Abstract

Background

Use of traditional and complementary medicine (T&CM) is very common among patients in sub-Saharan Africa (SSA). However, there are limited data on concurrent use of T&CM with conventional cancer therapies. In this scoping review, we sought to describe the (i) prevalence of use, (ii) types of medicine, (iii) reasons for taking T&CM, (iv) current knowledge on safety and risks, (v) characteristics of adult cancer patients who use T&CM, and (vi) perceived treatment outcomes among cancer patients undergoing conventional cancer treatment in SSA.

Methods

We conducted a systematic literature search for articles published in the English language in three scientific databases (PubMed, Embase and Web of Science). We used a scoping review approach to map relevant literature on T&CM use among cancer patients undergoing conventional cancer treatments. We assessed 96 articles based on titles and abstracts, and 23 articles based on full text. Twelve articles fulfilled preset eligibility criteria.

Results

More than half of the included articles were from only two countries in SSA: Nigeria and Uganda. Median prevalence of use of T&CM was 60.0% (range: 14.1–79.0%). Median percent disclosure of use of T&CM to attending healthcare professionals was low at 32% (range: 15.3–85.7%). The most common reasons for non-disclosure were: the doctor did not ask, the doctor would rebuke them for using T&CM, and the doctors do not know much about T&CM and so there is no need to share the issue of use with them. T&CM used by cancer patients included herbs, healing prayers and massage. Reported reasons for use of T&CM in 8 of 12 articles included the wish to get rid of cancer symptoms, especially pain, cure cancer, improve physical and psychological well-being, treat toxicity of conventional cancer therapies and improve immunity. There were limited data on safety and risk profiles of T&CM among cancer patients in SSA.

Conclusion

Use of traditional and complementary medicines is common among cancer patients undergoing conventional cancer treatments. Healthcare professionals caring for cancer patients ought to inquire and communicate effectively regarding the use of T&CM in order to minimize the risks of side effects from concurrent use of T&CM and biomedicines.

Keywords: traditional and complementary medicine, safety and risk profiles, cancer, conventional cancer therapy, sub-Saharan Africa

Background

In sub-Saharan Africa (SSA), traditional and complementary medicine (T&CM) is widely used for various illnesses, including diabetes, cancer, hypertension and asthma.1–5 A systematic review published in 2018 showed that patients use T&CM alone or in combination with conventional medicine, and that most of the T&CM users (55.8–100%) do not disclose use to the healthcare professionals, mainly for fear of retribution and because the healthcare professionals rarely ask patients about the use of T&CM.1 T&CM has been described by the World Health Organization (WHO) as

… the sum total of the knowledge, skills, and practices based on the theories, beliefs, and experiences traditional to different cultures, whether explicable or not, used in the maintenance of health as well as in the prevention, diagnosis, improvement or treatment of physical and mental illness.

and complementary medicine as

… a broad set of healthcare practices that are not part of that country’s own tradition or conventional medicine and are not fully integrated into the dominant health-care system.6,7

Generally, T&CM can be described as any practice that is not part of conventional western medicine, whose philosophical underpinnings are beliefs, customs and experiences traditional to a particular group of people, and which is used in the maintenance of health, prevention of illnesses, determination of causes of ill-health, and treatment of diseases and ill-health, including physical, social and mental disorders. In spite of the encouragement by the WHO since 2000 that African nations and other low- and middle-income countries (LMICs) should embrace T&CM, several nations in SSA have not incorporated T&CM into their national health systems, mainly because of concerns over a lack of evidence on efficacy, effectiveness and risks of T&CM.6 The Beijing Declaration of 2008 further emphasized the need for the LMICs and other nations to develop regulatory frameworks, promote research and incorporate T&CM into their national health systems in order to improve access to affordable healthcare to the populations.7,8 However, only a few nations in SSA, including the United Republic of Tanzania, South Africa, Sierra Leone, Ghana, Ethiopia and Cameroon, have thus far incorporated T&CM into their national health systems and developed policies and regulations regarding their use.9–11 Inadequate understanding of T&CMs used by patients clearly poses risks to their health. Similarly, inadequate knowledge by healthcare professionals on the mechanisms of action of T&CMs and drug/herb interactions,because there are only a few medical schools that teach aspects of T&CM, does not make things any better for the general population that uses T&CM. Indeed, there is a low (19.6%) level of knowledge of T&CM among medical students and biomedical healthcare workers in Africa.12

The incidence of cancers has increased significantly worldwide, but more so in the LMICs, especially those in SSA.13–16 The majority of cancer patients in SSA are diagnosed in advanced stages,17–19 experience poor survival20–22 and often report the use of T&CM, alone or in combination with conventional cancer therapies. For example, in Nigeria 34.5–65% of cancer patients used T&CM, while in Ghana and Ethiopia the prevalence of use of T&CM reached 73.5% and 79.0%, respectively.3,23-25 In Uganda, 55–77% of cancer patients at the Uganda Cancer Institute used T&CM concurrently with conventional cancer therapies.26,27 There are, however, limited data on the extent and trend in use of T&CM among cancer patients undergoing conventional cancer therapies in most SSA countries. There are also limited data on the types of T&CM used, and evidence of efficacy, effectiveness and risk associated with the use of each type of T&CM commonly used by cancer patients in SSA. There are some data to show that several side effects have been reported with the use of T&CM, including liver fibrosis, anemia, hyponatremia, bloody diarrhea and vaginal bleeding.28–31 It is generally difficult to know which patients have developed particular reactions as a result of T&CM use because a large proportion of patients who use T&CM rarely inform their physicians about concurrent T&CM use.27,32 The possibility of side effects and potential interactions between T&CM and western medicines makes it imperative that primary healthcare providers gain interest, knowledge and positive attitudes towards T&CM, and conduct well-designed scientific research to understand the pharmacodynamics and pharmacokinetics of T&CM in order to determine their safety and risk profiles. There is evidence that the use of T&CM is associated with interactions with conventional medicine, serious side effects and poor quality of life among cancer patients.33 However, this evidence is lacking for most T&CMs commonly used by cancer patients in SSA. The majority of the few primary studies on T&CM use among cancer patients in SSA had small sample sizes, included one of several cancers, and were heterogeneous in respect of the tools used in data collection as well as analysis approaches.

This scoping review sought to answer the following question: Among adult cancer patients undergoing conventional cancer treatment in sub-Saharan Africa, what is/are the (i) current extent of use of T&CM, (ii) types of T&CM in common use, (iii) reasons for using T&CM, (iv) current knowledge on the safety and risks of use of T&CM, (v) characteristics of the adult cancer patients who concurrently use T&CM, and (vi) perceived treatment outcomes? The results of this synthesis of evidence on T&CM use by cancer patients in SSA are expected to guide policy makers on the need for and process of integration of T&CM and conventional biomedical systems; inform the development and revision of medical school curricula in SSA countries; guide researchers on the appropriate investigations regarding T&CM, including characterization of the users, drivers of use, types of T&CM commonly used, patterns of use, efficacious and effective T&CMs, side effects from direct use and from interaction of T&CM with biomedical agents; and improve knowledge and attitudes of biomedical healthcare professionals towards the use of T&CM by their patients.

Methods

Study Design

This is a scoping review aimed at generating knowledge on the current state of use, nature and extent of research conducted, and gaps in knowledge regarding the use of T&CM among adult cancer patients in SSA. We conducted a scoping review because this approach to knowledge synthesis allows the inclusion of studies with different designs conducted over time to be comprehensively collated, summarized and interpreted to gain insights into the phenomenon under investigation, thereby informing interventions and research to improve outcomes. In particular, scoping reviews have been found to be suitable for synthesis of evidence in emerging fields where diversities of research methodologies have been used to define the landscape through a six-stage framework. The six-stage framework approach to scoping reviews includes identification of research questions, searching for relevant studies, selecting studies based on predetermined criteria, charting the studies, collating and summarizing findings, and consultations with relevant stakeholders to validate study findings.34 In this study, we did not include the sixth stage of consultation with stakeholders. However, our analyses and interpretations was informed by our own work in the field of T&CM, during which we interacted with a diversity of stakeholders.27,35-38

Eligibility Criteria and Search Strategies

Inclusion Criteria

Studies were included in this review if they fulfilled the following criteria: (i) published in a peer-reviewed journal; (ii) published in the English language; (iii) original research article on the use of T&CM by adult cancer patients (aged 18 years and above) with any cancer types; (iv) the cancer patients in the study self-reported using at least one type of T&CM and were undergoing any of the known conventional cancer therapies, including chemotherapy, radiotherapy, surgery and palliative care; (v) the study design was stated and used either a quantitative or qualitative approach; (vi) data collection was carried out solely in a country in SSA; and (vii) the study outcome explicitly included the prevalence of use of T&CM and other aspects of use related to the cancer diagnosis.

Exclusion Criteria

Studies were excluded from this review if they were: (i) published before 1st January 2000 or after 1st December 2019; and (ii) dissertations, theses or books.

Search Strategies

The study team discussed the proposed study, formulated the study questions and objectives, defined the issues of concern and identified key search terms. The search terms were developed based on each of the research questions guiding the review. An experienced medical librarian (AAK) conversant with systematic reviews, scoping reviews and literature search in the health and social sciences guided the formulation of the search terms. The librarian conducted the literature search for this scoping review. Three databases were searched: PubMed, Embase and Web of Science. The search terms, databases, dates of last search and number of articles retrieved from each database are detailed in Table 1.

Table 1.

Search Terms and Databases Searched

| Database, Search Date | Search Terms | Number of Articles Retrieved |

|---|---|---|

| PubMed, 1st December 2019 | “Traditional medicine” OR “Complementary medicine” OR “Alternative medicine” OR Medicine, traditional[MeSH Terms] OR “Indigenous Medicine” OR Medicine, Indigenous[MeSH Terms] OR “African traditional medicine” OR “Complementary therapies” OR “Complimentary therapy” OR “Complementary Medicine” OR “Integrative Medicine” AND “Conventional treatment” OR “Conventional medicine” OR “Allopathic medicine” OR “Bio medicine” OR Bio-medicine OR “Modern medicine” OR “Western medicine” AND Cancer* OR neoplas* OR carcinoma OR malignan* OR tumour OR tumor AND Adult* AND “Sub Saharan Africa” OR Sub-Saharan Africa OR “Africa South of the Sahara” OR SSA OR Cameroon OR “Central African Republic” OR Chad OR Congo OR “Democratic Republic of Congo” OR DRC OR “Equatorial Guinea” OR Gabon OR Sao “Tome and Principe” OR Burundi OR Djibouti OR Eritrea OR Ethiopia OR Kenya OR Rwanda OR Somalia OR “South Sudan” OR Sudan OR Tanzania OR Uganda OR Angola OR Botswana OR Lesotho OR Malawi OR Mozambique OR Namibia OR “South Africa” OR Swaziland OR Zambia OR Zimbabwe OR Benin OR Burkina Faso OR “Cabo Verde” OR “Cape Verde” OR “Ivory Coast” OR Gambia OR Ghana OR Guinea OR Guinea-Bissau OR Liberia OR Mali OR Mauritania OR Niger OR Nigeria OR Senegal OR “Sierra Leone” OR Togo AND PUBD: 01/01/2000–01/12/2019 |

8 |

| Web of Science, 1st December 2019 | TS=((Traditional OR Complementary OR alternative OR indigenous OR “African traditional” OR integrative) AND (medicine OR therap* OR treatment)) AND TS=((Conventional OR allopathic OR modern OR western) AND (medicine OR treatment) OR Bio medicine OR Bio-medicine) AND TS=(Cancer* OR tumor OR tumour OR carcinoma OR malignan* OR neoplas*) AND TS=(Adult* OR “grown up” OR “18 years and above” OR mature) AND TS=(Sub Saharan Africa OR Sub-Saharan Africa OR SSA OR Cameroon OR Central African Republic OR Chad OR Congo OR Democratic Republic of Congo OR DRC OR Equatorial Guinea OR Gabon OR Sao Tome and Principe OR Burundi OR Djibouti OR Eritrea OR Ethiopia OR Kenya OR Rwanda OR Somalia OR South Sudan OR Sudan OR Tanzania OR Uganda OR Angola OR Botswana OR Lesotho OR Malawi OR Mozambique OR Namibia OR South Africa OR Swaziland OR Zambia OR Zimbabwe OR Benin OR Burkina Faso OR Cabo Verde OR Cape Verde OR Ivory Coast OR Gambia OR Ghana OR Guinea OR Guinea-Bissau OR Liberia OR Mali OR Mauritania OR Niger OR Nigeria OR Senegal OR Sierra Leone OR Togo) AND PUBD: 01/01/2000–01/12/2019 |

10 |

| EMBASE, 1st December 2019 | ((Traditional OR Complementary OR alternative OR indigenous OR African traditional OR integrative) AND (medicine OR therap* OR treatment)) | 78 |

| AND | ||

| ((Conventional OR allopathic OR modern OR western AND (medicine OR treatment) OR Bio medicine OR Bio-medicine) AND Cancer* OR tumor OR tumour OR carcinoma OR malignan* OR neoplas* AND Adult* OR “grown up” OR “18 years and above” OR mature AND “Sub Saharan Africa” OR “Sub-Saharan Africa” OR Cameroon OR “Central African Republic” OR Chad OR Congo OR “Democratic Republic of Congo” OR DRC OR “Equatorial Guinea” OR Gabon OR “Sao Tome and Principe” OR Burundi OR Djibouti OR Eritrea OR Ethiopia OR Kenya OR Rwanda OR Somalia OR “South Sudan” OR Sudan OR Tanzania OR Uganda OR Angola OR Botswana OR Lesotho OR Malawi OR Mozambique OR Namibia OR “South Africa” OR Swaziland OR Zambia OR Zimbabwe OR Benin OR “Burkina Faso” OR “Cabo Verde” OR “Cape Verde” OR “Ivory Coast” OR Gambia OR Ghana OR Guinea OR Guinea-Bissau OR Liberia OR Mali OR Mauritania OR Niger OR Nigeria OR Senegal OR “Sierra Leone” OR Togo AND PUBD: 01/01/2000–01/12/2019 |

In addition to the articles retrieved based on the search terms in Table 1, the authors reviewed the bibliographies of included articles for relevant references. Relevant articles identified from references of included articles were included for evaluation.

Statistical Analyses

We did not conduct statistical analyses on the data, mainly because of the heterogeneity of the study designs. Mean ages and standard deviations are reported as per each article without further synthesis. Medians were determined for prevalence of use and disclosure of use to healthcare professionals, and reported with their respective ranges (Table 2). Arithmetic means for prevalence and disclosure of use have not been calculated as these are often influenced by outliers or extreme values.

Table 2.

Studies Included in the Scoping Review

| First Author and Year of Publication | Study Design and Data Collection Approach, Sample Size and Sex of Participants | Prevalence of Use of T&CM and Disclosure of Use to HCP | Types of T&CM Used# | Reasons for Using T&CM | Characteristics of Users Significantly Associated with T&CM Use | Reported Satisfaction or Disappointment with T&CM Use | Country |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Asuzu et al, 2017,24 | (a) Cross-sectional study. N = 400 patients Female = 76.2% (n=305); Mean age = 50.9±14.6 years; (b) Focus Group Discussions (FGD) Cancer sites: Various cancers including breast (33.5%) and cervix (32.5%). |

Prevalence use = 34.5% No results of disclosure or nondisclosure |

Not reported | Desire to be healed and get rid of pains, Recommendations by friends and relatives, Orthodox medicine expensive and no provisions for delayed or part payment; Perceived attacks from the devil or evil spirits causing illness, Fear of surgery, Unawareness about the illness, Breakdown of facilities |

Not reported | T&CM not effective reported by 70.1% of users. No particular side effects or perceived risks reported in the study. |

Nigeria |

| Ezeome et al, 2007,3 | Cross-sectional study. N = 160 patients Female = 57.5% (n=94) Mean age = 52.3 years Cancer sites: Various cancers. |

Prevalence use = 65.0% (n=104) Disclosed use = 32.7% |

Herbs (51.9%) Healing prayers (39.4%) Aloe vera (23.1%) Forever living products (16.3%) Meditation (6.7%) Python fat (7.7%) Black stone (12.5%) Medicinal tea (14.4%) Special diet (6.7%) Chinese medicines (8.7%) |

Directly treat/cure cancer, Do something to the cancer, Improve physical wellbeing, Improve psychological and emotional wellbeing. |

Use associated with: Male sex, No association with: Age, Marital status, Level of education, Religion and Cancer site. |

Specific benefits: No benefits reported by 63.4% (n=70); 79.8% would not want to use T&CM again. 23.1% (n=26) were satisfied with T&CM use and 16.3% would recommend T&CM use. Side effects 21.2% reported side effects including slimming, weakness, malaise, generalized body discomfort, diarrhea, and cough. |

Nigeria |

| Aliyu et al, 2017,48 |

Cross-sectional survey. N = 240 patients. Females = 56.2% Mean age = 45±13.7 years Cancer types: Various including cervical cancer (33.3%), Breast (22.1%), and Head/neck cancers (15.8%) |

Prevalence = 66.3% (159/240) Disclosed use = 15.3% |

Prayers = 30.8% (n=49) Herbal medicines = 28.3% (n=45) Scarification = 10.0% (n=17) |

Potentiate conventional cancer treatment 37.1% (n=59) More affordable = 18.9% (n=30) Readily available = 25.1% (n=40) Reduces nausea and vomiting = 11.9% (n=19) |

Use associated with: Male sex (OR=1.83; 95% CI: 1.02 – 3.25), and Absence of comorbidities (OR=0.32; 95% CI: 0.18 – 0.57). |

Benefits: 64.2% reported no benefits from use. Improved appetite (10.1%, n=16) Reduced pain (6.9%, n=11) Adverse reactions: Users reported Diarrhea (44.2%, n-106) Nausea and Vomiting (52.5%, n=126) Itching (30.4%, n=73) Skin rashes (9.3%, n=22) Headaches (7.1%, n=17) |

Nigeria |

| Yarney et al, 2013,25 |

Cross-sectional survey. N = 98 patients. Females = 51%. Mean age = 55.5±17.1 years. |

Prevalence use = 73.5% Disclosed use = 16.7%. |

Massage = 66.3% Herbal = 59.2% Mega vitamins = 55.1% Chinese medicines = 53.1% Prayer = 42.9% |

Try anything = 31.2% Faith/beliefs = 21.9% Sickness is spiritual = 15.6% Toxicity of conventional treatment = 9.4% Conventional doctors are mechanical to the patient = 12.5% Disappointed with conventional treatment = 9.4% |

Use associated with: Young age, Being married, Higher level of education, Being female, Undergoing palliative care. No association with: Sex and cancer site. |

Benefits Fight cancer = 40.6% Relieve severity of the cancer = 23.2% Relaxation or sleep = 17.4% Improve emotional and physical well-being = 14.5% Adverse effects: Gastric upset Nausea and vomiting Diarrhea Itching Headaches |

Ghana |

| Kiwanuka et al, 2018,26 | Cross-sectional study. N = 235 patients Breast cancer only Female only |

Prevalence use = 77% | Herbal = 22.0% Prayer = 20.0% Vitamins = 13.8% Native healers = 8.2% Chinese medicines = 5.5% |

Not reported | Use associated with: Dissatisfaction with conventional therapy (Odds ratio 2.15) | Not reported | Uganda |

| Mwaka et al, 2019,27 | Cross-sectional study. N = 434 patients Female = 81.9% (352/) Mean age = 49.2±12.2 years Cancer sites: Breast (71.9%), Stomach (4.1%), Esophagus (8.3%), Colorectal (15.1%) |

Prevalence use = 55.6% Disclosed use = 38.7% |

Extracts from leaves = 45.4% Bottled mixed liquids = 43.3% Prayers = 28.8% Extracts from roots = 25.0% Dry power herbs = 17.9% Chinese medicines = 10.4% |

Cure cancer = 68.3% Improve immunity = 35.6% Relieve pain = 31.2% Reduce cancer symptoms = 19.5% Treat side effects of chemotherapy = 16.8% Prevent cancer = 8.6% Potentiate chemotherapy = 6.6% |

Use associated with: Advanced stage cancer, Being divorced or separated, No association with: Sex, age, education, and cancer site. |

No report on perceived benefits, risks or side effects of T&CM | Uganda |

| Kiraki et al, 2019,42 |

Cross-sectional study. N = 117 patients Female= 53.8% Age: ≥16 years Cancer sites: Various including breast (13.7%) and cervix (12.8%) |

Prevalence use = 47.9% Disclosed use = 85.7% |

Spiritual therapy (37.5%, n=21) Vitamins and supplements (26.5%, n=15) Herbs (19.6%, n=11) Chinese herbs (12.5%, n=7) |

Cure of cancer = 78.6% Improve immunity = 44.6% Relieve cancer symptoms = 44.6% Manage pain = 23.2% |

No association with: Age, education, total household income, marital status, religion, residence. |

Benefits: Improved health (53.6%) Improved ability to cope (28.6%) Side effects No T&CM user reported adverse effects |

Kenya |

| Aziato et al, 2015,49 | Exploratory qualitative study. N = 12 patients All female Age: 31 – 60 years Cancer site: Breast |

Prevalence of use = 33.3% | Prayers = 8.3% Herbs = 25.0% |

Avoid mastectomy | Not applicable | Benefits: Preserved femininity and sex life Avoid ridicule from men Side effects No report on perceived adverse effects of T&CM |

Ghana |

| Erku et al, 2016,23 | Cross-sectional study. N = 195 Female = 54.3% Age: ≥18 years Cancer sites: Various including breast (37.9%) |

Prevalence of use = 79.0% Disclosed use = 20.8% |

Herbs = 72.1% Special foods = 38.9% Spiritual healing = 36.4% Dietary supplements = 22.1% |

Belief in advantages = 73.4% Dissatisfaction with conventional therapy = 14.9% Family tradition = 13.0% Emotional support = 11.0% Boost immunity = 8.4% |

Use associated with: Higher income, Tertiary education, Presence of comorbidity, Advanced stage cancer. |

Benefits: 49.3% (n=76) reported satisfaction with use 9.7% (n=15) were dissatisfied with use Adverse effects: 81.8% (n=126) of users reported no adverse effects from T&CM. |

Ethiopia |

| Ong’udia et al, 2019,40 |

Cross-sectional study. N = 78 patients Female = 55.1% Age: ≥18 years Cancer site: Various including breast (29.5%) |

Prevalence of use = 14.1% Disclosed use = 55.0% |

Herbs = 91.0% Faith healing = 54.5% Divination = 36.3% Massage = 27.3% |

Restore hope = 73.0% Psychological comfort = 82.0% Increase quality of life = 82.0% Boost immunity = 73.0% Cure of disease = 64% Symptoms relief = 36% |

No association with: Age, Sex, Education, Marital status, Religion, Level of income. |

Benefit: 54.5% (n=5) of users satisfied with T&CM use 55.0% disappointed with use because use did not meet their expectations. 72% (n=8) of users would not recommend use. Side effects 27.0% (n=3) of users reported vomiting and urinary frequency |

Kenya |

| Nwankwo et al, 2019,50 | Cross-sectional study. N = 95 patients Female = 100.0% Mean age = 50.9±11 years Cancer sites: Gynecological including cervix (44.2%) and ovary (32.6%). |

Prevalence use = 64.3% | Herbs = 73.8% | Not reported | Use associated with: Longer time to diagnosis, Longer duration of illness symptoms, Monthly income less than expenditure. |

Not reported | Nigeria |

| De Boer et al, 2014,41 |

Cross-sectional study N = 161 patients Female = 31.1% Mean age = 34.0±7.7 years Cancer type: Kaposi sarcoma (100%) |

Prevalence use = 25.5% | Not reported | Not reported | Use associated with: Longer diagnostic delay (OR = 2.69 (95%CI: 1.17 – 6.17) |

Not reported | Uganda |

Note: a Reported percentages ≥5%.

Results

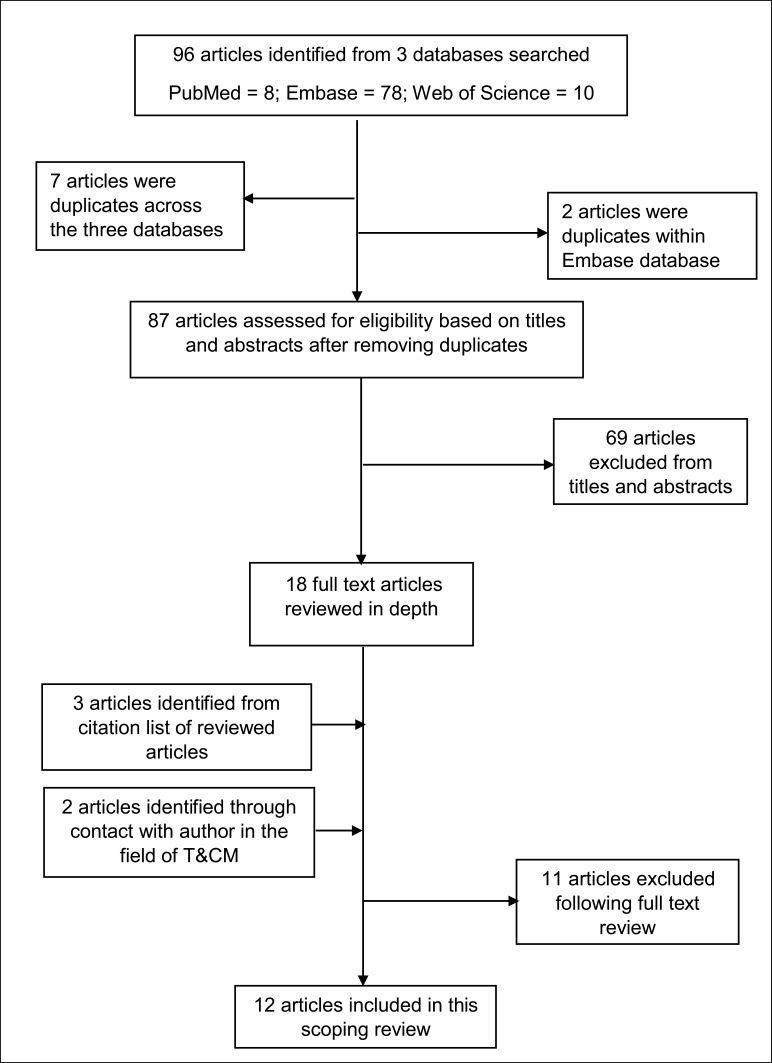

In total, 96 articles were retrieved from three databases into separate reference managers. The reference manager files (Endnotes) were merged and duplicate articles were identified; nine duplicate articles were removed. The titles and abstracts of the remaining articles were reviewed independently by ADM and CA for suitability based on the predefined inclusion criteria. Whenever there was lack of clarity regarding eligibility, all the authors read the particular articles (n=3), met and agreed by consensus based on the eligibility criteria. References of the selected articles were screened for suitable articles; three articles were added from a review of references of selected articles. ADM critically read 23 full-text articles to extract data to answer the preset research questions. Altogether, 12 full-text articles were included in this review (Figure 1). These articles contributed a sample size of 2225 cancer patients with different cancer types. The majority of the articles were from Nigeria (33.3%, n=4) and Uganda (25%, n=3) (Table 2).

Figure 1.

Study evaluation flowchart.

Prevalence of T&CM Use

The prevalence of use of T&CM varied within and across countries. The median prevalence of use of T&CM was 60.0% (range: 14.1–79.0%).

Disclosure of Use of T&CM to Healthcare Professionals

In seven of the 12 articles, there was information on disclosure of use of T&CM to the attending healthcare professionals. The median percent disclosure was 32.7%, (range: 15.3–85.7%). Again, percent disclosure varied within and between countries. Only a few articles, including those by Mwaka et al, Ong’udi et al, and Ezeome and Anarado, reported on patients’ reasons for non-disclosure.3,27,39 The most common reasons for non-disclosure were that the doctor did not ask, the doctor would rebuke them for use of T&CM, and the doctors do not know much about T&CM and so there is no need to share the issue of use with them.

Types of T&CM Used by Cancer Patients

Two of the studies included did not explicitly state the types of T&CM used by their study participants. In the other ten studies, the T&CMs used by cancer patients included herbs of various types, healing prayers or spiritual approaches, divination, massage, meditation and animal products e.g. python fat. The reported prevalence of use of each product varied among the studies. In general, herbal products comprising various plant parts prepared in different forms constituted the most common herbal medicinal products in use.

Reasons for Use of T&CM

In eight of the 12 articles, the authors reported on the reasons for cancer patients using T&CM. The reasons were many and varied, including the wish to get rid of cancer symptoms, especially pain, treat/cure cancer, improve physical and psychological well-being, treat toxicity of conventional cancer therapies and improve immunity. Fear of surgery, concern with the devil’s influence in the disease process and the high cost of conventional cancer therapies were also reported reasons for the use of T&CM (Table 2).

Safety and Risks of T&CM Among Cancer Patients

We did not find any studies that objectively evaluated safety and risk profiles of T&CM use among cancer patients in SSA. However, there were reports on perceived benefits and side effects of T&CM use. Perceived benefits from T&CM use included improved appetite, reductions in pain and other cancer symptoms, relaxation and improved sleep, improved emotional and physical well-being, improved ability to cope with illness, and preserved femininity and sex life. Perceived side effects of concern included loss of weight, general weakness and malaise, nausea and vomiting, diarrhea, itching, skin rashes, headaches and increased urinary frequency. Cancer patients who self-reported not using T&CM said they would not use them because of side effects and perceived risks to internal organs, including the kidneys and liver. In addition, patients who used T&CM but did not experience any benefits commensurate to their expectations would neither wish to use nor recommend the use of T&CM to other patients in the future.

Characteristics of Cancer Patients Who Use T&CM

There was no consistent pattern of association between particular patients’ characteristics, disease features and health system factors with the use of T&CM. Eleven of the studies included information on factors that were statistically significantly associated with the use of T&CM. While some studies found an association between sex and T&CM use, other studies did not find such associations. Other patient factors evaluated included age, marital status, educational attainment, income level and religion. Again, the associations were not consistent across studies. Disease factors evaluated included cancer site and stage at diagnosis. Cancer site was not associated with the use of T&CM in any of the studies.; however, cancer stage at diagnosis and presence of comorbidities were consistently positively associated with the use of T&CM. Similarly, studies that evaluated time to presentation and diagnosis found statistically significant associations with the use of T&CM. For example, in the study by De Boer et al,40 there was a significant association between the use of T&CM and diagnostic delay after adjusting for gender, age, income, ability to pay out of pocket and previous HIV clinic attendance (OR 2.69, p=0.020, 95% CI: 1.17–6.17).

Discussion

We found that 14.1–79.0% of cancer patients in the included studies reported the use of T&CM for the treatment of their cancers. However, the majority of patients never disclosed the use of T&CM to their healthcare professionals. The disclosure proportion exceeded 50% in only two studies (85.7% in Monicah et al and 55.0% in Ong’udi et al).39,41 The reasons for non-disclosure included fear of rebuke and stigmatization by healthcare professionals, not being asked about T&CM use, and perceived low knowledge of healthcare professionals on T&CM and therefore there being no need to discuss it with them. A high prevalence of use of T&CM has been reported in recent review of studies on T&CM use among patients with various illnesses in low- and middle-income countries, including in SSA.1,42 Doctors and nurses in SSA need to take note of the high prevalence and low disclosure of use of T&CM among cancer patients in their care. They perhaps need to proactively engage with patients regarding the use of T&CM in order to help the patients make appropriate decisions and minimize possible side effects from concurrent use of T&CM with conventional cancer medicines. This may require that the healthcare professionals learn more about T&CM so that they can engage meaningfully with patients. Studies in medical schools in SSA reveal that the majority of medical students and their teachers are willing to accept integration of T&CM into the medical school curricula.12,35,36,43 However, only a few medical schools in SSA have incorporated aspects of T&CM into their curricula.44 Therefore, there is an urgent need to further explore the integration process in a bid to promote patient safety and harmonious relationships between the biomedical health systems and traditional health practices in SSA.

Cancer patients used T&CM for various reasons and expectations, including cure of cancers, management of cancer symptoms, boosting the immune system, improving physical and psychological well-being, fear of surgery, recommendation by friends and family, and trust in T&CM providers. The majority of the patients who derived some subjective benefits from T&CM would use them again and recommend them to other patients. The use of T&CM is therefore likely to continue alongside conventional cancer treatments, mainly because it has long been part of the culture of the people and the patients trust T&CM providers, and because of convenient methods of payment for T&CM.2,45 The studies reviewed herein showed that patients also use T&CM because of dissatisfaction with conventional medical care, fear of surgery and multiple side effects of conventional cancer medicines, and because T&CMs are readily available and cheaper than conventional medicines.23–25,46,47 T&CM practitioners often provide payment schedules that are favorable to the patients. These include part payments, payments after a favorable outcome, e.g. cure has been achieved, and payments in kind.48,49 These attractive payment schedules are not available in biomedical facilities. Improved care for cancers could involve mainstreaming the use of T&CM and increasing access to conventional cancer therapies by countries in SSA.

We found that cancer patients used several types of T&CM, including herbs, prayers, dietary supplements and vitamins.3,27,46,50 However, none of the studies evaluated patients’ perceptions of how the T&CMs they used work on cancer. A few of the studies evaluated patients’ perceptions of whether the T&CMs used benefited them or caused them unwanted effects.3,25,39,46 Insights into how these T&CMs are perceived to work, or indeed do work, could guide investigations into their mechanisms of action, active ingredients and efficacy, as well as adverse effects of the T&CMs. Efforts to counsel and/or to reverse the perceptions and beliefs of patients regarding T&CM that could be dangerous to their health, either directly or through interactions with conventional medicines, require adequate understanding of the patients’ perceived mechanism of action and benefits of particular T&CMs. Therefore, more qualitative studies are needed to explore the different types of T&CM used for treatment of cancer, and to gain insights into patients’ perceptions and beliefs regarding mechanisms of action, how benefits arise and side effect profiles of particular T&CMs.

In this review, we did not find any data on the objective assessment of safety and risk of the T&CMs used. Four of the 12 studies reviewed reported on perceived side effects of T&CM. Reported side effects included increased urinary frequency, nausea and vomiting, diarrhea, loss of weight, generalized weakness and skin rashes.3,25,39,46 Most of these symptoms could be a direct result of the cancer and/or side effects of the conventional cancer therapies, rather than side effects of T&CM. There is an urgent need for well-designed efficacy, effectiveness and safety studies on T&CM use in SSA, especially among patients with chronic diseases who are likely to use T&CM for a long enough period to develop cumulative unwanted effects.

This study has some limitations. First, we included only studies published in the English language and yet a number of countries in SSA could have used other languages, e.g. French, in their publications. Second, a systematic review with pooled analyses of data from the individual critically appraised studies could have provided deeper understanding of the subject matter. However, we chose a scoping review because there are few studies in the field of T&CM and cancer. The scoping review approach is more suitable to synthesize available knowledge and guide future studies.

Conclusion

The majority of cancer patients undergoing conventional cancer therapies in SSA use T&CMs of various types concurrently with conventional cancer therapies. The majority of cancer patients who use T&CM do not disclose the use of T&CM to the healthcare professionals providing them with conventional cancer therapies. Non-disclosure of the use of T&CM concurrently with conventional cancer treatments to the healthcare professionals potentially exposes patients to danger, including side effects of T&CM and interactions between the drugs and herbs. Cancer patients need to be encouraged to disclose the use of T&CM to their healthcare professionals, who need to be more courteous when they deal with matters of T&CM.

Acknowledgment

The authors wish to thank Professor Sunita Vohra for valuable guidance during development of research questions for this review study. We also thank the library staff who supported the literature search.

Author Contributions

All authors made substantial contributions to conception and design, acquisition of data, or analysis and interpretation of data; took part in drafting the article or revising it critically for important intellectual content; gave final approval of the version to be published; and agree to be accountable for all aspects of the work.

Disclosure

The authors report no conflicts of interest in this work.

References

- 1.James PB, Wardle J, Steel A, Adams J. Traditional, complementary and alternative medicine use in Sub-Saharan Africa: a systematic review. BMJ Global Health. 2018;3(5):e000895. doi: 10.1136/bmjgh-2018-000895 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Rutebemberwa E, Lubega M, Katureebe SK, Oundo A, Kiweewa F, Mukanga D. Use of traditional medicine for the treatment of diabetes in Eastern Uganda: a qualitative exploration of reasons for choice. BMC Int Health Hum Rights. 2013;13:1. doi: 10.1186/1472-698X-13-1 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Ezeome ER, Anarado AN. Use of complementary and alternative medicine by cancer patients at the University of Nigeria Teaching Hospital, Enugu, Nigeria. BMC Complement Altern Med. 2007;7:28. doi: 10.1186/1472-6882-7-28 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Lunyera J, Wang D, Maro V, et al. Traditional medicine practices among community members with diabetes mellitus in Northern Tanzania: an ethnomedical survey. BMC Complement Altern Med. 2016;16(1):282. doi: 10.1186/s12906-016-1262-2 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Liwa AC, Smart LR, Frumkin A, Epstein H-AB, Fitzgerald DW, Peck RN. Traditional herbal medicine use among hypertensive patients in Sub-Saharan Africa: a systematic review. Curr Hypertens Rep. 2014;16(6):437. doi: 10.1007/s11906-014-0437-9 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.WHO. Traditional Medicine Strategy 2002–2005. Geneva: World Health Organization; 2002. [Google Scholar]

- 7.WHO. WHO traditional medicine strategy: 2014–2023. Available from: http://appswhoint/iris/bitstream/10665/92455/1/9789241506090_engpdf?ua=1. Accessed March23, 2015.

- 8.WHO. Beijing declaration. 2008. Available from: http://wwwwhoint/medicines/areas/traditional/TRM_BeijingDeclarationENpdf?ua=1. Accessed March23, 2015.

- 9.Kasilo OM, Trapsida J-M, Mwikisa Ngenda C, Lusamba-Dikassa PS; régional pour l’Afrique B, Organization WH. An overview of the traditional medicine situation in the African region. Afr Health Monit. 2010:7–15. [Google Scholar]

- 10.WHO. Legal status of traditional medicine and complementary/alternative medicine: a worldwide review. 2001. Available from: https://appswhoint/medicinedocs/pdf/h2943e/h2943epdf. Accessed April10, 2020.

- 11.Republic of South Africa. Traditional health practitioners act, 2007. No. 22 of 2007. Republic of South Africa. Available from: https://wwwgovza/sites/default/files/gcis_document/201409/a22-07pdf. Accessed April10, 2020 2008.

- 12.Ameade EP, Amalba A, Helegbe G, Mohammed B. Medical students’ knowledge and attitude towards complementary and alternative medicine – a survey in Ghana. J Tradit Complement Med. 2016;6(3):230–236. doi: 10.1016/j.jtcme.2015.03.004 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Bray F, Ferlay J, Soerjomataram I, Siegel RL, Torre LA, Jemal A. Global cancer statistics 2018: GLOBOCAN estimates of incidence and mortality worldwide for 36 cancers in 185 countries. CA Cancer J Clin. 2018;68(6):394–424. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Bray F, Jemal A, Grey N, Ferlay J, Forman D. Global cancer transitions according to the Human Development Index (2008–2030): a population-based study. Lancet Oncol. 2012;13(8):790–801. doi: 10.1016/S1470-2045(12)70211-5 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Parkin DM, Bray F, Ferlay J, Jemal A. Cancer in Africa 2012. Cancer Epidemiol Biomarker Prev. 2014;23(6):953–966. doi: 10.1158/1055-9965.EPI-14-0281 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Wabinga HR, Nambooze S, Amulen PM, Okello C, Mbus L, Parkin DM. Trends in the incidence of cancer in Kampala, Uganda 1991–2010. Int J Cancer. 2014;135(2):432–439. doi: 10.1002/ijc.28661 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Mwaka AD, Garimoi CO, Were EM, Roland M, Wabinga H, Lyratzopoulos G. Social, demographic and healthcare factors associated with stage at diagnosis of cervical cancer: cross-sectional study in a tertiary hospital in Northern Uganda. BMJ Open. 2016;6(1):e007690. doi: 10.1136/bmjopen-2015-007690 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Pace LE, Mpunga T, Hategekimana V, et al. Delays in breast cancer presentation and diagnosis at two rural cancer referral centers in Rwanda. Oncologist. 2015;20(7):780–788. doi: 10.1634/theoncologist.2014-0493 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Ibrahim A, Rasch V, Pukkala E, Aro AR. Predictors of cervical cancer being at an advanced stage at diagnosis in Sudan. Int J Women Health. 2011;3:385–389. doi: 10.2147/IJWH.S21063 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Wabinga H, Ramanakumar AV, Banura C, Luwaga A, Nambooze S, Parkin DM. Survival of cervix cancer patients in Kampala, Uganda: 1995–1997. Br J Cancer. 2003;89(1):65–69. doi: 10.1038/sj.bjc.6601034 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Chokunonga E, Ramanakumar AV, Nyakabau AM, et al. Survival of cervix cancer patients in Harare, Zimbabwe, 1995–1997. Int J Cancer. 2004;109(2):274–277. doi: 10.1002/ijc.11670 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Gondos A, Brenner H, Wabinga H, Parkin DM. Cancer survival in Kampala, Uganda. Br J Cancer. 2005;92(9):1808–1812. doi: 10.1038/sj.bjc.6602540 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Erku DA. Complementary and alternative medicine use and its association with quality of life among cancer patients receiving chemotherapy in Ethiopia: a cross-sectional study. Evid Based Complement Alternat Med. 2016;2016:8. doi: 10.1155/2016/2809875 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Asuzu CC, Elumelu-Kupoluyi T, Asuzu MC, Campbell OB, Akin-Odanye EO, Lounsbury D. A pilot study of cancer patients’ use of traditional healers in the Radiotherapy Department, University College Hospital, Ibadan, Nigeria. Psycho Oncol. 2017;26(3):369–376. doi: 10.1002/pon.4033 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Yarney J, Donkor A, Opoku SY, et al. Characteristics of users and implications for the use of complementary and alternative medicine in Ghanaian cancer patients undergoing radiotherapy and chemotherapy: a cross- sectional study. BMC Complement Altern Med. 2013;13(1):16. doi: 10.1186/1472-6882-13-16 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Kiwanuka F. Complementary and alternative medicine use: influence of patients’ satisfaction with medical treatment among breast cancer patients at Uganda Cancer Institute. Adv Biosci Clin Med. 2018;6(1):24–29. doi: 10.7575/aiac.abcmed.v.6n.1p.24 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Mwaka AD, Mangi SP, Okuku FM. Use of traditional and complementary medicines by cancer patients at a national cancer referral facility in a low-income country. Eur J Cancer Care (Engl). 2019;28(6):e13158. doi: 10.1111/ecc.13158 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Nabukenya I. Acute and sun-acute toxicity of ethanolic and aqueous extracts of tephrosia vogelii, Vernonia amygdalina and Senna occidentalis in Rodents. Altern Integr Med. 2014;3(3). [Google Scholar]

- 29.Kiguba R, Ononge S, Karamagi C, Bird S. Herbal medicine use and linked suspected adverse drug reactions in a prospective cohort of Ugandan inpatients. BMC Complement Altern Med. 2016;16(145). doi: 10.1186/s12906-016-1125-x [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Auerbach B, Reynolds S, Lamorde M, et al. Traditional herbal medicine use associated with liver fibrosis in Rural Rakai, Uganda. PLoS One. 2012;7(11):e41737. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0041737 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Anywar G, Van’t Klooster C, Byamukama R, et al. Medicinal plants used in the treatment and prevention of malaria in Cegere Sub-County, Northern Uganda. Ethnobot Res Appl. 2016;14:505–516. doi: 10.17348/era.14.0.505-516 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Lubinga SJ, Kintu A, Atuhaire J, Asiimwe S. Concomitant herbal medicine and Antiretroviral Therapy (ART) use among HIV patients in Western Uganda: a cross-sectional analysis of magnitude and patterns of use, associated factors and impact on ART adherence. AIDS Care. 2012;24(11):1375–1383. doi: 10.1080/09540121.2011.648600 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Block KI. Significance of natural product interactions in oncology. Integr Cancer Ther. 2012;12(1):4–6. doi: 10.1177/1534735412467368 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Arksey H, O’Malley L. Scoping studies: towards a methodological framework. Int J Soc Res Methodol. 2005;8(1):19–32. doi: 10.1080/1364557032000119616 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Mwaka AD, Tusabe G, Garimoi CO, Vohra S, Ibingira C. Integration of traditional and complementary medicine into medical school curricula: a survey among medical students in Makerere University, Uganda. BMJ Open. 2019;9(9):e030316. doi: 10.1136/bmjopen-2019-030316 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Mwaka AD, Tusabe G, Orach Garimoi C, Vohra S. Turning a blind eye and a deaf ear to traditional and complementary medicine practice does not make it go away: a qualitative study exploring perceptions and attitudes of stakeholders towards the integration of traditional and complementary medicine into medical school curriculum in Uganda. BMC Med Educ. 2018;18(1):310. doi: 10.1186/s12909-018-1419-4 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Mwaka AD, Okello ES, Orach CG. Barriers to biomedical care and use of traditional medicines for treatment of cervical cancer: an exploratory qualitative study in northern Uganda. Eur J Cancer Care (Engl). 2015;24(4):503–513. doi: 10.1111/ecc.12211 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Abbo C, Ekblad S, Waako P, Okello E, Musisi S. The prevalence and severity of mental illnesses handled by traditional healers in two districts in Uganda. Afr Health Sci. 2009;9(2). [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Ong’udi M, Mutai P, Weru I. Study of the use of complementary and alternative medicine by cancer patients at Kenyatta National Hospital, Nairobi, Kenya. J Oncol Pharm Pract. 2019;25(4):918–928. doi: 10.1177/1078155218805543 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.De Boer C, Niyonzima N, Orem J, Bartlett J, Zafar SY. Prognosis and delay of diagnosis among Kaposi’s sarcoma patients in Uganda: a cross-sectional study. Infect Agent Cancer. 2014;9(17):1750–9378. doi: 10.1186/1750-9378-9-17 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Monicah K, Mbugua G, Mburugu R. Use of complementary and alternative medicine among cancer patients in Meru County, Kenya. Int J Prof Pract. 2019;7(1):24–33. [Google Scholar]

- 42.Hill J, Mills C, Li Q, Smith JS. Prevalence of traditional, complementary, and alternative medicine use by cancer patients in low income and lower-middle income countries. Glob Public Health. 2019;14(3):418–430. doi: 10.1080/17441692.2018.1534254 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Kazembe TC, Musekiwa M. Inclusion of traditional medicine in the school curriculum in Zimbabwe: a case study. Eurasian J Anthropol. 2011;2(2):54–69. [Google Scholar]

- 44.Chitindingu E, George G, Gow J. A review of the integration of traditional, complementary and alternative medicine into the curriculum of South African medical schools. BMC Med Educ. 2014;14(1):40. doi: 10.1186/1472-6920-14-40 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Falisse J-B, Masino S, Ngenzebuhoro R. Indigenous medicine and biomedical health care in fragile settings: insights from Burundi. Health Policy Plan. 2018;33(4):483–493. doi: 10.1093/heapol/czy002 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Aliyu UM, Awosan KJ, Oche MO, Taiwo AO, Jimoh AO, Okuofo EC. Prevalence and correlates of complementary and alternative medicine use among cancer patients in Usmanu Danfodiyo university teaching hospital, Sokoto, Nigeria. Niger J Clin Pract. 2017;20(12):1576–1583. doi: 10.4103/njcp.njcp_88_17 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Aziato L, Clegg-Lamptey JNA. Breast cancer diagnosis and factors influencing treatment decisions in Ghana. Health Care Women Int. 2015;36(5):543–557. doi: 10.1080/07399332.2014.911299 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Muela SH, Mushi AK, Ribera JM. The paradox of the cost and affordability of traditional and government health services in Tanzania. Health Policy Plan. 2000;15(3):296–302. doi: 10.1093/heapol/15.3.296 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Leonard KL, Zivin JG. Outcome versus service based payments in health care: lessons from African traditional healers. Health Econ. 2005;14(6):575–593. doi: 10.1002/hec.956 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Nwankwo TO, AJah L, Ezeome IV, Umeh UA, Aniebue UU. Complementary and alternative medicine. Use and challenges among gynaecological cancer patients in Nigeria: experiences in a tertiary health institution – preliminary results. Eur J Gynaecol Oncol. 2019;40(1):101–105. [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Data Citations

- WHO. WHO traditional medicine strategy: 2014–2023. Available from: http://appswhoint/iris/bitstream/10665/92455/1/9789241506090_engpdf?ua=1. Accessed March23, 2015.

- WHO. Beijing declaration. 2008. Available from: http://wwwwhoint/medicines/areas/traditional/TRM_BeijingDeclarationENpdf?ua=1. Accessed March23, 2015.

- WHO. Legal status of traditional medicine and complementary/alternative medicine: a worldwide review. 2001. Available from: https://appswhoint/medicinedocs/pdf/h2943e/h2943epdf. Accessed April10, 2020.

- Republic of South Africa. Traditional health practitioners act, 2007. No. 22 of 2007. Republic of South Africa. Available from: https://wwwgovza/sites/default/files/gcis_document/201409/a22-07pdf. Accessed April10, 2020 2008.