Abstract

Cases of the 2019 novel coronavirus also known as severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2 (SARS-CoV-2) continue to rise worldwide. To date, there is no effective treatment. Clinical management is largely symptomatic, with organ support in intensive care for critically ill patients. The first phase I trial to test the efficacy of a vaccine has recently begun, but in the meantime there is an urgent need to decrease the morbidity and mortality of severe cases. It is known that patients with cancer are more susceptible to infection than individuals without cancer because of their systemic immunosuppressive state caused by the malignancy and anticancer treatments. Therefore, these patients might be at increased risk of pulmonary complications from COVID-19. The SARS-CoV-2 could in some case induce excessive and aberrant non-effective host immune responses that are associated with potentially fatal severe lung injury and patients can develop acute respiratory distress syndrome (ARDS). Cytokine release syndrome and viral ARDS result from uncontrolled severe acute inflammation. Acute lung injury results from inflammatory monocyte and macrophage activation in the pulmonary luminal epithelium which lead to a release of proinflammatory cytokines including interleukin (IL)-6, IL-1 and tumor necrosis factor-α. These cytokines play a crucial role in immune-related pneumonitis, and could represent a promising target when the infiltration is T cell predominant or there are indirect signs of high IL-6-related inflammation, such as elevated C-reactive protein. A monoclonal anti-IL-6 receptor antibody, tocilizumab has been administered in a number of cases in China and Italy. Positive clinical and radiological outcomes have been reported. These early findings have led to an ongoing randomized controlled clinical trial in China and Italy. While data from those trials are eagerly awaited, patients’ management will continue to rely for the vast majority on local guidelines. Among many other aspects, this crisis has proven that different specialists must join forces to deliver the best possible care to patients.

Keywords: lung neoplasms, T-Lymphocytes, immunity

New cases of the 2019 novel coronavirus also known as severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2 (SARS-CoV-2) continue to rise worldwide. On March 11th, 2020, the WHO declared a pandemic, with 118,326 confirmed cases and 4292 deaths reported1 with a mortality rate of 3.6%2 whereas the mortality for critical cases can reach 60.5%.3 To date, there is no effective treatment. Clinical management is largely symptomatic, with organ support in intensive care for critically ill patients. The unprecedented flurry of activity by the WHO and other global public health bodies has mainly focused on preventing transmission, through infection control measures, including screening of travelers. The development of vaccines has received immediate support and the first phase I trial has just begun (NCT04283461). However, there is an urgent need to focus funding and scientific investments into advancing novel therapeutic interventions for coronavirus infections, to decrease the morbidity and mortality of severe cases. The results of the first randomized trial assessing antivirals (lopinavir and ritonavir) failed to show any clinical benefit.4

The China International Exchange and Promotive Association for Medical and Healthcare (CPAM)5 has issued guidelines about the potential treatment of coronavirus virus disease 2019 (COVID-19) which include antiviral and immune-modulating drugs such as chloroquine. Nevertheless none of them has proven to be effective thus far and combination trials are ongoing (NCT04319900).

It is known that patients with cancer are more susceptible to infection than individuals without cancer because of their systemic immunosuppressive state caused by the malignancy and anticancer treatments. Therefore, these patients, and in particular lung cancer patients, might be at increased risk of pulmonary complications from COVID-19.

Risk of COVID-19 in cancer patients

Severe COVID-19 can be considered a hyperinflammatory disorder characterized by massive immune cell activation. As such, this may explain worse outcomes in older people and cancer patients. While it could be hypothesized that the lowered immunity induced by cancer itself or its treatment could be a protective element against the major immune reaction seen in COVID-19, there is a biological rationale dispelling this postulate. An increase in inflammation is common during aging and has been defined ‘inflamm-aging’.6 Chronic inflammation, including from cancer and age, as well as immune checkpoint inhibitors (ICIs) can cause a surge in proinflammatory immune responses, leading to enhanced production of cytokines from T cells and phagocytes. In lung cancer in particular, there is chronic pulmonary inflammation, both from the tumor microenvironment and the frequent underlying lung pathology.7 This immune deregulation observed in older, lung cancer, or ICI-treated patients may drive the severe pathogenesis of COVID-19 in these special populations.

Additionally, T cells produce proinflammatory cytokines with multiple functions, such as recruiting monocytes and neutrophils to the site of infection and activating other downstream cytokine and chemokine cascades.8–10

Recently Liang et al 11 showed an over-representation of cancer patients in the COVID-19 cohort. Therein, lung cancer was the most frequent type (5 (28%) of 18 patients). Based on their results, the authors have proposed three major strategies for patients with cancer in this COVID-19 crisis: (1) To postpone all adjuvant systemic therapy or elective surgery for stable cancer in endemic areas. (2) To increase personal protection provisions for patients with cancer and at-risk cancer survivors. (3) To intensify surveillance in cancer patients infected with SARS-CoV-2. Although these recommendations came from a small sample size with a large amount of heterogeneity, there is an increasing consensus to modify our standard management during this pandemic. Patients with lung cancer are prone to severe complications, such as admission to the intensive care unit requiring invasive ventilation, or death, from COVID-19. Smoking has also been identified as an independent risk factor in severe COVID-19 cases.12

Yu et al 13 published a retrospective analysis about 1524 patients with cancer who were admitted to the Department of Radiation and Medical Oncology, Zhongnan Hospital of Wuhan University. They reported the outcomes of COVID-19 among those patients. The study highlighted that patients with cancer harbored a higher risk of SARS-CoV-2 infection (OR, 2.31; 95% CI, 1.89 to 3.02) compared to the general population. This risk appears increased in both patients with or without active anticancer treatments. The most likely to develop COVID-19 were patients with non-small cell lung cancer (NSCLC) and above the age of 60.

Furthermore, the Lung Cancer Study Group, Chinese Thoracic Society, Chinese Medical Association and the Chinese Respiratory Oncology Collaboration have issued recommendations about the management of patients with advanced NSCLC during the COVID-19 epidemic.14 (1) Whenever possible, patients with advanced NSCLC should be treated as outpatients at the nearest medical center. (2) Patients who need to be hospitalized for antitumor treatment should be tested beforehand for COVID-19 infection. (3) Close attention should be paid to identification of COVID-19-related symptoms and adverse reactions caused by the malignancy or antitumor treatments. (4) Stringent personal protection protocols should be applied to advanced NSCLC patients. (5) An intentional postponing of antitumor treatment should be considered according to patient performance status. (6) Treatment strategies should be tailored to the type of NSCLC, the patient, and efficacy and expected toxicity of each drug. Recently Ruan et al showed that, among patients who died from COVID-19, 63% had underlying disease, whereas 41% of those discharged did.15 An early report of a subset of patients who died from COVID-19 in Italy found that 20.3% of the deceased had active cancer.16 All of this underlines the increased risk for cancer patients, particularly lung cancer patients.

Immunopathophysiology of SARS-CoV-2 lung injury

Biopsies, lobectomies and autopsies have yielded data about the histologic reflection of the pathophysiology of COVID-19. A particularly interesting report concerns two patients with lung cancer treated with lobectomy, retrospectively diagnosed with COVID-19, offering a glimpse into the early pathologic presentation of this disease.17 As in the original SARS disease, COVID-19 can induce exudative as well as proliferative lung injury in the acute setting. Today, we know that the main histological findings in COVID-19 lung lesions are typical signs of alveolar damage, including the triad of injury to alveolar epithelial cells, type II pneumocyte hyperplasia and hyaline membrane formation.18 The hallmark hyaline membrane formation seen in SARS and observed in subsequent pathologic analyzes of COVID-19 were lacking, shedding light on the chronology acute lung injury. In this case, this constellation was likely because these patients were operated at a presymptomatic stage. A notable observation was an abundant infiltration of alveolar macrophages and mononuclear inflammatory cells. Interestingly, the authors point out that while clinically asymptomatic, these patients did present leukocytosis with lymphopenia, suggesting the immune response was underway at this early disease stage.17 Similarly, radiographic changes can precede symptoms and must be interpreted cautiously during an epidemic.

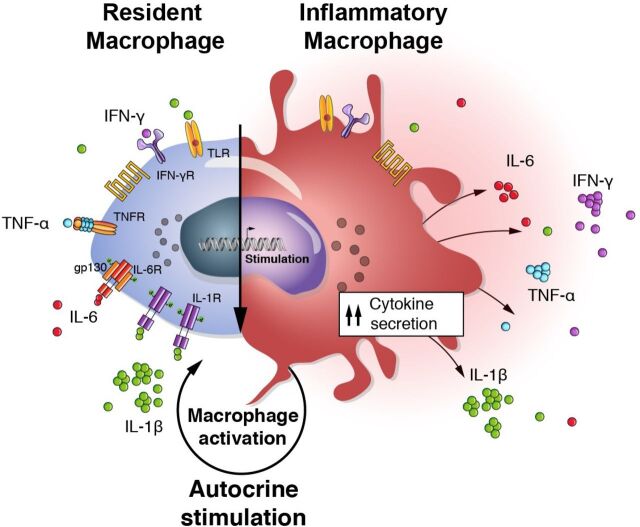

The pathophysiology of the COVID-19 is not yet completely elucidated. However, in some cases, the SARS-CoV-2 induces excessive and aberrant non-effective host immune responses that are associated with potentially fatal severe lung injury.19 The novel coronavirus might mainly act on lymphocytes, especially T lymphocytes.19 Patients can develop acute respiratory distress syndrome (ARDS) with characteristic pulmonary ground glass changes on imaging (figure 1). In some severe cases, this infection can be associated with a cytokine storm and macrophage activation syndrome (MAS), characterized by increased plasma concentrations of interleukin (IL)-2, IL-7, and IL-10, granulocyte-colony stimulating factor, interferon-γ-inducible protein, monocyte chemoattractant protein, macrophage inflammatory protein and tumor necrosis factor (TNF)-α.20 The dominant feature of MAS is the over-activation of tissue macrophages for the release of a storm of cytokines leading to rapidly progressing organ dysfunction where pancytopenia, tissue hemophagocytosis, hepatobiliary dysfunction, disseminated intravascular coagulation, and dysfunction of the central nervous system predominate. MAS can be fatal. The hallmark of pathogenesis is the overproduction of IL-1β by tissues macrophages. IL-1β acts through autocrine stimulation of macrophages leading to a vicious cycle of further cytokine production and exaggerated inflammation. Moreover, IL-1 signaling drives the acute phase response to infection,21 the Th17 differentiation22 and the immunopathogenic response observed in in ARDS and acute lung injury.23 Interestingly, a proinflammatory Th17 signature has been reported in patients infected with SARS-CoV-224 and with MERS-CoV.25 Elevated serum of interferon (IFN)-γ has been recently reported in patients with ARDS in COVID-19.26 27 Additionally, IFN-γ is pleiotropic cytokine and enhances IL-6 production in monocytes28 (figure 2). IFN- γ exerts its pleiotropic effects through the Janus kinase (JAK)1/JAK2 signaling leading to the activation of a large downstream cascade.29 Historically, IFN-γ has been implicated in the pathogenesis of ‘cytokine storm’ in various autoimmune diseases and also in hemophagocytic lymphohistiocytosis.23

Figure 1.

Chest CT showing typical ground glass opacities in acute respiratory distress syndrome, in this case in a lung cancer patient with COVID-19.

Figure 2.

Autocrine macrophage activation. The hallmark of pathogenesis of macrophage activation syndrome, as can be seen in COVID-19, is the overproduction of IL-1β by tissues macrophages. IL-1β, as well as other proinflammatory cytokines, acts through autocrine stimulation on macrophages leading to a vicious cycle of cytokine production and hyperinflammation. gp130, glycoprotein 130; IFN, interferon; IL, interleukin; R, receptor; TLR, toll-like receptor; TNF, tumor necrosis factor.

In a small fraction of septic patients, proinflammatory phenomena predominate and a more specific treatment might be associated with better outcomes.30

IL-6 blockade is frequently administered to patients with cancer in the context of immune checkpoint-inhibitor-induced immune-related adverse events, particularly in steroid resistant ones,31 as well as to dampen cytokine-release syndrome which can complicate chimeric antigen receptor T cell (CAR-T) therapy.32 ICI-related pneumonitis and SARS-CoV-2 induced ARDS have overlapping features, sharing a clinical and radiological presentation. ICI-induced pneumonitis, cytokine release syndrome and viral ARDS result from uncontrolled severe acute inflammation. Acute lung injury results from inflammatory monocyte and macrophage activation in the pulmonary luminal epithelium which lead to a release of proinflammatory cytokines including IL-6, IL-1 and TNF-α.33

In addition to acute inflammation, IL-6 stimulates T cell proliferation and it has a critical role: it exerts a negative impact on the ability of pulmonary dendritic cells to prime naive T cells, thus downplaying the adaptive immune response.33 Corticosteroids are standard frontline therapy for ICI-induced pneumonitis34 and they have been tested in SARS-CoV-2 induced ARDS in order to suppress the cytokine storm. Their use remains controversial as they do not prolong survival.35 36 IL-1 blockade has been assessed data from a phase III randomized controlled trial of the anti-IL-1 monoclonal antibody, anakinra, in septic patients with features of MAS, showed significant survival benefit, without increased adverse events.37 Ongoing trials of cellular therapies for treatment of ARDS could be expanded to treatment of critically ill patients with SARS-CoV-2 infection. Cellular therapy using mesenchymal stromal cells from allogeneic donors is being evaluated in patients with ARDS, as it reduces non-productive inflammation and affects tissue regeneration (NCT02804945; NCT03608592).

Future therapeutic directions

While the pathophysiology is multifaceted, IL-6 seems to play an important role in immune-related pneumonitis, and could represent a possible target if there are indirect signs of high IL-6-related inflammation, such as elevated C-reactive protein. Among cancer patients who developed ICI-induced pneumonitis with signs of high inflammation in blood tests, 79.4% responded well to the monoclonal anti-IL-6 receptor antibody, tocilizumab (TCZ) within 7 days.38 It has been administered in a number of cases in China and Italy. As recently published in a statement from the Society for Immunotherapy of Cancer (SITC) on IL-6 therapies for COVID-19, the authors reported rapid improved clinical, biological and radiological outcomes, as soon as 5 days after TCZ treatment. This has led to compassionate use of TCZ in several countries and the SITC statement recommends all efforts be made to allow for emergency approval of this drug.39 Furthermore, a single center experience reported that TCZ appears to be an effective treatment option in COVID‐19 patients with a risk of cytokine storm. However the result should be evaluated with caution given the combination with methylprednisolone and the small number of cases and the treatment duration.

Controlled clinical trial are ongoing in China and Italy aiming to confirm the safety and efficacy of TCZ in COVID-19 (ChiCTR2000029765 and TOCIVID-19) and the Food and Drug Administration (FDA) has approved a phase III, placebo-controlled, randomized clinical trial of TCZ (COVACTA).

The hypercytokinemia in COVID-19 may be addressed as a result and driver of immune cell activation. The over-activation of T cells and macrophages excessively produce proinflammatory cytokines, mainly IL-6, IL-1β and IFN-γ. One important pathophysiological mechanism is that macrophages use the Janus kinase-signal transducer and activator of transcription proteins (JAK-STAT) system.40

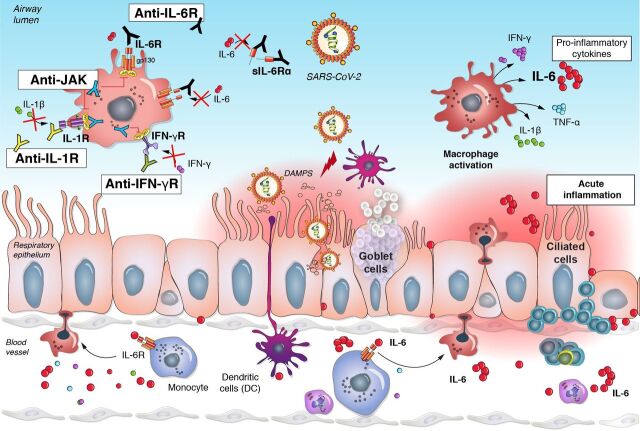

Other immune-modulating therapies are potential candidates. Agents able to alleviate activation of JAK1/JAK2 using ruxolitinib, of IL-6/IL-6R signaling (using TCZ or an anti-IL-6 antibody such as siltuximab), of IL-1 signaling (using anakinra which is a recombinant human IL-1R antagonist or using canakinumab that is a human monoclonal anti-IL-1β antibody) or anti-IFN-γ (using emapalumab that is a human anti-IFN-γ monoclonal antibody) are promising therapeutic strategies to treat the hypercytokinemia syndrome associated with severe forms of COVID-19 (figure 3).

Figure 3.

Acute inflammation in COVID-19 and treatment strategies. In response to the viral infection, inflammatory monocyte and macrophage activation in the pulmonary luminal epithelium leads to a massive release of proinflammatory cytokines including IL-6, IL-1 and TNF-α (the different treatment strategy should be highlighted). These are potential targets currently under investigation. DAMPS, damage-associated molecular patterns; gp130, glycoprotein 130; IFN, interferon;IL, interleukin; JAK, Janus kinase; R, receptor; sIL-6R, soluble IL-6 receptor;TNF, tumor necrosis factor.

Several non-immune-modulating therapies are being been explored. Chloroquine and hydroxychloroquine are antimalarial drugs which have shown antiviral effects against many types of viruses, in vitro, including in HIV. They rely on two identified mechanisms of action: inhibiting low pH-dependent viral entry into host cells and altering post-translational modifications of newly synthesized proteins by blocking glycosylation.41

Combining chloroquine with the antiviral, remdesivir, inhibits the growth of SARS-CoV-2 in vitro42 and early trials in China suggest a beneficial effect of chloroquine in terms of biological (viral load) and clinical outcomes.43 While trials are ongoing, consensus guidelines recommend its use in China.14

Hydroxychloroquine, which has a more favorable toxicity profile than chloroquine, has been shown to be more potent than chloroquine to inhibit SARS-CoV-2 in vitro.44 The former’s potential role is corroborated by its efficacy in clearing nasopharyngeal carriage of SARS-CoV-2, reducing the mean duration of shedding from 20 days to 3 to 6 days.36

Furthermore, associating hydroxychloroquine with the immunomodulatory macrolide, azithromycin, appears to increase the virological cure rate, with 100% of patients receiving this combination virus-free after 6 days, compared with 57% with hydroxychloroquine alone and 12% in the control group without either treatment (p<0.001).45 However, no strong evidence supports clinical efficacy of any of these molecules in COVID-19 and randomized trials are needed.

Current antiviral studies are ongoing. Remdesivir, a nucleotide analog inhibitor of the Ebola virus (EBOV) RNA-polymerase RNA-dependent, with promising in vitro anti-SARS-CoV-2 efficacy42 and reports from early clinical data. The AIDS-approved combination of lopinavir and ritonavir had also been adopted as a therapeutic option for COVID-19, but a randomized trial of 199 patients showed no clinical benefit, reinforcing that early data should be interpreted cautiously.4

Prevention of COVID-19 in lung cancer patients

Today, various recommendations have emerged about tailoring cancer therapies, including for NSCLC, to the reality of the COVID-19.46 The backbone of all of these is to reduce unnecessary exposure, thus reducing the risk of transmission. For lung cancer patients, this also means carefully weighing the risk-benefit ratio of each treatment. While ICI-induced pneumonitis may resemble COVID-19, both on a pathophysiological and clinical level, there is no evidence suggesting patients receiving these treatments are at increased risk of severe COVID-19 complications, compared with those on other oncological therapies. Similarly, no data exist about potential interaction between tyrosine kinase inhibitors and SARS-CoV-2. Again, even if drug-induced pneumonitis is suspected, COVID-19 should be ruled out. For all NSCLC patients, the element to keep in mind; however, is to be reactive. While awaiting viral swab confirmation, one should interrupt cytotoxic therapy should biological, clinical or radiological tests be suggestive of COVID-19.

Conclusion

Several unique opportunities to evaluate a range of treatment interventions at the peak of the previous SARS-CoV outbreaks were missed due to avoidable delays and the subsequent decline in cases, leaving numerous questions about the coronavirus pathogenesis unanswered. Patients with cancer, particularly lung cancer, are at higher risk to develop severe complications if infected by SARS-CoV-2, hence important measures must be considered to minimize this risk.

As the SARS-CoV-2 continues to spread, and the death-toll to rise exponentially, advancing new therapeutic development becomes crucial, both to limit the number of deaths in general population and patients suffering from cancer, and to alleviate the strain on healthcare systems worldwide, already struggling to cope with the number of victims of this disease.

Thus, the identification of predictive biomarkers associated to severe forms of COVID-19 is a ‘conditio sine qua non’ to develop personalized care. A better understanding of the exact role of immune deregulation in COVID-19 will facilitate the development and selection of targeted treatment while waiting for a vaccine. Targeted immunotherapy may represent a valid alternative to antivirals which have narrow therapeutic windows and early resistance mechanisms

While we await further data from the countries that have been most affected by COVID-19, patient management will rely partially on trials, where available, and for the vast majority on local guidelines. The TCZ story proves that, more than ever, in times of crisis specialists from different medical domains can join forces to offer the best possible care to patients.

Footnotes

Contributors: All the authors have equally contributed.

Funding: The authors have not declared a specific grant for this research from any funding agency in the public, commercial or not-for-profit sectors.

Competing interests: AA: has received compensation from Bristol-Myers Squibb, AstraZeneca, Merck Sharp & Dohme, Takeda, Pfizer, Roche and Boehringer Ingelheim for participating on advisory boards. AF: has received compensation from Roche, Pfizer, Astellas and Bristol-Myers Squibb for service as a consultant.

Patient consent for publication: Not required.

Provenance and peer review: Not commissioned; externally peer reviewed.

References

- 1. WHO . Coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID19)-SITUATION REPORT 51 2019.

- 2. Baud D, Qi X, Nielsen-Saines K, et al. Real estimates of mortality following COVID-19 infection. Lancet Infect Dis 2020. 10.1016/S1473-3099(20)30195-X [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Yang X, Yu Y, Xu J, et al. Clinical course and outcomes of critically ill patients with SARS-CoV-2 pneumonia in Wuhan, China: a single-centered, retrospective, observational study. Lancet Respir Med 2020. 10.1016/S2213-2600(20)30079-5. [Epub ahead of print: 24 Feb 2020]. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Cao B, Wang Y, Wen D, et al. A trial of Lopinavir–Ritonavir in adults hospitalized with severe Covid-19. N Engl J Med 2020. 10.1056/NEJMoa2001282 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Jin Y-H, Cai L, Cheng Z-S, et al. A rapid advice guideline for the diagnosis and treatment of 2019 novel coronavirus (2019-nCoV) infected pneumonia (standard version). Mil Med Res 2020;7:4. 10.1186/s40779-020-0233-6 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Franceschi C, Bonafè M, Valensin S, et al. Inflamm-aging. an evolutionary perspective on immunosenescence. Ann N Y Acad Sci 2000;908:244–54. 10.1111/j.1749-6632.2000.tb06651.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Ballaz S, Mulshine JL. The potential contributions of chronic inflammation to lung carcinogenesis. Clin Lung Cancer 2003;5:46–62. 10.3816/CLC.2003.n.021 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Cecere TE, Todd SM, Leroith T. Regulatory T cells in arterivirus and coronavirus infections: do they protect against disease or enhance it? Viruses 2012;4:833–46. 10.3390/v4050833 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Bunte K, Beikler T. Th17 cells and the IL-23/IL-17 axis in the pathogenesis of periodontitis and immune-mediated inflammatory diseases. Int J Mol Sci 2019;20:3394. 10.3390/ijms20143394 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Billiau AD, Roskams T, Van Damme-Lombaerts R, et al. Macrophage activation syndrome: characteristic findings on liver biopsy illustrating the key role of activated, IFN-gamma-producing lymphocytes and IL-6- and TNF-alpha-producing macrophages. Blood 2005;105:1648–51. 10.1182/blood-2004-08-2997 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Liang W, Guan W, Chen R, et al. Cancer patients in SARS-CoV-2 infection: a nationwide analysis in China. Lancet Oncol 2020;21:335–7. 10.1016/S1470-2045(20)30096-6 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Zhou F, Yu T, Du R, et al. Clinical course and risk factors for mortality of adult inpatients with COVID-19 in Wuhan, China: a retrospective cohort study. The Lancet 2020;395:1054–62. 10.1016/S0140-6736(20)30566-3 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Yu J, Ouyang W, Chua MLK, et al. SARS-CoV-2 transmission in patients with cancer at a tertiary care hospital in Wuhan, China. JAMA Oncology 2020. 10.1001/jamaoncol.2020.0980 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Lung Cancer Study Group, Chinese Thoracic Society, Chinese Medical Association, Chinese Respiratory Oncology Collaboration . [Expert recommendations on the management of patients with advanced non-small cell lung cancer during epidemic of COVID-19 (Trial version)]. Zhonghua Jie He He Hu Xi Za Zhi 2020;43:E031. 10.3760/cma.j.cn112147-20200221-00138 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Ruan Q, Yang K, Wang W, et al. Clinical predictors of mortality due to COVID-19 based on an analysis of data of 150 patients from Wuhan, China. Intensive Care Medicine 2020:1–3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Onder G, Rezza G, Brusaferro S. Case-Fatality rate and characteristics of patients dying in relation to COVID-19 in Italy. JAMA 2020. 10.1001/jama.2020.4683. [Epub ahead of print: 23 Mar 2020]. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Tian S, Hu W, Niu L, et al. Pulmonary pathology of early-phase 2019 novel coronavirus (COVID-19) pneumonia in two patients with lung cancer. J Thorac Oncol 2020;15:700–4. 10.1016/j.jtho.2020.02.010 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Tian S, Xiong Y, Liu H, et al. Pathological study of the 2019 novel coronavirus disease (COVID-19) through postmortem core biopsies. Mod Pathol 2020. 10.1038/s41379-020-0536-x. [Epub ahead of print: 14 Apr 2020]. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Qin C, Zhou L, Hu Z, et al. Dysregulation of immune response in patients with COVID-19 in Wuhan, China. Clin Infect Dis 2020. 10.1093/cid/ciaa248. [Epub ahead of print: 12 Mar 2020]. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Mehta P, McAuley DF, Brown M, et al. COVID-19: consider cytokine storm syndromes and immunosuppression. The Lancet 2020;395:1033–4. 10.1016/S0140-6736(20)30628-0 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Weber A, Wasiliew P, Kracht M. Interleukin-1 (IL-1) pathway. Science Signaling 2010;3:cm1-cm1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Santarlasci V, Cosmi L, Maggi L, et al. Il-1 and T helper immune responses. Front Immunol 2013;4:182. 10.3389/fimmu.2013.00182 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Tisoncik JR, Korth MJ, Simmons CP, et al. Into the eye of the cytokine storm. Microbiol Mol Biol Rev 2012;76:16–32. 10.1128/MMBR.05015-11 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Wu D, Yang XO. Th17 responses in cytokine storm of COVID-19: an emerging target of JAK2 inhibitor fedratinib. J Microbiol Immunol Infect 2020. 10.1016/j.jmii.2020.03.005. [Epub ahead of print: 11 Mar 2020]. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Mahallawi WH, Khabour OF, Zhang Q, et al. Mers-Cov infection in humans is associated with a pro-inflammatory Th1 and Th17 cytokine profile. Cytokine 2018;104:8–13. 10.1016/j.cyto.2018.01.025 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Chen G, Wu D, Guo W, et al. Clinical and immunological features of severe and moderate coronavirus disease 2019. J Clin Invest 2020;130:2620–9. 10.1172/JCI137244 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Zhou F, Yu T, Du R, et al. Clinical course and risk factors for mortality of adult inpatients with COVID-19 in Wuhan, China: a retrospective cohort study. Lancet 2020;395:1054–62. 10.1016/S0140-6736(20)30566-3 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Biondillo DE, Konicek SA, Iwamoto GK. Interferon-Gamma regulation of interleukin 6 in monocytic cells. Am J Physiol 1994;267:L564–8. 10.1152/ajplung.1994.267.5.L564 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Farrar MA, Schreiber RD. The molecular cell biology of interferon-gamma and its receptor. Annu Rev Immunol 1993;11:571–611. 10.1146/annurev.iy.11.040193.003035 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Karakike E, Giamarellos-Bourboulis EJ. Macrophage Activation-Like syndrome: a distinct entity leading to early death in sepsis. Front Immunol 2019;10:55. 10.3389/fimmu.2019.00055 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Martins F, Sykiotis GP, Maillard M, et al. New therapeutic perspectives to manage refractory immune checkpoint-related toxicities. Lancet Oncol 2019;20:e54–64. 10.1016/S1470-2045(18)30828-3 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Gardner RA, Ceppi F, Rivers J, et al. Preemptive mitigation of CD19 CAR T-cell cytokine release syndrome without attenuation of antileukemic efficacy. Blood 2019;134:2149–58. 10.1182/blood.2019001463 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Liu L, Wei Q, Lin Q, et al. Anti–spike IgG causes severe acute lung injury by skewing macrophage responses during acute SARS-CoV infection. JCI Insight 2019;4. 10.1172/jci.insight.123158 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Haanen JBAG, Carbonnel F, Robert C, et al. Management of toxicities from immunotherapy: ESMO clinical practice guidelines for diagnosis, treatment and follow-up. Ann Oncol 2017;28:iv119–42. 10.1093/annonc/mdx225 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Russell CD, Millar JE, Baillie JK. Clinical evidence does not support corticosteroid treatment for 2019-nCoV lung injury. The Lancet 2020;395:473–5. 10.1016/S0140-6736(20)30317-2 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Zhou W, Liu Y, Tian D, et al. Potential benefits of precise corticosteroids therapy for severe 2019-nCoV pneumonia. Signal Transduction and Targeted Therapy 2020;5:18. 10.1038/s41392-020-0127-9 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. Shakoory B, Carcillo JA, Chatham WW, et al. Interleukin-1 receptor blockade is associated with reduced mortality in sepsis patients with features of macrophage activation syndrome: reanalysis of a prior phase III trial. Crit Care Med 2016;44:275–81. 10.1097/CCM.0000000000001402 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38. Stroud CR, Hegde A, Cherry C, et al. Tocilizumab for the management of immune mediated adverse events secondary to PD-1 blockade. J Oncol Pharm Pract 2019;25:551–7. 10.1177/1078155217745144 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39. Ascierto P. SITC statement on anti-IL-6/IL-6R for COVID-19. JITC 2020. [Google Scholar]

- 40. O'Shea JJ, Holland SM, Staudt LM. Jaks and STATs in immunity, immunodeficiency, and cancer. N Engl J Med 2013;368:161–70. 10.1056/NEJMra1202117 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41. Rolain J-M, Colson P, Raoult D. Recycling of chloroquine and its hydroxyl analogue to face bacterial, fungal and viral infections in the 21st century. Int J Antimicrob Agents 2007;30:297–308. 10.1016/j.ijantimicag.2007.05.015 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42. Wang M, Cao R, Zhang L, et al. Remdesivir and chloroquine effectively inhibit the recently emerged novel coronavirus (2019-nCoV) in vitro. Cell Res 2020;30:269–71. 10.1038/s41422-020-0282-0 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43. Gao J, Tian Z, Yang X. Breakthrough: chloroquine phosphate has shown apparent efficacy in treatment of COVID-19 associated pneumonia in clinical studies. Biosci Trends 2020;14:72–3. 10.5582/bst.2020.01047 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44. Yao X, Ye F, Zhang M, et al. In vitro antiviral activity and projection of optimized dosing design of hydroxychloroquine for the treatment of severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2 (SARS-CoV-2). Clinical Infectious Diseases 2020;10. 10.1093/cid/ciaa237 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45. Gautret P, Lagier J-C, Parola P, et al. Hydroxychloroquine and azithromycin as a treatment of COVID-19: results of an open-label non-randomized clinical trial. Int J Antimicrob Agents 2020;105949:105949. 10.1016/j.ijantimicag.2020.105949 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46. Banna G, Curioni-Fontecedro A, Friedlaender A, et al. How we treat patients with lung cancer during the SARS-CoV-2 pandemic: primum non nocere. ESMO Open 2020;5:e000765. 10.1136/esmoopen-2020-000765 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]