Abstract

The aim of this work is to evaluate the attitudes, behaviours, and knowledge of health workers employed at an Italian University Hospital on the topic of vaccinations and in regard to flu vaccination. To this end, the study provided for the articulation of a computerised questionnaire on the digital platform EUSurvey which was administered online via e-mail to a sample of 457 health workers, in the period between November 2018 and March 2019. The data were subjected to descriptive and inferential statistical analysis. In particular, a logistic regression analysis was carried out in order to evaluate the relationship between the variables collected and the dichotomous outcome (vaccinated/unvaccinated subjects in the 2018–2019 season). The results, in line with what has been reported by the literature, highlighted that vaccine hesitancy is prevalent also among health workers. Furthermore, according to our study, only 30.6% of the health care workers had the flu vaccination. The survey points out the need to plan educational and informative interventions aimed at changing the attitudes, behaviours, and knowledge of health workers in the field of flu vaccination, for the purpose of protecting the health of healthcare personnel and their patients.

Keywords: vaccination, health worker, flu vaccination, vaccine hesitancy

1. Introduction

Influenza syndrome is a significant public health problem and a major source of direct and indirect costs due to the management of cases and complications of the disease [1]. Globally, according to the World Health Organisation (WHO), the flu virus affects between 5% and 15% of the adult population every year (from 350 million to 1 billion people), with a mortality rate ranging from 250,000 to 500,000 deaths [1,2,3]. According to the European Centre for Disease Prevention and Control (ECDC), between 4 and 50 million people in Europe each year experience symptomatic flu with between 15,000 and 70,000 related deaths [4]. Ninety percent of deaths occur in subjects over the age of 65, especially among those with underlying chronic clinical conditions [5,6]. In Italy alone, 5–8 million people are affected by flu syndrome each year, the impact of which, in terms of lethality, translates to an estimated 8000 deaths per year [7,8].

In public health, the prevention of seasonal flu is of utmost importance in order to reduce its epidemiological, clinical, and economic impact [9,10]. To date, vaccination is the most effective preventive strategy available for this purpose [6,11]. However, despite this important opportunity for prevention, the percentage of vaccinated individuals is constantly decreasing [2,12].

For the 2018/2019 season, the coverage values recorded in Italy show a percentage of 15.8%, slightly higher than that of the previous season (15.3% in the two-year period 2017–2018). In Sardinia, influenza vaccination coverage per 100 inhabitants is 14.2% [8,12].

With regard to the poor compliance with flu vaccination, numerous studies in the literature show that seasonal flu in a common sense represents a health event whose clinical and social impact is largely underestimated [2,3,13,14].

The altered perception of the health risk, in this context, has a significant impact on health decisions made by the population; in fact, a discrepancy between real danger and perceived risk can lead to inappropriate behaviours that do not comply with the recommended public health measures [15]. According to the “outrage” theory coined by the American sociologist Peter Sandman [16], in the perception of risk, a key role is played by the emotional component surrounding the event.

Influenza is often perceived by the population as an exacerbated or an inapparent risk, compared to the real incidence of the disease [17,18,19,20]. What is more, several studies have shown that an inaccurate perception of the magnitude of an event is based on poor and ineffective risk communication [20,21,22,23,24].

The rampant phenomenon of vaccine hesitancy [25,26,27,28] highlights the need to focus attention on the complexity of the communication processes, which are indispensable for adequate adherence to vaccination. In fact, despite the various initiatives promoted at a national and international level, the spread of distorted information in the media and in particular on the various social networking sites has led to a decrease in vaccination coverage among healthcare workers also [28,29,30,31,32].

Healthcare workers are particularly exposed to the risk of contracting the flu (in a clinical and sub-clinical form) and also transmitting the infection to patients whose underlying conditions increase the risk of complications [2,33,34,35,36]. In the global healthcare landscape, in order to guarantee the protection of patients and the health workers themselves, the Centres of Disease Control and Prevention (CDC), the Advisory Committee on Immunization Practices (ACIP), and the Healthcare Infection Control Practices Advisory Committee (HICPAC) annually recommend anti-influenza vaccination to all healthcare professionals [35,36,37]. In the United States, to optimise the control of influenza in the healthcare environment, the “Healthy People 2020” plan was released, establishing a minimum target of 90% flu vaccination coverage among health workers by 2020 [38].

In Europe, all EU member states have adhered to a minimum target of 75% and the Italian Ministry of Health, in line with what has been established in Europe, has set a minimum threshold of 75% coverage (given the optimal value of 95%) [39,40]; to this end, vaccination is offered actively and free-of-charge to health workers, as well as to all individuals aged sixty-five and over, as well as to the at-risk categories provided for by the 2017–2019 National Vaccination Prevention Plan (Piano Nazionale di Prevenzione Vaccinale) [41]. Nonetheless, coverage for influenza vaccination among healthcare workers falls short of the minimum targets set.

Based on these premises, the present work aims to evaluate the relationship between the knowledge, attitudes, and behaviours of healthcare professionals and their propensity towards flu vaccination, in order to understand which phenomena are most implicated in vaccine hesitancy and to develop targeted strategies to increase vaccination coverage and improve compliance among health workers. To the best of our knowledge, this is the first study to focus on the flu vaccination attitude, behaviours, and knowledge among healthcare workers in Sardinia, Italy.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Study Setting

The present study did not require ethical approval for its observational design according to the Italian law (Gazzetta Ufficiale no. 76 dated 31.3.2008).

The fact-finding survey was directed towards employees of the University Hospital of Sassari (AOU-SS). The AOU-SS is the main hospital in Sardinia for the number and heterogeneity of its professional resources (2710 employees as of 01.12.2018) and its technological resources and carries out multi-specialist activities of care, teaching, and research for the entire northern territory of Sardinia.

The organisational structure of the hospital is set out in the corporate deed (art. 3 paragraph 1 bis of Legislative Decree no. 502/92 and subsequent amendments), which identifies a total of 77 operational units. Based on the type of activity carried out, these units are grouped into macro-areas: 29 medical areas; 18 surgical areas; 30 services/other [42].

2.2. Survey Method

An anonymous self-administered questionnaire was developed on the EUSurvey digital platform (an open-source tool of the European Commission for the construction of surveys and consultations). The questionnaire was tested, adjusted, and validated through a pilot study, carried out on a convenience sample of 40 experts in public health. The internal consistency was assessed with Cronbach’s alpha test.

To assess the attitudes, behaviours, and knowledge of the AOU-SS staff regarding flu vaccination, the questionnaire was divided into 26 close-ended mandatory questions divided into 4 areas of investigation: 6 personal data questions aimed at classifying the professional profile of the participants; 7 questions related to attitudes; 3 questions about behaviours, and 10 questions about knowledge. For questionnaire compilation, it was compulsory to answer each question.

The questionnaire was administered by sending a URL code via e-mail to AOU-SS employees in the period between November 2018 and March 2019. The general information of the respondents is shown in Table 1. The attitudes, behaviours, and knowledge questions are shown in Table 2 (Results Section). In particular, the questions and the close-ended answers (coded as qualitative data) are reported in the first and second columns of the table, respectively.

Table 1.

Participants’ general information.

| General Information | Answers (Yes/No) | Yes (%) |

|---|---|---|

| 1. Gender | Male | 168/457 (36.8) |

| 2. Age (years) | 25–34 | 37/457 (8.1) |

| 35–44 | 102/457 (22.3) | |

| 45–54 | 167/457 (36.5) | |

| 55–64 | 143/457 (31.3) | |

| >65 | 8/457 (1.8) | |

| 3. Job | Physician | 163/457 (35.7) |

| Nurse | 178/457 (38.9) | |

| Other | 116/457 (25.4) | |

| 4. Area | Medical | 151/457 (33.0) |

| Surgical | 106/457 (23.2) | |

| Service/other | 200/457 (43.8) | |

| 5. Seniority (years of service) | 0–9 | 110/457 (24.1) |

| 10–19 | 129/457 (28.2) | |

| 20–29 | 156/457 (34.1) | |

| >30 | 62/457 (13.6) | |

| 6. Contact time (% working time spent in contact with the patient) | 0–25 | 95/457 (20.8) |

| 26–50 | 49/457 (10.7) | |

| 51–75 | 90/457 (19.7) | |

| 76–100 | 223/457 (48.8) |

2.3. Statistical Analysis

Data were entered on Excel (Microsoft Office, Microsoft Corporation, Redmond, WA, USA) and analysed using the STATA software 11 (StatCorp., Austin, TX, USA) and MedCalc (MedCalc Software Ltd., Ostend, Belgium). Qualitative variables were summarised with absolute and relative (percentage) frequencies.

Logistic regression analyses were performed to assess the relationship between the outcome (vaccination carried out in 2018–2019) and variables related to health workers’ attitudes, behaviours, and knowledge. The outcome was established by attributing a value of 1 if the participant underwent vaccination in 2018–2019, and a value of 0 otherwise. Only the variables that were significant in the first phase of univariate analysis were included in the multivariate model.

A two-tailed p-value of less than 0.05 was considered statistically significant.

3. Results

The invitation to participate in the compilation of the questionnaire was sent via e-mail to 2270 (83.7%) AOU-SS health workers. There were 457 (20.1%) questionnaires completed and returned.

Cronbach’s alpha reliability test showed a global value of 0.8592, which highlights the good internal consistency of the questionnaire.

The results of the descriptive analysis are shown in Table 2.

Table 2.

Descriptive analysis of the variables inherent to the health workers’ general information, attitudes, behaviours, and knowledge. The first column on the left shows the questions of the questionnaire, while the possible answers (yes/no) are shown in the “answers” column.

| Attitudes | Answers (Yes/No) | Nested Answers (%) | Yes (%) |

| 7. Do you believe that vaccinations for healthcare professionals constitute: | an obligation from a professional responsibility viewpoint? | - | 188/457 (41.1) |

| a right and a responsibility in the defence and protection of health? | - | 252/457 (55.1) | |

| an indispensable requirement for working in the health sector? | - | 187/457 (41.0) | |

| 8. What are your beliefs about the role of vaccinations in individual and collective human health? | Vaccines are often linked to serious side effects | - | 58/457 (12.7) |

| The effects of vaccination are unknown | - | 46/457 (10.1) | |

| The potential risks outweigh the potential benefits | - | 67/457 (14.7) | |

| Vaccines represent a legacy of achievement in the prevention of infectious diseases | - | 455/457 (99.6) | |

| Vaccines are important for reducing or eliminating serious infectious diseases | - | 449/457 (98.2) | |

| It is better to “go through” the disease rather than to vaccinate against it | - | 13/457 (2.8) | |

| 9. Which of the following factors do you consider to be determinants of vaccination refusal/uncertainty for healthcare professionals? | Mistrust of vaccines and vaccination practice | - | 278/457 (60.8) |

| Scepticism, negative perception of the importance of vaccines | - | 314/457 (68.7) | |

| Inadequacy of the practice for the populations’ needs | - | 185/457 (40.5) | |

| Contextual influences of a social, cultural, economic, and political nature | - | 354/457 (77.5) | |

| Other types of influences (time, cost, and lack of information) | - | 351/457 (76.8) | |

| 10. Do you believe flu vaccination for healthcare professionals is: | protection for yourself? | - | 278/457 (60.8) |

| protection for your family members? | - | 407/457 (89.1) | |

| protection for patients? | - | 428/457 (93.7) | |

| 11. Which of the following (common, rare, or only theoretical) side effects to some extent related to flu vaccination worry you? | Pain at the injection site | - | 55/457 (12.0) |

| Fever | - | 97/457 (21.2) | |

| Feeling of tiredness and/or fatigue | - | 119/457 (26.0) | |

| Diseases of the peripheral nervous system or Guillain–Barré syndrome | - | 109/457 (23.9) | |

| Allergic manifestations | - | 134/457 (29.3) | |

| No concern, the reactions are transient, minor, and very rare | - | 301/457 (65.9) | |

| 12. Would you be in favour of mandatory flu vaccination for health workers as a fundamental requirement for working within the national health system? | - | - | 267/457 (58.4) |

| * 12.a Why would you be against it? | Obligation affects individual freedom of choice | 111/190 (58.4) | - |

| Obligation is limited to specific professional categories | 50/190 (26.3) | - | |

| Obligation would expose me to a risk I had not chosen to take | 29/190 (15.3) | - | |

| 13. In a hospital setting, what do you think could be the best strategy to propose flu vaccination to health professionals? | Make vaccination mandatory | - | 244/457 (53.4) |

| Give greater visibility to the vaccination campaign | - | 437/457 (95.6) | |

| Award a bonus to employees who decide to get vaccinated | - | 149/457 (32.6) | |

| Give specific training on the topic of influenza | - | 452/457 (96.7) | |

| Behaviours | Answers (Yes/No) | Nested Answers (%) | Yes (%) |

| 14. Did you get flu vaccination during these periods? | 2014/2015 | - | 119/457 (26.0) |

| 2015/2016 | - | 104/457 (22.8) | |

| 2016/2017 | - | 108/457 (23.6) | |

| 2017/2018 | - | 132/457 (28.9) | |

| 2018/2019 | - | 140/457 (30.6) | |

| ** 14.a Are you planning to be vaccinated against flu in 2018–2019? | - | 140/317 (44.2) | - |

| 15. Did you get flu vaccination during the last 5 years? | 221/457 (48.3) | ||

| 16. Did you contract flu in the last 2 years? | - | - | 208/457 (45.5) |

| *** 16.a If you have contracted flu in the last 2 years, what action did you take? | Absence from work until complete recovery | 88/208 (42.3) | - |

| Knowledge | Answers (Yes/No) | Nested Answers (%) | Yes (%) |

| 17. Which of the following answers is a reason for not adhering to flu vaccination? | The flu vaccine is not entirely safe for health | - | 45/457 (9.8) |

| The flu vaccine is not effective in preventing seasonal flu | 119/457 (26.0) | ||

| The flu vaccine can cause serious side effects | 51/457 (11.2) | ||

| Difficulty accessing flu vaccination | 82/457 (17.9) | ||

| Cost of the vaccine | 31/457 (6.8) | ||

| 18. Do you believe that given your professional activity, the risk of contracting the flu compared to the general public is: | Greater than the general public | - | 238/457 (52.1) |

| Less than or equal to the general public | 219/457 (47.9) | ||

| 19. The sources of influenza infection are: | Healthy carriers | - | 229/457 (50.1) |

| Chronic carriers | - | 149/457 (32.6) | |

| Asymptomatic carriers | - | 284/457 (62.1) | |

| Subjects with no other clinical symptoms | - | 130/457 (28.4) | |

| 20. Which flu vaccines are currently in use in Italy? | Attenuated | - | 265/457 (57.9) |

| Split | 244/457 (53.3) | ||

| Inactivated | 300/457 (65.6) | ||

| Subunit | 208/457 (45.5) | ||

| Adjuvanted | 254/457 (55.5) | ||

| 21. Flu vaccination is recommended in the following risk categories: | over 65s | - | 455/457 (99.6) |

| pregnant women | - | 310/457 (67.8) | |

| subjects with diseases of the haematopoietic organs or chronic circulatory, respiratory, or renal conditions | - | 439/457 (96.1) | |

| subjects with diabetes or other dysmetabolic diseases | - | 401/457 (87.7) | |

| subjects with congenital or acquired illnesses that compromise the immune system | - | 378/457 (82.7) | |

| subjects who require frequent medical assistance | - | 400/457 (87.5) | |

| cohabitants of at-risk subjects | - | 418/457 (91.5) | |

| 22. Which of these measures are recommended in primary flu prevention? | Standard immunoglobulins | - | 80/457 (17.5) |

| Specific immunoglobulins | - | 101/457 (22.1) | |

| Prophylactic vaccination | - | 431/457 (94.3) | |

| Hand washing | - | 437/457 (95.6) | |

| Use of medical masks by flu patients | - | 388/457 (84.9) | |

| 23. The incubation period of influenza is: | 1 week | - | 124/457 (27.1) |

| 6–12 h | 37/457 (8.1) | ||

| 1–2 days | 282/457 (61.7) | ||

| 2 weeks | 14/457 (3.1) | ||

| 24. Influenza has a higher incidence in those aged: | <15 years old | - | 133/457 (29.1) |

| 15–64 years old | 80/457 (17.5) | ||

| over 64 years old | 244/457 (53.4) | ||

| 25. What is the most frequent complication of flu? | Pneumonia | - | 429/457 (93.9) |

| Myocarditis/pericarditis | 10/457 (2.2) | ||

| Myositis | 5/457 (1.1) | ||

| Reye syndrome | 3/457 (0.6) | ||

| Encephalitis | 4/457 (0.8) | ||

| Death | 3/457 (0.7) | ||

| I do not know | 3/457 (0.7) | ||

| 26. The influenza vaccines in use protect against viruses of type: | A and B | - | 260/457 (56.9) |

| only A | 49/457 (10.7) | ||

| A, B, and C | 148/457 (32.4) |

* Question 12.a was made accessible only to those who gave a negative answer to question no. 12, thus excluding those who gave affirmative answers (nested answers). ** Question 14.a was made accessible only to those who gave a negative answer to question no. 14, thus excluding those who gave affirmative answers (nested answers). *** Question 16.a was made accessible only to those who gave a negative answer to question no. 16, thus excluding those who gave affirmative answers (nested answers).

3.1. Attitudes

Of those interviewed, 55.1% believed that flu vaccination for health workers was a right and a responsibility in the protection of health. In addition, almost all respondents believed that vaccines were a pivotal tool for prevention and were capable of eliminating serious communicable diseases (99.6% and 98.2%, respectively). Moreover, the same interviewees considered anti-influenza vaccination for health workers as protection for patients (93.7%), and most (65.9%) showed no concern about the possible side effects of vaccination. As such, 58.4% of respondents were in favour of mandatory flu vaccination for health workers, while the majority of those not in favour (111 out of 190 respondents) believed that obligation affected individual freedom of choice. Finally, giving greater visibility to the vaccination campaign, together with a specific training activity on the topic of influenza, were considered the best strategies for proposing the flu vaccination to healthcare professionals by almost all interviewees (95.6% and 96.7%, respectively).

3.2. Behaviours

As regards the behaviour of the sample interviewed about flu vaccination, the highest percentage of vaccinated subjects (30.6%) regarding the five years observed, was attributable to the 2018/2019 season. Moreover, 44.2% of those unvaccinated in 2018/2019, stated they wished to be vaccinated. What is more, almost half (48.3%) of the respondents stated they had been vaccinated in the past 5 years. At the same time, 45.5% stated they had contracted flu during the past 2 years; of these only 42.3% of cases were absent from work until they had made a complete recovery.

3.3. Knowledge

Knowledge among those interviewed concerning flu vaccination showed that, albeit in a low percentage (26.0%), the ineffectiveness in the prevention of seasonal flu was the main reason for failing to adhere to vaccination. Only 52.1% of the respondents were aware of having a greater risk of contracting the disease than the general public, while almost all were aware that there are some at-risk categories, such as those aged over 65 (99.6%) and people with dysmetabolic diseases and diabetes (87.7%). Only 27.1% were aware of the actual incubation period of the disease, just as only 29.1% were aware that the incidence of influenza is higher among subjects <15 years old. By contrast, almost all respondents (93.9%) knew that pneumonia was the most frequent complication of influenza, and more than half (56.9%) knew that the vaccines currently in use protect against type A and type B viruses.

3.4. Logistic Regression Analysis

As regards the univariate and multivariate analysis, the variables relating to questions number 14 and 15 were excluded from the analysis, as all the respondents who were vaccinated in 2018–2019 (outcome) had received flu vaccination also in the last 5 years (at least once). Thus, this led to the exclusion from the model of the variables associated with the outcome due to the obvious collinearity. In the models, the questions relating to knowledge were categorised based on the correctness or otherwise of the answer given (correct answer = 1, otherwise = 0). The questions with nested answers were excluded from the inferential analysis, as they refer to a limited number of respondents and, therefore, are not representative of the sample as a whole. The results are shown in Table 3.

Table 3.

Univariate and multivariate analysis evaluating the relationships between the independent variables and the outcome vaccinated/unvaccinated subjects in the 2018–2019 season.

| Questionnaire Area (Item No.) | Answers | Univariate Analysis | Multivariate Analysis | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| General Information | (Yes/No) | Odds Ratio (95% CI) | p -Value | Odds Ratio (95% CI) | p -Value |

| 1. Gender | Male | 2.1 (1.4–3.2) | 0.000 | 1.5 (0.9–2.6) | 0.108 |

| 2. Age (years) | 25–34 | 1.2 (1.0–1.5) | 0.071 | - | - |

| 35–44 | |||||

| 45–54 | |||||

| 55–64 | |||||

| >65 | |||||

| 3. Job | Physician | 2.6 (1.7–4.0) | 0.000 | 2.6 (1.3–5.2) | 0.007 |

| Nurse | 0.4 (0.3–0.7) | 0.000 | 1.2 (0.6–2.5) | 0.578 | |

| Other | 0.8 (0.5–1.2) | 0.291 | - | - | |

| 4. Area | Medical | 1.3 (0.9–2.0) | 0.216 | - | - |

| Surgical | 0.4 (0.2–0.7) | 0.002 | 0.4 (0.2–0.8) | 0.010 | |

| Service/other | 1.4 (0.9–2.1) | 0.114 | - | - | |

| 5. Seniority (years of service) | 0–9 | 1.1 (0.9–1.4) | 0.187 | - | - |

| 10–19 | |||||

| 20–29 | |||||

| >30 | |||||

| 6. Contact time (% working time spent in contact with the patient) | 0–25 | 0.8 (0.7–0.9) | 0.009 | 0.7 (0.6–0.9) | 0.005 |

| 26–50 | |||||

| 51–75 | |||||

| 76–100 | |||||

| Attitudes | (Yes/No) | OR (95% CI) | p -Value | OR (95% CI) | p -Value |

| 7. Do you believe that vaccinations for healthcare professionals constitute: | an obligation from a professional responsibility viewpoint? | 2.9 (1.4–5.8) | 0.004 | 1.1 (0.4–2.9) | 0.790 |

| a right and a responsibility in the defence and protection of health? | 3.9 (0.9–17.2) | 0.071 | - | - | |

| an indispensable requirement for working in the health sector? | 4.4 (2.1–9.1) | 0.000 | 1.8 (0.7–4.9) | 0.244 | |

| 8. What are your beliefs about the role of vaccinations in individual and collective human health? | Vaccines are often linked to serious side effects | 0.6 (0.3–1.2) | 0.149 | - | - |

| The effects of vaccination are unknown | 0.4 (0.2–0.9) | 0.021 | 0.8 (0.3–2.3) | 0.739 | |

| The potential risks outweigh the potential benefits | 0.7 (0.4–1.2) | 0.196 | - | - | |

| Vaccines represent a legacy of achievement in the prevention of infectious diseases | Omitted due to collinearity | - | - | - | |

| Vaccines are important for reducing or eliminating serious infectious diseases | 3.1 (0.4–25.8) | 0.287 | - | - | |

| It is better to “go through” the disease rather than to vaccinate against it | 0.7 (0.2–2.5) | 0.551 | - | - | |

| 9. Which of the following factors do you consider to be determinants of vaccination refusal/uncertainty for healthcare professionals? | Mistrust of vaccines and vaccination practice | 1.1 (0.7–1.6) | 0.703 | - | - |

| Scepticism, negative perception of the importance of vaccines | 1.2 (0.8–1.9) | 0.405 | - | - | |

| Inadequacy of the practice with respect to the populations’ needs | 0.6 (0.4–0.9) | 0.016 | 0.7 (0.4–1.2) | 0.184 | |

| Contextual influences of a social, cultural, economic, and political nature | 1.4 (0.9–2.3) | 0.179 | - | - | |

| Other types of influences (time, cost, and lack of information) | 1.1 (0.7–1.8) | 0.723 | - | - | |

| 10. Do you believe flu vaccination for healthcare professionals is: | protection for yourself? | 5.5 (1.9–15.6) | 0.001 | 1.5 (0.3–7.5) | 0.639 |

| protection for your family members? | 7.9 (2.4–26.0) | 0.001 | 2.4 (0.5–11.7) | 0.266 | |

| protection for patients? | Omitted due collinearity | - | - | - | |

| 11. Which of the following (common, rare, or only theoretical) side effects to some extent related to flu vaccination worry you? | Pain at the injection site | 1.0 (0.6–19) | 0.962 | - | - |

| Fever | 0.6 (0.3–0.9) | 0.032 | 1.3 (0.6–2.8) | 0.478 | |

| Feeling of tiredness and/or fatigue | 0.4 (0.3–0.7) | 0.001 | 0.6 (0.3–1.2) | 0.138 | |

| Diseases of the peripheral nervous system or Guillain–Barré syndrome | 1.0 (0.7–1.6) | 0.885 | - | - | |

| Allergic manifestations | 0.8 (0.5–1.2) | 0.261 | - | - | |

| No concern, the reactions are transient, minor, and very rare | 1.8 (1.1–2.7) | 0.012 | 1.4 (0.8–2.5) | 0.202 | |

| 12. Would you be in favour of mandatory flu vaccination for health workers as a fundamental requirement for working within the national health system? | - | 4.4 (2.8–7.1) | 0.000 | 3.0 (1.3–6.9) | 0.011 |

| 13. In a hospital setting, what do you think could be the best strategy to propose flu vaccination to health professionals? | Make vaccination mandatory | 3.5 (2.2–5.4) | 0.000 | 0.8 (0.4–1.8) | 0.585 |

| Give greater visibility to the vaccination campaign | 4.2 (0.9–18.2) | 0.058 | - | - | |

| Award a bonus to employees who decide to get vaccinated | 1.7 (1.1–2.5) | 0.014 | 1.5 (0.9–2.6) | 0.114 | |

| Give specific training on the topic of influenza | 1.8 (0.5–6.5) | 0.370 | - | - | |

| Behaviours | (Yes/No) | OR (95% CI) | p -Value | OR (95% CI) | p -Value |

| 16. Did you get influenza in the last 2 years? | - | 1.1 (0.7–1.6) | 0.794 | - | - |

| Knowledge | (Yes/No) | OR (95% CI) | p -Value | OR (95% CI) | p -Value |

| 17. Which of the following answers is a reason for not adhering to flu vaccination? | The flu vaccine is not entirely safe for health | 1.4 (0.8–2.7) | 0.275 | - | - |

| The flu vaccine is not effective in preventing seasonal flu | 0.5 (0.3–0.8) | 0.002 | 1.3 (0.7–2.5) | 0.436 | |

| The flu vaccine can cause serious side effects | 1.8 (0.6–1.9) | 0.903 | - | - | |

| Difficulty accessing flu vaccination | 0.5 (0.3–0.9) | 0.034 | 0.3 (0.2–0.7) | 0.002 | |

| Cost of the vaccine | 0.6 (0.3–1.5) | 0.317 | - | - | |

| 18. Do you believe that given your professional activity, the risk of contracting the flu compared to the general public is: | Greater | 3.1 (2.1–4.8) | 0.000 | 2.5 (1.5–4.3) | 0.001 |

| 19. The sources of influenza infection are: | Healthy carriers | 1.2 (0.8–1.7) | 0.435 | - | - |

| Chronic carriers | 0.7 (0.4–1.1) | 0.099 | - | - | |

| Asymptomatic carriers | 1.2 (0.8–1.9) | 0.296 | - | - | |

| Subjects with no other clinical symptoms | 1.2 (0.8–1.7) | 0.462 | - | - | |

| 20. Which flu vaccines are currently in use in Italy? | Attenuated | 1.4 (0.9–2.0) | 0.140 | - | - |

| 21. Flu vaccination is recommended in the following risk categories: | Over 65s | Omitted due collinearity | - | - | - |

| Pregnant women | 2.7 (1.7–4.4) | 0.000 | 2.0 (1.1–3.6) | 0.018 | |

| subjects with diseases of the haematopoietic organs or chronic circulatory, respiratory, or renal conditions | 3.7(0.8–16.2) | 0.086 | - | - | |

| subjects with diabetes or other dysmetabolic diseases | 5.2 (2.0–13.3) | 0.001 | 3.1 (1.0–9.2) | 0.043 | |

| subjects with a congenital or acquired illness which compromise the immune system | 1.3 (0.7–2.2) | 0.391 | - | - | |

| subjects who require frequent medical assistance | 2.6 (1.2–5.5) | 0.012 | 1.1 (0.4–2.7) | 0.918 | |

| cohabitants of at-risk subjects | 2.6 (1.1–6.3) | 0.037 | 1.1 (0.4–3.5) | 0.826 | |

| 22. Which of these measures are recommended in primary flu prevention? | Standard immunoglobulins | 1.6 (0.9–2.9) | 0.084 | - | - |

| Specific immunoglobulins | 1.7 (0.9–2.8) | 0.054 | - | - | |

| Prophylactic vaccination | 3.6 (1.1–12.1) | 0.041 | 3.4 (0.8–13.9) | 0.089 | |

| Hand washing | 1.3 (0.5–3.8) | 0.577 | - | - | |

| Use of medical masks by flu patients | 0.7 (0.4–1.2) | 0.170 | - | - | |

| 23. The incubation period of influenza is: | 1 week | 1.4 (0.9–2.2) | 0.110 | - | - |

| 24. Influenza has a higher incidence in those aged: | <15 years old | 1.6 (1.0–2.4) | 0.039 | 1.3 (0.8–2.3) | 0.303 |

| 25. What is the most frequent complication of flu? | Pneumonia | 1.1 (0.5–2.7) | 0.807 | - | - |

| 26. The influenza vaccines in use protect against viruses of type: | A and B | 1.4 (0.9–2.1) | 0.088 | - | - |

No significant differences were observed for age, gender, and seniority with regard to the knowledge level of the respondents.

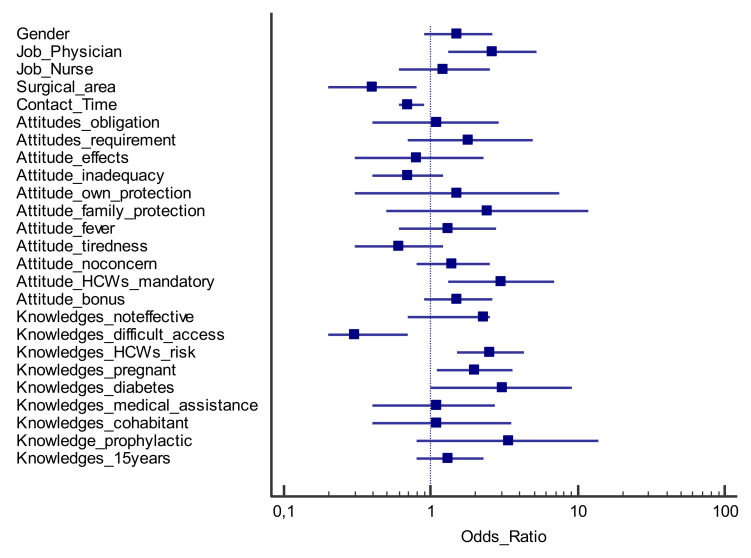

The variables that were statistically significant from the univariate analysis in relation to the outcome (staff vaccinated in the 2018–2019 season) were selected and included in a multivariate logistic regression model (Figure 1).

Figure 1.

Forest plot reporting the multivariate logistic analysis results; odds ratios and 95% confidence intervals (question_answer) concerning the observed outcome (vaccinated/unvaccinated subjects in the 2018–2019 season).

Following multivariate inferential analysis, some variables were found to be associated with the outcome. In particular, AOU-SS health workers showed a greater propensity to flu vaccination if: (i) doctors (odds ratio, OR (confidence interval, CI 95%) = 2.6 (1.3–5.2); p = 0.007); (ii) in favour of mandatory flu vaccination for their professional category (OR (CI 95%) = 3.0 (1.3–6.9); p = 0.011; (iii) aware of their greater risk of developing the disease than that of the general population (OR (CI 95%) = 2.5 (1.5–4.3); p = 0.001); (iv) are aware that some categories of people (pregnant women, OR (CI 95%) 2.0 (1.1–3.6); p = 0.018, subjects with diabetes or dysmetabolic diseases, OR (CI 95%) = 3.1 (1.0–9.2); p = 0.043) are at-risk categories. On the other hand, the health workers who did not get flu vaccination in the 2018–2019 season were those who: i) belonged to the surgical area (OR (CI 95%) = 0.4 (0.2–0.8); p = 0.010); ii) spent more time in contact with patients (OR (CI 95%) = 0.7 (0.6–0.9); p = 0.005); iii) declared difficulties in accessing vaccination (OR (CI 95%) = 0.3 (0.2–0.7); p = 0.002).

4. Discussion

The present study presents weaknesses and strengths that are discussed below. In particular, although the survey provided for the administration of a questionnaire to 2270 AOU-SS employees, only 457 questionnaires were returned (20.1%). Therefore, this could underlie a selection bias, because those who are most attentive to vaccination also are those who most likely respond to an interview on it. However, the sample that took part in the survey was mainly made up of healthcare workers who are in direct contact with patients (68.5% of the interviewees spent over 50% of their time in contact with the patient) and that, even if counterintuitive, according to the results from the logistic regression, should be those that less frequently get the flu vaccination. Therefore, these two phenomena, the former in favour and the latter against the vaccination compliance, tend to compensate each other. As a result, 30.6% of respondents stated they had been vaccinated in the current season (2018–2019). This percentage was the highest of the years observed and, although there are no official statistics on the matter, it was greater than the vaccination coverage reported by the most recent observations at national and European level [43,44,45,46]. Furthermore, adding the number of respondents vaccinated in 2018–2019 to the number who expressed willingness to be vaccinated, the forecast of vaccination coverage of the sample observed rose to 60.2%. This data suggests that the health workers who took part in the survey were highly inclined towards flu vaccination.

Despite potential selection bias, the results that emerged from the inferential analysis are in line with what has been observed in the literature by numerous other authors. For example, as has been found in recent observations, our results showed a significantly higher adhesion to vaccination by medical personnel [46,47,48,49,50,51]. On the contrary, staff working in the surgical area, as well as health workers who spent more time in contact with the patients, showed a lower adhesion to vaccination, which was also statistically significant. This result, found in other observations [52,53,54], is key to the implementation of targeted corrective measures.

As regards the results of the inferential analysis relating to the attitudes of the interviewees, our study, as mentioned, is in line with what has been observed by other authors internationally [47]. In particular, those who declared that they were vaccinated in 2018–2019, were in favour of mandatory influenza vaccination for healthcare professionals. It is interesting to note that most of those who were not in favour of mandatory vaccination believed that this obligation affected individual freedom of choice. Freedom of choice represents one of the main known determinants of vaccine hesitancy among health workers [27,30].

The survey also significantly revealed that those who adhered to vaccination were aware of a greater risk of their developing the disease than the general public, and knew the higher risks of certain categories of people (subjects with dysmetabolic diseases or diabetes; pregnant women). It was in line with what has already been observed by other scholars [55].

A noteworthy result regarded the significant difficulty declared by the health workers for easy access to the vaccination service. This aspect is crucial for the development of intervention strategies, which must facilitate access to the service in order to increase coverage [56].

There is also the potential for social desirability bias, as the study participants may have overstated that they are prone to get the flu vaccine to appear more health conscious. However, “threat of disclosure”, pertaining to respondents’ concerns about possible risks, costs, or negative consequences of truthfully reporting a sensitive behaviour was limited by the anonymity and confidentiality of the digital survey administered, thus decreasing the respondent’s concerns in admitting to some taboo (e.g., via confidentiality assurances or clever wording and framing of the sensitive item) [57,58,59].

5. Conclusions

In the context of social care, health workers are not exempt from the phenomenon of vaccine hesitancy, which is widespread also in the hospital setting. Immunising health professionals means, on the one hand, protecting the workers and the patients in their care, and on the other, curtailing the spread of infections, while maintaining a high quality of health and care services during epidemics.

Despite being offered actively and free of charge, the anti-influenza vaccination coverage of healthcare professionals continues to remain far below the minimum targets set. To counter this phenomenon, it will be essential to promote communication/information strategies tailored to healthcare professionals. These must be contextually supported by the provision of vaccination directly in the ward in order to overcome the difficulties of access to the service manifested by the respondents. The scheduling of interventions to promote influenza vaccination aimed at susceptible cohorts (e.g., surgical staff and non-medical staff) would enable an increase in vaccination coverage. Indeed, this affirmation is confirmed by the results that emerged regarding the knowledge of the staff interviewed. The results obtained, reveal that opinion tends to be favourable towards vaccination, with clear margins for improvement in terms of attitudes, knowledge, and behaviours and, thus, vaccine compliance.

Furthermore, as the occupational physicians (Ophs) are fundamental to inform the workers about the pros and cons of recommended vaccinations, an interaction with an Oph is also useful to address personal misconceptions and target false beliefs, ultimately increasing the awareness of the potential of the flu vaccine. For this reason, during the last two years, we have worked closely with Ophs to improve adherence to flu vaccination, focusing mainly on improving information (with many field events supported by the vaccinarsinsardegna.org team and also involving the basketball team Dinamo Sassari as a testimonial) and expanding the vaccine distribution network (vaccination in the hospital wards) [60,61].

To conclude, although the vaccination coverage targets set at the national level are still distant, the present work highlights which strategies should be implemented to aim for the minimum values foreseen in the near future. The low questionnaire response rate suggested that who more likely responded to the questionnaire were in favour of flu vaccination. Consequently, the vaccination propensity among the healthcare workers we observed might be even lower than expected.

On the other hand, the actual Covid-19 pandemic could represent an opportunity of fighting the vaccine hesitancy propensity among Italian healthcare workers and AOU-SS healthcare professionals heavily hit by the virus.

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to thank Emma Dempsey for the English Language revision.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, A.A. (Antonella Arghitt)., M.D. and P.C.; data curation, M.D., D.G., A.S. and P.C.; formal analysis, A.A. (Antonella Arghitt), M.D., A.A. (Antonio Azara) and P.C.; funding acquisition, P.C.; investigation, A.A. (Antonella Arghitt), M.D., A.A. (Antonio Azara), D.G., A.S., B.C. and P.C.; methodology, A.A. (Antonella Arghitt), M.D., A.A. (Antonio Azara), B.C. and P.C.; software, M.D. and P.C.; supervision, P.C.; validation, B.C.; writing—original draft, A.A. (Antonella Arghitt), M.D., A.A. (Antonio Azara) and D.G.; writing—review and editing, P.C. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This study was supported by “Fondo di Ateneo per la Ricerca 2019”, University of Sassari.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

References

- 1.World Health Organization Influenza. Global Influenza Program. [(accessed on 18 February 2020)]; Available online: http://www.who.int/influenza/en/

- 2.World Health Organization Influenza. Global Influenza Strategy 2019–2030. [(accessed on 18 February 2020)]; Available online: https://www.who.int/influenza/global_influenza_strategy_2019_2030/en/

- 3.Iuliano A.D., Roguski K.M., Chang H.H., Muscatello D.J., Palekar R., Tempia S., Cohen C., Gran J.M., Schanzer D., Cowling B.J., et al. Estimates of global seasonal influenza-associated respiratory mortality: A modelling study. Lancet. 2018;391:1285–1300. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(17)33293-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.ECDC/WHO Flu News Europe. Joint ECDC – WHO/Europe Weekly Influenza Update. [(accessed on 18 February 2020)]; Available online: https://flunewseurope.org/

- 5.Arghittu A., Dettori M., Masia M.D., Azara A., Dempsey E., Castiglia P. Social deprivation indexes and anti-influenza vaccination coverage in the elderly in Sardinia, Italy, with a focus on the Sassari municipality. J. Prev. Med. Hyg. 2019;59:E45–E50. doi: 10.15167/2421-4248/jpmh2018.59.4s2.1077. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Gasparini R., Amicizia D., Lai P.L., Rossi S., Panatto D. Effectiveness of adjuvanted seasonal influenza vaccines (Inflexal V ® and Fluad ®) in preventing hospitalization for influenza and pneumonia in the elderly: A matched case-control study. Hum. Vaccin Immunother. 2013;9:144–152. doi: 10.4161/hv.22231. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Rosano A., Bella A., Gesualdo F., Acampora A., Pezzotti P., Marchetti S., Ricciardi W., Rizzo C. Investigating the impact of influenza on excess mortality in all ages in Italy during recent seasons (2013/14–2016/17 seasons) Int. J. Infect. Dis. 2019;88:127–134. doi: 10.1016/j.ijid.2019.08.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Ministero della Salute Influenza. Sistema di Sorveglianza InfluNet. [(accessed on 18 February 2020)]; Available online: http://www.salute.gov.it/portale/influenza/dettaglioContenutiInfluenza.jsp?lingua=italiano&id=704&area=influenza&menu=vuoto.

- 9.Peasah S.K., Azziz-Baumgartner E., Bresee J., Meltzer M.I., Widdowson M.A. Influenza cost and cost-effectiveness studies globally – A review. Vaccine. 2013;31:5339–5348. doi: 10.1016/j.vaccine.2013.09.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.De Francisco Shapovalova N., Donadel M., Jit M., Hutubessy R. A systemmatic review of the social and economic burden of influenza in low- and middle-income countries. Vaccine. 2015;33:6537–6544. doi: 10.1016/j.vaccine.2015.10.066. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Bartolozzi G. In: Vaccini e Vaccinazioni. Masson E., editor. Elsevier; Amsterdam, The Netherlands: 2012. [Google Scholar]

- 12.Ministero della Salute Dati Coperture Vaccinali. [(accessed on 18 February 2020)]; Available online: http://www.salute.gov.it/portale/influenza/dettaglioContenutiInfluenza.jsp?lingua=italiano&id=679&area=influenza&menu=vuoto.

- 13.Bridges C.B., Kuehnert M.J., Hall C.B. Transmission of influenza: Implications for control in health care settings. Clin. Infect. Dis. 2003;37:1094–1101. doi: 10.1086/378292. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.World Health Organization Pandemic Influenza Risk Management: A WHO Guide to Inform and Harmonize National and International Pandemic Preparedness and Response. [(accessed on 18 February 2020)]; Available online: https://apps.who.int/iris/bitstream/handle/10665/259893/WHO-WHE-IHM-GIP-2017.1-eng.pdf?sequence=1&isAllowed=y.

- 15.Gentili D., Bardin A., Ros E., Piovesan C., Ramigni M., Dalmanzio M., Dettori M., Filia A., Cinquetti S. Impact of Communication Measures Implemented During a School Tuberculosis Outbreak on Risk Perception among Parents and School Staff, Italy, 2019. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health. 2020;17:911. doi: 10.3390/ijerph17030911. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Sandman P. Outrage Prediction and Management. [(accessed on 15 September 2018)]; Available online: http://www.psandman.com/handouts/sand58.pdf.

- 17.World Health Organization Outbreak Communication: Best Practices for Communicating with the Public during an Outbreak: Report of the WHO Expert Consultation on Outbreak Communications held in Singapore, 21–23 September 2004. [(accessed on 30 January 2020)];2004 Available online: https://apps.who.int/iris/handle/10665/69138.

- 18.Rubin G.J., Amlôt R., Pege L., Wessely S. Public perceptions, anxiety, and behaviour change in relation to the swine flu outbreak: Cross sectional telephone survey. BMJ. 2009;339:b2651. doi: 10.1136/bmj.b2651. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Smith R.D. Responding to global infectious disease outbreaks: Lessons from SARS on the role of risk perception, communication and management. Soc. Sci. Med. 2006;63:3113–3123. doi: 10.1016/j.socscimed.2006.08.004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Tumpey A.J., Daigle D., Nowak G. Communicating During an Outbreak or Public Health Investigation, CDC, Epidemic Intelligence Service. [(accessed on 30 January 2020)]; Available online: https://www.cdc.gov/eis/field-epi-manual/chapters/%20Communicating-Investigation.html.

- 21.Dettori M., Arru B., Azara A., Piana A., Mariotti G., Camerada M.V., Stefanelli P., Rezza G., Castiglia P. In the Digital Era, Is Community Outrage a Feasible Proxy Indicator of Emotional Epidemiology? The Case of Meningococcal Disease in Sardinia, Italy. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health. 2018;15:1512. doi: 10.3390/ijerph15071512. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Azara A., Dettori M., Castiglia P., Piana A., Durando P., Parodi V., Salis G., Saderi L., Sotgiu G. Indoor Radon Exposure in Italian Schools. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health. 2018;15:749. doi: 10.3390/ijerph15040749. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Dettori M., Azara A., Loria E., Piana A., Masia M.D., Palmieri A., Cossu A., Castiglia P. Population Distrust of Drinking Water Safety. Community Outrage Analysis, Prediction and Management. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health. 2019;16:1004. doi: 10.3390/ijerph16061004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Carducci A.L., Fiore M., Azara A., Bonaccorsi G., Bortoletto M., Caggiano G., Calamusa A., De Donno A., De Giglio O., Dettori M., et al. Environment and health: Risk perception and its determinants among Italian university students. Sci. Total Environ. 2019 doi: 10.1016/j.scitotenv.2019.07.201. in press. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Larson H.J., Jarrett C., Eckersberger E., Smith D.M., Paterson P. Understanding vaccine hesitancy around vaccines and vaccination from a global perspective: A systematic review of published literature, 2007–2012. Vaccine. 2014;32:2150–2159. doi: 10.1016/j.vaccine.2014.01.081. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Opel D.J., Taylor J.A., Mangione-Smith R., Solomon C., Zhao C., Catz S., Martin D. Valid-ity and reliability of a survey to identify vaccine-hesitant parents. Vaccine. 2011;29:6598–6605. doi: 10.1016/j.vaccine.2011.06.115. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.SAGE Working Group on Vaccine Hesitancy. [(accessed on 19 February 2020)]; Available online: http://www.who.int/%20immunization/sage/sage%20wg%20vaccine%20hesitancy%20apr12/en/

- 28.Dube E., Gagnon D., Nickels E., Jeram S., Schuster M. Mapping vaccine hesitancy-country-specific characteristics of a global phenomenon. Vaccine. 2014;32:6649–6654. doi: 10.1016/j.vaccine.2014.09.039. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.La Torre G., Miccoli S., Ricciardi W. The Italian alliance for vaccination strategies: Facebook as a learning tool for preventive medicine and public health. Hum. Vaccines Immunother. 2014;10:2910–2914. doi: 10.4161/21645515.2014.970497. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Karafillakis E., Dinca I., Apfel F., Cecconi S., Wűrz A., Takacs J., Suk J., Celentano L.P., Kramarz P., Larson H.J. Vaccine hesitancy among healthcare workers in Europe: A qualitative study. Vaccine. 2016;34:5013–5020. doi: 10.1016/j.vaccine.2016.08.029. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Betsch C. Opportunities and challenges of Web 2.0 for vaccination decisions. Vaccine. 2012;30:3727–3733. doi: 10.1016/j.vaccine.2012.02.025. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Stockwell M.S., Fiks A.G. Utilizing health information technology to improve vaccine communication and coverage. Hum. Vaccines Immunother. 2013;8:1802–1811. doi: 10.4161/hv.25031. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Advisory Committee on Immunization Practices. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) Immunization of health-care personnel: Recommendations of the Advisory Committee on Immunization Practices (ACIP) MMWR Recomm. Rep. 2011;60:1–45. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Gruppo di Studio Conferenza Nazionale “Medice cura te ipsum” La Carta di Pisa delle vaccinazioni negli operatori sanitari; The Pisas’ Paper of Vaccinations in Healthcare Professionals; Pisa il, Italy. 27–28 March 2017; [(accessed on 2 May 2020)]. Available online: https://gimpios.it/r.php?v=2904&a=29262&l=334060&f=allegati/02904_2017_04/fulltext/155-157_CartaPisa.pdf. [Google Scholar]

- 35.CDC Influenza (Flu). CDC Recommends. [(accessed on 18 February 2020)]; Available online: https://www.cdc.gov/flu/prevent/different-flu-vaccines.htm.

- 36.CDC Healthcare Infection Control Practices Advisory Committee (HICPAC) [(accessed on 18 February 2020)]; Available online: https://www.cdc.gov/flu/professionals/infectioncontrol/healthcaresettings.htm.

- 37.Galanakis E., Jansen A., Lopalco P.L., Giesecke J. Ethics of mandatory vaccination for healthcare workers. [(accessed on 30 January 2020)];EuroSurveillance. 2013 18:20627. doi: 10.2807/1560-7917.ES2013.18.45.20627. Available online: http://www.eurosurveillance.org/ViewArticle.aspx?ArticleId=20627. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Worksite: Seasonal Influenza Vaccinations Using Interventions with On-Site, Free, Actively Promoted Vaccinations—Healthcare Workers. [(accessed on 30 January 2020)]; Available online: https://www.healthypeople.gov/2020/tools-resources/evidence-based-resource/worksite-seasonal-influenza-vaccinations-using.

- 39.World Health Organization How to Implement Seasonal Influenza Vaccination of Health Workers. [(accessed on 28 February 2020)]; Available online: https://apps.who.int/iris/rest/bitstreams/1238564/retrieve.

- 40.Ministero della Salute Prevenzione e Controllo dell’Influenza: Raccomandazioni per la stagione 2019–2020. [(accessed on 30 January 2020)]; Available online: http://www.salute.gov.it/portale/influenza/dettaglioContenutiInfluenza.jsp?lingua=italiano&id=685&area=influenza&menu=vuoto.

- 41.Ministero della Salute Piano Nazionale di Prevenzione Vaccinale 2017–2019. [(accessed on 30 January 2020)]; Available online: http://www.salute.gov.it/portale/vaccinazioni/dettaglioContenutiVaccinazioni.jsp?lingua=italiano&id=4828&area=vaccinazioni&menu=vuoto.

- 42.Azienda Ospedaliero Universitaria di Sassari Atto Aziendale. [(accessed on 30 January 2020)];2017 Available online: https://www.aousassari.it/index.php?xsl=17&s=11&v=9&c=2849&id=304118&nodesc=1.

- 43.Mannocci A., Ursillo P., Bontempi C., Sferrazza A., La Torre G. Prevalence of influenza vaccination among physicians and related enhancing and preventing factors in Italy. Rev. Health Care. 2010;1:23–30. doi: 10.7175/rhc.v1i1.15. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 44.La Torre G., Mannocci A., Ursillo P., Bontempi C., Firenze A., Panico M.G., Sferrazza A., Ronga C., D’Anna A., Amodio E., et al. Prevalence of influenza vaccination among nurses and ancillary workers in Italy: Systematic review and meta analysis. Hum. Vaccines. 2011;7:728–733. doi: 10.4161/hv.7.7.15413. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Seasonal Influenza Vaccination and Antiviral Use in EU/EEA Member States Technical Report. [(accessed on 18 February 2020)]; Available online: https://www.ecdc.europa.eu/en/publications-data/seasonal-influenza-vaccination-antiviral-use-eu-eea-member-states.

- 46.Maltezou H.C., Poland G.A. Vaccination policies for healthcare workers in Europe. Vaccine. 2014;32:4876–4880. doi: 10.1016/j.vaccine.2013.10.046. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Alicino C., Iudici R., Barberis I., Paganino C., Cacciani R., Zacconi M., Battistini A., Bellina D., Di Bella A.M., Talamini A., et al. Influenza vaccination among healthcare workers in Italy. Hum. Vaccines Immunother. 2015;11:95–100. doi: 10.4161/hv.34362. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Hollmeyer H., Hayden F., Mounts A., Buchholz U. Review: Interventions to increase influenza vaccination among healthcare workers in hospitals. Influenza Other Respir. Viruses. 2013;7:604–621. doi: 10.1111/irv.12002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Sartor C., Tissot-Dupont H., Zandotti C., Martin F., Roques P., Drancourt M. Use of a mobile cart influenza program for vaccination of hospital employees. Infect. Control. Hosp. Epidemiol. 2004;25:918–922. doi: 10.1086/502320. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Leitmeyer K., Buchholz U., Kramer M., Schenkel K., Stahlhut H., Köllstadt M., Haas W., Meyer C. Influenza vaccination in German health care workers: Effects and findings after two rounds of a nationwide awareness campaign. Vaccine. 2006;24:7003–7008. doi: 10.1016/j.vaccine.2006.04.040. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Doebbeling B.N., Edmond M.B., Davis C.S., Woodin J.R., Zeitler R.R. Influenza vaccination of health care workers: Evaluation of factors that are important in acceptance. Prev. Med. 1997;26:68–77. doi: 10.1006/pmed.1996.9991. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Liu H., Tan Y., Zhang M., Peng Z., Zheng J., Qin Y., Guo Z., Yao J., Pang F., Ma T., et al. An Internet-Based Survey of Influenza Vaccination Coverage in Healthcare Workers in China, 2018/2019 Season. Vaccines. 2019;26:8. doi: 10.3390/vaccines8010006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.De Juanes J.R., Garcia D.C., Arrazola M.P., Jaen F., Sanz M.I., Gonzalez A. Influenza vaccination coverage among hospital personnel over three consecutive vaccination campaigns (2001–2002 to 2003–2004) Vaccine. 2007;25:201–204. doi: 10.1016/j.vaccine.2005.10.057. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Valour F., Maulin L., Ader F., Perpoint T., Champagne H., David G., Boibieux A., Biron F., Peyramond D., Chidiac C. Vaccination against influenza: Results of a study on vaccination coverage among health care workers in the Croix-Rousse Hospital (Hospitals of Lyon) Med. Mal. Infect. 2007;37:51–60. doi: 10.1016/j.medmal.2006.10.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Gabutti G., Conforti G., Tomasi A., Kuhdari P., Castiglia P., Prato R., Memmini S., Azzari C., Rosati G.V., Bonanni P. Why, when and for what diseases pregnant and new mothers “should” be vaccinated. Hum. Vaccines Immunother. 2017;13:283–290. doi: 10.1080/21645515.2017.1264773. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Dharmapalan D. Influenza. Indian J. Pediatr. 2020 doi: 10.1007/s12098-020-03214-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Koivula A., Räsänen P., Sarpila O. Examining Social Desirability Bias in Online and Offline Surveys. Lect. Notes Comput. Sci. 2019:145–158. doi: 10.1007/978-3-030-22646-6_11. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Ricco’ M., Vezzosi L., Gualerzi G., Balzarini F., Capozzi V.A., Volpi L. Knowledge, attitudes, beliefs and practices of obstetrics-gynecologists on seasonal influenza and pertussis immunizations in pregnant women: Preliminary results from North-Western Italy. Minerva Ginecol. 2019;71:288–297. doi: 10.23736/S0026-4784.19.04294-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Masia M.D., Solinas G., Piana A., Dettori M., Sotgiu G., Castiglia P. Smoking habit and behaviour among health professionals. Annali di Igiene. 2006;18:261–269. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Riccò M., Cattani S., Casagranda F., Gualerzi G., Signorelli C. Knowledge, attitudes, beliefs and practices of Occupational Physicians towards seasonal influenza vaccination: A cross-sectional study from North-Eastern Italy. J. Prev. Med. Hyg. 2017;58:E141–E154. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.#PerchéSì: Sassari Wins Award for Best Project in Italy. [(accessed on 30 April 2020)]; Available online: https://www.vaccinarsinsardegna.org/en/notizie/2019/10/premiato-sassari-miglior-progetto-comunicazione-vaccinale.