Abstract

Objectives

Inequalities in oral health have been on the rise globally. In Sweden, these differences exist not between regions, but among subgroups living in vulnerable situations. This study aims at understanding behavioural change after taking part in participatory oral health promotional activity among families living in socially disadvantaged neighbourhoods in Southern Sweden.

Setting

The current study involved citizens from a socially disadvantaged neighbourhood in Malmö, together with actors from the academic, public and private sectors. These neighbourhoods were characterised by high rates of unemployment, crime, low education levels and, most importantly, poor health.

Participants

Families with children aged 7–14 years from the neighbourhood were invited to participate in the health promotional activities by a community representative, known as a health promoter, using snowball sampling. Between 8 and 12 families participated in the multistage focus groups over 6 months. Data were analysed using qualitative content analysis.

Results

Three main themes emerged from the analysis, providing an understanding of the determinants for behavioural change, including meaningful social interactions, family dynamics and health trajectories. The mothers in the study valued the social aspects of their participation; however, they believed that gaining knowledge in combination with social interaction made their presence also meaningful. Further, the participants recognised the role of family dynamics primarily the interactions within the family, family structure and traditional practices as influencing oral health-related behaviour among children. Participants reported having experienced a change in general health owing to changed behaviour. They started to understand the association between general health and oral health that further motivated them to follow healthier behavioural routines.

Conclusions

The results from this study show that oral health promotion through reflection and dialogue with the communities, together with other stakeholders, may have the potential to influence behavioural change and empower participants to be future ambassadors for change.

Keywords: community child health, public health, qualitative research, social medicine

Strengths and limitations of this study.

Involvement of community members in the development of health promotional activities.

Working with both parents and children together to promote oral health.

Triggering knowledge mobilisation through reflection and dialogue.

Partnership between community members and different stakeholders facilitated by health promoters.

Non-participation of fathers may have been a potential source of selection bias.

Introduction

There has been an overall improvement in oral health of the Swedish population in the past decades owing to the advancements in public dental services and state-financed insurance policies.1 2 However, large discrepancies in oral health do exist.1 3–7 The level of inequalities is not substantially different between regions in Sweden but rather between small areas within the major cities, where there is a concentration of subgroups in marginal or vulnerable situations.3 These socially deprived groups frequently include heterogeneous populations who differ by their ethnicity, migration status, historical background, culture and practices related to health, in comparison to the majority population.8 Oral health disparities have been on the rise owing to challenges such as lack of knowledge and poor social policies, unavailability of context-based information and, most importantly, the disconnection between oral and general health.9 This disconnection is a result of the current dental care system globally, as well as in Sweden, considering merely individual behavioural risk factors while addressing oral health problems. However, sociocultural as well as policy-related aspects are key determinants of oral health and general health and well-being. Healthcare providers tend to look at diseases in isolation rather than employing a collaborative approach to address health from a broader perspective. Thus, widening the gap between oral and general health and increasing the burden of disease among socioculturally different and disadvantaged subgroups of the population.10–13

Since the early part of the 20th century, there has been a global drive in reducing health inequalities.14 15 Health inequalities in general are associated with various social determinants including living conditions, employment status, childhood conditions as well as ageing.16 These determinants also apply to oral health disparities. Moreover, oral diseases also share risk factors with other non-communicable diseases and are associated with cardiovascular disorders and diabetes.17–22 According to the WHO, oral health is an integral part of general health and is fundamental to overall well-being and quality of life. Thus, addressing oral health disparities is an inevitable part in health promotional activities aiming to reduce health disparities.23 Oral health impairments have a considerable impact on the quality of life of affected individuals both functionally and aesthetically.24–26

Poor oral hygiene and excessive or frequent intake of sugar between meals are leading causes for caries and poor oral health in general.27 The consumption of fermentable carbohydrates containing added sugars has been on the rise, particularly among children and young adults.28 High consumption of fermentable carbohydrates provokes bacterial action leading to the demineralisation of tooth enamel, which might lead to the development of caries.29 The WHO recommends limiting free sugar intake and replacing it by increasing the consumption of fresh fruits and vegetables, nuts, seeds and wholegrain starch-rich foods, together with practising good oral hygiene as measures to prevent dental caries and periodontal disease, and promote oral health. Tooth brushing with fluoridated toothpaste in combination with a well-balanced diet is the foundation for good oral health.28 30 31

Dental caries is one of the most common preventable diseases in children globally.23 32 33 Cariological risk assessment among younger children is important as caries in early childhood progresses more rapidly since the enamel is thinner in the primary teeth than in the permanent teeth. Caries incidence in preschool age increases the risk of caries in adolescence and later in life.34 Moreover, caries impairs the quality of life of children by disrupting vital everyday functions.2 Children with dental caries tend to have poor self-image and self-esteem.21 23 35 Furthermore, caries may lead to adverse effects including reduced social interaction, pain, discomfort, disturbances in the development of occlusion, stress and depression.32 According to previous studies, dental caries has been shown to be twice as common among non-Swedish children and adolescents belonging to socioeconomically distressed families compared with their Swedish counterparts.1 3–7 Determinants for dental caries in immigrant children include parents’ education level and ability to assimilate to Swedish dietary conditions since they are not often similar to the dietary patterns of immigrant families.3 Parents in a socially vulnerable environment may need community support to establish good dietary and oral hygiene habits, including using fluoride, as part of caries prevention. In vulnerable areas, oral health problems may be part of a number of different social problems and a number of actors in the community, such as maternal care, child healthcare and pharmacies, may need to make joint efforts to provide health interventions for families with different cultural backgrounds.5–7

The Swedish dental care system has a strong tradition of preventive dental care in children and adolescents. Since the 1960s, there has been a steady decrease in caries prevalence among children owing to the effective and timely preventive measures implemented by the Swedish dental care system. Despite these efforts, caries prevalence is considerably higher among selected subgroups of the Swedish population who are more often from socially disadvantaged backgrounds. Studies based on Eurobarometer surveys have identified that socially disadvantaged populations frequently lack knowledge on self-care, including practice of good oral hygiene, diet and use of fluorides.36 This is especially true concerning children in disadvantaged communities who experience more caries than their Swedish peers. Swedish dental care including preventive measures and treatment is provided free until the age of 23. Nevertheless, these efforts have been insufficient in providing dental care without disparities. Children from socially disadvantaged settings are less regularly attending these visits. There has been a lower level of utilisation of dental care despite the increased need among socially disadvantaged migrant groups.1 3 4 Oral health behaviours are mediated to children through their parents with the support of the regional dental care.3 4 Often immigrant parents are unaware of the support services that are available due to recognised practical barriers such as language difficulties and health literacy. Parents also have different expectations from the healthcare system, which are based on their experiences from their own home country.37 38

Most of the information available in the Swedish dental care is evidence based, but lacking contextual adaption. Traditional values and family practices influence the attitude towards health and how communities value oral health as well as what is considered as a standard for good health.3 4 37 An understanding of specific populations, their socioeconomic position, the influence of their traditional practices and, above all, the influence of all of these factors on their health behaviour is necessary to improve utilisation of dental care in socially disadvantaged groups. This will in turn contribute to reduced oral health disparities.3 4 6 9

There is an acute need for appropriate interventions and services to effectively address the oral health disparities of the underserved. These interventions must be culture and context-sensitive novel oral health-promoting solutions and not merely based on the views of the concerned, but rather influenced by the active participation of the populations in need.39 Active participation by representatives from the target groups is crucial for reducing the gap in knowledge as well as tackling and allocating resources that support specific community needs.40

Community-based participatory research (CBPR) is one such a method, which focuses on addressing the determinants of health from a social as well as environmental perspective through active engagement of the community members and other concerned actors throughout the research process.40 Taking into account specific social requirements and increasing community engagement to improve health, CBPR has emerged as an alternative paradigm for health and social research.39 40 CBPR is considered a significant part of translational research, which helps improve the health of specific communities, eliminate inequality and achieve equality in health through community empowerment.41 The principles of CBPR are based on core concepts, including partnership and colearning, capacity building or training community members to become future health ambassadors, knowledge production for societal transformation and prolonged commitment which facilitates achieving higher level goals like reducing disparities.39 CBPR is a systematic effort to integrate active participation by the community in the process of decision-making by creating a mutual understanding of local phenomena and practices specific to the community which contributes to the development of innovative strategies to promote social change.40 Empowerment has been considered critical in the CBPR process although the phenomenon was not frequently explored while evaluating CBPR-based health promotional activities. Empowerment is defined as the ability to control one’s own life especially in relation to own health and well-being.42 Studies addressing oral health disparities focusing on diet and oral hygiene using the CBPR approach involving multiple actors from the community, public sector, private sector as well as non-profit organisations are sparse.

The current study was part of a larger project Health-Promoting Innovation in Collaboration. The aims of the main project were to develop and study health-promoting activities based on participatory research methods. Focus group interviews based on CBPR principles were conducted with residents in a socially disadvantaged neighbourhood in 2016. The interviews aimed at identifying measures to improve health among the residents. During the discussions, the citizens in the neighbourhood identified several problem areas where they needed help, including poor oral health, lack of access to physical activity, poor mental health and lack of knowledge concerning health and healthy behaviours.

Health promotional activities were held as part of the larger project focusing on the challenges identified by the community members. The health promotional activities targeted behavioural change through knowledge mobilisation using a participatory design focusing on key factors such as empowerment.40 Knowledge mobilisation is a process where reciprocal and complementary knowledge is shared between multiple actors, to promote multidirectional co-construction of knowledge. The basis for knowledge mobilisation is interactions that create knowledge and reflections during and after the interactions that facilitate sense-making of the acquired knowledge.40 Community members participated in all stages of the project, including planning, implementation and evaluation. Representatives from the neighbourhood, known as health promoters, were integral in coordinating the activities in the different workshops. In an international context, they are known as culture brokers, and their role has been proven promising in participatory research-driven initiatives.43 44 However, the health promoters working in this project had a unique role since they were educated in participatory research methods. These health promoters were instrumental in identifying and recruiting participants, assisting with language interpretation and, most importantly, to inform the research team about the cultural nuances of the community.

As members of the community, they also had deep knowledge and experience of the common problems faced by these communities particularly in relation to access to healthcare.43

Oral health was one of the challenge areas identified by the community and addressed among the activities initiated as a part of the larger project. This was considered a priority area since dental caries was on the rise in families with young children. The initiatives focused on oral hygiene, the role of fluoride, as well as diet since the residents also perceived a lack of access to personal advice on diet and health in their area.

The aim of the current study was to explore the behavioural change initiated by a participatory community-based health promotion targeting oral health in children and parents living in a socially disadvantaged neighbourhood in Southern Sweden.

Methods

Context

The current study was based in a socially distressed neighbourhood located in Malmö city in Southern Sweden. The majority of the population living in this neighbourhood are non-Swedish speaking. According to a report from the Swedish Intelligence Unit, this neighbourhood has been considered one of the 15 most vulnerable localities in the country.45 The report also highlights challenges like high rates of unemployment, crime, low education levels and poor health among residents which was also supported by prior research concerning high incidence of risky health behaviours among citizens in this neighbourhood.46 47

Participants and actors

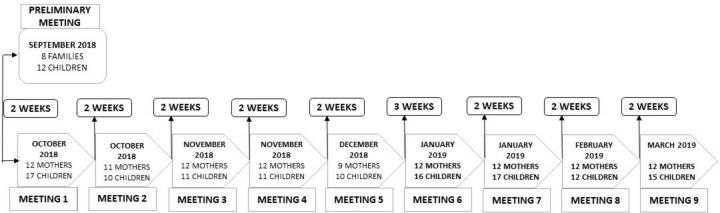

The health promoter involved with the oral health-related activities sent information about the activities 2 weeks ahead of the first meeting and invited families with children between 7 and 14 years to participate in the meetings. Initially, a few families identified by the health promoter volunteered to participate during the first session. More participants were later recruited through purposeful snowball sampling, mainly through spreading information through word of mouth. A total of 12 families were regularly involved in the activities. Although no specific demographic information was collected from the parents concerning the family structure, parental educational status and employment, it emerged from the discussions that quite a few of the mothers in the group were employed. Almost all families had three children, aged between 2 and 12 years. Most of the families were from Middle Eastern countries such as Iraq, Iran, Syria and Lebanon. During the initial meetings, children were present together with their fathers and mothers. Eventually, only the mothers participated regularly together with their children. There were 8–12 mothers during each of these nine sessions and about 15 children during each meeting (see figure 1). Each meeting lasted for about 2 hours with 15 min break after the first hour.

Figure 1.

Chronological timeline of the multistage focus group interviews.

Aside from the participants and academic partners, the research team included representatives from the public and private sectors as well as non-profit organisations affiliated to the project such as the Primary Care (Region Skåne), Pharmacy (Apotek Hjärtat), Save the Children and TePe Oral Hygiene Products. Not all actors were however present in all meetings; their presence was determined by the theme discussed on the different occasions. The presence of a private company among the actors involved in the project may raise questions related to conflict of interest. However, the relationship between the private company TePe Oral Hygiene Products and the research project was mediated by the mutual goal of creating social value for disadvantaged populations. Through their presence in the project, the company TePe Oral Hygiene Products aimed at understanding user needs in order to develop products and solutions for improved oral health in socioeconomically distressed communities. TePe Oral Hygiene Products had no financial gains through their participation in the research project. The head of their odontology and scientific affairs section was the primary representative of the company in the project. Additionally, the representative is also a specialist in paediatric dentistry, which made her presence useful since she could share her valuable knowledge, and experiences with the research team as well as participants. Previous studies have also considered academic–private partnerships in health research as an advantage rather than a limitation, because through such partnership emerge innovative strategies and positive effects which help achieve higher public health goals.48 49

Patient and public involvement

The CBPR approach promotes the involvement of the citizens of the community, and relevant representatives of public and private organisations together with academic researchers in a power-balanced environment while working to identify and implement contextually relevant health promotional activities to promote behavioural change.

Design

The current study is a participative action research study with a qualitative approach where multistage focus group interviews were the mode of data collection. Multistage focus groups are characterised by the same group of persons exploring different themes during several meetings.50 This method was inspired by Paul Freire’s culture circles where the aim is to foster a participatory experience with an emphasis on dialogue and reflective action in response to an emancipatory health education.51 The power relations are balanced within the circle, where one person facilitates the discussions and debates by initiating the process. The facilitator then leaves it to the group to take responsibility for the progress in the inquiry process through self-reflections and sharing individual knowledge and experiences with each other. The dialogues help elevate the participants’ experiences to a higher level of abstraction. The focus groups deduce individual learning, as well as collective ways of thinking through reflection and dialogue within the group. During each meeting, the participants try to identify a common problem in the community, explore the problem further to identify resources and solutions while simultaneously implementing them to bring about transformation.51 52 As a first step in this process, the participants gained knowledge from experts like dieticians, nurses or dentists, in the form of a dialogue exchange. Some examples of the topics selected by the participants include discussions on sugar content in their routine diet and possible healthy alternatives to it (with a dietician). Paediatric nurses provided information regarding psychosocial support for behavioural change. The dental experts in this study were present during all occasions and added knowledge concerning oral hygiene, fluoride and the role of diet in relation to oral health.

Data collection

Preliminary meeting

The families who agreed to participate met at nine different occasions once in 2 weeks over a period of 6 months beginning in September 2018. The first step in the multistage focus groups was to understand the participants’ perceptions on oral health. Prior to the initiation of the actual activity sessions, the research team used a participatory research approach photovoice, to assess the complex phenomenon of diet from a sociocultural perspective among children. In this method, photography was used as a tool to understand the factors surrounding the actual problem in consideration, from within the context of the participants. This is also a form of qualitative research where the photos act, as a focal point to initiate discussion and promote better understanding of participants’ needs. This method helps overcome language and communication barriers and enhances discussions within the group.53 54

The children were requested to bring pictures of healthy and unhealthy food and discussions were initiated based on their photos. In addition, they were also asked to take pictures of their toothbrush, as a base for discussing oral hygiene habits. The children sent the photographs via WhatsApp to the health promoter a few days prior to the scheduled introductory meeting. Photographs sent by the children were compiled, printed and later presented to the children for review together with the rest of the group. One of the team members initiated the discussion with the children using the pictures they sent and led the discussions.

Action points from the preliminary meeting

Through the discussions during the preliminary meeting, it emerged that the children consumed a high amount of sugar as part of their daily diet. The children also expressed a dislike for the lunch served at school. It came to be known that most of the children did not eat breakfast owing to time constraints, family situation and cultural aspects. Through discussions with parents, it was understood that they had limited control over their children’s dietary choices. Regarding oral health and oral hygiene, children frequently visited the dentist when they suffered pain, some had fillings and a few even had teeth extracted in early childhood. Concerning oral hygiene, there was a lack of awareness of fluoride use and its importance for oral health among children. It appeared that despite suffering tooth decay they were not informed about the role of fluorides in caries prevention. The session was followed by a debriefing and discussion with parents to understand their concerns about oral health of their children and the families in general. It emerged that parents were not satisfied with the tooth brushing carried out by their children. The children did not permit parents to help them with brushing despite being advised by the dentist or dental hygienist. In conclusion, parents felt the need for dietary advice focusing on the different meals: breakfast, lunch and dinner. In addition, they also wanted to gain more knowledge on oral hygiene habits. They preferred all sessions to be in the presence of the children since they would follow the advice of others better than they would do if the parents told them the same thing.

In the consecutive occasions, dialogue-based teachings or reflective dialogues were facilitated by experts in the related fields to address different challenges that emerged in the first meeting. Behavioural change in children through educating parents was also driven by the reflective dialogues. Previous studies55 state that reflective dialogue-parental education is an effective method to enhance parental awareness and improve parenting skills. This is achieved through confidence building, which is promoted, by social support and peer influence. The discussions in the group were predominantly held in Swedish and interpreted in Arabic by the health promoter for the benefit of some parents who could not speak Swedish. At the beginning of every meeting, families had the opportunity to provide feedback from the previous session. They also discussed their ability to make changes inspired by what was learnt from their participation and the challenges faced in doing so. All discussions were audiotaped with the consent of the families. A member of the researcher team also acted as an observer and was responsible for taking notes during each meeting.

Data analysis

One team member (RR) reviewed audio recordings repeatedly to develop a content log of the discussions as well as summary. Listening to the recordings several times facilitated rapid identification of codes together with the help of the observational notes. Two other members from the research team who were not involved in the data assimilation process listened to the recordings to complement the preliminary analysis performed by the first researcher (EC, MR). Following this, the researchers discussed and reflected on their findings together and came to consensus over a final list of codes which were finally confirmed by SBR. The discussed codes were placed under categories and each category was further defined in detail to identify overarching themes. While data extraction was done using rapid identification of themes from audio recordings (RITA) method, qualitative content analysis with an inductive approach56 was used to identify themes relevant to the research goals. The RITA method has previously been established as a method that yields prompt and detailed results from qualitative data while also being less time consuming and less labour intensive.57–59

Qualitative rigour

Results from qualitative studies are evaluated based on certain criteria such as following Guba and Lincoln’s criteria60 as factors that predict the authenticity of the results. According to these criteria, the quality of results depends on the methods of data collection and the technique of data interpretation. The current study is built on the CBPR principles of colearning and sharing, thereby holding the contact between the researcher and community members closer; thus enabling better understanding and interpretation of information provided. Furthermore, the involvement of the health promoter at the different stages of the research process ensured open communication. This provided an opportunity for the participants to share trustworthy accounts of experiences to other members in the group ensuring credibility. The research team made observational notes describing the context to support the audiotaped data, which contributed to transferability of the findings. Dependability was attained by involving a third researcher who was not involved in the initial data collection and analysis to review the coded data. To achieve confirmability, the third member from the research team rechecked audio recordings and the observational notes in iterations. Findings were shared with participants and reconfirmed when necessary.

Issues related to reflexivity were addressed using constant communication with the participants after each meeting, through peer debriefing, as well as triangulation by including several members in the research team in the focus groups as well as analysis of audio recordings. Self-reflexivity or personal reflexivity of the members of research team was considered rather positive since it gave the possibility for the team to reflect on power and privilege issues in relation to the context. This is also in line with guidelines indicated by prior work in participatory research.61

Ethical considerations

The Regional Ethical Review Board in Lund approved the study (DNR 2016/824). All participation was voluntary, and the participants were informed that they could leave the discussions at any time without any explanation or consequences. The parents received detailed information regarding the purpose and nature of the study, and were requested to provide written informed consent before enrolment. Parents were requested to consent their own as well as their children’s participation. All invited participants consented both their own participation as well as that of their children. The children also gave a verbal consent. Participants were ensured confidentiality at the time of data collection. In addition, participants were also informed that all results were to be presented abstracted and at a group level and no individual shall be identifiable through their expressions in neither reports nor scientific articles that emerge from this study. This information was explained verbally as well as included in the information letter that they received when they signed the informed consent. Considering the nature and design of the multistage focus group, it may be difficult to ascertain confidentiality; however, the research team explained to the mothers concerning this and requested them to refrain from discussing sensitive or personal opinions shared in the group elsewhere.

Findings

Three main themes including meaningful social interactions, family dynamics and health trajectories were identified on exploring reflective thoughts and discussions in the focus groups with an aim to understand the process of changed behaviour within the group.

Meaningful social interactions

The mothers reported in the beginning that they agreed to participate in this study since they trusted the health promoter. However, after a few meetings they began to enjoy the social aspects of being with new people especially since they would otherwise sit idly at home.

In the beginning I came here because we knew the ‘health promoter’. After coming here a few times, we started to interact with the others in the group. Now we do activities outside of this group, for example we go out on picnics or barbeque together. Coming here and meeting people is definitely better than sitting idle. (Mother, Meeting 8)

Although the mothers enjoyed the social aspects during the initial meetings, they began to look forward to interactions that were more purposeful and considered gaining knowledge as primary focus.

It is not just for meeting others. It is good that I get information about healthy food and what a good breakfast is for both my children and me. I just do not go there every time to meet someone else. We can do that in a different way. (Mother, Meeting 8)

The mothers in the group believed that the discussions and information they received were better than what they had received from the nurses at the primary care. They highlighted the importance of being in a group in the learning process since the discussions were interactive and not controlled or determined by the facilitators or field experts.

When we meet a nurse at a primary care center, they sound tired and disinterested and hence do not provide the same information we get here. It was not of good quality neither educational nor motivating as we do here within the group. (Mother, Meeting 6)

The mothers felt that they were given the opportunity to gain new knowledge and learn, and the possibility to discuss and share their own knowledge and experiences. They also gave and received tips from each other within the group.

It was not just a lecture, we got to ask, discuss and learn from the experts and from each other. It was fun to give tips and suggestions to each other based on our experiences. (Mother, Meeting 7)

Some of the mothers were unsure from the beginning if they could make changes to their diet. After participation for a few weeks, they felt motivated and gradually started to make changes.

In the beginning I was drinking 5–6 liters of juice a day, after being here I have reduced it to 1 liter per week. I initially thought that I can't but when I was told about the sugar content of the juice and learnt about others changing their dietary patterns, I too decided to change. (Mother, Meeting 7)

Towards the end of the sessions, several mothers expressed their interest in communicating the knowledge they gained to the rest of the community, as they believed that the information was important. They even went a step further and mentioned that they would like to join the research team in the future to support the mission to improve oral health among the population in the neighbourhood.

I want to be one among your team, you are few and there are many people who need help so I want to help others as you do. (Mother, Meeting 8)

Children in the group were also interested in spreading their knowledge to their friends and classmates. One of the children in the group had already begun speaking about sugar intake and oral health to his class.

I told my classmates about why eating sugary things is harmful and how sugar affects the teeth. My teacher was impressed with me and wanted me to share more information in the class after each meeting. (Child, Meeting 6)

Family dynamics

The role of individual members in the family, bonding and interactions between family members together with sociocultural or traditional values carried within the family influence lifestyle and behaviour of the children. Acculturation and migration also have an influence on the relationship between children and parents, specifically mothers. Thus, a sustainable change in diet of children is influenced by family dynamics.

Mothers in this study perceived that they had important responsibilities but were merely limited to executing actions with little influence on decision-making. This was considered as a direct challenge in promoting dietary changes in the family.

I am a woman I can decide only for myself, I cannot tell my husband what he has to eat. My children eat what their father eats. I drink a lot of tea and my children drink tea too. It is our tradition. (Mother, Meeting 2)

Children in the families acknowledged their traditional practices and consumed high amount of sugar as part of it. They believed that following the parent’s action was also associated with culture.

We drink tea as a family in the evenings and during weekend. I cannot drink tea without sugar in it. I usually put four teaspoons of sugar in my tea. That is how my parents drink too. It is a cultural thing. (Child, Meeting 1)

From the discussions with the children, it emerged that they were often alone when they ate breakfast so they ate whatever they found in their refrigerators.

I eat breakfast alone and I eat whatever is available in the refrigerator. I mostly eat bread with Nutella, as it is easy to make. My mother goes to work and my father is still sleeping then. My brother never helps me even if I ask. (Child, Meeting 3)

Some mothers believed they could not provide enough attention to their children’s diet due to lack of time and a stressful life in Sweden. Mothers also believed that fathers could not help children, as well as the mothers, as men have low involvement in the upbringing of children. After participation in the activities, the mothers found a solution to this through the tips they got from fellow participants.

I leave early to work and my children eat breakfast by themselves. My husband cannot prepare food and take care of the children, sometimes he forgets everything, he miss to put on their wooly caps in winter. It is cultural. (Mother, Meeting 2)

Mothers valued the involvement of children in the activities since they recognised changes in children’s behaviour at home after participation. Children were more cautious about their diet and sought their parents’ help while brushing their teeth, which they refused to do previously.

The good thing is that we got to be here with our children, and that they also got to listen and learn. They have become more responsible at home; my son does not want to eat as many bananas as he did earlier because he has learned that it has more sugar. He wants me to help him brush his teeth; he would never allow me to do it before even if I insisted. (Mother, Meeting 5)

Mothers were initially unsure about influencing the diet and lifestyle of their spouses, but when they made changes for themselves their husbands chose to do so too. In some households, women brought home information material from the meetings to convince their husbands.

At first I thought it might be hard for me to influence my husband, but when I changed my own diet he chose to change his too. (Mother, Meeting 8)

When I told him about sugar content in each food and showed the sugar brochure my husband was shocked and immediately decided to change. (Mother, Meeting 8)

Health trajectories

When the mothers initially volunteered to participate in the activity and attended the meetings, they were concerned about their children’s oral health behaviour and diet. From the initial discussions with parents and children it emerged that children frequently consumed sugar in form of candies, juices and tea with sugar, which was a part of their tradition. Parents were also worried since children frequently complained of toothache and some of them had several fillings or a lost tooth.

Some parents even believed that they needed some amount of added sugar for normal body function. Parents were unable to monitor and control their children’s sugar intake.

I must have juice in the refrigerator all the time because my children want to drink juice once every hour. I cannot say no to them because they will not eat anything else. I can't help but buy juice as I also like it. (Mother, Meeting 1)

After participation in the activities, mothers reported a sense of satisfaction and relief since they were able to take control over their situation and bring about change, promoting a healthier lifestyle for their children. This in turn made them happier and they slept better.

I felt bad when I realized that it was me who bought juice and sweets. I understood that if I stop buying things it would help my family. Since I did that, I sleep better because I know I have provided healthy food to my children. (Mother, Meeting 8)

Children in the group were particularly excited about learning to brush their teeth from experts and the use of different kind of toothbrushes. They also spoke about the relationship between healthy teeth and healthy living after participation in the discussions.

It was fun to see all the different brushes. I never knew there existed so many. I learnt to brush my teeth. I think that we must brush our teeth well since it makes us feel healthy. (Child, Meeting 7)

Mothers began to understand the influence of diet on their health more distinctly after participation in the activities. Mothers reported a change in self-perceived health owing to behavioural change after participation in the activities.

Since I made changes to my diet, I started feeling fresher and healthier. I was at the doctor last week and he was surprised because I have lost weight. (Mother, Meeting 8)

Participants began to understand the connection between oral health and general health and well-being after having participated in the activities.

Through participation in this activity I have learned about the connection between oral health with general health. I have actually seen a change in my physical health. (Mother, Meeting 8)

Discussion

Participation in the health promotional activities led to changed oral health-related behaviour, and appeared to empower mothers and children, to gain control over their health, which in turn extended into the entire family as illustrated in the main findings of social interactions, family dynamics and health trajectories. The analysis also draws on Zimmerman’s definition of psychological empowerment, which includes the dimensions of people’s perceived control of their lives related to their level of participation in community change.62

The current study shows that a participatory dialogue and reflection, targeting behavioural change considering the actual needs of the community, may initiate lifestyle changes among socially disadvantaged immigrant families compared with mere personal dietary counselling in primary care centres or at the dental clinics. This is in line with a previous study63 which shows that dietary counselling offered by healthcare workers is frequently inconsistent, unclear—and beyond all—not culturally tailored and hence not effective in promoting dietary changes. On the other hand, in participatory research, participants are engaged in a collaborative process of social transformation, which enhances the possible uptake of knowledge through reflection within a social circle.64 The role of mothers as important channels for behavioural change in the families is in line with a previous study based on oral health educational interventions involving immigrant families with children living in Australia.65 However, the intervention offered in the Australian study was a predetermined intervention, unlike in the case of this study where the participants determined the health promotional activities. In addition, the health promotional activities in the current study were implemented over a longer period with frequent visits and involved children aged 7–14 years in contrary to the Australian study where the intervention was provided for 3–4 weeks and children of younger age (1–3 years) were included. Involving older children in the discussions offered an additional benefit, as they were also active during the sessions, had the opportunity to ask questions and learn from experts, and thereby made changes in their lifestyle.

The interaction between individuals in a group appeared to exert a strong influence on the behaviours, which was beyond the mere social aspect of meeting people to break isolation. The process involved utilisation of collective knowledge to bring about changes in daily life through mutual sharing and motivating each other. These results are in line with discussions in a review study66 that shows that participation in interactive lifestyle interventions in small groups better promotes behavioural and lifestyle changes. This is because individuals in a group are often in similar situations and through being role models to each other even the harder to convince participants in the group tend to change.66 Similarly, according to an earlier study, social interaction between children is known to help in shaping their cognition, altering their attitudes and beliefs, as well as understanding of reality that in turn promotes behavioural changes.67

The findings from the current study are in line with a previous study which describes the process of change in parental conception following reflective dialogues which facilitated behavioural changes in four stages, including awareness of one’s current conception, dissatisfaction with one’s current conceptions, support and understanding from others, exposure to alternate ways, opportunities for encouragement and reflection.55 Freirean principles state that the consequence of offering knowledge via dialogue as a tool enhances the individuals’ control over self and their beliefs thereby leading to self-empowerment,68 and such an empowerment may result in behavioural change.69 These principles were exemplified in the current study where the mothers in the group became conscious and aware of what constituted the meals they served their families through reflecting on the images of their own breakfast during the initial meeting. Further, through participation in the group meetings they realised that they had a significant role in promoting a healthier diet to the rest of their family. Despite being frustrated in the beginning, they eventually found support from other participants in the group who were in similar situations. The support, understanding, mutual respect and caring shared among each other in the group tended to have made the mothers psychologically stronger to accept the fact that their families did not consume healthy diets. They began welcoming alternative conceptions that they were exposed to both from the different actors providing knowledge as well as through interaction with other members in the group with varying perceptions. Over time, the participants progressed from a stage of seeking knowledge to sharing knowledge through providing tips to one another as well as to their friends and relatives in the community. The mothers expressed a feeling of confidence in self and appeared to be empowered after participation, which they were lacking in the beginning of the study when they really felt powerless due to their inability to take control over their children’s oral health-related lifestyle.

Practical implications

It became known through this study that brochures and health education material used in the Swedish healthcare were adapted to the Swedish context and were considered less useful for needy communities. The participants believed that educational material showing sugar content in various food products would help understand sugar intake among families in socially disadvantaged neighbourhoods. As a part of the activities, participants learnt to read and understand the ingredients list printed on the package of different food products. They also learnt to convert the quantity of sugar in grams to sugar cubes, which helped them communicate and spread the knowledge they gained. Participants gathered photographs of food products and some culturally specific dishes which they wanted to include in a new brochure. Together with the actors in the research team and a dietician, the participants developed a sugar brochure. The sugar brochures were printed in multiple copies by TePe and distributed to the participants. The brochure was also shared with the primary care, dental care and pharmacy for further dispersal of the material. The participants, both mothers and children, found the brochure as a concrete tool for informing their family and friends in the community about the harmful effects of sugar consumption. The mothers in the group became oral health ambassadors in the community and started an initiative ‘Fight against sugar intake’. They organised small gatherings with other women in the community to talk about the knowledge they gained from their participation in this study, together with the help of the brochure. Some of the children in the group who expressed interest to learn more about oral health, diet and healthy lifestyle were specially educated by experts from TePe over a period of 1 month with one lecture a week. After participation in the educational sessions, the children were certified as child oral health ambassadors. These child oral health ambassadors began spreading their knowledge in their respective schools.

Limitations

The current study could have been complemented with a quantitative assessment to explore changes in oral health-related behaviours after participation in the activities. Such an evaluation is planned with this group using a participatory approach where health promoters will have an active role in distributing health surveys and analysing them together with researchers.

Another potential limitation in this study is the non-participation of fathers, which may have introduced a selection bias. This, however, does not undermine the value of the findings from this study. Fathers in this study decided not to participate in the activities since mothers had the primary role of raising children and steering their behaviour in these communities. This is also in line with prior research on family traditions and the significant role of mothers in raising children.70 71 A notable feature in multistage focus groups used in the current study is that participant dynamics may change during subsequent meetings in that new families take part or some of the original families do not take part in some of the meeting series. According to previous studies, the introduction of new members has a positive effect in that new discussions emerge and more knowledge is generated.51 However, in the current study it must be noted that 8–12 families attended almost all meetings while there were also a few new families in every occasion, which steered new discussions and new perspectives that benefited even those families who came regularly.

The RITA may be considered a methodological limitation. However, in contrast to the original method of listening to the audio for 3 min,57 the themes were identified after listening to the entire audio recording several times. In addition, extensive field notes were collected during each of the nine sessions, which were used as complementary information to the audio recordings during analysis. Aside from this, the research team also had a deeper understanding of the participants’ views from a contextual perspective owing to their prior engagement with participants in the trust-building phase, which was also enhanced by the involvement of health promoter.

Conclusion

The current study highlights the importance of working with the family, to ensure sustainable lifestyle changes. Placing the focus on both the process of change as well as the action paved ways to explore how families experienced their participation in the activities offered as well the determinants of behavioural change. Providing mothers and children with the knowledge and skills to promote oral health behaviours influences their immediate family and their communities or social groups. However, the success of knowledge transfer is mediated by the principles of participatory research that strengthens and appeared to empower individuals, and may contribute to a healthier society and reduced health disparities.

Reflective dialogue and interactions within the social context influence the health promotion process, and through the participatory approach, individuals seem to gain empowerment that in turn can lead to behavioural change. Such a strategy can be considered in future work targeting to promote health in disadvantaged populations.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

The authors thank the health promoter, Hoda Abbas, for her commendable contribution and support in the different phases of the study. The authors thank the participants from the community for giving their time to this work. The authors also thank the municipality for providing their premises to conduct the various activities.

Footnotes

Collaborators: There were no external collaborators who were involved in the work described in this manuscript.

Contributors: RR, EC, SBR, ANO, AK and MR conceptualised and designed the study. RR, SBR, ANO and MR collected data. RR, EC, MR and SBR analysed the audio recordings. RR wrote the initial version of the manuscript under the guidance of AK, EC and MR. All authors gave detailed feedback on early iterations of the manuscript, and have read and approved the final version of the manuscript.

Funding: This current work was part of a larger project funded by VINNOVA (DNR 2016-00421, 2017-01272).

Competing interests: The presence of a private company TePe Oral Hygiene Products here, represented by the fourth author (ANO) who is the head of the odontology and scientific affairs section, may raise questions related to competing interests. However, ANO aimed at understanding user needs in order to develop products and solutions for improved oral health in socioeconomically distressed communities. TePe Oral Hygiene Products represented by ANO had no financial gains through the participation in the research project. The representative from Apotek Hjärtat, private pharmacy, was a trained pharmacist who participated in some of the sessions to inform the participants about the oral health-related side effects of different medications such as dry mouth and how these can be prevented or treated. They did not have any financial gains from their participation in this study. A representative from the non-profit organisation, Save the Children, participated in all the sessions with an intention to offer children and mothers in the group social support and counselling if sensitive issues were discussed. They also informed the participants concerning child rights. The representative from the Primary Care (Region Skåne) was a dietist who was active in the sessions where diet was the subject of discussion, as well as in the development of the brochures.

Patient and public involvement: Patients and/or the public were involved in the design, or conduct, or reporting, or dissemination plans of this research. Refer to the Methods section for further details.

Patient consent for publication: Not required.

Ethics approval: The Regional Ethical Review Board in Lund approved the study (DNR 2016/824).

Provenance and peer review: Not commissioned; externally peer reviewed.

Data availability statement: Data are available upon reasonable request. The audio recordings from the focus groups generated and analysed during the current study are not publicly available due to institutional policy and GDPR regulations but are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

References

- 1.Swedish Board for Health and Welfare Tandvård: rekommendationer, bedömningar och sammanfattning, Nationell utvärdering. Vasterås: Socialstyrelsen, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Koch G, Helkimo AN, Ullbro C. Caries prevalence and distribution in individuals aged 3-20 years in Jönköping, Sweden: trends over 40 years. Eur Arch Paediatr Dent 2017;18:363–70. 10.1007/s40368-017-0305-9 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Hjern A, Grindefjord M, Sundberg H, et al. Social inequality in oral health and use of dental care in Sweden. Community Dent Oral Epidemiol 2001;29:167–74. 10.1034/j.1600-0528.2001.290302.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Christensen LB, Twetman S, Sundby A. Oral health in children and adolescents with different socio-cultural and socio-economic backgrounds. Acta Odontol Scand 2010;68:34–42. 10.3109/00016350903301712 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Julihn A, Ekbom A, Modéer T. Migration background: a risk factor for caries development during adolescence. Eur J Oral Sci 2010;118:618–25. 10.1111/j.1600-0722.2010.00774.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Molarius A, Engström S, Flink H, et al. Socioeconomic differences in self-rated oral health and dental care utilisation after the dental care reform in 2008 in Sweden. BMC Oral Health 2014;14:134. 10.1186/1472-6831-14-134 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Wennhall I, Matsson L, Schröder U, et al. Caries prevalence in 3-year-old children living in a low socio-economic multicultural urban area in southern Sweden. Swed Dent J 2002;26:167–72. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Cooper LA, Hill MN, Powe NR. Designing and evaluating interventions to eliminate racial and ethnic disparities in health care. J Gen Intern Med 2002;17:477–86. 10.1046/j.1525-1497.2002.10633.x [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Patrick DL, Lee RSY, Nucci M, et al. Reducing oral health disparities: a focus on social and cultural determinants. BMC Oral Health 2006;6 Suppl 1:S4. 10.1186/1472-6831-6-S1-S4 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Andersson K, Furhoff A-K, Nordenram G, et al. 'Oral health is not my department'. perceptions of elderly patients' oral health by general medical practitioners in primary health care centres: a qualitative interview study. Scand J Caring Sci 2007;21:126–33. 10.1111/j.1471-6712.2007.00446.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Hallberg U, Klingberg G. Medical health care professionals' assessments of oral health needs in children with disabilities: a qualitative study. Eur J Oral Sci 2005;113:363–8. 10.1111/j.1600-0722.2005.00238.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Jatrana S, Crampton P, Filoche S. The case for integrating oral health into primary health care. N Z Med J 2009;122:43–52. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Watt RG, Sheiham A. Integrating the common risk factor approach into a social determinants framework. Community Dent Oral Epidemiol 2012;40:289–96. 10.1111/j.1600-0528.2012.00680.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Marmot SM. Closing the health gap in a generation: the work of the Commission on social determinants of health and its recommendations. Glob Health Promot 2009;16:23–7. 10.1177/1757975909103742 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Health 2020 A European policy framework and strategy for the 21st century. Copenhagen: World Health Organization. Regional Office for Europe, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- 16.Marmot M, Ryff CD, Bumpass LL, et al. Social inequalities in health: next questions and converging evidence. Soc Sci Med 1997;44:901–10. 10.1016/S0277-9536(96)00194-3 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Sabbah W, Tsakos G, Chandola T, et al. Social gradients in oral and general health. J Dent Res 2007;86:992–6. 10.1177/154405910708601014 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Thorman R, Neovius M, Hylander B. Clinical findings in oral health during progression of chronic kidney disease to end-stage renal disease in a Swedish population. Scand J Urol Nephrol 2009;43:154–9. 10.1080/00365590802464817 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Stensson M, Wendt L-K, Koch G, et al. Oral health in preschool children with asthma. Int J Paediatr Dent 2008;18:243–50. 10.1111/j.1365-263X.2008.00921.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Rydén L, Buhlin K, Ekstrand E, et al. Periodontitis increases the risk of a first myocardial infarction: a report from the PAROKRANK study. Circulation 2016;133:576–83. 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.115.020324 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Koch G, Poulsen S, Espelid I, et al. Pediatric dentistry:a clinical approach. Copenhagen: John Wiley & Sons, 2017: 316–33. [Google Scholar]

- 22.Winning L, Patterson CC, Neville CE, et al. Periodontitis and incident type 2 diabetes: a prospective cohort study. J Clin Periodontol 2017;44:266–74. 10.1111/jcpe.12691 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Petersen PE, Bourgeois D, Ogawa H, et al. The global burden of oral diseases and risks to oral health. Bull World Health Organ 2005;83:661–9.doi:/S0042-96862005000900011 [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Chalub LLFH, Ferreira RC, Vargas AMD. Influence of functional dentition on satisfaction with oral health and impacts on daily performance among Brazilian adults: a population-based cross-sectional study. BMC Oral Health 2017;17:112. 10.1186/s12903-017-0402-5 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Gerritsen AE, Allen PF, Witter DJ, et al. Tooth loss and oral health-related quality of life: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Health Qual Life Outcomes 2010;8:126. 10.1186/1477-7525-8-126 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Locker D, Allen F. What do measures of 'oral health-related quality of life' measure? Community Dent Oral Epidemiol 2007;35:401–11. 10.1111/j.1600-0528.2007.00418.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Harris R, Nicoll AD, Adair PM, et al. Risk factors for dental caries in young children: a systematic review of the literature. Community Dent Health 2004;21:71–85. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Levine R, Stillman-Lowe C. Diet and Oral Health : The scientific basis of oral health education. 8th edn London: Springer Nature, 2019: 29–36. [Google Scholar]

- 29.Palmer CA. Important relationships between diet, nutrition, and oral health. Nutrition in Clinical Care 2001;4:4–14. 10.1046/j.1523-5408.2001.00101.x [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Cappelli DP, Mobley CC. Association between sugar intake, oral health, and the impact on overall health: raising public awareness. Curr Oral Health Rep 2017;4:176–83. 10.1007/s40496-017-0142-2 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Hardy LL, Bell J, Bauman A, et al. Association between adolescents' consumption of total and different types of sugar-sweetened beverages with oral health impacts and weight status. Aust N Z J Public Health 2018;42:22–6. 10.1111/1753-6405.12749 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Benjamin RM. Oral health: the silent epidemic. Public Health Rep 2010;125:158–9. 10.1177/003335491012500202 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Hobdell M, Petersen PE, Clarkson J, et al. Global goals for oral health 2020. Int Dent J 2003;53:285–8. 10.1111/j.1875-595X.2003.tb00761.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.André Kramer A-C. On dental caries and socioeconomy in Swedish children and adolescents-Clinical and register-based studies. Gothenburg: University of Gothenburg. Sahlgrenska Academy, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- 35.Phantumvanit P, Makino Y, Ogawa H, et al. WHO global consultation on public health intervention against early childhood caries. Community Dent Oral Epidemiol 2018;46:280–7. 10.1111/cdoe.12362 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Guarnizo-Herreño CC, Watt RG, Garzón-Orjuela N, et al. Explaining oral health inequalities in European welfare state regimes: the role of health behaviours. Community Dent Oral Epidemiol 2019;47:40–8. 10.1111/cdoe.12420 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Karlberg GL, Ringsberg KC. Experiences of oral health care among immigrants from Iran and Iraq living in Sweden. Int J Qual Stud Health Well-being 2006;1:120–7. 10.1080/17482620600679688 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Stecksén-Blicks C, Hasslöf P, Kieri C, et al. Caries and background factors in Swedish 4-year-old children with special reference to immigrant status. Acta Odontol Scand 2014;72:852–8. 10.3109/00016357.2014.914569 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Wallerstein N, Theoretical Duran B. The historical and practice roots of CBPR : Community based participatory research for health: advancing social and health equity. 3rd edn San Francisco: Jossey-Bass, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- 40.Abma TA, Cook T, Rämgård M, et al. Social impact of participatory health research: collaborative non-linear processes of knowledge mobilization. Educ Action Res 2017;25:489–505. 10.1080/09650792.2017.1329092 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Colditz GA, Emmons KM, Vishwanath K, et al. Translating science to practice: community and academic perspectives. J Public Health Manag Pract 2008;14:144–9. 10.1097/01.PHH.0000311892.73078.8b [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Paradiso de Sayu R, Chanmugam A. Perceptions of Empowerment within and across partnerships in community-based participatory research: a Dyadic interview analysis. Qual Health Res 2016;26:105–16. 10.1177/1049732315577606 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Torres S, Labonté R, Spitzer DL, et al. Improving health equity: the promising role of community health workers in Canada. Healthc Policy 2014;10:73–85. 10.12927/hcpol.2014.23983 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Wells KJ, Luque JS, Miladinovic B, et al. Do community health worker interventions improve rates of screening mammography in the United States? A systematic review. Cancer Epidemiol Biomarkers Prev 2011;20:1580–98. 10.1158/1055-9965.EPI-11-0276 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Hallin POG, Rasmusson Manne. Markus:Utsatta områden -sociala risker, kollektiv förmåga och oönskade händelser. Stockholm: Nationella operativa avdelningen, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- 46.Lindström M, Hanson BS, Ostergren PO. Socioeconomic differences in leisure-time physical activity: the role of social participation and social capital in shaping health related behaviour. Soc Sci Med 2001;52:441–51. 10.1016/S0277-9536(00)00153-2 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Lindström M, Moghaddassi M, Merlo J. Social capital and leisure time physical activity: a population based multilevel analysis in Malmö, Sweden. J Epidemiol Community Health 2003;57:23–8. 10.1136/jech.57.1.23 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Reich MR. Public-Private partnerships for public health. 1, 2002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.McDonnell S, Bryant C, Harris J, et al. The private partners of public health: public-private alliances for public good. Prev Chronic Dis 2009;6:A69. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Freire P. To the coordinator of a" cultural circle". Convergence 1971;4:61. [Google Scholar]

- 51.Hummelvoll JK. The Multistage Focus Group Interview A Relevant And Fruitful - Method In Action research based on a co-operative inquiry perspective. Norsk Tidsskrift for Sykepleieforskning 2008;10:3–14. [Google Scholar]

- 52.Heidemann ITSB, Almeida MCP. Friere's dialogic concept enables family health program teams to incorporate health promotion. Public Health Nurs 2011;28:159–67. 10.1111/j.1525-1446.2010.00898.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Collins CC, Villa-Torres L, Sams LD, et al. Framing young Childrens oral health: a participatory action research project. PLoS One 2016;11:e0161728. 10.1371/journal.pone.0161728 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Wang C, Burris MA. Photovoice: concept, methodology, and use for participatory needs assessment. Health Educ Behav 1997;24:369–87. 10.1177/109019819702400309 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Thomas R. Reflective dialogue parent education design: focus on parent development. Fam Relat 1996;45:189–200. 10.2307/585290 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Thomas DR. A general inductive approach for analyzing qualitative evaluation data. Am J Eval 2006;27:237–46. 10.1177/1098214005283748 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Neal JW, Neal ZP, VanDyke E, et al. Expediting the analysis of qualitative data in evaluation: a procedure for the rapid identification of themes from audio recordings (RITA). Am J Eval 2015;36:118–32. [Google Scholar]

- 58.Halcomb EJ, Davidson PM. Is verbatim transcription of interview data always necessary? Appl Nurs Res 2006;19:38–42. 10.1016/j.apnr.2005.06.001 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Taylor B, Henshall C, Kenyon S, et al. Can rapid approaches to qualitative analysis deliver timely, valid findings to clinical leaders? a mixed methods study comparing rapid and thematic analysis. BMJ Open 2018;8:e019993. 10.1136/bmjopen-2017-019993 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Guba EG, Lincoln YS. Fourth generation evaluation. Sage, 1989. [Google Scholar]

- 61.Muhammad M, Wallerstein N, Sussman AL, et al. Reflections on researcher identity and power: the impact of Positionality on community based participatory research (CBPR) processes and outcomes. Crit Sociol 2015;41:1045–63. 10.1177/0896920513516025 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Zimmerman MA. Psychological empowerment: issues and illustrations. Am J Community Psychol 1995;23:581–99. 10.1007/BF02506983 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Kushner RF. Barriers to providing nutrition counseling by physicians: a survey of primary care practitioners. Prev Med 1995;24:546–52. 10.1006/pmed.1995.1087 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Kemmis S, McTaggart R, Nixon R. The action research planner: doing critical participatory action research. Springer Science & Business Media, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- 65.Gibbs L, Waters E, Christian B, et al. Teeth tales: a community-based child oral health promotion trial with migrant families in Australia. BMJ Open 2015;5:e007321. 10.1136/bmjopen-2014-007321 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Borek AJ, Abraham C. How do small groups promote behaviour change? an integrative conceptual review of explanatory mechanisms. Appl Psychol Health Well Being 2018;10:30–61. 10.1111/aphw.12120 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Schunk DH. Peer Models and Children’s Behavioral Change. Rev Educ Res 1987;57:149–74. 10.3102/00346543057002149 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Rugut EJ, Osman AA. Reflection on Paulo Freire and classroom relevance. Am Int J Soc Sci 2013;2:23–8. [Google Scholar]

- 69.Tengland P-A. Behavior change or Empowerment: on the ethics of Health-Promotion strategies. Public Health Ethics 2012;5:140–53. 10.1093/phe/phs022 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Sherif-Trask B. Families in the Islamic Middle East : Families in global and multicultural perspective. 2nd Edition London: Sage, 2006: 231–46. [Google Scholar]

- 71.Frederick Littrell R, Bertsch A. Traditional and contemporary status of women in the patriarchal belt. Equality, Diversity and Inclusion: An International Journal 2013;32:310–24. 10.1108/EDI-12-2012-0122 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.