Abstract

Although the genetic architecture of amyotrophic lateral sclerosis (ALS) is incompletely understood, recent findings suggest a complex model of inheritance in ALS, which is consistent with a multistep pathogenetic process. Therefore, the aim of our work is to further explore the architecture of ALS using targeted next generation sequencing (NGS) analysis, enriched in motor neuron diseases (MND)-associated genes which are also implicated in axonal hereditary motor neuropathy (HMN), in order to investigate if disease expression, including the progression rate, could be influenced by the combination of multiple rare gene variants. We analyzed 29 genes in an Italian cohort of 83 patients with both familial and sporadic ALS. Overall, we detected 43 rare variants in 17 different genes and found that 43.4% of the ALS patients harbored a variant in at least one of the investigated genes. Of note, 27.9% of the variants were identified in other MND- and HMN-associated genes. Moreover, multiple gene variants were identified in 17% of the patients. The burden of rare variants is associated with reduced survival and with the time to reach King stage 4, i.e., the time to reach the need for percutaneous endoscopic gastrostomy (PEG) positioning or non-invasive mechanical ventilation (NIMV) initiation, independently of known negative prognostic factors. Our data contribute to a better understanding of the molecular basis of ALS supporting the hypothesis that rare variant burden could play a role in the multistep model of disease and could exert a negative prognostic effect. Moreover, we further extend the genetic landscape of ALS to other MND-associated genes traditionally implicated in degenerative diseases of peripheral axons, such as HMN and CMT2.

Keywords: motor neuron disease, lower motor neuron syndrome, nerve, neuropathy, CMT, distal SMA, hereditary neuropathy, genetics, survival, next generation sequencing

1. Introduction

Amyotrophic lateral sclerosis (ALS), also known as Lou Gehrig’s disease, is the most frequent and severe disease within the widely heterogeneous spectrum of adult-onset motor neuron diseases (MND). It is defined by the degeneration of both upper motor neurons (UMN) and lower motor neurons (LMN) in the cerebral cortex, brain stem, and spinal cord [1,2]. This leads to progressive muscle weakness, wasting, and rapidly progressive paralysis which typically causes death due to respiratory failure within three to five years after the symptom onset [1]. About 10% of ALS cases are familial (fALS), whereas the remaining 90% apparently occur sporadically (sALS) [3,4]. To date, more than 30 genes have been reproducibly implicated in ALS, while more than 120 have been proposed as potentially related to ALS, although most are still of uncertain and often not replicated significance [1,2]. In about 60–80% of fALS patients, a gene mutation can be identified, with the four major ALS genes by frequency being SOD1, C9orf72, TARDBP, and FUS [1,2,4]. While less well understood, the genetic hereditability of sALS has been estimated to be more than 60% [5] and the contribution of rare variants with intermediate to large effects is increasingly recognized in the context of an oligogenic model of the disease [2,6,7]. According to this hypothesis, each co-occurring variant alone could be tolerated but when combined with a second variant would exceed the threshold required for neurodegeneration [8]. However, genetic heterogeneity, pleiotropy, and nonpenetrance are incompletely understood issues in ALS [1,2,4,6]. Furthermore, some aspects of the ALS phenotype, are shared with other neurodegenerative, neuropsychiatric, and neuromuscular diseases, such as axonal hereditary Charcot-Marie-Tooth neuropathy (CMT2), distal hereditary motor neuropathy (dHMN), or hereditary spastic paraplegia (HSP), which could implicate similar genes in their pathology [1,2,9,10,11].

The aim of our work was to further explore the architecture of ALS by using a next generation sequencing (NGS) panel, specifically enriched in ALS and other non-ALS, MND-associated genes, involved in HMN, CMT2, and HSP, in order to investigate if disease expression, including progression rate, could be influenced by the combination of multiple rare gene variants.

2. Results

2.1. Variant Identification and Classification

The 83 study participants (Table S1) were analyzed with NGS, Sanger direct sequencing, and C9orf72 analysis. Overall, we detected and confirmed, with the Sanger technique, 43 rare or novel variants in coding or splice site regions in 17 different genes, which satisfied the predefined filter criteria.

Of the variants identified, 31 (72%) were detected in ALS genes and 12 (28%) in CMT2 and dHMN genes. Thirty-six patients (43.4% overall, 47% in fALS and 42% in sALS) carried at least one of these variants. Overall, with regard to NGS analysis, the variants distribution was as follows: 90.4% missense, 2.4% nonsense, 4.8% frameshift, and 2.4% splice site.

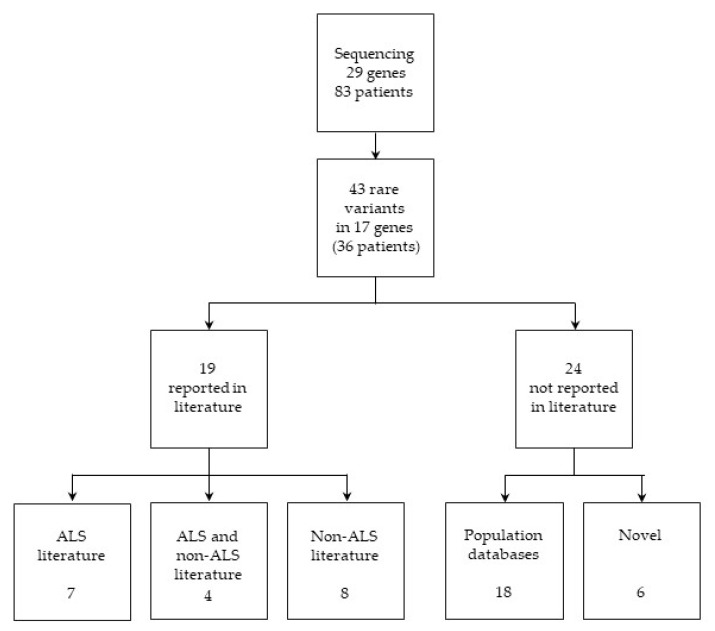

Among the detected variants, 44% of the detected variants (n = 19) were previously described in the literature: seven of them were reported in the ALS literature, four in the ALS and non-ALS literature, and eight in the non-ALS literature. The remaining 56% of the variants (n = 24) were not reported in the literature; 18 were annotated only in population databases, of which one only in the Single Nucleotide Polymorphism Database (dbSNP), while six were novel and could be considered as candidate ALS-associated variants (Figure 1 and Table 1). Rare variants, as well as clinical and demographic data of individual patients are reported in Table S2. Rare variants identified in a group of 332 non-neurological unrelated Italian patients, for whom NGS exome sequencing data were available from our in-house database, were selected as the control group (Tables S3–S5).

Figure 1.

Variant identification and classification.

Table 1.

Variants identified by next generation sequencing (NGS).

| PT-ID a | Gene Name | cDNA Change | Protein Change | dbSNP ID b | ACMG Classification | Global MAF c | Population MAF d | SIFT Score | Polyphen Score | Mutation Taster Pred | CADD |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| ALS literature | |||||||||||

| ALS_78 | ALS2 | c.1115C > G | p.Pro372Arg | rs190369242 | 3 | 0.00130 | 0.00220 | 0.64 (T) | 0.919 (D) | 0.683 (D) | 19.65 |

| ALS_6 | OPTN | c.941A > T | p.Gln314Leu | rs142812715 | 3 | 0.00017 | 0.00030 | 0.01 (D) | 0.999 (D) | 0.993 (D) | 27.70 |

| ALS_56 | SETX | c.654G > C | p.Lys218Asn | rs117861188 | 3 | 0.00033 | 0.00060 | 0.0 (D) | 0.961 (D) | 0.900 (D) | 23.80 |

| ALS_34 | SOD1 | c.203T > C | p.Leu68Pro | CM110553 | 5 | 0.00000 | 0.00000 | 0.21 (T) | 0.001 (B) | 0.99 (N) | 6.15 |

| ALS_6 | SOD1 | c.217G > A | p.Gly73Ser | rs121912455 | 5 | 0.00000 | 0.00000 | 0.0 (D) | 0.970 (D) | 0.999 (D) | 29.30 |

| ALS_23 | TBK1 | c.1190T > C | p.Ile397Thr | rs755069538 | 5 | 0.00010 | 0.00030 | 0.31 (T) | 0.039 (B) | 0.999 (D) | 22.80 |

| ALS and non-ALS literature | |||||||||||

| ALS_5 | SETX | c.59G > A | p.Arg20His | rs79740039 | 3 | 0.00683 | 0.01051 | 0.25 (T) | 0.001 (B) | 0.999 (N) | 3.43 |

| ALS_18 | SETX | c.59G > A | p.Arg20His | ||||||||

| ALS_60 | SETX | c.59G > A | p.Arg20His | ||||||||

| ALS_4 | SPG11 | c.1348A > G | p.Ile450Val | rs3759873 | 1 | 0.01672 | 0.00450 | 0.78 (T) | 0 (B) | 0.994 (D) | 6.31 |

| ALS_30 | SPG11 | c.3037A > G | p.Lys1013Glu | rs111347025 | 2 | 0.00861 | 0.01448 | 0.73 (T) | 0.002 (B) | 0.963 (D) | 22.70 |

| ALS_43 | SPG11 | c.3037A > G | p.Lys1013Glu | ||||||||

| ALS_32 | SPG11 | c.6224A > G | p.Asn2075Ser | rs140824939 | 3 | 0.00310 | 0.00489 | 0.49 (T) | 0 (B) | 0.999 (N) | 0.28 |

| Non-ALS literature | |||||||||||

| ALS_2 | BSCL2 | c.844G > A | p.Ala282Thr(218)§ | rs190842600 | 3 | 0.00022 | 0.00000 | 0.08 (T) | 1 (D) | 0.999 (D) | 25.90 |

| ALS_53 | BSCL2 | c.1033C > T | p.Arg345Trp(281)§ | rs767820877 | 3 | 0.00000 | 0.00000 | 0.02(D) | 0.987 (D) | 0.999 (D) | 21.40 |

| ALS_41 | HSPB3 | c.347G > C | p.Arg116Pro | rs150931007 | 4 | 0.00011 | 0.00010 | 0 (D) | 1 (D) | 0.999 (D) | 29.70 |

| ALS_1 | MFN2 | c.1574A > G | p.Asn525Ser | rs145654854 | 3 | 0.00017 | 0.00021 | 1 (T) | 0 (B) | 0.753 (N) | 19.62 |

| ALS_6 | SETX | c.4612C > T | p.Arg1538Trp | rs147018359 | 3 | 0.00000 | 0.00000 | 0.21 (T) | 0 (B) | 0.999 (N) | 17.31 |

| ALS_29 | SETX | c.4612C > T | p.Arg1538Trp | ||||||||

| ALS_30 | SPG11 | c.5986_5987insT | p.Cys1996Leufs*4 | rs312262775 | 5 | 0.00002 | 0.00000 | - | - | - | - |

| ALS_7 | SQSTM1 | c.352C > T | p.Pro118Ser | rs200152247 | 3 | 0.00006 | 0.00010 | 0.54 (T) | 0.009 (B) | 0.999 (D) | 20.90 |

| ALS_34 | SQSTM1 | c.802C > G | p.Leu268Val | rs753685955 | 3 | 0.00001 | 0.00000 | 1 (T) | 0.004 (B) | 0.824 (N) | 17.73 |

| Variants present only in population databases | |||||||||||

| ALS_64 | BSCL2 | c.689G > A | p.Ser230Asn (166) § | rs778378228 | 4 | 0.00001 | 0.00000 | 0.11 (T) | 0.820 (P) | 0.824 (N) | 23.40 |

| ALS_67 | BSCL2 | c.785C > T | p.Ala262Val(198) § | rs140896339 | 3 | 0.00028 | 0.00000 | 0.50 (T) | 0.085(B) | 0.999 (N) | 18.85 |

| ALS_7 | BSCL2 | c.1057T > A | p.Ser353Thr(189) § | rs769769807 | 3 | 0.00001 | 0.00000 | 0.17 (T) | 0.006 (B) | 0.999 (N) | 6.03 |

| ALS_69 | BSCL2 | c.1282C > T | p.Pro428Ser(364) § | rs369732238 | 3 | 0.00006 | 0.00010 | 0.1 (T) | 0.573 (P) | 0.905 (N) | 18.59 |

| ALS_43 | BSCL2 | c.1300T > C | p.Ser434Pro(370) § | rs199584887 | 3 | 0.00006 | 0.00000 | 0.44 (T) | 0.001 (B) | 0.999 (N) | 1.58 |

| ALS_52 | DCTN1 | c.1486G > C | p.Val496Leu | rs773897036 | 4 | 0.00002 | 0.00000 | 0.06 (T) | 0.984 (D) | 0.999 (D) | 23.50 |

| ALS_13 | DYNC1H1 | c.265G > A | p.Gly89Ser | rs749973847 | 3 | 0.00002 | 0.00000 | 0.74 (T) | 0.019 (B) | 0.999 (D) | 22.80 |

| ALS_40 | DYNC1H1 | c.3748G > A | p.Val1250Met | rs369914512 | 3 | 0.00006 | 0.00010 | 0.07 (T) | 0.978 (D) | 0.999 (D) | 29.20 |

| ALS_41 | DYNC1H1 | c.12213C > T # | p.Ile4071Ile | rs746950373 | 3 | 0.00002 | 0.00000 | 0.48 (T) | - | 1 (D) | 12.50 |

| ALS_33 | HSPB1 | c.403T > G | p.Ser135Ala | rs766728475 | 4 | 0.00002 | 0.00000 | 0.07 (T) | 0.623 (P) | 0.999 (D) | 25.40 |

| ALS_53 | HSPB3 | c.199G > A | p.Gly67Ser | rs35258119 | 3 | 0.00727 | 0.00000 | 0.2 (T) | 0.036 (B) | 0.999 (N) | 17.28 |

| ALS_4 | HSPB3 | c.346C > T | p.Arg116X | rs757339596 | 4 | 0.00003 | 0.00000 | - | - | 0.999 (D) | 11.58 |

| ALS_58 | PLEKHG5 | c.3049G > A | p.Gly1017Arg | rs755699992 | 3 | 0.00000 | 0.00000 | 0.56 (T) | 0.047 (B) | 0.999 (N) | 0.16 |

| ALS_15 | SETX | c.3182C > T | p.Pro1061Leu | rs12352982 | 3 | 0.01604 | 0.00000 | 1 (T) | 0 (B) | 0.999 (N) | 0.90 |

| ALS_46 | SETX | c.7435A > G | p.Ile2479Val | rs536912256 | 3 | 0.00006 | 0.00000 | 0.43 (T) | 0.001 (B) | 0.999 (N) | 0.76 |

| ALS_73 | SPG11 | c.1675T > A | p.Ser559Thr | rs773680273 | 3 | 0.00001 | 0.00000 | 0.2 (T) | 0.990 (D) | 0.591 (D) | 20.80 |

| ALS_27 | SPG11 | c.2764G > A | p.Val922Ile | rs139399250 | 3 | 0,00006 | 0,00010 | 0.43 (T) | 0.002(B) | 0.999 (N) | 2.25 |

| ALS_67 | SPG11 | c.6201A > T # | p.Gly2067Gly | rs764991726 | 3 | 0,00001 | 0,00000 | 1 (T) | - | 0.987 (D) | 7.48 |

| Novel candidate ALS-associated variants | |||||||||||

| ALS_34 | DYNC1H1 | c.4183A > C | p.Lys1395Gln | - | 4 | - | - | 0.12 (T) | 1.000 (D) | 0.999 (D) | 34.00 |

| ALS_22 | DYNC1H1 | c.5303G > T | p.Ser1768Ile | - | 3 | - | - | 0.1 (T) | 0.028 (B) | 0.999 (N) | 15.71 |

| ALS_27 | FIG4 | c.1030C > A | p.Pro344Thr | - | 4 | - | - | 0.37 (T) | 0.875 (P) | 0.999 (D) | 25.40 |

| ALS_21 | FUS | c.1168 + 7A > G # | - | - | 3 | - | - | - | - | - | - |

| ALS_40 | SETX | c.5852A > T | p.His1951Leu | - | 4 | - | - | 0.13 (T) | 0.961 (D) | 0.974 (D) | 25.80 |

| ALS_70 | SPG11 | c.4826delT | p.Met1609Serfs*31 | - | 4 | - | - | - | - | 1 (D) | 8.99 |

a PT-ID, patient identification code; b dbSNP150; c Global MAF, global allele counts were calculated from all subjects in the ExAc database; d MAF population, population allele count refers to European Ancestry subjects from the ExAc database; §, the variants present in BSCL2 gene has been reported the positions in both isoform NM_001122955.3 and NM_001130702.2 in bracket; #, variants predicted as splice site by in silico tools; ACMG, American College of Medical Genetics and Genomics; ACMG classification: 1 = benign, 2 = likely benign, 3 = uncertain significance, 4 = likely pathogenic, 5 = pathogenic; MAF, minor allele frequency; SIFT: T = tolerated and D = deleterious; Polyphen: B = benign, P = possibly damaging, D = damaging; Mutation Taster: D = disease causing, N = polymorphism, A = disease causing automatic; CADD, combined annotation dependent depletion; CADD scores, scaled CADD scores (Phred like) for scoring deleteriousness. Variants in common between ALS patients and controls were excluded (Table S4).

2.1.1. Variants Previously Reported in ALS Literature

Seven patients were harboring the pathogenic C9orf72 repeat expansion. Three previously reported missense variants were classified by the American College of Medical Genetics and Genomics (ACMG) criteria as pathogenic as follows: the SOD1 p.Leu68Pro and p.Gly73Ser, and the TBK1 p.Ile397Thr. Among them, the two SOD1 variants were described in both fALS and sALS cases [12,13] and in an Italian sALS case, respectively [14,15]. The TBK1 p.Ile397Thr was previously described by our group [16]. Three variants, reported in previous NGS studies, were classified as variants of uncertain significance (VUS) as follows: the ALS2 p.Pro372Arg, the OPTN p.Gln314Leu, and the SETX p.Lys218Asn [15,17,18]. Notably, we identified the BSCL2 p.Leu427Pro missense variant, previously reported in ALS literature [18], in three unrelated patients but also in nine controls, hence, this variant was excluded from this study (Tables S3 and S4).

2.1.2. Variants Previously Reported in both ALS and Non-ALS Literature

Four variants, which were identified in seven different ALS patients, have been previously reported in both the ALS and non-ALS literature. We identified the SETX p.Arg20His variant, classified as VUS, in three unrelated patients, presenting with a pyramidal, predominant upper motor neuron (PUMN), and classic phenotype, respectively. This variant has previously been identified in compound heterozygosity in patients with ataxia with oculomotor apraxia type 2 (AOA2) [19] and in patients with CMT2 [20]; however, it has also been previously reported in ALS individuals [8,15,21]. The three variants identified by our screening in the SPG11 gene have previously been reported in both ALS [15,18] and hereditary spastic paraplegia (HSP) cohorts [22]. We also identified the following two variants in ALS patients and control cases, classified by ACMG as likely pathogenic: the FIG4 p.Ile41Thr and the ERBB4 p.His374Gln (Table S4). The FIG4 p.Ile41Thr missense, originally described in compound heterozygous in demyelinating autosomal recessive CMT neuropathy type 4 juvenile (CMT4J) patients [23,24,25,26], was also subsequently reported in ALS patients, with autosomal dominant transmission [8,18,27,28]. The ERBB4 p.His374Gln missense, described in ALS [29] and cancer patients [30], was identified in one sALS and one unrelated fALS patient. These variants were excluded from our results.

2.1.3. Variants Previously Reported in Non-ALS Literature

We identified eight variants that have been previously reported in the non-ALS literature. Among them, seven variants have previously been associated with a neurological phenotype, while three variants have been associated with patients with non-neurological diseases. The SPG11 p.Cys1996Leufs*4 frameshift was classified by ACMG as pathogenic. This variant has been previously reported in compound heterozygosis in one Israeli [31] and one Italian patient [32], both presenting with autosomal recessive (AR) HSP. Similarly, we identified this variant in a classic sALS patient with SPG11 compound heterozygosity. The following six variants were classified as VUS: the MFN2 p.Asn525Ser. the BSCL2 p.Ala282Thr and p.Arg345Trp. the SETX p.Arg1538Trp. and the SQSTM1 p.Leu268Val and p.Pro118Ser. The MFN2 p.Asn525Ser, which was identified in a bulbar sALS patient, has been previously reported in a large NGS CMT study [33]. The SQSTM1 p.Leu268Val has been previously reported in one Italian patient with Alzheimer’s disease (AD) [34]; additionally, we identified another SQSTM1 variant (p.Pro118Ser), which had been previously reported in one patient with ALS, a frontotemporal dementia (FTD) patient, and in two control individuals [34,35]. The BSCL2 and SETX VUS variants have been previously reported in B-cell lymphoma [36] and cancer patients, respectively [37]. Finally, the HSPB3 p.Arg116Pro variant has recently been described in myopathy patients [38]. This variant is predicted to be deleterious by in silico programs, since it is located in the highly conserved (alfa) crystalline domain [38].

The following four variants were identified in our in-house controls and therefore were excluded from our results: the ALS2 Gly1069Glu, the MFN2 p.Arg468His, the SPG7 p.Ala510Val, and p.Arg486Gln variants. The ALS2 Gly1069Glu, which was identified in a pyramidal sALS patient, has been reported in the HSP family by a previous NGS study [39]. We identified the MFN2 p.Arg468His variant in a patient with flail arm syndrome, a restricted ALS phenotype characterized by predominant LMN involvement in upper limbs, and pes cavus (i.e., an abnormally high plantar longitudinal arch). This variant, whose pathogenicity has also been supported by functional in vitro studies [40], has been previously reported in patients with axonal CMT (CMT2) [41,42,43], although a role in demyelinating CMT (CMT1) has been more recently suggested [44,45]. The SPG7 p.Ala510Val variant has been previously reported in patients with AR HSP [46,47], whereas the p.Arg486Gln has been previously reported in both AR HSP and progressive external ophthalmoplegia (PEO) [48,49,50]. The SPG7 p.Ala510Val variant is located in a highly conserved region and its pathogenicity has been previously supported in a yeast model [51].

2.1.4. Variants Present Only in Population Databases

Eighteen variants were not reported in the literature but were recorded in the general population as variants at a very low frequency and have not been previously associated with a clinical phenotype. PLEKHG5 p.Gly1017Arg was reported only in dbSNP. We identified five patients harboring three different variants in the BSCL2 gene. Among these variants, the p.Ser230Asn variant, identified in a bulbar sALS patient, was predicted as potentially pathogenic by ACMG classification, while the p.Ser353Thr and the p.Pro428Ser were classified as VUS and were both found in patients harboring more variants of interest. The DCTN1 p.Val496Leu variant, which was located in the dynein binding domain and predicted as pathogenic, was identified in a fALS patient presenting with a classic phenotype and no cognitive impairment. Notably, autosomal dominant (AD) DCTN1 mutations have been reported in patients presenting with a lower motor neuron disease, ALS, and related to the ALS and FDT families [52,53]. While mutations in the HSPB1 gene have been previously associated with HMN, dHMN, and CMT2 [54,55], we detected the HSPB1 p.Ser135Ala in a female patient presenting with a classic ALS phenotype. This variant is located in the protein alpha-crystalline domain and is classified as likely pathogenic by ACMG. The HSPB3 p.Arg116X, predicted to create a premature stop codon, and thus classified as likely pathogenic, was identified in a patient presenting with classic ALS associated with FTD. The HSPB3 p.Gly67Ser was instead classified as VUS. Finally, the SPG11 p.Ser559Thr which was identified in a pyramidal sALS patient and the three DYNC1H1 variants, a gene previously associated with AD CMT2 and spinal muscular atrophy (SMA) phenotypes [56], were all classified as VUS. The PLEKHG5 p.Arg107Cys was identified in two unrelated sALS patients and controls, and therefore was excluded from the study.

2.1.5. Novel Candidate ALS-Associated Variants

Six variants were absent from all public genomic databases, including dbSNP, and can be considered to be novel. Of the two novel DYNC1H1 variants, the p.Lys1395Gln was predicted as likely pathogenic. Interestingly, this variant was detected in a fALS patient harboring multiple gene variants and presenting with an aggressive disease course and 11 months survival. The DYNC1H1 p.Ser1768Ile was instead predicted as VUS. The SPG11 frameshift p.Met1609Serfs*31 was the only one identified in a patient presenting with a flail arm phenotype associated with FTD. The FIG4 p.Pro344Thr variant, identified in a flail arm patient, was located in the protein phosphatase domain and was predicted as likely pathogenic by ACMG classification. Finally, the SETX p.His1951Leu variant was identified in a patient with multiple variants. Further investigations are required to determine if the novel variants have an effect at the protein level, both in the structure or in the functional activity, as well as in in affected individuals and pedigrees.

2.2. Co-Occurrence of Variants in ALS Genes Panel and Survival Analysis

In our cohort of ALS patients, 14 patients (17% overall, 24% in fALS, 15% in sALS) harbored multiple rare variants in more than one gene. Eleven of these fourteen patients presented changes in two genes and three patients carried changes in three genes (Table 2). Thirteen of these fourteen patients (93%) showed at least one variant in an ALS-associated gene; three patients harbored changes in three ALS genes, four patients in two ALS genes, while six patients harbored one gene variant in an ALS gene associated with one variant in a HMN/CMT2 gene. Finally, one patient had two variants in MND-spectrum genes. Interestingly, the two patients with the previously reported mutations in the SOD1 gene presented changes in another ALS gene, while four of the seven patients with the pathogenic C9orf72 repeat expansion were harboring a second gene variant. The C9orf72 repeat expansion was associated with ALS associated genes (DCTN1 and DYNC1H1) and MND-spectrum genes (HSPB1); of note, all these genes were previously associated with a dHMN, HMN, or CMT2 phenotype.

Table 2.

List of patients with multiple variants of interest.

| Pt ID a | Family | Variant 1 (ACMG) | Gene Category | Variant 2 (ACMG) | Gene Category | Variant 3 (ACMG) | Gene Category |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| ALS_34 | fALS | SOD1 p.Leu68Pro (5) | ALS | SQSTM1 p.Leu268Val (3) | ALS | DYNC1H1 p.Lys1395Gln (4) | ALS |

| ALS_6 | sALS | SOD1 p.Gly73Ser (5) | ALS | OPTN p.Gln314Leu (3) | ALS | SETX p.Arg1538Trp (3) | ALS |

| ALS_40 | fALS | C9orf72 expansion (5) | ALS | DYNC1H1 p.Val1250Met (3) | ALS | SETX p.His1951Leu (4) | ALS |

| ALS_52 | fALS | C9orf72 expansion (5) | ALS | DCTN1 p.Val496Leu (4) | ALS | ||

| ALS_22 | sALS | C9orf72 expansion (5) | ALS | DYNC1H1 p.Ser1768Ile (3) | ALS | ||

| ALS_27 | sALS | SPG11 p.Val922Ile (3) | ALS | FIG4 p.Pro344Thr (4) | ALS | ||

| ALS_30 | sALS | SPG11 p.Lys1013Glu (2) | ALS | SPG11 p.Cys1996Leufs*4 (5) | ALS | ||

| ALS_33 | sALS | C9orf72 expansion (5) | ALS | HSPB1 p.Ser135Ala (4) | Other/HMN/CMT2 | ||

| ALS_41 | sALS | DYNC1H1 p.Ile4071Ile (3) | ALS | HSPB3 p.Arg116Pro (4) | Other/HMN/CMT2 | ||

| ALS_4 | sALS | SPG11 p.Ile450Val (1) | ALS | HSPB3 p.Arg116X (4) | Other/HMN/CMT2 | ||

| ALS_43 | fALS | SPG11 p.Lys1013Glu (2) | ALS | BSCL2 p.Ser434Pro (3) | Other/HMN/CMT2 | ||

| ALS_67 | sALS | SPG11 p.Gly2067Gly (3) | ALS | BSCL2 p.Ala262Val (3) | Other/HMN/CMT2 | ||

| ALS_7 | sALS | SQSTM1 p.Pro118Ser (3) | ALS | BSCL2 p.Ser353Thr (3) | Other/HMN/CMT2 | ||

| ALS_53 | sALS | BSCL2 p.Arg345Trp (3) | Other/CMT2/dSMA | HSPB3 p.Gly67Ser (3) | Other/CMT2/dSMA |

a PT-ID, patient identification code. Key: American College of Medical Genetics and Genomics (ACMG) classification: 1 = benign, 2 = likely benign, 3 = uncertain significance, 4 = likely pathogenic, 5 = pathogenic. sALS, sporadic amyotrophic lateral sclerosis and fALS, familial amyotrophic lateral sclerosis.

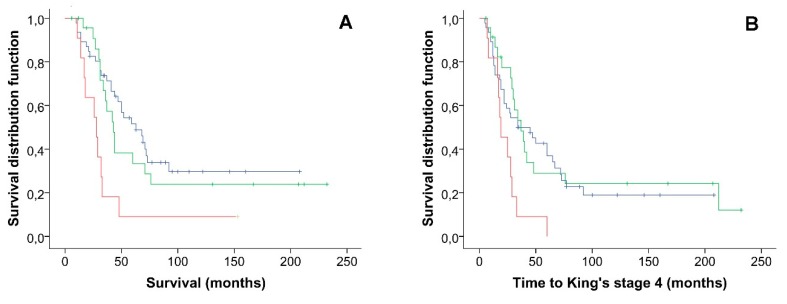

The Kaplan–Meier analysis showed that a higher variant burden is associated with reduced survival in our cohort of ALS patients, log-rank (Mantel–Cox) χ2 = 10.52, p = 0.005 (Figure 2A). The ALS patients harboring two or more rare variants had a significantly shorter median survival (28.00 months, 95% CI 16.1–39.9 months) as compared with the ALS patients carrying one rare variant (43.00 months, 95% CI 35.1–50.8) and with the ALS patients harboring no rare variants (63.00 months, 95% CI 41.8–84.1 months). Additionally, we showed that a higher rare variant burden is associated with reduced time to reach King stage 4, log-rank (Mantel–Cox) χ2 = 8.61, p = 0.01 (Figure 2B) as compared with the ALS patients harboring one or no rare variants. The ALS patients harboring two or more rare variants have a significantly shorter median time to reach King stage 4 (19.00 months, 95% CI 10.4–27.6 months) as compared with the ALS patients carrying one rare variant (37.00 months, 95% CI 25.2–48.8) and with the ALS patients harboring no rare variants (34.00 months, 95% CI 10.1–57.9 months). These results were confirmed at MAF < 0.001 in the European population of the ExAC database (Figure S1). The Kaplan–Meier analysis did not show an association between rare variant burden and age at onset.

Figure 2.

Kaplan–Meier univariate analysis for Survival (A) and time to reach King stage 4 (B). Black line, patients harboring no variants; green line, one rare variant; red line, two or more rare variants.

The Cox multivariate analysis confirmed that the burden of rare variants is independently associated with reduced survival in MND with an increased proportional hazard ratio (HR) for patients harboring more than two rare variants of 5.61 (95% CI 2.38 to 13.22, p ≤ 0.001) (Table 3). Similarly, the Cox regression model confirmed that the burden of rare variants is an independent prognostic factor for the time to reach Kings stage 4, with an increased HR for patients harboring more than two rare variants of 3.09 (95% CI 1.37 to 6.97, p = 0.007). Both results were confirmed at MAF < 0.001. (Table S6).

Table 3.

Cox proportional hazards regression multivariate analysis on survival and time to reach King stage 4 (MAF < 0.01).

| Survival | Time to King Stage 4 | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Factor | HR (95% CI) | p Value | HR (95% CI) | p Value |

| Rare variants (n) | <0.001 | 0.023 | ||

| 0 | 1 | 1 | ||

| 1 | 1.97 (0.98–3.97) | 0.220 | 1.10 (0.56–2.19) | 0.777 |

| ≥2 | 5.61 (2.38–13.22) | <0.001 | 3.09 (1.37–6.97) | 0.007 |

| Site of symptoms onset | ||||

| Spinal | 1 | 0.013 | 1 | 0.042 |

| Bulbar | 2.64 (1.23–5.70) | 2.32 (1.03–5.19) | ||

| ALSFRS-R decline (points/month) | ||||

| ≤0.60 | 1 | 0.003 | 1 | 0.036 |

| >0.60 | 4.38 (1.64–11.69) | 2.83 (1.07–7.49) | ||

| Diagnostic delay (months) | ||||

| ≤10 | ns | ns | ns | Ns |

| >10 | ||||

| Dementia | ||||

| No | ns | ns | ns | Ns |

| Yes | ||||

| Age at the onset (years) | ||||

| <60 | ns | ns | 1 | 0.016 |

| >60 | 2.17 (1.15–4.08) | |||

Variables included in the model: age at onset (<60 and >60); presence of dementia (yes or no); site of symptoms onset (bulbar and spinal); ALSFRS-R decline (≤0.60 and >0.60 points/months); diagnostic delay (≤10 months and >10 months); MAF (0, 1, and ≥2 variants). ALSFRS-R, ALS functional rating scale revised; MAF, minor allele frequency; HR, hazard ratio; CI, confidence interval; ns, not significant.

3. Discussion

In this study, by using next generation sequencing and C9orf72 repeat expansion analysis, we analyzed 29 genes in an Italian cohort of 83 patients with both familial and sporadic ALS. Overall, we detected 43 rare variants in 17 different genes and found that 43.4% of ALS patients harbored a variant in at least one of the investigated genes, with 17% of the patients showing co-occurrence of more than one gene variant. Moreover, our results show that rare variant burden is associated with reduced survival and the time to reach King stage 4, independently of known negative prognostic factors.

Overall, our findings confirm and highlight the importance of genetic susceptibility in both familial ALS, as well as in a major proportion of apparently sporadic ALS cases [15,17,57]. A direct comparison with previous studies is methodologically difficult, since our cohort was clinic-based with no strict inclusion criteria and we could not address whether differences in populations could be involved. However, the high frequency of variants detected in our cohort could probably, in part, be due to the large number of genes we examined and, in part, because some variants were observed only in a heterozygous form but could be associated with ALS as recessive or within the context of a multistep disease model [6]. Moreover, apparently, sALS patients can carry pathogenic variants with low penetrance influencing their classification as fALS versus sALS [8,17].

An interesting finding is that 28% of the variants were identified in CMT2/dSMA genes. These data confirm the emerging genetic pleiotropy of ALS [1,2,9,58]. More specifically, in relation to the specific design of our panel, our data suggest an overlap with other diseases sharing degeneration of motor axons and neurons as a common feature, such as the axonal hereditary neuropathies [9].

Mutations in the MFN2 gene are largely considered to be the primary cause underlying CMT2 [59]. Pes cavus, which is traditionally considered a distinguishing CMT clinical sign, has also been anecdotally reported in ALS patients [60], and is estimated to be as high as 2% of our case series [8]. We identified two MFN2 variants in our cohort. The p.Arg468His variant has been previously reported in CMT2 patients and its pathogenicity has also been supported by functional in vitro studies [33]. However, we excluded this variant since it was identified in our non-neurological control group.

Mutation in DYNC1H1, classified by the ALSoD database as an ALS gene, have been previously associated with autosomal dominant CMT type 2O but also with spinal muscular atrophy with a predominance of lower extremity involvement (SMA-LED), HSP, and hereditary mental retardation with cortical neuronal migration defects [59,60,61]. Among the five variants identified by our screening in DYNC1H1, the p.Lys1395Gln, which was predicted as pathogenic by in silico tools, was interestingly detected in a fALS patient with multiple gene variants and presenting with a classic ALS and aggressive disease.

Mutations in BSCL2, encoding Seipin, are responsible for pleiotropic clinical manifestations ranging from autosomal-recessive congenital generalized lipodystrophy to autosomal-dominant seipin-related motor neuron diseases, such as distal hereditary motor neuropathy type V (dHMN-V), Silver syndrome/SPG17, and CMT2 [62]. Among the variants we found in this gene, three were already reported as VUS, while the other two variants, p.Ser230Asn and p.Ser353Thr, were present in ExAC database at a very low frequency (MAF < 0.00001). Among them, the former was located in the highly conserved functional domain, analogously to the p.Ala282Thr identified by us, while the Ser353 was a cAMP and cGMP-dependent protein kinase phosphorylation site, which allowed us to speculate about the potential pathogenicity of the latter variant [63].

Structurally, small heat shock proteins B (HSPBs) are characterized by a C-terminal α-crystallin domain, which is highly conserved and important for the formation of stable dimers; therefore, mutations involving this sequence are regarded as disease causing [64]. To date, about twenty different mutations have been reported in the HSPB1 gene, associated with HMN, dHMN, dSMA, and CMT2, with both dominant and recessive inheritance [54,55]. We found the novel p.Ser135Ala variant, located in the α-crystalline domain and predicted as damaging by in silico tools. HSPB1 p.Ser135Phe/Cys/Tyr mutations have already been reported in dHMN and CMT2, [54,55] supporting the pathogenicity of this new variant. Intriguingly, our patient presented with flail leg syndrome, a restricted ALS phenotype characterized by predominant LMN involvement in the lower limbs and was also harboring the pathogenic C9orf72 repeat expansion. HSPB3, a paralogue of HSPB1, is expressed in several tissues including adult smooth muscle and brain [65]. Several mutations in this one-exon gene have been previously associated with distal hereditary motor neuropathy 2C (dHMN2C), myopathy, and CMT2 [64]. The p.Arg116Pro mutation which we found in this gene has recently been described in a patient with myopathy and functional studies have provided evidence that HSPB3 mutants could be associated with a gain of toxic function by inhibiting the formation of the HSPB2-HSPB3 complex and increasing the propensity to form nuclear aggregates [38]. Notably, in the same position, we identified the p.Arg116X nonsense variant, never reported before in the literature, in a patient with a classic phenotype. Therefore, this variant could be considered to be likely pathogenic.

Although FIG4 is classified as a major ALS gene, it was originally reported as a causative gene for CMT4J, an AR motor and sensory neuropathy [23,27]. The FIG4 p.Pro344Thr variant, identified in a flail arm patient, is located in the protein phosphatase functional domain and is predicted as deleterious by in silico tools; hence, further studies are needed to understand if this alteration can influence the protein activity. Although the same p.Ile41Thr mutation described first in CMT4J was also subsequently identified in AD fALS and sALS [28], we also found it in two controls, not supporting its pathogenicity.

In the SETX gene, we found nine unrelated patients who were carrying three variants classified as VUS, which have been reported in the ALS and non-ALS literature, including CMT2 and AOA2 [19,20], as well as the novel p.His1951Leu variant which was identified in a patient with multiple gene variants. Interestingly, as already noticed in prior NGS studies, we found an abundance of variants in this gene, which are generally described as rare [8,15].

Among the variants identified in ALS genes, we found an in-frame deletion in the protein glycin-rich domain of the FUS gene, which is absent from all public genomic databases or dbSNP. Similar insertions and deletions of G-residues in this G10-stretch region have already been reported in ALS patients [66], but also in control individuals, as confirmed by the analysis of our control group, suggesting that small G-deletions in this region could be tolerated [67,68].

In spite of the relative abundance of SPG11 variants, this gene is associated with AR HSP with thin corpus callosum and juvenile ALS under recessive disease models [69,70]. We identified the p.Cys1996Leufs*4 frameshift in a classic sALS patient with SPG11 compound heterozygosity; intriguingly, this variant has been previously reported as pathogenic in compound heterozygosity in two different unrelated patients, however, presentin with an HSP phenotype [31,32].

Recent findings have suggested a complex model of inheritance in ALS, which is consistent with a multistep pathogenetic process and could explain phenomena such as reduced penetrance or phenotypic heterogeneity, and clinical presentation and progression, which can be observed even in familial cases and between patients harboring the same gene mutation [6,8]. In our cohort, about 15% of patients were harboring variants in at least two of the investigated genes, confirming the findings of previous studies and supporting the hypothesis that rare variant burden can play a role in the multistep model of disease. Such a model would be inclusive of patients with mutations in major ALS genes [8,15,17,57,71,72,73], even if for such genes as C9orf72, SOD1, TARDBP and FUS a reduced number of pathogenetic steps has been recently suggested [74]. It is important to note that the percentage of co-occurrence of gene variants estimated by our study is higher as compared with most of the previous studies, including a recent large-scale study, identifying oligogenity in 1% of ALS patients [75]. The reported frequencies of patients with multiple variants in ALS are indeed varied, having been estimated in previous studies as 1.6% [15], 1.3% [76], 1.4% [72], 3.8% [8], 7.9% [73], 18.8% [17], and 19.5% [71]. These differences reflect a number of methodological issues such as the number and selection of sequenced genes (i.e., gene size effect or genetic variability of studied genes), presence of controls, and criteria adopted for filtering and, most importantly, for predicting the pathogenicity of identified variants. Indeed, there is no consensus on the criteria for defining a pathogenic combination of mutations, and hence the appropriate use of the “oligogenic inheritance” term itself is debatable since some variants can be classified as VUS [77] and the co-occurrence of a pathogenic variant with a VUS has been considered to be oligogenic inheritance by some studies [17,71,72], whereas in other studies the term was rigorously restricted to previously reported or potentially pathogenic variants [75]. Therefore, we acknowledge that further mechanistic functional analyses or segregation studies are needed in order to scrutinize the pathogenicity of each of the variants we identified. Indeed, the various in silico models for prediction of pathogenicity are not always consistent (Table 1) [77]; for this reason, we treated all rare variants equally in the survival analysis and did not take into account whether some variants could be more deleterious than others, in line with previous reports [17,71,72]. Notably, we showed that a higher variant burden is associated with reduced survival and time to reach King stage 4, i.e., the time to reach such important disease milestones as the need for percutaneous endoscopic gastrostomy (PEG) positioning or non-invasive mechanical ventilation (NIMV) initiation, independently from known negative prognostic factors [78,79]. This finding supports a model of ALS where the additive or synergistic effects of multiple defective genes influence disease phenotype and, in particular, affects the progression of ALS. Therefore, these data could potentially have important implications not only in clinical practice, but also for patient stratification in clinical trials, using their genetic profile.

Although an association between rare variant burden and the time to reach King stage 4 has never been explored before, our data are in accordance with previous studies, similarly showing a reduced survival in patients with variants in more than one gene [71] and a correlation with the rate of disease progression [80]. Our results did not show a relation between rare variant burden and age of onset, in line with previous reports [68]. However, other papers reported conflicting results, suggesting either earlier [8,73] or later [17] age of onset in patients carrying variants in more than one ALS gene.

Taken together, these data point to an emerging relevance of oligogenic models in ALS with growing implications in ALS molecular diagnosis and counseling, genotype–phenotype correlation studies, as well as the development of novel therapeutic strategies.

Our study has several limitations. First, our sample size is relatively small, and this is not a population-based study and as such it is potentially affected by referral bias. However, we were able to provide detailed phenotyping in order to test potential genotype–phenotype correlations. Secondly, unlike most of previous studies, although we included in our analysis some genes associated with HMN/dSMA/CMT2, based on their association with other hereditary motor syndromes [9], we acknowledge that the gene list is far from being exhaustive, and therefore this is not a truly unbiased survey of the exome or genome. However, our study design allowed us to explore specific hypotheses. We also acknowledge that the panel was designed before the discovery of some more recent ALS genes. The development of NGS technologies has certainly given us the advantage of accelerating the generation of a large amount of sequencing data; however, it has also emphasized the complexity of determining the pathogenicity of variants. This can be even more difficult in complex diseases such as ALS, for which a multistep pathogenetic process has been proposed [6]. Indeed, individual variants alone could be tolerated but when combined with a second variant would exceed the threshold required for neurodegeneration [8], a consideration that led us to not restrict our analysis to previously reported or pathogenic ALS variants, in line with previous studies [17,71,72], even if other studies adopted more stringent criteria [75]. Nonetheless, it could also be anticipated that many of the possible disease variants identified by NGS studies are not associated with ALS [15]. Indeed, it has been shown that individuals from different populations carry different profiles of rare and common variants, and that low-frequency variants show substantial geographic differentiation [81]. Given that variants in a certain region or domain of a gene are associated with ALS as disease causing variants are rare, it could be possible that the lack of study of specific populations could explain the number of variants that have not been previously reported. Moreover, the results obtained could be linked to the size of the gene or the intrinsic variability of the genes tested. In order to control for these biases, we analyzed a large cohort of in-house non-neurological controls, and excluded the variants found in the two groups. However, our analysis of non-neurological controls showed that the gene variability was comparable to that observed in the ALS group and some variants that were associated with ALS by previous studies could also be detected in the controls (Table S5), which is an observation in line with previous reports [75]. In support of our results, however, our survival analysis showed an independent negative effect for patients harboring more than one variant, indirectly corroborating the hypothesis of a potential detrimental effect of the burden of the rare variants that we identified. However, as stated above, we acknowledge that many of the novel and rare variants identified require further studies in larger cohorts of patients to validate a possible contribution to ALS.

In summary, our data contribute to a better understanding of the molecular basis of ALS supporting an oligogenic model of disease and a negative prognostic effect of rare variant burden. Moreover, our results suggest a further extension of the genetic landscape of ALS to other genes traditionally implicated in degenerative diseases of peripheral axons, such as HMN, dSMA, and CMT2. However, our results should be replicated in other independent and larger cohorts of ALS patients.

4. Materials and Methods

4.1. Subjects

We sequenced a cohort of 83 unrelated Italian ALS patients. The local ethics committee approved the study protocol. No strict inclusion or exclusion criteria were adopted; patients were included upon clinical judgment; individuals with earlier disease onset, fALS, or with no molecular diagnosis at the time of inclusion were prioritized for NGS sequencing by referring clinicians. Most of the included patients had previously been analyzed with Sanger sequencing for SOD1, C9orf72, TARDBP, and FUS variants. Patients with definite, probable, laboratory supported, or possible ALS were included in the study, according to El Escorial revised criteria [82]. Blood samples were obtained for diagnostic purposes and stored in our tissue bank, after informed consent. Progression rate was defined by the slope on the revised ALS functional rating scale (ALSFRS-R). Seventeen patients (20.5%) had fALS. The mean age of onset of our cohort was 56.02 ± 13.9 years (range 19–81 years), which is slightly lower as compared with previous population-based studies [83]. Fifty-six patients (67.5%) were males and 27 (32.5%) were females. Sixty-eight patients (81.9%) had spinal onset ALS and 15 patients (18.1%) had bulbar-onset ALS. All patients were of Caucasian ethnicity (Table S1).

4.2. DNA Preparation

Genomic DNA was extracted from peripheral EDTA-treated blood samples using the NucleoSpin® Blood L kit (Macherey-Nagel, Düren, Germany). The quality of genomic DNA was carefully evaluated and quantified by agarose gel electrophoresis, NanoDrop ND-1000 spectrophotometer (Thermo Fisher Scientific, Wilmington, DE) and Qubit 2.0 fluorometer using the Qubit dsDNA BR assay (Invitrogen, Merelbeke, Belgium). Only high-quality DNA samples (1.8–2.0 260/280 ratio and 2.0–2.2 260/230 ratio) were used for NGS analysis.

4.3. Targeted Next Generation Sequencing (NGS)

Genes for the ALS panel were selected from ALSoD (http://alsod.iop.kcl.ac.uk/) and from the Neuromuscular Disease Center (http://neuromuscular.wustl.edu/time/hmsn.html) databases. We selected major ALS genes previously associated with disease-causing mutations in patients with ALS. Moreover, we added to the panel a few non-ALS genes that we selected based on their association with hereditary motor syndromes, such as hereditary motor neuropathy (HMN), distal HMN or distal SMA (dHMN/dSMA), or axonal hereditary Charcot-Marie-Tooth neuropathy with predominant motor involvement (CMT2) (http://neuromuscular.wustl.edu/time/hmsn.html) [9]. In total, the following 28 genes divided in 2 categories were selected for the NGS targeted panel: ALS genes (ALS2, ANG, DCTN1, DYNC1H1, ERBB4, FIG4, FUS, GARS, OPTN, PFN1, PLEKHG5, SETX, SOD1, SPAST, SPG7, SPG11, SQSTM1, TARDBP, TBK1, UBQLN2, VAPB, and VCP) and other MND, HMN, and CMT2 genes (reported dSMA/hereditary motor (sensory) neuropathies (http://neuromuscular.wustl.edu/time/hmsn.html) (BSCL2, HSPB1, HSPB3, HSPB8, MFN2, and TRPV4) (Table S7).

The NGS targeted regions encompass 455 coding exons each including 20 intronic flanking bases and the 5′ and 3′ untranslated regions (UTRs). A customized design (TruSeq® Custom Amplicon, TSCA; Illumina, San Diego, CA, USA) was employed with online probe design performed by the Design Studio (DS) software (https://designstudio.illumina.com/). The regional source of coding exons was extracted from the UCSC database (Genome Browser human GRCh37/hg19). A 98% coverage was predicted for the targeted region, 127,008 bp long, with a total of 968 amplicons. Targeted resequencing was performed using the MiSeq® sequencing platform according to the manufacturer’s procedure (Illumina, San Diego, CA, USA). We analyzed single variants reported in the FASTQ and VCF output file with a commercially available NextGENe® software (version V4.0.1 SoftGenetics®, State College, PA, USA) and visualized via Integrative Genome Viewer (IGV) software (http://www.broadinstitute.org/software/igv/) [84,85]. The C9orf72 repeat expansion was analyzed in all the patients, using both amplicon-length and repeat-primed polymerase chain reactions, as described before [86].

4.4. Filters

All the regions with a sequencing depth <30 were considered to be not suitable for analysis, according to the guidelines of the American College of Medical Genetics and Genomics [77]. All variants with coverage depth >30 were filtered based on the following criteria [87]: (i) Qscore > 30; (ii) variants with minor allele frequencies (MAF) > 0.01 identified in the dbSNP150 database (www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/projects/SNP/) or Exome Aggregation Consortium Sequencing Project (ExAC; exac.broadinstitute.org) were filter out, in agreement with the ACMG classification criteria [77], with the exception of variants reported as pathogenic or of uncertain significance [8,18,73,87]; (iii) synonymous changes were excluded except for those located within or near splice sites. The impact of candidate variants was evaluated using prediction tools: Sorting Intolerant from Tolerant software (SIFT; sift.jcvi.org) [88], Polymorphism Phenotyping (PolyPhen-2; genetics.bwh.harvard.edu/pph2/) [89], and Mutation Taster (www.mutationtaster.org/) (Table S8). Clinical significance of reported variants was assessed on the basis of the ACMG guidelines [77]. A cohort of 332 non-neurological unrelated Italian patients, for whom NGS exome sequencing data were available from our in-house database, was selected as the control group. Variants in common between ALS patients and controls were excluded.

4.5. Sanger Sequencing Validation

All the identified variants were confirmed by Sanger sequencing. We designed primers using Primer3 (http://biotools.umassmed.edu/bioapps/primer3_www.cgi) to perform a direct sequencing. The PCR products were purified using AMPure (Agencourt-Beckmann Coulter, Inc., Brea, CA, USA), then, sequenced in both directions using a Big Dye Terminator v1.1 Cycle Sequencing Kit (Applied Biosystems Foster City, CA, USA). Sequencing products were purified using a Big Dye X-Terminator Kit (Applied Biosystems Foster City, CA, USA) and run on an ABI 3730 Genetic Analyzer (Applied Biosystems Foster City, CA, USA). Amplicon Sequences were compared with the reference sequence (hg19) using Sequencer 5.0 Software (Gene Codes). Primers are available on request. The validated variants were reported in the results depending on whether they were previously reported in the ALS literature, in the non-ALS literature, in population databases (including those reported only in dbSNP), or never reported (novel variants).

4.6. Statistical Analysis

Descriptive statistics are reported as count and percentage, for categorical variables, or mean and standard deviation, for continuous variables. The Chi-squared test, with Bonferroni correction for multiple comparisons, was used to explore differences in gene variant frequencies between ALS patients and non-neurological controls (Table S5). Kaplan–Meier univariate analyses were carried out to determine the effect of the burden of rare variants at MAF < 0.01 [8,18,73,87] on survival (defined as time from symptoms onset to death or tracheostomy), time needed to reach KING stage 4 (defined as the time from symptom onset to PEG or NIMV positioning), and age of onset. Moreover, we confirmed the results of survival analysis at the more stringent cut off of MAF < 0.001 [70]. Log-rank tests were used to test for differences between groups. Subsequently, multivariable analysis with Cox proportional hazards model (stepwise backward) was performed to estimate the proportional hazard ratio (HR) of rare variant burden on survival and on time needed to reach KING stage 4. Cox regressions were adjusted for the following factors known to influence survival in ALS patients: site of symptoms onset, diagnostic delay, presence of dementia, age at the onset, and progression rate, defined by the slope on the revised ALS functional rating scale (ALSFRS-R), i.e., ΔALSFRS-R = (48 minus ALSFRS-R score )/(date of the ALSFRS-R score minus date of onset) [77,89]. In the survival analysis, we treated all rare variants equally, and did not take into account whether some variants could be predicted to be more deleterious than others, according to previous ALS studies and since reliable models for rare variants interactions are still lacking [17,70,71]. Statistical analyses were performed using IBM Statistical Package for Social Science (SPSS) version 20, with p-value < 0.05.

Abbreviations

| ALS | Amyotrophic lateral sclerosis |

| MND | Motor neuron diseases |

| UMN | Upper motor neurons |

| LMN | Lower motor neurons |

| fALS | Familial amyotrophic lateral sclerosis |

| sALS | Sporadic smyotrophic lateral sclerosis |

| SOD1 | Superoxide Dismutase 1 |

| C9orf72 | Chromosome 9 open reading frame 72 |

| TARDBP | TAR DNA binding protein |

| FUS | FUS RNA binding protein |

| CMT | Charcot-Marie-Tooth neuropathy |

| dHMN | Distal hereditary motor neuropathy |

| NGS | Next generation sequencing |

| ALS2 | Alsin Rho guanine nucleotide exchange factor |

| ANG | Angiogenin |

| DCTN1 | Dynactin subunit 1 |

| ERBB4 | Erb-B2 receptor tyrosine kinase 4 |

| FIG4 | FIG4 phosphoinositide 5-phosphatase |

| OPTN | Optineurin |

| PFN1 | Profilin 1 |

| SETX | Senataxin |

| SPAST | Spastin |

| SPG11 | Spatacsin vesicle trafficking associated |

| SQSTM1 | Sequestosome 1 |

| UBQLN2 | Ubiquilin 2 |

| VAPB | VAMP associated protein B and C |

| VCP | Valosin containing protein |

| DYNC1H1 | Dynein cytoplasmic 1 heavy chain 1 |

| GARS | Glycyl-tRNA synthetase |

| PLEKHG5 | Pleckstrin homology and RhoGEF domain containing G5 |

| SPG7 | Paraplegin matrix AAA peptidase subunit |

| BSCL2 | Seipin lipid droplet biogenesis associated |

| HSPB1 | Heat shock protein family B (Small) member 1 |

| HSPB3 | Heat shock protein family B (Small) member 3 |

| HSPB8 | Heat shock protein family B (Small) member 8 |

| MFN2 | Mitofusin 2 |

| TRPV4 | Transient receptor potential cation channel subfamily V member 4 |

| TBK1 | TANK-binding kinase 1 |

| HSP | Hereditary spastic paraplegia |

| dSMA | Distal spinal muscular atrophy |

| POAG | Primary open angle glaucoma |

| AOA2 | Ataxia with oculomotor apraxia type 2 |

| PEO | Progressive external ophthalmoplegia |

| AD | Alzheimer disease |

| FTD | Frontotemporal dementia |

| SMA-LED | Spinal muscular atrophy with predominance of lower extremity involvement |

| PEG | Percutaneous endoscopic gastrostomy |

| NIMV | Non-invasive mechanical ventilation |

Supplementary Materials

Supplementary materials can be found at https://www.mdpi.com/1422-0067/21/9/3346/s1. Table S1. Clinical and demographic characteristics of ALS patients. Table S2. Rare variants identified in this study and clinical features of the index patients. Table S3. Rare variants identified in non-neurological controls (664 Chromosomes). Table S4. Variants identified in this study and presence in controls. Table S5. Overview of variants identified in ALS patients and controls. Table S6. Cox proportional hazards regression multivariate analysis on survival and time to King stage 4 (MAF < 0.001). Table S7. Genes present in the panel. Table S8. Criteria for evaluation and filtering of the identified variants in this study. Figure S1. Kaplan-Meier univariate analysis for Survival (A) and time to King’s stage 4 (B) (MAF < 0.001). Black line: patients harboring no variants; green line: one rare variant; red line: two or more rare variants.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, N.R. and A.Q.; methodology, S.S., T.D., L.P., A.R., L.M., G.B.P., P.P., and A.Q.; software, S.S., A.R., and P.C.; validation, T.D., L.P., L.C., and N.R.; formal analysis, S.S., T.D., L.P., G.B.P., Y.M.F., A.R., L.M., S.P. and N.R.; investigation, S.S., T.D., L.P., Y.M.F., S.P. R.F., and A.R., resources, F.A., M.F., N.R., and A.Q.; data curation, S.S., T.D., L.P., Y.M.F., A.R., L.M., C.L., L.T., R.F., and N.R.; writing—original draft preparation, S.S., T.D., L.P., Y.M.F., and N.R.; writing—review and editing, V.S. C.L., L.T., R.F., F.A., M.F., P.C., N.R., and A.Q.; visualization, S.S., T.D., L.P., Y.M.F., and N.R.; supervision, V.S., C.L., L.T., F.A., M.F., P.C., N.R., and A.Q.; project administration, F.A., M.F., N.R., and A.Q.; funding acquisition, F.A., M.F., N.R., and A.Q. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This study was partially supported by a grant from the Italian Ministry of Health (#RF-2011-02351193).

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest. The funders had no role in the design of the study; in the collection, analyses, or interpretation of data; in the writing of the manuscript, or in the decision to publish the results.

References

- 1.Riva N., Agosta F., Lunetta C., Filippi M., Quattrini A. Recent advances in amyotrophic lateral sclerosis. J. Neurol. 2016;263:1241–1254. doi: 10.1007/s00415-016-8091-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Van Es M.A., Hardiman O., Chio A., Al-Chalabi A., Pasterkamp R.J., Veldink J.H., van den Berg L.H. Amyotrophic lateral sclerosis. Lancet. 2017;390:2084–2098. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(17)31287-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Logroscino G., Traynor B.J., Hardiman O., Chio A., Mitchell D., Swingler R.J., Millul A., Benn E., Beghi E. Incidence of amyotrophic lateral sclerosis in europe. J. Neurol. Neurosurg. Psychiatry. 2010;81:385–390. doi: 10.1136/jnnp.2009.183525. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Renton A.E., Chio A., Traynor B.J. State of play in amyotrophic lateral sclerosis genetics. Nat. Neurosci. 2014;17:17–23. doi: 10.1038/nn.3584. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Al-Chalabi A., Fang F., Hanby M.F., Leigh P.N., Shaw C.E., Ye W., Rijsdijk F. An estimate of amyotrophic lateral sclerosis heritability using twin data. J. Neurol. Neurosurg. Psychiatry. 2010;81:1324–1326. doi: 10.1136/jnnp.2010.207464. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Al-Chalabi A., Calvo A., Chio A., Colville S., Ellis C.M., Hardiman O., Heverin M., Howard R.S., Huisman M.H.B., Keren N., et al. Analysis of amyotrophic lateral sclerosis as a multistep process: A population-based modelling study. Lancet Neurol. 2014;13:1108–1113. doi: 10.1016/S1474-4422(14)70219-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.The scottish motor neuron disease register: A prospective study of adult onset motor neuron disease in scotland. Methodology, demography and clinical features of incident cases in 1989. J. Neurol. Neurosurg. Psychiatry. 1992;55:536–541. doi: 10.1136/jnnp.55.7.536. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Cady J., Allred P., Bali T., Pestronk A., Goate A., Miller T.M., Mitra R.D., Ravits J., Harms M.B., Baloh R.H. Amyotrophic lateral sclerosis onset is influenced by the burden of rare variants in known amyotrophic lateral sclerosis genes. Ann. Neurol. 2015;77:100–113. doi: 10.1002/ana.24306. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Gentile F., Scarlino S., Falzone Y.M., Lunetta C., Tremolizzo L., Quattrini A., Riva N. The peripheral nervous system in amyotrophic lateral sclerosis: Opportunities for translational research. Front. Neurosci. 2019;13:601. doi: 10.3389/fnins.2019.00601. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Riva N., Iannaccone S., Corbo M., Casellato C., Sferrazza B., Lazzerini A., Scarlato M., Cerri F., Previtali S.C., Nobile-Orazio E., et al. Motor nerve biopsy: Clinical usefulness and histopathological criteria. Ann. Neurol. 2011;69:197–201. doi: 10.1002/ana.22110. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Agosta F., Galantucci S., Magnani G., Marcone A., Martinelli D., Antonietta Volonte M., Riva N., Iannaccone S., Ferraro P.M., Caso F., et al. Mri signatures of the frontotemporal lobar degeneration continuum. Hum. Brain Mapp. 2015;36:2602–2614. doi: 10.1002/hbm.22794. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Orrell R.W., Marklund S.L., deBelleroche J.S. Familial als is associated with mutations in all exons of sod1: A novel mutation in exon 3 (gly72ser) J. Neurol. Sci. 1997;153:46–49. doi: 10.1016/S0022-510X(97)00181-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Kobayashi Z., Tsuchiya K., Kubodera T., Shibata N., Arai T., Miura H., Ishikawa C., Kondo H., Ishizu H., Akiyama H., et al. Fals with gly72ser mutation in sod1 gene: Report of a family including the first autopsy case. J. Neurol. Sci. 2011;300:9–13. doi: 10.1016/j.jns.2010.10.030. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Del Grande A., Luigetti M., Conte A., Mancuso I., Lattante S., Marangi G., Stipa G., Zollino M., Sabatelli M. A novel l67p sod1 mutation in an italian als patient. Amyotroph. Lateral Scler. 2011;12:150–152. doi: 10.3109/17482968.2011.551939. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Kenna K.P., McLaughlin R.L., Byrne S., Elamin M., Heverin M., Kenny E.M., Cormican P., Morris D.W., Donaghy C.G., Bradley D.G., et al. Delineating the genetic heterogeneity of als using targeted high-throughput sequencing. J. Med. Genet. 2013;50:776–783. doi: 10.1136/jmedgenet-2013-101795. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Pozzi L., Valenza F., Mosca L., Dal Mas A., Domi T., Romano A., Tarlarini C., Falzone Y.M., Tremolizzo L., Soraru G., et al. Tbk1 mutations in italian patients with amyotrophic lateral sclerosis: Genetic and functional characterisation. J. Neurol. Neurosurg. Psychiatry. 2017;88:869–875. doi: 10.1136/jnnp-2017-316174. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Kruger S., Battke F., Sprecher A., Munz M., Synofzik M., Schols L., Gasser T., Grehl T., Prudlo J., Biskup S. Rare variants in neurodegeneration associated genes revealed by targeted panel sequencing in a german als cohort. Front. Mol. Neurosci. 2016;9:92. doi: 10.3389/fnmol.2016.00092. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Morgan S., Shoai M., Fratta P., Sidle K., Orrell R., Sweeney M.G., Shatunov A., Sproviero W., Jones A., Al-Chalabi A., et al. Investigation of next-generation sequencing technologies as a diagnostic tool for amyotrophic lateral sclerosis. Neurobiol. Aging. 2015;36:1600.e5–1600.e8. doi: 10.1016/j.neurobiolaging.2014.12.017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Bernard V., Stricker S., Kreuz F., Minnerop M., Gillessen-Kaesbach G., Zuhlke C. Ataxia with oculomotor apraxia type 2: Novel mutations in six patients with juvenile age of onset and elevated serum alpha-fetoprotein. Neuropediatrics. 2008;39:347–350. doi: 10.1055/s-0029-1214424. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Hoyer H., Braathen G.J., Busk O.L., Holla O.L., Svendsen M., Hilmarsen H.T., Strand L., Skjelbred C.F., Russell M.B. Genetic diagnosis of charcot-marie-tooth disease in a population by next-generation sequencing. Biomed. Res. Int. 2014;2014:210401. doi: 10.1155/2014/210401. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Arning L., Epplen J.T., Rahikkala E., Hendrich C., Ludolph A.C., Sperfeld A.D. The setx missense variation spectrum as evaluated in patients with als4-like motor neuron diseases. Neurogenetics. 2013;14:53–61. doi: 10.1007/s10048-012-0347-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Pensato V., Castellotti B., Gellera C., Pareyson D., Ciano C., Nanetti L., Salsano E., Piscosquito G., Sarto E., Eoli M., et al. Overlapping phenotypes in complex spastic paraplegias spg11, spg15, spg35 and spg48. Brain. 2014;137:1907–1920. doi: 10.1093/brain/awu121. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Chow C.Y., Zhang Y., Dowling J.J., Jin N., Adamska M., Shiga K., Szigeti K., Shy M.E., Li J., Zhang X., et al. Mutation of fig4 causes neurodegeneration in the pale tremor mouse and patients with cmt4j. Nature. 2007;448:68–72. doi: 10.1038/nature05876. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Nicholson G., Lenk G.M., Reddel S.W., Grant A.E., Towne C.F., Ferguson C.J., Simpson E., Scheuerle A., Yasick M., Hoffman S., et al. Distinctive genetic and clinical features of cmt4j: A severe neuropathy caused by mutations in the pi(3,5)p(2) phosphatase fig4. Brain. 2011;134:1959–1971. doi: 10.1093/brain/awr148. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Menezes M.P., Waddell L., Lenk G.M., Kaur S., MacArthur D.G., Meisler M.H., Clarke N.F. Whole exome sequencing identifies three recessive fig4 mutations in an apparently dominant pedigree with charcot-marie-tooth disease. Neuromuscul. Disord. 2014;24:666–670. doi: 10.1016/j.nmd.2014.04.010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Lenk G.M., Ferguson C.J., Chow C.Y., Jin N., Jones J.M., Grant A.E., Zolov S.N., Winters J.J., Giger R.J., Dowling J.J., et al. Pathogenic mechanism of the fig4 mutation responsible for charcot-marie-tooth disease cmt4j. PLoS Genet. 2011;7:e1002104. doi: 10.1371/journal.pgen.1002104. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Chow C.Y., Landers J.E., Bergren S.K., Sapp P.C., Grant A.E., Jones J.M., Everett L., Lenk G.M., McKenna-Yasek D.M., Weisman L.S., et al. Deleterious variants of fig4, a phosphoinositide phosphatase, in patients with als. Am. J. Hum. Genet. 2009;84:85–88. doi: 10.1016/j.ajhg.2008.12.010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Osmanovic A., Rangnau I., Kosfeld A., Abdulla S., Janssen C., Auber B., Raab P., Preller M., Petri S., Weber R.G. Fig4 variants in central european patients with amyotrophic lateral sclerosis: A whole-exome and targeted sequencing study. Eur. J. Hum. Genet. 2017;25:324–331. doi: 10.1038/ejhg.2016.186. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Takahashi Y., Fukuda Y., Yoshimura J., Toyoda A., Kurppa K., Moritoyo H., Belzil V.V., Dion P.A., Higasa K., Doi K., et al. Erbb4 mutations that disrupt the neuregulin-erbb4 pathway cause amyotrophic lateral sclerosis type 19. Am. J. Hum. Genet. 2013;93:900–905. doi: 10.1016/j.ajhg.2013.09.008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Rudloff U., Samuels Y. A growing family: Adding mutated erbb4 as a novel cancer target. Cell Cycle. 2010;9:1487–1503. doi: 10.4161/cc.9.8.11239. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Stevanin G., Azzedine H., Denora P., Boukhris A., Tazir M., Lossos A., Rosa A.L., Lerer I., Hamri A., Alegria P., et al. Mutations in spg11 are frequent in autosomal recessive spastic paraplegia with thin corpus callosum, cognitive decline and lower motor neuron degeneration. Brain. 2008;131:772–784. doi: 10.1093/brain/awm293. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Denora P.S., Schlesinger D., Casali C., Kok F., Tessa A., Boukhris A., Azzedine H., Dotti M.T., Bruno C., Truchetto J., et al. Screening of arhsp-tcc patients expands the spectrum of spg11 mutations and includes a large scale gene deletion. Hum. Mutat. 2009;30:E500–E519. doi: 10.1002/humu.20945. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.DiVincenzo C., Elzinga C.D., Medeiros A.C., Karbassi I., Jones J.R., Evans M.C., Braastad C.D., Bishop C.M., Jaremko M., Wang Z., et al. The allelic spectrum of charcot-marie-tooth disease in over 17,000 individuals with neuropathy. Mol. Genet. Genom. Med. 2014;2:522–529. doi: 10.1002/mgg3.106. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Cuyvers E., van der Zee J., Bettens K., Engelborghs S., Vandenbulcke M., Robberecht C., Dillen L., Merlin C., Geerts N., Graff C., et al. Genetic variability in sqstm1 and risk of early-onset alzheimer dementia: A european early-onset dementia consortium study. Neurobiol. Aging. 2015;36:2005.e15–2005.e22. doi: 10.1016/j.neurobiolaging.2015.02.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Van der Zee J., Van Langenhove T., Kovacs G.G., Dillen L., Deschamps W., Engelborghs S., Matej R., Vandenbulcke M., Sieben A., Dermaut B., et al. Rare mutations in sqstm1 modify susceptibility to frontotemporal lobar degeneration. Acta Neuropathol. 2014;128:397–410. doi: 10.1007/s00401-014-1298-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Zhang J., Grubor V., Love C.L., Banerjee A., Richards K.L., Mieczkowski P.A., Dunphy C., Choi W., Au W.Y., Srivastava G., et al. Genetic heterogeneity of diffuse large b-cell lymphoma. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 2013;110:1398–1403. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1205299110. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Giannakis M., Hodis E., Jasmine Mu X., Yamauchi M., Rosenbluh J., Cibulskis K., Saksena G., Lawrence M.S., Qian Z.R., Nishihara R., et al. Rnf43 is frequently mutated in colorectal and endometrial cancers. Nat. Genet. 2014;46:1264–1266. doi: 10.1038/ng.3127. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Morelli F.F., Verbeek D.S., Bertacchini J., Vinet J., Mediani L., Marmiroli S., Cenacchi G., Nasi M., De Biasi S., Brunsting J.F., et al. Aberrant compartment formation by hspb2 mislocalizes lamin a and compromises nuclear integrity and function. Cell Rep. 2017;20:2100–2115. doi: 10.1016/j.celrep.2017.08.018. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Morais S., Raymond L., Mairey M., Coutinho P., Brandao E., Ribeiro P., Loureiro J.L., Sequeiros J., Brice A., Alonso I., et al. Massive sequencing of 70 genes reveals a myriad of missing genes or mechanisms to be uncovered in hereditary spastic paraplegias. Eur. J. Hum. Genet. 2017;25:1217–1228. doi: 10.1038/ejhg.2017.124. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Casasnovas C., Banchs I., Cassereau J., Gueguen N., Chevrollier A., Martinez-Matos J.A., Bonneau D., Volpini V. Phenotypic spectrum of mfn2 mutations in the spanish population. J. Med. Genet. 2010;47:249–256. doi: 10.1136/jmg.2009.072488. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Engelfried K., Vorgerd M., Hagedorn M., Haas G., Gilles J., Epplen J.T., Meins M. Charcot-marie-tooth neuropathy type 2a: Novel mutations in the mitofusin 2 gene (mfn2) BMC Med. Genet. 2006;7:53. doi: 10.1186/1471-2350-7-53. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.McCorquodale D.S., 3rd, Montenegro G., Peguero A., Carlson N., Speziani F., Price J., Taylor S.W., Melanson M., Vance J.M., Zuchner S. Mutation screening of mitofusin 2 in charcot-marie-tooth disease type 2. J. Neurol. 2011;258:1234–1239. doi: 10.1007/s00415-011-5910-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Cassereau J., Casasnovas C., Gueguen N., Malinge M.C., Guillet V., Reynier P., Bonneau D., Amati-Bonneau P., Banchs I., Volpini V., et al. Simultaneous mfn2 and gdap1 mutations cause major mitochondrial defects in a patient with cmt. Neurology. 2011;76:1524–1526. doi: 10.1212/WNL.0b013e318217e77d. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Braathen G.J., Sand J.C., Lobato A., Hoyer H., Russell M.B. Mfn2 point mutations occur in 3.4% of charcot-marie-tooth families. An investigation of 232 norwegian cmt families. BMC Med. Genet. 2010;11:48. doi: 10.1186/1471-2350-11-48. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Antoniadi T., Buxton C., Dennis G., Forrester N., Smith D., Lunt P., Burton-Jones S. Application of targeted multi-gene panel testing for the diagnosis of inherited peripheral neuropathy provides a high diagnostic yield with unexpected phenotype-genotype variability. BMC Med. Genet. 2015;16:84. doi: 10.1186/s12881-015-0224-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Sanchez-Ferrero E., Coto E., Beetz C., Gamez J., Corao A.I., Diaz M., Esteban J., del Castillo E., Moris G., Infante J., et al. Spg7 mutational screening in spastic paraplegia patients supports a dominant effect for some mutations and a pathogenic role for p.A510v. Clin. Genet. 2013;83:257–262. doi: 10.1111/j.1399-0004.2012.01896.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Roxburgh R.H., Marquis-Nicholson R., Ashton F., George A.M., Lea R.A., Eccles D., Mossman S., Bird T., van Gassen K.L., Kamsteeg E.J., et al. The p.Ala510val mutation in the spg7 (paraplegin) gene is the most common mutation causing adult onset neurogenetic disease in patients of british ancestry. J. Neurol. 2013;260:1286–1294. doi: 10.1007/s00415-012-6792-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.McDermott C.J., Dayaratne R.K., Tomkins J., Lusher M.E., Lindsey J.C., Johnson M.A., Casari G., Turnbull D.M., Bushby K., Shaw P.J. Paraplegin gene analysis in hereditary spastic paraparesis (hsp) pedigrees in northeast england. Neurology. 2001;56:467–471. doi: 10.1212/WNL.56.4.467. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Klebe S., Depienne C., Gerber S., Challe G., Anheim M., Charles P., Fedirko E., Lejeune E., Cottineau J., Brusco A., et al. Spastic paraplegia gene 7 in patients with spasticity and/or optic neuropathy. Brain. 2012;135:2980–2993. doi: 10.1093/brain/aws240. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Pfeffer G., Gorman G.S., Griffin H., Kurzawa-Akanbi M., Blakely E.L., Wilson I., Sitarz K., Moore D., Murphy J.L., Alston C.L., et al. Mutations in the spg7 gene cause chronic progressive external ophthalmoplegia through disordered mitochondrial DNA maintenance. Brain. 2014;137:1323–1336. doi: 10.1093/brain/awu060. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Bonn F., Pantakani K., Shoukier M., Langer T., Mannan A.U. Functional evaluation of paraplegin mutations by a yeast complementation assay. Hum. Mutat. 2010;31:617–621. doi: 10.1002/humu.21226. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Munch C., Sedlmeier R., Meyer T., Homberg V., Sperfeld A.D., Kurt A., Prudlo J., Peraus G., Hanemann C.O., Stumm G., et al. Point mutations of the p150 subunit of dynactin (dctn1) gene in als. Neurology. 2004;63:724–726. doi: 10.1212/01.WNL.0000134608.83927.B1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Puls I., Jonnakuty C., LaMonte B.H., Holzbaur E.L., Tokito M., Mann E., Floeter M.K., Bidus K., Drayna D., Oh S.J., et al. Mutant dynactin in motor neuron disease. Nat. Genet. 2003;33:455–456. doi: 10.1038/ng1123. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Lupo V., Aguado C., Knecht E., Espinos C. Chaperonopathies: Spotlight on hereditary motor neuropathies. Front. Mol. Biosci. 2016;3:81. doi: 10.3389/fmolb.2016.00081. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Evgrafov O.V., Mersiyanova I., Irobi J., Van Den Bosch L., Dierick I., Leung C.L., Schagina O., Verpoorten N., Van Impe K., Fedotov V., et al. Mutant small heat-shock protein 27 causes axonal charcot-marie-tooth disease and distal hereditary motor neuropathy. Nat. Genet. 2004;36:602–606. doi: 10.1038/ng1354. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Fiorillo C., Moro F., Yi J., Weil S., Brisca G., Astrea G., Severino M., Romano A., Battini R., Rossi A., et al. Novel dynein dync1h1 neck and motor domain mutations link distal spinal muscular atrophy and abnormal cortical development. Hum. Mutat. 2014;35:298–302. doi: 10.1002/humu.22491. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.van Blitterswijk M., van Es M.A., Hennekam E.A., Dooijes D., van Rheenen W., Medic J., Bourque P.R., Schelhaas H.J., van der Kooi A.J., de Visser M., et al. Evidence for an oligogenic basis of amyotrophic lateral sclerosis. Hum. Mol. Genet. 2012;21:3776–3784. doi: 10.1093/hmg/dds199. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Chornenkyy Y., Fardo D.W., Nelson P.T. Tau and tdp-43 proteinopathies: Kindred pathologic cascades and genetic pleiotropy. Lab. Investig. 2019;99:993–1007. doi: 10.1038/s41374-019-0196-y. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Weedon M.N., Hastings R., Caswell R., Xie W., Paszkiewicz K., Antoniadi T., Williams M., King C., Greenhalgh L., Newbury-Ecob R., et al. Exome sequencing identifies a dync1h1 mutation in a large pedigree with dominant axonal charcot-marie-tooth disease. Am. J. Hum. Genet. 2011;89:308–312. doi: 10.1016/j.ajhg.2011.07.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Harms M.B., Allred P., Gardner R., Jr., Fernandes Filho J.A., Florence J., Pestronk A., Al-Lozi M., Baloh R.H. Dominant spinal muscular atrophy with lower extremity predominance: Linkage to 14q32. Neurology. 2010;75:539–546. doi: 10.1212/WNL.0b013e3181ec800c. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Beecroft S.J., McLean C.A., Delatycki M.B., Koshy K., Yiu E., Haliloglu G., Orhan D., Lamont P.J., Davis M.R., Laing N.G., et al. Expanding the phenotypic spectrum associated with mutations of dync1h1. Neuromuscul. Disord. 2017;27:607–615. doi: 10.1016/j.nmd.2017.04.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Ito D., Suzuki N. Seipinopathy: A novel endoplasmic reticulum stress-associated disease. Brain. 2009;132:8–15. doi: 10.1093/brain/awn216. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Craveiro Sarmento A.S., de Azevedo Medeiros L.B., Agnez-Lima L.F., Lima J.G., de Melo Campos J.T.A. Exploring seipin: From biochemistry to bioinformatics predictions. Int. J. Cell Biol. 2018;2018:5207608. doi: 10.1155/2018/5207608. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Datskevich P.N., Nefedova V.V., Sudnitsyna M.V., Gusev N.B. Mutations of small heat shock proteins and human congenital diseases. Biochem. Biokhimiia. 2012;77:1500–1514. doi: 10.1134/S0006297912130081. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Asthana A., Raman B., Ramakrishna T., Rao Ch M. Structural aspects and chaperone activity of human hspb3: Role of the “c-terminal extension”. Cell Biochem. Biophys. 2012;64:61–72. doi: 10.1007/s12013-012-9366-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Corrado L., Del Bo R., Castellotti B., Ratti A., Cereda C., Penco S., Soraru G., Carlomagno Y., Ghezzi S., Pensato V., et al. Mutations of fus gene in sporadic amyotrophic lateral sclerosis. J. Med. Genet. 2010;47:190–194. doi: 10.1136/jmg.2009.071027. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Kwon M.J., Baek W., Ki C.S., Kim H.Y., Koh S.H., Kim J.W., Kim S.H. Screening of the sod1, fus, tardbp, ang, and optn mutations in korean patients with familial and sporadic als. Neurobiol. Aging. 2012;33:1017.e17–1017.e23. doi: 10.1016/j.neurobiolaging.2011.12.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Van Langenhove T., van der Zee J., Sleegers K., Engelborghs S., Vandenberghe R., Gijselinck I., Van den Broeck M., Mattheijssens M., Peeters K., De Deyn P.P., et al. Genetic contribution of fus to frontotemporal lobar degeneration. Neurology. 2010;74:366–371. doi: 10.1212/WNL.0b013e3181ccc732. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Paisan-Ruiz C., Dogu O., Yilmaz A., Houlden H., Singleton A. Spg11 mutations are common in familial cases of complicated hereditary spastic paraplegia. Neurology. 2008;70:1384–1389. doi: 10.1212/01.wnl.0000294327.66106.3d. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Orlacchio A., Babalini C., Borreca A., Patrono C., Massa R., Basaran S., Munhoz R.P., Rogaeva E.A., St George-Hyslop P.H., Bernardi G., et al. Spatacsin mutations cause autosomal recessive juvenile amyotrophic lateral sclerosis. Brain. 2010;133:591–598. doi: 10.1093/brain/awp325. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Pang S.Y., Hsu J.S., Teo K.C., Li Y., Kung M.H.W., Cheah K.S.E., Chan D., Cheung K.M.C., Li M., Sham P.C., et al. Burden of rare variants in als genes influences survival in familial and sporadic als. Neurobiol. Aging. 2017;58:238.e9–238.e15. doi: 10.1016/j.neurobiolaging.2017.06.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]