Abstract

Extracellular vesicles (EVs) contain multiple factors that regulate cell and tissue function. However, understanding of their influence on gametes, including communication with the oocyte, remains limited. In the present study, we characterized the proteome of domestic cat (Felis catus) follicular fluid EVs (ffEV). To determine the influence of follicular fluid EVs on gamete cryosurvival and the ability to undergo in vitro maturation, cat oocytes were vitrified using the Cryotop method in the presence or absence of ffEV. Vitrified oocytes were thawed with or without ffEVs, assessed for survival, in vitro cultured for 26 hours and then evaluated for viability and meiotic status. Cat ffEVs had an average size of 129.3 ± 61.7 nm (mean ± SD) and characteristic doughnut shaped circular vesicles in transmission electron microscopy. Proteomic analyses of the ffEVs identified a total of 674 protein groups out of 1,974 proteins, which were classified as being involved in regulation of oxidative phosphorylation, extracellular matrix formation, oocyte meiosis, cholesterol metabolism, glycolysis/gluconeogenesis, and MAPK, PI3K-AKT, HIPPO and calcium signaling pathways. Furthermore, several chaperone proteins associated with the responses to osmotic and thermal stresses were also identified. There were no differences in the oocyte survival among fresh and vitrified oocyte; however, the addition of ffEVs to vitrification and/or thawing media enhanced the ability of frozen-thawed oocytes to resume meiosis. In summary, this study is the first to characterize protein content of cat ffEVs and their potential roles in sustaining meiotic competence of cryopreserved oocytes.

Subject terms: Proteomic analysis, Cell delivery

Introduction

Assisted reproductive technologies (ARTs), especially the cryopreservation of gametes, are useful tools for preserving the fertility of human patients undergoing chemotherapy treatment1. Beyond their importance in human applications, ARTs are also a critical tool for the genetic preservation and ex situ population management of endangered species2,3. Embryo and sperm cryopreservation technologies are well established and routinely used in human fertility clinics4. Unlike sperm and embryos, the oocyte has several unique features (e.g., large size and amount of intracellular lipid) that contribute to its extreme susceptibility to damage during cryopreservation5,6. Nevertheless, the development of minimum volume vitrification (MVV) methods, such as open pulled straw and Cryotop, which permit cooling rates exceeding −100,000 °C min−1, has significantly improved the survival and function of frozen-thawed gametes7,8. So far, live offspring have been produced from cryopreserved mature oocytes in several mammalian species, including humans9–12. Crucially, however, the cryopreservation of immature oocytes is still far from being efficient4,10,13. Data from mouse and human studies have shown that vitrification better protects oocytes from structural damage and sustains gametes’ developmental competence than slow freezing12,14. For the domestic cat, although both slow-freezing and vitrification have been used to preserve immature oocytes4,13,15,16, the rates of cryopreserved immature oocytes that complete nuclear maturation are much lower than for fresh gametes (0–38%)3,4,13,16,17. Different approaches have been used to improve the survival and developmental competence of mature and immature vitrified oocytes. These include varying cryoprotectants (CPA) concentrations and exposure times18–21, polarization of lipid droplets by centrifugation9,22, supplementing freezing media with macromolecules23, ice-blockers20, or cytoskeleton modifiers18, modifications of membrane constituents19,24, as well as automation of the addition and removal of cryoprotectants using microfluidics devices24,25.

Additionally, it has been shown that human oocytes vitrified in autologous follicular fluid (FF) developed embryos after conventional IVF, with subsequent embryo-transfer resulting in the birth of healthy babies10. Follicular fluid is a complex biological fluid that is in close proximity to the developing oocyte26,27. The major components of FF are nucleic acids, ions, metabolites, steroid hormones, proteins, reactive oxygen species, polysaccharides and antioxidant enzymes, all of which play important roles in regulating folliculogenesis26,28. Recently, extracellular vesicles (EVs), which are likely secreted primarily by the follicle’s granulosa and theca cell populations, have also been detected in FF28–33. Extracellular vesicles are membrane encapsulated particles containing regulatory molecules, including proteins, peptides, RNA species, lipids, DNA fragments and microRNAs34–36. For follicular fluid EVs (ffEVs), microRNA content has been well-characterized28,32,37–39. It has been indicated that microRNAs in ffEVs play an important role regulating expression of genes involved in stress response, cumulus expansion and metabolic functions31. Yet, little is known about protein content in ffEVs. A study in the mare has identified 73 proteins in ffEVs, with immunoglobulins being the most abundant32. To date, there have been numerous reports on the characteristics of EVs recovered from male and female reproductive tract fluids, including fluids from the prostate40, epididymis40,41, vagina42,43, endometrium44–46 and oviduct47–50, and their roles in physiologic and pathologic processes29,31,33,42,50–52. Yet, the role of ffEVs in protecting oocytes against cryoinjuries has not been explored.

Cat oocytes share many characteristics with human ova, including germinal vesicle chromatin configuration, preovulatory oocyte size, and time to meiotic maturation in vitro53,54. Here, we utilized the domestic cat as a large-mammalian model with application potential to both endangered felid assisted reproduction and human fertility preservation. In the present study, we characterized the protein content of cat ffEVs and assessed their influence on the survival and in vitro maturation potential of vitrified immature cat oocytes.

Results and discussion

Follicular fluid EVs characterization

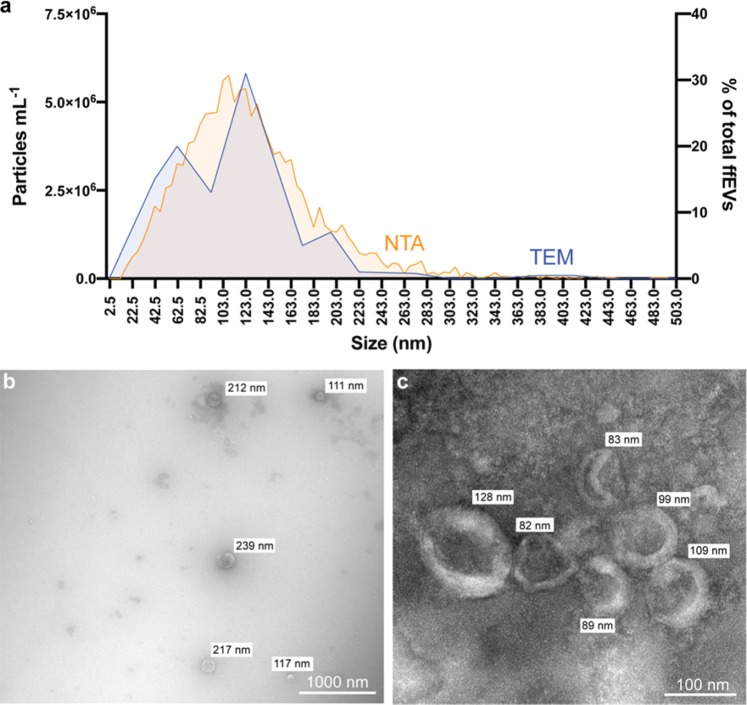

The Total Exosome Isolation Kit (Invitrogen, USA) was used to recover cat ffEVs, as previously utilized for cat oviductal EVs50. A combination of Nanoparticle Tracking Analysis (NTA) and Transmission Electron Microscopy (TEM) were used to confirm the presence of, characterize, and quantify cat ffEVs. Zeta View NTA showed the presence of EVs with an average size of 129.3 ± 61.7 nm (Fig. 1a). TEM confirmed the presence of circular vesicles with the characteristic doughnut shape with an average size of 93.2 ± 76.5 nm (12 to 507 nm, Fig. 1a–c). The average size of cat ffEVs observed in the present study is consistent with that reported in the cow (Bos taurus; 128–142 nm)29,33. The total ffEVs concentration detected by NTA ranged from 1.4 ×1010 to 14.0 ×1010 particles mL−1, with an average of 6.3 ± 5.8 ×1010 particles mL−1.

Figure 1.

Follicular fluid EVs characterization. In a size distribution of ffEVs quantified by nanoparticle tracking analysis (NTA, orange, left y axis), and analyzed by transmission electron microscopy (TEM, in percentage of total counted ffEVs, blue, right y axis). In b and c TEM image of ffEVs showing different size distribution of isolated ffEVs.

In the present study, we used ultraperformance liquid chromatography and tandem mass spectrometry (UPLC-MS/MS) to identify the protein content of follicular fluid EVs. A total of 674 protein groups out of 1,974 protein entries were identified and analyzed for gene ontology (Supplementary Data 1). Two functionally grouped gene ontology (GO) cellular component pathways related to EVs were identified: (1) extracellular vesicle (GO:1903561) and (2) extracellular exosome (GO:0070062); each pathway had 226 and 228 total proteins, respectively. The cat ffEVs contained several EVs markers, including, cytosolic proteins (CHMP4A, PDCD6IP, EHD2, RHOD, ANXA2, ANXA4, ANXA5, ANXA6, ANXA11, HSP90AB1, HSPA8, ACTBL2, ACTG1, ACTR1A, ACTR1B, ACTN2, ACTN1, ACTN4, ACTR3, ACTG1, ACTG2, ACTA1, ACTA2, ACTC1, ACTB, TUBB1, TUBB6, TUBAL3, TUBB4B, TUBB, TUBA8, TUBA4A, TUBB2A, TUBB2B, GAPDH, and GAPDH5), and transmembrane- or lipid-bound extracellular proteins (GNA12, GNA13, GNAT1–3, GNAO1, GNAL, GNAI1–3, ITGB1, ITGA6 and LAMP1), confirming the presence of EV origin in the recovered follicular fluid samples55.

Notably, it has been shown that the isolation of extracellular vesicles using precipitation methods, as the one used in the present study, can lead to a higher number of non-EV co-precipitates55. Following the Minimal Information for Studies of Extracellular Vesicles guidelines (MISEV 2018)55, we identified different kinds of apolipoproteins as potential co-precipitates in the ffEVs. However, apolipoproteins also play a significant role in fertilization and embryo development. It is therefore likely that reproductive fluid EVs naturally contain apolipoproteins, unlike other, non-reproductive EVs used in the MISEV guidelines. In this regard, apolipoproteins have been identified in proteomics of female fluids/EVs or produced by embryos in numerous species, including from EVs of the porcine endometrium46, sheep conceptus56, sheep uterine fluid of pregnant and non-pregnant sheep44, cat oviduct50, and from human follicular fluid57. In the present context, it is therefore difficult to ascertain if apolipoproteins are co-precipitates or are normally present in reproductive EVs.

Follicular fluid EVs protein content and their possible role on oocyte structure and function

To further characterize domestic cat ffEV proteins, a functional analysis of the 1,974 protein entries was evaluated using the Cytoscape ClueGO plugin58. The comparative analysis of GO terms identified a total of 429 GO biological processes, 136 GO molecular functions, and 151 GO cellular components by analyzing the corresponding genes to all identified proteins in the cat ffEVs in reference to the domestic cat (Felis catus) genome (Supplementary data 1). For GO biological processes, 54 terms important for the maintenance of COCs structure and function were identified (Table 1).

Table 1.

Selected gene ontology (GO) terms for biological processes of ffEVs, including significance (Group P-value) and the percentage of associated genes.

| GO ID | GO Term | Group P-value | % Associated Genes |

|---|---|---|---|

| GO:0051276 | chromosome organization | 0.00 | 8.29 |

| GO:0051293 | establishment of spindle localization | 0.00 | 20.00 |

| GO:0051653 | spindle localization | 0.00 | 17.14 |

| GO:0006997 | nucleus organization | 0.02 | 8.75 |

| GO:0007051 | spindle organization | 0.01 | 8.26 |

| GO:0000212 | meiotic spindle organization | 0.04 | 20.00 |

| GO:0051294 | establishment of spindle orientation | 0.05 | 12.00 |

| GO:0007010 | cytoskeleton organization | 0.00 | 6.69 |

| GO:0030036 | actin cytoskeleton organization | 0.00 | 7.42 |

| GO:0007015 | actin filament organization | 0.00 | 8.80 |

| GO:0030029 | actin filament-based process | 0.00 | 6.84 |

| GO:0031032 | actomyosin structure organization | 0.00 | 10.40 |

| GO:0061572 | actin filament bundle organization | 0.01 | 8.25 |

| GO:0051017 | actin filament bundle assembly | 0.01 | 8.25 |

| GO:0000226 | microtubule cytoskeleton organization | 0.04 | 5.31 |

| GO:0031032 | actomyosin structure organization | 0.00 | 10.40 |

| GO:0031122 | cytoplasmic microtubule organization | 0.04 | 9.76 |

| GO:0030865 | cortical cytoskeleton organization | 0.02 | 12.12 |

| GO:0030866 | cortical actin cytoskeleton organization | 0.02 | 10.34 |

| GO:0032964 | collagen biosynthetic process | 0.02 | 25.00 |

| GO:0032963 | collagen metabolic process | 0.02 | 13.51 |

| GO:0032965 | regulation of collagen biosynthetic process | 0.05 | 18.18 |

| GO:0010898 | positive regulation of triglyceride catabolic process | 0.02 | 40.00 |

| GO:0010873 | positive regulation of cholesterol esterification | 0.02 | 33.33 |

| GO:0010896 | regulation of triglyceride catabolic process | 0.02 | 28.57 |

| GO:0051006 | positive regulation of lipoprotein lipase activity | 0.02 | 28.57 |

| GO:0045723 | positive regulation of fatty acid biosynthetic process | 0.02 | 28.57 |

| GO:0034370 | triglyceride-rich lipoprotein particle remodeling | 0.02 | 25.00 |

| GO:0034380 | high-density lipoprotein particle assembly | 0.02 | 25.00 |

| GO:0034372 | very-low-density lipoprotein particle remodeling | 0.02 | 25.00 |

| GO:0010872 | regulation of cholesterol esterification | 0.02 | 25.00 |

| GO:0061365 | positive regulation of triglyceride lipase activity | 0.02 | 25.00 |

| GO:0033700 | phospholipid efflux | 0.02 | 20.00 |

| GO:0034433 | steroid esterification | 0.02 | 18.18 |

| GO:0051004 | regulation of lipoprotein lipase activity | 0.02 | 18.18 |

| GO:0034434 | sterol esterification | 0.02 | 18.18 |

| GO:0034435 | cholesterol esterification | 0.02 | 18.18 |

| GO:0043691 | reverse cholesterol transport | 0.02 | 18.18 |

| GO:0090208 | positive regulation of triglyceride metabolic process | 0.02 | 16.67 |

| GO:0044241 | lipid digestion | 0.02 | 14.29 |

| GO:0098609 | cell-cell adhesion | 0.00 | 6.30 |

| GO:0034109 | homotypic cell-cell adhesion | 0.00 | 21.43 |

| GO:0090136 | epithelial cell-cell adhesion | 0.01 | 25.00 |

| GO:0061077 | chaperone-mediated protein folding | 0.00 | 21.05 |

| GO:0016485 | protein processing | 0.00 | 10.06 |

| GO:0051604 | protein maturation | 0.00 | 9.55 |

| GO:0006956 | complement activation | 0.00 | 29.41 |

| GO:0072376 | protein activation cascade | 0.00 | 40.00 |

| GO:0015671 | oxygen transport | 0.00 | 44.44 |

| GO:0045454 | cell redox homeostasis | 0.00 | 14.04 |

| GO:1902883 | negative regulation of response to oxidative stress | 0.01 | 15.38 |

| GO:1900408 | negative regulation of cellular response to oxidative stress | 0.01 | 15.38 |

| GO:0080134 | regulation of response to stress | 0.00 | 5.42 |

| GO:0034976 | response to endoplasmic reticulum stress | 0.00 | 8.38 |

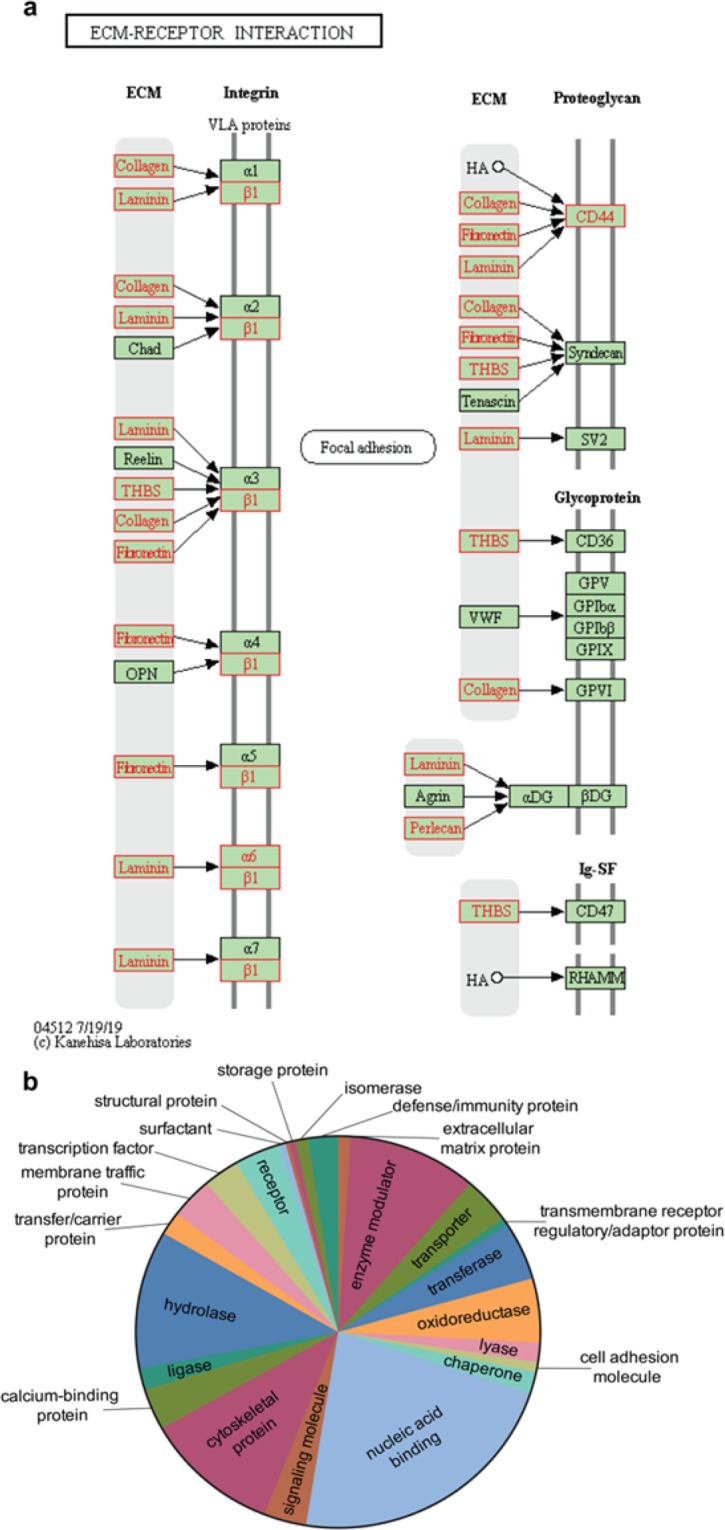

Next, we identified molecular networks in which ffEVs proteins are active via KEGG mapper59–62. Among the identified pathways, oxidative phosphorylation (Supp. Figure 1a), extracellular matrix (ECM, Fig. 2a), oocyte meiosis (Supp. Figure 1b), tight junction (Supp. Figure 2a), regulation of actin cytoskeleton (Supp. Figure 2b), cholesterol metabolism (Supp. Figure 3a), glycolysis/gluconeogenesis (Supp. Figure 3b), and MAPK, PI3K-AKT, HIPPO and calcium signaling pathways (Supp. Figure 4a–d) have been shown previously to play important roles in oocyte structure and function63–69.

Figure 2.

KEGG molecular pathways performed by KEGG mapper (http://www.genome.jp/ kegg/mapper)59 and GO protein class of ffEVs identified proteins. In a, KEGG pathways related to ECM-receptor interaction. Note that proteins present in ffEVs are shown in red. In b, pie chart of the 24 different GO protein classes corresponding to the proteins present in the cat ffEVs.

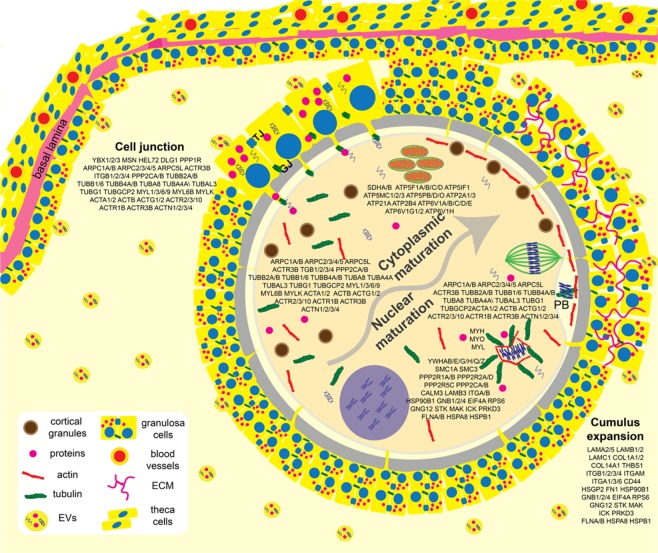

Through these analyses, twenty-four GO protein classes were identified to have roles in modulating response to cryopreservation, including oxidoreductases, cytoskeletal proteins, and chaperones (Fig. 2b). Chaperone proteins, such as the heat shock proteins (HSPs) are known to respond to a series of stresses, including sub- or supra physiological temperatures, toxic substances, extreme concentration of ions and other osmolytes70,71, conditions which are encountered by the oocyte during cryopreservation. Nine HSPs were abundantly detected in the cat ffEVs (HSPE1, HSPD1, HSP90AB1, HSPB1, HSP90AA1, HSPA8, LOC105260573, HSPA4L and HSPA2). Another class of chaperons, the chaperonins, that are necessary for folding actin, tubulin and newly synthesized proteins, playing a role on establishing functional cytoskeleton72, were also detected in the cat ffEVs (CCT8, CCT5, TCP1, CCT7, CCT2, CCT6B, CCT6A, CCT3 and CCT4). Additionally, many identified proteins from ffEVs are known to regulate oocyte maturation processes, including the Germinal Vesicle Breakdown (GVB), spindle migration and rotation, chromosome segregation, polar body extrusion, cumulus cells expansion, cell junctions, and cytoplasm maturation63,69,73–76 (Fig. 3). Taken together, we postulated that the transfer of these ffEV proteins to the oocytes prior to vitrification and/or during thawing could improve immature oocyte cryotolerance.

Figure 3.

Representative ovarian follicle with COC, summarizing oocyte cytoplasmic and nuclear maturation steps and participating proteins that could be delivered by ffEVs. PB = polar body, TJ = tight junction, GJ = gap junction, ECM = extracellular matrix.

Follicular fluid EVs are taken up by the immature COCs and deliver their membrane protein and lipid contents to the COCs

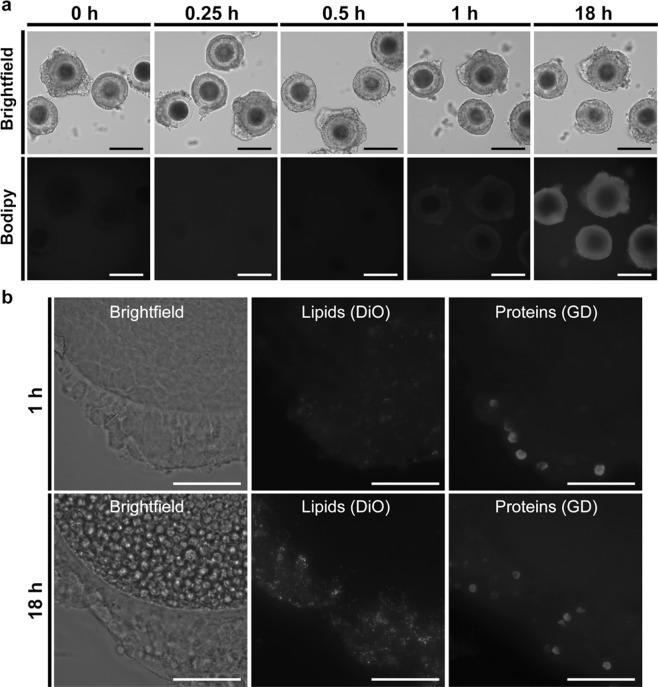

Extracellular vesicle entry and cargo release into cells has been proposed to occur via endocytosis, phagocytosis, micropinocytosis and/or through direct EV-plasma membrane fusion (reviewed in77). Lipid dyes, such as the fluorescent neutral lipid BODIPY TR ceramide and the carbocyanine dyes DiO and DiL, and amine groups binding dyes, such as the Ghost dye UV (GD), have already been used to investigate the binding and delivery of EVs lipids and proteins, respectively, to cells78–80. To determine whether cat ffEVs were taken up by COCs, COCs were incubated with BODIPY TR Ceramide labeled ffEVs (1.5 ×107 particles/ml) and imaged at 15 minutes, 30 minutes, 1 hour and 18 hours. Uptake of ffEVs by COCs was first detected after 30 minutes incubation and, at 1 hour, all analyzed COCs had the red fluorescence in their cumulus cells layer (Fig. 4a) which was not observed in the no ffEVs controls (Supplementary Fig. 5). Next, COCs were incubated with DiO and GD labeled ffEVs (1.5 ×107 particles/ml) and analyzed at 1 hour and 18 hours for lipid and membrane-bound protein uptake, respectively. Similar to the BODIPY staining, both lipids and membrane-bound proteins were detected in the cumulus cells at 1 hour and maximized at 18 hours (Fig. 4b). However, labeled lipids and membrane-bound proteins were not detected in the oocytes even after an 18 hour incubation period. This finding is consistent with a bovine study in which it was reported that ffEVs were taken up by cumulus cells but were not observable via confocal microscopy in the oocyte after 16 hours incubation33. In another study, oviductal EVs were observed to be taken up by domestic dog oocytes after 72 hours incubation81. In the cow study as in the present, it was not conclusively determined if the lack of observable labeled proteins/lipids in the oocyte and/or its plasma membrane was due to their absence, or if the amount delivered was below the threshold of detection by confocal and widefield fluorescence microscopy, respectively. Future studies using higher resolution microscopy, such as the stochastic optical reconstruction microscopy (STORM) could help answer this. Nevertheless, based on these results we selected the 1 h time for pre-incubation of COCs with ffEVs for the vitrification study.

Figure 4.

COCs uptake of ffEVs. In a, BODIPY labeled ffEVs uptake was evaluated before (0 hr), or following 0.25 h, 0.5 h, 1 h, or 18 h co-incubation with COCs. Fluorescence image in a showing uptake of ffEVs by the cumulus cells in a time dependent manner. In b, transfer of lipid (DiO) and membrane-bound protein (GD) labeled ffEVs to COCs after 1 or 18 h incubation. Bars = 100 and 25 µm for a and b panels, respectively.

Incubation with ffEVs improves oocyte meiosis resumption after vitrification

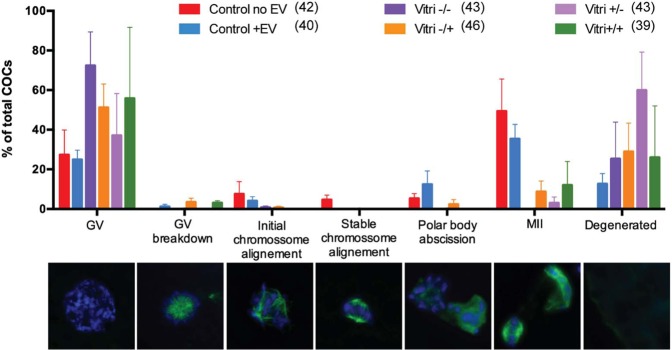

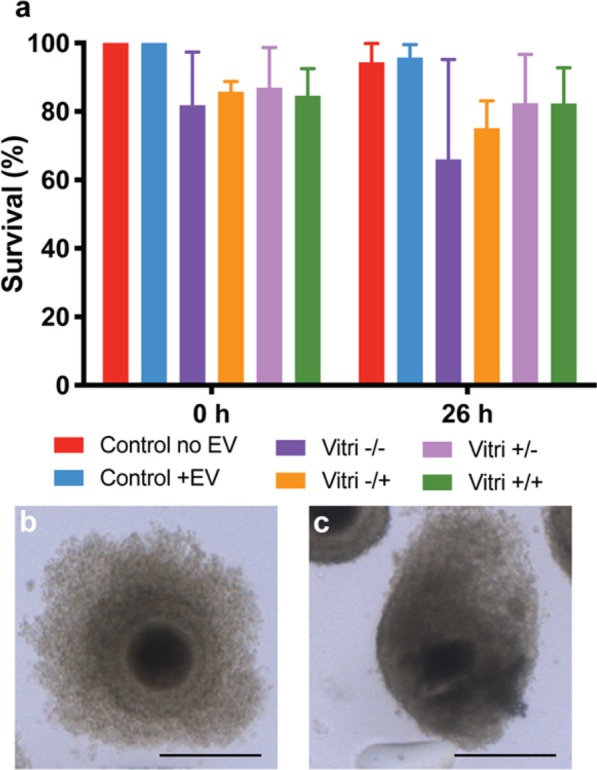

We next sought to evaluate the impact of ffEV supplementation to cat oocyte survival immediately and 26 h post-vitrification. There was no significant difference in oocyte viability among groups (Fig. 5). When comparing individual oocyte maturation stages, there also were no significant difference among treatment groups (Fig. 6).

Figure 5.

In a, survival rate of non-vitrified (Control) and vitrified oocytes in the presence or absence of ffEVs. Data is present as mean ± SD. In b a normal surviving oocyte and in c a non-surviving oocyte. Bars = 100 µm.

Figure 6.

Oocyte maturation stages of non-vitrified (Control) and vitrified COCs (Vitri), in the presence (+EV) or absence (-EV) of ffEVs, detected at 26 h. Bellow each stage in the graph are the corresponding representative images of the progression of oocyte meiotic stages with chromatin content (Hoechst 33342, blue) and tubulin (green). From left to right are germinal vesicle (GV), germinal vesicle breakdown (GV breakdown), initial chromosome alignment, stable chromosome alignment, polar body abscission, metaphase II (MII) and degeneration. No significant differences were noted between controls and vitrified oocytes (Friedman non-parametric analysis of variance, p > 0.05), regardless of the presence of ffEVs previously to or during thawing.

Vitrification compromised the ability of the oocytes to undergo meiotic resumption (GVB to MII) (21 ± 14.1 vs 74.5 ± 4.9%, ChiSquare, p < 0.0001, average ± SD of all vitrified treatments and the two fresh controls, respectively). However, the presence of ffEVs before and/or after vitrification improved meiotic resumption in vitrified COCs (28.3 ± 13.1 vs 8.6%, ChiSquare, p = 0.0033, Fig. 7). Furthermore, vitrified oocytes only reached metaphase II (MII) when ffEVs were present (17.9%), although these values were still much lower than the fresh control oocytes (42.5%). Reduced maturation due to vitrification damage was also described for vitrified immature COCs in several species, including the cat, bovine, ovine, horse and human3,11,20,82,83.

Figure 7.

Activation of meiotic resumption plot of vitrified oocytes in the absence (Vitri no EV) or presence of ffEVs (Vitri + EV) through the experimental time point. Note the higher initiation of oocyte maturation in the Vitri +EV group (ChiSquare, p = 0.0033). GVB, germinal vesicle breakdown; ICA, Innitial chromosome alignment; SCA, Stable chromosome alignment; PBA, Polar body abscission; MII, Metaphase II.

The improved meiotic resumption of vitrified oocytes co-incubated with ffEVs could be explained by the delivery of different proteins, RNAs, and lipids from the ffEVs to the COCs. Potential modulating proteins can be broadly grouped into four categories based on their function: cell-cell communications, meiosis resumption, structural stabilization, and metabolism. The bidirectional communication between the oocyte and the granulosa cells via gap junction permits follicular and oocyte development and is mediated by a network of cellular junctions76. In the present study, we demonstrated that proteins regulating the formation of tight junctions (such as PP2A, DLG3, ZONAB, ERM, SYNPO, different actin isoforms, Arp2/3, Integrin, myosin II and TUBA) are also present in the cat ffEVs. Because proteins from tight junctions can also regulate gap junction formation, it is possible that these proteins84,85 could play roles in maintaining the communication between the granulosa cells and, possibly, between granulosa cells and the oocytes, after cryopreservation.

Follicular fluid EV proteins with potential roles in modulating meiosis resumption include those involved in cumulus cell expansion, nuclear envelope breakdown, and spindle stabilization. Previous studies have shown that ffEVs are taken up by bovine COCs and enhance cumulus cell expansion33. This effect is possibly mediated by proteins involved in MAPK and PI3K pathways76, many of which were found in cat ffEVs. Cumulus cell expansion is also dependent on cumulus extracellular matrix formation and composition69. Here, we identified ECM components and receptors in the cat ffEVs (Fig. 2a), previously demonstrated to be required for COCs matrix formation in bovine granulosa cells76. It is also known that MAPK and PI3K pathways are important for the meiotic resumption in the oocyte86. In the present study, several proteins involved in the MAPK and PI3K signaling pathways, including SMC1A, SMC3, PP2Rs, CALM3, HSP90B1, HSPA8, HSPB1, EIF4A, MAK, and ICK, were present in cat ffEVs. Likewise, miRNAs regulating the same pathways have been found in bovine, equine and human ffEVs32,33,37,38,87,88. Therefore, these proteins and miRNAs could play important roles on oocyte meiotic resumption. For example, the Arp2/3 complex is essential for F-actin shell nucleation and consequent nuclear membrane fragmentation, leading to the nuclear envelope breakdown (NEB) in starfish65. Components of the Arp2/3 complex that play roles in actin cytoskeleton formation were abundant in the cat ffEVs and could also contribute to the higher meiosis resumption of vitrified COCs in the presence of ffEVs.

Improved mitochondrial function could also contribute to the higher meiotic resumption of ffEV supplemented vitrified oocytes. When porcine oocytes were incubated with the mitochondrial activity inhibitor Carbonyl cyanide p-trifluoromethoxyphenylhydrazone (FCCP), a significant reduction in the membrane potential and first polar body extrusion was observed89. Similarly, FCCP reduced the percentage of oocyte with nuclear maturation, normal spindle formation and chromosome alignment in mice90 demonstrating the importance of mitochondrial activity for normal oocyte maturation. The cat ffEVs had, at least, 26 proteins that are part of the oxidative phosphorylation and could modulate mitochondria function, improving vitrified oocyte maturation. It is likely that ffEVs also contributed to cell structural recovery and to stress response following vitrification. Vitrification was previously described to increase the number of abnormal spindle in MII oocytes from sow, cow, woman, mouse, horse and cat18,54,91–93. In our study, no abnormal MII spindles were observed in the non-vitrified controls or in the vitrified oocytes that were incubated with ffEVs. It may be that ffEVs delivered factors such as F-Actin, Arp2/3, PIR121, VCL, actin, myosin, ERM, PI4P5K, CFN, FN1, UTG, GSN, MLC, among others, that could positively affect the spindle stabilization of vitrified oocytes after vitrification. Likewise, an increased stress induced response through HSPs and chaperonins could also prevent spindle abnormalities. In the mouse, the oocyte has maximized heat shock response during the growth period, which declines when they acquire their full size and is shut off in later stages of follicular maturation, around the GVB, which could explain why mammalian oocytes are sensitive to thermic stress94,95. Reduced polar body extrusion and increased abnormal spindle assemblies have been observed when the modulation of the chaperonin TCP1 function was depleted in mouse oocytes (by siRNA silencing of its modulator Txndc9)72.

Conclusion

In summary, the present study is the first to characterize protein content of cat ffEVs. Our results showed that ffEVs are enriched in proteins that can play roles in regulating follicle growth, oocyte energy metabolism, oocyte maturation, stress response and cell-cell communication, suggesting that ffEVs may play important roles in the crosstalk that occurs between the somatic and germline follicular components. We also demonstrated, for the first time, that ffEVs improve meiotic resumption of vitrified COCs and can be used as a tool to improve gamete cryopreservation. The next steps are to identify mechanisms by which ffEVs regulate follicle and oocyte development. Furthermore, it is well established that the plasma membrane permeability modulates several types of cell injury associated with cryopreservation, including volume changes due to osmotic stress and CPA toxicity96,97. Therefore, investigations on the role of ffEVs lipids on COC function and cryopreservation are also required.

Materials and methods

Reagents

All reagents were purchased from Sigma Aldrich (St. Louis), unless otherwise stated.

Follicular fluid EV (ffEV) isolation and oocyte collection

Domestic cat ovaries voided of corpora hemorrhagica and/or lutea (4 months to 3 years old) were opportunistically collected from local veterinary clinics after routine ovariohysterectomy and transported at 4 °C to the laboratory within 6 hours of excision. No additional permissions were required since these biological materials were designated for disposal via incineration. After being washed three times in Phosphate Buffer Saline solution (PBS, GIBCO, USA), follicular fluid was aspirated from antral-stage follicles (1–8 mm diameter), centrifuged at 2,000 × g at room temperature for 30 minutes to remove cells and debris. The supernatant was then mixed with 500 μL of the Total Exosome Isolation Reagent (Invitrogen, USA) and incubated overnight at 4 °C. The samples were centrifuged at 10,000 × g for 1 hour, and the pellet resuspended in 50 μL of PBS. ffEVs were then aliquoted, and stored at −20 °C until use. Each ffEV aliquot was only thawed once immediately prior to utilization, to avoid multiple freeze/thaw cycles.

Oocytes were collected from spayed domestic cat ovaries (>10 months old). Ovaries were washed in handling medium composed of MEM eagle with 100 U ml−1 penicillin G, 10 mg ml−1 streptomycin sulfate, 100 mM pyruvate, 25 mM HEPES, and 4 mg ml−1 bovine serum albumin. Oocytes were collected via dicing of the ovarian cortex with a scalpel blade. Homogenously dark, circular oocytes with at least two layers of surrounding cumulus cells were selected for use.

Follicular fluid EV quantitation

Nanoparticle tracking analysis was done using the ZetaView S/N 17–332 (Particle Metrix, Meerbusch, Germany) and data analyzed using its software (ZetaView 8.04.02) by Alpha Nano Tech (Research Triangle Drive, NC, USA) as previously described98. For each replicate (n = 4, pooled frozen-thawed samples from 1–4 individuals, totaling 9 cats), ffEVs sample (1 ml) was diluted 100X in PBS, loaded into the cell, and the instrument measured each sample at 11 different positions throughout the cell, with three cycles of readings at each position. The pre-acquisition parameters were: sensitivity of 85, frame rate of 30 frames per second (fps), shutter speed and laser pulse duration of 100, temperature of 19.81 °C, and pH of 7.0. Post-acquisition parameters were set to a minimum brightness of 22, a maximum area of 1000 pixels, and a minimum area of 10 pixels98. All parameters (temperature, conductivity, electrical field, and drift measurements) were documented for quality control. After software analysis, the mean, median, and mode (indicated as diameter) sizes, as well as the concentration of the sample, were calculated, excluding outliers98. The number of particles per particle size curves was created using quadratic interpolation98.

Proteomic analyses

Follicular fluid EVs (n = 7 cats) were pooled, frozen at −20 °C. Proteins were extracted and prepared via single-pot, solid phase-enhanced sample-preparation (SP3) technology99 by Bioproximity LLC (Chantilly, VA), and analyzed using ultraperformance liquid chromatography and tandem mass spectrometry (UPLC - Thermo Easy-nLC 1200 fitted with a heated, 25 cm Easy-Spray column – MS/MS - Thermo Q-Exactive HF-X quadrupole-Orbitrap mass spectrometer). The peptide dataset (mzML format) were exported to Mascot generic format (mgf) and searched using X!!Tandem100 using both the native and k-score scoring algorithms101, and by OMSSA102. RAW data files were compared with the protein sequence libraries available for the domestic cat (Felis catus, taxa 9685). Label free quantification (MS1-based) was used and peptide peak areas were calculated using OpenMS103. Proteins were required to have one or more unique peptides across the analyzed samples with E-value scores of 0.01 or less.

Functional GO clustering

Data Entrez Gene IDs were mapped for all identified proteins using the R package rentrez (ver 1.2.1)104. The background dataset for all analyses was the cat (Felis catus) genome. Gene ontology (GO) analyses were performed using KEGG mapper59,60,62 (https://www.genome.jp/kegg/mapper.html) web-based software and the use of figures in the present manuscript were granted by Kanehisa Laboratories under reference 200029. For enrichment analysis, the cut off was set to p < 0.05. The Cytoscape 3.5.1 plugin ClueGO58 was used to visualize interactions of EVs proteins and networks integration, by GO terms “biological processes”, “molecular function” and “cellular components” using the Felis catus genome. The evidence was set to “Inferred by Curator (IC)”, and the statistical test was set to a right-sided hypergeometrical test with a κ score of 0.7–0.9 using Bonferroni (step down). The function “GO Term fusion” was selected, the GO term restriction levels were set to 3, and a minimum of two genes or 5% genes in each GO term was used.

Follicular Fluid EV transmission electron microscopy

TEM preparation and imaging was performed at the Alpha Nano Tech (Research Triangle Drive, NC, USA) on isolated EVs, stored at -20 °C until analysis. Briefly, Formvar coated carbon coated TEM grids (Electron Microscopy Sciences) were floated on 10 µL of sample drop for 10 minutes, washed two times with water by floating on the drop of water for 30 seconds, and negatively stained with uranyl acetate (2%) by floating on the drop of stain for 30 seconds. The grids were blot dried with Whatman paper and imaged on a Jeol JEM1230 transmission electron microscope (TEM).

Follicular Fluid EV Uptake Testing

Follicular fluid EVs (n = 3 cats) were stained by phospholipid bilayer BODIPY® TR Ceramide (Invitrogen, USA) or by a combination of DiO (Thermo-Fisher) and Ghost dye UV (GD, Tonbo Biosciences). Briefly, 5 µM BODIPY TR Ceramide stock solution in DMSO or 1 µg mL−1 of DiO + 1 µL mL−1 of GD, were incubated with 50 μl of total EVs for 30 minutes at room temperature (BODIPY) or at 37 °C (DiO + GD). Unbound dye was removed by Exosome Spin Columns (Invitrogen, USA), following manufacturer’s instructions. For negative controls, the dye samples without EVs were passed through the Exosome spin columns, and then used in uptake experiments.

Freshly collected domestic cat cumulus-oocyte complexes (COCs, n = 3 animals, 100 oocytes) were co-incubated in 50 µl droplets of handling medium, immersed in mineral oil, in the absence or presence of 1.5 ×107 particles ml−1 dyed ffEVs. Oocytes (5–7/droplet) were imaged at 10, 20, 40 and 100 × under a fluorescence microscope (EVOS FL auto 2, Invitrogen, USA) after 0, 15, 30, 60, and 1080 min (18 hr) co-incubation at 5% CO2 and 38 °C.

Oocyte Cryopreservation and Thawing

COCs were cryopreserved using a protocol modified from Comizzoli et al. (2009)105 and Colombo et al. (2019)16. Briefly, COCs were transferred in small groups (7–11 oocytes) via a mouth pipette to an equilibration solution, consisting of handling medium supplemented with 7.5% (v/v) ethylene glycol and 7.5% (v/v) dimethylsulfoxide for 3 minutes on ice. COCs were then briefly exposed to vitrification solution containing 15% ethylene glycol, 15% DMSO, and 0.5 M sucrose in handling medium for 30 seconds before being loaded in minimal volume on a Cryotop (Kitazato, Japan) and plunged into liquid nitrogen according to manufacturer’s instructions. COCs were thawed by passing them through a sucrose gradient (1.0, 0.5, 0.25, and 0 M) of warmed (38.5 °C) handling medium with or without 1.5 ×107 particles ml−1 ffEV.

In Vitro Maturation

In vitro maturation of cat oocytes was performed using a method previously described for the domestic cat106. Briefly, 50 µl droplets of Quinn’s Advantage Protein Plus Blastocyst Medium, supplemented with 1 µg ml−1 follicle stimulating hormone (Folltropin, Vetoquinol, USA), and luteinizing hormone (Lutropin V, Vetoquinol, USA), were equilibrated under mineral oil at 5% CO2 and 38 °C for at least 2 hours before use. Fresh or frozen-thawed cat COCs were transferred in groups of 14–28 oocytes to each droplet and incubated for 24 hours. Following IVM, oocytes were washed in PBS containing EDTA (0.1 mM), EGTA (0.1 mM), Imidazole (50 mM), 4% Triton-X, PVP (3 mg mL−1) and PMSF (24 µM). During this step, oocytes were rapidly pipetted up and down to remove cumulus cells, then fixed overnight in 4% paraformaldehyde in PBS at 4 °C.

Oocyte survival, defined as maintaining normal morphology with spherical shape, intact membranes, clear zone without rupture, and uniform cytoplasm, was evaluated immediately after thawing (0 h) and following in vitro maturation (26 h) via light microscopy107.

Oocyte Spindle Staining and Imaging

After fixation, oocytes were washed in washing buffer consisting PBS with 2.5% (v/v) normal goat serum and 0.5% triton X, then blocked for 30 min at 38 °C in PBS with 5% normal goat serum and 0.5% Triton X before incubation with rabbit anti-alpha tubulin (ab18251, Abcam) at 1:125 dilution in washing buffer for 1 hour at 38 °C. After washing, oocytes were incubated for 1 hour at 38 °C in goat-anti-rabbit IgG (1:200 dilution) and Hoechst 33342 (5 µg mL−1, Invitrogen) washed and placed into a small drop of ProLong Glass Anti-fade mounting solution (Invitrogen P36980) on a glass slide, and imaging under a fluorescent microscope (EVOS FL auto 2). Oocytes were imaged under 1,000 × magnification using a fluorescence microscope (EVOS FL auto 2, Invitrogen, USA) to observe microtubule organization, and staged as previously described with some modifications108.

Experimental Design

Study 1: Characterization of cat follicular fluid

Follicular fluid was collected and pooled from 1–4 individuals in domestic cat (n = 9). The amount of EVs in pooled follicular fluid was then quantified by Nano tracking analysis and its presence confirmed by transmission electron microscopy. Pooled ffEV samples from 7 of same 9 cats were subjected to proteomics analysis and uptake testing.

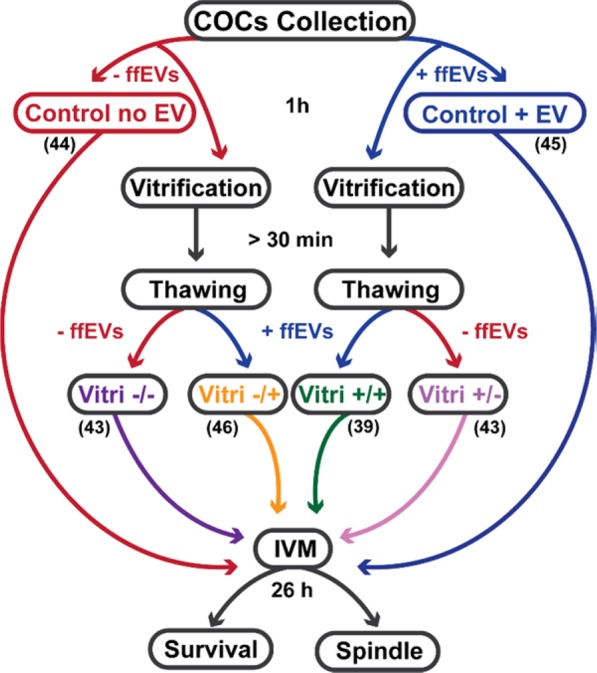

Study 2: Effect of follicular fluid EV on oocyte vitrification

Domestic cat COCs (n = 15 cats, 267 oocytes) were co-incubated in the absence (with PBS) or presence of 1.5 ×107 particles ml−1 unlabeled ffEV (diluted in PBS) at 5% CO2 and 38 °C for 1 hour. A subset of oocytes was then in vitro matured as fresh controls (n = 44 oocytes without ffEV, n = 45 with ffEV), and the remaining oocytes were vitrified in the presence or absence of ffEV at the same concentration in equilibration and vitrification solutions. COCs were maintained in liquid nitrogen for at least 30 minutes before being thawed (with or without ffEV) and subjected to in vitro maturation (Fig. 8).

Figure 8.

Experimental design of ffEVs-COCs incubation, vitrification and thawing. Number written in each group indicates the number of oocytes used for vitrification/maturation experiments.

Statistical Analysis

Data are presented as means ± standard deviation (SD). Comparisons in oocyte viability and maturation stage among treatments were evaluated by the Friedman non-parametric analysis of variance (GraphPad PRISM 7, GraphPad Software, USA). Comparisons in oocyte maturation between control and vitrification group and between vitrification with/without ffEV treatment were evaluated via Kaplan-Meier (displayed as log-rank prob > ChiSquare) with oocyte maturation stage coded as a continuous variable (germinal vesicle = 0, germinal vesicle breakdown = 1… Metaphase II = 6) in JMP Pro 12 (SAS Institute Inc., USA). Differences were considered significant at p < 0.05.

Supplementary information

Acknowledgements

The authors would like to thank Dr. Pierre Comizzoli (Smithsonian Conservation Biology Institute, USA) for providing the tubulin antibody and Alpha Nano Tech for analyzing EVs samples by NTA and TEM. The authors would also like to thank the Smithsonian Institution and the National Institute of Health 1F32HD090854-01A1 (JBN) for their financial support for this project. This research was also supported by a Research Fellowship (19J40191) and partly supported by KAKENHI (Grant-in-aid for Young Scientist (B); 17K15055) from the Japan Society for Promotion of Science to MF.

Author contributions

M.A.M.M.F. design and performed experiments, analyzed the proteomics data and wrote the manuscript. M.F. acquired and analyzed data, and revised the manuscript. J.B.N. acquired and analyzed data, designed experiments and revised the manuscript. M.J.N. analyzed proteomics data and revised the manuscript. M.I.-M. and N.S. supervised MA.M.M.F., M.F. and J.B.N., acquired funding and revised the manuscript. All authors revised and approved the manuscript.

Data availability

The authors declare that all data supporting the findings of this study are available within the article, Supplementary Files, or from the corresponding author upon reasonable request. UPLC-MS/MS (mzML) file has been deposited in FIGSHARE database under DOI number: 10.6084/m9.figshare.7837331.

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Footnotes

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

These authors contributed equally: Marcia de Almeida Monteiro Melo Ferraz and Mayako Fujihara.

Supplementary information

is available for this paper at 10.1038/s41598-020-65497-w.

References

- 1.Argyle CE, Harper JC, Davies MC. Oocyte cryopreservation: Where are we now? Hum. Reprod. Update. 2016;22:440–449. doi: 10.1093/humupd/dmw007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Tharasanit T, et al. Birth of kittens after the transfer of frozen-thawed embryos produced by intracytoplasmic sperm injection with spermatozoa collected from cryopreserved testicular tissue. Reprod. Domest. Anim. 2012;47:305–308. doi: 10.1111/rda.12072. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Fernandez-Gonzalez L, Jewgenow K. Cryopreservation of feline oocytes by vitrification using commercial kits and slush nitrogen technique. Reprod. Domest. Anim. 2017;52:230–234. doi: 10.1111/rda.12837. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Turathum B, et al. Missing and overexpressing proteins in domestic cat oocytes following vitrification and in vitro maturation as revealed by proteomic analysis. Biol. Res. 2018;51:27. doi: 10.1186/s40659-018-0176-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Saragusty J, Arav A. Current progress in oocyte and embryo cryopreservation by slow freezing and vitrification. Reproduction. 2011;141:1–19. doi: 10.1530/REP-10-0236. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Clark NA, Swain JE. Oocyte cryopreservation: Searching for novel improvement strategies. J. Assist. Reprod. Genet. 2013;30:865–875. doi: 10.1007/s10815-013-0028-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Songsasen Nucharin, Comizzoli Pierre. Reproductive Medicine and Assisted Reproductive Techniques. 2009. A Historical Overview of Embryo and Oocyte Preservation in the World of Mammalian In Vitro Fertilization and Biotechnology; pp. 1–11. [Google Scholar]

- 8.Kuwayama M. Highly efficient vitrification for cryopreservation of human oocytes and embryos: The Cryotop method. Theriogenology. 2007;67:73–80. doi: 10.1016/j.theriogenology.2006.09.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Galiguis J, Gómez MC, Leibo SP, Pope CE. Birth of a domestic cat kitten produced by vitrification of lipid polarized in vitro matured oocytes. Cryobiology. 2014;68:459–466. doi: 10.1016/j.cryobiol.2014.02.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Tong XH, Wu LM, Jin RT, Luan HB, Liu YS. Human oocyte vitrification with corona radiata, in autologous follicular fluid supplemented with ethylene glycol, preserves conventional IVF potential: Birth of four healthy babies. Reprod. Fertil. Dev. 2014;26:1001–1006. doi: 10.1071/RD13161. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Ortiz-Escribano N, et al. An improved vitrification protocol for equine immature oocytes, resulting in a first live foal. Equine Vet. J. 2018;50:391–397. doi: 10.1111/evj.12747. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Valojerdi MR, Salehnia M. Developmental potential and ultrastructural injuries of metaphase II (MII) mouse oocytes after slow freezing or vitrification. J. Assist. Reprod. Genet. 2005;22:119–127. doi: 10.1007/s10815-005-4876-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Luvoni GC, Pellizzari P. Embryo development in vitro of cat oocytes cryopreserved at different maturation stages. Theriogenology. 2000;53:1529–1540. doi: 10.1016/S0093-691X(00)00295-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Kuleshova LL, Lopata A. Vitrification can be more favorable than slow cooling. Fertility and Sterility. 2002;78:449–454. doi: 10.1016/s0015-0282(02)03305-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Okotrub KA, Mokrousova VI, Amstislavsky SY, Surovtsev NV. Lipid droplet phase transition in freezing cat embryos and oocytes probed by raman spectroscopy. Biophys. J. 2018;115:577–587. doi: 10.1016/j.bpj.2018.06.019. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Colombo M, Morselli MG, Tavares MR, Apparicio M, Luvoni GC. Developmental competence of domestic cat vitrified oocytes in 3D enriched culture conditions. Animals. 2019;9:329. doi: 10.3390/ani9060329. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Apparicio M, Ruggeri E, Luvoni GC. Vitrification of immature feline oocytes with a commercial kit for bovine embryo vitrification. Reprod. Domest. Anim. 2013;48:240–244. doi: 10.1111/j.1439-0531.2012.02138.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Morató R, et al. Effects of pre-treating in vitro-matured bovine oocytes with the cytoskeleton stabilizing agent taxol prior to vitrification. Mol. Reprod. Dev. 2008;75:191–201. doi: 10.1002/mrd.20725. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Horvath G, Seidel GE. Use of fetuin before and during vitrification of bovine oocytes. Reprod. Domest. Anim. 2008;43:333–338. doi: 10.1111/j.1439-0531.2007.00905.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Zhou XL, Al Naib A, Sun DW, Lonergan P. Bovine oocyte vitrification using the Cryotop method: Effect of cumulus cells and vitrification protocol on survival and subsequent development. Cryobiology. 2010;61:66–72. doi: 10.1016/j.cryobiol.2010.05.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Prentice-Biensch JR, Singh J, Mapletoft RJ, Anzar M. Vitrification of immature bovine cumulus-oocyte complexes: Effects of cryoprotectants, the vitrification procedure and warming time on cleavage and embryo development. Reprod. Biol. Endocrinol. 2012;10:1. doi: 10.1186/1477-7827-10-73. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Otoi T, et al. Cryopreservation of mature bovine oocytes following centrifugation treatment. Cryobiology. 1997;34:36–41. doi: 10.1006/cryo.1996.1988. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Horvath G, Seidel GE. Vitrification of bovine oocytes after treatment with cholesterol-loaded methyl-β-cyclodextrin. Theriogenology. 2006;66:1026–1033. doi: 10.1016/j.theriogenology.2006.03.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Guo Y, Yang Y, Yi X, Zhou X. Microfluidic method reduces osmotic stress injury to oocytes during cryoprotectant addition and removal processes in porcine oocytes. Cryobiology. 2019;90:63–70. doi: 10.1016/j.cryobiol.2019.08.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Smith GD, Takayama S. Application of microfluidic technologies to human assisted reproduction. Mol. Hum. Reprod. 2017;23:257–268. doi: 10.1093/molehr/gaw076. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Ambekar AS, et al. Proteomic analysis of human follicular fluid: A new perspective towards understanding folliculogenesis. J. Proteomics. 2013;87:68–77. doi: 10.1016/j.jprot.2013.05.017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Matzuk MM. Intercellular communication in the mammalian ovary: Oocytes carry the conversation. Science (80-.). 2002;296:2178–2180. doi: 10.1126/science.1071965. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Santonocito M, et al. Molecular characterization of exosomes and their microRNA cargo in human follicular fluid: Bioinformatic analysis reveals that exosomal microRNAs control pathways involved in follicular maturation. Fertil. Steril. 2014;102:1751–1761.e1. doi: 10.1016/j.fertnstert.2014.08.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Hailay T, et al. Extracellular vesicle-coupled miRNA profiles in follicular fluid of cows with divergent post-calving metabolic status. Sci. Rep. 2019;9:1–14. doi: 10.1038/s41598-019-49029-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Franz C, et al. Extracellular vesicles in human follicular fluid do not promote coagulation. Reprod. Biomed. Online. 2016;33:652–655. doi: 10.1016/j.rbmo.2016.08.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Morales Dalanezi F, et al. Extracellular vesicles of follicular fluid from heat-stressed cows modify the gene expression of in vitro-matured oocytes. Anim. Reprod. Sci. 2019;205:94–104. doi: 10.1016/j.anireprosci.2019.04.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.da Silveira JC, Veeramachaneni DNR, Winger QA, Carnevale EM, Bouma GJ. Cell-secreted vesicles in equine ovarian follicular fluid contain miRNAs and proteins: A possible new form of cell communication within the ovarian follicle. Biol. Reprod. 2012;86:1–10. doi: 10.1095/biolreprod.111.093252. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Hung, W.-T., Hong, X., Christenson, L. K. & McGinnis, L. K. Extracellular vesicles from bovine follicular fluid support cumulus expansion. Biol. Reprod.93, 1–9 (2015). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 34.Raposo G, Stoorvogel W. Extracellular vesicles: Exosomes, microvesicles, and friends. J. Cell Biol. 2013;200:373–383. doi: 10.1083/jcb.201211138. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Kalra H, Drummen G, Mathivanan S. Focus on extracellular vesicles: Introducing the next small big thing. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2016;17:170. doi: 10.3390/ijms17020170. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Lötvall J, et al. Minimal experimental requirements for definition of extracellular vesicles and their functions: A position statement from the International Society for Extracellular Vesicles. J. Extracell. Vesicles. 2014;3:1–6. doi: 10.3402/jev.v3.26913. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Diez-Fraile A, et al. Age-associated differential microRNA levels in human follicular fluid reveal pathways potentially determining fertility and success of in vitro fertilization. Hum. Fertil. 2014;17:90–98. doi: 10.3109/14647273.2014.897006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Martinez RM, et al. Extracellular microRNAs profile in human follicular fluid and IVF outcomes. Sci. Rep. 2018;8:1–10. doi: 10.1038/s41598-018-35379-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Andronico F, et al. Extracellular vesicles in human oogenesis and implantation. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2019;20:2162. doi: 10.3390/ijms20092162. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Saez F, Frenette G, Sullivan R. Epididymosomes and prostasomes: their roles in posttesticular maturation of the sperm cells. J. Androl. 2003;24:149–154. doi: 10.1002/j.1939-4640.2003.tb02653.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Rowlison T, Ottinger MA, Comizzoli P. Key factors enhancing sperm fertilizing ability are transferred from the epididymis to the spermatozoa via epididymosomes in the domestic cat model. J. Assist. Reprod. Genet. 2018;35:221–228. doi: 10.1007/s10815-017-1083-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Fereshteh Z, Bathala P, Galileo DS, Martin-DeLeon PA, Martin‐DeLeon PA. Detection of extracellular vesicles in the mouse vaginal fluid: Their delivery of sperm proteins that stimulate capacitation and modulate fertility. J. Cell. Physiol. 2019;234:12745–12756. doi: 10.1002/jcp.27894. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Smith JA, Daniel R. Human vaginal fluid contains exosomes that have an inhibitory effect on an early step of the HIV-1 life cycle. AIDS. 2016;30:2611–2616. doi: 10.1097/QAD.0000000000001236. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Burns Gregory, Brooks Kelsey, Wildung Mark, Navakanitworakul Raphatphorn, Christenson Lane K., Spencer Thomas E. Extracellular Vesicles in Luminal Fluid of the Ovine Uterus. PLoS ONE. 2014;9(3):e90913. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0090913. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Greening, D. W., Nguyen, H. P. T., Elgass, K., Simpson, R. J. & Salamonsen, L. A. Human endometrial exosomes contain hormone-specific cargo modulating trophoblast Adhesive capacity: Insights into endometrial-embryo interactions. Biol. Reprod.94, 1–15 (2016). [DOI] [PubMed]

- 46.Bidarimath M, et al. Extracellular vesicle mediated intercellular communication at the porcine maternal-fetal interface: A new paradigm for conceptus-endometrial cross-talk. Sci. Rep. 2017;7:40476. doi: 10.1038/srep40476. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Bathala, P. et al. Oviductal extracellular vesicles (oviductosomes, OVS) are conserved in humans: Murine OVS play a pivotal role in sperm capacitation and fertility. MHR Basic Sci. Reprod. Med.24, 143–157 (2018). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 48.Almiñana C, et al. Oviduct extracellular vesicles protein content and their role during oviduct–embryo cross-talk. Reproduction. 2017;154:253–268. doi: 10.1530/REP-17-0054. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Al-Dossary AA, Strehler EE, Martin-DeLeon PA. Expression and secretion of plasma membrane Ca2+-ATPase 4a (PMCA4a) during murine estrus: Association with oviductal exosomes and uptake in sperm. PLoS One. 2013;8:1–14. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0080181. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Ferraz M, et al. Oviductal extracellular vesicles interact with the spermatozoon’s head and mid-piece and improves its motility and fertilizing ability in the domestic cat. Sci. Rep. 2019;9:9484. doi: 10.1038/s41598-019-45857-x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Hong X, Schouest B, Xu H. Effects of exosome on the activation of CD4+ T cells in rhesus macaques: A potential application for HIV latency reactivation. Sci. Rep. 2017;7:1–9. doi: 10.1038/s41598-017-15961-x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Foster BP, et al. Extracellular vesicles in blood, milk and body fluids of the female and male urogenital tract and with special regard to reproduction. Crit. Rev. Clin. Lab. Sci. 2016;53:379–395. doi: 10.1080/10408363.2016.1190682. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Combelles CMH, Cekleniak NA, Racowsky C, Albertini DF. Assessment of nuclear and cytoplasmic maturation in in-vitro matured human oocytes. Hum. Reprod. 2002;17:1006–16. doi: 10.1093/humrep/17.4.1006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Comizzoli P, Pukazhenthi BS, Wildt DE. The competence of germinal vesicle oocytes is unrelated to nuclear chromatin configuration and strictly depends on cytoplasmic quantity and quality in the cat model. Hum. Reprod. 2011;26:2165–77. doi: 10.1093/humrep/der176. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Théry C, et al. Minimal information for studies of extracellular vesicles 2018 (MISEV2018): a position statement of the International Society for Extracellular Vesicles and update of the MISEV2014 guidelines. J. Extracell. Vesicles. 2018;7:1535750. doi: 10.1080/20013078.2018.1535750. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Burns GW, Brooks KE, Spencer TE. Extracellular vesicles originate from the conceptus and uterus during early pregnancy in sheep. Biol. Reprod. 2016;94:1–11. doi: 10.1095/biolreprod.115.134973. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Zamah AM, Hassis ME, Albertolle ME, Williams KE. Proteomic analysis of human follicular fluid from fertile women. Clin. Proteomics. 2015;12:5. doi: 10.1186/s12014-015-9077-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Bindea G, et al. ClueGO: a Cytoscape plug-in to decipher functionally grouped gene ontology and pathway annotation networks. Bioinformatics. 2009;25:1091–3. doi: 10.1093/bioinformatics/btp101. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Kanehisa Minoru, Sato Yoko. KEGG Mapper for inferring cellular functions from protein sequences. Protein Science. 2019;29(1):28–35. doi: 10.1002/pro.3711. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Kanehisa M, Goto S. KEGG: kyoto encyclopedia of genes and genomes. Nucleic Acids Res. 2000;28:27–30. doi: 10.1093/nar/28.1.27. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Kanehisa M, Sato Y, Furumichi M, Morishima K, Tanabe M. New approach for understanding genome variations in KEGG. Nucleic Acids Res. 2019;47:D590–D595. doi: 10.1093/nar/gky962. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Kanehisa M. Toward understanding the origin and evolution of cellular organisms. Protein Sci. 2019;28:1947–1951. doi: 10.1002/pro.3715. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Babayev E, Seli E. Oocyte mitochondrial function and reproduction. Curr. Opin. Obstet. Gynecol. 2015;27:175–181. doi: 10.1097/GCO.0000000000000164. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Buschiazzo J, et al. Cholesterol depletion disorganizes oocyte membrane rafts altering mouse fertilization. PLoS One. 2013;8:e62919. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0062919. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Mori M, et al. An Arp2/3 nucleated F-actin shell fragments nuclear membranes at nuclear envelope breakdown in starfish oocytes. Curr. Biol. 2014;24:1421–1428. doi: 10.1016/j.cub.2014.05.019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Duan X, Sun SC. Actin cytoskeleton dynamics in mammalian oocyte meiosis. Biol. Reprod. 2019;100:15–24. doi: 10.1093/biolre/ioy163. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Spindler RE, Pukazhenthi BS, Wildt DE. Oocyte metabolism predicts the development of cat embryos to blastocyst in vitro. Mol. Reprod. Dev. 2000;56:163–71. doi: 10.1002/(SICI)1098-2795(200006)56:2<163::AID-MRD7>3.0.CO;2-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Inoue M, Naito K, Nakayama T, Sato E. Mitogen-activated protein kinase translocates into the germinal vesicle and induces germinal vesicle breakdown in porcine oocytes. Biol. Reprod. 1998;58:130–136. doi: 10.1095/biolreprod58.1.130. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Russell DL, Salustri A. Extracellular matrix of the cumulus-oocyte complex. Semin. Reprod. Med. 2006;24:217–227. doi: 10.1055/s-2006-948551. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Rinehart JP, et al. Continuous up-regulation of heat shock proteins in larvae, but not adults, of a polar insect. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 2006;103:14223–14227. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0606840103. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Feder ME, Hofmann GE. Heat-shock proteins, molecular chaperones, and the stress response: Evolutionary and Ecological Physiology. Annu. Rev. Physiol. 1999;61:243–282. doi: 10.1146/annurev.physiol.61.1.243. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Ma F, Hou L, Yang L. Txndc9 is required for meiotic maturation of mouse oocytes. Biomed Res. Int. 2017;2017:1–9. doi: 10.1155/2017/6265890. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Fléchon JE, et al. The extracellular matrix of porcine mature oocytes: Origin composition and presumptive roles. Reprod. Biol. Endocrinol. 2003;1:1–13. doi: 10.1186/1477-7827-1-124. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Zhuo L, Kimata K. Cumulus oophorus extracellular matrix: Its construction and regulation. Cell Struct. Funct. 2001;26:189–196. doi: 10.1247/csf.26.189. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Eppig JJ, et al. Oocyte control of granulosa cell development: how and why. Hum. Reprod. 1997;12:127–32. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Hung WT, et al. Stage-specific follicular extracellular vesicle uptake and regulation of bovine granulosa cell proliferation. Biol. Reprod. 2017;97:644–655. doi: 10.1093/biolre/iox106. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Mulcahy LA, Pink RC, Carter DRF. Routes and mechanisms of extracellular vesicle uptake. J. Extracell. Vesicles. 2014;3:1–14. doi: 10.3402/jev.v3.24641. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Roberts-Dalton HD, et al. Fluorescence labelling of extracellular vesicles using a novel thiol-based strategy for quantitative analysis of cellular delivery and intracellular traffic. Nanoscale. 2017;9:13693–13706. doi: 10.1039/c7nr04128d. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Ofir-Birin Y, et al. Monitoring extracellular vesicle cargo active uptake by imaging flow cytometry. Front. Immunol. 2018;9:8–10. doi: 10.3389/fimmu.2018.01011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80.Laulagnier K, et al. Characterization of exosome subpopulations from RBL-2H3 cells using fluorescent lipids. Blood Cells, Mol. Dis. 2005;35:116–121. doi: 10.1016/j.bcmd.2005.05.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81.Lange-Consiglio A, et al. Oviductal microvesicles and their effect on in vitro maturation of canine oocytes. Reproduction. 2017;154:167–180. doi: 10.1530/REP-17-0117. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82.Fasano G, Demeestere I, Englert Y. In-vitro maturation of human oocytes: Before or after vitrification? J. Assist. Reprod. Genet. 2012;29:507–512. doi: 10.1007/s10815-012-9751-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83.Quan GB, et al. Meiotic maturation and developmental capability of ovine oocytes at germinal vesicle stage following vitrification using different cryodevices. Cryobiology. 2016;72:33–40. doi: 10.1016/j.cryobiol.2015.11.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 84.McGinnis LK, Kinsey WH. Role of focal adhesion kinase in oocyte-follicle communication. Mol. Reprod. Dev. 2015;82:90–102. doi: 10.1002/mrd.22446. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 85.Steed E, Balda MS, Matter K. Dynamics and functions of tight junctions. Trends Cell Biol. 2010;20:142–149. doi: 10.1016/j.tcb.2009.12.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 86.Zhang M, Ouyang H, Xia G. The signal pathway of gonadotrophins-induced mammalian oocyte meiotic resumption. Mol. Hum. Reprod. 2009;15:399–409. doi: 10.1093/molehr/gap031. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 87.Andrade GM, Meirelles FV, Perecin F, da Silveira JC. Cellular and extracellular vesicular origins of miRNAs within the bovine ovarian follicle. Reprod. Domest. Anim. 2017;52:1036–1045. doi: 10.1111/rda.13021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 88.Machtinger R, Laurent LC, Baccarelli AA. Extracellular vesicles: Roles in gamete maturation, fertilization and embryo implantation. Hum. Reprod. Update. 2016;22:182–193. doi: 10.1093/humupd/dmv055. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 89.Lee S-K, et al. The association of mitochondrial potential and copy number with pig oocyte maturation and developmental potential. J. Reprod. Dev. 2014;60:128–35. doi: 10.1262/jrd.2013-098. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 90.Ge H, et al. The importance of mitochondrial metabolic activity and mitochondrial DNA replication during oocyte maturation in vitro on oocyte quality and subsequent embryo developmental competence. Mol. Reprod. Dev. 2012;79:392–401. doi: 10.1002/mrd.22042. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 91.Ducheyne KD, Rizzo M, Daels PF, Stout TAE, De Ruijter-Villani M. Vitrifying immature equine oocytes impairs their ability to correctly align the chromosomes on the MII spindle. Reprod. Fertil. Dev. 2019;31:1330–1338. doi: 10.1071/RD18276. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 92.Egerszegi I, et al. Comparison of cytoskeletal integrity, fertilization and developmental competence of oocytes vitrified before or after in vitro maturation in a porcine model. Cryobiology. 2013;67:287–292. doi: 10.1016/j.cryobiol.2013.08.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 93.Larman MG, Minasi MG, Rienzi L, Gardner DK. Maintenance of the meiotic spindle during vitrification in human and mouse oocytes. Reprod. Biomed. Online. 2007;15:692–700. doi: 10.1016/s1472-6483(10)60537-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 94.Curci A, Bevilacqua A, Fiorenza MT, Mangia F. Developmental regulation of heat-shock response in mouse oogenesis: Identification of differentially responsive oocyte classes during Graafian follicle development. Dev. Biol. 1991;144:362–368. doi: 10.1016/0012-1606(91)90428-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 95.Curci A, Bevilacqua A, Mangia F. Lack of heat-shock response in preovulatory mouse oocytes. Dev. Biol. 1987;123:154–160. doi: 10.1016/0012-1606(87)90437-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 96.Matos JE, et al. Conjugated linoleic acid improves oocyte cryosurvival through modulation of the cryoprotectants influx rate. Reprod. Biol. Endocrinol. 2015;13:60. doi: 10.1186/s12958-015-0059-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 97.Edashige K. Permeability of the plasma membrane to water and cryoprotectants in mammalian oocytes and embryos: Its relevance to vitrification. Reprod. Med. Biol. 2017;16:36–39. doi: 10.1002/rmb2.12007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 98.Helwa I, et al. A comparative study of serum exosome isolation using differential ultracentrifugation and three commercial reagents. PLoS One. 2017;12:1–22. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0170628. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 99.Hughes CS, et al. Single-pot, solid-phase-enhanced sample preparation for proteomics experiments. Nat. Protoc. 2019;14:68–85. doi: 10.1038/s41596-018-0082-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 100.Bjornson RD, et al. X!!Tandem, an improved method for running X!Tandem in parallel on collections of commodity computers. J. Proteome Res. 2008;7:293–299. doi: 10.1021/pr0701198. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 101.Maclean, B., Eng, J. K., Beavis, R. C. & Mcintosh, M. General framework for developing and evaluating database scoring algorithms using the TANDEM search engine. 22, 2830–2832 (2006). [DOI] [PubMed]

- 102.Geer LY, et al. Open mass spectrometry search algorithm. J. Proteome Res. 2004;3:958–964. doi: 10.1021/pr0499491. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 103.Sturm M, et al. OpenMS – An open-source software framework for mass spectrometry. BMC Bioinformatics. 2008;9:163. doi: 10.1186/1471-2105-9-163. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 104.Winter D. J. rentrez: An R package for the NCBI eUtils API. R J. 2017;9:520–526. [Google Scholar]

- 105.Comizzoli P, Wildt DE, Pukazhenthi BS. In vitro compaction of germinal vesicle chromatin is beneficial to survival of vitrified cat oocytes. Reprod. Domest. Anim. 2009;44(Suppl 2):269–74. doi: 10.1111/j.1439-0531.2009.01372.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 106.Lee P-C, Wildt DE, Comizzoli P. Proteomic analysis of germinal vesicles in the domestic cat model reveals candidate nuclear proteins involved in oocyte competence acquisition. MHR Basic Sci. Reprod. Med. 2018;24:14–26. doi: 10.1093/molehr/gax059. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 107.Rajaei F, Abedpour N, Salehnia M, Jahanihashemi H. The effect of vitrification on mouse Oocyte apoptosis by cryotop method. Iran. Biomed. J. 2013;17:200–205. doi: 10.6091/ibj.1184.2013. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 108.Holubcová Z, Blayney M, Elder K, Schuh M. Error-prone chromosome-mediated spindle assembly favors chromosome segregation defects in human oocytes. Obstet. Gynecol. Surv. 2015;70:572–573. doi: 10.1126/science.aaa9529. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Data Availability Statement

The authors declare that all data supporting the findings of this study are available within the article, Supplementary Files, or from the corresponding author upon reasonable request. UPLC-MS/MS (mzML) file has been deposited in FIGSHARE database under DOI number: 10.6084/m9.figshare.7837331.