Abstract

Epstein-Barr virus (EBV) is associated with multiple human malignancies. To evade immune detection, EBV switches between latent and lytic programs. How viral latency is maintained in tumors or in memory B-cells, the reservoir for lifelong EBV infection, remains incompletely understood. To gain insights, we performed a human genome-wide CRISPR/Cas9 screen in Burkitt lymphoma B-cells. Our analyses identified a network of host factors that repress lytic reactivation, centered on the transcription factor MYC and including cohesins, FACT, STAGA and Mediator. Depletion of MYC or factors important for MYC expression reactivated the lytic cycle, including in Burkitt xenografts. MYC bound the EBV genome origin of lytic replication and suppressed its looping to the lytic cycle initiator BZLF1 promoter. Notably, MYC abundance decreases with plasma cell differentiation, a key lytic reactivation trigger. Our results suggest that EBV senses MYC abundance as a readout of B-cell state and highlights Burkitt latency reversal therapeutic targets.

Keywords: MYC, Epstein-Barr Virus latency reversal, viral latency, lytic reactivation, epigenetic silencing, viral genome, DNA tumor virus, lytic antigen, immediate early gene, DNA looping

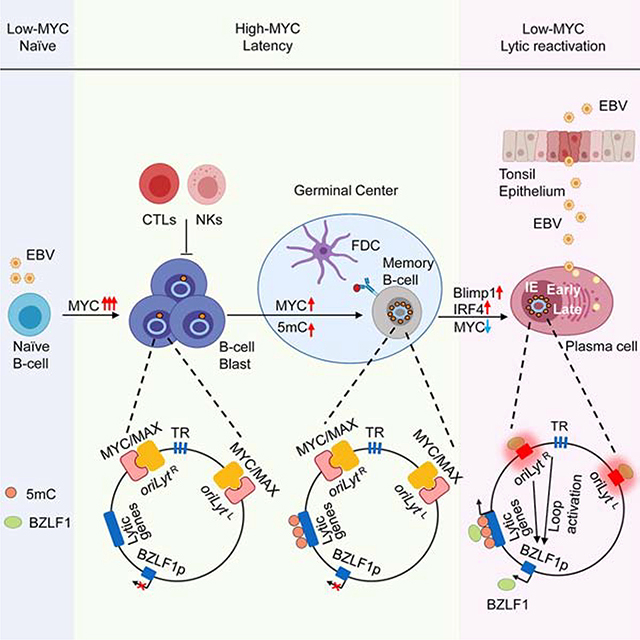

Graphical Abstract

Epstein-Barr virus infected Burkitt lymphomas evade immune detection by silencing all but one viral latency protein. Guo et al. utilize a CRISPR screen to identify MYC as a key suppressor of nearly 80 viral lytic antigens. MYC depletion causes three-dimensional viral genome remodeling, suggesting a sensor mechanism and therapeutic approaches.

INTRODUCTION

Epstein-Barr virus (EBV) persistently infects 95% of adults worldwide. To accomplish this remarkable task, EBV uses a biphasic life cycle, in which the viral genome switches between latent and lytic programs. Establishment of latency in a long-lived cellular niche and subsequent lytic reactivation in response to environmental cues is a hallmark of herpesvirus infection, yet much remains to be learned about how EBV accomplishes these important roles.

EBV is transmitted between hosts through saliva, from which it translocates across tonsillar epithelium to reach the B-cell compartment. Upon B-cell infection, the ~170 kilobase linear double-stranded EBV genome is delivered to the nucleus, where it is circularized and chromatinized. Rapid histone deposition serves to initially restrict expression of the nearly 70 EBV lytic antigens (Lieberman, 2013). Rather than produce infectious particles, EBV instead uses a series of latency programs to navigate the B-cell compartment.

Epstein-Barr Nuclear Antigens (EBNA) initially escape silencing. EBNA1 tethers viral genomes to host chromosomes, while EBNA 2, LP, 3A, 3B and 3C serve as transcription factors to regulate host and viral expression. This viral genome program strongly induces MYC and converts resting B-cells into proliferating blasts (Pich et al., 2019; Price and Luftig, 2015; Wang et al., 2019). Shortly thereafter, the viral genome switches to the latency III program, where these EBNA together with EBNA3 antigens and two Latent Membrane Proteins (LMP) further promote B-cell growth, survival and germinal center entry.

Immune pressure and incompletely characterized epigenetic re-programing further restrict latency gene expression, until Epstein-Barr Nuclear Antigen 1 (EBNA1) is the only viral protein expressed. This latency I program is observed in memory B-cells, the reservoir for lifelong EBV infection, and also in most EBV-infected Burkitt lymphoma (BL) tumors. Since EBNA1 has evolved low immunogenicity, B-cells with EBV latency I evade immune detection. Peripheral resting memory B-cells maintain EBV latency even in the absence of EBNA1 expression (Babcock et al., 2000), suggesting that epigenetic mechanisms involving host factors are important for the silencing of EBV lytic antigens.

By incompletely characterized mechanisms, plasma cell differentiation triggers EBV lytic reactivation (Laichalk and Thorley-Lawson, 2005), where infectious virion is produced for spread to nearby target cells. The EBV immediate early factor BZLF1 is a master regulator of the B-cell lytic cycle, and its induction is therefore highly regulated. While host factors that regulate BZLF1 expression have been identified, including the plasma cell master regulator Blimp1 (Reusch et al., 2015), much remains to be learned about how the EBV genome senses and responds to B-cell differentiation cues to induce BZLF1. Once expressed, BZLF1 triggers expression of ~30 early lytic genes, including the viral DNA polymerase, the processivity factor BMRF1, kinases and other factors important for lytic DNA replication. Newly replicated genomes serve as the template for most of the nearly 30 EBV late genes, whose expression allows DNA encapsulation, virion assembly and secretion. Potent immune responses are directed at EBV lytic antigens (Taylor et al., 2015).

Available anti-EBV small molecule therapies target EBV lytic cycle kinase and DNA polymerase (Meng et al., 2010). While lytic infection is increasingly implicated in the pathogenesis of EBV-associated cancers, latent infection is instead observed in most human B-cell and epithelial cancers malignancies. EBV is associated with 200,000 human cancers per year, including Burkitt and Hodgkin lymphoma, post-transplant lymphoproliferative disease, nasopharyngeal and gastric carcinomas. Therefore, there is considerable interest in strategies to reverse EBV latency in order to sensitize tumor cells to agents such as ganciclovir, whose phosphorylation by an EBV lytic cycle kinase induces toxicity to infected and even neighboring cells (Meng et al., 2010).

To identify epigenetic factors critical for maintenance of EBV latency, we performed a genome scale CRISPR/Cas9 loss-of-function screen in EBV+ Burkitt lymphoma cells, the available B-cell latency I infection model. Our results identify MYC as a major regulator of the B-cell EBV lytic switch.

RESULTS

CRISPR/Cas9 Screen for Repressors of EBV Lytic Reactivation

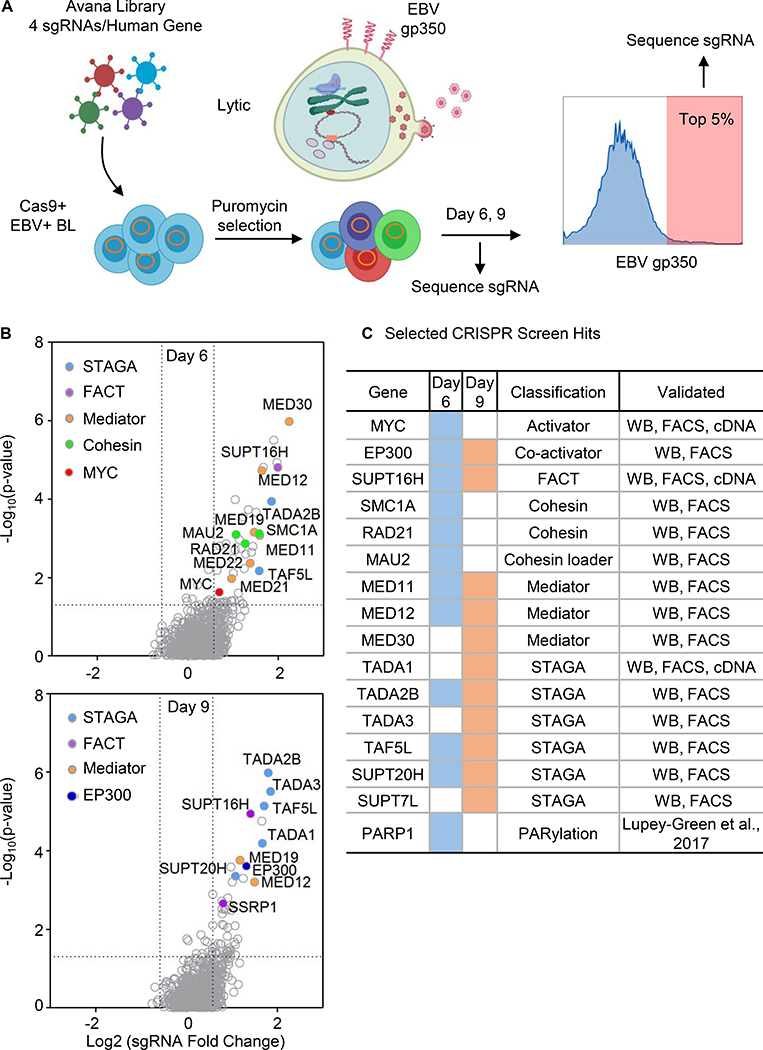

The EBV late lytic gene product gp350 decorates the plasma membrane of B-cells undergoing viral replication, but is absent from cells with latent EBV infection (Thorley-Lawson, 2015). We reasoned that gp350 abundance could be used as a physiologically relevant reporter of CRISPR/Cas9 targets, whose knockout (KO) induced EBV lytic reactivation. Biological replicates of an EBV-infected Burkitt lymphoma (BL) knockout library were generated by transducing Cas9+ P3HR-1 cells with the Avana lentiviral single-guide RNA (sgRNA) library. Avana contains four independent sgRNAs that target distinct regions of each human protein coding gene (Figure 1A) (Doench et al., 2016).

Figure. 1. CRISPR Screen for Host Suppressors of EBV Lytic Reactivation.

(A) CRISPR screen workflow. Cas9+ P3HR-1 were transduced with the Avana sgRNA library and sorted for the top 5% cells with plasma membrane (PM) EBV lytic antigen gp350 expression. Lentivirus-integrated sgRNA abundances from input versus sorted cells were quantitated.

(B) Volcano plots showing the -Log10 (p-value) and Log2 fold-change of sgRNA abundance in input versus Day 6 (top) or Day 9 output (bottom). Selected screen hit categories are highlighted.

(C) Selected screen hits organized by category. Day 6 and 9 hits are indicated by blue versus orange coloring, respectively. Screen hit validation are indicated. PARP1 was reported as a repressor of EBV lytic reactivation (Lupey-Green et al., 2017). See also Figure S1.

Fluorescence associated cell sorting (FACS) was used to purify live gp350+ cells at 6 and 9 days post-transduction (Figure 1A). Two time points were used, since hits might induce lytic induction with distinct kinetics. Input versus sorted cell sgRNA abundances were quantitated by PCR amplification and next-generation sequencing. The STARS algorithm, which integrates data from independent guides targeting the same gene, was used to identify statistically significant hits (Doench et al., 2016). Using a p value < 0.05 and fold change > 1.5 cutoff, 85 and 72 hits were identified at Day 6 versus 9 post-transduction, respectively (Figure 1B and 1C and Table S1).

Screen hits were highly enriched for nuclear epigenetic regulators (29.6% of total Day 6 and 9 common hits), including genes encoding the transcription factor MYC, the histone acetyltransferase EP300, multiple components of the mediator and the STAGA/GCN5 acetyltransferase complex, both FACT complex subunits, two cohesin subunits and a cohesin loader. Notably, Mediator scored more strongly on Day 6, whereas STAGA subunits all scored more strongly on day 9, perhaps reflecting different rates of decay of these multiprotein complexes following gene knockout and effects on cell fitness (Figure S1A). Selected hits from each complex were validated by immunoblot and FACS assays (Figure 1). sgRNAs targeting genes encoding STAGA, FACT, Mediator or cohesin subunits each induced EBV early lytic gene BMRF1 expression (Figure S1B). Similarly, gp350 plasma membrane expression was upregulated by screen hit sgRNAs (Figure S1C). Collectively, these results raised the possibility that multiple screen hits are nuclear factors that have interrelated roles in the maintenance of EBV latency in BL.

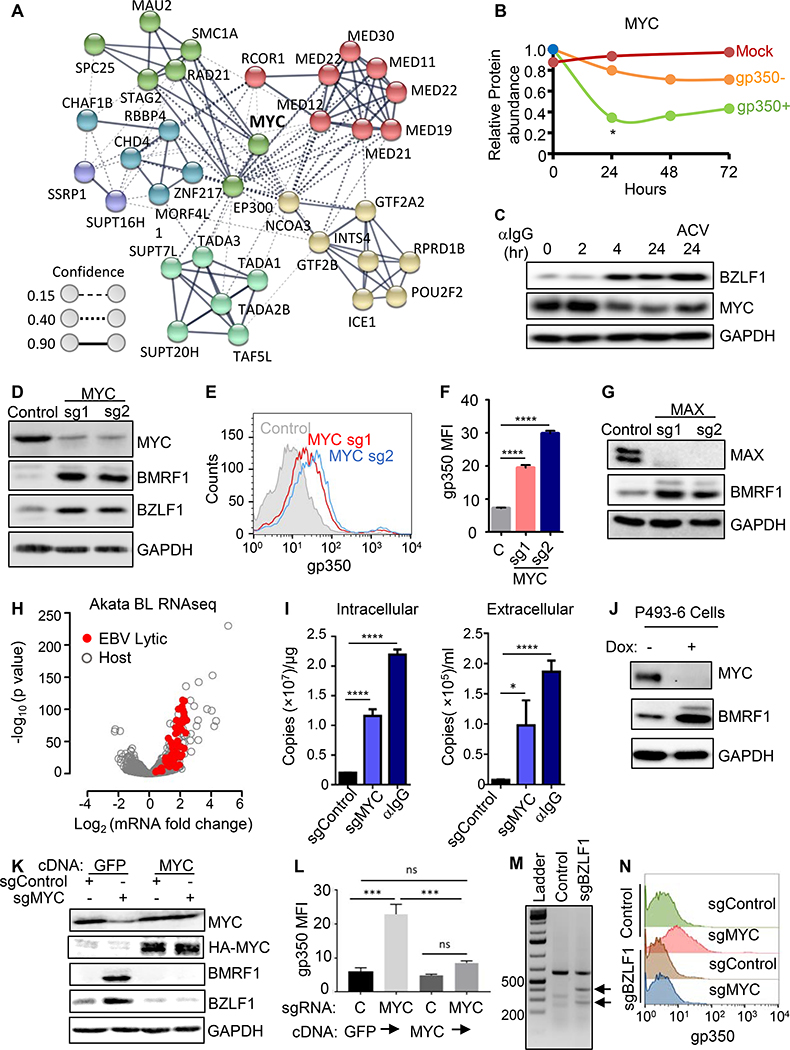

MYC is Necessary for BL Maintenance of EBV Latency

Bioinformatic analysis highlighted that many top screen hits could be organized into an interaction network, centered on MYC (Figure 2A). This result raised the question of whether MYC, which is highly EBV-induced upon primary B-cell infection, could be a central regulator of EBV latency. By contrast, using a temporal proteomic map of EBV lytic replication (Ersing et al., 2017), we observed that MYC protein abundance was significantly diminished in BL cells induced for EBV lytic replication (Figure 2B and S2A), which we confirmed by immunoblot (Figure 2C).

Figure 2. MYC is a Major Repressor of EBV Lytic Antigen Expression in BL cells.

(A) STRING network analysis (Szklarczyk et al., 2017) of selected hits, centered on MYC. Edges represent protein-protein associations. Confidence scores, which are scaled between 0–1, indicate the strength of data support. Confidence score values indicate the estimated likelihood that a given interaction is biologically meaningful, specific and reproducible.

(B) Relative MYC protein abundances of P3HR-1 mock-induced (red) or induced for lytic activation by addition of 4-hydroxytamoxifen, which activates nuclear translocation of a conditional BZLF1 allele. MYC abundances in 4HT-treated and FACSorted gp350+ (green) versus negative (orange) cells are shown. p < 0.05, data are from (Ersing et al., 2017).

(C) Immunoblot analysis of whole cell lysates (WCL) from EBV+ Akata BL with anti-human IgG (αIgG, 10μg/ml) for the indicated hours (hr), with acyclovir (100 μg/ml) as shown.

(D) Immunoblots of WCL from Akata cells with control or MYC sgRNAs.

(E) FACS analysis of plasma membrane (PM) gp350 expression in Akata with indicated sgRNAs.

(F) Mean + stand deviation (SD) PM gp350 mean fluorescence intensity (MFI) from n=3 replicates of Akata, as in (E). **** p < 0.0001.

(G) Immunoblots of Akata with indicated sgRNAs.

(H) Volcano plot comparing RNAseq values from Akata with control or MYC sgRNAs. -Log10 (p-value) and Log2 (mRNA abundance fold change) from n=3 replicates. Significantly changed EBV lytic genes shown in red.

(I) qRT-PCR of EBV intracellular or DNAse-treated extracellular genome copy number from Akata with control or MYC sgRNA. Mean + SD values from n=3 replicates are shown. ****p < 0.0001, ***p < 0.001.

(J) Immunoblots of WCL from p493–6 after 24 hours of vehicle or doxycycline (1 μg/ml). See also Fig S2E.

(K) Immunoblot analysis of WCL from Akata expressing GFP or HA-tagged MYC and the indicated sgRNAs.

(L) Mean + SD PM gp350 MFI values from n=3 replicates of Akata with indicated cDNAs and sgRNAs, as in (K). *** p < 0.001.

(M) T7E1 analysis of Cas9-mediated BZLF1 editing. Representative T7E1 nuclease-treated PCR products are shown.

(N) PM gp350 abundances in Akata with indicated sgRNAs.

Blots are representative of n=3 replicates. See also Figure S2.

To gain insights into how MYC may repress B-cell EBV lytic reactivation, we first tested the effects of independent screen hit sgRNAs on MYC and EBV lytic gene expression in P3HR-1 and Akata BL cell lines. P3HR-1 harbors type II EBV, whereas Akata has the more prevalent type I EBV strain. Expression of either sgRNA depleted MYC and robustly induced immediate early BZLF1 and early BMRF1 expression by 72 hours post-puromycin selection in both cell lines, a timepoint prior to when MYC depletion triggers BL cell death (Figure 2D, S2B). MYC KO induced plasma membrane gp350 late antigen expression in live BL cells (Figures 2E–F).

MYC binds DNA as a heterodimer with one of several transcription factor partners, most commonly as a transcription activator when in complex with MAX, or instead as a repressor when in complex with MIZ1. Independent sgRNAs depleted MAX expression and induced early gene BMRF1 and late gene gp350 expression (Figure 2G). Similarly, the small molecule inhibitor KJ-PYR-9, which blocks MYC and MAX heterodimerization (Hart et al., 2014), induced gp350 expression in P3HR-1 cells (Figure S2C). These data suggest that a MYC/MAX heterodimer is important for the maintenance of EBV latency in BL cells.

To further characterize the effects of MYC depletion on BL EBV lytic gene expression, we performed RNAseq analysis of Akata transcripts following expression of control or MYC targeting sgRNAs. 77 EBV lytic cycle genes were significantly induced and were amongst the most strongly upregulated by MYC depletion (Figure 2H, Table S2). While EBNA1 can inhibit EBV lytic induction, MYC depletion increased EBNA1 mRNA and protein abundance (Figure S2D). Induction of EBV lytic gene expression by independent MYC-targeting sgRNAs was validated by qPCR (Figure S2E). To determine whether MYC depletion stimulates viral genome replication, viral load analysis was done using BL with control or anti-MYC sgRNAs. MYC targeting increased EBV genome copy number, with intracellular and DNase-treated extracellular viral loads approaching levels achieved by anti-IgG cross-linking (Figure 2I). Resistance of extracellular EBV genomes to DNase treatment suggests that these genomes were encapsulated and likely secreted as virus particles.

We next asked whether MYC suppresses lytic gene expression in lymphoblastoid B-cells (LCLs) with latency III expression, where EBV super-enhancers induce MYC expression (Jiang et al., 2017) to lower levels than in BL. MYC targeting in GM12878 LCLs, which have an untranslocated MYC locus, induced BZLF1, and to a lesser extent BMRF1 expression (Figure S2F). Notably, LCL TET2 demethylase limits the ability of BZLF1 to induce EBV early genes (Lu et al., 2017; Wille et al., 2017). We then tested effects of conditional MYC inactivation in p493 LCLs, which have conditional MYC and EBNA2 alleles (Schuhmacher et al., 2001). Cells were grown in the absence of doxycycline or 4-hydroxytamoxifen (4HT), where high levels of the exogenous MYC allele simulate BL physiology (Schuhmacher et al., 2001)(Figures 2J and S2G). Doxycycline addition suppressed MYC and induced EBV lytic transcripts (Figure S2H).

To confirm that on-target MYC editing caused lytic re-activation, we stably expressed sgRNA-resistant rescue cDNA encoding HA-tagged MYC or GFP. HA-MYC blocked induction of BZLF1, BMRF1 or gp350 upon Cas9 targeting of endogenous MYC in Akata BL or GM12878 LCL (Figures 2K–L and S2I–K). Consistent with prior reports that MYC cDNA over-expression suppresses leaky lytic antigen expression in LCLs (Cutrona et al., 1995; Fais et al., 1996), stable MYC expression significantly impaired BZLF1 and gp350 induction by anti-IgG cross-linking of Akata cells (Figure S2L). We next asked whether BZLF1 is required for induction of EBV lytic gene expression by MYC depletion. Functional BZLF1 knockout Akata cells were generated by CRISPR, validated by T7 assay and by demonstration of impaired lytic response to anti-IgG challenge (Figure 2M and S2M), and then were challenged by MYC knockout. MYC depletion triggered gp350 expression in control, but not BZLF1-edited Akata (Figure 2N), suggesting that MYC acts at the level of BZLF1 to control the EBV lytic cycle.

BZLF1 can activate its own promoter, the immediate early EBV BRLF1 promoter, or together with BRLF1 EBV early gene promoters (Kenney and Mertz, 2014). Since MYC can block BZLF1-mediated transcriptional activation in epithelial cells (Lin et al., 2004), we used two conditional BZLF1 expression systems to gain insights into the level at which MYC inhibits BZLF1 effects on BL EBV lytic genes. First, we tested the effect of lentivirus-driven MYC on BL with doxycycline-inducible HA-epitope tagged BZLF1 expression. Conditional HA-BZLF1 upregulated BMRF1 and gp350 (Figure S3A) to similar levels in BL cells with GFP versus MYC expression, consistent with bypass of EBV genomic BZLF1 promoter inhibition by MYC. We then asked whether lentivirus-driven MYC can block BZLF1 autoactivation of the EBV genome BZLF1 promoter, using P3HR-1 cells that stably express a BZLF1 4HT-binding domain fusion protein (BZLF1-HT). In the absence of 4HT, BZLF1-HT is retained in the cytosol, whereas it translocates to the nucleus and activates target genes upon 4HT addition. Conditional BZLF1-HT activation by 4HT induced untagged EBV genomic BZLF1 and BMRF1 at similar levels in cells with control GFP and MYC over-expression (Figure S3B). 4HT also significantly induced gp350 expression in cells with GFP vs MYC over-expression, albeit to a lesser extent in the presence of HA-MYC. These results suggest MYC acts at the level of the BZLF1 promoter.

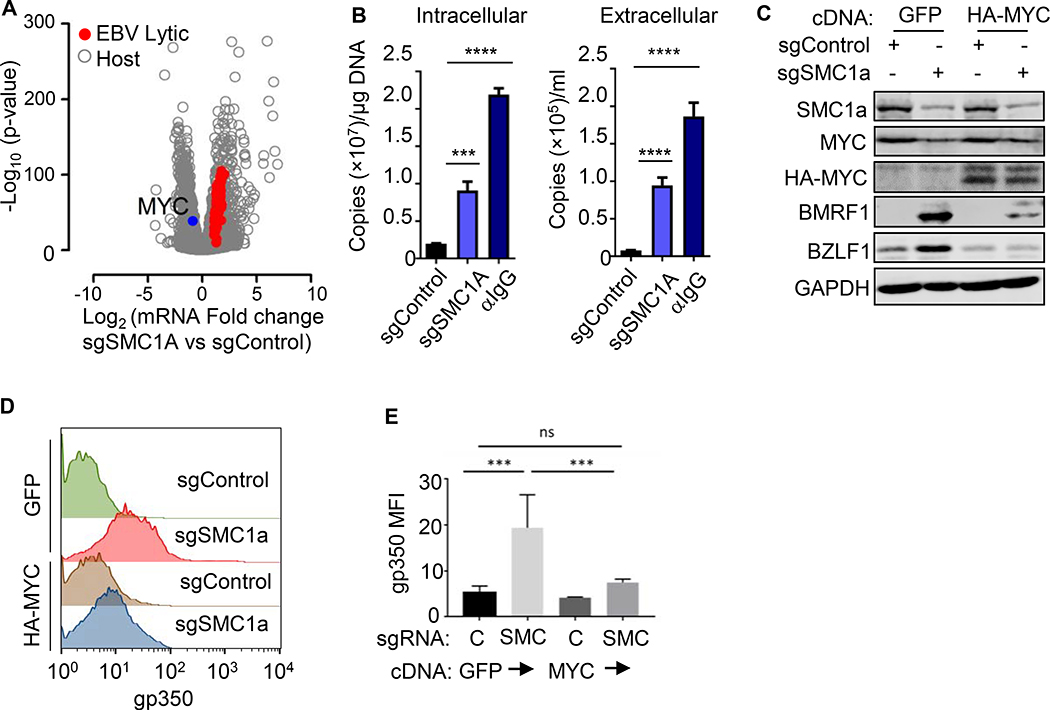

The Cohesin SMC1A is Important for BL MYC Expression and EBV Latency

The cohesins SMC1A and RAD21 are implicated in control of Kaposi Sarcoma Associated Herpesvirus lytic reactivation (Chen et al., 2012; Li et al., 2014). To investigate a possible common gamma-herpesvirus role, we validated that Avana SMC1A sgRNAs induced EBV lytic genes (Figure S3C–F). SMC1A depletion induced expression of 77 EBV lytic genes (Figure 3A) and increased intracellular and DNase-resistant extracellular EBV genome copy number, suggestive of lytic replication (Figure 3B and Table S3). SMC1A depletion effects on BL fitness likely account for the lower CRISPR screen signal at Day 9, though surviving cells continued to expressed gp350 at Day 9 (Figure S3C).

Figure 3. The Cohesin SMC1 Supports MYC Expression and Restricts EBV Lytic Genes.

(A) Volcano plot of -Log10 (p-value) and Log2 (mRNA abundance fold change) in Akata with control or SMC1A sgRNAs from n=3 RNA-seq. Upregulated EBV lytic gene (red) and downregulated MYC (blue) are shown.

(B) qRT-PCR of EBV intracellular versus DNAse-treated extracellular genome copy number from Akata with control or SMC1A sgRNA at Day 6 post-transduction or 48h post anti-IgG stimulation (10 μg/ml). Mean + SD values from n=3 replicates are shown; ****p < 0.0001, ***p < 0.001.

(C) Immunoblot analysis of WCL from Akata with the indicated GFP, HA-MYC and sgRNA expression.

(D) FACS of PM gp350 levels in Akata with the indicated GFP, HA-MYC and sgRNA expression.

(E) Mean + SD values of PM gp350 MFI from n=3 replicates of Akata, as in 3D. ****p < 0.0001. See also Figure S3.

SMC1A depletion down-modulated MYC mRNA by nearly 2-fold (Figure 3A), consistent with cohesin roles in MYC promoter regulation (Rhodes et al., 2011). Notably, MYCm RNA and protein are highly labile, with half-lives of 20–30 minutes (Farrell and Sears, 2014). Even in BL with stabilizing MYC mutations (Gregory and Hann, 2000), MYC half-life remains short, and MYC must be continually replenished. We therefore tested whether lentivirus-driven MYC cDNA expression could prevent lytic induction triggered by SMC1A depletion. MYC over-expression diminished BZLF1, BMRF1 and gp350 levels in SMC1a edited cells (Figures 3C–E). While additional roles in EBV latency maintenance are plausible, these data suggest that SMC1A controls EBV latency at least in part by supporting MYC expression.

FACT Supports BL MYC Expression and EBV Latency in vitro and in vivo

The facilitated chromatin transcription (FACT) complex, comprised of SUPT16H and SSRP1 subunits, enables RNA polymerase processivity by remodeling histones at sites of active transcription (Belotserkovskaya et al., 2003; Saunders et al., 2003). Interestingly, cross-talk between FACT and MYC have been identified in multiple cell types as drivers of each other’s expression (Carter et al., 2015). It was therefore of interest that the SSRP1 and SUPT16H FACT subunits each scored as CRISPR screen hits (Figures 1, 2A, S4A–B). To gain insights into FACT roles in BL host and viral gene expression, we performed RNAseq on control versus SUPT16H depleted P3HR-1 cells. SUPT16H sgRNA suppressed MYC expression by 65%, induced 67 EBV lytic mRNAs (Figure 4A and Table S4) and lytic proteins (Figure S4D–E). SUPT16H sgRNA increased EBV genome copy number (Figure 4B), suggesting that FACT activity on host and/or viral genomes was important for maintenance of EBV latency. SUPT16H depletion in GM12878 LCLs induced EBV lytic gene expression (Figure 4C), suggesting a more general FACT role in cells with wildtype MYC loci. Notably, our recent proteomic analysis demonstrated that EBV upregulates SUPT16H and SSRP1 protein abundance upon primary B-cell infection (Figure S4C), consistent with an important FACT role in establishment of EBV latency, perhaps even from the earliest stages of B-cell infection.

Figure 4. FACT-driven MYC Expression is a Druggable Target for Lytic Reactivation.

(A) Volcano plot of -Log10 (p-value) and Log2 (mRNA fold-change) in Akata cells that express control or SUPT16H sgRNAs, using triplicate RNA-seq datasets. Values for significantly upregulated EBV lytic gene (red) and downregulated MYC (blue) mRNAs are highlighted.

(B) qRT-PCR analysis of EBV intracellular vs DNAse-treated extracellular genome copy number from Akata cells expressing control or SUPT16H sgRNAs at Day6 post lentivirus transduction or 48h post anti-IgG stimulation (10 ug/ml). Mean + SD values from n=3 replicates are shown. ****p < 0.0001, ***p < 0.001.

(C) Immunoblots of WCL from GM12878 LCLs expressing control or independent SUPT16H sgRNAs.

(D) FACS plots of PM gp350 abundance in Akata cells stably expressing GFP or HA-MYC cDNAs, together with control or SUPT16H sgRNAs, as indicated.

(E) Mean + SD PM gp350 MFI in Akata cells stably expressing GFP or HA-MYC cDNAs, together with control or SUPT16H sgRNAs, as indicated. Data are from n=3 replicates. ***p < 0.001; ns, not significant.

(F) Immunoblot analysis of WCL from Akata cells stably expressing cDNAs encoding GFP or HA-MYC together with control or SUPT16H sgRNAs, as indicated.

(G) Immunoblot analysis of WCL from MUTU1 cells which were treated with DMSO or the indicated concentrations of the FACT inhibitor CBL0137 for 6 hours, washed, and then cultured for an additional 42 hours.

(H) FACS plots showing MYC or PM gp350 abundances in MUTU I BL treated with DMSO control or 5 μM CBL0137 for 48 hours, as indicated.

(I) Schematic of murine BL xenograft experiments. Shown are the timepoints at which MUTU I xenografts were planted, at which vehicle control or CBL0137 were dosed, and when tumors were explanted for EBV lytic gene analysis.

(J) Volcano plot of -Log10 (p-value) vs Log2 (mRNA fold change) in xenograft tumors from DMSO or CBL0137 60 mg/kg IV tail vein injection. Data are from triplicate RNA-seq datasets. Values for upregulated EBV lytic genes (red) are highlighted.

(K) qRT-PCR analysis of EBV lytic gene mRNA abundances in tumors explanted 48 hours after DMSO, CBL0137 10 mg/kg or 60 mg/kg IV tail vein injection.

(L) Immunohistochemistry analysis showing BZLF1 expression in tumors explanted 48 hours following DMSO or CBL0137 60 mg/kg intravenous tail vein injection. C, F, G and H are representative of n=3 replicates. See also Figure S4.

We investigated whether FACT supports EBV latency through effects on MYC expression. Lentivirus-driven HA-MYC substantially blocked EBV lytic gene induction by SUPT16H KO (Figure 4D–F). FACT associates with MYC (Heidelberger et al., 2018), and additional FACT roles at the protein level may underlie the significant but incomplete rescue of lytic gene silencing by MYC over-expression. As was observed for MYC KO, SUPT16H sgRNA failed to induce gp350 in BZLF1 edited cells (Figure S4F), consistent with FACT and/or MYC roles in control of BZLF1.

The MYC family member N-MYC is a major driver of glioblastoma, where the curaxin small molecule FACT inhibitor CBL0137 blocks N-MYC expression, tumor initiation and progression in a mouse model (Carter et al., 2015). To investigate whether FACT might be a druggable target in BL EBV latency reversal, we tested CBL0137 effects on MYC and EBV lytic gene expression. CBL0137 depleted MYC and induced lytic antigens in BL and in LCLs established from three individuals (Figure 4G–H, S4G). Although CBL0137 has pleotropic effects on host cells, its BL and LCL effects on EBV lytic reactivation were suppressed by HA-MYC over-expression (Figure S4H), suggesting that MYC is the functionally relevant target. These data support a key FACT role in EBV latency.

We tested CBL0137 using a BL xenograft model, since latency I expression cannot typically be achieved in current humanized mouse EBV infection models. Following establishment of MUTU I BL tumors, mice were treated either with vehicle or CBL0137 at 10 or 60 mg/kg by tail vein injection (Figure 4I). 48 hours later, one group of mice were sacrificed and tumors were characterized by RNAseq. Remarkably, a single CBL0137 dose significantly induced expression expression of 77 EBV lytic genes in tumor xenografts (Figure 4J, Table S5). Dose-dependent xenograft induction of EBV lytic mRNAs was validated by qPCR (Figure 4K), and BZLF1 protein expression in numerous BL cells was evident (Figure 4L).

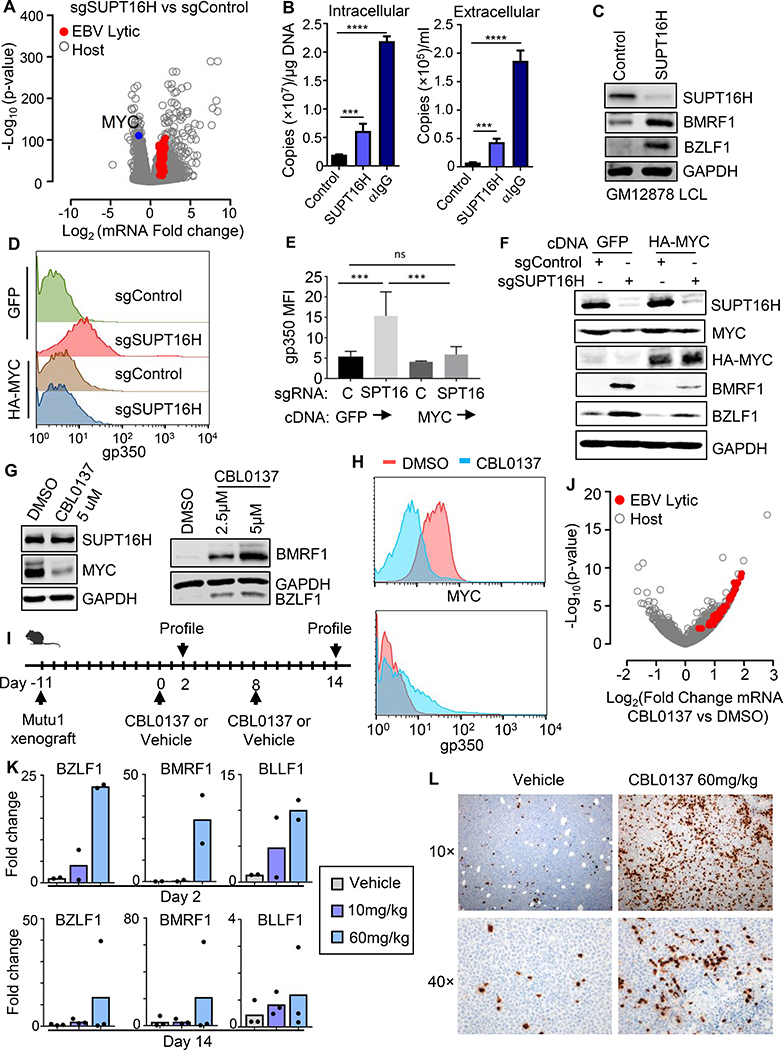

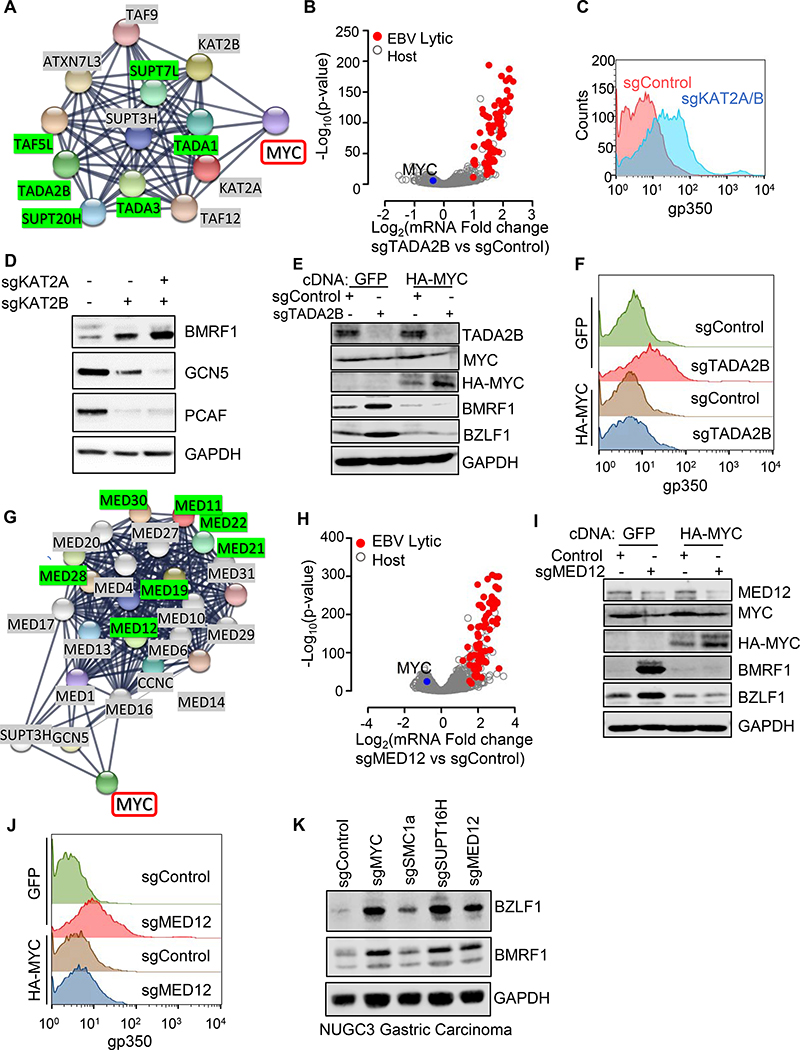

STAGA Acetyltransferase and Mediator Complex Maintain EBV Latency

Sequence-specific transcription factors including MYC recruit the STAGA/GCN5 histone acetyltransferase (HAT) to promote transcription initiation (Helmlinger and Tora, 2017). MYC and STAGA co-occupy many DNA sites (Hirsch et al., 2015; Wang and Dent, 2014; Zhang et al., 2014). It was therefore of interest that genes encoding six STAGA subunits were screen hits (Figures 1, 5A, S5A), mapping to three of four STAGA modules (Figure 5A and S5A). We confirmed that sgRNAs against genes encoding STAGA subunits TADA1 or TADA2B induced EBV lytic gene expression and viral DNA replication (Figure S5B–F) and validated on-target effects through TADA1 cDNA rescue (Figure S5G–H).

Figure 5. STAGA and Mediator Support MYC and Restrict EBV Lytic Expression in BL.

(A) STRING analysis of STAGA and MYC interactions. Edges represent protein-protein associations. STAGA complex screen hits highlighted in green. See also Figure S5A.

(B) Volcano plot of -Log10 (p-value) vs Log2 (mRNA fold-change) in Akata with indicated sgRNAs using n=3 RNAseq. Significantly upregulated EBV lytic gene (red) and downregulated MYC (blue) are shown.

(C) FACS PM gp350 levels in Akata with the indicated sgRNAs from n=3 replicates.

(D) Immunoblot of WCL from Akata with indicated sgRNA.

(E) Immunoblot of Akata with indicated cDNA and sgRNA.

(F) FACS plots of PM gp350 levels in Akata with indicated cDNA and sgRNA.

(G) STRING analysis of interactions between Mediator and MYC. Mediator screen hits highlighted in green. See also Figure S5A.

(H) Volcano plot of -Log10 (p-value) vs Log2 (mRNA fold-change) in Akata with indicated sgRNAs using n=3 RNAseq. Significantly upregulated EBV lytic gene (red) and downregulated MYC (blue) are shown.

(I) Immunoblot analysis of Akata with indicated cDNA and sgRNA.

(J) FACS PM gp350 abundances in Akata with indicated cDNA and sgRNA.

(K) Immunoblot analysis of WCL from Cas9+ NUGC3 gastric carcinoma cells expressing the indicated sgRNAs.

Blots are representative of n=3 replicates. See also Figure S5 and S6.

Components of the USP22 deubiquitylase (DUB) module did not score, suggesting that STAGA HAT activity may be crucial for latency maintenance. Yet, the KAT2A gene encoding the HAT catalytic subunit GCN5 was not a screen hit, even though GCN5 can stabilize MYC through lysine acetylation (Patel et al., 2004). We reasoned that BL co-expression of PCAF encoded by KAT2B, which functions interchangeably with GCN5, may have precluded either from scoring (Nagy and Tora, 2007). Indeed, co-expression of sgRNAs targeting KAT2A and KAT2B induced EBV lytic gene expression (Figure 5C–D). These data also raise the possibility that GCN5/PCAF activity may be a druggable target for EBV latency reversal.

As observed with other screen hits, TADA2B depletion suppressed MYC mRNA and induced lytic genes (Figure 5B and Table S6), whereas MYC over-expression suppressed lytic gene expression triggered by TADA2B KO (Figure 5E and S5I).

STAGA and MYC can each recruit Mediator, which bridges enhancer-bound sequence-specific transcription factors and promoter-bound RNA polymerase II (Allen and Taatjes, 2015; Wang et al., 2008). Components from three of the four Mediator modules scored, including two CDK8 kinase module subunits (Figure S6A–B). KO of CDK8 module subunit MED12 suppressed MYC expression, induced lytic genes and stimulated EBV genome replication (Figure 5G, S6C–E and Table S6). MYC over-expression rescued effects of MED12 KO on EBV lytic gene expression (Figures 5I–J and S6F). MED12 KO induced EBV lytic genes in LCLs (Figure S6G).

Suggestive of conserved roles in an epithelial cell line that is not known to have a translocated MYC locus, sgRNAs against MED12, MYC, SMC1A or SUPT16H induced BZLF1 and BMRF1 in EBV-infected gastric carcinoma NUGC3 cells. By contrast, CRISPR targeting of these screen hits paradoxically suppressed BMRF1 expression in NPC43 nasopharyngeal carcinoma cells, in which we observed abundant BZLF1 expression at baseline, suggestive of an abortive lytic environment that may bypass effects of MYC depletion on BZLF1 regulation (Figure S6H).

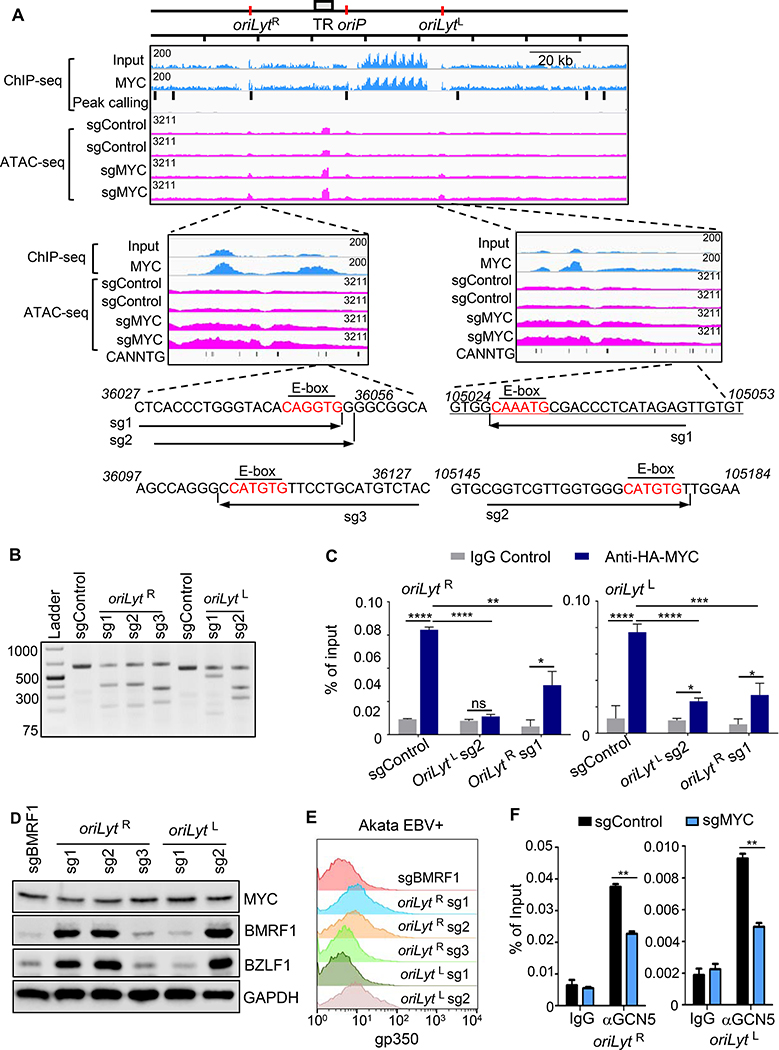

MYC-occupied EBV Genomic E-box Sites Are Key Latency Control Elements

To gain insights into how EBV senses MYC levels, and how this in turn supports maintenance of EBV latency, we analyzed B-cell MYC chromatin immunoprecipitation with deep sequencing (ChIP-seq) datasets. EBV genomic MYC occupancy was observed in Daudi BL near both origins of lytic replication (oriLyt) (Figure 6A). OriLyt initiate lytic viral genome replication and are enhancers, particularly when bound by BZLF1 (Djavadian et al., 2016; Hammerschmidt and Sugden, 1988; Ryon et al., 1993) (Figure 6A). MYC ChIP-seq signal in the left oriLyt (oriLytL) region may have been underestimated as a result of an EBV genomic deletion in this tumor-derived cell line. Using MYC ChIP-seq data from p493 EBV-infected B-cells with a conditional MYC allele (Lin et al., 2012), we also observed MYC occupancy at oriLyt upon MYC induction (Figure S7A).

Figure 6. MYC Occupancy of EBV Genome oriLyt E-Box Sites Maintains Latency in BL.

(A) ChIP-seq analysis of EBV genome MYC occupancy and ATAC-seq analysis of effects of MYC depletion on EBV genomic accessibility. Shown are Daudi BL EBV genome input and MYC ChIP-seq tracks. Background-subtracted peak calling identified seven significant EBV genomic peaks, highlighted by black bars. Values at top left indicate track heights. n=2 ATAC-seq tracks from Akata with indicated sgRNAs and treated with acyclovir (100 μg/ml). Zoomed tracks of oriLyt regions are shown. Akata EBV DNA sequences of sgRNA-targeted regions are shown, with E-boxes in red.

(B) T7E1 assay of Cas9 oriLyt region editing. Representative T7E1 nuclease-treated PCR products are shown.

(C) ChIP-qPCR of MYC oriLyt region occupancy. Ig-control or anti-HA ChIP was performed on chromatin from Akata with HA-MYC and indicated sgRNA expression. qPCR was done with E-box regions primers. Mean + SD are shown for n=3 replicates. ****p < 0.0001, **p < 0.001, **p<0.01.

(D) Immunoblot of WCL from Akata with indicated sgRNAs. Blot is representative of n=3.

(E) FACS PM gp350 abundances in Akata with indicated sgRNAs.

(F) ChIP-qPCR analysis of STAGA subunit GCN5 occupancy at oriLyt regions. αGCN5 ChIP was performed on chromatin from Akata with control or MYC sgRNAs, followed by qPCR using primers specific for oriLyt E-box regions. Mean + SD are shown for n=3 replicates. **p<0.01.

See also Figure S7.

We next asked how changes in MYC occupancy might alter EBV genomic chromatin accessibility, particularly at oriLyt regions. ATAC-seq was performed in Cas9+ Akata BL, in which both oriLyt are intact, following lytic induction by MYC sgRNA expression or αIgG cross-linking. Cells were cultured in acyclovir to block synthesis of unchromatinized, linear EBV genomes. Two MYC sgRNAs increased ATAC-seq signal at both oriLyt sites, and also increased signal at the nearby terminal repeat (TR) region (Figure 6A). Similar results were observed in the αIgG induced cells at 24 hours post-treatment (Figure S7B).

We therefore hypothesized that MYC occupancy of E-box sites near oriLyt may be necessary for EBV latency. To test this hypothesis, three sgRNAs were designed to target oriLyt R E-box sites (Figure 6A). Two of these (sg1 and sg2) target the same E-box site, whereas sg3 targets a downstream E-box. Similarly, sgRNAs were designed to target distinct oriLytL E-box sites. E-box targeting sgRNAs were individually expressed in Cas9+ Akata BL and resulted in efficient EBV genome editing, as judged by T7 endonuclease assay (Figure 6B). Sanger sequencing also showed on-target EBV genome editing (Figure S7C).

We next tested effects of EBV genome E-box editing on MYC occupancy and lytic gene expression. To optimize ChIP signals, HA-epitope tagged MYC was stably expressed in Cas9+ Akata. HA-ChIP-qPCR demonstrated MYC occupancy signal significantly above control levels at each oriLyt, consistent with MYC ChIP-seq results. Interestingly, E-box editing at either oriLyt decreased MYC occupancy at both oriLyt sites (Figure 6C). This result is consistent with a model in which MYC E-Box oriLyt occupancy coordinates higher-order EBV genome structures.

Effects of E-box editing on EBV latency reversal were next investigated. sgRNAs 1 and 2, which target the same oriLytR region E-box, induced BZLF1 and BMRF1 expression. By contrast, targeting of a nearby E-box by sgRNA3 did not induce lytic gene expression, suggesting that CRISPR editing of the Akata EBV genome does not non-specifically induce lytic gene expression. Similarly, targeting of only one of two oriLytL region E-box sites induced BZLF1 and BMRF1 expression, despite similar levels of EBV genome editing (Figures 6B, D). As a further control for EBV genome editing, expression of an sgRNA targeting the EBV early gene BMRF1 edited the EBV genome, prevented Ig-crosslinking-induced BMRF1 protein expression (Figure S7D), but did not induce BZLF1 expression (Figure 6D). sgRNAs 1,2 and 5 each also induced late antigen gp350 expression, suggesting that editing of a single E-box site is sufficient for lytic antigen induction (Figure 6E and S7E). oriLyt E-box sites are conserved across numerous EBV strains (Figure S7F), suggesting that MYC occupancy of these, and perhaps additional oriLyt region E-box sites, is necessary for EBV latency in BL. When both oriLyt are present, MYC occupancy at each site may be necessary for the maintenance of EBV latency.

ENCODE LCL ChIP-seq data revealed that STAGA subunits GCN5 and SUPT20H co-occupy the EBV genome at oriLyt (Arvey et al., 2013), raising the possibility that STAGA may have MYC dependent roles at oriLyt. We tested whether GCN5 occupies oriLyt regions in BL, and whether MYC was important for recruitment of GCN5 to these oriLyt regions. ChIP-qPCR identified GCN5 occupancy at both oriLyt regions by ChIP-qPCR (Figure 6F), suggesting that GCN5 is recruited to EBV genomes in latency I and III states. CRISPR MYC depletion reduced GCN5 occupancy at both oriLyt regions (Figure 6F), even though MYC KO did not reduce its mRNA abundance (Table S2).

GCN5 co-immunopurified with HA-tagged MYC from Akata BL lysates (Figure S7G), suggesting that they are present in protein-protein complexes in BL, as previously reported in epithelial cells. Given that multiple other screen hits are also well characterized MYC partners, these data raise the possibility that they may have dual roles in supporting MYC expression as well as acting with MYC in protein-protein complexes to maintain EBV latency.

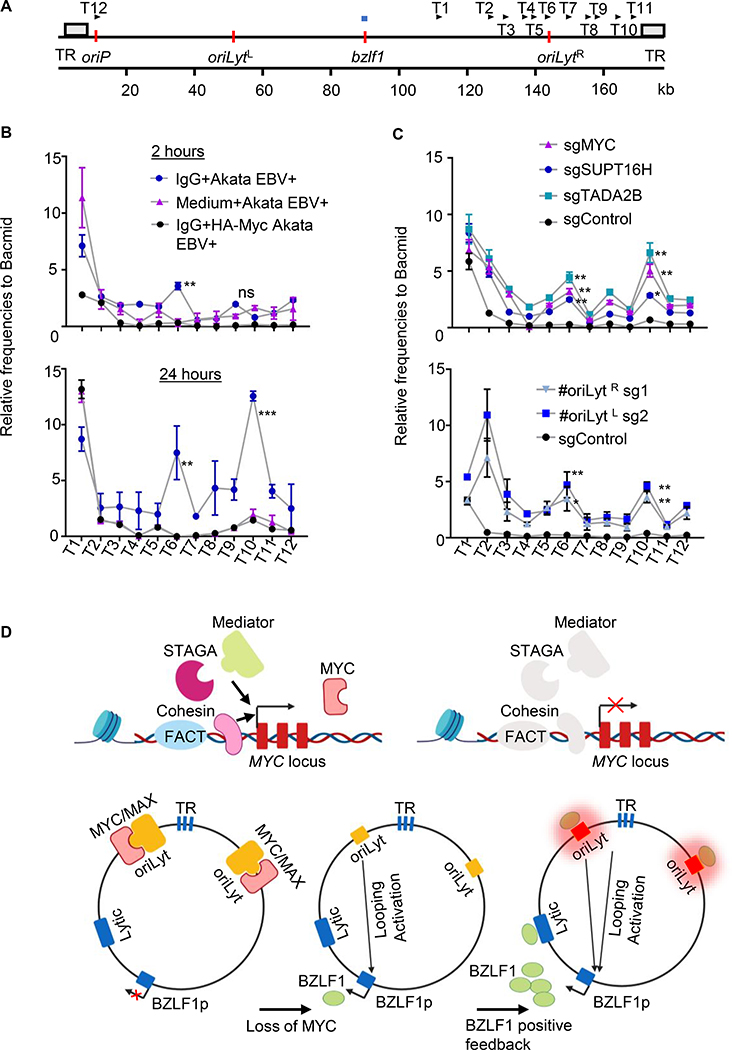

MYC Regulates EBV 3-Dimensional Genome Architecture

DNA looping has been suggested to control EBV latency program selection through the juxtaposition of the EBV genomic oriP enhancer with distinct latency gene promoters (Tempera et al., 2011). We hypothesized that in an analogous manner, MYC occupancy of oriLyt proximal E-box sites might sequester EBV genomic elements to prevent their looping to the BZLF1 immediate early gene promoter.

To test this hypothesis, we used the chromatin conformation capture (3C) assay, which quantifies interactions between binary pairs of genomic loci (Dekker et al., 2002). A 3C assay anchor primer was designed for the BZLF1 promoter and test (T) primers were designed across the oriLyt R region and nearby TR regions (Figure 7A), whose ATAC-seq signals also increased with MYC depletion. Lytic induction was stimulated in Akata cells by Ig-crosslinking. Intriguingly, by 2-hours post-activation, significant interactions between the BZLF1 promoter and the oriLyt R T6 primer were evident (Figure 7B). Stronger 3C signals were detected at T6 at 24 hours post-stimulation, at which point significant interaction between BZLF1 and the TR-region T10 primer were also detected. Notably, stable lentivirus driven MYC over-expression precluded these interactions as judged by 3C assay (Figure 7B), suggesting that MYC depletion is necessary for this EBV 3D genomic remodeling.

Figure 7. MYC Loss or B-cell Receptor Stimulation Induces OriLyt looping to BZLF1.

(A) Schematic diagram depicting chromatin conformation capture (3C) assay anchor and testing (T) primers. BZLF1 promotor region anchor primer shown by horizontal blue bar above the map. Positions of the 12 T primers are shown by arrows above the map. TR regions are depicted as grey boxes, whereas oriP, BZLF1 and oriLyt regions are depicted by vertical orange bars. Kilobase (kb).

(B) 3C assay quantitation of interaction frequency between the BZLF1 anchor primer and test primer regions in Akata with control (blue) or HA-MYC (black), following anti-IgG crosslinking for 2 or 24 hours. Values from mock-induced Akata (pink) are shown. Mean + SD values from n=3. 3C assay frequencies were normalized by Bacmid input values. ** p<0.01, *** p<0.001.

(C) 3C assay of interaction frequency between BZLF1 anchor primer and test primer regions in Akata with the indicated control (black), MYC (pink), SUPT16H (blue) or TADA2B (turquoise) sgRNAs (top graph), or in Akata expressing oriLyt region E-box targeting sgRNAs (bottom graph). Mean + SEM values from n=3 replicates 3C assay frequencies were normalized by Bacmid input values. *, p<0.05; ** p<0.01.

(D) Model of MYC as a key repressor of EBV lytic reactivation. FACT, Cohesin, STAGA and Mediator are important for MYC expression. MYC/MAX heterodimers bind to oriLyt regions and maintain EBV latency by preventing oriLyt association with the BZLF1 promoter. MYC depletion causes DNA looping, which juxtaposes oriLyt and TR regions with the BZLF1 promoter. Newly induced BZLF1 binds to oriLyt, converting it into a strong enhancer, which then drives high level BZLF1 expression and triggers early lytic gene expression.

Finally, CRISPR was used to determine the effects of screen hit or E-box editing on EBV genome looping. MYC, SUPT16H or TADA2B sgRNAs each induced significant interaction between the BZLF1 anchor site, the T6 oriLyt R region and the T10 probe just proximal to TR (Figure 7C). Similarly, sgRNAs targeting the E-box sites in either the oriLyt L or R regions induced significant interactions between the BZLF1 and these EBV genomic regions (Figure 7C). EBV lytic cycle inducers 12–0-tetradecanoylphorbol-13-acetate (TPA) or pomalidomide also induced interaction between the BZLF1 anchor site, oriLyt and TR regions (Figure S7H). Collectively, these results are consistent with a model in which the EBV genome responds to loss of MYC by looping oriLyt and TR genomic elements to the BZLF1 promoter in order to initiate the EBV lytic cycle (Figure 7D). Such a mechanism could enable EBV to sense MYC levels and respond to plasma cell differentiation, where Blimp1 suppresses MYC.

DISCUSSION

Plasma cell differentiation triggers EBV lytic reactivation (Crawford and Ando, 1986; Laichalk and Thorley-Lawson, 2005), yet knowledge remains incomplete of how EBV senses and responds to changes in B-cell development. Our results suggest MYC abundance is a key signal that relays information about B-cell state directly to the viral genome, where it controls the decision of whether to undergo lytic reactivation through changes to EBV genome three-dimensional architecture.

EBV induces MYC to remarkably high RNA and protein levels within the first 48 hours of infection (Wang et al., 2019). Such high MYC expression may serve not only to trigger B-cell growth transformation, but may also deliver a crucial signal to the newly circularized and chromatinized EBV genome to program the establishment of viral latency. A MYC-based silencing mechanism could function synergistically with the established role of DNA hypomethylation in limiting EBV early lytic gene induction by leaky BZLF1 expression (Bergbauer et al., 2010; Bhende et al., 2004). It could also play an important independent role in suppression of lytic reactivation upon germinal center B-cell differentiation, where progressive EBV genome methylation sets the stage for BZLF1-mediated early gene activation. Interestingly, markedly elevated MYC levels also limit latent membrane oncoprotein expression early after B-cell infection (Price et al., 2018), where MYC:MAX heterodimers repress the LMP1 promoter by incompletely characterized mechanisms.

The germinal center model of persistent EBV infection (Thorley-Lawson, 2015) postulates that EBV-infected cells closely follow the trajectory of uninfected B lymphocytes as they undergo development into memory B-cells. MYC is important for the establishment and maintenance of germinal centers (Calado et al., 2012), where antigen and T-follicular helper cell co-stimulation support MYC expression in germinal center centrocytes (Victora and Nussenzweig, 2012). Importantly, MYC is highly expressed in memory B-cells (Klein et al., 2003). Yet, MYC levels are lower in centroblasts (Finkin et al., 2019; Klein et al., 2003), raising the question of whether EBV increases MYC abundance during dark zone transit, whether EBV-infected cells do not enter the dark zone, or whether lower MYC levels are sufficient to maintain centroblast latency.

We hypothesize that Myc and BZLF1 have evolved to negatively cross-regulate one-another to enforce opposing EBV-infected B-cell states. MYC induces proliferation, whereas BZLF1 causes cell cycle arrest. MYC inhibits BZLF1-mediated transcription activation in nasopharyngeal carcinoma cells (Lin et al., 2004; Rodriguez et al., 2001) and likely also in B-cells, since MYC over-expression blocks leaky lytic gene expression in LCLs (Fais et al., 1996) and as shown here also in BL. How rare BL cells undergo spontaneous lytic reactivation in the context of a translocated MYC allele is unknown, but cell cycle state and interferon can lower MYC expression at the post-transcriptional level (Einat et al., 1985; Knight et al., 1985).

Our data support a model in which cohesins, FACT, STAGA and Mediator are necessary to maintain MYC expression above a threshold required to suppress EBV lytic reactivation. We speculate that MYC itself is the sequence-specific transcription factor that nucleates a complex containing these hits to stimulate its own re-synthesis in BL. A similar mechanism could enable MYC feed-forward regulation in EBV-transformed lymphoblastoid cells, where EBNA- and NF-κB bound enhancers loop to the MYC promoter (Jiang et al., 2017; Wood et al., 2016). We also speculate that EBV-infected B-cells may therefore first encounter low MYC levels upon plasma cell terminal differentiation, where the master regulator BLIMP1 represses MYC transcription (Lin et al., 2000). BLIMP1 over-expression induces EBV lytic induction (Reusch et al., 2015) -- while additional Blimp1 roles at the BZLF1 promoter have been reported, repression of MYC may be a key mechanism by which it drives the EBV lytic cycle in B-cells.

oriLyt serves as a key cis-acting enhancer of late lytic gene expression (Djavadian et al., 2016; Hammerschmidt and Sugden, 2013), but to our knowledge has not previously been implicated in immediate early gene regulation or to act in trans. We speculate that basal oriLyt enhancer activity can initiate BZLF1 induction. Even low level BZLF1 upregulation could then bind to and further strengthen oriLyt enhancer activity, driving a feedforward loop in which BZLF1-occupied oriLyt highly induces BZLF1. The EBV terminal repeat regions are also brought into proximity of the BZLF1 promoter by MYC depletion and may also participate in BZLF1 induction. An objective of future studies will be to delineate how these EBV genomic control elements form apparently stable loops with BZLF1 in the absence of MYC.

The EBV genome contains two lytic origins elements, located 100 kb apart, present in nearly all EBV strains, with the exception of B95–8. Yet, CRISPR perturbation of E-box sites at either lytic origin was sufficient to trigger lytic replication, raising the question of whether oriLyt R and L may act redundantly in lytic reactivation. When E-box sites were targeted at either oriLyt, MYC occupancy at both lytic origins, likely because global MYC levels diminish upon lytic induction. Cohesins play roles in long-range DNA interactions and repress KSHV lytic induction (Chen et al., 2012; Li et al., 2014). Further studies are required to determine whether SMC1A may function together with MYC to fold the EBV genome into a pro-latency configuration.

MYC siRNA knockdown induces KSHV lytic antigen expression in primary effusion lymphoma (PEL), a tumor that is usually EBV co-infected (Li et al., 2010), though effects on lytic DNA replication and late gene expression have not yet been characterized. The mechanism may be distinct from EBV, because p38 and JNK kinase signaling was found to be necessary, whereas MAP kinase pathway components did not score in our CRISPR screen.

MYC scored in our Day 6, but not Day 9 CRISPR screen, likely because BL cells only survive for several days after MYC depletion, whereas live cells were collected. Yet, nearly all essential genes, including those previously defined in BL (Jiang et al., 2019; Wang et al., 2015), did not score, suggesting that effects of MYC depletion on lytic induction were specific, and not secondary to effects on viability. sgRNAs less efficiently depleted MYC in P3HR-1 (Figure S2B) than in other BL, perhaps due to tumor-specific MYC mutations. We speculate that P3HR-1 mutation comprised sgRNA editing of MYC exon 2, since BL MYC is often targeted by somatic mutation to stabilize MYC (Rabbitts et al., 1984). It will be of interest to test MYC KO effects in EBV-infected memory cells with latency I expression when models become available.

Our screen was not designed to identify host factors that positively regulate the BZLF1 promoter, such as transforming growth factor (TGF)-β (Iempridee et al., 2011) or HIF-1α (Kraus et al., 2017). Notably, TGF-β represses MYC expression (Warner et al., 1999) and HIF-1α, which binds to a BZLF1 promoter hypoxia-response element (Kraus et al., 2017), can destabilize or displace DNA-bound MYC complexes (Gordan et al., 2007). Alternatively, STAT3, KRAB-zinc finger proteins and IRF8 repress EBV lytic reactivation(Li and Bhaduri-McIntosh, 2016; Li et al., 2018; Lv et al., 2018), but their KO may not have induced sufficient gp350 in the P3HR-1 context to be screen hits. Knockdown of the B-cell transcription factors IKZF1, PAX5 or OCT-2 induces EBV reactivation (Iempridee et al., 2014; Raver et al., 2013; Robinson et al., 2012), but may have been false negatives due to more significant adverse effects of their KO on BL fitness. False negatives may also result from redundancy, such as ZEB1/2 or tousled like kinases, where homologues can each repress BZLF1 (Dillon et al., 2013; Ellis et al., 2010). Since ZEB1/2 also bind to E-box sites, it will be of interest to determine whether they may act together with MYC to repress EBV lytic genes.

MYC/MAX heterodimers transcriptionally activate host target genes in cells with elevated MYC levels, including p493–6 (Lin et al., 2012). Many additional screen hits are MYC interactors that also typically function in transcription activation. While MYC and other screen hits may control EBV genomic looping through effects on viral or host non-coding RNA, it also remains plausible that EBV has evolved a mechanism to paradoxically use MYC:MAX as a repressor. In support of the latter possibility, EBV reverses the role of DNA methylation and aberrantly uses it as an activator of early lytic gene expression (Bergbauer et al., 2010; Bhende et al., 2004).

Current chemotherapy treatments to EBV+ Burkitt lymphoma do not take advantage of the presence of viral genomes in tumor cells. There is keen interest in lytic induction approaches to sensitize BL, and other EBV-infected tumors to cytotoxic activity of the antiviral drug ganciclovir or to CD8-T-cell immuno-oncology therapies. The work presented here raises the possibility that disruption of MYC expression, including by CBL0137, may be harnessed in novel therapeutic approaches to EBV-infected B-cell malignancies.

STAR METHODS

RESOURCE AVAILABLITIY

Lead Contact

Further information and requests for resources and reagents should be directed to and will be fulfilled by the Lead Contact, Benjamin Gewurz (bgewurz@bwh.harvard.edu).

Materials Availability

All plasmids and cell lines generated in this study will be made available on request.

EXPERIMENTAL MODEL AND SUBJECT DETAILS

Cell lines and reagents

Throughout the manuscript, all B-cell lines used with the exception of p493–6 were Cas9+. The EBV+ Burkitt lymphoma cell lines P3HR-1, Akata, MUTU I, Daudi and CLIX-FZ were used in the study, as were GM12878, GM12881 and GM11830 LCLs. CLIX-FZ are HH514–16 BL cells that stably carry the pLIX_402-FZ system for conditional HA-epitope tagged BZLF1 expression. EBV-Akata cells are a derivative cell line of the original EBV+ Akata tumor cell line that was cured of EBV infection. P3HR1-ZHT cells stably express a conditional BZLF1 allele (BZLF1-HT), in which the ligand binding domain of a modified estrogen receptor responsive to 4HT is fused to the BZLF1 C-terminus. In the absence of 4HT, BZLF1-HT is retained in the cytosol and is destabilized. 4HT addition stabilizes BZLF1-HT and drives its rapid nuclear translocation. NUGC3 is an EBV+ gastric carcinoma cell line. NPC43 is an EBV+ nasopharyngeal carcinoma cell line. Cell lines with stable expression of Streptococcus pyogenes Cas9 gene were generated by lentiviral transduction, followed by blasticidin selection as reported (Greenfeld et al., 2015). See below for the P493–6 B-cell system. All cells used in this study were cultured in a humidified incubator at 37°C with 5% CO2 and routinely tested and certified as mycoplasma-free using the MycoAlert kit (Lonza). B cells, NPC43 and NUGC3 were grown in RPMI 1640 medium (GIBCO, Life Technologies) with 10% fetal bovine serum (FBS, Gibco). NPC43 were also cultured with 4μM of Y-27632 (Sigma-Aldrich). 293T were grown in Dulbecco’s Modified Eagle’s Medium (DMEM) with 10% FBS. For selection of transduced cells, puromycin was added at the concentration of 3 μg/ml. Hygromycin was used at 200 μg/ml for the initial 4 days, and 100 ug/ml thereafter. Blasticidin was used at the concentration of 5 ug/ml. CBL0137 was used at the concentrations of 2μM or 5μM in vitro. Acyclovir was used at the concentration of 100 μg/ml in vitro.

METHOD DETAILS

MYC inducible system in P493–6 cells

The P493–6 cell line was a gift from Micah Luftig lab (Duke University). They are LCLs that contain both a conditional EBNA2-HT allele and an exogenous Tet-OFF MYC allele. P493–6 cells were maintained continuously in a Burkitt-lymphoma-like state with high exogenous MYC expression by culturing cells in the absence of doxycycline and in the absence of 4HT. To shift P493–6 cells to a low MYC state, cells were cultured in media with 1 μg/mL doxycycline in the absence of 4HT. After 48h of growth in the conditions described, total RNA was harvested using PureLink RNA Mini Kit (Invitrogen). For RT-PCR, cDNA was generated using iScript Reverse Transcription Supermix kit (Bio-Rad). Quantitiave real-time PR-PCR was then performed using SYBR Green (Applied Biosystems) on an CFX96 Touch™ Real-Time PCR Detection System (Bio-Rad). The data were normalized to internal control 18S rRNA. Relative expression was calculated using 2−ΔΔCt method. All samples were run in technical triplicates and at least two independent experiments were performed.

CRISPR Screen

130 million Cas9+ P3HR-1 cells were spinoculated in the presence of 4 μg/ml polybrene at 300 g for 2 hours with the Brunello library at a multiplicity of infection (MOI) of 0.3 to limit the co-transduction. Tissue culture plates were then returned to the incubator for additional 6 hours, followed by changing media with fresh cell culture medium. Transduced cells were selected with 3 μg/ml of puromycin at 48 hours post transduction. Transduced cells were then passed every 72 hours, maintaining at least 40 million per library after each passage to keep adequate complexity. At day 6 post-puromycin selection, input genomic DNA was extracted from 40 million cells per each screen replicate by the Qiagen Blood and Cell Culture DNA Maxi Kit. About 160 million cells were stained by anti-gp350-Cy5 antibody 72A1 at day 6 and day 9 and FACS sorting was subsequently performed at Human Immunology Center Flow Core, Brigham and Women’s Hospital, Boston, MA. Genomic DNA of sorted cells was extracted with Qiagen Blood and Cell Culture DNA Mini Kit and sent together with the input DNA for PCR amplification and next-generation sequencing. The STARS algorithm was used to identify statistically-significant screen hits(Doench et al., 2016). For all hits, at least two independent sgRNAs scored independently.

Individual sgRNA CRISPR knockout analysis

For hit validation, individual sgRNA directed CRISPR/Cas9 knockout was performed as previously described (Greenfeld et al., 2015). In brief, Cas9+ B cells were transduced with lentiviruses expressing sgRNAs of interest. Transduced cells were then selected and expanded in the presence of appropriate selection regent (puromycin or hygromycin). For double knockout analysis, KAT2B sgRNA was cloned into pLentiGuide-puro (Addgene plasmid #52963) while the KAT2A sgRNA was cloned into pLenti-spBsmBI-sgRNA-Hygro (Addgene plasmid #62205) vector. P3HR-1 Cas9 cells were initially transduced with lentivirus expressing KAT2A sgRNA and selected with hygromycin for 2 weeks. KAT2A transduced cells were subsequently transduced with lentiviruses expressing KAT2B sgRNA, followed by puromycin selection. On-target CRISPR effects were validated by immunoblot.

cDNA Rescue

The MYC cDNA entry vector was purchased from DNASU and was sub-cloned into pLX-TRC313 (a gift from John Doench) by Gateway recombination. Cas9 expressing B cells with stable C-terminal HA epitope-tagged MYC cDNA expression were established by lentiviral transduction and hygromycin selection. MYC cDNA expression was confirmed by immunoblot and by FACS. MYC rescue cDNA, with silent PAM site mutations at MYC sg1 and sg2 sites, is described in the following table. MYC sg1 and sg2 targeting sequences are highlighted. PAM sequences are underlined. Mutation sites are indicated in red. Rescue cDNA was synthesized by GenScript (Piscataway, NJ) and cloned into pLX-TRC313 vector.

| Myc KO and Rescue | |

| sgRNA | 5’ – CTCGGTGGTCTTCCCCTACC – 3’ (#1, antisense) 5’ – GTATTTCTACTGCGACGAGG – 3’ (#2) |

| Genomic DNA | 5’ – GAC

CCC TCG GTG GTC TTC CCC TAC CC– 3’(#1) 5’ – G TAT TTC TAC TGC GAC GAG GAG GA– 3’ (#2) |

| Rescue cDNA | 5’ – GAT

CCC TCG GTG GTC TTC CCC TAC CC– 3’(#1) 5’ – G TAT TTC TAC TGC GAC GAG GAA GA– 3’ (#2) |

| Rescue cDNA sequence surrounding the PAM site mutation (in red, sgRNA sequence in yellow) | CTGGATTTTTTTCGGGTAGTGGAAAACCAGCAGCCTCCCG CGACGATGCCCCTCAACGTTAGCTTCACCAACAGGAACTA TGACCTCGACTACGACTCGGTGCAGCCGTATTTCTACTGC GACGAGGAAGAGAACTTCTACCAGCAGCAGCAGCAGAGC GAGCTGCAGCCCCCGGCGCCCAGCGAGGATATCTGGAAG AAATTCGAGCTGCTGCCCACCCCGCCCCTGTCCCCTAGCC GCCGCTCCGGGCTCTGCTCGCCCTCCTACGTTGCGGTCAC ACCCTTCTCCCTTCGGGGAGACAACGACGGCGGTGGCGG GAGCTTCTCCACGGCCGACCAGCTGGAGATGGTGACCGA GCTGCT GGGAGGAGACATGGTGAACCAGAGTTTCATCTGC GACCCGGACGACGAGACCTTCATCAAAAACATCATCATCC AGGACTGTATGTGGAGCGGCTTCTCGGCCGCCGCCAAGCT CGTCTCAGAGAAGCTGGCCTCCTACCAGGCTGCGCGCAAA GACAGCGGCAGCCCGAACCCCGCCCGCGGCCACAGCGTC TGCTCCACCTCCAGCTTGTACCTGCAGGATCTGAGCGCCG CCGCCTCAGAGTGCATCGATCCCTCGGTGGTCTTCCCCTA CCCTCTCAACGACAGCAGCTCGCCCAAGTCCTG |

The TADA1 cDNA entry vector construct was purchased from DNASU and was sub-cloned into pLX-TRC313 vector by Gateway recombination. Cas9 expressing B cells with stable C-terminal epitope tagged V5-TADA1 expression were established by lentiviral transduction and hygromycin selection. TADA1 cDNA expression was confirmed by immunoblot. The design of rescue cDNA for TADA1 is described in the following table. TADA1 sgRNA targeting sequence is highlighted. The PAM sequence is underlined. PAM site mutation is indicated in red. TADA1 rescue cDNA was synthesized by GenScript (Piscataway, NJ) and was cloned into pLX-TRC313 vector.

| TADA1 KO and Rescue | |

| sgRNA | 5’ – GCCAAGAAGAACTTAAGCG – 3’ |

| Genomic DNA | 5’ – GCC AAG AAG AAC TTA AGC GAG GC– 3’ |

| Rescue cDNA | 5’ – GCC AAG AAG AAC TTA AGC GAA GC – 3’ |

| Rescue cDNA sequence surrounding the PAM site mutation (in red, sgRNA sequence in yellow) | ATGGCGACCTTTGTGAGCGAGCTGGAGGCGGCCAAGAAG AACTTAAGCGAAGCCCTGGGGGACAACGTGAAACAATAC TGGGCTAACCTAAAGCTGTGGTTCAAGCAGAAGATCAGC AAAGAGGAGTTTGACCTTGAAGCTCATAGACTTCTCA |

Western blot analysis

Weston blot analysis was performed as previously described (Ma et al., 2017). In brief, whole cell lysates were separated by SDS-PAGE electrophoresis, transferred onto the nitrocellulose membranes, blocked with 5% milk in TBST buffer and then probed with relevant primary antibodies at 4 °C overnight, followed by secondary antibody (Cell Signaling) incubation for 1 h at room temperature. Blots were then developed by incubation with ECL chemiluminescence for 1 min and images were captured by Licor Fc platform. All antibodies used in this study were listed in the Key Resource Table.

Flow cytometry analysis

For live cells staining, 1× 106 of cells were washed twice with FACS buffer (PBS, 1mM EDTA, and 0.5% BSA), followed by primary antibodies incubation for 30 min on ice. Labeled cells were washed three more times with FACS buffer. For intracellular staining, cells were treated with Fixation/Permeabilization Solution Kit (BD bioscience) following the manufacturer’s protocol. Cells were sorted on a BD FACSCalibur and analyzed with FlowJo X software (FlowJo).

Quantification of EBV genome copy number

To measure EBV genome copy number, intracellular viral DNA and virion-associated DNA present in cell culture supernatant were quantitated by qPCR analysis. For intracellular viral DNA extraction, total DNA from 2×106 of BL cells was extracted by the Blood & Cell culture DNA mini kit (Qiagen). For extracellular viral DNA extraction, 500 μl of culture supernatant was collected from the same experiment as intracellular DNA measurement, and was treated with 20 μl RQ1 DNase (Promega) for 1 h at 37°C to degrade non-encapsidated EBV genomes. 30 μl proteinase K (20 μg/ml, Invitrogen) and 100 μl 10% (wt/vol) SDS were then were added to the reaction mixtures, which were incubated for 1 h at 65°C. DNA was purified by phenol-chloroform extraction followed by isopropanol-sodium acetate precipitation and then resuspended in 50 μl nuclease-free water. Extracted DNA was further diluted to 10 ng/ul and subjected for qPCR targeting the BALF5 gene. Standard curves were made by serial dilution of a pHAGE-BALF5 miniprep DNA at 25 ng/uL. Viral DNA copy number was calculated by inputting sample Cq values into the regression equation dictated by the standard curve.

Mouse xenograft experiments

Mouse xenograft experiments were regulated by Institutional Animal Care & Use Committee (IACUC# 2017–0035) of Weill Cornell Medical Center(WCMC). NOD scid gamma humanized mice were obtained from Jackson Laboratories. Six to eight-week-old male and female mice (10 male/18 female) were injected in the flank with 1 × 107 BL cells in PBS with Matrigel eleven days before the treatment. Once the mice developed tumors with the size greater than 300 mm^3, they were grouped randomly and injected with vehicle (5% dextrose), 10 mg/kg, or 60 mg/kg of CBL0137. One week later, mice were injected with second dose of vehicle or CBL0137. Mice were humanely sacrificed at set experimental timepoints or when tumors reached the institutional cutoff. Tumors were harvested and snap frozen in liquid nitrogen for RNA, DNA, and sectioning for immunohistochemistry.

Quantitative real time (qRT)-PCR

Total RNA was harvested from cells or xenograft tumors using the RNeasy Mini Kit (Qiagen). Genomic DNA was removed by using the RNase-Free DNase Set (Qiagen). qRT-PCR was performed using Power SYBR Green RNA-to-CT 1-Step Kit (Applied Biosystems) on an CFX96 Touch™ Real-Time PCR Detection System (Bio-Rad), and data were normalized to internal control 18S rRNA. Relative expression was calculated using 2−ΔΔCt method. All samples were run in technical triplicates and at least three independent experiments were performed. The primer sequences were listed in the Key Resource Table.

Immunohistochemistry

Tumor samples were fixed in 10% neutral buffered formalin (Sigma-Aldrich) at room temperature. After trimming, tissues in the cassettes were processed using a Tissue-Tek VIP automatic tissue processor (Sakura, Finland) with the routine overnight run and embedded into paraffin wax (Tissue-Tek). Embedded blocks were placed on the ice for a short time, and cut into 4 μm sections, which were further picked up onto Superfrost plus microscope slides (Fisherbrand). Slides were positioned at a vertical rack for air dry overnight, placed in the warmer at 55°C for 25 min, and dewaxed for 15 min. Next, the slides were steamed in the citrate buffer for 30 min for antigen retrieval, cooled down on the bench for 20min and cleaned in the water holder for 5min. The tissues were further edged by the ImmEdge pen (Vector Laboratories, Burlingame, CA), blocked with the protein block (Dako, Carpinteria, CA) for 10min at 37°C, incubated with 1:200 diluted primary antibodies at 37°C for 1h, and HRP-conjugated goat-anti-mouse pAb (Jackson ImmunoResearch) as the secondary antibody at 37°C for 1h. The tissue samples were further H&E stained.

RNA sequencing (RNAseq) experiments

Prior to RNA harvest, live cells were purified using the Dead Cell Removal Kit (Miltenyi Biotec) following the manufacturer’s protocol. Total RNAs were isolated using RNeasy mini kit following the manufacturer’s manual. An in-column DNA digestion step was included to remove any residual genomic DNA contamination. To construct indexed libraries, 1 μg of total RNA was used for polyA mRNA-selection using NEBNext Poly(A) mRNA Magnetic Isolation Module (New England Biolabs), followed by library construction via NEBNext Ultra RNA Library Prep Kit for Illumina (New England Biolabs). Each experimental treatment was performed in biological triplicate. Libraries were multi-indexed, pooled and sequenced on an Illumina NextSeq 500 sequencer using pair-end 75 bp reads (Illumina).

ATAC-seq experiments

ATAC-seq analysis was performed as previously described (Buenrostro et al., 2015). Briefly, purified nuclei from 50,000 EBV+ Akata cells were resuspended in Tn5 enzyme reaction buffer from the Nextra kit (Illumina, cat. No. FC-121–1030) for 30 min at 37 °C while shaking at 600 rpm. DNA was then purified by a MinElute PCR purification kit (Qiagen). Libraries were amplified for 10 cycles by PCR and purified using Agencourt AMPure XP beads (Cat. No. 63881). DNA was analyzed on a BioAnalyzer at the Harvard Biopolymers core facility. Libraries were sequenced on an Illumina HiSeq 2500 sequencer, and 75 bp were sequenced using a pair-end protocol.

Chromatin immunoprecipitation (ChIP) and ChIP-seq

Twenty million EBV+ Burkitt cells were fixed with 1% formaldehyde for each ChIP assay. Cell were lysed in lysis buffer (50 mM HEPES-KOH, 150 mM NaCl, 1 mM EDTA, 1% Triton X-100, 0.1% sodium deoxycholate, and 1% SDS). Chromatin was resuspended using FA lysis buffer (50 mM HEPES-KOH, 150 mM NaCl, 1 mM EDTA, 1% Triton X-100, 0.1% sodium deoxycholate, and 0.1% SDS) and fragmented by an ultra-sonication processor (Diagenode, USA). Soluble chromatin was diluted and incubated with 5-μg specific primary antibody (Abcam). Immunocomplexes were precipitated by protein A or G beads. Beads were extensively washed. After reverse cross-linking by protease K treatment (40 U/ml), DNA was purified by QIAquick PCR purification kit (Qiagen). ChIP assay DNA was qPCR quantified and normalized to the percent of input DNA. For MYC ChIP-seq, chromatin immunoprecipitations were performed with cross-linked chromatin from 4 × 10^6 Daudi cells and 10 ul c-Myc/N-Myc (D3N8F) Rabbit mAb #13987 (Cell Signaling Technology), using SimpleChIP® Plus Enzymatic Chromatin IP Kit (Magnetic Beads) #9005 (Cell Signaling Technology). DNA Libraries were prepared using SimpleChIP® ChIP-seq DNA Library Prep Kit for Illumina® #56795 (Cell Signaling Technology). Single-read libraries were sequenced on an Illumina NextSeq 500 sequencer.

Chromosome conformation capture (3C)

3C-qPCR assay was performed as previously described (Hagège et al., 2007; Tempera et al., 2011). Ten million Burkitt cells were suspended in 10 ml of media containing 10% FBS and were cross-linked with 2% formaldehyde for 10 minutes at room temperature. The reaction was quenched with 0.125M glycine and cells were centrifuged for 5 minutes at 1200 rpm at 4°C. The pellet was washed once with ice cold PBS and the cell pellet was lysed with 5ml of ice-cold lysis buffer (10mM Tris-HCl pH:8.0, 10mM NaCl, 0.2% NP-40, protease inhibitor cocktail). Nuclei were pelleted and resuspended in 0.5ml 1.2x Csp6I Fastdigest restriction buffer (Thermofisher). SDS was added in 0.3% final concentration and nuclei were incubated for 1 hour at 37°C with shaking at 900 rpm. 2% final concentration of Triton X-100 was added to the nuclei, followed by 1 hour incubation at 37°C while shaking at 900 rpm. 400 U Csp6I (Thermofisher) was added to the nuclei and the samples were incubated at 37°C overnight while shaking at 900 rpm. 10 μl of the samples were collected before and after the Csp6I reaction to evaluate digestion efficiency. The reaction was stopped by addition of 1.6% SDS (final concentration) and incubated at 65°C for 30 minutes while shaking at 900 rpm. Samples were then diluted 10-fold with 1.15X T4 DNA ligase reaction buffer (B0202S, New England Biolabs), and 1% final concentration of Triton X-100 and added. Samples were then incubated for 1 hour at 37°C while shaking at 900 rpm. 100 U T4 DNA ligase (M0202S, New England Biolabs) were then added to the sample and the reaction was carried at 16°C for 4 hours, followed by incubation for 30 min at room temperature. 300 μg of Proteinase K (P8107S, New England Biolabs) was added to the sample and the reaction was carried at 65°C overnight. RNA was digested by adding 300 μg of RNAse A(EN0531, Thermo-Fisher) and incubating the sample for 1 h at 37°C. EBV Wt bacmid was used as the ligation control, 10 μg of which was digested with 20 U of Csp6I overnight and then incubated with 20 U T4 DNA-ligase at 16°C overnight. DNA was phenol-chloroform extracted and ethanol precipitated. Purified DNA was then analyzed by quantitative PCR. The ΔCt method was used to analyze qPCR data. Ct values were normalized for each primer pair by setting the Ct value of 25 ng of EBV bacmid control random ligation matrix DNA at a value of 1. Primer sequences and EBV genome coordinates are listed in Table S7.

T7 endonuclease I (T7E1) assay

T7E1 assay was performed by EnGen Mutation Detection Kit ( #E3321, New England Biolabs) following the manufacturer’s protocol. Briefly, Cas9-targeted regions were PCR amplified from genomic DNA harvested from cells expressing sgControl or specific sgRNAs. PCR products were purified by 2% agarose gel electrophoresis and then by QIAquick® Gel Extraction Kit (Qiagen). A mixture containing PCR products amplified from control cells (500 ng) or from control cells and EBV genome sgRNA targeted cells (250ng) were supplemented with 1 μl NEB2 buffer, heated to 95°C for 10 minutes and then cooled down to 4°C at a cooling rate of 0.1°C/ seconds, using a Thermocyler. Subsequently, 0.5 μl of the T7E1 enzyme (250 U/ml of final concentration, New England Biolabs) was added. The restriction enzyme digest was incubated at 37°C for 30 minutes and subsequently separated on a 2% agarose gel.

Sanger Sequencing

The region flanking the near oriLyt E-box sites were PCR amplified from the Akata EBV positive cells expressing control or oriLyt sgRNAs. The PCR products were gel purified using the QIAquick Gel Extraction Kit (Qiagen) and then cloned into pCR 4-Blunt-TOPO vector with the Zero Blunt™ TOPO™ PCR Cloning Kit (Thermo Fisher). Three individual clonies were picked for DNA sequencing.

Bioinformatic analysis

All raw sequencing reads were first evaluated using FastQC (http://www.bioinformatics.babraham.ac.uk) and confirmed with no significant quality issues.

RNA-seq data analysis: Paired-end reads were mapped to human (GENCODE v28) and EBV (Akata) transcriptome and quantified using Salmon v0.8.2 (Patro et al., 2017) under quasi-mapping and GC bias correction mode. Read count table of human and EBV genes was then normalized across compared cell lines/conditions and differentially expressed genes were evaluated using DESeq2 v1.18.1 (Love et al., 2014) under default settings.

ChIP-seq data analysis: Myc ChIP-seq data of P493 cells was downloaded from GEO (GSE36354). All ChIP-seq data was mapped to human (hg19) and EBV (Akata) genomes using Bowtie2 v2.2.3 (Langmead and Salzberg, 2012). Peaks was called on EBV genome using MACS2 v2.1.0 (Zhang et al., 2008) with no model fitted. MACS2 reported p-value was used to define significant enriched peaks (p<0.05), while other regions were treated as background. ChIP-seq coverage of EBV genome was then normalized by total number of reads in the background. ATAC-seq of EBV genome was analyzed the same as ChIP-seq except that paired-end reads (fragments) were used to call peaks and reads on positive/negative strands were shifted +4/−5 bp separately to account for the Tn5-induced bias(Buenrostro et al., 2013).

DNA sequence alignment: The nucleoacid sequences of E-box sites near OriLytL and OriLytR from Akata (KC207813.1); Daudi (V01555.2); MUTU(KC207814.1); C666(KC617875.1); Raji (KF717093.1); Jijoye (LN827800.1) were aligned with T-COFFEE Multiple Sequence Alignment Server (Di Tommaso et al., 2011).

Protein-protein association networks(STRING v11.0): A merged list of day6 and day9 scored hits was subjected to the STRING v11.0 (https://string-db.org/) web site (Szklarczyk et al., 2019). In order to obtain the stringent protein-protein interaction network, a highest confidence level (> 0.900) was set. The disconnected nodes were hide. Edge confidence was presented by the line thickness: thin dot edge, 0.16; thick dot edge, 0.40; thick solid line, 0.90.

QUANTIFICATION AND STATISTICAL ANALYSIS

Statistical analysis

Statistical significance of CRISPR screen results was calculated using the STARSs algorithm v1.3 (Doench et al., 2016). Multiple hypothesis testing was adjusted using the Benjamini-Hochberg method with false discovery rate < 0.05, to filter significant screen hits. STARs was used to compare sgRNA abundances in the P3HR-1 B cell library prior to FACS sort with levels in the corresponding sorted populations. Thus, sgRNA abundances in the sorted population were compared to the input library levels.

Unless otherwise indicated, all bar graphs and line graphs represent the arithmetic mean of three independent experiments (n = 3), with error bars denoting standard deviations. Data were analyzed using two-tailed paired Student t test or analysis of variance (ANOVA) with the appropriate post-test using GraphPad Prism7 software. P values correlate with symbols as follows, ns = not significant, p > 0.05; * p < 0.05; ** p < 0.01; *** p < 0.001, **** p < 0.0001.

DATA AND CODE AVAILABILITY

Data availability

All RNA-seq datasets have been deposited to the NIH GEO omnibus (GSE140653). Figures were drawn with commercially available GraphPad, Biorender, Microsoft Powerpoint and ggplot2 in R(Wickham, 2016).

Supplementary Material

Highlights.

CRISPR/Cas9 screen highlights host epigenetic suppressors of the EBV lytic cycle

EBV senses MYC abundance to maintain B-cell latency

MYC depletion alters 3-dimensional EBV genomic architecture

FACT is a druggable target for Burkitt B-cell EBV latency reversal

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

This work was supported by NIH RO1 AI137337 and CA228700, a Burroughs Wellcome Career Award in Medical Sciences and an American Cancer Society Research Scholar Award to BEG, a Starr Cancer Foundation grant (BEG and LGR), the Next Generation Fund at the Broad Institute (JGD) and RO1 AI123420 to BZ. This study was done in collaboration with Cell Signaling Technology, Inc. We thank Italo Tempera for helpful discussions and for technical assistance.

Footnotes

DECLARATION OF INTERESTS LGR is a consultant for Janssen, ADC Therapeutics. CF and FC are the employees of Cell Signaling Technologies.

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

REFERENCES

- Allen BL, and Taatjes DJ (2015). The Mediator complex: a central integrator of transcription. Nature reviews Molecular cell biology 16, 155–166. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Arvey A, Tempera I, and Lieberman PM (2013). Interpreting the Epstein-Barr Virus (EBV) epigenome using high-throughput data. Viruses 5, 1042–1054. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Babcock GJ, Hochberg D, and Thorley-Lawson DA (2000). The Expression Pattern of Epstein-Barr Virus Latent Genes In Vivo Is Dependent upon the Differentiation Stage of the Infected B Cell. Immunity 13, 497–506. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Belotserkovskaya R, Oh S, Bondarenko VA, Orphanides G, Studitsky VM, and Reinberg D (2003). FACT facilitates transcription-dependent nucleosome alteration. Science (New York, NY) 301, 1090–1093. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bergbauer M, Kalla M, Schmeinck A, Gobel C, Rothbauer U, Eck S, Benet-Pages A, Strom TM, and Hammerschmidt W (2010). CpG-methylation regulates a class of Epstein-Barr virus promoters. PLoS pathogens 6, e1001114. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bhende PM, Seaman WT, Delecluse HJ, and Kenney SC (2004). The EBV lytic switch protein, Z, preferentially binds to and activates the methylated viral genome. Nature genetics 36, 1099–1104. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Buenrostro JD, Giresi PG, Zaba LC, Chang HY, and Greenleaf WJ (2013). Transposition of native chromatin for fast and sensitive epigenomic profiling of open chromatin, DNA-binding proteins and nucleosome position. Nat Methods 10, 1213–1218. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Buenrostro JD, Wu B, Chang HY, and Greenleaf WJ (2015). ATAC-seq: A Method for Assaying Chromatin Accessibility Genome-Wide. Current protocols in molecular biology 109, 21.29.21–21.29.29. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Calado DP, Sasaki Y, Godinho SA, Pellerin A, Kochert K, Sleckman BP, de Alboran IM, Janz M, Rodig S, and Rajewsky K (2012). The cell-cycle regulator c-Myc is essential for the formation and maintenance of germinal centers. Nature immunology 13, 1092–1100. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Carter DR, Murray J, Cheung BB, Gamble L, Koach J, Tsang J, Sutton S, Kalla H, Syed S, Gifford AJ, et al. (2015). Therapeutic targeting of the MYC signal by inhibition of histone chaperone FACT in neuroblastoma. Science translational medicine 7, 312ra176. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen HS, Wikramasinghe P, Showe L, and Lieberman PM (2012). Cohesins repress Kaposi’s sarcoma-associated herpesvirus immediate early gene transcription during latency. Journal of virology 86, 9454–9464. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Crawford DH, and Ando I (1986). EB virus induction is associated with B-cell maturation. Immunology 59, 405–409. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cutrona G, Ulivi M, Fais F, Roncella S, and Ferrarini M (1995). Transfection of the c-myc oncogene into normal Epstein-Barr virus-harboring B cells results in new phenotypic and functional features resembling those of Burkitt lymphoma cells and normal centroblasts. The Journal of experimental medicine 181, 699–711. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dekker J, Rippe K, Dekker M, and Kleckner N (2002). Capturing chromosome conformation. Science (New York, NY) 295, 1306–1311. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]