Sir,

A 40-year-old male from Balia presented with multiple hypopigmented skin lesions and few elevated red lesions on face, trunk and axilla for last 4 years and 1 year, respectively. There was no past history of any major illness or long-standing fever.

Examination revealed multiple well to ill-defined erythematous plaques ranging from 3-4 cm to 8-10 cm with overlying yellowish-brown thick crust, on face, bilateral axillae, and trunk. At some places, crust had fallen off, revealing irregular ulcers and oozing sero-sanguineous discharge [Figure 1a and b]. Multiple variable sized, irregular, infiltrated, hypopigmented plaques, ranging in size from 1-2 cm to 3-4 cm were present on trunk and bilateral extremities [Figure 2]. Mucosal involvement was absent. Sensory and motor examination revealed no contributory findings. No peripheral nerve thickening, hepato-splenomegaly, or significant lymphadenopathy was noted.

Figure 1.

(a) Clinical photograph showing crusted ulcerative plaques on face and (b) well-defined crusted plaque on abdomen

Figure 2.

Numerous hypopigmented infiltrated plaques on back

Investigations: Chest radiograph, abdominal ultrasound, hematological, and biochemical examinations were non-contributory. Immunological test for leishmaniasis (antibodies against recombinant K39 antigen) was found to be reactive. Slit-skin smears from the plaques revealed Leishman Donovan (LD) bodies on Giemsa staining.

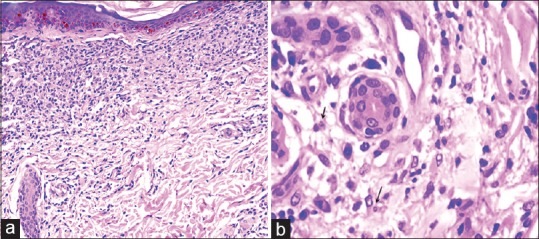

Skin biopsy from the hypopigmented plaque on abdomen showed a broad band-like infiltrate in papillary dermis, mainly composed of histiocytes admixed with lympho-plasmacytic cells. Thin grenz zone was also seen. Biopsy from the crusted plaque on abdomen showed dense diffuse interstitial as well as perivascular and periadnexal infiltrate in dermis with ill-defined granulomas and few intracytoplasmic bodies suggestive of Leishman donovan (LD) bodies [Figure 3a and b]. Wade Fite and PAS stains were negative for acid-fast bacilli and fungal elements, respectively. Polymerase chain reaction (PCR) could not be done due to lack of availability at our centre.

Figure 3.

(a) Section shows skin with a band-like infiltrate of lymphocytes and histiocytes. Hematoxylin and Eosin, ×200. (b) dermal infiltrate of lymphocytes and histiocytes along with few intracellular LD bodies (arrows). Hematoxylin and Eosin, ×400

A diagnosis of post kala-azar dermal leishmaniasis (PKDL) was made on the basis of above clinical, histological, and immunological findings. The patient was treated with tablet miltefosine 50 mg twice-a-day for 3 months, resulting in marked improvement of cutaneous lesions at 6 months follow-up [Figures 4 and 5].

Figure 4.

Resolution of cutaneous lesions on face, 6 months post treatment

Figure 5.

Resolution of cutaneous lesions on trunk, 6 months post treatment

Leishmaniasis can be categorized into, cutaneous leishmaniasis (CL); mucocutaneous leishmaniasis (MCL) and visceral leishmaniasis (VL). PKDL is a complication of VL and is characterized by a macular, maculopapular and nodular rash in a patient who has recovered from VL and who is otherwise well. It is mainly seen in Sudan and India where it follows treated VL in 50% and 5–10% of cases, respectively.[1] Interestingly, in 15–20% of cases there is no previous history of visceral leishmaniasis in India.[2] Clinical presentation depends on the geographical region of residence. Indian PKDL can have polymorphic presentations, varying from erythematous indurated lesions on the butterfly area of face, multiple symmetrical hypopigmented macules to a combination of papules, nodules, and plaques.[1]

Our patient had no history of previous VL but such history may not be present in 15–20% of these cases. This patient was diagnosed as a case of PKDL as he hailed from Balia (Eastern part of Uttar Pradesh), one of the known endemic region of VL in India. The diagnosis was further clinched by presence of numerous hypopigmented lesions which are typical of PKDL.[3]

PKDL is differentiated from leprosy by absence of sensory loss, motor weakness, nerve enlargement, and negative slit-skin smear examination for acid-fast bacilli. Ulceration and crusting is quite rare in cases of PKDL. Atypical presentations like ulcerative,[4,5,6] annular, warty, papillomatous, fibroid, or xanthomatous type have been reported previously in few case reports.[1] To summarize, crusted ulcerative-plaque like lesions are quite rare in PKDL. A high index of suspicion is required to diagnose such kind of atypical presentation, especially when treating a patient hailing from an endemic area or a history of recent travel to an endemic area of VL.

Declaration of patient consent

The authors certify that they have obtained all appropriate patient consent forms. In the form the patient(s) has/have given his/her/their consent for his/her/their images and other clinical information to be reported in the journal. The patients understand that their names and initials will not be published and due efforts will be made to conceal their identity, but anonymity cannot be guaranteed.

Financial support and sponsorship

Nil.

Conflicts of interest

There are no conflicts of interest.

Acknowledgements

We are thankful to Dr. Meenakshi Batrani, consultant dermatopathologist, Delhi dermpath laboratory, Delhi and Dr. Kiranpreet Malhotra, Department of Pathology, Dr. RML Institute of Medical Sciences, Lucknow for their valuable inputs in the histopathological examination of the patient.

References

- 1.Zijlstra EE, Musa AM, Khalil EA, el-Hassan IM, el-Hassan AM. Post kala-azar dermal leishmaniasis. Lancet Infect Dis. 2003;3:87–98. doi: 10.1016/s1473-3099(03)00517-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Salotra P, Singh R. Challenges in the diagnosis of post kala-azar dermal leishmaniasis. Indian J Med Res. 2006;123:295–310. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Chaudhary RG, Bilimoria FE, Katare SK. Diffuse cutaneous leishmaniasis: Co-infection with human immunodeficiency virus (HIV) Indian J Dermatol Venereol Leprol. 2008;74:641–3. doi: 10.4103/0378-6323.45111. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Chakrabarti A, Kumar B, Das A, Mahajan VK. Atypical post-kala-azar dermal leishmaniasis resembling histoid leprosy. Lepr Rev. 1997;68:247–51. doi: 10.5935/0305-7518.19970034. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Sethuraman G, Bhari N, Salotra P, Ramesh V. Indian erythrodermic postkala-azar dermal leishmaniasis. BMJ Case Rep. 2017;2017 doi: 10.1136/bcr-2016-217926. pii: bcr2016217926 doi: 101136/bcr-2016-217926. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Nandy A, Addy M, Banerjee D, Guha SK, Maji AK, Saha AM. Laryngeal involvement during post kala-azar dermal leishmaniasis in India. Trop Med Int Health. 1997;2:371–3. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-3156.1997.tb00153.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]