Abstract

G protein–coupled receptors (GPCRs) are important modulators of glucose-stimulated insulin secretion, essential for maintaining energy homeostasis. Here we investigated the role of Gβ5–R7, a protein complex consisting of the atypical G protein β subunit Gβ5 and a regulator of G protein signaling of the R7 family. Using the mouse insulinoma MIN6 cell line and pancreatic islets, we investigated the effects of G protein subunit β 5 (Gnb5) knockout on insulin secretion. Consistent with previous work, Gnb5 knockout diminished insulin secretion evoked by the muscarinic cholinergic agonist Oxo-M. We found that the Gnb5 knockout also attenuated the activity of other GPCR agonists, including ADP, arginine vasopressin, glucagon-like peptide 1, and forskolin, and, surprisingly, the response to high glucose. Experiments with MIN6 cells cultured at different densities provided evidence that Gnb5 knockout eliminated the stimulatory effect of cell adhesion on Oxo-M–stimulated glucose–stimulated insulin secretion; this effect likely involved the adhesion GPCR GPR56. Gnb5 knockout did not influence cortical actin depolymerization but affected protein kinase C activity and the 14-3-3ϵ substrate. Importantly, Gnb5−/− islets or MIN6 cells had normal total insulin content and released normal insulin amounts in response to K+-evoked membrane depolarization. These results indicate that Gβ5–R7 plays a role in the insulin secretory pathway downstream of signaling via all GPCRs and glucose. We propose that the Gβ5–R7 complex regulates a phosphorylation event participating in the vesicular trafficking pathway downstream of G protein signaling and actin depolymerization but upstream of insulin granule release.

Keywords: pancreas, signal transduction, regulator of G protein signaling (RGS), actin, G protein–coupled receptor (GPCR), cell adhesion, insulin release

Introduction

Maintaining the appropriate concentration of blood glucose is one of the most crucial homeostatic functions of the body. Glucose levels rise after ingestion of food or when activation of the sympathetic nervous system stimulates release of glucose from its storage in the liver and skeletal muscle. Glucose levels return to normal when the demand for energy subsides and tissues metabolize or store excess glucose. Disruption of this delicate balance results in development of diseases such as diabetes. Glucose uptake is stimulated by insulin, the hormone synthesized and released by a single cell type in the body: β cells located in the pancreatic islets.

The basic mechanism of glucose-stimulated insulin secretion (GSIS)3 was proposed more than two decades ago. Upon a rise in blood glucose, its enhanced transport into β cells boosts production of ATP, causing closure of ATP-sensitive K+ channels and depolarization of the plasma membrane. Depolarization promotes opening of L-type voltage-gated Ca2+ channels and influx of extracellular Ca2+ into the cytosol, triggering exocytosis of insulin-containing vesicles. This model is therefore referred to as the triggering pathway, as glucose transport into the cell triggers this increase in cytosolic Ca2+ (1, 2). A more complete model of insulin secretion incorporates the biphasic nature of secretion, cytoskeletal remodeling, and transport and docking of insulin granules on the plasma membrane, all of which are regulated by signaling mechanisms (3–5).

Insulin release is suppressed in the absence of high glucose, as excess uptake leads to hypoglycemia. However, at permissive glucose levels, β cells are responsive to a multitude of hormones, neurotransmitters, and other extracellular stimuli that enhance or attenuate GSIS. These signals operate via the metabolic amplification pathway, which is thought to operate during the second phase of GSIS, when insulin secretion is limited to fine-tuned pulses released as necessary (1, 2). Many GSIS-modulating inputs are mediated by G protein–coupled receptors (GPCRs). For example, receptors of the glucagon-like peptide GLP-1 promote GSIS via activation of Gs and the corresponding rise in cAMP (6, 7). Receptors of vasopressin and adenosine promote GSIS via activation of Gq (8–10). Cholinergic stimulation, which in β cells is integrated via the Gq-coupled muscarinic cholinergic receptor M3 (M3R), also has a strong insulinotropic effect (11, 12).

G protein signaling involves a number of regulatory proteins, including arrestins and protein kinases, that regulate the functions of GPCRs and downstream events. Regulator of G protein signaling (RGS) proteins belong to a diverse family characterized by the presence of the ∼100-amino-acid RGS domain, which interacts with GTP-bound Gα subunits and accelerates their GTPase activity (13, 14). Although GTPase-activating protein activity is a hallmark function of RGS proteins, many of them have additional domains that perform other functions. RGS proteins that belong to the R7 family (RGS6, RGS7, RGS9, and RGS11) form obligate heterodimers with Gβ5, an atypical Gβ subunit (15). The R7 RGS subunit consists of four domains: RGS, GGL (Gγ-like), DEP helical extension (DHEX), and Dishevellled, EGL-10, plekstrin (DEP) (16). Gβ5 binds to the GGL domain, and this interaction is obligatory; they have never been found separately in vivo, and the Gβ5 and R7 subunits quickly degrade when expressed separately in vitro (17). Therefore, knockout of Gnb5 causes ablation of the entire R7 family (18). In addition to Gα, Gβ5–R7 dimers interact with anchoring proteins, ion channels, GPCRs, and other molecules (19, 20). According to a recent report, Gβ5–RGS7 can directly interact with G12/13, influencing the activity of the Rho pathway and cytoskeletal rearrangement in neuronal cells (21).

Gβ5–R7 complexes are highly expressed in the nervous system and were originally referred to as neuronal proteins. Subsequent studies showed their presence at a lower level in other tissues and cell types (22–26). In contrast to investigations of the nervous system, the role of RGS proteins in the pancreas has been relatively unexplored. It has been shown that pancreatic expression of RGS16 and RGS8 is low in normal adults and high in those with diabetes (27). Another study investigated RGS4 and demonstrated that it acts as a negative regulator of insulin secretion stimulated by M3R and other receptors (28). Surprisingly, our earlier studies showed that Gβ5–R7 acted as a positive regulator of M3R-stimulated insulin secretion. Gnb5 knockout in mice dramatically reduces serum insulin levels, and these findings are consistent with CRISPR/Cas9-mediated Gnb5 knockout and overexpression in MIN6 cells (24, 29). In this paper, we extended the studies of Gβ5–R7 in β cells, and our results indicate that Gβ5–R7 enhances not only the function of M3R but also that of other stimuli, including the insulinotropic activity of high glucose.

Results

Our previous work demonstrated that Gnb5 knockout causes a dramatic reduction in M3R-stimulated GSIS in MIN6 cells (24), and in this study, we further investigated the cellular and molecular mechanisms affected by knockout.

Gnb5 knockout does not impair actin depolymerization

GSIS is a biphasic process characterized by a rapid first phase and a slower, continuous second phase. During the first phase, β cells release insulin granules that are predocked on the plasma membrane. In the second phase, insulin-containing vesicles are recruited from intracellular storage pools. A key step in the second phase is local depolymerization of cortical F-actin filaments that block the passage of vesicles to the plasma membrane until arrival of the appropriate signal(s) (4, 30). One of the regulators of cortical F-actin dynamics is Rho-associated protein kinase (ROCK), and the Gβ5–RGS7 complex is implicated in regulation of the actin cytoskeleton via G13 and RhoGEF proteins in neurons (21, 32). Therefore, we hypothesized that knockout of Gβ5 may disrupt actin remodeling in MIN6 cells. If depolymerization is impaired in Gnb5−/− cells, we could expect that application of latrunculin B, an inhibitor of actin polymerization, would rescue insulin secretion.

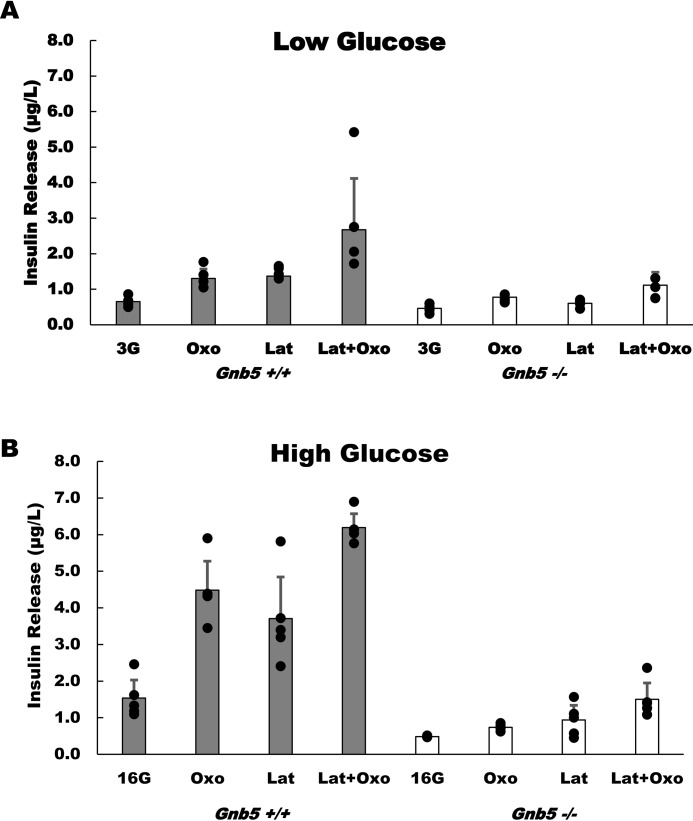

The effect of latrunculin in 3 mm glucose was minimal (Fig. 1A), which was predictable, as insulin secretion is repressed in low glucose. Nevertheless, in Gnb5+/+ cells, stimulation with the muscarinic agonist Oxo-M resulted in a 2-fold increase (from 0.65 ± 0.12 μg/liter to 1.3 ± 0.26 μg/liter, n = 5, p = 0.00198) in insulin secretion. Application of latrunculin resulted in an almost identical stimulation of insulin release. In the presence of high (16.7 mm) glucose, latrunculin also stimulated insulin release ∼2-fold (Fig. 1B). However, the overall amount of latrunculin-stimulated insulin release in high glucose was three times larger than in low glucose (3.71 ± 1.14 μg/liter in 16.7 mm versus 1.37 ± 0.27 μg/liter in 3 mm, n = 5, p = 0.004) (Fig. 1B). Consistent with previous studies, Oxo-M stimulated GSIS 4-fold in the Gnb5+/+ cells, and this response was slightly potentiated by latrunculin.

Figure 1.

Gnb5 knockout inhibits stimulated insulin secretion in MIN6 cells. Gnb5+/+ (gray columns) or Gnb5−/− (open columns) MIN6 cells were stimulated with 10 μm latrunculin B (Lat), 100 μm Oxo-M (Oxo), or both in the presence of 3 mm (3G, A) or 16.7 mm glucose (16G, B). The supernatants were collected for insulin ELISA analysis (y axis). The data points show raw data from five independent cell culture experiments; each black dot is the average of ELISA readings from triplicate wells. Error bars show mean value with standard deviations. To avoid clutter, statistical analysis of the high glucose response is presented in Fig. 2.

Gnb5 knockout markedly suppressed insulin secretion (Fig. 1), consistent with our finding that Gβ5–R7 is a positive regulator of GSIS (24). In low glucose, Oxo-M caused a statistically significant increase in secretion (from 0.46 ± 0.01 μg/liter to 0.77 ± 0.33 μg/liter, n = 5, p = 0.005), but this amount was two times lower than the amount secreted in Gnb5+/+ cells. In high glucose, Gnb5−/− cells secrete about six times less insulin with Oxo-M stimulation than control cells. Latrunculin did not have an effect on secretion in low glucose, but in high glucose it caused slightly stronger stimulation than Oxo-M (0.77 ± 0.16 μg/liter versus 0.93 ± 0.08 μg/liter, n = 5, p = 0.34). Application of latrunculin together with Oxo-M boosted secretion to 1.5 ± 0.44 μg/liter. However, this amount was still underwhelming compared with Gnb5+/+ cells (Fig. 1B).

Together, these results show that latrunculin facilitates insulin secretion regardless of the presence of Gβ5–R7. Oxo-M could not stimulate Gnb5−/− cells to secrete insulin to a degree comparable with that of Gnb5+/+, even when latrunculin caused disassembly of the cortical actin barrier. Accordingly, when we investigated the effects of ROCK and Rho inhibitors on Oxo-M–stimulated insulin secretion (data not shown), we did not find any evidence of a link between Gβ5–RGS7 and regulation of insulin secretion by the Rho/ROCK pathway. We conclude from these experiments that Gβ5–R7 does not play a role in the actin depolymerization step of insulin exocytosis. Our results also revealed that, with or without latrunculin, the effect of high glucose is diminished in Gnb5−/− cells.

Gnb5 knockout reduces GSIS in MIN6 cells and primary pancreatic islets

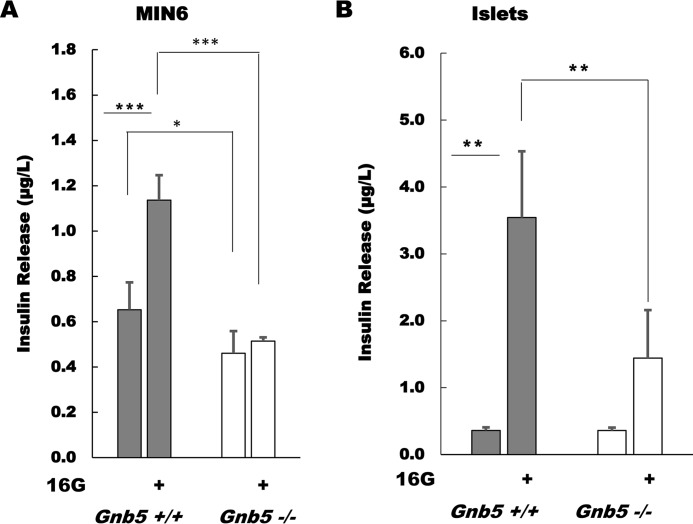

MIN6 cells are known to have relatively low GSIS compared with isolated pancreatic islets. Therefore, in our earlier studies of the role of Gβ5–R7 in MIN6 cells, we focused on muscarinic stimulation of GSIS via M3R, which has a broad dynamic range (24). However, amplification of insulin responses by latrunculin (Fig. 1) made the effect of Gnb5 knockout on GSIS obvious (Fig. 2A). In Gnb5+/+ MIN6 cells, the increase in glucose concentration from 3.3 mm to 16.7 mm induced an almost 2-fold rise in insulin secretion (from 0.65 ± 0.12 μg/liter to 1.13 ± 0.11 μg/liter, n = 5, p = 0.0004). This increase is modest compared with the responses to Oxo-M (Fig. 1) but is statistically significant. In contrast, high glucose did not significantly stimulate Gnb5−/− cells (from 0.46 ± 0.1 to 0.48 ± 0.16 μg/liter, n = 5, p = 0.66).

Figure 2.

Gβ5–R7 promotes GSIS in MIN6 cells and pancreatic islets. MIN6 cells or pancreatic islets isolated from Gnb5+/+ and Gnb5−/− mice were incubated with 3 mm glucose before stimulation with 16.7 mm glucose. Supernatant was subjected to insulin ELISA. A, data on the Gnb5+/+ and Gnb5−/− MIN6 cells from Fig. 1 were analyzed with single-factor analysis of variance with five independent cell cultures. B, islets were prepared and treated as described under “Experimental procedures.” Secretion of insulin was measured by ELISA using islets from three independent preparations. Bar graphs show mean ± S.D. *, p < 0.05; **, p < 0.01; ***, p < 0.001. Gray columns, Gnb5+/+; white columns, Gnb5−/−.

Importantly, we observed a similar effect of Gnb5 knockout on GSIS using pancreatic islets isolated from WT and Gnb5 knockout mice (Fig. 2B). In control islets, application of 16.7 mm glucose increased insulin secretion almost 10-fold (from 0.36 ± 0.05 to 3.54 ± 1 μg/liter, n = 3, p = 0.003). In Gnb5−/− islets, this stimulation was only 4-fold (from 0.36 ± 0.04 to 1.44 ± 0.72 μg/liter, n = 5, p = 0.07) (Fig. 2B).

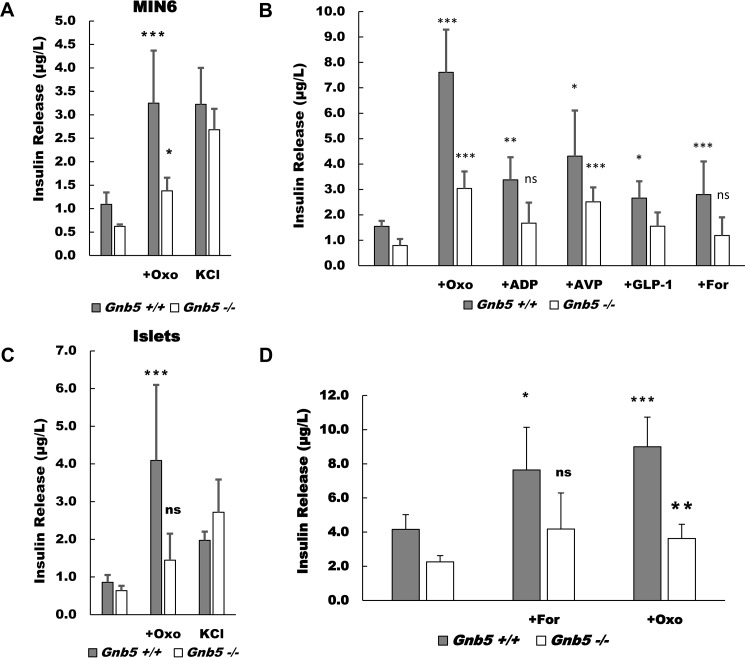

Membrane depolarization, total insulin content, and stimulation of GPCRs in MIN6 cells and islets

We tested whether Gnb5 knockout affected the responses to stimuli other than glucose and the M3R agonist Oxo-M (Fig. 3). Treatment of Gnb5+/+ and Gnb5−/− MIN6 cells with 50 mm KCl evoked a similar response. Furthermore, there was no significant difference in total insulin content, which was determined after complete lysis of Gnb5−/− and Gnb5+/+ MIN6 cells. These results indicate that insulin production and cellular response to depolarization are not affected by Gnb5 knockout. Similarly, there was no significant difference in KCl-evoked insulin release in pancreatic islets isolated from Gnb5+/+ and Gnb5−/− mice (Fig. 3C). This is consistent with our previous data, which showed that total insulin content in control and knockout islets were indistinguishable (29).

Figure 3.

Gβ5–R7 promotes insulin release evoked by several secretagogues in MIN6 cells and primary islets. A, Gnb5+/+ and Gnb5−/− MIN6 cells were stimulated with 100 μm Oxo-M (Oxo) in the presence of 16.7 mm glucose or 50 mm KCl. B. Gnb5+/+ and Gnb5−/− MIN6 cells were stimulated with 100 μm Oxo-M, 100 μm ADP, 0.1 μm AVP, 0.1 μm GLP-1, or 10 μm forskolin (For) in the presence of 16.7 mm glucose. C, islets isolated from Gnb5+/+ and Gnb5−/− mice were stimulated with 100 μm Oxo-M in the presence of 16.7 mm glucose or 50 mm KCl. D, islets were treated with 100 μm Oxo-M or 10 μm forskolin in the presence of 16.7 mm glucose. Shown are raw ELISA readings, mean ± S.D. for at least five independent experiments. In C and D, n = 3. Statistical analysis is reported as the difference between 16G and each stimulant within genotypes. *, p < 0.05; **, p < 0.01; ***, p < 0.001; ns, not significant.

Next we tested how Gnb5−/− MIN6 cells respond to stimulation of GPCRs other than M3R (Fig. 3B). Our data show that ADP and AVP, which are known to promote insulinotropic activity via Gq-coupled adenosine and vasopressin receptors, respectively, stimulated GSIS in Gnb5+/+ MIN6 cells. ADP in the presence of 16.7 mm glucose raised the insulin response from 1.82 μg/liter to 3.37 μg/liter and AVP up to 4.31 μg/liter. In Gnb5−/− cells, ADP and AVP responses were essentially undetectable.

In Gnb5+/+ cells, activation of the Gs-coupled receptor of GLP-1 increased insulin release about 2-fold compared with high glucose alone. Direct activation of adenylate cyclase by forskolin had a similar effect. The relatively modest insulinotropic activity of the cAMP pathway is consistent with a report that GLP-1 receptor signaling is reduced in β cells exposed to chronic high glucose environments, as is the case with cultured MIN6 cells (33). In Gnb5−/− cells, GLP-1 evoked a statistically significant response (1.55 ± 0.55 μg/liter versus 0.79 ± 0.27 μg/liter, n = 5, p = 0.048); this increase was reduced compared with that of Gnb5+/+ cells (1.55 ± 0.55 μg/liter versus 2.66 ± 0.66 μg/liter, n = 5, p = 0.016). Similar results were obtained with forskolin; however, the forskolin-stimulated increase in insulin secretion from Gnb5−/− cells was not statistically significant (1.18 ± 0.37 μg/liter versus 0.79 ± 0.27 μg/liter, n = 6, p = 0.118), and the amount of insulin released in the presence of forskolin was less than half of the response of the Gnb5+/+ cells (1.18 ± 0.36 μg/liter versus 2.8 ± 0.48 μg/liter, n = 6, p = 1.38 × 10−5).

In primary pancreatic islets from Gnb5+/+ mice (Fig. 3D), Oxo-M stimulation resulted in a 2-fold increase in insulin release (4.16 ± 0.87 versus 8.99 ± 1.73 μg/liter, n = 3, p = 0.00023) in high glucose, consistent with our previous report (29). Application of forskolin almost doubled the insulin response in these islets (4.16 ± 0.87 versus 7.64 ± 2.5, n = 3, p = 0.01); in fact, there was no statistically significant difference between the responses evoked by Oxo-M and forskolin (p = 0.34) (Fig. 3B). Forskolin also potentiated insulin secretion by Gnb5−/− islets in the presence of high glucose (2.3 ± 0.37 versus 4.2 ± 2.1, n = 3, p = 0.07), but the level of forskolin-evoked insulin release was 1.76 times lower than in control islets. These results show that Gnb5 knockout (Fig. 2) diminishes the insulinotropic activity of not only M3R but also that of a broader range of insulinotropic stimuli.

Cell adhesion signaling

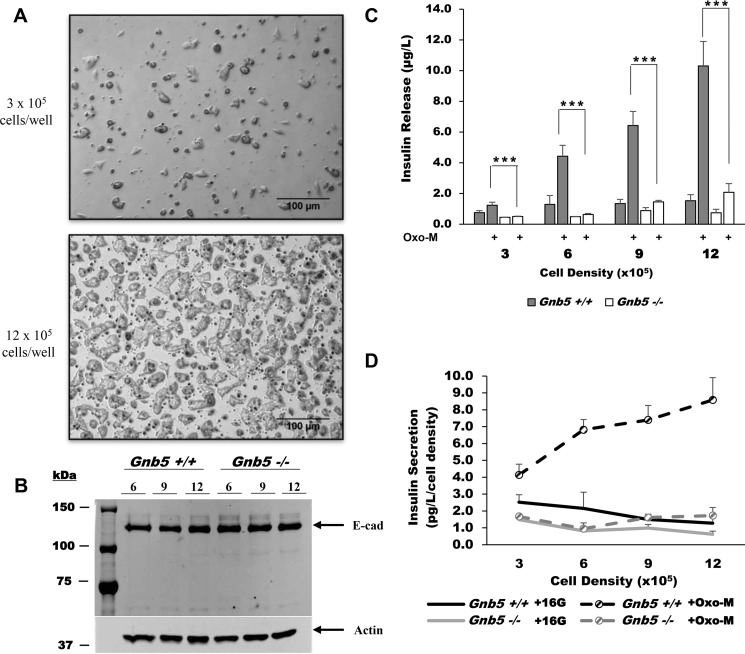

In the course of our studies, we noticed that M3R-mediated stimulation of insulin secretion was more robust when MIN6 cells were plated at higher densities. MIN6 cells are known to form aggregates that show improved GSIS compared with less confluent cultures (34). Because total insulin content per cell is similar in large and small aggregates (35), it is thought that increased cell-to-cell communication facilitates secretion rather than production of insulin.

We investigated whether loss of Gβ5–R7 affects this cell adhesion–related phenomenon. We plated Gnb5−/− and Gnb5+/+ MIN6 cells at densities ranging from 3 × 105 to 12 × 105 cells/well on 12-well plates (Fig. 4). After 24 h, Gnb5−/− and Gnb5+/+ clones formed larger clusters when seeded at high density (Fig. 4A). Analysis by Western blotting (Fig. 4B) and immunohistochemistry showed that Gnb5 knockout does not influence E-cadherin expression levels; the same results were obtained when analyzing β-catenin and Connexin 36 (data not shown). These results indicate that Gnb5 knockout does not affect cadherin-mediated adhesion signaling in MIN6 cells.

Figure 4.

Gnb5 knockout reduces the impact of cell density on insulin secretion. A, representative phase-contrast images of cell culture at low and high density (3 × 105 versus 9 × 105 cells/well) at ×100 magnification. Shown are Gnb5−/− cells, which are visually indistinguishable from controls. B, representative immunoblot showing E-Cadherin (E-cad) expression in cultures of different densities and genotypes. Shown are samples at 6, 9, and 12 × 105 cells/well. Equal amounts of cells were loaded, and actin was used as a loading control. C, Gnb5+/+ (gray columns) or Gnb5−/− (open columns) cells were plated at the four indicated densities in 12-well plates, stimulated with 16.7 mm glucose with or without 100 μm Oxo-M, and secreted insulin was measured. ***, p < 0.001. D, per-well insulin secretion was normalized by cell density to determine levels of individual cell secretion. Data points show the average of six independent experiments. Error bars show S.D.

We then measured the Oxo-M-stimulated insulin release in these cultures. The values of insulin released (Fig. 4C) in each well were normalized to the number of cells (Fig. 4D).

For Gnb5+/+ cells, quadrupling the seeding density caused a 10-fold rise in insulin secretion per well, showing that the increase in insulin release is not directly proportional to that of cell number. Insulin secretion per cell rises from 4.13 ± 0.64 pg/liter to 8.58 ± 1.33 pg/liter (n = 6, p = 5.84 × 10−6), supporting the notion that signaling associated with β cell adhesion improves stimulated insulin release (34, 36). In Gnb5−/− cells, quadrupling the plating density resulted in a proportional 4-fold increase in the amount of insulin release per well (from 0.50 ± 0.02 μg/liter to 2.07 ± 0.57 μg/liter), showing that individual cells release the same amount of insulin regardless of aggregation. We concluded that Gnb5 knockout prevents the improvement in secretory performance that occurs in Gnb5+/+ cells upon an increase in cell density.

To rule out the possibility that the enhancement in insulin secretion in larger MIN6 aggregates could be caused by soluble factors, we collected conditioned medium from high-density cultures and applied it to low-density cultures. This medium had no effect (data not shown). This finding implicates direct cell-to-cell contacts rather than a soluble factor(s) in promotion of GSIS in the denser MIN6 cultures; this is consistent with previous reports (35, 37).

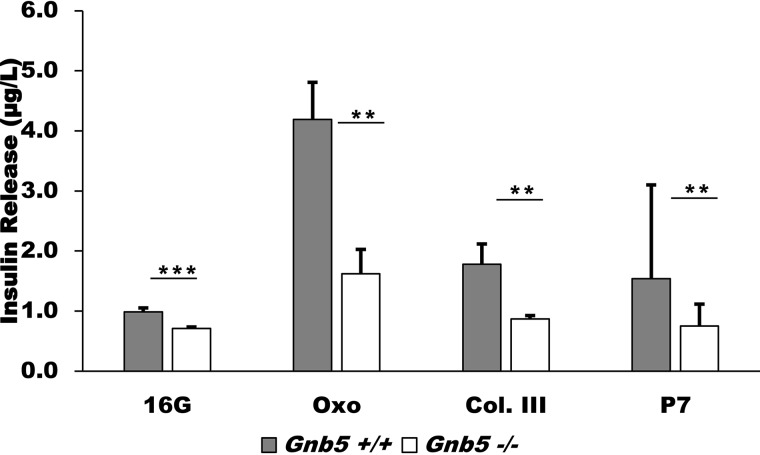

An interesting family of receptors mediating cell-to-cell adhesion and interactions with the extracellular matrix is adhesion GPCRs (38, 39). Activity of the adhesion GPCR GPR56 has recently been implicated in potentiating GSIS in β cells (40). A known endogenous ligand of GPR56 is collagen III, which promotes signaling through G13 and the Rho pathway (38). GPR56 is also activated by P7, a synthetic peptide designed to mimic the intrinsic agonist sequence of the receptor (39). We compared the response to these two ligands in our Gnb5+/+ and Gnb5−/− MIN6 cells (Fig. 5). In Gnb5+/+ cells, treatment with 0.5 μm collagen III resulted in an almost 2-fold (from 0.99 ± 0.07 μg/liter to 1.78 ± 0.62 μg/liter) enhancement of GSIS compared with samples treated with 16.7 mm glucose only. This stimulation was lower than with Oxo-M but similar to values obtained with secretagogues such as GLP-1 and forskolin (Fig. 3). Treatment of Gnb5+/+ cells with 50 μm P7 resulted in similar stimulation as treatment with collagen III (1.54 ± 0.33 μg/liter). Gnb5 knockout abrogated the effects of both ligands, which is consistent with the idea that Gβ5–R7 in MIN6 cells promotes multiple insulinotropic pathways, including G12/13.

Figure 5.

Gnb5 knockout abrogates insulinotropic activity of collagen III and P7, agonist peptides of GPR56. Gnb5+/+ and Gnb5−/− cells were stimulated with 0.5 μm collagen III (Col. III) or 50 μm P7 in the presence of 16.7 mm glucose. Shown are raw ELISA readings from two independent cell culture experiments; mean ± S.D. Statistical analysis is reported as the difference between 16G and each stimulant within genotypes. *, p < 0.05; **, p < 0.01; ***, p < 0.001; ns, not significant. Oxo, Oxo-M.

Effect of Gnb5 knockout on PKC-mediated phosphorylation

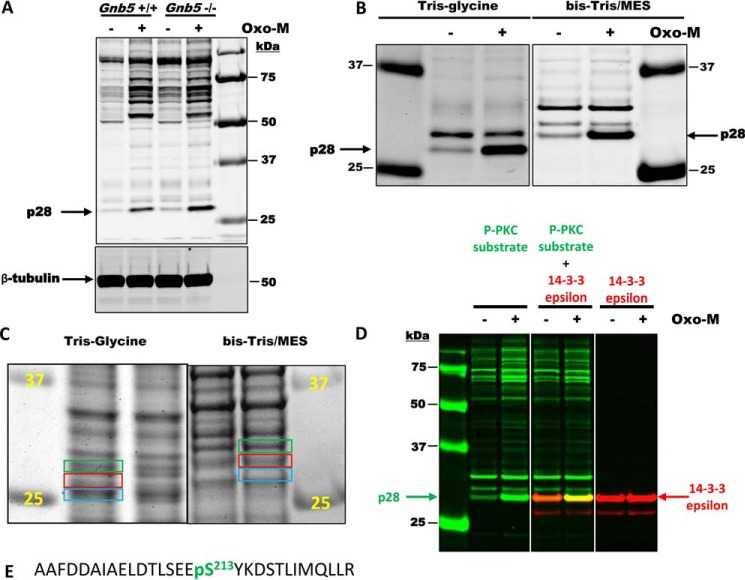

Our earlier study indicated that Gβ5–R7 may regulate Oxo-M–mediated insulin release via changes in protein kinase activity (24). Here we probed MIN6 cell lysates with an antibody raised against a phosphorylated peptide corresponding to the PKC substrate consensus sequence (K/R)XpSX(K/R). According to the immunoblot analysis, treatment of MIN6 cells with Oxo-M resulted in a notable increase in phosphorylation of multiple proteins (Fig. 6A). The overall patterns of PKC-mediated phosphorylation were very similar between the Gnb5+/+ and Gnb5−/− MIN6 clones. However, phosphorylation of one of the proteins with an apparent molecular mass of ∼28 kDa (p28) was increased about 2-fold in Gnb5−/− cells.

Figure 6.

PKC phosphorylates 14-3-3ϵ in MIN6 cells in a Gnb5-dependent manner. A, MIN6 cells were treated with or without 100 mm Oxo-M, and cell lysates were analyzed by Western blotting with anti-phospho-PKC substrate and β-tubulin antibodies. Note the strong PKC-mediated phosphorylation of the protein with an apparent molecular mass of 28 kDa (p28). This phosphorylation is increased ∼2-fold in Gnb5−/− cells. Sizes of protein standards are indicated on the right. B, MIN6 lysates were subjected to electrophoresis using two different buffer systems: Tris/glycine and BisTris/MES running buffer. Migration of p28 in these systems is different relative to protein markers. C, MIN6 lysates were subjected to electrophoresis using two different buffer systems, and the gels were stained with Coomassie Blue G250. Areas of the gels corresponding to p28 (red rectangles) were cut out and used for MS analysis. Areas right above and below (green and blue rectangles) were also analyzed by MS. D, confirmation of 14-3-3ϵ as a p28 PKC substrate. MIN6 lysates were subjected to electrophoresis using the BisTris/MES system. After transfer, the membrane was cut into three pieces and analyzed by Western blotting with anti-phospho-PKC substrate, 14-3-3ϵ, or a mixture of two antibodies. Rabbit anti-phospho-PKC substrate was visualized in the 680-nm channel (green). Mouse anti-14-3-3ϵ antibody was visualized in the 800-nm channel (red). E, the sequence of a 14-3-3ϵ phosphopeptide identified by MS analysis.

To identify p28, we excised the protein band from the gel and performed MS analysis. As expected, the gel slice contained hundreds of proteins. To narrow down the list, we took advantage of the fact that the mobility of proteins slightly changes depending on the buffer system used in electrophoresis. Indeed, when resolved on a BisTris gel using MES running buffer, p28 moved slower relative to 25- and 37-kDa protein standards (Fig. 6B), with an apparent molecular mass of ∼30 kDa. We expected proteins comigrating with p28 in the 30-kDa band to be different from those that comigrated with p28 in the Tris/glycine system (Fig. 6C). To distinguish p28 from contaminants, we searched for proteins that were enriched in the ∼28-kDa area of the gel (Fig. 6C, red) compared with the adjacent gel slices (Fig. 6C, green and blue); more than 20 proteins fit that criterion. Analysis of all sets of MS data showed that most proteins enriched in the p28 (Tris/glycine) and 30-kDa (Tris/MES) bands were different. However, one protein was at the top of the list in both datasets: 14-3-3ϵ. We confirmed this using Western blot analysis with a mixture of phospho-PKC substrate (Fig. 6D, green) and 14-3-3ϵ (Fig. 6D, red) antibodies. Furthermore, the most abundant phosphopeptide identified via MS analysis was the 14-3-3ϵ peptide containing Ser213, which we believe to be the one phosphorylated by PKC (Fig. 6E).

Discussion

The endocrine pancreas responds to fluctuations in plasma glucose concentration and to a variety of other cues. For example, the nervous system can prime the pancreas to upcoming nutrient intake, enhancing GSIS via released acetylcholine (12, 28, 41). Multiple membrane receptors on β cells augment or suppress GSIS, and the network of downstream signaling proteins integrates the stimuli and optimizes the resulting insulin output. Our previous study showed that ablation of the Gβ5–R7 complex caused a reduction in serum insulin levels in vivo (29), and subsequent experiments with isolated islets and MIN6 cells supported the notion that Gβ5–R7 is a positive modulator of cholinergic stimulation of GSIS (24). Our analyses of Oxo-M–stimulated flux of Ca2+, cAMP, and diacylglycerol did not reveal a notable change in Gnb5−/− MIN6 cells, and in Gnb5−/− islets there was only a small reduction in the frequency of Ca2+ oscillations (24). The apparent promotion of M3R-stimulated GSIS by Gβ5–R7 was unexpected because RGS proteins are known inhibitors of GPCR signaling. In this paper, we further explored the role of Gβ5–R7 in insulin secretion.

The main finding reported here is that knockout of Gnb5 suppresses insulin release stimulated not only by the cholinergic receptor M3R but also by other GPCRs and even glucose (Figs. 2, 3, and 5). In our previous studies, we concentrated on the role of Gβ5–R7 in regulation of M3R-mediated insulin secretion rather than other insulinotropic pathways because muscarinic agonists are three to six times more efficacious than other secretagogues (Fig. 3) (11, 24). In this study, our experiments with latrunculin B enhanced all tested MIN6 responses (Fig. 1), highlighting the negative effects of Gnb5 knockout on the insulinotropic effects of glucose (Fig. 2). The subsequent experiments provided evidence that the Gβ5–R7 complex is also needed for appropriate signaling through other Gq-, G12-, and Gs-coupled receptors. At the same time, our data on MIN6 cells and islets showed that total insulin content or its release caused by K+-induced membrane depolarization was indistinguishable between the Gnb5−/− and Gnb5+/+ phenotypes. Thus, the reduction in insulin release by Gnb5−/− MIN6 cells and primary islets cannot be attributed to changes in insulin content or membrane potential and suggests that Gβ5–R7 has a role in controlling the metabolic amplifying pathway (1, 2).

Another interesting finding made in this paper concerns GPR56 (gene: ADGRG1), an adhesion GPCR highly expressed in β cells (42). GPR56 couples to G12/13 and is activated by collagen III and the seven-amino-acid fragment (P7) of the extracellular domain, which acts as a tethered agonist (39). Our data showed that collagen III and P7 facilitated GSIS in Gnb5+/+ but not in Gnb5−/− cells (Fig. 5), indicating that Gβ5–R7 is required for GPR56- and/or G12-mediated signaling. One possible mechanism explaining this effect could be involvement of the direct interaction between Gβ5–R7 and G12/13. It has been reported recently that the Gβ5–RGS7 complex coimmunoprecipitates with G13 from the neuroblastoma cell line Neuro2A, and this interaction is implicated in Rho signaling and actin dynamics (21). Although in this study we did not find an obvious link between Gβ5–R7 and the Rho pathway and/or actin remodeling, regulation of G12/13 signaling by the Gβ5–R7 complex warrants further investigation.

Although the Gβ5–R7 complex acts as an enhancer of insulinotropic stimuli in β cells, it has an inhibitory effect in other biological systems. In various CNS neurons, it has the canonical inhibitory role of an RGS protein, i.e. knockout of Gnb5 or R7 proteins enhances Gi signaling, evidently by extending the GTP-bound state of the G proteins (43). We also found that Gβ5–R7 attenuates cell function in other systems, i.e. Gnb5 knockout enhances constriction of mouse pupillary smooth muscle via endogenous M3R (24). In transfected Chinese hamster ovary-K1 cells, Gβ5–RGS7 suppresses Ca2+ signaling induced by M3R via a non-GTPase-activating protein mechanism that implies direct interaction with the receptor (44). Therefore, we propose that Gβ5–R7 promotes insulin secretion via a novel molecular mechanism that needs to be understood.

Gnb5 knockout hinders the effect of high glucose, a permissive factor for insulin secretion, which can explain why many GPCR pathways that modulate GSIS are affected. The breadth of the Gnb5 knockout effect on insulinotropic stimuli suggests that the mechanism promoted by Gβ5–R7 is situated downstream of multiple pathways. All secretory pathways converge to enhance exocytosis, a process that includes vesicular trafficking and membrane fusion. Our data showed that actin depolymerization does not require Gβ5–R7 (Fig. 1), and so the Gβ5–R7-dependent insulinotropic event(s) is/are likely to be downstream of actin remodeling. Because the effect of K+-induced plasma membrane depolarization is not affected by Gnb5 knockout (Fig. 3), this step should be upstream of vesicle–membrane fusion.

Exocytosis depends on formation of the SNARE complex. This complex is composed of three main components: the vesicle-bound VAMP2, which binds to two target membrane proteins, syntaxin1A and SNAP25 (45). It was shown that SNAP25 in neuronal cells can directly interact with the conventional Gβγ complexes, influencing neurotransmitter release (46–48). Considering that the Gβ5-GGL moiety of the Gβ5–R7 complex may have a similar role as conventional Gβγ complexes, we hypothesize that Gβ5–R7 can promote the docking of insulin granules, i.e. increasing the pool of secretory vesicles that are ready for release. Furthermore, there is a structural homology between R7BP and syntaxin family SNARE complex proteins (49), providing a basis for a potential protein-protein interaction between the DEP domain of the R7 protein and syntaxin.

In beta cells, components of the SNARE complex, SNAP25, munc18, and synaptotagmin, have been identified as key substrates of PKC phosphorylation. Phosphorylation of these proteins is thought to promote insulin exocytosis through facilitating the formation of the SNARE complex, sensitizing the complex to calcium and increasing the amount of primed insulin vesicles available for exocytosis (45). We hypothesize that Gβ5–R7 is required for regulation of exocytosis-related kinase activity; for example, serving as an adapter protein that facilitates phosphorylation of these substrates.

Our results show that Gnb5 knockout in β cells affects phosphorylation patterns evoked by Oxo-M stimulation, and we have begun identification of the substrates of PKC for which phosphorylation depends on the presence Gβ5–R7. So far, we have demonstrated that Gnb5 knockout enhances phosphorylation of 14-3-3ϵ. The exact effect of this phosphorylation is not known, but it has been shown that 14-3-3 proteins can stimulate exocytosis (50, 51). Phosphorylation of 14-3-3 typically inhibits its interaction with target proteins (52). Therefore, we can speculate that, by inhibiting 14-3-3ϵ phosphorylation, Gβ5–R7 promotes its interaction with target proteins and, thus, exocytosis. However, a causal relationship between Gnb5-dependent kinase activity and the effect of Gβ5–R7 on insulin secretion remains to be elucidated.

Experimental procedures

Materials

Latrunculin B (ab144291) was purchased from Abcam (Cambridge, MA). Oxotremorine M (Oxo-M, sc-203656) was purchased from Santa Cruz Biotechnology (Dallas, TX). Antibodies against phospho-Ser PKC substrates (2261) and polyclonal rabbit anti-E-cadherin (3195) were purchased from Cell Signaling Technology (Danvers, MA). The mouse mAb against actin (MAB1501R) was purchased from Sigma-Aldrich (St. Louis, MO). Collagen III, forskolin, AVP, ADP, and GLP-1 were also purchased from Sigma-Aldrich. The antibody against 14-3-3ϵ (sc-23957) was purchased from Santa Cruz Biotechnology. The tethered agonist peptide of GPR56, P7 (TYFAVLM) (39), was kindly provided by Dr. Tall (University of Michigan). The cell culture inserts (PIXP01250) used in the static islet experiments had a diameter of 12 mm and 12-μm pores and were purchased from Sigma-Aldrich.

Animals

Animal procedures were performed according to the Guidelines for the Care and Use of Laboratory Animals (National Institutes of Health, Bethesda, MD), and protocols were approved by the University of Miami Committee on Use and Care of Animals. For this study, Gbn5−/− mice (18, 24, 29) were backcrossed for several generations to a C57Bl6/6J background. Age-matched (12- to 18-week-old) males were used in all experiments.

Islet isolation and treatment

Islets were isolated from mice pancreata through a combination of enzymatic and mechanical dissociation followed by purification on Histopaque 1077-1 Hybrid-Max (Sigma-Aldrich) gradients. Islets were incubated overnight in RPMI 1640 medium (Corning Inc., Corning, NY) supplemented with 5 mm glucose. After this incubation period, islets were manually counted and sorted by size under a dissection microscope.

Static insulin secretion experiments were performed using five handpicked, similarly sized islets obtained from the isolation. Selected islets were incubated overnight in 24-well plates with RPMI 1640 medium containing 10% FBS and 5 mm glucose. An insert was placed in each well to ensure that the islets remained localized to a central area of the well during stimulation. Before stimulation, islets were allowed to equilibrate for 1 h at 37 °C under basal conditions (3 mm glucose). After equilibration, islets were stimulated for 1 h with low or high glucose (3 mm and 16.7 mm, respectively) and 100 μm Oxo-M or 10 μm forskolin in the presence of 16.7 mm glucose. After stimulation, the supernatant was carefully extracted from the outer edges of the insert to ensure that the islets would not be collected along with and contaminate the supernatant. The harvested supernatant was stored at −80 °C for later analysis of insulin content by ELISA. Values obtained from the ELISA were normalized to the total amount of insulin measured in acid ethanol extracts.

Insulin ELISA

Insulin was measured with a sandwich ELISA kit (Mercodia, Uppsala, Sweden) as described previously (24).

MIN6 culture

Two clones of MIN6 cells with passage numbers between 15–30 were used for these experiments: Gnb5+/+ and Gnb5−/−. These cells were created using the CRISPR-Cas9 system as described previously (24). The cells were maintained in culture at 37 °C and 5% CO2 in DMEM (Life Technologies) containing 10% fetal bovine serum (VWR International, West Chester, PA), 25 mm glucose, 100 units/ml penicillin, 100 μg/ml streptomycin, 50 μm tissue culture-grade β-mercaptoethanol, 10 mm HEPES, and 10 mm sodium pyruvate.

MIN6 cell stimulation

For latrunculin B experiments, cells were plated in DMEM on 12-well plates at an approximate seeding density of 6 × 105 cells/well. After 24 h, they were preincubated for 2 h at 37 °C in 3 mm glucose in modified Krebs-Ringer buffer (KRB; 115 mm NaCl, 4.7 mm KCl, 1.28 mm CaCl2, 1.2 mm MgSO4, 1.19 mm KH2PO4, 25 mm NaHCO3, and 10 mm HEPES (pH 7.2)). Cells were then stimulated with KRB containing 16.7 mm glucose alone or together with 100 μm Oxo-M or 10 μm latrunculin B for 30 min. The supernatant was collected and used for insulin ELISA.

For other stimulants, conditions were almost identical, but cells were plated on 24-well plates at an approximate seeding density of 5 × 105 cells/well. Stimulation times and reagent concentrations were dictated by the requirements of specific experiments.

Studies of cell density effects

MIN6 clones were plated in DMEM on 12-well plates at seeding densities of 3, 6, 9, and 12 × 105 cells/well. After 24 h, the cultures were evaluated for cell aggregate formation by phase-contrast microscopy using an inverted Nikon microscope with a ×10 objective. Prior to stimulation, cells were preincubated for 2 h at 37 °C in 3 mm glucose in modified KRB. Low-glucose KRB was aspirated and replaced with KRB containing 16.7 mm glucose alone or combined with 100 μm Oxo-M. After 30 min, the supernatant was collected for insulin ELISA, and the cells were harvested for Western blotting.

Western blotting

After the supernatant was collected for insulin release, MIN6 cells were collected and subjected to SDS-PAGE and immunoblotting. Typically, we loaded 20 μg of total protein. After transfer of proteins to nitrocellulose and incubation with primary and secondary antibodies, membranes were visualized using the Odyssey (LI-COR Biosciences, Lincoln, NE) IR fluorescence system. For quantitative analysis, the signal in the band of interest (i.e. PKC substrates) was normalized to that for actin in the same lane.

LC-MS/MS of the p28 band

MIN6 cells were grown in 6-well plates to ∼50% confluence, rinsed with Hanks Balanced Salt Solution (Thermo Fisher Scientific, Waltham, MA), and incubated in serum-free DMEM for 1 h. They were then stimulated with 100 μm Oxo-M for 5 min. The medium was aspirated, and the cells were lysed in 0.5 ml of 1× SDS sample buffer. Samples were sonicated to destroy chromosomal DNA and used for gel electrophoresis. Proteins were resolved on 10% Tris/glycine SDS gel/Tris/glycine running buffer or 10% BisTris SDS gel/MES running buffer (Thermo Fisher Scientific).

In the initial experiment to locate the PKC substrates, the same samples were run in duplicates on the same gel, which was then cut in half. One half was stained with Coomassie Blue G250 to visualize proteins. The other half was used for Western blotting with the rabbit polyclonal anti-phospho-Ser PKC substrate antibody. The Coomassie-stained gel and Western blot were scanned using the Odyssey imaging system (LI-COR Biosciences). 25- and 37-kDa protein standards were aligned, and the position of the p28 PKC substrate band was determined relative to other Coomassie-stained proteins.

For the preparative gel, ∼40 μg of total protein was loaded per lane into nine lanes. After electrophoresis, the gel was stained with Coomassie Blue G250, destained, and left overnight in 15% EtOH/3% AcOH. Approximately 1-mm slices corresponding to the location of the p28 band were excised from the gel. The bands right above and right below the p28 band were also cut out.

The gel slices were destained, reduced, alkylated, and digested with trypsin (53). The resulting peptides were extracted, reconstituted in 2% formic acid, and subjected to LC-MS/MS analysis (31).

LC-MS/MS was performed with a Thermo Scientific LTQ Orbitrap Fusion Lumos Tribrid mass spectrometer equipped with an Ultimate Nano-LC system and a C-18 column (Acclaim PepMap, 75 μm × 15 cm, 2 μm, 100 Å). 5 μl of the tryptic peptide solution was injected and eluted from the column using an acetonitrile, 0.1% formic acid gradient at a flow rate of 0.3 μl/min. The eluates were introduced into the source of the mass spectrometer on line. The microelectrospray ion source was operated at 2.3 kV. The digest was analyzed using the data-dependent multitask capability of the instrument, acquiring full-scan mass spectra from 300 to 1,700 Da at a resolution of 120,000. These mass spectra were followed by collision-induced dissociation experiments on the 15 most abundant ions in the mass spectra. These collision-induced dissociation spectra were performed with a collision energy of 28%. The products were analyzed in the Orbitrap mass spectrometer. Protein identification utilized Proteome Discoverer 1.4 (Thermo Fisher Scientific), the Mascot search engine (Matrix Science 2.5), and the mouse UniProt/Swiss Protein database (SwissProt 2016_07, 16,813 total mouse sequences). Database searches were restricted to three or fewer missed tryptic cleavage sites, precursor ion mass tolerance at 10 ppm, fragment ion mass tolerance at 0.02 Da, and a false discovery rate at 1%. Fixed modification was S-carbamidomethyl Cys, and variable modifications included Met oxidation, Asn and Gln deamidation, Ser and Thr phosphorylation with neutral loss, and Tyr phosphorylation.

Statistics

Data are presented as mean ± S.D. for the indicated number of experiments. Statistical significance was evaluated using single-factor analysis of variance. Data were considered significant at a value of p < 0.05.

Data availability

All data presented and discussed are contained within the manuscript.

Author contributions

Q. W., T. A. N. H., A. N. P., and V. Z. S. conceptualization; Q. W., T. A. N. H., and A. N. P. data curation; Q. W., T. A. N. H., A. N. P., G.-F. J., C. L., and V. Z. S. investigation; Q. W., T. A. N. H., A. N. P., G.-F. J., C. L., and V. Z. S. methodology; Q. W., T. A. N. H., and V. Z. S. writing-original draft; Q. W., T. A. N. H., A. N. P., G.-F. J., J. W. C., E. B.-M., and V. Z. S. writing-review and editing; G.-F. J. software; J. W. C., E. B.-M., and V. Z. S. resources; J. W. C., E. B.-M., and V. Z. S. supervision; J. W. C., E. B.-M., and V. Z. S. validation; V. Z. S. funding acquisition.

This work was supported by NIDDK, National Institutes of Health Grants R01DK1054127 (to V. Z. S.), R01DK073716 and DK084236 (to E. B.-M.) and NEI, National Institutes of Health Grants EY025388 and EY025585 (to J. W. C.). The authors declare that they have no conflicts of interest with the contents of this article. The content is solely the responsibility of the authors and does not necessarily represent the official views of the National Institutes of Health.

- GSIS

- glucose-stimulated insulin secretion

- GPCR

- G protein–coupled receptors

- RGS

- regulator of G protein signaling

- GGL

- Gγ-like

- ROCK

- Rho-associated protein kinase

- Oxo-M

- oxotremorine M

- AVP

- arginine vasopressin.

References

- 1. Henquin J.-C. 2011) The dual control of insulin secretion by glucose involves triggering and amplifying pathways in β-cells. Diabetes Res. Clin. Pract. 93, S27–S31 10.1016/S0168-8227(11)70010-9 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Kalwat M. A., and Cobb M. H.. 2017) Mechanisms of the amplifying pathway of insulin secretion in the β cell. Pharmacol. Ther. 179, 17–30 10.1016/j.pharmthera.2017.05.003 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Komatsu M., Takei M., Ishii H., and Sato Y.. 2013) Glucose-stimulated insulin secretion: a newer perspective. J. Diabetes Investig. 4, 511–516 10.1111/jdi.12094 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Wang Z., and Thurmond D. C.. 2009) Mechanisms of biphasic insulin-granule exocytosis - roles of the cytoskeleton, small GTPases and SNARE proteins. J. Cell Sci. 122, 893–903 10.1242/jcs.034355 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Henquin J. C., Ishiyama N., Nenquin M., Ravier M. A., and Jonas J. C.. 2002) Signals and pools underlying biphasic insulin secretion. Diabetes 51, S60–S67 10.2337/diabetes.51.2007.S60 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Carlessi R., Chen Y., Rowlands J., Cruzat V. F., Keane K. N., Egan L., Mamotte C., Stokes R., Gunton J. E., Bittencourt P. I. H. D., and Newsholme P.. 2017) GLP-1 receptor signalling promotes β-cell glucose metabolism via mTOR-dependent HIF-1α activation. Sci. Rep. 7, 2661 10.1038/s41598-017-02838-2 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Jones B., Bloom S. R., Buenaventura T., Tomas A., and Rutter G. A.. 2018) Control of insulin secretion by GLP-1. Peptides 100, 75–84 10.1016/j.peptides.2017.12.013 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Mohan S., Moffett R. C., Thomas K. G., Irwin N., and Flatt P. R.. 2019) Vasopressin receptors in islets enhance glucose tolerance, pancreatic beta-cell secretory function, proliferation and survival. Biochimie 158, 191–198 10.1016/j.biochi.2019.01.008 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Balasubramanian, Ruiz de Azua I., Wess J., and Jacobson K. A.. 2010) Activation of distinct P2Y receptor subtypes stimulates insulin secretion in MIN6 mouse pancreatic β cells. Biochem. Pharmacol. 79, 1317–1326 10.1016/j.bcp.2009.12.026 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Farret A., Vignaud M., Dietz S., Vignon J., Petit P., and Gross R.. 2004) P2Y Purinergic potentiation of glucose-induced insulin secretion and pancreatic β-cell metabolism. Diabetes 53, S63–S66 10.2337/diabetes.53.suppl_3.S63 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Gautam D., Han S. J., Duttaroy A., Mears D., Hamdan F. F., Li J. H., Cui Y., Jeon J., and Wess J.. 2007) Role of the M3muscarinic acetylcholine receptor in β-cell function and glucose homeostasis. Diabetes Obes. Metab. 9, 158–169 10.1111/j.1463-1326.2007.00781.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Gilon P., and Henquin J.-C.. 2001) Mechanisms and physiological significance of the cholinergic control of pancreatic β-cell function. Endocr. Rev. 22, 565–604 10.1210/edrv.22.5.0440 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Ross E. M., and Wilkie T. M.. 2000) GTPase-activating proteins for heterotrimeric G proteins: regulators of G protein signaling (RGS) and RGS-like proteins. Annu. Rev. Biochem. 69, 795–827 10.1146/annurev.biochem.69.1.795 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Abramow-Newerly M., Roy A. A., Nunn C., and Chidiac P.. 2006) RGS proteins have a signalling complex: interactions between RGS proteins and GPCRs, effectors, and auxiliary proteins. Cell. Signal. 18, 579–591 10.1016/j.cellsig.2005.08.010 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Witherow D. S., and Slepak V. Z.. 2004) Biochemical purification and functional analysis of complexes between the G-protein subunit Gβ5 and RGS proteins. Methods Enzymol. 390, 149–162 10.1016/S0076-6879(04)90010-9 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Cheever M. L., Snyder J. T., Gershburg S., Siderovski D. P., Harden T. K., and Sondek J.. 2008) Crystal structure of the multifunctional Gβ5-RGS9 complex. Nat. Struct. Mol. Biol. 15, 155–162 10.1038/nsmb.1377 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Witherow D. S., Wang Q., Levay K., Cabrera J. L., Chen J., Willars G. B., and Slepak V. Z.. 2000) Complexes of the G protein subunit gβ5 with the regulators of G protein signaling RGS7 and RGS9: characterization in native tissues and in transfected cells. J. Biol. Chem. 275, 24872–24880 10.1074/jbc.M001535200 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Chen C. K., Eversole-Cire P., Zhang H., Mancino V., Chen Y. J., He W., Wensel T. G., and Simon M. I.. 2003) Instability of GGL domain-containing RGS proteins in mice lacking the G protein β-subunit G5β5. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 100, 6604–6609 10.1073/pnas.0631825100 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Anderson G. R., Posokhova E., and Martemyanov K. A.. 2009) The R7 RGS protein family: multi-subunit regulators of neuronal G protein signaling. Cell. Biochem. Biophys. 54, 33–46 10.1007/s12013-009-9052-9 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Slepak V. Z. 2009) Structure, function, and localization of Gβ5-RGS complexes. Prog. Mol. Biol. Transl. Sci. 86, 157–203 10.1016/S1877-1173(09)86006-7 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Scherer S. L., Cain M. D., Kanai S. M., Kaltenbronn K. M., and Blumer K. J.. 2017) Regulation of neurite morphogenesis by interaction between R7 regulator of G protein signaling complexes and G protein subunit Gα13. J. Biol. Chem. 292, 9906–9918 10.1074/jbc.M116.771923 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Nini L., Zhang J.-H., Pandey M., Panicker L. M., and Simonds W. F.. 2012) Expression of the Gβ5/R7-RGS protein complex in pituitary and pancreatic islet cells. Endocrine 42, 214–217 10.1007/s12020-012-9611-5 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Posokhova E., Wydeven N., Allen K. L., Wickman K., and Martemyanov K. A.. 2010) RGS6/Gβ5 complex accelerates IKACh gating kinetics in atrial myocytes and modulates parasympathetic regulation of heart rate. Circ. Res. 107, 1350–1354 10.1161/CIRCRESAHA.110.224212 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Wang Q., Pronin A. N., Levay K., Almaca J., Fornoni A., Caicedo A., and Slepak V. Z.. 2017) Regulator of G-protein signaling Gβ5–R7 is a crucial activator of muscarinic M3 receptor-stimulated insulin secretion. FASEB J. 31, 4734–4744 10.1096/fj.201700197RR [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Yang J., Huang J., Maity B., Gao Z., Lorca R. A., Gudmundsson H., Li J., Stewart A., Swaminathan P. D., Ibeawuchi S. R., Shepherd A., Chen C. K., Kutschke W., Mohler P. J., Mohapatra D. P., et al. (2010) RGS6, a modulator of parasympathetic activation in heart. Circ. Res. 107, 1345–1349 10.1161/CIRCRESAHA.110.224220 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Bansal G., Druey K. M., and Xie Z.. 2007) R4 RGS proteins: regulation of G-protein signaling and beyond. Pharmacol. Ther. 116, 473–495 10.1016/j.pharmthera.2007.09.005 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Villasenor A., Wang Z. V., Rivera L. B., Ocal O., Asterholm I. W., Scherer P. E., Brekken R. A., Cleaver O., and Wilkie T. M.. 2010) Rgs16 and Rgs8 in embryonic endocrine pancreas and mouse models of diabetes. Dis. Model Mech. 3, 567–580 10.1242/dmm.003210 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Ruiz de Azua I., Scarselli M., Rosemond E., Gautam D., Jou W., Gavrilova O., Ebert P. J., Levitt P., and Wess J.. 2010) RGS4 is a negative regulator of insulin release from pancreatic β-cells in vitro and in vivo. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 107, 7999–8004 10.1073/pnas.1003655107 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Wang Q., Levay K., Chanturiya T., Dvoriantchikova G., Anderson K. L., Bianco S. D., Ueta C. B., Molano R. D., Pileggi A., Gurevich E. V., Gavrilova O., and Slepak V. Z.. 2011) Targeted deletion of one or two copies of the G protein β subunit Gβ5 gene has distinct effects on body weight and behavior in mice. FASEB J. 25, 3949–3957 10.1096/fj.11-190157 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Kalwat M. A., Yoder S. M., Wang Z., and Thurmond D. C.. 2013) A p21-activated kinase (PAK1) signaling cascade coordinately regulates F-actin remodeling and insulin granule exocytosis in pancreatic beta cells. Biochem. Pharmacol. 85, 808–816 10.1016/j.bcp.2012.12.003 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Yuan X., Gu X., Crabb J. S., Yue X., Shadrach K., Hollyfield J. G., and Crabb J. W.. 2010) Quantitative proteomics: comparison of the macular bruch membrane/choroid complex from age-related macular degeneration and normal eyes. Mol. Cell. Proteomics 9, 1031–1046 10.1074/mcp.M900523-MCP200 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Riento K., and Ridley A.. 2003) ROCKS: multifunctional kinases in cell behaviour. Nat. Rev. Mol. Cell Biol. 4, 446–456 10.1038/nrm1128 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Rajan S., Dickson L. M., Mathew E., Orr C. M., Ellenbroek J. H., Philipson L. H., and Wicksteed B.. 2015) Chronic hyperglycemia downregulates GLP-1 receptor signaling in pancreatic β-cells via protein kinase A. Mol. Metab. 4, 265–276 10.1016/j.molmet.2015.01.010 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Chowdhury A., Satagopam V. P., Manukyan L., Artemenko K. A., Fung Y. M., Schneider R., Bergquist J., and Bergsten P.. 2013) Signaling in insulin-secreting MIN6 pseudoislets and monolayer cells. J. Proteome Res. 12, 5954–5962 10.1021/pr400864w [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Kelly C., Guo H., McCluskey J. T., Flatt P. R., and McClenaghan N. H.. 2010) Comparison of insulin release from MIN6 pseudoislets and pancreatic islets of Langerhans reveals importance of homotypic cell interactions. Pancreas 39, 1016–1023 10.1097/MPA.0b013e3181dafaa2 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Bosco D., Orci L., and Meda P.. 1989) Homologous but not heterologous contact increases the insulin secretion of individual pancreatic B-cells*1. Exp. Cell Res. 184, 72–80 10.1016/0014-4827(89)90365-0 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. Parnaud G., Lavallard V., Bedat B., Matthey-Doret D., Morel P., Berney T., and Bosco D.. 2015) Cadherin engagement improves insulin secretion of single human β-cells. Diabetes 64, 887–896 10.2337/db14-0257 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38. Paavola K. J., and Hall R. A.. 2012) Adhesion G protein-coupled receptors: signaling, pharmacology, and mechanisms of activation. Mol. Pharmacol. 82, 777–783 10.1124/mol.112.080309 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39. Stoveken H. M., Hajduczok A. G., Xu L., and Tall G. G.. 2015) Adhesion G protein-coupled receptors are activated by exposure of a cryptic tethered agonist. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 112, 6194–6199 10.1073/pnas.1421785112 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40. Olaniru O. E., Pingitore A., Giera S., Piao X., Castañera González R., Jones P. M., and Persaud S. J.. 2018) The adhesion receptor GPR56 is activated by extracellular matrix collagen III to improve β-cell function. Cell. Mol. Life Sci. 75, 4007–4019 10.1007/s00018-018-2846-4 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41. Satin L. S., and Kinard T. A.. 1998) Neurotransmitters and their receptors in the islets of Langerhans of the pancreas: what messages do acetylcholine, glutamate, and GABA transmit? Endocrine 8, 213–223 10.1385/ENDO:8:3:213 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42. Haitina T., Olsson F., Stephansson O., Alsiö J., Roman E., Ebendal T., Schiöth H. B., and Fredriksson R.. 2008) Expression profile of the entire family of adhesion G protein-coupled receptors in mouse and rat. BMC Neurosci. 9, 43 10.1186/1471-2202-9-43 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43. Patil D. N., Rangarajan E. S., Novick S. J., Pascal B. D., Kojetin D. J., Griffin P. R., Izard T., and Martemyanov K. A.. 2018) Structural organization of a major neuronal G protein regulator, the RGS7-Gβ5–R7BP complex. eLife 7, e42150 10.7554/eLife.42150 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44. Sandiford S. L., Wang Q., Levay K., Buchwald P., and Slepak V. Z.. 2010) Molecular organization of the complex between the muscarinic M3 receptor and the regulator of G protein signaling, Gβ5-RGS7. Biochemistry 49, 4998–5006 10.1021/bi100080p [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45. Trexler A. J., and Taraska J. W.. 2017) Regulation of insulin exocytosis by calcium-dependent protein kinase C in β cells. Cell Calcium 67, 1–10 10.1016/j.ceca.2017.07.008 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46. Zurawski Z., Page B., Chicka M. C., Brindley R. L., Wells C. A., Preininger A. M., Hyde K., Gilbert J. A., Cruz-Rodriguez O., Currie K. P. M., Chapman E. R., Alford S., and Hamm H. E.. 2017) Gβγ directly modulates vesicle fusion by competing with synaptotagmin for binding to neuronal SNARE proteins embedded in membranes. J. Biol. Chem. 292, 12165–12177 10.1074/jbc.M116.773523 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47. Zurawski Z., Rodriguez S., Hyde K., Alford S., and Hamm H. E.. 2016) Gβγ binds to the extreme C terminus of SNAP25 to mediate the action of Gi/o-coupled G protein–coupled receptors. Mol. Pharmacol. 89, 75–83 10.1124/mol.115.101600 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48. Zurawski Z., Thompson Gray A. D., Brady L. J., Page B., Church E., Harris N. A., Dohn M. R., Yim Y. Y., Hyde K., Mortlock D. P., Jones C. K., Winder D. G., Alford S., and Hamm H. E.. 2019) Disabling the Gβγ-SNARE interaction disrupts GPCR-mediated presynaptic inhibition, leading to physiological and behavioral phenotypes. Sci. Signal. 12, eaat8595 10.1126/scisignal.aat8595 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49. Martemyanov K. A., Yoo P. J., Skiba N. P., and Arshavsky V. Y.. 2005) R7BP, a novel neuronal protein interacting with RGS proteins of the R7 family. J. Biol. Chem. 280, 5133–5136 10.1074/jbc.C400596200 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50. Broadie K., Rushton E., Skoulakis E. M., and Davis R. L.. 1997) Leonardo, a Drosophila 14-3-3 protein involved in learning, regulates presynaptic function. Neuron 19, 391–402 10.1016/S0896-6273(00)80948-4 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51. Morgan A., and Burgoyne R. D.. 1992) Exol and Exo2 proteins stimulate calcium-dependent exocytosis in permeabilized adrenal chromaff in cells. Nature 355, 833–836 10.1038/355833a0 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52. Aitken A. 2011) Post-translational modification of 14-3-3 isoforms and regulation of cellular function. Semin. Cell Dev. Biol. 22, 673–680 10.1016/j.semcdb.2011.08.003 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53. Bollinger K. E., Crabb J. S., Yuan X., Putliwala T., Clark A. F., and Crabb J. W.. 2011) Quantitative proteomics: TGFβ2 signaling in trabecular meshwork cells. Invest. Opthalmol. Vis. Sci. 52, 8287–8294 10.1167/iovs.11-8218 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Data Availability Statement

All data presented and discussed are contained within the manuscript.