Abstract

Hypoxia/reoxygenation (H/R) may play an important role via senescence in the mechanism of osteoarthritis (OA) development. The synovial membrane is highly sensitive to H/R due to its oxygen consumption feature. Excessive mechanical loads and oxidative stress caused by H/R induce a senescence-associated secretory phenotype (SASP), which is related to the development of OA. The aim of the present study was to investigate the differences of SASP manifestation in synovial tissue masses between tissues from healthy controls and patients with OA. The present study used tumor necrosis factor-α (TNF-α) to pre-treat synovial tissue and fibroblast-like synoviocytes (FLS) to observe the effect of inflammatory cytokines on the synovial membrane before H/R. It was determined that H/R increased interleukin (IL)-1β and IL-6 expression levels in TNF-α-induced cell culture supernatants, increased the proportion of SA-β-gal staining, and increased the expression levels of high mobility group box 1, caspase-8, p16, p21, matrix metalloproteinase (MMP)-3 and MMP-13 in the synovium. Furthermore, H/R opened the mitochondrial permeability transition pore, caused the loss of mitochondrial membrane potential (ΔΨm) and increased the release of reactive oxygen species (ROS). Moreover, H/R caused the expansion of the mitochondrial matrix and rupture of the mitochondrial extracorporeal membrane, with a decrease in the number of cristae. In addition, H/R induced activation of the JNK signaling pathway in FLS to induce cell senescence. Thus, the present results indicated that H/R may cause inflammation and escalate synovial inflammation induced by TNF-α, which may lead to the pathogenesis of OA by increasing changes in synovial SASP and activating the JNK signaling pathway. Therefore, further studies expanding on the understanding of the pathogenesis of H/R etiology in OA are required.

Keywords: hypoxia/reoxygenation, senescence, mitochondria, JNK signaling pathway, synoviocytes, osteoarthritis

Introduction

Osteoarthritis (OA) is a severe degenerative disease involving multiple etiologies (1). Its main features include articular cartilage erosion, marginal bone hyperplasia, osteophyte formation, subchondral bone sclerosis, and varieties of biochemical and morphological changes in the synovium and joint cavity (2). OA lesions not only occur in the cartilage but also the entire synovial joint (3,4). However, previous studies investigating OA have focused on the role of cartilage (5), therefore synovial sourced pathology in the development of OA has not been fully examined. The physiological function of the synovium also plays a key role in maintaining a healthy joint (6). Moreover, nutrition and lubrication of the cartilage are supported by the synovium. Matrix conversion plays an important role in the joint microenvironment, and the synovial membrane can transform the matrix (7). Fibroblast-like synoviocytes (FLS) are located in the synovial lining layer and can secrete cytokines and catabolic factors, of which the latter can trigger articular cartilage degradation as a result of inflammatory trauma and oxidative stress (8). Synovial vascularization and synovial hyperplasia are observed in the early stage of OA (9). A previous morphological study of the OA synovium at different stages observed the accumulation of large amounts of cellulose in the synovium, which is related to disease severity (10). Moreover, synovial inflammation is an important driver of the early pathology in OA (11). Therefore, the synovial membrane is likely to be a potential target for OA prevention and treatment.

The joint is frequently located in a dynamic fluctuating oxygen environment (12). During daily activities, joints repeatedly undergo tissue hypoxia and reoxygenation (H/R) (13). H/R under physiological and pathological conditions has minor effects on hypoxic-tolerant chondrocytes, but may lead to respiratory dysfunction in aerobic synovial cells (14). Furthermore, overproduction of reactive oxygen species (ROS) is initiated by tissue swelling and temporary hypoxia. H/R can regulate the activity of inducible nitric oxide synthase (iNOS) and nitrous oxides, which are induced by interleukin (IL)-1β and tumor necrosis factor (TNF)-α in synovial cells under such pathological conditions (15). The local accumulation of free radicals participates in intracellular and extracellular oxidative damages, which compromise mitochondrial function, and thus a detrimental cycle is initiated in the joint (16).

Cellular senescence can be induced by a variety of stressors and different genotoxic stressors induce different phenotypes of cellular senescence (17). With aging, large numbers of senescent cells (SnCs) accumulate in the human body, which can induce a drastic modification in gene expression and secretion of multiple of factors to cause a senescence-associated secretory phenotype (SASP) (18,19). Furthermore, the actions of SnCs strengthen senescence via autocrine signaling, which stimulates neighboring cells to undergo senescence (18,19). When joint organs are unable to replace SnCs or reduce damage, intracellular damage accumulates and exerts deleterious effects on both the host cells and other cell types, which impairs their function and contributes to the advanced stage of OA (20). The SASP includes a varieties of chemical factors, pro-inflammatory factors, extracellular matrix-degrading proteins and growth factors, which play an important role in the local microenvironment of tissues (21–23). OA is a typical age-related disease, characterized by typical senescent features. Moreover, the characteristics of catabolic mediators and inflammation in the pathogenesis of OA are similar to those observed in ‘classic’ SnCs. The presence of inflammatory factors among the SASP phenotype can induce stress-induced premature senescence. Furthermore, SnCs can enhance the level of inflammation and form a positive feedback loop (24).

The JNK signaling pathway includes important members of the mitogen-activated protein kinase (MAPK) family. This pathway is widely involved in regulation of cell proliferation, metabolism, apoptosis and DNA damage repair (25–27). Furthermore, the JNK pathway can be activated by stress stimulation (28,29). Previous studies have shown that activation of the JNK signaling pathway is associated with senescence and various degenerative diseases (29–31). Since the JNK signaling pathway can regulate several inflammatory pathways, blocking this mechanism may effectively inhibit inflammation and prevent joint destruction in experimental models of arthritis (32,33). Therefore, the present study hypothesized that H/R activation of the JNK pathway in synovium may promote cell damage and senescence, which could lead to OA lesions.

Patients and methods

Patients and tissue

The present study collected synovial tissue specimens from 20 patients (age, 33–72 years; mean age, 52 years; men, 10; women, 10) each with acute knee injury and OA-total knee replacement in the Department of Orthopedics, Wuhan University People's Hospital within 4 h of acute knee joint trauma operation. The specimens were collected between September 2017 and January 2019. Prior to the study, all patients voluntarily agreed to participate. The present study was approved by the Ethics Committee of Renmin Hospital of Wuhan University.

Tissue mass culture

Tissues were soaked in PBS solution for 5 min and then rinsed thrice with PBS at room temperature. Then, the synovium was chopped into small pieces that were placed at 37°C in high glucose DMEM (Gibco; Thermo Fisher Scientific, Inc.) supplemented with 15% FBS (Gibco; Thermo Fisher Scientific, Inc.) and 1% penicillin/streptomycin in a humidified atmosphere containing 5% CO2. The medium was changed once after 3–4 days.

Culture and isolation of FLS

Fresh synovial tissue was soaked in PBS solution for 5 min and rinsed thrice with PBS. Fat and other fibrous tissue were removed and placed in a petri dish. The synovial was cut into pieces with ophthalmic shears and placed into a culture bottle. Then, 0.2% collagenase II (Sigma-Aldrich; Merck KGaA) with 10% FBS was added and placed into a CO2 incubator for digestion (37°C, 5% CO2). After digesting for 6 h, the supernatant was removed by centrifugation at 1,000 × g at 37°C for 5 min, and then 4 ml culture medium (15% FBS; 1% penicillin/streptomycin) was transferred into a clean culture bottle and cultured in an incubator (37°C, 5% CO2). The following day, the impurities were gently washed away with PBS buffer and replaced with DMEM containing 10% FBS and 1% mixture of penicillin and streptomycin. The medium was changed once every 2–3 days.

Hypoxia/reoxygenation (H/R) intervention, synovial tissue block and FLS experimental grouping

The patients were sub-divided into four groups: i) Control, with healthy synovium; ii) H/R intervention; iii) TNF-α (PeproTech, Inc.) intervention (20 ng/ml TNF-α incubated at 37°C for 24 h); and iv) H/R+TNF-α intervention, with healthy tissue mass incubated at 37°C with 20 ng/ml TNF-α for 24 h before H/R intervention. The normal culture conditions (5% CO2; 37°C) and hypoxic culture conditions (5% CO2; 1% O2; 37°C) were established by regulating several conventional cell incubators (14). The synovial tissue mass and FLS culture vessel were placed in anoxic conditions for 2 h and conventional conditions for 2 h, and this process was repeated for three cycles. The present study synchronously changed the liquid in each experimental group after 24 h in order to minimize the experimental errors among the groups.

Hematoxylin and eosin (H&E) staining

The cultured tissue block was embedded in paraffin and sliced at a thickness of 4 µm, and then rinsed with tap water at room temperature for 5 min. Tissues were differentiated with 1% hydrochloric acid and 75% alcohol for 3 sec, rinsed with water for 10 min at room temperature. Then, 0.5% alcohol-soluble eosin stain was added to stain for 30 sec at room temperature, and the sample was dehydrated with gradient ethanol (95 and 00%). After the xylene treatment became transparent for 1 min, the sample was sealed with neutral glue. The sample was observed under a light microscope at magnification, ×400.

Immunofluorescence and immunohistochemistry

The cultured tissue blocks were embedded in paraffin and sectioned at the thickness of 4 µm. Samples were fixed with 4% paraformaldehyde for 15 min and washed in PBS at room temperature. Then, samples were permeabilized with 5% BSA (Calico LLC) and 0.1% Triton X-100 for 1 h at room temperature. Subsequently, samples were incubated the following primary antibodies: Rabbit vimentin (1 mg/ml; Abcam; cat. no. ab63379), CD90 (1:100; Abcam; cat. no. ab125215), IL-1β (1:150; Abcam; cat. no. 1743-1), p16 (1:200; Abcam; cat. no. 1712-1) and matrix metalloproteinase-13 (MMP-13; 1:200; Abcam; cat. no. ab9128) at 4°C overnight. Samples were then incubated with anti-rabbit FITC (1:200; Abcam; cat. no. ab27912) and anti-rabbit CY3 (1:200; Abcam; cat. no. ab6939) conjugated secondary antibody at room temperature for 2 h. After washing with PBS, the sections were sealed with fluorescent sealing tablets and observed under an Olympus fluorescent microscope at magnification, ×400 (Olympus Corporation) after counterstaining with DAPI (Nanjing KeyGen Biotech Co. Ltd.), which was used to counterstain the nuclei for 5 min at room temperature.

ELISA

FLS were divided into the specified four groups. Cells and cell fragments were removed by centrifugation during the supernatant analysis, which was at 1,000 × g at room temperature for 15 min. ELISA kits (R&D Systems. Inc.) were used to assess the expression levels of IL-6 (R&D Systems, Inc.; cat. no. D6050) and IL-1β (R&D Systems, Inc.; cat no. DLB50) in cell culture supernatants according to the manufacturer's instructions.

Western blot analysis

High mobility group box 1 (HMGB1), caspase-8 (Casp8), p16, p21, matrix metalloproteinase (MMP)-3 and MMP-13 protein expression levels in FLS were analyzed by western blotting. After digested by 0.25% trypsin (Servicebio, Inc.) and centrifugation at 1,000 × g at room temperature for 5 min, FLS were collected and washed twice with PBS. Cell precipitation was collected by centrifugation at 1,000 × g at room temperature for 5 min. Phosphatase inhibitor: Protease inhibitor: RIPA lysate (Beyotime Institute of Biotechnology) was mixed at a ratio of (1:1:50) and added to cells for 30 min on ice. Total protein was collected by centrifugation for 15 min at 4°C 12,000 × g. For denaturation, proteins were boiled for 15 min at 100°C. A bicinchoninic acid kit was used to detect protein concentration (Beyotime Institute of Biotechnology). The aliquots of protein (40 µg per lane) were separated by SDS-PAGE on a 12% gel and then transferred to PVDF membranes. The membranes were blocked with 5% non-fat milk in TBST (0.05% Tween-20) for 1 h at 37°C. After being blocked, membranes were incubated overnight at 4°C with antibodies: HMGB1 (1:1,000; cat. no. ab77302; Abcam), Casp8 (1:1,000; cat. no. ab25901; Abcam), p16 (1:1,000; cat. no. ab211542; Abcam), p21 (1:1,000; cat. no. ab109520; Abcam), MMP-3 (1:1,000; cat. no. ab52915; Abcam), MMP-13 (1:1,000; cat. no. ab39012; Abcam) and GAPDH (1:5,000; cat. no. GB12002; Servicebio, Inc.). After incubation, the PVDF membranes were washed thrice with TBST buffer and incubated with horseradish peroxidase-conjugated goat anti-rabbit (cat. no. GB23303; Servicebio, Inc.; 1:3,000) secondary antibodies at room temperature for 1 h. After washing three times with TBST at 37°C for 30 min, a chemiluminescence luminol reagent (cat. no. G2014, Servicebio, Inc.) was used to visualize the protein bands using the Image Lab 5.2 quantitative assay system (Bio-Rad Laboratories, Inc.). The relative protein levels were determined by normalizing to GAPDH.

Reverse transcription-quantitative PCR (RT-qPCR)

TRIzol® reagent (Invitrogen; Thermo Fisher Scientific, Inc.) was used to extract total RNA from FLS. The RevertAid First Strand cDNA Synthesis kit (Fermentas; Thermo Fisher Scientific, Inc.) was used to reverse transcribe cDNA from the RNA. The cDNAs were produced with the kit and incubated at 37°C for 15 min and at 85°C for 5 sec. qPCR was carried out using Hieff qPCR SYBR Green Master Mix (No Rox; Shanghai Yeasen Biotechnology Co., Ltd.) and was performed on a StepOnePlus device (Applied Biosystems; Thermo Fisher Scientific, Inc.) with the following thermocycling conditions: Initial denaturation at 95°C for 10 sec, followed by 40 cycles at 95°C for 5 sec and at 60°C for 20 sec. The following primers were used: HMGB1 forward, 5′-ATGGGCAAAGGAGATCCTAA-3′ and reverse, 5′-TTAATCATCATCATCTTCTTCTTCA-3′; p16 Ink4a forward, 5′-GATCCAGGTGGGTAGAAGGTC-3′ and reverse, 5′-CCCCTGCAAACTTCGTCCT-3′; p21 forward, 5′-GCGATGGAACTTCGACTTTGT-3′ and reverse, 5′-GGGCTTCCTCTTGGAGAAGAT-3′; MMP-3 forward, 5′-GGGTGAGGACACCAGCATGA-3′ and reverse, 5′-CAGAGTGTCGGAGTCCAGCTTC-3′; MMP-13 forward, 5′-TTGAGGATACAGGCAAGACT-3′ and reverse, 5′-TGGAAGTATTACCCCAAATG-3′; IL-1β forward, 5′-AAACAGATGAAGTGCTCCTTCCAGG-3′ and reverse, 5′-TGGAGAACACCACTTGTTGCTCCA-3′; IL-6 forward, 5′-TGCTGGTGTGTGACGTTCCC-3′ and reverse, 5′-CCATCTTTGGAAGGTTCAGGTTG-3′; Casp8 forward, 5′-CGGGGTACCATGGACTTCAGCAGAAATC-3′ and reverse, 5′-TCAATCAGAAGGGAAGACAA-3′; JNK forward, 5′-ATGAGCAGAAGCAAGCGTGAC-3′ and reverse, 5′-CTGGGCTTTAAGTCCCGATG-3′; Bax forward, 5′-ACCAAGAAGCTGAGCGAGTGT-3′ and reverse, 5′-ACAAACATGGTCACGGTCTGC-3′; Bcl-2 forward, 5′-AGATGTCCAGCCAGCTGCAC-3′ and reverse, 5′-TGTTGACTTCACTTGTGGCC-3′; p53 forward, 5′-CAGCCAAGTCTGTGACTTGCACGTAC-3′ and reverse, 5′-CTATGTCGAAAAGTGTTTCTGTCATC-3′; and GAPDH forward, 5′-GAGTCAACGGATTTGGTCGT-3′ and reverse, 5′-TGAGGCCCAAGGCCACAGGTA-3′. GADPH was used as an internal reference. The 2−ΔΔCq method was used to calculate the relative mRNA expression levels (34).

Senescence-associated β-galactosidase (SA-β-gal) staining

According to the manufacturer's instructions, FLS with the cell density of 1×106 cells/well were washed twice and then fixed by adding 1.5 ml of 1X SA-β-gal fixative, followed by incubation for 10 min at 25°C. Then, the fixed cells were washed three times with PBS and stained using an SA-β-galactosidase staining kit (BioVision, Inc.; cat. no. K320-250). The fixed FLS were incubated overnight at 37°C. Then, cells were observed and image under a light microscope at magnification, ×200 (Olympus Corporation); SnCs were identified as blue-stained cells. Image-Pro Plus 6.0 (Media Cybernetics, Inc.) was used to analyze the number of positive cells in the sections.

Microscopic assessment of mitochondrial membrane potential (ΔΨm)

ΔΨm was evaluated using an ΔΨm assay kit (Beijing Solarbio Science & Technology Co., Ltd.; cat. no. M8650) with JC-1. FLS were washed with PBS and stained with 1 ml JC-1 staining solution for 20 min at 37°C. After staining, the ratio of red and green light was observed under a fluorescence microscope at magnification, ×200 after adding medium with 10% FBS.

Flow cytometric determination of ΔΨm

ΔΨm was determined using a JC-1 containing ΔΨm kit (Beijing Solarbio Science & Technology Co., Ltd.; cat. no. M8650). FLS were washed with PBS. After digestion using 0.25% trypsin (Servicebio, Inc.) and centrifugation at 1,000 × g at room temperature for 5 min, FLS were soaked at 37°C for 20 min with 800 µl of JC-1 working solution. After washing with PBS, FLS were resuspended in 1 ml JC-1buffer (1X) and measured by a flow cytometer FACSCalibur (Becton, Dickinson and Company). Then FlowJo 10 software was used for analysis (FlowJo LLC).

Detection of the openness of the mitochondrial permeability transition pore (MPTP)

The openness of MPTP was tested using an MPTP staining kit (BestBio Co., Ltd.; cat. no. BB-48122). After digestion with0.25% trypsin (Servicebio, Inc.) and centrifugation at 1,000 × g at room temperature for 5 min, 3 ml probe working solution (BBcellP robe™ CA1 Probe Diluted with 500X in 1X mPTP Staining Buffer and 5 ml fluorescence quencher agent) was added to each sample and incubated at 37°C in the dark for 15 min. After this step and after washing with 3 ml MPTP Staining Buffer (1X), FLS were suspended with 400 ml of Hanks Balanced Salt solution at room temperature. The openness of MPTP was calculated by measuring the fluorescence intensity of the sample by flow cytometry FACSCalibur (Becton, Dickinson and Company). Then FlowJo v10 software was used for analysis (FlowJo LLC).

Measurement of intracellular ROS

The amount of ROS produced in cells was measured by 2′,7′-dichlorodihydrofluorescein diacetate (DCHF-DA) according to the manufacturer's instructions. FLS cell culture medium was stained with 10 µm DCHF-DA (Invitrogen; Thermo Fisher Scientific, Inc.) for 2 h at 37°C. FLS samples were collected, washed twice with pre-chilled PBS and assayed by flow cytometry FACSCalibur (Becton Dickinson and Company). Then FlowJo v10 software was used for analysis (FlowJo LLC).

Ultrastructural detection of SnCs

The ultrastructure of cells was observed by transmission electron microscopy (TEM). Sections were sliced into 80 nm pieces and fixed in 2.5% glutaraldehyde solution at 4°C for >2 h. After being washed with PBS (pH 7.2), synoviocytes were fixed with 1% osmic acid at 4°C for 2 h and dehydrated with a series of ethanol concentrations (50, 70, 90 and 100%) for 10 min at 4°C. After being embedded in epoxy resin, stained with saturated uranium acetate for 30 min and lead citrate staining for 5–8 min, the synoviocytes were observed using a TEM (Hitachi, Ltd.) at magnification, ×100,000.

Statistical analysis

Data are expressed as the mean ± standard deviation for each group. Intra-group differences were assessed using Student's t-test and one-way analysis of variance using SPSS 16.0 software (SPSS, Inc.), followed by Bonferroni post-hoc correction for multiple testing using GraphPad Prism software (version 7.04; GraphPad Software, Inc.) P<0.05 was considered to indicate a statistically significant difference.

Results

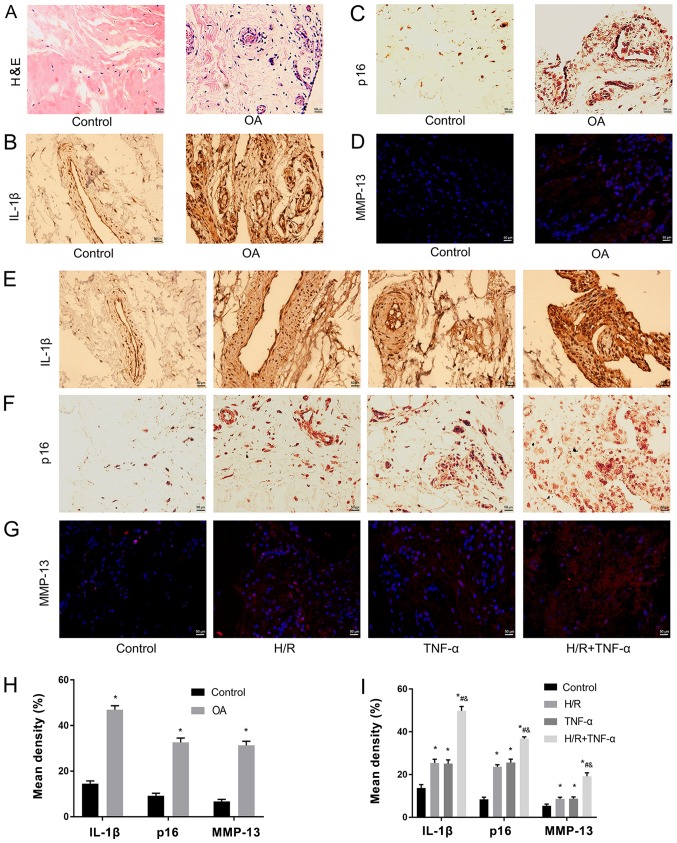

H/R increases TNF-α-induced IL-1β, P16 and MMP-13 in synovial tissue

Pathological and senescent phenotypic differences were assessed between healthy individuals and patients with OA. It was determined that expression levels of pathological and senescent markers in the synovial tissue mass before and after H/R were different. The experiment was divided into two stages. Firstly, the difference in synovial tissue masses from healthy controls and patients with OA were examined with H&E staining (Fig. 1A), and IL-1β (Fig. 1B), p16 (Fig. 1C) and MMP-13 (Fig. 1D) staining. It was revealed that the pathological features of H&E staining in OA tissues were more evident, compared with the healthy tissues (Fig. 1A). Furthermore, in the healthy tissue group, no inflammation, edema or other pathological changes were observed. However, in the OA group, synovial edema was clear and there were higher levels of inflammatory cell infiltration (Fig. 1A). Moreover, IL-1β, p16 and MMP-13 expression levels were significantly upregulated in the OA group (Fig. 1B-D). In the second stage, the experiment was divided into four groups. The present results indicated that the expression levels of IL-1β (Fig. 1E), p16 (Fig. 1F) and MMP-13 (Fig. 1G) were significantly increased after H/R compared with the control group (Fig. 1E-I).

Figure 1.

H/R increases TNF-α-induced IL-1β, p16 and MMP-13 in synovial tissue. (A) Pathological phenotypic H&E staining of health patients and patients with OA. Magnification, ×400. (B) Immunohistochemistry of IL-1β and (C) p16. Magnification, ×400. (D) Immunofluorescence was used to detect the expression level of MMP-13. Magnification, ×400. Expression levels of (E) IL-1β, (F) p16 and (G) MMP-13 as senescent phenotype markers in the normal synovium group, H/R group, TNF-α group and H/R + TNF-α group. (H) Quantitative analysis of the expression levels of IL-1β, p16 and MMP-13 in healthy individuals and patients with OA. Magnification, ×400. (I) Quantification of the expression levels of IL-1β, p16 and MMP-13 in the normal synovium group, H/R group, TNF-α group and H/R + TNF-α group. Data are presented as the mean ± SD. n=3. *P<0.05 vs. Control group; #P<0.05 vs. H/R group; &P<0.05 vs. TNF-α group. N=3. IL, interleukin; TNF-α, tumor necrosis factor α; MMP, matrix metalloproteinase; OA, osteoarthritis; H/R, Hypoxia/reoxygenation; H&E, hematoxylin and eosin.

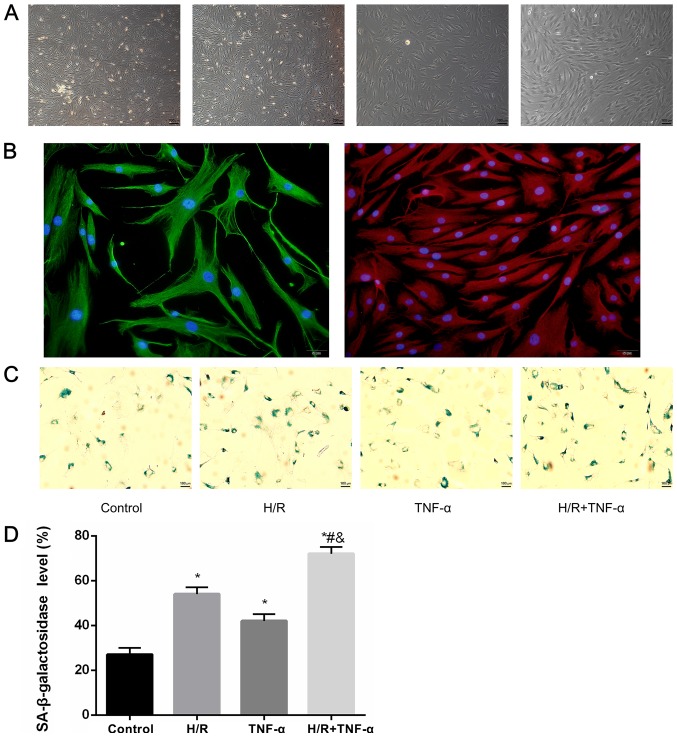

Primary culture of FLS, identification of cellular immunofluorescence and detection of SA-β-gal

It was demonstrated that most FLS extracted from the synovial tissue were spindle-shaped. After 4 days of growth, FLS were sub-passaged to the third generation at a ratio of 1:2 (Fig. 2A). Moreover, positive immunocytochemical identification of CD90 and vimentin protein staining was performed for the identification of FLS (Fig. 2B). In addition, the expression level of SA-β-gal in FLS after H/R was studied (Fig. 2C), and the positive cells (blue) expressing SA-β-galactosidase were quantitatively assessed (Fig. 2D). It was determined that the expression level SA-β-gal in FLS increased with H/R intervention compared to the control group. Furthermore, in the H/R + TNF-α group, the expression level of SA-β-gal was further increased compared with the control group, H/R group and TNF-α group, which indicated a larger proportion of senescent cells.

Figure 2.

Primary culture of FLS, identification of cellular immunofluorescence and detection of SA-β-gal. (A) FLS extracted from synovial; a large number of the FLS were spindle-shaped. Magnification, ×40. The 3–5 generation FLS had a uniform arc arrangement, which were fusiform. Magnification, ×100. (B) Positive expression of CD90, which stains red, vimentin, which stains green, and the nucleus, which stains blue. Magnification, ×200. (C) Detection of senescence marker SA-β-gal blue staining and (D) quantitative analysis of positive cells. Magnification, ×100. Data are presented as the mean ± SD. n=3. *P<0.05 vs. Control group; #P<0.05 vs. H/R group; &P<0.05 vs. TNF-α group. N=3. SA-β-gal, senescence-associated β-galactosidase; FLS, fibroblast-like synoviocytes; H/R, hypoxia/reoxygenation; TNF-α, tumor necrosis factor α.

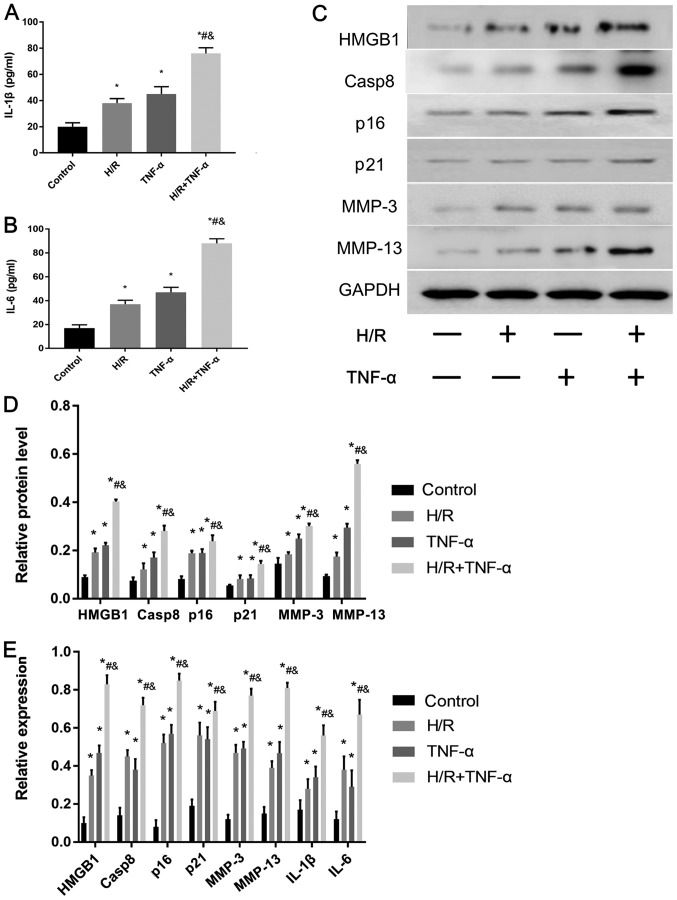

Relative expression levels of SASP proteins in FLS after H/R

The expression levels of the senescent phenotype proteins and inflammatory factors HMGB1, Casp8, p16, p21, MMP-3, MMP-13, IL-6 and IL-1β in FLS before and after H/R were studied. IL-1β (Fig. 3A) and IL-6 (Fig. 3B) levels in FLS were assessed using ELISA, and HMGB1, Casp8, p16, p21, MMP-3 and MMP-13 proteins were detected by western blotting (Fig. 3C and D). In addition, RT-qPCR was used to detect the mRNA expression levels of HMGB1, Casp8, p16, p21, MMP-3, MMP-13, IL-1β and IL-6 (Fig. 3E). The results indicated that the protein and mRNA expression levels of HMGB1, Casp8, p16, p21, MMP-3, MMP-13, IL-1β and IL-6 were significantly increased in the H/R environment compared with the control. Moreover, the expression levels of all these factors were further significantly increased after pre-incubation with TNF-α before 24 h of H/R compared with the control group, H/R group and TNF-α group.

Figure 3.

Effect of H/R on the expression levels of senescence-associated secretory phenotype-associated proteins in FLS. Protein expression levels of (A) IL-1β and (B) IL-6 protein levels in the cell supernatant were assessed and quantified. (C) Western blotting results indicated the expression levels of HMGB1, Casp8, p16, p21, MMP-3 and MMP-13. (D) Quantitative analysis of HMGB1, Casp8, p16, p21, MMP-3 and MMP-13 protein expression levels. (E) mRNA expression levels of HMGB1, Casp8, p16, p21, MMP-3, MMP-13, IL-6 and IL-1β were assessed by reverse transcription-quantitative PCR. Data are presented as the mean ± SD. *P<0.05 vs. Control group; #P<0.05 vs. H/R group; &P<0.05 vs. TNF-α group. N=3. FLS, fibroblast-like synoviocytes; H/R, hypoxia/reoxygenation; TNF-α, tumor necrosis factor α; IL, interleukin; MMP, matrix metalloproteinase; HMGB1, high mobility group box 1; Casp8, caspase-8.

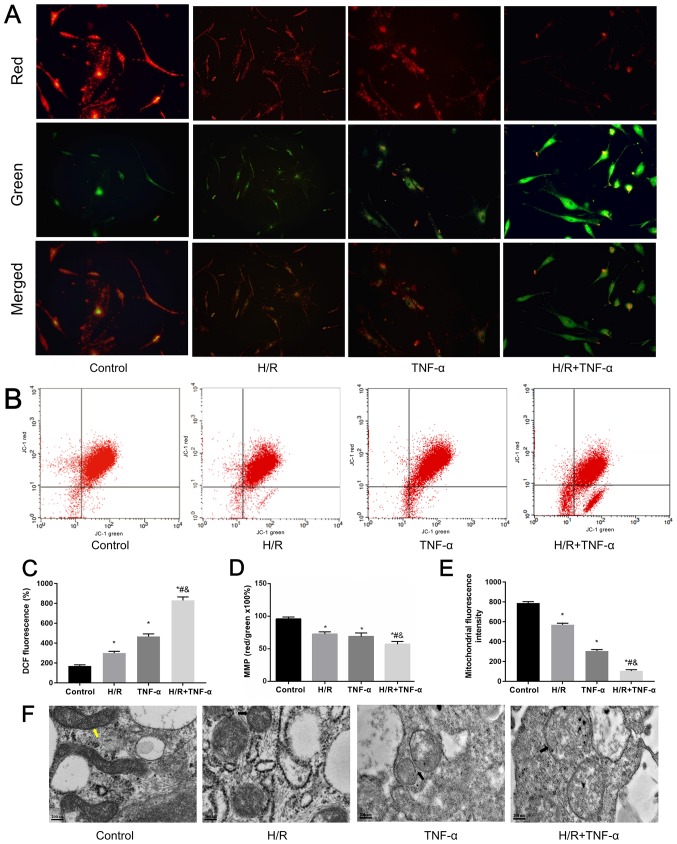

Mitochondrial dysfunction induced by H/R and its manifestations

H/R induces morphological changes and mitochondrial dysfunction in FLS (14). Furthermore, overproduction of ROS is the initial sign of cellular inflammation (35). The loss of ΔΨm and the opening of the MPTP often cause excessive accumulation of ROS, which significantly increases ROS levels in cells (36). Therefore, a JC-1 MMP assay kit was used to detect changes in ΔΨm in FLS under H/R conditions, where the red/green ratio decreased as the level of ΔΨm decreased (Fig. 4A). The changes in ΔΨm were detected by flow cytometry (Fig. 4B and D). It was demonstrated that H/R decreased ΔΨm. Moreover, flow cytometric results indicated that the MPTP in mitochondria was opened under H/R conditions in FLS (Fig. 4E). Flow cytometry was also used to estimate intracellular ROS levels by detecting the relative increase of fluorescent units after DCFH-DA staining. It was determined that H/R significantly increased intracellular ROS levels (Fig. 4C). In addition, changes in mitochondrial ultrastructure were observed under TEM; FLS morphology of the control group was normal as the mitochondria were rod-shaped and the mitochondrial ridges were clearly visible. Compared with the control group, small and short rod-shaped mitochondria were observed in the H/R group. Moreover, mitochondria ridges were ruptured and mitochondria became swollen in the TNF-α and TNF-α + H/R groups (Fig. 4F).

Figure 4.

Microscopic assessment of ΔΨm. (A) Changes in ΔΨm of intracellular mitochondria in FLS in the H/R environment were assessed by fluorescence microscopy. Magnification, ×200. (B) Flow cytometric analysis of ΔΨm. Red/Green × 100%. (C) Results of intracellular ROS analysis. (D) Analysis of ΔΨm. (E) Openness of the mitochondrial permeability transition pore was determined by the reduction of relative fluorescent units. (F) H/R affected the ultrastructure of FLS. Images revealed that mitochondria were swollen in the presence of cytokines and a H/R environment. Normal mitochondria were marked yellow and abnormal mitochondria were marked black. Magnification, ×100,000. Data are presented as the mean ± SD. *P<0.05 vs. Control group; #P<0.05 vs. H/R group; &P<0.05 vs. TNF-α group. N=3. ΔΨm, mitochondrial membrane potential; FLS, fibroblast-like synoviocytes; H/R, hypoxia/reoxygenation; TNF-α, tumor necrosis factor α.

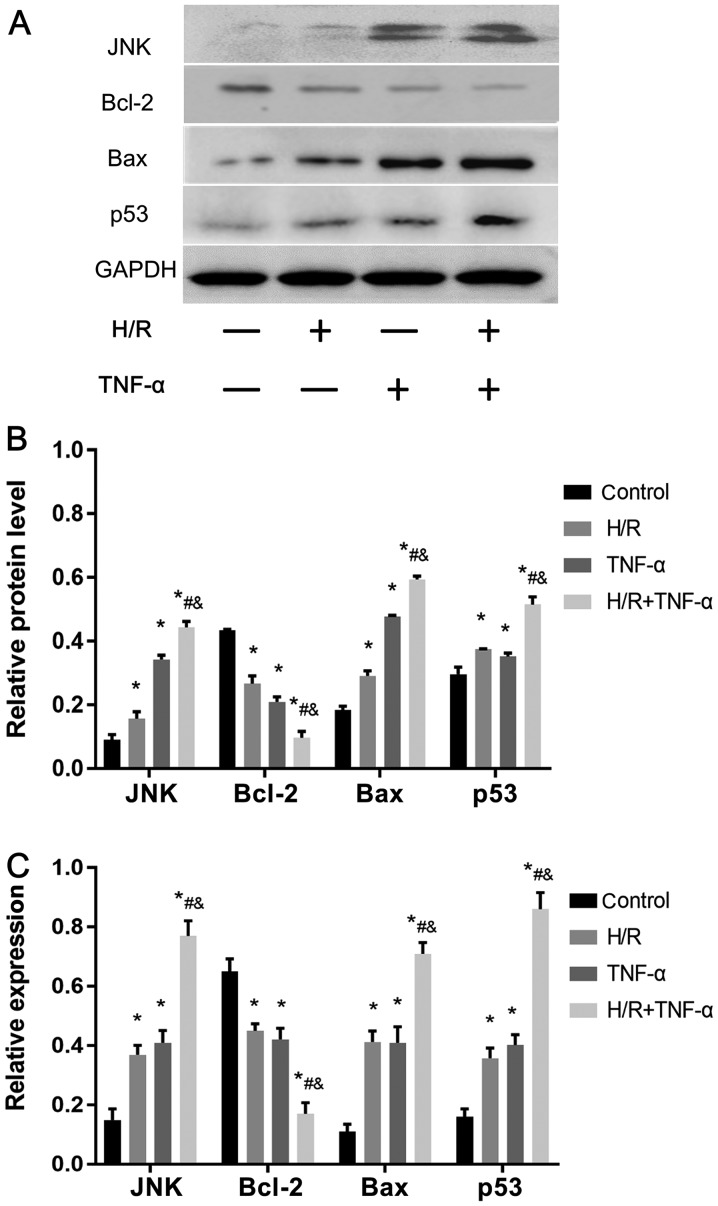

H/R-activates the JNK pathway to reduce Bcl-2 expression, and increase JNK, p53 and Bax expression levels to promote senescence

Western blotting was used to assess the protein expression levels of JNK, p53, Bcl-2 and Bax (Fig. 5A and B). In addition, the mRNA expression levels of JNK, p53, Bax and Bcl-2 were detected by RT-qPCR (Fig. 5C). It was demonstrated that, compared with the control group, H/R intervention decreased the expression level of Bcl-2, and enhanced the expression levels of JNK, p53 and Bax. Therefore, the present results indicated that H/R may be important in activating the JNK signaling pathway to promote senescence.

Figure 5.

H/R activates the JNK signaling pathway in FLS, promotes Bax and p53 expression level and decreases Bcl-2. (A) Protein expression levels of JNK, Bax, p53 and Bcl-2 in FLS. (B) Quantitative analysis of JNK, Bax, p53 and Bcl-2 protein expression levels. (C) mRNA expression levels of JNK, Bax, p53 and Bcl-2. Data are presented as the mean ± SD. *P<0.05 vs. Control group; #P<0.05 vs. H/R group; &P<0.05 vs. TNF-α group. N=3. FLS, fibroblast-like synoviocytes; H/R, hypoxia/reoxygenation; TNF-α, tumor necrosis factor α.

Discussion

The pathological structures involved in the development of OA include both the cartilage and the entire joint (2), among which the synovial membrane has an abundant blood supply that is oxygen-dependent (37,38). Therefore, due to the characteristics of the synovial blood supply, inflammatory cytokines in the circulation can accumulate in the synovium more frequently and earlier than chondrocytes (39).

Joint motion is an H/R process (40). Excessive H/R damage can cause damage to synovial cells that are sensitive to changes in oxygen concentration (15). Synovial cell stimulation induced by oxidative stress or excessive mechanical action primarily results in a SASP phenotype, via which the synovial membrane enters a ‘stress-induced senescence state’ that leads to the development of OA (41,42). The present study established a repetitive H/R environment to simulate mild hypoxia. Moreover, to improve the simulated OA environment and the experimental integrity, samples were pretreated with TNF-α prior to H/R induction, in order to detect the changes of inflammatory cytokines and SASP in FLS in a fluctuating oxygen environment.

Increases in inflammatory factors in the blood of the aging population is a marker of chronic, low-grade systemic inflammation related to senescence, and plays an important role in the occurrence and development of chronic senescence diseases (43). H/R can create a chronic anoxic environment in the joint organs (13,16). Furthermore, anoxia increases ROS levels in FLS, which leads to mitochondrial damage and induces the production of inflammatory factors (8). In addition, by inhibiting the synthesis of respiratory complexes III and IV in synovial cells, mitochondrial dysfunction is worsened and inflammation is escalated (44). OA synovial cells are special; in the context of excessive ROS, these cells may exhibit additional senescent characteristics (45). Moreover, SnCs secrete various factors to alter the SASP phenotype, which destroy the microenvironment of neighboring tissues, thus spreading the imbalance and dysfunction to the whole tissue, and ultimately triggering the onset of OA (46). The present results indicated that the pathological characteristics of synovial tissue in OA were clear. It was revealed that the expression levels of IL-1β, p16 and MMP-13 in the OA group and H/R intervention group exhibited a similar trend, and these secretions were greatly increased compared with the control group. In addition, the expression levels of SASP-related proteins and inflammatory factors were higher in cells cultured under a H/R environment, and the proportion of SA-β-gal-positive FLS was also higher compared with the control. It was demonstrated that TNF-α pre-intervention before H/R cοuld further increase the expression levels of SASP-related proteins and the proportion of SA-β-gal-positive FLS in a H/R environment. Collectively, the present results suggested that H/R induced FLS dysfunction, promoted SASP phenotype changes and consequently promoted senescence, and thus may play an important role in the development of OA lesions.

Mitochondria are the main target of oxidative stress and damages to mitochondrion in FLS in a hypoxic environment may be caused by repeated H/R (14). Furthermore, mitochondria are downstream of ROS stimulation (47). Continuous mitochondrial damage can increase ROS levels, and ROS stimulation can cause mitochondrial DNA damage, inflammatory cytokine release and DNA mutations (48). Moreover, certain inflammatory cytokines may cause permanent changes in the mitochondrial complex, thus these factors may lead to further dysfunction of mitochondrial activity (49). The accumulation of ROS acts as an intracellular signal, which locally produces oxygen free radicals that participate in intracellular and extracellular oxidative damage response, stimulate synovial cells, trigger the inflammatory response and lead to cartilage destruction by altering the extracellular matrix of cartilage tissue (16). ROS, ATP production, oxygen uptake and membrane potential, are important to maintain the mitochondrial redox balance (50). Accumulation of senescent mitochondria are associated with decreased membrane potential and simultaneously increased ROS levels, which contribute to organelle dysfunction (51). ROS can affect numerous cell signaling pathways, such as MAPK (52). The JNK signaling pathway is an important member of the MAPK family, which are widely involved in cellular processes, including cell proliferation, metabolism and DNA damage repair (53). JNK is located in the cytoplasm, and once the transcription factor is activated it will combine with the cis-acting element to increase gene expression, and it also has an important relationship with inflammation (54,55). It has been previously reported that senescence in numerous tissues involves the JNK signaling pathway (30,56). Moreover, JNK activity is an indicator of mitochondrial dysfunction in the liver of an elderly individual (57). Similarly, due to its role in stress responses, JNK is important in the development of age-related muscular degeneration (58). The present study revealed that H/R enhanced oxidative stress and increased ROS in FLS. Furthermore, as a result of JNK signaling pathway activation in FLS, it was demonstrated that the expression levels of p53 and Bax were promoted, and Bcl-2 was decreased. Therefore, this process may be an important contributor to the development of OA.

Previous studies investigating synovial-caused OA pathologies have several limitations (59–63): i) Cells are cultured only under normal oxygen partial pressure, thus physiological or pathological oxygen fluctuations are not considered; and ii) the effect on hypoxic tolerance of chondrocytes by fluctuating oxygen have been studied, while mitochondrial damage and respiratory dysfunction in oxygen dependent FLS have not been investigated in depth. Therefore, due to physiological and pathological H/R processes in joint organs, previous studies may have a certain level of bias (15). Therefore, synovial pathology is likely to be initiated prior to primary articular cartilage damage. The present study established a cycling hypoxic environment to observe the expression and effects of inflammatory mediators between senescence and OA in FLS (22). On the basis of previous studies on the pathophysiological mechanism of OA (64,65), the importance of synovial injury induced by H/R injury in the pathogenesis of OA was emphasized in the present study. It was revealed that H/R could damage the mitochondria of synovial cells, and subsequently upregulate the response of joint tissue structure to inflammatory factors and oxidative stress, resulting in great number of SnCs. Mitochondrial dysfunction and increased ROS production in SnCs can induce DNA damage in adjacent proliferating cells (33). In addition, SnCs secrete pro-inflammatory factors to alter SASP in synovial cells, destroy the tissue microenvironment, activate the JNK pathway, and promote cell senescence and apoptosis (30). Therefore, even if only a small proportion of SnCs exist, these can lead to the imbalance and dysfunction of the entire organ. Furthermore, these interactions escalate cell destruction and inflammation, further damaging dysfunctional chondrocytes and creating an irreversible vicious cycle, which eventually leads to advanced OA lesions (20).

In conclusion, the present results revealed that H/R can stimulate FLS to release inflammatory cytokines and increase the proportion of cells with senescent characters. Furthermore, the secretion of SASP-related and catabolic factors were elevated, together with dysfunction of mitochondria, by H/R intervention. This effect may be via the JNK signaling pathway, which will lead to synovium senescence. Therefore, the present results indicated that H/R may increase TNF-α-induced synovitis, and play an important role in inflammation-induction pathogenesis of OA. Thus, future studies should be performed to aid in the understanding of the role of H/R in the pathogenesis of OA.

Acknowledgements

The authors would like to acknowledge the help from Ms. Qiong Ding, Dr Pengchen Yu, Ms. Yingxia Jin and Ms. Lina Zhou (Central Laboratory, Renmin Hospital of Wuhan University) in assisting with the FCM analyses.

Funding

The present study was supported by The National Natural Science Foundation of China (grant no. 81171760) and The Natural Science Foundation of Hubei Province (grant no. ZRMS2017000057).

Availability of data and materials

The datasets used and/or analyzed during the current study are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

Authors' contributions

YZ and HL designed the research study. SZ, WC, GH, JL and MC performed the research and analyzed the data. YZ, HL and WC contributed the reagents or tools, and wrote the main manuscript text. All authors contributed to revising the manuscript. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Ethics approval and consent to participate

The present study was conducted in strict in accordance with the Helsinki Declaration. This project had approval from both the Wuhan University and Renmin Hospital of Wuhan University (Wuhan, China). All patients participating in the experiment have signed informed consent.

Patient consent for publication

Not applicable.

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

References

- 1.Xia B, Di Chen, Zhang J, Hu S, Jin H, Tong P. Osteoarthritis pathogenesis: A review of molecular mechanisms. Calcif Tissue Int. 2014;95:495–505. doi: 10.1007/s00223-014-9917-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Bijlsma JW, Berenbaum F, Lafeber FP. Osteoarthritis: An update with relevance for clinical practice. Lancet. 2011;377:2115–2126. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(11)60243-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Loeser RF, Goldring SR, Scanzello CR, Goldring MB. Osteoarthritis: A disease of the joint as an organ. Arthritis Rheum. 2012;64:1697–1707. doi: 10.1002/art.34453. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Scanzello CR, Goldring SR. The role of synovitis in osteoarthritis pathogenesis. Bone. 2012;51:249–257. doi: 10.1016/j.bone.2012.02.012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Charlier E, Deroyer C, Ciregia F, Malaise O, Neuville S, Plener Z, Malaise M, de Seny D. Chondrocyte dedifferentiation and osteoarthritis (OA) Biochem Pharmacol. 2019;165:49–65. doi: 10.1016/j.bcp.2019.02.036. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Nakamura H, Shimamura S, Yasuda S, Kono M, Kono M, Fujieda Y, Kato M, Oku K, Bohgaki T, Shimizu T, et al. Ectopic RASGRP2 (CalDAG-GEFI) expression in rheumatoid synovium contributes to the development of destructive arthritis. Ann Rheum Dis. 2018;77:1765–1772. doi: 10.1136/annrheumdis-2018-213588. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Chubinskaya S, Frank BS, Michalska M, Kumar B, Merrihew CA, Thonar EJ, Lenz ME, Otten L, Rueger DC, Block JA. Osteogenic protein 1 in synovial fluid from patients with rheumatoid arthritis or osteoarthritis: Relationship with disease and levels of hyaluronan and antigenic keratan sulfate. Arthritis Res Ther. 2006;8:R73. doi: 10.1186/ar1947. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Yin S, Zhang L, Ding L, Huang Z, Xu B, Li X, Wang P, Mao J. Transient receptor potential ankyrin 1 (trpa1) mediates il-1β-induced apoptosis in rat chondrocytes via calcium overload and mitochondrial dysfunction. J Inflamm (Lond) 2018;15:27. doi: 10.1186/s12950-018-0204-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Del RM MJ, Izquierdo E, Caja S, Usategui A, Santiago B, Galindo M, Pablos JL. Human inflammatory synovial fibroblasts induce enhanced myeloid cell recruitment and angiogenesis through a hypoxia-inducible transcription factor 1alpha/vascular endothelial growth factor-mediated pathway in immunodeficient mice. Arthritis Rheum. 2009;60:2926–2934. doi: 10.1002/art.24844. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Riis RG, Gudbergsen H, Simonsen O, Henriksen M, Al-Mashkur N, Eld M, Petersen KK, Kubassova O, Bay Jensen AC, Damm J, et al. The association between histological, macroscopic and magnetic resonance imaging assessed synovitis in end-stage knee osteoarthritis: A cross-sectional study. Osteoarthritis Cartilage. 2017;25:272–280. doi: 10.1016/j.joca.2016.10.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Wang Y, Liu Y, Fan Z, Liu D, Wang F, Zhou Y. IGFBP2 enhances adipogenic differentiation potentials of mesenchymal stem cells from Wharton's jelly of the umbilical cord via JNK and Akt signaling pathways. PLoS One. 2017;12:e184182. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0184182. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Mathy-Hartert M, Burton S, Deby-Dupont G, Devel P, Reginster JY, Henrotin Y. Influence of oxygen tension on nitric oxide and prostaglandin E2 synthesis by bovine chondrocytes. Osteoarthritis Cartilage. 2005;13:74–79. doi: 10.1016/j.joca.2004.09.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.June RK, Liu-Bryan R, Long F, Griffin TM. Emerging role of metabolic signaling in synovial joint remodeling and osteoarthritis. J Orthop Res. 2016;34:2048–2058. doi: 10.1002/jor.23420. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Zhou S, Wen H, Cai W, Zhang Y, Li H. Effect of hypoxia/reoxygenation on the biological effect of IGF system and the inflammatory mediators in cultured synoviocytes. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 2019;508:17–24. doi: 10.1016/j.bbrc.2018.11.099. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Chenevier-Gobeaux C, Simonneau C, Lemarechal H, Bonnefont-Rousselot D, Poiraudeau S, Rannou F, Ekindjian OG, Anract P, Borderie D. Effect of hypoxia/reoxygenation on the cytokine-induced production of nitric oxide and superoxide anion in cultured osteoarthritic synoviocytes. Osteoarthritis Cartilage. 2013;21:874–881. doi: 10.1016/j.joca.2013.03.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Grishko VI, Ho R, Wilson GL, Pearsall AW IV. Diminished mitochondrial DNA integrity and repair capacity in OA chondrocytes. Osteoarthritis Cartilage. 2009;17:107–113. doi: 10.1016/j.joca.2008.05.009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Toussaint O, Dumont P, Dierick JF, Pascal T, Frippiat C, Chainiaux F, Magalhaes JP, Eliaers F, Remacle J. Stress-induced premature senescence as alternative toxicological method for testing the long-term effects of molecules under development in the industry. Biogerontology. 2000;1:179–183. doi: 10.1023/A:1010035712199. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Campisi J. Senescent cells, tumor suppression, and organismal aging: Good citizens, bad neighbors. Cell. 2005;120:513–522. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2005.02.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Campisi J. Aging, cellular senescence, and cancer. Annu Rev Physiol. 2013;75:685–705. doi: 10.1146/annurev-physiol-030212-183653. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Peilin W, Songsong T, Chengyu Z, Zhi C, Chunhui M, Yinxian Y, Lei Z, Min M, Zongyi W, Mengkai Y, et al. Directed elimination of senescent cells attenuates development of osteoarthritis by inhibition of c-IAP and XIAP. Biochim Biophys Acta Mol Basis Dis. 2019;1865:2618–2632. doi: 10.1016/j.bbadis.2019.05.017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Koobatian MT, Liang MS, Swartz DD, Andreadis ST. Differential effects of culture senescence and mechanical stimulation on the proliferation and leiomyogenic differentiation of MSC from different sources: Implications for engineering vascular grafts. Tissue Eng Part A. 2015;21:1364–1375. doi: 10.1089/ten.tea.2014.0535. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Biniecka M, Kennedy A, Fearon U, Ng CT, Veale DJ, O'Sullivan JN. Oxidative damage in synovial tissue is associated with in vivo hypoxic status in the arthritic joint. Ann Rheum Dis. 2010;69:1172–1178. doi: 10.1136/ard.2009.111211. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Krizhanovsky V, Yon M, Dickins RA, Hearn S, Simon J, Miething C, Yee H, Zender L, Lowe SW. Senescence of activated stellate cells limits liver fibrosis. Cell. 2008;134:657–667. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2008.06.049. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Baker DJ, Wijshake T, Tchkonia T, LeBrasseur NK, Childs BG, van de Sluis B, Kirkland JL, van Deursen JM. Clearance of p16Ink4a-positive senescent cells delays ageing-associated disorders. Nature. 2011;479:232–236. doi: 10.1038/nature10600. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Acosta JC, Banito A, Wuestefeld T, Georgilis A, Janich P, Morton JP, Athineos D, Kang TW, Lasitschka F, Andrulis M, et al. A complex secretory program orchestrated by the inflammasome controls paracrine senescence. Nat Cell Biol. 2013;15:978–990. doi: 10.1038/ncb2784. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Basu S, Rajakaruna S, Reyes B, Van Bockstaele E, Menko AS. Suppression of MAPK/JNK-MTORC1 signaling leads to premature loss of organelles and nuclei by autophagy during terminal differentiation of lens fiber cells. Autophagy. 2014;10:1193–1211. doi: 10.4161/auto.28768. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Wang X, Hunter DJ, Jin X, Ding C. The importance of synovial inflammation in osteoarthritis: Current evidence from imaging assessments and clinical trials. Osteoarthritis Cartilage. 2018;26:165–174. doi: 10.1016/j.joca.2017.11.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Yao Y, Chen R, Ying C, Zhang G, Rui T, Tao A. Interleukin-33 attenuates doxorubicin-induced cardiomyocyte apoptosis through suppression of ASK1/JNK signaling pathway. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 2017;493:1288–1295. doi: 10.1016/j.bbrc.2017.09.153. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Kyriakis JM, Avruch J. Mammalian mitogen-activated protein kinase signal transduction pathways activated by stress and inflammation. Physiol Rev. 2001;81:807–869. doi: 10.1152/physrev.2001.81.2.807. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Yang LW, Song M, Li YL, Liu YP, Liu C, Han L, Wang ZH, Zhang W, Xing YQ, Zhong M. L-Carnitine inhibits the senescence-associated secretory phenotype of aging adipose tissue by JNK/p53 pathway. Biogerontology. 2019;20:203–211. doi: 10.1007/s10522-018-9787-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Das M, Jiang F, Sluss HK, Zhang C, Shokat KM, Flavell RA, Davis RJ. Suppression of p53-dependent senescence by the JNK signal transduction pathway. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2007;104:15759–15764. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0707782104. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Lanna A, Gomes DC, Muller-Durovic B, McDonnell T, Escors D, Gilroy DW, Lee JH, Karin M, Akbar AN. A sestrin-dependent Erk-Jnk-p38 MAPK activation complex inhibits immunity during aging. Nat Immunol. 2017;18:354–363. doi: 10.1038/ni.3665. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Nelson G, Wordsworth J, Wang C, Jurk D, Lawless C, Martin-Ruiz C, von Zglinicki T. A senescent cell bystander effect: Senescence-induced senescence. Aging Cell. 2012;11:345–349. doi: 10.1111/j.1474-9726.2012.00795.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Livak KJ, Schmittgen TD. Analysis of relative gene expression data using real-time quantitative PCR and the 2(-Delta Delta C(T)) method. Methods. 2001;25:402–408. doi: 10.1006/meth.2001.1262. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Xia G, Wang X, Sun H, Qin Y, Fu M. Carnosic acid (CA) attenuates collagen-induced arthritis in db/db mice via inflammation suppression by regulating ROS-dependent p38 pathway. Free Radic Biol Med. 2017;108:418–432. doi: 10.1016/j.freeradbiomed.2017.03.023. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Xin R, Pan YL, Wang Y, Wang SY, Wang R, Xia B, Qin RN, Fu Y, Wu YH. Nickel-refining fumes induce NLRP3 activation dependent on mitochondrial damage and ROS production in Beas-2B cells. Arch Biochem Biophys. 2019;676:108148. doi: 10.1016/j.abb.2019.108148. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Kim JH, Jeon J, Shin M, Won Y, Lee M, Kwak JS, Lee G, Rhee J, Ryu JH, Chun CH, Chun JS. Regulation of the catabolic cascade in osteoarthritis by the zinc-ZIP8-MTF1 axis. Cell. 2014;156:730–743. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2014.01.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.de Lange-Brokaar BJ, Ioan-Facsinay A, van Osch GJ, Zuurmond AM, Schoones J, Toes RE, Huizinga TW, Kloppenburg M. Synovial inflammation, immune cells and their cytokines in osteoarthritis: A review. Osteoarthritis Cartilage. 2012;20:1484–1499. doi: 10.1016/j.joca.2012.08.027. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Mathiessen A, Conaghan PG. Synovitis in osteoarthritis: Current understanding with therapeutic implications. Arthritis Res Ther. 2017;19:18. doi: 10.1186/s13075-017-1229-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Schneider N, Mouithys-Mickalad AL, Lejeune JP, Deby-Dupont GP, Hoebeke M, Serteyn DA. Synoviocytes, not chondrocytes, release free radicals after cycles of anoxia/re-oxygenation. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 2005;334:669–673. doi: 10.1016/j.bbrc.2005.06.147. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Harper ME, Bevilacqua L, Hagopian K, Weindruch R, Ramsey JJ. Ageing, oxidative stress, and mitochondrial uncoupling. Acta Physiol Scand. 2004;182:321–331. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-201X.2004.01370.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Musumeci G, Szychlinska MA, Mobasheri A. Age-related degeneration of articular cartilage in the pathogenesis of osteoarthritis: Molecular markers of senescent chondrocytes. Histol Histopathol. 2015;30:1–12. doi: 10.7243/2055-091X-2-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Schulz E, Wenzel P, Munzel T, Daiber A. Mitochondrial redox signaling: Interaction of mitochondrial reactive oxygen species with other sources of oxidative stress. Antioxid Redox Signal. 2014;20:308–324. doi: 10.1089/ars.2012.4609. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Cillero-Pastor B, Martin MA, Arenas J, López-Armada MJ, Blanco FJ. Effect of nitric oxide on mitochondrial activity of human synovial cells. BMC Musculoskelet Disord. 2011;12:42. doi: 10.1186/1471-2474-12-42. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Lepetsos P, Papavassiliou AG. ROS/oxidative stress signaling in osteoarthritis. Biochim Biophys Acta. 2016;1862:576–591. doi: 10.1016/j.bbadis.2016.01.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Passos JF, Nelson G, Wang C, Richter T, Simillion C, Proctor CJ, Miwa S, Olijslagers S, Hallinan J, Wipat A, et al. Feedback between p21 and reactive oxygen production is necessary for cell senescence. Mol Syst Biol. 2010;6:347. doi: 10.1038/msb.2010.5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Strandberg TE, Tilvis RS. C-reactive protein, cardiovascular risk factors, and mortality in a prospective study in the elderly. Arterioscler Thromb Vasc Biol. 2000;20:1057–1060. doi: 10.1161/01.ATV.20.4.1057. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Kaarniranta K, Pawlowska E, Szczepanska J, Jablkowska A, Blasiak J. Role of Mitochondrial DNA Damage in ROS-mediated pathogenesis of age-related macular degeneration (AMD) Int J Mol Sci. 2019;20(pii):E2374. doi: 10.3390/ijms20102374. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Shay JW, Wright WE. Hayflick, his limit, and cellular ageing. Nat Rev Mol Cell Biol. 2000;1:72–76. doi: 10.1038/35036093. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Dalle PP, Nelson G, Otten EG, Korolchuk VI, Kirkwood TB, von Zglinicki T, Shanley DP. Dynamic modelling of pathways to cellular senescence reveals strategies for targeted interventions. PLoS Comput Biol. 2014;10:e1003728. doi: 10.1371/journal.pcbi.1003728. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Dhawan P, Richmond A. A novel NF-kappa B-inducing kinase-MAPK signaling pathway up-regulates NF-kappa B activity in melanoma cells. J Biol Chem. 2002;277:7920–7928. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M112210200. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Schattauer SS, Bedini A, Summers F, Reilly-Treat A, Andrews MM, Land BB, Chavkin C. Reactive oxygen species (ROS) generation is stimulated by κ opioid receptor activation through phosphorylated c-Jun N-terminal kinase and inhibited by p38 mitogen-activated protein kinase (MAPK) activation. J Biol Chem. 2019;294:16884–16896. doi: 10.1074/jbc.RA119.009592. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Craig R, Larkin A, Mingo AM, Thuerauf DJ, Andrews C, McDonough PM, Glembotski CC. p38 MAPK and NF-kappa B collaborate to induce interleukin-6 gene expression and release. Evidence for a cytoprotective autocrine signaling pathway in a cardiac myocyte model system. J Biol Chem. 2000;275:23814–23824. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M909695199. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Lories RJ, Derese I, Luyten FP, de Vlam K. Activation of nuclear factor kappa B and mitogen activated protein kinases in psoriatic arthritis before and after etanercept treatment. Clin Exp Rheumatol. 2008;26:96–102. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Hsieh CC, Rosenblatt JI, Papaconstantinou J. Age-associated changes in SAPK/JNK and p38 MAPK signaling in response to the generation of ROS by 3-nitropropionic acid. Mech Ageing Dev. 2003;124:733–746. doi: 10.1016/S0047-6374(03)00083-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Kanatsu-Shinohara M, Yamamoto T, Toh H, Kazuki Y, Kazuki K, Imoto J, Ikeo K, Oshima M, Shirahige K, Iwama A, et al. Aging of spermatogonial stem cells by Jnk-mediated glycolysis activation. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2019;116:16404–16409. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1904980116. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Ge HX, Zou FM, Li Y, Liu AM, Tu M. JNK pathway in osteoarthritis: Pathological and therapeutic aspects. J Recept Signal Transduct Res. 2017;37:431–436. doi: 10.1080/10799893.2017.1360353. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Twumasi-Boateng K, Wang TW, Tsai L, Lee KH, Salehpour A, Bhat S, Tan MW, Shapira M. An age-dependent reversal in the protective capacities of JNK signaling shortens Caenorhabditis elegans lifespan. Aging Cell. 2012;11:659–667. doi: 10.1111/j.1474-9726.2012.00829.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Olivotto E, Merli G, Assirelli E, Cavallo C, Belluzzi E, Ramonda R, Favero M, Filardo G, Roffi A, Kon E, Grigolo B. Cultures of a human synovial cell line to evaluate platelet-rich plasma and hyaluronic acid effects. J Tissue Eng Regen Med. 2018;12:1835–1842. doi: 10.1002/term.2704. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Huhtakangas JA, Veijola J, Turunen S, Karjalainen A, Valkealahti M, Nousiainen T, Yli-Luukko S, Vuolteenaho O, Lehenkari P. 1,25(OH)2D3 and calcipotriol, its hypocalcemic analog, exert a long-lasting anti-inflammatory and anti-proliferative effect in synoviocytes cultured from patients with rheumatoid arthritis and osteoarthritis. J Steroid Biochem Mol Biol. 2017;173:13–22. doi: 10.1016/j.jsbmb.2017.01.017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Zhang L, Zhang L, Huang Z, Xing R, Li X, Yin S, Mao J, Zhang N, Mei W, Ding L, Wang P. Increased HIF-1α in Knee Osteoarthritis aggravate synovial fibrosis via fibroblast-like synoviocyte pyroptosis. Oxid Med Cell Longev. 2019;2019:6326517. doi: 10.1155/2019/6326517. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Hsu HC, Chang WM, Wu JY, Huang CC, Lu FJ, Chuang YW, Chang PJ, Chen KH, Hong CZ, Yeh RH, et al. Folate deficiency triggered apoptosis of synoviocytes: Role of overproduction of reactive oxygen species generated via NADPH Oxidase/Mitochondrial Complex II and calcium perturbation. PLoS One. 2016;11:e146440. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0146440. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Gale AL, Mammone RM, Dodson ME, Linardi RL, Ortved KF. The effect of hypoxia on chondrogenesis of equine synovial membrane-derived and bone marrow-derived mesenchymal stem cells. BMC Vet Res. 2019;15:201. doi: 10.1186/s12917-019-1954-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Fernandes JC, Martel-Pelletier J, Pelletier JP. The role of cytokines in osteoarthritis pathophysiology. Biorheology. 2002;39:237–246. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Park J, Lee J, Kim KI, Lee J, Jang S, Choi HT, Son Y, Kim HJ, Woo EJ, Lee E, Oh TI. A pathophysiological validation of collagenase II-induced biochemical osteoarthritis animal model in rabbit. Tissue Eng Regen Med. 2018;15:437–444. doi: 10.1007/s13770-018-0124-z. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Data Availability Statement

The datasets used and/or analyzed during the current study are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.