Abstract

Background

The prevalence of cardiovascular diseases (CVDs) is increasing at a high rate, and the available treatment options, sometimes, have complications which necessitates the need to develop safer and efficacious approaches. Ethnomedicinal applications reportedly reduce CVD risk. Ulmus parvifolia Jacq. (Ulmaceae) commonly known as Chinese Elm or Lacebark Elm, is native to China, Japan, and Korea. It exhibits anti-inflammatory, antiviral, and anticancer properties, but its anti-platelet properties have not yet been elucidated.

Purpose

To investigate the pharmacological anti-platelet and anti-thrombotic effects of U. parvifolia bark extract.

Study Design and Methods

Human and rat washed platelets were prepared; light transmission aggregometry and scanning electron microscopy was performed to assess platelet aggregation and the change in platelet shape, respectively. Intracellular calcium mobilization, ATP release, and thromboxane-B2 production were also measured. Integrin αIIbβ3 activation was analyzed in terms of fibrinogen binding, fibronectin adhesion, and clot retraction. The expression of MAPK, Src, and PI3K/Akt pathway proteins was examined. Cyclic nucleotide signaling pathway was evaluated via cAMP elevation and VASP phosphorylation. Anti-thrombotic activity of the extract was evaluated in vivo using an arteriovenous shunt rat model, whereas its effect on hemostasis in mice was assessed via bleeding time assay.

Results

U. parvifolia extract significantly inhibited human and rat platelet aggregation in a dose-dependent manner along with inhibition of calcium mobilization, dense granule secretion, and TxB2 production. Integrin αIIbβ3 mediated inside-out and outside-in signaling events, as evidenced by the inhibition of fibrinogen binding, fibronectin adhesion, and clot retraction. The extract significantly reduced phosphorylation of Src, MAPK (ERK, JNK, and p38MAPK), and PI3K/Akt pathway proteins. Cyclic-AMP levels were elevated in U. parvifolia-treated platelets, while PKAαβγ and VASPser157 phosphorylation was enhanced. U. parvifolia reduced thrombus weight in rats and moderately increased bleeding time in mice.

Conclusion

U. parvifolia modulates platelet responses and inhibit thrombus formation by regulating integrin αIIbβ3 mediated inside-out and outside-in signaling events and cAMP signaling pathway.

Keywords: U. parvifolia, ethnomedicine, platelet, integrin αIIbβ3, cyclic-AMP, VASPser157

Introduction

Cardiovascular diseases (CVDs) are considered a leading cause of death worldwide. In the United States, one in seven and one in nine deaths occurred owing to coronary heart disease and heart failure, respectively, in 2013 (Mozaffarian et al., 2016). World Health Organization stated that CVD accounted for 30% of all deaths in 2005, and in Europe, it remains the primary cause of 42% mortalities in men and 52% in women (Nichols et al., 2013). Following vascular injury, platelets play a crucial role in maintaining hemostasis and preventing blood loss via thrombus formation; however, pathophysiological hyper-activation of platelets is the major cause underlying thrombotic complications, which contribute toward the development of cardiovascular ailments including atherosclerosis, coronary heart disease, stroke, and heart attack (Andrews and Berndt, 2004).

Pharmacological platelet suppression effectively reduces thrombotic events, and many clinical drugs are available for treating and preventing CVD. However, side effects and complications (e.g., gastric bleeding in case of aspirin and sometimes, thrombocytopenia or aplastic anemia in case of clopidogrel) caused by those drugs may outweigh their benefits (Barrett et al., 2008), while a significant part of population is resistant to most commonly used anti-platelet agents i.e., aspirin and clopidogrel (Wang et al., 2006; Ferguson et al., 2008) which necessitate the development of alternative preventive and therapeutic approaches with no or minimal drug-associated complications. Besides anti-platelet drug-based treatment options for thrombotic disorders and CVD-related complications, there is increasing focus on the use of natural products and their bioactive natural compounds including ethnomedicinal applications for CVD treatment and prevention (Badimon et al., 2010; Kim, 2018); similarly, innumerable natural products, including traditional Mediterranean diet and medicinal plants, have also been proven effective with regard to their cardioprotective and anti-platelet effects in the primary and secondary prevention of CVD (Estruch et al., 2013; Rastogi et al., 2016; Irfan et al., 2018c; Shin et al., 2019).

The genus Ulmus includes several species which produce fine wood, medicinal products, and edible fruit. Several Ulmus species reportedly possess anti-oxidative (Jung et al., 2010) and anti-platelet (Yang et al., 2013) properties. Ulmus parvifolia Jacq., commonly known as the Chinese Elm or Lacebark Elm, is native to Korea, Japan, and China, reportedly possesses anti-inflammatory (Mina et al., 2016), anti-allergic (Kim et al., 2016), anti-viral, and anti-cancer (Hamed et al., 2015) properties. While investigating newer and safer efficacious ethnomedicinal products, we recognized the medicinal properties of U. parvifolia bark. Here, we aimed to evaluate anti-platelet and anti-thrombotic effects of U. parvifolia bark ethanol extract on human and rat platelets and explored its pharmacological composition.

Materials and Methods

Extraction and Identification of Active Compounds

Bark of U. parvifolia was obtained from National Institute of Horticultural and Herbal Science (Jeollabuk-do, Republic of Korea). U. parvifolia bark was grounded and extracted with 70% ethanol at 80°C for 3 h, filtered with Whatman™ filter paper (GE Healthcare, PA, USA), condensed in a rotary evaporator (Rotavapor® R-100; B.U.CHI Labortechnik, Switzerland), and lyophilized to obtain powdered extract. The powder was stored at −30°C for further use in experiments.

Identification of the Chemical Constituents

Ultra-performance lipid chromatography (UPLC) system (Waters Corp., Milford, MA, USA), equipped with a binary solvent delivery system, an auto-sampler, and a UV detector, was used for performing chromatographic separation to identify the chemical constituents of U. parvifolia extract as previously described (Jung et al., 2010). Briefly, aliquots (2.0 μl) of each sample were injected into a BEH C18 column (2.1 × 100 mm, 1.7 μm) at a flow rate of 0.4 ml/min and eluted using a chromatographic gradient of two mobile phases (A: water containing 0.1% formic acid; B: acetonitrile containing 0.1% formic acid). A linear gradient was optimized as follows: 0 min, 5% B; 0–8 min, 5–15% B; 8–11 min, 15–80% B; 11–12 min, 80–100% B; 12–13.3 min, 100% B; 13.4–15 min, back to 5% B.

Quantitative Analysis of Identified Compounds

Two main peaks (1 and 2) for catechins were quantified using UV detector at 280 nm wavelength and were calculated using a standard curve obtained from an authentic catechin standards. Standard calibration curves were plotted over a concentration range of 0.0012.5–0.2 mg/ml for five different concentrations of catechin and catechin-7-O-β-D-apiofuranoside (r 2 > 0.998). The amount of compound was finally expressed as mg/g of ethanol extract.

Animals

Sprague–Dawley rats weighing 220–240 g and 7-week-old C57BL/6J male mice weighing 20–22 g were purchased from Orient Co. (Seoul, Republic of Korea); prior to the experiment, they were acclimatized for 1 week in a special animal room maintained at 23 ± 2°C and 50 ± 10% humidity under 12-h light/dark cycles. Experiments were conducted according to IACUC guidelines, and experimental protocols were approved by the Ethics Committee of College of Veterinary Medicine, Kyungpook National University, Daegu, Korea (Permit number: 2017-0014).

Preparation of Washed Human and Rat Platelets

Human platelet-rich plasma (PRP) collected from healthy volunteers who provided informed consent was obtained from the Korean Red Cross Blood Center (KRBC, Changwon, Korea), and its experimental use was approved by KRBC and the Korea National Institute for Bioethics Policy Public Institutional Review Board (PIRB17-1019-03). Washed human and rat platelets were prepared as previously described (Irfan et al., 2018a).

Platelet Aggregation Assay and Scanning Electron Microscope (SEM) Analysis

To assess platelet aggregation, the standard procedure of light-transmission aggregometry was performed using a Chrono-log aggregometer (Havertown, PA, USA), as previously described (Irfan et al., 2018b). Briefly, washed platelets were pre-incubated with various concentrations of either U. parvifolia extract or vehicle (DMSO) for 1 min in the presence of 1 mM calcium chloride (CaCl2), followed by stimulation with various agonists (Collagen, ADP, or thrombin) for 5 min with continuous stirring at 37°C. DMSO concentration was maintained at <0.1%.

A field emission SEM was used to assess platelet shape change and aggregation by obtaining ultrastructure images as previously described (Irfan et al., 2018a).

Immunoblotting

Washed platelets were pre-incubated with various concentrations of U. parvifolia extract along with 1 mM CaCl2 for 1 min at 37°C and then stimulated with collagen for 5 min under continuous stirring. Platelet aggregation was terminated by adding lysis buffer (PRO-PREP; iNtRON Biotechnology, Seoul, Korea), and protein concentration was estimated using BCS assay (PRO-MEASURE; iNtRON Biotechnology). Total platelet proteins were separated in a 10% SDS-PAGE and transferred to PVDF membranes. Membranes were blocked with 5% skim milk, probed with respective antibodies (i.e., Src, phospho-Src, ERK, phospho-ERK, JNK, phospho/JNK, p38MAPK, phospho-p38MAPK, phospho-PI3K, PI3K, Akt, phospho-Akt, VASP, phospho-VASPser157, PKAαβγ, and β-actin) and visualized using enhanced chemiluminescence.

Arteriovenous Shunt Model

The anti-thrombotic activity of U. parvifolia extract was assessed in a rat extracorporeal shunt model as previously described (Irfan et al., 2018c). Rats were orally administered with the vehicle, U. parvifolia extract, or ASA once daily for 3 days. Two hours after the last administration, rats were anesthetized and shunt was placed for 15 min after initiating extracorporeal circulation. Subsequently, blood flow was stopped and the thrombus formed was weighed.

In Vivo Bleeding Assay

Male mice were divided into three treatment groups (n = 5, each). They were intraperitoneally administered with saline, ASA, or U. parvifolia extract once daily for 3 days. One hour after the last administration, mice were anaesthetized, and tail bleeding assay was performed as previously described (Irfan et al., 2018b).

Statistical Analysis

Data were analyzed by one-way analysis of variance (ANOVA), followed by measurement of statistically significant differences using Dunnett's post-hoc test (SAS Institute Inc., Cary, NC, USA). All data are presented as the mean ± standard deviation (SD). A p value of ≤0.05 was considered statistically significant.

Detailed description on; chemicals and reagent sources, preparation of washed human and rat platelets, scanning electron microscope (SEM) analysis, ATP release assay, measurement of [Ca2+]i mobilization, flow cytometry, fibronectin adhesion assay, clot retraction, measurement of cyclic-AMP, AV-shunt model, and in vivo bleeding assay has been included in Supplementary Material .

Results

U. parvifolia Inhibits Agonist-Induced Human and Rat Platelet Aggregation

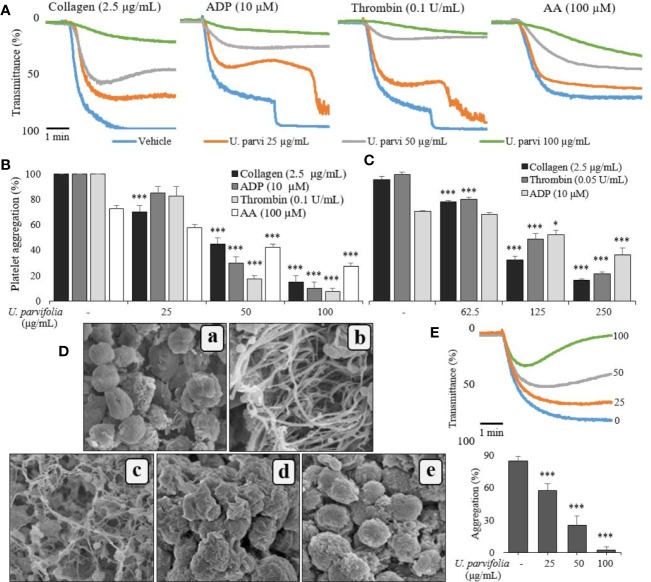

Initial screening confirmed that U. parvifolia was effective against human and rat platelet aggregation induced by several agonists, including collagen, ADP, AA, and thrombin. Figures 1A, B show that U. parvifolia significantly inhibited agonist-induced aggregation in a dose-dependent manner in rat platelets; similar inhibitory results were obtained in agonist-induced aggregation in human platelets ( Figure 1C ). The extract also potently inhibited ADP-induced aggregation measured in rat PRP, in a dose-dependent manner ( Figure 1E ). We examined the effect of U. parvifolia extract on platelet shape change and aggregation using SEM. We found a dose-dependent inhibition of collagen-induced platelet shape change and aggregation in U. parvifolia-treated rat platelets compared with that in vehicle-treated platelets ( Figure 1D ).

Figure 1.

U. parvifolia inhibits agonist-induced human and rat platelet aggregation. Collagen-, ADP-, arachidonic acid (AA), or thrombin-stimulated washed platelets (A, B, D, E, from rats; C, from humans) pre-treated with vehicle or various U. parvifolia extract concentrations in the presence of 1-mM CaCl2. (D) Representative SEM images (5,000×) of collagen (2.5 µg/ml)-stimulated platelets pre-treated with vehicle or various U. parvifolia extract concentrations [(a) Resting, (b) Vehicle, (c) 25 µg/ml, (d) 50 µg/ml, (e) 100 µg/ml]. (E) Rat PRP was incubated with vehicle or various concentrations of extract in the presence of 10-mM CaCl2 for 1 min and then stimulated with ADP (25 µM) for 5 min. The graphs show mean ± SD values from at least four independent experiments. *p < 0.05 and ***p < 0.001 versus control.

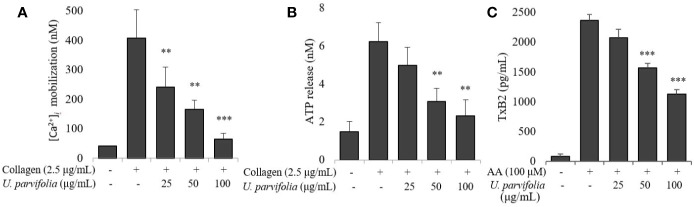

U. parvifolia Reduces [Ca2+]i Mobilization, Dense Granule Secretion, and Thromboxane-B2 Production

We assessed the effect of U. parvifolia extract on collagen-stimulated platelet intracellular calcium ion ([Ca2+]i) mobilization, ATP release, and thromboxane production; and found its significant and dose-dependent inhibitory activity against [Ca2+]i mobilization while it also markedly reduced ATP and thromboxane-B2 release ( Figure 2 ).

Figure 2.

U. parvifolia inhibits [Ca2+]i mobilization and reduces ATP release and TxB2 production. (A) Fura 2/AM-loaded rat platelets pre-treated with vehicle or various U. parvifolia extract concentrations and stimulated with collagen (2.5 µg/ml) for 3 min. Assessment of ATP concentration (B), and thromboxane-B2 production (C) was done in supernatant of stimulated washed platelets suspension pre-treated with vehicle or various U. parvifolia extract concentrations and stimulated with collagen for 5 min on a luminometer or TxB2 ELISA kit, respectively. Results are represented as mean ± SD values from at least four independent experiments. **p < 0.01 and ***p < 0.001 versus control.

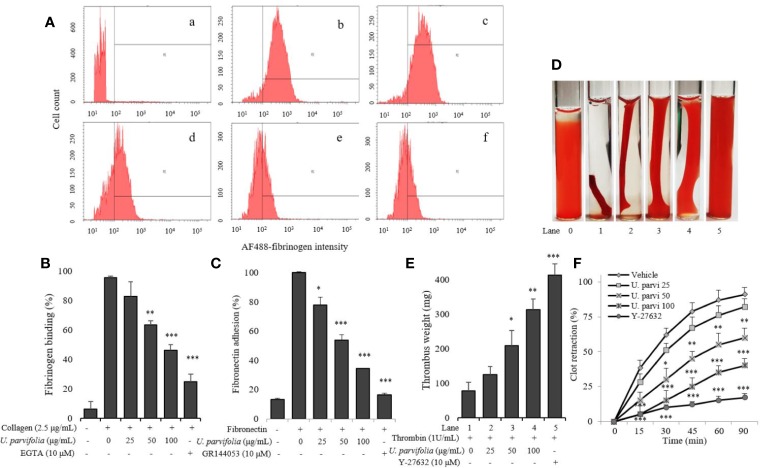

U. parvifolia Attenuates Integrin αIIbβ3-Mediated Inside-Out and Outside-In Signaling

We examined whether various concentrations of U. parvifolia extract modulate collagen-stimulated platelet integrin signaling, and found that they significantly attenuated fibrinogen binding to integrin αIIbβ3 in a dose-dependent manner ( Figures 3A, B ). We also examined inhibitory activity of U. parvifolia extract on fibronectin adhesion and found that it significantly and dose-dependently reduced platelet adhesion on fibronectin-coated surface compared with vehicle control ( Figure 3C ). We also found that U. parvifolia extract significantly reduced clot retraction in a dose-dependent manner ( Figures 3D–F ).

Figure 3.

U. parvifolia inhibits integrin αIIbβ3-mediated inside-out and outside-in signaling. (A, B) Flow cytometric measurements of fibrinogen binding in platelets treated with vehicle, various U. parvifolia extract concentrations or EGTA [(a) Resting, (b) Vehicle, (c) 25 µg/ml, (d) 50 µg/ml, and (e) 100 µg/ml, (f) 10 µM EGTA)] and stimulated with collagen (b-f). (C) Results of fibronectin adhesion assay, which was performed using an assay kit according to the manufacturer's protocol and by following the procedure described in the methods section. (D) In vitro effect of U. parvifolia extract on clot retraction for 2 h at room temperature after thrombin addition and photographed with 15 min intervals. Representative images of clot retraction at 90 min after thrombin addition in the presence and absence of U. parvifolia extract. Y-27632 (ROCK inhibitor) was used as a control. (F) Kinetics of clot retraction were measured by Image-J software and clot surface areas were plotted as a percentage of retraction. Bar graphs summarizing the inhibitory effect of U. parvifolia extract on fibrinogen binding to integrin αIIbβ3 (B), fibronectin adhesion (C), clot retraction (E), and kinetics of clot retraction (F). Results are shown as mean ± SD values from at least four independent experiments. *p < 0.05, **p < 0.01, and ***p < 0.001 versus control.

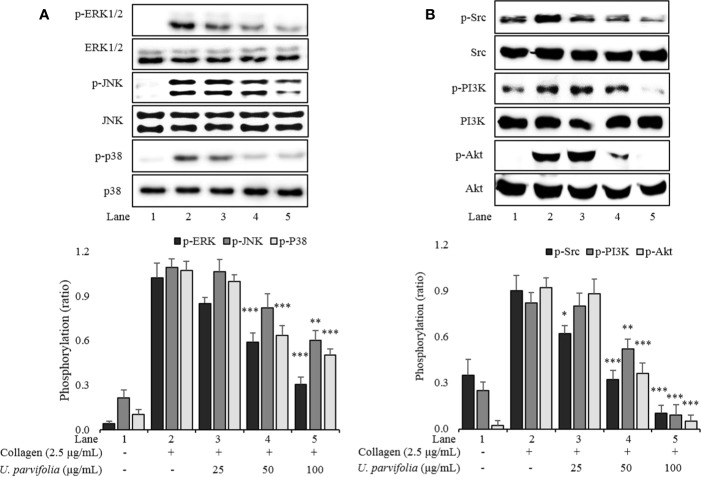

U. parvifolia Attenuates MAPK, Src, and PI3K/Akt Phosphorylation

We explored the underlying inhibitory mechanism of the extract, and our results revealed that U. parvifolia extract significantly inhibited collagen-mediated GPVI downstream signaling by attenuating the phosphorylation of ERK, JNK, p38MAPK, Src, and PI3K/Akt pathway molecules ( Figure 4 ).

Figure 4.

U. parvifolia attenuates phosphorylation levels of MAPKs (A), Src, and PI3K/Akt (B). Immunoblotting was conducted to analyze the phosphorylation of signaling molecules extracted from the lysates of collagen-stimulated washed platelets that were pre-treated with either U. parvifolia extract or vehicle. Representative immunoblot images and data (mean ± SD) from at least four independent experiments are shown. *p < 0.05, **p < 0.01, and ***p < 0.001 versus agonist-treated group.

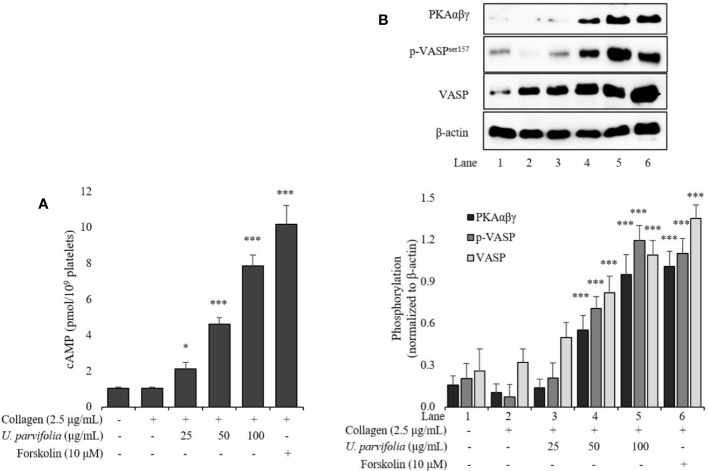

U. parvifolia Elevates cAMP Levels and Enhances VASP and PKAαβγ Phosphorylation

We assessed intracellular cAMP levels in collagen-stimulated platelets which were markedly amplified owing to treatment with ascending concentrations of U. parvifolia extract ( Figure 5A ). Similarly, phosphorylation of not only VASP but also phospho-VASPser157 (a preferred site by PKA) was significantly enhanced in a dose-dependent manner in U. parvifolia-treated platelets. Furthermore, to evaluate whether the observed effect is mediated via cAMP–PKA–VASPser157-dependent pathway, we assessed PKAαβγ phosphorylation; it was also found to be significantly increased in a dose-dependent manner ( Figure 5B ).

Figure 5.

U. parvifolia elevates cAMP production and enhances VASP and PKAαβγ phosphorylation. (A) cAMP immunoassay performed for collagen-stimulated washed platelets pre-treated with various U. parvifolia extract concentrations, vehicle, or forskolin. (B) Immunoblotting analysis conducted for the phosphorylation of total VASP, p-VASPser157, and PKAαβγ extracted from platelets. Representative immunoblot images and graphs plotted for the data (mean ± SD values) obtained from at least four independent experiments are shown. *p < 0.05 and ***p < 0.001 versus agonist-treated group.

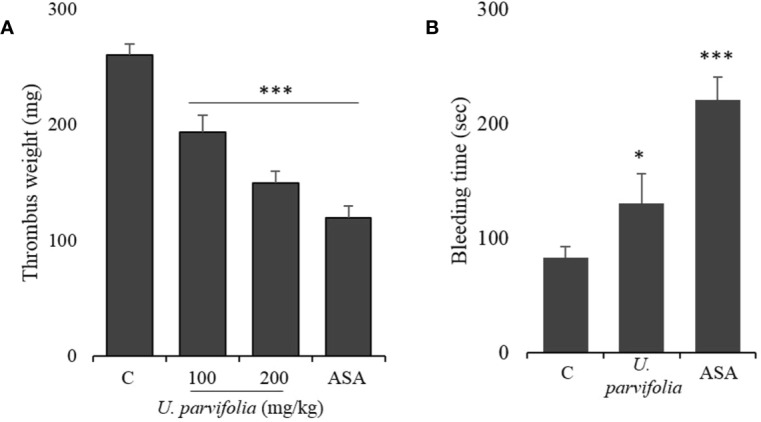

U. parvifolia Prevents Thrombosis and Regulates Hemostasis

Figure 6A shows that U. parvifolia extract significantly reduced thrombus weight in a dose-dependent manner compared with vehicle control. Similarly, our results of tail bleeding assay in mice also revealed that U. parvifolia extract moderately increased bleeding time compared to vehicle control while time to cessation of bleeding was greatly increased in ASA group ( Figure 6B ).

Figure 6.

U. parvifolia inhibits thrombus formation and modulates hemostasis. (A) Evaluation of in vivo anti-thrombotic activity and determination of thrombus weight in AV shunt model of rats that were orally administered with saline, U. parvifolia extract (100–200 mg/kg), or ASA (50 mg/kg). (B) Results of tail bleeding assay for homeostasis measurement in mice administered with U. parvifolia extract (200 mg/kg), ASA (50 mg/kg), or saline (n = 5 in each group). Graph shows mean ± SD values from at least five independent experiments performed. *p < 0.05; ***p < 0.001 versus control.

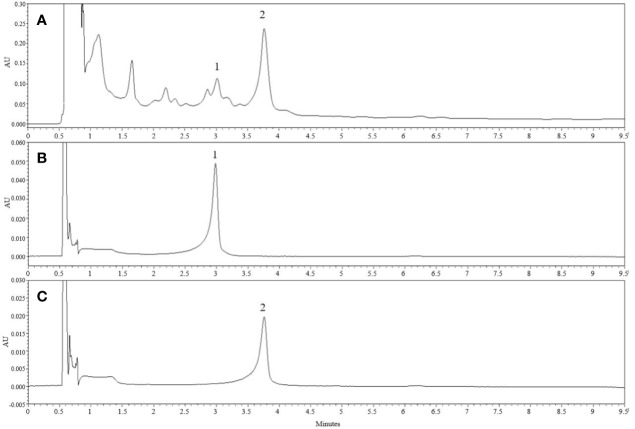

Chemical Constituents of U. parvifolia Extract

UPLC results revealed marker compounds in the extract i.e., catechin (tR = 2.98 min) and catechin-7-O-β-D-apiofuranoside (tR = 3.651 min) ( Figure 7 ). Quantitative analysis of the given extract revealed that catechin and catechin-7-O-β-D-apiofuranoside were present at concentrations of 6.14 and 156.3 mg/g, respectively.

Figure 7.

Chemical constituents of U. parvifolia extract. (A) The UPLC chromatogram of EtOH extract of U. parvifolia was detected at 280 nm UV. (B, C) Chromatograms of a standard solution. Peaks 1 ((+)-catechin) and 2 (catechin-7-O-β-D-apiofuranoside).

Discussion

Here, we evaluated anti-platelet and anti-thrombotic effects of U. parvifolia bark ethanol extract and determined its potential pharmacological properties involved in the modulation of platelet functions which may be attributed to its phenolic constituents, especially catechins.

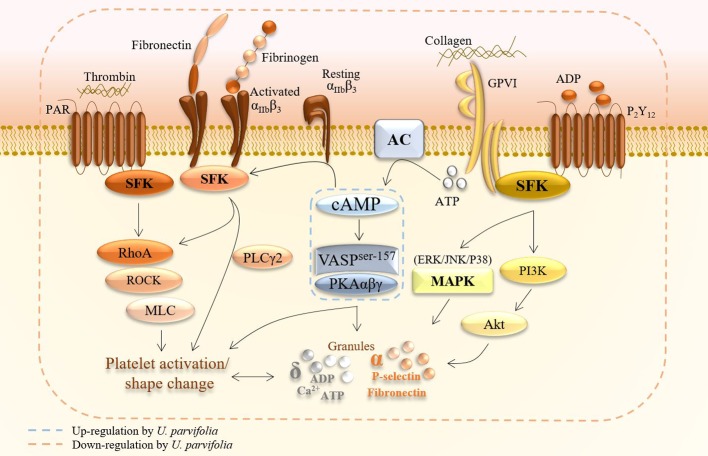

Collagen, thrombin, and ADP are agonists that induce strong platelet aggregation by triggering downstream signaling events, including granule secretion, via activation of GPVI, proteinase-activated receptor (PAR), and P2Y12 receptor signaling pathways, respectively. These platelet-signaling events are subdivided into (i) early receptor signaling triggered by agonists or adhesive stimulants; (ii) merging of common pathways and amplification of signaling; (iii) inside-out signaling which causes conformational change of integrin αIIbβ3 structure to allow fibrinogen binding and early phase of platelet adhesion; and (iv) outside-in signaling which augments late phases of adhesion and clot retraction. Moreover, platelets contain dense (δ) granules, including Ca2+, ATP, and serotonin, as well as alpha (α) granules packed with adhesive ligands including fibrinogen, fibronectin, and P-selectin. Secretion of these granules upon platelet activation further enhances platelet adhesion, shape change, and aggregation ( Figure 8 ) (Estevez and Du, 2017; Irfan et al., 2020). The unceasing change in shape, which results in full activation of platelets, can be best observed under SEM. Our initial screening results revealed that U. parvifolia extract had strong inhibitory effects against the above mentioned agonists, and it significantly inhibited platelet aggregation and shape change in a dose-dependent manner; these findings indicated that the extract exerts strong anti-platelet activity via inhibition of several platelet-signaling pathways, as detailed in Figure 8 . To examine the effects on physiological condition of platelets, we used rat PRP and found that the extract potently inhibited ADP-induced platelet aggregation; indicating that constituents of extract have strong ability to modulate platelet responses and aggregation. COX-1 inhibitor like aspirin and antagonists of the P2Y12 for ADP like clopidogrel and ticagrelor are currently used in coronary interventions and prevention of cardiovascular thrombotic events which are sometimes, impeded by side effects or resistant to some patients (Cattaneo, 2011). Our results show that U. parvifolia extract with several pharmacological constituents could be a potent natural candidate to deal with platelet-related disorders.

Figure 8.

A schematic summary of inhibitory effects of U. parvifolia extract on platelet intracellular signaling pathway.

To investigate the underlying mechanism, we further examined intracellular [Ca2+]i mobilization, dense granule secretion, and thromboxane production. We found that our extract markedly inhibited [Ca2+]i mobilization, ATP secretion, and thromboxane-B2 production. Similarly, significant inhibition of fibrinogen binding to integrin αIIbβ3 and fibronectin adhesion was observed, indicating that U. parvifolia extract modulates integrin αIIbβ3-mediated inside-out signaling.

When fibrinogen binds to αIIbβ3, it transduces signal into the cell (termed as outside-in signaling), which further enhances platelet adhesion and spreading, thrombus formation, and clot retraction (Irfan et al., 2018a). Similarly, fibronectin is another adhesive ligand that stabilizes thrombus formation in the vasculature. It binds to integrin αIIbβ3 and augments platelet aggregation by developing cohesive aggregates (Pankov and Yamada, 2002). GTPases regulate platelet adhesion, shape change, and clot retraction through actin cytoskeletal changes. Rho kinases (ROCKs) are downstream regulators which mediate RhoA-stimulated actin cytoskeletal changes via myosin light chain phosphorylation. The role of Rho kinase in facilitating clot retraction has been previously described using Rho kinase or ROCK inhibitor (Y-27632) (Liao et al., 2007). Among SFKs, Src kinase is predominantly expressed in platelets and plays a vital role in integrin αIIbβ3-mediated signaling and is reportedly also involved in clot retraction (Senis et al., 2014). U. parvifolia extract significantly inhibited clot retraction and reduced Src phosphorylation. This result suggested that U. parvifolia extract modulated integrin αIIbβ3-mediated outside-in signaling by inhibiting Rho kinase and Src kinase and consequently inhibiting platelet activation. Antagonists of glycoprotein IIb/IIIa (αIIbβ3) such as abciximab and eptifibatide are used to reduce occlusive arterial events in patients with atherosclerosis (Cattaneo, 2011). Our results show that the extract and its constituents could be a great natural alternate to be considered in clinical interventions.

MAPKs (ERK, JNK, and p38MAPK) are highly expressed in platelets and become activated when platelets encounter any potential agonists; phosphorylation of these proteins triggers granule secretion which further enhances platelet aggregation (Adam et al., 2008). Src family kinases (SFKs) participate in early signaling of platelet activation and play a central role in mediating platelet functions. Moreover, MAPK and PI3K/Akt are downstream effectors of SFK and play critical roles in platelet activation by influencing calcium mobilization, granule secretion, and platelet aggregation (Senis et al., 2014). Here, our U. parvifolia extract impeded these molecules and significantly reduced the phosphorylation of MAPK and PI3K/Akt, indicating its possible inhibitory mechanism against platelet functions.

Cyclic-AMP and cyclic nucleotide-dependent protein kinase are suppressed in activated platelets, whereas elevated intracellular cAMP levels inhibit platelet activation and aggregation (Li et al., 2003). Actin dynamics are relegated by vasodilator-stimulated phosphoprotein (VASP) which is a substrate of cyclic nucleotide (cAMP/cGMP)-dependent protein kinases (i.e., PKA/PKG); stimulation of these kinases augment VASP phosphorylation and inhibit platelet activation and aggregation. Elevation of cAMP levels reportedly inhibits platelet activation by activation of VASP via specifically increased phosphorylation of VASPser157 (Ok et al., 2012). VASP ser157 acts as a substrate for cAMP-dependent PKA; its stimulation inhibits platelet activation via modulation of platelet secretion and adhesion, and its phosphorylation also hinders integrin αIIbβ3-mediated signaling, thereby inhibiting platelet aggregation (Wentworth et al., 2006). Here, U. parvifolia extract inhibited platelet activation by upregulating cAMP-PKA-VASPser157 pathway. Figure 8 summarizes the effects of U. parvifolia on platelet intracellular signaling.

AV-shunt model is widely used for assessing anti-thrombotic activity (Endale et al., 2012), and well established to assess in vivo anti-thrombotic effects. Umetsu and Sanai (Umetsu and Sanai, 1978) have stated that the shunt comprises activated platelets, fibrin, and trapped erythrocytes and that its formation can be attenuated by anti-platelet agents. A similar thrombus formation occurs in coronary arteries following heart attack or myocardial infarction (Silvain et al., 2011). Our results revealed that as opposed to treatment with vehicle, treatment with U. parvifolia moderately increased bleeding time in mice and a substantially reduced thrombus formation in rats via inhibition of platelet activation.

UPLC is a powerful tool to identify and characterize the chemical profiles of natural products (Liu et al., 2013). Catechins are polyphenolic phytochemicals exhibiting several biological activities in the human body, potentially in the treatment and prevention of cardiovascular ailments through modulation of blood lipid metabolism, cardioprotective effects including vascular endothelium protection and stabilizing blood pressure (Shaterzadeh-Yazdi et al., 2017), while another study has also summarized the beneficial effects of catechins on cardiovascular system (Braicu et al., 2013). Most of the Ulmus species are reported to possess pharmacological properties including antiplatelet effects; due to their polyphenolic contents such as catechin, epicatechin, catechin-7-O-β-D-apiofuranoside, and catechin-7-O-β-D-xylopyranoside (Jung et al., 2010; Yang et al., 2013; Park et al., 2020). Among these catechins, catechin-7-O-β-D-apiofuranoside has been also known for its anti-oxidant, anti-inflammatory and anti-fibrotic properties (MinHee et al., 2003; Jung et al., 2010; Kwon et al., 2011; Park et al., 2020). Previous studies have shown that catechins inhibit platelet activity by regulating calcium mobilization (Kang et al., 2001), impeding several signaling kinases including ERK and p38MAPK (Lill et al., 2003), increasing cAMP levels, and enhancing VASPser157 phosphorylation in platelets (Ok et al., 2012); they also inhibit ERK, JNK, p38MAPK, and Akt activation in vascular smooth muscles and endothelial cells. Our UPLC results suggest that the extract predominantly contains catechins, which are most probably responsible for the inhibition of platelet activation and thrombus formation via regulation of MAPK pathway and cAMP signaling.

Conclusion

U. parvifolia substantially inhibits agonist-stimulated platelet aggregation, [Ca2+]i mobilization, dense granule secretion, fibrinogen binding, and fibronectin adhesion as well as reduces clot retraction, which in turn inhibit integrin αIIbβ3-mediated inside-out and outside-in signaling. It also attenuates the phosphorylation of Src, MAPK's, and PI3K/Akt-signaling molecules; elevates cyclic-AMP levels; enhances phosphorylation of VASPser157 and PKAαβγ; and inhibits in vivo thrombus formation. Taken together, we conclude that U. parvifolia modulates platelet functions and inhibits thrombus formation by regulating integrin αIIbβ3 and cyclic nucleotide signaling; thus, it is a potential candidate for preventing and treating platelet-related CVDs.

Data Availability Statement

All datasets generated for this study are included in the article/ Supplementary Material .

Ethics Statement

The studies involving human participants were reviewed and approved by Korean Red Cross Blood Center and the Korea National Institute for Bioethics Policy Public Institutional Review Board (PIRB17-1019-03). Written informed consent for participation was not required for this study in accordance with the national legislation and the institutional requirements. The animal study was reviewed and approved by Ethics Committee of College of Veterinary Medicine, Kyungpook National University, Daegu, Korea (Permit number: 2017-0014).

Author Contributions

MI and MR designed and conceptualized the study. MI performed experiments, analyzed data, and wrote manuscript. H-WK, D-HL, J-HS, HY, D-SK, S-BH, and S-DK performed partial experiments and analyzed data. MI critically revised the manuscript. MR and S-DK supervised the research work. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Funding

This research was supported by the National Research Foundation of Korea (2018R1D1A1A09083797).

Conflict of Interest

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Acknowledgments

Ulmus parvifolia bark was provided by National Institute of Horticultural and Herbal Science (Jeollabuk-do, Republic of Korea).

Supplementary Material

The Supplementary Material for this article can be found online at: https://www.frontiersin.org/articles/10.3389/fphar.2020.00698/full#supplementary-material

Abbreviations

AA, Arachidonic acid; ACD, Acid-citrate-dextrose; ADP, Adenosine diphosphate ; AV-shunt, Arteriovenous shunt; Akt, Protein kinase B; DMSO, Dimethyl sulfoxide ; ERK, Extracellular signal-regulated kinase; GPVI, Glycoprotein VI; JNK, c-Jun N-terminal kinase; MAPK, Mitogen-activated protein kinase; PAR, Proteinase-activated receptor; PI3K, Phosphatidylinositol 3-kinases; PKA, Protein kinase A; PRP, Platelet-rich plasma ; Rho-A, Rho kinase A; SEM, Scanning electron microscope ; SFK, Src family kinase; TxB2, Thromboxane-B2; VASP, Vasodilator-stimulated phosphoprotein.

References

- Adam F., Kauskot A., Rosa J. P., Bryckaert M. (2008). Mitogen-activated protein kinases in hemostasis and thrombosis. J. Thromb. Haemostasis 6 (12), 2007–2016. 10.1111/j.1538-7836.2008.03169.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Andrews R. K., Berndt M. C. (2004). Platelet physiology and thrombosis. Thromb. Res. 114 (5-6), 447–453. 10.1016/j.thromres.2004.07.020 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Badimon L., Vilahur G., Padro T. (2010). Nutraceuticals and atherosclerosis: human trials. Cardiovasc. Ther. 28 (4), 202–215. 10.1111/j.1755-5922.2010.00189.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Barrett N. E., Holbrook L., Jones S., Kaiser W. J., Moraes L. A., Rana R., et al. (2008). Future innovations in anti-platelet therapies. Br. J. Pharmacol. 154 (5), 918–939. 10.1038/bjp.2008.151 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Braicu C., Ladomery M. R., Chedea V. S., Irimie A., Berindan-Neagoe I. (2013). The relationship between the structure and biological actions of green tea catechins. Food Chem. 141 (3), 3282–3289. 10.1016/j.foodchem.2013.05.122 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cattaneo M. (2011). Resistance to anti-platelet agents. Thromb. Res. 127, S61–S63. 10.1016/S0049-3848(11)70017-2 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Endale M., Lee W. M., Kamruzzaman S. M., Kim S. D., Park J. Y., Park M. H., et al. (2012). Ginsenoside-Rp1 inhibits platelet activation and thrombus formation via impaired glycoprotein VI signalling pathway, tyrosine phosphorylation and MAPK activation. Br. J. Pharmacol. 167 (1), 109–127. 10.1111/j.1476-5381.2012.01967.x [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Estevez B., Du X. (2017). New Concepts and Mechanisms of Platelet Activation Signaling. Physiol. (Bethesda Md.) 32 (2), 162–177. 10.1152/physiol.00020.2016 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Estruch R., Ros E., Salas-Salvado J., Covas M. I., Corella D., Aros F., et al. (2013). Primary prevention of cardiovascular disease with a Mediterranean diet. N. Engl. J. Med. 368 (14), 1279–1290. 10.1056/NEJMoa1200303 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ferguson A. D., Dokainish H., Lakkis N. (2008). Aspirin and clopidogrel response variability: review of the published literature. Texas Heart Institute J. 35 (3), 313. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hamed M. M., El-Amin S. M., Refahy L. A., Soliman E.-S. A., Mansour W. A., Taleb H. M. A., et al. (2015). Anticancer and antiviral estimation of three Ulmus pravifolia extracts and their chemical constituents. Oriental J. Chem. 31 (3), 1621. 10.13005/ojc/310341 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Irfan M., Jeong D., Kwon H.-W., Shin J.-H., Park S.-J., Kwak D., et al. (2018. a). Ginsenoside-Rp3 inhibits platelet activation and thrombus formation by regulating MAPK and cyclic nucleotide signaling. Vasc. Pharmacol. 109, 45–55. 10.1016/j.vph.2018.06.002 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Irfan M., Jeong D., Saba E., Kwon H.-W., Shin J.-H., Jeon B.-R., et al. (2018. b). Gintonin modulates platelet function and inhibits thrombus formation via impaired glycoprotein VI signaling. Platelets 30 (5), 589–598. 10.1080/09537104.2018.1479033 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Irfan M., Kwon T.-H., Yun B.-S., Park N.-H., Rhee M. H. (2018. c). Eisenia bicyclis (brown alga) modulates platelet function and inhibits thrombus formation via impaired P2Y12 receptor signaling pathway. Phytomedicine 40, 79–87. 10.1016/j.phymed.2018.01.003 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Irfan M., Kim M., Rhee M. H. (2020). Anti-platelet role of Korean ginseng and ginsenosides in cardiovascular diseases. J. Ginseng Res. 44 (1), 24–32. 10.1016/j.jgr.2019.05.005 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jung M. J., Heo S.-I., Wang M.-H. (2010). HPLC analysis and antioxidant activity of Ulmus davidiana and some flavonoids. Food Chem. 120 (1), 313–318. 10.1016/j.foodchem.2009.09.085 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Kang W.-S., Chung K.-H., Chung J.-H., Lee J.-Y., Park J.-B., Zhang Y.-H., et al. (2001). Antiplatelet activity of green tea catechins is mediated by inhibition of cytoplasmic calcium increase. J. Cardiovasc. Pharmacol. 38 (6), 875–884. 10.1097/00005344-200112000-00009 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kim S. P., Lee S. J., Nam S. H., Friedman M. (2016). Elm tree (Ulmus parvifolia) bark bioprocessed with mycelia of Shiitake (Lentinus edodes) mushrooms in liquid culture: Composition and mechanism of protection against allergic asthma in mice. J. Agric. Food Chem. 64 (4), 773–784. 10.1021/acs.jafc.5b04972 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kim J.-H. (2018). Pharmacological and medical applications of Panax ginseng and ginsenosides: A review for use in cardiovascular diseases. J. Ginseng Res. 42 (3), 264–269. 10.1016/j.jgr.2017.10.004 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kwon J.-H., Kim S.-B., Park K.-H., Lee M.-W. (2011). Antioxidative and anti-inflammatory effects of phenolic compounds from the roots of Ulmus macrocarpa. Arch. Pharmacal Res. 34 (9), 1459. 10.1007/s12272-011-0907-4 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li Z., Ajdic J., Eigenthaler M., Du X. (2003). A predominant role for cAMP-dependent protein kinase in the cGMP-induced phosphorylation of vasodilator-stimulated phosphoprotein and platelet inhibition in humans. Blood 101 (11), 4423–4429. 10.1182/blood-2002-10-3210 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liao J. K., Seto M., Noma K. (2007). Rho kinase (ROCK) inhibitors. J. Cardiovasc. Pharmacol. 50 (1), 17. 10.1097/FJC.0b013e318070d1bd [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lill G., Voit S., Schrör K., Weber A.-A. (2003). Complex effects of different green tea catechins on human platelets. FEBS Lett. 546 (2-3), 265–270. 10.1016/S0014-5793(03)00599-4 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liu M.-H., Tong X., Wang J.-X., Zou W., Cao H., Su W.-W. (2013). Rapid separation and identification of multiple constituents in traditional Chinese medicine formula Shenqi Fuzheng Injection by ultra-fast liquid chromatography combined with quadrupole-time-of-flight mass spectrometry. J. Pharmaceut. Biomed. Anal. 74, 141–155. 10.1016/j.jpba.2012.10.024 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mina S. A., Melek F. R., Adeeb R. M., Hagag E. G. (2016). LC/ESI-MS/MS profiling of Ulmus parvifolia extracts and evaluation of its anti-inflammatory, cytotoxic, and antioxidant activities. Z. Für Naturforschung. C. 71 (11-12), 415–421. 10.1515/znc-2016-0057 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- MinHee K., Ee H. J., Yun L. D. (2003). Catechin-7-O-β-D-apiofuranoside: An Anti-inflammatory constituent from alnus japonica bark. Proc. Convention Pharmaceut. Soc. Korea 2 (2), 191–192. [Google Scholar]

- Mozaffarian D., Benjamin E. J., Go A. S., Arnett D. K., Blaha M. J., Cushman M., et al. (2016). Heart disease and stroke statistics-2016 update a report from the American Heart Association. Circulation 133 (4), e38–e48. 10.1161/CIR.0000000000000366s [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nichols M., Townsend N., Scarborough P., Rayner M. (2013). Cardiovascular disease in Europe: epidemiological update. Eur. Heart J. 34 (39), 3028–3034. 10.1093/eurheartj/eht356 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ok W.-J., Cho H.-J., Kim H.-H., Lee D.-H., Kang H.-Y., Kwon H.-W., et al. (2012). Epigallocatechin-3-gallate has an anti-platelet effect in a cyclic AMP-dependent manner. J. Atheroscl. Thromb. 19 (4), 1204090486–1204090486. 10.5551/jat.10363 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pankov R., Yamada K. M. (2002). Fibronectin at a glance. J. Cell Sci. 115 (20), 3861. 10.1242/jcs.00059 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Park Y. J., Kim D. M., Jeong M. H., Yu J. S., So H. M., Bang I. J., et al. (2020). (–)-Catechin-7-O-β-d-Apiofuranoside Inhibits Hepatic Stellate Cell Activation by Suppressing the STAT3 Signaling Pathway. Cells 9 (1), 30. 10.3390/cells9010030 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rastogi S., Pandey M. M., Rawat A. (2016). Traditional herbs: a remedy for cardiovascular disorders. Phytomedicine 23 (11), 1082–1089. 10.1016/j.phymed.2015.10.012 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Senis Y. A., Mazharian A., Mori J. (2014). Src family kinases: at the forefront of platelet activation. Blood 124 (13), 2013–2024. 10.1182/blood-2014-01-453134 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shaterzadeh-Yazdi H., Farkhondeh T., Samarghandian S. (2017). An Overview on Cardiovascular Protective Effects of Catechins. Cardiovasc. Haematolog. Disorders-Drug Targets (Formerly Curr. Drug Targets-Cardiovasc. Hematolog. Disorders) 17 (3), 154–160. 10.2174/1871529X17666170921115735 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shin J.-H., Kwon H.-W., Rhee M. H., Park H.-J. (2019). Inhibitory effects of thromboxane A2 generation by ginsenoside Ro due to attenuation of cytosolic phospholipase A2 phosphorylation and arachidonic acid release. J. Ginseng Res. 43 (2), 236–241. 10.1016/j.jgr.2017.12.007 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Silvain J., Collet J.-P., Nagaswami C., Beygui F., Edmondson K. E., Bellemain-Appaix A., et al. (2011). Composition of coronary thrombus in acute myocardial infarction. J. Am. Coll. Cardiol. 57 (12), 1359–1367. 10.1016/j.jacc.2010.09.077 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Umetsu T., Sanai K. (1978). Effect of 1-methyl-2-mercapto-5-(3-pyridyl)-imidazole (KC-6141), an anti-aggregating compound, on experimental thrombosis in rats. Thromb. Haemost. 39 (1), 74–83. 10.1055/s-0038-1646657 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang T. H., Bhatt D. L., Topol E. J. (2006). Aspirin and clopidogrel resistance: an emerging clinical entity. Eur. Heart J. 27 (6), 647–654. 10.1093/eurheartj/ehi684 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wentworth J. K., Pula G., Poole A. W. (2006). Vasodilator-stimulated phosphoprotein (VASP) is phosphorylated on Ser157 by protein kinase C-dependent and-independent mechanisms in thrombin-stimulated human platelets. Biochem. J. 393 (2), 555–564. 10.1042/BJ20050796 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yang W.-K., Lee J.-J., Sung Y.-Y., Kim D.-S., Myung C.-S., Kim H. K. (2013). Extract of Ulmus macrocarpa Hance prevents thrombus formation through antiplatelet activity. Mol. Med. Rep. 8 (3), 726–730. 10.3892/mmr.2013.1581 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Data Availability Statement

All datasets generated for this study are included in the article/ Supplementary Material .