Abstract

Amyloid aggregation of pathological proteins is closely associated with a variety of neurodegenerative diseases, and α-synuclein (α-syn) deposition and Tau tangles are considered hallmarks of Parkinson's disease and Alzheimer's disease, respectively. Intriguingly, α-syn and Tau have been found to co-deposit in the brains of individuals with dementia and parkinsonism, suggesting a potential role of cross-talk between these two proteins in neurodegenerative pathologies. Here we show that monomeric α-syn and the two variants of Tau, Tau23 and K19, synergistically promote amyloid fibrillation, leading to their co-aggregation in vitro. NMR spectroscopy experiments revealed that α-syn uses its highly negatively charged C terminus to directly interact with Tau23 and K19. Deletion of the C terminus effectively abolished its binding to Tau23 and K19 as well as its synergistic effect on promoting their fibrillation. Moreover, an S129D substitution of α-syn, mimicking C-terminal phosphorylation of Ser129 in α-syn, which is commonly observed in the brains of Parkinson's disease patients with elevated α-syn phosphorylation levels, significantly enhanced the activity of α-syn in facilitating Tau23 and K19 aggregation. These results reveal the molecular basis underlying the direct interaction between α-syn and Tau. We proposed that this interplay might contribute to pathological aggregation of α-syn and Tau in neurodegenerative diseases.

Keywords: α-synuclein, Tau protein (Tau), amyloid, aggregation, fibril, Parkinson's disease, Alzheimer's disease, neurodegeneration, protein misfolding, dementia, Lewy body

Introduction

Protein misfolding and amyloid aggregation are commonly identified in a variety of devastating human neurodegenerative diseases (1, 2). For instance, amyloid aggregation of α-synuclein (α-syn)4 is a key pathological characteristic of Parkinson's disease (PD) and other synucleinopathies (3, 4). Another amyloid protein, Tau, forms pathological amyloid aggregates in Alzheimer's disease (AD) and other tauopathies (5, 6). Intriguingly, accumulating clinical evidence shows a continuum between pure synucleinopathies and tauopathies (7–10). Many neurodegenerative disorders, such as Parkinson's disease dementia, the Lewy body variant of AD, and dementia with Lewy bodies, feature overlapping clinical symptoms of dementia and parkinsonism (8–11). More importantly, co-aggregation of pathological Tau and α-syn inclusions has been found in the brains of patients with these disorders (12, 13). Furthermore, animal studies showed that injection of preformed α-syn fibrils in the mouse brain triggers Tau aggregation and pathology (14). In contrast, knockout of α-syn or Tau can effectively abolish the pathology induced by α-syn aggregation in animal models (15, 16). Thus, α-syn and Tau may act synergistically to form a deleterious feedforward loop in disease development.

α-Syn contains 140 residues that can be divided into three regions: the N-terminal region, the central non-amyloid component (NAC) region, and the highly charged C-terminal region (17). The N-terminal region is responsible for membrane binding, which may be attributed to α-syn function in synaptic vesicle clustering as well as cytotoxicity of α-syn oligomers (18, 19). The NAC region is crucial for amyloid fibril formation (20, 21). The six well-known PD familial mutations are located in the NAC region, which can modulate the structures of amyloid fibrils and fibrillation kinetics in different ways (20, 22). In contrast, deletion of the C terminus of α-syn largely enhances its fibrillation capability (23–25). However, the association of the α-syn C terminus with pathology remains unclear.

Tau is a microtubule-binding protein, and six isoforms, because of alternative splicing, are found in the brain (26). Hyperphosphorylation of Tau leads to its detachment from microtubules, resulting in its mislocalization and ultimate pathological aggregation in the brains of patients with AD and other tauopathies (27–29). Four microtubule-binding repeat domains (R1–R4) have been shown to mediate Tau fibril formation (30). Previous studies also revealed that α-syn and Tau coprecipitate in vitro, and in vivo, both in the brains of patients and in mouse models (12, 31, 32). In addition, Tau and α-syn have been found to interact and promote each other's fibrillation (12, 13, 33, 34). However, the molecular basis underlying the interplay between α-syn and Tau is poorly understood, and it is unclear whether factors such as posttranslational modification or molecular chaperones regulate the interaction between α-syn and Tau.

In this study, we showed that Tau and α-syn monomers directly interacted with each other and co-aggregated and that this co-aggregation was synergistically facilitated by heterotypic association between Tau and α-syn. We further demonstrated that α-syn employs its C terminus to directly bind to the VQIVYK motif of the microtubule-binding domain of Tau. Disruption of this interaction abolished binding between the two proteins and co-aggregation of Tau and α-syn. More importantly, S129D was found to mimic Ser129 of PD, as both exhibited elevated levels of phosphorylation and dramatically enhanced the capability of α-syn to promote Tau fibrillation. Overall, these results reveal the essential role of the α-syn C terminus in mediating co-aggregation of α-syn and Tau and demonstrate how disease-related phosphorylation amplifies this deleterious effect under pathological conditions.

Results

α-Syn and Tau facilitate each other's fibrillation

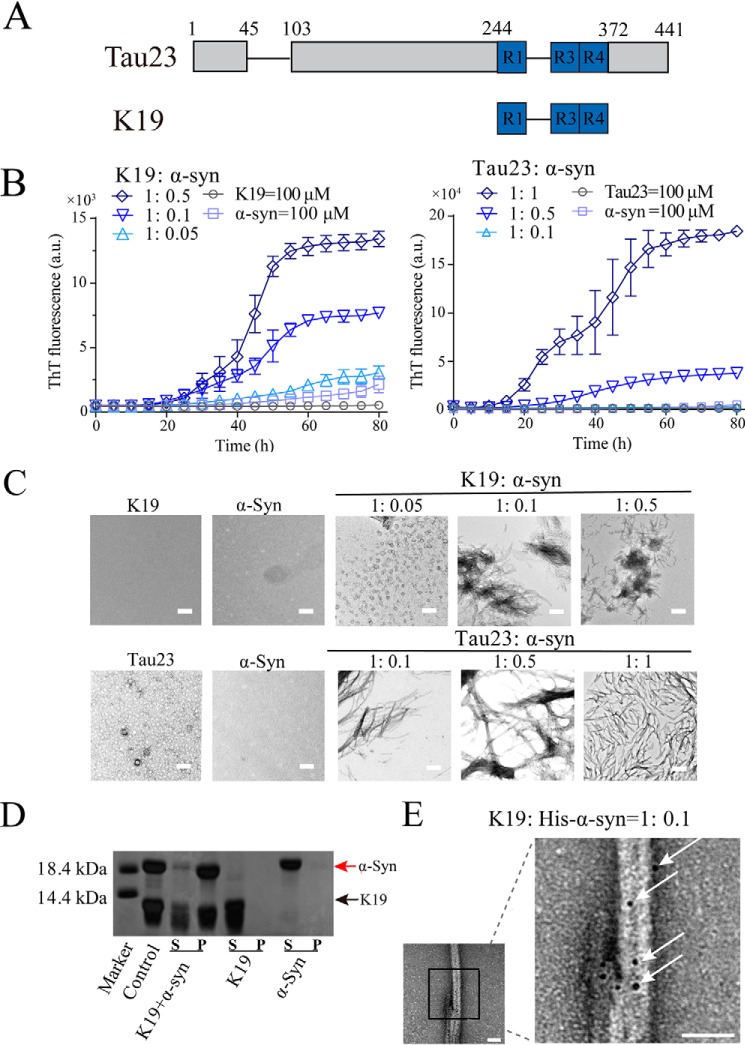

We first investigated whether α-syn could modulate the fibrillation of Tau. For this purpose, human Tau23 was prepared, along with the three microtubule-binding fragments of Tau-K19, containing the fibril core of Tau (Fig. 1A) (35). Monomeric Tau23, K19, and α-syn proteins were purified from Escherichia coli and assessed by size exclusion chromatography. The monomeric K19 resisted aggregation on its own in aqueous solution (Fig. 1, B and C). However, addition of α-syn at a molar ratio of α-syn:Tau as low as 1:20 induced rapid amyloid aggregation of K19, as monitored by a thioflavin T (ThT) kinetics assay at 37 °C and negative staining EM (NS-EM) (Fig. 1, B and C). As a control, another amyloid protein, fused in sarcoma low-complexity domain (FUS-LC), which mediates pathological fibril formation of FUS in ALS (36), had no effect on K19 fibrillation (supporting Fig. S1). In addition to K19, α-syn could also promote Tau23 amyloid aggregation in a concentration-dependent manner (Fig. 1, B and C). As observed in the control group, α-syn on its own did not form fibrils under the same conditions, even at a high concentration of 100 μm (Fig. 1, B and C).

Figure 1.

The α-Syn monomer facilitates fibrillation of Tau. A, domain organization of Tau23 and K19. R1, R3, and R4 represent the three microtubule-binding repeats of Tau. B, ThT kinetics of K19 (100 μm, left panel) and Tau23 (100 μm, right panel) amyloid aggregation facilitated by the α-syn monomer at the indicated molar ratios at 37 °C. The error bars denote mean ± S.D. with n = 3. Fibrillation buffer (1) containing 25 mm Bis-Tris, 1 mm MgCl2, 2 mm DTT, and 1 mm EDTA (pH 6.8) (preferred for Tau23/K19 fibrillation) was used in the assay. a.u., absorbance unit. C, NS-EM images of samples taken at the end point of the ThT kinetic assay in B. Scale bars = 500 nm. D, supernatant (S) and precipitates (P) of K19 and α-syn samples analyzed by SDS-PAGE. Samples of K19 alone (200 μm), α-syn alone (20 μm), and K19 (200 μm) premixed with α-syn (20 μm), incubated further at 80 h for co-aggregation (K19+α-syn), were analyzed. The control was taken from premixed K19 (200 μm) and α-syn (20 μm) without further incubation. All samples were prepared in fibrillation buffer (1). E, NS-EM image of fibrils formed by 200 μm K19 in the presence of 20 μm His-tagged α-syn (His-α-syn) and probed by nanogold particles. The region indicated by the black box is shown as a magnified image on the right, and arrows indicate attachment of nanogold particles on fibrils. Scale bars = 50 nm.

We next investigated whether Tau fibrils induced by α-syn were formed solely by K19 or by combined activity of K19 and α-syn. Fibrils formed under different conditions were centrifuged, dissolved, and checked by SDS-PAGE. As shown in Fig. 1D and Fig. S2, the α-syn–induced K19 fibril sample contained α-syn, demonstrating co-aggregation of K19 and α-syn. To further confirm this finding, we prepared α-syn with an N-terminal His-tag, which can bind to nanogold particles, and used it to promote fibrillation of K19. We directly visualized the nanogold particles in α-syn–induced Tau fibrils under NS-EM (Fig. 1E and Fig. S3), confirming that K19 fibrils induced by α-syn contained the α-syn protein.

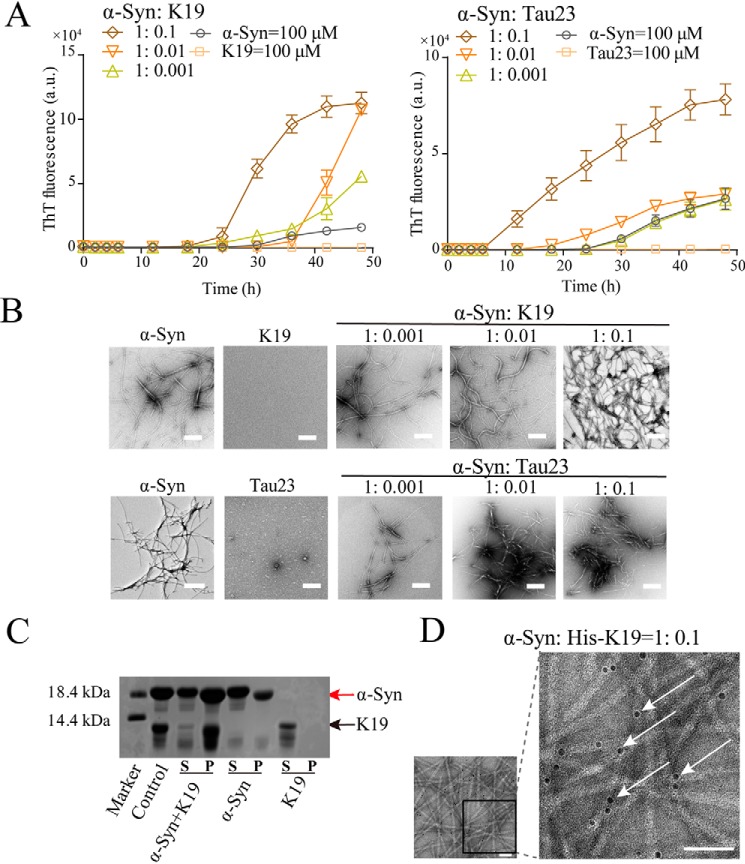

We next explored whether Tau can induce fibrillation of α-syn. As shown in Fig. 2, A and B, although α-syn only forms a small number of fibrils on its own, the ThT assay and NS-EM imaging demonstrated that α-syn rapidly formed abundant amyloid fibrils in the presence of the K19 or Tau23 monomer. Even a small amount of K19 at a 10:1 molar ratio of α-syn:K19 could efficiently induce α-syn fibrillation (Fig. 2, A and B). The Tau23 monomer exhibited a similar capability for inducing α-syn fibrillation (Fig. 2, A and B). However, FUS-LC, used as a control, could not promote aggregation of α-syn (Fig. S4). To further examine whether K19 co-aggregates with α-syn in this scenario, nanogold labeling and electrophoresis were carried out. As shown in Fig. 2C and Fig. S5, the K19-induced α-syn fibril comprised α-syn and K19 proteins. In addition, nanogold-labeled His-K19 associated with α-syn fibril was directly visualized using NS-EM (Fig. 2D).

Figure 2.

Tau facilitates α-syn fibrillation. A, ThT kinetics of α-syn (100 μm) aggregation facilitated by K19 (left panel) and Tau23 (right panel) at the indicated molar ratios at 37 °C. The error bars denote mean ± S.D. with n = 3. Fibrillation buffer (2) containing 14 mm MES (pH 6.8) (preferred for α-syn fibrillation) was used in the assay. a.u., absorbance unit. B, samples obtained at the end point of the ThT assay described in A were further examined by NS-EM. Scale bars = 500 nm. C, supernatants (S) and precipitates (P) of α-syn and K19 samples analyzed by SDS-PAGE. Samples of α-syn alone (200 μm), K19 alone (20 μm), and α-syn (200 μm) premixed with K19 (20 μm) incubated further for 80 h for co-aggregation (α-syn+K19) were analyzed. The control was taken from premixed α-syn (200 μm) and K19 (20 μm) without further incubation. All samples were prepared in fibrillation buffer (2). D, NS-EM images of fibrils formed by 200 μm α-syn incubated with 20 μm His-K19 and probed by nanogold particles. The black box region is magnified on the right, and arrows indicate attachment of nanogold particles on fibrils. Scale bars = 50 nm.

Intriguingly, we found that, compared with the monomeric form, preformed fibrils of K19 and Tau23 exhibited enhanced activity in promoting α-syn fibrillation at the same concentration (Fig. S6). In contrast, no enhanced activity of α-syn preformed fibrils of inducing fibrillation of the K19 or Tau23 monomer was observed (Fig. S7).

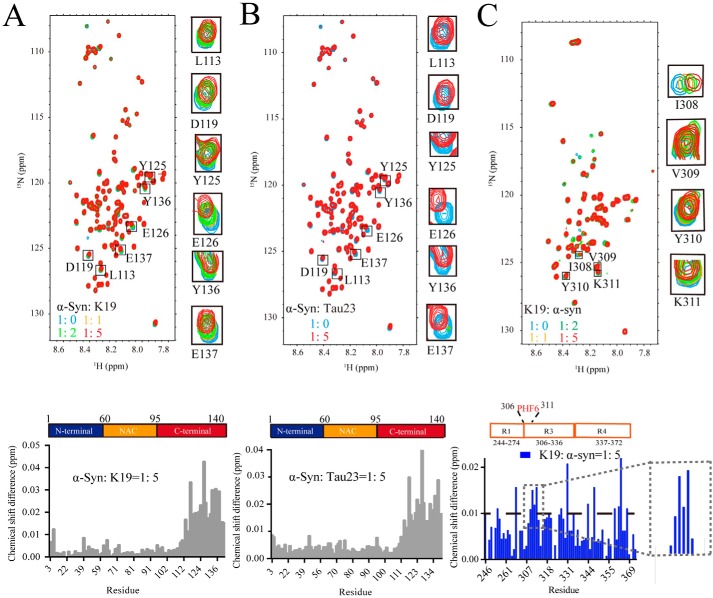

Interface between α-syn and Tau

NMR titration experiments were used to investigate the structural basis of the interaction between α-syn and Tau. To map the interface of α-syn for Tau binding, we titrated unlabeled K19 into a 15N-labeled α-syn monomer and monitored the changes in the 2D 1H-15N heteronuclear single-quantum coherence (HSQC) spectra of α-syn. Intriguingly, residues with significant chemical shift perturbations were clustered at the C terminus of α-syn, especially negatively charged residues such as aspartic acid and glutamic acid within residues 120–140 (Fig. 3A and Table S1). Notably, titration of the Tau23 monomer to 15N-labeled α-syn showed a similar pattern of chemical shift perturbations of the C-terminal residues of α-syn as that of K19 (Fig. 3B), demonstrating that K19 may serve as a major binding domain in Tau23 for α-syn binding. However, unlike the monomer, the Tau23 fibril could not induce any significant chemical shift changes in the α-syn monomer upon titration (Fig. S8). Because α-syn is a membrane-associated protein (17), we investigated whether the presence of lipids influences the interaction between α-syn and K19. We prepared a liposome mixture composed of 1-palmitoyl-2-oleoyl-sn-glycero-3-phosphoethanolamine:1,2-dioleoyl-sn-glycero-3-phospho-l-serine:1,2-dioleoyl-sn-glycero-3-phosphocholine lipids at a molar ratio of 5:3:2, which was mixed with 15N α-syn with at a molar ratio of 20:1. Next, a 5-fold molar concentration of K19 (compared with that of α-syn) was added to the mixture, and changes in the NMR spectra of α-syn were monitored. We found that only the C-terminal residues of α-syn exhibited significant chemical shift perturbations (Fig. S9); this result is consistent with that of 15N-α-syn alone titrated with K19 (Fig. 3A). Taken together, these results suggested that binding of α-syn on the membrane does not influence the interaction of α-syn and K19.

Figure 3.

Identification of the interface between α-syn and Tau. A, overlay of the 2D 1H-15N HSQC spectra of α-syn (50 μm, blue) and that titrated by K19 with concentrations of 50 μm (yellow), 100 μm (green), and 250 μm (red). The cross-peaks of residues with significant chemical shift changes of Leu113, Asp119, Tyr125, Glu126, Tyr136, and Glu137 are enlarged and displayed on the right. Residue-specific changes in the chemical shift of α-syn signals in the presence of 5-fold K19 are displayed in the bottom panel. The domain organization of α-syn is shown. B, overlay of the 2D 1H-15N HSQC spectra of α-syn (50 μm, blue) and that titrated by Tau23 (250 μm, red). Cross-peaks of the residues Leu113, Asp119, Tyr125, Glu126, Tyr136, and Glu137 are enlarged and displayed on the right. Residue-specific changes in the chemical shift of α-syn signals in the presence of 5-fold Tau23 are displayed in the bottom panel. C, overlay of the 2D 1H-15N HSQC spectra of K19 (50 μm, blue) titrated by α-syn at concentrations of 50 μm (yellow), 100 μm (green), and 250 μm (red). Cross-peaks of the residues Ile308, Val309, Tyr310, and Lys311 are enlarged and displayed on the right. Residue-specific changes in the chemical shift of K19 signals in the presence of 5-fold α-syn are shown in the bottom panel. The PHF6 motif (VQIVYK, residues 306–311) with the most obvious and continuous chemical shift changes of K19 is enlarged and displayed on the right. The domain organization of K19 is shown at the top, with the PHF6 motif highlighted in red.

To further identify the interface of K19 for α-syn binding, unlabeled α-syn was titrated to 15N-labeled K19. Almost all residues exhibited some degree of chemical shift perturbations (Fig. 3C and Table S2). The most perturbed regions appeared to be within or adjacent to the VQIVYK motif of R3, which is known as the PHF6 motif and was previously identified as a key amyloidogenic region of Tau (35). Notably, upon titration with the C-terminal 40-residue deletion mutant of α-syn (α-syn1–100), the chemical shift perturbation of the PHF6 motif was largely diminished (Fig. S10). To further validate the interface of K19 to α-syn, a paramagnetic relaxation enhancement experiment was performed. Because our results showed that the C terminus of α-syn interacts with K19, we introduced a nitroxide spin label, S-(1-oxyl-2,2,5,5-tetramethyl-2,5-dihydro-1H-pyrrol-3-yl) methyl methanesulfonothioate (MTSL), at residue Ala124 of α-syn (MTSL–A124C–α-syn). We then mixed 15N-labeled K19 (50 μm) with 50 μm MTSL–A124–α-syn. NMR spectra were collected in the absence (paramagnetic environment) and presence (diamagnetic environment) of 1 mm sodium ascorbate. As shown in Fig. S11, a significant decrease in signal intensity (Ipara/Idia < 0.5) was observed in the PHF6 region, further validating that the C terminus of α-syn binds to the PHF6 motif to mediate α-syn–Tau binding. Together, these results show that α-syn utilizes its negatively charged C terminus to interact with Tau, mainly via its PHF6 motif.

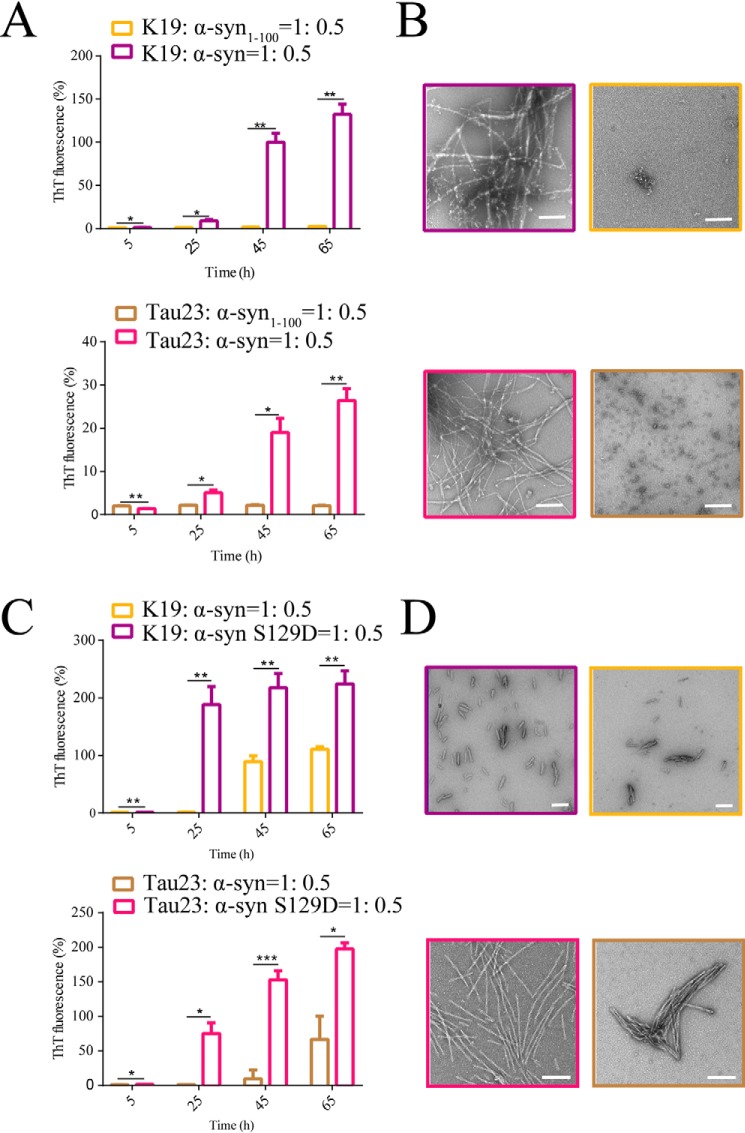

Because truncation of the C terminus of α-syn abolishes the interaction between Tau and α-syn, we next examined whether disruption of the binding between Tau and α-syn directly influences the synergistic effects of Tau and α-syn fibrillation. As shown in Fig. S12, neither K19 nor Tau23 promoted fibrillation of α-syn1–100, in which the C-terminal 40 residues were deleted. Conversely, truncation of the C terminus diminished the capacity of α-syn to promote fibrillation of K19 or Tau23 (Fig. 4, A and B). These results demonstrate that direct interaction between the C terminus of the α-syn monomer and Tau is essential to synergistically facilitate their co-aggregation.

Figure 4.

Modification and truncation of the C terminus of α-syn directly influences co-aggregation of Tau and α-syn. A, comparison of fibrillation of K19 (100 μm) or Tau23 (100 μm) in the presence of α-syn (50 μm) and α-syn1–100 (50 μm), monitored by the ThT fluorescence assay at 37 °C in fibrillation buffer (1). The error bars denote mean ± S.D. with n = 3. *, p < 0.05 by unpaired t test; **, p < 0.01. B, representative transmission EM images of K19/Tau23 fibrils from the ThT assay from A, taken at the 65-h time point. Scale bars = 100 nm. C, phosphorylation mimic (S129D) of α-syn significantly enhances co-aggregation of Tau and α-syn. We performed a ThT kinetics assay of the fibrillation of K19 (12.5 μm)/Tau23 (12.5 μm) in the presence of α-syn (6.25 μm) and α-syn S129D (6.25 μm) at 37 °C in fibrillation buffer (1). ThT fluorescence at the 5-, 25-, 45-, and 65-h time points is plotted for comparison. The error bars denote means ± S.D. with n = 3. *, p < 0.05 by unpaired t test; **, p < 0.01; ***, p < 0.001. D, representative NS-EM images of samples obtained from the ThT assay from C at the 65-h time point are shown on the right. Scale bars = 100 nm.

S129D significantly enhances co-aggregation of Tau and α-syn

Because it was identified that the C terminus of α-syn, especially residues 120–140, was found to be responsible for Tau binding and promoting co-aggregation of both proteins, we next investigated whether modification within this region may influence the co-aggregation process. Ser129 phosphorylation is one of the most important disease-related modifications of α-syn and has been identified as a pathological signature in the brains of PD patients (37, 38). However, the specific relationship of this signature to PD pathology is largely unknown. To study its effect in the cross-talk between α-syn and Tau, we prepared a single point mutation, S129D, to mimic Ser129-phosphorylated α-syn under pathological conditions. Intriguingly, compared with the WT α-syn, S129D exhibited a significantly enhanced effect in facilitating Tau23 and K19 amyloid aggregation, as measured by a ThT kinetics assay and NS-EM imaging (Fig. 4, C and D, and Fig. S13, A and B). However, S129D showed a similar binding affinity to Tau as WT α-syn when measured by biolayer interferometry (Fig. S13C and Table S3). These results indicate that S129D does not significantly strengthen overall binding between α-syn and the Tau monomer despite its much stronger capability to induce co-aggregation of α-syn and Tau.

Discussion

Despite the fact that Tau and α-syn massively aggregate under pathological conditions (3, 6), they are both highly soluble proteins and do not easily form amyloid aggregates on their own in vitro or under physiological conditions. Using NMR spectroscopy combined with molecular dynamics simulations, two groups have shown that the α-syn monomer adopts a compact conformation restrained by transient long-range intramolecular interactions between the negatively charged C-terminal residues and residues ∼30–100 in the central region of α-syn (39, 40). Theillet et al. (41) further showed that the central NAC region of the α-syn monomer is buried in the compact structure in the cell. The compact conformations are mainly stabilized by long-range intramolecular interactions between the negatively charged C terminus and the aggregation-prone NAC region of α-syn (39–41). Impairment of the intramolecular interaction in the α-syn monomer may disrupt its compact conformation and promote α-syn fibrillation. Indeed, polyamines that bind the C terminus of α-syn were found to disrupt the intramolecular interaction in the α-syn monomer and promote fibrillation of α-syn (42, 43). With regard to Tau, NMR studies revealed that Tau is highly dynamic in solution, with an intricate network of transient long-range contacts (44, 45). Small-angle X-ray scattering analysis implied that the long-range contacts may be formed between the N- and C-termini of Tau (46). Disruption of the intramolecular contact network of Tau by serine/threonine phosphorylation can promote fibrillation of Tau (45, 47). In addition, previous studies have shown that polyanionic molecules (e.g. heparin, RNA), which bind to the microtubule-binding repeat domain of Tau by electrostatics interaction, may disrupt its intramolecular contact and promote Tau fibrillation (48, 49). Intriguingly, the C terminus of α-syn is highly enriched in negatively charged residues and, thus, may have a similar effect as that of polyanionic molecules to promote Tau fibrillation.

Notably, the PHF6 region, identified as the α-syn binding region in this study, can also be recognized by different chaperones (e.g. Hsp27, Hsp104, and Hsp40) (50–52). Fibrillation of Tau could be prevented by binding between PHF6 and chaperones, unlike that of α-syn. Therefore, despite a similar region being involved in Tau binding for α-syn and chaperones, detailed interaction patterns as well as other additional binding regions in Tau may be distinct, resulting in contradictory effects in modulation of Tau fibrillation. Accordingly, additional efforts will be needed to dissect the mechanisms underlying the distinct binding patterns for modulating Tau aggregation in different ways.

Under the pathological conditions of PD, α-syn tends to be highly phosphorylated at Ser129 (37, 38, 53). Our study further demonstrated that phosphorylation of α-syn at Ser129 dramatically enhanced its activity in inducing co-amyloid aggregation, whereas C-terminal truncated α-syn completely lost this activity. This may help to explain why Tau is prone to self-assemble and co-aggregate in some cases of Lewy body–associated diseases. In addition to Ser129, several other phosphorylation sites were identified within or adjacent to the binding interface of α-syn and K19, including Tyr125 and Tyr136 in α-syn and Ser320 in K19 (54, 55). Further research is warranted to clarify how such modifications, as well as familial disease–associated mutations (e.g. A30P and E46K of α-syn and P301L of Tau) alter the interplay between Tau and α-syn and consequently influence the synergistic effects of their co-aggregation.

Although we revealed that α-syn and Tau can interact in their monomeric forms and further co-aggregate into amyloid fibrils, the details of this interaction and the precise arrangement of the two proteins in the fibrillar form remain unclear. Several possible arrangements are possible. For instance, α-syn and Tau may form heteroprotofibrils and fibrils, similar to the fibril structure of the RIPK1–RIPK3 complex (56, 57). Alternatively, they may form homoprotofibrils on their own and further associate by lateral bundling of multiple protofibrils or connect to each other along the fibril-growing axis to form heterofibrils. Further structural studies of co-aggregated Tau and α-syn fibrils may help to address this question. Finally, based on our NMR titration experiments, we showed that Tau23 fibrils exhibit stronger activity in promoting α-syn fibrillation than the Tau23 monomer, although Tau23 fibrils cannot bind directly to the α-syn monomer. Thus, Tau23 fibrils may interfere with other species of α-syn, such as oligomers and protofilaments, or they might serve as a nucleus for inducing α-syn fibrillation, which needs to be further investigated.

Experimental procedures

Protein expression and purification

Human Tau23/K19 was expressed and purified as described previously (58). Briefly, Tau23/K19 was purified using a HighTrap HP SP (5 ml) column (GE Healthcare) followed by a Superdex 75 gel filtration column (GE Healthcare). For 15N-labeled proteins, protein expression was the same as that for unlabeled proteins except that the cells were grown in M9 minimal medium along with [15N]H4Cl (1 g liter−1). The purified proteins were concentrated and stored at −80 °C. The purity of the proteins was assessed by SDS-PAGE, and their concentrations were determined using a BCA assay (Thermo Fisher).

ThT fluorescence assay

ThT fluorescence assays were performed to monitor fibrillation of K19/Tau23 in the absence and presence of α-syn. The ThT assays were carried out in a 384-well plate (black with a flat optical bottom, Thermo Fisher Scientific, 142761), and fluorescence was measured using a Varioskan fluorescence plate reader (FLUOstar Omega).

Two different fibrillation buffers were used in the ThT assay: 25 mm Bis-Tris (pH 6.8) containing 1 mm MgCl2, 2 mm DTT, and 1 mm EDTA (preferred for Tau23/K19 fibrillation) (1) and 14 mm MES (pH 6.8), preferred for α-syn fibrillation (2). To monitor how α-syn and FUS-LC influence fibrillation of K19/Tau23, all ThT assays were performed in the fibrillation buffer (1) mentioned above. α-Syn was premixed with K19/Tau23 at molar ratios (K19:α-syn) of 1:0.5, 1:0.1, and 1:0.05 and (Tau:α-syn) of 1:1, 1:0.5, and 1:0.1. FUS-LC was premixed with K19 at molar ratios (K19:FUS-LC) of 1:0.5, 1:0.1, and 1:0.05. To monitor aggregation of α-syn in the absence and presence of K19/Tau23 and FUS-LC, all parameters were kept the same for the K19/Tau23 ThT assays except that fibrillation buffer (2) was used. K19/Tau23 was premixed with α-syn at molar ratios (α-syn:K19) of 1:0.1, 1:0.01, and 1:0.001. FUS-LC was premixed with α-syn at molar ratios (α-syn: FUS-LC) of 1:0.1, 1:0.01, and 1:0.001. The final concentration of ThT in the reaction mixtures was 50 μm. A total volume of 55 μl of premixed solution was added to each well. Samples were shaken at 600 rpm at 37 °C, and fluorescence was measured with excitation at 440 nm and emission at 485 nm. We ran three repetitions for each of the sample in the same plate and then calculated the average value with standard deviation from the triplicates of each samples to obtain the ThT curves represented in the figures. All samples shown in one figure were tested in the same 384-well plate to minimize systematic errors.

Negative staining EM

Each sample (5 μl) was deposited onto a glow-discharged holey carbon EM grid covered with a thin layer of carbon film (Beijing Zhongjingkeyi Technology Co. Ltd.) for 45 s, followed by washing twice with water (5 μl). The grid was then stained with 3% (w/v) uranyl acetate for 45 s for staining. An FEI Tecnai T12 electron microscope operating at an accelerating voltage of 120 kV was used to examine and visualize the samples. Images were collected by a Gatan US4000 4k × 4k charge couple device camera.

Analysis of supernatant and precipitate of K19 and α-syn aggregation by SDS-PAGE

Samples of K19 (200 μm), α-syn (20 μm), and K19 (200 μm) mixed with 20 μm α-syn were incubated for 80 h in fibrillation buffer (1). A control sample was taken from the premixed K19 (200 μm) and α-syn (20 μm) solution without further incubation. Samples of α-syn (200 μm), K19 (20 μm), and α-syn (200 μm) mixed with 20 μm K19 were incubated for 80 h in fibrillation buffer (2). A control sample was taken from the premixed α-syn (200 μm) and K19 (20 μm) solution without further incubation. The volume of each sample was 200 μl. All samples were centrifuged at 14,000 rpm for 1 h, followed by washing twice with 200 μl of incubation buffer. Urea (8 m, 5 μl) was added to each sample, and the samples were shaken at 600 rpm at room temperature overnight. Later, 20 μl of the samples was mixed with 5 μl of the gel loading dye (5×). After boiling for 10 min, 10 μl of each mixed sample was loaded and assessed using 15% SDS-PAGE gels.

Nickel-nitrilotriacetic acid–Nanogold labeling

Premixed His-tagged α-syn (200 μm) and K19 (20 μm) or His-tagged K19 (200 μm) with α-syn (20 μm) was incubated for 80 h in fibrillation buffer (2). Next, 5 μl of each sample was deposited onto a glow-discharged holey carbon EM grid covered with a thin layer of carbon film (Beijing Zhongjingkeyi Technology Co. Ltd.) for 45 s, followed by washing twice with water (5 μl). The grid was placed upside down on a droplet of 5 nm nickel-nitrilotriacetic acid–Nanogold (Nanoprobes, Yaphank, NY) solution (25 mm Na2HPO4 and 50 mm NaCl (pH 7.0)) and incubated for 6 min at room temperature. The grid was rinsed with a droplet of a buffer containing 50 mm Tris-HCl, 10 mm imidazole, 150 mm KCl, and 0.05% NaN3 for 2 min at room temperature. Subsequently, the grid was rinsed with water and stained with 10 μl of 3% (w/v) uranyl acetate for 45 s. Finally, it was dried and prepared for imaging using a Tecnai T12 microscope (FEI Co.) operated at 120 kV. Control grids were prepared using the same protocol but with premixed α-syn and K19 at the indicated concentrations.

Preparation of liposomes for NMR spectroscopy

The liposomes 1-palmitoyl-2-oleoyl-sn-glycero-3-phosphoethanolamine, 1,2-dioleoyl-sn-glycero-3-phospho-l-serine, and 1,2-dioleoyl-sn-glycero-3-phosphocholine (molar ratio of 5:3:2) (Avanti Polar Lipids Inc.) were prepared by mixing with chloroform and methanol (2:1 (v/v)) in a glass tube using an extrusion method (59, 60). The lipid mixture was evaporated under a stream of nitrogen gas and then dried thoroughly under a vacuum to yield a thin lipid film. Later, the dried thin film was rehydrated by adding an aqueous buffer (50 mm Na2HPO4 and 50 mm NaCl (pH 7.0)), subjected to vortex mixing, and shaken for 1 h at 300 rpm on an orbital shaker. Freeze–thaw cycles and sonication were carried out until the mixture become clear. The turbid liquid was extruded 19 times through a polycarbonate filter of 200-nm pore size (GE Healthcare) using a mini extruder (Avanti Polar Lipids) to form homogenous unilamellar vesicles.

MTSL labeling of α-syn

Nitroxide spin-labeled MTSL (Santa Cruz Biotechnology) was attached to the mutated cysteine residue in the α-syn variant (A124C) via a thiol-specific reaction. A124C–α-syn was first reduced in a buffer containing 50 mm Na2HPO4 (pH 7.0), 50 mm NaCl, and 0.05% NaN3 with 1 mm DTT, which were subsequently removed using a 5-ml desalting column (GE Healthcare) equilibrated in a buffer of 50 mm Na2HPO4 (pH 7.0), 50 mm NaCl, 8 m urea, and 0.05% NaN3. The proteins were then incubated with 1 mm MTSL (more than 10 times in excess) at room temperature for 1 h (protected from light), and excess MTSL was removed using a 5-ml desalting column (GE Healthcare) and equilibrated in a buffer containing 50 mm Na2HPO4 (pH 7.0), 50 mm NaCl, and 0.05% NaN3. The labeled proteins were then concentrated and stored at −80 °C.

NMR spectroscopy

All the NMR experiments were performed at 298 K on a Bruker 900 MHz or Agilent 800 MHz spectrometer with a cryogenic triple resonance inverse probe. Backbone resonance assignment of α-syn/K19 was accomplished according to previous publications (52, 61). For all NMR samples, the total volume was 500 μl with an NMR buffer containing 50 mm Na2HPO4, 50 mm NaCl, and 10% (v/v) D2O (pH 7.0). For α-syn/K19 titration assays, each titration sample contained 50 μm 15N-labeled α-syn/K19 in the absence and presence of 5-molar-fold unlabeled K19/α-syn diluted from high-concentration stocks. 15N-labeled α-syn (25 μm) was mixed with 20-molar-fold liposome as a control sample. A new sample was made with 25 μm 15N-labeled α-syn with 20-molar-fold liposome and 125 μm K19. As for the paramagnetic relaxation enhancement experiment, 15N-labeled K19 (50 μm) was first mixed with 50 μm MTSL–A124C–α-syn. After collecting the control spectrum, 1 mm sodium ascorbate (50 mm stock) was added to the sample. All 2D 1H-15N HSQC spectra were collected with 16 scans per transient and complex points of 2048 × 160. Chemical shift changes (Δδ) were calculated using the following equation: Δδ = SQRT ((Δδ1H)2 + (0.17 × Δδ15N)2), where Δδ1H and Δδ15N are the chemical shift differences of the amide proton and amide nitrogen between the free and bound state of the protein, respectively. All NMR spectra were analyzed and processed using NMRPipe (62) and NMRView (63).

Biolayer interferometry assay

The binding affinity between K19 and α-syn/α-syn S129D was measured by biolayer interferometry using ForteBio Octet RED96 (Pall ForteBio LLC). All data were collected at 25 °C in 96-well black flat-bottom plates (Greiner Bio-One) with orbital shaking at 1000 rpm. A total volume of 200 μl in an assay buffer containing 50 mm Na2HPO4 and 50 mm NaCl (pH 7.0) was used for each sample. Streptavidin biosensors were incubated in the assay buffer for 1 min, and then the biotinylated K19/Tau23 (20 μg ml−1) was loaded onto the surfaces of the biosensors (ForteBio) for 3 min, followed by washing using assay buffer for 1 min to remove unbound proteins. An autoinhibition step was used to eliminate nonspecific binding of K19/Tau23 to biosensors, in which 20 μm K19/Tau23 in assay buffer was incubated with biosensors for 6 min, followed by incubation in assay buffer for 2 min. Next, an association step was performed by incubating biosensors with different concentrations of α-syn or α-syn S129D, as indicated, for 6 min, followed by a disassociation step performed by incubation with the assay buffer for 6 min. All data were processed by data analysis software 9.0 (ForteBio).

Data availability

All data are contained within the manuscript and supplemental materials.

Author contributions

J. L., X. M., C. L., and D. L. conceptualization; J. L., X. M., C. J., Z. L., and C. H. data curation; J. L., S. Z., and X. M. formal analysis; S. Z., C. L., and D. L. investigation; S. Z. methodology; S. Z., C. L., and D. L. project administration; S. Z., C. L., and D. L. writing-review and editing; C. L. and D. L. supervision; C. L. and D. L. funding acquisition; C. L. and D. L. writing-original draft.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

We thank Dr. Zhijun Liu, Dr. Hongjuan Xue, and other staff members at the National Center for Protein Science Shanghai for assistance with NMR data collection and the staff members at the Large-Scale Protein Preparation System at the National Facility for Protein Science in Shanghai for providing technical support with biolayer interferometry data collection.

This work was supported by Major State Basic Research Development Program Grant 2016YFA0501902 (to C. L.), National Natural Science Foundation of China Grant 91853113 (to D. L. and C. L.), Science and Technology Commission of Shanghai Municipality Grant 18JC1420500 (to C. L.), Shanghai Pujiang Program Grant 18PJ1404300 (to D. L.), the “Eastern Scholar” project supported by the Shanghai Municipal Education Commission (to D. L.), Shanghai Municipal Science and Technology Major Project Grant 2019SHZDZX02 (to C. L.), and Innovation Program of Shanghai Municipal Education Commission Grant 2019-01-07-00-02-E00037 to D. L.). The authors declare that they have no conflicts of interest with the contents of this article.

This article contains Figs. S1–S13 and Tables S1–S3.

- α-syn

- α-synuclein

- PD

- Parkinson's disease

- AD

- Alzheimer's disease

- NAC

- non-amyloid component

- ThT

- thioflavin T

- NS

- negative staining

- FUS-LC

- fused in sarcoma low-complexity domain

- HSQC

- heteronuclear single-quantum coherence

- MTSL

- S-(1-oxyl-2,2,5,5-tetramethyl-2,5-dihydro-1H-pyrrol-3-yl) methyl methanesulfonothioate.

References

- 1. Chiti F., and Dobson C. M.. 2006) Protein misfolding, functional amyloid, and human disease. Annu. Rev. Biochem. 75, 333–366 10.1146/annurev.biochem.75.101304.123901 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Eisenberg D., and Jucker M.. 2012) The amyloid state of proteins in human diseases. Cell 148, 1188–1203 10.1016/j.cell.2012.02.022 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Crowther R. A., Daniel S. E., and Goedert M.. 2000) Characterisation of isolated α-synuclein filaments from substantia nigra of Parkinson's disease brain. Neurosci. Lett. 292, 128–130 10.1016/S0304-3940(00)01440-3 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Goedert M., Spillantini M. G., Del Tredici K., and Braak H.. 2013) 100 years of Lewy pathology. Nat. Rev. Neurol. 9, 13–24 10.1038/nrneurol.2012.242 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Wilcock G. K., and Esiri M. M.. 1982) Plaques, tangles and dementia. A quantitative study. J. Neurol. Sci. 56, 343–356 10.1016/0022-510X(82)90155-1 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Lee V. M., Goedert M., and Trojanowski J. Q.. 2001) Neurodegenerative tauopathies. Annu. Rev. Neurosci. 24, 1121–1159 10.1146/annurev.neuro.24.1.1121 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Hamilton R. L. 2000) Lewy bodies in Alzheimer's disease: a neuropathological review of 145 cases using α-synuclein immunohistochemistry. Brain Pathol. 10, 378–384 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Irwin D. J., Grossman M., Weintraub D., Hurtig H. I., Duda J. E., Xie S. X., Lee E. B., Van Deerlin V. M., Lopez O. L., Kofler J. K., Nelson P. T., Jicha G. A., Woltjer R., Quinn J. F., Kaye J., et al. (2017) Neuropathological and genetic correlates of survival and dementia onset in synucleinopathies: a retrospective analysis. Lancet Neurol. 16, 55–65 10.1016/S1474-4422(16)30291-5 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Hansen L., Salmon D., Galasko D., Masliah E., Katzman R., DeTeresa R., Thal L., Pay M. M., Hofstetter R., and Klauber M.. 1990) The Lewy body variant of Alzheimer's disease: a clinical and pathologic entity. Neurology 40, 1–8 10.1212/WNL.40.4_Suppl_1.1, 10.1212/WNL.40.1.1 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Irwin D. J., Lee V. M., and Trojanowski J. Q.. 2013) Parkinson's disease dementia: convergence of α-synuclein, tau and amyloid-β pathologies. Nat. Rev. Neurosci. 14, 626–636 10.1038/nrn3549 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Moussaud S., Jones D. R., Moussaud-Lamodière E. L., Delenclos M., Ross O. A., and McLean P. J.. 2014) α-Synuclein and tau: teammates in neurodegeneration? Mol. Neurodegener. 9, 43 10.1186/1750-1326-9-43 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Colom-Cadena M., Gelpi E., Charif S., Belbin O., Blesa R., Martí M. J., Clarimón J., and Lleó A.. 2013) Confluence of α-synuclein, tau, and β-amyloid pathologies in dementia with Lewy bodies. J. Neuropathol. Exp. Neurol. 72, 1203–1212 10.1097/NEN.0000000000000018 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Giasson B. I., Forman M. S., Higuchi M., Golbe L. I., Graves C. L., Kotzbauer P. T., Trojanowski J. Q., and Lee V. M.. 2003) Initiation and synergistic fibrillization of tau and α-synuclein. Science 300, 636–640 10.1126/science.1082324 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Guo J. L., Covell D. J., Daniels J. P., Iba M., Stieber A., Zhang B., Riddle D. M., Kwong L. K., Xu Y., Trojanowski J. Q., and Lee V. M.. 2013) Distinct α-synuclein strains differentially promote tau inclusions in neurons. Cell 154, 103–117 10.1016/j.cell.2013.05.057 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Singh B., Covelo A., Martell-Martínez H., Nanclares C., Sherman M. A., Okematti E., Meints J., Teravskis P. J., Gallardo C., Savonenko A. V., Benneyworth M. A., Lesné S. E., Liao D., Araque A., and Lee M. K.. 2019) Tau is required for progressive synaptic and memory deficits in a transgenic mouse model of α-synucleinopathy. Acta Neuropathol. 138, 551–574 10.1007/s00401-019-02032-w [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Espa E., Clemensson E. K. H., Luk K. C., Heuer A., Björklund T., and Cenci M. A.. 2019) Seeding of protein aggregation causes cognitive impairment in rat model of cortical synucleinopathy. Mov. Disord. 34, 1699–1710 10.1002/mds.27810 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Wang C., Zhao C., Li D., Tian Z., Lai Y., Diao J., and Liu C.. 2016) Versatile structures of α-synuclein. Front. Mol. Neurosci. 9, 48 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Burré J., Sharma M., Tsetsenis T., Buchman V., Etherton M. R., and Südhof T. C.. 2010) α-Synuclein promotes SNARE-complex assembly in vivo and in vitro. Science 329, 1663–1667 10.1126/science.1195227 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Diao J., Burré J., Vivona S., Cipriano D. J., Sharma M., Kyoung M., Südhof T. C., and Brunger A. T.. 2013) Native α-synuclein induces clustering of synaptic-vesicle mimics via binding to phospholipids and synaptobrevin-2/VAMP2. Elife 2, e00592 10.7554/eLife.00592 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Li Y., Zhao C., Luo F., Liu Z., Gui X., Luo Z., Zhang X., Li D., Liu C., and Li X.. 2018) Amyloid fibril structure of alpha-synuclein determined by cryo-electron microscopy. Cell Res. 28, 897–903 10.1038/s41422-018-0075-x [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Guerrero-Ferreira R., Taylor N. M., Mona D., Ringler P., Lauer M. E., Riek R., Britschgi M., and Stahlberg H.. 2018) Cryo-EM structure of α-synuclein fibrils. Elife 7, e36402 10.7554/eLife.36402 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Flagmeier P., Meisl G., Vendruscolo M., Knowles T. P., Dobson C. M., Buell A. K., and Galvagnion C.. 2016) Mutations associated with familial Parkinson's disease alter the initiation and amplification steps of α-synuclein aggregation. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 113, 10328–10333 10.1073/pnas.1604645113 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Hoyer W., Cherny D., Subramaniam V., and Jovin T. M.. 2004) Impact of the acidic C-terminal region comprising amino acids 109–140 on α-synuclein aggregation in vitro. Biochemistry 43, 16233–16242 10.1021/bi048453u [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Murray I. V., Giasson B. I., Quinn S. M., Koppaka V., Axelsen P. H., Ischiropoulos H., Trojanowski J. Q., and Lee V. M.. 2003) Role of α-synuclein carboxy-terminus on fibril formation in vitro. Biochemistry 42, 8530–8540 10.1021/bi027363r [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Levitan K., Chereau D., Cohen S. I., Knowles T. P., Dobson C. M., Fink A. L., Anderson J. P., Goldstein J. M., and Millhauser G. L.. 2011) Conserved C-terminal charge exerts a profound influence on the aggregation rate of α-synuclein. J. Mol. Biol. 411, 329–333 10.1016/j.jmb.2011.05.046 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Goedert M., Spillantini M. G., Jakes R., Rutherford D., and Crowther R. A.. 1989) Multiple isoforms of human microtubule-associated protein tau: sequences and localization in neurofibrillary tangles of Alzheimer's disease. Neuron 3, 519–526 10.1016/0896-6273(89)90210-9 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Gu G. J., Wu D., Lund H., Sunnemark D., Kvist A. J., Milner R., Eckersley S., Nilsson L. N., Agerman K., Landegren U., and Kamali-Moghaddam M.. 2013) Elevated MARK2-dependent phosphorylation of Tau in Alzheimer's disease. J. Alzheimers Dis. 33, 699–713 10.3233/JAD-2012-121357 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Drewes G., Ebneth A., Preuss U., Mandelkow E. M., and Mandelkow E.. 1997) MARK, a novel family of protein kinases that phosphorylate microtubule-associated proteins and trigger microtubule disruption. Cell 89, 297–308 10.1016/S0092-8674(00)80208-1 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Ando K., Oka M., Ohtake Y., Hayashishita M., Shimizu S., Hisanaga S., and Iijima K. M.. 2016) Tau phosphorylation at Alzheimer's disease-related Ser356 contributes to tau stabilization when PAR-1/MARK activity is elevated. Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 478, 929–934 10.1016/j.bbrc.2016.08.053 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Fitzpatrick A. W. P., Falcon B., He S., Murzin A. G., Murshudov G., Garringer H. J., Crowther R. A., Ghetti B., Goedert M., and Scheres S. H. W.. 2017) Cryo-EM structures of tau filaments from Alzheimer's disease. Nature 547, 185–190 10.1038/nature23002 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Arima K., Hirai S., Sunohara N., Aoto K., Izumiyama Y., Uéda K., Ikeda K., and Kawai M.. 1999) Cellular co-localization of phosphorylated tau- and NACP/α-synuclein-epitopes in Lewy bodies in sporadic Parkinson's disease and in dementia with Lewy bodies. Brain Res. 843, 53–61 10.1016/S0006-8993(99)01848-X [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Sengupta U., Guerrero-Muñoz M. J., Castillo-Carranza D. L., Lasagna-Reeves C. A., Gerson J. E., Paulucci-Holthauzen A. A., Krishnamurthy S., Farhed M., Jackson G. R., and Kayed R.. 2015) Pathological interface between oligomeric α-synuclein and tau in synucleinopathies. Biol. Psychiatry 78, 672–683 10.1016/j.biopsych.2014.12.019 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Dasari A. K. R., Kayed R., Wi S., and Lim K. H.. 2019) Tau interacts with the C-Terminal region of α-synuclein, promoting formation of toxic aggregates with distinct molecular conformations. Biochemistry 58, 2814–2821 10.1021/acs.biochem.9b00215 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Bhasne K., Sebastian S., Jain N., and Mukhopadhyay S.. 2018) Synergistic amyloid switch triggered by early heterotypic oligomerization of intrinsically disordered α-synuclein and tau. J. Mol. Biol. 430, 2508–2520 10.1016/j.jmb.2018.04.020 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. von Bergen M., Friedhoff P., Biernat J., Heberle J., Mandelkow E. M., and Mandelkow E.. 2000) Assembly of tau protein into Alzheimer paired helical filaments depends on a local sequence motif (306VQIVYK311) forming β structure. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 97, 5129–5134 10.1073/pnas.97.10.5129 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Murray D. T., Kato M., Lin Y., Thurber K. R., Hung I., McKnight S. L., and Tycko R.. 2017) Structure of FUS protein fibrils and its relevance to self-assembly and phase separation of low-complexity domains. Cell 171, 615–627.e616 10.1016/j.cell.2017.08.048 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. Anderson J. P., Walker D. E., Goldstein J. M., de Laat R., Banducci K., Caccavello R. J., Barbour R., Huang J., Kling K., Lee M., Diep L., Keim P. S., Shen X., Chataway T., Schlossmacher M. G., et al. (2006) Phosphorylation of Ser-129 is the dominant pathological modification of α-synuclein in familial and sporadic Lewy body disease. J. Biol. Chem. 281, 29739–29752 10.1074/jbc.M600933200 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38. Schmid A. W., Fauvet B., Moniatte M., and Lashuel H. A.. 2013) α-Synuclein post-translational modifications as potential biomarkers for Parkinson disease and other synucleinopathies. Mol. Cell. Proteomics 12, 3543–3558 10.1074/mcp.R113.032730 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39. Dedmon M. M., Lindorff-Larsen K., Christodoulou J., Vendruscolo M., and Dobson C. M.. 2005) Mapping long-range interactions in α-synuclein using spin-label NMR and ensemble molecular dynamics simulations. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 127, 476–477 10.1021/ja044834j [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40. Bertoncini C. W., Jung Y. S., Fernandez C. O., Hoyer W., Griesinger C., Jovin T. M., and Zweckstetter M.. 2005) Release of long-range tertiary interactions potentiates aggregation of natively unstructured α-synuclein. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 102, 1430–1435 10.1073/pnas.0407146102 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41. Theillet F. X., Binolfi A., Bekei B., Martorana A., Rose H. M., Stuiver M., Verzini S., Lorenz D., van Rossum M., Goldfarb D., and Selenko P.. 2016) Structural disorder of monomeric α-synuclein persists in mammalian cells. Nature 530, 45–50 10.1038/nature16531 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42. Fernández C. O., Hoyer W., Zweckstetter M., Jares-Erijman E. A., Subramaniam V., Griesinger C., and Jovin T. M.. 2004) NMR of α-synuclein-polyamine complexes elucidates the mechanism and kinetics of induced aggregation. EMBO J. 23, 2039–2046 10.1038/sj.emboj.7600211 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43. Antony T., Hoyer W., Cherny D., Heim G., Jovin T. M., and Subramaniam V.. 2003) Cellular polyamines promote the aggregation of α-synuclein. J. Biol. Chem. 278, 3235–3240 10.1074/jbc.M208249200 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44. Mukrasch M. D., Bibow S., Korukottu J., Jeganathan S., Biernat J., Griesinger C., Mandelkow E., and Zweckstetter M.. 2009) Structural polymorphism of 441-residue tau at single residue resolution. PLoS Biol. 7, e34 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45. Bibow S., Ozenne V., Biernat J., Blackledge M., Mandelkow E., and Zweckstetter M.. 2011) Structural impact of proline-directed pseudophosphorylation at AT8, AT100, and PHF1 epitopes on 441-residue tau. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 133, 15842–15845 10.1021/ja205836j [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46. Mylonas E., Hascher A., Bernadó P., Blackledge M., Mandelkow E., and Svergun D. I.. 2008) Domain conformation of tau protein studied by solution small-angle X-ray scattering. Biochemistry 47, 10345–10353 10.1021/bi800900d [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47. Jeganathan S., Hascher A., Chinnathambi S., Biernat J., Mandelkow E. M., and Mandelkow E.. 2008) Proline-directed pseudo-phosphorylation at AT8 and PHF1 epitopes induces a compaction of the paperclip folding of Tau and generates a pathological (MC-1) conformation. J. Biol. Chem. 283, 32066–32076 10.1074/jbc.M805300200 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48. Sibille N., Sillen A., Leroy A., Wieruszeski J. M., Mulloy B., Landrieu I., and Lippens G.. 2006) Structural impact of heparin binding to full-length Tau as studied by NMR spectroscopy. Biochemistry 45, 12560–12572 10.1021/bi060964o [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49. Kampers T., Friedhoff P., Biernat J., Mandelkow E. M., and Mandelkow E.. 1996) RNA stimulates aggregation of microtubule-associated protein tau into Alzheimer-like paired helical filaments. FEBS Lett. 399, 344–349 10.1016/S0014-5793(96)01386-5 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50. Mok S. A., Condello C., Freilich R., Gillies A., Arhar T., Oroz J., Kadavath H., Julien O., Assimon V. A., Rauch J. N., Dunyak B. M., Lee J., Tsai F. T. F., Wilson M. R., Zweckstetter M., et al. (2018) Mapping interactions with the chaperone network reveals factors that protect against tau aggregation. Nat. Struct. Mol. Biol. 25, 384–393 10.1038/s41594-018-0057-1 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51. Freilich R., Betegon M., Tse E., Mok S. A., Julien O., Agard D. A., Southworth D. R., Takeuchi K., and Gestwicki J. E.. 2018) Competing protein-protein interactions regulate binding of Hsp27 to its client protein tau. Nat. Commun. 9, 4563 10.1038/s41467-018-07012-4 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52. Zhang X., Zhang S., Zhang L., Lu J., Zhao C., Luo F., Li D., Li X., and Liu C.. 2019) Heat shock protein 104 (HSP104) chaperones soluble Tau via a mechanism distinct from its disaggregase activity. J. Biol. Chem. 294, 4956–4965 10.1074/jbc.RA118.005980 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53. Fujiwara H., Hasegawa M., Dohmae N., Kawashima A., Masliah E., Goldberg M. S., Shen J., Takio K., and Iwatsubo T.. 2002) α-Synuclein is phosphorylated in synucleinopathy lesions. Nat. Cell. Biol. 4, 160–164 10.1038/ncb748 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54. Ma M. R., Hu Z. W., Zhao Y. F., Chen Y. X., and Li Y. M.. 2016) Phosphorylation induces distinct α-synuclein strain formation. Sci. Rep. 6, 37130 10.1038/srep37130 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55. Strang K. H., Sorrentino Z. A., Riffe C. J., Gorion K. M., Vijayaraghavan N., Golde T. E., and Giasson B. I.. 2019) Phosphorylation of serine 305 in tau inhibits aggregation. Neurosci. Lett. 692, 187–192 10.1016/j.neulet.2018.11.011 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56. Mompeán M., Li W., Li J., Laage S., Siemer A. B., Bozkurt G., Wu H., and McDermott A. E.. 2018) The structure of the necrosome RIPK1-RIPK3 core, a human hetero-amyloid signaling complex. Cell 173, 1244–1253.e10 10.1016/j.cell.2018.03.032 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57. Li D., and Liu C.. 2018) Better together: a hybrid amyloid signals necroptosis. Cell 173, 1068–1070 10.1016/j.cell.2018.04.030 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58. Barghorn S., Biernat J., and Mandelkow E.. 2005) Purification of recombinant tau protein and preparation of Alzheimer-paired helical filaments in vitro. Methods Mol. Biol. 299, 35–51 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59. Fusco G., De Simone A., Gopinath T., Vostrikov V., Vendruscolo M., Dobson C. M., and Veglia G.. 2014) Direct observation of the three regions in α-synuclein that determine its membrane-bound behaviour. Nat. Commun. 5, 3827 10.1038/ncomms4827 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60. Ma D. F., Xu C. H., Hou W. Q., Zhao C. Y., Ma J. B., Huang X. Y., Jia Q., Ma L., Diao J., Liu C., Li M., and Lu Y.. 2019) Detecting single-molecule dynamics on lipid membranes with quenchers-in-a-liposome FRET. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. Engl. 58, 5577–5581 10.1002/anie.201813888 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61. Liu Z., Wang C., Li Y., Zhao C., Li T., Li D., Zhang S., and Liu C.. 2018) Mechanistic insights into the switch of αB-crystallin chaperone activity and self-multimerization. J. Biol. Chem. 293, 14880–14890 10.1074/jbc.RA118.004034 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62. Delaglio F., Grzesiek S., Vuister G. W., Zhu G., Pfeifer J., and Bax A.. 1995) NMRPipe: a multidimensional spectral processing system based on UNIX pipes. J. Biomol. NMR 6, 277–293 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63. Johnson B. A. 2004) Using NMRView to visualize and analyze the NMR spectra of macromolecules. Methods Mol. Biol. 278, 313–352 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Data Availability Statement

All data are contained within the manuscript and supplemental materials.