Abstract

The ability to identify and label emotions may represent an early-life risk factor that relates to excess weight gain during childhood. The current study investigates the relationships between preschool emotion identification and early adolescent body mass index (BMI), as well as the mediating role of two variables: depressive symptoms and peer relations. In a longitudinal study, preschoolers completed an emotion identification task, and parents completed psychiatric assessments and a peer-relations questionnaire about their child. BMI percentile was measured at later time points in early adolescence. Poor emotion identification during preschool predicted increases in BMI percentile over time, with greater deficits in emotion identification ability relating to steeper increases in BMI percentile across early adolescence. Peer relations in preschool partially mediated the relationship between preschool emotion identification ability and adolescent BMI. This study provides novel information about potential targets for early interventions in the service of obesity prevention.

Keywords: Emotion identification, Depression, Peer relations, Obesity, Preschool

Obesity in adolescence often persists into later life and creates risk for adverse health outcomes [1–3]. Current treatments of obesity largely focus on lifestyle changes and are minimally effective [4]. Since obesity is difficult to treat once established, prevention may provide a more promising therapeutic avenue [5] if early-life modifiable risk factors for obesity could be identified. Early childhood may be a particularly valuable time for intervention, given the potential for greater neuroplasticity of the developing brain.

Previous work relates early-life emotion identification, the ability to accurately label facial emotions, to weight status and increases in body mass index (BMI) across development [6–9]. Specifically, while one study observed no differences between youth with obesity and youth of normal weight in emotion identification ability [10], three other cross sectional studies found that children with overweight or obesity were less accurate than children of lower weight in naming the emotions displayed by others [6, 8, 9]. Further, preliminary longitudinal research links such deficient abilities to increases in BMI across childhood [7]. Thus, existing research relates emotion identification ability to obesity.

Compared to findings on this bivariate association, less is known about the developmental relationships among a web of risk factors potentially related to both emotion identification and obesity. Of note, early-life emotion identification can be identified as young as 3 months old [11]. As such, difficulties in this skill may initiate a pathway toward obesity through associations with other, modifiable, later manifesting risk factors, specifically depressive symptoms and peer relations, each of which could provide a target for prevention efforts.

Depressive symptoms could be one possible mediator of the relationship between emotion identification and BMI. Consistent with this possibility, many studies find emotion identification deficits in Major Depressive Disorder [12–14]. Moreover, some, but not all [15], studies find that Major Depressive Disorder in childhood predicts high BMI in adulthood [16]. Finally, differences in emotion identification have been identified in youth at high-risk for depression [17], suggesting that emotion identification difficulties may predict risk trajectory of depression and persistence of depression over time [18].

As with depressive symptoms, poor peer relations may represent another potential mediator of the relationship between emotion identification and BMI. Indeed, independent lines of research link poor peer relations to emotion identification deficits in children [19] and increases in weight status [20–22]. Similarly to depressive symptoms, emotion identification difficulties may represent an early-life risk factor for negative peer relations, as inaccuracies in emotion identification have been shown to predict negative peer relations over time [19]. Ultimately, work is needed to solidify understanding of the temporal relationships among early-life emotion identification, depression, peer relations, and later weight status. Such work may provide targets for earlier interventions that could alter the developmental trajectory to obesity. Justification for such interventions would be supported if emotion identification could be linked to overweight status through these mediators.

The current study utilizes data from a longitudinal study to investigate how deficits in emotion identification, depressive symptoms, and poor peer relations during preschool age relate to BMI across development. The study examines preschool emotion identification ability and depressive symptoms at an initial time point, preschool depressive symptoms and peer relations at a later time-point, and early adolescent BMI at two even later final time points. Thus, the study investigates possible mediational relationships among these four variables. Previous studies in this sample examined the relationship between emotion identification and BMI across childhood [7], and the current report extends these findings from preschool age into early adolescence. We also extend previous findings by examining the independent relationships that early emotion identification abilities, early depressive symptoms, and early peer relations may show with weight status in early adolescence.

The study tests two main hypotheses. First, poorer emotion identification ability during preschool is expected to be associated with higher adolescent weight status and to be predictive of larger increases in BMI across early adolescence. Second, both greater depressive symptoms and poorer peer relations in early-life are expected to mediate the relationship between worse emotion identification ability in preschool and higher BMI in early adolescence.

Method

Participants

Participants were enrolled in the Preschool Depression Study, conducted at the Early Emotional Development Program at the Washington University School of Medicine in St. Louis. The Preschool Depression Study is a longitudinal study of preschoolers and their families with an oversampling of children with depressive symptoms [23]. A prior study examined associations with emotion identification and BMI in this sample, as reported elsewhere [7], and the current report describes secondary analyses from this sample. Unlike the prior study, the current study links emotion identification data from preschool age to data on BMI in early adolescence.

Participants were excluded for chronic medical illnesses, neurological problems, pervasive developmental disorders, or language and/or cognitive delays, and they were recruited from pediatricians’ offices, daycare centers, and preschools in the St. Louis Metropolitan area [24]. The current study utilizes 231 participants (n = 123 male; n = 106 minority race) who completed annual behavioral assessments over the course of 10 years, including assessments of emotion identification ability, BMI, depressive symptoms, and peer relations. The current study includes four different time points. The first two time points were categorized as representative of preschool age (M = 4.53 years, SD = 0.80; M = 5.56 years, SD = 0.80), and the second two time points were categorized as representative of early adolescence (M = 10.22 years, SD = 0.90; M = 11.20 years, SD = 0.89). Parental consent and child assent were conducted prior to participation. The Washington University School of Medicine’s Institutional Review Board approved all procedures.

Measures

Emotion Identification

Emotion identification was assessed through the Penn Emotion Differentiation Test (KIDSEDF) [25] at time one, the first preschool time point. This test contained 24 items measuring children’s ability to identify happy and sad faces. Children were shown pairs of faces expressing either happiness or sadness at varying intensity on a computer screen and were asked to determine which face expresses that emotion more intensely. Composite scores were created for the total number of correct responses, whereby higher scores represent more correct responses. This measure has demonstrated adequate reliability and validity amongst children and adolescents [26] and used as an index of treatment response in preschoolers [27, 28]. In the current sample, reliability was adequate (for happy faces: α = 0.61; for sad faces: α = 0.63).

BMI

Trained research assistants assessed participants’ height and weight, measured without shoes, at times three and four, both during early adolescence. BMI percentile was calculated using the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention growth charts [29]. BMI was adjusted for age and sex by following information on the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention website. 35% of the sample was characterized as overweight or obese at time three and 34% of the sample was characterized as overweight or obese at time four.

Peer Relations

The Health Behavior Questionnaire is a parent report measure that aims to assess behavior in children ages 4–8 years old [30]. The questionnaire contains multiple sections that measure children’s mental health, physical health, social functioning, and school functioning. This study selectively examined children’s social functioning through scores on the Peer Relations section, rated in eight items from the Peer Acceptance and Rejection subscale and three items from a Bullied by Peers subscale. This section included items like “Is picked on by other children”; “Is liked by other children who seek him/her out to play;” “Avoids peers;” “Prefers to play alone;” “Is considerate of others’ feelings” and “Offers to help other children/peers who are having difficulty with a task.” Both the Peer Acceptance and Rejection and Bullied by Peers subscales have demonstrated adequate crossinformant agreement among mother, father, and teacher reports [30]. Parents or guardians were instructed to rate the extent to which certain statements represent the social functioning of their child by providing a score of 1, “not at all like” to 4, “very much like.” Scores from every item were added in order to generate a composite value, whereby higher scores were representative of better peer relations. Parents/guardians completed the Peer Relations section at time two, the second preschool time point. In the current sample, internal consistency was good (α = 0.88).

Depressive Symptoms

The Preschool Age Psychiatric Assessment was used to assess psychiatric symptoms at time one and time two during preschool [31, 32]. These assessments contain developmentally appropriate questions that address diagnoses based on the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders, 4th Edition (DSM-IV) criteria for a disorder in childhood. For the purpose of the present report, DSM-IV symptoms for the following disorders was assessed: depression modified for preschool onset [33], attention deficit disorder, externalizing (oppositional defiant, and/or conduct disorder), and internalizing (posttraumatic stress disorder, generalized anxiety and separation anxiety). All diagnostic interviews were audiotaped and reviewed for reliability using established methods previously reported [34]. A depression severity score was created by calculating the number of items from the major depressive disorder module endorsed by the caregiver and/or child during each assessment. The depression severity score from times one and two was used analyses described below. Inter-rater reliability among clinicians was high for a diagnosis of depression (κ = 1.0; ICC = 0.98).

Income‑to‑Needs Ratio

Primary caregivers reported family income at times one and two. The early income-to-needs ratio (e.g., between ages 3 and 6) was computed as the total family income at baseline divided by the federal poverty level, based on family size, at the time of data collection [35]. This score was used a covariate in the analyses described below.

Statistical Analyses

All analyses were conducted using SPSS version 24 (IBM, Armonk, New York).

Repeated data on all covariates, main predictors (e.g. emotion identification ability, peer relations, depressive symptoms), and the outcome variable (BMI percentile) were available; therefore, we analyzed change in BMI percentile across time (i.e. using each adolescent assessment) using multilevel linear mixed (MLM) models [36] to account for dependencies due to repeated measurements. Preschool emotion identification ability, preschool depressive symptoms, and preschool peer relations were evaluated as a predictors of both the main effect and slope (rate of change) in BMI percentile across time. Fixed effects were included for time (i.e., within-individual change in BMI percentile across the assessments), correct emotion identification, preschool depressive symptoms, preschool peer relations, and the interactions between time and each predictor to examine the influence of these factors on changes in BMI percentile over time. All models included sex, ethnicity, and family income-to-needs ratio as covariates. All continuous predictors were mean-centered. Random effects for the BMI percentile intercept and slope for time were included to account for individual variability in mean levels of BMI percentile and rate of change in BMI percentile.

Multiple mediation analyses were used to test whether depressive symptoms and peer relations at time two mediated the effects of emotion identification on BMI percentiles at time three and time four. Mediation analyses controlled for age, sex, ethnicity, income-to-needs ratio and depressive symptoms at time one. Two multiple mediations were conducted using the PROCESS macro [37, 38]: one with time three BMI percentile as the outcome variable and one with time four BMI percentile as the outcome variable.

Results

The current study contains a diverse sample of participants in terms of demographic features (54% male; 46% minority race) representative of the St. Louis metropolitan area. Descriptive statistics and bivariate correlations between measures are provided in Table 1.

Table 1.

Means, standard deviations, and intercorrelations between measures

| 1. | 2. | 3. | 4. | 5. | 6. | 7. | 8. | 9. | 10. | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1. T1 child age | 4.53 (.80) | |||||||||

| 2. Gender | −0.02 | 123 (male) | ||||||||

| 3. Ethnicity | 0.02 | −0.03 | 106 (minority) | |||||||

| 4. T1 income to needs | −0.02 | −0.02 | −.57** | 2.03 (1.17) | ||||||

| 5. T1 depressive symptoms | 0.07 | −0.04 | 0.10 | −0.189** | 2.58 (1.84) | |||||

| 6. T2 depressive symptoms | 0.18** | −0.02 | −0.02 | −0.045 | .44** | 1.98 (1.60) | ||||

| 7. T1 emotion understanding | −0.01 | 0.07 | −0.05 | 0.079 | −0.19** | −0.13+ | 11.98 (3.80) | |||

| 8. T2 peer relations | −0.13+ | 0.08 | −0.244** | 0.294** | −.23** | −0.30** | 0.11 | 3.50 (.53) | ||

| 9. T3 BMI percentile | 0.06 | −0.05 | 0.17* | 0.047 | 0.14+ | 0.07 | 0.17* | −0.21** | 63.18 (28.79) | |

| 10. T4 BMI percentile | 0.10 | −0.00 | 0.23** | −0.054 | 0.05 | 0.06 | −0.01 | −.25** | 0.847** | 63.78 (28.61) |

N = 231, M(SD)

p < .10;

p < .05;

p < .01;

p < .001

We examined preschool emotion identification ability, depressive symptoms, and peer relations as predictors of the level and change in BMI percentile across early adolescence, controlling for the following covariates: sex, ethnicity, and family income-to-needs ratio. There were main effects for time, income-to-needs, ethnicity, depressive symptoms, and emotion identification ability (Table 2). There was a significant interaction between time and emotion identification ability, indicating that preschoolers with worse emotion identification ability showed the steepest increase in their BMI percentile over time (Fig. 1). To aid in the interpretation of this effect, we tested the significance of the simple slopes at 1SD below the mean, mean, and 1SD above the mean of preschool emotion identification ability. The simple slope was 21.06 at − 1SD (p = .01), 9.39 at the mean of emotion identification ability (p = .17), and 11.58 at + 1SD (p = .09). Thus, at lower levels of emotion identification ability, the slope of BMI becomes more strongly positive, indicating a stronger rate of increase in BMI percentile when compared to children with average or high levels of emotion identification ability. No significant interactions were found between depressive symptoms and time or peer relations and time.

Table 2.

Fixed effects estimates from multilevel models predicting change in BMI percentile from emotion identification, peer relations, and depressive symptoms

| B | SE | t | df | p | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Intercept | −77.29 | 59.93 | −1.29 | 92.94 | .20 |

| Time | 16.32 | 7.19 | 2.27 | 76.14 | .03 |

| Income to needs | 5.65 | 2.07 | 2.73 | 246.54 | .01 |

| Sex | 1.86 | 3.95 | .47 | 247.26 | .64 |

| Ethnicity | −12.11 | 4.78 | −2.54 | 246.06 | .01 |

| Peer relations | 12.25 | 14.45 | .85 | 95.29 | .40 |

| Depressive symptoms | 8.07 | 4.21 | 1.92 | 100.70 | .06 |

| Emotion identification | 5.99 | 1.79 | 3.34 | 99.96 | .001 |

| Time × peer | −2.34 | 1.73 | −1.35 | 75.47 | .18 |

| Time × emotion Identification | −0.58 | 0.21 | −2.73 | 77.34 | .01 |

| Time × depressive symptoms | −0.68 | 0.49 | −1.39 | 88.94 | .17 |

Fig. 1.

Model-implied trajectories of BMI percentiles at low, medium, and high levels of preschool emotion identification ability

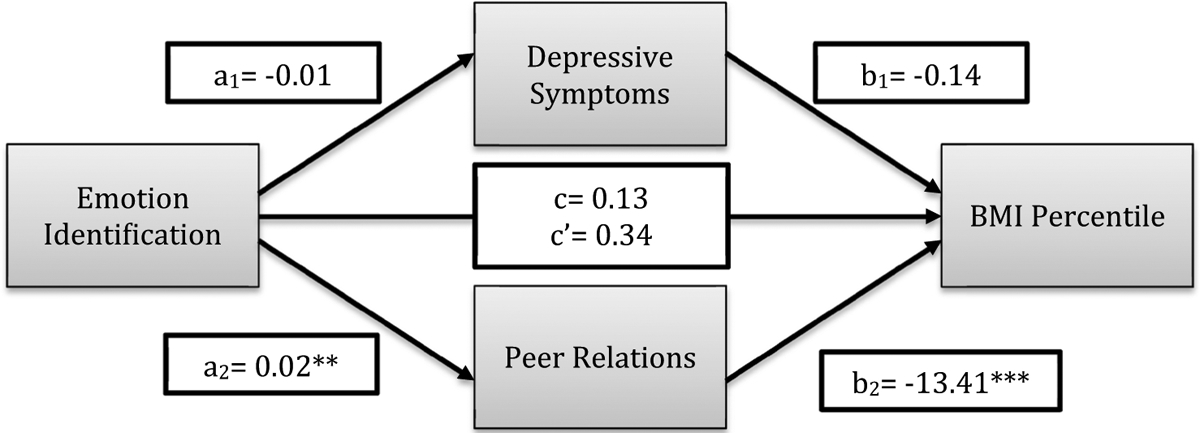

Multiple Mediation Analyses

Multiple mediation analyses controlled for age, sex, income to needs ratio, and time one depressive symptoms. Multiple mediation analyses showed that that total indirect effect of time one emotion identification on time three BMI percentile was significant [point estimate = − 0.08, 95% CI (− 0.17, − 0.02)]. Time one emotion identification was not associated with time two depressive symptoms [a1 = − 0.01, SE = 0.01, p = 0.36, 95% CI (− 0.04, 0.01)] but was positively associated with time two peer relations [a2 = 0.01, SE = 0.00, p = 0.01, 95% CI (0.00, 0.02)]. Time two depressive symptoms did not predicted time three BMI percentile [b1 = − 0.31, SE = 0.78, p = 0.69, 95% CI (− 1.85, 1.23)], however time two peer relations did positively predicted time three BMI percentile [b2 = − 7.77, SE = 2.39, p < 0.000, 95% CI (− 12.58, − 3.18)]. Time one emotion identification had a significant positive total effect on time three BMI percentile [c = 1.12, SE = 0.27, p < .000, 95% CI (0.60, 1.64)]. With the addition of time two depressive symptoms and time two peer relations to the model, the direct effect of emotion identification on BMI percentile was also significant [c′ = 1.20, SE = 0.27, p < .000, 95% CI (0.67, 1.72)]. The specific indirect effect of time one emotion identification on time three BMI percentile through depressive symptoms was not significant [point estimate = 0.00, 95% CI (− 0.01, 0.06)], whereas the specific indirect effect of time one emotion identification on time three BMI percentile via peer relations was significant [point estimate = − 0.08, 95% CI (− 0.17, − 0.02)]. The findings indicate that peer relations partially mediated the relationship between emotion identification and BMI percentile. Figure 2 displays results of the multiple mediation analyses examining depressive symptoms and peer relations at time two simultaneously as mediators of the relationship between time one emotion identification ability and time three BMI percentile.

Fig. 2.

Multiple mediation model for time one emotion identification and time three BMI percentile via time two depressive symptoms and peer relations. +p <.10; *p < .05; **p < .01; ***p < .001

Multiple mediation analyses showed that that total indirect effect of time one emotion identification on time four BMI percentile was significant [point estimate = − 0.21, 95% CI (− 0.35, − 0.11)]. Time one emotion identification was not associated with time two depressive symptoms [a1 = − 0.01, SE = 0.01, p = 0.28, 95% CI (− 0.04, 0.01)] but was positively associated with time two peer relations [a2 = 0.02, SE = 0.00, p = 0.01, 95% CI (0.01, 0.02)]. Time two depressive symptoms did not predicted time four BMI percentile [b1 = 0.14, SE = 0.79, p = 0.85, 95% CI (− 1.41, 1.70)], however time two peer relations positively predicted time four BMI percentile [b2 = − 13.41, SE = 2.49, p < 0.000, 95% CI (− 18.30, − 8.52)]. Time one emotion identification did not have a significant total effect on time four BMI percentile [c = 0.13, SE = 0.28, p = 0.64, 95% CI (− 0.42, 0.69)]. With the addition of time two depressive symptoms and time two peer relations to the model, the direct effect of emotion identification on BMI percentile was still not significant [c′ = 0.34, SE = 0.28, p = 0.23, 95% CI (− 0.21, 0.89)]. The specific indirect effect of time one emotion identification on time four BMI percentile though depressive symptoms was also not significant [point estimate = 0.00, 95% CI (− 0.05, 0.02)], whereas the specific indirect effect of time one emotion identification on time four BMI percentile via peer relations was significant [point estimate = − 0.20, 95% CI (− 0.35, − 0.11)]. The findings indicate that peer relations partially mediated the relationship between emotion identification and BMI percentile. Figure 3 displays results of the multiple mediation analyses examining depressive symptoms and peer relations at time two simultaneously as mediators of the relationship between time one emotion identification ability and time four BMI percentile.

Fig. 3.

Multiple mediation model for time one emotion identification and time four BMI percentile via time two depressive symptoms and peer relations. +p < .10; *p < .05; **p < .01; ***p < .001

Discussion

In a sample of youth oversampled for depressive symptoms, we found that deficits in emotion identification ability during preschool were associated with a greater BMI in early adolescence and predicted a greater change in BMI across two time points in early adolescence. Additionally, we found a significant positive association between preschool depressive symptoms and adolescent BMI, as well as a significant association between early-life peer relations and adolescent BMI, such that children with better peer relations during preschool were less likely to have overweight or obesity in early adolescence. Lastly, peer relations partially mediated the relationship between early emotion identification ability and early adolescent BMI.

Results supported the proposed hypotheses, as deficits in emotion identification during preschool age were related to a higher BMI in early adolescence and predicted a larger change in BMI across early adolescence. This association was also relevant to clinically meaningful categories; adolescents with obesity appeared to have worse preschool emotion identification ability than participants with a healthy weight. These findings extend previous literature on the relationship between emotion identification and weight status. Notably, while a previous report in this sample has demonstrated a connection between deficits in emotion identification and increases in BMI across childhood [7], the current study extends such prior findings by examining this relationship beginning from preschool age into early adolescence. Findings also suggest possible mechanisms for this effect.

The current study aimed to test the hypothesis that children’s depressive symptoms and peer relations play a role in the risk trajectory between emotion identification and BMI, as previous research has indicated that depressive symptoms and peer relations may relate to emotion identification [12, 19] and predict increased BMI [16, 21]. The current study examines the roles of these risk factors in the connection between emotion identification and weight status, and mediational models suggested that the association between emotion identification and BMI was at least partially mediated by depressive symptoms and peer relations.

These results help to isolate which among a group of modifiable risk factors may represent promising targets for future interventions in the service of obesity prevention. Since greater depressive symptoms, poorer peer relations, and emotion identification abilities were all connected to BMI later in life, these three risk factors may represent reasonable targets for intervention efforts. Moreover, the current study also found relations for specific risk factors assessed at specific points in time. As a result, research isolating the time course over which each risk factor predicts later weight status may further isolate targets and timing for preventative interventions. It is possible that early identification and improvement of emotion identification ability may prevent a maladaptive pathway towards worsening depressive symptoms, peer relations, and excess weight gain over time.

The current findings may be viewed within the context of research on stress, which suggests that children may consume food to cope with stress. Independent lines of research link stress to emotion processing and poor peer relations [39, 40]. For example, one line of work links stress exposure to biases in emotion identification in children [39], whereas a second line of research links stress exposure to difficulties in peer relations [40]. Finally, a third line of work connects stress exposure to increased food consumption [41]. For instance, following exposure to stress, children with overweight tend to consume greater amounts of high density salty foods when compared to individuals with a healthy weight [41]. The current study connects early emotion identification ability to later peer relations and BMI. Prior work suggests that these relations could arise through effects of stress exposure on maladaptive coping and increased food consumption.

The current study adds to the extant literature by providing longitudinal findings, extending the data from preschool age into early adolescence. As a result, it is possible to show that deficits in emotion identification, depressive symptoms, and poor peer relations all may contribute to greater increases in BMI across development and notably during the key period of adolescence. This is significant because adolescence is a transformative period whereby obesity tends to persist. Individuals with overweight in adolescence may be more likely to have overweight in adulthood [42]. As such, targeting risk factors that may lead to obesity in adolescence could help to prevent obesity later in life as well.

Alongside these strengths, there are some limitations to the current study that must be considered. First, it was not possible to account for genetic, family, and lifestyle influences, such as parental obesity and availability of healthy foods. These factors may also be contributing to the development and prevalence of obesity in the current sample. The current study also examined associations over time among four indices: emotion identification, depressive symptoms, peer relations, and BMI. However, all four indices were not assessed at every time point. Ideally, future research would provide such comprehensive assessments. Lastly, the emotion identification task only accounted for the identification of happy and sad faces. As such, it is possible that findings may change with a task that involves a broader range of emotions to identify.

Findings from the current study can be used to inform efforts to prevent obesity and suggest that targeting emotion identification abilities, depressive symptoms, and peer relations at particular time points in development may be fruitful. Interpersonal Psychotherapy has been shown to be effective for the treatment of depression in youth [43, 44], and more recent research has focused on Interpersonal Psychotherapy for the prevention of obesity and excess weight gain over time [45]. Consistent with these findings, this therapy focuses on aspects of emotion and social relationships. The utility of this therapy for obesity prevention could arise from its targeting of correlated stress-related factors, including emotion identification abilities and the quality of relationships, specifically with peers.

Finally, the results of the current study may inform the timing of specific preventive interventions that target obesity. Future interventions may focus on the early identification and improvement of emotion identification deficits. Such a focus is relevant both due to the current findings and due to prior research noting relations among emotion identification, stress responsivity, depressive symptoms, and excess weight [16, 39]. Thus, improving emotion identification could influence a pathway towards depressive symptoms, stress responsivity, and excess weight gain. Targeting novel early-life risk factors in development may be essential in order to prevent excess weight gain in children and adolescents.

Summary

Prior research has established a relationship between emotion identification and BMI across childhood. The current study extends these findings from preschool age through early adolescence and examines possible mechanisms. Specifically, we assessed the temporal relationships among emotion identification, depressive symptoms, and peer relations in preschool, and BMI in early adolescence. Results indicated that emotion identification in preschool was associated with adolescent BMI and predicted increases in BMI across early adolescence. Higher depressive symptoms and poorer peer relations during preschool were also associated with higher BMI in early adolescence. Finally, peer relations and depressive symptoms in preschool partially mediated the relationship between preschool emotion identification ability and early adolescent BMI. Such findings may be used to inform understanding of the relationship between emotion identification deficits and increased BMI, as well as appropriate obesity prevention interventions.

Acknowledgements

The authors wish to thank the children, caregivers, and staff of the Preschool Depression Study for their time and dedication to this project. Additionally, the authors wish to thank Dr. Marian Tanofsky-Kraff for her helpful comments and discussion regarding the paper.

Funding All phases of this study were supported by a National Institutes of Health Grant, R01 MH064769-06A1. Dr. Whalen’s work was supported by National Institutes of Health Grants: T32 MH100019 (PI’s: Barch and Luby), L30 MH108015 (PI: Whalen) and K23 MH118426 (PI: Whalen).

Footnotes

Conflict of interest The authors have no conflict of interest to declare.

Ethical Approval All procedures performed in studies involving human participants were in accordance with the ethical standards of the institutional and/or national research committee and with the 1964 Helsinki declaration and its later amendments or comparable ethical standards.

Informed Consent Informed consent was obtained from all individual participants included in the study.

Publisher's Disclaimer: Disclaimer The opinions and assertions expressed herein are those of the authors and are not to be construed as reflecting the views of the Uniformed Services University of the Health Sciences or the U.S. Department of Defense.

Publisher’s Note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

References

- 1.Pulgaron ER (2013) Childhood obesity: a review of increased risk for physical and psychological comorbidities. Clin Ther 35:A18–A32 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Rankin J, Matthews L, Cobley S, Han A, Sanders R, Wiltshire HD et al. (2016) Psychological consequences of childhood obesity: psychiatric comorbidity and prevention. Adolesc Health Med Ther 7:125–146 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Reilly JJ, Methven E, McDowell ZC, Hacking B, Alexander D, Stewart L et al. (2003) Health consequences of obesity. Arch Dis Child 88:748–752 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Ryder JR, Fox CK, Kelly AS (2018) Treatment options for severe obesity in the pediatric population: current limitations and future opportunities. Obesity (Silver Spring) 26:951–960 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Styne DM (2003) A plea for prevention. Am J Clin Nutr 78:199–200 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Baldaro B, Rossi N, Caterina R, Codispoti M, Balsamo A, Trombini G (2003) Deficit in the discrimination of nonverbal emotions in children with obesity and their mothers. Int J Obes Relat Metab Disord 27:191–195 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Whalen DJ, Belden AC, Barch D, Luby J (2015) Emotion awareness predicts body mass index percentile trajectories in youth. J Pediatr 167(821–828):e4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Baldaro B, Balsamo A, Caterina R, Fabbrici C, Cacciari E, Trombini G (1996) Decoding difficulties of facial expression of emotions in mothers of children suffering from developmental obesity. Psychother Psychosom 65:258–261 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Koch A, Pollatos O (2015) Reduced facial emotion recognition in overweight and obese children. J Psychosom Res 79:635–639 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Surcinelli P, Baldaro B, Balsamo A, Bolzani R, Gennari M, Rossi NC (2007) Emotion recognition and expression in young obese participants: preliminary study. Percept Mot Skills 105:477–482 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Barrera ME, Maurer D (1981) The perception of facial expressions by the three-month-old. Child Dev 52:203–206 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Auerbach RP, Stewart JG, Stanton CH, Mueller EM, Pizzagalli DA (2015) Emotion-processing biases and resting eeg activity in depressed adolescents. Depress Anxiety 32:693–701 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Dalili MN, Penton-Voak IS, Harmer CJ, Munafo MR (2015) Metaanalysis of emotion recognition deficits in major depressive disorder. Psychol Med 45:1135–1144 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Kohler CG, Hoffman LJ, Eastman LB, Healey K, Moberg PJ (2011) Facial emotion perception in depression and bipolar disorder: a quantitative review. Psychiatry Res 188:303–309 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Muhlig Y, Antel J, Focker M, Hebebrand J (2016) Are bidirectional associations of obesity and depression already apparent in childhood and adolescence as based on high-quality studies? A systematic review. Obes Rev 17:235–249 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Pine DS, Goldstein RB, Wolk S, Weissman MM (2001) The association between childhood depression and adulthood body mass index. Pediatrics 107:1049–1056 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Joormann J, Gilbert K, Gotlib IH (2010) Emotion identification in girls at high risk for depression. J Child Psychol Psychiatry 51:575–582 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Hale WW 3rd (1998) Judgment of facial expressions and depression persistence. Psychiatry Res 80:265–274 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Miller AL, Gouley KK, Seifer R, Zakriski A, Eguia M, Vergnani M (2005) Emotion knowledge skills in low-income elementary school children: assocations with social status and peer experiences. Soc Dev 14:637–651 [Google Scholar]

- 20.Adams RE, Bukowski WM (2008) Peer victimization as a predictor of depression and body mass index in obese and non-obese adolescents. J Child Psychol Psychiatry 49:858–866 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Mamun AA, O’Callaghan MJ, Williams GM, Najman JM (2013) Adolescents bullying and young adults body mass index and obesity: a longitudinal study. Int J Obes (Lond) 37:1140–1146 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Sutin AR, Robinson E, Daly M, Terracciano A (2016) Parent-reported bullying and child weight gain between ages 6 and 15. Child Obes 12:482–487 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Luby JL, Gaffrey MS, Tillman R, April LM, Belden AC (2014) Trajectories of preschool disorders to full DSM depression at school age and early adolescence: continuity of preschool depression. Am J Psychiatry 171:768–776 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Luby JL, Si X, Belden AC, Tandon M, Spitznagel E (2009) Preschool depression: homotypic continuity and course over 24 months. Arch Gen Psychiatry 66:897–905 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Gur RC, Ragland JD, Moberg PJ, Turner TH, Bilker WB, Kohler C et al. (2001) Computerized neurocognitive scanning: I. Methodology and validation in healthy people. Neuropsychopharmacology 25:766–776 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Gur RC, Richard J, Calkins ME, Chiavacci R, Hansen JA, Bilker WB et al. (2012) Age group and sex differences in performance on a computerized neurocognitive battery in children age 8–21. Neuropsychology 26:251–265 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Lenze SN, Pautsch J, Luby JL (2011) Parent–child interaction therapy emotion development: a novel treatment for depression in preschool children. Depress Anxiety 28:153–159. 10.1002/da.20770 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Luby JL, Lenze S, Tillman R (2012) A novel early intervention for preschool depression: findings from a pilot randomized controlled trial. J Child Psychol Psychiatry 53:313–322. 10.1111/j.1469-7610.2011.02483.x [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Kuczmarski RJ, Ogden CL, Guo SS, Grummer-Strawn LM, Flegal KM, Mei Z et al. (2002) 2000 CDC growth charts for the United States: methods and development. Vital Health Stat 11:1–190 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Essex MJ, Boyce WT, Goldstein LH, Armstrong JM, Kraemer HC, Kupfer DJ et al. (2002) The confluence of mental, physical, social, and academic difficulties in middle childhood. II: developing the Macarthur Health and Behavior Questionnaire. J Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry 41:588–603 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Angold A, Prendergast M, Cox A, Harrington R, Simonoff E, Rutter M (1995) The child and adolescent psychiatric assessment (CAPA). Psychol Med 25:739–753 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Egger HL, Erkanli A, Keeler G, Potts E, Walter BK, Angold A (2006) Test-retest reliability of the preschool age psychiatric assessment (PAPA). J Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry 45:538–549 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Luby JL, Heffelfinger AK, Mrakotsky C, Brown KM, Hessler MJ, Wallis JM et al. (2003) The clinical picture of depression in preschool children. J Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry 42:340–348 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Luby JL, Belden AC, Pautsch J, Si X, Spitznagel E (2009) The clinical significance of preschool depression: impairment in functioning and clinical markers of the disorder. J Affect Disord 112:111–119 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.McLoyd VC (1998) Socioeconomic disadvantage and child development. Am Psychol 53:185–204 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Raudenbush SW, Bryk AS (2002) Hierarchical linear models: applications and data analysis methods. SAGE, Thousand Oaks [Google Scholar]

- 37.Hayes AF (2012) PROCESS: a versatile computational tool for observed variable mediation, moderation, and conditional process modeling

- 38.Hayes AF (2013) Introduction to mediation, moderation, and conditional process analysis: a regression-based approach. Guilford Press, New York [Google Scholar]

- 39.Chen FS, Schmitz J, Domes G, Tuschen-Caffier B, Heinrichs M (2014) Effects of acute social stress on emotion processing in children. Psychoneuroendocrinology 40:91–95 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Morales JR, Guerra NG (2006) Effects of multiple context and cumulative stress on urban children’s adjustment in elementary school. Child Dev 77:907–923 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Horsch A, Wobmann M, Kriemler S, Munsch S, Borloz S, Balz A et al. (2015) Impact of physical activity on energy balance, food intake and choice in normal weight and obese children in the setting of acute social stress: a randomized controlled trial. BMC Pediatr 15:12. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Whitaker RC, Wright JA, Pepe MS, Seidel KD, Dietz WH (1997) Predicting obesity in young adulthood from childhood and parental obesity. N Engl J Med 337:869–873 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Mufson L, Weissman MM, Moreau D, Garfinkel R (1999) Efficacy of interpersonal psychotherapy for depressed adolescents. Arch Gen Psychiatry 56:573–579 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Mufson L, Dorta KP, Wickramaratne P, Nomura Y, Olfson M, Weissman MM (2004) A randomized effectiveness trial of interpersonal psychotherapy for depressed adolescents. Arch Gen Psychiatry 61:577–584 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Tanofsky-Kraff M, Wilfley DE, Young JF, Mufson L, Yanovski SZ, Glasofer DR et al. (2007) Preventing excessive weight gain in adolescents: interpersonal psychotherapy for binge eating. Obesity (Silver Spring) 15:1345–1355 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]