Abstract

The production of enzymes involved in lignin degradation (laccase, ligninase), carbon cycling (β-glucosidase), and phosphorous cycling (phosphomonoesterase) by white rot fungi (Pleurotus sajor-caju) was studied. In the presence of chlorpyrifos, carbofuran, and their mixture, laccase activity was highest on the 7th day, i.e., 192.5 ± 0.31 U ml− 1, 213.6 ± 0.31 U ml− 1, and 164.6 ± 0.31 U ml− 1, respectively, compared to the control which produced maximum laccase on the 14th day (126.9 ± 0.15 U ml− 1). Phosphomonoesterase activity in the presence of chlorpyrifos, carbofuran, and their mixture was 31.5 ± 0.25, 24.1 ± 0.15, and 29.2 ± 0.35 µg PNP min−1 ml−1, respectively, which was more than the control on the 21st day (11.63 ± 0.21 µg PNP min−1 ml−1). β-Glucosidase production increased with the days of incubation in the presence of pesticides than in the control. β-Glucosidase activity on the 21st day in the presence of chlorpyrifos, carbofuran, and their mixture was 32.4 ± 0.1, 24.2 ± 0.3, and 28.4 ± 0.25 µg PNP min−1 ml−1, respectively, as compared to control (15.3 ± 0.6 µg PNP min−1 ml−1). Thus, chlorpyrifos, carbofuran, and their mixture were found to have a positive effect on the production of laccase, β-glucosidase, and phosphomonoesterase by P. sajor-caju, which can use these pesticides as a source of their nutrition, thereby improving the health of pesticide-polluted soils.

Keywords: White rot fungi, Laccase, β-Glucosidase, Phosphomonoesterase, Chlorpyrifos, Carbofuran

Introduction

Lignin is a poly-phenolic biopolymer which provides structure and strength to the plant and is synthesized in plants through random peroxidase-catalyzed polymerisation of substituted p-hydroxycinnamyl alcohols, i.e., coniferyl, sinapyl, and p-coumaryl alcohol (Brandt et al. 2015). The content of lignin in the plant varies from 10 to 30% depending on the source of the plant (Chatel and Rogers 2013). The physiological importance of lignin biodegradation is the destruction of the matrix that is formed by it to release hemicelluloses and cellulose so that the microorganism can gain better access to those real substrates for obtaining energy (Canet et al. 2001). Thus, lignin degradation is an important aspect of carbon recycling in the biosphere, which is facilitated by lignin-degrading microorganisms (Bozell and Petersen 2010).

White rot fungi comprise of fungi capable of degrading lignin (a heterogeneous polyphenolic polymer) extensively within lignocellulosic substrates. They also have the ability to detoxify various pollutants because of their inherent capacity to secrete various extracellular enzymes such as laccase, β-glucosidase, and phosphomonoesterase enzymes. These enzymes are involved with carbon and phosphorous cycling so that pollutants can be used by white rot fungi as a source of nutrition.

The usage of pesticides in India is about 0.5 kg/ha, of which the major contribution is from organochlorine, organophosphorous, and carbamate pesticides. The usage of organophosphates and carbamate pesticide has increased in the recent years. It has been reported that about 5% of the total applied pesticides is able to hit the target pests, while the rest enters into soil and water resources (Nawaz et al. 2011). Among organophosphate pesticides, chlorpyrifos [O,O-diethyl O-(3,5,6-trichloro-2-pyridyl) phosphorothioate)] is one of the most widely used insecticides for foliar and soil applications (Bhalerao 2012). The carbofuran (2,3-dihydro-2, 2-dimethyl-7-benzo-furanyl méthylcarbamate) belonging to the class of N-methyl carbamate pesticides is extensively used as a soil-incorporated insecticide/nematicide to control a variety of insect pests.

Thus, the present study was conducted to determine the effect of chlorpyrifos and carbofuran individually as well as their mixture (to mimic the presence of these pesticides in the ecosystem) on the secretion of laccase, β-glucosidase, and phosphomonoesterase by white rot fungi, Pleurotus sajor-caju.

Materials and methods

Chlorpyrifos and carbofuran

The pesticides, viz. carbofuran 3% EC and chlorpyrifos 20% EC used in the study were purchased from a local trader. Stock solutions of 1000 ppm were prepared by dissolving carbofuran and chlorpyrifos in methanol and then storing in amber bottles at 4º C.

White rot fungi

Pure culture of P. sajor-caju (DMRP-112) was obtained from the Division of Plant Pathology, SKUAST-Jammu (India). The culture was grown on potato dextrose agar and maintained at 28 °C.

In vitro screening for toxicity tolerance to pesticide concentrations

Growth of P. sajor-caju in the presence of pesticides

Chlorpyrifos 20% EC and carbofuran 3% EC were added to the molten Soil Extract Agar medium (HiMedia, India) individually at 100, 150, and 200 ppm, and as a mixture of pesticides in the ratio 1:20 (chlorpyrifos:carbofuran) to make total concentrations of 100, 150, and 200 ppm. The medium was poured into 9-cm Petri plates, and these were centrally inoculated with a 4-mm agar plug taken from the margin of a growing colony of Pleurotus sajor-caju. The plates were incubated at 28º C in the BOD incubator, and the growth of P. sajor-caju was measured at regular intervals up to 21 days of incubation. EC50 (the pesticide concentration that caused a 50% growth reduction in relation to the control) as well as the percent inhibition of growth for every treatment were recorded. The temporal growth was used to obtain the growth rates from the regression lines of the linear radial mycelial extension (Fragoeiro 2005). Experiments were carried out with three replicates per treatment.

Plate assay to assess lignin degradation

To assess the lignin-degrading ability of P. sajor-caju, the fungus was grown in lignin medium described by Sundman and Nase (1971). The medium was prepared with 0.25 g alkaline lignin, 5 g glucose, 5 g ammonium tartarate, 1 g malt extract, 0.5 g MgSO4∙7H2O, 0.01 g CaCl2∙2H2O, 0.1 g NaCl, 0.01 g FeCl3, 1 mg of thiamine, and 20 g of agar in a liter of distilled water, with pH adjusted to 4.5. To examine the ligninase enzyme production potential in the presence of pesticides, the medium was amended with chlorpyrifos and carbofuran individually and as a mixture as already described. The fungus was centrally inoculated and incubated at 15 °C for 15 days. After this period, color was developed by flooding with a reagent containing equal parts of 1% aqueous solution of FeCl3 and K3[Fe(CN)6]. A positive result was indicated by clear zones under or around the growth area of the lignin-degrading fungi. The halo zone was measured by taking two diametric measurements at right angles to each other to quantify ligninase activity.

Effect of pesticides on the production of various enzymes by P. sajor-caju under submerged conditions

Incubation conditions

Erlenmeyer flasks (250 ml) containing 100 ml of soil extract broth (Hi Media, India) were divided into four sets. The first set was amended with carbofuran (100 mg L− 1), the second set was amended with chlorpyrifos (100 mg L− 1), while the third set was amended with their mixture to give a final concentration of 100 mg L− 1. However, in the fourth set, which served as control, distilled water was used in place of pesticide. Four plugs of actively growing mycelium from 6-day-old culture of P. sajor-caju were inoculated in each flask and incubated at 28 ºC for 21 days with constant agitation at 150 rpm. All the treatments were replicated thrice. During the course of experiment, flasks with growing culture of P. sajor-caju from every set were taken out at different time intervals, i.e., on the 7th, 14th, and 21st days to estimate the fungal biomass and production of extracellular enzymes in the culture filtrate.

Sampling and dry weight determination

The biomass of fungus was determined by drying the mycelium (filtered through Whatman No. 1 filter paper) for 48 h at 80 °C until constant weight was achieved. However, the fresh filtrate obtained after harvesting the mycelia was centrifuged at 10,000 rpm (4 °C) and the supernatant obtained was used as a source of various enzymes.

pH determination

The pH of fresh filtrate broth obtained after each sampling period, i.e., the 7th day, 14th day, and 21st day, was determined using the pH meter (METTLER TOLEDO). 10 ml of broth was taken in a conical flask and the pH was recorded for each sample.

Enzyme activity

Laccase

Laccase activity (EC 1.10.3.2) was determined with ABTS (2,2-azino-bis(3-ethylbenzthiazoline-6-sulfonic acid) at 405 nm based on the protocol described by Buswell et al. (1995). The assay was carried out at ambient temperature with ABTS and buffer equilibrated at 37 °C. 1 ml of reaction mixture contained 850 μl of sodium acetate buffer (pH 5.0) and 100 μl of enzyme extract. The reaction was initiated by adding 50 μl of 0.55 mM ABTS. Laccase activity was computed from the increase in absorbance at 405 nm (A405); boiled enzyme was used as the control. One unit of activity was defined as the amount of enzyme producing a 0.001 increase in the optical density in 1 min.

β-Glucosidase and phosphomonoesterase

β-D-Glucosidase (EC 3.2.1.21) and phosphomonoesterase (EC 3.1.3.2) activities were assayed using 4-nitrophenyl-β-D-glucopyranoside and 4-nitrophenyl phosphate disodium salt, respectively, as substrates (Keshri and Magan, 2000). The reaction was started by adding 160 μl of enzyme extract, 80 μl of acetate buffer (0.05 M pH 4.85), and 160 μl of substrate (25 mM for 4-nitrophenyl-β-D-glucopyranoside and 15 mM for 4-nitrophenyl phosphate disodium salt) followed by incubation at 37 °C for 1 h. After 1 h, 20 μl of 1 M sodium carbonate solution was added to stop the reaction, and the reaction mixture was kept at room temperature for 3 min before reading the absorbance at 405 nm. The increase in absorbance corresponded to the liberation of p-nitrophenol by enzymatic hydrolysis of the substrate. Total enzymatic activity in the enzyme extract samples was determined by extrapolation from a calibration curve made with the 4-nitrophenol standards. The enzyme activity was expressed in µg p-nitrophenol released min− 1 ml− 1.

Statistical analysis

Data presented in tables and figures of the present study are means of three replicates and subjected to statistical analysis by one-way analysis of variance and Tukey’s test.

Results and discussion

In our study, the growth rate of fungi was determined to evaluate the effect of pesticides on its growth (Fig. 1). The pesticide concentrations showed strong impact on the relative growth rate of P. sajor-caju as shown in Fig. 2. The growth rate was found maximum at a pesticide concentration of 100 mg L− 1 and further decreased with increasing concentration of pesticides. The determination of fungal growth rates is very important as it provides an indication of the speed at which a fungus colonizes and transverses a substrate. Singleton (2001) suggested that to overcome competition from native soil microorganisms, the introduced fungi should have good growth rate. Results of the present study revealed that the fungi showed best growth at 100 mg L− 1 concentration of pesticides and accordingly this concentration was chosen for further study.

Fig. 1.

Growth of P. sajor-caju in the presence of different concentrations of a chlorpyrifos, b carbofuran, and c mixture of carbofuran and chlorpyrifos

Fig. 2.

Effect of different concentrations of pesticides on the growth rate of Pleurotus sajor-caju. Data presented in figure are means ± SD of three replicates analyzed using one-way analysis of variance and Tukey’s test. Mean bars for each sampling interval followed by the same letter are not significantly different (P > 0.05)

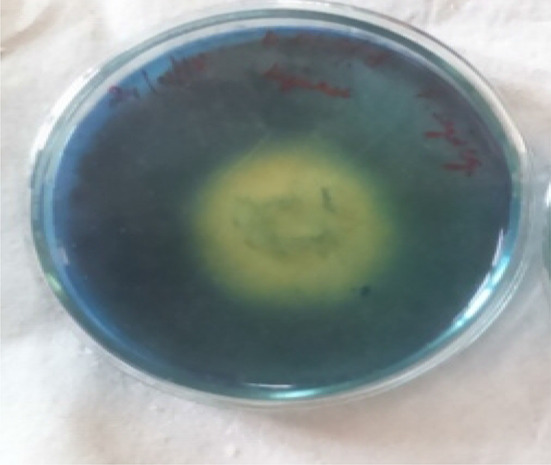

P. sajor-caju showed the positive test for ligninase activity in Petri plates (Figs. 3, 4). The results of the qualitative test for ligninase by P. sajor-caju in Petri plates revealed that ligninase production in the presence of chlorpyrifos and carbofuran individually, and their mixture (100 mg L− 1) was found to be 30.3 ± 0.06 mm, 26.1 ± 0.06, and 27.5 ± 0.05, respectively (Table 1). In the absence of pesticides, the ligninolytic activity of P. sajor-caju was found to be 40.3 ± 0.01 mm. P. sajor-caju was thus found to produce a good amount of ligninase in the presence of pesticide mixture.

Fig. 3.

Pleurotus sajor-caju showing positive test for ligninase production in plate assay

Fig. 4.

Pleurotus sajor-caju showing positive test for ligninase production in the presence of different concentrations of mixture of carbofuran and chlorpyrifos

Table 1.

Effect of different pesticide concentrations on ligninase production in plate assay by Pleurotus sajor-caju

| Pesticide | Ligninase activity of P. sajor-caju (mm) | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 0 ppm | 100 ppm | 150 ppm | 200 ppm | |

| Chlorpyrifos | 40.3 ± 0.01d | 30.3 ± 0.05c | 20.2 ± 0.01b | 15.1 ± 0.01a |

| Carbofuran | 40.3 ± 0.01d | 26.1 ± 0.06c | 23.3 ± 0.05b | 13.1 ± 0.01a |

| Mixture | 40.3 ± 0.01d | 27.5 ± 0.04c | 20.1 ± 0.01b | 10.5 ± 0.01a |

Mean values in each row with the same letter as superscript are significantly indifferent (P < 0.005)

The results from soil extract broth studies revealed that the biomass of P. sajor-caju in broth amended with pesticides was found to increase compared to the control (without pesticide) as shown in Table 2. On the 7th day of incubation, the biomass of P. sajor-caju in the presence of chlorpyrifos, carbofuran, and their mixture was found to be 1.68 ± 0.01 gl− 1, 1.59 ± 0.11 gl− 1, and 1.48 ± 0.21 gl− 1, respectively, whereas in the control, the biomass was 1.32 ± 0.12 gl− 1. The presence of chlorpyrifos, carbofuran, and their mixture positively affected the growth of P. sajor-caju and increased the biomass to 21.4%, 16.9%, and 10.8%, respectively, compared to the control. The increase in biomass due to the presence of pesticides in nutritionally weak media suggests that P. sajor-caju is able to utilize the pesticide as a source of carbon and nutrition for its growth. Biomass of P. sajor-caju increased with days of incubation. Kumari et al. (2019) also suggested the positive effect of chlorpyrifos on the biomass of Stereum ostrea. They reported an increase in the biomass of fungi in the presence of chlorpyrifos as compared to the control. However, El-Ghany and Masmal (2016) reported a decrease in the growth of Trichoderma harzianum and Metarhizium anisopliae at high concentrations of orthophosphate insecticides (diazinon, profenos, and malathion).

Table 2.

Biomass of Pleurotus sajor-caju in soil extract media

| Treatment (100 mgL− 1) |

Dry weight of mycelium gl− 1 of P. sajor-caju after growth | ||

|---|---|---|---|

| 7th day | 14th day | 21st day | |

|

Control (without pesticide) |

1.32 ± 0.12a | 2.44 ± 0.25a | 3.3 ± 0.12a |

| Chlorpyrifos | 1.68 ± 0.01d | 3.19 ± 0.11c | 4.07 ± 0.32c |

| Carbofuran | 1.59 ± 0.11c | 2.72 ± 0.21b | 3. 4 ± 0.25a |

| Mixture | 1.48 ± 0.21b | 2.4 ± 0.25a | 3.24 ± 0.15b |

Mean values in each column with the same letter as superscript are significantly indifferent (P < 0.005)

The pH of culture broth was found to increase with days of incubation. The pH changes in culture broth ranged from 5.21 to 6.91 with increase in the growth of P. sajor-caju during the course of the experiment (Table 3). This change may be attributed to the alkalinity of the media due to the production of metabolites during the degradation of pesticides.

Table 3.

Change in pH of the culture broth upon the growth of Pleurotus sajor-caju amended with chlorpyrifos, carbofuran, and their mixture

| Treatment (100 mgL− 1) |

pH of the broth culture of P. sajor-caju after growth | ||

|---|---|---|---|

| 7th day | 14th day | 21st day | |

|

Control (without pesticide) |

5.21a | 5.81a | 6.23a |

| Chlorpyrifos | 5.62c | 6.35b | 6.91c |

| Carbofuran | 5.51b | 6.54c | 6.82bc |

| Mixture | 5.53b | 6.42b | 6.75b |

Mean values in each column with the same letter as superscript are significantly indifferent (P < 0.005)

Laccase enzyme has already attracted considerable interest for the biodegradation of xenobiotic compounds with lignin-like structures (Trejo-Hernandez et al. 2001). The effect of pesticides on the production of laccase by P. sajor-caju after 7, 14, and 21 days is shown in Fig. 5. Laccase activity was highest on the 7th day in the presence of pesticides and it decreased after 1 week, whereas in the control, laccase activity increased until 14 days. The production of laccase increased to 56.9%, 61.1%, and 49.6% in the presence of chlorpyrifos, carbofuran, and their mixture, respectively. The production of laccase in control was the highest on the 14th day (126.9 ± 0.15 U ml− 1) whereas in the presence of chlorpyrifos, carbofuran, and their mixture, it was 83.2 ± 0.35 U ml− 1, 86.9 ± 0.35 U ml− 1, and 84.22 ± 0.35 U ml− 1, respectively. Similar results were reported by Fragoeiro (2005) who observed a huge increase in the production of laccase by P. ostreatus in the presence of pesticides. Trejo-Hernandez et al. (2001) suggested that a fungus showing laccase activity of 120–1000 Uml− 1 in compost is a potential commercial source for laccase.

Fig. 5.

Effect of chlorpyrifos, carbofuran, and their mixture on the production of laccase by Pleurotus sajor-caju on the 7th, 14th, and 21st days of incubation. Data presented in figure are means ± SD of three replicates. Mean bars for each sampling interval followed by the same letter are not significantly different (P > 0.05)

β-Glucosidase secretion in soil extract broth, which is a nutritionally weak medium in the absence and presence of pesticides, has been shown in Fig. 6. β-Glucosidase activity of P. sajor-caju on the 21stday was recorded to be 15.3 ± 0.6 µg PNP min− 1 ml−1 in the control, and it was observed to be 32.4 ± 0.1 µg PNP min− 1 ml−1 in the presence of chlorpyrifos, 24.2 ± 0.3 µg PNP min− 1 ml−1 in the presence of carbofuran, and 28.4 ± 0.25 µg PNP min− 1 ml−1 in the presence of chlorpyrifos and carbofuran mixture. Fragoeiro (2005) reported the strong inhibition of β-Glucosidase activity of Phanerochaete chrysosporium in the presence of mixture of pesticides (dieldrin, simazine, and trifluralin) and increased production of β-glucosidase by Trametes versicolor. As β-glucosidase is associated with the carbon cycle and the production of β-glucosidase is positively correlated with biomass, these results suggest that P. sajor-caju may have the ability to obtain carbon from the pesticides for its growth.

Fig. 6.

Effect of chlorpyrifos, carbofuran, and their mixture on the production of β-glucosidase by Pleurotus sajor-caju on the 7th, 14th, and 21st days. Data presented in figure are means ± SD of three replicates. Mean bars for each sampling interval followed by the same letter are not significantly different (P > 0.05)

Phosphomonoesterases are the enzyme that carry out specific hydrolysis and catalyze reactions involved in the transformation of phosphorous and thus form an essential component in substrate mineralization (Taylor et al. 2002). Phosphomonoesterase secretion by P. sajor-caju was found to increase with incubation period both in the control and in media spiked with pesticides as shown in Fig. 7. Phosphomonoesterase activity of P. sajor-caju in the presence of chlorpyrifos, carbofuran, and their mixture was found to be 31.5 ± 0.15, 21.7 ± 0.15, and 29.2 ± 0.153 µg PNP min− 1 ml− 1, respectively, whereas it was 11.6 ± 0.21 µg PNP min− 1 ml− 1 in the control. Fragoeiro (2005) reported that P. ostreatus and T. versicolor produced higher levels of this enzyme under osmotic stress, whereas T. versicolor and P. chrysosporium showed higher phosphomonoesterase production independent of the pesticide concentration.

Fig. 7.

Effect of chlorpyrifos, carbofuran, and their mixture on the production of phosphomonoesterase by Pleurotus sajor-caju on the 7th, 14th, and 21st days of incubation. Data presented in figure are means ± SD of three replicates. Mean bars for each sampling interval followed by the same letter are not significantly different (P > 0.05)

Conclusion

It may be concluded that the fungi P. sajor-caju is a good source for the production of laccase and β-glucosidase enzymes that have several biotechnological and industrial applications. Owing to their capability to produce these extracellular enzymes, P. sajor-caju can utilize organophosphates and carbamate pesticides as a source of carbon and nutrition. Thus, P. sajor-caju can further be exploited as a bioremediation agent to degrade several other xenobiotics.

Acknowledgements

The authors are highly thankful to the Division of Biochemistry, Faculty of Basic Sciences, SKUAST-J, for providing necessary facilities in carrying out the research work of Ph.D dissertation.

Compliance with ethical standards

Conflict of interest

On behalf of all authors, the corresponding author states that there is no conflict of interest.

References

- Bhalerao TS, Puranik PR. Biodegradation of organochlorine pesticide, endosulfan, by a fungal soil isolate, Aspergillus niger. Int Biodeterior Biodegrad. 2007;59:315–321. doi: 10.1016/j.ibiod.2006.09.002. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Bozell JJ, Petersen GR. Technology development for the production of bio based products from biorefinery carbohydrates—the US Department of Energy’s ‘Top 10’ revisited. Green Chem. 2010;12:539–554. doi: 10.1039/b922014c. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Brandt A, Chen L, van Dongen BE, Welton T, Hallett JP. Structural changes in lignins isolated using an acidic ionic liquid water mixture. Green Chem. 2015;17:5019–5034. doi: 10.1039/C5GC01314C. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Buswell J. Potential of Spent Mushroom Substrate for Bioremediation Purposes. Compost Sci Util. 1994;2:31–36. doi: 10.1080/1065657X.1994.10757931. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Canet R, Birnstingl J, Malcolm D, Lopez-Real J, Beck A. Biodegradation of polycyclic aromatic hydrocarbons (PAHs) by native microflora and combinations of white-rot fungi in a coal-tar contaminated soil. Bioresource Tech. 2001;76:113–117. doi: 10.1016/S0960-8524(00)00093-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chatel G, Rogers RD. Review: oxidation of lignin using ionic liquids—an innovative strategy to produce renewable chemicals. ACS Sustain Chem Eng. 2013;2:322–339. doi: 10.1021/sc4004086. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- El-Ghany A, Masmal IA. Fungal biodegradation of organophosphorus insecticides and their impact on soil microbial population. J Plant Pathol Microbiol. 2016;7(5):349. [Google Scholar]

- Fragoeiro S (2005) Use of fungi in bioremediation of pesticides. Dissertation, Cranfield University, Bedford, pp 3–217

- Keshri G, Magan N. Detection and differentiation between mycotoxigenic and non-mycotoxigenic strains of two Fusarium spp. using volatile production profiles and hydrolytic enzymes. J Appl Microb. 2000;89(5):825–833. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2672.2000.01185.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kumari BSS, Praveen K, Usha KY, Kumar KD, Reddy GPK, Reddy BR. Ligninolytic behavior of the white rot fungus Stereum ostrea under influence of culture conditions, inducers and chlorpyrifos. 3 Biotech. 2019;9:424–435. doi: 10.1007/s13205-019-1955-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nawaz K, Hussain K, Choudary N, Majeed A, Ilyas U, Ghani A, Lin F, Ali K, Afghan S, Raza G, Lashari MI. Eco-friendly role of biodegradation against agricultural pesticides hazards. Afr J Microbiol Res. 2011;5(3):177–183. [Google Scholar]

- Sundman V, Nase L. A simple plate test for direct visualization of biological lignin degradation. Pap Timber. 1971;53:67–71. [Google Scholar]

- Singleton I. Fungal remediation of soils contaminated with persistent organic pollutants. In: Gadd G, editor. Fungi in bioremediation. UK: Cambridge University Press; 2001. [Google Scholar]

- Taylor J, Wilson B, Mills M, Burns R. Comparison of microbial numbers and enzymatic activities in surface soils and subsoils using various techniques. Soil Biol Biochem. 2002;34:387–401. doi: 10.1016/S0038-0717(01)00199-7. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Trejo-Hernandez M, Lopez-Munguia A, Ramirez R. Residual compost of Agaricus bisporus as a source of crude laccase for enzymic oxidation of phenolic compounds. Process Biochem. 2001;36:635–639. doi: 10.1016/S0032-9592(00)00257-0. [DOI] [Google Scholar]