Abstract

Background.

Metabolic and bariatric surgery (MBS) is a safe and effective treatment choice for severe obesity. Yet only about 50% of those referred to MBS complete the procedure. Studies show that racial minority groups are less likely than non-Hispanic Whites to complete MBS despite having higher rates of severe obesity and comorbidities.

Objectives.

To conduct a qualitative study to determine facilitators and challenges to racially diverse patients completing MBS based on the four socioecological model domains (intrapersonal, interpersonal, organization/clinical interaction, societal/environmental).

Setting.

One university-based surgery practice serving a racially diverse patient population.

Methods.

Focus groups and in-depth interviews were conducted (Spring 2019) among patients (N=24, 70% female, 50% non-Hispanic black, 4% Hispanic) who completed MBS over the past year. Social support members were also included (N= 7). Grand tour questions were organized by the four socioecological model domains and within the context of MBS completion. Data was audio-recorded, transcribed and coded. A thematic analysis combining a deductive and inductive approach was conducted. Codes were analyzed using Dedoose to identify themes/sub-themes.

Results.

Ten themes and 15 sub-themes were identified. Key intra/interpersonal facilitators to MBS completion included social support systems, primary care physician (PCP) support of MBS, comorbidity resolution, discrimination experiences, and mobility improvements. Key community/environment themes associated with post-MBS sustained weight loss included community support groups and access to healthy foods and exercise facilities. No themes/sub-themes varied by race.

Conclusions.

Educating PCPs and social support networks about the benefits of MBS could improve utilization rates. MBS patients have a desire to have their communities provide resources to support their post-operative success.

Keywords: metabolic, bariatric, surgery, race, disparity, utilization

Introduction

Metabolic and bariatric surgery (MBS) has become a safe and medically effective treatment choice for severe obesity (body mass index [BMI] > 40 kg/m2 or > 35 kg/m2 with > 1 comorbidity) (1–6), type 2 diabetes (T2D) (7–15) and other cardiometabolic risk factors, when conventional lifestyle change methods (decreased caloric intake, increased activity levels) are unsuccessful (16–27). In fact, a large body of evidence including 11 randomized clinical trials (28) indicate that MBS is a highly effective procedure that can also reduce blood sugar levels below diabetic thresholds. Based on this strong evidence, MBS has been endorsed as a standardized treatment option for people with diabetes, including those who suffer from obesity and fail to respond to conventional treatment, in a Joint Statement endorsed by 45 professional organizations (28). Moreover, patients with obesity who complete MBS live higher quality and longer lives than those who do not complete the procedure (29–31).

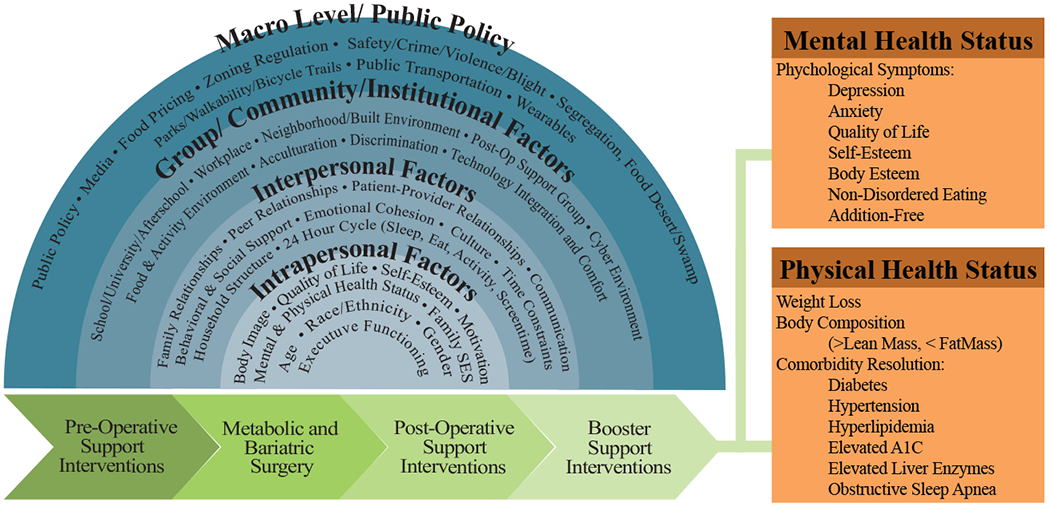

Yet, despite (1) an increase in the number of MBS procedures performed in the United States annually over the past decade and (2) the fact that many people express interest and thus voluntarily attend MBS information sessions, and schedule initial MBS appointments, only about 50% of referred or eligible persons for MBS actually complete the procedure (32–36). Specifically, Hispanics and non-Hispanic Blacks (NHB) are significantly less likely than non-Hispanic Whites (NHW) to complete MBS despite having higher rates of severe obesity as well as obesity-related comorbidities (e.g.T2D, cardiovascular disease) versus NHW (32,34,36). Reasons for this high noncompletion rate among racial minority groups referred for MBS is largely unknown. With an increasing number of insurance carriers now covering MBS, including Medicaid when medically indicated, absence of medical insurance does not fully explain the racial discrepancies in MBS (32–36). Indeed, several studies have found that the highest proportion of patients who do not follow through with MBS do so for “unknown” reasons. The success of committing to, and following through with MBS must take into consideration not only intrapersonal (psychosocial, behavioral) factors but social, group, cultural, organizational, community, clinical and other environmental interaction aspects as well. Socioecological models can reframe behavior often seen as the “responsibility” of the individual to include required change at the clinical and community levels to support post-MBS patients and their lifestyle changes (Figure 1). As our nation becomes more diverse, recognition of how cultural differences may impact different types of health-related behaviors is important. This qualitative study examines whether these four socioecological domains can provide additional insights about utilization of MBS across diverse racial groups.

Figure 1.

Socioecological Model Constructs to Inform MBS Completion Rates

Materials and Methods

Procedures

Potential study participants were recruited from one large academic/university-based multidisciplinary surgery clinic during post-MBS support group meetings hosted by a dietician. Recruitment was conducted from March 2019 to July 2019. Out of a total of 37 participants who stated they were interested in participating in the study, 31 enrolled (24 post MBS patients and 7 of their social support network members). A sample size of 30 has been shown to be sufficient to achieve data saturation of meta-themes, and thus no more patients were recruited after this sample size was achieved (37). Participants were contacted after the support group by a research team member and scheduled to participate in either a focus group or in-depth one-on-one interview. All focus groups were video and audio recorded, and all phone interviews were audio recorded. All participants signed an informed consent before their group or interview commenced. This study was approved by the university Institutional Review Board.

A phenomenological approach explored the various factors that influence the decision to have MBS. A semi-structured interview was conducted with participants. They were asked a series of open- and closed-ended questions pertaining to their exposure, knowledge, thoughts, concerns, and experiences related to MBS completion. A total of 11 grand tour questions were organized by interpersonal, intrapersonal, social and organizational constructs to capture each socioecological model construct. Specific questions included: “What were some of your main concerns or issues when considering having bariatric surgery for yourself?”, “Did you feel like the relationship you had with your primary care or specialist made a difference in your decision to have surgery? “Did other people effect your decision to have the surgery?” The participants social support members were asked similar grand tour questions. The questions were restated to address the family member or friend being interviewed. For example: “What were some of your concerns when your (daughter, son, sister, brother, cousin or friend) was considering having bariatric surgery?” and “How did you support him/her throughout their weight loss journey?”

Participants.

Study eligibility criteria were as follows: (a) must be 18 years of age or older; (b) consent to participate, and (c) be willing to spend at least 60 to 90 minutes responding to questions in a group setting or at least 30 to 60 minutes responding to questions individually via telephone call. All participants for the focus groups and telephone interviews were aware they would be audio or video recorded or both.

Analysis

The focus groups and telephone interviews were transcribed verbatim by researchers. A thematic analysis using a combined deductive and inductive approach were used to analyze the data. Researchers designed a codebook to structure and define thematic codes. The codes were developed based on key words and quotes mentioned in both the focus groups and interviews that were documented by researchers (authors AO, JK, QBN). Together, two graduate-level trained researchers (authors AO and JK) meticulously coded multiple transcripts to refine the codebook. Transcripts were then inputted in Dedoose and analyzed to develop themes using qualitative charts such as code co-occurrence and code application.

Results

The analytical sample included 31 participants (70% female, 48% non-Hispanic black, 48% non-Hispanic white and 4% Hispanic). Eleven participated in two focus groups, and 20 participants completed an in-depth telephone interview. Social support network members (n=7) included spouses, relatives, or friends.

A total of 10 themes and 15 sub themes were found that described key factors that contributed to participants’ decision to complete MBS (see Tables 1 and 2). Findings are summarized below and organized by the four socioecological model domains.

Table 1.

Participant Quotes, Organized by Themes and Sub-Themes and the Socioecological Framework’s Intra-and Interpersonal Domains

| Themes and Sub-Themes | Supporting Quotes |

|---|---|

| INTRAPERSONAL | |

| Theme 1. Motivation | |

| 1a. Comorbidity Resolution |

(1.0) “I was getting progressively worse health-wise because I was already pre-diabetic, HBP, cholesterol, and severe knee arthritis and that right there was the kicker for me.” – 61 year old Hispanic male (1.1) “I got rid of some pills, I got taken off of my diabetes medicine got taken off of my GERD meds ….my cholesterol meds. Which is great.” – 55 year old non-Hispanic white female (1.2) “My doctor already reduced my BP meds and we’re looking at my cholesterol medications and reducing those.” – 56 year old non-Hispanic black female” (1.3) “…I am happy that I lost what I lost and that I’m not on medication anymore. I feel better now than I ever have.” – 54 year old non-Hispanic white male |

| 1b. Mobility |

(1.4) “…because I really wanted to lose the most weight possible so that I could feel better and exercise and not be out of breath…” – 48 year old non-Hispanic black male (1.5) “The best thing is that I’m feeling better, I’m able to walk. Before it was really hard for me to walk because of my knee. This has enabled me to exercise” – 61 year old Hispanic male (1.6) “It was hard for me to just get up and get to walking. I didn’t walk. I couldn’t go up steps without being out of breath. My knees hurt, and my hips hurt and everything hurt.” – 50 year old non-Hispanic black female |

| Theme 2. Adapting to Dietary Changes | |

| 2a. Relationship With Food |

(2.0) “My biggest fear is that I love to eat! I love the smell and the taste and the experience! I am like a foodie.” – 64 year old non-Hispanic white female (2.1) “…And what foods I can eat and what I couldn’t eat, you know what changes would I have to accept.” – 50 year old non-Hispanic black female (2.2) “I still find the times when I get stressed out when I get frustrated I start looking at the fridge. At first. I know it’s more of a habit. I don’t do that now at all because physically I couldn’t.” – 45 year old non-Hispanic white male |

| Theme 3. Self-Esteem | |

| 3a. Post-MBS Improvement |

(3.0) Well my self-esteem has gotten a whole lot better since I lost weight – 50 year old non-Hispanic black female (3.1) “…I’ve learned how to love me because it’s about me loving me to live a good healthy life.” – 60 year old non-Hispanic black female (3.2) “Now her self-esteem is just really high, she’s more confident, she is more open and being herself.” – 54 year old non-Hispanic black male |

| Theme 4. Social Interactions | |

| 4a. Social Changes |

(4.0) “I guess I might be a little bit less insecure about social gatherings because you know I feel like I look better. So that might have helped that” – 63 year old non-Hispanic black female (4.1) “People listened they were more receptive of him. In crowds he was recognized whereas before he was not. He got back to dressing better. I think that helped as well because he used to be an impeccable dresser” – 63 year old non-Hispanic white female (4.2) “So I’m more active and I go out more .I dress better …I have way more confidence.” – 49 year old non-Hispanic black female |

| Theme 5. MBS-Related Concerns | |

| 5a. Health Effects |

(5.0) “Just safety and more so the after effects” – 40 year old African American male (5.1) “The pain involved.” – 50 year old non-Hispanic black female (5.2) “My family member that we know that had it a long time ago it was fairly new then. It was a long time ago like years ago and it was fairly new then and she had some complications and things like that. So just concerned about my sister having it” – 40 year old non-Hispanic black male (5.3) “Well I knew of one person some years ago that had the surgery and they were quite ill afterwards, but then I learned that the reason she was ill was because she wasn’t following directions and so that was really my only main concerns” – 56 year old non-Hispanic black female |

| INTERPERSONAL | |

| Theme 6. MBS Referral Network | |

| 6a. Family/Friends |

(6.0) “I knew about it because some of my family, my brother had it” – 61 year old Hispanic male (6.1) “I learned about that through a colleague of mine” – 55 year old non-Hispanic black female |

| Theme 7. Social Support System | |

| 7a. Pre/Post MBS |

(7.0) “Just talking to her and just letting her know if she needs anything before or after to just let me know and I’m willing to help however I can” – 40 year old non-Hispanic black male (7.1) “…and you know that I just was here at her beck and call whatever she needed and I tried to encourage her to drink a little bit, or eat something…” – 62 year old non-Hispanic black female (7.2) “He did more research than I did “Mama this will be good for you. You’ll eat better. We want you to be here a long time. You can go back to the gym. You look good, but I just think you’ll look better. My son was really on point” – 60 year old non-Hispanic black female |

| Theme 8. Discrimination | |

| 8a. Discrimination in Public Setting |

(8.0) “…Just like the airplane thing they want you to have to get two seats you know because they say you’re so big.” – 62 year old non-Hispanic black female (8.1) “I felt like there were times that they would not offer me seating because they didn’t think I would physically fit their booths or tables. They didn’t think that I would fit.” – 52 year old non-Hispanic black male (8.2) “I could probably shop there now, but the first time I walked in there the lady said I hadn’t even walked in the door yet and the lady said we have nothing for you here.” - 50 year old non-Hispanic black female |

| 8b. Discrimination within the Community |

(8.3) “I feel like there is a big stigma for people that are overweight or obese. I just feel like that people who don’t struggle with weight issues who look quote-on-quote normal that they don’t get it. It seems as though they treat overweight people like crap.” – 48 year old non-Hispanic black male (8.4) “People I think they look at big people as slops and lazy and everything and we’re not lazy.” – 50 year old non-Hispanic black female |

Note: The numbers in parentheses are for text references. Italicized text next to each number are direct quotes from participants.

MBS – metabolic and bariatric surgery

HBP – high blood pressure

GERD – gastroesophageal reflux disease

Table 2.

Participant Quotes, Organized by Themes and Sub-Themes and the Socioecological Framework’s Community and Environmental Domains

| COMMUNITY/INSTITUTIONAL | |

|---|---|

| Theme 9. Physician Influence | |

| 9a. Primary Care |

(9.0) “If my primary care physician did not think I should have it then I would have had second thoughts, but my primary care physician said that she thought it was a good idea that I looked into it and she referred me to the bariatric clinic.” – 49 year old non-Hispanic black female (9.1) “My primary doctor was very supportive.” – 66 year old non-Hispanic white female (9.2) “Well I really trust my primary. I’ve been seeing her for many years. Any other doctor wouldn’t have made that big of a difference, but she did.” – 55 year old non-Hispanic white female (9.3) “I had two doctors recommend it, big time. Actually three, heart doctor, family doctor and diabetes doctor.” – 54 year old non-Hispanic white male |

| SOCIETAL/ENVIRONMENTAL/PUBLIC POLICY | |

| Theme 10. Community-Based Support Programs | |

| 10a. Support Groups |

(10.0) “Why don’t you find more people to sit and talk or have group discussions about how we’re doing and what’s going on with us socially, mentally. What am I going through because I did go through some different emotional changes trying to stick through the programs as far as eating habits and thinking about hey I can’t do that anymore and I can’t eat that much anymore.” – 54 year old non-Hispanic black female (10.1) “Maybe just support groups in the area.” – 63 year old non-Hispanic white female (10.2) “When I was going through my little depression stage and stuff, but there was nothing available to call to get support. There were not a lot of people in my community that I could even reach out to.” – 63 year old non-Hispanic white male (10.3) “Maybe I don’t know what my resources are, but you know how on television or you see where Oprah would go to…we used to call a Fat Farm…go away for a week it would be super expensive…meals and exercise were all included and you might even have a therapy session. I would like to see that become more you know accessible…” – 63 year old non-Hispanic black female |

| 10b. Education |

(10.4) “People need more education.” – 60 year old non-Hispanic black female (10.5) “I guess that’s what I would like to see in my community is more people be understanding. Just because you’re overweight doesn’t mean you brought this upon yourself…” – 45 year old non-Hispanic white male |

| 10c. Access to Healthy Food |

(10.6) “You know I often buy a lot of stuff on Amazon. It’s my favorite shopping store…and some of that stuff is reasonably priced, but all of it is not cheap at all, but I don’t have any place for local health food store of any sort.” – 55 year old non-Hispanic white female (10.7) “Other choices of food would be good. I mean there are a couple of stores nearby. There is a Tom Thumb and that’s pretty much it in terms of better choices of food or places to buy from. More foods offered would be nice, but there are very few…” – 52 year old non-Hispanic black male (10.8) “I’m in a town that has 3 or 4 sit down restaurants that are not fast food. That’s it. There is not a lot of options here. The rest are fast food…we have three grocery stores in the city and I sometimes have to go to different ones to buy what I’m looking for on sale because it’s expensive to buy healthy food.” – 55 year old non-Hispanic white female (10.9) “…recently I was at Sam’s I guess yesterday or two days ago and they had 90% or a 93% lean ground beef, but it was expensive. So it is offered, but to even get to Sam’s is like 20 miles away. So maybe if I could have that at the local Wal-Mart which a lot closer only three or four miles away. If they offered the same 93% lean meat that would be nice, but they don’t.” – 52 year old non-Hispanic black male (10.10) “I would say work on our choices in our break areas. The healthy ones are expensive, but I think that I don’t know if I can blame anybody for that, that’s kind of the nature of things that are more natural tend to spoil sooner so they are more expensive to stock, but I wish there were more healthy food choices than in our break area.” – 54 year old non-Hispanic white female |

| 10d. MBS-Friendly Portion Sizes |

(10.11) “Like they have a menu where you have appetizers and then the menu with small bites hey have their regular menu. Well sometimes the appetizers and small bites are still too much. So it would be great if they had a little another subsection for us.“ – 63 year old non-Hispanic black female (10.12) “A lot of places don’t support people like us because you know they won’t let me buy a child’s plate because they have it defined by age.” – 61 year old non-Hispanic black female (10.13) “Not everybody wants an oversized serving of food.” – 61 year old African American female (10.14) “I just wish more of them would just do it. Give us the smaller portions. Even if its $2 more than the kid’s meal or whatever. I wish they would do it.” – 62 year old non-Hispanic white female |

| 10e. Access to Exercise Facilities |

(10.13) “My community doesn’t have side walks. They have a park, a nice park which is about a couple of miles from my house and I feel like I’m playing chicken with traffic when I walk to the park. So walking trails or sidewalks, a bike trail, things of that nature….” – 49 year old non-Hispanic black female (10.14) “It’s pretty industrial and there’s not a lot of area around here, but I would like to walk. So right after surgery I was walking five miles a day because my schedule change and I’m a little bit more restricted on my time period of being able to get out and go walking. A lot of my walking ends up being in just the parking lot.” – 66 year old non-Hispanic white female (10.15) “I live in the country so I’m in a small town so it would, you know, if there was more places to work out or even if someone would start a workout group.” – 48 year old non-Hispanic white male (10.16) “…I like to run, but I can’t run in my neighborhood because a lot of my neighbors they don’t have a dog fence so that dog can get out the yard…they will chase you if you’re running. Every few blocks or so I would encounter a dog that will run after you.” – 49 year old non-Hispanic black female |

Note: The numbers in parentheses are for text references. Italicized text next to each number are direct quotes from participants.

MBS – metabolic and bariatric surgery

INTRAPERSONAL

Theme 1. Motivation

Subtheme 1a. Comorbidity resolution

The majority of participants stated comorbidity resolution was a personal motivator to complete MBS. For example, one participant suffered from numerous obesity related comorbidities and knowledge that MBS was potentially effective in treating these health conditions was the deciding factor for her to complete MBS (Table 1, 1.0). Several participants stated they were grateful to have lost weight post-MBS, but they were more excited about their comorbidity resolution including lower blood pressure, cholesterol, less required diabetes medication, and in some cases ceasing medication use completely (1.1, 1.2 & 1.3).

Subtheme 1b. Mobility

Mobility was a major reason stated by almost all participants as to why they completed MBS. Participants wanted to be able to partake in normal daily activities such as walking, climbing steps and other exercises without feeling excessively tired and without feeling joint pains as a result of carrying excess weight (1.4, 1.5 & 1.6).

Theme 2. Adapting to dietary changes

Subtheme 2a. Relationship with food

Many participants were hesitant about their decision to have MBS because of their relationship with food. One participants considered herself a “foodie” and was fearful of how MBS would change her eating experience post-MBS (2.0). Others were unsure of how they would be able to make the adjustment from their past eating habits and adapt to a post-MBS diet that they perceived as a restrictive diet compared to their past dietary eating behavior (2.1). Post-MBS, some participants stated that they continue to struggle with adaptation to new dietary guidelines. Several participants used certain food as a reward for emotional satisfaction before surgery (2.2).

Theme 3. Self-esteem

Subtheme 3a. Post-MBS Improvement

After completing MBS, many participants and their social support network members commented on an improvement in self-esteem. Several patients stated they were learning to “love themselves more” and were more confident post-MBS (3.0, 3.1. & 3.2).

Theme 4. Social Interaction

Subtheme 4a. Social Changes

Participants stated that losing excess weight post-MBS changed how they perceived themselves as well as how others perceived themselves in social settings. Participants noticed they dressed better and looked better when they went out on social occasions (4.0). They stated they were recognized more in social settings, were less insecure and were motivated to socialize more often (4.0, 4.1, & 4.2).

Theme 5. MBS-Related Concerns

Subtheme 5a. Health Effects

Participants expressed that before surgery they often had general fears about the possibility of MBS-related complications. Most concerns were about the general safety of the procedure, pain they would potentially have to endure during the recovery process, and the fear of suffering from complications previously experienced by friends, family or co-workers who had MBS. All participants knew someone who had completed MBS and those who were reluctant to have the surgery knew a relative or friend that had a negative experience post-MBS. The common negative experiences were weight regain and infections post-surgery that resulted in other health complications. However, these participants ultimately overcame these fears and thought the benefit of surgery outweighed their concerns. This was accomplished through extensive discussions with their primary care physician (PCP), and key family and social support members. Additionally, their motivation to overcome obesity and its related health conditions was instrumental in their decision to complete MBS. Few participants also mentioned that attending a bariatric informational seminar helped to ease their minds about completing MBS (5.0, 5.1. 5.2, & 5.3).

INTERPERSONAL

Theme 6. MBS Referral Network

Subtheme 6a. Family/Friends

Before deciding to have MBS, most participants learned about the procedure through family, friends, co-workers and other individuals in their social network who had completed MBS. Hearing about their health and weight loss success post-MBS often was influential in the decision to have MBS (6.0 & 6.1).

Theme 7. Social Support System

Subtheme 7a. Pre/Post MBS

A good support system was the decisive factor for participants who were fortunate enough to have family members and friends to support them with their decision to have MBS, as well as their successful weight loss journey post-MBS. It was often mentioned that social support network members were key throughout the process by providing consistent encouragement, post-MBS assistance and emotional support. Additionally, social support members reassured patients during the MBS decision making process that they were making the right decision to have the surgery for their health and well-being (7.0, 7.1 &7.2)

Theme 8. Discrimination

Subtheme 8a. Discrimination from Strangers

The majority of participants stated that they had experienced discrimination in a public settings pre-MBS, and thus a key factor in their decision to complete MBS. Participants often mentioned discrimination in public seating in particular. For example, participants were required to purchase two airplane seats due to excess weight when traveling. Many others shared experiences of not been offered seating at restaurants because servers thought that participants were unable to fit the seats or booths in the restaurants due to excess weight (8.0 & 8.1). Others mentioned discrimination in retail clothing stores where employees have blatantly said “we have nothing for you here” (8.2).

Subtheme 8b. Discrimination within the Community

Most participants believe that individuals with excess weight are stigmatized and mistreated in their local communities on an everyday basis, whether it be in the grocery store, other retail establishments, movie theaters, and so on (8.3). One participant stated that most people consider bigger individuals to be “lazy and disheveled” (8.4).

GROUP/COMMUNITY/INSTITUTIONAL

Theme 9. Physician Influence

Subtheme 9a. Primary Care

Many participants stated that the medical opinion and the support of the participants’ physician, specifically their PCP played a major role in their decision to have MBS (9.0, 9.1, 9.2). One non-Hispanic black female participant mentioned that if the surgery was not recommended to her by her PCP she would be hesitant to follow through (9.0). Additionally, participants often trusted the opinion of their PCPs because they were more informed about the participant’s medical history so they felt their opinion was more important than others (9.2). One participant decided to have MBS because three of her doctors; a cardiologist, family medicine and endocrinologist recommended MBS (9.3).

MACRO-LEVEL/SOCIETAL/ENVIRONMENT/PUBLIC POLICY

Theme 10. Community-Based Support Programs

Subtheme 10a. Support Groups

In terms of support for long-term success post-MBS, participants often suggested holding consistent support groups and meetings in their neighborhood/community. They felt these sessions would be important to share each other’s recommendations and also discuss some of the challenges and changes faced post-MBS (10.0 & 10.1). One participant shared his experience with depression post-MBS, and he could not find a support group in his community to help him through such a difficult stage. (10.2) A lack of supportive programs for post-MBS patients especially support groups could hinder long-term post-MBS weight loss success. Additionally, some participants would like to have an all-inclusive program in their community that offers a variety of resources including post-MBS mental, physical and dietary support(10.3).

Subtheme 10b. Education

Study participants often stated the need for more “MBS awareness” in their communities. Participants felt this would assist with a better understanding and consideration of people who are overweight and also those who decide to complete MBS, which would ultimately lead to a reduction in discrimination and stigma associated with obesity (10.4 & 10.5).

Subtheme 10c. Access to Healthy Food

Several participants stated that healthy food options were limited in their communities (10.6,10.7). Many experienced difficulties finding healthy food options and had few or no access to local grocery and health food stores (10.6, 10.7). One participant would often purchase healthy food from online market places which are not always convenient, and healthy food items are more expensive than those found in-store (10.6). Others were surrounded by fast-food restaurants and at times had to travel for miles going from one grocery story to another in order to find affordable food (10.8, 10.9). Another participant mentioned the need for companies to create an environment in the workplace that promotes healthy eating by providing healthy snack options in vending machines or snack bars in breakrooms (10.10).

Subtheme 10d. MBS-Friendly Portion Sizes

In addition, participants would like to see more restaurants offer MBS friendly portion sizes (10.11) Post-MBS patients find it difficult to eat out because they are unable to eat large service sizes and would like to see more restaurants offer smaller portion sizes that are not reserved only for kids meals (10.12, 10.13, 10.14).

Subtheme 10e. Access to Exercise Facilities

Some participants expressed the need for more exercise facilities, sidewalks, walking trails and biking trails in their neighborhood and communities to support and sustain post-MBS physical activity levels (10.13). A few participants who live in industrial and rural areas find it difficult to exercise due to a lack of infrastructure. There are no sidewalks, fitness centers and fitness groups for them to join (10.14 &10.15). Additionally, participants raised concerns about community safety which often prevents them from exercising outside. They would prefer to go to an indoor exercise facility. For example, one participant shared that she no longer runs outside because several homes in her community that have dogs do not have fences so she is often chased by her neighborhood dogs (10.16).

Discussion

In this study, post-MBS patients and their family members were interviewed to determine what factors influenced their decision to undergo surgery. Study results found that the key facilitators to MBS completion were: the presence of social support systems, support from PCPs, the possibility of improvements in obesity related health conditions post-surgery, and increased mobility in particular.

Facilitators to MBS utilization

Our findings indicate that participants who had family and friends who provided encouragement and reinforced MBS-related health and weight loss benefits found it easier to commit to their decision to undergo surgery. Similarly, a recent study by Ficaro(38) that examined the psychosocial concerns of women who have undergone MBS highlighted the importance of pre and post-surgery social support systems to MBS success (38). This study reported that family support, such as attending MBS support groups provided MBS patients with the confidence, moral support and practical steps that resulted in a successful pre-to post-operative transition and recovery, as well as improved weight loss outcomes (38). As such, MBS clinics and healthcare facilities should be encouraged to offer post-op support groups for their patients to provide continued moral support, peer-to-peer experience sharing, and positive peer influence that may facilitate both short-and long-term desirable weight loss and other comorbidity outcomes. Additionally, this may increase MBS completion rates, and prevent weight regain after the 18-to-24 month plateau that many patients experience.

Our study found that patients, and those from racial minority backgrounds in particular, were more secure in their decision to undergo MBS with the full support of their PCP. Interestingly, others have reported that obesity is widely viewed by PCPs as a behavioral problem only (39). Consequently, PCPs view lifestyle changes as the most effective method for patients with obesity to lose weight (40). In a survey of PCPs, Perlman et al.(41) found that PCPs had fears of complication and death and therefore did not refer their patients to a bariatric surgeon (41, 42). Indeed, the value and perception of obesity care among primary healthcare providers is a barrier that may affect the rates of MBS completion.

The overall desire for improved physical and mental health was a significant motivational factors for study participants to undergo MBS. Many looked forward to discontinuing their medication for obesity related health conditions. Indeed, the study subject’s desires for improved health are corroborated in a study conducted by Boochieri et al. (43) that reported that patients often experienced full remission or improvements in obesity related health conditions post-MBS(44). Several study participants identified relief from joint pain, and an increase in physical activity, or decrease in sedentary behavior as key motivators to undergo MBS. A number of studies have reported that patients who achieved major weight loss experienced a significant improvement in mobility and energy levels (43, 44). These patients were able to partake in more activities of daily living versus pre-MBS, which many described as “emancipating” (44).

Challenges to MBS Utilization

In prior studies, insurance type and coverage status were reported as barriers to MBS utilization(45). Contrary to these findings, our study did not find that insurance coverage or MBS insurance approval process posed any challenges to the decision to undergo MBS. Participants in our study instead highlighted the need for community-based resources to overcome mental, physical and dietary challenges associated with long-term weight loss post-MBS. Specifically, access to healthy foods, exercise facilities and support groups were key resources identified by study participants to facilitate post-MBS weight loss and comorbidity resolution success. Unfortunately, the majority of participants reported a lack of access to healthy food stores and restaurants which complicated their decision to complete MBS, especially for racial minorities. Currently, many of these participants live in food desert and swamp communities and as such drive several miles to a major grocery store. Some reported using online market places to purchase healthy food items, which may not be a feasible, or cost-effective solution in the long-term. Additionally, study participants often described a lack of community exercise facilities that posed a major challenge to consistent physical activity to facilitate long-term weight loss.

Based on this study’s reported findings, possible additional strategies to facilitate MBS completion could include (1) collaborative goal-setting reinforced by the patient’s social support network; (2) community resources and policies that support long term healthy lifestyle change such as facilities/reimbursements for regular physical activity and quality food purchases if offered at local stores/markets; and (3) continued acceptance of MBS by PCP providers as a safe and effective strategy for weight loss and comorbidity resolution. Indeed, MBS patients can be advocates for public health change in their communities by requesting the provision of resources to support their post-operative lifestyle; consumer demand is often what drives change.

Study Limitations and Strengths

There are some limitations to the study that should be mentioned. Study recruitment was limited to one large geographic region, therefore findings may not be generalizable to other MBS patient samples. Additionally, MBS participants in this study were predominantly female, also limiting generalizability. Moreover, the sample size of the social support members included in the study was fairly small and majority were of African American decent, therefore findings may not be generalizable across all racial groups. Also, we did not collect data on patient education, employment, health insurance, disability and co-morbidities; all factors which may influence the decision to undergo MBS. Therefore, our findings may not be generalizable to other MBS patient populations.

However, the study does provide unique insights among patients who have successfully undergone MBS, their reasons for following through with the surgery, and resources they believe will support their weight loss and co-morbidity resolution success. Additionally, this study was supported by the socioecological model to generate the grand tour questions and provide the framework for results and interpretation.

Conclusion

This study utilized the socioecological framework to determine intrapersonal, interpersonal, social and environmental facilitators and barriers to MBS utilization. Study themes and sub-themes did not vary by race. Key intra/interpersonal facilitators to patients successfully undergoing MBS included social support systems, primary care physician (PCP) support of MBS, comorbidity resolution, discrimination experiences, and mobility improvements. Key community/environment themes associated with post-MBS sustained weight loss included community support groups and access to healthy foods and exercise facilities. Conversely, lack of community resources to support post-MBS lifestyle changes were identified as barriers. Results reported here can inform PCPs and social support networks about the benefits of MBS to improve MBS utilization rates. Communities should consider incorporating permanent accessible and affordable built environment resources to sustain increased physical activity and healthy food markets for their members who have undergone MBS.

Highlights.

Ten themes and 15 sub-themes were identified.

Key intra/interpersonal facilitators to MBS completion included social support systems, primary care physician (PCP) referrals, comorbidity resolution, discrimination experiences, and mobility improvements.

Key community/environment themes to post-MBS sustained weight loss included community support groups and access to healthy foods and exercise facilities.

No themes/sub-themes varied by ethnicity.

Acknowledgments

This study was funded by the National Institutes of Health, National Institute on Minority Health and Health Disparities (grant #R01MD011686)

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

Disclosures

No conflicts of interest to report for all authors.

References

- 1.Flegal KM, Kruszon-Moran D, Carroll MD, Fryar CD, Ogden CL. Trends in Obesity Among Adults in the United States, 2005 to 2014. JAMA. 2016. June 7;315(21):2284–91. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Wang CY, Gortmaker SL, Taveras EM. Trends and racial/ethnic disparities in severe obesity among US children and adolescents, 1976-2006. Int J Pediatr Obes. 2011. February;6(1):12–20. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Karter AJ, Ferrara A, Liu JY, Moffet HH, Ackerson LM, Selby JV. Ethnic disparities in diabetic complications in an insured population. JAMA. 2002;287(19):2519–27. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.McWilliams JM, Meara E, Zaslavsky AM, Ayanian JZ. Differences in control of cardiovascular disease and diabetes by race, ethnicity, and education: US trends from 1999 to 2006 and effects of Medicare coverage. Annals of Internal Medicine. 2009;150(8):505–15. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Zhang Q, Wang Y, Huang ES. Changes in racial/ethnic disparities in the prevalence of type 2 diabetes by obesity level among US adults. Ethnicity & Health 2009;14(5):439–57. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Golden SH, Brown A, Cauley JA, Chin MH, Gary-Webb TL, Kim C, Sosa JA, Sumner AE, Anton B. Health disparities in endocrine disorders: biological, clinical, and nonclinical factors--an Endocrine Society scientific statement. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2012. September;97(9):E1579–639. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Pratt LA, Brody DJ. Depression and obesity in the U.S. adult household population, 2005-2010.NCHS Data Brief. 2014. October;(167):1–8. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Sandoval JS, Harris JK, Jennings JP, Hinyard L, Banks G. Behavioral risk factors and Latino body mass index: a cross-sectional study in Missouri. J Health Care Poor Underserved. 2012. November;23(4):1750–67. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Johnson NB, Hayes LD, Brown K, Hoo EC, Ethier KA. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC). CDC National Health Report: leading causes of morbidity and mortality and associated behavioral risk and protective factors--United States, 2005-2013. MMWR Surveill Summ. 2014. October 31;63 Suppl 4:3–27. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Buchwald H, Avidor Y, Braunwald E, Jensen MD, Pories W, Fahrbach K, Schoelles K. Bariatric surgery: a systematic review and meta-analysis. JAMA 2004;292:1724–37. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Schauer PR, Kashyap SR, Wolski K et al. Bariatric surgery versus intensive medical therapy in obese patients with diabetes. N Engl J Med 2012;366:1567–76. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Sjöström L, Narbro K, Sjöström CD, et al. Effects of bariatric surgery on mortality in Swedish obese subjects. N Engl J Med 2007;357:741–52. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Sugerman HJ, Starkey JV, Birkenhauer R. A randomized prospective trial of gastric bypass versus vertical banded gastroplasty for morbid obesity and their effects on sweets versus non-sweets eaters. Ann Surg 1987;205:613–24. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Schauer PR, Ikramuddin S, Gourash W, Ramanathan R, Luketich J. Outcomes after laparoscopic Roux-en-Y gastric bypass for morbid obesity. Ann Surg 2000;232:515–29. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Maggard MA, Shugarman LR, Suttorp M et al. Meta-analysis: Surgical treatment of obesity. Ann Intern Med 2005;142:547–59. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Sjöström L, Lindroos AK, Peltonen M et al. Lifestyle, diabetes, and cardiovascular risk factors 10 years after bariatric surgery. N Engl J Med 2004;351:2683–93. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Dixon JB, O’Brien PE, Playfair J, et al. Adjustable gastric banding and conventional therapy for type 2 diabetes: a randomized controlled trial. JAMA 2008;299:316–23. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Mingrone G, Panunzi S, De Gaetano A, et al. Bariatric surgery versus conventional medical therapy for type 2 diabetes. N Engl J Med 2012;366:1577–85. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Schauer PR, Kashyap SR, Wolski K, et al. Bariatric surgery versus intensive medical therapy in obese patients with diabetes. N Engl J Med 2012;366:1567–76. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.De La Cruz-Munoz N, Messiah SE, Lopez-Mitnik G, Arheart KL, Lipshultz SE, Livingstone A. Laparoscopic Gastric Bypass Surgery and Adjustable Gastric Banding Significantly Decrease the Prevalence of Type 2 Diabetes Mellitus and Pre-Diabetes among Morbidly Obese Multiethnic Adults: Long-Term Outcome Results. J Amer Coll Surg 2011, April;212(4):505–11. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Buchwald H, Estok R, Fahrbach K, et al. Weight and Type 2 Diabetes after Bariatric Surgery: Systematic Review and Meta-analysis. Am J Med 2009;122:248–56. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Shukla AP, Moreira M, Dakin G, et al. Medical versus surgical treatment of type 2 diabetes: the search for level 1 evidence. Surg Obes Relat Dis 2012;8:476–82. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Sjöström L Review of the key results from the Swedish Obese Subjects (SOS) trial—a prospective controlled intervention study of bariatric surgery. J Intern Med 2013;273:219–34. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Buchwald H, Varco RL, Matts JP, et al. Effect of partial ileal bypass surgery on morta ity and morbidity from coronary heart disease in patients with Hypercholesterolemia: Report of the program on the surgical control of the Hyperlipidemias (POSCH). N Engl J Med 1990;323:946–55. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Christou NV, Sampalis JS, Liberman M, et al. Surgery decreases long-term mortality, morbidity, and health care use in morbidly obese patients. Ann Surg 2004;240:416–24. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Adams TD, Gress RE, Smith SC, et al. Long-term mortality after gastric bypass surgery. N Engl J Med 2007;357:753–61. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Luyckx FH, Desaive C, Thiry A, Thiry A, Lefébvre PJ. Liver abnormalities in severely obese subjects: Effect of drastic weight loss after gastroplasty. Int J Obes 1998;22:222–6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Rubino F, Nathan DM, Eckel RH, et al. Metabolic Surgery in the Treatment Algorithm for Type 2 Diabetes: a Joint Statement by International Diabetes Organizations. Obes Surg. 2017. January;27(1):2–21 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Flum DR, Dellinger EP. Impact of gastric bypass operation on survival: A population-based analysis. J Am Coll Surg 2004;199: 543–51. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Karlsson J, Sjöström L, Sullivan M. Swedish obese subjects (SOS) -An intervention study of obesity. Two-year follow-up of health related quality of life (HRQL) and eating behavior after gastric surgery for severe obesity. Int J Obes 1998;22:113–26. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Nguyen NT, Goldman C, Rosenquist CJ, et al. Laparoscopic versus open gastric bypass: a randomized study of outcomes, quality of life, and costs. Ann Surg 2001;234:279–91. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Buchwald H, Oien DM. Metabolic/bariatric surgery worldwide 2008. Obes Surg 2009;19:1605–11. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Pitzul KB, Jackson T, Crawford S, et al. Understanding disposition after referral for bariatric surgery: when and why patients referred do not undergo surgery. Obes Surg. 2014. January;24(1):134–40. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Sadhasivam S, Larson CJ, Lambert PJ, Mathiason MA, Kothari SN. Refusals, denials, and patient choice: reasons prospective patients do not undergo bariatric surgery. Surg Obes Relat Dis. 2007. Sep-Oct;3(5):531–5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Merrell J, Ashton K, Windover A, Heinberg L. Psychological risk may influence drop-out prior to bariatric surgery. Surg Obes Relat Dis. 2012. Jul-Aug;8(4):463–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Tsuda S, Barrios L, Schneider B, Jones DB. Factors affecting rejection of bariatric patients from an academic weight loss program. Surg Obes Relat Dis. 2009. Mar-Apr;5(2):199–202. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Guest G, Bruce A, Johnson L. How many interviews are enough? An experiment with data saturation and variability. Fields methods 2006; 18(1): 59–82 [Google Scholar]

- 38.Ficaro I “Surgical weight loss as a life-changing transition: The impact of interpersonal relationships on post bariatric women.” Applied Nursing Research 2018; 40: 7–12. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Foster GD, Wadden TA, Makris AP, et al. “Primary care physicians’ attitudes about obesity and its treatment.” Obesity research 2013; 11(10): 1168–1177. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Imbus JR, Voils CL, Funk LM, “Bariatric surgery barriers: a review using Andersen’s Model of Health Services Use.” Surgery for Obesity and Related Diseases 2018; 14(3): 404–412. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Perlman SE, Reinhold RB, Nadzam GS. “How do family practitioners perceive surgery for the morbidly obese?” Surgery for Obesity and Related Diseases 2007; 3(4): 428–433. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Tork S, Meister KM, Uebele AL, et al. “Factors influencing primary care physicians’ referral for bariatric surgery.” JSLS: Journal of the Society of Laparoendoscopic Surgeons 2015; 19(3). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Bocchieri LE, Meana M, Fisher BL. “Perceived psychosocial outcomes of gastric bypass surgery: a qualitative study.” Obesity surgery 2002. 12(6): 781–788. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Natvik E, Gjengedal E, Råheim M. “Totally changed, yet still the same: patients’ lived experiences 5 years beyond bariatric surgery.” Qualitative health research 2013; 23(9): 1202–1214. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Martin M, Beekley A, Kjorstad R, Sebesta J. “Socioeconomic disparities in eligibility and access to bariatric surgery: a national population-based analysis.” Surgery for Obesity and Related Diseases. 2010; 6(1): 8–15. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]