Abstract

Objective

To analyze clinical characteristics and outcome of COVID-19 patients with underlying rheumatic diseases (RD) on immunosuppressive agents.

Method

A case series of COVID-19 patients with RD on disease modifying anti-rheumatic drugs (DMARDs) were studied by a retrospective chart review. A literature search identified 9 similar studies of single cases and case series, which were also included.

Results

There were 4 COVID-19 inpatients with RD from our hospital, and the mean age was 57 ± 21 years. Two patients had a mild infection, and 2 developed severe COVID-19 related respiratory complications, including 1 patient on secukinumab requiring mechanical ventilation and 1 patient on rituximab developing viral pneumonia requiring supplemental oxygenation. All 4 patients had elevated acute phase reactants, 2 patients had mild COVID-19 with lymphopenia, and 2 patients had severe COVID-19 with normal lymphocyte counts, and high levels of IL-6. None of the patients exhibited an exacerbation of their underlying RD. In the literature, there were 9 studies of COVID-19 involving 197 cases of various inflammatory RD. Most patients were on DMARDs or biologics, of which TNFα inhibitors were most frequently used. Two tocilizumab users had a mild infection. Two patients were on rituximab with 1 severe COVID-19 requiring mechanical ventilation. Six patients were on secukinumab with 1 hospitalization. Of the total 201 cases, 12 died, with an estimated mortality of 5.9%

Conclusion

Patients with RD are susceptible to COVID-19. Various DMARDs or biologics may affect the viral disease course differently. Patients on hydroxychloroquine, TNFα antagonists or tocilizumab may have a mild viral illness. Rituximab or secukinumab could worsen the viral disease. Further study is warranted.

Keywords: COVID-19, Rheumatic disease, DMARDs, Biologics, SARS CoV-2

Introduction

Coronavirus 2019 (COVID-19) caused by severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2 (SARS CoV-2) has been declared a global pandemic since March 2020. This viral outbreak has raised serious concerns among the public and patients with health conditions. In the medical community, Rheumatologists are particularly concerned because their patients represent a population of autoimmune rheumatic disorders who are mostly on immunosuppressive agents and are susceptible to infection. While much has been learnt on COVID-19 in general, little is known of COVID-19 severity and outcomes in patients with rheumatic diseases (RD). Herein, in conjunction with the literature review, we report a case series of patients with RD, who were infected with COVID-19

Patients and methods

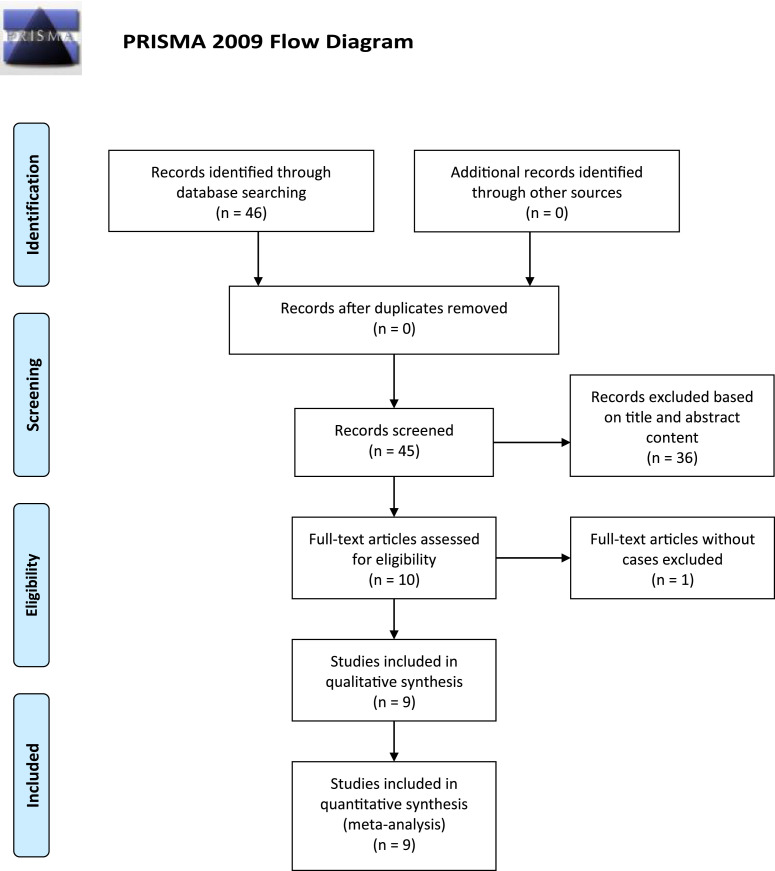

A retrospective chart review was conducted in 4 hospitalized patients at Stony Brook University Hospital between early March 2020 and the end of April 2020, including 2 cases that we previously published in the Rheumatologist. These patients had underlying RD on disease modifying anti-rheumatic drugs (DMARDs) prior to developing COVID-19. In our patients, a diagnosis of COVID-19 was made based on clinical grounds and by polymerase chain reaction of samples from nasopharyngeal swabs. In addition, a literature search of PubMed, Scopus, and Web of Science databases was conducted between December 2019 and May 2, 2020 using the terms: “COVID-19” and “rheumatic disease” or “biologic”. The search process and result are depicted in PRISMA (Fig. 1 ). English language articles that reported single case or case series of COVID-19 in RD were reviewed. Relevant information such as demographic, clinical, therapeutic data, and outcomes of these patients were gathered from the literature. Other relevant literature regarding the virus (SARS), immune response, and cytokine storm, were also searched between 1990 and May 2, 2020. Descriptive statistics was used.

Fig. 1.

PRISMA depicts the literature search process and result.

Results

-

1

Our data of a case series of COVID-19 in RD

The demographic, clinical, and therapeutic data of 4 cases from our hospital are summarized (Table 1 ). Of the 4 COVID-19 hospitalized patients with RD, there were 2 men and 2 women with mean age of 57 ± 21 years. The most common symptoms among all 4 patients were fever and cough. Of the 4 patients, 2 patients had a mild infection, and the other 2 developed severe COVID-19 related respiratory complications, including 1 Ankylosing Spondylitis (AS) patient on secukinumab requiring mechanical ventilation and 1 Granulomatous with Polyangiitis (GPA) patient with underlying lung involvement on rituximab, who developed superimposed viral pneumonia requiring supplemental oxygenation. All 4 patients had elevated acute phase reactants, 2 patients had mild COVID-19 with lymphopenia, and 2 patients had severe infection with normal lymphocyte counts and high levels of interleukin (IL)-6. None of the patients exhibited an exacerbation of their underlying RDs. The lupus patient had normal complement levels and negative anti-double stranded DNA antibodies. In this case, acute worsening on chronic renal insufficiency was thought to be secondary to dehydration from diarrhea. The GPA patient did not show disease flare as evidenced by stable renal function and negative antineutrophil cytoplasmic antibody.

Table 1.

Relevant demographic,clinical and laboratory data of four inpatients with COVID-19 from Our Hospital.

| Case 1* | Case 2* | Case 3 | Case 4 | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Demographics | Age | 76 | 78 | 49 | 27 |

| Gender | Female | Male | Male | Female | |

| Ethnicity | White | White | Black | Hispanic | |

| Clinical data | Medications | Olmesartan, metoprolol omeprazole nortriptyline |

Amlodipine hydrochlorothiazide losartan nortriptyline levothyroxine rosuvastatin tamsulosin |

Prednisone and mycophenolate mofetil until 2019 |

Prednisone Bactrim famotidine |

| DMARDs | MTX | HCQ | |||

| Biologic | Etanercept | Secukinumab | Rituximab | ||

| RD | RA | AS | SLE | GPA | |

| Symptoms at onset | Mild fever, dry cough, and headache | High fever, severe dry cough and SOB, myalgias, HA. |

Watery diarrhea, associated with low grade fever, chills, and myalgia | Fever, dry cough, SOB | |

| Chest X-ray/Chest CT | Clear | Bilateral diffuse opacities on X-ray Groundglass opacities on CT |

Chronic reticular changes consistent with ILD | Bilateral multifocal opacities on X-ray | |

| Hospital Days | 6 | 75 (remains hospitalized) | 12 | 19 | |

| Management of COVID-19 | Supportive Care | HCQ, Azithromycin Mechanical Ventilation |

Supportive Care | HCQ and Azithromycin Tocilizumab 400mg once Supplemental oxygen via non-rebreather 15L |

|

| Laboratory Data | Reference Range | ||||

| Platelet | 150,000–450,000 mm³ | 147,000 | 141,000 | 333,000 | 411,000 |

| Lymphocyte | 900–4,800 mm³ | 250 | 1,150 | 750 | 1600 |

| Sodium | 135–146mmol | 125 | 133 | 139 | 134 |

| C-reactive Protein | 0–0.5 mg/dL | 1.2 | 11.7 | 1.1 | 10 |

| Erythrocyte sedimentation rate | 0–30 mm/hour | 11 | 54 | 121 | 108 |

| LDH | 94-250 IU/L | 228 | 611 | 443 | 574 |

| Ferritin | 15-150 ng/mL | NA | 843 | 965.2 | 1601 |

| D-Dimer | > 230 ng/mL | 195 | 246 | 2821 | 435 |

| IL-6 | >14.8pg/mL | 12.8 | 109.6 | NA | 150 |

| Procalcitonin | <0.10ng/mL | 0.05 | 0.58 | 0.91 | 0.12 |

aDMARDs, disease modifying anti-rheumatic drugs; RD, Rheumatic Disease; RA, Rheumatoid Arthritis; AS, Ankylosing Spondylitis; SLE, Systemic Lupus Erythematosus; GPA, Granulomatous with Polyangiitis; MTX, methotrexate; HCQ, hydroxychloroquine; CT, computerized tomography; ILD Interstitial lung disease,; SOB, shortness of breath; IL-6, interleukin-6; LDH, Lactate Dehydrogenase;

b *Case 1 and Case 2 were published by us in the Rheumatologist 2020, April

Case description

Case 1

A 76-year-old Caucasian woman with Rheumatoid Arthritis (RA) since 2006 presented in March 2020 with complaints of low-grade fevers, minimal dry cough, and headaches of one-week duration. She had been on etanercept 50 mg weekly and methotrexate (MTX) 10 mg weekly for more than 10 years. Additional comorbidities and medications are outlined in Table 1. Laboratory values including erythrocyte sedimentation rate, C-reactive protein, IL-6, and lung imaging studies were normal. A nasopharyngeal swab obtained on admission was positive for SARS-CoV-2 by polymerase chain reaction (PCR) (Viracor Eurofins, Lee's Summit, Mo.). Her viral symptoms quickly abated without special treatment. She did not receive methotrexate or etanercept during the hospitalization.

Case 2

A 78-year-old Caucasian man presented to our hospital with high fevers (38.9° C) and severe dry cough for the previous 24 hours, along with fatigue, myalgias, shortness of breath, frontal headaches, and lightheadedness, in March 2020. His medical history was significant for AS, for which he received secukinumab 150 mg subcutaneous every four weeks for the previous 16 months. Other information such as comorbidities and medications are outlined in Table 1. On admission, his vital signs were temperature 38.2°C, respiration rate 22 breaths/minute, and blood pressure 179/78 mmHg, with pulse oximeter 98% on room air. The physical exam was within normal limits otherwise. His relevant laboratory findings are listed (Table 1). Despite initial normal chest X-ray, a chest CT performed on admission day 2 showed several small areas of groundglass opacities. On day 4, he had elevated inflammatory markers and worsening respiratory status requiring mechanical ventilation. He completed a five-day course of hydroxychloroquine and azithromycin. Secukinumab was not administered during the hospitalization. The patient had a prolonged hospital course and underwent tracheostomy. He continues to remain hospitalizaed.

Case 3

A 49-year-old African American man with SLE, lupus nephritis class III/V, and underlying interstitial lung disease (ILD) presented in April 2020 with worsening renal function and hyperkalemia necessitating urgent hemodialysis. The patient had had chronic kidney disease since 2017 and received high doses of prednisone and mycophenolate mofetil until 2019. He only took hydroxychloroquine (HCQ) 200 mg BID. The patient had 10 days of watery diarrhea associated with nausea, vomiting, and decreased oral intake without abdominal pain. He also had low-grade fevers, chills, and generalized myalgias three weeks ago. His vital signs were temperature 36.6 °C, blood pressure 147/89 mmHg, heart rate 133/min, and breathing rate 17/min, with SO2 100% on room air. Physical examination showed tachycardia but was otherwise normal. He tested positive for SARS-CoV-2 and did not receive special treatment except hemodialysis. He was discharged home after 11 days of hospitalization.

Case 4

A 27-year-old Hispanic woman with a diagnosis of GPA two months ago presented with fevers, severe dry cough, and shortness of breath in April 2020. She was treated with high dose steroids and four weekly infusions of Rituximab 2 months ago. Her GPA had been stabilized and she was on prednisone 30mg daily. On presentation, she was tachycardic and tachypneic with respiration rate 44/min and oxygen saturation of 75% on room air, with improvement upon being placed on 100% non-rebreather. Physical exam demonstrated bilateral decreased breath sounds that correlated with chest radiography findings of bilateral multifocal opacities. Laboratory evaluation revealed elevated inflammatory markers (Table 1). She tested positive for SARS-CoV-2 and received 5-day course of HCQ. However, due to poor clinical improvement, she subsequently received one dose of Tocilizumab 400 mg before her inflammatory markers and oxygen requirement improved. She did not require mechanical ventilation.

-

1

Literature data of COVID-19 in RD

The clinical data and outcomes of published cases are summarized (Table 2 ). Through the literature search, we identified 9 separate studies of COVID-19 in RD, including 4 single cases ([1], [2], [3], [4]) and 5 case series ([5], [6], [7], [8], [9]). These studies involved 197 cases of various inflammatory RD. Most patients were on conventional and/or biologic DMARDs. The most frequently used DMARDs were tumor necrosis factor (TNF)α inhibitors among the patients. There were 2 cases of RD on rituximab, 1 with GPA having severe COVID-19 requiring mechanical ventilation; the patient received HCQ and lopinavir/ritonavir. The other patient with RA had clinical improvement after receiving HCQ/azithromycin/lopinavir-ritonavir/tocilizumab, and supplemental oxygen. There were 2 tocilizumab users including 1 Systemic Sclerosis patient who was treated at home and 1 RA patient on MTX and HCQ requiring supplemental oxygen, who was discharged 6 days later. Of the 6 secukinumab users, 5 were treated at home, while 1 required hospitalization but was discharged 3 days later. Among the 17 SLE cases, there were 7 ICU admissions and 2 deaths. All patients were on HCQ and 7 were on immunosuppressive agents. The authors did not specify the medications used among those ICU or severe patients (7). In the Global Rheumatology Alliance registry of 110 cases, there were 19 SLE cases; however, their disease severity and DMARD use was not specified. In addition, there were 39 hospitalized patients and 9 deaths (9). In the New York University Langone Health group study of 59 confirmed cases of COVID-19, there were 45 outpatients and 14 inpatients. Of the hospitalized patients, there were 1 ICU patient who had hypertension, BMI >30, mild psoriatic arthritis, and was on MTX prior to infection and 1 death who had coronary artery disease, BMI>40, and severe psoriasis. The remaining patients had mild viral disease course. Based on the total number of the literature cases plus our 4 cases, we estimated the mortality was 5.9% (12/201) among COVID-19 patients with RD.

Table 2.

Literature data of COVID-19 in rheumatic disease.

| Authors | COVID-19 case no. | Rheumatic disease | DMARD/Biologic | COVID-19 outcome |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Mihai, et al | 1 | SSc | Tocilizumab | Mild, treated as outpatient |

| Duret, et al | 1 | Axial SpA | Etanercept | Mild but required hospitalization |

| Moutsopoulos | 1 | CAPS | Canakinumab | Mild, treated as outpatient |

| Guilpain, et al | 1 | GPA | Rituximab | Severe, requiring ICU admission. treated with lopinavir/ritonavir for 3 days HCQ for 10 days Extubated day 20 Discharged home day 29 |

| Favalli, et al | 3 | Sarcoidosis Axial SpA PsA |

Adalimumab Secukinumab Secukinumab |

Mild |

| Monti, et al | 4 | RA | Etanercept 2 Tofacitinib Abatacept |

Mild |

| Mathian, et al | 17 | SLE | All on HCQ 7 on other immunosuppressants but not specified. |

14 hospitalized 7 ICU 2 deaths |

| Haberman, et al | 59 | Psoriasis 7 PsA 14 RA17 UC 10 CD 12 AS 6 |

Apremilast 1 Azathioprine 1 Hydroxychloroquine 7 Leflunomide 1 Mesalamine 5 Methotrexate 14 NSAIDs 2 Prednisone 7 Sulfasalazine 1 Adalimumab 11 Certolizumab 2 Etanercept 4 Guselkumab 1 Infliximab 10 Ixekizumab 1 Rituximab 1 Secukinumab 4 Tocilizumab 1 Tofacitinib 4 Ustekinumab 2 |

45 outpatients 14 hospitalized 13 treated on regular floor 1 ICU 1 death |

| Gianfrancesco, et al | 110 | RA 40 PsA 19 SLE 19 Axial SpA 7 Vasculitis 7 Sjogren syndrome 5 Other 17 |

Conventional DMARDs 69 Biologics 49 JAK inhibitor 5 NSAIDs 28 Glucocorticoids 27 Other 5 |

39 hospitalized 9 deaths |

cDMARDs, disease modifying anti-rheumatic drugs; RD, Rheumatic Disease; RA, Rheumatoid Arthritis; PsA, Psoriatic Arthritis; Axial SpA, Axial Spondyloarthropathy; AS, Ankylosing Spondylitis; CD, Crohn's disease; UC, Ulcerative Colitis; SLE, Systemic Lupus Erythematosus; GPA, Granulomatous with Polyangiitis; CAPS, Cryopyrin-associated periodic syndrome; HCQ, hydroxychloroquine; NSAIDs, Nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs; JAK inhibitor, Janus kinase inhibitors.

Discussion

During the ongoing COVID-19 pandemic, both healthy individuals and patients with chronic conditions can be infected. We present a cases series of patients with RD, who developed COVID-19. Both our case study and the literature data indicate that patients with systemic autoimmune diseases, particularly those on DMARDs, are susceptible to COVID-19 with an estimated mortality of 5.9%.

Interestingly, we find that these patients in the current study had different clinical outcomes in terms of COVID-19 severity and related complications. For example, both the lupus patient on HCQ and RA patient on etanercept developed mild viral symptoms. The GPA patient on rituximab developed pneumonia requiring supplemental oxygenation via nonrebreather. The AS patient on secukinumab required mechanical ventilation. These two patients with severe disease had significantly higher serum levels of IL-6 that has been shown to correlate with severe COVID-19 and its related disease (10). To address the question of why these patients had different outcomes of the viral illness, several factors need to be considered, including underlying RD, age, gender, comorbidities, DMARD use, as well as the pathogenesis of COVID-19, among others.

Our analysis of these 4 cases has indicated that different DMARDs may affect the COVID-19 course and prognosis differently. To explain the potential effects of various DMARDs, we will first discuss the immunologic mechanisms of COVID-19.

SARS CoV2 is an enveloped RNA virus that consists of four primary structural proteins including a spike (S) glycoprotein, small envelope (E) glycoprotein, membrane (M)glycoprotein, and nucleocapsid (N) protein, along with several accessory proteins (11). The S glycoprotein binds to angiotensin converting enzyme 2 (ACE2), a receptor on cell membranes, followed by fusion of the viral membrane and host cell (12, 13). The cellular serine protease, TMPRSS2, is also required to properly process the SARS-CoV-2 spike protein and facilitate host cell entry (14). The virus entry initially triggers the innate immune response, where Pattern Recognition Receptors (PRR) such as Toll-like receptors (TLRs) recognize pathogen associated molecular patterns (PAMP). The PAMP may be nucleic acids, glycoproteins, lipoproteins and other small molecules that are found in the structural components of viruses. This in turn induces a release of proinflammatory cytokines, which activate transcription factors and JAK-STAT pathways, further releasing a number of proinflammatory cytokines, such as IL-1β, IL-6, interferon (IFN)-γ, IFN-α, TNFα, other cytokines and chemokines. This hyperinflammation can lead to cytokine storm (15). The virus also activates the adaptive immune response, where activated Th1 cells can stimulate cytotoxic CD8+ T cells to destroy virally infected cells. Meanwhile, Th1 cells activate and stimulate B cells to produce antigen-specific antibodies (16, 17). Despite this defense mechanism, like the 2002 SARS-CoV, these viruses have the ability to evade the immune system (18, 19), thus making the development of effective drugs more challenging.

It is reported that a subgroup of COVID-19 patients(15%) developed severe infection and life-threatening complications, in which hyperinflammatory responses or cytokine storm are involved (20). Cytokine storm is defined as a syndrome of excessive immune activation and proliferation of T lymphocytes and macrophages with hypersecretion of proinflammatory cytokines. These mediators include interleukin IL-1β, IL-6, IFN-γ, and TNFα ([21], [22], [23]). Huang et al. described a similar cytokine profile in their patients with COVID-19 and cytokine storm (24). Th17 cells and IL-17 are also involved in the cytokine storm response (25). With what has been learned on the role of cytokine storm, it will be important to use that information to guide and formulate a therapeutic strategy for severe COVID-19 patients. Henderson et. al recently suggested to monitor COVID-19 patients as early as possible with such biometrics as cytopenia, fibrinogen, lactate dehydrogenase, hepatic transaminases, elevated ferritin, CD25, and IL-6 for cytokine storm. They also summarized treatment regimens for cytokine storm in general and their potential utility in severe COVID-19 (26). Among them are IL-6 and IL-1β inhibitors which have been successfully used in alleviating cytokine storm secondary to certain systemic inflammatory RDs ([27], [28], [29], [30]). Tocilizumab, an IL-6 receptor antagonist, has been studied in COVID-19 patients with some success. A study of severe to critical COVID-19 patients in China has shown improved outcome in 15 out of 20 patients (31). Preliminary data from a French study also has provided promising results (32), An Italian prospective open, single-arm, multicenter study of 63 hospitalized adult patients with severe COVID-19 has demonstrated improvement in respiratory and laboratory parameters (33). According to the literature data in our study, two RD patients on tocilizumab developed mild COVID-19 infection, supporting the positive role of IL-6 antagonist. There are still several ongoing clinical trials to investigate the potential role of interleukin antagonists, particularly IL-6 and IL-1β, in the treatment of severe COVID-19 ([34], [35], [36], [37], [38], [39], [40]). JAK inhibitors which indirectly block IL-6 are also being studied in treating this infection ([41], [42], [43], [44]). For a full consideration of using anti-cytokine storm to treat this viral disease, other agents to inhibit the inflammatory mediators may need to be explored. Therefore, it is worthwhile to investigate whether other biologics may have influences in the clinical course of the COVID-19 related respiratory and other complications.

In the present study, our RA patient on etanercept developed mild COVID-19 without complications. Similarly, in the published studies 7 cases were on etanercept and developed mild symptoms, although some patients were hospitalized. Etanercept is a TNFα receptor II antagonist which is known to be associated with a high rate of infections. Unexpectedly, it did not lead to severe COVID-19 in our patient and literature cases, perhaps due to its inhibition of TNFα, a cytokine involved in the viral disease cytokine storm. According to the literature data in our study, TNFα inhibitors including etanercept, adalimumab and infliximab were more frequently used in RD patients, and they seemed to have less severity of the viral illness. TNFα has been reported to be present in the blood and disease tissues of patients with COVID-19 (45). Additionally, it is possible that pretreatment with etanercept could have resulted in a blunted IL-6 response indirectly. In an in vitro study, IL-6 and TNFα were up-regulated by the recombinant S protein of the 2002 SARS-CoV suggesting that TNFα or IL-6 antagonists may potentially reduce the cytokine storm in COVID-19 and its related lung damage (46). These data together suggest that TNFα antagonist may be considered as a treatment strategy for severe COVID-19 in the future.

In case 2, the AS patient developed severe virus-related complications. It is unclear whether secukinumab, a monoclonal antibody to IL-17A, could play a negative role in the case. This is contrasting to an autopsy study of COVID-19 infected cases, which suggested a pathogenic role of Th17 and potential benefit of blocking Th17 (25). In addition, 5 out of the 6 RD patients on secukinumab from the literature data in the current study developed mild COVID-19, and 1 was hospitalized. These data indicate that IL-17A inhibitors influence the viral disease course.

Our patient with SLE had minimal viral symptoms without worsening of his underlying ILD. In an in vitro study, HCQ has been shown to inhibit endosome-lysosome system acidification and to suppress proinflammatory cytokines (47). HCQ is currently being studied in multiple clinical trials ([48], [49], [50], [51], [52], [53], [54], [55], [56], [57], [58], [59], [60]). However, the therapeutic efficacy of HCQ in COVID-19 remains controversial. While some studies showed benefit (47), other studies produced mixed results. Chowdhury et. al surveyed recent literature on clinical trials involving HCQ and Chloroquine. They found 5/7 completed clinical trials showed favorable outcomes, whereas 2/7 trials showed no change compared to control (61). In a French case series of lupus, which was included in our study, HCQ was found to have variable outcomes in the treatment of COVID-19 and its complications (7). Another observational study at the Veterans Affairs hospital showed no benefit of HCQ in severe COVID-19 (62). Although HCQ has been used to treat COVID-19, its efficacy will need to be confirmed by the results of the ongoing clinical trials.

Our GPA patient was treated with Rituximab, a monoclonal antibody to CD20, prior to being infected. This drug may have reduced her humoral immune response leading to a more severe disease course. In a prospective study of 200 subjects infected with human coronaviruses, neutralizing antibody has been shown to play a protective role by limiting the infection at a later phase and to prevent re‐infection in the future (63). SARS-CoV infection induces IgG production against N protein, which can be detected in serum as early as day 4 after the onset of disease and with most patients being seroconverted by day 14 (64, 65). Hence, B-cell depletion with Rituximab may have altered the antibody response making the patient more vulnerable to the infection. Additionally, SARS-CoV has also been shown to decrease T lymphocytes in 65 patients. Glucocorticoid administration contributed to further decrease in lymphocyte counts (66). As a result, these together hinder the host's ability to adequately respond to the infection. Similarly, the published case of GPA on Rituximab in the current study also developed severe COVID-19 requiring mechanical ventilation (2). Taken together, these findings suggest that pretreatment with Rituximab, particularly with glucocorticoids, could contribute to a more severe COVID-19 infection and poor outcome.

In summary, RD patients are susceptible to COVID-19. Various DMARDs may affect the viral process differently. Patients on etanercept, HCQ, or tocilizumab may run a mild course of the viral illness. Rituximab or secukinumab could worsen the viral disease and its related complications. Our study may help in formulating a guideline in the future concerning immunosuppressive use in RD patients during COVID-19. Given the small sample size in the study as a limitation, further study by expanding cases is warranted.

Funding

No specific funding was received from any bodies in the public, commercial or not-for-profit sectors to carry out the work described in this article.

Declaration of Competing Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

Footnotes

Clinical Significance: Patients with rheumatic disease are susceptible to COVID-19. DMARDs may influence the viral disease course differently.

Supplementary material associated with this article can be found in the online version at doi:10.1016/j.semarthrit.2020.05.010.

Appendix. Supplementary materials

References

- 1.Duret PM, Sebbag E, Mallick A, Gravier S, Spielmann L, Messer L. Recovery from COVID-19 in a patient with spondyloarthritis treated with TNF-alpha inhibitor etanercept. Ann Rheum Dis. 2020. Apr 30 doi: 10.1136/annrheumdis-2020-217362. pii: annrheumdis-2020-217362[Epub ahead of print] [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Guilpain P, Le Bihan C, Foulongne V, Taourel P, Pansu N, Maria ATJ. Rituximab for granulomatosis with polyangiitis in the pandemic of covid-19: lessons from a case with severe pneumonia. Ann Rheum Dis. 2020 doi: 10.1136/annrheumdis-2020-217549. Ann Rheum Dis. 2020 Apr 20. pii: annrheumdis-2020-217549[Epub ahead of print] [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Mihai C, Dobrota R, Schroder M, Garaiman A, Jordan S, Becker MO. COVID-19 in a patient with systemic sclerosis treated with tocilizumab for SSc-ILD. Ann Rheum Dis. 2020. May;79(5):668–669. doi: 10.1136/annrheumdis-2020-217442. Epub 2020 Apr 2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Moutsopoulos HM. Anti-inflammatory therapy may ameliorate the clinical picture of COVID-19. Ann Rheum Dis. 2020. Apr 28 doi: 10.1136/annrheumdis-2020-217562. pii: annrheumdis-2020-217562[Epub ahead of print] [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Favalli EG, Ingegnoli F, Cimaz R, Caporali R. What is the true incidence of COVID-19 in patients with rheumatic diseases? Ann Rheum Dis. 2020. Apr 22 doi: 10.1136/annrheumdis-2020-217615. pii: annrheumdis-2020-217615[Epub ahead of print] [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Monti S, Balduzzi S, Delvino P, Bellis E, Quadrelli VS, Montecucco C. Clinical course of COVID-19 in a series of patients with chronic arthritis treated with immunosuppressive targeted therapies. Ann Rheum Dis. 2020;79(5):667–668. doi: 10.1136/annrheumdis-2020-217424. 2020 MayEpub 2020 Apr 2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Mathian A, Mahevas M, Rohmer J, Roumier M, Cohen-Aubart F, Amador-Borrero B. Clinical course of coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) in a series of 17 patients with systemic lupus erythematosus under long-term treatment with hydroxychloroquine. Ann Rheum Dis. 2020. Apr 24 doi: 10.1136/annrheumdis-2020-217566. pii: annrheumdis-2020-217566[Epub ahead of print] [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Haberman R, Axelrad J, Chen A, Castillo R, Yan D, Izmirly P. Covid-19 in immune-mediated inflammatory diseases - case series from New York. N Engl J Med. 2020. Apr 29 doi: 10.1056/NEJMc2009567. [Epub ahead of print] [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Gianfrancesco MA, Hyrich KL, Gossec L, Strangfeld A, Carmona L, Mateus EF. Rheumatic disease and COVID-19: initial data from the COVID-19 global rheumatology alliance provider registries. Lancet Rheumatol. 2020. Apr 16 doi: 10.1016/S2665-9913(20)30095-3. [Epub ahead of print] [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Aziz M, Fatima R, Assaly R. Elevated interleukin-6 and severe COVID-19: a meta-analysis. J Med Virol. 2020 doi: 10.1002/jmv.25948. J Med Virol. 2020 Apr 28[Epub ahead of print] [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Jiang S, Hillyer C, Du L. Neutralizing antibodies against SARS-CoV-2 and other human coronaviruses. Trends Immunol. 2020. Apr 2 doi: 10.1016/j.it.2020.03.007. pii: S1471-4906(20)30057-0[Epub ahead of print] [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Hoffmann M, Kleine-Weber H, Schroeder S, Kruger N, Herrler T, Erichsen S. SARS-CoV-2 cell entry depends on ACE2 and TMPRSS2 and is blocked by a clinically proven protease inhibitor. Cell. 2020;181(2):271–280. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2020.02.052. e8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Walls AC, Park YJ, Tortorici MA, Wall A, McGuire AT, Veesler D. Structure, function, and antigenicity of the SARS-CoV-2 Spike glycoprotein. Cell. 2020;181(2):281–292. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2020.02.058. e6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Tay MZ, Poh CM, Renia L, MacAry PA, Ng LFP. The trinity of COVID-19: immunity, inflammation and intervention. Nat Rev Immunol. 2020. Apr 28 doi: 10.1038/s41577-020-0311-8. [Epub ahead of print] [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Li G, Fan Y, Lai Y, Han T, Li Z, Zhou P. Coronavirus infections and immune responses. J Med Virol. 2020;92(4):424–432. doi: 10.1002/jmv.25685. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Rabi FA, Al Zoubi MS, Kasasbeh GA, Salameh DM, Al-Nasser AD. SARS-CoV-2 and coronavirus disease 2019: what we know so far. Pathogens. 2020;9(3) doi: 10.3390/pathogens9030231. pii: E231. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Li X, Geng M, Peng Y, Meng L, Lu S. Molecular immune pathogenesis and diagnosis of COVID-19. J Pharm Anal. 2020. Mar 5 doi: 10.1016/j.jpha.2020.03.001. [Epub ahead of print] [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Totura AL, Baric RS. SARS coronavirus pathogenesis: host innate immune responses and viral antagonism of interferon. Curr Opin Virol. 2012;2(3):264–275. doi: 10.1016/j.coviro.2012.04.004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Astuti I, Ysrafil Severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2 (SARS-CoV-2): an overview of viral structure and host response. Diabetes Metab Syndr. 2020;14(4):407–412. doi: 10.1016/j.dsx.2020.04.020. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Mehta P, McAuley DF, Brown M, Sanchez E, Tattersall RS, Manson JJ. COVID-19: consider cytokine storm syndromes and immunosuppression. Lancet. 2020;395(10229):1033–1034. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(20)30628-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.McGonagle D, Sharif K, O'Regan A, Bridgewood C. The role of cytokines including interleukin-6 in COVID-19 induced pneumonia and macrophage activation syndrome-like disease. Autoimmun Rev. 2020 doi: 10.1016/j.autrev.2020.102537. Apr 3:102537[Epub ahead of print] [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Behrens EM, Review Koretzky GA. Cytokine storm syndrome: looking toward the precision medicine era. Arthritis Rheumatol. 2017;69(6):1135–1143. doi: 10.1002/art.40071. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Kostik MM, Dubko MF, Masalova VV, Snegireva LS, Kornishina TL, Chikova IA. Identification of the best cutoff points and clinical signs specific for early recognition of macrophage activation syndrome in active systemic juvenile idiopathic arthritis. Semin Arthritis Rheum. 2015;44(4):417–422. doi: 10.1016/j.semarthrit.2014.09.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Huang C, Wang Y, Li X, Ren L, Zhao J, Hu Y. Clinical features of patients infected with 2019 novel coronavirus in Wuhan, China. Lancet. 2020;395(10223):497–506. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(20)30183-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Wu D, Yang XO. TH17 responses in cytokine storm of COVID-19: an emerging target of JAK2 inhibitor fedratinib. J Microbiol Immunol Infect. 2020. Mar 11 doi: 10.1016/j.jmii.2020.03.005. pii: S1684-1182(20)30065-7[Epub ahead of print] [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Henderson LA, Canna SW, Schulert GS, Volpi S, Lee PY, Kernan KF. On the alert for cytokine storm: immunopathology in COVID-19. Arthritis Rheumatol. 2020. Apr 15 doi: 10.1002/art.41285. [Epub ahead of print] [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Grom AA, Horne A, De Benedetti F. Macrophage activation syndrome in the era of biologic therapy. Nat Rev Rheumatol. 2016;12(5):259–268. doi: 10.1038/nrrheum.2015.179. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Ruperto N, Brunner HI, Quartier P, Constantin T, Wulffraat N, Horneff G. Two randomized trials of canakinumab in systemic juvenile idiopathic arthritis. N Engl J Med. 2012;367(25):2396–2406. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1205099. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.De Benedetti F, Brunner HI, Ruperto N, Kenwright A, Wright S, Calvo I. Randomized trial of tocilizumab in systemic juvenile idiopathic arthritis. N Engl J Med. 2012;367(25):2385–2395. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1112802. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Monteagudo LA, Boothby A, Gertner E. Continuous Intravenous anakinra infusion to calm the cytokine storm in macrophage activation syndrome. ACR Open Rheumatol. 2020. Apr 8 doi: 10.1002/acr2.11135. [Epub ahead of print] [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Xu X, Han M, Li T, Sun W, Wang D, Fu B. Effective treatment of severe COVID-19 patients with tocilizumab. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2020. Apr 29 doi: 10.1073/pnas.2005615117. pii: 202005615[Epub ahead of print] [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Genentech's arthritis drug tocilizumab shows promise in Covid-19 trial[Available from:https://www.clinicaltrialsarena.com/news/french-early-trial-tocilizumab-covid-19/.

- 33.Sciascia S, Apra F, Baffa A, Baldovino S, Boaro D, Boero R. Pilot prospective open, single-arm multicentre study on off-label use of tocilizumab in severe patients with COVID-19. Clin Exp Rheumatol. 2020. May 1 [Epub ahead of print] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Study to evaluate the efficacy and safety of tocilizumab versus corticosteroids in hospitalised COVID-19 patients with high risk of progression[Available from:https://ClinicalTrials.gov/show/NCT04345445.

- 35.Study of efficacy and safety of canakinumab treatment for CRS in participants with COVID-19-induced Pneumonia[Available from:https://ClinicalTrials.gov/show/NCT04362813.

- 36.Treatment of COVID-19 patients with anti-interleukin drugs[Available from:https://ClinicalTrials.gov/show/NCT04330638.

- 37.Tocilizumab to prevent clinical decompensation in hospitalized, non-critically Ill patients with COVID-19 pneumonitis[Available from:https://ClinicalTrials.gov/show/NCT04331795.

- 38.Efficacy of early administration of Tocilizumab in COVID-19 patients[Available from:https://ClinicalTrials.gov/show/NCT04346355.

- 39.A study to evaluate the efficacy and safety of Tocilizumab in hospitalized participants with COVID-19 pneumonia[Available from:https://ClinicalTrials.gov/show/NCT04372186.

- 40.A study to investigate intravenous Tocilizumab in participants with moderate to severe COVID-19 pneumonia[Available from:https://ClinicalTrials.gov/show/NCT04363736.

- 41.Stebbing J, Phelan A, Griffin I, Tucker C, Oechsle O, Smith D. COVID-19: combining antiviral and anti-inflammatory treatments. Lancet Infect Dis. 2020;20(4):400–402. doi: 10.1016/S1473-3099(20)30132-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Safety and efficacy of Ruxolitinib for COVID-19[Available from:https://ClinicalTrials.gov/show/NCT04348071.

- 43.Safety and efficacy of Baricitinib for COVID-19[Available from: https://ClinicalTrials.gov/show/NCT04340232.

- 44.Ruxolitinib to combat COVID-19[Available from:https://ClinicalTrials.gov/show/NCT04354714.

- 45.Wang L, He W, Yu X, Hu D, Bao M, Liu H. Coronavirus disease 2019 in elderly patients: characteristics and prognostic factors based on 4-week follow-up. J Infect. 2020. Mar 30 doi: 10.1016/j.jinf.2020.03.019. pii: S0163-4453(20)30146-8[Epub ahead of print] [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Wang W, Ye L, Ye L, Li B, Gao B, Zeng Y. Up-regulation of IL-6 and TNF-alpha induced by SARS-coronavirus spike protein in murine macrophages via NF-kappaB pathway. Virus Res. 2007;128(1-2):1–8. doi: 10.1016/j.virusres.2007.02.007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Zhang W, Zhao Y, Zhang F, Wang Q, Li T, Liu Z. The use of anti-inflammatory drugs in the treatment of people with severe coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19): The Perspectives of clinical immunologists from China. Clin Immunol. 2020;214(Mar 25;214) doi: 10.1016/j.clim.2020.108393. [Epub ahead of print] [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Multi-site adaptive trials using hydroxycholoroquine for COVID-19[Available from:https://ClinicalTrials.gov/show/NCT04370262.

- 49.The university of the Philippines hydroxychloroquine PEP against COVID-19 trial[Available from:https://ClinicalTrials.gov/show/NCT04364815.

- 50.Hydroxychloroquine vs. Azithromycin for hospitalized patients with suspected or confirmed COVID-19[Available from:https://ClinicalTrials.gov/show/NCT04329832.

- 51.Hydroxychloroquine and nitazoxanide combination therapy for COVID-19[Available from:https://ClinicalTrials.gov/show/NCT04361318.

- 52.Efficacy of hydroxychloroquine, telmisartan and azithromycin on the survival of hospitalized elderly patients with COVID-19[Available from:https://ClinicalTrials.gov/show/NCT04359953.

- 53.Treating COVID-19 with hydroxychloroquine (TEACH)[Available from:https://ClinicalTrials.gov/show/NCT04369742.

- 54.Hydroxychloroquine for the treatment of mild COVID-19 Disease[Available from:https://ClinicalTrials.gov/show/NCT04340544.

- 55.High-dose Hydroxychloroquine for the treatment of ambulatory patients with mild COVID-19[Available from:https://ClinicalTrials.gov/show/NCT04351620.

- 56.Hydroxychloroquine vs. Azithromycin for outpatients in Utah with COVID-19[Available from:https://ClinicalTrials.gov/show/NCT04334382.

- 57.Hydroxychloroquine in the prevention of COVID-19 infection in healthcare workers[Available from:https://ClinicalTrials.gov/show/NCT04333225.

- 58.Hydroxychloroquine and azithromycin as prophylaxis for healthcare workers dealing with COVID19 patients[Available from:https://ClinicalTrials.gov/show/NCT04354597.

- 59.Chloroquine, hydroxychloroquine or only supportive care in patients admitted with moderate to severe COVID-19[Available from:https://ClinicalTrials.gov/show/NCT04362332. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 60.Hydroxychloroquine for the treatment of patients with mild to moderate COVID-19 to prevent progression to severe infection or death[Available from:https://ClinicalTrials.gov/show/NCT04323631.

- 61.Chowdhury MS, Rathod J, Gernsheimer J. A rapid systematic review of clinical trials utilizing chloroquine and hydroxychloroquine as a treatment for COVID-19. Acad Emerg Med. 2020. May 2 doi: 10.1111/acem.14005. [Epub ahead of print] [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Magagnoli J, Narendran S, Pereira F, Cummings T, Hardin JW, Sutton SS. Outcomes of hydroxychloroquine usage in United States veterans hospitalized with Covid-19. medRxiv. 2020 doi: 10.1101/2020.04.16.2006592063. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Gorse GJ, Donovan MM, Patel GB. Antibodies to coronaviruses are higher in older compared with younger adults and binding antibodies are more sensitive than neutralizing antibodies in identifying coronavirus-associated illnesses. J Med Virol. 2020;92(5):512–517. doi: 10.1002/jmv.25715. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Liu W, Fontanet A, Zhang PH, Zhan L, Xin ZT, Baril L. Two-year prospective study of the humoral immune response of patients with severe acute respiratory syndrome. J Infect Dis. 2006;193(6):792–795. doi: 10.1086/500469. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Hsueh PR, Huang LM, Chen PJ, Kao CL, Yang PC. Chronological evolution of IgM, IgA, IgG and neutralisation antibodies after infection with SARS-associated coronavirus. Clin Microbiol Infect. 2004;10(12):1062–1066. doi: 10.1111/j.1469-0691.2004.01009.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Gu J, Gong E, Zhang B, Zheng J, Gao Z, Zhong Y. Multiple organ infection and the pathogenesis of SARS. J Exp Med. 2005;202(3):415–424. doi: 10.1084/jem.20050828. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.