Abstract

Cyclic dinucleotides (CDNs) have emerged as ubiquitous signaling molecules in all domains of life. In eukaryotes, CDN signaling systems are evolutionarily ancient and have developed to sense and respond to pathogen infection. On the other hand, dysregulation of these pathways has been implicated in the pathogenesis of autoimmune diseases. Thus, cyclic dinucleotides have garnered major interest over recent years for their ability to elicit potent immune responses in the eukaryotic host. Similarly, ancestral CDN-based signaling systems also appear to confer immunological protection against infection in prokaryotes. Therefore, a better understanding of the host processes regulated by CDNs will be of tremendous value in many areas of research. Here, we aim to review the latest discoveries and recent trends in cyclic dinucleotide research with a particular focus on the molecular mechanisms by which these small molecules mediate innate immunity.

Introduction

Immunity is the physiological process whereby organisms detect and defend themselves against disease by infectious agents. Within this working definition, the immune system has classically been divided into two branches: the innate arm and the adaptive arm. In contrast to adaptive or acquired immune defenses, which are often delayed and involve genetic rearrangement events, innate immunity is considered the first and immediate line of defense against invading pathogens [1]. This is accomplished by a suite of invariant, germline encoded receptors that recognize general, conserved, molecular features of infectious agents that are rarely or never found in the healthy host and, hence, does not confer any lasting, immunological memory [1]. Upon sensing the infectious insult, receptors of the immune system must then relay signals to effector proteins, culminating in pathogen elimination. In the context of innate immunity, this is often mediated by the employment of second messengers—small molecules that orchestrate key shifts in cellular function in response to altered environmental conditions. An emerging paradigm in prokaryotic and eukaryotic innate immune systems is the use of cyclic dinucleotide (CDN) second messengers [2–6]. As their name implies, CDNs are heterocyclic compounds synthesized by cyclases or nucleotidyltransferases (NTases) through the cyclization of two ribonucleoside triphosphate moieties via two ‘canonical’ (3’,5’) and/or ‘non-canonical’ (2’,5’) phosphodiester linkages. CDN signaling is resolved by the tightly regulated action of phosphodiesterase enzymes (PDEs), which catalyze the metal dependent hydrolysis of one or both phosphodiester bonds, yielding a linear (pNpN) dinucleotide intermediate or two nucleoside monophosphates, respectively.

While a number of CDN-based signaling systems have been identified to date (reviewed in detail by Krasteva and Sondermann [7]), innate immune sensing of pathogen infection is mediated by a conserved family of NTases including the dinucleotide cyclase in Vibrio cholerae (DncV) and its metazoan homologue cyclic GMP-AMP Synthase (cGAS) [4, 6, 8, 9]. This family of proteins was hence given the name cGAS/DncV-like nucleotidyltransferases (CD-NTases) [9]. Upon activation, CD-NTases catalyze the synthesis of CDN second messengers, including cyclic GMP-AMP (cGAMP), which function as immune ‘alarmones’ produced in the context of pathogen infection. Notably, prokaryotic 3’3’-CDNs (c[N(3′,5′)pN(3′,5′)p]) contain two ‘canonical’ (3’,5’) phosphodiester linkages; however, as this signaling system emerged in eukaryotes, it eventually transitioned to the use of 2’3’-cGAMP (c[G(2′,5′)pA(3′,5′)p]) containing mixed phosphodiester bonds in higher metazoans including humans [7, 10–12]. While the biochemical underpinnings for this transition still remain unclear, it is intriguing to hypothesize that this may afford some degree of immune discrimination between exogenous and endogenous sources of CDNs in higher eukaryotes. Despite this dissimilarity, cGAMP-based signaling systems constitute an ancient immune signaling pathway with evolutionary origins in prokaryotes [6]. This review will highlight the most recent discoveries and emerging themes in CDN-based innate immune signaling with an emphasis on CDN effectors, the regulation of CDN levels, and the strategies used by viruses to subvert this important signaling axis.

A Broad Family of CD-NTases in Bacteria Synthesizes Diverse Nucleotide Second Messengers

cGAS and DncV are the founding members of a large class of nucleotidyltransferases in both prokaryotes and eukaryotes. Whereas the evolutionary origins of cGAS in metazoans can be traced as far back as the sea anemone, Nemostella vectensis, CD-NTases have recently been found in more than ten percent of bacterial genomes spanning nearly every bacterial phylum including human commensal and pathogenic microorganisms [6, 9, 13, 14]. Although these enzymes are divergent at the amino acid level, they display common structural features including a DNA polymerase β-like nucleotidyltransferase fold [9]. Unlike other CDN cyclase families, CD-NTases display extreme diversity in their capacity to synthesize cyclic dinucleotides; moreover, cyclic trinucleotide products have also been observed including cyclic AMP-AMP-GMP produced by a CD-NTase from Enterobacter cloacae [9]. In addition to utilizing purines, bacterial CD-NTases can synthesize a number of pyrimidine containing 3’3’-CDNs, including: c-di-UMP and cyclic UMP-CMP as well as pyrimidine-purine hybrids (cyclic UMP-AMP and cyclic UMP-GMP) [9]. Although synthetic pyrimidine-based CDNs have been described, pyrimidine containing nucleotide second messengers have not been observed anywhere else in nature [15, 16]. Remarkably, the substrate specificity of these enzymes can be reprogrammed by single amino acid substitutions within the active site lid [9]. Such plasticity in CD-NTases may have conferred a fitness advantage, for example in the context of evolutionary arms races between bacteria and the phages that infect them.

CD-NTases and Innate Anti-Phage Immunity

In bacteria, CD-NTases are found within the genomic context of a cyclic oligonucleotide-based anti-phage signaling system (CBASS) comprised of a core CD-NTase-effector unit and two accessory proteins with domains commonly found in eukaryotic ubiquitination machinery including an E1/E2-containing enzyme and a JAB de-ubiquitinase [6]. CBASS systems confer marked resistance against a wide array of DNA-phages in a manner dependent on both CD-NTase and effector enzyme activity [6]. Interestingly, the accessory proteins appear to be conditionally essential during infection with select phages, raising the intriguing possibility that these proteins may counteract viral immune evasion strategies [6]. Similar to metazoans, CD-NTase enzymatic activity appears to be triggered by bacteriophage infection as 3’3’-cGAMP is undetectable in uninfected cells [4, 6]. The ligand and/or activation mechanism for bacterial CD-NTases remains to be fully elucidated, but, because bacteria do not compartmentalize their DNA, it is unlikely to be viral nucleic acids as is the case for metazoan CD-NTases [4]. Intriguingly, some CD-NTases appear to become activated following recognition of specific, bacteriophage peptide motifs by Hop1, Rev7, and Mad2 (HORMA) domain containing receptors [17]. Although several, non-redundant 3’3’-cGAMP-selective PDEs have been identified in V. cholerae, the roles of these enzymes, if any, in CBASS signaling are unclear [18]. One possibility is that PDEs may function as a rheostat to control CBASS activation; alternatively, because canonical CBASS signaling ultimately results in cell death, as discussed below, resolution of CDN signaling may not be necessary.

A number of CBASS effector proteins have been identified, but the best characterized effector to date is a CDN-activated patatin-like phospholipase originally identified in V. cholerae and hence given the name CapV (Figure 1) [6, 19]. Upon activation by 3’3’-CDNs, CapV-like phospholipases hydrolyze phospholipids in the bacterial inner cell membrane resulting in loss of membrane integrity and cell lysis [6, 19]. Thus, the CD-NTase-phospholipase signaling axis constitutes a ‘cellular suicide’ program intended to protect the bacterial community through abortive phage infection [6]. In lieu of a phospholipase, a number of alternative effectors have been identified in CBASS systems including HNH-type endonucleases, a membrane spanning protein, a domain of unknown function, as well as a Toll Interleukin Receptor (TIR) domain, which also appear to mediate innate anti-phage immunity [6, 17, 20]. Interestingly, in a few cases, the CBASS systems contain a hybrid effector containing an N-terminal TIR domain fused to a C-terminal domain resembling the metazoan cGAMP effector Stimulator of Interferon Genes or STING (see below) [6, 21–23]. Although it is unclear if and how the TIR-STING effector mediates anti-phage immunity, it is possible that metazoan cGAS-cGAMP-STING signaling systems originate from these ancestral bacterial CBASS systems and have retained their role in innate antiviral defense along the way.

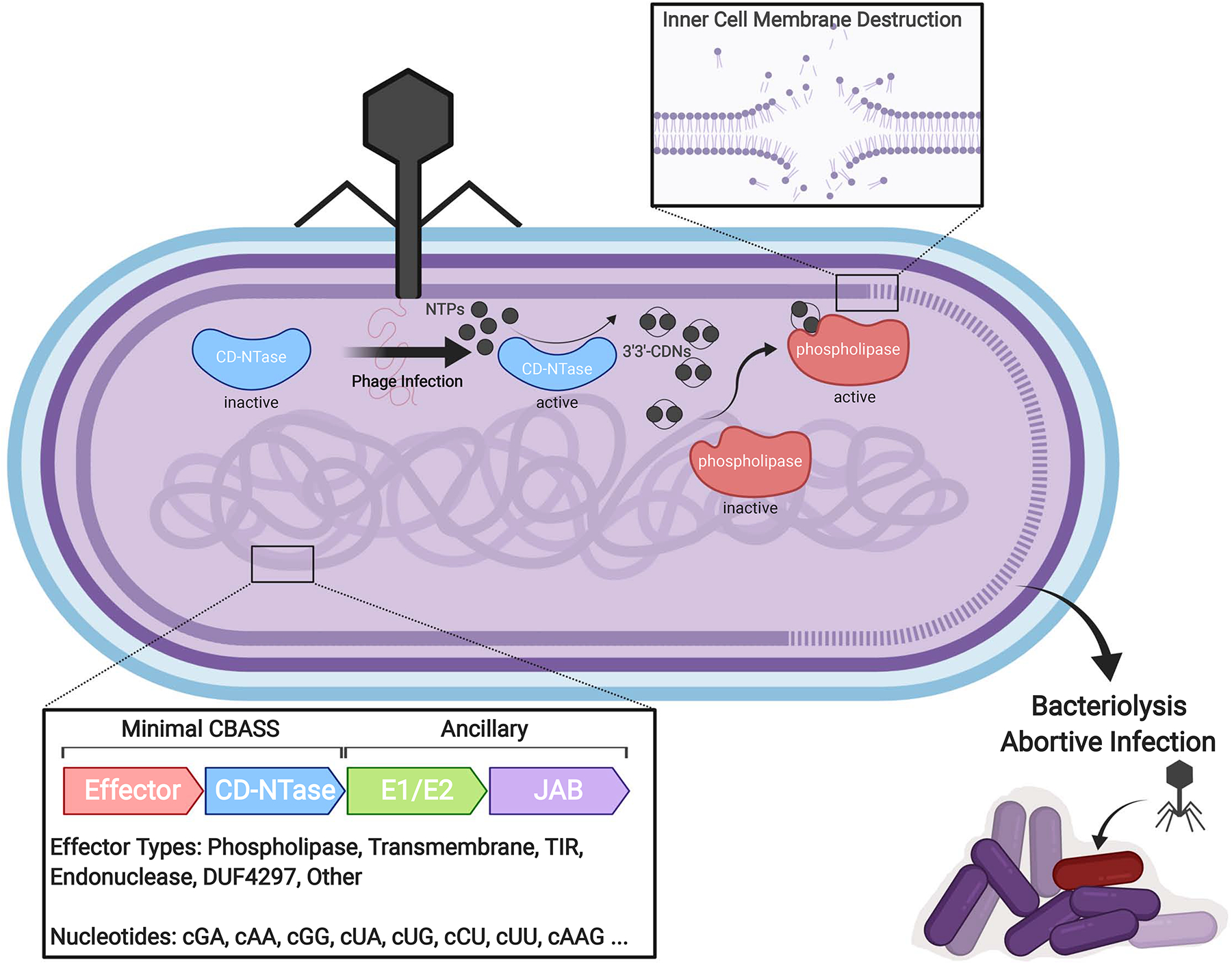

Figure 1: Overview of CBASS Signaling.

Following bacteriophage infection, activation of CD-NTases results in the production of diverse cyclic oligonucleotide species (cNNs or cNNNs, where N is any NMP) including 3’3’-CDNs. Binding of 3’3’-CDNs to a latent phospholipase results in its activation and the subsequent hydrolysis of the bacterial inner cell membrane. Dissolution of the inner membrane results in bacteriolysis, abortive infection, and ultimately protection of the larger bacterial community. Alternative CBASS effectors include endonucleases, transmembrane effectors, Toll Interleukin Receptor (TIR)-like effectors, domains of unknown function (DUFs), among others, although these are less well characterized.

cGAS-STING-Mediated Innate Immune Responses

As CD-NTase-based innate immune systems made their way into eukaryotes, they increasingly became specialized to detect foreign nucleic acid species as is the case for cGAS, a double-stranded (ds)DNA sensor, and its homologue 2’−5’ oligo-adenylate synthase (OAS), a dsRNA sensor [4, 9]. Upon engaging foreign or mislocalized self dsDNA species, cGAS oligomerizes and forms phase-separated droplet-like structures that function as ‘microreactors’ for the production of 2’3’-cGAMP [24–27]. This ultimately activates the ER-resident, transmembrane effector STING (also known as TMEM173, MITA, ERIS, and MPYS) [4, 5, 21, 22]. Structurally, STING is comprised of an N-terminal four-pass transmembrane domain followed by a cytosolic CDN binding domain (CBD) and a loosely structured C-terminal tail (CTT) [21]. In addition to binding 2’3’-cGAMP, STING can also recognize 3’3’-CDNs of bacterial origin including 3’3’-cGAMP, 3’3’-c-di-AMP, and 3’3’-c-di-GMP, albeit with reduced affinities; pyrimidine-containing CDNs appear to be much weaker inducers of STING-mediated responses [7, 9, 15, 23].

Unlike in prokaryotes where CDNs promote anti-phage immunity at the post-translational level, in metazoans CDN-mediated activation of STING fosters innate anti-microbial immunity through both post-translational and transcriptional responses. In the inactive state, STING is held in an auto-inhibited state by its CTTs [28]. Upon engaging CDNs, the CTTs of STING are released thereby exposing a polymerization interface that triggers the formation of STING homo-oligomers, which are stabilized further by intermolecular disulfide bonds [28, 29]. Activated STING eventually traffics to a perinuclear compartment where exposure of the CTTs subsequently facilitates the recruitment, activation, and oligomerization of the kinase, Tank-binding kinase 1 (TBK1) [30, 31]. Finally, the phosphorylation of STING on its CTT at a conserved motif by TBK1 recruits the transcription factor, Interferon Regulatory Factor 3 (IRF3), resulting in its subsequent phosphorylation and activation [30, 31]. IRF3 then dimerizes and translocates to the nucleus where it induces the expression of Type I Interferons and other innate immune gene programs in order to restrict viral replication and spread (Figure 2).

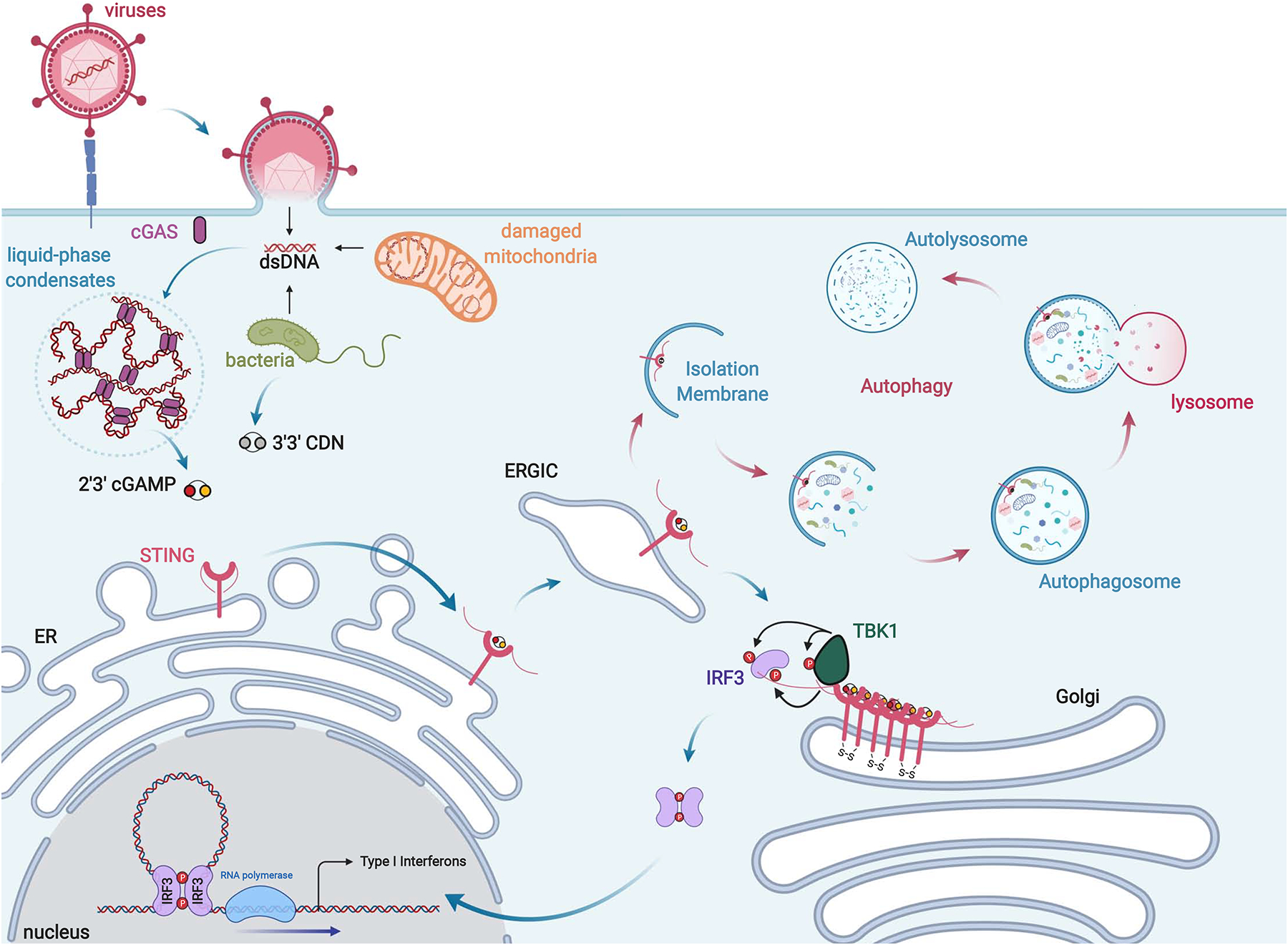

Figure 2: Schematic of the cGAS-cGAMP-STING Signaling Axis.

Accumulation of pathogenic or mislocalized self dsDNA species in the host cell cytosol activates cGAS, resulting in the formation of cGAS-DNA liquid-phase condensates and the production of 2’3’-cGAMP. Binding of 2’3’-cGAMP or 3’3’-CDNs from bacterial sources to STING results in its activation culminating in STING oligomerization and translocation to the perinuclear Golgi. There STING recruits the kinase TBK1 to the transcription factor IRF3 via its C-terminal tails ultimately resulting in IRF3 phosphorylation, dimerization, and nuclear translocation. In the nucleus IRF3 induces Type I Interferon antiviral gene programs to foster an antiviral state. In addition, STING can traffic to the ER-Golgi Intermediate Compartment (ERGIC) where it promotes the formation of autophagosomes to remove microbial pathogens from the cytosol through autophagy.

As mentioned above, cGAS-STING signaling systems in eukaryotes can be found as far back as early metazoans including the sea anemone, N. vectensis [14]. Interestingly, nvSTING was shown to lack the CTT domain required for signaling by TBK1, hinting at the possibility of interferon-independent functions of the CDN-STING axis [14, 32, 33]. It is now apparent that this evolutionarily ancient function of STING is the transcription-independent induction of autophagy, a process that allows the cell to remove cytosolic pathogens including viruses and bacteria [33]. Indeed, STING-induced autophagy is sufficient to promote the clearance of cytosolic DNA and herpes-simplex virus-1 (HSV-1); interestingly, full-length STING displays a much stronger anti-viral activity, suggesting that interferons may cooperate with autophagy to restrict viral infection (Figure 2) [33].

In addition to inducing autophagy, STING is a functionally plastic immune-signaling scaffold, the downstream signaling specificity of which can be modified through discrete signaling modules linearly organized along its CTT [34]. Interestingly, the STING-CTT domains found in higher vertebrates only contain modules for recruiting TBK1 and IRF3 and, thus, inducing Type I Interferons [34]. On the other hand, the CTT of STING from ray-finned fish has undergone an expansion to include modules to recruit and activate TNF Receptor Associated Factor 6 (TRAF6) in order to promote signaling by Nuclear Factor Kappa-light-chain-enhancer of activated B cells (NF-κB), a transcription factor that induces the expression of pro-inflammatory cytokines [34]. It has been postulated that acquisition of the TRAF6-module may have provided a strong selective advantage in ray-finned fish, perhaps against a pathogen that is not well controlled by Type I Interferons [34]. It remains to be understood why higher vertebrates including humans lack this signaling module.

2’3’-cGAMP Transporters and Phosphodiesterases

One advantage of second messenger signaling systems is that they allow for the amplification of input signals. In higher eukaryotes, this is of particular significance as cyclic dinucleotides can potentially function as ‘alarmones’ or ‘immunotransmitters’ to signal the threat of infection to neighboring cells. Indeed, 2’3’-cGAMP can be transferred to neighboring ‘bystander’ cells through gap-junctions as well as by being packaged into virions [35–37]. In addition to direct transfer, 2’3’-cGAMP can also be secreted into the extracellular milieu where it can be sensed by patrolling immune cells [38, 39]. This was recently shown to be important for restricting tumor growth in vivo through the activation of tumor-associated natural killer (NK) and dendritic cells [38–39]. While the mechanism of 2’3’-cGAMP export is still unclear, the reduced folate carrier, also known as SLC19A1, moonlights as an importer of CDNs in human immune cells [40, 41]. SLC19A1 appears to indiscriminately transport all CDNs tested, and this may be of importance for the field of tumor immunotherapy where non-hydrolyzable CDNs are currently being developed and tested [40, 41]. Interestingly, SLC19A1 does not appear to be the sole CDN transporter as SLC19A1-deficient cells can still respond to exogenous CDNs, albeit to a lesser extent [40, 41]. Follow-up studies will be necessary to identify the other CDN transporter(s) and to elucidate the role (if any) of cGAMP transport in the control of viral infection.

CDN export also provides a unifying mechanism for resolution of 2’3’-cGAMP signaling in higher metazoans [39]. Indeed, the catalytic domain of the only known mammalian 2’3’-cGAMP PDE, ectonucleotide pyrophosphatase phosphodiesterase 1 or ENPP1, is found in the extracellular space either as a transmembrane protein or as a soluble secreted factor [42, 43]. Thus, 2’3’-cGAMP secretion may function to promote infiltrating immune cell activation as well as to return 2’3’-cGAMP levels to pre-induction homeostasis through ENPP-1-mediated degradation (Figure 3) [38, 39, 42, 43]. While ENPP1 appears to be the major cGAMP hydrolase in mammals, a new class of 2’3’-cGAMP-selective phosphodiesterases was recently identified in some lower metazoans. These enzymes were initially identified in mammalian poxviruses and were hence given the name poxvirus immune nucleases or poxins [44]. Subsequent bioinformatic analysis then identified poxin homologues with conserved 2’3’-cGAMP hydrolase activity in the genomes of insects, particularly moths and butterflies [44]. Interestingly, poxin homologues can also be found in the alphabaculoviruses that infect these insect hosts, raising the intriguing hypothesis that poxins may have been domesticated by these viruses and eventually transferred to pathogenic, mammalian viruses in order to antagonize the cGAS-STING pathway [44].

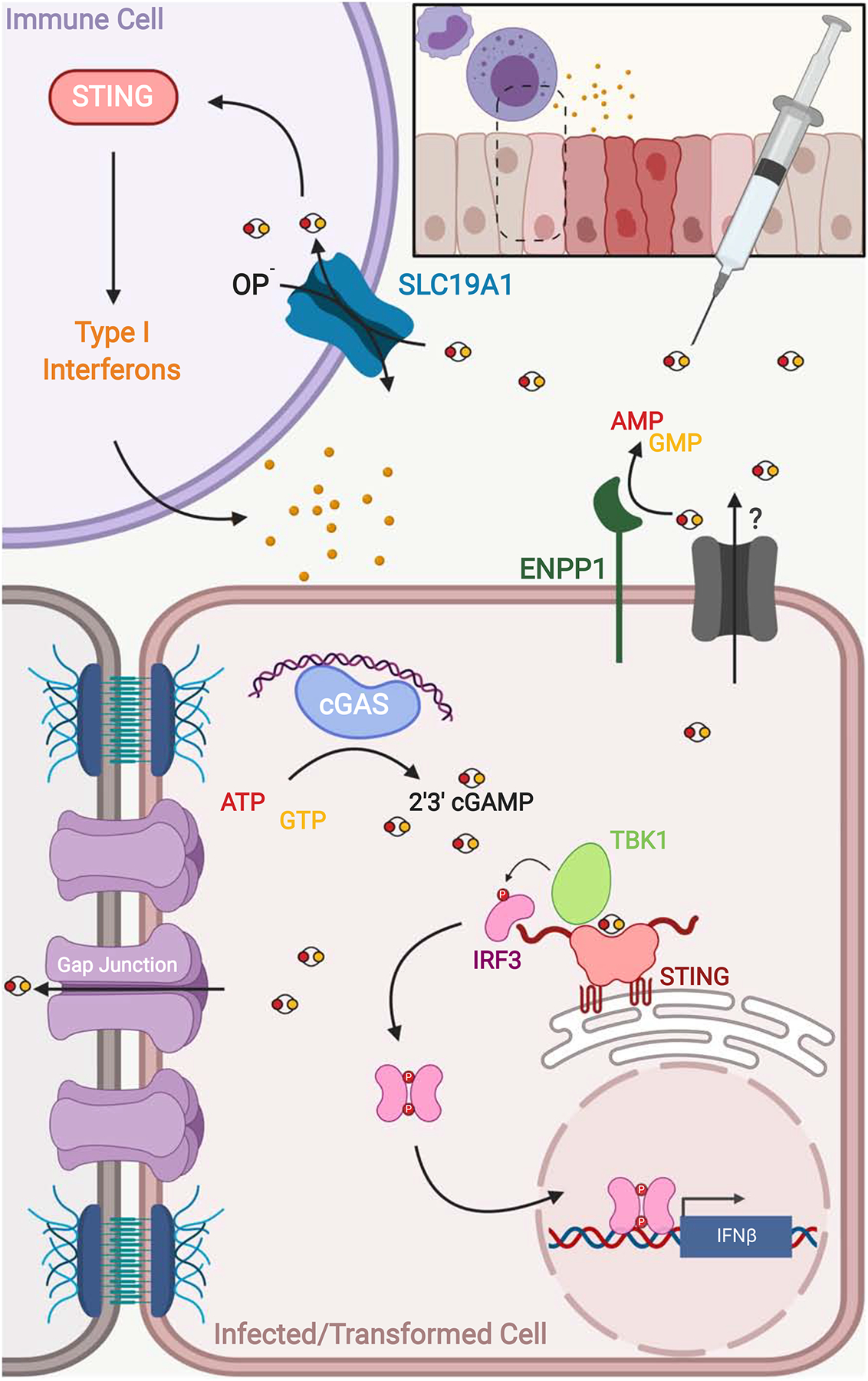

Figure 3: cGAMP Transport and Homeostasis.

Following activation by cytosolic dsDNA species, cGAS catalyzes the in-situ formation of 2’3’-cGAMP resulting in STING and Type I Interferon activation within the infected or transformed cell. Transfer of 2’3’-cGAMP to neighboring bystander cells via gap junctions propagates STING-mediated signaling across the infected or damaged tissue. 2’3’-cGAMP levels can return to their pre-induction state through secretion via an unidentified transporter followed by ENPP-1 mediated hydrolysis. Secreted or exogenous CDNs can also be taken up by immune cells via a folate/organic phosphate (OP−) antiporter, SLC19A1, to further amplify the innate immune response.

Viral Evasion of cGAMP-STING Signaling

While cGAMP is critical for controlling virus infection, many viruses appear to have developed countermeasures including degradation mechanisms to evade this signaling system, highlighting the evolutionary arms race that exists between viruses and their hosts [45–54]. One such strategy, commonly employed by herpesviruses, is to limit cGAMP production by inhibiting cGAS activation [47–50]. This can be accomplished through the use of tegument proteins that directly bind to cGAS and trigger its dissociation from viral DNA as is the case for Kaposi-sarcoma herpesvirus and human cytomegalovirus [47–49]. Interestingly, HSV-1 has developed a sophisticated strategy for the species-specific inhibition of cGAS-signaling involving the tegument protein, UL37 [50]. Mechanistically, UL37 was found to possess deamidase activity, which allows it to inactivate cGAS through the deamidation of a single asparagine residue on its activation loop [50]. Interestingly, UL37 can deamidate mouse and human cGAS isoforms but not isoforms from non-human primates, again underscoring how evolutionary arms races may specify host tropism [50]. Thus, direct targeting of cGAS appears to be a common strategy employed by herpesviruses to evade host DNA-sensing pathways. While we aimed to highlight some of the recent publications and common themes, this is certainly not an exhaustive list of the strategies used by DNA viruses to evade cGAMP-STING signaling, some of which involve directly antagonizing STING (for a more detailed review on this topic please see Ni et. al.) [51–54]. It is possible that the mechanisms for bystander cell activation discussed above may have developed out of a necessity to counteract these viral immune evasion strategies in infected cells. It will be interesting to see whether bacteriophages may employ similar mechanisms for evading CBASS-mediated immunity, perhaps through use of poxin homologues.

Concluding Remarks

In summary, CD-NTase signaling networks constitute an evolutionarily ancient form of innate anti-viral defense originating as prokaryotic anti-phage systems. It is possible that as bacteria fused with archaea they brought along these anti-viral defense mechanisms ultimately giving rise to the cGAS-STING pathway in metazoans as we know it today. Although pathogens have developed strategies to evade these signaling systems, sensing of foreign and damaged- or misplaced-self DNA species by the enzyme cGAS has proven to be essential for the control of pathogen infection and tumorigenesis, respectively, both in vitro and in vivo. Although much is now known about the mechanisms of cGAS and STING activation, as cGAS indiscriminately binds DNA, a more thorough understanding of self versus non-self discrimination by cGAS will be necessary. Several recent studies have begun to shed light on this process, which will likely be an active area of research over the coming years [55–59]. Indeed, cyclic dinucleotides are a rapidly expanding class of signaling molecules in all domains of life with many exciting biological roles to be uncovered ahead.

Acknowledgements

We thank Maureen Thomason and Rochelle Glover for critically reading and editing the manuscript. All of the figures used in this manuscript were created with BioRender.com. S.A.Z. is supported by the Seattle ARCS foundation as well as grants from the University of Washington/Fred Hutchinson Cancer Research Center Viral Pathogenesis Training Program (2T32AI083203), the University of Washington Medical Scientist Training Program (2T32GM007266), and a Ruth L. Kirschstein Predoctoral Fellowship (1F30CA239659-01A1). JJW is supported by the Pew Scholars Program in the Biomedical Sciences, the Lupus Research Alliance, and National Institutes of Health Grants 1R01AI139071-01A1, 5R01AI116669-05, and 1R21AI137758-01,

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

Conflict of Interest Statement

The authors declare no competing financial or personal interests.

Declaration of interests

The authors declare that they have no known competing financial interests or personal relationships that could have appeared to influence the work reported in this paper.

References and Recommended Reading

Papers of particular interest, published within the period of review, have been highlighted as follows:

* of special interest

** of outstanding interest

- 1.Janeway CA, Medzhitov R: Innate Immune Recognition. Annual Review of Immunology 2002, 20:197–216. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.McWhirter SM, Barbalat R, Monroe KM, Fontana MF, Hyodo M, Joncker NT, Ishii KJ, Akira S, Colonna M, Chen ZJ, et al. : A host type I interferon response is induced by cytosolic sensing of the bacterial second messenger cyclic-di-GMP. The Journal of Experimental Medicine 2009, 206:1899–1911. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Woodward JJ, Iavarone AT, Portnoy DA: c-di-AMP Secreted by Intracellular Listeria monocytogenes Activates a Host Type I Interferon Response. Science 2010, 328:1703. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Sun L, Wu J, Du F, Chen X, Chen ZJ: Cyclic GMP-AMP Synthase Is a Cytosolic DNA Sensor That Activates the Type I Interferon Pathway. Science 2013, 339:786. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Wu J, Sun L, Chen X, Du F, Shi H, Chen C, Chen ZJ: Cyclic GMP-AMP Is an Endogenous Second Messenger in Innate Immune Signaling by Cytosolic DNA. Science 2013, 339:826. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Cohen D, Melamed S, Millman A, Shulman G, Oppenheimer-Shaanan Y, Kacen A, Doron S, Amitai G, Sorek R: Cyclic GMP–AMP signalling protects bacteria against viral infection. Nature 2019, doi: 10.1038/s41586-019-1605-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; ** Building on the work of Refs. [9] and [19], this study determined that CD-NTases are part of an anti-phage defense system in prokaryotes that confers resistance to a broad range of bacteriophages. This study also identified homologues of STING in prokaryotes, providing a potential mechanism for the acquisition of cGAS-STING signaling systems in metazoans.

- 7.Krasteva PV, Sondermann H: Versatile modes of cellular regulation via cyclic dinucleotides. Nature Chemical Biology 2017, 13:350. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Davies BW, Bogard RW, Young TS, Mekalanos JJ: Coordinated Regulation of Accessory Genetic Elements Produces Cyclic Di-Nucleotides for V. cholerae Virulence. Cell 2012, 149:358–370. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Whiteley AT, Eaglesham JB, de Oliveira Mann CC, Morehouse BR, Lowey B, Nieminen EA, Danilchanka O, King DS, Lee ASY, Mekalanos JJ, et al. : Bacterial cGAS-like enzymes synthesize diverse nucleotide signals. Nature 2019, 567:194–199. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; ** This study identified a broad family of cGAS/DncV-like nucleotidyltransferases (CD-NTases) capable of synthesizing a wide variety of cyclic dinucleotides, including pyrimidine-containing CDNs, which had never previously been observed in nature. The authors also identified a novel cyclic trinucleotide species cyclic AMP-AMP-GMP. It will be interesting to see what biological processes are regulated by these novel nucleotide signaling molecules over the coming years.

- 10.Ablasser A, Goldeck M, Cavlar T, Deimling T, Witte G, Röhl I, Hopfner K-P, Ludwig J, Hornung V: cGAS produces a 2′−5′-linked cyclic dinucleotide second messenger that activates STING. Nature 2013, 498:380. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Zhang X, Shi H, Wu J, Zhang X, Sun L, Chen C, Chen ZJ: Cyclic GMP-AMP Containing Mixed Phosphodiester Linkages Is An Endogenous High-Affinity Ligand for STING. Molecular Cell 2013, 51:226–235. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Diner EJ, Burdette DL, Wilson SC, Monroe KM, Kellenberger CA, Hyodo M, Hayakawa Y, Hammond MC, Vance RE: The Innate Immune DNA Sensor cGAS Produces a Noncanonical Cyclic Dinucleotide that Activates Human STING. Cell Reports 2013, 3:1355–1361. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Burroughs AM, Zhang D, Schäffer DE, Iyer LM, Aravind L: Comparative genomic analyses reveal a vast, novel network of nucleotide-centric systems in biological conflicts, immunity and signaling. Nucleic Acids Research 2015, 43:10633–10654.* [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Kranzusch PJ, Wilson SC, Lee ASY, Berger JM, Doudna JA, Vance RE: Ancient Origin of cGAS-STING Reveals Mechanism of Universal 2′,3′ cGAMP Signaling. Molecular Cell 2015, 59:891–903. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Wang C, Sinn M, Stifel J, Heiler AC, Sommershof A, Hartig JS: Synthesis of All Possible Canonical (3′–5′-Linked) Cyclic Dinucleotides and Evaluation of Riboswitch Interactions and ImmuneStimulatory Effects. Journal of the American Chemical Society 2017, 139:16154–16160. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Nelson JW, Breaker RR: The lost language of the RNA World. Science Signaling 2017, 10:eaam8812. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Ye Q, Lau RK, Mathews IT, Watrous JD, Azimi CS, Jain M, Corbett KD: HORMA domain proteins and a Pch2-like ATPase regulate bacterial cGAS-like enzymes to mediate bacteriophage immunity. bioRxiv 2019, doi: 10.1101/694695 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Gao J, Tao J, Liang W, Zhao M, Du X, Cui S, Duan H, Kan B, Su X, Jiang Z: Identification and characterization of phosphodiesterases that specifically degrade 3′3′-cyclic GMP-AMP. Cell Research 2015, 25:539–550. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Severin GB, Ramliden MS, Hawver LA, Wang K, Pell ME, Kieninger AK, Khataokar A, O’Hara BJ, Behrmann LV, Neiditch MB, et al. : Direct activation of a phospholipase by cyclic GMP-AMP in El Tor Vibrio cholerae. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences 2018, 115:E6048. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Lau RK, Ye Q, Patel L, Berg KR, Mathews IT, Watrous JD, Whiteley AT, Lowey B, Mekalanos JJ, Kranzusch PJ, Jain M, Corbett KD: Structure and mechanism of a cyclic trinucleotide-activated bacterial endonuclease mediating bacteriophage immunity. bioRxiv 2019, doi: 10.1101/694703 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Ishikawa H, Barber GN: STING is an endoplasmic reticulum adaptor that facilitates innate immune signalling. Nature 2008, 455:674–678. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Ishikawa H, Ma Z, Barber GN: STING regulates intracellular DNA-mediated, type I interferondependent innate immunity. Nature 2009, 461:788–792. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Burdette DL, Monroe KM, Sotelo-Troha K, Iwig JS, Eckert B, Hyodo M, Hayakawa Y, Vance RE: STING is a direct innate immune sensor of cyclic di-GMP. Nature 2011, 478:515–518. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Zhang X, Wu J, Du F, Xu H, Sun L, Chen Z, Brautigam CA, Zhang X, Chen ZJ: The Cytosolic DNA Sensor cGAS Forms an Oligomeric Complex with DNA and Undergoes Switch-like Conformational Changes in the Activation Loop. Cell Reports 2014, 6:421–430. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Andreeva L, Hiller B, Kostrewa D, Lässig C, de Oliveira Mann CC, Jan Drexler D, Maiser A, Gaidt M, Leonhardt H, Hornung V, et al. : cGAS senses long and HMGB/TFAM-bound U-turn DNA by forming protein–DNA ladders. Nature 2017, 549:394–398. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Du M, Chen ZJ: DNA-induced liquid phase condensation of cGAS activates innate immune signaling. Science 2018, 361:704. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; * This study in combination with Ref. [27] is highlighted because it demonstrates that cGAS undergoes switch-like liquid-phase separation upon binding to DNA, resulting in the formation of ‘cellular factories’ required for optimum cGAMP production. Furthermore, liquid-phase separation only occurred at threshold concentrations of cytoplasmic DNA, suggesting that this may be an important regulatory step in cGAS activation with important implications for autoimmunity.

- 27.Xie W, Lama L, Adura C, Tomita D, Glickman JF, Tuschl T, Patel DJ: Human cGAS catalytic domain has an additional DNA-binding interface that enhances enzymatic activity and liquid-phase condensation. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences 2019, doi: 10.1073/pnas.1905013116. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; * This study in combination with Ref. [26] is highlighted because it demonstrates that cGAS undergoes switch-like liquid-phase separation upon binding to DNA, resulting in the formation of ‘cellular factories’ required for optimum cGAMP production. Furthermore, liquid-phase separation only occurred at threshold concentrations of cytoplasmic DNA, suggesting that this may be an important regulatory step in cGAS activation with important implications for autoimmunity.

- 28.Ergun SL, Fernandez D, Weiss TM, Li L: STING Polymer Structure Reveals Mechanisms for Activation, Hyperactivation, and Inhibition. Cell 2019, 178:290–301.e10. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Shang G, Zhang C, Chen ZJ, Bai X, Zhang X: Cryo-EM structures of STING reveal its mechanism of activation by cyclic GMP–AMP. Nature 2019, 567:389–393. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; * This paper in combination with Refs. [30] and [31] is highlighted because it provides novel structural insights into the mechanisms of STING activation.

- 30.Zhang C, Shang G, Gui X, Zhang X, Bai X, Chen ZJ: Structural basis of STING binding with and phosphorylation by TBK1. Nature 2019, 567:394–398. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; * This paper in combination with Refs. [29] and [31] is highlighted because it provides novel structural insights into the mechanisms of STING activation.

- 31.Zhao B, Du F, Xu P, Shu C, Sankaran B, Bell SL, Liu M, Lei Y, Gao X, Fu X, et al. : A conserved PLPLRT/SD motif of STING mediates the recruitment and activation of TBK1. Nature 2019, 569:718–722. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; * This paper in combination with Refs. [29] and [30] is highlighted because it provides novel structural insights into the mechanisms of STING activation.

- 32.Margolis SR, Wilson SC, Vance RE: Evolutionary Origins of cGAS-STING Signaling. Trends in Immunology 2017, 38:733–743. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Gui X, Yang H, Li T, Tan X, Shi P, Li M, Du F, Chen ZJ: Autophagy induction via STING trafficking is a primordial function of the cGAS pathway. Nature 2019, 567:262–266. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; ** This study demonstrated that the ancient role of STING as an immune signaling molecule is the induction of autophagy and that this could be functionally decoupled from activation of TBK1 and Interferon induction.

- 34.de Oliveira Mann CC, Orzalli MH, King DS, Kagan JC, Lee ASY, Kranzusch PJ: Modular Architecture of the STING C-Terminal Tail Allows Interferon and NF-κB Signaling Adaptation. Cell Reports 2019, 27:1165–1175.e5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; * This study is highlighted because it demonstrates the remarkable signaling plasticity of STING, which functions as an organizing center through the modularity of its C-terminal tail.

- 35.Ablasser A, Schmid-Burgk JL, Hemmerling I, Horvath GL, Schmidt T, Latz E, Hornung V: Cell intrinsic immunity spreads to bystander cells via the intercellular transfer of cGAMP. Nature 2013, 503:530. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Gentili M, Kowal J, Tkach M, Satoh T, Lahaye X, Conrad C, Boyron M, Lombard B, Durand S, Kroemer G, et al. : Transmission of innate immune signaling by packaging of cGAMP in viral particles. Science 2015, 349:1232–1236. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Bridgeman A, Maelfait J, Davenne T, Partridge T, Peng Y, Mayer A, Dong T, Kaever V, Borrow P, Rehwinkel J: Viruses transfer the antiviral second messenger cGAMP between cells. Science 2015, 349:1228–1232. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Marcus A, Mao AJ, Lensink-Vasan M, Wang L, Vance RE, Raulet DH: Tumor-Derived cGAMP Triggers a STING-Mediated Interferon Response in Non-tumor Cells to Activate the NK Cell Response. Immunity 2018, 49:754–763.e4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; * This study demonstrated that cyclic dinucleotides produced by transformed cells are transferred to tumor-associated Natural Killer (NK) cells in vivo in order to facilitate immune-mediated tumor clearance.

- 39.Carozza JA, Boehnert V, Shaw KE, Nguyen KC, Skariah G, Brown JA, Rafat M, von Eyben R, Graves EE, Glenn JS, et al. : 2’3’-cGAMP is an immunotransmitter produced by cancer cells and regulated by ENPP1. bioRxiv 2019, doi: 10.1101/539312 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Ritchie C, Cordova AF, Hess GT, Bassik MC, Li L: SLC19A1 Is an Importer of the Immunotransmitter cGAMP. Molecular Cell 2019, 75:372–381.e5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; ** This study in combination with Ref. [41] is highlighted because it identified the major import mechanism of cyclic dinucleotides in immune cells. This may be of important therapeutic consequences in the context of cancer immunotherapy or treatment of autoimmune disorders.

- 41.Luteijn RD, Zaver SA, Gowen BG, Wyman SK, Garelis NE, Onia L, McWhirter SM, Katibah GE, Corn JE, Woodward JJ, et al. : SLC19A1 transports immunoreactive cyclic dinucleotides. Nature 2019, 573:434–438. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; ** This study in combination with Ref. [40] is highlighted because it identified the major import mechanism of cyclic dinucleotides in immune cells. This may be of important therapeutic consequences in the context of cancer immunotherapy or treatment of autoimmune disorders.

- 42.Li L, Yin Q, Kuss P, Maliga Z, Millán JL, Wu H, Mitchison TJ: Hydrolysis of 2′3′-cGAMP by ENPP1 and design of nonhydrolyzable analogs. Nature Chemical Biology 2014, 10:1043. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Kato K, Nishimasu H, Oikawa D, Hirano S, Hirano H, Kasuya G, Ishitani R, Tokunaga F, Nureki O: Structural insights into cGAMP degradation by Ecto-nucleotide pyrophosphatase phosphodiesterase 1. Nature Communications 2018, 9:4424. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Eaglesham JB, Pan Y, Kupper TS, Kranzusch PJ: Viral and metazoan poxins are cGAMP-specific nucleases that restrict cGAS–STING signalling. Nature 2019, 566:259–263. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; ** This study identified a novel class of 2’3-cGAMP selective phosphodiesterases encoded by most mammalian poxviruses in order to evade host innate immune detection. The authors identified homologs of these enzymes in the genomes of insects and the alphabaculoviruses that infect them, providing a possible evolutionary mechanism for acquisition of these enzymes by poxviruses.

- 45.Gao D, Wu J, Wu Y-T, Du F, Aroh C, Yan N, Sun L, Chen ZJ: Cyclic GMP-AMP Synthase Is an Innate Immune Sensor of HIV and Other Retroviruses. Science 2013, 341:903–906. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Li X-D, Wu J, Gao D, Wang H, Sun L, Chen ZJ: Pivotal Roles of cGAS-cGAMP Signaling in Antiviral Defense and Immune Adjuvant Effects. Science 2013, 341:1390–1394. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Wu J, Li W, Shao Y, Avey D, Fu B, Gillen J, Hand T, Ma S, Liu X, Miley W, et al. : Inhibition of cGAS DNA Sensing by a Herpesvirus Virion Protein. Cell Host & Microbe 2015, 18:333–344. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Zhang G, Chan B, Samarina N, Abere B, Weidner-Glunde M, Buch A, Pich A, Brinkmann MM, Schulz TF: Cytoplasmic isoforms of Kaposi sarcoma herpesvirus LANA recruit and antagonize the innate immune DNA sensor cGAS. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences 2016, 113:E1034–E1043. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Huang Z-F, Zou H-M, Liao B-W, Zhang H-Y, Yang Y, Fu Y-Z, Wang S-Y, Luo M-H, Wang Y-Y: Human Cytomegalovirus Protein UL31 Inhibits DNA Sensing of cGAS to Mediate Immune Evasion. Cell Host & Microbe 2018, 24:69–80.e4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Zhang J, Zhao J, Xu S, Li J, He S, Zeng Y, Xie L, Xie N, Liu T, Lee K, et al. : Species-Specific Deamidation of cGAS by Herpes Simplex Virus UL37 Protein Facilitates Viral Replication. Cell Host & Microbe 2018, 24:234–248.e5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; * This paper demonstrated a novel mechanism by which the herpesvirus (HSV-1) cripples cGAMPsignaling, through the deamidation of the DNA-sensor cGAS. Interestingly, UL37 was also shown by the same group to deamidate the RNA-sensor RIG-I, suggesting that protein deamidation may serve as a bet-hedging strategy to evade host innate immunity.

- 51.Ma Z, Jacobs SR, West JA, Stopford C, Zhang Z, Davis Z, Barber GN, Glaunsinger BA, Dittmer DP, Damania B: Modulation of the cGAS-STING DNA sensing pathway by gammaherpesviruses. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences 2015, 112:E4306–E4315. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Lau L, Gray EE, Brunette RL, Stetson DB: DNA tumor virus oncogenes antagonize the cGAS-STING DNA-sensing pathway. Science 2015, 350:568. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Hancks DC, Hartley MK, Hagan C, Clark NL, Elde NC: Overlapping Patterns of Rapid Evolution in the Nucleic Acid Sensors cGAS and OAS1 Suggest a Common Mechanism of Pathogen Antagonism and Escape. PLOS Genetics 2015, 11:e1005203. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Ni G, Ma Z, Damania B: cGAS and STING: At the intersection of DNA and RNA virus-sensing networks. PLOS Pathogens 2018, 14:e1007148. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Zhou W, Whiteley AT, de Oliveira Mann CC, Morehouse BR, Nowak RP, Fischer ES, Gray NS, Mekalanos JJ, Kranzusch PJ: Structure of the Human cGAS–DNA Complex Reveals Enhanced Control of Immune Surveillance. Cell 2018, 174:300–311.e11. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Barnett KC, Coronas-Serna JM, Zhou W, Ernandes MJ, Cao A, Kranzusch PJ, Kagan JC: Phosphoinositide Interactions Position cGAS at the Plasma Membrane to Ensure Efficient Distinction between Self- and Viral DNA. Cell 2019, 176:1432–1446.e11. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; ** vThis study demonstrated that in the resting-state cGAS is tethered to the plasma membrane through interactions with phosphoinositide species, thereby providing a possible mechanism for how cGAS is sequestered from self-DNA in the nucleus.

- 57.Liu H, Zhang H, Wu X, Ma D, Wu J, Wang L, Jiang Y, Fei Y, Zhu C, Tan R, et al. : Nuclear cGAS suppresses DNA repair and promotes tumorigenesis. Nature 2018, 563:131–136. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Gentili M, Lahaye X, Nadalin F, Nader GPF, Puig Lombardi E, Herve S, de Silva NS, Rookhuizen DC, Zueva E, Goudot C, et al. : The N-Terminal Domain of cGAS Determines Preferential Association with Centromeric DNA and Innate Immune Activation in the Nucleus. Cell Reports 2019, 26:2377–2393.e13. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Zierhut C, Yamaguchi N, Paredes M, Luo J-D, Carroll T, Funabiki H: The Cytoplasmic DNA Sensor cGAS Promotes Mitotic Cell Death. Cell 2019, 178:302–315.e23. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]