Abstract

Given a regular language L over an ordered alphabet  , the set of lexicographically smallest (resp., largest) words of each length is itself regular. Moreover, there exists an unambiguous finite-state transducer that, on a given word

, the set of lexicographically smallest (resp., largest) words of each length is itself regular. Moreover, there exists an unambiguous finite-state transducer that, on a given word  , outputs the length-lexicographically smallest word larger than w (henceforth called the L-successor of w). In both cases, naïve constructions result in an exponential blowup in the number of states. We prove that if L is recognized by a DFA with n states, then

, outputs the length-lexicographically smallest word larger than w (henceforth called the L-successor of w). In both cases, naïve constructions result in an exponential blowup in the number of states. We prove that if L is recognized by a DFA with n states, then  states are sufficient for a DFA to recognize the subset S(L) of L composed of its lexicographically smallest words. We give a matching lower bound that holds even if S(L) is represented as an NFA. We then show that the same upper and lower bounds hold for an unambiguous finite-state transducer that computes L-successors.

states are sufficient for a DFA to recognize the subset S(L) of L composed of its lexicographically smallest words. We give a matching lower bound that holds even if S(L) is represented as an NFA. We then show that the same upper and lower bounds hold for an unambiguous finite-state transducer that computes L-successors.

Introduction

One of the most basic problems in formal language theory is the problem of enumerating the words of a language L. Since, in general, L is infinite, language enumeration is often formalized in one of the following two ways:

A function that maps an integer

to the n-th word of L.

to the n-th word of L.A function that takes a word and maps it to the next word in L.

Both descriptions require some linear ordering of the words in order for them to be well-defined. Usually, radix order (also known as length-lexicographical order) is used. Throughout this work, we focus on the second formalization.

While enumeration is non-computable in general, there are many interesting special cases. In this paper, we investigate the case of fixed regular languages, where successors can be computed in linear time [1, 2, 9]. Moreover, Frougny [7] showed that for every regular language L, the mapping of words to their successors in L can be realized by a finite-state transducer. Later, Angrand and Sakarovitch refined this result [3], showing that the successor function of any regular language is a finite union of functions computed by sequential transducers that operate from right to left. However, to the best of our knowledge, no upper bound on the size of smallest transducer computing the successor function was known.

In this work, we consider transducers operating from left to right, and prove that the optimal upper bound for the size of transducers computing successors in L is in  , where n is the size of the smallest DFA for L.

, where n is the size of the smallest DFA for L.

The construction used to prove the upper bound relies heavily on another closely related result. Many years before Frougny published her proof, it had already been shown that if L is a regular language, the set of all lexicographically smallest (resp., largest) words of each length is itself regular; see, e.g., [11, 12]. This fact is used both in [3] and in our construction. In [12], it was shown that if L is recognized by a DFA with n states, then the set of all lexicographically smallest words is recognized by a DFA with  states. While it is easy to improve this upper bound to

states. While it is easy to improve this upper bound to  , the exact state complexity of this operation remained open. We prove that

, the exact state complexity of this operation remained open. We prove that  states are sufficient and that this upper bound is optimal. We also prove that nondeterminism does not help with recognizing lexicographically smallest words, i.e., the corresponding lower bound still holds if the constructed automaton is allowed to be nondeterministic.

states are sufficient and that this upper bound is optimal. We also prove that nondeterminism does not help with recognizing lexicographically smallest words, i.e., the corresponding lower bound still holds if the constructed automaton is allowed to be nondeterministic.

The key component to our results is a careful investigation of the structure of lexicographically smallest words. This is broken down into a series of technical lemmas in Sect. 3, which are interesting in their own right. Some of the other techniques are similar to those already found in [3], but need to be carried out more carefully to achieve the desired upper bound.

Preliminaries

We assume familiarity with basic concepts of formal language theory and automata theory; see [8, 13] for a comprehensive introduction. Below, we introduce concepts and notation specific to this work.

Ordered Words and Languages. Let  be a finite ordered alphabet. Throughout the paper, we consider words ordered by radix order, which is defined by

be a finite ordered alphabet. Throughout the paper, we consider words ordered by radix order, which is defined by  if either

if either  or there exist factorizations

or there exist factorizations  ,

,  with

with  and

and  such that

such that  . We write

. We write  if

if  or

or  . In this case, the word u is smaller than v and the word v is larger than u.

. In this case, the word u is smaller than v and the word v is larger than u.

For a language  and two words

and two words  , we say that v is the L-successor of u if

, we say that v is the L-successor of u if  and

and  for all

for all  with

with  . Similarly, u is the L-predecessor of v if

. Similarly, u is the L-predecessor of v if  and

and  for all

for all  with

with  . A word is L-minimal if it has no L-predecessor. A word is L-maximal if it has no L-successor. Note that every nonempty language contains exactly one L-minimal word. It contains a (unique) L-maximal word if and only if L is finite. A word

. A word is L-minimal if it has no L-predecessor. A word is L-maximal if it has no L-successor. Note that every nonempty language contains exactly one L-minimal word. It contains a (unique) L-maximal word if and only if L is finite. A word  is L-length-preserving if it is not L-maximal and the L-successor of u has length

is L-length-preserving if it is not L-maximal and the L-successor of u has length  . Words that are not L-length-preserving are called L-length-increasing. Note that by definition, an L-maximal word is always L-length-increasing. For convenience, we sometimes use the terms successor (resp., predecessor) instead of

. Words that are not L-length-preserving are called L-length-increasing. Note that by definition, an L-maximal word is always L-length-increasing. For convenience, we sometimes use the terms successor (resp., predecessor) instead of  -successor (resp.,

-successor (resp.,  -predecessor).

-predecessor).

For a given language  , the set of all smallest words of each length in L is denoted by S(L). It is formally defined as follows:

, the set of all smallest words of each length in L is denoted by S(L). It is formally defined as follows:

|

Similarly, we define B(L) to be the set of all L-length-increasing words:

|

A language  is thin if it contains at most one word of each length, i.e.,

is thin if it contains at most one word of each length, i.e.,  for all

for all  . It is easy to see that for every language

. It is easy to see that for every language  , the languages S(L) and B(L) are thin.

, the languages S(L) and B(L) are thin.

Finite Automata and Transducers. A nondeterministic finite automaton (NFA for short) is a 5-tuple  where Q is a finite set of states,

where Q is a finite set of states,  is a finite alphabet,

is a finite alphabet,  is the initial state,

is the initial state,  is the set of accepting states and

is the set of accepting states and  is the transition function. We usually use the notation

is the transition function. We usually use the notation  instead of

instead of  , and we extend the transition function to

, and we extend the transition function to  by letting

by letting  and

and  for all

for all  ,

,  , and

, and  . For a state

. For a state  and a word

and a word  , we also use the notation

, we also use the notation  instead of

instead of  for convenience. A word

for convenience. A word  is accepted by the NFA if

is accepted by the NFA if  . We sometimes use the notation

. We sometimes use the notation  to indicate that

to indicate that  . An NFA is unambiguous if for every input, there exists at most one accepting run. Unambiguous NFA are also called unambiguous finite state automata (UFA). A deterministic finite automaton (DFA for short) is an NFA

. An NFA is unambiguous if for every input, there exists at most one accepting run. Unambiguous NFA are also called unambiguous finite state automata (UFA). A deterministic finite automaton (DFA for short) is an NFA  with

with  for all

for all  and

and  . Since this implies

. Since this implies  for all

for all  , we sometimes identify the singleton

, we sometimes identify the singleton  with the only element it contains.

with the only element it contains.

A finite-state transducer is a nondeterministic finite automaton that additionally produces some output that depends on the current state, the current letter and the successor state. For each transition, we allow both the input and the output letter to be empty. Formally, it is a 6-tuple  where Q is a finite set of states,

where Q is a finite set of states,  and

and  are finite alphabets,

are finite alphabets,  is the initial state and

is the initial state and  is the set of accepting states, and

is the set of accepting states, and  is the transition function. One can extend this transition function to the product

is the transition function. One can extend this transition function to the product  . To this end, we first define the

. To this end, we first define the  -closure of a set

-closure of a set  as the smallest superset C of T with

as the smallest superset C of T with  . We then define

. We then define  to be the

to be the  -closure of

-closure of  and

and  to be the

to be the  -closure of

-closure of  for all

for all  ,

,  and

and  . We sometimes use the notation

. We sometimes use the notation  to indicate that

to indicate that  . A finite-state transducer is unambiguous if, for every input, there exists at most one accepting run.

. A finite-state transducer is unambiguous if, for every input, there exists at most one accepting run.

The State Complexity of S(L)

It is known that if L is a regular language, then both S(L) and B(L) are also regular [11, 12]. In this section, we investigate the state complexity of the operations  and

and  for regular languages. Since the operations are symmetric, we focus on the former. To this end, we first prove some technical lemmas. The first lemma is a simple observation that helps us investigate the structure of words in S(L).

for regular languages. Since the operations are symmetric, we focus on the former. To this end, we first prove some technical lemmas. The first lemma is a simple observation that helps us investigate the structure of words in S(L).

Lemma 1

Let  with

with  . Then

. Then  or

or  or

or  .

.

Proof

Note that uy and yv are words of the same length. If  , then

, then  . Similarly,

. Similarly,  immediately yields

immediately yields  . The last case is

. The last case is  , which implies

, which implies  .

.

Using this observation, we can generalize a well-known factorization technique for regular languages to minimal words. For a DFA with state set Q, a state  and a word

and a word  , we define

, we define

|

to be the sequence of all states that are visited when starting in state q and following the transitions labeled by the letters from w.

Lemma 2

Let  be a DFA over

be a DFA over  with n states and with initial state

with n states and with initial state  . Then for every word

. Then for every word  , there exists a factorization

, there exists a factorization  with

with  and

and  such that, for all

such that, for all  , the following hold:

, the following hold:

,

, , and

, and is not a prefix of

is not a prefix of  .

.

Additionally, if  , this factorization can be chosen such that

, this factorization can be chosen such that

-

(d)

the lengths

are pairwise disjoint (i.e.,

are pairwise disjoint (i.e.,  ) and

) and -

(e)

there exists at most one

with

with  .

.

Proof

To construct the desired factorization, initialize  and

and  and follow these steps:

and follow these steps:

If

, we are done. If

, we are done. If  and the states in

and the states in  are pairwise distinct, let

are pairwise distinct, let  and

and  and we are done. Otherwise, factorize

and we are done. Otherwise, factorize  with

with  minimal such that

minimal such that  contains exactly one state twice, i.e.,

contains exactly one state twice, i.e.,  distinct states in total.

distinct states in total.Choose the unique factorization

such that

such that  and

and  .

.Let

and

and  .

.If

and

and  and

and  , increment

, increment  and go back to step 1. Otherwise, let

and go back to step 1. Otherwise, let  ,

,  and

and  ; then go back to step 1.

; then go back to step 1.

This factorization satisfies the first three properties by construction. It remains to show that if  , then Properties (d) and (e) are satisfied as well.

, then Properties (d) and (e) are satisfied as well.

Let us begin with Property (d). For the sake of contradiction, assume that there exist two indices a, b with  and

and  . Note that by construction,

. Note that by construction,  and

and  must be nonempty. Moreover, by Property (a), the words

must be nonempty. Moreover, by Property (a), the words

|

both belong to  . However, since

. However, since  , neither

, neither  nor

nor  can be strictly smaller than w. Using Lemma 1, we obtain that

can be strictly smaller than w. Using Lemma 1, we obtain that  . This contradicts Property (c).

. This contradicts Property (c).

Property (e) can be proved by using the same argument: Assume that there exist indices a, b with  and

and  . The words

. The words  and

and  have the same lengths. We define

have the same lengths. We define

|

and obtain  , which is a contradiction as above.

, which is a contradiction as above.

The existence of such a factorization almost immediately yields our next technical ingredient.

Lemma 3

Let  be a DFA with

be a DFA with  states. Let

states. Let  be the initial state of

be the initial state of  and let

and let  . Then there exists a factorization

. Then there exists a factorization  with

with  ,

,  and

and  such that

such that  . In particular,

. In particular,  .

.

Proof

Let  be a factorization that satisfies all properties in the statement of Lemma 2. Suppose first that all exponents

be a factorization that satisfies all properties in the statement of Lemma 2. Suppose first that all exponents  are at most n. Using Properties (b) and (d), we obtain

are at most n. Using Properties (b) and (d), we obtain  and the maximum length of w is achieved when all lengths

and the maximum length of w is achieved when all lengths  are present among the factors

are present among the factors  and the corresponding

and the corresponding  have lengths

have lengths  . This yields

. This yields

|

where the last inequality uses  . Therefore, we may set

. Therefore, we may set  ,

,  and

and  .

.

If not all exponents are at most n, by Property (e), there exists a unique index j with  . In this case, let

. In this case, let  ,

,  and

and  . The upper bound

. The upper bound  still follows by the argument above, and

still follows by the argument above, and  is a direct consequence of Property (b). Moreover,

is a direct consequence of Property (b). Moreover,  and Property (a) together imply that

and Property (a) together imply that  .

.

For the next lemma, we need one more definition. Let  be a DFA with initial state

be a DFA with initial state  . Two tuples (x, y, z) and

. Two tuples (x, y, z) and  are cycle-disjoint with respect to

are cycle-disjoint with respect to

if the sets of states in

if the sets of states in  and

and  are either equal or disjoint.

are either equal or disjoint.

Lemma 4

Let  be a DFA with

be a DFA with  states and initial state

states and initial state  . Let (x, y, z) and

. Let (x, y, z) and  be tuples that are not cycle-disjoint with respect to

be tuples that are not cycle-disjoint with respect to  such that

such that

|

Then either  or

or  only contains words of length at most

only contains words of length at most  .

.

Proof

Since the tuples are not cycle-disjoint with respect to  , we can factorize

, we can factorize  and

and  such that

such that  .

.

Note that since  , the sets of states in

, the sets of states in  and

and  coincide for all

coincide for all  . By the same argument, the sets of states in

. By the same argument, the sets of states in  and

and  coincide for all

coincide for all  .

.

If the powers  and

and  were equal, then

were equal, then  and

and  coincide. By the previous observation, this would imply that the tuples (x, y, z) and

coincide. By the previous observation, this would imply that the tuples (x, y, z) and  are cycle-disjoint, a contradiction. We conclude

are cycle-disjoint, a contradiction. We conclude  .

.

By symmetry, we may assume that  . But then, for every word of the form

. But then, for every word of the form  with

with  , there exists a strictly smaller word

, there exists a strictly smaller word  in

in  . To see that this word indeed belongs to

. To see that this word indeed belongs to  , note that

, note that  . This means that all words in

. This means that all words in  are of the form

are of the form  with

with  .

.

The previous lemmas now allow us to replace any language L by another language that has a simple structure and approximates L with respect to S(L).

Lemma 5

Let  be a DFA over

be a DFA over  with

with  states. Then there exist an integer

states. Then there exist an integer  and tuples

and tuples  such that the following properties hold:

such that the following properties hold:

-

(i)

,

, -

(ii)

for all

for all  , and

, and -

(iii)

where

where  .

.

Proof

If we ignore the required upper bound  and Property (iii) for now, the statement follows immediately from Lemma 3 and the fact that there are only finitely many different tuples (x, y, z) with

and Property (iii) for now, the statement follows immediately from Lemma 3 and the fact that there are only finitely many different tuples (x, y, z) with  and

and  . We start with such a finite set of tuples

. We start with such a finite set of tuples  and show that we can repeatedly eliminate tuples until at most

and show that we can repeatedly eliminate tuples until at most  cycle-disjoint tuples remain. The desired upper bound

cycle-disjoint tuples remain. The desired upper bound  then follows automatically.

then follows automatically.

In each step of this elimination process, we handle one of the following cases:

If there are two distinct tuples

and

and  with

with  and

and  , there are two possible scenarios. If

, there are two possible scenarios. If  , then for every word in

, then for every word in  there exists a smaller word in

there exists a smaller word in  and we can remove

and we can remove  from the set of tuples. By the same argument, we can remove the tuple

from the set of tuples. By the same argument, we can remove the tuple  if

if  and

and  .

.Now consider the case that there are two distinct tuples

and

and  with

with  and

and  but

but  . We first check whether

. We first check whether  . If true, we add the tuple

. If true, we add the tuple  , otherwise we add

, otherwise we add  . If

. If  , we know that each word in

, we know that each word in  has a smaller word in

has a smaller word in  , and we remove the tuple

, and we remove the tuple  . Otherwise, we can remove

. Otherwise, we can remove  by the same argument.

by the same argument.The last case is that there exist two tuples

and

and  that are not cycle-disjoint. By Lemma 4, we can remove at least one of these tuples and replace it by multiple tuples of the form

that are not cycle-disjoint. By Lemma 4, we can remove at least one of these tuples and replace it by multiple tuples of the form  . Note that the newly introduced tuples might be of the form

. Note that the newly introduced tuples might be of the form  with

with  but Lemma 4 asserts that they still satisfy

but Lemma 4 asserts that they still satisfy  .

.

Note that we introduce new tuples of the form  during this elimination process. These new tuples are readily eliminated using the first rule.

during this elimination process. These new tuples are readily eliminated using the first rule.

After iterating this elimination process, the remaining tuples are pairwise cycle-disjoint and the pairs  assigned to these tuples

assigned to these tuples  are pairwise disjoint. Properties (ii) and (iii) yield the desired upper bound on k.

are pairwise disjoint. Properties (ii) and (iii) yield the desired upper bound on k.

Remark 1

While S(L) can be approximated by a language of the simple form given in Lemma 5, the language S(L) itself does not necessarily have such a simple description. An example of a regular language L where S(L) does not have such a simple form is given in the proof of Theorem 2.

The last step is to investigate languages L of the simple structure described in the previous lemma and show how to construct a small DFA for S(L).

Lemma 6

Let  . Let

. Let  with

with  and

and  for all

for all  and

and  where

where  . Then S(L) is recognized by a DFA with

. Then S(L) is recognized by a DFA with  states.

states.

Proof

We describe how to construct a DFA of the desired size that recognizes the language S(L). This DFA is the product automaton of multiple components.

In one component (henceforth called the counter component), we keep track of the length of the processed input as long as at most  letters have been consumed. If more than

letters have been consumed. If more than  letters have been consumed, we only keep track of the length of the processed input modulo all numbers

letters have been consumed, we only keep track of the length of the processed input modulo all numbers  for

for  .

.

For each  , there is an additional component (henceforth called the i-th activity component). In this component, we keep track of whether the currently processed prefix u of the input is a prefix of a word in

, there is an additional component (henceforth called the i-th activity component). In this component, we keep track of whether the currently processed prefix u of the input is a prefix of a word in  , whether u is a prefix of a word in

, whether u is a prefix of a word in  and whether

and whether  . Note that if some prefix of the input is not a prefix of a word in

. Note that if some prefix of the input is not a prefix of a word in  , no longer prefix of the input can be a prefix of a word in

, no longer prefix of the input can be a prefix of a word in  . The information stored in the counter component suffices to compute the possible letters of

. The information stored in the counter component suffices to compute the possible letters of  allowed to be read in each step to maintain the prefix invariants.

allowed to be read in each step to maintain the prefix invariants.

It remains to describe how to determine whether a state is final. To this end, we use the following procedure. First, we determine which sets of the form  the input word leading to the considered state belongs to. These languages are called the active languages of the state. They can be obtained from the activity components of the state. If there are no active languages, the state is immediately marked as not final. If the length of the input word w leading to the considered state is

the input word leading to the considered state belongs to. These languages are called the active languages of the state. They can be obtained from the activity components of the state. If there are no active languages, the state is immediately marked as not final. If the length of the input word w leading to the considered state is  or less, we can obtain

or less, we can obtain  from the counter component and reconstruct w from the set of active languages. If the length of the input is larger than

from the counter component and reconstruct w from the set of active languages. If the length of the input is larger than  , we cannot fully recover the input from the information stored in the state. However, we can determine the shortest word w with

, we cannot fully recover the input from the information stored in the state. However, we can determine the shortest word w with  such that

such that  is consistent with the length information stored in the counter component and w itself is consistent with the set of active languages. In either case, we then compute the set A of all words of length

is consistent with the length information stored in the counter component and w itself is consistent with the set of active languages. In either case, we then compute the set A of all words of length  that belong to any (possibly not active) language

that belong to any (possibly not active) language  with

with  . If w is the smallest word in A, the state is final, otherwise it is not final.

. If w is the smallest word in A, the state is final, otherwise it is not final.

The desired upper bound on the number of states follows from known estimates on the least common multiple of a set of natural numbers with a given sum; see e.g., [6].

We can now combine the previous lemmas to obtain an upper bound on the state complexity of S(L).

Theorem 1

Let L be a regular language that is recognized by a DFA with n states. Then S(L) is recognized by a DFA with  states.

states.

Proof

By Lemma 5, we know that there exists a language  of the form described in the statement of Lemma 6 with

of the form described in the statement of Lemma 6 with  . Since

. Since  implies

implies  and since

and since  , this also means that

, this also means that  . Lemma 6 now shows that there exists a DFA of the desired size.

. Lemma 6 now shows that there exists a DFA of the desired size.

To show that the result is optimal, we provide a matching lower bound.

Theorem 2

There exists a family of DFA  over a binary alphabet such that

over a binary alphabet such that  has n states and every NFA for

has n states and every NFA for  has

has  states.

states.

Proof

For  , let

, let  be the i-th prime number and let

be the i-th prime number and let  . We define a language

. We define a language

|

It is easy to see that L is recognized by a DFA with  states. We show that S(L) is not recognized by any NFA with less than p states. From known estimates on the prime numbers (e.g., [4, Sec. 2.7]), this suffices to prove our claim.

states. We show that S(L) is not recognized by any NFA with less than p states. From known estimates on the prime numbers (e.g., [4, Sec. 2.7]), this suffices to prove our claim.

Let  be a NFA for S(L) and assume, for the sake of contradiction, that

be a NFA for S(L) and assume, for the sake of contradiction, that  has less than p states. Note that since for each

has less than p states. Note that since for each  , the integer p is a multiple of

, the integer p is a multiple of  , the language L does not contain any word of the form

, the language L does not contain any word of the form  . Therefore, the word

. Therefore, the word  belongs to S(L) and by assumption, an accepting path for this word in

belongs to S(L) and by assumption, an accepting path for this word in  must contain a loop of some length

must contain a loop of some length  . But then

. But then  is accepted by

is accepted by  , too. However, since

, too. However, since  , there exists some

, there exists some  such that

such that  does not divide

does not divide  . This means that

. This means that  also does not divide

also does not divide  . Thus,

. Thus,  , contradicting the fact that

, contradicting the fact that  belongs to S(L).

belongs to S(L).

Combining the previous two theorems, we obtain the following corollary.

Corollary 1

Let L be a language that is recognized by a DFA with n states. Then, in general,  states are necessary and sufficient for a DFA or NFA to recognize S(L).

states are necessary and sufficient for a DFA or NFA to recognize S(L).

By reversing the alphabet ordering, we immediately obtain similar results for largest words.

Corollary 2

Let L be a language that is recognized by a DFA with n states. Then, in general,  states are necessary and sufficient for a DFA or NFA to recognize B(L).

states are necessary and sufficient for a DFA or NFA to recognize B(L).

The State Complexity of Computing Successors

One approach to efficient enumeration of a regular language L is constructing a transducer that reads a word and outputs its L-successor [3, 7]. We consider transducers that operate from left to right. Since the output letter in each step might depend on letters that have not yet been read, this transducer needs to be nondeterministic. However, the construction can be made unambiguous, meaning that for any given input, at most one computation path is accepting and yields the desired output word. In this paper, we prove that, in general,  states are necessary and sufficient for a transducer that performs this computation.

states are necessary and sufficient for a transducer that performs this computation.

Our proof is split into two parts. First, we construct a transducer that only maps L-length-preserving words to their corresponding L-successors. All other words are rejected. This construction heavily relies on results from the previous section. Then we extend this transducer to L-length-increasing words by using a technique called padding. For the first part, we also need the following result.

Theorem 3

Let  be a thin language that is recognized by a DFA with n states. Then the languages

be a thin language that is recognized by a DFA with n states. Then the languages

|

are recognized by UFA with 2n states.

Proof

Let  be a DFA for L and let

be a DFA for L and let  . We construct a UFA with 2n states for

. We construct a UFA with 2n states for  . The statement for

. The statement for  follows by symmetry.

follows by symmetry.

The state set of the UFA is  , the initial state is

, the initial state is  and the set of final states is

and the set of final states is  . The transitions are

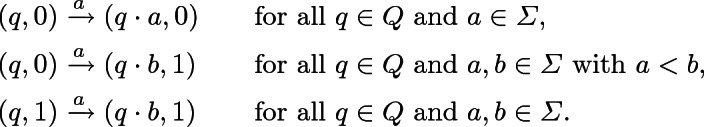

. The transitions are

It is easy to verify that this automaton indeed recognizes  . To see that this automaton is unambiguous, consider an accepting run of a word w of length

. To see that this automaton is unambiguous, consider an accepting run of a word w of length  . Note that the sequence of first components of the states in this run yield an accepting path of length

. Note that the sequence of first components of the states in this run yield an accepting path of length  in

in  . Since

. Since  is thin, this path is unique. Therefore, the sequence of first components is uniquely defined. The second components are then uniquely defined, too: they are 0 up to the first position where w differs from the unique word of length

is thin, this path is unique. Therefore, the sequence of first components is uniquely defined. The second components are then uniquely defined, too: they are 0 up to the first position where w differs from the unique word of length  in L, and 1 afterwards.

in L, and 1 afterwards.

For a language  , we denote by

, we denote by  the language of all words from

the language of all words from  such that there exists no strictly larger word of the same length in L. Combining Theorem 1 and Theorem 3, the following corollary is immediate.

such that there exists no strictly larger word of the same length in L. Combining Theorem 1 and Theorem 3, the following corollary is immediate.

Corollary 3

Let L be a language that is recognized by a DFA with n states. Then there exists a UFA with  states that recognizes the language

states that recognizes the language  .

.

For a language  , we define

, we define

|

If L is regular, it is easy to construct an NFA for the complement of X(L), henceforth denoted as  . To this end, we take a DFA for L and replace the label of each transition with all letters from

. To this end, we take a DFA for L and replace the label of each transition with all letters from  . This NFA can also be viewed as an NFA over the unary alphabet

. This NFA can also be viewed as an NFA over the unary alphabet  ; here,

; here,  is interpreted as a letter, not a set. It can be converted to a DFA for

is interpreted as a letter, not a set. It can be converted to a DFA for  by using Chrobak’s efficient determinization procedure for unary NFA [6]. The resulting DFA can then be complemented to obtain a DFA for X(L):

by using Chrobak’s efficient determinization procedure for unary NFA [6]. The resulting DFA can then be complemented to obtain a DFA for X(L):

Corollary 4

Let L be a language that is recognized by a DFA with n states. Then there exists a DFA with  states that recognizes the language X(L).

states that recognizes the language X(L).

We now use the previous results to prove an upper bound on the size of a transducer performing a variant of the L-successor computation that only works for L-length-preserving words.

Theorem 4

Let L be a language that is recognized by a DFA with n states. Then there exists an unambiguous finite-state transducer with  states that rejects all L-length-increasing words and maps every L-length-preserving word to its L-successor.

states that rejects all L-length-increasing words and maps every L-length-preserving word to its L-successor.

Proof

Let  be a DFA for L and let

be a DFA for L and let  . For every

. For every  , we denote by

, we denote by  the DFA that is obtained by making q the new initial state of

the DFA that is obtained by making q the new initial state of  . We use

. We use  to denote DFA with

to denote DFA with  states that recognizes the language

states that recognizes the language  . These DFA exist by Theorem 1. Moreover, by Corollary 3, there exist UFA with

. These DFA exist by Theorem 1. Moreover, by Corollary 3, there exist UFA with  states that recognize the languages

states that recognize the languages  . We denote these UFA by

. We denote these UFA by  . Similarly, we use

. Similarly, we use  to denote DFA with

to denote DFA with  states that recognize

states that recognize  . These DFA exist by Corollary 4.

. These DFA exist by Corollary 4.

In the finite-state transducer, we first simulate  on a prefix u of the input, copying the input letters in each step, i.e., producing the output u. At some position, after having read a prefix u leading up to the state

on a prefix u of the input, copying the input letters in each step, i.e., producing the output u. At some position, after having read a prefix u leading up to the state  , we nondeterministically decide to output a letter b that is strictly larger than the current input letter a. From then on, we guess an output letter in each step and start simulating multiple automata in different components. In one component, we simulate

, we nondeterministically decide to output a letter b that is strictly larger than the current input letter a. From then on, we guess an output letter in each step and start simulating multiple automata in different components. In one component, we simulate  on the remaining input. In another component, we simulate

on the remaining input. In another component, we simulate  on the guessed output. In additional components, for each

on the guessed output. In additional components, for each  with

with  , we simulate

, we simulate  on the input. The automata in all components must accept in order for the transducer to accept the input.

on the input. The automata in all components must accept in order for the transducer to accept the input.

The automaton  verifies that there is no word in L that starts with the prefix ua, has the same length as the input word and is strictly larger than the input word. The automaton

verifies that there is no word in L that starts with the prefix ua, has the same length as the input word and is strictly larger than the input word. The automaton  verifies that there is no word in L that starts with the prefix ub, has the same length as the input word and is strictly smaller than the output word. It also certifies that the output word belongs to L. For each letter c, the automaton

verifies that there is no word in L that starts with the prefix ub, has the same length as the input word and is strictly smaller than the output word. It also certifies that the output word belongs to L. For each letter c, the automaton  verifies that there is no word in L that starts with the prefix uc and has the same length as the input word.

verifies that there is no word in L that starts with the prefix uc and has the same length as the input word.

Together, the components ensure that the guessed output is the unique successor of the input word, given that it is L-length-preserving. It is also clear that L-length-increasing words are rejected, since the  -component does not accept for any sequence of nondeterministic choices.

-component does not accept for any sequence of nondeterministic choices.

The construction given in the previous proof can be extended to also compute L-successors of L-length-increasing words. However, this requires some quite technical adjustments to the transducer. Instead, we use a technique called padding. A very similar approach appears in [3, Prop. 5.1].

We call the smallest letter of an ordered alphabet  the padding symbol of

the padding symbol of  . A language

. A language  is

is  -padded if

-padded if  is the padding symbol of

is the padding symbol of  and

and  for some

for some  . The key property of padded languages is that all words prefixed by a sufficiently long block of padding symbols are L-length-preserving.

. The key property of padded languages is that all words prefixed by a sufficiently long block of padding symbols are L-length-preserving.

Lemma 7

Let  be a DFA over

be a DFA over  with n states such that

with n states such that  is a

is a  -padded language. Let

-padded language. Let  and let

and let  . Let

. Let  be a word that is not K-maximal. Then the

be a word that is not K-maximal. Then the  -successor of

-successor of  has length

has length  .

.

Proof

Let v be the K-successor of u. By a standard pumping argument, we have  . This means that

. This means that  is well-defined and belongs to

is well-defined and belongs to  . Note that this word is strictly greater than

. Note that this word is strictly greater than  and has length

and has length  . Thus, the

. Thus, the  -successor of

-successor of  has length

has length  , too.

, too.

We now state the main result of this section.

Theorem 5

Let  be a deterministic finite automaton over

be a deterministic finite automaton over  with n states. Then there exists an unambiguous finite-state transducer with

with n states. Then there exists an unambiguous finite-state transducer with  states that maps every word to its

states that maps every word to its  -successor.

-successor.

Proof

We extend the alphabet by adding a new padding symbol  and convert

and convert  to a DFA for

to a DFA for  by adding a new initial state. The language

by adding a new initial state. The language  accepted by this new DFA is

accepted by this new DFA is  -padded. By Theorem 4 and Lemma 7, there exists an unambiguous transducer of the desired size that maps every word from

-padded. By Theorem 4 and Lemma 7, there exists an unambiguous transducer of the desired size that maps every word from  to its successor in

to its successor in  . It is easy to modify this transducer such that all words that do not belong to

. It is easy to modify this transducer such that all words that do not belong to  are rejected. We then replace every transition that reads a

are rejected. We then replace every transition that reads a  by a corresponding transition that reads the empty word instead. Similarly, we replace every transition that outputs a

by a corresponding transition that reads the empty word instead. Similarly, we replace every transition that outputs a  by a transition that outputs the empty word instead. Clearly, this yields the desired construction for the original language L. A careful analysis of the construction shows that the transducer remains unambiguous after each step.

by a transition that outputs the empty word instead. Clearly, this yields the desired construction for the original language L. A careful analysis of the construction shows that the transducer remains unambiguous after each step.

We now show that this construction is optimal up to constants in the exponent. The idea is similar to the construction used in Theorem 2.

Theorem 6

There exists a family of deterministic finite automata  such that

such that  has n states whereas the smallest unambiguous transducer that maps every word to its

has n states whereas the smallest unambiguous transducer that maps every word to its  -successor has

-successor has  states.

states.

Proof

Let  . Let

. Let  be the k smallest prime numbers such that

be the k smallest prime numbers such that  and let

and let  . We construct a deterministic finite automaton

. We construct a deterministic finite automaton  with

with  states such that the smallest transducer computing the desired mapping has at least p states. From known estimates on the prime numbers (e.g., [4, Sec. 2.7]), this suffices to prove our claim.

states such that the smallest transducer computing the desired mapping has at least p states. From known estimates on the prime numbers (e.g., [4, Sec. 2.7]), this suffices to prove our claim.

The automaton is defined over the alphabet  . It consists of an initial state

. It consists of an initial state  , an error state

, an error state  , and states (i, j) for

, and states (i, j) for  and

and  with transitions defined as follows:

with transitions defined as follows:

|

The set of accepting states is  . The language

. The language  is the set of all words of the form

is the set of all words of the form  with

with  such that j is a multiple of

such that j is a multiple of  .

.

Assume, to get a contradiction, that there exists an unambiguous transducer with less than p states that maps w to the smallest word in  strictly greater than w. Consider an accepting run of this transducer on some input of the form

strictly greater than w. Consider an accepting run of this transducer on some input of the form  with

with  large enough such that the run contains a cycle. Clearly, since

large enough such that the run contains a cycle. Clearly, since  and p are coprime, the output of the transducer has to be

and p are coprime, the output of the transducer has to be  . We fix one cycle in this run.

. We fix one cycle in this run.

If the number of  read in this cycle does not equal the number of

read in this cycle does not equal the number of  output in this cycle, by using a pumping argument, we can construct a word of the form

output in this cycle, by using a pumping argument, we can construct a word of the form  that is mapped to a word or the form

that is mapped to a word or the form  with

with  . This contradicts the fact that

. This contradicts the fact that  is a subset of

is a subset of  . Therefore, we may assume that both the number of letters read and output on the cycle is

. Therefore, we may assume that both the number of letters read and output on the cycle is  .

.

Again, by a pumping argument, this implies that  is mapped to

is mapped to  for every

for every  . Since

. Since  , at least one of the prime numbers

, at least one of the prime numbers  is coprime to r. Therefore, we can choose j such that

is coprime to r. Therefore, we can choose j such that  . However, this means that

. However, this means that  belongs to

belongs to  , contradicting the fact that the transducer maps

, contradicting the fact that the transducer maps  to

to  .

.

Combining the two previous theorems, we obtain the following corollary.

Corollary 5

Let L be a language that is recognized by a DFA with n states. Then, in general,  states are necessary and sufficient for an unambiguous finite-state transducer that maps words to their L-successors.

states are necessary and sufficient for an unambiguous finite-state transducer that maps words to their L-successors.

Contributor Information

Nataša Jonoska, Email: jonoska@mail.usf.edu.

Dmytro Savchuk, Email: savchuk@usf.edu.

Lukas Fleischer, Email: lukas.fleischer@uwaterloo.ca.

Jeffrey Shallit, Email: shallit@uwaterloo.ca.

References

- 1.Ackerman M, Mäkinen E. Three new algorithms for regular language enumeration. In: Ngo HQ, editor. Computing and Combinatorics; Heidelberg: Springer; 2009. pp. 178–191. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Ackerman M, Shallit J. Efficient enumeration of words in regular languages. Theoret. Comput. Sci. 2009;410(37):3461–3470. doi: 10.1016/j.tcs.2009.03.018. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Angrand P-Y, Sakarovitch J. Radix enumeration of rational languages. RAIRO - Theoret. Inform. Appl. 2010;44(1):19–36. doi: 10.1051/ita/2010003. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Bach E, Shallit J. Algorithmic Number Theory. Cambridge: MIT Press; 1996. [Google Scholar]

- 5.Berthé, V., Frougny, C., Rigo, M., Sakarovitch, J.: On the cost and complexity of the successor function. In: Arnoux, P., Bédaride, N., Cassaigne, J. (eds.) Proceedings of WORDS 2007, Technical Report, Institut de mathématiques de Luminy, pp. 43–56 (2007)

- 6.Chrobak M. Finite automata and unary languages. Theoret. Comput. Sci. 1986;47:149–158. doi: 10.1016/0304-3975(86)90142-8. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Frougny C. On the sequentiality of the successor function. Inf. Comput. 1997;139(1):17–38. doi: 10.1006/inco.1997.2650. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Hopcroft JE, Motwani R, Ullman JD. Introduction to Automata Theory, Languages, and Computation. 3. New York: Addison-Wesley Longman Publishing Co., Inc.; 2006. [Google Scholar]

- 9.Mäkinen E. On lexicographic enumeration of regular and context-free languages. Acta Cybern. 1997;13(1):55–61. [Google Scholar]

- 10.Okhotin AS. On the complexity of the string generation problem. Discret. Math. Appl. 2003;13:467–482. doi: 10.1515/156939203322694745. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Sakarovitch J. Deux remarques sur un théorème de S. Eilenberg. RAIRO - Theoret. Inform. Appl. 1983;17(1):23–48. doi: 10.1051/ita/1983170100231. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Shallit J. Numeration systems, linear recurrences, and regular sets. Inf. Comput. 1994;113(2):331–347. doi: 10.1006/inco.1994.1076. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Shallit J. A Second Course in Formal Languages and Automata Theory. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press; 2008. [Google Scholar]