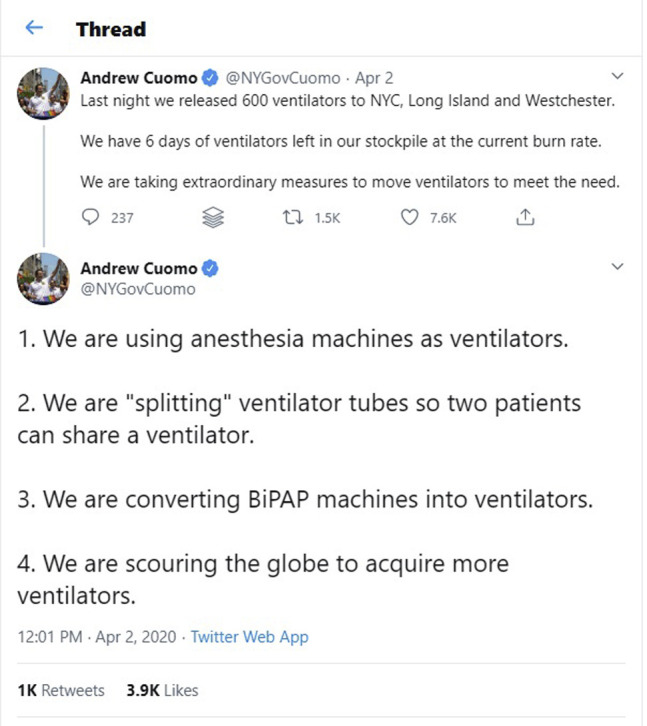

I could hardly believe what I was reading. The Governor of New York had just tweeted that New York City would soon run out of ventilators (Fig 1 ). It was made all the more surreal because I sat in an ICU with several idle ventilators. In preparation for the pandemic, our small rural hospital had purchased several; it was perhaps the one thing that we had plenty of.

Figure 1.

Tweet by New York Governor Andrew Cuomo on April 2, 2020.

We had yet to see a coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) surge in our hospital, but we were already running short of N95 masks. The same masks that I had so casually discarded into waste bins just a week earlier were now being managed much more like a controlled substance than the simple piece of personal protection that they were. Now each one was a precious commodity, carefully inventoried and tracked. As I entered a patient room, a spotter verified my signature, employee ID, and phone number, then countersigned the information. On leaving the room, I now gingerly placed the N95 mask in a brown paper bag to be reused.

As I surveyed the news about New York City, I wondered why we couldn’t lend some of our excess ventilators to them. Projections showed that North Carolina’s surge was several weeks away, and many states would be well within their health system’s capacity.

I started checking in with different colleagues who worked in ICUs around the country. As I did, I found that each faced their own unique challenges in the face of the pandemic. Some were being overwhelmed by cases while others like me were frustrated by their inability to help. What follows are firsthand stories from four physicians from ICUs around the country. Despite their distance, a common thread flows through them. All of us, whether being flooded by a surge of patients, hindered by an ossified and fragmented health care system, or constrained by a lack of effective therapies, shared a sense of helplessness in the face of COVID-19. Yet despite the incredible challenges, health care workers like these showed tremendous resilience despite seemingly insurmountable odds.

—Burlington, North Carolina

From my perch in Upstate New York, I could see that the numbers were rising dramatically in New York City, where I had completed my fellowship. Now I work 5 hours away from the city that was my home for 3 years. As calls came in from friends and colleagues there, I could see the desperation in their texts, hear the panic rising in their voices.

Many of them pleaded for the same thing: “We need ventilators,” they said. I stayed with them on the phone, if only as kindred spirits, lending what support I could. “Help will come,” I told them, hoping and praying that it would. Soon, word spread that some patients from New York City would be transported to Upstate New York centers such as mine to help deal with the surge. We welcomed the possibility; all of us wanted to stand side-by-side with our colleagues in this fight. We painstakingly prepared to face the surge of patients from NYC. It never came. Ultimately, we could offer little in the way of help but a few ventilators. Now we sat on the sidelines watching day after day as the COVID-19 surge hit New York City like a tidal wave.

I watched in horror as my brothers and sisters on the front lines were resorting to do-it-yourself equipment, using the same mask for days on end, and going to battle donning garbage bag armor. Watching all of this, it was hard not to feel guilty as I donned my own personal protective equipment (PPE), picked from piles neatly stacked in front of patient rooms. How was any of this right?

I stayed up late one night talking to a friend who had just intubated a patient, using their last ventilator. He wept as he recalled the magnitude of the human suffering he had witnessed. A lifetime’s worth, condensed into 1 day.

“Just hold on,” I told him, “They are getting you the supplies. I love you, please stay safe.”

—Syracuse, New York

Before all of this, our units were full of life. Yes, death and dying are a part of every ICU. Yes, the suffering was very real, as was the moral injury, but there was life with it. Sorrow but also joy. There were crowds around every corner, cardiologists and nephrologists debating fluid balance while surgeons briskly palpated abdomens. Waiting rooms had sons and daughters sprawled out keeping audible vigil or, yes, sobbing at the bedside as we performed chest compressions. The halls were filled with therapists and patients moving, moving, always toward recovery. Now everything is different. Now, everything is frozen in place. When I hear the language used to describe what is happening in hospitals across the world, one image comes to mind: warfare—chaotic, bloody, and loud. But, in my ICU in Boston, that couldn’t be further from my experience. Now, walking around my ICU, it is far from a warzone. It is much more like a graveyard. Quiet, still, and empty. The crowds are gone. Medicine has bowed its head before COVID and dropped to its knees. Families, once welcomed and invited, are banned. Walking through the unit now, one after another room, all full, all with patients on ventilators. The life that filled the hallways is gone. Those of us left here stay as far from one another as we can, because the best defense is distance. The anxiety is palpable; consultants deliver terse advice virtually. Among clinicians, our interactions are quick and to the point, all emotion is buried behind the ubiquitous mask. We gather outside the room of a young woman. As I enter, the decision is obvious. She is exhausted, pushing herself to breathe harder, faster. She calls her family, panting—I love you, I love you, I love you. And then the tube goes in and she is out, joining the others all along the hall on life support. That is what it is like for all of us in the ICU. Our masks cover our mouths, and we can't describe the magnitude of the suffering we’re seeing here. But we can listen—sometimes that is all we can do.

—Boston, MA

At a large hospital in Chicago, a call to arms had been issued. The surge was coming, to our hospital, and our ICU, we were told, and we needed to prepare. It didn't matter what your specialty was, or whether you were still a trainee like myself, it was all hands on deck. A daily stream of emails detailed the COVID-19 protocols being instituted, throughout the health system. So many that it seemed hard for anyone to keep up. Ventilator inventories were checked and double-checked, and ICU beds were being created. All elective procedures were canceled. Clinics were canceled, and the era of the tele-visit had begun. These were not normal times, I realized. We don’t fall short of PPE in normal times. We don’t run out of essential medications and ventilators in normal times. We don’t have discussions about rationing care in normal times. I sat in the bronchoscopy suite, wondering to myself, how did it come to this? What could we have done differently? It felt like time was coming to a standstill. Meanwhile, my text messages were blowing up. While I sat 800 miles away from New York City, where I had trained for my fellowship, my friends and mentors were being overwhelmed and crushed. Now in their time of need, I could do very little. I, like many of my peers who were international medical graduates, were working on visas and could not rush to their aid because of immigration laws. All we could do was wait and be prepared.

—Chicago, Illinois

I had never felt fear before in my career. Being a female intensivist in a male-dominated specialty, I never had that luxury. But now, for the first time in my career, sitting alone in an office marked “ICU Director” in a New York City hospital, I was afraid. As an ICU director in charge of five of the hardest-hit ICUs in the country, I was being told that we were short of ventilators for the night and short of tubing for the ventilators that we did have. I feared not knowing how to respond, who to turn to, how to proceed, or what to do next. I decided to play the odds and move ventilators from hospitals in our system that were less hard hit to ones that were getting slammed. There was no room in the ED; people were dying while waiting to be seen—those were the words I was being told. What do we do next? We spoke endlessly about moving patients, opening new ICUs immediately, and trying to find staffing to open those units in multiple hospitals. How will we make it through the night? How can we safely take care of all of these patients? Sitting in the hospital was terrifying; every 15 minutes or so I would hear a rapid response closely followed by “anesthesia stat,” and another ventilator was gone. I sat overwhelmed and helpless; they just kept calling, and every time I cringed. What will we do? I have never in my 15-year career felt so helpless. I tried to focus on one patient at a time as the sick and the dying poured in. And in they came, without stopping, it seemed. Until they filled our unit, our floor, our hospital, our city.

—New York, New York

Footnotes

FINANCIAL/NONFINANCIAL DISCLOSURES: None declared.