Abstract

Histone deacetylases (HDACs) influence chromatin state and gene expression. Eighteen HDAC genes with important biological functions have been identified in rice. In this study, we surveyed the gene presence frequency of all 18 rice HDAC genes in 3,010 rice accessions. HDA710/OsHDAC2 showed insertion/deletion (InDel) polymorphisms in almost 98.8% japonica accessions but only 1% indica accessions. InDel polymorphism association analysis showed that accessions with partial deletions in HDA710 tended to display early leaf senescence. Further transgenic results confirmed that HDA710 delayed leaf senescence in rice. The over-expression of HDA710 delayed leaf senescence, and the knock-down of HDA710 accelerated leaf senescence. Transcriptome analysis showed that photosynthesis and chlorophyll biosynthesis related genes were up-regulated in HDA710 over-expression lines, while some programmed cell death and disease resistance related genes were down-regulated. Co-expression network analysis with gene expression view revealed that HDA710 was co-expressed with multiple genes, particularly OsGSTU12, which was significantly up-regulated in 35S::HDA710-sense lines. InDels in the promoter region of OsGSTU12 and in the gene region of HDA710 occurred coincidentally among more than 90% accessions, and we identified multiple W-box motifs at the InDel position of OsGSTU12. Over-expression of OsGSTU12 also delayed leaf senescence in rice. Taken together, our results suggest that both HDA710 and OsGSTU12 are involved in regulating the process of leaf senescence in rice.

Keywords: HDA710, InDel polymorphism, leaf senescence, co-expression network, OsGSTU12, rice

Introduction

Epigenetic changes can reprogram the transcriptome during various biological processes. Acetylation and deacetylation of histones has emerged as a fundamental regulatory mechanism for the control of gene expression during plant development and in response to environmental conditions (Jang et al., 2003). Acetylation is a type of post-translational modification that changes as cells age, especially in animals (Sidler et al., 2017). With increasing age and senescence, H3K14ac, H4K8ac, and H4K12ac levels in mouse increase (Huang J. C. et al., 2007), and H3K56ac levels in mouse and human decrease (Dang et al., 2009; Feser et al., 2010; O'Sullivan et al., 2010), while H3K9ac and H4K16ac show different patterns in various species (Sidler et al., 2017). Histone deacetylases (HDACs) enable tightening of the chromatin structure into heterochromatin; thus, the deacetylation of histones is associated with compacting the DNA and repressing transcription. In eukaryotes, HDACs are grouped into three families: RPD3/HDA1 (Reduced Potassium Dependence 3/Histone Deacetylase 1), SIR2 (Silent Information Regulator), and HD2 (Histone Deacetylase 2)-related protein families (Pandey et al., 2002). SIRT1, a HDAC, deacetylates and inactivates the main transcriptional regulator of genes involved in inflammation processes associated with aging (Lawrence, 2009).

Plant HDACs represent a large family encoded by multiple genes, with different subcellular locations and expression profiles revealing their functional diversity (Schmid et al., 2005). Increasing evidence shows that plant HDACs play an important role in development, including flower development (Li C. et al., 2011), seed development (Wu et al., 2000), root development (Xu et al., 2005), cell proliferation and death (Nelissen et al., 2005; Huang L. et al., 2007; Bourque et al., 2011), and respond to various abiotic and biotic stresses (Sridha and Wu, 2006; Hu et al., 2011; Luo et al., 2012). Much about the functional diversity and redundancy of different HDACs remains unknown (Hollender and Liu, 2008). The RPD3/HDA1 group HDACs are further classified into three groups, among which class I is best characterized and contains four members, namely HDA19, HDA6, HDA7, and HDA9 in Arabidopsis. The down-regulation of Arabidopsis AtHD1 (HDA19) induces various developmental defects, including leaf early senescence; HDA6 and HDA19 are involved in abscisic acid (ABA) and abiotic stress responses; HDA9 can negatively regulate salt and drought responses (Chen and Tian, 2007; Chen and Wu, 2010; Zheng et al., 2016). Therefore, the level of acetylation mediated by deacetylases is critical for the senescence process and abiotic stress response of plants.

Rice is a staple food crop with two subspecies, japonica and indica, originating from tropical or subtropical areas (Zhang et al., 2017). Much work has been done in rice (Oryza sativa L.) to reveal the specific mechanisms involved in acquisition, inheritance, and resetting of epigenetic information (Zhao and Zhou, 2012). Rice contains 18 HDACs, which play an important role in response to abiotic stress and vegetative growth (Jang et al., 2003; Luo et al., 2017). In rice, down-regulation of RPD3/HDA1 class I type HDACs by RNAi or amiRNA leads to multiple developmental defects. For instance, HDA702/OsHDAC1 regulates plant growth rate and alters plant architecture (Jang et al., 2003; Chung et al., 2009). Down-regulation of HDA703/OsHDAC3 reduces rice peduncle elongation and fertility (Hu et al., 2009). HDA710/OsHDAC2 belongs to the class I-type HDACs and is located in the opposite orientation on chromosome 2 of japonica rice cultivar Nipponbare (Jang et al., 2003). An RNAi mutant of HDA710 showed severe phenotypes, including reduced vegetative growth, semi-dwarf and reduced elongation of peduncle (Hu et al., 2009). In the meanwhile, Rice HDACs play essential roles in response to stress and are related to cell death. For example, the down-regulation of HDAC OsSRT1 affects the level of H3K9ac, activating genes associated with apoptotic cell death (Huang L. et al., 2007). Expression of both HDA710 and HDA703 is induced by abiotic stresses, including drought, salt, and cold stresses (Jain et al., 2007), and is also up-regulated under methylviologen (MV) treatment (Liu et al., 2010). In addition, HDA710 and HDA703 are preferentially expressed in Nipponbare compared to the indica accession 9311 (Liu et al., 2010; Jung et al., 2013). There are differences in leaf senescence between indica and japonica rice, with senescence of indica varieties occurring earlier than that of japonica varieties (Abdelkhalik et al., 2005). Leaf senescence is an important stage of plant development. In agricultural production, early leaf senescence limits the cycle of crop photosynthesis and thus affects crop yields. However, little is known about the molecular mechanism underlying the differences in leaf senescence between the rice subspecies japonica and indica.

Associations between genotype and phenotype are beginning to elucidate how genetic differences contribute to phenotypic traits. The completion of the 3,000 Rice Genomes Project (3K RGP) has provided abundant genetic resources for facilitating research establishing gene-trait associations (Li et al., 2014; Alexandrov et al., 2015). Utilization of natural genetic variation contributes greatly to improvement of important agronomic traits in crops and provides valuable resources for crop genetics and breeding improvement (Duan et al., 2017). A number of quantitative trait loci (QTLs) and genes have been identified and characterized by QTL analysis employing natural variation in rice, including traits related to flowering time (Ogiso-Tanaka et al., 2013), grain yield (Huang et al., 2009; Li Y. B. et al., 2011), and low-temperature germination (Wang X. et al., 2018).

In this study, we investigated the gene presence frequency of all 18 previously identified rice HDAC genes in 3,010 rice varieties using the Rice Pan-genome Browser (RPAN) and analyzed associated agricultural traits. Delay of leaf senescence by HDA710 was further validated using transgenic approaches. To elucidate the possible regulatory mechanism of HDA710 during leaf senescence, we used RNA sequencing (RNA-Seq), co-expression network analyses, and functional analysis of downstream genes. Our work provides a novel direction for promoting molecular crop breeding.

Materials and Methods

Plant Materials

Rice (Nipponbare, Zhonghua17, 9311, Teqing, and transgenic lines of HDA710 and OsGSTU12) seeds were surface-sterilized in 5% (w/v) sodium hypochlorite for 20 min, washed in distilled water three or four times, then transferred to water at room temperature for 2 days followed by 37°C for 1 day to germinate. Seedlings were grown in a greenhouse (28/26°C and 12/12 h day/night) for about 2 weeks, then transplanted to natural conditions in a paddy field for phenotypic observation and experimental verification.

Construction of Transgenic Rice Lines

Over-expression and knock-down lines of HDA710 were generated in a Nipponbare background following a previously described method (Zhao et al., 2009), with the antisense and sense full-length CDS of HDA710 controlled by the CaMV 35S promoter. A construct with the CaMV 35S promoter driving the CDS of OsGSTU12 was developed for over-expression of OsGSTU12 in Zhonghua17 rice plants. Recombinant plasmids were introduced into Agrobacterium tumefaciens strain EHA105 using the freeze-thaw method (Jyothishwaran et al., 2007). Transgenic rice lines were regenerated through seed-induced callus of Nipponbare or Zhonghua17, respectively (Toki et al., 2006). Transgenic plants were identified by selection with 50 mg/L hygromycin B.

Characterization of Leaf and Whole-Plant Phenotypes

Chlorophyll content was measured in the flag leaf at the leaf tip, leaf center, and leaf base. Relative chlorophyll content was measured at multiple time points using a SPAD-502 Chlorophyll Meter, which is from Beijing Channel Science Equipment Company Limited. Phenotypic observation of fresh leaves and whole plants of each line was performed under natural conditions in the paddy fields.

Genotype and Phenotype Association Analysis

InDels in HDA710 and other HDACs among different rice accessions were identified from the RPAN database (http://cgm.sjtu.edu.cn/3kricedb/), which provides gene PAVs (presences and variances) for different rice accessions. The phylogenetic tree of five subspecies was also from RPAN database. The phenotypes identified for 2,266 rice accessions were downloaded from the Rice SNP-Seek Database (https://snp-seek.irri.org/_download.zul). Significance analysis of genotype and agronomic traits was performed using hypergeometric distribution, using the statistical formula displayed as follow.

In the formula, N is the total number of all accessions, n is the number of accessions with deletions, K is the total number of accessions shown one specific phenotype and k is the number of accessions with deletions shown the same phenotype.

Measurement of Chlorophyll Content

By Chlorophyll Meter

Chlorophyll content was measured using a SPAD-502 chlorophyll meter, which determines the relative content of the current chlorophyll of the leaf by measuring the difference in optical density at two wavelengths (650 and 940 nm) and automatically calculates the value. Each leaf blade was measured at three different locations: leaf base, leaf center, and leaf tip.

With Acetone Method

We took three leaves from three individual plants for each replicate to measure the chlorophyll content. Leaves were incubated in 80% acetone (v/v) for 3-6 h in the dark at 4°C then centrifuged for 10 min, 10,000 g at 4°C. Chlorophyll absorbance was measured at 646 and 663 nm, and chlorophyll contents were calculated as follows:

Measurement of Relative Electrical Conductivity

Relative electrical conductivity was determined by measuring electrolytes leaked from leaves. Sections flag leaf of the same size were immersed in 5 mL 100 mM mannitol for 3 h with gentle shaking, after which the initial conductivity was recorded as S1. Total conductivity was determined after boiling leaves in 100°C for 10 min, and was recorded as S2. Relative electric conductivity (REC) was calculated using the following formula:

RNA Isolation and qRT-PCR

All leaves were from natural conditions in paddy fields. Leaves were homogenized in liquid nitrogen and stored for a short time. Total RNA was isolated using TRIZOL® reagent (Invitrogen, CA, USA) and purified using Qiagen RNeasy columns (Qiagen, Hilden, Germany).

Reverse transcription was performed using Moloney murine leukemia virus (M-MLV; Invitrogen). A total volume of 10 μL containing 2 μg total purified RNA and 20 pmol random hexamers (Invitrogen) was heated at 70°C for 2 min and then chilled on ice for 2 min. M-MLV and the reaction buffer were added to a total volume of 20 μL containing 200 units of M-MLV, 20 pmol random hexamers, 500 μM dNTPs, 50 mM Tris-HCl (pH 8.3), 3 mM MgCl2, 75 mM KCl, and 5 mM dithiothreitol, and samples were then heated at 37°C for 1.5 h.

cDNA samples were diluted to 2 ng/μL for qRT-PCR assays performed on 1 μL of each cDNA dilution using SYBR Green Master Mix (Applied Biosystems, PN 4309155). The relative quantification method (ΔΔCT) was used to evaluate quantitative variation between replicates examined (Livak and Schmittgen, 2001). Primers for specific genes are listed in Table S7.

RNA-Seq Analysis

Sequencing libraries were constructed by Annoroad (China) and sequenced using NovaSeq following standard protocols. Paired-end mRNA-Seq data consisted of read lengths of 150 bp for each sample, with three replicates for each line. Sequencing data were aligned to rice genome MSU 6.1 using Tophat v2.0.10 (Kim et al., 2013) software with default parameters. Gene expression levels represented by FPKM (fragments per kilobase of transcript per million mapped reads) were calculated by Cufflinks v2.2.1 software using default parameters (Trapnell et al., 2010). Differentially expressed genes were defined based on fold change in expression levels and q-value. If the absolute fold change was more than 1.7 and q-value <0.05, genes were considered to be differentially expressed. Gene ontology enrichment analysis was performed using agriGO (Tian et al., 2017). The gene set enrichment analysis (GSEA) was performed through the PlantGSEA website (http://structuralbiology.cau.edu.cn/PlantGSEA/).

Immunoblots

Harvested leaves were ground in liquid nitrogen and the powder was extracted with Lysis buffer (50 mM HEPES pH 7.5, 150 mM NaCl, 1 mM EDTA, 1% TritonX-100 (v/v), 10% glycerol, 100 mM PMSF, 0.04% β-mercaptoethanol). The solution was placed on ice for 30 min and centrifuged for 20 min at 4,000 rpm at 4°C. Extracted proteins were separated on 12% SDS-PAGE gels and transferred to polyvinylidene difluoride (PVDF) membrane (Millipore, 0.22 μm). Membranes were blocked in blocking buffer [5% milk dissolved in 1 × TBST (Tris Buffered Saline with Tween 20)] at room temperature (24°C) for 1 h. Membranes were incubated overnight at room temperature with antibodies against H3K9ac (ab10812; Abcam), H3K27ac (ab4729; Abcam), and H3 (07-690; Millipore) in blocking buffer. After washing three times in TBST for 10 min each, membranes were incubated for 2 h at room temperature with horseradish peroxidase-labeled goat anti-rabbit diluted 1/5,000. Membranes were washed three times in TBST and incubated for 1 min in electrochemiluminescence (ECL) buffer (34095; ThermoFisher Scientific, http://www.thermofisher.com).

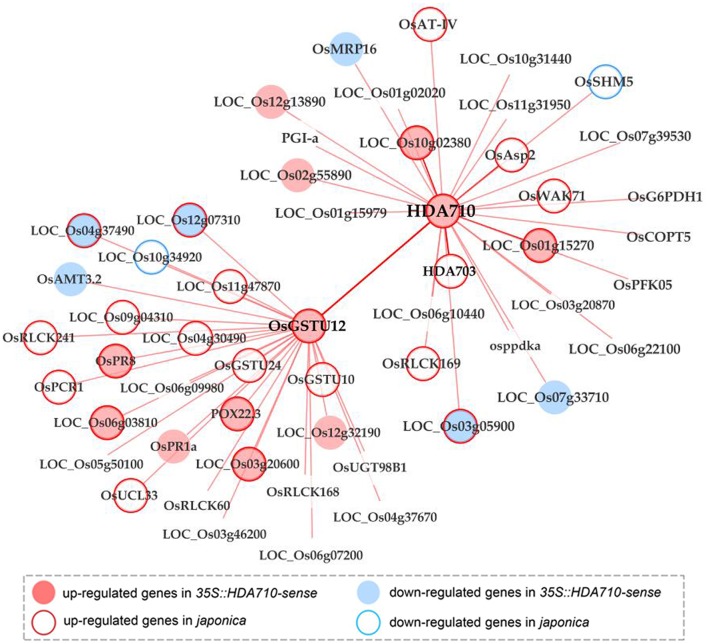

Co-expression Network Construction

Co-expressed genes were identified for two key genes, HDA710 and OsGSTU12, in the database RiceFREND (http://ricefrend.dna.affrc.go.jp). The top 300 co-expressed genes of HDA710 sorted by Mutual rank (MR) values were downloaded. These co-expressed genes were then used to construct a co-expression network. The network was displayed by Cytoscape software.

Differentially expressed genes between 35S::HDA710-sense and 35S::HDA710-antisense were determined using RNA-Seq analysis. Differentially expressed genes in representatives of the two subspecies of rice, japonica Nipponbare and indica 9311 were identified from microarray data (Liu et al., 2010). All genes in the network were annotated as up-regulated, down-regulated, or showing no significant change in expression between the two genotypes.

Results

Investigation of InDel Polymorphisms in HDACs of Five Oryza sativa Subgroups

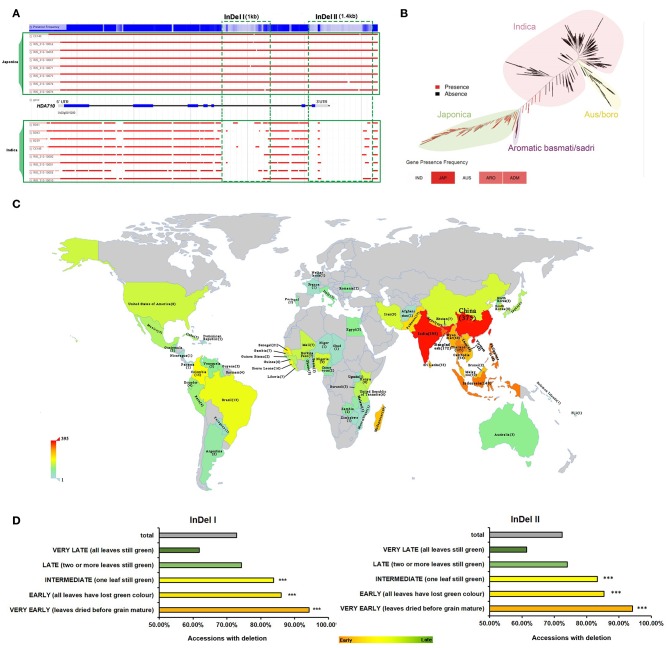

Eighteen HDAC genes have previously been identified in the rice genome (Hu et al., 2009). We searched for these HDAC genes in RPAN (http://cgm.sjtu.edu.cn/3kricedb/index.php) (Sun et al., 2017), for visual display of specific gene sequences in 3,010 rice accessions. We found significant insertion/deletion (InDel) polymorphisms in HDA710/OsHDAC2 and HDA703/OsHDAC3 between japonica-related (JAP, ARO) and indica-related (IND, AUS) accessions, especially for HDA710 (Table 1). RPAN results showed that HDA710 was present in almost 98.8% JAP accessions, and 37.6% japonica-like ARO accessions, while it was only present in 1% of IND accessions and 0.9% of indica-like AUS accessions (Table 1). The pan-genome browser based visualization of the presence/absence variation (PAVs) showed two InDels in the HDA710 gene region, one in the gene body named “InDel I” and the other in the downstream region named “InDel II” (Figure 1A), between indica and japonica accessions. As the Table S1 shown, there were detailed information of 3010 accessions. Among of them, 2106 accessions were listed with InDel I in HDA710, and 2104 accessions were listed with InDel II in HDA710. These two InDels co-existed in 2098 (99.6%) rice accessions. We further carried out the linkage disequilibrium analysis, and the D' and r2 values were 0.9905 and 0.9780, respectively.

Table 1.

Survey of RPAN gene presence frequency of rice histone deacetylases.

| Locus ID (MSU) | Locus ID (RAP) | Gene name | Gene presence frequency | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| JAP% | IND% | AUS% | ARO% | ADM% | |||

| LOC_Os01g40400 | Os01g0586400 | HDA701 | – | – | – | – | – |

| LOC_Os06g38470 | Os06g0583400 | HDA702/OsHDAC1 | 99.8 | 99.7 | 99.5 | 100 | 100 |

| LOC_Os02g12350 | Os02g0214900 | HDA703/OsHDAC3 | 95.8 | 28.1 | 69.7 | 82.2 | 52.8 |

| LOC_Os07g06980 | Os07g0164100 | HDA704 | 100 | 100 | 100 | 99.0 | 100 |

| LOC_Os08g25570 | Os08g0344100 | HDA705 | 100 | 99.9 | 100 | 100 | 100 |

| LOC_Os06g37420 | Os06g0571100 | HDA706/OsHDAC6 | 98.9 | 99.3 | 99.5 | 99.0 | 98.4 |

| LOC_Os01g12310 | – | HDA707 | – | – | – | – | – |

| LOC_Os11g09370 | Os11g0200000 | HDA709 | 99.1 | 97.8 | 98.6 | 99.0 | 98.4 |

| LOC_Os02g12380 | Os02g0215200 | HDA710/OsHDAC2 | 98.8 | 1.0 | 0.9 | 37.6 | 49.6 |

| LOC_Os04g33480 | Os04g0409600 | HDA711 | 98.1 | 98.2 | 95.5 | 97.0 | 98.4 |

| LOC_Os05g36920 | Os05g0440250 | HDA712 | 99.9 | 99.9 | 100.0 | 99.0 | 100.0 |

| LOC_Os07g41090 | Os07g0602200 | HDA713 | 99.9 | 99.9 | 100.0 | 99.0 | 99.2 |

| LOC_Os12g08220 | Os12g0182700 | HDA714/OsHDAC10 | 100 | 99.9 | 99.5 | 100 | 100 |

| LOC_Os05g36930 | Os05g0440300 | HDA716 | 100 | 99.8 | 100 | 100 | 100 |

| LOC_Os05g51830 | Os05g0597100 | HDT701 | 100 | 99.9 | 100 | 100 | 100 |

| LOC_Os01g68104 | Os01g0909100 | HDT702 | 100 | 100 | 100 | 99.0 | 100 |

| LOC_Os04g20270 | Os04g0271000 | SRT701/OsSRT1 | 100 | 99.9 | 99.1 | 99.0 | 100 |

| LOC_Os12g07950 | Os12g0179800 | SRT702/OsSir2b | 100 | 99.8 | 100 | 100 | 100 |

Gene Presence Frequency taken from RPAN (http://cgm.sjtu.edu.cn/3kricedb/index.php). JAP, japonica; IND, indica; AUS, aus/boro group, which is more closely related to indica; ARO, aromatic basmatic/sadri group, which is more closely related to japonica; ADM, admixed, intermediate types. The bold values highlighted genes which have significant differential polymorphisms between japonica-related and indica-related accessions.

Figure 1.

Natural variation in HDA710 between japonica and indica accessions and association with leaf senescence. (A) Sequence differences in HDA710 from indica and japonica accessions as presented by genome browser. (B) HDA710 distribution among different subspecies and subgroups in the rice phylogenetic tree. (C) Distribution of 2,112 accessions with deletion regions (“InDel I” or “InDel II”) in HDA710 from the 3,010 varieties at the International Rice Research Institute (IRRI). Color scale represents the number of accessions with InDels. (D) Leaf senescence phenotype analysis of accessions with deletions (“InDel I” and “InDel II”) by hypergeometric distribution (***P < 0.001). Different colors of bars represent degree of leaf senescence: green, accessions with late leaf senescence; yellow, accessions with early leaf senescence; gray, all accessions with deletion.

We searched for the HDA710 gene in RPAN to determine the distribution of this gene among 453 high-quality accessions, finding that HDA710 was dominant in japonica accessions and also present in japonica-like ARO and intermediate type ADM accessions (Figure 1B) (Sun et al., 2017). We also found that HDA703 differed among the five rice subgroups, being present in 95.8% japonica accessions and 82.2% ARO accessions, but only 28.1% indica accessions (Table 1).

To verify whether there are also differences in the expression of HDA710 and HDA703 between indica and japonica, we investigated microarray data for japonica rice cultivar Nipponbare and indica rice accession 9311 (Liu et al., 2010). The microarray data showed higher expression levels of HDA710 in Nipponbare than in 9311 (Table S2). Data from 983 Affymetrix microarrays from japonica and indica confirmed that HDA710 is highly expressed in japonica (Jung et al., 2013). The microarray data also indicated that HDA703 is highly expressed in Nipponare compared to 9311 (Table S2).

There were no significant differences in gene presence frequency for the other HDACs (Table 1). Based on the differences in genotype and expression profile of HDA710 compared with the other deacetylases, we proposed that HDA710 might be a key gene for the differentiation of indica and japonica rice in plant growth and development and stress resistance.

HDA710 Is Associated With Leaf Senescence by Gene-Trait Association Study

Through association analysis between genotypic diversity and corresponding phenotypic diversity, we can predict how the genotype contributes to the phenotype (Mansueto et al., 2017). The 3K RGP accessions were classified into different subpopulations, most of which could be connected to geographic origins (Wang W. et al., 2018). To explore whether the accessions with deletions were connected with the global climate, we examined the geographical distribution of 2,112 accessions harboring deletions in HDA710 (Figure 1A and Table S1) from the 3,010 accessions at the International Rice Research Institute (IRRI). We found that these accessions were mainly distributed in tropical and subtropical regions (Figure 1C). In addition to sequence information, more detailed phenotypic data (http://snp-seek.irri.org/download.zul) were available for 2,266 of these 3,010 accessions, allowing us to conduct a gene-trait association study. We examined the relationship between “InDel I”/“InDel II” (Figure 1A and Table S1) and multiple agronomic traits of the accessions, including panicle exsertion, awn presence, culm length, panicle threshability, seedling height, culm number, flag leaf angle, and leaf senescence. Leaf senescence was the most significant trait associated with genotype diversity. Some other agronomic traits were also associated. As shown in Figure S1, accessions with deletions exhibited partial panicle exsertion, awn absence, long culms, prolific culm number, easy panicle threshability, and erect flag leaves. Association analysis between the agronomic trait “leaf senescence” and the accessions with deletions showed that the 1,647 accessions with absence of the “InDel I” fragment tended to exhibit very early leaf senescence (Figure 1D and Table S1), as did the 1,639 varieties with absence of the “InDel II” fragment. Thus, our results indicated that HDA710 possesses natural genotypic variation between indica-related and japonica-related accessions, which was significantly associated with leaf senescence.

Generation of Transgenic Rice Lines Reveals HDA710 as a Negative Regulator of Leaf Senescence

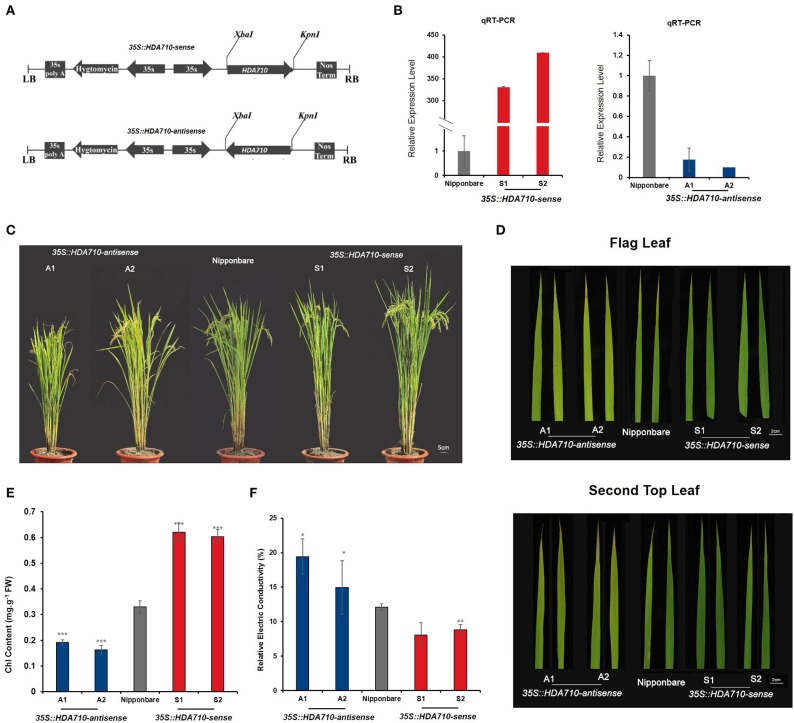

Correlation analysis between genotypes and phenotypes of various accessions revealed that the deletion in HDA710 might activate the early leaf senescence process. We used an antisense and sense transgenic approach to characterize the function of the HDA710 gene in rice plants. The cloned full-length coding sequence (CDS) of HDA710 was used to generate transgenic rice lines with Oryza sativa ssp. japonica cv. Nipponbare as the wild-type (WT) background. Down-regulation of HDA710 was achieved by an antisense approach (Figure 2A) and over-expression by a sense approach (Figure 2A) under control of the 35S promoter.

Figure 2.

Phenotypic observation of leaf senescence at the late developmental growth stage in HDA710 transgenic plants and controls. (A) Vectors 35S:HDA710-sense and 35S:HDA710-antisense. (B) qRT-PCR validation of relative HDA710 expression levels in 35S:HDA710-antisense, Nipponbare, and 35S:HDA710-sense plants. Data are means ± SD (n = 3). (C) Whole plants of 35S:HDA710-antisense, Nipponbare, and 35S:HDA710-sense taken from the field at about 104 days. Bar = 5 cm. (D) Mature leaf before harvest in 35S:HDA710-antisense, Nipponbare, and 35S:HDA710-sense. Bar = 2 cm. (E) Chlorophyll content of second top leaves of 35S::HDA710-antisense, Nipponbare, and 35S::HDA710-sense plants. We performed six biological replicates, each of which was derived from three leaves in three individual plants. (F) Relative electrical conductivity in flag leaves at about 114 days. We performed four biological replicates, each of which was derived from four leaves in four individual plants. One-way ANOVA results for genotypic variation comparisons in (E,F) are given in Table S3. The error bars in (B,E,F) represent the standard error of replicates. The asterisks represent the significant difference between Nipponbare, 35S::HDA710-antisense, and 35S::HDA710-sense (*P < 0.05; **P < 0.01; ***P < 0.001).

We determined expression levels of HDA710 in Nipponbare (WT) and transgenic rice lines by quantitative reverse-transcription PCR (qRT-PCR) using specific primers for 35S::HDA710-antisense and -sense transgenic lines. Relative expression levels of HDA710 were significantly down-regulated in the 35S::HDA710-antisense lines and significantly higher than those in Nipponbare in the 35S::HDA710-sense lines (Figure 2B).

To further explore the relationship between HDA710 expression levels and histone deacetylation activity, we performed immunoblotting with specific antibodies. We detected acetylation of histone H3 at lysine 9 and 27 (H3K9ac and H3K27ac) in 35S::HDA710-antisense and -sense transgenic lines, japonica rice Nipponbare. As shown in Figure S2, the two antisense lines had higher levels of H3K9ac and H3K27ac than Nipponbare and the 35S::HDA710-sense lines.

To investigate leaf senescence during plant growth stages, 35S::HDA710-sense, 35S::HDA710-antisense, and Nipponbare (WT) plants were planted in paddy fields. Leaf yellowing is a convenient visible characteristic of leaf senescence, mainly reflecting the chloroplast senescence of mesophyll cells and chlorophyll loss (Oh et al., 1997). We investigated leaf senescence in whole plants, observing that the over-expression lines stayed green compared with the knock-down lines and Nipponbare (Figure 2C). 35S::HDA710-antisense lines showed earlier senescence than Nipponbare in the flag leaves and second top leaves; in contrast, leaves of 35S::HDA710-sense lines stayed green (Figure 2D). The second top leaves of over-expression lines had a higher chlorophyll content than those of Nipponbare, while leaves of the knock-down lines showed a slightly lower chlorophyll content (Figure 2E and Table S3). We also measured relative electrical conductivity, another senescence-related indicator. When leaves grow older, membranes become fragile, and electrolytes leak out of cells (Chen et al., 2015). Ion leakage was higher in 35S::HDA710-antisense lines than in 35S::HDA710-sense lines or Nipponbare (Figure 2F and Table S3).

To investigate the specific time of leaf senescence during plant growth, we tested 35S::HDA710-sense lines, 35S::HDA710-antisense lines, and Nipponbare (WT) plants at different stages (Figure S3). In the field, we used the SPAD-502 chlorophyll meter to measure the chlorophyll content in six time points (from 75d to 118d after planting). Each time point we took more than 10 leaves from individual plants. We started to examine chlorophyll content at 75 days after planting, and all results showed decreasing chlorophyll content over time (Figure S3). The knock-down 35S::HDA710-antisense lines had a relatively lower chlorophyll content than Nipponbare; while, the over-expression 35S::HDA710-sense lines showed a relatively higher chlorophyll content than the WT, especially after 100 days (Figure S3).

We also measured chlorophyll content in the leaf tip, leaf center and leaf base of japonica rice Nipponbare and indica accessions 9311 and Teqing (TQ). Nipponbare had a higher chlorophyll content than 9311 or TQ, suggesting that japonica indeed shows a late leaf senescence phenotype (Figures S4A,B). The indica 9311 and TQ accessions also tended to have higher relative electrical conductivity (Figure S4C).

RNA-Seq Based Transcriptome Analysis of HDA710 Transgenic Lines and Nipponbare

To explore the mechanism of HDA710 regulation of leaf senescence, we applied a transcriptomic strategy using RNA-Seq to investigate differences in whole-genome gene expression among 35S::HDA710-sense, Nipponbare, and 35S::HDA710-antisense. We used flag leaves of these lines with three independent biological replicates for sequencing. All RNA-Seq reads were aligned to the rice genome version MSU6.1 using Tophat (Kim et al., 2013), with alignment rates for all the samples at around 90% (Table S4). Using Cufflinks, we identified differentially expressed genes between 35S::HDA710-sense and 35S::HDA710-antisense with a cut-off value fold change ≥1.7 and q-value ≤0.05. We identified 2,809 differentially expressed genes, including 1,664 significantly up-regulated genes in 35S::HDA710-sense and 1,145 significantly down-regulated genes in 35S::HDA710-sense compared with 35S::HDA710-antisense, respectively (Figure S5A).

In addition to the differentially expressed genes between antisense and sense lines, we also calculated the differentially expressed genes (DEGs) of 35S::HDA710-sense vs. Nipponbare and 35S::HDA710-antisense vs. Nipponbare. The detail numbers about up- and down- regulated genes were shown in Figure S5A. In the meanwhile, we performed SEACOMPARE analysis using agriGO webserver and the results showed that, the GO terms such as “photosynthesis” and “chlorophyll biosynthetic” were significantly enriched in the genes up-regulated in both Nipponbare and 35S::HDA710-sense line compared to 35S::HDA710-antisense; while the GO terms such as “programmed cell death,” “apoptosis” and “response to stress” were enriched in the genes down-regulated in the 35S::HDA710-sense line compared to Nipponbare and 35S::HDA710-antisense (Figure S5B).

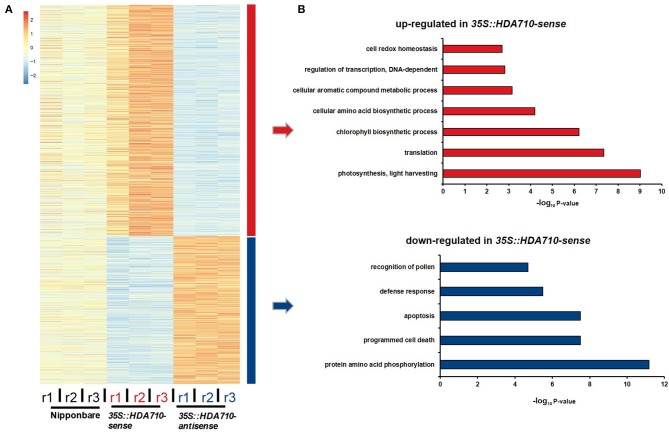

To identify co-expressed genes with similar expression patterns in transgenic and Nipponbare plants, we employed the hierarchical method to cluster the 2,809 differentially expressed genes between 35S::HDA710-antisense and 35S::HDA710-sense. From the heat map representing relative expression level of each gene across the nine samples, these genes were obviously clustered into two groups, one representing genes with higher expression in 35S::HDA710-sense plants and another representing genes with higher expression in 35S::HDA710-antisense plants (Figure 3A).

Figure 3.

RNA-Seq analysis of 35S::HDA710-antisense and 35S::HDA710-sense. (A) Heatmap showing relative expression levels of differentially expressed genes in different replicates of each sample. (B) GO term enrichment analysis corresponding to the up-regulated and down-regulated genes in (A).

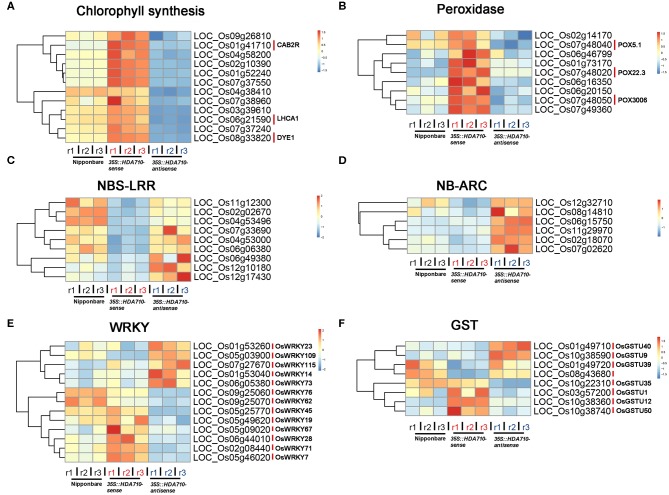

We conducted gene GO enrichment analysis for these differentially expressed genes in 35S::HDA710-sense vs. 35S::HDA710-antisense. For genes up-regulated in 35S::HDA710-sense, the GO terms “photosynthesis, light harvesting” and “chlorophyll biosynthetic process” were significantly enriched (Figure 3B). Twelve genes related to chlorophyll biosynthesis were highly expressed in 35S::HDA710-sense compared to Nipponbare and 35S::HDA710-antisense (Figure 4A and Table S5). The GO term “cell redox homeostasis” was also enriched (Figure 3B). Reactive oxygen species (ROS) are important in early leaf senescence (Allu et al., 2014); therefore, we investigated the differentially expressed peroxidase genes and found that nine of them were preferentially expressed in the 35S::HDA710-sense line (Figure 4B and Table S5). Among down-regulated genes in 35S::HDA710-sense, the GO terms “cell death,” “apoptosis,” and “defense response” were significantly enriched (Figure 3B). This indicates that leaf senescence is accompanied by cell death and triggers the expression of some defense response genes. Nucleotide-binding site leucine-rich repeat (NBS-LRR) proteins are involved in the detection of diverse pathogens, including bacteria, viruses, fungi, nematodes, insects, and oomycetes (McHale et al., 2006). The NB-ARC domain is a functional ATPase domain, and its nucleotide-binding state is proposed to regulate activity of the R protein (van Ooijen et al., 2008). Interestingly, these two kinds of R genes were both up-regulated in 35S::HDA710-antisense (Figures 4C,D and Table S5).

Figure 4.

Expression patterns of gene superfamilies in Nipponbare, 35S::HDA710-sense, and 35S::HDA710-antisense. Genes derived from Chlorophyll biosynthesis (A), Peroxidase (B), NBS-LRR (C), NB-ARC (D), WRKY (E), and GST (F) families. Red indicates a higher expression level, whereas blue indicates a lower expression level.

We also conducted gene set enrichment analysis (GSEA) through literature mining, which showed that the 2,809 differentially expressed genes were significantly enriched in the “BTH (benzothiadiazole)-inducible and WRKY45-dependent” gene set (Nakayama et al., 2013), with p-value = 5.8e−16 (Figure S6). Among the reported 277 BTH-inducible and WRKY45-dependent rice genes, there were 51 differentially expressed genes (28 up-regulated and 23 down-regulated genes in 35S::HDA710-sense vs. 35S::HDA710-antisense), including WRKYs, HDA710, and glutathione S-transferase (GST) genes (Figure S6). The GST gene family encodes genes critical for certain life processes and mechanisms of detoxification and toxicity (Nebert and Vasiliou, 2004). We also mined data from the expression profiles of the differentially expressed WRKY and GST family genes (Figures 4E,F and Table S5). WRKY and GST family genes showed some similar expression patterns, and both of them were regulated by HDA710. For example, OsWRKY45 and OsWRKY62 as well as OsGSTU1, OsGSTU12, OsGSTU35, and OsGSTU50 were up-regulated in the 35S::HDA710-sense lines (Figures 4E,F and Table S5). Interestingly, these WRKY and GST genes were also included in the list of 277 BTH-inducible and WRKY45-dependent rice genes (Figure S6).

Co-expression Network of HDA710 Reveals Synergistic Roles of HDA710 and OsGSTU12 in Regulating Leaf Senescence

Construction of a co-expression gene network is an efficient method for determining linkages between genes in a biological process. We acquired the top 300 genes positively co-expressed with HDA710 from RiceFREND (Table S6), a gene co-expression database in rice (Sato et al., 2013), and further found that GST family genes were enriched in GSEA analysis of these genes using the PlantGSEA platform (Yi et al., 2013). This suggested that GST genes might be induced in the same pathways or by similar factors as HDA710. We focused on the differentially expressed genes in 35S::HDA710-sense vs. 35S::HDA710-antisense RNA-Seq profiles as candidates to test whether GST genes share a common function with HDA710. Eleven genes overlapped with the top 300 co-expressed genes of HDA710 up-regulated in 35S::HDA710-sense RNA-Seq profiles; four of these were also up-regulated in japonica Nipponbare compared with indica 9311 from microarray data (Liu et al., 2010), including OsGSTU12 (LOC_Os10g38360), LOC_Os01g67860, LOC_Os01g15270, and LOC_Os10g02380 (Table S6). Thus, these four key candidates potentially play a similar role in various biological pathways and/or metabolic processes, especially leaf senescence.

To further analyze the genetic diversity of the four genes, we identified InDels in the promoter region of the OsGSTU12 gene in 3,010 accessions from different rice subspecies using the RPAN database (Figure S7). We found a deletion of around 1 kb in the promoter region of OsGSTU12 in majority of indica accessions compared with japonica accessions. InDels in the promoter region of OsGSTU12 and in the gene region of HDA710 occurred coincidentally among more than 90% of the 3,010 rice accessions (Table S1). Interestingly, OsGSTU12 and HDA710 are both induced by OsWRKY45 (Nakayama et al., 2013) (Figure S6), suggesting that OsGSTU12 and HDA710 are both regulated by OsWRKY45. As the OsWRKY45 transcription factor regulates genes through W-box motifs (Nakayama et al., 2013; Fukushima et al., 2016), we investigated W-box motifs in the promoter region of OsGSTU12. We identified 21 W-box motifs in the promoter region of OsGSTU12, especially in the InDel region (Figure S7). We also searched for genes co-expressed with HDA710 and OsGSTU12, and constructed a co-expression gene network with different expression views (Figure 5). Five genes co-expressed with HDA710, including OsGSTU12, were up-regulated in 35S::HDA710-sense lines, and meanwhile six genes co-expressed with OsGSTU12 were also up-regulated in 35S::HDA710-sense lines compared with 35S::HDA710-antisense lines. Furthermore, HDA710 together with nine co-expressed genes, including OsGSTU12, were up-regulated in japonica rice Nipponbare vs. indica rice 9311. Additionally, OsGSTU12 and 14 co-expressed genes showed higher expression levels in Nipponbare than in 9311. Consistency in sequence variations and co-expression networks between HDA710 and OsGSTU12 implied common involvement in some subspecies-specific biological pathways. Our results suggest that HDA710 and OsGSTU12 possibly work synergistically in the regulation of leaf senescence.

Figure 5.

Co-expression network of HDA710 combined with transcriptome data reveals a close link with OsGSTU12. The network is constructed from RiceFREND using Cytoscape software. Nodes in light pink represent genes up-regulated in 35S::HDA710-sense vs. 35S::HDA710-antisense, while nodes in light blue represent genes down-regulated in 35S::HDA710-sense vs. 35S::HDA710-antisense. Nodes with light pink borders represent genes up-regulated in japonica Nipponbare vs. indica 9311, while nodes with light blue borders represent genes down-regulated in japonica Nipponbare vs. indica 9311. Lines between nodes represent positive co-expression relationships.

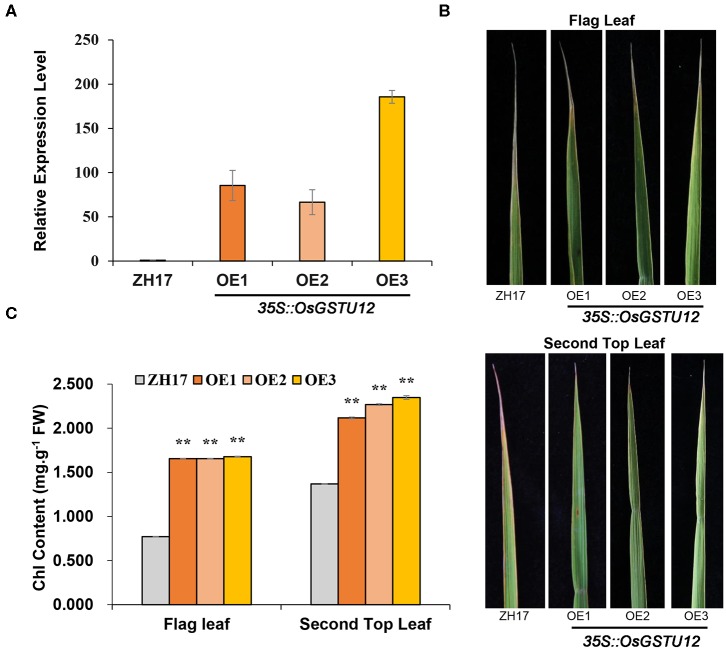

Over-Expression of OsGSTU12 in Rice Delays Leaf Senescence

Since OsGSTU12 is highly expressed in japonica rice, similar to HDA710, and was co-expressed with HDA710 during HDA710-mediated leaf senescence (Figure 5), we over-expressed OsGSTU12 in rice cultivar Zhonghua17 to determine whether over-expression of OsGSTU12 could prolong the natural aging of rice. Three over-expression transgenic lines (OE1, OE2, OE3) showing higher relative OsGSTU12 expression levels than wild-type Zhonghua17 were observed in the field at the grain-filling stage (Figure 6A). As shown in Figure 6B, the top parts of flag leaves and second top leaves of Zhonghua17 had begun to yellow and whither, but those of over-expression lines retained considerably more green parts. Further chlorophyll content analysis showed that the flag leaves and second top leaves of over-expression lines had significantly higher chlorophyll content compared to that of Zhonghua17 (Figure 6C), suggesting that over-expression of OsGSTU12 could delay the natural leaf senescence of rice at the late developmental growth stage.

Figure 6.

Comparative analysis of transgenic lines over-expressing OsGSTU12 with controls at the late developmental growth stage in the field. (A) Relative expression levels of OsGSTU12 in the wild type (ZH17) and OsGSTU12 over-expression transgenic lines (OE1, OE2, OE3). Data are means ± SD (n = 3). (B) Flag leaf and second top leaf in wild-type and over-expression lines. (C) Chlorophyll content of flag leaf and second top leaf from top. Data are means ± SD (n = 4). **P < 0.01; Student's t-test.

Discussion

HDA710 Shows Natural Variation Between Oryza sativa ssp. japonica and indica

Natural variation reflects sequence differences introduced during long-term evolution of species due to various environmental factors, resulting in phenotypic differences. Although the genome-wide association study (GWAS) approach is popular for mining important agronomic traits in crops, it remains a slow process. Previous studies have reported differences in the sequence and gene expression of HDA710 in indica and japonica rice (Liu et al., 2010). Our qRT-PCR experiment also demonstrated higher expression levels of this gene in Nipponbare than in the indica accession 9311. Examination of gene sequence differences in representatives of different subspecies in the RPAN database revealed that HDA710 was japonica-dominant, with two fragments absent mainly in indica rice accessions, namely “InDel I” and “InDel II” regions. Differences in genotype are often an important factor leading to phenotypic differences, so the absence of these two fragments may be responsible for differences in the traits of japonica and indica rice. By comparing genotypes and phenotypes, we found that accessions with missing fragments were more inclined to early senescence of leaves. The indica rice accessions showed a yellowing phenotype and lower chlorophyll content than japonica accessions. Since most of the accessions with missing HDA710 fragments belonged to the indica subspecies, whereas the sequence of this gene was relatively complete in japonica rice, HDA710 represents an important marker for indica and japonica differentiation. In summary, we suggest that the natural variation of HDA710 may be key for leaf senescence traits. As it is present in only 1% indica accessions, it may have great potential for introduction into other indica rice accessions.

HDA710 May Regulate Leaf Senescence Through Programmed Cell Death and Free Radical Reaction

Leaf senescence is a complex trait involved in various biological processes, including degradation of chloroplasts, degradation of nucleic acids and proteins, and recycling of nutrients (Zeng et al., 2018). Early leaf senescence has a negative effect on rice yield and quality; therefore, it is of great importance to explore the hidden molecular mechanisms.

Transcriptome data analysis indicated that HDA710 regulates many genes associated with leaf senescence. When HDA710 gene expression was up-regulated, it activated genes related to chlorophyll biosynthesis, photosynthesis, and light harvesting. We analyzed some key gene families and found high expression levels of many chlorophyll biosynthesis related genes in HDA710 over-expression lines showing late leaf senescence, which directly affected the color of leaves. Conversely, down-regulation of HDA710 gene expression induced expression of defense responses and apoptosis-related genes, with some GO terms related to cell death significantly enriched. Genes related to these GO terms mostly belonged to NBS-LRR and NB-ARC families, reported to be mainly involved in diseases resistance. Cell death and disease resistance are closely linked in plants. In fact, cell death occurring in leaf senescence is a type of programmed cell death (PCD) controlled by many active genetic programs (Cao et al., 2003). Pathogenesis-related (PR) proteins are involved in PCD, and many PR genes are induced during leaf senescence in plants (Quirino et al., 1999, 2000). There is already ample evidence suggesting that cell death reinforces or stimulates the induction of plant defense processes (Shirasu and Schulze-Lefert, 2000). In addition, up-regulation of HDA710 expression induces high expression levels of some peroxidases that inhibit free radical production. Scavenging of free radicals blocks the activity of reactive oxygen species, thereby protecting cells and tissues from oxidative damage, which plays an important role in delaying leaf senescence.

Studies have shown that leaf senescence may be caused by the destruction of chloroplasts, leading to a decrease in metabolic rate and thereby reducing the effects of oxidative stress (Woo et al., 2002). Production of ROS is one of the earliest reactions of plant cells under abiotic stress and senescence processes (Khanna-Chopra, 2012). In Arabidopsis, PCD, developmental senescence, and resistance response are connected through complicated genetic controls influenced by redox regulation (Pavet et al., 2005). We analyzed MV-treatment microarray data and found that HDA710 and OsGSTU12 might be involved in the response to oxidative stress (Liu et al., 2010). This suggests that HDA710 may play a role in regulating leaf senescence by scavenging free radicals together with OsGSTU12. In order to verify the differential expression of HDA710 between the two rice genotypes and whether it is capable of responding to oxidative stress, we treated Nipponbare and 9311 with MV for 6 and 24 h. qRT-PCR showed higher expression levels of HDA710 in Nipponbare than in 9311, which were significantly induced after MV treatment (Figure S8). We demonstrated here that HDA710 is involved in cell death, PR, and oxidative stress during leaf senescence.

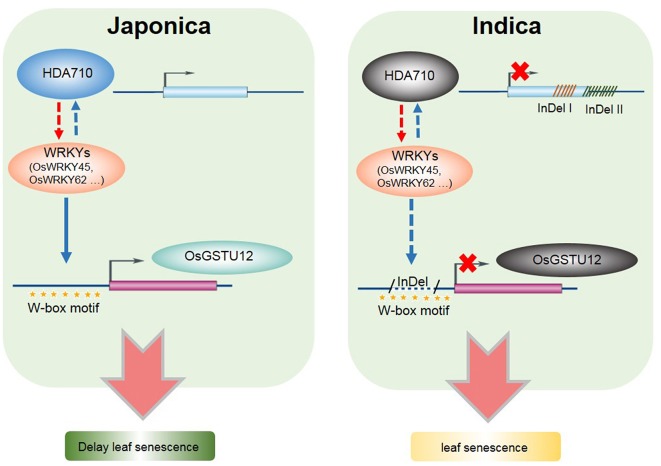

HDA710 and OsGSTU12 Exhibit Possible Co-regulatory Mechanisms and May Work Synergistically in Regulating Leaf Senescence in Rice

Most agronomic traits are regulated by multiple genes and various pathways (Rao et al., 2014). Co-expressed genes are those with similar trends of gene expression in the same tissue or under the same stress treatment conditions, and these genes usually participate in a defined biological process. Induction or suppression of HDA710 resulted in differential expression of a large number of genes, some showing strong co-expression relationships, suggesting that these genes may take part in the same molecular process of regulating leaf senescence. One of the key genes, OsGSTU12, was up-regulated in 35S::HDA710-sense lines vs. 35S::HDA710-antisense lines and positively regulated by HDA710. Expression of OsGSTU12 was higher in japonica rice Nipponbare compared to indica rice 9311. Most of the genes co-expressed with OsGSTU12 were up-regulated in Nipponbare, suggesting that OsGSTU12 and its co-expressed genes might be similarly affected by changes in the expression of HDA710, possibly working in coordination with HDA710 in delaying rice leaf senescence. Consistent with the co-expression network analyses, we indeed found that over-expression of OsGSTU12 could delay the process of leaf senescence (Figure 6).

In addition, the promoter region of OsGSTU12 shows natural variation between the indica and japonica rice subspecies. Coincidentally, the presence/absence variation (PAVs) of OsGSTU12 was consistent with that of HDA710 in more than 90% of 3,010 rice accessions (Table S1), hinting that HDA710 and OsGSTU12 had a co-evolutionary relationship during the divergence of rice subspecies.

We propose a model in which HDA710 works synergistically with OsGSTU12 in regulating the process of leaf senescence in rice (Figure 7). Both HDA710 and OsGSTU12 may be regulated by specific OsWRKYs (such as OsWRKY45 and OsWRKY62), which are in turn induced by over-expression of the HDA710 gene. These two genes exhibit InDels between indica and japonica rice accessions. In japonica rice, HDA710 promotes expression of these OsWRKYs, which further bind to the W-box motif of OsGSTU12, thereby activating expression of OsGSTU12 and delaying leaf senescence; in indica rice, the HDA710 gene has fragment deletions in the gene region, and HDA710 expression is inhibited, thereby down-regulating expression of these OsWRKYs. Furthermore, in indica rice, deletion of the promoter region of OsGSTU12 may affect binding of OsWRKYs to the W-box motif, thereby preventing OsGSTU12 from being activated and leading to early leaf senescence. This may partially elucidate the molecular mechanism of earlier leaf senescence in indica rice accessions compared to japonica rice accessions. The specific relationships among HDA710, OsWRKYs, and OsGSTU12 need to be further explored, and proteins interacting with HDA710 as well as its downstream target genes should also be further analyzed.

Figure 7.

Model of HDA710 working synergistically with OsGSTU12 in regulating the process of leaf senescence in rice. Here presented a pathway of regulating leaf senescence in indica and japonica rice. The red arrow represents the HDA710 gene could regulate the expression of WRKYs through the RNA-Seq data, while the blue arrow represents the WRKYs could regulate the expression of HDA710 and OsGSTU12 though the published data. In indica rice, the gray oval which represent the gene HDA710 and OsGSTU12 means that these two genes are down-regulated compared to japonica rice, and both of these two genes showed deletions. In japonica rice, there are W-box binding sites, while in indica rice, there are deletions which cover partial W-box binding sites.

Conclusion

In summary, we systematically studied the association of HDA710 with leaf senescence in rice. We surveyed the gene presence frequency of all rice HDAC genes in 3,010 rice accessions, determining that deletions of fragments of HDA710 are significantly involved in the process of leaf senescence. Further transgenic results validated that HDA710 represses leaf senescence in rice. We also conducted RNA-Seq analysis of the transgenic lines to elucidate the possible regulation mechanism and further constructed a co-expression network for HDA710, which revealed that the GST gene OsGSTU12 is co-expressed and possibly co-evolved with HDA710 for regulating leaf senescence in rice. Further transgenic analysis showed that over-expression of OsGSTU12 also delayed leaf senescence in rice. We expect that epigenetic and genetic variation in diverse accessions will provide valuable resources for improving important agronomic traits, and widen sources of phenotypic variation in crops. The association of histone deacetylase HDA710 with leaf senescence in rice will provide a novel direction for promoting the application of epigenetic and genetic variation together with co-expression networks in crop breeding.

Data Availability Statement

The datasets generated for this study can be found in the http://bioinformatics.cau.edu.cn/HDA710_RNA-seq/.

Author Contributions

WX, ZS, and FL: conceived and designed the experiments. NZ, MS, JZ, WX, QW, QS, KZ, and FL: performed the experiments. NZ, XM, WX, ZS, CS, and FL: analyzed the data. XM and ZS: contributed bioinformatics platform and analysis tools. WX, NZ, JZ, XM, FL, and ZS: wrote the paper.

Conflict of Interest

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Acknowledgments

We thank Qunlian Zhang for rice breeding and Hong Yan for experiment support.

Footnotes

Funding. This work was supported by grants from the National Natural Science Foundation of China (31771467, 31671647, and 31970629).

Supplementary Material

The Supplementary Material for this article can be found online at: https://www.frontiersin.org/articles/10.3389/fbioe.2020.00471/full#supplementary-material

References

- Abdelkhalik A. F., Shishido R., Nomura K., Ikehashi H. (2005). QTL-based analysis of leaf senescence in an indica/japonica hybrid in rice (Oryza sativa L.). Theor. Appl. Genet. 110, 1226–1235. 10.1007/s00122-005-1955-2 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Alexandrov N., Tai S., Wang W., Mansueto L., Palis K., Fuentes R. R., et al. (2015). SNP-Seek database of SNPs derived from 3000 rice genomes. Nucleic Acids Res. 43(Database issue), D1023–D1027. 10.1093/nar/gku1039 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Allu A. D., Soja A. M., Wu A., Szymanski J., Balazadeh S. (2014). Salt stress and senescence: identification of cross-talk regulatory components. J. Exp. Bot. 65, 3993–4008. 10.1093/jxb/eru173 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bourque S., Dutartre A., Hammoudi V., Blanc S., Dahan J., Jeandroz S., et al. (2011). Type-2 histone deacetylases as new regulators of elicitor-induced cell death in plants. N. Phytol. 192, 127–139. 10.1111/j.1469-8137.2011.03788.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cao J., Jiang F., Cui K. M. (2003). Time-course of programmed cell death during leaf senescence in Eucommia ulmoides. J. Plant Res. 116, 7–12. 10.1007/s10265-002-0063-5 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen C., Song X., Ma S., Wang X., Xu J., Zhang H., et al. (2015). Cdc42 inhibitor ML141 enhances G-CSF-induced hematopoietic stem and progenitor cell mobilization. Int. J. Hematol. 101, 5–12. 10.1007/s12185-014-1690-z [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen L. T., Wu K. (2010). Role of histone deacetylases HDA6 and HDA19 in ABA and abiotic stress response. Plant Signal Behav. 5, 1318–1320. 10.4161/psb.5.10.13168 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen Z. J., Tian L. (2007). Roles of dynamic and reversible histone acetylation in plant development and polyploidy. Biochim Biophys. Acta 1769, 295–307. 10.1016/j.bbaexp.2007.04.007 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chung P. J., Kim Y. S., Jeong J. S., Park S. H., Nahm B. H., Kim J. K. (2009). The histone deacetylase OsHDAC1 epigenetically regulates the OsNAC6 gene that controls seedling root growth in rice. Plant J. 59, 764–776. 10.1111/j.1365-313X.2009.03908.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dang W., Steffen K. K., Perry R., Dorsey J. A., Johnson F. B., Shilatifard A., et al. (2009). Histone H4 lysine 16 acetylation regulates cellular lifespan. Nature 459, 802–807. 10.1038/nature08085 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Duan P. G., Xu J. S., Zeng D. L., Zhang B. L., Geng M. F., Zhang G. Z., et al. (2017). Natural variation in the promoter of GSE5 contributes to grain size diversity in rice. Mol. Plant 10, 685–694. 10.1016/j.molp.2017.03.009 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Feser J., Truong D., Das C., Carson J. J., Kieft J., Harkness T., et al. (2010). Elevated histone expression promotes life span extension. Mol Cell 39, 724–735. 10.1016/j.molcel.2010.08.015 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fukushima S., Mori M., Sugano S., Takatsuji H. (2016). Transcription Factor WRKY62 plays a role in pathogen defense and hypoxia-responsive gene expression in rice. Plant Cell Physiol. 57, 2541–2551. 10.1093/pcp/pcw185 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hollender C., Liu Z. C. (2008). Histone deacetylase genes in Arabidopsis development. J. Integrat. Plant Biol. 50, 875–885. 10.1111/j.1744-7909.2008.00704.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hu Y., Qin F., Huang L., Sun Q., Li C., Zhao Y., et al. (2009). Rice histone deacetylase genes display specific expression patterns and developmental functions. Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 388, 266–271. 10.1016/j.bbrc.2009.07.162 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hu Y., Zhang L., Zhao L., Li J., He S. B., Zhou K., et al. (2011). Trichostatin a selectively suppresses the cold-induced transcription of the ZmDREB1 gene in Maize. PLoS ONE 6:22132. 10.1371/journal.pone.0022132 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Huang J. C., Yan L. Y., Lei Z. L., Miao Y. L., Shi L. H., Yang J. W., et al. (2007). Changes in histone acetylation during postovulatory aging of mouse oocyte. Biol. Reprod. 77, 666–670. 10.1095/biolreprod.107.062703 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Huang L., Sun Q., Qin F., Li C., Zhao Y., Zhou D. X. (2007). Down-regulation of a SILENT INFORMATION REGULATOR2-related histone deacetylase gene, OsSRT1, induces DNA fragmentation and cell death in rice. Plant Physiol. 144, 1508–1519. 10.1104/pp.107.099473 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Huang X. Z., Qian Q., Liu Z. B., Sun H. Y., He S. Y., Luo D., et al. (2009). Natural variation at the DEP1 locus enhances grain yield in rice. Nat. Genet. 41, 494–497. 10.1038/ng.352 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jain M., Nijhawan A., Arora R., Agarwal P., Ray S., Sharma P., et al. (2007). F-box proteins in rice. Genome-wide analysis, classification, temporal and spatial gene expression during panicle and seed development, and regulation by light and abiotic stress. Plant Physiol. 143, 1467–1483. 10.1104/pp.106.091900 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jang I. C., Pahk Y. M., Song S. I., Kwon H. J., Nahm B. H., Kim J. K. (2003). Structure and expression of the rice class-I type histone deacetylase genes OsHDAC1–3: OsHDAC1 overexpression in transgenic plants leads to increased growth rate and altered architecture. Plant J. 33, 531–541. 10.1046/j.1365-313X.2003.01650.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jung K. H., Gho H. J., Giong H. K., Chandran A. K., Nguyen Q. N., Choi H., et al. (2013). Genome-wide identification and analysis of Japonica and Indica cultivar-preferred transcripts in rice using 983 Affymetrix array data. Rice 6:19. 10.1186/1939-8433-6-19 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jyothishwaran G., Kotresha D., Selvaraj T., Srideshikan S. M., Rajvanshi P. K., Jayabaskaran C. (2007). A modified freeze-thaw method for efficient transformation of Agrobacterium tumefaciens. Curr. Sci. 93, 770–772. [Google Scholar]

- Khanna-Chopra R. (2012). Leaf senescence and abiotic stresses share reactive oxygen species-mediated chloroplast degradation. Protoplasma 249, 469–481. 10.1007/s00709-011-0308-z [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kim D., Pertea G., Trapnell C., Pimentel H., Kelley R., Salzberg S. L. (2013). TopHat2: accurate alignment of transcriptomes in the presence of insertions, deletions and gene fusions. Genome Biol. 14:R36. 10.1186/gb-2013-14-4-r36 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lawrence T. (2009). The nuclear factor NF-kappaB pathway in inflammation. Cold Spring Harb Perspect Biol. 1:a001651. 10.1101/cshperspect.a001651 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li C., Huang L., Xu C., Zhao Y., Zhou D. X. (2011). Altered levels of histone deacetylase OsHDT1 affect differential gene expression patterns in hybrid rice. PLoS ONE 6:e21789. 10.1371/journal.pone.0021789 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li J. Y., Wang J., Zeigler R. S. (2014). The 3,000 rice genomes project: new opportunities and challenges for future rice research. Gigascience 3:8. 10.1186/2047-217X-3-8 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li Y. B., Fan C. C., Xing Y. Z., Jiang Y. H., Luo L. J., Sun L., et al. (2011). Natural variation in GS5 plays an important role in regulating grain size and yield in rice. Nat. Genet. 43, 1266–1267. 10.1038/ng.977 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liu F., Xu W., Wei Q., Zhang Z., Xing Z., Tan L., et al. (2010). Gene expression profiles deciphering rice phenotypic variation between Nipponbare (Japonica) and 93–11 (Indica) during oxidative stress. PLoS ONE 5:e8632. 10.1371/journal.pone.0008632 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Livak K. J., Schmittgen T. D. (2001). Analysis of relative gene expression data using real-time quantitative PCR and the 2(−ΔΔC(T)) Method. Methods 25, 402–408. 10.1006/meth.2001.1262 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Luo M., Cheng K., Xu Y., Yang S., Wu K. (2017). Plant responses to abiotic stress regulated by histone deacetylases. Front. Plant Sci. 8:2147. 10.3389/fpls.2017.02147 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Luo M., Wang Y. Y., Liu X. C., Yang S. G., Lu Q., Cui Y. H., et al. (2012). HD2C interacts with HDA6 and is involved in ABA and salt stress response in Arabidopsis. J. Exp. Botany 63, 3297–3306. 10.1093/jxb/ers059 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mansueto L., Fuentes R. R., Borja F. N., Detras J., Abriol-Santos J. M., Chebotarov D., et al. (2017). Rice SNP-seek database update: new SNPs, indels, and queries. Nucleic Acids Res. 45, D1075–D1081. 10.1093/nar/gkw1135 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McHale L., Tan X., Koehl P., Michelmore R. W. (2006). Plant NBS-LRR proteins: adaptable guards. Genome Biol. 7:212. 10.1186/gb-2006-7-4-212 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nakayama A., Fukushima S., Goto S., Matsushita A., Shimono M., Sugano S., et al. (2013). Genome-wide identification of WRKY45-regulated genes that mediate benzothiadiazole-induced defense responses in rice. BMC Plant Biol. 13:150. 10.1186/1471-2229-13-150 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nebert D. W., Vasiliou V. (2004). Analysis of the glutathione S-transferase (GST) gene family. Hum. Genom. 1, 460–464. 10.1186/1479-7364-1-6-460 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nelissen H., Fleury D., Bruno L., Robles P., De Veylder L., Traas J., et al. (2005). The elongata mutants identify a functional Elongator complex in plants with a role in cell proliferation during organ growth. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 102, 7754–7759. 10.1073/pnas.0502600102 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ogiso-Tanaka E., Matsubara K., Yamamoto S., Nonoue Y., Wu J. Z., Fujisawa H., et al. (2013). Natural variation of the RICE FLOWERING LOCUS T 1 contributes to flowering time divergence in rice. PLoS ONE 8:75959. 10.1371/journal.pone.0075959 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Oh S. A., Park J. H., Lee G. I., Paek K. H., Park S. K., Nam H. G. (1997). Identification of three genetic loci controlling leaf senescence in Arabidopsis thaliana. Plant J. 12, 527–535. 10.1111/j.0960-7412.1997.00527.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- O'Sullivan R. J., Kubicek S., Schreiber S. L., Karlseder J. (2010). Reduced histone biosynthesis and chromatin changes arising from a damage signal at telomeres. Nat. Struct. Mol. Biol. 17, 1218–1225. 10.1038/nsmb.1897 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pandey R., Muller A., Napoli C. A., Selinger D. A., Pikaard C. S., Richards E. J., et al. (2002). Analysis of histone acetyltransferase and histone deacetylase families of Arabidopsis thaliana suggests functional diversification of chromatin modification among multicellular eukaryotes. Nucleic Acids Res. 30, 5036–5055. 10.1093/nar/gkf660 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pavet V., Olmos E., Kiddle G., Mowla S., Kumar S., Antoniw J., et al. (2005). Ascorbic acid deficiency activates cell death and disease resistance responses in Arabidopsis. Plant Physiol. 139, 1291–1303. 10.1104/pp.105.067686 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Quirino B. F., Noh Y. S., Himelblau E., Amasino R. M. (2000). Molecular aspects of leaf senescence. Trends Plant Sci. 5, 278–282. 10.1016/S1360-1385(00)01655-1 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Quirino B. F., Normanly J., Amasino R. M. (1999). Diverse range of gene activity during Arabidopsis thaliana leaf senescence includes pathogen-independent induction of defense-related genes. Plant Mol. Biol. 40, 267–278. 10.1023/A:1006199932265 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rao Y., Li Y., Qian Q. (2014). Recent progress on molecular breeding of rice in China. Plant Cell Rep. 33, 551–564. 10.1007/s00299-013-1551-x [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sato Y., Namiki N., Takehisa H., Kamatsuki K., Minami H., Ikawa H., et al. (2013). RiceFREND: a platform for retrieving coexpressed gene networks in rice. Nucleic Acids Res 41(Database issue), D1214–D1221. 10.1093/nar/gks1122 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schmid M., Davison T. S., Henz S. R., Pape U. J., Demar M., Vingron M., et al. (2005). A gene expression map of Arabidopsis thaliana development. Nat. Genet. 37, 501–506. 10.1038/ng1543 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shirasu K., Schulze-Lefert P. (2000). Regulators of cell death in disease resistance. Plant Mol. Biol. 44, 371–385. 10.1023/A:1026552827716 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sidler C., Kovalchuk O., Kovalchuk I. (2017). Epigenetic regulation of cellular senescence and aging. Front. Genet. 8:138. 10.3389/fgene.2017.00138 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sridha S., Wu K. Q. (2006). Identification of AtHD2C as a novel regulator of abscisic acid responses in Arabidopsis. Plant J. 46, 124–133. 10.1111/j.1365-313X.2006.02678.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sun C., Hu Z., Zheng T., Lu K., Zhao Y., Wang W., et al. (2017). RPAN: rice pan-genome browser for approximately 3000 rice genomes. Nucleic Acids Res. 45, 597–605. 10.1093/nar/gkw958 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tian T., Liu Y., Yan H., You Q., Yi X., Du Z., et al. (2017). agriGO v2.0: a GO analysis toolkit for the agricultural community, 2017 update. Nucleic Acids Res. 45, W122–W129. 10.1093/nar/gkx382 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Toki S., Hara N., Ono K., Onodera H., Tagiri A., Oka S., et al. (2006). Early infection of scutellum tissue with Agrobacterium allows high-speed transformation of rice. Plant J. 47, 969–976. 10.1111/j.1365-313X.2006.02836.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Trapnell C., Williams B. A., Pertea G., Mortazavi A., Kwan G., van Baren M. J., et al. (2010). Transcript assembly and quantification by RNA-Seq reveals unannotated transcripts and isoform switching during cell differentiation. Nat. Biotechnol. 28, 511–515. 10.1038/nbt.1621 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- van Ooijen G., Mayr G., Kasiem M. M., Albrecht M., Cornelissen B. J., Takken F. L. (2008). Structure-function analysis of the NB-ARC domain of plant disease resistance proteins. J. Exp. Bot. 59, 1383–1397. 10.1093/jxb/ern045 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang W., Mauleon R., Hu Z., Chebotarov D., Tai S., Wu Z., et al. (2018). Genomic variation in 3,010 diverse accessions of Asian cultivated rice. Nature 557, 43–49. 10.1038/s41586-018-0063-9 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang X., Zou B. H., Shao Q. L., Cui Y. M., Lu S., Zhang Y., et al. (2018). Natural variation reveals that OsSAP16 controls low-temperature germination in rice. J. Exp. Botany 69, 413–421. 10.1093/jxb/erx413 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Woo H. R., Goh C. H., Park J. H., de la Serve B. T., Kim J. H., Park Y. I., et al. (2002). Extended leaf longevity in the ore4–1 mutant of Arabidopsis with a reduced expression of a plastid ribosomal protein gene. Plant J. 31, 331–340. 10.1046/j.1365-313X.2002.01355.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wu K., Tian L., Malik K., Brown D., Miki B. (2000). Functional analysis of HD2 histone deacetylase homologues in Arabidopsis thaliana. Plant J. 22, 19–27. 10.1046/j.1365-313x.2000.00711.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Xu C. R., Liu C., Wang Y. L., Li L. C., Chen W. Q., Xu Z. H., et al. (2005). Histone acetylation affects expression of cellular patterning genes in the Arabidopsis root epidermis. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 102, 14469–14474. 10.1073/pnas.0503143102 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yi X., Du Z., Su Z. (2013). PlantGSEA: a gene set enrichment analysis toolkit for plant community. Nucleic Acids Res 41(Web Server issue), W98–W103. 10.1093/nar/gkt281 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zeng D. D., Yang C. C., Qin R., Alamin M., Yue E. K., Jin X. L., et al. (2018). A guanine insert in OsBBS1 leads to early leaf senescence and salt stress sensitivity in rice (Oryza sativa L.). Plant Cell Rep. 37, 933–946. 10.1007/s00299-018-2280-y [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang Z. Y., Li J. J., Pan Y. H., Li J. L., Zhou L., Shi H. L., et al. (2017). Natural variation in CTB4a enhances rice adaptation to cold habitats. Nat. Commun. 8:14788. 10.1038/ncomms14788 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhao L., Liu F., Xu W., Di C., Zhou S., Xue Y., et al. (2009). Increased expression of OsSPX1 enhances cold/subfreezing tolerance in tobacco and Arabidopsis thaliana. Plant Biotechnol. J. 7, 550–561. 10.1111/j.1467-7652.2009.00423.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhao Y., Zhou D. X. (2012). Epigenomic modification and epigenetic regulation in rice. J. Genet. Genomics 39, 307–315. 10.1016/j.jgg.2012.02.009 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zheng Y., Ding Y., Sun X., Xie S., Wang D., Liu X., et al. (2016). Histone deacetylase HDA9 negatively regulates salt and drought stress responsiveness in Arabidopsis. J. Exp. Bot. 67, 1703–1713. 10.1093/jxb/erv562 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Data Availability Statement

The datasets generated for this study can be found in the http://bioinformatics.cau.edu.cn/HDA710_RNA-seq/.