Dear Editor,

Diffuse large B-cell lymphoma (DLBCL) is the most common lymphoma worldwide. A prevalence of 30–40% is estimated.1 In Chile, a frequency of 38.5% has been reported.2 It comprises a heterogeneous group of lymphomas, from a clinical, morphological and molecular point of view. Therefore, its prognosis is very variable. To predict the clinical risk, the “International Prognostic Index” (IPI) score3 and, more recently, the R (revised)-IPI are used.4 Recently, it has been shown that molecular factors, that are independent from these clinical scores, could better characterize this group of lymphomas, especially in the era of rituximab. However, molecular studies are not readily available tests in most centers in Latin America. Immunohistochemistry (IHC) is therefore a relatively easy and accessible technique.

We performed a retrospective study to characterize patients with de novo DLBCL treated with R-CHOP at our institution, between 2015 and 2016, according to the expression of MYC, BCL2, and/or BCL6 by IHC; and then evaluated survival outcomes among them.

The patients were classified as double or triple expressors (DE or TE) if they showed overexpression of MYC ≥40%, and BCL-2 or BCL-6 ≥50%, according to recommendations of the World Health Organization (WHO) 2016.5 The samples were reviewed by two independent pathologists (PV and CJ).

We excluded patients treated with chemotherapy other than R-CHOP, patients with relapsed DLBCL, DLBCL transformed from indolent lymphomas, patients with primary mediastinal DLBCL, patients with extranodal primary lymphomas, such as CNS, testicle, bone or gastric lymphomas and patients with concurrent HIV infection.

Finally, 53 patients were analyzed. The patient characteristics are shown in Table 1. The median age was 66 years, ranging between 28 and 81 years. Sixty-eight percent were women, 68% in stage III or IV, with a high-risk RIPI in 40%. Four (7.5%) were DE and 5 (9%), TE.

Table 1.

Epidemiological and clinical characteristics of the cohort; comparison between both, the double or triple Expressors (DE, TE) and the “Non-Expressors” groups.

| DE or TE | Non-Expressors | Total | p-Value | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| n = 9 | n = 44 | n = 53 | ||

| Male | 4 (44%) | 15 (34%) | 19 (36%) | 0.7 |

| Female | 5 (56%) | 29 (66%) | 34 (64%) | |

| CG | 8 (89%) | 25 (57%) | 33 (62%) | 0.12 |

| ABC | 1 (11%) | 19 (43%) | 20 (38%) | |

| Age | 66 | 67 | 66 (28–81) | 0.55 |

| High-risk R-IPI | 6 (67%) | 15 (34%) | 21 (40%) | 0.13 |

| Median LDH (U/L) | 1112 | 355 | 486 | 0.009 |

| Ann Arbor stage | ||||

| III | 1 (11%) | 12 (27%) | 13 (25%) | 1.00 |

| IV | 5 (56%) | 18 (41%) | 23 (42%) | |

| CR | 4 (44%) | 27 (61%) | 31 (58%) | 0.46 |

| Refractory | 5 (56%) | 17 (39%) | 22 (32%) | |

| Relapsed | 2 (50%) | 1 (3%) | 3 (9%) | 0.03 |

| Mortality | 7 (77%) | 17 (39%) | 24 (45%) | 0.06 |

Bold text indicates a statistically significant difference.

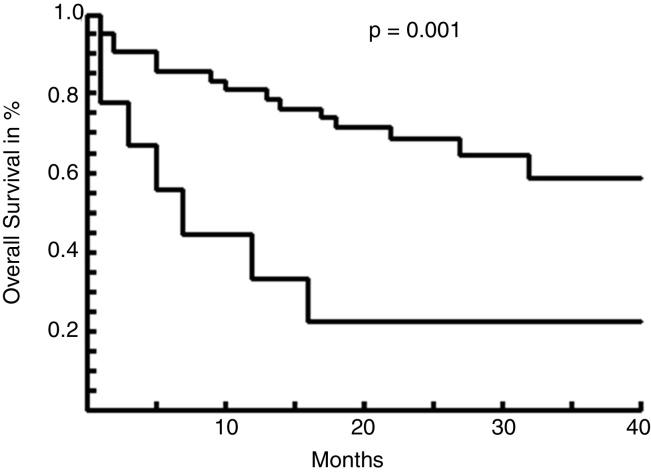

We found a statistically significant difference between these 2 groups, regarding LDH levels and relapse rates. The median follow-up was 19 months. The 3-year overall survival (OS) of the DE + TE patients vs those “not expressors” was 22% vs 58%, respectively, with a median survival of 5 months vs not reached (p = 0.001) (Figure 1).

Figure 1.

Overall survival curves between DT or TE vs “Non-Expressors” (NE).

Our study confirmed a worse survival rate for DE or TE DLBCL in our patients.

Several studies have correlated DE or TE lymphomas with worse prognosis and poor response to the standard chemotherapy RCHOP.6, 7, 8 This could explain the higher LDH levels and the higher relapse rate in these patients. Green et al.9 reported 29% of DE in 193 DLBCL patients, and a lower progression-free survival (PFS) and OS at 3 years in this group. Hu et al.10 reported a frequency of 34% of DE lymphomas in 466 DLBCL patients and showed a 5-year PFS of the DE vs non-DE patients of 27 vs 73%, and a 5-year OS of 30 vs 75%, respectively.

Currently, in the Chilean public health system, patients with DE or TE lymphomas are treated in the same way as any DLBCL, with R-CHOP chemotherapy. Our results suggest we must find a more effective treatment for these patients.

This series has obvious limitations, such as the small number of patients and short follow-up. Nevertheless, we think it is important to report it because of the substantial outcome differences observed.

Conflicts of interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- 1.Armitager J. A clinical evaluation of the International Lymphoma Study Group classification of non-Hodgkin's lymphoma. The Non-Hodgkin's Lymphoma Classification Project. Blood. 1997;89(11):3909–3918. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Cabrera M.E., Martinez V., Nathwani B.N., Muller-Hermelink H.K., Diebold J., Maclennan K.A. Non-Hodgkin lymphoma in Chile: a review of 207 consecutive adult cases by a panel of five expert hematopathologists. Leuk Lymphoma. 2012;53:1311–1317. doi: 10.3109/10428194.2012.654471. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Shipp M.A., Harrington D.P., Anderson J.R., Armitage J.O., Bonadonna G., Brittinger G. A predictive model for aggressive non-Hodgkin's lymphoma. N Engl J Med. 1993;329(14):987–994. doi: 10.1056/NEJM199309303291402. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Sehn L.H., Berry B., Chhanabhai M., Fitzgerald C., Gill K., Hoskins P. The revised International Prognostic Index (R-IPI) is a better predictor of outcome than the standard IPI for patients with diffuse large B-cell lymphoma treated with R-CHOP. Blood. 2007;109:1857–1861. doi: 10.1182/blood-2006-08-038257. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Swerdlow S.H., Campo E., Pileri S.A., Harris N.L., Stein H., Siebert R. The 2016 revision of the World Health Organization classification of lymphoid neoplasms. Blood. 2016;127:2375–2390. doi: 10.1182/blood-2016-01-643569. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Agarwal R., Lade S., Liew D., Rogers T.M., Byrne D., Feleppa F. Role of immunohistochemistry in the era of genetic testing in MYC-positive aggressive B-cell lymphomas: a study of 209 cases. J Clin Pathol. 2016;69(3):266–270. doi: 10.1136/jclinpath-2015-203002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Scott D.W., Mottok A., Ennishi D., Wright G.W., Farinha P., Ben-Neriah S. Prognostic significance of diffuse large B-cell lymphoma cell of origin determined by digital gene expression in formalin-fixed paraffin-embedded tissue biopsies. J Clin Oncol. 2015;33:2848–2856. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2014.60.2383. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Green T.M., Nielsen O., de Stricker K., Xu-Monette Z.Y., Young K.H., Møller M.B. High levels of nuclear MYC protein predict the presence of MYC rearrangement in diffuse large B-cell lymphoma. Am J Surg Pathol. 2012;36(4):612–619. doi: 10.1097/PAS.0b013e318244e2ba. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Green T.M., Young K.H., Visco C., Xu-Monette Z.Y., Orazi A., Go R.S. Immunohistochemical double hit score is a strong predictor of outcome in patients with diffuse large B-cell lymphoma treated with rituximab plus cyclophosphamide, doxorubicin, vincristine, and prednisone. J Clin Oncol. 2012;30(28):3460–3467. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2011.41.4342. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Hu S., Xu-Monette Z.Y., Tzankov A., Green T., Wu L., Balasubramanyam A. MYC/BCL2 protein coexpression contributes to the inferior survival of activated B-cell subtype of diffuse large B-cell lymphoma and demonstrates high risk gene expression signatures: a report from The International DLBCL Rituximab-CHOP. Blood. 2013;121(20):4021–4031. doi: 10.1182/blood-2012-10-460063. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]