Abstract

Educational attainment has been associated with drinking behaviors in observation studies. We performed Mendelian randomization analysis to determine whether educational attainment causally affected drinking behaviors, including amount of alcohol intakes (in total and various types), drinking frequency, and drinking with or without meals among 334 507 White British participants from the UK Biobank cohort. We found that genetically instrumented higher education (one additional year) was significantly related to higher total amount of alcohol intake (inverse variance weighted method (IVW): beta=0.44, 95% confidence interval (CI) 0.40 to 0.49, P=1.57E-93). The causal relations with total amount and frequency of alcohol drinking were more evident among women. In analyses of different types of alcohol, higher educational attainment showed the strongest causal relation with more consumption of red wine (IVW beta=0.34, 95% CI 0.32 to 0.36, P=2.65E-247), followed by white wine/champagne, in a gender-specific manner. An inverse association was found for beer/cider and spirits. In addition, we found that one additional year of educational attainment was causally related to higher drinking frequency (IVW beta=0.54, 95% CI 0.51 to 0.57, P=4.87E-230) and a higher likelihood to take alcohol with meals (IVW: odds ratio (OR)=3.10, 95% CI 2.93 to 3.29, P=0.00E+00). The results indicate causal relations of higher education with intake of more total alcohol especially red wine, and less beer/cider and spirits, more frequent drinking, and drinking with meals, suggesting the importance of improving drinking behaviors, especially among people with higher education.

Introduction

Worldwide, alcohol consumption is a leading cause of ill health and premature mortality [1]. In 2016, the harmful use of alcohol including intoxication resulted in some 3 million deaths (5.3% of all deaths) [2]. In contrast, studies suggested benefits of light-to-moderate alcohol consumption on Coronary Heart Disease (CHD) risk and blood pressure [3–5], and evidence has also shown that consumption of certain types of alcohol, such as red wine [6], may lower the risks of premature mortality and various diseases including cardiovascular disease and diabetes [7, 8]. However, more recent researches increasingly show no protective or adverse effect of light-to-moderate alcohol on health [1, 9–13] and the potential benefits of alcohol consumption are likely to be offset when overall health risks were considered [1]. According to the Dietary Guidelines for Americans (2015–2020), individuals who do not drink alcohol are not recommended to start drinking for any reason. On the other hand, drinking habits, especially the frequency of drinking and whether drinking with meals, have been related to health events [14, 15]. Given the amount of alcohol, more frequent drinking and drinking with meals showed beneficial associations with a lower BMI and post-prandial blood pressure [16].

Epidemiological studies suggest that individuals with higher educational attainment tend to consume more alcohol, compared to those with lower educational attainment, though other studies showed the opposite trend [17–22]. Further, a previous study provided evidence that educational attainment was associated with different types of alcohol intake, leading to different health consequences [23]. However, most of the prior evidence about education and alcohol consumption comes from observational studies, which might be biased by confounding and reverse causation. Few studies have assessed the causality between education and alcohol drinking behaviors.

Mendelian randomization (MR) uses genetic markers as instrumental variables of exposure instead of exposure itself to facilitate causal inference [24]. This method is less likely to be affected by confounding or reverse causality [25]. A recent genome-wide association study (GWAS) revealed more than 1000 independent genome-wide-significant genetic variants associated with educational attainment [26]. Thus, in the current study, we used these variants as instruments to test the hypothesis that education may causally influence drinking behaviors in 334 507 individuals from the UK Biobank cohort. Given a potential sex difference in the relation between educational attainment and alcohol consumption [27], we also tested the causal relationship in men and women separately.

Methods

Study design and participants

UK Biobank is a large prospective study comprising nearly 0.5 million participants aged 37 to 73 years old at recruitment. Participants with self-reported white British were included in the study. Participants who 1) had a genetic relatedness with others; 2) without information on alcohol intake, 3) without genetic data; or 4) without information on covariates were excluded. Thus, 334 507 individuals were included in MR analyses. The UK Biobank study was approved by the North West Multi-Centre Research Ethics Committee and the Biomedical Committee of the Tulane University (New Orleans, Louisiana) Institutional Review Board. All participants provided written informed consent before participating in the UK Biobank study.

Education measurement and variants

Summary-level data of estimates and standard errors of the SNPs associated with educational attainment were recorded from the Social Science Genetic Association Consortium (SSGAC) [26]. Educational attainment was obtained by the touchscreen questionnaire at baseline. Participants were asked “Which of the following qualifications do you have? (You can select more than one)”. Eight options were provided under this question. To calculate years of education by the education qualification, we first mapped the above options onto the International Standard Classification of Education (ISCED) category and then imputed the years of education equivalent for each of the categories according to the previous study’s algorithm [26] (SupplementaryTable 1).

Townsend deprivation index, an indicator for socioeconomic status on the basis of national census data was obtained immediately preceding participation in UK Biobank. For occupation, we coded job class from low to high using the UK Biobank job code variable: [Elementary Occupations (coded as 1), Process, Plant and Machine Operatives (coded as 2), Sales and Customer Service Occupations (coded as 3), Personal Service Occupations (coded as 4), Skilled Trades Occupations (coded as 5), Administrative and Secretarial Occupations (coded as 6), Associate Professional and Technical Occupations (coded as 7), Professional Occupations (coded as 8), Managers and Senior Officials (coded as 9)]. For income, a categorical income variable was obtained from questionnaire, representing annual household income of <£18 000 (coded as 1), £18 000 to £30 999 (coded as 2), £31 000 to £51 999 (coded as 3), £52 000 to £100 000 (coded as 4), and >£100 000 (coded as 5). A higher coded number indicated a higher occupation/income level.

Drinking phenotypes

Data were obtained from the touchscreen questionnaire at the baseline appointment. Participants were asked about their current drinking status (never, previous, current, prefer not to answer). Alcohol intake frequency [UK Biobank Field Identifier (FID): 1558] was reported as “never”, “special occasions only”, “1 to 3 times per month”, “once or twice a week”, “3 or 4 times a week”, and “daily or almost daily” and coded from 0 to 5. Average weekly alcohol consumption of a range of drink types [red wine (FID: 1568), white wine/champagne (FID: 1578), spirits (FID: 1598), beer/cider (FID: 1588), and fortified wine (FID: 1608)] were obtained from the questionnaire. From these measures, ethanol intake (g/week) was calculated by the amount of each type of drink multiplied by its standard drink size and reference alcohol content.

Genetic data

Single nucleotide polymorphisms (SNP) genotyping, imputation, and quality control of the genetic data were performed by the UK biobank team. The majority of the sample was genotyped using the Affymetrix UK Biobank Axiom array and the rest of the sample genotyped using the Affymetrix UK BiLEVE Axiom array. A combined panel of the UK10K and 1000 Genomes phase 3 reference panels were used for imputation. Detailed information was described previously (http://www.ukbiobank.ac.uk/scientists-3/genetic-data/). We included 1199 independent SNPs (clumping were performed by Lee et al [26]. SNPs within 500 kb away from the lead SNP and correlated with r2 > 0.1 were removed [26, 28]) that were strongly associated with educational attainment from thus far the latest and largest GWAS study [26]. All these SNPs were in Hardy-Weinberg equilibrium (HWE) P >1E-12 within the white British participants. Any palindromic SNPs with minor allele frequency above 0.42 was removed (Supplementary Table 2). The instruments selected from this study explained approximately 4.3% of the variance in education.

To evaluate the correlations of education genetic instruments with occupation and income, we develop a polygenic score (PGS) for educational attainment using the following formula: PGS=(β1 × SNP1 + β2 × SNP2 +⋯ + βn × SNPn)× (number of selected SNPs/sum of the β coefficients), where β was the regression coefficient associated with SNP which obtained from the previous GWAS [26]. The PGS ranges from 1090 to 1346, with each unit corresponding to one effect allele and a higher score indicating a higher genetic predisposition to higher educational attainment.

Sex differences assessment and sensitivity analyses

To test the hypothesis that the effects of educational attainment on alcohol intake patterns may differ in men and women, we then performed analyses separately in each sex to examine whether the effects of educational attainment on alcohol intake may differ in women and men. We compared the β values for women and men by using z score method: .

Given that smoking and socioeconomic status are factors that highly correlated with educational attainment and alcohol drinking, we performed stratified analyses to assess the influence of these factors. We measured the association between educational attainment and drinking behaviors in each level taken by the smoking status (nonsmokers and smoker), education (<16 years and ≥16 years) and income (<£31 000 and ≥£31 000). We further evaluate the role of socioeconomic status in the established association between educational attainment and drinking behaviors by adjusting variables such as income, occupation and Townsend score in the model individually. We also performed mediation analysis to estimate for the association of education on drinking behaviors explained by the socioeconomic status.

Statistical analyses

Linear regression was used to test the association between educational attainment related SNPs and alcohol intake frequency, amount of total and various types of alcohol intakes; logistic regression was used to test the association between educational attainment related SNPs and whether alcohol usually taken with meals. Amount of alcohol consumption was log (units+1) transformed. All these analyses included an adjustment for age, sex, year of birth (dummy variable), sex interacted with year of birth, and 10 genetic principal components (PCs).

An R package TwoSampleMR was used to conduct the two-sample Mendelian randomization [29]. Four complementary methods (inverse variance weighted method (IVW), mendelian randomization-Egger (MR-Egger) method, median method, and mode based estimation) with different assumptions were applied in this study [30]. A consistent effect across these methods indicate that the causal inference is less likely to be a false positive [31]. MR-Egger intercept [32] and Mendelian randomization pleiotropy residual sum and outlier (MR-PRESSO) [33] were used to test for the presence of horizontal pleiotropy. Simulation extrapolation (SIMEX) correction was applied in mendelian MR-Egger analysis when regression dilution I2 for educational attainment instrument was less than 90% [34]. Results were reported for each additional year of education attainment. The mediation analysis was performed through observational analysis using Tyler’s SAS macro because of the lack of genetic instruments for socioeconomic status [35, 36]. The proportion mediated was defined as the ratio of the natural indirect effect to the total effect [35].

Statistical analyses were performed using SAS version 9.4 (SAS Institute Inc, Cary, NC) and R version 3.3.3 (The R Foundation: The R Project for Statistical Computing. http://www.R-project.org/). Two-sided P < 0.05 was used as the significance level.

Results

Baseline characteristics of the UK Biobank participants are shown in Table 1 and Table 2. Of the 334 507 participants included in the MR analysis, 179 669 (53.7%) were women. The mean age ± SD was 56.9±8.0 years, and mean BMI ± SD was 27.4 ± 4.7 kg/m2. Participants with higher educational attainment tended to be younger, leaner, and drink more alcohol compared to those with lower educational attainment (all P <0.001). In addition, we found that one-unit increase in educational attainment PGS was associated with 0.014 increased job class and 0.007 increased income level (All P<0.001). One year increase in education was associated with 0.17 increased occupation level and 0.07 increased income level (All P<0.001).

Table 1.

Baseline character of UK biobank participants included in the mendelian randomization analysis

| All | Women | Men | |

|---|---|---|---|

| N | 334 507 | 179 669 | 154 838 |

| Age, years | 56.9±8.0 | 56.7±7.9 | 57.1±8.1 |

| Education years | 14.9±5.1 | 14.5±5.1 | 15.3±5.1 |

| BMI, kg/cm2 | 27.4±4.7 | 27.0±5.1 | 27.8±4.2 |

| Total amount of alcohol intake, g/week | 120.5±144.9 | 76.5±92.4 | 171.6±174.9 |

| Red wine, glasses* | 4.0±5.6 | 3.4±4.7 | 4.5±6.3 |

| White wine/champagne, glasses** | 2.7±4.7 | 3.4±4.9 | 2.0±4.4 |

| Fortified, glasses† | 0.2±1.3 | 0.3±1.3 | 0.2±1.3 |

| Beer/cider, pints | 3.0±5.5 | 0.6±1.8 | 5.2±6.8 |

| Spirits, measures‡ | 1.8±5.3 | 1.5±4.0 | 2.2±6.2 |

| Alcohol inatke frequency, n (%) | |||

| Daily or almost daily | 71 746 (21.5) | 30 699 (17.1) | 41 047 (26.5) |

| Three or four times a week | 80 896 (24.2) | 38 920 (21.7) | 41 976 (27.1) |

| Once or twice a week | 87 995 (26.3) | 47 374 (26.4) | 40 621 (26.3) |

| One to three times a month | 37 039 (11.1) | 23 514 (13.1) | 13 525 (8.7) |

| Special occasions only | 34 977 (10.5) | 24 918 (13.9) | 10 059 (6.5) |

| Never | 21 649 (6.5) | 14 133 (7.9) | 7 516 (4.9) |

| Alcohol taken with meals | 116 172 (67.9) | 68 226 (77.0) | 47 946 (58.1) |

| Smoking, n (%) | |||

| Never | 182 914 (54.7) | 106 878 (59.5) | 76 036 (49.1) |

| Previous | 117 894 (35.2) | 57 333 (31.9) | 60 561 (39.1) |

| Current | 33 699 (10.1) | 15 458 (8.6) | 18 241 (11.8) |

| Townsend deprivation index§ | −1.6±2.9 | −1.6±2.9 | −1.5±3.0 |

| Job class, n (%) | |||

| Managers and Senior Officials | 35 820 (17.4) | 13 148 (12.4) | 22 672 (22.8) |

| Professional | 48 765 (23.7) | 23 446 (22.1) | 25 319 (25.4) |

| Associate Professional and Technical | 34 488 (16.8) | 19 713 (18.6) | 14 775 (14.8) |

| Administrative and Secretarial | 32 909 (16) | 26 645 (25.1) | 6 264 (6.3) |

| Skilled Trades | 15 589 (7.6) | 1 780 (1.7) | 13 809 (13.9) |

| Personal Service | 11 922 (5.8) | 9 985 (9.4) | 1 937 (1.9) |

| Sales and Customer Service | 7 172 (3.5) | 5 524 (5.2) | 1 648 (1.7) |

| Process, Plant and Machine Operatives | 9 208 (4.5) | 1 117 (1.1) | 8 091 (8.1) |

| Elementary | 9 749 (4.7) | 4 674 (4.4) | 5 075 (5.1) |

| Income, n (%) | |||

| <£18 000 | 62 615 (21.7) | 35 613 (23.9) | 27 002 (19.4) |

| £18 000 to £30 999 | 74 112 (25.7) | 39 712 (26.6) | 34 400 (24.7) |

| £31 000 to £51 999 | 76 439 (26.5) | 38 363 (25.7) | 38 076 (27.4) |

| £52 000 to £100 000 | 59 836 (20.7) | 28 444 (19.1) | 31 392 (22.6) |

| >£100 000 | 15 507 (5.4) | 7 151 (4.8) | 8 356 (6.0) |

6 glasses in an average bottle

12 glasses in an average bottle

25 standard measures in a normal size bottle; spirits include drinks such as whisky, gin, rum, vodka, brandy.

Negative values will indicate relative affluence

Table 2.

Baseline characteristics according to tertile of years of education in the observational studies

| Tertile 1 (7 years) | Tertile 2 (10–15 years) | Tertile 3 (19–20 years) | P | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| N | 58 077 | 119 831 | 162 597 | |

| Age, years | 61.4±6.1 | 56.7±8.0 | 55.3±8.0 | <0.001 |

| Sex, female | 31 530 (54.3) | 73 229 (61.1) | 79 005 (48.6) | <0.001 |

| BMI, kg/cm2 | 28.4±4.9 | 27.4±4.8 | 27.0±4.6 | <0.001 |

| Total amount of alcohol intake, g/week | 109.5±155.3 | 115.6±144.7 | 128.0±140.6 | <0.001 |

| Red wine, glasses* | 2.7±4.8 | 3.8±5.6 | 4.4±5.8 | <0.001 |

| White wine/champagne, glasses* | 1.9±4.1 | 2.8±4.8 | 2.9±4.8 | <0.001 |

| Fortified, glasses† | 0.3±1.6 | 0.2±1.3 | 0.2±1.2 | <0.001 |

| Beer/cider, pints | 4.4±7.0 | 2.8±5.5 | 2.7±4.9 | <0.001 |

| Spirits, measures‡ | 2.7±7.0 | 1.9±5.3 | 1.6±4.6 | <0.001 |

| Alcohol intake frequency, n (%) | <0.001 | |||

| Daily or almost daily | 8 910 (15.4) | 24 306 (20.3) | 40 023 (24.6) | |

| Three or four times a week | 10 669 (18.4) | 27 943 (23.3) | 43 782 (26.9) | |

| Once or twice a week | 16 433 (28.3) | 32 158 (26.9) | 40 811 (25.1) | |

| One to three times a month | 6 614 (11.4) | 14 491 (12.1) | 16 607 (10.2) | |

| Special occasions only | 9 081 (15.7) | 13 194 (11.0) | 13 272 (8.2) | |

| Never | 6 300 (10.9) | 7 687 (6.4) | 8 025 (4.9) | |

| Alcohol taken with meals, n (%) | 13 710 (48.6) | 41 017 (68.2) | 63 912 (74.2) | <0.001 |

| Smoking, n (%) | <0.001 | |||

| Never | 25 265 (43.8) | 65 962 (55.2) | 94 502 (58.2) | |

| Previous | 24 035 (41.7) | 41 650 (34.8) | 53 956 (33.3) | |

| Current | 8 332 (14.5) | 11 937 (10.0) | 13 792 (8.5) | |

| Townsend deprivation index§ | −0.6±3.3 | −1.8±2.8 | −1.8±2.8 | <0.001 |

| Job class, n (%) | <0.001 | |||

| Managers and Senior Officials | 2 608 (10.7) | 12 548 (17.2) | 21 501 (19.1) | |

| Professional | 452 (1.9) | 7 959 (10.9) | 41 638 (36.9) | |

| Associate Professional and Technical | 1 445 (5.9) | 14 715 (20.2) | 19 218 (17) | |

| Administrative and Secretarial | 4 283 (17.6) | 18 720 (25.7) | 10 894 (9.7) | |

| Skilled Trades | 3 770 (15.5) | 4 958 (6.8) | 6 999 (6.2) | |

| Personal Service | 1 981 (8.1) | 4 338 (6.0) | 5 799 (5.1) | |

| Sales and Customer Service | 2 385 (9.8) | 3 173 (4.4) | 1 737 (1.5) | |

| Process, Plant and Machine Operatives | 3 312 (13.6) | 3 108 (4.3) | 2 847 (2.5) | |

| Elementary | 4 120 (16.9) | 3 391 (4.7) | 2 235 (2.0) | |

| Income, n (%) | <0.001 | |||

| <£18 000 | 23 383 (53.4) | 22 078 (21.5) | 18 654 (12.5) | |

| £18 000 to £30 999 | 12 480 (28.5) | 30 688 (29.8) | 32 657 (21.9) | |

| £31 000 to £51 999 | 5 827 (13.3) | 29 073 (28.3) | 43 491 (29.2) | |

| £52 000 to £100 000 | 1 834 (4.2) | 17 782 (17.3) | 41 740 (28.0) | |

| >£100 000 | 288 (0.7) | 3286 (3.2) | 12 298 (8.3) |

6 glasses in an average bottle

12 glasses in an average bottle

25 standard measures in a normal size bottle; spirits include drinks such as whisky, gin, rum, vodka, and brandy

Negative values will indicate relative affluence

Amount of total and various types of alcohol intakes

There was consistent evidence for an association between educational attainment (one additional year) and amount of alcohol intake (Figure 1A, IVW beta=0.44, 95% confidence interval (CI) 0.40 to 0.49, P=1.57E-93). Such relations appeared to be more evident among women (Figure 1A, IVW beta=0.59, 95% CI 0.54 to 0.64, P=7.80E-109). No evidence of pleiotropy was found according to the intercept of MR-Egger for the pooled participants (Supplementary Table 3, Pintercept=0.92). However, for women, slight pleiotropy was observed (Pintercept=0.05) (Supplementary Table 3). After removing outliers by using MR-PRESSO, no significant change of the association was found after correction for the detected horizontal pleiotropy (P=0.94). For men, though the IVW method and weighted median method showed a positive association, the results were not consistent for mode-based method (Figure 1A).

Figure 1.

Associations of educational attainment and amount of total and specific alcohol intake from Mendelian Randomization (MR) analyses. Panel A, the total amount of alcohol intake; panel B, red wine; panel C, white wine/champagne; panel D, fortified wine; panel E, beer/cider; panel F, spirits.

For various types of alcohol intake, we found consistent evidence between educational attainment and red wine and white wine/champagne intake in both women and men: one additional year of educational attainment was associated with more red wine intake (Figure 1B. IVW beta=0.34, 95% CI 0.32 to 0.36, P=2.65E-247) and white wine/champagne (Figure 1C. IVW beta=0.24, 95% CI 0.22 to 0.26, P=5.58E-160). The direction was consistent when using the median and mode-based method. No evidence of pleiotropy was found according to the intercept of MR-Egger (for red wine Pintercept=0.78, for white wine/champagne Pintercept=0.31) (Supplementary Table 3). The selected educational attainment genetic variants showed different effects in women and men, indicating that the effect of educational attainment on red wine and white wine/champagne intake was more pronounced among men (For red wine, Figure 1B, IVW, beta of women and men, 0.24 vs 0.44, P<0.001; for white wine/champagne, Figure 1C, IVW, beta of women and men, 0.18 vs 0.30, P<0.001). Participant with higher educational attainment were likely to have less beer/cider (Figure 1E, IVW beta=−0.26, 95% CI −0.28 to −0.24, P=4.07E-175) and spirits (Figure 1F, IVW beta=−0.16, 95% CI −0.17 to −0.14, P=7.08E-77).

In addition, men with higher educational attainment were more likely to have less beer/cider compared with women (Figure 1E). We also found sex differences for the association between education and spirits intake: women with higher educational attainment were more likely to have less spirits compared with men (Figure 1F).

We did not find consistent evidence for the association between educational attainment and fortified wine in neither women nor men (Figure 1D).

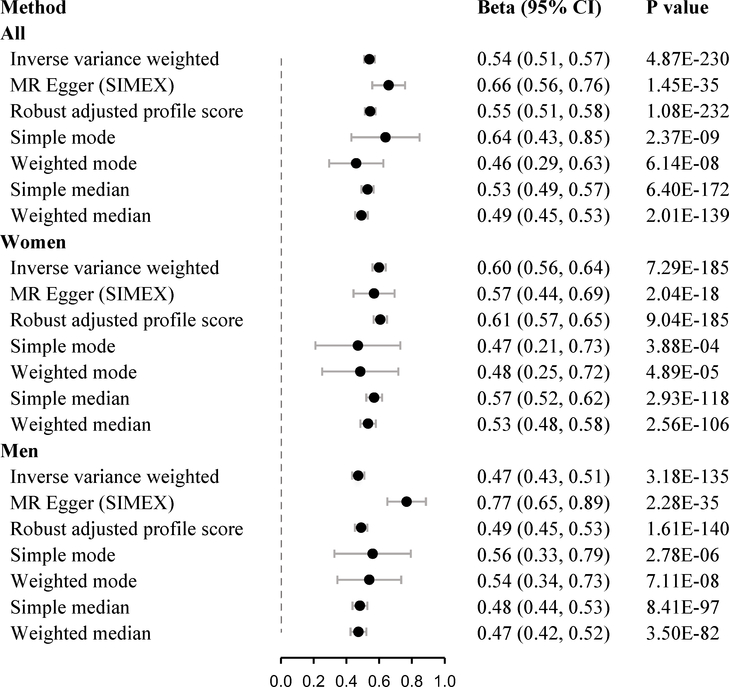

Alcohol intake frequency

We found an association of educational attainment and alcohol intake frequency. More years in genetically determined education were significantly associated with an increased likelihood of alcohol intake frequency according to the IVW method (Figure 2, beta=0.54, 95% CI: 0.51to 0.57, P=4.87E-230). The direction of effect remained consistently significant across all four methods, although confidence intervals were wider in some methods. No evidence of pleiotropy was found according to the intercept of MR-Egger (Pintercept=0.74) (Supplementary Table 3). Additionally, the effect of educational attainment on alcohol intake frequency was more pronounced among women (IVW, beta of women and men, 0.60 vs 0.47, P<0.001) (Figure 2).

Figure 2.

Associations of educational attainment and alcohol intake frequency from Mendelian Randomization (MR) analyses.

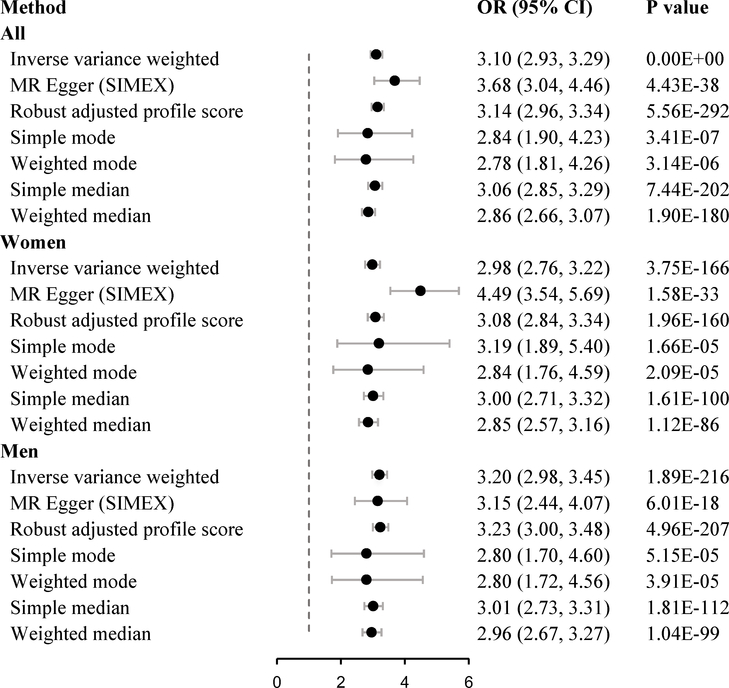

Alcohol taken with meals

We found that participants with higher educational attainment were more likely to take alcohol with meals (Figure 3, IVW, odds ratio (OR)=3.10, 95% CI: 2.93 to 3.29, P=0.00E+00). The intercept in the MR Egger analysis indicated no pleiotropy (Supplementary Table 3, Pintercept=0.85). Results were consistent when using weighted median and mode-based methods. For sex differences, both women and men with higher educational attainment were similarly more likely to drink alcohol with meals (Figure 3).

Figure 3.

Associations of educational attainment and alcohol taken with meals from Mendelian Randomization (MR) analyses.

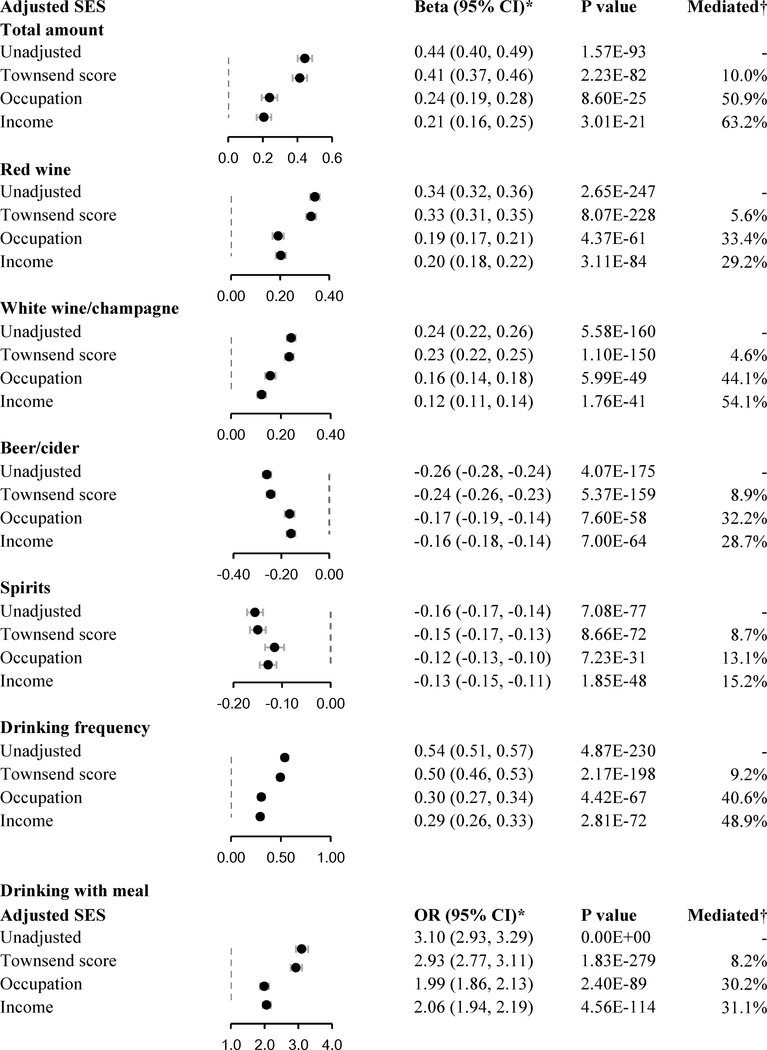

Sensitivity analyses

Full details of sensitivity analyses are provided in the supplementary files. Briefly, we found that the associations between educational attainment and intake of red wine, white wine/champagne, and drinking frequency were more pronounced among smokers (All P<0.005), whereas no significant difference was found for association between educational attainment and drinking with meals among smokers and nonsmokers (Supplementary Figure 1–3, Supplementary Table 3). The association between educational attainment and drinking was attenuated but remained significant after adjustment for socioeconomic status including income, occupation, and deprivation index (Figure 4). Further mediation analysis showed that association of educational attainment with drinking behaviors was mediated by approximately up to two-third through income, half through occupation, and one-tenth through material deprivation (All P <0.0001) (Figure 4). For results stratified by education and income, the associations are largely consistent across different income or education levels based on the inverse variance weighted method (Supplementary Figure 4–9, Supplementary Table 3).

Figure 4.

Estimates for the association of education with drinking behaviors explained by the socioeconomic status. *Beta value was estimated using inverse-variance weighted Mendelian randomization methods; †The proportion of the association of education with drinking behaviors that was mediated by socioeconomic status was estimated by dividing the indirect effect by the total effect (P <0.0001 for all the effects with adjustment for age and sex according to observational results). SES, socioeconomic status.

Discussion

In this Mendelian randomization study using four complementary methods, we found consistent evidence that higher educational attainment was related to increased amount of alcohol consumption, especially red wine and white wine/champagne. In addition, higher educational attainment was also related to a higher frequency of alcohol drinking and drinking alcohol with meals.

Our finding that participants with a genetically-determined higher level of education had a higher amount of alcohol intake is consistent with previous observational studies [20]. Social context might be a key determinant on how much alcohol individuals consume. Our results indicated that socioeconomic status significantly mediated the association between educational attainment and drinking behaviors by approximately up to two-third. Educational attainment has a significant impact on social position and opportunities, which are closely related to drinking culture [37]. It was found that more educated individuals were not only more likely to have a higher wage to afford to drink more, but also were healthier than their less educated counterparts, who consumed less alcohol because of health problems [38, 39]. In addition, drinking habit picked up in college might be another reason. College attendance was found to increase the risk of heavy alcohol intake among white young adults [17], which might be partially explained by living away from parents, time socializing with friends, having a higher likelihood of risk taking or sensation seeking, and treating alcohol intake as pleasure and a normal part of life [40, 41]. We found that the effect of higher educational attainment on the amount of alcohol intake was more pronounced among women than men. Women with higher educational attainment were found to be more likely to go into high-end service industries that favor alcohol consumption, thus more likely to indulge in hazardous drinking [27, 39]. However, men enjoyed alcohol more than women, and work-place showed less impact on men’s drinking patterns [42].

For various types of alcohol intake, higher educational attainment was associated with higher red wine and lower beer/cider consumption in both women and men, while sex-difference was found for red wine, as well as white wine/champagne, beer/cider, and spirits. Higher education increases the likelihood of getting access to health information such as wine but not beer/cider or spirits reduced risks of diseases such as CHD, diabetes, and hypertension [6, 43, 44], leading to choosing healthier beverage type (e.g. red wine) and avoiding unhealthy drink (e.g. beer/cider and spirits) [45]. The sex-difference for the association between educational attainment and beverage preference might be partly explained by the differing effects of alcohol on men and women [42]. Although generally consuming less alcohol than men, women are more likely to suffer severe brain and other organ damage than men following heavy drinks [46]. Generally, women prefer wine, and men prefer spirits. Such gender difference might overwhelm the effect of educational attainment on beverage preference [47].

Though participants with higher level of education had higher amount of alcohol intake, they tend to take alcohol in a more frequent manner (given the amount) than those with a low level of education. Data from National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey (NHANES I) and its follow-up surveys showed that participants with higher education (≥high school) had higher weekly number of drinks compared with those with lower education (<high school) [21]. Educational attainment is among the most commonly used measure of socioeconomic status in epidemiological studies [48] and a previous study suggests that people with higher socioeconomic status tend to drink smaller amounts more frequently [49]. Evidence suggests that the highest-quantity, lowest-frequency drinkers have the poorest diet quality while the lowest-quantity, higher-frequency drinkers have the best [50]. Similarly to the sex difference for the amount of alcohol intake, the association between educational attainment and alcohol intake frequency was more pronounced among women for their social position, physiological feature and health knowledge on drinking [37, 42].

Educational attainment may also affect the drinking habit of whether consuming alcohol with a meal through providing better health information. As observed in the current study, more educated participants were more likely to take alcohol with a meal for its benefit [16]. Drinking with meals slows alcohol absorption [14] and increases the rate of alcohol elimination [51]. For example, it was found that taking red wine together with the noon meal decreased the postprandial blood pressure of centrally obese, hypertensive individuals [16].

Harmful use of alcohol is a well-established risk factor for all-cause mortality [52]. Recent global data suggested even an alcohol consumption of <100g per week adversely affect health [1, 53]. Alcohol consumption can cause several types of cancer including esophageal, liver and breast cancer [54], and even light drinkers increased risk of oral cavity, pharynx, esophagus, and breast cancers [11–13]. Though alcohol consumption showed beneficial effect on kidney cancers and non-Hodgkin lymphoma, the National cancer institute suggests that any potential benefits of alcohol consumption on cancer are likely outweighed by the adverse effect of alcohol consumption. Observational studies have shown a beneficial effect of moderate alcohol consumption on CVD risk [7, 43, 55]. However, accumulating evidence using methodologies such as Mendelian randomization [10, 56], pooling cohort studies, and multivariable-adjusted meta-analyses [57] have challenged the concept that little-to-moderate alcohol consumption is universally related to a lower CVD risk [58]. Further, the observed beneficial effects are likely to be offset when taking other diseases into account [1]. Given the overall adverse effect of alcohol consumption on health, higher education might adversely affect health by increasing alcohol consumption. Thus, effort should be made to lower the amount of alcohol intake and promote healthy drinking behaviors among people with higher education.

The major strengths of this study include the large sample size, availability of detailed alcohol phenotypic data, and complementary MR methods used in the analysis. However, our study had several potential limitations. First, it is unlikely to avoid heterogeneity for potential pleiotropic effects or different mechanisms of association with the exposure by using so many SNPs as instruments. Although heterogeneity in causal estimates is of concern, provided that the pleiotropic effects of genetic variants are equally likely to be positive or negative, the overall estimate based on all the genetic variants may be unbiased [59]. Here we used a random-effects model in IVW methods considering for heterogeneity. Given that MR-Egger intercept suggested no evidence of horizontal pleiotropy and MR-PRESSO showed a consistent result after removal of pleiotropic outliers, our results were unlikely due to pleiotropy [30]. In addition, a recent study showed no genetic correlation between years of education and drinking frequency [60], suggesting these two phenotypes were unlikely to share some of their underlying genome-wide genetic architecture. Second, the association between educational attainment and drinking behaviors was attenuated but remained significant after adjustment for socioeconomic status. According to our mediation analysis, socioeconomic status was on the pathway between education and drinking behaviors; and therefore was not included in our main MR modeling because it might be causally affected by education [61, 62]. Third, because we studied only white British populations, our findings might not be generalizable to other ethnic groups, especially those with different cultures of alcohol intake, such as the Asian population. Fourth, we noted that UK Biobank is in the SSGAC. In the current study, the overlap rate was 334507/1131881=29.5%, and the calculated bias and type 1 error rate around 0.001 and 0.05, suggesting that findings were less likely to be biased by the sample overlap [63]. Finally, the alcohol intake measures used in this study were self-reported, which may lead to measurement bias.

In summary, our study indicates interesting relations between educational attainment drinking behaviors. Participants with higher education tend to drink more but also tend to maintain relative healthier drinking behaviors, compared with those less educated. Growing evidence has linked alcohol intake with adverse health outcomes. Our data highlights the importance of targeting people with higher education backgrounds in campaigns for lowering the amount of alcohol intake and improving healthy drinking behaviors.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgements

The study was supported by grants from the National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute (HL071981, HL034594, HL126024), the National Institute of Diabetes and Digestive and Kidney Diseases (DK091718, DK100383, DK078616), the Boston Obesity Nutrition Research Center (DK46200), and United States–Israel Binational Science Foundation Grant 2011036. Dr. Qi was a recipient of the American Heart Association Scientist Development Award (0730094N). All investigators are independent from funders.

Footnotes

Compliance with ethical standards: The authors declare that they have no conflict of interest.

Data deposition: Researchers can apply to use the UK Biobank resource and access the data used.

Supplementary information is available at MP’s website.

REFERENCE

- 1.Griswold MG, Fullman N, Hawley C, Arian N, Zimsen SRM, Tymeson HD, et al. Alcohol use and burden for 195 countries and territories, 1990–2016: a systematic analysis for the Global Burden of Disease Study 2016. Lancet. 2018;392:1015–1035. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.World Health Organisation. Global Status Report on Alcohol and Health 2018. 2018.

- 3.Xi B, Veeranki SP, Zhao M, Ma C, Yan Y, Mi J. Relationship of Alcohol Consumption to All-Cause, Cardiovascular, and Cancer-Related Mortality in U.S. Adults. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2017;70:913–922. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Ricci C, Wood A, Muller D, Gunter MJ, Agudo A, Boeing H, et al. Alcohol intake in relation to non-fatal and fatal coronary heart disease and stroke:EPIC-CVD case-cohort study. BMJ. 2018;361:k934.. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Thadhani R, Camargo CA, Stampfer MJ, Curhan GC, Willett WC, Rimm EB. Prospective study of moderate alcohol consumption and risk of hypertension in young women. Arch Intern Med. 2002;162:569–574. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Witkow S, Sarusi B, Leitersdorf E, Blüher M, Schwarzfuchs D, Ceglarek U, et al. Effects of Initiating Moderate Alcohol Intake on Cardiometabolic Risk in Adults With Type 2 Diabetes. Ann Intern Med. 2015;163:569. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Brien SE, Ghali WA, Mukamal KJ, Turner BJ, Ronksley PE. Association of alcohol consumption with selected cardiovascular disease outcomes: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Bmj. 2011;342:d671–d671. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Martin MA, Goya L, Ramos S. Protective effects of tea, red wine and cocoa in diabetes. Evidences from human studies. Food Chem Toxicol. 2017;109:302–314. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Garaycoechea JI, Crossan GP, Langevin F, Mulderrig L, Louzada S, Yang F, et al. Alcohol and endogenous aldehydes damage chromosomes and mutate stem cells. Nature. 2018;553:171–177. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Holmes MV, Dale CE, Zuccolo L, Silverwood RJ, Guo Y, Ye Z, et al. Association between alcohol and cardiovascular disease: Mendelian randomisation analysis based on individual participant data. BMJ. 2014;349:1–16. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Chen WY, Rosner B, Hankinson SE, Colditz GA, Willett WC. Moderate alcohol consumption during adult life, drinking patterns, and breast cancer risk. JAMA - J Am Med Assoc. 2011;306:1884–1890. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Bagnardi V, Rota M, Botteri E, Tramacere I, Islami F, Fedirko V, et al. Light alcohol drinking and cancer: A meta-analysis. Ann Oncol. 2013;24:301–308. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Cao Y, Willett WC, Rimm EB, Stampfer MJ, Giovannucci EL. Light to moderate intake of alcohol, drinking patterns, and risk of cancer: Results from two prospective US cohort studies. BMJ. 2015;351:1–8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Shearman D, Wishart J, Collins P, Horowitz M, Bochner M, Bratasiuk R, et al. Relationships between gastric emptying of solid and caloric liquid meals and alcohol absorption. Am J Physiol Liver Physiol. 2017;257:G291–G298. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Breslow RA, Graubard BI. Prospective study of alcohol consumption in the United States: Quantity, frequency, and cause-specific mortality. Alcohol Clin Exp Res. 2008;32:513–521. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Foppa M, Fuchs FD, Preissler L, Andrighetto A, Rosito GA, Duncan BB. Red wine with the noon meal lowers post-meal blood pressure: a randomized trial in centrally obese, hypertensive patients. J Stud Alcohol. 2002;63:247–251. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Paschall MJ, Bersamin M, Flewelling RL. Racial/Ethnic differences in the association between college attendance and heavy alcohol use: a national study. J Stud Alcohol. 2005;66:266–274. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Gilman SE, Breslau J, Conron KJ, Koenen KC, Subramanian S V., Zaslavsky AM. Education and race-ethnicity differences in the lifetime risk of alcohol dependence. J Epidemiol Community Health. 2008;62:224–230. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Crum RM, Helzer JE, Anthony JC. Level of education and alcohol abuse and dependence in adulthood: A further inquiry. Am J Public Health. 1993;83:830–837. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Huerta MC, Borgonovi F. Education, alcohol use and abuse among young adults in Britain. Soc Sci Med. 2010;71:143–151. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Moore AA, Gould R, Reuben DB, Greendale GA, Carter MK, Zhou K, et al. Longitudinal patterns and predictors of alcohol consumption in the United States. Am J Public Health. 2005;95:458–464. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Droomers M, Schrijvers CTM, Stronks K, Van De Mheen D, Mackenbach JP. Educational differences in excessive alcohol consumption: The role of psychosocial and material stressors. Prev Med (Baltim). 1999;29:1–10. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Paschall M, Lipton RI. Wine preference and related health determinants in a U.S. national sample of young adults. Drug Alcohol Depend. 2005;78:339–344. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Davey Smith G, Ebrahim S. ‘Mendelian randomization’: can genetic epidemiology contribute to understanding environmental determinants of disease? Int J Epidemiol. 2003;32:1–22. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Angrist JD, Imbens GW, Rubin DB. Identification of causal effects using instrumental variables. J Am Stat Assoc. 1996;91:444–455. [Google Scholar]

- 26.Lee JJ, Wedow R, Okbay A, Kong E, Maghzian O, Zacher M, et al. Gene discovery and polygenic prediction from a genome-wide association study of educational attainment in 1.1 million individuals. Nat Genet. 2018;50:1112–1121. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Kuntsche S, Gmel G, Knibbe RA, Kuendig H, Bloomfield K, Kramer S, et al. Gender and cultural differences in the association between family roles, social stratification, and alcohol use: a European cross-cultural analysis. Alcohol and Alcoholism. 2006;41(suppl_1):i37–46. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Okbay A, Beauchamp JP, Fontana MA, Lee JJ, Pers TH, Rietveld CA, et al. Genome-wide association study identifies 74 loci associated with educational attainment. Nature. 2016;533:539–542. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Hemani G, Zheng J, Elsworth B, Wade KH, Haberland V, Baird D, et al. The MR-Base platform supports systematic causal inference across the human phenome. Elife. 2018;7:e34408. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Wootton RE, Lawn RB, Millard LAC, Davies NM, Taylor AE, Munafo MR, et al. Evaluation of the causal effects between subjective wellbeing and cardiometabolic health: Mendelian randomisation study. BMJ. 2018;362:k3788. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Lawlor DA, Tilling K, Smith GD. Triangulation in aetiological epidemiology. Int J Epidemiol. 2016;45:1866–1886. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Bowden J, Smith GD, Burgess S. Mendelian randomization with invalid instruments: Effect estimation and bias detection through Egger regression. Int J Epidemiol. 2015;44:512–525. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Verbanck M, Chen CY, Neale B, Do R. Detection of widespread horizontal pleiotropy in causal relationships inferred from Mendelian randomization between complex traits and diseases. Nat Genet. 2018;50:693–698. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Bowden J, Fabiola Del Greco M, Minelli C, Smith GD, Sheehan NA, Thompson JR. Assessing the suitability of summary data for two-sample mendelian randomization analyses using MR-Egger regression: The role of the I2statistic. Int J Epidemiol. 2016;45:1961–1974. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Valeri L, VanderWeele TJ. Mediation Analysis Allowing for Exposure–Mediator Interactions and Causal Interpretation: Theoretical Assumptions and Implementation With SAS and SPSS Macros. Psychol Methods. 2013;18:137–150. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Burgess S, Daniel RM, Butterworth AS, Thompson SG. Network Mendelian randomization: Using genetic variants as instrumental variables to investigate mediation in causal pathways. Int J Epidemiol. 2015;44:484–495. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Månsdotter A, Backhans M, Hallqvist J. The relationship between a less gender-stereotypical parenthood and alcohol-related care and death: a registry study of Swedish mothers and fathers. BMC Public Health. 2008;8:312. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Davies NM, Dickson M, Smith GD, van den Berg GJ, Windmeijer F. The causal effects of education on health outcomes in the UK Biobank. Nat Hum Behav. 2018;2:117–125. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.OECD (2015). Tackling Harmful Alcohol Use: Economics and Public Health Policy. OECD Publishing; 2015. [Google Scholar]

- 40.Webb E, Ashton CH, Kelly P, Kamali F. Alcohol and drug use in UK university students. Lancet. 1996;348:922–925. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Paschall MJ, Flewelling RL. Postsecondary education and heavy drinking by young adults: the moderating effect of race. J Stud Alcohol. 2002;63:447–455. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Holmila M, Raitasalo K. Gender differences in drinking: Why do they still exist? Addiction. 2005;100:1763–1769. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Hines LM. Moderate alcohol consumption and coronary heart disease: a review. Postgrad Med J. 2002;77:747–752. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Golan R, Gepner Y, Shai I. Wine and Health–New Evidence. Eur J Clin Nutr. 2018. 2018. 10.1038/s41430-018-0309-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Tverdal A, Magnus P, Selmer R, Thelle D. Consumption of alcohol and cardiovascular disease mortality: a 16 year follow-up of 115,592 Norwegian men and women aged 40–44 years. Eur J Epidemiol. 2017;32:775–783. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Ceylan-Isik AF, McBride SM, Ren J. Sex difference in alcoholism: Who is at a greater risk for development of alcoholic complication? Life Sci. 2010;87:133–138. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.KLATSKY AL, ARMSTRONG MA, KIPP H. Correlates of alcoholic beverage preference: traits of persons who choose wine, liquor or beer. Br J Addict. 1990;85:1279–1289. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Winkleby MA, Jatulis DE, Frank E, Fortmann SP. Socioeconomic status and health: How education, income, and occupation contribute to risk factors for cardiovascular disease. Am J Public Health. 1992;82:816–820. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Christensen HN, Diderichsen F, Hvidtfeldt UA, Lange T, Andersen PK, Osler M, et al. Joint effect of alcohol consumption and educational level on alcohol-related medical events: A danish register-based cohort study. Epidemiology. 2017;28:872–879. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Breslow RA, Guenther PM, Smothers BA. Alcohol drinking patterns and diet quality: The 1999–2000 National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey. Am J Epidemiol. 2006;163:359–366. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Ramchandani VA, Kwo PY, Li T. Effect of food and food composition on alcohol elimination rates in healthy men and women. J Clin Pharmacol. 2001;41:1345–1350. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Wood AM, Kaptoge S, Butterworth AS, Willeit P, Warnakula S, Bolton T, et al. Risk thresholds for alcohol consumption: combined analysis of individual-participant data for 599 912 current drinkers in 83 prospective studies. Lancet. 2018;391:1513–1523. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Burton R, Sheron N. No level of alcohol consumption improves health. Lancet. 2018;392:987–988. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Baan R, Straif K, Grosse Y, Secretan B, El Ghissassi F, Bouvard V, et al. Carcinogenicity of alcoholic beverages. Lancet Oncol. 2007;8:292–293. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Smyth A, Teo KK, Rangarajan S, O’Donnell M, Zhang X, Rana P, et al. Alcohol consumption and cardiovascular disease, cancer, injury, admission to hospital, and mortality: A prospective cohort study. Lancet. 2015;386:1945–1954. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Millwood IY, Walters RG, Mei XW, Guo Y, Yang L, Bian Z, et al. Conventional and genetic evidence on alcohol and vascular disease aetiology: a prospective study of 500 000 men and women in China. Lancet. 2019;6736:1–12. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Degenhardt L, Charlson F, Ferrari A, Santomauro D, Erskine H, Mantilla-Herrara A, et al. The global burden of disease attributable to alcohol and drug use in 195 countries and territories, 1990–2016: a systematic analysis for the Global Burden of Disease Study 2016. The Lancet Psychiatry. 2018;5:987–1012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Criqui MH, Thomas IC. Alcohol Consumption and Cardiac Disease: Where Are We Now? J Am Coll Cardiol. 2017;69:25–27. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Burgess S, Bowden J, Fall T, Ingelsson E, Thompson SG. Sensitivity analyses for robust causal inference from mendelian randomization analyses with multiple genetic variants. Epidemiology. 2017;28:30–42. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Liu M, Jiang Y, Wedow R, Li Y, Brazel DM, Chen F, et al. Association studies of up to 1.2 million individuals yield new insights into the genetic etiology of tobacco and alcohol use. Nat Genet. 2019. 2019. 10.1038/s41588-018-0307-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Card D The causal effect of education on earnings. In: Handbook of labor economics, vol. 3, Elsevier; 1999. pp 1801–1863. [Google Scholar]

- 62.Holmes MV, Ala-Korpela M, Smith GD. Mendelian randomization in cardiometabolic disease: Challenges in evaluating causality. Nat Rev Cardiol. 2017;14:577–599. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Burgess S, Davies NM, Thompson SG. Bias due to participant overlap in two-sample Mendelian randomization. Genet Epidemiol. 2016;40:597–608. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.