Abstract

Background

Real-world data of disease prevalence represents an important but underutilised source of evidence for health economic modelling.

Aims

The aim of this study was to estimate nationwide prevalence rates and summarise the characteristics of 199 chronic conditions using Danish population-based health registers, to provide an off-the-shelf tool for decision makers and researchers.

Methods

The study population comprised all Danish residents aged 16 years or above on 1 January 2013 (n = 4,555,439). The study was based on the linkage of national registers covering hospital contacts, contacts with primary care (including general practitioners) and filled-in out-of-hospital prescriptions.

Results

A total of 65.6% had one or more chronic condition. The ten conditions with the highest degree of prevalence were hypertension (23.3%), respiratory allergy (18.5%), disorders of lipoprotein metabolism (14.3%), depression (10.0%), bronchitis (9.2%), asthma (7.9%), type 2 diabetes (5.3%), chronic obstructive lung disease (4.7%), osteoarthritis of the knee (3.9%) and finally osteoporosis (3.5%) and ulcers (3.5%) in joint tenth place. Characteristics by gender, age and national geographical differences were also presented.

Conclusions

A nationwide catalogue of the prevalence rates and characteristics of patients with chronic conditions based on a nationwide population is provided. The prevalence rates of the 199 conditions provide important information on the burden of disease for use in healthcare planning, as well as for economic, aetiological and other research.

Electronic supplementary material

The online version of this article (10.1007/s41669-019-0167-7) contains supplementary material, which is available to authorized users.

Key Points for Decision Makers

| Real-world evidence of disease prevalence is important for estimating the burden of disease, cost of illness and budget impact of new health technologies. |

| The Danish civil registration number provides a unique opportunity to link different types of register data for an individual patient, thus providing the best possible information on the actual treatment of chronic diseases. |

| Nationwide register-based prevalence statistics for 199 chronic diseases show, for most disease areas, a higher current treatment level than that expected from epidemiological research. In 2013, almost two-thirds of the entire Danish population aged 16 years or above either had a hospital diagnosis or had been in medical treatment for one or more chronic condition. |

Introduction

Worldwide, the financial pressures on healthcare providers are increasing. To control the rising cost of healthcare, decision makers need access to real-world evidence of current treatment patterns [1, 2]. Real-world evidence of disease prevalence is important for estimating the burden of disease, cost of illness, and budget impact of new health technologies [3, 4]. In addition, it is important to obtain unbiased, independent documentation of disease burden, as there may be concerns with the cost-of-illness studies funded by companies [5].

The burden of chronic diseases is increasing rapidly in most countries. In Denmark, approximately 30–50% of the adult population have one or more chronic condition or long-standing illness [6–10]. Moreover, the burdens of chronic conditions are increasing [11–20]. The numbers and expenditure are growing along with an ageing population, and up to 80% of total healthcare costs can be attributed to chronic conditions [21–24]. Thus, the need for reliable and affordable estimates of the prevalence and disease burden of chronic conditions to guide decision-making in healthcare is increasing [24–26].

There are different ways to measure the prevalence of chronic conditions, varying from community-based health surveys and screening investigations to register-based studies. The choice of definitions and methods naturally affects which patients are included and hence the prevalence [27, 28].

The Scandinavian countries have an established tradition of documenting the diseases and hospital treatments of the entire population in registers; however, the registers have primarily been used to study individual conditions rather than to assess the total burden of chronic conditions [7, 24, 26, 29–34], or to forecast drug spending to help with decision-making [35, 36].

The aim of the present study was to estimate the national prevalence rates and to summarise the characteristics of 199 chronic conditions using the complete Danish population aged 16 and above. To the best of the authors’ knowledge, the current study is the most comprehensive, independent register-based attempt to estimate the full-population prevalence-based disease burden of chronic diseases.

Methods

Study Population

The nationwide study population and cohort consisted of 4,555,439 Danish residents who were alive and aged 16 years or above on 1 January 2013, of which 49.2% were men.

The Registers

In Scandinavian countries, general practitioners (GPs) and hospitals have a long-standing tradition of reporting diseases, treatments, medications and other treatment-related information. This is done at the micro level for national health registers. Register data are collected mostly for public administration such as claims and management, surveillance and control functions [37]. The comprehensiveness, scope and population completeness are unique to Denmark and other Scandinavian countries, enabling individual linkage across registers by means of the individual personal identification number assigned to each person [38]. The main register used was the Danish National Patient Register (NPR) [39], including the Danish Psychiatric Central Research Register [40], containing treating-physician-reported International Statistical Classification of Diseases, 10th Revision (ICD-10) hospital diagnoses. Moreover, to ensure the inclusion of patients not treated in hospitals, the National Health Service Register (NHSR) [41] and National Prescription Registry (TNPR) [42] were included in the study, since the NPR did not include diagnosis data from private specialist doctors or GPs. The NHSR contains data collected primarily for administrative purposes from health contractors in primary healthcare. It includes information about citizens, providers and health services, but minimal clinical information. Furthermore, the TNPR, comprising all prescribed and distributed medicines outside hospitals, was included to ensure the best possible identification of conditions and the representativeness thereof by clinical recommendation. All registers had a unique civil registration number for each person; furthermore, birth date, gender and other information were derived from the Danish Civil Registration System [43]. The registers used are described in more detail in other studies [44, 45]. Table 1 summarises the details of the registers used.

Table 1.

The registers used and characteristics of the selected population in summary

| Registry | Years of registry use | Population | Contains |

|---|---|---|---|

| The National Patient Register [39] | 1994–2012 | All somatic hospital-treated in/outpatients. Primary, secondary and additional diagnosis for patients aged 16 years or above | ICD-10 diagnosis codes for all public and private hospital-treated patients for every contact and treatment for the entire population as well as a civil registration number. Furthermore, data from all hospital treatments/procedures/operations for all hospital-treated patients as well as a civil registration number |

| The Danish Psychiatric Central Research Register [40] | 1995–2012 | All psychiatric hospital-treated in/outpatients. Primary, secondary and additional diagnosis for patients aged 16 years or above | ICD-10 diagnosis codes for all public hospital-treated patients for every contact and treatment for the entire population as well as a civil registration number. No private psychiatric hospital exists |

| The National Health Service Register [41] | 2000–2012 | All patients in primary care aged 16 years or above | All GP services for whole population and every consultation based on civil registration number. The register does not contain information on diagnosis, but many services are disease-specific and can thus be used for identifying chronic conditions |

| The Danish National Prescription Registry [42] | 1995–2012 | All patients in primary care with a prescription who are aged 16 years or above | All Danish medicine prescriptions sold for the entire population using 6-digit ATC codes as well as a civil registration number |

| The Danish Civil Registration System [43] | 2013 | Whole population aged 16 years or above resident in Denmark on 1 January 2014 | Data regarding birth date, age, gender, etc. for the entire population as well as a civil registration number |

ATC Anatomical Therapeutic Chemical Classification System, GP general practitioner, ICD-10 International Statistical Classification of Diseases, 10th Revision

The Definition of a ‘Chronic Condition’, Clinical Ratification and Review

A thorough description of the distinct phases and methods used are provided elsewhere [44–46]. In short, a ‘chronic condition’ was defined in line with previous studies, i.e. the ‘condition had lasted or was expected to last twelve or more months and resulted in functional limitations and/or the need for functional limitations and/or the need for ongoing medical care’ [47–49]. An expert panel consisting of professors, medical specialists and other experts from Aalborg University, the Clinical Institute of Aalborg University at Aalborg University Hospital, the Department of Clinical Epidemiology at Aarhus University Hospital, and others was consulted using the Delphi method in order to identify which of the approximately 22,000 ICD-10 codes and conditions could be considered ‘chronic’ based on the definition [44]. The ICD-10 codes were aggregated to 199 conditions, yet several conditions included subgroups of ICD-10 codes; thus, some consequently contained multiple conditions within the same disease area. Subsequently, all ICD-10 conditions considered chronic by definition were included in the study in pursuit of comprising the full-population burden of chronic conditions. Consequently, the 199 conditions consisted of several ICD-10 codes and thus groups of illnesses.

Data Collection: The Basis of the Data Algorithms

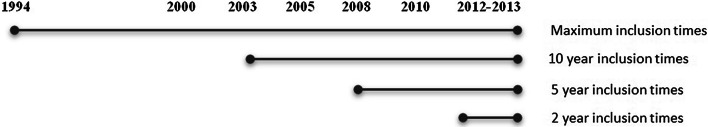

Since many chronic conditions last longer than the defined 12 months, but do not last for a lifetime, the varying ‘chronicity’ of conditions was divided into four groups of severity [44]:

Category I: stationary to progressive chronic conditions (no time limit equals inclusion time going back from the time of interest for as long as valid data were available. In the current study, this starting point was defined by the introduction of the ICD-10 diagnosis coding in Denmark, in 1994).

Category II: stationary to diminishing chronic conditions (10 years from register inclusion time to the time of interest).

Category III: diminishing chronic conditions (5 years from register inclusion time to the time of interest).

Category IV: borderline chronic conditions (2 years from register inclusion time to the time of interest).

The above four categories were designed to include the different chronic conditions when registers covered several years and still have the best possible clinical certainty that the conditions were still existing at the fixed time point of 1 January 2013. All 199 chronic conditions were divided into one of the four categories by medical specialists and experts. An algorithm was created for data collection based on the four categories, as seen in Fig. 1 for all 199 conditions and coherent ICD-10 codes. However, 35 of the 199 chronic conditions were not considered by experts to be properly representative using solely NPR diagnosis data. Thus, they created more complex algorithms using several registers besides diagnosis data, ranging from medicine and hospital treatments to GP services. For example, medicine and coherent indication codes were used to identify people with depression without a hospital diagnosis, and only when the indication codes identified the medicine used for depression, and not others such as pain treatment, etc. The same applied to GP services indicating, for example, diabetes or chronic obstructive lung disease (COPD) treatment, etc., where no hospital diagnosis was found. The details of all 199 unique definitions, their categorisation into one of the four categories and algorithms for replication can be found elsewhere [44, 45].

Fig. 1.

The four categories of chronicity and the inclusion time periods

Statistical Analysis

Prevalence estimates were calculated in both per cent and per 1000 subjects; the proportion was calculated as the number of conditions identified divided by the total number of residents aged 16 years or above alive on 1 January 2013 (n =4,555,439) multiplied by either 100 or 1000. Thus, prevalence was calculated from a specific point in time, based on the above inclusion time periods back in time for each condition. See Fig. 1 or further details in the literature [44].

The prevalence proportions for all conditions were stratified and presented by age and sex for use by, for example, local authorities, health planners and national researchers.

Direct standardisation of age, gender and education based on the national average (i.e. using Denmark as the standard/reference population for age, gender and education) [50] was applied to illustrate differences free of basic socio-economic effects (presented in brackets in Tables 2 and 3 and the electronic supplementary material). The gender and age (10-year intervals) variables were obtained from the Danish Civil Registration System [43], and the educational variables were obtained from the Population Education Register using Danish Education Nomenclature (DUN) classification [51].

Finally, tables were stratified geographically in the five national regions, and the mean age and standard deviation (SD) for each condition were calculated, but due to size and relevance for the international reader, geographical regions, mean age and SDs are presented in the electronic supplementary material.

All data management and data analysis were performed in SAS 9.4 (from Statistics Denmark’s research servers).

Results

The Prevalence Rates

The population’s full burden of chronic disease, with all the chronic conditions summarised, was 65.6% (see Table 2 or Table 3). The ten most prevalent conditions were hypertension (23.3%), respiratory allergy (18.5%), disorders of lipoprotein metabolism (14.3%), depression (10.0%), bronchitis (9.2%), asthma (7.9%), type 2 diabetes (5.3%), COPD (4.7%), osteoarthritis of the knee (3.9%) and osteoporosis (3.5%)/ulcer (3.5%); see the overview of conditions solely by overall disease groups in Table 2 and all 199 conditions in Table 3.

Table 2.

Overview of disease prevalence in Denmark: number of patients, prevalence rate (per 1000), age and gender (per cent within gender) of disease groups of conditions and chosen medicine for Denmark at 1 January 2013

| Name of condition | ICD-10 code/definition | Number and prevalence | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Denmark | Men | Age 16–44 (per 1000) | Age 45–74 (per 1000) | Age 75 + (per 1000) | ||||

| N | Per 1000 (standardised) | Per cent | ||||||

| B—Viral hepatitis and human immunodeficiency virus (HIV) disease | B18, B20–B24 | 8813 | 1.9 | (2.0) | 65.3 | 1.8 | 2.4 | 0.3 |

| C—Malignant neoplasms | C00–C99; D32–D33; D35.2–D35.4; D42–D44 | 229,331 | 50.3 | (50.4) | 43.3 | 10.2 | 69.4 | 155.8 |

| D—In situ and benign neoplasms, and neoplasms of uncertain or unknown behaviour and diseases of the blood and blood-forming organs and certain disorders involving the immune mechanism | D00–D09; D55–D59; D60–D67; D80–D89 | 116,560 | 25.6 | (25.7) | 36.3 | 13.2 | 27.3 | 80.1 |

| E—Endocrine, nutritional and metabolic diseases | E00–E14; E20–E29; E31–35; E70–E78; E84–E85; E88–E89 | 877,433 | 192.6 | (192.7) | 45.6 | 43.5 | 279.6 | 501.4 |

| G—Diseases of the nervous system | G00–G14; G20–G32; G35–G37; G40–47; G50–64; G70–73; G80–G83; G90–G99 | 561,054 | 123.2 | (123.5) | 40.1 | 70.6 | 162.2 | 188.6 |

| H—Diseases of the eye and adnexa and diseases of the ear and mastoid process | H02–H06; H17–H18; H25–H28; H31–H32; H34–H36; H40–55; H57; H80, H810; H93, H90–H93 | 448,176 | 98.4 | (98.6) | 47.5 | 25.6 | 112.6 | 394.4 |

| I—Diseases of the circulatory system | I05–I06; I10–28; I30–33; I36–141; I44–I52; I60–I88; I90–I94; I96–I99 | 1,254,427 | 275.4 | (275.5) | 45.3 | 73.3 | 381.5 | 753.9 |

| J—Diseases of the respiratory system | J30.1; J40–J47; J60–J84; J95, J97–J99 | 1,210,598 | 265.7 | (266.3) | 42.1 | 209.3 | 298.8 | 381.9 |

| K—Diseases of the digestive system | K25–K27; K40, K43, K50–52; K58–K59; K71–K77; K86–K87 | 329,337 | 72.3 | (72.6) | 44.7 | 41.3 | 86.3 | 157.4 |

| L—Diseases of the skin and subcutaneous tissue | L40 | 65,469 | 14.4 | (14.5) | 47.8 | 7.9 | 19.3 | 21.7 |

| M—Diseases of the musculoskeletal system and connective tissue | M01–M25; M30–M36; M40–M54; M60.1–M99 | 1,032,808 | 226.7 | (227.1) | 42.2 | 113.2 | 291.2 | 470.5 |

| N—Diseases of the genitourinary system | N18 | 20,162 | 4.4 | (4.5) | 59.4 | 1.0 | 4.8 | 20.0 |

| Q—Congenital malformations, deformations and chromosomal abnormalities | Q00–Q56; Q60–Q99 | 124,898 | 27.4 | (27.5) | 41.7 | 33.9 | 23.2 | 16.2 |

| F—Mental and behavioural disorders | F00–99 | 683,194 | 150.0 | (150.7) | 41.0 | 135.2 | 150.2 | 223.7 |

| Having one or more chronic condition | 2,989,441 | 656.2 | (657.2) | 45.5 | 480.5 | 771.5 | 953.9 | |

| Mean number of chronic conditions (std. dev) | 2.2 (2.8) | – | – | 2.0 (2.6) | 1.1 (1.6) | 2.7 (2.8) | 5.3 (3.6) | |

| Depression medicinec,** | ATC: N06A | 529,918 | 116.3 | (116.7) | 36.3 | 88.7 | 126.9 | 201.9 |

| Antipsychotic medicinec,** | ATC: N05A | 138,625 | 30.4 | (30.6) | 45.7 | 26.1 | 31.9 | 44.8 |

| Indication prescribed anxiety medicinec,** | All prescriptions with either indication code 163 (for anxiety) or 371 (for anxiety, addictive) | 102,568 | 22.5 | (22.6) | 34.5 | 19.9 | 23.7 | 30.1 |

| Heart failure medicationc,** | ATC: C01AA05, C03, C07 or C09A with indication code 430 (for heart failure) | 7468 | 1.6 | (1.7) | 64.6 | 0.1 | 2.0 | 7.5 |

| Ischaemic heart medicationc,** | ATC: C01A, C01B, C01D, C01E | 129,484 | 28.4 | (28.5) | 51.8 | 1.4 | 32.0 | 147.3 |

| All of the five types of medicine above | 688,006 | 151.0 | (151.6) | 40.4 | 100.2 | 166.1 | 331.1 | |

Standardised rates or standard devitions in brackets

See table with 10-year age intervals in Supplementary Material 2 in the electronic supplementary matertial

Conditions marked ‘A’ overlap with other conditions and are thus not counted twice [44]

ATC Anatomical Therapeutic Chemical Classification System, ICD-10 International Statistical Classification of Diseases, 10th Revision

cComplex defined conditions; see reference for further details [44]

**Two-year prevalence

Table 3.

Disease prevalence of 199 chronic conditions: number of patients treated, prevalence rate (per 1000), age and gender (per cent within gender) of all conditions and chosen medicine for Denmark at 1 January 2013

| No. | Name of condition | ICD-10 code/definition | Number and prevalence | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Denmark | Men | Age 16–44 (per 1000) | Age 45–74 (per 1000) | Age 75+ (per 1000) | |||||

| N | Per 1000 (standardised) | Per cent | |||||||

| B—Viral hepatitis and human immunodeficiency virus [HIV] disease | B18, B20–B24 | 8813 | 1.9 | (2.0) | 65.3 | 1.8 | 2.4 | 0.3 | |

| 1 | Chronic viral hepatitis | B18 | 4584 | 1.0 | (1.0) | 60.1 | 1.0 | 1.2 | 0.1 |

| 2 | Human immunodeficiency virus [HIV] disease | B20–24 | 4229 | 0.9 | (0.9) | 71.0 | 0.8 | 1.2 | 0.1 |

| C—Malignant neoplasms | C00–C99; D32–D33; D35.2–D35.4; D42–D44 | 229,331 | 50.3 | (50.4) | 43.3 | 10.2 | 69.4 | 155.8 | |

| 3 | Malignant neoplasms of other and unspecified localizations | C00–C14; C30–C33; C37–C42; C45–C49; C69; C73–74; C754–C759 | 20,557 | 4.5 | (4.6) | 53.5 | 1.3 | 6.6 | 10.1 |

| 4 | Malignant neoplasms of digestive organs | C15–C17; C22–C26 | 4839 | 1.1 | (1.1) | 59.5 | 0.1 | 1.6 | 3.4 |

| 5 | Malignant neoplasm of colon | C18 | 18,826 | 4.1 | (4.1) | 47.0 | 0.2 | 4.9 | 20.3 |

| 6 | Malignant neoplasms of rectosigmoid junction, rectum, anus and anal canal | C19–C21 | 10,680 | 2.3 | (2.3) | 55.4 | 0.1 | 3.2 | 9.5 |

| 7 | Malignant neoplasm of bronchus and lung | C34 | 14,762 | 3.2 | (3.3) | 49.4 | 0.2 | 4.8 | 10.6 |

| 8 | Malignant melanoma of skin | C43 | 19,636 | 4.3 | (4.3) | 42.6 | 2.0 | 5.7 | 9.0 |

| 9 | Other malignant neoplasms of skin | C44 | 15,597 | 3.4 | (3.4) | 51.2 | 0.3 | 3.9 | 16.7 |

| 10 | Malignant neoplasm of breast | C50 | 50,687 | 11.1 | (11.1) | 0.7 | 1.0 | 17.6 | 29.5 |

| 11 | Malignant neoplasms of female genital organs | C51–C52; C56–C58 | 7245 | 1.6 | (1.6) | – | 0.3 | 2.4 | 3.9 |

| 12 | Malignant neoplasm of cervix uteri, corpus uteri and part unspecified | C53–C55 | 11,608 | 2.5 | (2.5) | 0.0 | 0.7 | 3.5 | 7.1 |

| 13 | Malignant tumour of male genitalia | C60, C62–C63 | 5194 | 1.1 | (1.1) | 99.9 | 1.2 | 1.2 | 0.7 |

| 14 | Malignant neoplasm of prostate | C61 | 26,697 | 5.9 | (5.9) | 100.0 | 0.0 | 7.5 | 27.0 |

| 15 | Malignant neoplasms of urinary tract | C64–C68 | 10,319 | 2.3 | (2.3) | 71.2 | 0.1 | 2.9 | 9.9 |

| 16 | Brain cancerc | C71, C75.1–C75.3, D33.0–D33.2, D35.2–D35.4, D43.0–D43.2, D44.3–D44.5 (brain). C70, D32, D42 (brain membrane). C72, D33.3–D33.9, D43.3–D43.9 (cranial nerve, spinal cord) | 15,310 | 3.4 | (3.4) | 52.9 | 1.4 | 4.7 | 6.2 |

| 17 | Malignant neoplasms of ill-defined, secondary and unspecified sites, and of independent (primary) multiple sites | C76–C80, C97 | 25,619 | 5.6 | (5.6) | 43.0 | 1.2 | 8.4 | 14.0 |

| 18 | Malignant neoplasms, stated or presumed to be primary, of lymphoid, haematopoietic and related tissue | C81–C96 | 19,712 | 4.3 | (4.3) | 54.4 | 1.5 | 5.6 | 12.4 |

| D—In situ and benign neoplasms, and neoplasms of uncertain or unknown behaviour and diseases of the blood and blood-forming organs and certain disorders involving the immune mechanism | D00–D09; D55–D59; D60–D67; D80–D89 | 116,560 | 25.6 | (25.7) | 36.3 | 13.2 | 27.3 | 80.1 | |

| 19 | In situ neoplasms | D00–D09 | 19,810 | 4.3 | (4.4) | 20.0 | 2.5 | 5.5 | 7.9 |

| 20 | Haemolytic anaemias | D55–D59 | 3055 | 0.7 | (0.7) | 33.7 | 0.7 | 0.6 | 1.2 |

| 21 | Aplastic and other anaemias | D60–D63 | 14,918 | 3.3 | (3.3) | 40.2 | 0.9 | 3.3 | 15.0 |

| 22 | Other anaemias | D64 | 46,613 | 10.2 | (10.3) | 38.7 | 2.3 | 9.7 | 53.1 |

| 23 | Coagulation defects, purpura and other haemorrhagic conditions | D65–D69 | 25,376 | 5.6 | (5.6) | 37.4 | 5.2 | 5.7 | 7.1 |

| 24 | Other diseases of blood and blood-forming organs | D70–D77 | 8896 | 2.0 | (2.0) | 43.5 | 1.0 | 2.6 | 3.6 |

| 25 | Certain disorders involving the immune mechanism | D80–D89 | 7660 | 1.7 | (1.7) | 50.8 | 1.4 | 2.0 | 1.3 |

| E—Endocrine, nutritional and metabolic diseases | E00–E14; E20–E29; E31–35; E70–E78; E84–E85; E88–E89 | 877,433 | 192.6 | (192.7) | 45.6 | 43.5 | 279.6 | 501.4 | |

| 26 | Diseases of the thyroidc | E00–E04, E06, E07 | 131,908 | 29.0 | (29.0) | 15.9 | 11.3 | 39.1 | 66.2 |

| 27 | Thyrotoxicosisc | E05 | 41,374 | 9.1 | (9.0) | 18.3 | 3.8 | 10.8 | 26.7 |

| 28 | Diabetes type 1c | E10 | 23,062 | 5.1 | (5.1) | 57.9 | 4.9 | 5.6 | 3.5 |

| 29 | Diabetes type 2c | E11 | 242,177 | 53.2 | (53.3) | 53.0 | 8.5 | 77.9 | 152.1 |

| 30 | Diabetes othersc | E12–E14 | 1117 | 0.2 | (0.2) | 48.6 | 0.2 | 0.3 | 0.5 |

| 31 | Disorders of other endocrine glands | E20–E35, except E30 | 28,650 | 6.3 | (6.4) | 28.6 | 6.5 | 5.6 | 8.9 |

| 32 | Metabolic disorders | E70–E77; E79–E83; E85, E88–E89; | 23,690 | 5.2 | (5.2) | 36.6 | 3.7 | 6.1 | 8.2 |

| 33 | Disturbances in lipoprotein circulation and other lipidsc | E78 | 652,242 | 143.2 | (143.1) | 51.1 | 11.8 | 221.2 | 408.1 |

| 34 | Cystic fibrosisc | E84 | 947 | 0.2 | (0.2) | 41.9 | 0.3 | 0.1 | 0.1 |

| G—Diseases of the nervous system | G00–G14; G20–G32; G35–G37; G40–47; G50–64; G70–73; G80–G83; G90–G99 | 561,054 | 123.2 | (123.5) | 40.1 | 70.6 | 162.2 | 188.6 | |

| 35 | Inflammatory diseases of the central nervous system | G00–G09 | 7642 | 1.7 | (1.7) | 50.1 | 1.3 | 2.0 | 2.2 |

| 36 | Systemic atrophies primarily affecting the central nervous system and other degenerative diseases | G10–G14, G30–G32 | 10,401 | 2.3 | (2.3) | 46.8 | 0.4 | 2.2 | 12.1 |

| 37 | Parkinson’s diseasec | G20, G21, G22, F02.3 | 57,583 | 12.6 | (12.6) | 43.7 | 4.1 | 16.3 | 37.3 |

| 38 | Extrapyramidal and movement disorders | G23–G26 | 10,837 | 2.4 | (2.4) | 41.8 | 1.1 | 2.9 | 6.4 |

| 39 | Sclerosis | G35 | 13,284 | 2.9 | (2.9) | 30.6 | 1.9 | 4.2 | 1.5 |

| 40 | Demyelinating diseases of the central nervous system | G36–G37 | 4571 | 1.0 | (1.0) | 34.7 | 0.9 | 1.3 | 0.4 |

| 41 | Epilepsyc | G40–G41 | 61,695 | 13.5 | (13.6) | 48.2 | 9.7 | 16.0 | 20.3 |

| 42 | Migrainec | G43 | 149,866 | 32.9 | (33.0) | 18.6 | 24.9 | 44.1 | 15.6 |

| 43 | Other headache syndromes | G44 | 16,469 | 3.6 | (3.6) | 35.9 | 4.0 | 3.6 | 1.8 |

| 44 | Transient cerebral ischaemic attacks and related syndromes and vascular syndromes of brain in cerebrovascular diseases | G45–G46 | 43,977 | 9.7 | (9.7) | 53.5 | 1.1 | 12.7 | 37.6 |

| 45 | Sleep disorders | G47 | 36,806 | 8.1 | (8.1) | 73.5 | 4.1 | 12.6 | 5.0 |

| 46 | Disorders of trigeminal nerve and facial nerve disorders | G50–G51 | 21,488 | 4.7 | (4.7) | 43.0 | 2.8 | 6.0 | 7.4 |

| 47 | Disorders of other cranial nerves, cranial nerve disorders in diseases classified elsewhere, nerve root and plexus disorders and nerve root and plexus compressions in diseases classified elsewhere | G52–G55 | 12,429 | 2.7 | (2.7) | 48.9 | 1.3 | 4.0 | 3.6 |

| 48 | Mononeuropathies of upper limb | G56 | 122,395 | 26.9 | (26.9) | 37.2 | 12.6 | 39.1 | 36.5 |

| 49 | Mononeuropathies of lower limb, other mononeuropathies and mononeuropathy in diseases classified elsewhere | G57–G59 | 18,627 | 4.1 | (4.1) | 43.8 | 1.9 | 6.1 | 5.0 |

| 50 | Polyneuropathies and other disorders of the peripheral nervous system | G60–G64 | 30,289 | 6.6 | (6.7) | 56.4 | 1.7 | 9.3 | 18.2 |

| 51 | Diseases of myoneural junction and muscle | G70–G73 | 5758 | 1.3 | (1.3) | 47.7 | 0.9 | 1.5 | 1.6 |

| 52 | Cerebral palsy and other paralytic syndromes | G80–G83 | 14,410 | 3.2 | (3.2) | 53.9 | 2.9 | 3.5 | 3.2 |

| 53 | Other disorders of the nervous system | G90–G99 | 44,394 | 9.7 | (9.8) | 46.4 | 5.9 | 12.1 | 17.0 |

| H—Diseases of the eye and adnexa and diseases of the ear and mastoid process | H02–H06; H17–H18; H25–H28; H31–H32; H34–H36; H40–55; H57; H80, H810; H93, H90–H93 | 448,176 | 98.4 | (98.6) | 47.5 | 25.6 | 112.6 | 394.4 | |

| 54 | Disorders of eyelid, lacrimal system and orbit | H02–H06 | 13,191 | 2.9 | (2.9) | 37.3 | 0.9 | 4.0 | 7.5 |

| 55 | Corneal scars and opacities | H17 | 2173 | 0.5 | (0.5) | 58.1 | 0.2 | 0.5 | 1.3 |

| 56 | Other disorders of cornea | H18 | 9473 | 2.1 | (2.1) | 43.5 | 1.0 | 2.1 | 7.4 |

| 57 | Diseases of the eye lens (cataracts) | H25–H28 | 68,009 | 14.9 | (15.1) | 40.5 | 0.5 | 15.6 | 84.8 |

| 58 | Disorders of the choroid and retina | H31–H32 | 1900 | 0.4 | (0.4) | 48.3 | 0.2 | 0.5 | 1.1 |

| 59 | Retinal vascular occlusions | H34 | 10,358 | 2.3 | (2.3) | 50.8 | 0.2 | 2.6 | 11.4 |

| 60 | Other retinal disorders | H35 | 68,485 | 15.0 | (15.1) | 40.2 | 1.6 | 13.0 | 93.7 |

| 61 | Retinal disorders in diseases classified elsewhere | H36 | 19,279 | 4.2 | (4.3) | 58.7 | 1.7 | 6.1 | 7.4 |

| 62 | Glaucomac | H40–H42 | 67,310 | 14.8 | (14.9) | 43.5 | 1.2 | 16.2 | 76.4 |

| 63 | Disorders of the vitreous body and globe | H43–H45 | 7572 | 1.7 | (1.7) | 44.6 | 0.7 | 2.4 | 3.1 |

| 64 | Disorders of optic nerve and visual pathways | H46–H48 | 6184 | 1.4 | (1.4) | 39.0 | 1.2 | 1.6 | 1.4 |

| 65 | Disorders of ocular muscles, binocular movement, accommodation and refraction | H49–H52 | 18,247 | 4.0 | (4.0) | 45.4 | 4.3 | 3.9 | 2.8 |

| 66 | Visual disturbances | H53 | 22,232 | 4.9 | (4.9) | 45.7 | 2.6 | 5.9 | 11.1 |

| 67 | Blindness and partial sight | H54 | 6614 | 1.5 | (1.5) | 44.4 | 0.6 | 1.5 | 5.6 |

| 68 | Nystagmus and other irregular eye movements and other disorders of eye and adnexa | H55, H57 | 11,133 | 2.4 | (2.5) | 40.3 | 1.7 | 3.0 | 3.7 |

| 69 | Otosclerosis | H80 | 10,360 | 2.3 | (2.3) | 35.7 | 0.8 | 3.1 | 5.4 |

| 70 | Ménière’s diseasec | H810 | 10,003 | 2.2 | (2.2) | 43.0 | 0.4 | 3.0 | 7.3 |

| 71 | Other diseases of the inner ear | H83 | 29,865 | 6.6 | (6.3) | 91.8 | 0.6 | 9.0 | 24.5 |

| 72 | Conductive and sensorineural hearing loss | H90 | 43,238 | 9.5 | (9.6) | 48.7 | 3.7 | 11.3 | 29.5 |

| 73 | Other hearing loss and other disorders of ear, not elsewhere classified | H910, H912, H913, H918, H930, H932, H933 | 8306 | 1.8 | (1.8) | 53.0 | 0.7 | 2.3 | 5.2 |

| 74 | Presbycusis (age-related hearing loss) | H911 | 80,659 | 17.7 | (17.6) | 48.9 | 0.4 | 9.6 | 147.4 |

| 75 | Hearing loss, unspecified | H919 | 87,806 | 19.3 | (19.3) | 55.3 | 3.0 | 24.5 | 74.5 |

| 76 | Tinnitus | H931 | 40,124 | 8.8 | (8.7) | 58.4 | 2.5 | 13.4 | 17.5 |

| 77 | Other specified disorders of ear | H938 | 20,537 | 4.5 | (4.4) | 48.1 | 0.8 | 5.9 | 16.1 |

| I—Diseases of the circulatory system | I05–I06; I10–28; I30–33;I36–141; I44–I52; I60–I88; I90–I94; I96–I99 | 1,254,427 | 275.4 | (275.5) | 45.3 | 73.3 | 381.5 | 753.9 | |

| 78 | Aortic and mitral valve diseasec | I05, I06, I34, I35 | 30,123 | 6.6 | (6.6) | 50.9 | 0.7 | 6.4 | 37.7 |

| 79 | Hypertensive diseasesc | I10–I15 | 1,060,046 | 232.7 | (232.7) | 44.6 | 41.8 | 330.8 | 695.8 |

| 80 | Heart failurec | I11.0, I13.0, I13.2, I42.0, I42.6, I42.7, I42.9, I50.0, I50.1, I50.9 | 37,540 | 8.2 | (8.3) | 63.5 | 0.7 | 9.5 | 40.3 |

| 80A | Ischaemic heart diseases | I20–I25 | 139,173 | 30.6 | (30.7) | 60.2 | 2.6 | 41.8 | 114.5 |

| 81 | Angina pectoris | I20 | 78,476 | 17.2 | (17.3) | 58.4 | 1.6 | 25.7 | 53.0 |

| 82 |

Acute myocardial infarction and subsequent myocardial infarction |

I21–I22 | 36,654 | 8.0 | (8.1) | 66.6 | 0.7 | 11.1 | 29.8 |

| 83 | AMI complex/other | I23–I24 | 2969 | 0.7 | (0.7) | 61.3 | 0.1 | 0.9 | 2.3 |

| 84 | Chronic ischaemic heart disease | I25 | 84,592 | 18.6 | (18.6) | 64.7 | 0.8 | 23.8 | 81.4 |

| 85 | Pulmonary heart disease and diseases of pulmonary circulation | I26–I28 | 15,352 | 3.4 | (3.4) | 44.8 | 1.0 | 3.8 | 13.0 |

| 86 | Acute pericarditis | I30 | 5563 | 1.2 | (1.2) | 73.1 | 1.0 | 1.4 | 1.3 |

| 87 | Other forms of heart disease | I31–I43, except I34–I35 and I42 | 8,119 | 1.8 | (1.8) | 60.5 | 0.7 | 2.1 | 5.4 |

| 88 | Atrioventricular and left bundle branch block | I44 | 14,604 | 3.2 | (3.2) | 58.7 | 0.4 | 2.7 | 20.0 |

| 89 | Other conduction disorders | I45–46 | 11,823 | 2.6 | (2.6) | 59.6 | 1.0 | 2.8 | 9.5 |

| 90 | Paroxysmal tachycardia | I47 | 39,510 | 8.7 | (8.7) | 48.1 | 3.3 | 11.0 | 23.9 |

| 91 | Atrial fibrillation and flutter | I48 | 112,342 | 24.7 | (24.7) | 57.2 | 1.7 | 26.5 | 132.0 |

| 92 | Other cardiac arrhythmias | I49 | 34,418 | 7.6 | (7.6) | 47.9 | 2.2 | 8.7 | 28.8 |

| 93 | Complications and ill-defined descriptions of heart disease and other heart disorders in diseases classified elsewhere | I51–52 | 7337 | 1.6 | (1.6) | 50.3 | 0.6 | 1.8 | 5.7 |

| 94 | Stroke | I60, I61,I63–I64, Z501 (rehabilitation) | 72,606 | 15.9 | (16.0) | 54.2 | 1.6 | 19.8 | 68.7 |

| 95 | Cerebrovascular diseases | I62, I65–I68 | 17,308 | 3.8 | (3.8) | 51.1 | 0.8 | 4.9 | 13.3 |

| 96 | Sequelae of cerebrovascular disease | I69 | 50,952 | 11.2 | (11.2) | 52.5 | 0.8 | 12.7 | 55.9 |

| 97 | Atherosclerosis | I70 | 32,064 | 7.0 | (7.0) | 53.6 | 0.4 | 8.3 | 34.2 |

| 98 | Aortic aneurysm and aortic dissection | I71 | 10,296 | 2.3 | (2.3) | 72.2 | 0.1 | 2.6 | 11.2 |

| 99 | Diseases of arteries, arterioles and capillaries | I72, I74, I77–I79 | 11,830 | 2.6 | (2.6) | 45.6 | 1.0 | 3.4 | 6.2 |

| 100 | Other peripheral vascular diseases | I73 | 28,508 | 6.3 | (6.3) | 54.8 | 0.7 | 8.3 | 24.4 |

| 101 | Phlebitis, thrombosis of the portal vein and others | I80–I82 | 37,388 | 8.2 | (8.3) | 45.5 | 3.5 | 10.2 | 22.2 |

| 102 | Varicose veins of lower extremities | I83 | 23,530 | 5.2 | (5.2) | 30.6 | 3.2 | 6.8 | 6.6 |

| 103 | Haemorrhoidsc | I84 | 74,285 | 16.3 | (16.3) | 40.1 | 14.5 | 17.5 | 19.0 |

| 104 | Oesophageal varices (chronic), varicose veins of other sites, other disorders of veins, non-specific lymphadenitis, other non-infective disorders of lymphatic vessels and lymph nodes and other and unspecified disorders of the circulatory system | I85–I99, except I89 and I95 | 15,194 | 3.3 | (3.3) | 52.6 | 2.2 | 3.9 | 6.1 |

| J—Diseases of the respiratory system | J30.1; J40–J47; J60–J84; J95, J97–J99 | 1,210,598 | 265.7 | (266.3) | 42.1 | 209.3 | 298.8 | 381.9 | |

| 105 | Respiratory allergyc | J30, except J30.0 | 841,685 | 184.8 | (185.2) | 41.0 | 154.0 | 204.3 | 240.3 |

| 105A | Chronic lower respiratory diseasesc | J40–J43, J47 | 418,120 | 91.8 | (92.0) | 39.8 | 57.8 | 112.8 | 156.3 |

| 106 |

Bronchitis, not specified as acute or chronic, simple and mucopurulent chronic bronchitis and unspecified chronic bronchitis |

J40–J42 | 12,790 | 2.8 | (2.8) | 43.6 | 0.4 | 3.5 | 11.3 |

| 107 | Emphysema | J43 | 5557 | 1.2 | (1.2) | 51.1 | 0.2 | 1.7 | 3.7 |

| 108 | Chronic obstructive lung disease (COPD)c | J44, J96, J13–J18 | 216,184 | 47.5 | (47.6) | 45.0 | 17.6 | 60.6 | 131.4 |

| 109 | Asthma, status asthmaticusc | J45–J46 | 361,129 | 79.3 | (79.4) | 42.1 | 64.2 | 86.5 | 118.4 |

| 110 | Bronchiectasis | J47 | 4362 | 1.0 | (1.0) | 35.0 | 0.3 | 1.4 | 2.2 |

| 111 | Other diseases of the respiratory system | J60–J84; J95, J97–J99 | 21,993 | 4.8 | (4.9) | 52.5 | 1.5 | 6.2 | 14.6 |

| K—Diseases of the digestive system | K25–K27; K40, K43, K50–52; K58–K59; K71–K77; K86–K87 | 329,337 | 72.3 | (72.6) | 44.7 | 41.3 | 86.3 | 157.4 | |

| 112 | Ulcersc | K25–K27 | 157,379 | 34.5 | (34.8) | 43.2 | 15.3 | 42.4 | 91.9 |

| 113 | Inguinal hernia | K40 | 25,032 | 5.5 | (5.5) | 88.7 | 2.1 | 7.7 | 11.5 |

| 114 | Ventral hernia | K43 | 7941 | 1.7 | (1.7) | 44.7 | 0.7 | 2.5 | 3.3 |

| 115 | Crohn’s diease | K50 | 18,913 | 4.2 | (4.2) | 41.4 | 4.4 | 4.1 | 3.4 |

| 116 | Ulcerative colitis | K51 | 29,538 | 6.5 | (6.5) | 45.2 | 5.4 | 7.2 | 8.2 |

| 117 | Other non-infective gastroenteritis and colitis | K52 | 20,844 | 4.6 | (4.6) | 35.5 | 2.6 | 5.0 | 12.8 |

| 118 | Irritable bowel syndrome (IBS) | K58 | 37,593 | 8.3 | (8.3) | 29.9 | 7.5 | 9.0 | 8.4 |

| 119 | Other functional intestinal disorders | K59 | 51,933 | 11.4 | (11.5) | 37.0 | 6.5 | 11.8 | 34.1 |

| 120 | Diseases of liver, biliary tract and pancreas | K71–K77; K86–K87 | 26,956 | 5.9 | (6.0) | 48.6 | 2.4 | 8.8 | 8.5 |

| L—Diseases of the skin and subcutaneous tissue | L40 | 65,469 | 14.4 | (14.5) | 47.8 | 7.9 | 19.3 | 21.7 | |

| 121 | Psoriasisc | L40 | 65,469 | 14.4 | (14.5) | 47.8 | 7.9 | 19.3 | 21.7 |

| M—Diseases of the musculoskeletal system and connective tissue | M01–M25; M30–M36; M40–M54; M60.1–M99 | 1,032,808 | 226.7 | (227.1) | 42.2 | 113.2 | 291.2 | 470.5 | |

| 122 | Infectious arthropathies | M01–M03 | 9402 | 2.1 | (2.1) | 49.7 | 1.8 | 2.3 | 2.1 |

| 122A | Inflammatory polyarthropathies and ankylosing spondylitisc | M05–M14, M45 | 165,944 | 36.4 | (36.5) | 51.7 | 12.7 | 50.4 | 84.9 |

| 123 | Rheumatoid arthritisc | M05, M06, M07.1, M07.2, M07.3, M08, M09 | 77,345 | 17.0 | (17.0) | 34.2 | 8.1 | 23.1 | 30.5 |

| 124 |

Inflammatory polyarthropathies – except rheumatoid arthritisc |

M074–M079, M10–M14, M45 | 115,945 | 25.5 | (25.5) | 58.3 | 7.9 | 35.4 | 63.3 |

| 125 | Polyarthrosis [arthrosis] | M15 | 16,935 | 3.7 | (3.7) | 20.8 | 0.2 | 5.4 | 12.6 |

| 126 | Coxarthrosis [arthrosis of hip] | M16 | 104,115 | 22.9 | (22.7) | 43.3 | 2.0 | 26.8 | 108.1 |

| 127 | Gonarthrosis [arthrosis of knee] | M17 | 178,811 | 39.3 | (39.4) | 44.2 | 5.0 | 58.6 | 113.5 |

| 128 | Arthrosis of first carpometacarpal joint and other arthrosis | M18–M19 | 91,101 | 20.0 | (20.1) | 41.7 | 4.2 | 31.0 | 43.4 |

| 129 | Acquired deformities of fingers and toes | M20 | 55,730 | 12.2 | (12.3) | 21.3 | 5.5 | 17.9 | 17.1 |

| 130 | Other acquired deformities of limbs | M21 | 20,584 | 4.5 | (4.5) | 34.9 | 2.7 | 5.8 | 6.9 |

| 131 | Disorders of patella (knee cap) | M22 | 38,999 | 8.6 | (8.6) | 38.0 | 13.7 | 5.0 | 0.6 |

| 132 | Internal derangement of knee | M230, M231, M233, M235, M236, M238 | 9192 | 2.0 | (2.0) | 55.6 | 2.8 | 1.5 | 0.4 |

| 133 | Derangement of meniscus due to old tear or injury | M232 | 36,374 | 8.0 | (8.0) | 53.6 | 6.9 | 10.2 | 2.5 |

| 134 | Internal derangement of knee, unspecified | M239 | 28,206 | 6.2 | (6.2) | 50.0 | 6.9 | 6.3 | 2.3 |

| 135 | Other specific joint derangements | M24, except M240–M241 | 5923 | 1.3 | (1.3) | 57.2 | 1.9 | 0.9 | 0.5 |

| 136 | Other joint disorders, not elsewhere classified | M25 | 12,043 | 2.6 | (2.7) | 34.7 | 2.3 | 3.1 | 1.9 |

| 137 | Systemic connective tissue disorders | M30–M36, except M32,M34 | 42,631 | 9.4 | (9.4) | 24.7 | 4.2 | 10.0 | 32.3 |

| 138 | Systemic lupus erythematosus | M32 | 3376 | 0.7 | (0.7) | 12.9 | 0.5 | 1.0 | 0.7 |

| 139 | Dermatopolymyositis | M33 | 1137 | 0.2 | (0.2) | 39.8 | 0.1 | 0.4 | 0.4 |

| 140 | Systemic sclerosis | M34 | 1675 | 0.4 | (0.4) | 21.0 | 0.1 | 0.6 | 0.5 |

| 141 | Kyphosis, lordosis | M40 | 4160 | 0.9 | (0.9) | 47.7 | 0.7 | 1.1 | 0.7 |

| 142 | Scoliosis | M41 | 17,686 | 3.9 | (3.9) | 31.9 | 5.0 | 2.7 | 4.3 |

| 143 | Spinal osteochondrosis | M42 | 8034 | 1.8 | (1.8) | 63.4 | 1.4 | 2.2 | 1.0 |

| 144 | Other deforming dorsopathies | M43 | 23,756 | 5.2 | (5.3) | 42.4 | 2.2 | 7.3 | 9.9 |

| 145 | Other inflammatory spondylopathies | M46 | 7086 | 1.6 | (1.6) | 45.5 | 1.1 | 1.9 | 2.0 |

| 146 | Spondylosis | M47 | 61,999 | 13.6 | (13.6) | 45.9 | 2.4 | 21.2 | 31.4 |

| 147 | Other spondylopathies and spondylopathies in diseases classified elsewhere | M48, M49 | 50,805 | 11.2 | (11.2) | 44.8 | 1.1 | 14.7 | 43.7 |

| 148 | Cervical disc disorders | M50 | 11,476 | 2.5 | (2.5) | 46.4 | 1.5 | 3.8 | 1.2 |

| 149 | Other intervertebral disc disorders | M51 | 40,161 | 8.8 | (8.9) | 49.4 | 6.4 | 11.4 | 7.6 |

| 150 | Other dorsopathies, not elsewhere classified | M53 | 7246 | 1.6 | (1.6) | 40.9 | 1.4 | 1.9 | 1.2 |

| 151 | Dorsalgia | M54 | 40,780 | 9.0 | (9.0) | 42.9 | 7.3 | 10.0 | 11.9 |

| 152 | Soft tissue disorders | M60–M63, except M60.0 | 13,422 | 2.9 | (3.0) | 28.6 | 3.2 | 2.8 | 2.4 |

| 153 | Synovitis and tenosynovitis | M65 | 19,104 | 4.2 | (4.2) | 37.5 | 3.1 | 5.4 | 3.8 |

| 154 | Disorders of synovium and tendon | M66–68 | 19,669 | 4.3 | (4.3) | 41.7 | 4.7 | 4.3 | 2.1 |

| 155 | Soft tissue disorders related to use, overuse and pressure | M70 | 11,090 | 2.4 | (2.4) | 42.4 | 1.6 | 3.0 | 3.4 |

| 156 | Fibroblastic disorders | M72 | 43,600 | 9.6 | (9.6) | 63.7 | 2.3 | 14.2 | 22.6 |

| 157 | Shoulder lesions | M75 | 58,112 | 12.8 | (12.7) | 50.3 | 7.2 | 19.0 | 8.6 |

| 158 | Enthesopathies of lower limb, excluding foot | M76 | 11,223 | 2.5 | (2.5) | 49.4 | 2.7 | 2.6 | 0.9 |

| 159 | Other enthesopathies | M77 | 10,500 | 2.3 | (2.3) | 40.4 | 1.9 | 2.9 | 1.0 |

| 160 | Rheumatism, unspecified | M790 | 6852 | 1.5 | (1.5) | 13.7 | 0.7 | 2.3 | 1.2 |

| 161 | Myalgia | M791 | 10,168 | 2.2 | (2.2) | 36.8 | 1.4 | 2.9 | 3.0 |

| 162 | Other soft tissue disorders, not elsewhere classified | M792– M794; M798–M799 | 7939 | 1.7 | (1.7) | 36.9 | 1.5 | 2.0 | 1.7 |

| 163 | Other soft tissue disorders, not elsewhere classified: pain in limb | M796 | 22,201 | 4.9 | (4.9) | 41.5 | 3.9 | 5.5 | 6.7 |

| 164 | Fibromyalgia | M797 | 3399 | 0.7 | (0.7) | 4.5 | 0.6 | 1.0 | 0.3 |

| 165 | Osteoporosisc | M80–M81 | 158,813 | 34.9 | (34.8) | 15.3 | 0.7 | 43.5 | 163.6 |

| 166 | Osteoporosis in diseases classified elsewhere | M82 | 1007 | 0.2 | (0.2) | 35.2 | 0.1 | 0.3 | 0.7 |

| 167 | Adult osteomalacia and other disorders of bone density and structure | M83, M85, except M833 | 43,271 | 9.5 | (9.5) | 19.2 | 1.9 | 14.4 | 22.7 |

| 168 | Disorders of continuity of bone | M84 | 1865 | 0.4 | (0.4) | 51.6 | 0.3 | 0.5 | 0.5 |

| 169 | Other osteopathies | M86–M90 | 24,251 | 5.3 | (5.3) | 38.4 | 2.2 | 7.0 | 12.4 |

| 170 | Other disorders of the musculoskeletal system and connective tissue | M95–M99 | 30,038 | 6.6 | (6.6) | 52.1 | 5.4 | 7.4 | 8.2 |

| N—Diseases of the genitourinary system | N18 | 20,162 | 4.4 | (4.5) | 59.4 | 1.0 | 4.8 | 20.0 | |

| 171 | Chronic renal failure (CRF)c | N18 | 20,162 | 4.4 | (4.5) | 59.4 | 1.0 | 4.8 | 20.0 |

| Q—Congenital malformations, deformations and chromosomal abnormalities | Q00–Q56; Q60–Q99 | 124,898 | 27.4 | (27.5) | 41.7 | 33.9 | 23.2 | 16.2 | |

| 172 | Congenital malformations: of the nervous, circulatory and respiratory systems, cleft palate and cleft lip, urinary tract, bones and muscles, other and chromosomal abnormalities not elsewhere classified | Q00–Q07; Q20–Q37; Q60–Q99 | 85,534 | 18.8 | (18.9) | 37.8 | 23.7 | 15.6 | 9.8 |

| 173 | Congenital malformations of eye, ear, face and neck | Q10–Q18 | 19,689 | 4.3 | (4.3) | 38.8 | 6.2 | 3.0 | 1.8 |

| 174 | Other congenital malformations of the digestive system | Q38–Q45 | 6481 | 1.4 | (1.4) | 41.8 | 1.0 | 1.6 | 2.9 |

| 175 | Congenital malformations of the sexual organs | Q50–Q56 | 16,192 | 3.6 | (3.6) | 64.3 | 4.1 | 3.3 | 1.9 |

| F—Mental and behavioural disorders | F00–99 | 683,194 | 150.0 | (150.7) | 41.0 | 135.2 | 150.2 | 223.7 | |

| 176 | Dementiac | F00, G30, F01, F02.0, F03.9, G31.8B, G31.8E, G31.9, G31.0B | 36,803 | 8.1 | (8.1) | 36.3 | 0.0 | 3.7 | 71.7 |

| 177 | Organic, including symptomatic, mental disorders | F04–F09 | 26,430 | 5.8 | (5.9) | 48.8 | 2.5 | 5.8 | 22.6 |

| 178 | Mental and behavioural disorders due to use of alcohol | F10 | 59,143 | 13.0 | (13.2) | 67.0 | 9.4 | 17.5 | 7.9 |

| 179 | Mental and behavioural disorders due to psychoactive substance use | F11–F19 | 53,669 | 11.8 | (11.9) | 54.2 | 13.3 | 11.2 | 7.2 |

| 180 | Schizophreniac | F20 | 29,422 | 6.5 | (6.5) | 58.2 | 7.1 | 6.6 | 2.2 |

| 181 | Schizotypal and delusional disorders | F21–F29 | 39,694 | 8.7 | (8.8) | 50.3 | 9.2 | 8.7 | 6.2 |

| 182 | Bipolar affective disorderc | F30–F31 | 22,669 | 5.0 | (5.0) | 40.6 | 3.6 | 6.2 | 5.7 |

| 183 | Depressionc | F32, F33, F34.1, F06.32 | 454,933 | 99.9 | (100.2) | 35.5 | 79.1 | 107.5 | 165.8 |

| 184 | Mood (affective) disorders | F340, F348–F349, F38–F39 | 6887 | 1.5 | (1.5) | 35.9 | 1.3 | 1.6 | 1.7 |

| 185 | Phobic anxiety disorders | F40 | 14,324 | 3.1 | (3.2) | 33.4 | 5.0 | 1.9 | 0.3 |

| 186 | Other anxiety disorders | F41 | 38,079 | 8.4 | (8.4) | 32.6 | 10.0 | 7.3 | 5.3 |

| 187 | Obsessive compulsive disorder (OCD)c | F42 | 10,062 | 2.2 | (2.2) | 36.7 | 3.8 | 1.0 | 0.5 |

| 188 | Post-traumatic stress disorder | F431 | 16,055 | 3.5 | (3.6) | 48.6 | 3.9 | 3.8 | 0.4 |

| 189 | Reactions to severe stress and adjustment disorders | F432–F439 | 61,701 | 13.5 | (13.7) | 39.1 | 18.6 | 10.4 | 4.4 |

| 190 | Dissociative (conversion) disorders, somatoform disorders and other neurotic disorders | F44, F45, F48 | 21,420 | 4.7 | (4.7) | 31.7 | 4.6 | 5.2 | 3.1 |

| 191 | Eating disorders | F50 | 7751 | 1.7 | (1.7) | 5.2 | 3.5 | 0.3 | 0.1 |

| 192 | Behavioural syndromes associated with physiological disturbances and physical factors | F51–F59 | 6163 | 1.4 | (1.3) | 46.3 | 1.9 | 1.0 | 0.3 |

| 193 | Emotionally unstable personality disorder | F603 | 21,848 | 4.8 | (4.9) | 21.2 | 7.7 | 2.8 | 0.2 |

| 194 | Specific personality disorders | F602, F604–F609 | 50,415 | 11.1 | (11.2) | 39.3 | 14.4 | 9.4 | 2.7 |

| 195 | Disorders of adult personality and behaviour | F61–F69 | 17,533 | 3.8 | (3.9) | 44.3 | 5.0 | 3.3 | 0.7 |

| 196 | Mental retardation | F70–F79 | 13,822 | 3.0 | (3.1) | 53.9 | 3.8 | 2.6 | 1.2 |

| 197 | Disorders of psychological development | F80–F89 | 9911 | 2.2 | (2.2) | 65.4 | 4.1 | 0.6 | 0.3 |

| 198 | Hyperkinetic disorders (ADHD)c | F90 | 42,908 | 9.4 | (9.5) | 60.6 | 17.1 | 3.5 | 1.0 |

| 199 | Behavioural and emotional disorders with onset usually occurring in childhood and adolescence | F91–F99 | 39,602 | 8.7 | (8.8) | 48.3 | 11.8 | 6.6 | 3.7 |

| Having one or more chronic conditions | 2,989,441 | 656.2 | (657.2) | 45.5 | 480.5 | 771.5 | 953.9 | ||

Standardised rates in brackets

See table with 10-year age intervals in Supplementary Material 2 in the electronic supplementary material

Conditions marked ‘A’, overlap with other conditions and are thus not counted twice [44]

ICD-10 International Statistical Classification of Diseases, 10th Revision

c Complex defined conditions; see reference for further details [44]

** 2-year prevalence

In general, prevalence naturally increases with increasing age across most conditions (see also Supplementary Material 2 and 6 with 10-year age intervals). Moreover, patients are relatively older within cancers and endocrine, nutritional and metabolic diseases and diseases of the circulatory system, the eye and adnexa, the ear and mastoid process, and the musculoskeletal system and connective tissue compared to within other conditions. A relatively younger patient population is seen within diseases of the respiratory system (especially allergies and asthma) and mental- and behavioural disorders. Mental disorders actually show a decrease in prevalence in later life. The conditions with the youngest population are, for example, seen within human immunodeficiency virus (HIV) and hepatitis.

Gender differences are seen across conditions, where women are overrepresented within most conditions—except, for example, heart failure and ischaemic heart diseases, stroke, some cancers, diabetes, disturbances in lipoprotein circulation and other lipids, inguinal hernia, hearing loss such as tinnitus, chronic renal failure, sleep disorders, schizophrenia, attention deficit/hyperactivity disorder (ADHD), mental and behavioural disorders due to the use of alcohol, and others. Coherently, women are treated more often than men with medication, except for ischaemic heart medications.

Some further characteristics and differences between conditions are seen and described in Supplementary Material 1–6. This includes geographic regional tables, further age characteristics with mean age and SD, more age intervals, further comments on common selected conditions and regional differences, etc.

Discussion

Based on the present findings, almost two-thirds of the entire Danish population aged 16 years or above have one or more chronic condition. Seen in the context of previous studies, this is around 10–20 percentage points higher than several other Danish studies [6, 7] as well as international studies [27, 28]. The overall estimates are also twice the official estimates of the Danish National Board of Health [8]. However, both national and international comparisons are difficult due to differences in methodology and data possibilities, so estimates should be compared with caution. For example, some American studies report that about 50% of the US population has a chronic condition [52, 53], but reliable overall estimates are difficult to obtain as to why improvement has been recommended [17]. Furthermore, as the US often has higher disease prevalence than the EU—often differing by 20–100% across different conditions [54] —the present study suggests that the US estimates might be even higher.

Strengths and Limitations

The strength of this study is the detailed, full nationwide register-based collection and categorisation of all data on actual chronic conditions and treatments for Danes in public and private healthcare. Several limitations exist, however, one being the obvious fact that being treated for a chronic condition is not necessarily the same as being truly ill. There may be cases of defensive medicine or patients being treated on suspicion of a chronic disease, or even wrong (over-) diagnosis.

As found in previous studies, one of the main limitations of register studies in general is the opposite, i.e. not being able to identify either chronic patients who have not been treated or diagnosed at any time or patients with self-treated conditions, who consequently are not reported in hospital or other registers (i.e. data source limitations, etc.) [44, 55]. This may lead to under-reporting of some less severe chronic conditions, such as asthma, allergies, COPD and type 2 diabetes, which are mostly treated in primary care where there is no reporting of diagnoses. The same might apply for other conditions such as glaucoma, cataracts, age-related hearing loss, other eye and ear conditions, and less severe mental conditions that are untreated, such as mild forms of depression or anxiety [44]. Thus, differences in the present study are compared with the national self-reported prevalence rates for 2013 for 18 broadly defined conditions where possible, since they cover a wide range of conditions of importance for assessment [6]. In comparison, differences and limitations of register-based definitions might be found within four of the 18 conditions: osteoarthritis, migraine/headache, tinnitus and cataracts. These conditions are discussed in more detail in Supplementary Material 3. All in all, these register-based less severe conditions may not be sufficiently estimated at this time, which is why register-based prevalence will be underestimated and should be used with caution.

While some estimated conditions show limitations compared to self-reported conditions, most other conditions, such as hypertension, rheumatoid arthritis, osteoporosis, diabetes, COPD, bronchitis and other lung diseases, cancers, heart condition and stroke, all have higher or slightly higher register-based than self-reported prevalence [6], as well as estimates in line with other studies [7, 10, 33, 55, 56]. The same applies to mental conditions overall, which typically have a lower survey response [57], which could explain the lower self-reported prevalence. Added to the fact that these estimates are free of self-reported bias, this clearly strengthens the reliability of most register-based conditions reported, not to mention the enhanced precision of doctor-reported diagnoses.

However, similar to non-registration issues in community-based surveys, misclassification issues also exist in register studies as sources of bias. Reasons for this include different coding practices between hospitals [30], different access to specialists, clinical disagreements, different clinical and administrative practices and interpretation of the ICD-10 criteria [58]. However, we do not have evidence of systemic misclassification. On the contrary, studies have validated reported diagnoses from registers for several psychiatric and somatic conditions, with good overall results [55, 59–64]. Nevertheless, the estimates of some complex-aetiology, ill-defined and debated rheumatoid conditions such as fibromyalgia and chronic fatigue syndrome, even though common, should be used with caution since they are clearly under-reported compared to other studies [58, 65, 66]. Further discussion and references regarding the validity of diagnosis codes in registers can be found elsewhere [44].

In summary, the prevalence of some less severe conditions may be underestimated in register studies [55]. On the other hand, community-based self-reported studies may underestimate, especially, the more severe conditions due to, among other things, non-responders as well as people living in institutions or jails, homeless people, and those currently in inpatient treatment. Existing studies have already shown varying or poor overlap between self-reports and hospital reports [67], some concluding that the use of self-reports is less reliable in cases of, for example, stroke and ischaemic heart disease [68, 69], while severe conditions [67] such as cancers cannot reliably be self-diagnosed. Thus, a strength of the current study is that moderate or severe conditions are estimated more accurately and are naturally free of the bias of self-reported conditions. From this perspective, community-based survey studies contrast with and complement register studies [55].

Another strength of the study is that the definitions used were evaluated by epidemiologists and clinicians to strengthen reliability and provide the best possible representation [44]. In addition, the long register time periods are noticeable strengths compared to other register studies [7, 24, 26, 29–31]. Lastly, the use of a complete population of 4,555,439 people, not to mention the large number of ICD-10 doctor-reported conditions included, is another strength not or rarely seen in other studies.

Implications

Existing international register studies usually help determine current disease burden with implications for, for example, the funding of new treatments or others—but usually not multiple conditions [70–72].

The prevalence estimates of the current study provide unbiased, independent important basic information regarding the burden of disease for use in healthcare planning, as well as economic, aetiological and other research for a broad range of conditions. As it is based on uniform methodology within a single study, it also makes reliable comparisons, contrary to most existing studies. In many types of health economic studies, such as analyses of cost of illness and the budgetary consequences of the introduction of new health technologies, economic calculations may not provide an accurate, reliable picture if based on invalid information. This comprehensive catalogue of prevalence information of nationwide chronic conditions enables comprehensive comparisons of chronic diseases for policymakers, patient associations and researchers. Thus, it may serve as an off-the-shelf tool for decision makers and researchers for health economic modelling.

Future Studies

The World Health Organization (WHO) have recommended further improvement in data surveillance of chronic conditions worldwide [17]; in addition, other studies have criticised, as well as recommended, methodological improvements [73–76]. Future studies should compare these prevalence rates based on actual patient pathways and registrations of treatment with other methods for estimating disease prevalence. Future studies could also focus on the development over time of disease burden, including the newest register data and analysis of possible trends in diagnosis or possible over-diagnosis. Moreover, while there are several studies exploring the coherence between self-reported conditions and hospital records, we found no studies assessing whether less severe self-reported conditions are more accurately estimated than register-reported conditions. Further studies should be carried out to assess whether chosen less severe self-reported conditions are estimated accurately, and if so, how register and self-reported study designs could best complement each other and for which conditions.

Conclusions

The current study provides a catalogue of prevalence for 199 different doctor-reported chronic conditions and groups of conditions by gender, based on a complete nationwide population sample.

To the best of the authors’ knowledge, this study provides the most comprehensive descriptive register study of the prevalence of treatment of chronic conditions. Hence, the overall prevalence rate found is higher than that found in several previous studies, indicating that almost two-thirds of the entire Danish population aged 16 years or above either have a hospital diagnosis and/or are in medical treatment for one or more chronic condition.

Electronic supplementary material

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Acknowledgements

Special thanks to data management specialists Ole Schou Rasmussen and Thomas Mulvad Larsen from the North Denmark Region, and Niels Bohrs Vej, 9220 Aalborg OE, Denmark, for very useful and helpful suggestions and assistance in data management and SAS programming of the definitions, which has been much appreciated.

Author Contributions

All authors contributed to the study design. MFH did all data collection and programming and drafted the manuscript. All authors discussed and interpreted empirical findings. Critical manuscript revision and final approval of the manuscript was done by all authors.

Data Availability Statement

Due to the European General Data Protection Regulation (GDPR) and Danish data protection laws, it is not possible to provide the individually based, personal data of the current study directly. However, researchers can apply to Statistics Denmark for access to the data described in the “Methods” section. Thus, the same data of the current study can be provided via Statistics Denmark if the applicant fulfils legal and other requirements. See https://www.dst.dk/da/TilSalg/Forskningsservice. Software codes can be provided by the author when relevant, and data can be legally accessed, etc.

Compliance with Ethical Standards

Funding

The project was supported financially by the North Denmark Region, the Tax Foundation (public) and Aalborg University.

Conflict of interest

Michael Falk Hvidberg: None declared. Soeren Paaske Johnsen: None declared. Michael Davidsen: None declared. Lars Ehlers: None declared.

References

- 1.Makady A, ten Ham R, de Boer A, Hillege H, Klungel O, Goettsch W. Policies for use of real-world data in health technology assessment (HTA): a comparative study of six HTA agencies. Value Health [Internet]. Elsevier Inc. 2017;20:520–532. doi: 10.1016/j.jval.2016.12.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Garrison LP, Neumann PJ, Erickson P, Marshall D, Mullins CD. Using real-world data for coverage and payment decisions: the ISPOR Real-World Data Task Force report. Value Health [Internet]. International Society for Pharmacoeconomics and Outcomes Research (ISPOR) 2007;10:326–335. doi: 10.1111/j.1524-4733.2007.00186.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Mauskopf J, Earnshaw SR, Brogan A, Wolowacz SBT. Budget-impact analysis of health care interventions. Manchester: Adis; 2017. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Angelis A, Tordrup D, Kanavos P. Socio-economic burden of rare diseases: a systematic review of cost of illness evidence. Health Policy (New York) [Internet]; Elsevier Ireland Ltd. 2015;119:964–979. doi: 10.1016/j.healthpol.2014.12.016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Faleiros DR, Álvares J, Almeida AM, de Araújo VE, Andrade EIG, Godman BB, et al. Budget impact analysis of medicines: updated systematic review and implications. Expert Rev Pharmacoecon Outcomes Res [Internet] 2016;16:257–266. doi: 10.1586/14737167.2016.1159958. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Christensen AI, Davidsen M, Ekholm O, Pedersen PV, Juel K. Danskernes sundhed—den nationale sundhedsprofil 2013 [Danes health—the national health profile 2013] [Internet]. Sundhedsstyrelsen [National Board Heal. Copenhagen K, Denmark; 2014. http://www.si-folkesundhed.dk/Udgivelser/Bøgerograpporter/2014/Danskernessundhed-dennationalesundhedsprofil2013.aspx.

- 7.Robinson KM, Juel Lau C, Jeppesen M, Vind AB, Glümer C. Kroniske sygdomme—forekomst af kroniske sygdomme og forbrug af sundhedsydelser i Region Hovedstaden v2.0 [Chronic diseases—prevalence of chronic diseases and use of health services in the Capital Region v2.0] [Internet]. Forskningscenter Forebygg. og Sundh. [Research Cent. Prev. Heal. Glostrup, Denmark; 2012. https://www.regionh.dk/fcfs/publikationer/Documents/Kroniskesygdomme-forekomstafkroniskesygdommeogforbrugafsundhedsydelseriRegionHovedstaden.pdf.

- 8.Sundhedsstyrelsen [Danish National Board of Health]. Kronisk sygdom [Chronic Illness] [Internet]; 2017. https://www.sst.dk/da/sygdom-og-behandling/kronisk-sygdom#. Cited 25 May 2017.

- 9.Rosendahl Jensen HA, Davidsen M, Ekholm O, Christensen AI. Danskernes Sundhed—Den Nationale Sundhedsprofil 2017 [Danes health—the national health profile 2017] [Internet]. Sundhedsstyrelsen [National Board Heal. Copenhagen K; 2018. http://www.si-folkesundhed.dk/Udgivelser/Bøgerograpporter/2018/DanskernesSundhed.DenNationaleSundhedsprofil2017.aspx.

- 10.Lau C, Lykke M, Andreasen A, Bekker-Jeppesen M, Buhelt L, Robinson K, et al. Sundhedsprofil 2013—Kronisk Sygdom [Health Profile 2013—Chronic Disease] [Internet]. Glostrup Hospital, Nordre Ringvej 57, Afsnit 84-85, 2600 Glostrup, Copenhagen Denmark e-mail: fcfs@regionh.dk, Denmark; 2015. https://www.regionh.dk/fcfs/publikationer/Documents/Sundhedsprofil2013-Kronisksygdom.pdf. Cited 2 July 2015.

- 11.Naghavi M, Wang H, Lozano R, Davis A, Liang X, Zhou M, et al. Global, regional, and national age–sex specific all-cause and cause-specific mortality for 240 causes of death, 1990–2013: a systematic analysis for the Global Burden of Disease Study 2013. Lancet [Internet]. Elsevier Ltd. 2015;385:117–171. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(14)61682-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Murray CJL, Ezzati M, Flaxman A. Supplementary appendix—comprehensive systematic analysis of global epidemiology: definitions, methods, simplification of DALYs, and comparative results from the Global Burden of Disease Study 2010. Lancet [Internet]. 2012;380:2063–66. http://linkinghub.elsevier.com/retrieve/pii/S0140673615606924.

- 13.Murray Christopher JL, Ezzati Majid, Flaxman Abraham D, Lim Stephen, Lozano Rafael, Michaud Catherine, Naghavi Mohsen, Salomon Joshua A, Shibuya Kenji, Vos Theo, Wikler Daniel, Lopez Alan D. GBD 2010: design, definitions, and metrics. The Lancet. 2012;380(9859):2063–2066. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(12)61899-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Vos T, Barber RM, Bell B, Bertozzi-Villa A, Biryukov S, Bolliger I, et al. Global, regional, and national incidence, prevalence, and years lived with disability for 301 acute and chronic diseases and injuries in 188 countries, 1990–2013: a systematic analysis for the Global Burden of Disease Study 2013. Lancet [Internet]. 2015;386:743–800. http://linkinghub.elsevier.com/retrieve/pii/S0140673615606924. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 15.World Health Organization (WHO). World Health Statistics 2015 [Internet]. World H. 2015. p. 164. http://apps.who.int/iris/bitstream/10665/148114/1/9789241564854_eng.pdf?ua=1. Cited 22 Apr 2016.

- 16.World Health Organization (WHO). Global status report on noncommunicable diseases 2014 [Internet]. World Health; 2014. http://www.who.int/nmh/publications/ncd-status-report-2014/en/. Cited 18 Nov 2015.

- 17.World Health Organization (WHO). Global status report on noncommunicable diseases 2010 [Internet]. World Health; 2010. http://www.who.int/nmh/publications/ncd_report2010/en/. Cited 18 Nov 2015.

- 18.Murray CJL, Barber RM, Foreman KJ, Ozgoren AA, Abd-Allah F, Abera SF, et al. Global, regional, and national disability-adjusted life years (DALYs) for 306 diseases and injuries and healthy life expectancy (HALE) for 188 countries, 1990-2013: quantifying the epidemiological transition. Lancet [Internet]. 2015;386:2145–91. http://www.thelancet.com/journals/lancet/article/PIIS0140-6736(15)61340-X/abstract. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 19.Murray CJL, Vos T, Lozano R, Naghavi M, Flaxman AD, Michaud C, et al. Disability-adjusted life years (DALYs) for 291 diseases and injuries in 21 regions, 1990–2010: a systematic analysis for the Global Burden of Disease Study 2010. Lancet [Internet]. 2012;380:2197–223. http://linkinghub.elsevier.com/retrieve/pii/S0140673612616894. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 20.Murray CJL, Lopez AD. The global burden of disease: a comprehensive assessment of mortality and disability from deceases, injuries and risk factors in 1990 and projected to 2010 [Internet]. Harvard Univ. Press. World Health Organization; 1996. http://apps.who.int/iris/bitstream/10665/41864/1/0965546608_eng.pdf.

- 21.Schiller JS, Lucas JW, Ward BW, Peregoy JA. Summary health statistics for U.S. adults: National Health Interview Survey, 2011. Vital Heal Stat [Internet]. 2012;10:1–207. http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/22834228. [PubMed]

- 22.Garrett Nancy, Martini E. Mary. The Boomers Are Coming: A Total Cost of Care Model of The Impact of Population Aging on The Cost of Chronic Conditions in The United States. Disease Management. 2007;10(2):51–60. doi: 10.1089/dis.2006.630. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Sundhedsstyrelsen [Danish National Board of Health]. Kronisk sygdom: patient, sundhedsvæsen og samfund [Chronic conditions: patient, health care and society] [Internet]. Natl. Boards Heal. Copenhagen: Sundhedsstyrelsen; 2005. http://www.sst.dk/publ/Publ2005/PLAN/Kronikere/Kronisk_sygdom_patient_sundhedsvaesen_samfund.pdf. Cited 1 May 2015.

- 24.Esteban-Vasallo M., Dominguez-Berjon M., Astray-Mochales J, Genova-Maleras R, Perez-Sania A, Sanchez-Perruca L, Aguilera-Guzman M, Gonzalez-Sanz F. Epidemiological usefulness of population-based electronic clinical records in primary care: estimation of the prevalence of chronic diseases. Family Practice. 2009;26(6):445–454. doi: 10.1093/fampra/cmp062. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Epping-Jordan J, Pruitt S, Bengoa R, Wagner E. Improving the quality of health care for chronic conditions. Qual Saf Health Care [Internet]. 2004;13:299–305. http://qualitysafety.bmj.com/lookup/doi/10.1136/qshc.2004.010744. Cited 22 Mar 2015. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 26.Wiréhn Ann-Britt E., Karlsson H. Mikael, Carstensen John M. Estimating disease prevalence using a population-based administrative healthcare database. Scandinavian Journal of Public Health. 2007;35(4):424–431. doi: 10.1080/14034940701195230. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Schneider KM, O’Donnell BE, Dean D. Prevalence of multiple chronic conditions in the United States’ Medicare population. Health Qual Life Outcomes [Internet]. 2009;7:82. http://www.pubmedcentral.nih.gov/articlerender.fcgi?artid=2748070&tool=pmcentrez&rendertype=abstract. Cited 20 Apr 2014. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 28.Vogeli C, Shields AE, Lee T a, Gibson TB, Marder WD, Weiss KB, et al. Multiple chronic conditions: prevalence, health consequences, and implications for quality, care management, and costs. J Gen Intern Med [Internet]. 2007;22:391–5. http://www.pubmedcentral.nih.gov/articlerender.fcgi?artid=2150598&tool=pmcentrez&rendertype=abstract. Cited 26 Mar 2014. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 29.Klinisk Epidemiologisk Afdeling [Department of Clinical Epidemiology]. Sygehuskontakter og lægemiddelforbrug for udvalgte kroniske sygdomme i Region Nordjylland [Hospital contacts and drug consumption for selected chronic diseases in North Jutland] [Internet]. Dep Clin Epidemiol. Denmark; 2007. http://www.kea.au.dk/file/pdf/36.pdf. Cited 1 May 2014.

- 30.Sundhedsstyrelsen [Danish National Board of Health]. Beskrivelse af Sundhedsstyrelsens monitorering af kronisk sygdom [Description of National Board of Health’s monitoring of chronic disease] [Internet]. Natl Board Health; 2012. http://www.ssi.dk/~/media/Indhold/DK-dansk/Sundhedsdataogit/NSF/Dataformidling/Sundhedsdata/Kroniker/MetodebeskrivelseafSundhedsstyrelsensmonitoreringafkronisksygdom.ashx. Cited 15 June 2015.

- 31.Statens Serum Institute. Monitorering af kronisk sygdom hos Statens Serum Institut [Monitoring of chronic disease at Statens Serum Institute] [Internet]. Statens Serum Inst.; 2012. http://www.ssi.dk/Sundhedsdataogit/Sundhedsvaesenetital/Monitoreringer/Kronisksygdom/Monitorering-Kronisksygdom2011.aspx. Cited 10 Nov 2014.

- 32.Hommel K., Rasmussen S., Madsen M., Kamper A.-L. The Danish Registry on Regular Dialysis and Transplantation:completeness and validity of incident patient registration. Nephrology Dialysis Transplantation. 2009;25(3):947–951. doi: 10.1093/ndt/gfp571. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Carstensen Bendix, Kristensen Jette Kolding, Marcussen Morten Munk, Borch-Johnsen Knut. The National Diabetes Register. Scandinavian Journal of Public Health. 2011;39(7_suppl):58–61. doi: 10.1177/1403494811404278. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Info@norpen.org. Nordic PharmacoEpidemiological Network (NorPEN) [Internet]. http://www.norpen.org/pages/publications.html. Cited 16 Apr 2019.

- 35.Wettermark B, Persson ME, Wilking N, Kalin M, Korkmaz S, Hjemdahl P, et al. Forecasting drug utilization and expenditure in a metropolitan health region. BMC Health Serv Res. 2010;10. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 36.Eriksson I, Wettermark B, Persson M, Edström M, Godman B, Lindhé A, et al. The early awareness and alert system in Sweden: history and current status. Front Pharmacol. 2017;8:1–8. doi: 10.3389/fphar.2017.00674. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Olsen Jørn, Basso Olga, Sørensen Henrik Toft. What is a population-based registry? Scandinavian Journal of Public Health. 1999;27(1):78–78. doi: 10.1177/14034948990270010601. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Kamper-Jørgensen F. New editor and new publisher for the Scandinavian Journal of Public Health. Scand J Public Health. 2008;36:1–2. doi: 10.1177/1403494807087289. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Lynge Elsebeth, Sandegaard Jakob Lynge, Rebolj Matejka. The Danish National Patient Register. Scandinavian Journal of Public Health. 2011;39(7_suppl):30–33. doi: 10.1177/1403494811401482. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Mors Ole, Perto Gurli P., Mortensen Preben Bo. The Danish Psychiatric Central Research Register. Scandinavian Journal of Public Health. 2011;39(7_suppl):54–57. doi: 10.1177/1403494810395825. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Sahl Andersen John, De Fine Olivarius Niels, Krasnik Allan. The Danish National Health Service Register. Scandinavian Journal of Public Health. 2011;39(7_suppl):34–37. doi: 10.1177/1403494810394718. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Wallach Kildemoes Helle, Toft Sørensen Henrik, Hallas Jesper. The Danish National Prescription Registry. Scandinavian Journal of Public Health. 2011;39(7_suppl):38–41. doi: 10.1177/1403494810394717. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Pedersen CB, Gøtzsche H, Møller JO, Mortensen PB. The Danish Civil Registration System. A cohort of eight million persons. Dan Med Bull [Internet]. 2006;53:441–9. http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/17150149. [PubMed]

- 44.Hvidberg Michael F., Johnsen Søren P., Glümer Charlotte, Petersen Karin D., Olesen Anne V., Ehlers Lars. Catalog of 199 register-based definitions of chronic conditions. Scandinavian Journal of Public Health. 2016;44(5):462–479. doi: 10.1177/1403494816641553. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Hvidberg Michael F., Johnsen Søren P., Glümer Charlotte, Petersen Karin D., Olesen Anne V., Ehlers Lars. Catalog of 199 register-based definitions of chronic conditions. Scandinavian Journal of Public Health. 2016;44(5):462–479. doi: 10.1177/1403494816641553. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Hvidberg M. A framework for identifying disease burden and estimating health-related quality of life and prevalence rates for 199 medically defined conditions. Aalborg: Aalborg University Press; 2016. [Google Scholar]

- 47.Paez Kathryn Anne, Zhao Lan, Hwang Wenke. Rising Out-Of-Pocket Spending For Chronic Conditions: A Ten-Year Trend. Health Affairs. 2009;28(1):15–25. doi: 10.1377/hlthaff.28.1.15. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Sullivan PW, Ghushchyan V. Preference-based EQ-5D index scores for chronic conditions in the United States. Med Decis Making [Internet]. 2006;26:410–20. http://www.pubmedcentral.nih.gov/articlerender.fcgi?artid=2634296&tool=pmcentrez&rendertype=abstract. Cited 23 Apr 2012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 49.Sullivan Patrick W., Slejko Julia F., Sculpher Mark J., Ghushchyan Vahram. Catalogue of EQ-5D Scores for the United Kingdom. Medical Decision Making. 2011;31(6):800–804. doi: 10.1177/0272989X11401031. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Naing NN. Easy way to learn standardization: direct and indirect methods. Malays J Med Sci [Internet]. 2000;7:10–5. http://www.pubmedcentral.nih.gov/articlerender.fcgi?artid=3406211&tool=pmcentrez&rendertype=abstract. [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 51.Jensen Vibeke M., Rasmussen Astrid W. Danish education registers. Scandinavian Journal of Public Health. 2011;39(7_suppl):91–94. doi: 10.1177/1403494810394715. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Ward BW, Schiller JS, Goodman RA. Multiple chronic conditions among US adults: a 2012 update. Prev Chronic Dis [Internet]. 2014;11:130389. http://www.cdc.gov/pcd/issues/2014/13_0389.htm. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 53.Centers for Disease Control (CDC). Chronic diseases: the leading causes of death and disability in the United States [Internet]. Chronic Dis. Overv. 2015. http://www.cdc.gov/chronicdisease/overview/index.htm.

- 54.Thorpe KE, Howard DH, Galactionova K. Differences in disease prevalence as a source of the U.S.-European health care spending gap. Health Aff [Internet]. 2007;26. http://www.euro.who.int/_data/assets/pdf_file/0008/96632/E93736.pdf. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 55.Pedersen Carsten Bøcker, Mors Ole, Bertelsen Aksel, Waltoft Berit Lindum, Agerbo Esben, McGrath John J., Mortensen Preben Bo, Eaton William W. A Comprehensive Nationwide Study of the Incidence Rate and Lifetime Risk for Treated Mental Disorders. JAMA Psychiatry. 2014;71(5):573. doi: 10.1001/jamapsychiatry.2014.16. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Christensen Jakob, Vestergaard Mogens, Pedersen Marianne G., Pedersen Carsten B., Olsen Jørn, Sidenius Per. Incidence and prevalence of epilepsy in Denmark. Epilepsy Research. 2007;76(1):60–65. doi: 10.1016/j.eplepsyres.2007.06.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Alonso J., Angermeyer M.C., Lepine J.P. The European Study of the Epidemiology of Mental Disorders (ESEMeD) project: an epidemiological basis for informing mental health policies in Europe. Acta Psychiatrica Scandinavica. 2004;109(s420):5–7. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0047.2004.00325.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Falk Hvidberg M, Brinth LS, Olesen A V., Petersen KD, Ehlers L. The health-related quality of life for patients with myalgic encephalomyelitis/chronic fatigue syndrome (ME/CFS). Furlan R, editor. PLoS One [Internet]. 2015;10. http://dx.plos.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0132421. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 59.Kessing LV. Validity of diagnoses and other clinical register data in patients with affective disorder. European Psychiatry. 1998;13(8):392–398. doi: 10.1016/S0924-9338(99)80685-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Pedersen Merete, Klarlund Mette, Jacobsen Søren, Svendsen Anders J., Frisch Morten. Validity of rheumatoid arthritis diagnoses in the Danish National Patient Registry. European Journal of Epidemiology. 2004;19(12):1097–1103. doi: 10.1007/s10654-004-1025-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Phung Thien Kieu Thi, Andersen Birgitte Bo, Høgh Peter, Kessing Lars Vedel, Mortensen Preben Bo, Waldemar Gunhild. Validity of Dementia Diagnoses in the Danish Hospital Registers. Dementia and Geriatric Cognitive Disorders. 2007;24(3):220–228. doi: 10.1159/000107084. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Bock C, Bukh J, Vinberg M, Gether U, Kessing L. Validity of the diagnosis of a single depressive episode in a case register. Clin Pract Epidemiol Ment Health [Internet]. 2009;5:4. http://www.pubmedcentral.nih.gov/articlerender.fcgi?artid=2660321&tool=pmcentrez&rendertype=abstract. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 63.Uggerby P, Østergaard SD, Røge R, Correll CU, Nielsen J. The validity of the schizophrenia diagnosis in the Danish Psychiatric Central Research Register is good. Dan Med J [Internet]. 2013;60:A4578. http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/23461991. [PubMed]

- 64.Thygesen SK, Christiansen CF, Christensen S, Lash TL, Sørensen HT. The predictive value of ICD-10 diagnostic coding used to assess Charlson comorbidity index conditions in the population-based Danish National Registry of Patients. BMC Med Res Methodol [Internet]. BioMed Central Ltd; 2011;11:83. http://www.pubmedcentral.nih.gov/articlerender.fcgi?artid=3125388&tool=pmcentrez&rendertype=abstract. Cited 27 Aug 2014. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 65.Deodhar Atul, Marcus Dawn A. Fibromyalgia. New York, NY: Springer New York; 2011. [Google Scholar]

- 66.Branco Jaime C., Bannwarth Bernard, Failde Inmaculada, Abello Carbonell Jordi, Blotman Francis, Spaeth Michael, Saraiva Fernando, Nacci Francesca, Thomas Eric, Caubère Jean-Paul, Le Lay Katell, Taieb Charles, Matucci-Cerinic Marco. Prevalence of Fibromyalgia: A Survey in Five European Countries. Seminars in Arthritis and Rheumatism. 2010;39(6):448–453. doi: 10.1016/j.semarthrit.2008.12.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Robinson KM, Juel Lau C, Jeppesen M, Vind AB, Glümer C. Kroniske sygdomme—hvordan opgøres kroniske sygdomme [Chronic disease—how is chronic disease defined] [Internet]. Glostrup Hospital, Nordre Ringvej 57, Afsnit 84-85, 2600 Glostrup, Copenhagen Denmark e-mail: fcfs@regionh.dk, Denmark; 2011. https://www.regionh.dk/fcfs/publikationer/nyhedsbreve/setember-2014/PublishingImages/Sider/NyKroniske_sygdomme__metoderapport.pdf. Cited 5 May 2014.

- 68.Carter Kristie, Barber P. Alan, Shaw Caroline. How Does Self-Reported History of Stroke Compare to Hospitalization Data in a Population-Based Survey in New Zealand? Stroke. 2010;41(11):2678–2680. doi: 10.1161/STROKEAHA.110.598268. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Bergmann M. M., Byers T., Freedman D. S., Mokdad A. Validity of Self-reported Diagnoses Leading to Hospitalization: A Comparison of Self-reports with Hospital Records in a Prospective Study of American Adults. American Journal of Epidemiology. 1998;147(10):969–977. doi: 10.1093/oxfordjournals.aje.a009387. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]