cough, myalgia) and epidemiologic risk contacts; b) temperature measurement using an infrared thermometer, and c) patient routing into 2 groups with separate waiting rooms: patients with suspected or confirmed COVID-19 infection were seen by health care workers using heightened protection measures and all others were assessed in conventional outpatient offices, but with universal personal protection equipment (eg, surgical masks, gloves, gowns). Both groups had access to electrocardiograms, echocardiograms, blood work, and chest X-rays. We believe that this approach to health care lowered the number of emergency visits and hospitalizations. In addition, this approach has prevented indefinite postponement of all outpatient activity and avoided overstraining the health care system after the pandemic.

The COVID-19 pandemic has raised questions about the need for in-person visits, which should be considered a second or last option.1 This pandemic has considerable repercussions for the health of patients with heart disease2, 3 and often affects health care workers.4 Many health care workers are quarantined due to situations of risk, exposure, or infection due to COVID-19. Some physicians can perform health care activities that are essential for patient care and resource optimization. The COVID-19 pandemic has been a unique challenge, particularly in a country with a large aging population,5 even for cardiology departments.

It is too soon to evaluate the overall health care impact of this type of consultation and its capacity to resolve health issues. Prospective studies with long follow-up periods are likely necessary to evaluate the results and potential adverse effects and to draw conclusions. We do not yet know the potential implications of telemedicine on vastly different areas such as the psychosocial and legal fields. However, although telemedicine is not the only approach to solving this challenge,6 we believe that it could be suitable for the present scenario.

.

References

- 1.Hollander J.E., Carr B.G. Virtually perfect? Telemedicine for Covid-19. N Engl J Med. 2020 doi: 10.1056/NEJMp2003539. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Xiong T.Y., Redwood S., Prendergast B., Chen M. Coronaviruses and the cardiovascular system: acute and long-term implications. Eur Heart J. 2020 doi: 10.1093/eurheartj/ehaa231. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Clerkin K.J., Fried J.A., Raikhelkar J. Coronavirus Disease 2019 (COVID-19) and cardiovascular disease. Circulation. 2020 doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.120.046941. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.McMichael T.M., Currie D.W., Clark S. Epidemiology of Covid-19 in a long-term care facility in King County. Washington. N Engl J Med. 2020 doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa2005412. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Bonanad C., García-Blas S., Tarazona-Santabalbina F. Coronavirus: la emergencia geriátrica de 2020. Documento conjunto de la Sección de Cardiología Geriátrica de la Sociedad Española de Cardiología y de la Sociedad Española de Geriatría y Gerontología. Rev Esp Cardiol. 2020 doi: 10.1016/j.recesp.2020.03.027. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.National Health Service – NHS. Clinical guide for the management of cardiology patients during the coronavirus pandemic. Available at: https://www.england.nhs.uk/coronavirus/wp-content/uploads/sites/52/2020/03/specialty-guide-cardiolgy-coronavirus-v1-20-march.pdf. Accessed 29 Apr 2020.