Abstract

It is widely understood that the 1962 Kefauver-Harris Amendment to the Food, Drug and Cosmetics Act ushered in the modern regulation of medicines requiring a combination of safety and efficacy. However, fewer appreciate the amendment was applied retroactively to virtually all medicines sold in the USA. For various reasons, many medicines faded into history. Here, we identify and analyze >1600 medicines (including over-the-counter drugs) and their innovators prior to the enactment of Kefauver-Harris. We report 880 of these past medicines are no longer accessible. This project also reveals new insight into the pharmaceutical enterprise, which reveals an industry already mature and beginning to retract before enactment of the legislation. Beyond its historical implications, the recollection of these medicines could offer potential starting points for the future development of much-needed drugs.

Keywords: Kefauver-Harris, FDA, drug discovery

Introduction

The history of modern pharmaceutical regulation began in the days following the thalidomide disaster, when thousands of children worldwide were spontaneously aborted or born with severe birth defects. These afflictions had been caused by a new ‘wonder drug’ entering the global market based on scant evidence of efficacy or toxicity. The resulting public outrage motivated a giant of Congress, Senator Estes Kefauver of Tennessee, to partner with Arkansas Representative Oren Harris to create legislation that required sponsors to demonstrate the safety and efficacy of new medicines (before its adoption a drug could be approved based on safety data alone) [1]. The 1962 Kefauver-Harris Amendment applied these requirements to medicines marketed in the USA (the exception being so-called ‘unapproved’ medicines, the most famous being aspirin) [2]. Many unapproved drugs were discontinued because they were marketed by companies with insufficient experience or incentive to conduct the necessary clinical trials needed to gain what we now appreciate to be a standard marketing approval.

The remaining medicines were subject to the Drug Efficacy Study Implementation (DESI) program, a process facilitated by a contract awarded to the National Academy of Sciences and National Research Council. The DESI system entailed the recruitment of research teams of scientific and medical professionals, who have evaluated classes of drugs to determine their efficacy. Each molecule subjected to DESI was rated as effective, ineffective or requiring further study. Although some medicines lacking DESI approval are still marketed, they are not included in the ‘Orange Book’: the FDA’s list of approved drug products with therapeutic equivalence evaluations. Consequently, these are generally excluded for reimbursement by Medicare Part D and many major commercial payers. As a consequence of the absence of these medicines in the Orange Book, a large number of medicines are not readily identifiable within the pharmaceutical armamentarium. In the years following the enactment of the Kefauver-Harris Amendment, an emerging pharmaceutical industry began to gain momentum [3]. A conventional view is the industry had only been launched in its contemporary form following enactment of the 1938 Federal Food, Drug and Cosmetic Act. The Kefauver-Harris Amendment was a hindrance to the pharmaceutical industry because it decreased the sales of many existing medicines. At the same time, this legislation was a boon because it suddenly increased the number of unmet medical needs.

Another significant change to the industry arose in 1972 with the creation of the over-the-counter (OTC) drug review program. This legislation identified and approved medicines and pharmaceutical ingredients generally regarded as safe (GRAS) or safe and effective (GRASE), granting the ability for manufacturers to market their products without a requirement for a prescription. These decisions were again made and implemented by panels of medical and scientific professionals, who were tasked with conveying recommendations, in particular categories of medicines. The panels convened opportunities for testimony from scientific, industry and patient advocacy groups before designating GRAS or GRASE. After publishing their recommendations for public comment, the FDA could gather additional internal and external information before publishing a final monograph recommending (or not) that a particular new molecular entity (NME) gain status as an OTC medicine, which does not require a prescription.

Fast forwarding to modern times, the pharmaceutical industry is beset with questions of sustainability owing to unrelenting adherence to Eroom’s Law, a descriptor reflecting rising development costs that have been increasing at a logarithmic rate since the 1950s [4,5]. One stop-gap measure to favor a steady stream of new medical products has emphasized repurposing of existing medicines. If one restricts these activities to FDA-approved medicines, the number of new chemical entities (NCEs) available for repurposing is limited to something in the order of 1500 molecules (which includes biologics, where repurposing is arguably less likely) [3]. With this in mind, and to continue an open access project pioneered by the Center for Research Innovation in Biotechnology at Washington University in St Louis, a study was conducted to identify medicines not included in the Orange Book. We report an analysis of early medicines, almost doubling the number of compounds available for repurposing. Moreover, these additions provide a more comprehensive evaluation of long-term trends in the discovery and market forces underpinning the pharmaceutical industry, which could reveal intriguing suggestions about the future of the enterprise.

Collection of information on past pharmaceutical products

The studies conducted here utilized the same procedures we have employed previously to study FDA-approved medicines and vaccines [3,6]. The Center for Research Innovation in Biotechnology at Washington University (https://crib.wustl.edu) compiled a database of medicines used in the USA before the creation of the modern FDA regulations. Our definition of a medicine was restricted to: a medicinal product available to physicians or routinely concocted by pharmacists. We evaluated publicly available information provided by credible sources, primarily targeted at medical or pharmacy professionals. We did not include the equivalent of modern generics or simple combinations of existing or known products. The primary sources included, but were not limited to, editions of the Merck Manual distributed before the implementation of the Kefauver-Harris Amendment (editions 1–10, comprising 1899–1961), The Pharmacopeia of the United States (from 1830 to the 16th revision, published in 1960; the generous work of the Hathi Trust) and New and Nonofficial Remedies published by the American Medical Association, which archived the introduction of new therapeutic options via regular reports from 1909 to 1960. Given the complexity and inconsistent nature of compiling early information, all data were independently verified by searches of public databases, including but not necessarily limited to published literature (e.g., https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/ and https://scholar.google.com/).

The information collected included the generic and trade names (when available) for each product, the date of introduction and the organization marketing the product. To identify missing data, priority was placed upon peer-reviewed scientific journals (identified by PubMed searches). For all products identified, only the earliest example was captured. The initial sponsor of innovative products was assessed using a process based on information provided on publicly accessible documents (especially New and Nonofficial Remedies, which listed marketing organizations and key patent holders). When no corroborating data were available from the sources above, innovators were identified by determining the trademark holders as indicated by searches of the United States Patent and Trademark Office. To assess whether an innovator was still active in drug research, evidence of follow-on product introduction was assessed, as were archival reports of acquisition activity. In cases where there was no evidence of additional product development, a company was considered no longer participating in pharmaceutical research if there were no additional products introduced for >10 years. All data analyzed here are available to the scientific community and general public on the website of the Center for Research Innovation in Biotechnology (https://crib.wustl.edu). Data used specifically within this study can be found at GitHub (https://github.com/WUSTL-CRIB/lost_medicines). We actively encourage all interested parties to explore the data and identify any improvements or additions of potential use for interested investigators.

Analysis of early pharmaceutical products

Earliest pharmaceutical products

We identified 1414 pharmaceutical ingredients (Figure 1) not officially registered as NMEs. These drugs were divided into three categories. The first grouping captured 363 different OTC drugs, where sufficient experience existed to allow the medicines to be sold directly to consumers without the need for a prescription. The second grouping included 347 GRAS substances. Although GRAS components are often not regarded as conveying any efficacy themselves, 171 GRAS molecules had been cited in the medical literature before 1962 as conveying benefit, mostly activity meant to ameliorate symptoms. Consequently, this subset of GRAS compounds was analyzed further (whereas the remaining molecules with no evidence of efficacious activity were not). Of great interest to this project was a set of 880 compounds, which had been documented to convey pharmaceutical benefit but did not regain licensure following enactment of the Kefauver-Harris Amendment. Given the failure to follow-up, these compounds are referred to as ‘forgotten’.

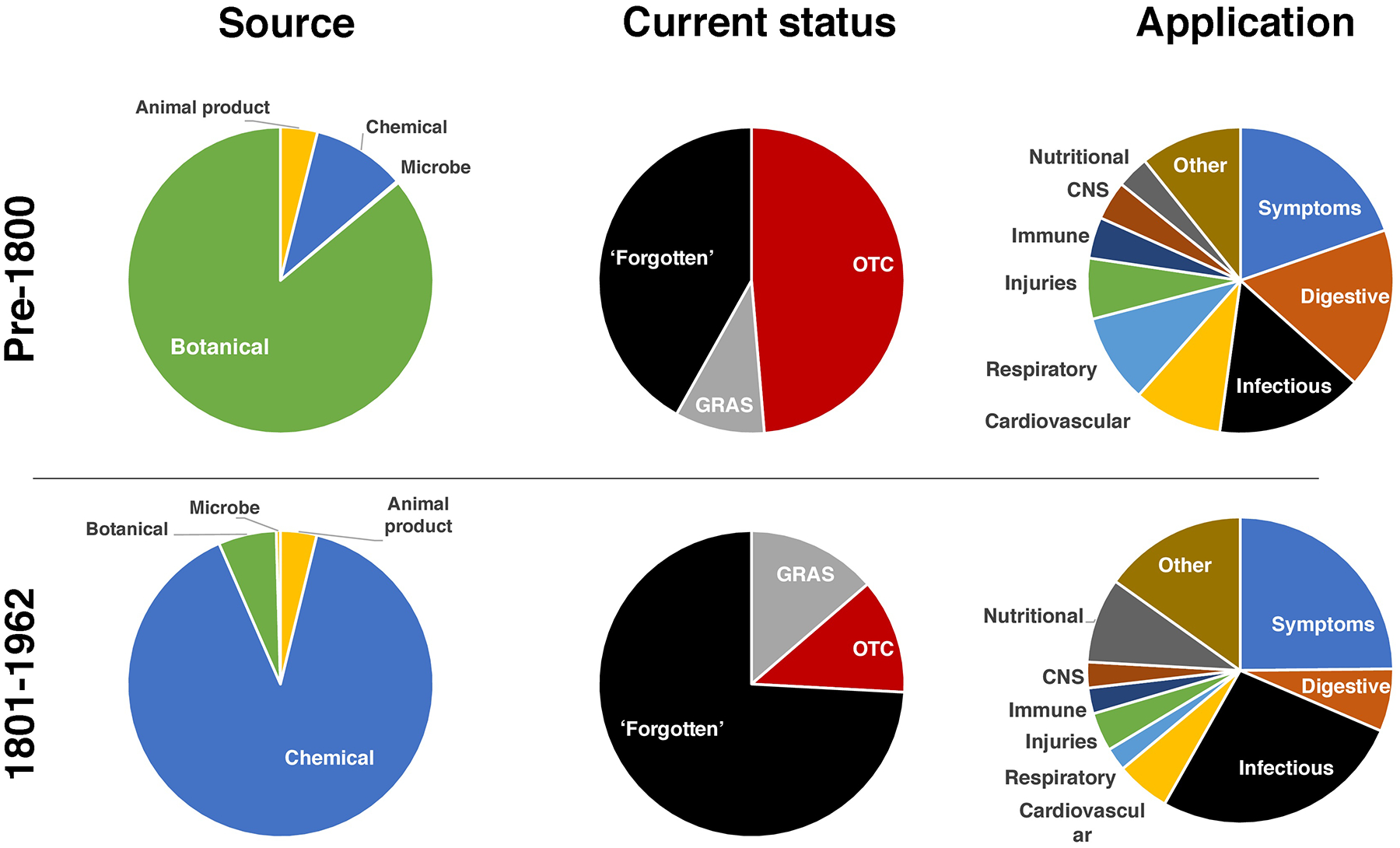

Figure 1.

Compounds and remedies used prior to enactment of Kefauver-Harris legislation. Shown is an overview of the 1401 different medicinal products used in the USA before 1963 according to medical and pharmaceutical sources. The source, current status and therapeutic application of each medicine is indicated. The products have been broadly divided into products first introduced before or after the year 1800. Abbreviations: OTC, over the counter (medicines); GRAS, generally regarded as safe (products).

Given the challenges in establishing the origins of these medicines, many of which are old, the drugs herein were broadly divided into two sets. The first set included 486 traditional medicines in use before 1800. Little if any reliable documentation as to their discovery could be cited. The vast majority of the 486 medicines marketed before 1800 were natural products (Figure 1, left column). Most (86%) were botanical in nature or derived from being ground, emulsified or tinctures thereof. Other major categories included animal-derived products (4%) and rudimentary (not highly purified) chemicals (10%). In general, these herbal medicines were synthesized by apothecaries and it is mostly impossible to ascertain the identity of the individuals or organizations that pioneered each product.

Despite the crude nature of most of these products, more than half (58%) are still in use today (Figure 1, middle column). A search of reputable pharmacy and nutrition store inventories revealed 236 (49%) of these medicines are still readily available as OTC products (available without the requirement for a prescription) and 46 (9%) additional molecules are ‘generally regarded as safe’ (GRAS) according to Federal guidelines. The remaining 42% of the products in use before 1800 had been forgotten and serve as a potential reservoir for future interrogation as to the validity of their therapeutic claims and potential for serving as a starting point for future discovery efforts.

Later pharmaceutical products

More specificity could be gained as to the uses and innovators responsible for the 915 medicines introduced from the ‘pre-modern’ era encompassing 1801–1962. Whereas crude botanicals had dominated traditional early medicines, most (90%) introduced in the pre-modern era were purified chemical products with defined properties. Herbal medicines comprised only one in 16 (6%) of products introduced in this era with the remaining being derived from animal matter or microbes.

Whereas more than half of the earliest medicines are still available today, almost three-quarters (74%) of the drugs introduced in the 19th century are categorized as forgotten. This loss is rather remarkable because most of these medicines are well-defined small molecules as compared with more nebulous and complex natural products. The remaining medicines still available for use today were divided between currently available OTC (12%; including GRASE compounds) products or GRAS (14%) components. To assess the purpose of these early medicines, each product was mapped to a MeSH term as defined by the United States National Library of Medicine (https://meshb.nlm.nih.gov/treeView) (Figure 1, right column). The largest category of applications for which early medicines were developed was to relieve generalizable symptoms; and most prominent among the symptoms were pain and anxiety. Regarding specific medical conditions, digestive maladies and infectious diseases (some of the former probably reflecting the latter) dominated medicines from the period before 1800 and infectious diseases continued to dominate the pharmaceutical landscape of new medicines introduced after 1800. Other prominent indications included medicines meant for injuries, cardiovascular and respiratory diseases, although these were dwarfed by medicines meant to combat microbial intruders.

Rates of pharmaceutical introductions

Whereas the innovative events for the earliest medicines are difficult to attribute to a particular inventor or even a specific time or place, the emergence of patents, trademarks and medico-scientific publishing affords greater precision for tracking the time of introduction for products in the 19th and 20th centuries. It is generally understood that the pharmaceutical enterprise in the first half of the 19th century was dispersed, often localized to particular apothecary shops. As the nascent industry organized and expanded in the 19th century, we witnessed an increase in the number of newly introduced medical products (Figure 2a). In particular, the final two decades of the 19th century saw a sustained rise in the number of approvals, presaging a larger emphasis upon pharmaceutical innovation in the coming years.

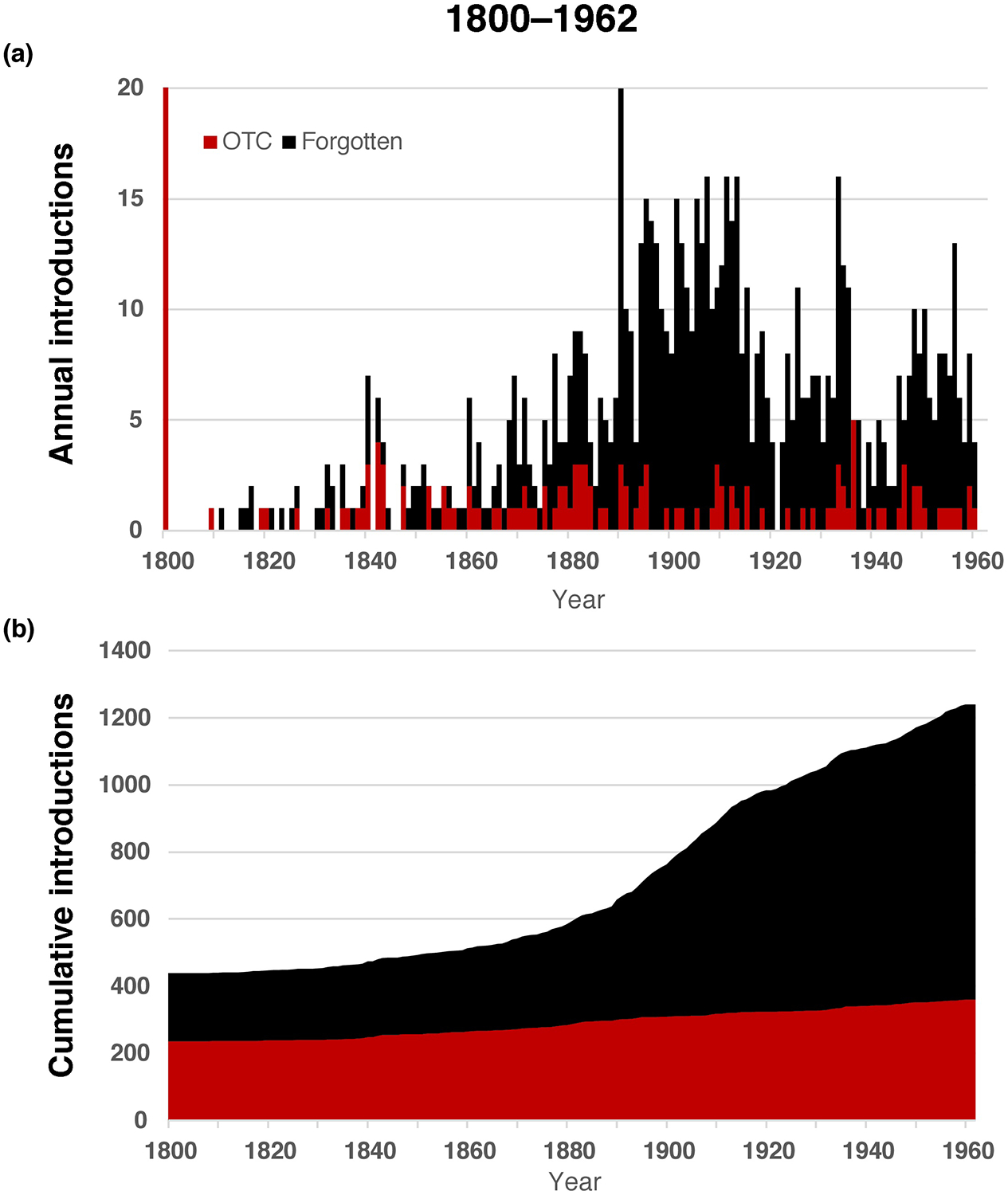

Figure 2.

Pharmaceutical product introductions. (a) The annual rate of new product introduction is indicated for over the counter (OTC; red) and ‘forgotten’ (black) medicines from 1901 to 1962 (the final year before implementation of the Kefauver-Harris provisions). (b) The cumulative number of OTC and forgotten medicines is indicated over time, revealing >1200 pharmaceutical ingredients available to physicians by 1962. Note this graph does not include the 347 GRAS compounds.

The data suggest the pharmaceutical industry continued to increase through the first decade of the 20th century. Corresponding roughly with the beginning of the First World War, the number of new introductions became more sporadic, remaining so until the end of the Second World War. Thereafter, the number of new introductions increased substantially until 1960, when the industry appeared to recede, perhaps in part owing to enactment of the Kefauver-Harris legislation. Given the large number of products lost following implementation of the Kefauver-Harris legislation, it was important to assess the number of available medicines over time. This analysis revealed just over 1600 different medicines were available to physicians and pharmacists in 1962 (Figure 2b). However, more than half of these medicines were lost following implementation of the Kefauver-Harris Amendment (Figure 3a).

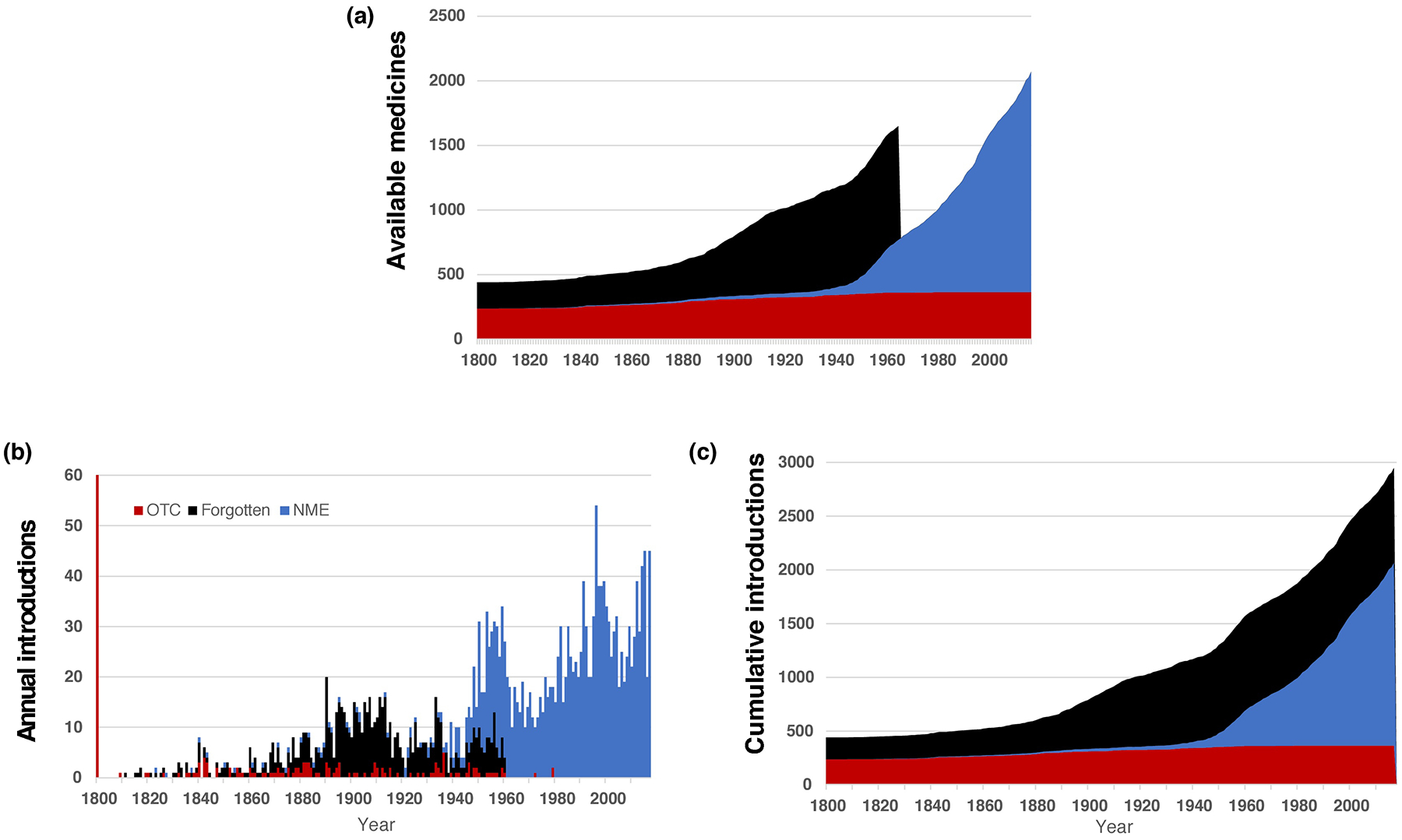

Figure 3.

Growth and maturation of the pharmaceutical enterprise. (a) The cumulative number of available medicines was tracked over time, revealing a dramatic loss in products as a result of enactment of the Kefauver-Harris Amendment. (b) The number of new product introductions is shown on a year-to-year basis, revealing periodic waves of pharmaceutical industry productivity in the decades starting in the late 19th century and continuing to the present day. (c) The cumulative effect of over the counter (OTC), ‘forgotten’ and FDA-approved new molecular entities (NMEs) reveals that almost 3000 different molecules have been used in the USA at one time or another. Note the same color scheme is used as in Figure 2.

The pharmaceutical industry would eventually replace the lost medicines with drugs approved using the today’s standards of demonstrated safety and efficacy. In retrospect, the early years of the Cold War represented a temporary high-water mark (Figure 3b). A level of >30 new products in five of the ten years of the 1950s would not be replicated again until the late 1990s. Even so, maintaining a rate of at least 30 new products per year would prove challenging, even in the early 2000s. The impact of the Kefauver-Harris legislation can also be seen through the number of drugs available to medical professionals. The peak of 1962 would not be seen again until the early years of the 21st century (Figure 3c).

Innovator organizations

Beyond assessing the products, our studies sought to identify and analyze the organizations responsible for introducing medicines before the adoption of the Kefauver-Harris legislation. In its early years, northern Germany dominated the industry, with five of the leading nine companies (Table 1). In particular, the region surrounding Frankfurt, Germany, hosted Merck, Hoechst and Knoll. The American Midwest domiciled four of the 12 largest pharmaceutical innovators, with two additional companies located on the eastern US seaboard (including Merck & Co., a subsidiary cut away from its parent company with the declaration of war in April 1917 and the subsequent confiscation of properties belonging to hostile powers).

Table 1.

Leading innovator organizations

| Organization | Products | Location |

|---|---|---|

| Merck | 52 | Darmstadt, Germany |

| Bayer | 52 | Wuppertal, Germany |

| Abbott | 31 | Chicago, USA |

| Hoechst | 29 | Frankfurt, Germany |

| Parke–Davis | 25 | Detroit, USA |

| Schering | 24 | Berlin, Germany |

| Sterling–Winthrop | 25 | Wheeling, USA |

| Roche | 22 | Basel, Switzerland |

| Knoll | 16 | Ludwigshafen, Germany |

| Eli Lilly | 14 | Indianapolis, USA |

| H.K. Mulford | 14 | Philadelphia, USA |

| Merck & Co. | 12 | New York, USA |

The private sector organizations contributing to the largest number of non-FDA-regulated pharmaceutical products (prior to Kefauver-Harris) is indicated, along with the number of new products and the location of the company.

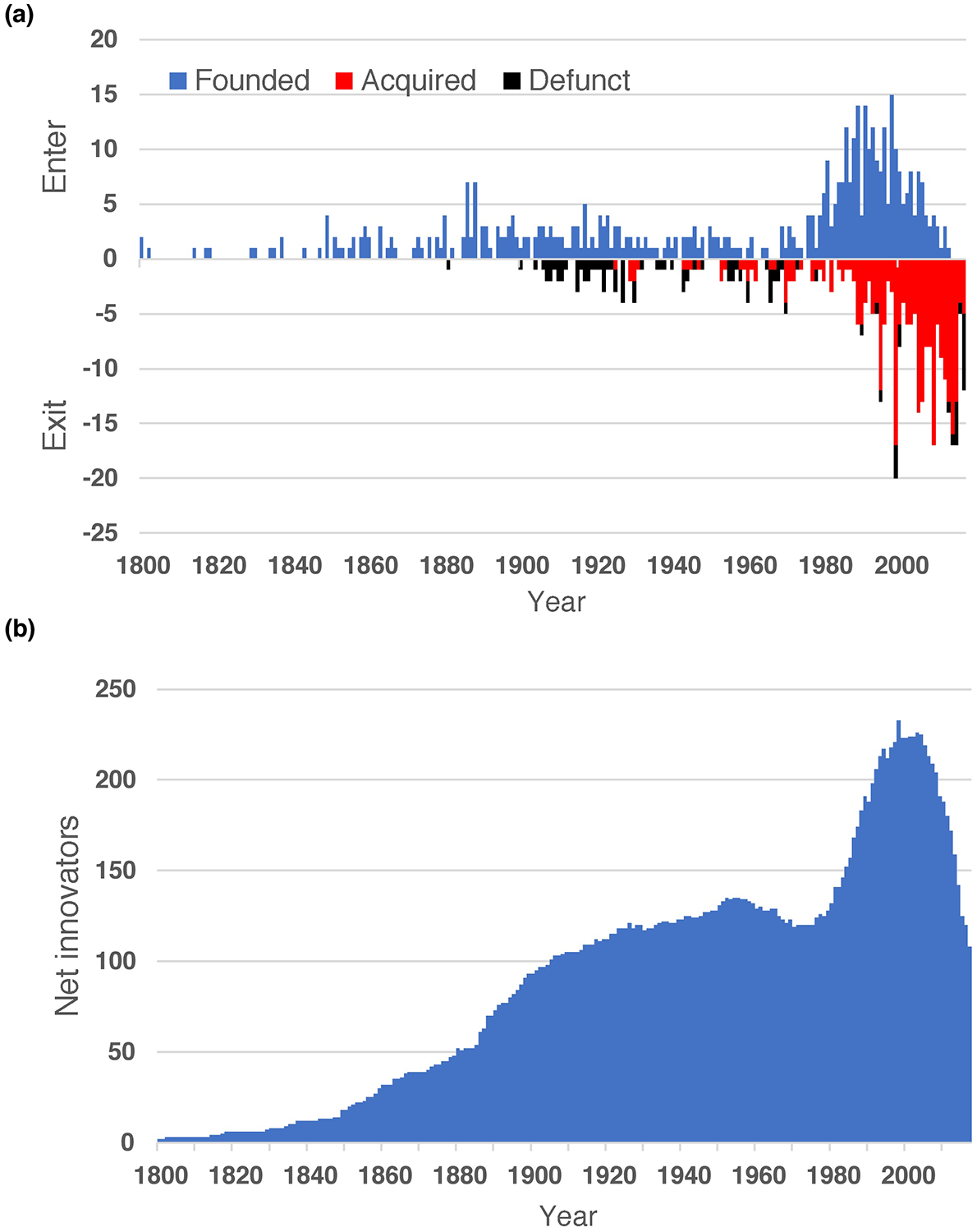

Four hundred and seventy-seven private sector organizations had contributed to the introduction of at least one medicine used in the USA (Figure 4a). When viewed over time, the number of ‘successful’ organizations began to climb steadily beginning in the middle of the 19th century, with a particular burst of corporate foundations in the late 1880s (Figure 4b). The growth rate in the final decade of the 19th century would not again be equaled for 100 years. Interestingly, the growth rate of successful organizations involved in pharmaceutical R&D tapered in the second and third decades of the 20th century. The number of organizations involved in R&D plateaued in the late 1950s and declined somewhat in the following decade. The slowing and halt in growth largely reflected industry consolidation as the rate of mergers exceeded new company creation. The downward creep throughout the 1960s slowed and eventually reversed in the 1970s with the dawn of the biotechnology revolution, the remnants of which are apparent today and have been the focus of past studies.

Figure 4.

Rise and fall of pharmaceutical innovators. (a) Shown is a summary of ‘successful’ private sector innovators, who pioneered at least one active pharmaceutical product. The positive axis reflects the year in which each company was founded (or entered the pharmaceutical enterprise; blue) whereas the negative axis indicates when the company had left research (defunct; black) or was subject to industry consolidation (acquired; red). (b) The net number of pharmaceutical innovators still active in the field of new drug R&D is indicated.

Implications of findings

The major finding of our present study is an analysis of medicines utilized in the USA, but not classified as NMEs. Most of these medicines had been largely or entirely forgotten. In addition, our present analysis includes OTC medicines, which do not require a prescription and adhere to a more stringent safety review than conventional NMEs. The drugs analyzed include relatively old medicines, some with origins in prehistoric times. By including these compounds in a compilation of all medicines used in the USA, one can derive a more complete history of drug development. Many conventional medical histories consider the modern pharmaceutical industry either to have begun in the years following the passage of the 1906 Pure Food and Drug Act (signed into law by Theodore ‘Teddy’ Roosevelt) or the 1938 passage of the Federal Food, Drug and Cosmetic Act (signed by his cousin, Franklin Delano Roosevelt) [7]. However, the present results suggest a sustained and organized pharmaceutical industry had begun much earlier.

Our findings also indicate the pharmaceutical industry had matured considerably by the beginning of the 20th century. Arguably, the earliest pharmaceutical company arose in the late 17th century, with the transformation of the Engel Apothecary into Merck Pharmaceuticals as a family-run business to mass-manufacture herbal extracts to regional pharmacists [8]. The data suggest the modern pharmaceutical industry largely came into maturity in the industrial districts of northwest Germany in and around towns such as Frankfurt and Cologne. By the time of the signing of either the 1906 or 1938 statutes in the USA, the pharmaceutical industry had largely matured into a form recognizable by modern standards. Moreover, this industry was already dominated by many of the same organizations commonly regarded as ‘big pharma’ today, including Merck, Bayer, Roche and Abbott.

The 1950s provided a starting point for Bernard Munos to describe a steadily consistent negative trend in productivity, referred to as Eroom’s Law (a playful inversion of Moore’s Law) [4]. Munos based his theory upon data surrounding the costs for the discovery of new medicines. A lack of data precludes knowing whether Eroom’s Law might have been in play well before the 1950s. A common symptom of a maturing industry is an emphasis upon consolidation. With this in mind, it is conceivable that the increasing turnover of companies during the first half of the 20th century might have been an early sign of Eroom’s Law.

As of the late 1950s (an era considered by many to be the beginning of the ‘golden era’ of pharmaceuticals), the industry seems already to have been showing signs of distress as evidenced by elevated consolidation and a reduction in the number of organizations actively participating in new product discovery. This downturn preceded a later burst in the creation of new and innovative organizations. The so-called ‘biotechnology revolution’ was enabled by new knowledge about disease mechanisms and recombinant DNA technologies. One could question whether the biotechnology revolution was driven by a groundswell of upstart companies as an early response to an industry suffering from declining productivity.

Another novel finding of the present report is evidence of an active retraction in the number of companies performing R&D throughout the 1960s. Increased consolidation during this period could provide yet more evidence the biotechnology revolution was as much a response to a growing vacuum in R&D as a simple response to technological breakthroughs. This idea might be prescient today as the same trends observed in the late 1950s and 1960s (increased consolidation and turnover) have been magnified manifold in recent years [9]. Our updated findings herein reveal the number of previously successful organizations still actively involved in R&D of new medicines is at a level not seen since 1914. In combination with continually rising costs, the industry is now roiled by existential concerns about the sustainability of the drug development enterprise. It is presently unclear where and who will drive the next generation of drug development.

Another interesting implication of the present findings is that the enactment of the Kefauver-Harris Amendment might have helped ignite the biotechnology revolution during the final quarter of the 20th century. As revealed here, this legislation impacted more than half of the medicines available for use in the USA, and the resulting rise in perceived unmet medical needs probably contributed to the creation of new organizations to fill these gaps. This trend is effectively the opposite of the situation today.

Over the past three decades, the biopharmaceutical industry has experienced waves of new shocks that have raised questions about the future of the industry. Regulatory changes, including Kefauver-Harris but also expanding to include medical crises such as the HIV/AIDS pandemic following its recognition in the 1980s, and high-profile toxicity concerns, such as those encountered following the approval of Vioxx or the testing of TGN-1412, have created an uncertain climate for organizations conducting drug development. In parallel, the economics of biopharmaceutical product regulation have also changed with the aforementioned dynamics in the regulatory landscape. In particular, concerns about pricing controls and reimportation have challenged industry business models. These concerns about drug pricing practices have occurred amid altered industry economics and are driving public conversations about drug rationing and the need for even greater generic competition (including, for example, generic biologics). Compounding the problem, these discussions created a general lack of public sympathy at a time when incentivization might be needed to ensure a continued flow of new pharmaceutical products. Thus, the industry has created conditions that severely test the will of lawmakers and regulators to assist or facilitate drug development in general, and repurposing in particular. Although largely self-inflicted, such trends could prove pivotal for an industry with the capacity to alter individual and overall public health, not to mention the considerable economic heft of an industry where market capitalization is measured in trillions of dollars.

Among the challenges facing the biopharmaceutical industry, consolidation since 2003 alone has eliminated half of the innovation companies that had contributed to the research or development of at least one new medicine. Compounding the problem, these acquisitions have generally preceded or indeed triggered staffing reductions in R&D (in part, to recoup the costs expended during the acquisitive event). Owing to the high perceived risks and considerable capital needed for start-up biopharmaceutical companies, the rate of new company formation appears to be shrinking, rather than accelerating to meet the growing need to replace these ‘lost’ companies. Because start-up companies have been major sources of pharmaceutical innovation, greater efforts should be devoted to encouraging or incentivizing the formation of new research-based biopharmaceutical companies. Another growing concern is whether the larger, more established companies have the capacity to efficiently realize the innovative ideas and approaches of start-up companies. The ability of large organizations to rapidly pivot in the face of new technologies has remained a fundamental question and could impact the sustainability of the enterprise. Such concerns, by contrast, might actually favor drug repurposing because the established infrastructures of larger companies, particularly those that have retained experienced discovery expertise in chemistry, might be most capable of applying this expertise to impact positively upon unmet health and market needs by adopting repurposing.

Beyond the historical implications, the work here is part of a larger effort to facilitate the discovery of new medicines. Specifically, some forgotten molecules successfully used before enactment of the Kefauver-Harris legislation could provide a springboard for future drug development. Although this idea might be considered fanciful, such potential cannot be ignored in an era characterized by frustration with the ever-increasing costs of developing new medicines. These rising costs are exacerbated by a loss of formerly successful medicines. A prominent example, capturing headlines today, centers on antibacterials [10]. The era of modern antibiotics, which began in earnest during the Second World War, could have reached its conclusion (for now) and recollections of prior methods to combat infectious disease are being considered to address growing pathogen resistance to antibiotics. In one example, the phage therapies pioneered by Felix d’Herrelle during and immediately after the First World War are increasingly being explored to address antibiotic-resistant bacteria [11].

Concluding remarks

The project presented herein was intended to assist drug repurposing opportunities (either for known or future applications of older medicines). These repurposing activities could focus upon either the known chemical entities that dominated the 19th centuries until today or even use the oldest knowledge of botanicals as a starting point to discover or improve medicinal molecules unknowingly used in earlier eras. Despite the efficiencies that might be gained from repurposing, the private sector response to such opportunities, by established companies and start-ups, has been tepid. This lack interest primarily centers on questions of exclusivity because repurposed drugs are, by definition, known to the scientific and medical communities. Consequently, there is no opportunity for gaining intellectual property for composition of matter. Another approach would be to focus upon new methods or uses of existing compounds, but such claims are often viewed as insufficient to offset the financial risks required for development of even repurposed medicines. Additional incentives might be provided by regulatory agencies to incentivize repurposing, particularly for indications of high priority for the public health. As one example, a prolonged period of exclusivity could be granted for high-priority indications, such as antibiotic-resistant pathogens, as is done for orphan drugs. Such incentives have evoked a considerable response as almost half of new medicines are now approved under the provisions of the Orphan Drug Act. Likewise, the use of priority review vouchers has provided a powerful incentive for organizations developing medicines for certain tropical or childhood diseases and could be considered to promote repurposing for selected medical needs.

It might be overly dismissive to simply disregard a potential wealth of information from these forgotten drugs. Although some of these treatments were undoubtedly inferior, or even harmful, others might have been discontinued for reasons utterly unrelated to safety or efficacy. In particular, many extant pharmaceutical companies of the early 1960s were akin to modern generics companies and lacked the resources or expertise to seek re-licensure following enactment of Kefauver-Harris. Consequently, some medicines with demonstrated capabilities were undoubtedly lost as a stunned industry sought to rebuild itself in the mid-1960s. The Center for Research in Biotechnology at Washington University in St Louis (https://crib.wustl.edu) is dedicated to sharing data about these OTC, forgotten and FDA-approved NMEs. As part of an ongoing commitment, we seek input from interested users to help us gather and edit information and will seek to compile additional biological and chemical data as a service to the biomedical and biopharmaceutical communities.

Highlights:

Medicines marketed before 1963 add 1600 compounds to drugs prescribed in the USA

880 medicines were ‘forgotten’ following enactment of the Kefauver-Harris legislation

These medicines reveal very different dynamics for the pharmaceutical industry

The number of companies involved in drug development today is lower than at any time since 1914

Acknowledgments

Research reported in this publication was supported by the Washington University Institute of Clinical and Translational Sciences grant UL1TR002345, subaward TL1TR002344, from the National Center for Advancing Translational Sciences (NCATS) of the National Institutes of Health (NIH). The content is solely the responsibility of the authors and does not necessarily represent the official view of the NIH.

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

Teaser: This project catalogues over-the-counter drugs and compounds lost following implementation of the 1962 Kefauver-Harris Amendment, thereby offering opportunities for drug repurposing and a different view of the pharmaceutical industry.

References

- 1.Goodrich WW (1963) FDA’s Regulation under the Kefauver-Harris Drug Amendments of 1962. Food Drug Cosmetics Law Journal 18, 561 [Google Scholar]

- 2.Kinch MS, ed. (2016) A Prescription for Change, Chapel Hill, NC: UNC Press [Google Scholar]

- 3.Kinch MS et al. (2014) An overview of FDA-approved new molecular entities: 1827–2013. Drug Discov. Today 19, 1033–1039 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Munos B (2009) Lessons from 60 years of pharmaceutical innovation. Nat. Rev. Drug Discov 8, 959–968 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Scannell JW et al. (2012) Diagnosing the decline in pharmaceutical R&D efficiency. Nat. Rev. Drug Discov 11, 191–200 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Griesenauer RH and Kinch MS (2016) An overview of FDA-approved vaccines & their innovators. Expert Rev. Vaccines 16, 1253–1266 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Wax PM (1995) Elixirs, diluents, and the passage of the 1938 Federal Food, Drug and Cosmetic Act. Ann. Intern. Med 122, 456–461 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Vagelos PR and Galambos L, eds (2004) Medicine, Science and Merck, Cambridge University Press [Google Scholar]

- 9.Kinch MS and Moore R (2016) Innovator organizations in new drug development: assessing the sustainability of the biopharmaceutical industry. Cell Chem. Biol 23, 644–653 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Outterson K et al. (2013) Approval and withdrawal of new antibiotics and other antiinfectives in the US, 1980–2009. The Journal of Law, Medicine & Ethics 41, 688–696 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Nilsson AS (2014) Phage therapy-constraints and possibilities. Upsalla J. Med. Sci 119, 192–198 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]