Abstract

Background

We have recently developed a highly accurate urine-based test, named Urodiag®, associating FGFR3 mutation and DNA methylation assays for recurrence surveillance in patients with low-, intermediate-, and high-risk NMIBC. Previously, the detection of four FGFR3 mutations (G372C, R248C, S249C and Y375C) required amplification steps and PCR products were analyzed by capillary electrophoresis (Allele Specific-PCR, AS-PCR), which was expensive and time-consuming. Here, we present the development a novel ultra-sensitive multiplex PCR assay as called “Mutated Allele Specific Oligonucleotide-PCR (MASO-PCR)”, generating a cost-effective, simple, fast and clinically applicable assay for the detection of FGFR3 mutations in voided urine.

Methods

Comparative clinical performances of MASO-PCR and AS-PCR technologies were performed from 263 urine DNA samples (87 FGFR3 mutated and 176 FGFR3 wild-type). In the development of Urodiag® PCR Kit, we studied the stability and reproducibility of each all-in-one PCR master mix (single reaction mixture including all the necessary PCR components) for MASO-PCR and QM-MSPCR (Quantitative Multiplex Methylation-Specific PCR to co-amplify SEPTIN9, HS3ST2 and SLIT2 methylated genes) assays.

Results

Complete concordance (100%) was observed between the MASO-PCR and AS-PCR results. Each PCR master mix displayed excellent reproducibility and stability after 12 months of storage at − 20 °C, with intra-assay standard deviations lower than 0.3 Ct and coefficient of variations (CV) lower than 1%. The limit of detection (LoD) of MASO-PCR was 5% mutant detection in a 95% of wild-type background. The limit of quantification (LoQ) of QM-MSPCR was 10 pg of bisulfite-converted DNA.

Conclusions

We developed and clinically validated the MASO-PCR assay, generating cost-effective, simple, fast and clinically applicable assay for the detection of FGFR3 mutations in urine. We also designed the Urodiag® PCR Kit, which includes the MASO-PCR and QM-MSPCR assays. Adapted to routine clinical laboratory (simplicity, accuracy), the kit will be a great help to urologists for recurrence surveillance in patients at low-, intermediate- and high-risk NMIBC. Reducing the number of unnecessary cystoscopies, it will have extremely beneficial effects for patients (painless) and for the healthcare systems (low cost).

Keywords: MASO-PCR, NMIBC, Urodiag® PCR kit, Urine-based laboratory test, Surveillance, Mutation and methylation markers

Background

Nowadays, the Bladder cancer (BCa) remains a serious public health issue. In 2018, the global incidence of BCa was estimated at around 550,000 new cases, ranking the disease as the 7th among cancers [1]. In the primary BCa diagnosis, the majority (> 70%) are non-invasive bladder cancers (NMIBC), including stages Ta, T1 and Tis (carcinoma in situ) and nearly 30% with muscle invasive bladder cancer (MIBC) (stages T2 to T4) [2]. The primary treatment of patients with NMIBC is transurethral resection of bladder tumor. Despite the treatment, more than 70% of them will develop a recurrence in 2 years (90% in 15 years) and therefore be followed by periodic cystoscopy and urinary cytology [2]. BCa is the most expensive of all cancers [3]. Cystoscopy is an uncomfortable invasive exam and cytology presents a very low sensitivity to detect NMIBC at low risk [4]. In this context, the development of reliable and affordable tools to detect recurrence is a challenge. Genetic and epigenetic alterations in DNA have been reported in the development and progression of bladder cancer [5]. In the mutational path, the fibroblast growth factor receptor 3 gene (FGFR3) appears to be the most frequently mutated gene in BCa. A dozen FGFR3 mutations have been found in this disease [6, 7], but four of them (G372C, R248C, S249C, and Y375C) account for > 95% cases [8]. These four mutations were found in the urine and then proposed as a molecular tool for the diagnosis and monitoring of patients with NMIBC at low risk [9–11]. Likewise, epigenetic modifications, such as DNA hypermethylation, have been shown to play a key role in BCa [12–16]. Like Serizawa’s work [17], we have also shown that detection of FGFR3 mutations combined with DNA methylation analysis could be is an excellent strategy to develop an accurate urine-based test in the surveillance of patients treated for NMIBC [18]. Here, we developed and clinically validated the MASO-PCR assay for the detection of FGFR3 mutations in urine. We also presented the design of the Urodiag® PCR Kit, a new urine-based lab test to monitor NMIBC patients with low-, intermediate and high-risk.

Methods

Urine collection and capture of exfoliated bladder cells with a membrane filter

Urine samples (100 ml) were collected (n = 26) from the first miction in the morning into a clean sterile container. Urine samples were pooled and stored at 4 °C for up to 72 h prior analysis. Each healthy donor gave consent before study participation. One hundred milliliter of each pooled urine sample were filtered through a single-use syringe-filter (Filter), presenting a nylon disc filter of 11 μm porosity and 25 mm diameter (Merck-Millipore). The Filter was rinsed with 5 ml of 1X PBS (pH 7.4).

Urine DNA extraction

Urine DNA isolation has been carried out directly from bladder cells captured on Filter using the QIAamp DNA Blood Mini Kit (Qiagen). If the Filter has been stored at − 20 °C, it has to be left 5–10 min at RT be before DNA extraction. The lysis buffer (220 μl 1X PBS, 22 μl Proteinase K and 220 μl AL buffer) were added on the filter and then passed 3 times through a syringe equipped with a 21 gauge needle (Terumo) to shear genomic DNA. The lysate was incubated at 56 °C for 15 min into a 2 ml tube. Subsequent processing was done according to the DNA purification protocol. All centrifugation steps were carried out in a benchtop microcentrifuge (14,000 RPM) at RT. DNA was eluted from the column into a clean 1.5 ml tube by adding 50 μl of AE buffer to the column. DNA concentration was determined with Qubit 4 fluorometer (Invitrogen) and the highly sensitive Qubit quantification assay. All genomic DNA samples were diluted or concentrated to obtain a final concentration of 1.25 ng/μl. All samples were examined for DNA (5 ng) integrity via PCR amplification of the GLOBIN gene.

Reproducibility and stability study

We studied the reproducibility of the urine filtration (17 urine samples belonging to Pool 1 to 4). We also studied the stability of filters, recovered after filtration (9 filters belonging to Pool 5 to 7), according to temperature and storage time. This study requires the following steps: DNA extraction from filter, DNA quantification and PCR amplification of the GLOBIN gene.

Bisulfite DNA modification

Thirty nanograms of universal methylated human DNA standard (Zymo Research) were modified by the EZ DNA Methylation kit (Zymo Research) according to the manufacturer’s instructions. All the centrifugation steps were carried out in a benchtop microcentrifuge (14,000 rpm) at RT. The DNA modification was performed by incubation steps, at 37 °C for 15 min then at 50 °C for 15 h30 (overnight), in a thermal cycler. Bisulfite DNA conversion was eluted from the column tube by adding 10 μl of M-Elution buffer into a clean 1.5 ml.

Multiplex real-time PCR

All PCR reactions were performed on the real-time PCR instrument StepOnePlus™ (Thermo Fischer Scientific). The PCR cycling parameters were: initial denaturation at 95 °C for 5 min followed by 40 cycles of 15 s at 95 °C, 45 s at 60 °C. The fluorescence data was acquired at the end of each cycle.

FGFR3 mutation analysis using mutated allele specific oligonucleotide-PCR (MASO-PCR)

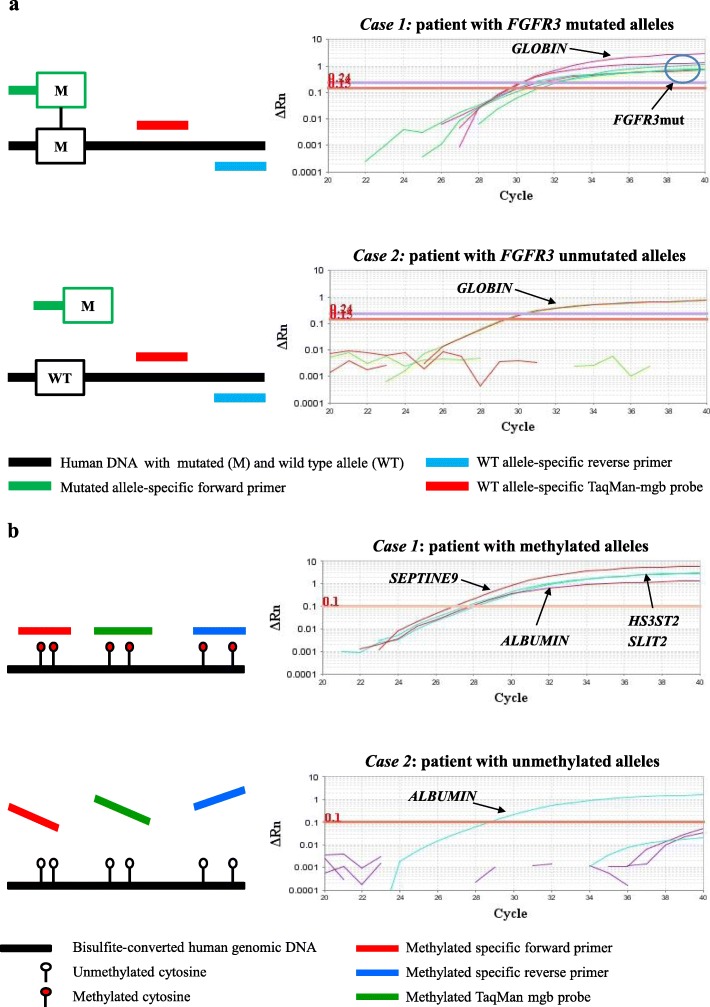

The MASO-PCR technology (Fig. 1a) was performed to simultaneously detect four mutations of the FGFR3 gene (FGFR3mut) with 6Fam-S249C and Vic-Y375C (MASO-PCR1) and 6Fam-R248C and Vic-G372C (MASO-PCR2). PCR was conducted with 4 μl (5 ng) of DNA template and 16 μl 1X Quantifast Multiplex PCR (Qiagen), 500 nM of primers (Eurogentec) and 200 nM of TaqMan-mgb probes (Thermo Fischer Scientific). The DNA integrity has been checked by amplification of the Ned-GLOBIN gene. All primers and probes are listed in Table 1a

Fig. 1.

a–b Design of Mutation and Methylation PCR assays. The diagram 2a illustrates the Mutation assay with the position of the primers and fluorescent probes used for detection of human FGFR3 mutations (G372C, R248C, S249C, and Y375C) by MASO-PCR. The diagram 2b illustrates the Methylation assay with the position of the primers and fluorescent probes used in quantifying methylation degree of HS3ST2, SEPTIN9, and SLIT2 genes by QM-MSPCR. In both assays, the amplification curves are shown as examples, with Cts values above the established threshold as positive (Case 1) and below the threshold as negative (Case 2)

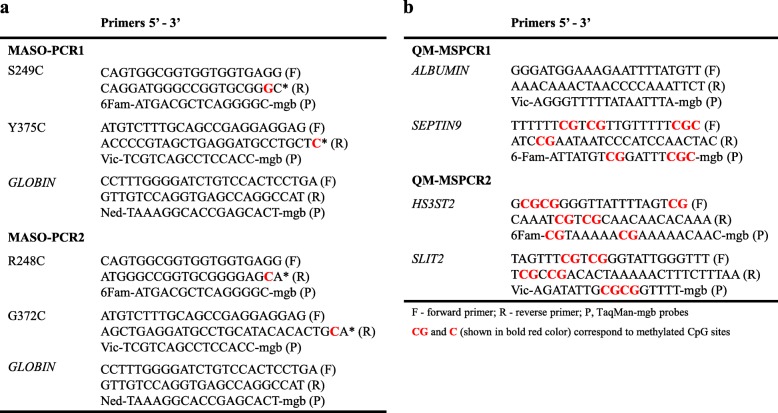

Table 1.

Primers sequences for MASO-PCR and QM-MSPCR

Methylation analysis using quantitative multiplex methylation specific-PCR (QM-MSPCR)

We performed two QM-MSPCR (Fig. 1b) for co-amplification of 6Fam-SEPTIN9 with Vic-ALBUMIN (QM-MSPCR1) and 6Fam-HS3ST2 with Vic-SLIT2 (QM-MSPCR2). All reactions were performed with 4 μl of bisulfite-converted positive control DNA (100% methylated) and 16 μl of PCR mix containing 1x KAPA PROBE FAST qPCR Master Mix (KAPA Biosystems), 400 nM primers (Eurogentec) and 250 nM TaqMan-mgb probes (Thermo Fischer Scientific). ALBUMIN sequence has been designed without CpG site and used for normalizing the DNA amounts. All primers and probes are presented in Table 1b.

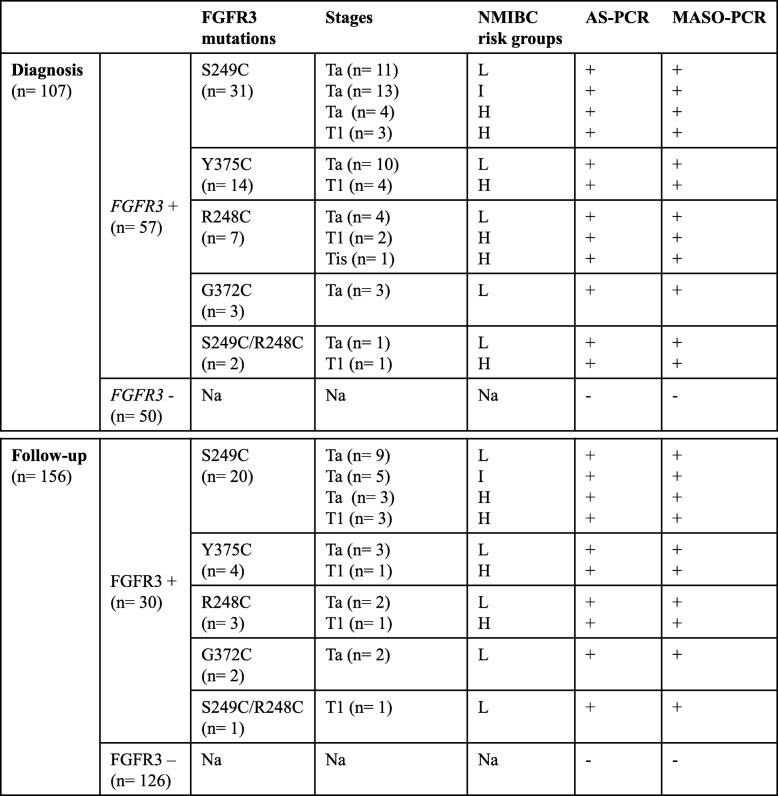

Detection of FGFR3 mutations using MASO-PCR in patients with NMIBC

We selected 263 urine DNA samples, including 176 FGFR3 wild-type (wt) and 87 FGFR3-mutated (mut) previously validated by AS-PCR, from NMIBC patients (AUVES cohort, project reference RECF0998-PHRC 2003) [11]. For initial diagnosis the distribution of patients (n = 57) among low (L)/intermediate (I) and, high (H)-risk NMIBC was 51%/23 and 26%. For follow-up the distribution of patients (n = 30) among L/I and H-risk NMIBC was 56%/17 and 27%. The distribution of mutations was: For initial diagnosis (n = 107): FGFR3mut (n = 57): S249C (n = 31), Y375C (n = 14), R248C (n = 7), G372C (n = 3) and R248C/S249C (n = 2), and FGFR3wt (n = 50). For follow-up (n = 156): FGFR3mut (n = 30): S249C (n = 20), Y375C (n = 4), R248C (n = 3), G372C (n = 2) and R248C/S249C (n = 1), and FGFR3wt (n = 126).

MASO-PCR: FGFR3 positive control, primer specificity, and determination of limit of detection (LoD)

Construction of the control plasmids containing FGFR3 mutations

Positive control plasmids were designed to incorporate the FGFR3 mutations into pMA-T vector (GeneArt, ThermoFisher Scientific). Each positive control plasmid was confirmed by sequencing before use.

Primer pair specificity

We used the same FGFR3 primer pairs (Table 1a) to amplify FGFR3 mutations with the Fast SYBR Green PCR master mix (SG-PCR, ThermoFisher Scientific). PCR reactions (20 μl) were performed, in duplicate onto two separated runs, with a 1X SG (10 μl), 200 nM of primers and FGFR3mut plasmid (4 μl). The thermal cycling conditions included an initial denaturation at 95 °C for 3 min followed by 40 cycles: 95 °C for 3 s and 60 °C for 20 s. The melting temperature (Tm) of each amplicon was calculated by the StepOnePlus software (Life Technologies) and also estimated by Howley’s formula: [67.5 + (0.41* %G-C) - (395/length of amplicon)].

LoD for analysis of FGFR3 mutations

The diploid human genome comprises about 6.109 base pairs (bp). Plasmids (2.50 ng/μl) were diluted at 2.106 in the standard human DNA (FGFR3wt, 2.50 ng/μl), leading to a 1:1 ratio (FGFR3mut/FGFR3wt) and dilutions were used as FGFR3 positive controls. To determine the LoD, a serial dilution series of the each FGFR3 positive control was produced at 50, 10, 5, and 1% with FGFR3wt (1.25 ng/μl). 5 ng of each dilution were amplified by MASO-PCR with a predefined positive threshold (ΔRn) at 0.15 for GLOBIN, S249C, Y375C, G372C and 0.24 for R248C. All dilutions were amplified and then analyzed in duplicate on the same plate to PCR in two independent runs.

QM-MSP: positive control and determination of the limit of quantification (LoQ)

The LoQ of each gene was determined for QM-MSPCR1 and QM-MSPCR2 by performing a dilution range with 10, 1, 0.1 and 0.01 ng of bisulfite-converted positive control DNA (100% methylated). The limit of DNA quantity and amplification efficiency (E) were analysed using a threshold value (ΔRn) of 0.10. Each dilution was done in duplicate on the same PCR plate in two independent runs.

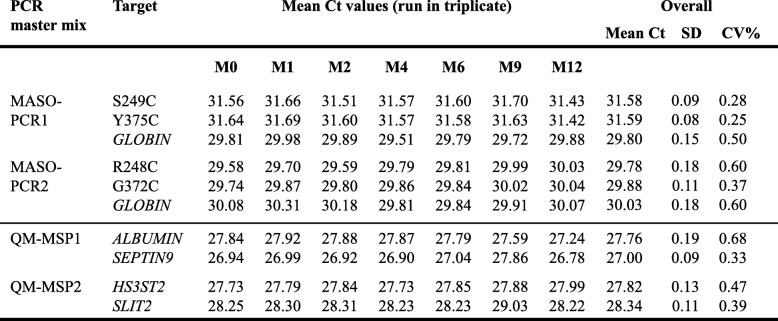

Stability and reproducibility study of all-in-one PCR master mixes

The all-in-one PCR master mixes were prepared in a single reaction mixture including all PCR components for mutation and methylation assays. We studied the stability of each all-in-one PCR master mix by MASO-PCR1,2 and QM-MSPCR1,2 from aliquots that were run in triplicate and stored at − 20 °C for 0, 1, 2, 3, 4, 6, 9 and 12 months.

Results

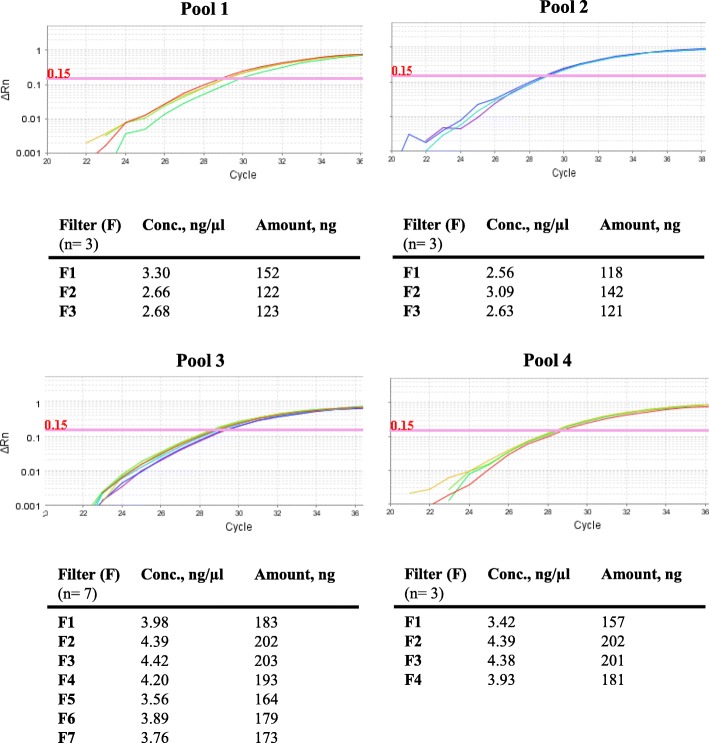

Reproducible and efficient DNA extraction from bladder cells captured on a membrane filter

To assess if filtration allows capturing the fraction of bladder cells in the sample, DNA was isolated and amplified using real-time PCR. Urine filtration was reproducibly obtained for 17 pooled urine samples belonging to Pool 1 to 4. In Fig. 2, we have reported the amounts of DNA (mean ± standard deviation) recovered from each filter (F) with 132 ± 17 ng (Pool 1, n = 3), 128 ± 13 ng (Pool 2, n = 3), 187 ± 15 ng (Pool 3, n = 7) and 185 ± 21 ng (Pool 4, n = 4). The integrity of each extracted urinary DNA (10 ng) was confirmed by amplification of the GLOBIN gene.

Fig. 2.

DNA integrity assessed by PCR amplification of GLOBIN gene. DNA concentrations were determined by fluorometry. The GLOBIN gene was amplified with an amount of urine DNA comprised between 10 and 18 ng (4 μl of DNA sample) from each Filter (F). Amplification curves are shown from Pool 1 to Pool 4, respectively

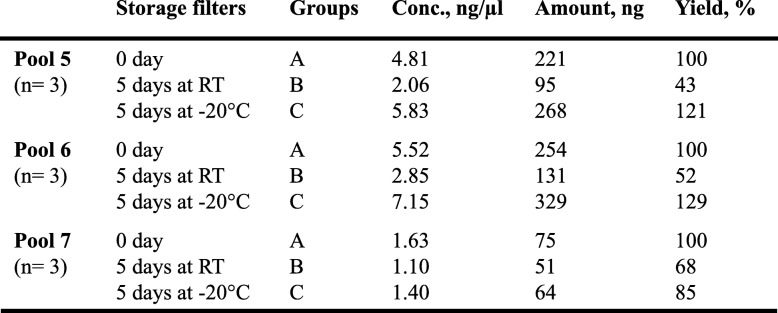

Effects of filter storage conditions

Concentration and recovery rate of the genomic DNA (Pools 5 to 7) according to filter storage conditions were summarized in Table 2. Filters of groups B (5 days at room temperature, RT) and C (5 days at − 20 °C) were compared to filters belonging to group A (0 day of storage). No significant differences were found among A and C, but there is a significant difference between A and B. Indeed, the DNA yields of groups A, B and C were 100%, 54 ± 13% (mean ± standard deviation) and 112 ± 23%, respectively. We have successfully verified the integrity of each isolated DNA by amplifying a segment of the GLOBIN gene. The amount of DNA obtained under all these conditions was greater than 40 ng, corresponding to the amount required to perform the test. In this study, we showed that the filter could be stored for 5 days at RT and, if a long-term storage is required until DNA extraction, optimal conditions are obtained at − 20 °C.

Table 2.

Relationship between filter storage conditions, concentration and amount of urine DNA

Validation of primer pairs for the detection of FGFR3 mutations by MASO-PCR

The melting curves for G372C, R248C, S249C, and Y375C mutations by SG-PCR are represented in additional file (Figure S2). The temperature of melting (Tm) for each amplicon was 83.81 ± 0.01 °C for G372C, 86.80 ± 0.02 °C for R248C, 87.54 ± 0.01 °C for S249C and 84.85 ± 0.02 °C for Y375C. By applying, the Howley’s formula, we obtained equivalent Tm as compared with those given by the melting curves, with 83.87 °C for G372C (63.7% G-C, 72 bases), 86.85 °C for R248C (71.8% G-C, 78 bases), 87.57 °C for S249C (73.2% G-C, 82 bases) and 84.77 °C for Y375C (65.5% G-C, 79 bases), respectively. These two methods allowed us to validate the specificity of each primer pair.

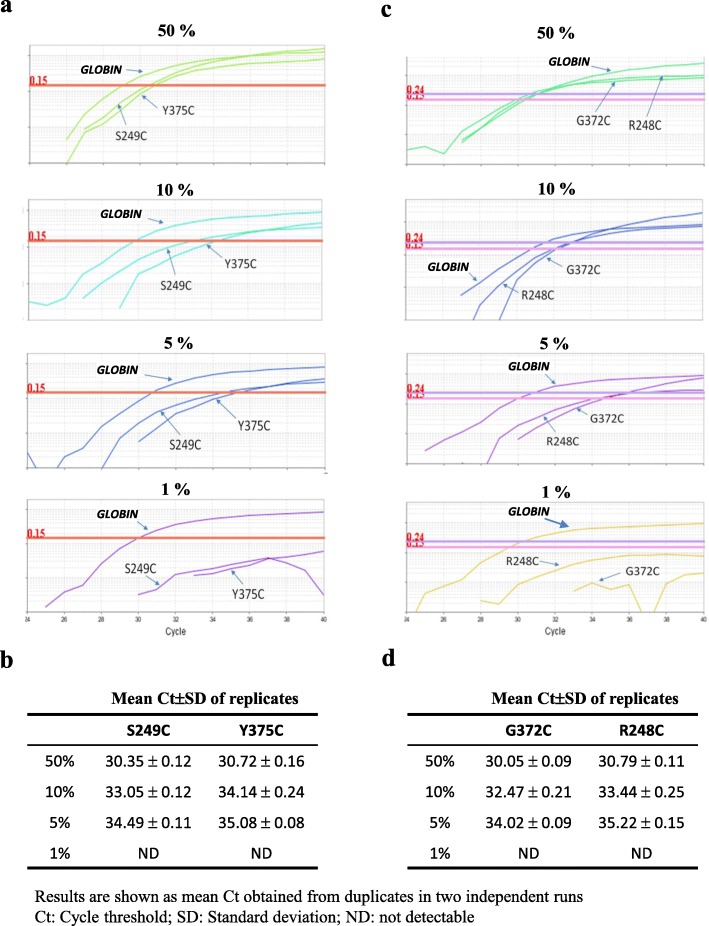

Sensitive detection of FGFR3 mutations by MASO-PCR

The limit of detection (LoD) of the Mutation assay with 5 ng was set at 5% of mutant sequences in a background of 95% normal DNA (Fig. 3a-b). This means that in the presence of a DNA sample containing less than 5% mutant (~ 15 copies), the MASO-PCR would be unable to detect the 4 mutations of the FGFR3 gene (G372C, R248C, S249C, and Y375C). The positive reactions (amplification curves) were carried out in duplicate onto two separate runs with a very good reproducibility. Cts were obtained with cut-off values (ΔRn) of 0.15 for GLOBIN, G372C, S249C, Y375C and 0.24 for R248C (Fig. 3c-d).

Fig. 3.

LoD for the Mutation assay. DNA from FGFR3 mutant plasmids was diluted into the wild-type DNA (standard human DNA). The proportion of mutant DNA was 50, 10, 5, and 1%, respectively. The representative amplification curves (a, c) and mean Ct values (b, d) are shown in the detection of the FGFR3 S249C/Y375C (a, b) and R248C/G372C (c, d) mutations by MASO-PCR

MASO-PCR accurately predicts recurrence of patients with NMIBC

By applying these threshold values, we clinically validated the MASO-PCR technology from 263 urine DNA samples (87 FGFR3 mutated and 176 FGFR3 wild-type). A complete concordance (100%) was observed between the MASO-PCR as compared with AS-PCR results. Sensitivity was defined as the ability of the MASO-PCR assay to detect FGFR3 mutations (+) and specificity as the ability of assay to identify the absence of FGFR3 mutations (−) in primary NMIBC tumor (diagnosis) as well as recurrence (follow-up). We successfully demonstrated the capacity of the MASO-PCR assay for detecting at least 15 copies of FGFR3 mutant alleles in 5 ng of wild type DNA with a sensitivity and specificity of 100% in urine of patients with low-, intermediate- and high-risk. All data are shown in Table 3.

Table 3.

Ultra-sensitive MASO-PCR method for surveillance of NMIBC patients

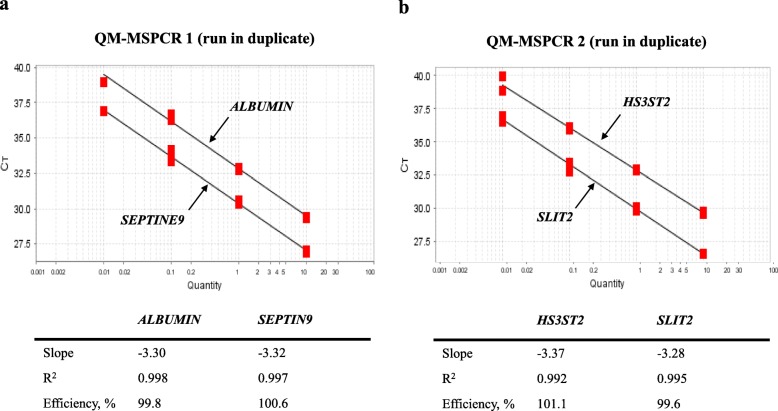

Sensitive quantification of DNA methylation by QM-MSPCR

QM-MSPCR was used to amplify ALBUMIN/SEPTIN9 (QM-MSPCR1) and HS3ST2/SLIT2 (QM-MSPCR2) duplexes with titration of bisulfite-converted positive control DNA (100% methylated) at various concentrations (10, 1, 0.1, 0.01 ng/well). At each dilution, the cycle threshold (Ct) was determined with bisulfite-converted positive control DNA (100% methylated). The Cts were analysed by using threshold value (ΔRn) of 0.10. Both calibration curves gave a slope of about − 3.32, which corresponds to PCR efficiency (E) close to 100%. More precisely, the slope values were − 3.31, − 3.34, − 3.29, and − 3.30 for ALBUMIN (E = 100.5%), SEPTIN9 (E = 99.2%), HS3ST2 (E = 101.4%). and SLIT2 (E = 100.8%), respectively. These results reflect very high amplification efficiency. We determined that the limit of quantification (LoQ) of each target gene could be detected with 10 pg of DNA. In addition, the high value of the correlation coefficient (greater than 0.99) indicates that an almost perfect linearity is obtained over the entire range. Data are represented in Fig. 4a for QM-MSPCR1 and Fig. 4b for QM-MSPCR2.

Fig. 4.

LoQ for the Methylation assay. The limit of quantification (LoQ) for the QM-MSPCR1 (a) and QM-MSPCR2 (b) was determined by carrying out a series of dilutions with bisulfite converted DNA quantities of 10, 1, 0.1 and 0.01 ng

High stability and reproducibility of “all-in-one” PCR master mixes

The all-in-one PCR master mixes allow using solutions containing all the necessary reagents for PCR amplification of DNA. In Table 3, Ct values of each target gene are indicated in function of storage time of the MASO-PCR and QM-MSPCR solutions. We have successfully verified the reproducibility and stability of each all-in-one solution after 12 months of storage at − 20 °C, showing intra-assay standard deviations lower than 0.3 Ct and coefficient of variations (CV) lower than 1% (Table 4).

Table 4.

High performance of PCR Master mix all-in-one

Design of Urodiag® PCR kit

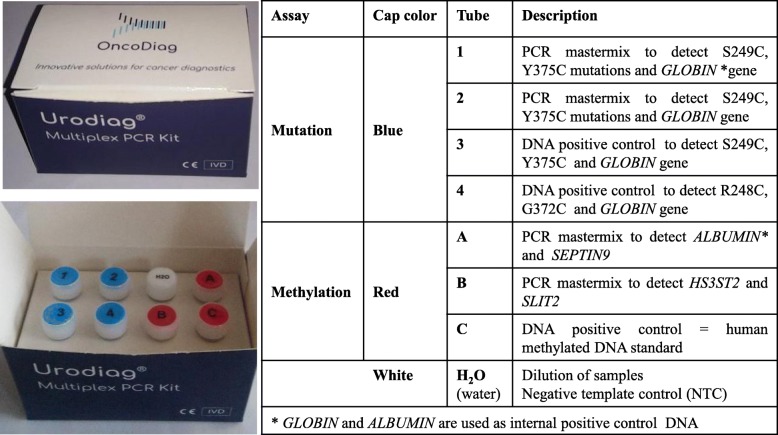

The Urodiag® PCR Kit is an in vitro diagnostic test intended for the qualitative detection of FGFR3 somatic mutations (G372C, R248C, S249C, Y375C) and the quantification of three DNA methylation markers (HS3ST2, SEPTIN9, SLIT2) by stable multiplex PCR in urine of NMIBC patients. The PCR kit is composed of 8 tubes (4 for the Mutation assay, 3 for the Methylation assay and 1 tube with sterile water) (Table 5). Each tube contains all the components (PCR mastermix, primers and probes) necessary to carry out Mutation and Methylation assays.

Table 5.

Components of the Urodiag® PCR Kit

Discussion

Due to the high recurrence rate of bladder cancer, NMIBC tumors require a active surveillance: periodic cystoscopy with urine cytology remains the reference examination, making it the most expensive of all cancers [19]. Cystoscopy is an uncomfortable invasive exam and cytology presents a good sensitivity for detecting high-risk NMIBC but a very poor sensitivity for low-risk [20]. Urine is an ideal biological source for recovering bladder cells and mainly exfoliated tumor cells [21]. Previous work has shown that filtration of urine samples, using a syringe filter with a suitable pore size, increases the diagnostic accuracy of BCa while removing contaminant (e.g. blood cells) [21, 22]. In order to optimize the accuracy of our test, the filtration of urine samples was carried out by a disposable syringe filter device. Currently, urine tests are available for primary diagnosis and follow-up of patients with NMIBC such as ADXBLADDER test ($52 per test), Bladder Epicheck test (not yet marketed), bladder tumor associated antigen (BTA, $40 per test), ImmunoCyt ($200 per test), nuclear matrix protein 22 (NMP22, $25 per test), UroVysion ($800 per test), Xpert BC Monitor ($165 per test) [23–30]. Due to their lack of specificity or sensitivity, these tests are not widely used in routine laboratory. Prior studies have reported that some mutations of FGFR3 gene are mainly found in NMIBC (~ 60%) versus MIBC (~ 20%) [31, 32]. In NMIBC, the four most relevant mutations are found in exons 7 and 10 with S249C and R248C in exon 7, and Y375C and G372C in exon 10 [33, 34]. Zuiverloon and colleagues described that these four mutations can be detected in urine and used to develop a non-invasive test for the diagnosis and monitoring of patients with low-risk NMIBC [34]. Furthermore, it has been shown that high-risk tumors have generally more hypermethylated genes than low-risk tumors [35]. Consistently with all these observations, we were able to propose a panel of genetic (FGFR3 mutations) and epigenetic (hypermethylation of the HS3ST2, SEPTIN9 and SLIT2) urinary markers which, due to their strong complementarity, given a very high clinical accuracy for the monitoring in NMIBC Patients with a low, intermediate and high risk of recurrence [18]. In comparison with the tests above mentioned, our combined test gives the best clinical performances: sensitivity/specificity/NPV respectively equal to or greater than 95%/76%/99% [18]. During the present study, we designed the Urodiag® kit so that it contains all the components of the PCR for its use in clinical routine. To increase the diagnostic accuracy of BCa, we showed the feasibility of enriching the exfoliated bladder cells with a unique syringe filter to replace traditional centrifugation. We showed that this device was able to isolate DNA with reproducibility, high purity and sufficient quantity for subsequent MASO-PCR and QM-MSPCR amplification. We have developed and clinically validated the MASO-PCR to detect four mutations of FGFR3 gene (G372C, R248C, S249C and Y375C) with outstanding accuracy with 100% sensitivity/specificity, equivalent to the results that can be obtained using capillary electrophoresis for DNA analysis (AS-PCR). Consequently, the mutation and methylation assays can be carried out on the same real time quantitative PCR machine, facilitating the implementation of the Urodiag® Kit in laboratories. To simplify the PCR workflow, we prepared the all in one master mixes, solutions containing all the necessary reagents for MASO-PCR and QM-MSPCR PCR, with two main advantages: reduction of pipetting errors and time saving.

Conclusions

We showed that the Mutation assay (MASO-PCR) and Methylation assay (QM-MSPCR) could be simultaneously performed on the same real time quantitative PCR machine, facilitating the implementation of the Urodiag® PCR Kit in laboratories. It has been designed as a urine-based laboratory test that provides a simple, fast, reliable and low-cost (~ $100 per test) method for diagnosis and individualized surveillance for patients with low-, intermediate- and high-risk NMIBC. Leading to a significantly reduction of repetitive cystoscopies, it presents major benefits for the quality of life of the patients during their follow-up, the work of the urologists and in terms of cost reduction for health care systems.

Supplementary information

Additional file 1: Figure S1. Construction of mutated FGFR3 plasmids

Additional file 2: Figure S2. Melting curve PCR analysis for the FGFR3 mutations

Acknowledgements

I would like to warmly thank the technicians, as healthy donors, of the pathology department of François Quesnay Hospital (Mantes La Jolie, France) for providing their urine samples.

Abbreviations

- BCa

Bladder cancer

- Ct

Cycle threshold

- CV

Coefficient of variation

- MASO-PCR

Mutated Allele Specific Oligonucleotide-PCR

- LoD

Limit of detection

- LoQ

Limit of quantification

- NMIBC

Non-muscle invasive bladder cancer

- NPV

Negative predictive value

- PBS

Phosphate buffered saline

- QM-MSPCR

Quantitative Multiplex-Methylation Specific PCR

- RT

Room temperature

Authors’ contributions

JPR performed the study design and the development of methodology. JPR collected data. CH and JPR were responsible for data interpretation and manuscript preparation. CH and JPR were responsible for the revision of the manuscript. CH and JPR reviewed, read and approved the final version of the manuscript.

Funding

This work was supported by a grant from the Agence de développement pour la Normandie (ADN) (Impulsion Export/2019–2020/19P00800).

The funding body played no role in the design of the study and collection, analysis, and interpretation of data and in writing the manuscript.

Availability of data and materials

The datasets used and/or analysed during the current study are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

Ethics approval and consent to participate

Free and written consent was obtained from all individuals participant of this study. Approval was obtained by the Paris Bichat-Claude Bernard hospital ethics committee (approval number: 2004/15).

Consent for publication

Not applicable.

Competing interests

JPR and CH are founding members of OncoDiag SAS. JPR is the R&D head and CH is the CEO.

Footnotes

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Contributor Information

Jean-Pierre Roperch, Email: roperch@oncodiag.fr.

Claude Hennion, Email: hennion@oncodiag.fr.

Supplementary information

Supplementary information accompanies this paper at 10.1186/s12881-020-01050-w.

References

- 1.Bray F, Ferlay J, Soerjomataram I, Siegel RL, Torre LA, Jemal A. Global cancer statistics 2018: GLOBOCAN estimates of incidence and mortality worldwide for 36 cancers in 185 countries. CA Cancer J Clin. 2018;68(6):394–424. doi: 10.3322/caac.21492. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Babjuk M, Burger M, Compérat EM, Gontero P, Mostafid AH, et al. European Association of Urology guidelines on non-muscle-invasive bladder Cancer (ta, T1 and carcinoma in situ)-2019 update. Eur Urol. 2019;76:639–657. doi: 10.1016/j.eururo.2019.08.016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Svatek RS, Hollenbek BK, Holmäng S, Lee R, Kim SP, Stenzl A, Lotan Y. The health economics of bladder cancer: costs and considerations of caring for this desease. Eur Urol. 2014;66:253–262. doi: 10.1016/j.eururo.2014.01.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Yafi FA, Brimo F, Steinberg J, Aprikian AG, Tanguay S, Kassouf W. Prospective analysis of sensitivity and specificity of urinary cytology and other urinary biomarkers for bladder cancer. Urol Oncol. 2015;33:66. doi: 10.1016/j.urolonc.2014.06.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Sadikovic B. K Al-Romaih. JA squire, Zielenska M. cause and consequences of genetic and epigenetic alterations in human Cancer. Curr Genomics. 2008;9(6):394–408. doi: 10.2174/138920208785699580. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Van Rhijn BW, van Tilborg AA, Lurkin I, et al. Novel fibroblast growth factor receptor 3 (FGFR3) mutations in bladder cancer previously identified in non-lethal skeletal disorders. Eur J Hum Genet. 2002;10:819–824. doi: 10.1038/sj.ejhg.5200883. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Billerey C, Chopin D, Aubriot-Lorton MH, Ricol D, et al. Frequent FGFR3 mutations in papillary non-invasive bladder (pTa) tumors. Am J Pathol. 2001;158:1955–1959. doi: 10.1016/S0002-9440(10)64665-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Van Rhijn BW, Lurkin I, Radvanyi F, Kirkels WJ, et al. The fibroblast growth factor receptor 3 (FGFR3) is a strong indicator of superficial bladder cancer with low recurrence rate. Cancer Res. 2001;61:1265–1268. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Knowles MA. Role of FGFR3 in urothelial cell carcinoma: biomarker and potential therapeutic target. World J Urol. 2007;25(6):581–593. doi: 10.1007/s00345-007-0213-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Tahlita CM. Zuiverloon, Madelon N.M. van der Aa, Theo H. van der Kwast, et al. fibroblast growth factor receptor 3 mutation analysis on voided urine for surveillance of patients with low-grade non-muscle–invasive bladder Cancer. Clin Cancer Res. 2010;16:3011–3018. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-09-3013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Couffignal C, Desgrandchamps F, Mongiat-Artus P, Ravery V, Ouzaid I, Roupret M, et al. A prospective multicentre study to establish the diagnostic and prognostic performance of noninvasive FGFR3 mutation in bladder cancer surveillance. Urology. 2015;86(6):1185–1191. doi: 10.1016/j.urology.2015.07.036. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Esteller M. Molecular origins of cancer: epigenetics in cancer. NEJM. 2008;358:1148–1159. doi: 10.1056/NEJMra072067. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Sproul D, Kitchen RR, Nestor CE. Tissue of origin determines cancer-associated CpG island promoter hypermethylation patterns. Genome Biol. 2012;13:R84. doi: 10.1186/gb-2012-13-10-r84. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Reinert T, Modin C, Castano FM, Lamy P, Wojdacz TK, Hansen LL, et al. Comprehensive genome methylation analysis in bladder cancer: identification and validation of novel methylated genes and application of these as urinary tumor markers. Clin Cancer Res. 2011;17:5582–5592. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-10-2659. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Kandimalla R, van Tilborg AA, Zwarthoff EC. DNA methylation-based biomarkers in bladder cancer. Nat Rev Urol. 2013;10(6):327–335. doi: 10.1038/nrurol.2013.89. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Zuiverloon TCM, Beukers W, Van Der Keur KA, Munoz JR, Bangma CH, Lingsma HF, et al. A methylation assay for the detection of non-muscle-invasive bladder cancer (NMIBC) recurrences in voided urine. BJU Int. 2012;109:941–948. doi: 10.1111/j.1464-410X.2011.10428.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Serizawa RR, Ralfkiaer U, Steven K, Lam GW, Schmiedel S, Schuz J, et al. Integrated genetic and epigenetic analysis of bladder cancer reveals an additive diagnostic value of FGFR3 mutations and hypermethylation events. Int J Cancer. 2011;129:78–87. doi: 10.1002/ijc.25651. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Roperch JP, Grandhamp B, Desgranchamps F, Mongiat-Artus P, Ravery I, et al. Promoter hypermethylation of HS3ST2, SEPTIN9 and SLIT2 combined with FGFR3 mutations as a sensitive/specific urinary assay for diagnosis and surveillance in patients with low or high-risk non-muscle-invasive bladder cancer. BMC Cancer. 2016;16:704. doi: 10.1186/s12885-016-2748-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Botteman MF, Pashos CL, Redaelli A, Laskin B, Hauser R. The health economics of bladder cancer: a comprehensive review of the published literature. Pharmacoeconomic. 2003;21:1315–1330. doi: 10.1007/BF03262330. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Yafia FA, Brimo F, Auger M, Aprikian A, Tanguay S, Kassouf W. Is the performance of urinary cytology as high as reported historically? A comprehensive analysis in the decision and surveillance of bladder cancer. Urol Oncol. 2013;27:S1078–S1439. doi: 10.1016/j.urolonc.2012.09.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Andersson E, Steven K, Guldberg P. Size-based enrichment of exfoliated tumor cells in urine increases the sensitivity for DNA-based detection of bladder Cancer. PLoS One. 2014;9:e94023. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0094023. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Keshtkar A. Keshtkar as and Lawford P. cellular morphological parameters of the human urinary bladder (malignant and normal) Int J Exp Pathol. 2007;88(3):185–190. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2613.2006.00520.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Mbeutcha A, Lucca I, Mathieu R, Lotan Y, Shariat SF. Current status of urinary biomarkers for detection and surveillance of bladder Cancer. Urol Clin North Am. 2016;43(1):47–62. doi: 10.1016/j.ucl.2015.08.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Fernandez CA, Millholland JM, Zwarthoff EC, Feldman AS, Karnes RJ, Shuber AP. A noninvasive multi-analyte diagnostic assay: combining protein and DNA markers to stratify bladder cancer patients. Res Rep Urol. 2012;4:17–26. doi: 10.2147/RRU.S28959. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Lotan Y, O’Sullivan P, Raman JD, Shariat SF, Kavalieris L, Frampton C, et al. Clinical comparison of noninvasive urine tests for ruling out recurrent urothelial carcinoma. Urol Oncol. 2017;35(8):531. doi: 10.1016/j.urolonc.2017.03.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Kavalieris L, O’Sullivan P, Frampton C, Guilford P, Darling D, Jacobson E, et al. Performance characteristics of a multigene urine biomarker test for monitoring for recurrent urothelial carcinoma in a multicenter study. J Urol. 2017;197(6):1419–1426. doi: 10.1016/j.juro.2016.12.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Dudderidge T, Nabi G, Mom J, Umez-Eronini N, Hrouda D, Cresswell J, McCracken S. A novel non-invasive aid for bladder cancer diagnosis: a prospective, multi-Centre study to evaluate the ADXBLADDER test. Eur Urol Suppl. 2018;17(2):e1424. doi: 10.1016/S1569-9056(18)31835-9. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 28.van Kessel KE, Beukers W, Lurkin I. Ziel-van der made a, van der Keur KA, Boormans JL, et al. validation of a DNA methylation-mutation urine assay to select patients with hematuria for cystoscopy. J Urol. 2017;197(3 Pt 1):590–595. doi: 10.1016/j.juro.2016.09.118. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Hurle R, Casale P, Saita A, Colombo P, Elefante GM, Lughezzani G, Fasulo V, Paciotti M, et al. Clinical performance of Xpert bladder Cancer (BC) monitor, a m-RNA-based urine test, in active surveillance (AS) patients with recurrent non-muscle-invasive bladder cancer (NMIBC): results from the bladder Cancer Italian active Sureveillance (BIAS) project. World J Urol. 2019. 10.1007/s00345-019-03002-3. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 30.D’Andrea D, Soria F, Zehetmayer S, Gust KM, Korn S, Witjes JA, Shariat SF. Diagnostic accuracy, clinical utility and influence on decision-making of a DNA methylation urine biomarker test in the surveillance of non-muscle-invasive bladder cancer. BJU. 2019;123(6):959–967. doi: 10.1111/bju.14673. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Rieger-Christ KM, Mourtzinos A, Lee PJ, Zagha RM, Cain J, Silverman M, et al. Identification of fibroblast growth factor receptor 3 mutations in urine sediment DNA samples complements cytology in bladder tumor detection. Cancer. 2003;98:737–744. doi: 10.1002/cncr.11536. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.van Oers JM, Lurkin I, van Exsel AJ, Nijsen Y, van Rhijn BW, van der Aa MN, Zwarthoff EC. A simple and fast method for the simultaneous detection of nine fibroblast growth factor receptor 3 mutations in bladder cancer and voided urine. Clin Cancer Res. 2005;11(21):7743–7748. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-05-1045. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Lamy A, Gobet F, Laurent M, Blanchard F, et al. Molecular profiling of bladder tumors based on the detection of FGFR3 and TP53 mutations. J Urol. 2006;176:2686–2689. doi: 10.1016/j.juro.2006.07.132. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Zuiverloon TCM. Van an der Aa MNM, van der Kwast, et al. fibroblast growth factor receptor 3 mutation analysis on voided urine for surveillance of patients with low-grade non-muscle-invasive bladder cancer. Clin Cancer Res. 2010;16(11):3011–3018. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-09-3013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Brait M, Begum S, Carvalho AL, Dasgupta S, Vettore AL, et al. Aberrant promoter methylation of multiple genes during pathogenesis of bladder cancer. CEBP. 2008;17(10):2786–2794. doi: 10.1158/1055-9965.EPI-08-0192. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Additional file 1: Figure S1. Construction of mutated FGFR3 plasmids

Additional file 2: Figure S2. Melting curve PCR analysis for the FGFR3 mutations

Data Availability Statement

The datasets used and/or analysed during the current study are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.