Abstract

Background

Indigenous communities use wild plants to cure human ailments since ancient times; such knowledge has significant potential for formulating new drugs and administering future health care. Considering this, the present study was undertaken to assess use value, diversity, and conservation concerns of medicinal plants used in traditional herbal care system of a marginal hill community in Bageshwar district of Uttarakhand in the Central Himalayan region of India.

Methodology

Extensive surveys were made in 73 villages to gather information on the ethnomedicinal use of plant species used in the traditional herbal healing system. A total of 100 respondents were identified (30 herbal healers called Vaidyas and 70 non-healers/natives) and interviewed using semi-structured questionnaires, target interviews, and group discussion. Some important indices such as the use-value index (UV), relative frequency citation (RFC), cultural importance index (CI), and informant consensus factor (Fic) were calculated for the medicinal plants included in the present study.

Result

It was recorded that the community uses a total of 70 species with 64 genera and 35 families for curing various ailments. Family Lamiaceae recorded the maximum number of medicinal plants. Twenty-one species used most extensively in the traditional health care system. The major parts of the identified plants used for the treatment of various ailments were root/rhizome and leaf. The most common methods used for the preparation of these plants were decoction and infusion. Ocimum basilicum L., Cannabis sativa L., Citrus aurantifolia (Christm) Sw., Curcuma longa L., and Setaria italica L. had the highest rate of use report. RFC value ranged between 0.03 and 0.91 with highest values for Setaria italica, Zingiber officinale, Ocimum basilicum, and Raphanus sativus. The traditional knowledge is passed verbally to generations and needs to be preserved for the future bio-prospecting of plants that could be a potential cure to any future disease.

Conclusion

In recent years, the community has access to modern hospitals and medicinal facilities, although a considerable number still prefer medicinal plants for curing select ailments. It is suggested that these ethnomedicinal species need to be screened and evaluated further for their effectiveness for pharmacological activity. Also, significant efforts are required to conserve traditional knowledge and natural habitats of wild medicinal plants.

Keywords: Ethnomedicinal plants, Traditional knowledge, Indigenous people, Ailments, Public health, Bageshwar, Uttarakhand

Background

Medicinal plants have been utilized for the treatment of various diseases since ancient times, thus form an important element of aboriginal curative systems. The Indian Rishis first documented the use of medicinal plants in the form of Samhitas. Charak Samhita (1000–800 BC) and Shushrut Samhita (800–700 BC) by Maharshi Charak and and Maharshi Shashurut, respectively, are the baselines of the Indian Medicinal System. Maharshi Charak mentioned over 500 medicinal plants, out of which 340 plants used in the production of herbal medicine [1, 2]. AYUSH (i.e., Ayurveda, Unani, Siddha, and Homeopathy) is another traditional Indian health care system that is considered a great knowledge base in herbal medicines. Ayurveda reports over 2000 medicinal plant species, Siddha 1121 plant species, Unani 751 species, and homeopathy 422 species [3]. Nearly 70–80% population worldwide still relies on traditional medicinal systems for their primary health care because of their effectiveness, cultural preferences, and lack of modern health care alternatives [4, 5]. The global demand for herbal medicine continues to increase over the past few decades. The earlier studies stated that out of 250,000 flowering plants in the world, only less than 10% have been screened so far for their medicinal potency, and still, 90% remains unexplored [2]. In recent times, there is an increased interest regarding the use of the medicinal plants to develop new drugs and medicines for fulfilling the demand of a growing population [6–8]. Therefore, the information on plants of ethnomedicinal importance holds high potential. Uttarakhand Himalaya is a mountainous region in northern India that has a unique geography, rich biological resources, cultural heritage, and diverse climatic conditions which supports the highest number of medicinal plant species [9]. Over two-third population live in rural areas and depend on diverse natural resources to fulfill their need for food, fuel, fodder, timber, medicine, etc. Communities use a large variety of medicinal plants for treating diverse ailments [10, 11]. However, it is strongly being realized that the indigenous knowledge related to herbal medicines is continuously being eroded despite high significance to humanity. The subject needs further research such as documentation of potential medicinal species, analyzing their active constituents, clinical trials for validations, and developing new drugs and medicines [8–12]. Considering this, the present study was undertaken. We argue that sustainable management and conservation of medicinal plants can be achieved when information about their use for treating ailments and traditional herbal practices within particular areas are available. Such information is strongly desired to be preserved from being lost for the use of both the present and the future generations. For the purpose of this study, we selected marginal community and local herbal practitioners (Vaidyas) of Bageshwar district in Uttarakhand state in north India and documented ethnomedicinal plant diversity and traditional medicinal practices being used by them. Efforts were also made to scientifically validate and interpret the data using several indices such as relative frequency citation (RFC), use report (categorical and disease-based), cultural importance index (CI), and informant consensus index (Fic) so as to verify the homogeneity, importance, and the cultural similarity of the medicinal plants in communities. It is expected that the qualitative and quantitative information generated from the study will have immense utility for the conservation and sustainable utilization of medicinal plants as well as for managing the traditional health care system.

Materials and methods

Study area

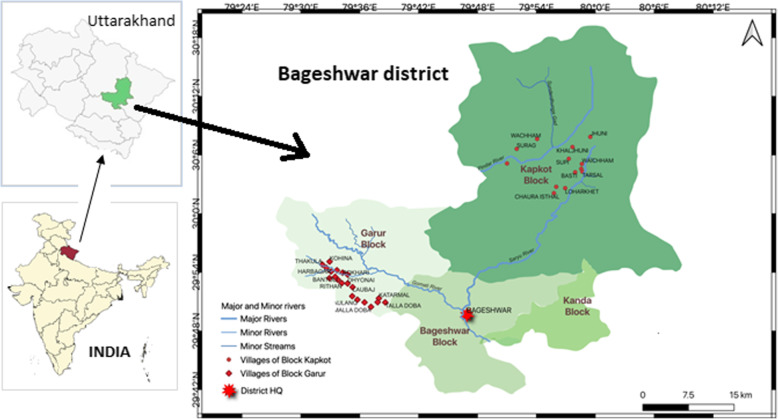

This study aimed to investigate the medicinal species used by the marginal hill community living in remote and high-altitude areas where medical health care facilities are not easily available. These practices are being used since eternity descended from the inherited knowledge of the locals and indigenous population of Uttarakhand. The study was carried out at Bageshwar district (geographical area 1687.8 km2) of Uttarakhand state and lies between latitudes 29° 42′ 40″ to 30° 18′ 56″ N and longitudes 79° 23′ to 80° 10′ E (Fig. 1). The district is situated on the confluence of Gomti river and Saryu river which is a tributary of Kali river. It is bounded by Almora district in the southwest, Chamoli district in the north and northwest, and Pithoragarh district in the east. Administratively, the district is divisible into four Tehsils, viz., Bageshwar, Kapkot, Kanda (Sub-tehsil), and Garur, and three blocks, viz., Bageshwar, Garur, and Kapkot. There are 947 revenue villages, out of which 874 villages are inhabited, and 73 villages are uninhabited. As per the 2011 census, the total population of Bageshwar district is 259,898 (male 48%, female 52%) with 96% living in the rural areas.

Fig. 1.

Study area and villages in Garur and Kapkot Bolcks of District Bageshwar, Uttarakhand, India

The community of the area is divided into 3 categories, viz., General, Scheduled Class (SC), Scheduled Tribe (ST), and majority of them involved in primary sector (agricultural activities), while some also work in secondary and tertiary sectors, such as private works, businesses, and government jobs. As such, the community is highly marginal with small and scattered land holdings, low production, and low income, therefore, highly dependent on natural resources. Male population out-migrates to earn better livelihoods that lead to continuous increase in fallow lands and culturable waste lands.

Data collection

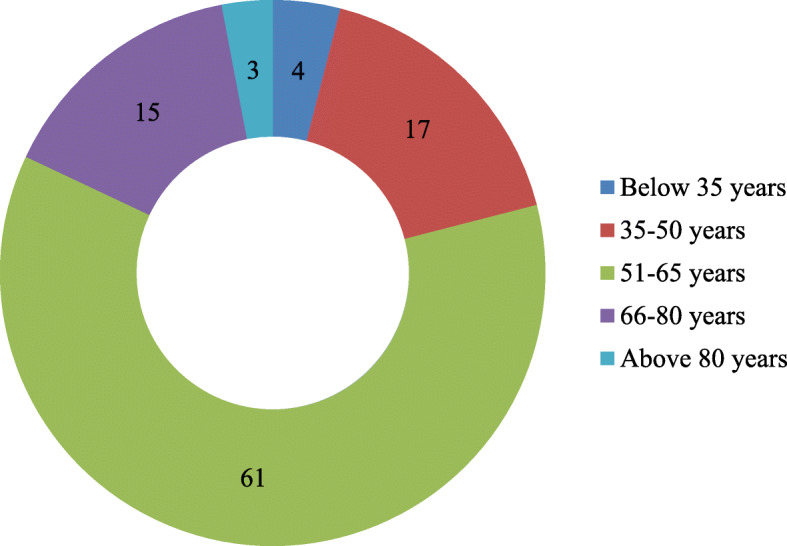

The study was conducted in 39 villages covering Garur-Ganga valley (23 villages) and Saryu valley (16 villages) of Garur and Kapkot Blocks during 2016–2018. To fulfill the objectives of the study, extensive field visits were made to gather information from traditional herbal healers (Vaidyas) and indigenous people using semi-structured questionnaires, target interviews, and visual interpretation through snowball methodology. A total of 100 respondents were randomly selected for the present study from both valleys, 37 being male and 63 female respondents. Of them, 30 were Vaidyas (male 19, female 11). Female informants were given preference in view of their dominance in villages. The age group of informants varied between 30 and 83 years, although most of them were between 50 and 65 years of age (Fig. 2). The questionnaire contains information about the ethnomedicinal plants with their local name, parts used, habit, ailment treated by medicinal plants, and mode of utilization of herbal formulation. Two general meetings and interviews were also organized at each valley with Vaidyas and natives. The documented medicinal plant species were validated for identification using available literature [13–16]. The specimens matched with the herbarium lodged in CCRAS-RARI, Tarikhet, Ranikhet, Uttarakhand (acronym RKT), which houses largest medicinal plant herbariums in northern India. A few generally available species were matched with the plant database of Centre for Socio-Economic Development deposited at G.B. Pant National Institute of Himalayan Environment (GBP-NIHE), Almora, Uttarakhand.

Fig. 2.

Age distribution of respondents

The ethnobotanical analysis

The information on ethnomedicinal important species were recorded including the local names of the species, habit, their uses in different forms, the part used in the medical practice, mode of administration, and the condition of the plant (fresh or dry). The plants were classified into 12 main categories of ailments which were further divided into different respective subcategories based on disease and affected body part. The data were then statistically analyzed for different parameters. To enhance the indicative value of the ethnomedicinal study, suitable quantitative methods and approaches were used in the form of indices, such as relative frequency of citation (RFC), use report (based on illness, based on taxa), cultural importance (CI), and consensus factor of informants (Fic).

Use-report values (UR) provides information on the total number of reported uses for each species. It is similar to the use value of a species, but for use report, the number of events (interviews), the process of asking one informant on one day about the uses they know for one species, is one because the respondents were interviewed only once. And response use values are broken down by the number of uses reported for each plant species part.

Use-value index (UV) depicts the importance of each species for each informant and calculated by UV = ∑U/N formula where U is the number of uses quoted in each interview by N, number of informants. Use values are high when there are many useful reports for a plant representing its importance and come within reach to zero (0) when the use reports are low [17].

Relative frequency citation (RFC) index reveals the usage importance of a particular species used by different informants. The index is calculated by dividing the total number of informants referring to a particular taxon with the total number of informants (RFC = FC/N) where FC is the total number of informants that referred to the taxon, and N is the total number of informants [18].

Cultural importance index (CI) is estimated for each locality as the summation of Use-Report (UR) in every use category mentioned for a species in the locality divided by the total number of informants. This index provides an implication of the involvement of a particular taxon in the community, and a greater value signifies that a particular is widely distributed among communities. A null value indicates non-existence of the species in the area. CI is calculated as CI = UR/N where UR is the total number of use reports for each species in every category of illness mentioned, and N is the total number of informants [19].

Informant consensus factor (Fic) is used to test the consistency of information knowledge in treating a particular illness category. The values obtained are near one (1) for well-defined selection criteria in the community and/or if the information is exchanged between the informants. A value approaching zero (0) represents that the plants are chosen randomly, and/or there is no information exchanged between the communities about their use. Fic is calculated as Fic = (Nur − Nt)/(Nur − 1), where Nur refers to the number of use reports for a particular use category, and Nt refers to the number of taxa used for a particular use category by all informants [20].

Result and discussion

Ethnomedicinal uses of plants and mode of practice

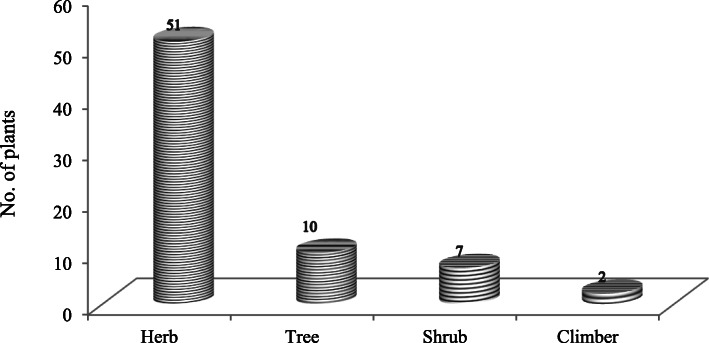

The residents of different age groups were surveyed to assess the ethnomedicinal uses of plant species (Fig. 2). The survey revealed that a total of 70 medicinal plant species varying from 35 families and 64 genera have been used by the inhabitants of 39 villages for different (Table 1). Family Lamiaceae recorded maximum species (8) followed by Asteraceae (6 species), Fabaceae (5 species), Rosaceae (4 species), and Apiaceae, Liliaceae, Ranunculaceae, Rutaceae, and Zingiberaceae (3 species each). The remaining families were represented with just one or two species. Almost all the species are widely used by the community. Of the total documented medicinal plant species, the herbaceous habit (51 species) was the most dominant life form, followed by the tree (10), shrub (7), and climbers (2 species) (Fig. 3).

Table 1.

Quantitative enumeration of ethnomedicinal plants used by marginal hill community of District Bageshwar

| Botanical name | Local name | Voucher/ident. no. | Habit | Part used | Popular ailment uses (group and categories) | Used in | Preparation | FCa | RFCb | URc | URd | CIe |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Family: Alliaceae | ||||||||||||

| Allium sativum L. | Lasan | GBPCSED1 | H | B | Skeleton and muscles—joint pain (arthritis) | Hu | O | 59 | 0.59 | 59 | 59 | 0.59 |

| Family:Apiaceae | ||||||||||||

| Angelica glauca Edgew. | Gandaraini | RKT 27789 | H | Rt | Gastrointestinal—stomach ache, vomiting | Hu | Po | 44 | 0.44 | 35 | 89 | 0.89 |

| Other—spices and condiment, herbal tea | Co, Inf | 54 | ||||||||||

| Centella asiatica L. | Brahmi | RKT 28186 | H | L | General health care - Headache | Hu | Po | 28 | 0.28 | 28 | 28 | 0.28 |

| Coriandrum sativum L. | Dhaniya | RKT 28118 | H | Sd | Antidote—against poison | C | Em | 36 | 0.36 | 36 | 36 | 0.36 |

| Family:Araceae | ||||||||||||

| Acorus calamus L. | Bojh/Buch | RKT 27965 | H | Rh | Skeleton and muscles—sprain, inflammation | Hu | Pw, O | 55 | 0.55 | 21 | 74 | 0.74 |

| Other—insect repellent | I | Da | 53 | |||||||||

| Family:Asteraceae | ||||||||||||

| Ageratina adenophora (Spreng.) King & H. Rob. | Nargadiya/Pagaljhad | RKT 22106 | H | L | Dermatological—cuts and wounds | Hu | Po | 80 | 0.8 | 80 | 80 | 0.8 |

| Artemisia martima L. | Pati/Titpati | RKT 23793 | H | L | Dermatological—cuts and wounds, skin ailments | Hu | Po | 55 | 0.55 | 77 | 77 | 0.77 |

| Saussurea costus (Falc.) Lipsch. | Kut/Kuth | RKT 28203 | H | Rt | General health care—fever | Hu | Pw | 28 | 0.28 | 27 | 64 | 0.64 |

| Respiratory—cough | Pw | 8 | ||||||||||

| Gastrointestinal—stomach ache, dysentery | De | 29 | ||||||||||

| Taraxacum officinale Weber. | Dudhil | RKT 27817 | H | L,Rt | Antidote—snake bite | Hu | In, Po | 50 | 0.5 | 13 | 39 | 0.39 |

| Other—to increase lactation in mulching animals | C | Inf | 26 | |||||||||

| Tegetus erecta L. | Hazari | GBPCSED2 | H | L | General health care—fever, ear infection | Hu | Po | 51 | 0.51 | 46 | 61 | 0.61 |

| Dermatological—wounds | Po | 15 | ||||||||||

| Family:Berberidaceae | ||||||||||||

| Berberis asiatica Roxb. ex DC | Kilmori | RKT 22109 | S | Rt | General health care—fever | Hu | Pw | 42 | 0.42 | 13 | 54 | 0.54 |

| Circulatory—diabetes | Pw | 41 | ||||||||||

| Family:Boraginaceae | ||||||||||||

| Cynoglossum zeylanicum Thunb. Ex Lehm. | Chtkura | RKT 22969 | H | Rt | Dermatological—boils | Hu | Da | 54 | 0.54 | 54 | 54 | 0.54 |

| Family:Brassicaceae | ||||||||||||

| Rephanus sativus L. | Mooli | RKT 27049 | H | WP | Hepatic health cure—jaundice | Hu | Co | 87 | 0.87 | 87 | 87 | 0.87 |

| Family:Cannabaceae | ||||||||||||

| Cannabis sativa L. | Bhaang | GBPCSED3 | H | Sd, L | Gastrointestinal—purgative and laxative, carminative, constipation, stomach ache | Hu | In | 63 | 0.63 | 46 | 94 | 0.94 |

| Antidote—insect bite | Da | 5 | ||||||||||

| Other—warm effect in winters | In, Co | 43 | ||||||||||

| Family:Caryophyllaceae | ||||||||||||

| Drymaria cordata (L.) Willd. ex Schult | -- | RKT 19989 | H | WP | Respiratory—cough | Hu | In | 19 | 0.19 | 7 | 7 | 0.07 |

| Silene vulgaris (Moench) Garcke | Pyankura | GBPCSED4 | H | WP | General health care—fever | Hu | De | 15 | 0.15 | 4 | 17 | 0.17 |

| Gastrointestinal—removal of Ascaris (antiparisitic) locally known as juga | De | 13 | ||||||||||

| Family:Combretaceae | ||||||||||||

| Terminalia chebula (Gaertner) Retz. | Harar | RKT 15469 | T | Fr | Gastrointestinal—purgative and laxative, carminative, constipation, digestive problems, diarrhea | Hu | Pw, Po | 12 | 0.12 | 64 | 64 | 0.64 |

| Family:Cucurbitaceae | ||||||||||||

| Momordica charantia L. | Karela | RKT 27529 | Cl | Fr | Circulatory—diabetes | Hu | Co, In | 39 | 0.39 | 39 | 39 | 0.39 |

| Family:Dioscoreaceae | ||||||||||||

| Dioscorea deltoidea Wall. | Genthi | RKT 27301 | Cl | Fr (Atu) | Respiratory—cough and cold | Hu | Co | 32 | 0.32 | 32 | 32 | 0.32 |

| Family:Ericaceae | ||||||||||||

| Rhododendron arboreum Smth | Burans | RKT 27288 | T | F | Hepatic health cure—liver complaints, tonic | Hu | De | 47 | 0.47 | 64 | 64 | 0.64 |

| Family:Euphorbiaceae | ||||||||||||

| Emblica officinalis Gaertn. | Aanwla | RKT 21022 | T | Fr | Circulatory—diabetes | Hu | In | 35 | 0.35 | 8 | 85 | 0.85 |

| Gastrointestinal—purgative and laxative, carminative, stomach ache | In | 54 | ||||||||||

| Respiratory—cough | In | 6 | ||||||||||

| Other—source of vitamin “C” | In | 17 | ||||||||||

| Euphorbia prolifera Ehrenb. Ex. Boiss | Dudhiya, Maikuri | RKT 29216 | H | WP | Other—insect repellent | I | Da | 7 | 0.07 | 7 | 7 | 0.07 |

| Family:Gentianceae | ||||||||||||

| Swertia angustifolia | Chiraita | RKT 25110 | H | WP | General health care—fever | Hu | In | 37 | 0.37 | 19 | 24 | 0.24 |

| Buch.-Ham. ex D.Don | Dermatological—skin ailments | In | 5 | |||||||||

| Family:Fabaceae | ||||||||||||

| Glycine max (L.) Merri | Kala Bhatt | RKT 15664 | H | Sd | Hepatic health cure—jaundice | Hu | Co | 84 | 0.84 | 84 | 84 | 0.84 |

| Microtyloma uniflorum (Lam) Verdc. | Gahat/Kulthi | GBPCSED5 | H | Sd | Urinogenital disorder—stone | Hu | Co | 69 | 0.69 | 69 | 69 | 0.69 |

| Trifolium repens L. | Chalmoda | RKT 26479 | H | L | General health care—headache | Hu | Po | 44 | 0.44 | 18 | 22 | 0.22 |

| Dermatological—skin disease of dogs-Luta | C | Po | 4 | |||||||||

| Trigonella foemun-graecum L. | Maithi | RKT 28507 | H | L, Sd | Circulatory—diabetes | Hu | Inf | 31 | 0.31 | 11 | 61 | 0.61 |

| Gastrointestinal—carminative, obesity, indigestion, constipation | Inf | 47 | ||||||||||

| Skeleton and muscles—joint pain | Inf | 3 | ||||||||||

| Vigna mungo L. (Fabaceae) | Mass, Urad | RKT 27199 | H | Sd | Skeleton and muscles—fracture | Hu | In | 61 | 0.61 | 61 | 61 | 0.61 |

| Family:Lamiaceae | ||||||||||||

| Ajuga bracteosa Wall. ex Benth. | Ratpatia | RKT 25182 | H | WP | General health care—fever | Hu | De | 55 | 0.55 | 53 | 72 | 0.72 |

| Gastrointestinal—constipation | 16 | |||||||||||

| Urinogenital—diuretic | 3 | |||||||||||

| Ajuga parviflora Benth. | Ratpatia | RKT 26408 | H | Rt | General health care—fever, throat infection in animal (Galghotu) | Hu and C | De, Em | 56 | 0.56 | 58 | 87 | 0.87 |

| Gastrointestinal—constipation, stomach ache | Hu | De, In | 25 | |||||||||

| Urinogenital—stone | De | 4 | ||||||||||

| Leucas lanata Benth | Nirasi Jhad | RKT 29214 | H | L | Respiratory—cough | Hu | De | 80 | 0.8 | 80 | 80 | 0.8 |

| Mentha arvensis L. | Pudina | RKT 4355 | H | L | Gastrointestinal—stomach ache, vomiting | Hu | De | 43 | 0.43 | 50 | 50 | 0.5 |

| Micromeria biflora Benth. | -- | RKT 22949 | H | WP | General health care—fever | Hu | De | 6 | 0.06 | 6 | 6 | 0.06 |

| Ocimum basilicum L. | Tulsi | RKT 19325 | S | L, Sd | General health care—fever | Hu | De | 88 | 0.88 | 33 | 97 | 0.97 |

| Respiratory—cough and cold | De | 41 | ||||||||||

| Other—herbal tea, warm effect in winters | De | 23 | ||||||||||

| Origanum vulgare L. | Van Tulsi | RKT 29244 | L, Rt | General health care—fever | Hu | De | 31 | 0.31 | 15 | 71 | 0.71 | |

| Respiratory—cough and cold | De | 18 | ||||||||||

| Dermatological—wounds | Em | 29 | ||||||||||

| Other—herbal tea | Inf | 9 | ||||||||||

| Thymus serpyllum L. | Van-ajwayan | RKT 27966 | H | WP | Skeleton and muscles—joint pain | Hu | Em | 18 | 0.18 | 3 | 14 | 0.14 |

| Respiratory—asthma | Em | 3 | ||||||||||

| Gastrointestinal—digestive and stomach problems | Em | 4 | ||||||||||

| Other—spices and condiments | Da | 4 | ||||||||||

| Family:Liliaceae | ||||||||||||

| Asparagus racemosus Willd. | Keruwa | RKT 28055 | S | Rt | Immuno-regulatory—stimulant | Hu | Pw | 46 | 0.46 | 15 | 65 | 0.65 |

| Hepatic health cure—tonic | Pw | 39 | ||||||||||

| Gastrointestinal—stomach ache | De | 11 | ||||||||||

| Polygonatum cirrhifolium (Wall.) Royle | Maha-Meda | RKT 26144 | H | WP | Hepatic health cure—tonic | Hu | De | 21 | 0.21 | 13 | 34 | 0.34 |

| Dermatological—cuts and wounds | Po | 14 | ||||||||||

| Circulatory—blood purifier | Co | 7 | ||||||||||

| Polygonatum verticillatum L. | Meda | RKT 25894 | H | Rt | Gastrointestinal—carminative | Hu | In | 15 | 0.15 | 8 | 19 | 0.19 |

| Dermatological—wounds | Po | 11 | ||||||||||

| Family:Moraceae | ||||||||||||

| Ficus palmata Forsk. | Bedu | RKT 28094 | T | Lt | Dermatological—cuts and wounds | Hu | Da | 48 | 0.48 | 39 | 39 | 0.39 |

| Ficus roxburghii Wall. | Timul | GBPCSED6 | T | Fr | Gastrointestinal—acidity, carminative | Hu | Co | 26 | 0.26 | 45 | 48 | 0.48 |

| Circulatory—blood pressure | Co | 0 | 3 | 0 | ||||||||

| Family:Myricaceae | ||||||||||||

| Psidium guajava L. | Amrood | GBPCSED7 | T | L | General health care—mouth blisters (astringent) | Hu | In | 12 | 0.12 | 12 | 12 | 0.12 |

| Family:Orchidaceae | ||||||||||||

| Dactylorhiza hatagirea (D.Don) Soo | Salmpanja/Hattajari | RKT 26089 | H | Rt | Circulatory—bleeding | Hu | De | 17 | 0.17 | 17 | 34 | 0.34 |

| Dermatological—wounds | Po | 17 | ||||||||||

| Family:Plantaginaceae | ||||||||||||

| Plantago ovate Forsk. | Isabgoal | RKT 1899 | H | Sd | Gastrointestinal–constipation, digestive problems, diarrhea | Hu | In | 74 | 0.74 | 83 | 83 | 0.83 |

| Plantago lanceolata L. | Jonkpuri | RKT 8154 | H | Rt | Gastrointestinal—removal of stomach worm of domestic animals | C | In | 43 | 0.43 | 43 | 43 | 0.43 |

| Family:Poaceae | ||||||||||||

| Hordium vulgare L. | Jau | RKT 26630 | H | Sd | Hepatic health cure—warm and nutritive effect | Hu | Co | 46 | 0.46 | 46 | 63 | 0.63 |

| Dermatological—burns | O | 17 | ||||||||||

| Setaria italica L. | Kouni | RKT 7389 | H | Sd | Dermatological—measles and chicken pox | Hu | Co | 91 | 0.91 | 91 | 91 | 0.91 |

| Family:Podophyllaceae | ||||||||||||

| Podophyllum hexandrum Royle | Van-Kakri | RKT 27764 | H | Fr, Rt | Dermatological—wounds | Hu | Po | 19 | 0.19 | 19 | 19 | 0.19 |

| Family:Polygonaceae | ||||||||||||

| Rheum emodi Wall. | Dolu | RKT 27793 | H | Rt | General health care—fever | Hu | De | 31 | 0.31 | 15 | 42 | 0.42 |

| Dermatological—wounds | Po | 27 | ||||||||||

| Family:Punicaceae | ||||||||||||

| Punica granatum L. | Darim | RKT 28845 | T | Fr | Respiratory—cough and cold | Hu | In | 59 | 0.59 | 49 | 71 | 0.71 |

| Hepatic health cure—anemia | De | 10 | ||||||||||

| Other—source of vitamin “C” | De, In | 12 | ||||||||||

| Family:Ranunculaceae | ||||||||||||

| Aconitum heterophyllum Wall. | Atis | RKT 29008 | H | Rt | General health care—fever | Hu | Pw | 34 | 0.34 | 34 | 51 | 0.51 |

| Gastrointestinal—vomiting | In | 17 | ||||||||||

| Ranunculus repens L. | Aingadua | GBPCSED8 | H | Rt | Dermatological—boils | Hu | Po | 21 | 0.21 | 21 | 27 | 0.27 |

| Gastrointestinal—intestinal pains (NasPalatana) | In | 6 | ||||||||||

| Thalictrum foliosum DC. | Uppankat hi/Mamira | RKT 29204 | H | WP | Ophthalmic—eye infection (white dot-cataract) | Hu | Inf | 4 | 0.04 | 9 | 21 | 0.21 |

| Other—insect repellent | I | Da | 12 | |||||||||

| Family:Rosaceae | ||||||||||||

| Duchesnea indica (Andrews) Focke | Van Kafal | GBPCSED9 | H | L | Dermatological—burns and removal of burn scars | Hu | Po | 3 | 0.03 | 3 | 3 | 0.03 |

| Prunus persica Stokes. | Aaru | RKT 26465 | T | L | General health care—Headache | Hu | Po | 6 | 0.06 | 6 | 6 | 0.06 |

| Rosa moschata Hermm. | Kunja | RKT 28695 | S | L, F | Dermatological—cuts and wounds, boils | Hu | Po | 9 | 0.09 | 27 | 32 | 0.32 |

| Ophthalmic—eye diseases | Ste | 5 | ||||||||||

| Rubus ellipticus Smith. | Hisalu | RKT 29240 | S | Rt | General health care—fever | Hu | De | 9 | 0.09 | 9 | 18 | 0.18 |

| Gastrointestinal—stomach ache | De | 9 | ||||||||||

| Family:Rubiaceae | ||||||||||||

| Rubia cordifolia L. | Manjistha | RKT 27933 | H | Rt | General health care—fever | Hu | De | 27 | 0.27 | 23 | 23 | 0.23 |

| Family:Rutaceae | ||||||||||||

| Citrus aurantifolia (Christm) Sw. | Kagji | GBPCSED10 | T | Fr | General health care—headache | Hu | De | 38 | 0.38 | 20 | 94 | 0.94 |

| Nimboo | Gastrointestinal—constipation, weight loss | De | 23 | |||||||||

| Respiratory—cold | De | 19 | ||||||||||

| Other—herbal tea, source of vitamin “C” | De | 32 | ||||||||||

| Citrus hystrix DC. | Jamer/Jamir | GBPCSED11 | T | Fr | Gastrointestinal—removal of Ascaris (antiparisitic) locally known as juga | Hu | In | 38 | 0.38 | 27 | 50 | 0.5 |

| Respiratory—cold | In | 7 | ||||||||||

| Antidote—against poison | C | Em | 16 | |||||||||

| Zanthoxylum armatum DC | Timoor/Timuru | RKT 28615 | S | Sd | General health care—toothache | Hu | In | 61 | 0.61 | 21 | 77 | 0.77 |

| Respiratory—cough and cold | In | 19 | ||||||||||

| Gastrointestinal—carminative | In | 6 | ||||||||||

| Other—spices and condiments | In | 31 | ||||||||||

| Family:Saxifragaceae | ||||||||||||

| Bergenia ciliata (Haw) Sternb | Silphora | RKT 25124 | H | Rt | Urinogenital—urinary infection, stone | Hu | Inf, Pw | 51 | 0.51 | 61 | 61 | 0.61 |

| Family:Scorphulariaceae | ||||||||||||

| Picrorhiza kurrooa Royle. | Kutki | RKT 27765 | H | Rt | General health care—fever | Hu | In | 53 | 0.53 | 53 | 80 | 0.8 |

| Gastrointestinal—abdominal pain | In | 27 | ||||||||||

| Verbascum thapsus L. | Akalveer | RKT 27890 | H | WP | Dermatological—boils | Hu | Po | 63 | 0.63 | 17 | 42 | 0.42 |

| Other—to increase lactation in milching animals | Da | 25 | ||||||||||

| Family:Urticaceae | ||||||||||||

| Urtica dioica L. | Shishun/Bichhu ghas | RKT 22903 | S | L | Skeleton and muscles—joint pain | Hu | Da | 37 | 0.37 | 31 | 52 | 0.52 |

| Hepatic health cure—warm and nutritive effect | Hu | Co | 21 | |||||||||

| Family:Violaceae | ||||||||||||

| Viola betonicifolia J.E. Smith | Garurjadi/garurabuti | GBPCSED12 | H | WP | Antidote—snake bite | Hu | Po | 12 | 0.12 | 13 | 13 | 0.13 |

| Viola canescens Wall. Ex Roxb | Gulovansh | RKT 17561 | H | WP | Other—to increase lactation in milching animals | C | Da | 29 | 0.29 | 29 | 29 | 0.29 |

| Family:Zingiberaceae | ||||||||||||

| Curcuma longa L. | Haldi | RKT 5970 | H | Rh | General health care—internal injury | Hu | De | 78 | 0.78 | 39 | 91 | 0.91 |

| Dermatological—cuts and wounds, cosmetics | Da | 36 | ||||||||||

| Respiratory—cough | De | 16 | ||||||||||

| Hedychium spicatum Buch. Ham. ex Smith. | Van Haldi | RKT 24059 | H | Rh | Gastrointestinal—intestinal problems, purgative and laxative, carminative | Hu | Pw | 13 | 0.13 | 30 | 52 | 0.52 |

| Respiratory—cough | Pw | 8 | ||||||||||

| Dermatological—cosmetics, anti-lice | Hu & C | Pw | 14 | |||||||||

| Zingiber officinale Rosc. | Adrak | RKT 5921 | H | Rh | Respiratory—Cough and cold | Hu | Em | 89 | 0.89 | 89 | 89 | 0.89 |

Atu aerial tuber, B bulb, C cattle, Cl climber, Co cooking, De decoction, Da direct application, Em emulsion, F flower, Fr fruit, H herb, I insect, Inf infusion, In ingestion, hr hour, Hu human, L leaves, Lt latex, O ointment, Po poultice, Pw powder, Rh rhizome, Rt root, S shrub, Sd seed, Ste steam, T tree, WP whole plant

aUse citation of taxa (the no. of informants that referred the taxon)

bRFC = FC/N, where N is the total no. of informants

cUse reports of the taxon by ailment category

dUse reports of the taxon

eCI = UR/Nt, where Nt is the total no. of reported taxa

Fig. 3.

Distribution of medicinal plants in different life form

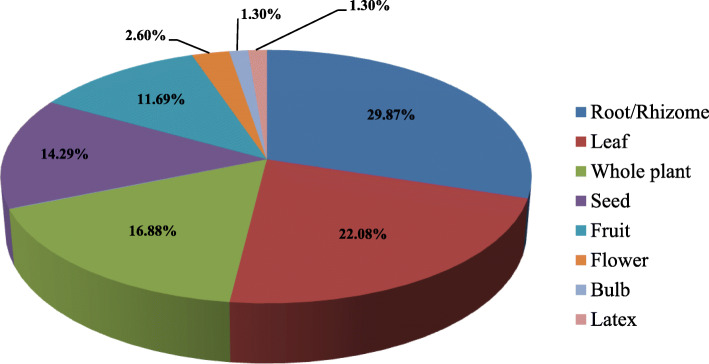

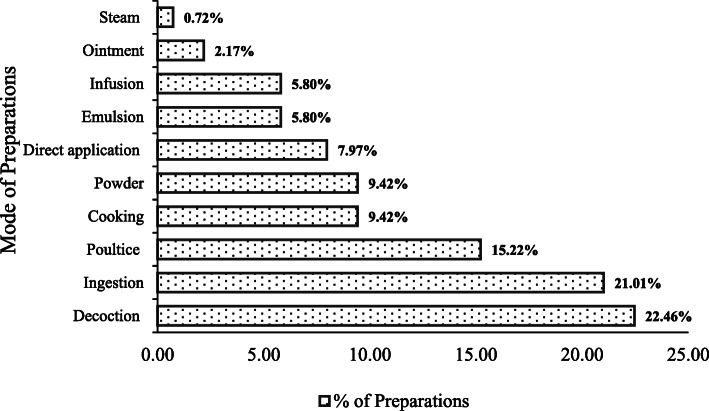

It was interesting to note that nearly 70% population still use prescription of Vaidyas for common ailments, although the Vaidyas were having an age of > 50 years. The diseases cured by Vaidyas comprised fever, stomach problems, cough, cold, headache, etc. The most common plant parts used were root/rhizome, followed by leaf, whole plant, seeds, fruits, flower, and bulb and latex (Fig. 4). The collection of plant parts was very selective keeping into consideration the time of collection, plant matureness, and quantity of use thus ensuring a conservation approach. Vaidyas comprised sound knowledge and a species-specific method of preparing drugs to cure various ailments (Table 2). Making decoction and ingestion was the most common mode of plant part use (Fig. 5). Poultice and cooking were also favored for many medicinal plants. Another mode of application includes cooking and making into powder (9.42%), direct application (7.97%), emulsion and infusion (5.80%), and ointment (2.17%) (Fig. 5). A decoction is the most commonly used method to cure ailments in traditional herbal systems [21–25]. It is considered to extract all potential bioactive compounds after heating [26]. The pleasant taste of the herbal drug can be attuned by adding together honey or sugar [27]. Ingestion and poultice were also common after crushing and/or mixing the plant parts with some solvent for application as paste and Band-Aid. In skeletal, muscle, and dermatological issues, application of plant parts as ointment was most prevalent.

Fig. 4.

Plant part used in preparation of medicine

Table 2.

Bio-processing of medicinal plants of District Bageshwar

| Scientific name | Mode of administration |

|---|---|

| Aconitum heterophyllum Wall. | Dry root powder (1 TS) taken orally with boiled water twice a day for 2–3 days against fever; 1–2 roots chewed to control vomiting. |

| Acorus calamus L. | Root powder mixed with grains used as insect repellent; 3–4 dry roots heated with mustard oil applied on the sprain and inflammatory region. |

| Ageratina adenophora (Spreng.) King & H. Rob | Leaf paste prepared from 100 g fresh leaf twigs applied on affected parts for early healing. |

| Ajuga bracteosa Wall. ex Benth. | Juice of whole plant (10–20 ml) taken twice a day for 2–3 days. |

| Ajuga parviflora Benth. | Decoction prepared from 100 g fresh or dried roots with water given 3–5 TS orally in fever, stomach ache, and constipation for 5 days; this decoction taken orally in empty stomach regularly for stone; 1–2 leaves chewed on empty stomach for gastric problem; decoction of whole plant (5–8) crushed with red chili (3) and 100 g Jiggery (Gur) given twice a day for 2–3 days to treat throat infection in domestic animals. |

| Allium sativum L. | Paste prepared from 5–7 spilled bulb heated with 20 ml mustard oil, massage on joints. |

| Angelica glauca Edgew. | Root powder (50 g) mixed with 100 ml water used to control vomiting and stomach ache; rhizomes are used as spices and condiments and tea (as flavor). |

| Artemisia martima L. | Juice (5–10 ml) of fresh leaf applied on the affected area. |

| Asparagus racemosus Willd. | Root decoction (100 g) prepared in water given to cure stomach ache (5 ml for adult, 1 TS for children) for 3–5 days, one palm full root powder taken with water as stimulant and tonic. |

| Berberis asiatica Roxb. ex DC | Root powder (100–150 g) taken with warm water given twice a day for 3 days against fever; fresh or dried roots soaked in water overnight, filtered, and taken orally to cure diabetes in empty stomach. |

| Bergenia ciliata (Haw) Sternb. | Fresh or dried roots (50–100 g) socked overnight and filtered, taken orally in morning for kidney stone. Root powder (50 g) taken with water twice a day for urinary infection. |

| Cannabis sativa L. | Grinded seeds cooked with some local vegetables (e.g., Colacasia esculanta, Brassica oleracea) for warm effect; broiled seeds are grinded with salt and green chili to prepare salt (Pahadi namak). Broiled seeds grinded with Punica garnatum mixed with green leaves of coriandum, green chili, salt, and sugar to prepare Chatni; fresh leaves crushed with 3–5 seeds of black pepper and applied on insect bite. |

| Centella asiatica L. | Fresh leaf paste is applied on forehead. |

| Citrus aurantifolia (Christm) Sw. | Juice extracted from fruit mixed with 1 TS honey, and 50 ml water taken orally in empty stomach for constipation and weigh loss; lemon tea used in fever and cold. |

| Citrus hystrix DC. | Fruit juice given orally (1 TS) to children for removal of Ascaris; cough and cold 10 ml thrice a day; fruit juice with mentha leaves (100 g) and coriander seeds made into paste given to domestic animals against poison. |

| Coriandrum sativum L. | Seed (80–100 g) paste mixed with 1–2 l processed curd (Mattha) is given to domestic animals against poison for 2–3 days. |

| Curcuma longa L. | Haldi powder (5 g) mixed with a full glass of warm milk for internal injury; paste of rhizome applied on cuts and wounds. |

| Cynoglossum zeylanicum Thunb. Ex Lehm. | Fresh or dried root paste applied on the affected parts. |

| Dactylorhiza hatagirea (D.Don) Soo. | Decoction of 100 g root with water taken orally (10–15 ml) twice a day for excessive bleeding; root paste applied on wounds. |

| Dioscorea bulbifera L. | Broiled fruit and cooked vegetable. |

| Drymaria cordata (L.) | Juice of aerial parts (2–4 drops) taken orally for 2–3 days. |

| Duchesnea indica (Andrews) Focke | Leaf paste is regularly applied on affected part. |

| Emblica officinalis Gaertn. | Fresh fruits are chewed regularly to control diabetes; dried fruits (3–5) boiled with water, filtered, and taken orally against cough and stomach ache; fresh and processed fruits are source of vitamin “C.” |

| Euphorbia sp. | Whole plant (50–100) mixed with FYM. |

| Ficus palmata Forsk. | Milky latex applied on cuts and wounds. |

| Ficus roxburghii Wall. | Fresh fruits are cooked as vegetable. |

| Glycine max (L.) Merri | Bhatt ka Jaula (an indigenous dish) is prepared from paste of seeds (soaked overnight) and cooked with rice in an iron vessel Kadahi. |

| Hedychium spicatum Buch. Ham. ex Smith. | Dried rhizome powder (2–3 g) taken with hot water once a day; paste of fresh rhizome used as anti-lice. |

| Hordium vulgare L. | Sattu prepared from 200 g broiled seeds mixed with 100 g jaggery (Gur) and 100 g Ghee for warm and nutritive effect; 50 g broiled seeds heated with 40 ml mustard oil applied on burns. |

| Leucas lanata Benth | Leaf juice with 3–5 drops of breast milk taken orally twice a day for 1 week. |

| Mentha arvensis L. | Leaves (100 g) boiled with water and filter, the filtrate (50 ml) given orally twice a day. |

| Micromeria biflora Benth. | Juice of whole plant with water (1–2 times in a day). |

| Macrotyloma uniflorum (Lam) Verdc. | Gahat ka Ras (an indigenous dish) prepared by 150 g seeds cooked with water (1 l) until the volume reduced (100 ml) and taken regularly. |

| Momordica charanti L. | Vegetable and juice (50 ml) of fresh fruit taken regularly. |

| Ocimum basilicum L. | Decoction of 100 g leaves and seeds, zinger (50 g), 5 seeds black paper with 150 ml water taken orally 2–3 times a day for fever, cough, and cold; aerial part used to make herbal tea. |

| Origanum vulgare L. | Decoction of 100 g fresh and dried leaves with water taken orally (10 ml) for a week in cough, cold, and fever; root paste applied on wounds. |

| Picrorhiza kurrooa Royle. | Decoction of 50 g root with water taken orally against fever and abdominal pain for 5–7 days. |

| Plantago ovate Forsk. | Seeds (10 g) soaked overnight or consumed directly with water twice a day for 30 days against constipation and digestive problems; Isabgoal (15 g) mixed with 10 TS fresh curd taken after meal for diarrhea. |

| Plantego lanceolata L. | Paste of roots (100 g) given to domestic animals. |

| Podophyllum hexandrum Royle | Root paste applied on wound. |

| Polygonatum cirrhifolium (Wall.) Royle | Small pieces of tuber (8–10) soaked in water for overnight, taken in empty stomach for weakness, and develop immunity; cooked green leaves eaten as blood purifier; root paste applied on cuts and wounds. |

| Polygonatum verticillatum L. All | Root powder (50 g) is taken with warm water in gastric complaints; fresh root paste applied for wound healing. |

| Prunus persica Stokes. | Fresh leaf paste applied on head for 2–3 h. |

| Psidium guajava L. | Fresh leaves are chewed. |

| Punica granatum L. | Powder (50 g) of dried fruit peel taken orally with warm water for old cough; fruit juice (50 ml) given twice a day to anemic patient. |

| Ranunculus repens L. | Root paste (50 g) applied for boils, and 30–50 ml filtered root extract (juice) is given twice a day against intestinal pain. |

| Rephanus sativus L. | Vegetable prepared from fresh leaves and root as salad. |

| Rheum emodi Wall. | Decoction of 100 g root with warm water taken orally (10 ml) for fever twice a day; root paste applied on wounds. |

| Rhododendron arboreum Smth | Juice extracted from fresh flowers |

| Rosa moschata Hermm. | Fresh leaf paste is applied on cuts, wounds, and boils; water extracted from fresh flowers used in eye diseases. |

| Rubia cordifolia L. | Root decoction with water given orally (1–2 TS) against fever twice a day to children (5 months–10 years) |

| Rubus ellipticus Smith. | Decoction (10 ml) of 100 g roots with water taken orally against fever and stomach ache for 5 days. |

| Saussurea costus (Falc.) Lipsch | Decoction of root (50 g) with water given against dysentery for 3–5 days twice a day; root powder (50 g) taken orally with boiled water in fever, cough, and stomach ache. |

| Setaria italica L. | Koni ka Jaula (an indigenous dish) prepared from seeds cooked with water. |

| Silene vulgaris (Moench) Garcke | Root decoction (10 ml) with warm water given against fever for 3 days; 1 TS is used for removal of Ascaris (Juga); leaves are used as a vegetable. |

| Swertia spp. | Juice of fresh leaves (100 g) given with boiled water 3 TS for 3–5 days for fever; Panchang (whole plant) is used after soaking overnight and taken (50–100 ml) orally in empty stomach for 15 days. |

| Taraxacum officinale Weber. | For snake bite: juice of whole plant with water taken orally (1–2 TS) thrice a day and applied on injured part for 1 week; mixture of 100 g roots with 9 seeds of black pepper, 1–2 l processed curd (Mattha), and 250 g paste of black soybean given to increase lactation in milching animals. |

| Tegetus erecta L. | Fresh leaf juice with water taken against fever (3–5 TS twice a day); leaf extract (2–3 drops) in ear infection; fresh leaf paste is applied for healing cuts and wounds. |

| Terminalia chebula (Gaertner) Retz. | Dried fruit powder (100 g) given orally with boiled water twice a day for 3–5 days in stomach ache; dried fruit crushed with water and given (1–2 ml) orally to children (3 months to 5 years) and small amount applied around the navel. |

| Thalictrum foliosum DC. | Fresh roots (50 g) soaked in rose water (100 ml) for overnight, filtered, and used as eye drop. |

| Thymus serpyllum L. | Paste of whole plant mixed with mustard oil gently applied on joints; whole plants juice (10 ml) mixed with honey (20 g) is taken orally for cough and asthma; broiled seeds (10–15 g) with warm water taken for digestive and stomach problems; leaves and seeds are used as spices and condiment. |

| Trifolium repens L. | Leaf paste (5 g) with water. |

| Trigonella foemun-graecum L. | Leaf juice is taken orally for curing obesity, indigestion, joints pain, and constipation; 25 g seeds are soaked overnight filter; the filtrate taken orally in empty stomach for gastric problems and diabetes. |

| Urtica dioica L. | Branches with leaves are gently rubbed on joints and muscles; fresh leaf twigs taken as vegetable; fine powder of dry leaf (5–10 g) dissolve in 50 ml water is taken orally in joints and muscular pain. |

| Verbascum thapsus L. | Fresh leaf paste applied on affected part for boils; 8–10 whole plants mixed with grass given mulching animals. |

| Viola betonicifolia J.E. Smith (Violaceae) | Paste of whole plant (fresh or semidry) applied on affected part for 1–2 weeks. |

| Viola canescens Wall. Ex Roxb | Fresh plants (30–50) given with grass for 1 to 2 weeks. |

| Vigna mungo L. | Paste prepared by grinding of 150 g seeds with water applied on the fractured part. |

| Zanthoxylum armatum DC | Seeds (100 g) boiled with water taken orally twice a day; seed bark used as a spices. |

| Zingiber officinale Rosc. | A piece (5–10 g) of broiled rhizome mixed with small amount of honey and chewed. |

FYM farm yard manure, TS tablespoon

Fig. 5.

Processing of plant parts in preparation of medicine

The community and Vaidyas identify each medicinal plant with a specific vernacular name. For example, Bergenia ciliata is identified by the community with a local name “Pattharchatta” (stone destroyer), and it is used in curing kidney stones. Plantago ovate is called “Jonkpuri” (jonk resembles worms) and is used in the treatment of Ascaris and other worms. Viola betonicifolia named “Garur-Jadi” (Garur means eagle), and it is used as an antidote to treat snake bites. Commonly, the community identifies a native name for species based on its local uses, ecology, physiology, anatomy, pharmacological activity, etc. [28].

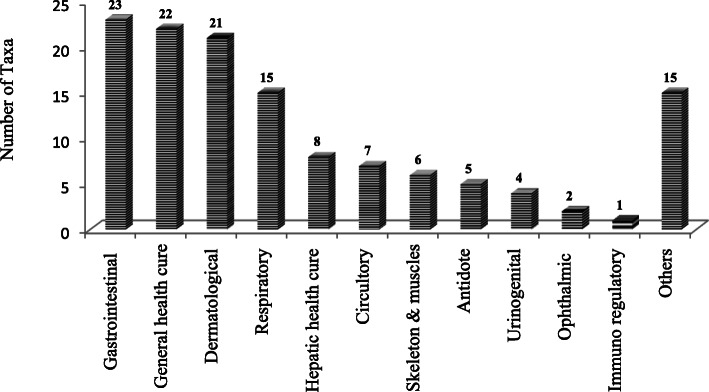

It was recorded that the species were used to cure a total of 12 major ailments (Fig. 6). Most species were used for curing gastrointestinal and general health disorders. It was followed by species used for treating dermatological and respiratory problems.

Fig. 6.

Distribution of medicinal plants in different ailments category

Lamiaceae has been the most dominating family for ethnomedicinal uses in the trans-Himalayan zone of Nepal [29] and Garhwal Himalaya in India as well [30]. Although the people in remote areas are still dependent on the traditional herbal cure system, it is being practiced by a few elderly people only. The young generation is not interested to take up this profession given minimal profit [3, 10, 12]. The common plant parts used in the present study are similar to other investigations [31–35]. The roots being the storage part of the plant contain valuable bioactive compounds [36]. Apart from the root part, leaves also contain a high concentration of health-beneficial secondary metabolites, phytochemicals, and essential oils, which contribute significantly to phototherapy or treatment of various health disorders [37–40]. The study reports 60% more species than reported earlier for the area under investigation [41–45].

Quantitative analysis of ethnomedicinal information

The use value of important ethnomedicinal species was also calculated to depict the number of uses reported by the informants related to the utility of a species for a specific ailment or different ailments (Tables 1 and 3). Two forms of use reports were analyzed; the URc defines the use of a particular species to cure specific ailments as reported by all the informants, while URd reports the sum of all the uses for a particular disease/ailment. Ocimum basilicum, Cannabis sativa, Citrus aurantifolia, Curcuma longa, and Setaria italica have been top positioned in terms of use-reports and different ailments cured.

Table 3.

Use value of important ethnomedicinal species of target area

| Taxa | URa | FCb | CIc | NDAS | Ailments categories (decreasing order) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Ocimum basilicum L. | 97 | 88 | 0.97 | 5 | Respiratory, general health care, and others |

| Cannabis sativa L. | 94 | 63 | 0.94 | 6 | Gastrointestinal, others, and antidote |

| Citrus aurantifolia (Christm) Sw. | 94 | 38 | 0.94 | 6 | Others, gastrointestinal, general health care, and respiratory |

| Curcuma longa L. | 91 | 78 | 0.91 | 5 | General health care, dermatological, and respiratory |

| Setaria italica L. | 91 | 91 | 0.91 | 2 | Dermatological |

| Angelica glauca Edgew. | 89 | 44 | 0.89 | 4 | Others and gastrointestinal |

| Zingiber officinale Rosc. | 89 | 89 | 0.89 | 2 | Respiratory |

| Ajuga parviflora Benth. | 87 | 56 | 0.87 | 5 | General health care, gastrointestinal, and urinogenital disorder |

| Rephanus sativus L. | 87 | 87 | 0.87 | 1 | Hepatic health cure |

| Emblica officinalis Gaertn. | 85 | 35 | 0.85 | 6 | Gastrointestinal, others, circulatory, and respiratory |

| Glycine max (L.) Merri | 84 | 84 | 0.84 | 1 | Hepatic health cure |

| Plantago ovate Forsk. | 83 | 74 | 0.83 | 3 | Gastrointestinal |

| Ageratina adenophora (Spreng.) King & H. Rob. | 80 | 80 | 0.80 | 2 | Dermatological |

| Leucas lanata Benth | 80 | 80 | 0.80 | 1 | Respiratory |

| Picrorhiza kurrooa Royle. | 80 | 53 | 0.80 | 2 | General health care and gastrointestinal |

| Artemisia martima L. | 77 | 55 | 0.77 | 3 | Dermatological |

| Zanthoxylum armatum DC | 77 | 61 | 0.77 | 5 | Others, general health care, respiratory, and gastrointestinal |

| Acorus calamus L. | 74 | 55 | 0.74 | 3 | Others and skeleton and muscles |

| Ajuga bracteosa Wall. ex Bent. | 72 | 55 | 0.72 | 3 | General health care, gastrointestinal, and urinogenital disorder |

| Origanum vulgare L. | 71 | 31 | 0.71 | 5 | Dermatological, respiratory, general health care, and others |

| Punica granatum L. | 71 | 59 | 0.71 | 4 | Respiratory, others, and hepatic health cure |

NDAS no. of different ailment subcategories

aTotal no. of use-reports of the taxon

bUse citation of taxa (the no. of informants that referred the taxon)

cCI = UR/Nt, where Nt is the total no. of reported taxa

The usefulness of a species can be represented through its RFC value, which ranged 0.03 to 0.91 for different species (Table 1). Species with maximum RFC value were Setaria italica, Zingiber officinale, Ocimum basilicum, and Raphanus sativus which depict their higher use, while those with the least value comprised Duchesnea indica and Thalictrum foliosum.

The cultural importance index (CIs) specifies the distribution and importance of species in traditional herbal system, and the value ranged from 0.03 to 0.97. A total of 21 species have been identified as the most commonly used (Table 3). Ocimum basilicum, Cannabis sativa, and Citrus aurantifolia registered the highest cultural importance in the traditional herbal cure system. Low CI values specify that these species are either least used, or their use is declining in traditional herbal cure system [46].

An analysis of the informant consensus factor (Fic) for 12 broad treatment categories ranged between 0.92 and 1.0 (Table 4). The data revealed high homogeneity as per local people for all treatments. The immuno-regulatory category was assigned the value 1 due to the presence of only one taxon in the particular category. Apart from this, hepatic health care and urogenital categories obtained the value of 0.98 indicating well-defined criteria among the local population and non-random selection of species for the ailment category. Asparagus recemosus, Glycine max, Hordeum vulgare, Polygonatum cirrhifolium, Punica granatum, Raphanus sativus, and Urtica dioica not only used in hepatic health care but also provide nutritive benefits and warm potency, particularly at higher altitude areas. These species are commonly used in the daily food habit of the local community. Also, a higher value of Fic verifies the distribution of the different species used for a specific ailment. The urogenital category, with only 4 taxa included, comes second in terms of CI as there is a widely accepted notion of using these species for such disorders. The higher value of informant consensus factor for all the ailment categories also implies that the documented species are the most commonly used in traditional healing system.

Table 4.

Informant consensus factor (Fic) and medicinal importance (MI) of ethnomedicinal plants

| Ailments category | No. of taxa (Nt)a | Frequency (%)b | No. of use reports (Nur) | Informant consensus factor (Fic)c | Medicinal importance (MI)d |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Gastrointestinal | 23 | 32.86 | 695 | 0.97 | 30.22 |

| General health cure | 22 | 31.43 | 524 | 0.96 | 23.82 |

| Dermatological | 21 | 30.00 | 617 | 0.97 | 29.38 |

| Respiratory | 15 | 21.43 | 402 | 0.97 | 26.80 |

| Hepatic health cure | 8 | 11.43 | 364 | 0.98 | 45.50 |

| Circulatory | 7 | 10.00 | 126 | 0.95 | 18.00 |

| Skeleton and muscles | 6 | 8.57 | 178 | 0.97 | 29.67 |

| Antidote | 5 | 7.14 | 83 | 0.95 | 16.60 |

| Urinogenital | 4 | 5.71 | 137 | 0.98 | 34.25 |

| Ophthalmic | 2 | 2.86 | 14 | 0.92 | 7.00 |

| Immuno-regulatory | 1 | 1.43 | 15 | 1.00 | 15.00 |

| Other | 15 | 21.43 | 377 | 0.96 | 25.13 |

aNo. of species listed in several of the categories of medicinal usage

bPercentage of records on the total of 70 records

cFic = (Nur − Nt)/(Nur − 1)

dMI = Nur/Nt

The gastrointestinal ailments comprised of 695 use reports from the total categories with a medicinal importance index value of 30.22 (Table 4). Some most sought species in this category are Cannabis sativa, Citrus aurantifolia, Angelica galuca, Ajuga parviflora, and Emblica officinalis. These species are placed following their use reports mentioned during data collection. In the category of general health care, 22 species are being used with 524 numbers of use-reports and medical importance of 23.82. The species indicated with the highest number of use-reports are Ocimum basilicum, Citrus aurantifolia, Curcuma longa, Ajuga parviflora, and Picrorhiza kurrooa based on user reports. The dermatological category ranks third with 21 taxa in use and a use-report value of 617 and medicinal importance of 29.82. The main species employed for this category based on the use reports are Setaria italica, Eupatorium adenophorum, and Artemisia martima. Although the hepatic health cure category comprised of only 8 taxa, it has a medicinal importance index value of 45.50, which is highest of all the categories since the species used under the category are of daily usage and are often included in daily food products with nutritive values. The species include Glycine max, Hordeum vulgare, Punica granatum, Urtica dioica, Polygonatum cirrhifolium, etc. In other works carried out in Uttarakhand, they have reported these medicinal plants and use different plant parts in a different ratio to cure disease or aliments [16, 30, 31, 41–43, 45, 47–49].

A correlation analysis was done among RFC, CI, UR, number of species used in treating different ailments, informant consensus factor (Fic), and medical importance. No evidence of any correlation was observed in most of the parameters; a highly positive correlation was only observed in the number of taxa used and the number of use reports (0.963). Also, there has been a moderately positive correlation observed between Fic and RFC which is of no significance in the study as both the parameters have been described differently.

Some species are also used in ethnoveterinary purposes for curing domestic animals. Ajuga parviflora is used to cure throat infection, Coriandrum sativum against poison, and Taraxacum officinale, Verbascum thapsus, and Viola canescens to increase lactation in milking animals.

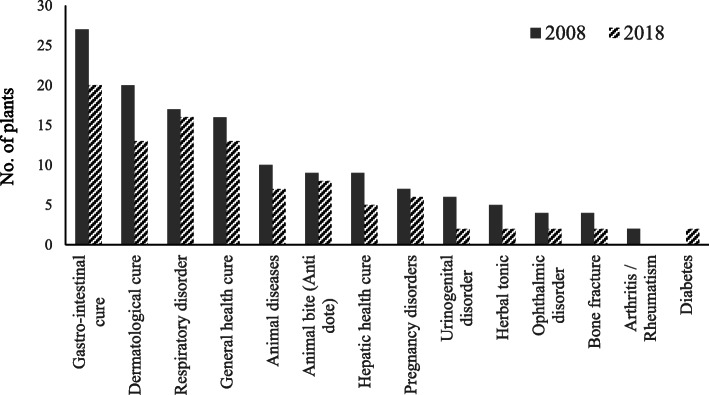

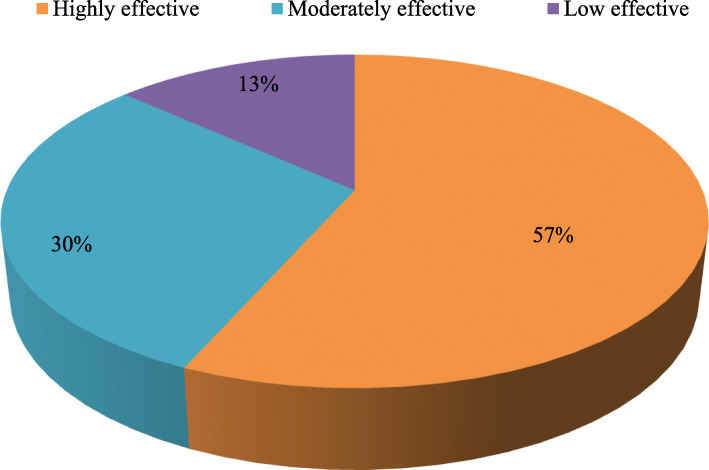

The weakening of traditional ethnobotanical knowledge

It is alarming to note that there has been a continued decline in traditional ethnobotanical knowledge in the target area (Fig. 7). An analysis of community perception on change in use pattern of medicinal plants in 2018 and a decade earlier (i.e., 2008) revealed that there is less number of species used for curing different ailments in recent years (Table 5). People are moving away from traditional herbal cure system, and the young generation has no interest in the traditional customs and values. Earlier, the people of remote areas preferred to consult with Vaidyas for primary healthcare, but in the last decade, since there is an increase in accessibility, availability, and affordability towards the allopathic medicinal system, the local community is also opting for such options. Despite that 57% of the total respondents believe that these plants are highly effective, 30% found moderately effective, while only 13% feel it less effective (Fig. 8). Interestingly, to cure selective diseases in children, such as Juga (removal of Ascaris), Chupad (heavy cough), and Kasar (constipation), still people prefer traditional cure systems as it has no side effects. During the study, it was observed that the Vaidyas do not share their knowledge; they believed that the treatment will not be effective if they share the knowledge with anybody. In the changing lifestyle and socioeconomic scenarios, most of the inhabitants are reluctant to live with their traditional heritage leading to the vanishing of the knowledge [58].

Fig. 7.

Past (2008) and present (2018) use of plants in traditional health care system

Table 5.

Similarity between present and past ethnomedicinal uses of important species

| Botanical name | Use reports in study area | Earlier use reports from Uttarakhand |

|---|---|---|

| Aconitum heterophyllum Wall. | Fever and vomiting | Fever, vomiting, and cough [21, 28, 51, 58] |

| Acorus calamus L. | *Inflammation and insect repellent | Arthritis, cancer, convulsions, diarrhea |

| Sprain | Dyspepsia, epilepsy [41, 43]; sprain [50] | |

| Ageratina adenophora (Spreng.) | Cuts and wounds | Cuts and wounds [31, 41] |

| Ajuga bracteosa Wall. ex Benth. | *Constipation | Fevers, diuretic [41] |

| Diuretic, fever | ||

| Ajuga parviflora Benth. | *Constipation, stone, throat infection in animal (Galghotu) | Headache, fever, stomach ache [51] |

| Fever, stomach ache | ||

| Allium sativum L. | *Joint pain (arthritis) | Muscular pain [43, 52]; ear pain [58] |

| Angelica glauca Edgew. | *Spices and condiment and herbal tea | Constipation, bronchitis, and stomach |

| Stomach ache, vomiting | Disorders, vomiting [31, 43, 50] | |

| Artemisia martima L. | Cuts, skin ailments, wounds | Skin ailments [51] |

| Asparagus racemosus Willd. | *Stimulant, tonic, and stomach ache | Leucorrhoea, headache, hysteria, ulcer, liver disorders [41, 43] |

| Berberis asiatica Roxb. ex DC | *Fever | Diabetes, jaundice [41] |

| Diabetes | ||

| Bergenia ciliata (Haw) Sternb | Urinary infection and stone | Fever, digestive disorders, skin diseases, urinary infection, and stone [16, 31] |

| Cannabis sativa L. | *Insect bite, stomach ache, purgative and laxative, warm effect in winters | Analgesic, cough, cold, sedative, narcotic, skin diseases [43] |

| Carminative, constipation | ||

| Centella asiatica L. | *Headache | Inflammatory infections, wounds [41, 43] |

| Citrus aurantifolia (Christm) Sw. | Cold, constipation, headache, herbal tea, source of vitamin “C,” and weight loss | Diarrhea, dysentery, fever, headache [53] |

| Citrus hystrix DC. | *Against poison, cold, removal of Ascaris (anti-parasitic) | Vomiting [52] |

| Coriandrum sativum L. | *Against poison | Stomachic and diuretic [43] |

| Curcuma longa L. | *Internal injury | Skin disorders, wound healing [43, 52] |

| Cough, cuts and wounds, and cosmetics | ||

| Cynoglossum zeylanicum Thunb. ex Lehm. | *Boils | Asthma, bronchitis, cough, vomiting [16, 54] |

| Dactylorhiza hatagirea (D.Don)Soo | Bleeding and wounds | Burns, cuts, checks bleeding [31, 41] |

| Dioscorea deltoidea Wall | Cough and cold | Cough, fever, urinogenital disorders [31, 41, 43, 51] |

| Drymaria cordata (L.) Willd. ex Schult | *Cough | Laxative [49]; bile complaints [51] |

| Duchesnea indica (Andrews) Focke | *Burns and removal of burn scars | Diarrhea, fever, leucorrhoea [54]; skin diseases [53] |

| Emblica officinalis Gaertn. | Diabetes, purgative and laxative, carminative, stomach ache, and source of vitamin “C” | Asthma, digestive disorders, hair fall [31]; dysentery, cholera, and jaundice [41, 51] |

| Euphorbia prolifera Ehrenb. ex Boiss | *Insect repellent | -- |

| Ficus palmata Forsk. | *Cuts and wounds | Lungs diseases, skin diseases [43, 49, 51] |

| Ficus roxburghii Wall. | *Acidity, source of vitamin “C” | Laxative [49] |

| Glycine max (L.) Merri | *Jaundice | -- |

| Hedychium spicatum Buch. Ham. ex Smith. | Anti-lice, cough, cosmetics, intestinal problems, purgative and laxative, carminative | Carminative, stomachic, liver complaints, fevers, vomiting, diarrhea, inflammation, snake bite [16, 41, 51] |

| Hordium vulgare L. | *Burns, warm, and nutritive effect | -- |

| Leucas lanata Benth | *Cough | Cuts, to check bleeding, wounds [51] |

| Mentha arvensis L. | Stomach ache and vomiting | Diarrhea, stomach ache [51, 55] |

| Micromeria biflora Benth. | *Fever | Joints pain, worm infested wounds [41] |

| Microtyloma uniflorum (Lam) Verdc. | Stone | Stone [52] |

| Momordica charantia L. | Diabetes | Jaundice, diabetes [43] |

| Ocimum basilicum L. | Cough and cold, fever, herbal tea, warm effect in winters | Cough, cold, fever [16] |

| Origanum vulgare L. | Cough and cold, fever, herbal tea, and wounds | Cold, diarrhea, fever, indigestion, influenza, menstrual disorder [43, 51] |

| Picrorhiza kurrooa Royle. | Abdominal pain, fever | Anemia, asthma, blood troubles, inflammation, jaundice [41]; fever, stomach ache [31]; abdominal pain, cataract [50, 51] |

| Plantago ovate Forsk. | Constipation, digestive problems, and diarrhea | Constipation, dysentery, and diarrhea [41] |

| Plantego lanceolata L. | *Removal of stomach worm of domestic animals | Dyspepsia, sore wounds, dysentery, purgative, mouth disease, and chicks [41] |

| Podophyllum hexandrum Royle | Wounds | Purgative, cancer [41]; wounds [31] |

| Polygonatum cirrhifolium (Wall.) | *Blood purifier, cuts, tonic, and wounds | Anemia, fever, bronchitis, general debility [ 54] |

| Polygonatum verticillatum L. | Carminative and wounds | Aphrodisiac, gastric complaints, nervine tonic, wound healing [43, 51] |

| Prunus persica Stokes. | *Headache | Ear infection of children [31]; antipyretic, brain tonic [21] |

| Psidium guajava L. | Mouth blisters (astringent) | Mouth blisters [51, 59] |

| Punica granatum L. | *Anemia, cough, cold, source of vitamin “C” | Diarrhea, dysentery, piles [41] |

| Ranunculus repens L. | *Boils and intestinal pains (Nas Palatana) | -- |

| Rephanus sativus L. | Jaundice | Jaundice [52] |

| Rheum emodi Wall. | Fever and wounds | Cuts, fracture, wounds [56] |

| Rhododendron arboreum Smth | Liver complaints, tonic | Heart tonic [31], stomach diseases [41] |

| Rosa moschata Hermm. | *Boils, cuts, eye diseases, wounds | Leucorrhoea, bleeding, pregnancy termination [16] |

| Rubia cordifolia L. | *Fever | Blood purifier, joints pain, leucorrhoea, cuts, wounds, insect sting [51] |

| Rubus ellipticus Smith. | *Fever and stomach ache | Blood pressure, diarrhea [41] |

| Saussurea costus (Falc.) Lipsch. | Cough, dysentery, fever, stomach ache | Asthma, cough, dysentery, fever [51, 55]; abdominal pain [58] |

| Setaria italic L. | *Chicken pox and measles | -- |

| Silene vulgaris (Moench) Garcke | *Fever and removal of Ascaris (anti-parasitic) | Asthma, bronchitis [16] |

| Swertia angustifolia Buch.-Ham. ex D.Don. | *Skin ailments | Pneumonia, cold, cough, fever [51] |

| Fever | ||

| Taraxacum officinale Weber. | *Snake bite and to increase lactation in mulching animals | Headache, acts as a heart tonic and blood purifier [28, 58] |

| Tegetus erecta L. | *Ear infection, fever, and wounds | Muscular pain, piles, ulcer, wound healing [43] |

| Terminalia chebula (Gaertner) Retz. | Carminative, constipation, digestive problems, diarrhea, purgative | Asthma, digestive problems, diarrhea, purgative [16, 31] |

| Thalictrum foliosum DC. | *Eye infection (white-dot-cataract), insect repellent | Gastric trouble, used to control external parasites [41] |

| Botanical name | Uses report in study area | Earlier uses report from Uttarakhand |

| Thymus serpyllum L. | *Asthma, joint pain, spices, and condiments | Laxative, stomachic [41]; cough, epilepsy, itching, and skin diseases |

| Digestive and stomach problems | Menstrual disorders, swelling [51] | |

| Trifolium repens L. | *Headache and skin disease of dogs | Astringent [16] |

| Trigonella foemun-graecum L. | Carminative, constipation, diabetes, indigestion, joint pain, and obesity | Diabetes, rheumatism [16, 52] |

| Urtica dioica L. | *Joint pain, warm and nutritive effect | Skin diseases, boils [31, 41]; bone fracture [51] |

| Verbascum thapsus L. | *To increase lactation in milching animals | Cough, fever, rheumatism [41]; boils eye cataract [51] |

| Boils | ||

| Viola betonicifolia J.E. Smith | *Snake bite | Blood diseases, cough, fever, skin [57] |

| Viola canescens Wall. Ex Roxb | *To increase lactation in milching animals | Cough, cold, malaria, jaundice [43, 49] |

| Vigna mungo L. | *Fracture | -- |

| Zanthoxylum armatum DC | Carminative, cough and cold, toothache, spices and condiments | Toothache [31]; constipation, gastric disorders [41, 43, 50] |

| Zingiber officinale Rosc. (Zingiberaceae) | Cough and cold | Asthma, cough, and cold [43] |

*New ethnomedicinal use reports documented from study sites

Fig. 8.

Community view points on effectiveness of traditional health care system

Conclusions

Community knowledge on the use and management of wild plant resources has always been integral to the survival, sustenance, and adaptation of human cultures [47, 53, 58]. This study revealed 70 medicinal plant species being used by the local marginal community of which 21 are the most extensively used species to treat various ailments. The significance of the traditional herbal healing system is highly relevant due to its effectiveness. It is cost-effective and based on local resources and still only means of cure for marginal communities in remote localities of Uttarakhand. With population growth and lack of health care, there is a need to adhere to the locally available resources to be utilized for general health care and provisioning of suitable side-effect free treatment to the communities. The community still uses these species; however, the level of use is decreasing because of upcoming modern allopathic based health care services. At the same time, there is also a decline in the number of local Vaidyas and herbal practitioners. This is because of increased access to modern hospitals and medicinal facilities in recent times. This possesses a significant challenge to the continuity of the traditional herbal cure system. The impoverishment of such knowledge may lead to an enormous loss to the scientific community. The ethnomedicinal knowledge and information provided in this study are of significant value for scientific validation, product development, conservation, and policy planners for sustainable management of medicinal plants and traditional herbal cure system. It is suggested to explore and establish linkage between traditional health practices and modern health care systems. It can be done by testing bioactive compound and biological activity of most preferred plant species and assessing the safety and efficacy of the local herbal formulation. Such an investigation may lead to many new and novel drug discovery. It is also recommended that the natural habitats of medicinal plants should be protected for the conservation of valuable gene pool and to control the exploitation of species. Since ethnomedicinal information is strongly linked to local livelihoods, culture, and environment, it is strongly recommended to further continue studying the subject to serve humanity with healthier and operative health care measures.

Acknowledgements

We owe our gratitude to the people of Garur-Ganga valley and Saryu valley of District Bageshwar, Uttarakhand, who shared the valuable information and knowledge. The authors thankfully acknowledge the facilities received from GBPNIHE, Kosi-Katarmal, Almora, India, for undertaking this work. We are thankful to DST, Govt. of India for the financial assistance provided under a NMSHE, Task Force 5 sponsored project entitled “Network program on the convergence of traditional knowledge system for sustainable development in the Indian Himalayan Region.” We sincerely thank Dr Deepshikha Arya, Research Officer, CCRAS-RARI, Ranikhet, for her support to help in identifying the plant species, as well as Prof. S.C. Garkoti, JNU for his constant support and cooperation.

Authors’ contributions

SNO, DT, and AA planned and performed the study and field survey, wrote the draft manuscript, and analyzed the data, and RCS revised the manuscript and data analysis. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Funding

The study has been funded by Department of Science and Technology, Govt. of India under National Action Plan for Climate Change (NAPCC) through National Mission on Sustaining Himalayan Ecosystems (Task Force 5-Network programme on the convergence of traditional knowledge system for sustainable development in the Indian Himalayan Region).

Availability of data and materials

The authors already included all data in the manuscript collected during the field surveys. The documented medicinal plant species were deposited at Centre of Socio-economic Development (CSED), GBPNIHE, Kosi-Katarmal, Almora, Uttarakhand.

Ethics approval and consent to participate

During field work, prior consent of the informants was taken conducting these studies. This was done to adhere to the ethical standards of community participation in scientific research.

Consent for publication

Not applicable.

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Footnotes

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Contributor Information

S. N. Ojha, Email: ojhasn16@gmail.com

Deepti Tiwari, Email: pandeydeepti1990@gmail.com.

Aryan Anand, Email: aryananand2010@gmail.com.

R. C. Sundriyal, Email: sundriyalrc@yahoo.com

References

- 1.Kala CP. Medicinal plants conservation and enterprise development. Med Plants. 2009;1(2):79–95. [Google Scholar]

- 2.L.K Rai LK, Prasad P, Sharma E. Conservation threats to some important medicinal plants of Sikkim Himalaya. Biol Conser. 2000; 93(1):27-33.

- 3.Kala CP, Dhyani PP, Sajwan BS. Developing the medicinal plants sector in northern India: challenges and opportunities. J Ethnobiol Ethnomed. 2006;2(1):32. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Caniago Izefri, Stephen F. Siebert. Medicinal plant ecology, knowledge and conservation in Kalimantan, Indonesia. Economic Botany. 1998;52(3):229–250. [Google Scholar]

- 5.Kuniyal CP, Bisht VK, Negi JS, Bhatt VP, Bisht DS, Butola JS, Sundriyal RC, Singh SK. Progress and prospect in the integrated development of medicinal and aromatic plants (MAPs) sector in Uttarakhand. Western Himalaya. Environ Develop Sustaina. 2015;17(5):1141–1162. [Google Scholar]

- 6.Rossato SC, Leitao-Filho H, Gegossi A. Ethnobotany of caicaras of the Atlantic forest coast (Brazil) Econ Bot. 1999;53:387–395. [Google Scholar]

- 7.Hanazaki N, Tamashiro JY, Leitao-Filho H, Gegossi A. Diversity of plant uses in two caicaras communities from the Atlantic forest coast. Brazil. Biodivers Conserv. 2000;9:597–615. [Google Scholar]

- 8.Gazzaneo LR, Paiva de Lucena RF, Paulino de Albuquerque U. Knowledge and use of medicinal plants by local specialists in a region of Atlantic Forest in the state of Pernambuco (Northeastern Brazil). J Ethnobiol Ethnomed. 2005; 1(1):9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 9.Saha D, Sundriyal M, Sundriyal RC. Diversity of food composition and nutritive analysis of edible wild plants in multi-ethnic tribal land, Northeast India: an important facet for food supply. Indian Journal of Traditional Knowledge. 2014;13(4):698–705. [Google Scholar]

- 10.Kala CP. Status and conservation of rare and endangered medicinal plants in the Indian trans-Himalaya. Biol Conserv. 2000;93:371–379. [Google Scholar]

- 11.Bisht VK, Kandari LS, Negi JS, Bhandari AK, Sundriyal RC. Traditional use of medicinal plants in district Chamoli, Uttarakhand. India. Jour Med Pl Res. 2013;7(15):918–929. [Google Scholar]

- 12.Kala CP. Current status of medicinal plants used by traditional Vaidyas in Uttaranchal State of India. Ethnobotany Research Applications. 2005;3:267–278. [Google Scholar]

- 13.Osmaston AE. A forest flora for Kumaun. Dehradun, India: International Book Distributors; 1926. [Google Scholar]

- 14.Naithani BD. Flora of Chamoli. Botanical Survey of India, Vol. 1 and 2. Dehradun, India. 1985.

- 15.Kirtikar KR, Basu BD. Indian medicinal plants. Bishan Singh Mahendra Pal Singh, Dehradun. 1994;1994.

- 16.Gaur RD. Flora of the District Garhwal: North West Himalaya (with ethnobotanical notes) Srinagar, Garhwal: Transmedia; 1999. [Google Scholar]

- 17.Phillips O, Gentry AH, Reynel C, Wilkin P, Galvez DBC. Quantitative ethno-medicine and Amazonian conservation. Biodivers Conserv Biol. 1994;8:225–248. [Google Scholar]

- 18.Tardio J, Pardo-de-Santayana M. Cultural importance indices: a comparative analysis based on the useful wild plants of southern Cantabria (northern Spain) Econ Bot. 2008;62(1):24–39. [Google Scholar]

- 19.Pardo-de-Santayana M, Tardio J, Blanco E, Carvalho AM, Lastra JJ, San Miguel E, Morales R. Traditional knowledge of wild edible plants used in the northwest of the Iberian Peninsula (Spain and Portugal): a comparative study. J Ethnobiol Ethnomed. 2007;3:27. doi: 10.1186/1746-4269-3-27. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Trotter Robert T., Logan Michael H. Plants in Indigenous Medicine & Diet. 2019. Informant Consensus: A New Approach for Identifying Potentially Effective Medicinal Plants; pp. 91–112. [Google Scholar]

- 21.Gurdal B, Kultur S. An ethnobotanical study of medicinal plants in Marmaris (Mugla, Turkey) J Ethnopharmacol. 2013;146(1):113–126. doi: 10.1016/j.jep.2012.12.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Ahmad M, Sultana S, Fazl-i-Hadi S, Ben Hadda T, Rashid S, Zafar M, Khan MA, Khan MPZ, Yaseen G. An ethnobotanical study of medicinal plants in high mountainous region of Chail valley (district swat-Pakistan) J Ethnobiol Ethnomed. 2014;10(1):36. doi: 10.1186/1746-4269-10-36. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Tugume P, Kakudidi EK, Buyinza M, Namaalwa J, Kamatenesi M, Mucunguzi P, Kalema J. Ethnobotanical survey of medicinal plant species used by communities around Mabira Central Forest Reserve. Uganda. J EthnobiolEthnomed. 2016;12(1):5. doi: 10.1186/s13002-015-0077-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Umair M, Altaf M, Abbasi AM. An ethnobotanical survey of indigenous medicinal plants in Hafizabad district. Punjab-Pakistan. PloS one. 2017;12(6):e0177912. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0177912. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Farooq A, Amjad MS, Ahmad K, Altaf M, Umair M, Abbasi AM. Ethnomedicinal knowledge of the rural communities of Dhirkot, Azad Jammu and Kashmir. Pakistan. J Ethnobiol Ethnomed. 2019;15:45. doi: 10.1186/s13002-019-0323-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.El Amri J, El Badaoui K, Zair T, Bouharb H, Chakir S, Alaoui T. Ethnobotanical study of medicinal plants in the region El Hajeb (Central Morocco) J Res Biol. 2015;4(8):1568–1580. [Google Scholar]

- 27.Boudjelal A, Henchiri C, Sari M, Sarri D, Hendel N, Benkhaled A, Ruberto G. Herbalists and wild medicinal plants in M’Sila (North Algeria): an ethnopharmacology survey. J Ethnopharmacol. 2013;148(2):395–402. doi: 10.1016/j.jep.2013.03.082. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Singh H. Importance of local names of some useful plants in ethnobotanical study. Indian J Tradit Knowledge. 2008;7(2):365–370. [Google Scholar]

- 29.Shandesh B, Chaudhary RP, Quave CL, Taylor RSL. The use of medicinal plants in the transhimalayan arid zone of Mustang district. Nepal. J Ethnobiol Ethnomed. 2010;6:14. doi: 10.1186/1746-4269-6-14. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Kumar M, Mehraj A, Sheikh MA, Bussmann RW. Ethnomedicinal and ecological status of plants in Garhwal Himalaya. India. J Ethnobiol Ethnomed. 2011;7:32. doi: 10.1186/1746-4269-7-32. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Malik ZA, Bhat JA, Ballabha A, Bussmann RW. Ethnomedicinal plants traditionally used in health care practices by inhabitants of Western Himalaya. J Ethnopharmacolog. 2015;172:133–144. doi: 10.1016/j.jep.2015.06.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Bhat JA, Kumar M, Bussmann RW. Ecological status and traditional knowledge of medicinal plants in Kedarnath Wildlife Sanctuary of Garhwal Himalaya. India. J. Ethnobiol Ethnomed. 2013;9:1. doi: 10.1186/1746-4269-9-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Kunwar RM, Nepal BK, Kshetri HB, Rai SK, Bussmann RW. Ethnomedicine in Himalaya: a case study from Dolpa, Humla. Jumla and Mustang districts of Nepal. J. Ethnobiol Ethnomed. 2006;2:27. doi: 10.1186/1746-4269-2-27. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Kunwar RM, Shrestha KP, Bussmann RW. Traditional herbal medicine in Far-west Nepal: a pharmacological appraisal. J. Ethnobiol Ethnomed. 2010;6:35. doi: 10.1186/1746-4269-6-35. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Kunwar RM, Mahat L, Acharya RP, Bussmann RW. Medicinal plants, traditional medicine, markets and management in far-west Nepal. J. Ethnobiol. Ethnomed. 2013;9:24. doi: 10.1186/1746-4269-9-24. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Moore PD. Trials in bad taste. Nature. 1994;370:410–411. [Google Scholar]

- 37.Keter LK, Mutiso PC. Ethnobotanical studies of medicinal plants used by traditional health practitioners in the management of diabetes in lower eastern province. Kenya. J. Ethnopharmacol. 2012;139:74–80. doi: 10.1016/j.jep.2011.10.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Quave CL, Pieroni AA. Reservoir of ethnobotanical knowledge informs resilient foodsecurity and health strategies in the Balkans. Nature Plants. 2015;1(2):14021. doi: 10.1038/nplants.2014.21. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Mahmood A, Mahmood A, Malik RN, Shinwari ZK. Indigenous knowledge of medicinal plants from Gujranwala district. Pakistan. J Ethnopharmacol. 2013;148(2):714–723. doi: 10.1016/j.jep.2013.05.035. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Bano A, Ahmad M, Hadda TB, Saboor A, Sultana S, Zafar M, Khan MPZ, Arshad M, Ashraf MA. Quantitative ethnomedicinal study of plants used in the skardu valley at high altitude of Karakoram-Himalayan range. Pakistan. J Ethnobiol Ethnomed. 2014;10(1):43. doi: 10.1186/1746-4269-10-43. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Bisht VK, Rana CS, Negi JS, Bhandari AK, Purohit V, Kuniyal CP, Sundriyal RC. Lamiaceous ethno-medico-botanicals in Uttarakhand Himalaya. India. Jour Med Pl Res. 2012;6(26):4281–4291. [Google Scholar]

- 42.Sundriyal RC. Medicinal plant cultivation and conservation in the Himalaya: an agenda for action. Indian Forester. 2005;131(3):410–424. [Google Scholar]

- 43.Singh P, Attri BL. Survey on traditional uses of medicinal plants of Bageshwar valley (Kumaun Himalaya) of Uttarakhand. India. Intern J Conserv Sci. 2014;5(2):223–234. [Google Scholar]

- 44.Tewari S, Paliwal AK, Joshi B. Medicinal use of some common plants among people of Garur Block of District Bageshwar, Uttarakhand. India. Octa J Biosci. 2014;2(1):32–35. [Google Scholar]

- 45.Bhatt D, Arya D, Chopra N, Upreti BM, Joshi GC, Tewari LM. Diversity of ethnomedicinal plant: a case study of Bageshwar district Uttarakhand. Journal of Medicinal Plants Studies. 2017;5(2):11–24. [Google Scholar]