Abstract

This study aimed to review information on the subaxial cervical pedicle screw (CPS) including recent anatomical considerations, entry points, placement techniques, accuracy, learning curve, and complications. Relevant literatures were reviewed, and the authors’ experiences were summarized. The CPS is used for reconstruction of unstable cervical spine and achieves superior biomechanical stability compared to other fixation techniques. Various insertion and guidance techniques are established, among which, lateral fluoroscopy-assisted placement is the most common and cost-effective technique. Generally, placement under imaging guidance is more accurate than other techniques, and a three-dimensional template allows optimal trajectory for each pedicle regardless of intraoperative changes in spinal alignment. The free-hand technique using a curved pedicle probe without a funnel-like hole increases screw stability and reduces operation time, radiation exposure, and soft tissue injury. Compared to conventional lateral fluoroscopy-assisted placement, free-hand CPS placement by trained surgeons achieves superior accuracy comparable to that of image-guided navigation; in general, 30 training cases are sufficient for learning a safe and accurate technique for CPS placement. The complications of subaxial CPS are classified into three categories: complications due to screw misplacement, complications without screw misplacement, and others. Inexperienced surgeons may benefit from advanced techniques; however, the accuracy of CPS ultimately depends on the surgeon’s experience. Inexperienced surgeons should master the placement of the thoracolumbar pedicle screw in real practice and practice CPS insertion using cadavers. During the initial phase of the learning curve, careful preparation of surgery, reiterated identification, patterned safety steps, and supervision of the expert are necessary.

Keywords: cervical spine, pedicle screw, internal fixation, learning curve

Introduction

Instrumented fusion surgery of the cervical spine is commonly performed for the treatment of cervical spine diseases. The instrumentation-based treatment approach in patients with cervical spine disorders involves pedicle screw, lateral mass screw, laminar screw and transfacet screw fixations.1–5) Subaxial cervical pedicle screw (CPS) placement yields the strongest biomechanical stability, which results in short segment fixation, preservation of the mobile segment, higher fusion rate, earlier mobilization and rehabilitation, and ultimately, a superior clinical outcome compared to other methods (Fig. 1).2,4,6–10)

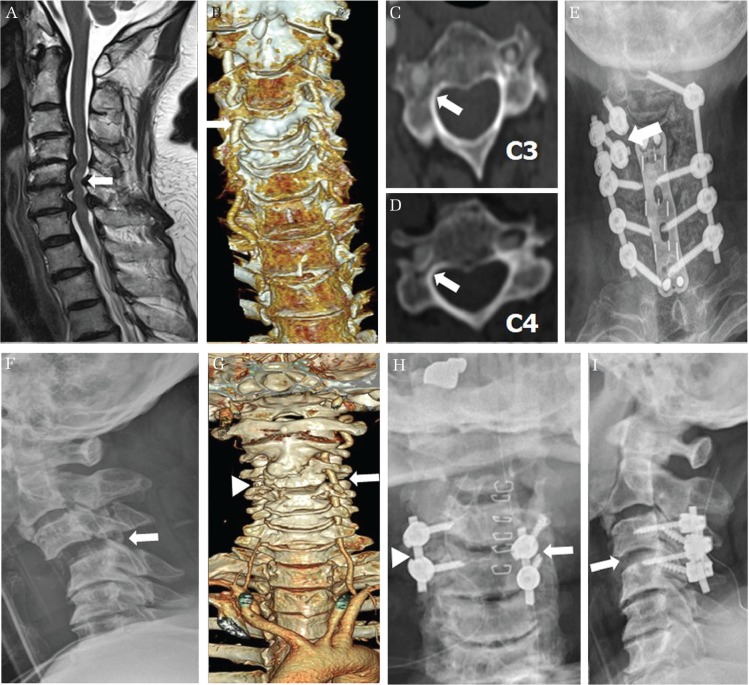

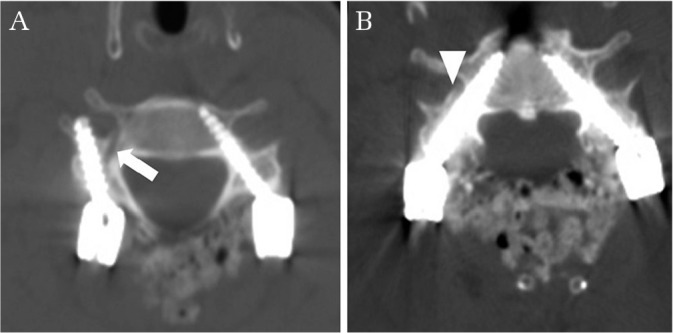

Fig. 1.

Various cases of subaxial cervical pedicle screw (CPS) insertion. (A and B) A short segment fixation of a Hangman fracture patient. Preoperative computed tomography scan shows C2 hangman fracture (white arrow in A). Postoperative simple lateral radiograph shows a short segment fixation of CPS and reduced kyphosis of Hangman fracture (white arrowhead in B). (C and D) A reduction and fixation of a fractured bamboo spine with ankylosing spondylitis. Preoperative computed tomography scan shows a C5 fracture (white arrow in C). A simple lateral radiograph shows a well-aligned correction using short segment instrumentation (white arrowhead in D). (E and F) Reduction of traumatic spondyloptosis. Preoperative computed tomography scan shows a traumatic spondyloptosis on C7–T1 level (white arrow in E). This spondyloptosis was corrected and fused successfully by only posterior short segment instrumentation of CPS at the C6–T1 level (white arrowhead in F) in the postoperative computed tomography scan. (G–I) Correction of cervical kyphosis with infectious spondylodiscitis. Preoperative computed tomography scan shows a fixed cervical kyphosis with infectious spondylodiscitis at the C6 and C7 level (white arrow in G). After anterior C6 corpectomy with a grade IV osteotomy and support with mesh cage, the posterior short segment fixation of CPS from C5–C7 (white arrowhead in H) with a grade II osteotomy were performed. Postoperative computed tomography scan shows a well-aligned correction of kyphosis (white arrowhead in I).

Abumi et al.11,12) first reported subaxial CPS placement for traumatic lesions and subsequently expanded CPS application to non-traumatic lesions, reconstruction of the craniocervical junction, and correction of cervical kyphosis for stabilization of the unstable motion segment. CPS placement offers three-column fixation and has greater pullout strength than lateral mass screw placement.13–16) However, the small size of the mid-cervical pedicle, a large transverse angle of the cervical pedicle, and possible risk of vertebral artery (VA) and nerve root injury limit the routine application of subaxial CPS placement.13) In this study, we review current information on cervical CPS placement techniques for various applications and summarize the efficacies, technical guidelines, and potential adverse events. In addition, we provide an evidence-based recommendation to avoid neurovascular complications.

Selection of Reference Articles

A systemic literature review was performed through a search of PubMed using the following keywords: CPS, anatomy, entry point, accuracy, learning curve, and complication. Relevant articles were selected, and further sources were obtained from the references of selected articles. The authors’ experiences of patients with an unstable cervical spine who underwent treatment using CPS were described.

Anatomical considerations for the safety and accuracy of the cervical pedicle screw

For accurate and safe subaxial CPS placement, surgeons should understand the detailed three-dimensional (3D) morphology of the pedicle. With regard to reports on the morphology of the cervical pedicle,17–23) the measured parameters including pedicle transverse angle (PTA) and pedicle outer width (POW) are indicated in Fig. 2A. The smallest mean POW of 4.5 mm was obtained at C3, with gradual increases in the mean value caudally from C3 to C7.17,22) Karaikovic et al.24) reported that if the POW is sufficiently large, a canal of adequate size can be made with an appropriate tap, regardless of the pedicle inner width. Abumi et al.25) used 3.5–4.5-mm diameter screws and reported that screw insertion was difficult or impossible in cases with a POW of <4 mm; whereas, Park et al.26) used 3.5–4.5-mm diameter pedicle screws in cases with a POW of >3 mm on axial computed tomography (CT) scan. The pedicle axes at C3 and C4 are slightly elevated compared to the superior endplate of the vertebral body, and those at C5–C7 are parallel and directed slightly downward (Fig. 2B).17)

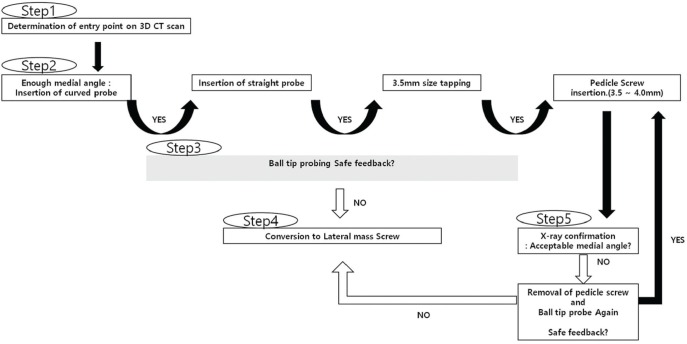

Fig. 2.

Anatomical considerations for a subaxial cervical pedicle screw. (A) The pedicle outer width (POW) ranges from 5.4 to 6.6 mm. The smallest mean POW of 4.5 mm is at C3, with gradual increases of the mean value caudally from C3 to C7. The overall mean pedicle transverse angle (PTA) ranges from 33.6° to 50.2°, approximately 45° from C3 to C6 and 33° at C7. (B) The pedicle axes at C3 and C4 are slightly elevated compared to the superior endplate of the vertebral body, and those at C5–C7 are parallel and directed slightly downward.

Liu et al.18) reported that the cervical pedicles were smaller overall in Asians than in Europeans and Americans, and female individuals of both races had smaller pedicles than their male counterparts. However, the soft-tissue layer at the posterior aspect of the neck is thinner in Asians than in Europeans and Americans. Thickness of the soft tissue attributed to the muscles and fat tissue contributes to a muscle-pushing effect, which leads to screw malposition and seems to be a more important affecting factor for a violation than the pedicle diameter. Based on these reasons, the CPS was initially developed and is frequently used in Asia. Therefore, planning of subaxial CPS placement should consider the factors of the patient’s sex, race, and importantly, individual neck morphology.

In general, the VA passes anterior to the lateral mass of C7 into the transverse foramen at C6 and courses upward to the transverse foramen at C1.8) A preoperative axial CT finding of thinning of the pedicle on one side indicates enlargement of the transverse foramen or invasion of the vertebral body, and magnetic resonance angiography or computed tomography angiography is needed to evaluate VA anomalies such as a tortuous course or unilateral-predominance. In patients with a VA anomaly or asymmetric unilateral dominance, surgeons should consider alternative safer techniques such as lateral mass screw insertion (Fig. 3).

Fig. 3.

The primary choice of a lateral mass screw for a vertebral artery (VA) anomaly and unilateral dominance. (A–E) The magnetic resonance imaging shows a C4–C7 cervical spondylosis and spinal cord compression (white arrow in A). The three dimensional computed tomography scan shows a unilaterally dominant VA to the right side (white arrow in B). A thinned right side pedicle of C3 and C4 (white arrow in C and D) indicates enlargement of the transverse foramen and invasion of the unilaterally dominant VA to the vertebral body. At the right C3 and C4, lateral mass screws (white arrow in E) were primarily chosen instead of the cervical pedicle screw (CPS) because of a unilaterally dominant VA. (F–I) The simple lateral radiograph shows cervical subluxation of C3 and C4 (white arrow in F). The VA of the three dimensional computed tomography scan is dominant to the left side (white arrow in G). A right side VA is invisible (white arrowhead in G). Therefore, right C3 and C4 were fixed by CPS (white arrowhead in H) and left C3 and C4 were primarily fixed by lateral mass screw (white arrow in H) instead of CPS. The simple lateral radiograph shows correction of subluxation (white arrow in I).

Entry point and trajectory for subaxial cervical pedicle screw placement

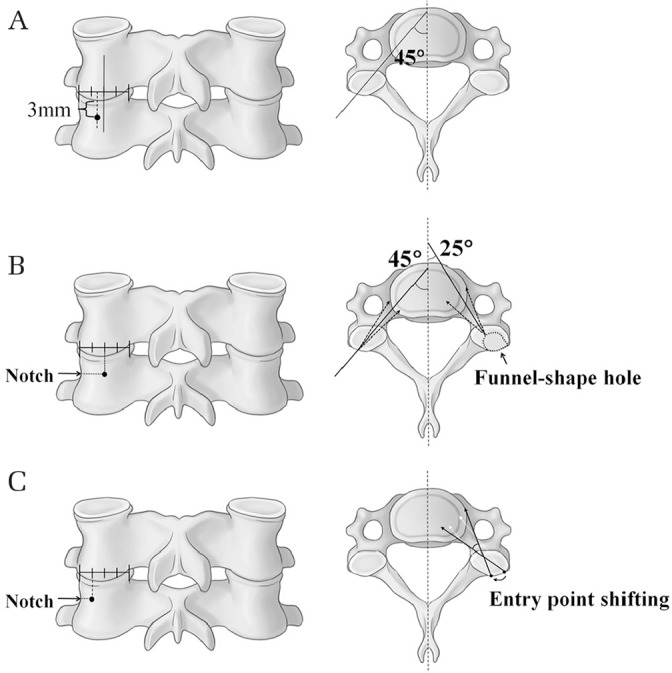

The conventional entry point of CPS is 3 mm below the superior facet joint. The drill is angled 45° medially and advanced in a vertical line parallel to the endplate (Fig. 4A).13)

Fig. 4.

Various entry points and trajectories for subaxial cervical pedicle screw (CPS) placement. (A) The conventional entry point of CPS is 3 mm below the superior facet joint. The drill is angled 45° medially and advanced in a vertical line parallel to the endplate. (B) Abumi et al.25) recommended the location of the entry point at the posterior surface of the lateral mass at the bisecting point of the width of each facet joint. They created funnel-shaped holes in the lateral mass to shorten the length of the cervical pedicle, which achieved safety through the widening of the zone of the screw trajectory angle. (C) Park et al.26,30) used a curved pedicle probe with an entry point at one-fourth width medial to the lateral border of the superior articular process in the axial plane; during widening of the pilot hole and straightening of the cancellous pedicle track using curved and straight pedicle probes, the original entry point was shifted medially, which resulted in a wider zone of the safe angle without the need of a funnel-shaped hole.

Abumi et al.25) recommended the locations of the entry point at the posterior surface of the lateral mass at the bisecting point of the width of each facet joint. In that study, funnel-shaped holes were made in the lateral mass to shorten the length of the cervical pedicle, which enhanced the safety by widening the zone of the screw trajectory angle. Those authors recommended a screw insertion angle at the transverse plane of 25–45° medial to the midline and at the sagittal plane parallel to the cranial endplate for the pedicles of C5 through C7 and in a slightly cephalad direction for those of C2 through C4 (Fig. 4B).

Many authors recommended that the entry point should be as lateral as possible in the articular mass and at 50° in the transverse plane for a safe corridor.23,27) In agreement with this recommendation, Hacker et al.28) reported that a line parallel to the contralateral lamina of approximately 50° in the transverse plane was a reliable intraoperative guide for accurate screw placement; however, the larger transverse angle of screw insertion required a wider midline dissection to avoid screw malposition due to the muscle-pushing effect and associated soft-tissue injury or bleeding.29)

To overcome this problem, Park et al.26,30) used a curved pedicle probe with an entry point at one-fourth the width medial to the lateral border of the superior articular process in the axial plane at C3–C6 and at half width at C7 based on the notch level in the sagittal plane. During widening of the pilot hole and straightening of the cancellous pedicle track using curved and straight pedicle probes, the original entry point was shifted medially with a concomitant decrease of the medial angle compared to the anatomical pedicle angle. This change resulted in a wider zone of the safe angle without the need for a funnel-shaped hole, and consequently, a reduction in soft-tissue injury without unnecessary broad muscle dissection was achieved (Fig. 4C). In addition, CPS placement without a funnel-shaped hole allowed longer engagement between the bone and screw, which increased screw stability. They suggested that the sagittal trajectory should be perpendicular to the exposed lamina plane.

Insertion techniques for the subaxial cervical pedicle screw

Fluoroscopy-guided insertion

The conventional technique for subaxial CPS placement is comprised of the lateral fluoroscopy assisted procedure by Abumi et al.25) Fluoroscopy is considered the most cost-effective modality for accurate subaxial CPS placement and has gained popularity due to this advantage; however, it has a disadvantage of poor visualization of the lower cervical bony anatomy due to the overlying shoulders, and anterior–posterior fluoroscopic imaging is insufficient to guide the correct trajectory of the subaxial CPS placement. To overcome these disadvantages, Yukawa et al.31) introduced a fluoroscopic pedicle-axis view technique that can simultaneously reveal the appropriate entry point and trajectory angle for each cervical vertebra. The inclined axis of the fluoroscopic image showed that the pedicle axis matched the insertion point, thereby reducing the risk of pedicle perforation.

Image-guided navigation system

Image-guided navigation systems have recently evolved substantially. Among the newest generation of navigation, intraoperative 3D image-based navigation systems such as the SIREMOBIL Iso-C3D system (Siemens AG, Medical Solutions, Erlangen, Germany) or the O-arm Surgical Imaging System (Medtronic Inc., Littleton, MA, USA) are available. These systems do not require anatomical registration, and real-time updates of intraoperative anatomical changes can be obtained. Recently, several studies have reported percutaneous CPS placement using 3D fluoroscopy navigation systems.32–34) Komatsubara et al.32) reported that 3D fluoroscopy-guided minimally invasive CPS placement through a posterolateral approach helped achieve a significant reduction in the surgery time, intraoperative bleeding, and screw deviation.

While these advanced navigation systems can improve the accuracy of CPS placement, they are not available on site at all hospitals due to the high cost, and surgeons who rely only on these systems may lose their surgical skill and experience in spinal instrument placement.26) In addition, movement of an adjacent segment of the spine or misalignment of the registration frame and optical array during surgery may lead to errors.

Three-dimensional template-guided cervical pedicle screw placement

The 3D template systems are custom navigation instruments for accurate CPS placement in individual patients. Lu et al.35) described that numerous commercial software packages for making 3D templates are available, but the manufacturing processes are similar. Preoperative planning and 3D simulation enables the surgeon to select the best trajectory and an appropriate screw for each pedicle, regardless of intraoperative changes in spinal alignment. The simplicity of template application reduces the operation time and radiation exposure36); an average of approximately 80 seconds are is required from fixation of the template at the lamina to insertion of the pedicle screws. Fluoroscopy is used once only after screw insertion. Nevertheless, navigational templates have the disadvantages of high cost and long duration from the software application to the construction of 3D models, which requires about 1–7 days.35)

Direct exposure of the pedicle through laminoforaminotomy

Ludwig et al.37) reported that direct exposure of the pedicle through laminoforaminotomy provides supplemental visual and tactile cues to access the medial, superior, and inferior aspects of pedicle. Laminoforaminotomy requires no preoperative preparation or expensive equipment, and the majority of spine surgeons perform laminoforaminotomy easily in a typical operating room environment. However, those authors conducted a cadaveric study and reported that laminoforaminotomy significantly decreased the risk of perforation at C7 alone, which indicates that laminoforaminotomy may not be useful for insertion of a CPS but can be used as an adjuvant technique for easy and direct identification of the pedicle.

Free-hand technique

Free-hand CPS placement is a technically demanding and difficult procedure. Several studies have focused on subaxial CPS placement, but few studies have assessed free-hand pedicle screw fixation in the subaxial cervical spine. Park et al.26,30) performed free-hand subaxial CPS placement with a curved pedicle probe without a funnel-like hole, and reported that the technique was effective, safe, and accurate; the free-hand technique reduced the surgical time, radiation exposure, soft tissue injury, and cost, and allowed conversion to lateral mass screw placement in case of insufficient ball-tip feedback. However, it is a difficult and unfamiliar technique, not only for inexperienced surgeons, but also for experienced surgeons.

Comparison of accuracy among different insertion techniques for CPS placement

The accuracy of subaxial CPS placement varies among studies.38) The studies reporting CPS perforation and neurovascular injury associated with various surgical techniques are summarized in Table 1.

Table 1.

Review of the literature on screw perforation and neurovascular injury

| Author | Method of insertion | No. of screws (No. of patients) | No. of breached screws (rate) | Grading system of breached screws | Neurovascular injury | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Vertebral artery injury | Nerve root injury | ||||||||||

| Abumi et al.39) | Lateral fluoroscopy | 669 (180) | 45 (6.7%) | 1 | 2 | ||||||

| Yoshimoto et al.27) | Lateral fluoroscopy | 134 (26) | 15 (11.1%) | Partial (<1/2 of screw diameter) | Complete (>1/2 of screw diameter) | 0 | 0 | ||||

| 10 (7.4%) | 5 (3.7%) | ||||||||||

| Yukawa et al.31) | Pedicle axis view by fluoroscopy | 620 (144) | 81 (13.1%) | Screw exposure (<1/2 of screw diameter) | Pedicle perforation (>1/2 of screw diameter) | 1 | 1 | ||||

| 57 (9.2%) | 24 (3.9%) | ||||||||||

| Kotani et al.44) | CT navigation | 78 (17) | 1 (1.2%) | 0 | 0 | ||||||

| Ito et al.43) | 3D navigation (Iso-C3D) | 176 (50) | 5 (2.8%) | Grade 1 (no perforation) | Grade 2 (≤2 mm) | Grade 3 (>2 mm) | 0 | 0 | |||

| 171 (97.2%) | 5 (2.8%) | 0 (0%) | |||||||||

| Ishikawa et al.41) | Lateral fluoroscopy | 126 (30) | 34 (27%) | Grade 0 (no perforation) | Grade 1 (<1 mm) | Grade 2 (≥1 and <2 mm) | Grade 3 (≥2 mm) | 1 | 0 | ||

| 92 (73.0%) | 12 (9.5%) | 6 (4.8%) | 16 (12.7%) | ||||||||

| 3D navigation (Iso-C3D) | 150 (32) | 28 (18.7%) | Grade 0 (no perforation) | Grade 1 (<1 mm) | Grade 2 (≥1 and <2 mm) | Grade 3 (≥2 mm) | 1 | 0 | |||

| 122 (81.3%) | 17 (11.3%) | 6 (4%) | 5 (3.3%) | ||||||||

| Ishikawa et al.42) | 3D navigation (O-arm) | 108 (21) | 12 (11.1%) | Grade 0 (no perforation) | Grade 1 (<2 mm) | Grade 2 (≥2 and <4 mm) | Grade 3 (>4 mm) | ||||

| 96 (88.9%) | 9 (8.3%) | 3 (2.8%) | 0 (0%) | ||||||||

| Chachan et al.40) | 3D navigation (O-arm) | 241 (44) | 17 (7.05%) | Grade 0 (no perforation) | Grade 1 (<2 mm) | Grade 2 (≥2 and <4 mm) | Grade 3 (>4 mm) | 0 | 0 | ||

| 224 (92.95%) | 10 (4.15%) | 7 (2.90%) | 0 (0%) | ||||||||

| Jo et al.46) | Laminoforaminotomy | 104 (12) | 29 (27.9%) | Grade 0 (no perforation) | Grade 1 (<25% of screw diameter) | Grade 2 (25–50% of screw diameter) | Grade 3 (>50% of screw diameter) | 0 | 0 | ||

| 75 (72.1%) | 20 (19.2%) | 6 (5.8%) | 3 (2.9%) | ||||||||

| Lu et al.36) | 3D-template | 88 (25) | 17 (19.3%) | Grade 0 (no perforation) | Grade 1 (<2 mm) | Grade 2 (≥2 and <4 mm) | Grade 3 (>4 mm) | 0 | 0 | ||

| 71 (80.7%) | 14 (15.9%) | 3 (3.4%) | 0 (0%) | ||||||||

| Kaneyama et al.47) | 3D-template | 80 (20) | 2 (2.5%) | Grade 0 (no perforation) | Grade 1 (<50% of screw diameter) | Grade 2 (>50% of screw diameter) | Grade 3 (complete perforation) | 0 | 0 | ||

| 78 (97.5%) | 2 (2.5%) | 0 (0%) | 0 (0%) | ||||||||

| Park et al.26,30,48) | Freehand | 979 (162) | 38 (3.8%) | Grade 0 (no perforation) | Grade 1 (not violating the largest diameter of VA foramen) | Grade 2 (violating the largest diameter of VA foramen) | Grade 3 (complete occlusion of VA foramen) | 0 | 0 | ||

| 941 (96.2%) | 25 (2.6%) | 5 (0.5%) | 0 | ||||||||

Abumi et al.39) and Yoshimoto et al.27) each used a conventional technique and reported a breach rate of the CPS of 6.7% and 11.1%, respectively.

Studies have demonstrated improved accuracy using image-guided navigation systems.40–44) Kotani et al.44) reported a breach rate of only 1.2% in the CT-based navigation group, which is significantly lower than the 6.7% breach rate in the lateral fluoroscopy group (P <0.01). Ito et al.43) evaluated 176 CPS cases and reported a perforation depth at the pedicle cortex of up to 2 mm in only 5 (2.8%) cases and no cortical perforation of >2 mm under 3D fluoroscopy-assistance (Iso-C3D) in all cases. Ishikawa et al.41) conducted a comparison study between lateral fluoroscopy techniques and a 3D fluoroscopy-assisted technique (Iso-C3D) and reported no difference in CPS malposition for all cortical perforations, but found superior accuracy of the Iso-C3D system for perforations ≥1 mm with statistical significance (7.3% vs. 17.5%, respectively; P <0.05). Ishikawa et al.42) additionally reported that the O-arm-based navigation system facilitated more accurate and safe CPS placement; although CPS perforation was observed even in those cases in which the O-arm system was used, most of the violations were minor (<2 mm), accounting for 8.3% of the total (9/108) CPS cases, and no significant complications were observed. In contrast, three cases of major pedicle violations (≥2 and <4 mm) were observed, accounting for 2.8% of the total cases, and such violations may cause catastrophic complications. These findings suggest that, although navigation assisted technique usually is not associated with major cortical violations and is relatively accurate, this equipment also may be related to major violations and serious complications.

Miller et al.45) conducted a comparison study between screw placement after partial laminectomy and blind screw placement in the cadaveric subaxial spine and reported a significantly lower incidence rate and severity of pedicle perforation in the partial laminectomy group versus the blind group (25% vs. 47.3%, respectively). Jo et al.46) performed 104 procedures involving subaxial CPS placement with laminoforaminotomy and reported pedicle perforation in 27.9% of the cases, of which, 8.7% of cases were >1 mm. No clinical complications were observed in all cases.

Lu et al.36) performed 88 procedures of CPS placement using a 3D-template and reported deviation of <2 mm in 14 (15.9%) cases and that of 2–4 mm in 3 (3.4%) cases. Kaneyama et al.47) reported high accuracy of CPS placement using a 3D-template in 78 of 80 (97.5%) cases.

Park et al.26,30,48) performed CPS placement via a free-hand technique and reported perforation of the pedicle wall in 38 of 979 (3.8%) cases, and no associated neurovascular complications occurred in any case; among these cases, lateral directed and Grade 1 perforations were the most common findings, including 30 of 38 (3.1%) cases in the lateral direction and 25 of 38 (2.6%) cases in Grade 1.

For higher reliability and simple comparisons among the studies, only those with more than 50 patients and a breach rate of <10% were included (Table 2). Among these, the accuracy of the free-hand technique was higher than that of the lateral fluoroscopy-guided technique (3.8% vs. 6.7%, respectively). Although the free-hand technique was not superior to the 3D fluoroscopy (Iso-C3D)-assisted technique (2.8%), it achieved comparable performance considering the advantages of the free-hand technique, and no neurovascular complications were observed in both studies.

Table 2.

Selection of studies with more than 50 patients and a breach rate <10% from Table 1

Although direct accuracy comparison among the studies was difficult to perform due to heterogeneity of patients and different settings, image-guided navigation techniques seems to be most accurate for reducing cortical perforation, especially major perforation. However, the navigation system also resulted in major complications, even though the incidence was small. These findings support that the safety and accuracy of CPS placement depends more on the surgeon’s expertise and preoperative anatomical evaluation and less on the different insertion techniques. On this basis, surgeons may improve their accuracy with advanced insertion techniques, such as the navigation systems.

Learning curve for cervical pedicle screw placement

Yoshimoto et al.49) stratified patients into three groups of Early, Middle, and Late according to the period of screw insertion, and they reported a reduction in the breach rate (12.0% [11/92], 7.0% [7/100], and 1.1% [1/88] in decreasing order) and no neurovascular injuries related to the CPS. The learning curve revealed significant improvement, especially in the late group, and the breach rate was comparable or superior to that of image-guided navigation. Those authors recommended that less-experienced surgeons should be assisted by experienced cervical spine surgeons until the technical skill for safe placement of the CPS is acquired. Heo et al.48) divided the surgical period into 1st, 2nd, 3rd, and 4th periods based on their previous results including 45, 30, 44, and 43 patients who underwent posterior cervical surgery, respectively. Out of 979 cases of planned CPS placement, perforation of the pedicle wall was observed in 38 (3.8%) cases, including 14 (5.93%) in the 1st period, seven (4.57%) cases in the 2nd period, nine (2.69%) cases in the 3rd period, and eight (3.73%) cases in the 4th period, which indicates increasing reduction of the breach rate with experience and a plateau at 3–4%. That study suggested that a minimum of 30 patients is required for safety and accuracy of CPS placement during the learning curve. In the initial learning period, the supervision of an expert and adhering to a protocol involving five steps (Fig. 5) will help to avoid complications.

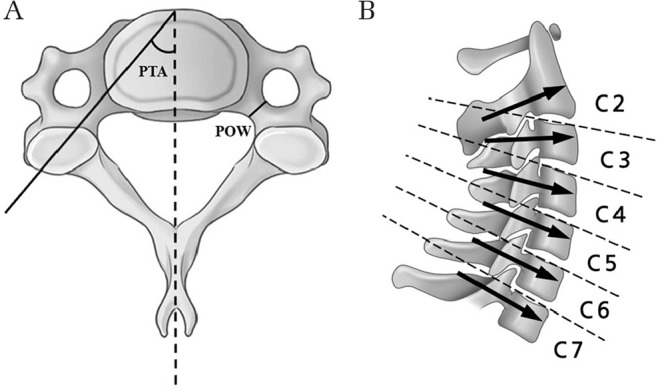

Fig. 5.

Five safety steps for avoiding neurovascular complications in the initial surgical learning period are as follows: First, the screw entry points should be determined based on a preoperative computed tomography scan. Second, small-sized and curved pedicle probes can be used to ensure a proper medial angle for screw insertion. Third, a pedicle breach can be detected using a ball-tip probe. Fourth, the cervical pedicle screw should be changed to a lateral mass screw when a breach is detected. The final step is the ability to interpret intraoperative anterior-posterior radiographs after screw insertion.

Studies reporting the learning curves30,48,49) suggested that fully trained and experienced surgeons can achieve good outcomes even without special guidance equipment. For training purposes, inexperienced surgeons should master placement of the thoracolumbar pedicle screw in real practice and practice CPS insertion using cadavers.

Neurovascular complications

Complications of subaxial CPS placement are classified into three categories: complications due to screw misplacement, complications without screw misplacement, and others.

A perforation of the lateral cortex of the pedicle may cause VA injury, resulting in severe hemorrhage and ischemia. Despite a higher frequency of minor cortical breaches, they are associated with high risk of VA injury because of the thin lateral cortex of pedicle.24,26,31)

An injury to the spinal cord or dural sac is another potential complication of screw misplacement in CPS procedures with perforation of the medial cortex, even though such cases are less frequent than perforation of the lateral cortex.50)

A nerve root injury is another potential complication of screw misplacement, especially in cases with superior or inferior screws that violate the neural foramen. In the cervical spine, the nerves that are located 1.1–1.7 mm from the inferior aspect of the cranial pedicle occupy the inferior half of the neural foramen and exit at 45° to the coronal plane and 10° to the sagittal plane.51,52) Therefore, superior CPS placement is more likely to damage the nerve root than inferior CPS placement.39,53) In such cases, surgeons should remove the misplaced screw with or without conversion to a lateral mass screw or conduct patient follow-up without screw removal according to neurologic symptoms and postoperative CT images.

An iatrogenic foraminal stenosis is a representative complication without screw misplacement. Iatrogenic foraminal stenosis can be induced by excessive reduction in spondylolisthesis and increase of tension in the spinal cord and nerve roots after correction of spinal alignment using instrumentation.54) Abumi et al.39) reported that distraction force to open the narrowing of the foramen during a reduction maneuver could effectively prevent iatrogenic complications. For reduction of this unexpected complication, Yoshimoto et al.27) recommended prophylactic foraminotomy in patients with degenerative disorders.

Other potential complications include adjacent segment degeneration, pseudoarthrosis, screw loosening, screw fracture, and wound infection.39,54)

Conclusion

Subaxial CPS placement achieves superior biomechanical stability compared to other cervical fixation techniques. Although there continues to be concern for neurovascular complications, the scope of CPS usage and efforts to decrease possible complications are increasing.

Although the accuracy of CPS placement using navigation was observed to be generally higher than other insertion methods, navigation could also be associated with complications; thus, the accuracy still depends on the surgeon’s experience and preoperative planning using CT angiography.

A review of the literature revealed that two conflicting major surgical factors, namely, a reduction of muscle pushing effect and a laterally-located entry point, could facilitate CPS placement accuracy. Higher accuracy could be achieved by making a funnel-shaped hole into the lateral mass, using the posterolateral approach for navigation, or using a specially made highly curved and small-diameter pedicle probe, all of which will serve to overcome the two major surgical factors.25,30,43)

During the initial phase of the learning curve (before 30 patients), careful preparation of surgery, reiterated identification, patterned safety steps, and supervision by the expert during surgery are necessary. Using patterned safety steps for safety purposes, we suggest primary selection or conversion to the lateral mass screw and removal or repositioning of the CPS when there is even the slightest suspicion of breach during surgery preparation or the procedure (Figs. 3 and 6).26,28,30,55)

Fig. 6.

When patterned safety steps reveal the slightest suspicion of breach during surgery preparation or the procedure, we strongly suggest the primary selection or conversion to a lateral mass screw (white arrow in A: track of pedicle probe) and removal or reposition of the cervical pedicle screw (CPS) (white arrowhead in B: trace of removed CPS).

On the basis of enough training and experience with CPS placement, advanced insertion techniques, such as the navigation system, would be helpful for improving accuracy.

Acknowledgments

The authors thank all those who were involved in the previous research of CPS.

Footnotes

Conflicts of Interest Disclosures

The authors declare that there are no conflicts of interest.

References

- 1).Abumi K, Kaneda K: Pedicle screw fixation for nontraumatic lesions of the cervical spine. Spine (Phila Pa 1976) 22: 1853–1863, 1997 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2).Anderson PA, Henley MB, Grady MS, Montesano PX, Winn HR: Posterior cervical arthrodesis with AO reconstruction plates and bone graft. Spine (Phila Pa 1976) 16: S72–S79, 1991 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3).Ilgenfritz RM, Gandhi AA, Fredericks DC, Grosland NM, Smucker JD: Considerations for the use of C7 crossing laminar screws in subaxial and cervicothoracic instrumentation. Spine (Phila Pa 1976) 38: E199–E204, 2013 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4).Jeanneret B, Magerl F, Ward EH, Ward JC: Posterior stabilization of the cervical spine with hook plates. Spine (Phila Pa 1976) 16: S56–S63, 1991 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5).Klekamp JW, Ugbo JL, Heller JG, Hutton WC: Cervical transfacet versus lateral mass screws: a biomechanical comparison. J Spinal Disord 13: 515–518, 2000 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6).An HS, Gordin R, Renner K: Anatomic considerations for plate-screw fixation of the cervical spine. Spine (Phila Pa 1976) 16: S548–S551, 1991 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7).An HS, Coppes MA: Posterior cervical fixation for fracture and degenerative disc disease. Clin Orthop Relat Res 335: 101–111, 1997 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8).Joaquim AF, Mudo ML, Tan LA, Riew KD: Posterior subaxial cervical spine screw fixation: a review of techniques. Global Spine J 8: 751–760, 2018 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9).Chon H, Park JH: Cervical vertebral body fracture with ankylosing spondylitis treated with cervical pedicle screw: a fracture body overlapping reduction technique. J Clin Neurosci 41: 150–153, 2017 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10).Kim MW, Lee SB, Park JH: Cervical spondyloptosis successfully treated with only posterior short segment fusion using cervical pedicle screw fixation. Neurol Med Chir (Tokyo) 59: 33–38, 2019 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11).Abumi K, Itoh H, Taneichi H, Kaneda K: Transpedicular screw fixation for traumatic lesions of the middle and lower cervical spine: description of the techniques and preliminary report. J Spinal Disord 7: 19–28, 1994 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12).Abumi K: Cervical spondylotic myelopathy: posterior decompression and pedicle screw fixation. Eur Spine J 24: 186–196, 2015 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13).Garfin SR, Eismont FJ, Bell GR, Bono CM, Fischgrund JS: Rothman-Simeone and Herkowitz’s the spine. 7th ed New York, Elsevier, 2018 [Google Scholar]

- 14).Kowalski JM, Ludwig SC, Hutton WC, Heller JG: Cervical spine pedicle screws: a biomechanical comparison of two insertion techniques. Spine (Phila Pa 1976) 25: 2865–2867, 2000 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15).Kotani Y, Cunningham BW, Abumi K, McAfee PC: Biomechanical analysis of cervical stabilization systems: an assessment of transpedicular screw fixation in the cervical spine. Spine (Phila Pa 1976) 19: 2529–2539, 1994 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16).Johnston TL, Karaikovic EE, Lautenschlager EP, Marcu D: Cervical pedicle screws vs. lateral mass screws: uniplanar fatigue analysis and residual pullout strengths. Spine J 6: 667–672, 2006 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17).Chazono M, Soshi S, Inoue T, Kida Y, Ushiku C: Anatomical considerations for cervical pedicle screw insertion: the use of multiplanar computerized tomography reconstruction measurements. J Neurosurg Spine 4: 472–477, 2006 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18).Liu J, Napolitano JT, Ebraheim NA: Systematic review of cervical pedicle dimensions and projections. Spine (Phila Pa 1976) 35: E1373–E1380, 2010 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19).Ludwig SC, Kramer DL, Vaccaro AR, Albert TJ: Transpedicle screw fixation of the cervical spine. Clin Orthop Relat Res 359: 77–88, 1999 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20).Nishinome M, Iizuka H, Iizuka Y, Takagishi K: An analysis of the anatomic features of the cervical spine using computed tomography to select safer screw insertion techniques. Eur Spine J 22: 2526–2531, 2013 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21).Onibokun A, Khoo LT, Bistazzoni S, Chen NF, Sassi M: Anatomical considerations for cervical pedicle screw insertion: the use of multiplanar computerized tomography measurements in 122 consecutive clinical cases. Spine J 9: 729–734, 2009 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22).Panjabi MM, Duranceau J, Goel V, Oxland T, Takata K: Cervical human vertebrae: quantitative three-dimensional anatomy of the middle and lower regions. Spine (Phila Pa 1976) 16: 861–869, 1991 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23).Sakamoto T, Neo M, Nakamura T: Transpedicular screw placement evaluated by axial computed tomography of the cervical pedicle. Spine (Phila Pa 1976) 29: 2510–2514; discussion 2515, 2004 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24).Karaikovic EE, Daubs MD, Madsen RW, Gaines RW: Morphologic characteristics of human cervical pedicles. Spine (Phila Pa 1976) 22: 493–500, 1997 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25).Abumi K, Ito M, Sudo H: Reconstruction of the subaxial cervical spine using pedicle screw instrumentation. Spine (Phila Pa 1976) 37: E349–E356, 2012 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26).Park JH, Jeon SR, Roh SW, Kim JH, Rhim SC: The safety and accuracy of freehand pedicle screw placement in the subaxial cervical spine: a series of 45 consecutive patients. Spine (Phila Pa 1976) 39: 280–285, 2014 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27).Yoshimoto H, Sato S, Hyakumachi T, Yanagibashi Y, Masuda T: Spinal reconstruction using a cervical pedicle screw system. Clin Orthop Relat Res 431: 111–119, 2005 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28).Hacker AG, Molloy S, Bernard J: The contralateral lamina: a reliable guide in subaxial, cervical pedicle screw placement. Eur Spine J 17: 1457–1461, 2008 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29).Lee DH, Lee SW, Kang SJ, et al. : Optimal entry points and trajectories for cervical pedicle screw placement into subaxial cervical vertebrae. Eur Spine J 20: 905–911, 2011 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30).Lee S, Seo J, Lee MK, et al. : Widening of the safe trajectory range during subaxial cervical pedicle screw placement: advantages of a curved pedicle probe and laterally located starting point without creating a funnel-shaped hole. J Neurosurg Spine 27: 150–157, 2017 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31).Yukawa Y, Kato F, Ito K, et al. : Placement and complications of cervical pedicle screws in 144 cervical trauma patients using pedicle axis view techniques by fluoroscope. Eur Spine J 18: 1293–1299, 2009 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32).Komatsubara T, Tokioka T, Sugimoto Y, Ozaki T: Minimally invasive cervical pedicle screw fixation by a posterolateral approach for acute cervical injury. Clin Spine Surg 30: 466–469, 2017 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33).Holly LT, Foley KT: Percutaneous placement of posterior cervical screws using three-dimensional fluoroscopy. Spine (Phila Pa 1976) 31: 536–540; discussion 541, 2006 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34).Sugimoto Y, Ito Y, Shimokawa T, Shiozaki Y, Mazaki T: Percutaneous screw fixation for traumatic spondylolisthesis of the axis using iso-C3D fluoroscopy-assisted navigation (case report). Minim Invasive Neurosurg 53: 83–85, 2010 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35).Lu T, Liu C, Dong J, Lu M, Li H, He X: Cervical screw placement using rapid prototyping drill templates for navigation: a literature review. Int J Comput Assist Radiol Surg 11: 2231–2240, 2016 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36).Lu S, Xu YQ, Lu WW, et al. : A novel patient-specific navigational template for cervical pedicle screw placement. Spine (Phila Pa 1976) 34: E959–E966, 2009 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37).Ludwig SC, Kramer DL, Balderston RA, Vaccaro AR, Foley KF, Albert TJ: Placement of pedicle screws in the human cadaveric cervical spine: comparative accuracy of three techniques. Spine (Phila Pa 1976) 25: 1655–1667, 2000 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38).Theologis AA, Burch S: Safety and efficacy of reconstruction of complex cervical spine pathology using pedicle screws inserted with stealth navigation and 3D image-guided (O-Arm) technology. Spine (Phila Pa 1976) 40: 1397–1406, 2015 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39).Abumi K, Shono Y, Ito M, Taneichi H, Kotani Y, Kaneda K: Complications of pedicle screw fixation in reconstructive surgery of the cervical spine. Spine (Phila Pa 1976) 25: 962–969, 2000 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40).Chachan S, Bin Abd Razak HR, Loo WL, Allen JC, Shree Kumar D: Cervical pedicle screw instrumentation is more reliable with O-arm-based 3D navigation: analysis of cervical pedicle screw placement accuracy with O-arm-based 3D navigation. Eur Spine J 27: 2729–2736, 2018 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41).Ishikawa Y, Kanemura T, Yoshida G, Ito Z, Muramoto A, Ohno S: Clinical accuracy of three-dimensional fluoroscopy-based computer-assisted cervical pedicle screw placement: a retrospective comparative study of conventional versus computer-assisted cervical pedicle screw placement. J Neurosurg Spine 13: 606–611, 2010 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42).Ishikawa Y, Kanemura T, Yoshida G, et al. : Intraoperative, full-rotation, three-dimensional image (O-arm)-based navigation system for cervical pedicle screw insertion. J Neurosurg Spine 15: 472–478, 2011 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43).Ito Y, Sugimoto Y, Tomioka M, Hasegawa Y, Nakago K, Yagata Y: Clinical accuracy of 3D fluoroscopy-assisted cervical pedicle screw insertion. J Neurosurg Spine 9: 450–453, 2008 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44).Kotani Y, Abumi K, Ito M, Minami A: Improved accuracy of computer-assisted cervical pedicle screw insertion. J Neurosurg 99: 257–263, 2003 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45).Miller RM, Ebraheim NA, Xu R, Yeasting RA: Anatomic consideration of transpedicular screw placement in the cervical spine: an analysis of two approaches. Spine (Phila Pa 1976) 21: 2317–2322, 1996 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46).Jo DJ, Seo EM, Kim KT, Kim SM, Lee SH: Cervical pedicle screw insertion using the technique with direct exposure of the pedicle by laminoforaminotomy. J Korean Neurosurg Soc 52: 459–465, 2012 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47).Kaneyama S, Sugawara T, Sumi M: Safe and accurate midcervical pedicle screw insertion procedure with the patient-specific screw guide template system. Spine (Phila Pa 1976) 40: E341–E348, 2015 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48).Heo Y, Lee SB, Lee BJ, et al. : The learning curve of subaxial cervical pedicle screw placement: how can we avoid neurovascular complications in the initial period? Oper Neurosurg (Hagerstown) 17: 603–607, 2019 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49).Yoshimoto H, Sato S, Hyakumachi T, Yanagibashi Y, Kanno T, Masuda T: Clinical accuracy of cervical pedicle screw insertion using lateral fluoroscopy: a radiographic analysis of the learning curve. Eur Spine J 18: 1326–1334, 2009 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50).Tomasino A, Parikh K, Koller H, et al. : The vertebral artery and the cervical pedicle: morphometric analysis of a critical neighborhood. J Neurosurg Spine 13: 52–60, 2010 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51).Pech P, Daniels DL, Williams AL, Haughton VM: The cervical neural foramina: correlation of microtomy and CT anatomy. Radiology 155: 143–146, 1985 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52).Xu R, Kang A, Ebraheim NA, Yeasting RA: Anatomic relation between the cervical pedicle and the adjacent neural structures. Spine (Phila Pa 1976) 24: 451–454, 1999 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53).Ghori A, Le HV, Makanji H, Cha T: Posterior fixation techniques in the subaxial cervical spine. Cureus 7: e338, 2015 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54).Nakashima H, Yukawa Y, Imagama S, et al. : Complications of cervical pedicle screw fixation for nontraumatic lesions: a multicenter study of 84 patients. J Neurosurg Spine 16: 238–247, 2012 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55).Park JH, Roh SW, Rhim SC: A single-stage posterior approach with open reduction and pedicle screw fixation in subaxial cervical facet dislocations. J Neurosurg Spine 23: 35–41, 2015 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]