Abstract

Coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) pneumonia, firstly reported in Wuhan, Hubei province, China, has rapidly spread around the world with high mortality rate among critically ill patients. The use of corticosteroids in COVID-19 remains a major controversy. Available evidences are inconclusive. According to WHO guidance, corticosteroids are not recommended to be used unless for another reason. Chinese Thoracic Society (CTS) proposes an expert consensus statement that suggests taking a prudent attitude of corticosteroid usage. In our clinical practice, we do not use corticosteroids routinely; only low-to-moderate doses of corticosteroids were given to several severely ill patients prudently. In this paper, we will present two confirmed severe COVID-19 cases admitted to isolation wards in Optical Valley Campus of Tongji hospital, Tongji Medical College, Huazhong University of Science and Technology. We will discuss questions related to corticosteroids usages.

Keywords: Corticosteroids, COVID-19, HRCT, Severe COVID-19 pneumonia

Introduction

The use of corticosteroids in coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) pneumonia remains a major controversy. According to WHO guidance, corticosteroids are not recommended to be used routinely for patients with severe acute respiratory infection when 2019-nCoV infection is suspected, unless indicated for another reason [1]. In spite of this, from the point of urgently clinical demand, Chinese Thoracic Society (CTS) proposed an expert consensus statement that suggests taking a prudent attitude of corticosteroids usage [2]. The following criteria should be considered [3]: (1) the benefits and harms should be carefully weighed before using corticosteroids; (2) corticosteroids should be used prudently on critically ill patients; (3) for patients with hypoxemia due to underlying diseases or who use corticosteroids for chronic diseases on a regular basis, further use of corticosteroids should be cautious; (4) the dosage should be low to moderate (≤ 0·5–1 mg/kg per day methylprednisolone or equivalent) and the duration should be short (≤ 7 days).

In clinical practices, several questions still exist. For example, who is most likely to benefit from corticosteroid usages? When should we consider to take corticosteroids intervene? Which dosages or durations are appropriate? As a front-line physician, I worked for about 2 months in Optical Valley Campus of Tongji hospital, Tongji Medical College, Huazhong University of Science and Technology. My colleagues and I did not use corticosteroids routinely. A total of 92 patients with severe COVID-19 pneumonia were treated in our ward. Among them, low-to-moderate doses of corticosteroids were only given to seven patients prudently at different stages in the disease course. Most of them showed favorable response to corticosteroid treatment with improvement of clinical syndromes and HRCT findings. In the following sections, we present two representative confirmed severe COVID-19 cases according to WHO interim guidance [1] who have received corticosteroid treatment during their hospitalization. Relevant questions about corticosteroid usages are also discussed.

Case description

The two patients are residents of Wuhan City and both had exposure to patients with confirmed severe COVID-19.

Case 1

A 41-year-old man with no smoking history was admitted on February 11, and the duration from onset of syndromes to admission was 5 days. He was from a family clustering of COVID-19 and his parents and grandmother died from COVID-19. He presented dyspnea and fever with maximum body temperature of 40.0 °C. He reported poor appetite without diarrhea and had chronic sinusitis.

Laboratory tests results and treatment information are demonstrated in Tables 1 and 2. The patient had leukocytopenia with lymphocytopenia and had an increased C-reaction protein (CRP) and interleukin (IL)-6. He received antiviral treatment including arbidol, hydroxychloroquine, and ribavirin. Wide-spectrum antibiotics (moxifloxacin and imipenem) were used to prevent secondary infections. Other therapies included relieve coughing and phlegm, immunomodulatory, antioxidant, and nutritional support. At admission, he required high-flow oxygen therapy (flow rate 10 L/Min) through a face mask, and his pulse oxygen saturation was 90%. He did not receive mechanic ventilation or noninvasive ventilation during hospitalization.

Table 1.

Demographics, clinical characteristics, and treatment of the two patients with severe COVID-19 pneumonia on admission to hospital

| Patient 1 | Patient 2 | |

|---|---|---|

| Sex, F/M | M | M |

| Age, years | 41 | 73 |

| Smoking history | None | None |

| Basic disease | Chronic sinusitis | None |

| Date at onset of symptoms | 2020 Feb 06 | 2020 Jan 28 |

| Admission date | 2020 Feb 11 |

2020 Feb 08 (admitted to other hospital) 2020 Feb 23 (transferred to our hospital) |

| Days from onset to admission, days | 5 | 10 |

| Days from onset to using corticosteroid, days | 9 | 26 |

| Length of hospital stay, days | 46 | Still in hospital |

| Highest temperature, °C | 40.0 | 40.0 |

| Presented symptoms | ||

| Fever | + | + |

| Cough | – | + |

| Dyspnea | + | + |

| Diarrhea | – | – |

| Poor appetite | + | + |

| Therapy | ||

| Antiviral therapy | Arbidol, hydroxychloroquine, ribavirin | Hydroxychloroquine, ribavirin |

| Antibiotic therapy | Moxifloxacin, imipenem | Meropenem |

| Antioxidant therapy | Acetylcysteine | Acetylcysteine |

| Anticoagulant therapy | None | Low molecular weight heparin, rivaroxaban |

| Nutrition support | Nutrison, enteral nutritional suspension (TP-MCT) | Nutrison |

| Immunoregulator | Gamma globulin, thymopentin | Gamma globulin, thymopentin |

| Use of corticosteroid | Methylprednisolone 40 mg qd for 4 days | Methylprednisolone 40 mg bid for 5 days, then 40 mg qd for 3 days, then 16 mg qd for 4 days, 12 mg qd for 4 days, 8 mg qd for 9 days |

Table. 2.

Laboratory findings of the two patients with severe COVID-19 pneumonia on admission to hospital

| Patient 1 | Patient 2 | |

|---|---|---|

| Blood routine | ||

| White blood cell count (*109/L, 3.5~9.5) | 3.01 | 12.13 |

| Neutrophils (*109/L, 1.8~6.3) | 1.52 | 10.61 |

| Neutrophils percent (%, 40.0~75.0) | 50.5 | 87.3 |

| Lymphocytes (*109/L, 1.1~3.2) | 1.05 | 0.67 |

| Lymphocytes percent (%, 20.0~50.0) | 34.9 | 5.5 |

| Blood biochemistry | ||

| Alanine aminotransferase (U/L, ≤ 41) | 18 | 12 |

| Aspartate aminotransferase (U/L, ≤ 40) | 41 | 12 |

| Creatinine (μmol/L, 59~104) | 67 | 51 |

| Urea (mmol/L, 3.6~9.5) | 4.20 | 4.10 |

| Lactate dehydrogenase (U/L, 135~225) | 297 | 317 |

| Albumin (g/L, 35~52) | 37.4 | 39.6 |

| Globulin (g/L, 20~35) | 24.6 | 32.5 |

| Infection-related biomarkers | ||

| Procalcitonin (ng/mL, 0.02~0.05) | 0.08 | 0.10 |

| C-reactive protein (mg/L, < 1 mg/L) | ||

| Prior to prednisolone 40 mg bid | 7.9 | 139.3 |

| 2nd day after treatment | 54.1 | – |

| 4th day after treatment | 3 | 8 |

| TNF-α (pg/ml, < 8.1) | 5.8 | 9.1 |

| Interleukin-1β (pg/ml, < 5.0) | < 5.0 | 51.0 |

| Interleukin-6 (pg/ml, < 7.0) | ||

| Prior to prednisolone 40 mg bid | 66.23 | 139.00 |

| After treatment | 3.18 (Day 22) | 3.39 (Day 20) |

| Coagulation function | ||

| D-dimer (μg/ml FEU, < 0.5) | 0.22 | 2.65 |

| Prothrombin time (s, 11.5~14.5) | 13.3 | 14.6 |

| Activated partial thromboplastin time (s, 29.0~42.0) | 45.2 | 39.0 |

| AMI indexes | ||

| Creatine kinase, MB Form (ng/mL, ≤ 7.2) | 1.1 | 1.2 |

| Cardiac troponin I (pg/mL, ≤ 34.2) | 4.5 | 4.0 |

| Myoglobin (ng/mL, ≤ 154.9) | 95.9 | 23.4 |

| N-terminal pro-B-type natriuretic peptide (pg/mL, < 241) | 849 | 414 |

| Partial pressure of oxygen (mmHg, 80~100) | 79.0 | 78.8 |

| Oxygen saturation (%, 95~99) | 93 (10 L/min) | 96 (10 L/min) |

| Confirmed date by real-time RT-PCR | 2020 Feb 11 | 2020 Feb 07 |

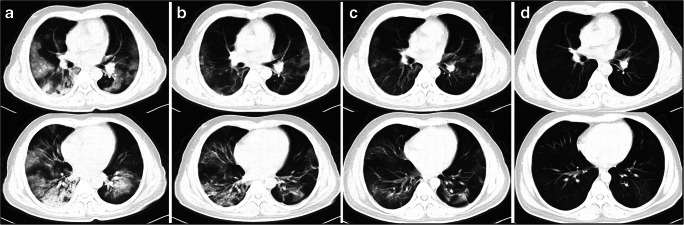

The first day after his admission, the fever persisted, and dry cough and dyspnea worsened. Chest high-resolution computed scan (HRCT) was performed and showed a rapid progression of diffuse ground-glass opacities (GGO) and consolidations compared to those performed before admission. Methylprednisolone (40 mg twice daily, intravenously) was administered for 4 days and then discontinued. After corticosteroids were given, his body temperature decreased to normal and the syndromes improved. HRCT showed obvious absorption of GGO and consolidations (Fig. 1). By March 26, 2020, he was discharged.

Fig. 1.

Serial HRCT findings in patient 1. a At admission (2020 Feb 16), chest high-resolution computed scan (HRCT) showed bilateral diffused ground-glass opacities (GGO) and consolidation. b After using corticosteroids for 3 days (2020 Feb 19), HRCT showed an obvious absorption of GGO and consolidations. c Eight days after using corticosteroids (2020 Feb 24), HRCT showed a further improved status. d One month later (2020 Mar 17), HRCT showed the abnormalities were absorbed mostly with a little GGO left in the left lower lung

Case 2

A 73-year-old man with no smoking history was admitted to another hospital on February 8, 2020 and the duration from onset of syndromes to admission was 10 days. He stayed in that hospital for 15 days with persistent fever and worsening dyspnea, then transferred to our hospital on February 23, 2020. He also presented dyspnea, dry cough, and fever with maximum body temperature of 40.0 °C. He reported poor appetite without diarrhea and denied having any chronic diseases.

The patient had an increased count of white blood cell, an increased CRP, and an elevated D-Dimer. The concentrations of tumor necrosis factor (TNF)-α, IL-1β, and IL-6 were elevated. The antiviral treatments he received were similar to case 1 except for arbidol. Meropenem was used to prevent secondary infections. At admission, he required high-flow oxygen therapy and his pulse oxygen saturation was 95%.

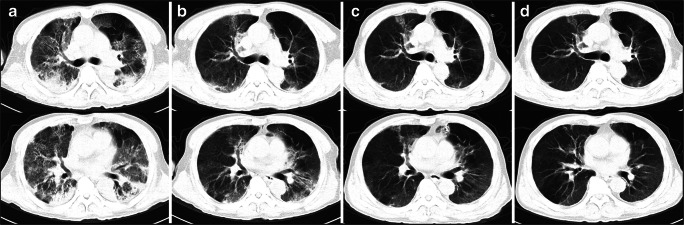

The fever persisted, and dry cough and dyspnea worsened on the first day after his admission. HRCT was performed, showing diffused GGO and a subpleural consolidation with air trapped in the left upper lung. The initial dosage of methylprednisolone was 40 mg twice daily for 3 days, then tapered to 40 mg per day for 3 days; after that, oral dosage was maintained 8~16 mg per day for 14–17 days and discontinued. After giving him corticosteroids, the syndromes improved and HRCT showed an improved status (Fig. 2). By March 29, 2020, he was still hospitalized.

Fig. 2.

Serial HRCT findings in patient 2. a The 3rd day from admission (2020 Feb 23), chest high-resolution computed scan (HRCT) showed diffused ground-glass opacities (GGO) and a subpleural consolidation, and air trapping in the left upper lung. b After using corticosteroids for 6 days (2020-02-29), HRCT showed an obvious absorption of consolidation with mild diffused GGO and a little consolidation with subpleural distribution. c Fourteen days later (2020 Mar 08), HRCT showed patchy consolidation in the upper lung and the left upper lung. d Twenty-four days later (2020 Mar 17), HRCT showed mild diffused mild GGO and air trapping in the left upper lung and right lower lung

Review and discussion

The treatment of COVID-19 is a great challenge for clinicians and no pharmacological therapy has been proven effective yet. The mainstay of treatment is supportive care. Clark Russell and his colleagues [4] summarized the available clinical evidence on corticosteroid therapy in severe COVID-19 [5], Middle East respiratory syndrome (MERS) [6] and influenza [7] against corticosteroid use in 2019 novel coronavirus pneumonia, except in the setting of a clinical trial. The main potential risks associated with corticosteroids usage include secondary infections, long-term complications, and delayed virus clearance. In addition, the administration of corticosteroids did not show an advantage to decrease mortality [7], plus, patients receiving corticosteroids were more likely to require mechanical ventilation, vasopressors, renal replacement therapy and stay in intensive care unit (ICU) longer [6].

On the other hand, several studies supported the use of corticosteroids at low-to-moderate doses in patients with virus infection. Reports showed that the proper use of corticosteroids could reduce the mortality of critically ill SARS patients and shorten their hospital stay without causing secondary infections and other complications [8]. Furthermore, low-to-moderate doses of corticosteroids were also associated with reduced mortality in patients with influenza A (H1N1) viral pneumonia when oxygen index was lower than 300 mmHg [9]. Recently, Song et al. reported that methylprednisolone treatment might be beneficial for patients with COVID-19 who developed acute respiratory distress syndrome (ARDS) [10].

The clinical course of COVID-19 is not to be fully characterized. Zhang et al. [11] reported that about 17% of patients with severe illness may quickly progress to ARDS. Among them, 11% of patients worsened in 1~2 weeks and died of multiple organ failure. In our cases, patient 1 was admitted on the fifth day from onset. The disease course and chest HRCT abnormalities progressed rapidly. A study reported that the pathological findings of COVID-19 were interstitial mononuclear inflammatory infiltrating, pulmonary edema, and hyaline membrane formation, suggesting early phase of ARDS. So, timely and appropriate use of corticosteroids could be considered to attenuate cytokine-related lung injury and prevent ARDS development [12]. For patient 2, when he was transferred to our hospital, the clinical course was exceeding 20 days and HRCT showed a prominent consolidation with bilateral involvement. The clinical characteristics, disease course, and radiological findings demonstrated a subacute process, resembling secondary organizing pneumonia (SOP) [13]. The total durance of corticosteroids was 25 days and he showed a favorable response to corticosteroid treatment. However, is the treatment durance appropriate? Do such “organizing pneumonia”-like abnormalities in HRCT progress or relapse after corticosteroids discontinued? What extent or degree will the interstitial abnormalities be left in the lung? How long will it take for lung functions to recover? All these clinical questions remain our concerns. A long-term follow up is indeed needed to monitor the serial pulmonary functions and HRCT appearances.

Cytokine release syndrome (CRS) contributing to multiorgan dysfunctions has been widely discussed in the pathogenesis of COVID-19 for the plasma levels of proinflammatory cytokines, particularly IL-6, IL-1β, and TNF-α, were markedly increased in ICU patients [14]. Pathogenic T cells and inflammatory monocytes released a considerable amount of interleukin 6, which was associated with the severity and outcome of the disease and was therefore believed to play a major role in inciting the cytokine storm [15, 16]. Xu and his colleagues reported 21 cases diagnosed as severe or critical COVID-19 that were treated effectively with tocilizumab, IL-6 receptor antagonist. After being given tocilizumab, the clinical manifestations, HRCT abnormalities, and laboratory examinations remarkably improved and most of the patients were discharged within 2 weeks with no notable adverse reactions observed [17]. Although the evidence came from a single center and the sample size was small, targeting inflammatory signaling pathway is a potential consideration in the treatment of COVID-19 [18]. However, Radbel J et al. reported two patients progressed to secondary hemophagocytic lymphohistiocytosis (sHLH) despite tocilizumab usage and one developed viral myocarditis [19]. Further randomized controlled trials are still needed to confirm the efficacy and safety and to select patients who could benefit from the treatment of cytokine inhibitors the most.

The mortality rate of critically ill patients with COVID-19 is high, reported beyond 60% [20]. To reduce the mortality rate, an early warning model must be established to identify severe individuals who are at risk of becoming critically ill. As mentioned in previous studies, older age, a history of cerebrovascular disease, and ARDS were associated with increased risk of death [11, 20, 21]. Sequential Organ Failure Assessment (SOFA) score was associated with death of COVID-19, highlighting the significance of supportive care of organ functions [10, 22]. Lymphocytopenia was also common in critically ill patients with viral infection [23, 24], and careful monitoring of lab examinations is necessary. Other reported biomarkers including PD-1, CTLA4, TIGIT, IFN-γ, and IL-2, which were associated with functional T-cells, were demonstrated to predict progression of COVID-19 [25]. In addition, because fever was not detected during the onset of some patients [26], early or repeated radiological examinations are most important for screening patients with COVID-19 and evaluating disease progression.

Conclusion

In conclusion, although the controversy in corticosteroid treatment of COVID-19 is heated and existing evidence is inconclusive, arbitrary forbiddance and general recommendation is not advisable. In accordance with CTS expert consensus [2], we suggest the use of low-to-moderate dose of corticosteroids for short courses with caution. Personalized strategy should be rational, and the decision of initiating corticosteroid treatment should be based on the judgment of clinical courses, lab findings, radiological appearances, and, if available, pathological examinations. In addition, it is necessary to detect the associated complications and reexamine chest HRCT in short intervals (within 1 week) to assess treatment response. A well-designed random controlled study which stratifies patients with disease severity is still needed to treat the disease efficaciously.

Acknowledgments

We thank all colleagues at Optical Valley Campus of Tongji hospital, Tongji Medical College, Huazhong University of Science & Technology.

Authors’ contributions

Jinghong Dai, Yajun Qian, and Hui Li were the patient’s internal medicine physicians. Jinghong Dai wrote the initial draft, did the review of the literature, and edited the manuscript. Jian Tang, Ying Xu, and Qingqing Xu reviewed and edited the manuscript. Yajun Qian and Yali Xiong collected the clinical and HRCT data and edited the manuscript.

Funding information

The study was supported by the National Natural Science Foundation of China (81570058), Jiangsu Provincial Medical Talent (ZDRCA2016058), Jiangsu Social Development Project (BE2017604), and the Fundamental Research Funds for the Central Universities (14380460).

Compliance with ethical standards

Disclosures

None.

Footnotes

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

References

- 1.World Health Organization (2020) Clinical management of severe acute respiratory infection when novel coronavirus (nCoV) infection is suspected: interim guidance. https://apps.who.int/iris/handle/10665/330893. Accessed 28 Jan 2020

- 2.Zhao JP, Hu Y, Du RH, Chen ZS, Jin Y, Zhou M, Zhang J, Qu JM, Cao B. Expert consensus on the use of corticosteroid in patients with 2019-nCoV pneumonia. Zhonghua Jie He He Hu Xi Za Zhi. 2020;43(3):183–184. doi: 10.3760/cma.j.issn.1001-0939.2020.03.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Shang L, Zhao J, Hu Y, Du R, Cao B. On the use of corticosteroids for 2019-nCoV pneumonia. Lancet. 2020;395(10225):683–684. doi: 10.1016/s0140-6736(20)30361-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Russell CD, Millar JE, Baillie JK. Clinical evidence does not support corticosteroid treatment for 2019-nCoV lung injury. Lancet. 2020;395(10223):473–475. doi: 10.1016/s0140-6736(20)30317-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Stockman LJ, Bellamy R, Garner P. SARS: systematic review of treatment effects. PLoS Med. 2006;3(9):e343. doi: 10.1371/journal.pmed.0030343. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Arabi YA-O, Mandourah Y, Al-Hameed F, Sindi AA, Almekhlafi GA, Hussein MA, Jose J, Pinto R, Al-Omari A, Kharaba A, Almotairi A, Al Khatib K, Alraddadi B, Shalhoub S, Abdulmomen A, Qushmaq I, Mady A, Solaiman O, Al-Aithan AM, Al-Raddadi R, Ragab A, Balkhy HH, Al Harthy A, Deeb AM, Al Mutairi H, Al-Dawood A, Merson L, Hayden FG, Fowler RA. Corticosteroid therapy for critically ill patients with Middle East respiratory syndrome. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2018;196(6):757–767. doi: 10.1164/rccm.201706-1172OC. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Ni YN, Chen G, Sun J, Liang BM, Liang ZA. The effect of corticosteroids on mortality of patients with influenza pneumonia: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Crit Care. 2019;23(1):99. doi: 10.1186/s13054-019-2395-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Chen RC, Tang XP, Tan SY, Liang BL, Wan ZY, Fang JQ, Zhong N. Treatment of severe acute respiratory syndrome with glucosteroids: the Guangzhou experience. Chest. 2006;129(6):1441–1452. doi: 10.1378/chest.129.6.1441. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Li H, Yang SG, Gu L, Zhang Y, Yan XX, Liang ZA, Zhang W, Jia HY, Chen W, Liu M, Yu KJ, Xue CX, Hu K, Zou Q, Li LJ, Cao B, Wang C, National Influenza Apdm09 Clinical Investigation Group of C Effect of low-to-moderate-dose corticosteroids on mortality of hospitalized adolescents and adults with influenza A(H1N1)pdm09 viral pneumonia. Influenza Other Respir Viruses. 2017;11(4):345–354. doi: 10.1111/irv.12456. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Wu C, Chen X, Cai Y, Ja X, Zhou X, Xu S, Huang H, Zhang L, Zhou X, Du C, Zhang Y, Song J, Wang S, Chao Y, Yang Z, Xu J, Zhou X, Chen D, Xiong W, Xu L, Zhou F, Jiang J, Bai C, Zheng J, Song Y (2020) Risk factors associated with acute respiratory distress syndrome and death in patients with coronavirus disease 2019 pneumonia in Wuhan, China. JAMA Int Med. 10.1001/jamainternmed.2020.0994 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 11.Chen N, Zhou M, Dong X, Qu J, Gong F, Han Y, Qiu Y, Wang J, Liu Y, Wei Y, Xia Ja YT, Zhang X, Zhang L. Epidemiological and clinical characteristics of 99 cases of 2019 novel coronavirus pneumonia in Wuhan, China: a descriptive study. Lancet. 2020;395(10223):507–513. doi: 10.1016/s0140-6736(20)30211-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Xu Z, Shi L, Wang Y, Zhang J, Huang L, Zhang C, Liu S, Zhao P, Liu H, Zhu L, Tai Y, Bai C, Gao T, Song J, Xia P, Dong J, Zhao J, Wang FS. Pathological findings of COVID-19 associated with acute respiratory distress syndrome. Lancet Respir Med. 2020;8:420–422. doi: 10.1016/S2213-2600(20)30076-X. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Li HC, Ma J, Zhang H, Cheng Y, Wang X, Hu ZW, Li N, Deng XR, Zhang Y, Zheng XZ, Yang F, Weng HY, Dong JP, Liu JW, Wang YY, Liu XM. Thoughts and practice on the treatment of severe and critical new coronavirus pneumonia. Zhonghua Jie He He Hu Xi Za Zhi. 2020;43(0):E038. doi: 10.3760/cma.j.cn112147-20200312-00320. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Hirano T, Murakami M. COVID-19: a new virus, but a familiar receptor and cytokine release syndrome. Immunity. 2020;S1074-7613(20):30161–30168. doi: 10.1016/j.immuni.2020.04.003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Liu F, Li L, Xu M, Wu J, Luo D, Zhu Y, Li B, Song X, Zhou X. Prognostic value of interleukin-6, C-reactive protein, and procalcitonin in patients with COVID-19. J Clin Virol. 2020;127:104370. doi: 10.1016/j.jcv.2020.104370. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Conti P, Ronconi G, Caraffa A, Gallenga CE, Ross R, Frydas I, Kritas SK. Induction of pro-inflammatory cytokines (IL-1 and IL-6) and lung inflammation by Coronavirus-19 (COVI-19 or SARS-CoV-2): anti-inflammatory strategies. J Biol Regul Homeost Agents. 2020;34(2):1. doi: 10.23812/CONTI-E. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Xu X, Han MA-O, Li T, Sun W, Wang DA-O, Fu B, Zhou Y, Zheng X, Yang YA-O, Li X, Zhang X, Pan A, Wei H (2020) Effective treatment of severe COVID-19 patients with tocilizumab. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 202005615 (1091-6490 (Electronic)). 10.1073/pnas.2005615117 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 18.Capecchi PA-O, Lazzerini PE, Volterrani L, Mazzei MA, Rossetti B, Zanelli G, Bennett D, Bargagli E, Franchi F, Cameli M, Valente S, Cantarini L, Frediani B (2020) Antirheumatic agents in covid-19: is IL-6 the right target? Ann Rheum Dis:annrheumdis-2020-217523. 10.1136/annrheumdis-2020-217523 [DOI] [PubMed]

- 19.Radbel J, Narayanan N, Bhatt PJ. Use of tocilizumab for COVID-19 infection-induced cytokine release syndrome: a cautionary case report. Chest. 2020;S0012-3692(20):30764–30769. doi: 10.1016/j.chest.2020.04.024. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Yang X, Yu Y, Xu J, Shu H, Ja X, Liu H, Wu Y, Zhang L, Yu Z, Fang M, Yu T, Wang Y, Pan S, Zou X, Yuan S, Shang Y. Clinical course and outcomes of critically ill patients with SARS-CoV-2 pneumonia in Wuhan, China: a single-centered, retrospective, observational study. Lancet Respir Med. 2020;8:475–481. doi: 10.1016/s2213-2600(20)30079-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Wang D, Hu B, Hu C, Zhu F, Liu X, Zhang J, Wang B, Xiang H, Cheng Z, Xiong Y, Zhao Y, Li Y, Wang X, Peng Z. Clinical characteristics of 138 hospitalized patients with 2019 novel coronavirus–infected pneumonia in Wuhan, China. JAMA. 2020;323(11):1061. doi: 10.1001/jama.2020.1585. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Zhou F, Yu T, Du R, Fan G, Liu Y, Liu Z, Xiang J, Wang Y, Song B, Gu X, Guan L, Wei Y, Li H, Wu X, Xu J, Tu S, Zhang Y, Chen H, Cao B. Clinical course and risk factors for mortality of adult inpatients with COVID-19 in Wuhan, China: a retrospective cohort study. Lancet. 2020;395:1054–1062. doi: 10.1016/s0140-6736(20)30566-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Liu WJ, Zhao M, Liu K, Xu K, Wong G, Tan W, Gao GF. T-cell immunity of SARS-CoV: implications for vaccine development against MERS-CoV. Antivir Res. 2017;137:82–92. doi: 10.1016/j.antiviral.2016.11.006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Chu H, Zhou J, Wong BH, Li C, Chan JF, Cheng ZS, Yang D, Wang D, Lee AC, Li C, Yeung ML, Cai JP, Chan IH, Ho WK, To KK. Zheng BJ, Yao Y, Qin C, Yuen KY. Middle East respiratory syndrome coronavirus efficiently infects human primary T lymphocytes and activates the extrinsic and intrinsic apoptosis pathways. J Infect Dis. 2016;213(6):904–914. doi: 10.1093/infdis/jiv380. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Zheng H-Y, Zhang M, Yang C-X, Zhang N, Wang X-C, Yang X-P, Dong X-Q, Zheng Y-T. Elevated exhaustion levels and reduced functional diversity of T cells in peripheral blood may predict severe progression in COVID-19 patients. Cell Mol Immunol. 2020;17:541–543. doi: 10.1038/s41423-020-0401-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Holshue ML, DeBolt C, Lindquist S, Lofy KH, Wiesman J, Bruce H, Spitters C, Ericson K, Wilkerson S, Tural A, Diaz G, Cohn A, Fox L, Patel A, Gerber SI, Kim L, Tong S, Lu X, Lindstrom S, Pallansch MA, Weldon WC, Biggs HM, Uyeki TM, Pillai SK. First case of 2019 novel coronavirus in the United States. N Engl J Med. 2020;380(10):929–936. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa2001191. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]