Highlights

-

•

Arts based and aesthetic pedagogy is a necessary part of training in the creative arts therapies.

-

•

Aesthetic presence supports creative arts therapies pedagogy online and in-person.

-

•

Aesthetic presence enhances the Community of Inquiry online pedagogical framework.

-

•

Aesthetic presence supports accessibility principles of Universal Design for Learning.

-

•

Multi-sensory engagement attends to absence of a physical encounter and the ubiquity of multimedia.

Keywords: Art education, Aesthetic presence, Online learning, Community of inquiry, Universal design for learning, Creative arts therapies, Pedagogy

Abstract

Literature about the integral role of the arts in learning is widely available, but much less has been written about how the arts and aesthetics support education in the creative arts therapies, particularly in the online learning environment. This article introduces the concept of aesthetic presence within the Community of Inquiry pedagogical model in line with values espoused within a Universal Design for Learning framework. The authors contextualize this concept with examples of how attention to the use of aesthetic and multimedia strategies in the classroom and in the online learning environment may foster openness and connection, encourage flexibility, humor, critical thinking, and animate and facilitate conversations about emergent and emotionally difficult themes while increasing accessibility for different kinds of learners.

Introduction

We need to advance our understanding of the role of the arts and aesthetics in the education of creative arts therapists in person and online. A primary contribution of creative arts therapists, as compared to verbal psychotherapists, is that we create an aesthetic framework, embedded in a socio-cultural context, from which to explore and examine experience as it arises between the client as artist, art-making, and a witness, in reference to the client’s capacities to witness themselves, a group’s capacity to witness each other, and the therapist’s capacity to bear witness to what unfolds. We seek to facilitate aesthetic distance, an encounter within a representational realm that enables both emotional arousal and cognitive reflection (Landy, 1983). It follows, then, that the arts should play a formative role in training. This is particularly true in online learning environments where, given the absence of a physical encounter and the ubiquity of multimedia, attention to multisensory engagement would have particular relevance. In this article, we introduce the concept of aesthetic presence and discuss its importance in the education of creative arts therapists (CATs) with specific attention to the online learning environment. We begin with a synthesis of literature on the arts in education and online learning in the CATs. We then argue the relevance of aesthetic presence within a Community of Inquiry (COI) model of online learning design and pedagogy and connect this to values espoused with the Universal Design for Learning (UDL) framework, an inclusive approach to pedagogy that attends to the needs of different kinds of learners (CAST, 2018). We conclude with practical suggestions on how aesthetic presence may be enhanced in course design and instruction in the creative arts. While the recent coronavirus pandemic has forced us to make a rapid adjustment to how we teach and practice in the creative arts therapies, our hope is that these strategies may be useful going forward as we contend with course design, instruction and practice in blended in-person and online environments.

Literature review

Despite the marginal status of the arts in education, many have written about the role of arts in facilitating learning (Beardsley, 1958, 1975, 1982; Berleant, 1991; Clapp & Edwards, 2013; Croce, 1948; Dewey, 1896, 1934; Duke, 1988; Gardner, 1983, 1994, 1999; Garrison 1997; Goldberg & Phillips, 1992; Granger, 2006; Greene, 2001; Hausman, 2007; Jackson, 1998; Maslak, 2006; Munro, 1928; Sawyer, 2004; Simmons & Hicks, 2006; Shusterman, 1989, 2006, 2012; Webster & Wolfe, 2013). Some literature exists on the pedagogical use of the arts in the training of creative arts therapists (2015, 2017a, 2017b, Butler, 2015; Deaver, 2012; Gaines, Butler, & Holmwood, 2015; Knight & Matney, 2012; Landy, McLellan, & McMullian, 2005; Landy, Hodermarska, Mowers, & Perrin, 2012; McMullian & Burch, 2017; Young, 2012). Even less focuses on online education in the arts therapies (Beardall, Blanc, Cardillo, Karman, & Wiles, 2016; Blanc, 2018; Pilgrim et al., 2020; Sajnani et al., 2019).

Arts and aesthetics in education

The arts, including sound/music, movement/dance, drama/theatre, visual, literary, and media arts, offer teachers and students multiple forms of expression and facilitate skills in sensing, perceiving, observing, listening, thinking, problem-solving, and collaborating (Clapp & Edwards, 2013). The value of attending to the aesthetic dimension of pedagogy has been argued by Dewey (1934), suggesting that learning occurs through experience and that aesthetic encounters deepen reflection and integrate theory with practice. Dewey suggested the artist is able to “actively internalize, then externalize in their art, landscapes, events, relationships and ideas,” thus facilitating new insights and possibilities (quoted in Goldblatt, 2006, p. 18). The artist transfers values from one field of experience to another, attaches them to the objects of everyday life and by imaginative insight make these objects meaningful. Therefore, art, as symbolic of lived and potential experience continues to change with every interaction to offer multiple, contextual readings and perspectives. Dewey’s observations were reflected in contemporary and subsequent ideas about how people learn. For example, Jung described the concept of active imagination, where the verbal free association of ideas, images, and beliefs could be expressed in visualizations, written and spoken narratives, drawn and painted images. From a learning perspective, active imagination creates a bridge by allowing the unconscious mind to teach the conscious body by facilitating new relationships between latent ideas, feelings, and desires (Semetsky, 2012). Building on Dewey’s ideas, Bruner (1966) described a learning process that oscillates between enactive representation (doing), iconic representation (images of real situations), and symbolic representation. Working with the arts in education encourages socio-emotional engagement, integrates understanding, and fosters inquiry even in subjects that do not traditionally involve the arts. For example, Sutherland (2000) explored the ways in which the integration of arts and non-verbal methods into traditionally “core” classes such mathematics have helped to develop these skills. Furthermore, research in this area has demonstrated how symbolic, metaphoric, and poetic thinking shapes reasoning (Thibodeau & Boroditsky, 2011). As Webster and Wolfe (2013) wrote in a Harvard Education Review survey of the arts in education:

Aesthetic pedagogy allows students to create connections through imagining ideas and exploring how they relate to everything else one understands and feels. Such a ‘scenic’ appreciation is not a luxury which teachers may indulge in as ‘an extra,’ but rather we contend that these aesthetic aspects are essential for learning experiences in order to help assist students to make important connections. (p. 24)

Freire (1973) contributed significantly to how we understand the value of the arts in education through a critical lens. He described codification as the gathering of localized information and lived experience in order to create visual images of real situations that could then be used to catalyze dialogue and critical thinking. Boal (1979) extended Freire’s ideas through enactive learning wherein participants act out, replay, apply, and actively seek out, rather than passively receive, information as a means for learning and liberation. Lorde (1984) saw the arts, poetry specifically, as a liberatory epistemology of learning and unlearning, particularly for women, racialized people, and/or members of the queer community. As she wrote, “Poetry is not a luxury. It is a vital necessity of our existence […] Poetry is the way we help give name to the nameless so it can be thought. The farthest external horizons of our hopes and fears are cobbled by our poems, carved from the rock experiences of our daily lives” (Lorde, 1984, p. 37). Hooks (1994) has similarly written extensively about her use of expressive writing, storytelling, arts-based experiences, and consideration of the role of the body in the classroom, seeing education as a practice of affective and interpersonal freedom and transgression.

Universal design for learning

The arts have been used in order to engage with and more fully include different kinds of learners (Simmons & Hicks, 2006). Bloom’s (1956) widely used taxonomy of learning included an affective domain, and Gardner’s (1999) theory of multiple intelligences included musical-rhythmic, visual-spatial, and bodily-kinesthetic ways of knowing. Most recently, the Universal Design for Learning (UDL) framework calls attention to the relationship between emotion and learning and the domination of text in pedagogical materials. A UDL framework emphasizes the need for multiple means of engagement, expression, and representation so that students have various pathways “for accessing and comprehending information, for demonstrating what they know, and for increasing motivation and persistence” (UDL on Campus, n.d.). The arts support these goals by strengthening socio-emotional coping skills, and self-awareness so as to allow students to find the right personal balance of demands and resources, sustain effort, foster collaboration, and self-regulation (Farrington et al., 2019).

It is clear that the aesthetic dimension of learning engages a powerful mix of higher order thinking skills, imagination and creativity, self-regulated learning, interpersonal interaction, and affective, socio-emotional engagement. With the wealth of insight available on the importance of arts in education, it is imperative that we examine how the arts are integrated in the training of creative arts therapists where the arts are privileged as a way of sensing, knowing, regulating, and representing lived experience.

Arts-based pedagogy in the training of creative arts therapists

There is a small but growing literature on how the arts are utilized in the teaching and training of CATs, whether in person or online. Several have written about the essential nature of art making in art therapy education (Deaver, 2012; Gerber, 2006; Wix, 1996). Deaver and McAuliffe (2009) and Fish (2008) explored the use of art-making in supervision and internship training. Cahn (2000) specifically addressed the use of studio-based art therapy education. Julliard et al. (2000) discussed the use of arts-based evaluation in research education. Deaver’s (2012) mixed-methods study pointed to the personal and professional importance of the consistent use of the arts across the curriculum. In dance/movement therapy, dance has been explored as a source of knowledge (Capello, 2007), a method for the personal and embodied growth of trainees (2010, Federman, 2011; Payne, 2004), and as a way to expand an educator’s movement repertoire in order to strengthen their approach to teaching future dance/movement therapists (Young, 2012). In music therapy, the curriculum requires music therapy trainees to first learn a series of musical competencies in a primary instrument/voice, percussion skills, composition, and improvisation, and then practice applying these skills to a music therapy context (Goodman, 2011). Knight and Matney (2012, 2014) highlighted the value of teaching functional percussion skills through a simultaneous contextualization of these skills in a music therapy approach. These authors also pointed to the rarity of the term “pedagogy” in music therapy writing and suggest that there is a need for further research into the training of future music therapists due to the lack of empirical studies on the topic.

Butler (2015, 2017a, Butler, 2017b) has written about the use of drama exercises in drama therapy classrooms and asserts that such approaches are necessary in drama therapy education. His qualitative research pointed to the complexity of training students in therapeutic work without it becoming therapy, as well as the importance of learning through arts-based practice. He suggested that drama therapy education must engage students in “continual embodied reflective practice rather than a merely cognitive reflection” (p.113). Several have built on Landy’s (1982) four-part education model, suggesting additional ways to incorporate embodied and drama-based forms of learning (Landy et al., 2005), including the use of existing theatrical characters and monologues to learn about clinical diagnoses (McMullian & Burch, 2017), embodying clients and therapists in supervision (Landy et al., 2012), and weaving situated, psychodynamic, and enactive learning with experiential activities (Butler, 2017a).

Creative arts therapies and online learning

Only six publications to date are known to have explored teaching CATs online (Beardall et al., 2016; Blanc, 2018; LaGasse & Hickle, 2015; Pilgrim et al., 2020; Sajnani et al., 2019; Vega & Keith, 2012). Vega and Keith (2012) focused their research on the scope of online learning in music therapy courses and conducted the first in-depth study in the US. Their research revealed that many of the music therapy educators who were surveyed had received queries about online learning, suggesting a growing interest in the adaption of music therapy in online and distance settings. This initial survey research provided a snapshot of the state of online learning in music therapy and confirmed that, as of their publication date, no training program was offered fully online.

LaGasse and Hickle’s (2015) mixed methods study compared the perception of community and learning for music therapists in an online and residential graduate course. Their quantitative results found no significant difference in perceptions of community. Their qualitative data suggested that the presence of the instructor, peer interaction, and multiple online tools were important in creating a sense of community for those enrolled in the online course. Online students did have a statistically significant higher perception of learning score than their residential peers, which the researchers attribute to the online students having more experience in the field and thus more investment in the learning process. No qualitative or quantitative measures examined the role of music or aesthetics in perceptions of community or learning.

Beardall et al. (2016) outlined the development of a comprehensive hybrid low-residency training program for dance/movement therapists. The authors described their attempts to develop an “embodied online presence,” as a way for students and faculty to create and sustain a kinesthetic and affective presence online. They articulated the importance of creating opportunities for their dance/movement students to develop and trust their “bodily-felt sense” (p. 417) through a variety of explicit activities involving filmed and synchronous dance and movement exercises and assignments, as well as instructors’ “listening to and observing students’ verbal and non-verbal cues and responding sensitively” (p. 412). The authors spent a significant part of their article articulating their use of a range of synchronous and asynchronous tools for teaching, discussion, and assignments, which may be helpful for others interested in developing or improving online and hybrid learning options for CATs. Blanc’s (2018) phenomenological pilot study explored more deeply this concept of embodied presence for DMT hybrid students, finding importance in arts-based responses and layered engagement between movement, other arts responses, and cognitive learning. She provided a sample of these layered assignments and indicates the importance of further research into embodied presence and the use of the arts in creating meaningful online learning environments. Sajnani et al. (2019) wrote about one university’s transition to a hybrid delivery model for training in the expressive therapies. This chapter outlined best practices in online CATs pedagogy, synthesized in the acronym SPECTRAA which stands for Student-faculty contact; Prompt feedback; Effective use of technology; Communication of expectations; Time on task; Respect for diverse abilities and learning styles; Active learning; and Aesthetic and embodied presence.

The most recent publication, co-authored by Pilgrim et al. (2020), presented findings on the first low-residency drama therapy cohort at Lesley University. This phenomenological study explored this cohort’s experiences, finding that virtual methods for creating experiences of embodiment, connection, and relationship using a combination of technology and artistic expression were seen as critically important. The study also found that several students began to shift away from the dramatic medium during the online teaching components of the hybrid program. Furthermore, this study reported that the most substantial critiques of the program centered on some course instructors’ lack of relational presence and communication. We see this article as a contribution to addressing ways in which instructors might develop an aesthetic presence to support relationship building and artistry in their course design and instruction in order to mitigate the kinds of difficulties that students face in an online learning environment.

The community of inquiry framework: foundations and adaptations

A foundational model for conceptualizing a successful online learning experience has been theCommunity of Inquiry Model (COI) (Garrison, Anderson, & Archer, 2010). The COI model presents three “presences” required in a successful learning experience: teaching presence, cognitive presence, and social presence integrated seamlessly in an online environment (Garrison & Cleveland-Innes, 2005, p. 134). The COI model clarified the importance of the educational experience culminating in more than simply the mastery of content or cognitive engagement. It arose naturally to meet the challenge of creating a strong sense of community within a text-based environment (Garrison, Anderson, & Archer, 2001). What follows below is a brief overview of the teaching, social, and cognitive presences articulated by COI, as well as some of the critiques of this model.

Teaching presence

Teaching presence is the “design, facilitation, and direction of cognitive and social processes for the purpose of realizing personally meaningful and educationally worthwhile learning outcomes” (Anderson, Liam, Garrison, & Archer, 2001, p. 5). Whereas in a traditional classroom environment, teaching presence may be intuitive and communicated strongly through non-verbal cues; teaching presence in the online environment needs to be an intentional process. For example, Glazier (2016) conducted a study of rapport-building strategies in the online classroom to improve student success, including providing video updates, personal emails, and personalized comments on assignments. Students receiving these rapport-building communications from their instructor were observed to have both higher grades and lower attrition rates.

Social presence

Social presence, particularly in the context of computer-mediated communication, is the degree to which the environment can facilitate immediacy. As Rourke, Anderson, Garrison, and Archer (2007) describe, social presence includes verbal and nonverbal communication practices that increase closeness and interaction with instructors and students alike. Social presence “supports cognitive objectives through its ability to instigate, sustain, and support critical thinking in a community of learners” (Rourke et al., 2007, p. 53), facilitating learning that is both socially and emotionally engaged. It has been identified as a key predictor of student satisfaction; in one study, it accounted for 60 % of satisfaction (Gunawardena & Zittle, 1997). Sung and Mayer (2012) identify five facets of social presence that impact student success and satisfaction, namely, “social respect (e.g. receiving timely responses), social sharing (e.g., sharing information or expressing beliefs), open mind (e.g., expressing agreement or receiving positive feedback), social identity (e.g., being called by name), and intimacy (e.g., sharing personal experiences)” (p. 1738). It is important to note that some have argued that social presence does not need to be included as a separate presence in COI and have been critical of its inclusion (Annand, 2011).

Cognitive presence

Finally, cognitive presence is fundamental to a learning environment that cultivates critical thinking skills (Garrison et al., 2001) and while it is held by the learner, it is heavily guided by the interactions in the learning experience. The underlying principle of cognitive presence is engagement in the practical inquiry process, and “the extent to which the participants in any particular configuration of a community of inquiry are able to construct meaning through sustained communication” (Garrison, Anderson, & Archer, 2000, p. 89). Garrison and Cleveland-Innes (2005) conclude that cognitive presence is reliant on the quality of interactions that occur throughout the instructional experience, and suggest instructors provide clear expectations and structuring of activities, conduct assessment aligned with intended goals, and select manageable and appropriate online content. As Garrison et al. (2000) articulate, cognitive presence facilitates students’ working through problems or issues that emerge in learning through exploration and meaning making.

Limits of COI

The COI model by its very nature is reductionist, dissecting the components of a learning community for analysis by instructors and learning designers interested in ensuring a full learning experience. In terms of its comprehensiveness, various authors have explored whether there are other “presences” or gaps. Lam (2015) and Shea and Bidjerano (2010) observed that COI lacks an explicit focus on the learner. Vladimirschi (2012) identified the need to consider cross-cultural implications. Cleveland-Innes and Campbell (2012) suggested a need for developing emotional presence as part of social presence. Kang, Kim, and Park (2007) also explored emotional presence, through the components of perception, expression, and management, arguing it requires its own attention. Anderson (2016) suggested agency be added as a fourth presence. Agency also is relevant to the often-ignored conative domain (Reeves, 2006), which emphasizes the development of a learner’s self-regulation. Beardall et al. (2016) and Blanc (2018) called for the inclusion of embodied presence to emphasize the importance of kinesthetic and affective engagement, especially in the training of dance movement therapists. Finally, recently published best practices for online education depart from spheres of presence but point instead to the importance of relevant and authentic content, a variety of multimedia sources including audio, video, and text, opportunities for individual and collaborative expression in projects, multiple approaches to reflection including writing, podcast, and videos, and explicit connections between learning objectives and content (Kumar, Martin, Budhrani, & Ritzhaupt, 2019).

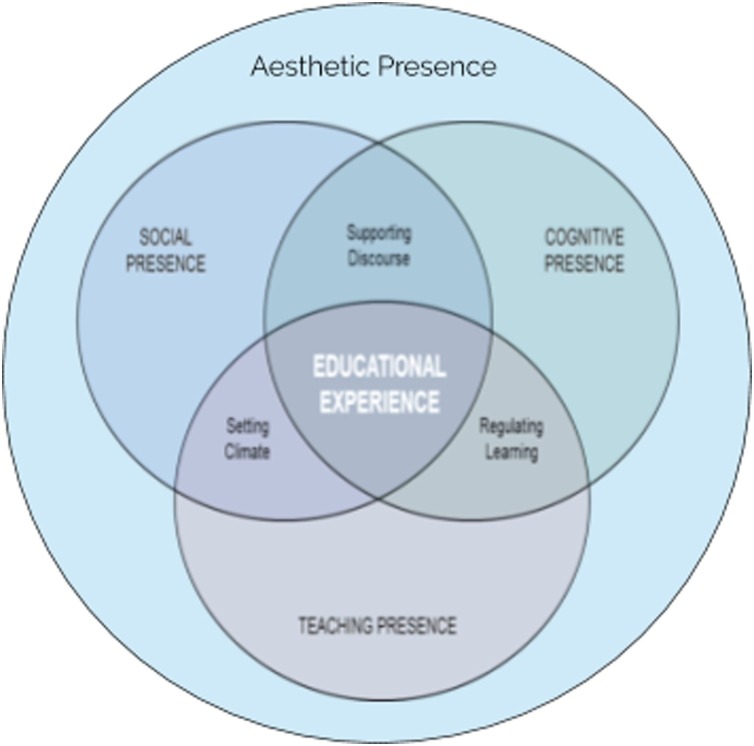

Towards aesthetic presence online

Our proposed concept of aesthetic presence does not suggest a fourth, separate domain within the COI framework. Rather, when deconstructing our online and hybrid graduate learning experience, it became clear that there was something missing in the COI model, both when explicitly teaching CATs and other courses. Our experience indicated that attending to the aesthetic dimension of online learning enhanced all three domains. The skillful use of images, sound/music, poetry, video and audio logs, and performances, for example, offered teachers and students multiple approaches to communicate and express themselves (teaching presence), open up and engage with concepts (cognitive presence), and interact with one another (social presence) (see Fig. 1 ). By paying attention to the use of arts and aesthetics, learning often resulted in rich dialogue, particularly when students were learning about sensitive topics (e.g., course material focused on privilege and oppression in the therapeutic relationship). Indeed, Parrish (2009) describes aesthetic experiences as “heightened, immersive, and particularly meaningful ones” and that they are “important to us because they demonstrate the expressive power of life” (p. 513).

Fig. 1.

Relationship of aesthetic presence to community of inquiry framework.

Garrison

This is not to suggest that text-based feedback cannot build an effective learning community; however, the use of technologies that take advantage of a multi-sensorial learning environment have been shown to increase a sense of community for students online (Kumar et al., 2019). For example, a study conducted on the use of asynchronous audio feedback in online learning found that audio feedback was more effective than text-based feedback for conveying nuance and was associated with students’ feelings of increased involvement and learning community interactions, increased retention of content, and perceptions of care about the student (Ice, Curtis, Phillips, & Wells, 2007). In this study, students were three times more likely to apply content when audio commenting was provided than when text commenting only was provided, suggesting greater engagement with the course’s content. To this end, we propose a definition for aesthetic presence and suggest how it might be applied in online learning environments in order to enhance learning experience.

Definition of aesthetic presence

Aesthetic presence involves a dynamic interplay of symbols, metaphors, and multisensory technologies to facilitate a complex representation of experience wherein imagination, cognition, and affect are optimally engaged. As previous literature has suggested, attention to the use of enactive, iconic, symbolic, embodied, and other sensory strategies may animate conversation, foster openness and connection, encourage flexibility and critical thinking, and facilitate conversations about emergent and emotionally difficult themes. Aesthetic presence can be embodied in the instructor’s approach, embedded in face to face, hybrid, and online course design, included in curricular activities and assignments, and fostered in and between students.

Practical suggestions to integrate aesthetic presence in online course design

In this section, we describe the necessary institutional commitment to acquire and use adequate technology to support online learning with a view to enhance aesthetic presence. We then include examples drawn from our own experiences designing and instructing courses to offer possibilities for cultivating an aesthetic presence in the virtual classroom. These serve as examples of how cognitive, social, and teaching presence can be enhanced by the arts.

Institutional commitment to technology and aesthetically oriented design

We are living in a visual economy where affect, experience, and content are communicated through animation, video, and biometrics. Perhaps it is not surprising then that, while traditional instructional design models and literature are lacking in this area, recent literature in instructional design emphasizes the value of the aesthetic experience. As our capacities to capture and share images and video have become increasingly commonplace, our capabilities in online learning have been transformed (Nakamura, 2009). The relative ease with which one can now incorporate aesthetic presence into online and blended teaching has directly benefited from available technologies that readily allow for audio recordings, video recordings, image sharing, and live interaction time. Today’s learners can easily take photos or video and upload those multimedia objects to share with others through an ever-growing number of social media platforms, and can do so privately within the instructional experience if tools provided by the institution are able to support this. For example, investment in key platforms that integrate with learning management systems to support students and faculty in integrating multimedia and video into the learning experience seamlessly and privately such as Voicethread (multimedia), Kaltura (video streaming), and LiveText (eportfolio) are recommended. Because the tools are integrated into the learning management system and were selected because of their intuitive user interface, little technical expertise is required for either instructors or students to use these tools. Ensuring that technology decision-making is aligned with instructional needs is a component of the decision-making process for acquiring technology tools to support instruction.

At the same time, when learners and instructors have rudimentary communication design and a conceptual and technical skill-set in aesthetics, the online environment is greatly enhanced. For example, learners and instructors need to be attentive to the environment and background in which they are recording video to ensure that it does not distract from their message. Similarly, they need basic orientation in framing an image to ensure they capture critical visual data and in basic audio to ensure that the audio is adequate for the instructional audience. Finally, a commitment to aesthetic presence should inform the design of the user interface in online learning platforms. From our perspective, a beautifully laid out, intuitive interface communicates care for the learning experience that will unfold and enhances an online community learning environment.

Cultivating social presence through emoticons and humor

When moving from a face-to-face to virtual instructional context, one of the biggest challenges is creating opportunities for immediacy and emotional engagement. The emotions embodied in the learning process can range from: positive emotions that motivate learners and enhance creative thinking, to negative emotions (such as situational anxiety) which, if not managed well, can undermine the learning process. Meyer and Jones (2012) articulate the ways in which technology might inhibit affective engagement and, more critically, engagement in the learning process as a whole. They write, “Email, for example, works against the individual's ability to perceive accurately the other's emotional state because the other person cannot be seen or felt, thereby muting empathy and perhaps providing an explanation of the "online disinhibition effect," which occurs when one does not deal face-to-face with the effects of one's rudeness (p.100).

The use of emojis, emoticons, and other forms of affective representation have recently been assessed for their utility in online learning. As Dunlap et al. (2015) wrote,

One way people make up for the lack of nonverbal behaviors and cues in primarily text-based environments is by using paralanguage, specifically emoticons. […]For instance, people use :-) to show that they are happy or smiling. When used in text-based EMC (e.g., email, threaded discussion forums, texting, social networking), emoticons function as textual representations of the nonverbal behaviors and cues prevalent in face-to-face communication, designed to convey clarity of intent and emotion in efficient, direct, and transparent ways. (p. 2)

Emoticons may serve to facilitate a nuanced exchange between students and may be used to instill a sense of humor in the virtual classroom, as well as provide cues to both instructors and students of embodied, affective aspects of learning. Similarly, Orr (2010) has also suggested the use of emoticons and textually based description of body language or emotions when providing distance supervision. Additionally, Meyer and Jones (2012) offered a synthesis of the use of humor in online courses in order to increase: learning, motivation for participation, enjoyment, and social bonding, and the sense of “bringing life” to the community. Recognizing that laughter is less common online than in a face to face setting, Meyer and Jones (2012) called for a better understanding in how people “go online and feel emotion, including laughter and anger” (p.109). Goodboy, Booth-Butterfield, Bolkan, and Griffin (2015) introduced the concept of instructional humor processing theory, which posits that humor connected to course content may be motivating; whereas other types of humor might be distracting and interfere with learning. Rourke, Anderson, Garrison, and Archer (1999) discussed the importance of humor and the expression of emotions in order to help instructors establish a social presence that is ideal for online learning.

From a practical standpoint, this involves investing in user interfaces that permit the use of emoticons and avatars. It also means that online education may necessarily need to make use of personalized learning environments (phones, tablets, ipads, etc.) that permit an exchange of advanced personalized emotion technology such as bitmoji which are personalized avatars (Dabbagh & Kitsantas, 2012; Walton, 2016). Sajnani (2020) used bitmojis to explore Landy’s notion of role, counter-role, and guide in drama therapy. In the online classroom, one of the authors (NS), used this strategy to explore identity which seemed to be motivating in that students found it fun to create and share. Opportunities to cultivate affective immediacy and humor in online learning begins with the tone set by initial communications and assignments through the modeling of the instructor. When facilitating online learning, we have found that modeling the use of emoticons and/or textual descriptions of nonverbal affective cues early on in the semester helps to facilitate broader adoption of interweaving emotional cues in the online space.

The use of icebreakers in online learning is already a best practice (Chlup & Collins, 2010; Goodyear, Salmon, Spector, Steeples, & Tickner, 2001; McGrath, Gregory, Farley, & Roberts, 2014). However, icebreakers also present an excellent opportunity for students to interact using a full range of multisensory technologies. For example, the instructor might assign a “check in” or introduction assignment in which students are invited to upload a written paragraph along with a video or image of a cartoon, photograph, dance, song, comic strip, or poem that represents something about who they are or why they have chosen to take a particular course. Another icebreaker example used by one of the authors (CM) at the beginning of a synchronous virtual class was to ask attendees to make a sound and movement over video to demonstrate how they were feeling about their capstone research project. Members of class portrayed a wide range of movements, sounds, and affect that demonstrated some levels of stress. As they witnessed the others in the class and themselves making these sounds and movements, many burst into spontaneously laughter and verbally reflected feeling both more connected to their classmates and their bodies. This permission for play, embodiment, and affect expression through an icebreaker also allowed students to engage with the research content of that lesson with more presence and engagement. In this example, the instructor also intentionally chose to make a sound and movement from her position teaching the course, which students reflected as important in demystifying the process of research and writing.

Indeed, instructors are encouraged to create their own arts-based introductions in order to model risk taking and to enhance their teaching and social presence online. Having the instructor engage with the same artful assignments asked of students can cultivate a sense of trust. As Lowenthal and Dunlap (2010) suggest, the distance barriers can, “dull or even nullify online instructors' humanness — their emotion, humor, sympathy, and empathy. These human qualities, established through personal sharing, help students develop a sense of trust in and connection with an instructor, which is foundational for cultivating the social presence needed” (p. 70). Their experiments with the use of digital storytelling and self-disclosure from the instructor and embedded throughout assignments in the course facilitated a deeper and more meaningful social presence and served to decrease the sense of isolation often articulated by many online learners.

Further, humor can forge bonds between classmates, deepen one’s curiosity and desire to learn, aid in the retention of information, and help students to tolerate “difficult” or emotionally contentious learning material (Anderson, 2011; Bacay, 2006; Shatz & LoSchiavo, 2006; Stambo, 2006). Intentionally selecting some materials that include humor as part of the teaching method can be particularly effective when teaching online about potentially emotionally-loaded topics. For example, in a course that included content learning about racial microaggressions, one of the authors (CM) blended a traditional scholarly article (Sue et al., 2009) with a BuzzFeedYellow video that addresses similar content through humor and role reversal (Boldly, 2014). The instructor asked students to consider reflecting on the difference in their learning when reading the article versus the humorous video. Their responses indicated that both were important and that the video made it possible for them to remain focused and able to engage with each other about what many agreed was difficult material. Of course, humor and emotional expression are both culturally constructed and embedded, therefore, instructors should approach their use of humor from a critical and cross-cultural perspective in terms of difference, power, and social norms. For further reading on this topic, see Bell (2007); Ellingson (2018), and Lu, Martin, Usova, and Galinsky (2019).

Teaching presence as an improvised performance

Teaching might be best understood through the metaphor of performance, where aspects like role, affect, embodiment, voice, delivery, and play are critical in engaging the imaginations and curiosity of the “audience” of students (Lessinger & Gillis, 1976; Sawyer, 2004; Timpson & Tobin, 1982). In an online setting, there is greater risk of the instructor becoming a faceless, lifeless entity, providing little in the way of performance in order to energize and enrich the learning environment. Further, because of changes to technology, there is a shift in the expectation from learners about the manner in which they will engage with their instructors and peers. Page, Hepburn, Lehtonen, Thorsteinsson, and Arunachalam (2007) noted the shift in user expectation stating, “they do not want to stay in a passive role with different media… they want active participation and emotional engagement, to manipulate the presented objects and expect a degree of emotion and interactivity” (p. 145). Indeed, we have observed an increase in the expectations of learners engaging in online and blended instruction who anticipate interacting with the instructor authentically and through a range of media. Incorporating improvisation makes it possible to avoid a deadened delivery in online settings where pre-recorded lectures, pre-scripted written materials, and rigidly scheduled online discussions and interactions are the norm. This is not to say that structured practices are not useful. Rather, as Sawyer (2003, 2004) observed, disciplined innovation involves an interplay between repeating routines and improvised interaction. Expected activities online provide a strong foundation from which creative improvisation and flexibility might emerge. Similarly, in improvisation forms (dramatic form, jazz, etc), a set structure (or melody in the jazz metaphor) provides the steady beat against which creative and spontaneous moments can be created.

From a practical perspective, aesthetic presence in online teaching includes a range of strategies. Having clear expectations and schedules for learners is important, but should not preclude opportunities for improvisation, which keep the energy and engagement high. For example, in one course design, the instructors (NS & CM) created a schedule where a student was designated as a weekly discussion leader on the assigned readings and was responsible for posting a question for their classmates to answer within a designated time frame. By having the students create the questions, rather than the instructor, this structure maintained a sense of “new-ness.” This approach also privileges a multiplicity of perspectives and voices, encouraging the instructor to respond in an improvised way to the flow of largely text-based discussions. In another example, students were invited to create an artistic response to the weekly readings and to use that as a common reference point for complex ideas conveyed in the assigned readings. The aesthetics of instruction involve a dance between offering framing or additional thoughts, probing questions, additional perspectives, summaries, and space for others to participate (Mazzolini & Maddison, 2007). Depending on the topic of the course, instructors may incorporate additional articles, videos, art-making or news items that are related to the weekly content which also ensure that courses that are repeatedly taught each year are met with a renewed sense of purpose and content.

Live improvisation through synchronous video also heightens engagement. Using programs such as Periscope, Youtube Live, and Facebook Live make it possible for students to interact immediately with course content. Another faculty member at the same university, Angelica Pinna-Perez, held monthly gatherings to enable on-campus and low residency students to form community and interact. These ‘Create on the 8th’ sessions involved live streaming from a maker space in which on campus students were engaged in making art, writing, singing, and reading their own poetry while other students participated from their respective locations (Beardall et al., 2016). We suggest that course design and instructors that experiment with ways in which the arts and multi-sensory technologies might offer new possibilities for engaging learners.

Enhancing cognitive presence through reflexive, collaborative art making and storytelling

The arts can encourage students to participate in praxis wherein personal experience is brought to into conversation with the material presented, applied, and reflected upon. In one class, filming weekly video lectures made it possible to not only frame the topic and the required readings for the week, but also modeled self-reflexivity and the use of personal experience as the beginning of learning. When teaching a module on religion and spirituality in the arts therapies, one of the assigned readings discussed the role of music and religion. As part of the introductory video for that module, the instructor (CM) included a brief story about her grandmother who had been quite ill for several months before her death, where playing hymns at her bedside resulted in an increased orientation to time and space, a brightening of affect, and less discomfort. Sharing this story with students provided a concrete example of some of the intersecting dynamics of aging, music, religion, and pain, worked to enhance the instructor’s social presence online, and encouraged students to make the material they were reading meaningful. Students were invited to share their own stories about religion and music in relation to the assigned readings, with multiple students uploading musical audio clips alongside their video or textual storytelling. In another course pertaining to trauma and recovery in the context of global mental health, the instructor (NS) asked participants, all of whom were health care providers or humanitarian aid specialists, to create a video in which they used images, music, and/or video to communicate how they contributed to a healing environment. Despite their initial hesitation, students almost unanimously proclaim this to be one of the best aspects of the course each year, commenting that the creative process of selecting and editing images, sound, and footage facilitated their reflection on this important topic.

Collaborative art making also facilitates cognitive connections in the online classroom and opportunities should be woven throughout courses. In general, small groups create the opportunity for students to commit to their colleagues and allow learners to problem-solve collectively (Fink, 2013). Group work promotes positive interdependence, social skills, verbal interaction, individual accountability and group processing (Kaufman, Sutow, & Dunn, 1997), all of which can be better supported in online instruction through the incorporation of aesthetic presence. Indeed, part of the work of instructional design and delivery is including opportunities for cognitive capacities to be strengthened alongside social and emotional capacities, which can be enhanced through the use of the arts and aesthetic presence.

From an implementation perspective, for team-based learning to work well, teams should be assigned early in order to anticipate and plan for working together on specific assignments. Similarly for these types of group projects, it is important to orient learners to a variety of tools that might aid their collaboration, including, but not limited to, options for their own synchronous collaboration space online (e.g., through Zoom, Microsoft Teams, Blackboard Collaborate, Adobe Connect, Google Docs). Ideally, team-based cooperative projects are scaffolded so that there are regular check-ins and adequate time in between those check-ins for groups to convene and make forward progress on their collective work (Paulus, 2005) or students can be guided in strategies for collaboration on project co-creation. If the final product is an academic paper or text-based project, including a visual representation of the work as part of the final deliverables can effectively support learners in demonstrating their own use of aesthetic presence.

For example, a hybrid course (designed by NS and taught by NS and CM), included a group project focusing on cultural literacy. Groups of 2–4 participants were formed during the in-person residency and presented their final work later in the semester online. In this assignment, group members chose a film or television show addressing issues relating to identity and were asked to critically analyze their chosen media through the concepts of power, privilege, and oppression. They were then asked to represent their collaboration and their perspectives through a co-created work of art (music, imagery, video with movement, etc.) and to then present this artwork in a 15 min presentation using Voicethread. This technology made it possible to present their artwork, slides, and an oral presentation in a single platform. Other students were able to leave audio feedback which heightened the sense of interactivity in the class. For example, one group (taught by CM) focused their presentation on what is gained and potentially lost in cross-cultural communication used their art as a way to engage and demonstrate this learning. One group member created a piece of visual art and sent it to the next member electronically with no explanation of their piece. The next member witnessed this visual art piece and filmed a dance/movement video based on their own reaction to the original film and the visual art piece they were sent. The third and final member watched this dance/movement video and created their own poem in response to the original film and the film that was created by their teammate. In their Voicethread presentation, this group uploaded all three arts pieces and then discussed the intention behind their individual art-making, how they viewed their teammate’s piece, and moments of disagreement, surprise, or new learning in hearing what they others had taken from their art-making, all serving as a beautiful example of what assumptions arise about another and potential challenges and growth opportunities in cross-cultural communication. This assignment required that students not only engage with one another, but also to do so creatively and collaboratively through arts processing, in order to heighten engagement with the material and foster a community of learning. In course evaluations, students regularly highlight this project as a way to interweave new learning with aesthetic processing, as well as an opportunity to connect with other students.

Conclusion

What differentiates the creative arts therapies from traditional forms of psychotherapy is that this practice unfolds within an aesthetic frame. Aesthetic engagement should, therefore, be reinforced within the process of learning in both in-person and online settings. A stronger integration of the arts in classroom instruction and online may also encourage students to retain their unique aesthetic sensibilities in practice, especially in environments dominated by verbal or textual intervention. The integration of various modes of symbolic communication also increases access to learning for different kinds of learners. While two of the three authors are educators within the creative arts therapies, aesthetic presence should not be seen as limited to courses that explicitly involve the arts. Rather, aesthetic presence should be considered in design, instruction, and delivery for any subject area. In the context of remote education, conscious attention to aesthetic presence in online teaching and learning may help to mitigate disengagement and enhance existing cognitive, social, and teaching presences. Finally, we believe that aesthetic presence is something that each of us will need to cultivate in this new era marked by social distance. It is therefore critical that we continue to innovate ways of creating and sustaining holistic, multi-sensory learning environments and assess their impact in the training of creative arts therapists from the perspective of educators, practitioners, students, and those we serve.

Biographies

Nisha Sajnani, PhD, RDT/BCT is Associate Professor and Director of the Program in Drama Therapy and the Theatre & Health Lab at New York University. She is the editor of Drama Therapy Review. Corresponding author: nls4@nyu.edu

Christine Mayor, PhD Candidate, MA, BCT/RDT is a drama therapist and PhD candidate at Wilfrid Laurier University where she specializes in the racialization of how trauma is defined and treated in school-based settings, and the use of the arts as a way of knowing. She is an adjunct professor at Wilfrid Laurier and in the low-residency program at Lesley University. Christine is the associate editor of Drama Therapy Review.

Heather Tillberg-Webb, PhD is the Associate Vice President of Academic Resources and Technology at Southern New Hampshire University, where she oversees the strategic implementation of technology to support teaching and learning. She teaches graduate courses in education and instructional design for Johns Hopkins University and George Mason University. She formerly served as Associate Provost of Planning and Administration and of Academic Technology and Learning at Lesley University.

References

- Annand D. Social presence within the community of inquiry framework. The International Review of Research in Open and Distributed Learning. 2011;12(5):40–56. [Google Scholar]

- Anderson D.G. Taking the “distance” out of distance education: A humorous approach to online learning. Journal of Online Learning and Teaching. 2011;7(1):74–81. [Google Scholar]

- Anderson T.A. 2016. Fourth presence for the Community of Inquiry model?http://virtualcanuck.ca/2016/01/04/a-fourth-presence-for-the-community-of-inquiry-model/ Retrieved from: [Google Scholar]

- Anderson T., Liam R., Garrison D.R., Archer W. Assessing teaching presence in a computer conferencing context. Journal of the Asynchronous Learning Network. 2001;5(2):1–18. [Google Scholar]

- Bacay S.C. Humour in the classroom–A dose of laughter won’t hurt. Triannual Newsletter by the Centre for Development of Teaching and Learning. 2006;10(1):1–3. [Google Scholar]

- Beardall N., Blanc V., Cardillo N.J., Karman S., Wiles J. Creating the online body: Educating dance/movement therapists using a hybrid low-residency model. American Journal of Dance Therapy. 2016;38(2):407–428. [Google Scholar]

- Beardsley M. Harcourt, Brace; New York: 1958. Aesthetics: Problems in the philosophy of criticism. [Google Scholar]

- Beardsley M. Macmillan; New York: 1975. Aesthetics from classical Greece to the present: A short history. [Google Scholar]

- Beardsley M. Cornell University Press; Ithaca: 1982. The aesthetic point of view. [Google Scholar]

- Bell N.D. Humor comprehension: Lessons learned from cross-cultural communication. Humor. 2007;20(4):367–387. [Google Scholar]

- Berleant A. Temple University Press; Philadelphia: 1991. Art and engagement. [Google Scholar]

- Blanc V. The experience of embodied presence for the hybrid dance/movement therapy student. The Internet and Higher Education. 2018;38:47–54. [Google Scholar]

- Bloom B.S. Vol. 1. McKay; New York: 1956. Taxonomy of educational objectives. (Cognitive domain). [Google Scholar]

- Boal A. Pluto Press; London: 1979. Theater of the oppressed. [Google Scholar]

- Boldly . 2014. If black people said the stuff white people say.https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=A1zLzWtULig Retrieved from: [Google Scholar]

- Bruner J.S. Vol. 59. Harvard University Press; Cambridge, MA: 1966. (Toward a theory of instruction). [Google Scholar]

- Butler J.D. Playing with reflection in drama therapy education. In: Vettraino E., Linds W., editors. Playing in a House of mirrors. SensePublishers; Rotterdam, NL: 2015. pp. 109–122. [Google Scholar]

- Butler J.D. Re-examining Landy’s four-part model of drama therapy education. Drama Therapy Review. 2017;3(2):75–86. [Google Scholar]

- Butler J.D. The complex intersection of education and therapy in the drama therapy classroom. The Arts in Psychotherapy. 2017;53:28–35. [Google Scholar]

- Cahn E. Proposal for studio-based art therapy education. Art Therapy: Journal of the American Art Therapy Association. 2000;17(3):177–182. [Google Scholar]

- Capello P.P. Dance as our source in dance/movement therapy education and practice. American Journal of Dance Therapy. 2007;29(1):37–50. [Google Scholar]

- CAST . 2018. Universal design for learning guidelines version 2.2.http://udlguidelines.cast.org/?utm_medium=web&utm_campaign=none&utm_source=udlcenter&utm_content=site-banner Retrieved from. [Google Scholar]

- Chlup D.T., Collins T.E. Breaking the ice: Using ice-breakers and Re-energizers with adult learners. Adult Learning. 2010;21(3-4):34–39. [Google Scholar]

- Clapp E., Edwards L. Expanding our vision for the arts in education. Harvard Education Review. 2013;83(1):5–14. [Google Scholar]

- Cleveland-Innes M., Campbell P. Emotional presence, learning, and the online learning environment. The International Review of Research in Open and Distributed Learning. 2012;13(4):269–292. [Google Scholar]

- Croce B. On the aesthetics of Dewey. Journal of Aesthetics and Art Criticism. 1948;6:203–207. [Google Scholar]

- Dabbagh N., Kitsantas A. Personal learning environments, social media, and self-regulated learning: A natural formula for connecting formal and informal learning. The Internet and Higher Education. 2012;15(1):3–8. [Google Scholar]

- Deaver S.P. Art-based learning strategies in art therapy graduate education. Art Therapy: Journal of the American Art Therapy Association. 2012;29(4):158–165. [Google Scholar]

- Deaver S.P., McAuliffe G. Reflective visual journaling during art therapy and counselling internships: A qualitative study. Reflective Practice. 2009;10(5):615–632. [Google Scholar]

- Dewey J. Southern Illinois University; Carbondale: 1896. “Imagination and expression”, reprinted in 1972, John Dewey: The early work, 1882–1898, vol. 5; pp. 192–201. [Google Scholar]

- Dewey J. In: Art as experience, reprinted in 1989, John dewey: The later works, 1925–1953. Vol. 10. Boydston J., editor. Southern Illinois University Press; Carbondale: 1934. [Google Scholar]

- Duke L.L. The Getty Center for Education in the Arts and discipline-based art education. Art Education. 1988;41(2):7–12. [Google Scholar]

- Dunlap J., Bose D., Lowenthal P.R., York C.S., Atkinson M., Murtagh J. What sunshine is to flowers: A literature review on the use of emoticons to support online learning. In: Tettegah S.Y., Gartmeier M., editors. Emotions, design, learning and technology. Elsvier; London: 2015. pp. 163–182. [Google Scholar]

- Ellingson L.L. Pedagogy of laughter: Using humor to make teaching and learning more fun and effective. In: Matthews C.R., Edgington U., Channon A., editors. Teaching with sociological imagination in Higher and further education. Springer; Singapore: 2018. pp. 123–134. [Google Scholar]

- Farrington C., Maurer J., McBride M., Nagaoka J., Puller J.S., Shewfelt S. University of Chicago Consortium on School Research; 2019. Arts education and socio-emotional learning outcomes among K-12 students: Developing a theory of action.https://eric.ed.giv/?id=ED598682 [Google Scholar]

- Federman D.J. Kinaesthetic change in the professional development of dance movement therapy trainees. Body, Movement, and Dance in Psychotherapy. 2011;6(3):195–214. [Google Scholar]

- Fink L.D. John Wiley & Sons; San Francisco, CA: 2013. Creating significant learning experiences: An integrated approach to designing college courses. [Google Scholar]

- Fish B.J. Formative evaluation of art-based supervision in art therapy training. Art Therapy: Journal of the American Art Therapy Association. 2008;25(2):70–77. [Google Scholar]

- Freire P. vol. 1. Bloomsbury Publishing; London: 1973. (Education for critical consciousness). [Google Scholar]

- Gaines A.M., Butler J.D., Holmwood C. Between drama education and drama therapy: International approaches to successful navigation. p-e-r-f-o-r-m-a-n-c-e. 2015;2(1–2) http://p-e-r-f-o-r-m-a-n-c-e.org/?p=1223 [Google Scholar]

- Gardner H. Basic Books; New York: 1983. Frames of mind: The theory of multiple intelligences. [Google Scholar]

- Gardner H. Basic Books; 1999. Intelligence reframed: Multiple intelligences for the 21st century. [Google Scholar]

- Garrison D.R., Cleveland-Innes M. Facilitating cognitive presence in online learning: Interaction is not enough. The American Journal of Distance Education. 2005;19(3):133–148. [Google Scholar]

- Garrison D.R., Anderson T., Archer W. Critical inquiry in a text-based environment: Computer conferencing in higher education model. The Internet and Higher Education. 2000;2(2-3):87–105. [Google Scholar]

- Garrison D.R., Anderson T., Archer W. Critical thinking, cognitive presence, and computer conferencing in distance education. The American Journal of Distance Education. 2001;15(1):7–23. [Google Scholar]

- Garrison D.R., Anderson T., Archer W. The first decade of the community of inquiry framework: A retrospective. The Internet and Higher Education. 2010;13(1):5–9. [Google Scholar]

- Gerber N. The therapist artist: Individual and collective worldview. In: Junge M., editor. Essays on Identity by Art Therapists: Personal and Professional Perspectives. Charles C. Thomas; Springfield, IL: 2006. [Google Scholar]

- Glazier R.A. Building rapport to improve retention and success in online classes. Journal of Political Science Education. 2016;12(4):437–456. [Google Scholar]

- Goldblatt P. How John Dewey’s theories underpin art and art education. Education and Culture. 2006;22(1) Article 4. [Google Scholar]

- Goldberg M.R., Phillips A., editors. Arts as education. Harvard Education Press; Cambridge, MA: 1992. [Google Scholar]

- Goodboy A.K., Booth-Butterfield M., Bolkan S., Griffin D.J. The role of instructor humor and students’ educational orientations in student learning, extra effort, participation, and out-of-class communication. Communication Quarterly. 2015;63(1):44–61. [Google Scholar]

- Goodman K.D. Charles C Thomas Publisher; Springfield, IL: 2011. Music therapy education and training: From theory to practice. [Google Scholar]

- Goodyear P., Salmon G., Spector J.M., Steeples C., Tickner S. Competences for online teaching: A special report. Educational Technology Research and Development. 2001;49(1):65–72. [Google Scholar]

- Granger D. Palgrave Macmillan; New York: 2006. John Dewey, Robert Pirsig, and the art of living: Revisioning aesthetic education. [Google Scholar]

- Greene M. Teachers College Press; New York: 2001. Variations on a blue guitar: The Lincoln Center Institute lectures on aesthetic education. [Google Scholar]

- Gunawardena C.N., Zittle F.J. Social presence as a predictor of satisfaction within a computer‐mediated conferencing environment. The American Journal of Distance Education. 1997;11(3):8–26. [Google Scholar]

- Hausman J.J. The rise and fall of the J. Paul Getty Foundation’s programs in arts education. Visual Arts Research. 2007;43(1):4–13. [Google Scholar]

- Hooks B. Routledge; New York, NY: 1994. Teaching to transgress: Educating as the practice of freedom. [Google Scholar]

- Ice P., Curtis R., Phillips P., Wells J. Using asynchronous audio feedback to enhance teaching presence and students’ sense of community. Journal of Asynchronous Learning Networks. 2007;11(2):3–25. [Google Scholar]

- Jackson M.R. Arts and culture indicators in community building: Project update. The Journal of Arts Management Law and Society. 1998;28(3):201–205. [Google Scholar]

- Julliard K., Gujral J.K., Hamil S., Oswald E., Smyk A., Testa N. Art-based evaluation in research education. Art Therapy. 2000;17(2):118–124. [Google Scholar]

- Kang M., Kim S., Park S. Developing an emotional presence scale for measuring students’ involvement during e-learning process. Proceedings of World Conference on Educational Multimedia, Hypermedia and Telecommunications. 2007:2829–2832. [Google Scholar]

- Kaufman D., Sutow E., Dunn K. Three approaches to cooperative learning in higher education. Canadian Journal of Higher Education. 1997;27(2/3):37–66. [Google Scholar]

- Knight A., Matney B. Music therapy pedagogy: Teaching functional percussion skills. Music Therapy Perspectives. 2012;30:83–88. [Google Scholar]

- Knight A., Matney B. Percussion pedagogy: A survey of music therapy faculty. Music Therapy Perspectives. 2014;32(1):109–115. [Google Scholar]

- Kumar S., Martin F., Budhrani K., Ritzhaupt A. Award-winning faculty online teaching practices: Elements of award-winning courses. Online Learning. 2019;23(4):160–180. [Google Scholar]

- LaGasse A.B., Hickle T. Perception of community and learning in a distance and resident graduate course. Music Therapy Perspectives. 2015;35(1):79–87. [Google Scholar]

- Lam J. Collaborative learning using social media tools in a blended learning course. International Conference on Hybrid Learning and Continuing Education; Springer International Publishing; 2015. pp. 187–198. [Google Scholar]

- Landy R. The use of distancing in drama therapy. The Arts in Psychotherapy. 1983;23(5):367–373. [Google Scholar]

- Landy R.J. Training the drama therapist — A four-part model. The Arts in Psychotherapy. 1982;9:91–99. [Google Scholar]

- Landy R.J., Hodermarska M., Mowers D., Perrin D. Performance as art-based research in drama therapy supervision. Journal of Applied Arts and Health. 2012;3(1):49–58. [Google Scholar]

- Landy R.J., McLellan L., McMullian S. The education of the drama therapist: In search of a guide. The Arts in Psychotherapy. 2005;32(4):275–292. [Google Scholar]

- Lessinger L.M., Gillis D. Instructional Services Center, University of South Carolina; 1976. The who, what, how and why of “teaching as performing art”. [Google Scholar]

- Lorde A. Sister Outsider: Essays and Speeches. Ed. Crossing Press; Berkeley, CA: 1984. The Master’s Tools Will Never Dismantle the Master’s House; p. 1984. [Google Scholar]

- Lowenthal P.R., Dunlap J.C. From pixel on a screen to real person in your students’ lives: Establishing social presence using digital storytelling. Internet and Higher Education. 2010;13:70–72. [Google Scholar]

- Lu J.G., Martin A.E., Usova A., Galinsky A.D. Creativity and humor across cultures: Where aha meets haha. In: Luria S.R., Baer J., Kaufman J.C., editors. Creativity and humor. Academic Press; 2019. pp. 183–203. [Google Scholar]

- Maslak M. The aesthetics of Asian art: The study of montien boonma in the undergraduate education classroom. Journal of Aesthetic Education. 2006;40:67–82. [Google Scholar]

- Mazzolini M., Maddison S. When to jump in: The role of the instructor in online discussion forums. Computers & Education. 2007;49(2):193–213. [Google Scholar]

- McGrath N., Gregory S., Farley H., Roberts P.K. Tools of the trade:’ Breaking the ice’ with virtual tools in online learning. Proceedings of the 31st Australasian Society for Computers in Learning in Tertiary Education Conference (ASCILITE 2014); Macquarie University; 2014. pp. 470–474. [Google Scholar]

- McMullian S., Burch D. ‘I am more than my disease’: An embodied approach to understanding clinical populations using Landy’s Taxonomy of Roles in concert with the DSM-V. Drama Therapy Review. 2017;3(2):29–44. [Google Scholar]

- Meyer K.A., Jones S.J. Do students experience. Journal of Asynchronous Learning Networks. 2012;16(4):99–111. [Google Scholar]

- Munro T. W.W. Norton; New York: 1928. The scientific method in aesthetics. [Google Scholar]

- Nakamura K. The significance of Dewey’s aesthetics in art education in the age of globalisation. Educational Theory. 2009;59(4):427–440. [Google Scholar]

- Orr P.P. Distance supervision: Research, findings, and considerations for art therapy. The Arts in Psychotherapy. 2010;37(2):106–111. [Google Scholar]

- Page T., Hepburn M., Lehtonen M., Thorsteinsson G., Arunachalam S. Emotional and aesthetic factors of virtual mobile learning environments. International Journal of Mobile Learning and Organisation. 2007;1(2):140–158. [Google Scholar]

- Parrish P.E. Aesthetic principles for instructional design. Educational Technology Research and Development. 2009;57(4):511–528. [Google Scholar]

- Paulus T.M. Collaborative and cooperative approaches to online group work: The impact of task type. Distance Education. 2005;26(1):111–125. [Google Scholar]

- Payne H. Becoming a client, becoming a practitioner: Student narratives of a dance movement therapy group. British Journal of Guidance & Counseling. 2004;32(4):511–532. [Google Scholar]

- Payne H. Personal development groups in post graduate dance movement psychotherapy training: A study examining their contributions to practice. The Arts in Psychotherapy. 2010;37(3):202–210. [Google Scholar]

- Pilgrim K., Ventura N., Bingen A., Faith E., Fort J., Reyes O. From a distance: Technology and the first low-residency drama therapy education program. Drama Therapy Review. 2020;6(1):27–48. [Google Scholar]

- Reeves T.C. How do you know they are learning? The importance of alignment in higher education. International Journal of Learning Technology. 2006;2(4):294–309. [Google Scholar]

- Rourke L., Anderson T., Garrison D.R., Archer W. Assessing social presence in asynchronous text-based computer conferencing. The Journal of Distance Education / Revue de l'ducation Distance. 1999;14(2):50–71. [Google Scholar]

- Rourke L., Anderson T., Garrison D.R., Archer W. Assessing social presence in asynchronous text-based computer conferencing. International Journal of E-Learning & Distance Education. 2007;14(2):50–71. [Google Scholar]

- Sajnani N., Beardall N., Chapin Stephenson R., Estrella K., Zarate R., Socha, Butler D., J . Navigating the transition to online education in the arts therapies. In: Houghham R., Pitruzella S., Scoble S., editors. Ecarte Conference Proceedings 2017. University of Plymouth Press; UK: 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Sajnani N. Digital interventions in drama therapy offer a virtual playspace but also raise concern. Drama Therapy Review. 2020;6(1):3–6. [Google Scholar]

- Sawyer R.K. Creative teaching: Collaborative discussion as disciplined improvisation. Educational Researcher. 2004;33(2):12–20. [Google Scholar]

- Semetsky I. John Wiley & Sons; 2012. Jung and educational theory. [Google Scholar]

- Shatz M.A., LoSchiavo F.M. Bringing life to online instruction with humor. Radical Pedagogy. 2006;8(2) http://www.radicalpedagogy.org/radicalpedagogy/Bringing_Life_to_Online_Instruction_with_Humor.html Retrieved from: [Google Scholar]

- Shea P., Bidjerano T. Learning presence: Towards a theory of self-efficacy, self-regulation, and the development of a communities of inquiry in online and blended learning environments. Computers & Education. 2010;55(4):1721–1731. [Google Scholar]

- Shusterman R. Why Dewey now? Journal of Aesthetic Education. 1989;23:60–67. [Google Scholar]

- Shusterman R. Cambridge University Press; New York: 2012. Thinking through the body: Essays in somaesthetics. [Google Scholar]

- Simmons H., Hicks J. Opening doors using the creative arts in learning and teaching. Arts and Humanities in Higher Education. 2006;5(1):77–90. [Google Scholar]

- Stambo Z. How laughing leads to learning. APA Monitor on Psychology. 2006;37(6):62. [Google Scholar]

- Sue D.W., Capodilupo C.M., Torino G.C., Bucceri J.M., Holder A.M., Nadal K.L. Racial microaggressions in everyday life: Implications for clinical practice. The American Psychologist. 2009;62(4):271–286. doi: 10.1037/0003-066X.62.4.271. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sung E., Mayer R.E. Five facets of social presence in online distance education. Computers in Human Behavior. 2012;28(5):1738–1747. [Google Scholar]

- Sutherland L. Reader’s Digest; Pleasantville, NY: 2000. Earthquakes and volcanoes. [Google Scholar]

- Thibodeau H., Boroditsky L. Metaphors we think with: The role of metaphor in reasoning. PloS One. 2011 doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0016782. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Timpson W.M., Tobin D.N. Prentice Hall; Englewood Cliffs, NJ: 1982. Teaching as performing: A guide to energizing your public presentation. [Google Scholar]

- UDL on Campus (n.d.). UDL in higher education. UDL on Campus. http://udloncampus.cast.org/home.

- Vega V.P., Keith D. A survey of online courses in music therapy. Music Therapy Perspectives. 2012;30(2):176–182. [Google Scholar]

- Vladimirschi V. An exploratory study of cross-cultural engagement in the Community of inquiry: Instructor perspectives and challenges. In: Akyol Z., Garrison R., editors. Educational communities of inquiry: Theoretical framework, research and practice. IGI Global; Hershey, PA: 2012. pp. 93–115. [Google Scholar]

- Walton C. 2016. Do you even bitmoji? Reify media.http://reifymedia.com/do-you-even-bitmoji/ Retrieved from: [Google Scholar]

- Webster R., Wolfe M. Incorporating the aesthetic dimension into pedagogy. Australian Journal of Teacher Education. 2013;38(10):21–33. [Google Scholar]

- Wix L. The art in art therapy education: Where is it? Art Therapy. 1996;13(3):174–180. [Google Scholar]

- Young J.L. Bringing my body into my body of knowledge as a dance/movement therapy educator. American Journal of Dance Therapy. 2012;34:141–158. [Google Scholar]