Abstract

Objective:

To investigate whether exposure to tobacco smoke during early brain development is linked with later problems in behavior and executive function.

Study design:

We studied 239 children in a prospective birth cohort. We measured tobacco exposures by caregiver report and serum cotinine three times during pregnancy and four times during childhood. We used linear regression to examine the association between prenatal and childhood serum cotinine concentrations and behavior (the Behavior Assessment System for Children-2: BASC-2) and executive function (the Behavior Rating Inventory of Executive Function: BRIEF) at 8 years while adjusting for important covariates.

Results:

Neither prenatal nor child serum cotinine were associated with behavior problems measured by the BASC-2. On the BRIEF, prenatal and childhood exposure was associated with poorer task initiation scores (B = 0.44, 95% CI = 0.03–0.85 and B = 0.69, 95% CI = 0.06–1.32 respectively). Additionally, in a subset of 208 children with non-smoking mothers, prenatal exposure was associated with task initiation scores (B = 1.17, 95% CI = 0.47–1.87) and additional components of the metacognition index (eg, working memory, B = 1.20, 95%CI = 0.34–2.06), but not components of the behavioral regulation index.

Conclusions:

Tobacco exposures during pregnancy (including low-level secondhand smoke) and childhood were associated with deficits in some domains of children’s executive function, especially task initiation and metacognition. These results highlight that reducing early exposure to tobacco smoke, even secondhand exposure, may support ideal brain functioning.

Despite the implementation of smoke-free policies and public health efforts to reduce tobacco use, the prevalence of cigarette smoking in the United States remains high. Approximately 37.8 million adults smoke,1 and 7.2% of mothers smoke during pregnancy.2 Consequently, about 58 million fetal, child, and adult non-smokers (including pregnant women) are exposed to second-hand (SHS) tobacco smoke3 representing a significant public health concern.

The developing fetus and children may be particularly vulnerable to the harmful effects of tobacco smoke. In pregnant women who smoke, nicotine is detected in amniotic fluid at levels 88% higher than maternal levels.4 SHS exposure to the pregnant mother has been associated with low birth weight, preterm birth,5–16 asthma,14 and delayed language skills.15–17 In addition, later exposure to secondhand smoke during childhood has also been associated with some of the same consequences.18–21 Although parental reports suggest that 25% of U.S. children are exposed to SHS in their homes, more objective biomarkers, like cotinine, indicate that 50% of US children are exposed to SHS.19,20

The documented associations between tobacco smoke exposure and child behavior and cognition are worrying.21,22 There is, however, limited research on the relationship of these exposures to a foundational ability partly underlying behaviors and cognition: executive functions. Executive functions refer to high-level processes responsible for goal-directed and problem-solving behaviors that facilitate goal-setting, task-switching, filtering distractions, and monitoring thoughts and behaviors.23 Core executive functions include inhibition (e.g., selfcontrol), working memory, and cognitive flexibility. Generally, executive functions refer to a set of cognitive and behavioral skills that are essential to success in school and life.24 Impairments in executive functions underlie clinical manifestations of some behavioral or cognitive deficits. Directly studying such impairments may help resolve links with environmental exposures and shed light on the underlying pathology impacted.

Piper and Corbett24 reported associations between maternal smoking in pregnancy and deficits in children’s executive function. They estimated tobacco exposure through maternal report, which is a less objective and inaccurate measure compared with biomarkers of exposure, like serum cotinine. In addition, because that study focused on children’s exposure via maternal smoking, their results do not elucidate whether exposure via secondhand smoke is associated with similar outcomes.25

Our objective was to investigate the associations between early life exposure to tobacco smoke and children’s behaviors and executive function. We improved on previous studies by using a more accurate and objective biomarker of children’s exposure relative to parents’ self-reported smoking, serum cotinine. Additionally, we examined children’s early exposures across distinct periods of early brain development to investigate the specific contribution of secondhand smoke exposure.

Methods

We used data from the Health Outcomes and Measures of the Environment (HOME) Study, an ongoing prospective cohort study of environmental exposures.26 We enrolled pregnant women from the Cincinnati, OH, area from 2003 to 2006. Women from 9 prenatal clinics associated with 3 hospitals were identified and invited to the study after meeting the following criteria: (1) 16 ± 3 weeks gestation; (2) >18 years of age; (3) HIV negative; and (4) not medicated for seizure or thyroid disorders. A total of 468 women enrolled in the study, 65 dropped out before delivery, and 3 were stillbirths. Of the 410 live births, 239 (58%) children had complete data through age 8 years and were included in our analyses. The study protocol was approved by the Institutional Review Board at Cincinnati Children’s Hospital Medical Center.

Pre- and Post-natal Assessment

We measured prenatal tobacco smoke exposure in two ways: maternal self-report and maternal serum cotinine. We measured childhood exposures using child serum cotinine. From pregnant women, we collected 3 serum samples: at 16- and 26-weeks’ gestation and at delivery) and from children, 4 serum samples (at ages 1, 2, 3, and 4 years) via venipuncture. All samples were stored at −20 degrees Celsius and shipped on dry ice to the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention Division of Laboratory Sciences. These were analyzed for cotinine using high-performance liquid chromatography-tandem mass spectrometry.27 To optimize statistical efficiency, for serum cotinine concentrations below the limit of detection (<0.015 ng/mL), we used the observed concentration rather than impute censored values.28 Prenatal exposure to lead was estimated using the mean of maternal whole blood samples obtained at 16- and 26-weeks gestation and at delivery. We collected demographic information (child sex; maternal race, marital status, education; and household income) during pregnancy and at delivery as covariates. Mothers also reported their use of tobacco products, exposure to secondhand smoke, and alcohol use while pregnant. Mothers completed both the Beck Depression Inventory29 (BDI-II) to measure maternal depression and the Wechsler Abbreviated Scale of Intelligence30 to measure maternal IQ. We also recorded the maternal age at delivery and quality of the home environment measured by the Home Observation for Measurement of the Environment (HOME) Inventory when children were at age 1 year.31

Assessment at age 8 years

Caregivers completed the Behavior Assessment System for Children-2 (BASC-2) to measure children’s problem behaviors. The BASC-2 is a 160-item, valid, reliable measure of child behaviors in the home and community.32 We analyzed three composite scales from the BASC-2: Externalizing Problems (hyperactivity, aggression, conduct problems), Internalizing Problems (anxiety, depression, somatization), and the Behavioral Symptoms Index (capturing overall levels of problem behaviors including atypicality, withdrawal, and attention problems). Caregivers also completed the Behavior Rating Inventory of Executive Function (BRIEF) to measure executive functions at age 8 years. The BRIEF is a 86-item, valid, reliable measure of children’s executive function at home and school.33 The BRIEF produces subscale scores for several dimensions of executive function, as well as a composite score. The subscales are: Inhibit (inhibiting and resisting impulses), Shift (easily moving between situations and activities), Emotional Control (modulating emotional responses), Initiate (independently starting tasks and generating ideas), Working Memory (holding information in mind to complete tasks), Plan/Organize (managing current and future demands), Organization of Materials (organizing work, play, and storage spaces), Monitor (assessing his or her own work), Behavioral Regulation Index (Inhibit + Shift + Emotional Control), Metacognition Index (Initiate + Working memory + Plan/Organize + Organization of Materials + Monitor), and Global Executive Composite (summary score of all eight scales).

We converted raw scores from the BASC-2 to age-standardized T-scores, and raw scores from BRIEF to age- and sex-standardized T-scores, using publisher-supplied normative data. For both instruments, the T-scores have a mean of 50 (SD = 10), and higher scores indicate more problems.

Statistical analyses

We conducted univariate analyses to assess distributional assumptions, check missing data, and compute descriptive statistics. We calculated separate means for tobacco smoke exposure during pregnancy and childhood. We calculated pregnancy mean serum cotinine as the mean of maternal serum cotinine concentrations at 16 and 26 weeks of gestation and delivery. Pearson correlations between log2 transformed maternal serum cotinine concentrations across these time points ranged from r = 0.87–0.91. Pearson correlations between log2 transformed child cotinine measures at ages 1, 2, 3, and 4 years ranged from r = 0.77–0.90. Given the stability of these values over time, we used the mean values of these concentrations in the following analyses. We excluded children from the analyses if they did not have serum cotinine measurements during childhood (n=19). Serum cotinine concentrations had a log-normal distribution, thus we log-transformed the serum cotinine concentrations prior to analyses. A base of 2 was used for ease of interpretation; therefore, the beta estimates reported correspond to a doubling of serum cotinine concentration.

We used separate multivariable regression models to examine the associations between both maternal and child mean serum cotinine with BASC-2 and BRIEF scores while adjusting for potential confounders (child sex, maternal race, marital status, education, household income, maternal alcohol use while pregnant, maternal depression, maternal IQ, maternal age at delivery, and HOME scores). We used a step-wise backward elimination method to obtain the most parsimonious models. During this process, we a priori included child sex and maternal race in all BASC-2 models, and maternal race in all BRIEF models. Other covariates were retained in the models if they were statistically significant (P < .05) or their removal resulted in >10% change in the beta estimate for maternal or child serum cotinine. We first obtained the most parsimonious model relating maternal mean cotinine and the Behavioral Symptoms Index (BSI), a composite score of the BASC-2, and then adjusted for the same set of covariates in the models examining the other BASC-2 scores. We chose the BSI as the basis for modeling this association as the BSI is the most comprehensive composite score of this assessment, incorporating six clinical subscales. The covariates included in the BASC-2 models were child sex, maternal race, marital status, and maternal BDI-II scores. We used a similar approach for the BRIEF. First, we obtained the most parsimonious model relating maternal mean cotinine and the Global Executive Composite (GEC), a comprehensive composite score of the BRIEF that incorporates all subscales, and then adjusted for the same set of covariates (maternal race, education, marital status, and maternal BDI-II scores) in models examining the other BRIEF scores. Given the similarities in the covariates in models of BASC-2 and BRIEF scores, we additionally included maternal education in models of the BASC-2 and child sex in models of the BRIEF to improve the comparability of effect estimates between the two assessments, even though BRIEF scores are already standardized based on sex- and age-specific norms. The final set of covariates for both BASC and BRIEF models included child sex, maternal race, marital status, maternal education, and BDI-II scores.

Because primary smoking and secondhand smoke represent different chemical mixtures, we conducted a secondary analysis among children whose mothers were only exposed to secondhand smoke during pregnancy. We analyzed a subset of children (n = 208), excluding those whose mothers reported actively smoking during pregnancy, to assess the associations between pregnancy mean cotinine and BASC-2 and BRIEF outcomes, adjusting for the same set of covariates as the earlier models.

Results

On most demographic characteristics, included children were not significantly different from excluded children (Table I). On average, mothers were age 29.1 years at delivery, and 63.4% were married.

Table 1:

Cohort Characteristics of Children Included and Not Included in the Current Study.

| Included n=239 | Not included n=171 | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Child Sex | ||||

| Male | 106 | 44.4% | 84 | 49.1% |

| Female | 133 | 55.6% | 87 | 50.9% |

| Maternal age at delivery (Mean, SD) | 29.1 | 5.9 | 29.7 | 5.5 |

| Maternal race | ||||

| Black | 80 | 33.5% | 45 | 26.3% |

| Non-Black | 159 | 66.5% | 121 | 70.8% |

| Maternal marital status* | ||||

| Married | 151 | 63.4% | 115 | 70.1% |

| Not married, living with partner | 28 | 11.8% | 28 | 17.1% |

| Not married, living alone | 59 | 24.8% | 21 | 12.8% |

| Maternal education | ||||

| High school or less | 59 | 24.7% | 36 | 22.0% |

| Some college | 65 | 27.2% | 35 | 21.3% |

| College graduate | 70 | 29.3% | 48 | 29.3% |

| Graduate or professional | 44 | 18.4% | 45 | 27.4% |

| Household income (25th, 75th percentile) | $55k | (18k,85k) | $55k | (28k,85k) |

| Maternal BDI-II* score (Mean, SD) | 9.9 | 6.4 | 9.8 | 7.5 |

| Maternal IQ (Mean, SD) | 105.7 | 15.0 | 106.8 | 13.5 |

| HOME Inventory score (Mean, SD) | 39 | 5.2 | 40 | 4.0 |

| Reported prenatal tobacco smoke exposure | ||||

| Active smoker during pregnancy | 31 | 13.2% | 18 | 11.2% |

| Passive exposure during pregnancy | 56 | 23.9% | 36 | 22.4% |

| Any exposure during pregnancy | 66 | 28.2% | 43 | 26.7% |

| No exposure | 168 | 71.8% | 118 | 73.3% |

| Reported childhood tobacco smoke exposure | ||||

| Yes | 57 | 24.1% | N/A** | |

| No | 180 | 75.9% | N/A** | |

| Reported maternal alcohol use during pregnancy | ||||

| None | 131 | 55% | 93 | 57% |

| <1 drink/month | 70 | 29% | 49 | 30% |

| >= 1 drink/month or binge | 37 | 16% | 22 | 13% |

BDI-II = Beck Depression Inventory-II, IQ = intelligence quotient, HOME Inventory = Home Observation for Measurement of the Environment Inventory

Significantly different comparison between children included and those not included (p<0.05)

Participants did not complete the age 8 year visit

Although only 28.2% of mothers reported any tobacco use or secondhand smoke exposure during pregnancy, 70.9% of mothers had detectable serum cotinine concentrations. Maternal mean cotinine during pregnancy ranged from 0.0005 to 291.7 ng/mL, with a geometric mean of 0.078 ng/mL. Similarly, whereas 24.1% of children were exposed to secondhand smoke by caregiver report, serum cotinine was above the limit of detection in 89.9% of children. Childhood mean cotinine ranged from 0.0002 to 20.2 ng/mL, with a geometric mean of 0.126 ng/mL (Table 2; available at www.jpeds.com).

Table 2.

Serum Cotinine Concentrations (ng/mL) in Maternal and Child Samples

| N | Min. | Max. | Geometric Mean (95% CI) | %>LOD* | %>3** | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Maternal cotinine | ||||||

| (prenatal) | ||||||

| 16 weeks | 234 | 0 | 349.0 | 0.075 (0.052 – 0.106) | 70.9% | 9.8% |

| 26 weeks | 229 | 0 | 252.0 | 0.06 (0.041 – 0.088) | 65.5% | 10.9% |

| Delivery | 211 | 0 | 282.0 | 0.05 (0.035 – 0.073) | 61.1% | 10.0% |

| Prenatal mean | 239 | 0.0005 | 291.7 | 0.078 (0.055 – 0.109) | 70.2% | 11.3% |

| Child cotinine | ||||||

| (postnatal) | ||||||

| 1 year | 186 | 0 | 35.3 | 0.114 (0.085 – 0.153) | 89.2% | 7.5% |

| 2 years | 147 | 0 | 10.5 | 0.094 (0.068 – 0.13) | 89.8% | 6.8% |

| 3 years | 157 | 0.002 | 21.6 | 0.071 (0.052 – 0.097) | 77.1% | 7.0% |

| 4 years | 128 | 0.003 | 14.9 | 0.06 (0.043 – 0.084) | 75.8% | 3.1% |

| Postnatal mean | 238 | 0.002 | 20.2 | 0.126 (0.098 – 0.162) | 89.9% | 7.1% |

LOD = 0.015 ng/mL;

3ng/mL is commonly used as an indicator of active smoking

BASC-2

BASC-2 T-scores for the three composite scales (Externalizing, Internalizing, Behavior Symptoms Index) all had a mean near 50 and a standard deviation near 10, which is representative of the normal distribution for the measure and expected in this sample of typically developing children (Table 3). With adjustment for covariates, we found no significant associations between maternal or child mean serum cotinine concentration and any of the BASC2 scales (Table 4).

Table 3.

BASC-2 and BRIEF Scores at Age 8 Years (N=239)

| MIN | MAX | MEAN | SD | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| BASC-2 | ||||

| Externalizing Problems | 32 | 90 | 49.5 | 9.4 |

| Internalizing Problems | 31 | 81 | 48.3 | 8.8 |

| Behavioral Symptoms Index | 31 | 80 | 49.7 | 9.0 |

| BRIEF | ||||

| Inhibit | 36 | 83 | 49.1 | 10.0 |

| Shift | 36 | 91 | 47.3 | 9.9 |

| Emotional Control | 35 | 78 | 47.4 | 9.9 |

| Initiate | 35 | 79 | 48.6 | 9.6 |

| Working Memory | 35 | 86 | 51.0 | 11.7 |

| Plan/Organization | 33 | 85 | 48.4 | 10.9 |

| Organization of Materials | 32 | 73 | 48.8 | 10.2 |

| Monitor | 28 | 81 | 46.3 | 10.7 |

| Behavioral Regulation Index | 33 | 79 | 47.6 | 9.9 |

| Metacognition Index | 31 | 83 | 48.4 | 10.9 |

| Global Executive Composite | 31 | 84 | 48.1 | 10.6 |

Table 4.

Adjusted* Change in BASC-2 and BRIEF Scores for Each Doubling of Serum Cotinine Concentration

| Maternal Mean Serum Cotinine | Child Mean Serum Cotinine | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| B | 95% CI | p-value | B | 95% CI | p-value | |

| BASC-2 | ||||||

| Externalizing Problems | 0.05 | −0.35, 0.44 | 0.814 | 0.23 | −0.36, 0.83 | 0.443 |

| Internalizing Problems | −0.23 | −0.61, 0.15 | 0.241 | 0.06 | −0.51, 0.63 | 0.839 |

| Behavioral Symptoms Index | 0.01 | −0.37, 0.39 | 0.964 | 0.46 | −0.11, 1.04 | 0.117 |

| BRIEF | ||||||

| Inhibit | 0.19 | −0.24, 0.62 | 0.383 | 0.12 | −0.54, 0.79 | 0.715 |

| Shift | 0.11 | −0.32, 0.54 | 0.622 | 0.24 | −0.42, 0.9 | 0.475 |

| Emotional Control | −0.09 | −0.52, 0.35 | 0.700 | −0.02 | −0.69, 0.64 | 0.950 |

| Initiate | 0.44 | 0.03, 0.85 | 0.038 | 0.69 | 0.06, 1.32 | 0.033 |

| Working Memory | 0.35 | −0.15, 0.86 | 0.163 | 0.76 | −0.01, 1.54 | 0.055 |

| Plan/Organize | 0.36 | −0.09, 0.82 | 0.115 | 0.28 | −0.42, 0.98 | 0.427 |

| Organization of Materials | 0.43 | −0.01, 0.87 | 0.059 | 0.53 | −0.15, 1.21 | 0.131 |

| Monitor | −0.09 | −0.55, 0.38 | 0.715 | 0.03 | −0.69, 0.74 | 0.943 |

| Behavioral Regulation Index | 0.07 | −0.35, 0.49 | 0.749 | 0.09 | −0.55, 0.74 | 0.777 |

| Metacognition Index | 0.34 | −0.12, 0.81 | 0.146 | 0.54 | −0.18, 1.25 | 0.143 |

| Global Executive Composite | 0.26 | −0.19, 0.71 | 0.256 | 0.40 | −0.29, 1.08 | 0.256 |

All models adjusted for child sex, maternal race, education, marital status, maternal depression measured with Beck Depression Inventory-II (BDI-II)

BRIEF

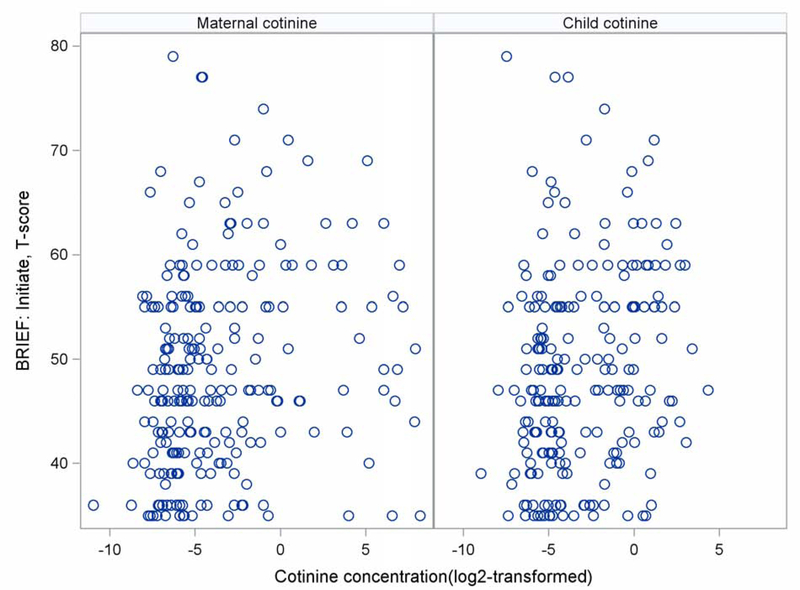

BRIEF T-scores had a mean near 50 and a standard deviation near 10 (Table 3), again representative of the normal distribution for the measure and expected in this sample. With adjustment for covariates (Table 4), we found that higher mean serum cotinine concentration during pregnancy was significantly associated with higher BRIEF subscale scores indicating poorer Initiation (B = 0.44, 95% CI = 0.03–0.85, p = 0.038, Figure [available at www.jpeds.com]). Other subscales were elevated but did not meet thresholds for statistical significance, most notably the Organization of Materials (B = 0.43, 95% CI = −0.01–0.87, p = 0.059). Child mean serum cotinine concentration was also significantly associated with poorer Initiation (B = 0.69, 95% CI = 0.06–1.32, p = 0.033, Figure 1), and a notable but non-significant association was found for poorer Working Memory (B = 0.76, 95% CI = −0.01–1.54, p = 0.055).

Figure 1.

Bivariate association between mean prenatal maternal and child serum cotinine concentrations (ng/mL) and T-scores on the BRIEF’s Initiate subscale.

Secondary Analysis of Secondhand Smoke Exposure During Pregnancy

In our analysis among children of mothers who reported not smoking during pregnancy (n=208), mean serum cotinine concentration was associated with a wider range of outcomes. Once again, we found no significant associations between maternal serum cotinine concentration and any of the BASC-2 scales (Table 5). However, higher maternal mean serum cotinine concentration was significantly associated with higher scores on both the Metacognition Index (B = 1.22, 95% CI = 0.44–2.00, p = 0.003) and Global Executive Composite (B = 1.05, 95% CI = 0.29–1.82, p = 0.007) as well as the individual scales of Initiate (B = 1.17, 95% CI = 0.47–1.87, p = 0.001), Working Memory (B = 1.20, 95% CI = 0.34–2.06, p = 0.007), Plan/Organize (B = 1.20, 95% CI = 0.44–1.96, p = 0.002), and Organization of Materials (B = 0.98, 95% CI = 0.23–1.73, p = 0.011).

Table 5.

Secondary Analysis: Adjusted* Change in BASC-2 and BRIEF Scores for Each Doubling of Serum Cotinine Concentration among Children with Mothers Who Were Not Self-Reported Active Smokers during Pregnancy (N=208)

| Maternal mean serum cotinine | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| B | 95% CI | p-value | |

| BASC-2 | |||

| Externalizing Problems | 0.45 | −0.21, 1.12 | 0.181 |

| Internalizing Problems | 0.07 | −0.58, 0.72 | 0.839 |

| Behavioral Symptoms Index | 0.53 | −0.11, 1.18 | 0.108 |

| BRIEF | |||

| Inhibit | 0.74 | −0.07, 1.48 | 0.053 |

| Shift | 0.48 | −0.26, 1.22 | 0.205 |

| Emotional Control | 0.37 | −0.38, 1.12 | 0.339 |

| Initiate | 1.17 | 0.47, 1.87 | 0.001 |

| Working Memory | 1.20 | 0.34, 2.06 | 0.007 |

| Plan/Organize | 1.20 | 0.44, 1.96 | 0.002 |

| Organization of Materials | 0.98 | 0.23, 1.73 | 0.011 |

| Monitor | 0.70 | −0.08, 1.47 | 0.078 |

| Behavioral Regulation Index | 0.61 | −0.12, 1.34 | 0.105 |

| Metacognition Index | 1.22 | 0.44, 2.00 | 0.003 |

| Global Executive Composite | 1.05 | 0.29, 1.82 | 0.007 |

All models adjusted for child sex, maternal race, education, marital status, maternal depression measured with Beck Depression Inventory-II (BDI-II)

Discussion

In this study, we found that children’s early exposure to tobacco smoke was associated with poorer executive function at age 8 years, even after adjustment for important covariates. The areas of executive function associated with these exposures included initiation, working memory, and organization. We observed similar associations when examining exposures during different windows of early brain development (i.e., during pregnancy and early childhood) and after excluding women who reported actively smoking during pregnancy. However, excluding mothers who reported active smoking revealed the greatest number of associations between early exposure to tobacco smoke and children’s later executive functions.

Our findings highlight associations between children’s early exposure to tobacco smoke and later deficits in executive function tasks using the BRIEF. Specifically, early exposure to tobacco smoke was associated with scores in the area of Initiation (i.e., the ability to independently begin tasks and generate ideas), the Organization of Materials (i.e., the ability to organize work, play, and storage spaces), and Working Memory (i.e., the ability to retain critical information and complete specific tasks).

These results are consistent with results reported by Piper and Corbett,24 who previously used the BRIEF to assess executive function in relation to pregnant mothers’ active smoking. Piper and Corbett also identified significantly higher scores on the BRIEF Initiate scale when comparing children with high versus no exposure with prenatal tobacco smoke. They also identified additional elevated scores on the Plan/Organize, and Monitor subscales, whereas our results for prenatal exposures identified impairments only on the Initiate subscale. These discrepancies could result from a number of factors including random error, our quantitative measurement of serum cotinine (which is more accurate than the self-reported measures of exposure used by Piper and Corbett24), or differences in prenatal exposure between the study samples (where they included direct maternal smoking and we included all sources of tobacco smoke exposure during pregnancy, dominated by secondhand smoke). In addition, we adjusted for maternal race and maternal depression in our analyses whereas these covariates were not considered by Piper and Corbett.24 Overall, our findings and those of Piper and Corbett reveal similar associations between early life exposure to tobacco smoke and later deficits in executive functions.

Our findings also provide some evidence that mother’s exposure to secondhand smoke during pregnancy may impair children’s later executive functions. In our secondary analysis, we excluded children whose mothers reported that they were active smokers during pregnancy. In addition to replicating the pattern of findings in our primary analysis, we observed significant associations with several additional dimensions of executive function (Working Memory, Plan/Organize, the Organization of Materials, and significant associations with the composite Metacognition and Global Executive Composite Indexes), and the overall effect sizes were larger. It is possible that this pattern emerged because including active smokers in the primary analysis did not account for unidentified confounding that masked the associations we observed after excluding active smokers. Assuming a causal effect of exposure to tobacco smoke on executive functions, it is possible that the greatest magnitude of impairments to executive functions occur with increases in the lowest levels of exposure. Indeed, this phenomenon has been reported previously for impairments to cognitive functions and associations with exposure to both second hand smoke18 and lead34 during childhood. However, our sample may not be ideal for exploring this possibility given that our overall cotinine concentrations tended to be low. Nevertheless, our study was well suited to study prenatal exposure to secondhand smoke because of the relatively small number of mothers who actively smoked and the inclusion of multiple measures of cotinine in pregnancy, capturing multiple sources of tobacco exposures.

Overall, the associations we observed between tobacco smoke exposure and executive function were modest. Our largest detected association for pregnancy secondhand smoke exposure was a 1.22 score increase per each doubling of serum cotinine. This would reflect a change of 4.28 points for a change reflecting the interquartile range of this population, from 0.011 ng/mL (25th percentile of cotinine) to 0.123 ng/mL (75th percentile of cotinine), which is close to one-half a standard deviation for the BRIEF. Bellinger notes that even slight effects of exposure may have a substantial impact at the population level by progressively shifting the population distribution of neurobehavioral traits. At the population level, this can increase the risk of neurodevelopmental disorders such as learning disabilities. Because 90% of children in our sample had detectable exposure to secondhand smoke, this suggests that the majority of children regularly come into contact with secondhand smoke. Thus, our findings provide support for the implementation of policies to eliminate maternal smoking during pregnancy and to minimize children’s exposure to secondhand smoke during childhood.

There are several limitations in our study. First, in this cohort study we can only report associations and cannot conclude a causal relationship between our measured variables. Second, our moderate sample (n = 239) may have limited our ability to detect associations between early exposure to tobacco smoke, child behaviors, and other domains of executive function. For example, a previous study documenting an association between early exposure to tobacco smoke and child behaviors21 utilized a sample of 1265 children, more than 5 times our sample. Third, although we adjusted for a variety of potential confounders, additional unmeasured covariates or confounders like substance use, psychosocial factors, or life experiences occurring between the ages of 4 and 8 years may explain some of our observed associations. It is also possible that other measures of either behavior or executive function that do not depend on parental report would show larger or smaller associations with exposure to tobacco smoke. Finally, we found that childhood tobacco exposures had a similar association with executive function as prenatal exposures. Still, it is possible that childhood exposures were partially confounded by prenatal exposures. This may occur because women who smoke during pregnancy may continue to smoke after delivery, leading to our observed collinearity between pregnancy and child mean serum cotinine concentrations (r = 0.79), so that we were not able to simultaneously adjust childhood associations for prenatal exposure to tobacco smoke.

The results of this study suggest that early exposure to tobacco smoke, both during pregnancy and childhood, is associated with later deficits in children’s executive function. The specific executive function skills that were affected – task initiation, working memory, the planning/organization of tasks, and the organization of materials – are components of metacognition: a higher-level cognitive ability essential for monitoring and controlling thoughts.23 In contrast, we found no significant associations with behavioral regulation aspects of executive function. Thus, our findings are consistent with the possibility that tobacco smoke exhibits greater deleterious effects on metacognitive executive functions than on behavioral regulation.

These findings highlight the need to increase public awareness to protect pregnant women and developing fetuses from tobacco smoke. This need is emphasized by the high prevalence of detectable tobacco smoke exposure in this sample, even at low levels, and significant associations between exposure levels and later executive functions. Future studies examining similar associations across cultural and geographic boundaries are needed to determine the generalizability of these findings. In addition, similar investigations in larger samples will help to assess the robustness of the more marginal associations we observed, and to corroborate our conclusion that early exposure to tobacco smoke is negatively associated with children’s executive functions.

Acknowledgements

We thank the staff and participants of the HOME Study and the Tobacco Laboratory at the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention for their contributions to this research.

Supported by the National Institutes of Health (P01ES11261, R01ES014575, and R01ES020349).

Abbreviations

- BASC-2

Behavior Assessment System for Children-2

- BRIEF

Behavior Rating Inventory of Executive Function

- BDI-II

Beck Depression Inventory

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- 1.Ahmed Jamal EP, Gentzke Andrea S., Homa David M., Babb Stephen D., King Brian A., Neff Linda J. Current cigarette smoking among adults -- United States, 2016. MMWR. 2018;67(2):53–59. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Drake P, Driscoll AK, Mathews T. Cigarette smoking during pregnancy: United States, 2016. NCHS Data Brief. 2018(305):1–7. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Secondhand Smoke: An Unequal Danger. CDC Vital Signs; 2015. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Luck W, Nau H, Hansen R, Steldinger R. Extent of nicotine and cotinine transfer to the human fetus, placenta and amniotic fluid of smoking mothers. Dev Pharmacol Ther. 1985;8:384–395. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Bellinger DC. A Strategy for Comparing the Contributions of Environmental Chemicals and Other Risk Factors to Neurodevelopment of Children. Environ Health Perspect. 2012;120(4):501–507. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Eskanazi BB, Jackie J. Passive and Active Maternal Smoking during Pregnancy, as Measured by Serum Cotinine, and Postnatal Smoke Exposure. I. Effects on physical growth at age 5 years. Am J Epidemiol. 1995;142(9):S10–S18. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Hanke WK J; Florek E; Sobala W. Passive smoking and pregnancy outcome in central Poland. Hum Exp Toxicol. 2999;18:265–271. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Herrmann MK, Katherine; Weitzman, Michael. Prenatal tobacco smoke and postnatal secondhand smoke exposure and child neurodevelopment. Curr Opin Pediatr. 2008;20:184–190. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Kahn RS, Certain L, Whitaker RC. A reexamination of smoking before, during, and after pregnancy. Am J Public Health. 2002;92(11):1801–1808. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Makin JF, Peter A. ; Watkinson, Barabra. A comparison of active and passive smoking during pregnancy: Long-term effects. Neurotoxicology and Teratology. 1991;13(5–12). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Salmasi G, Grady R, Jones J, McDonald SD, Knowledge Synthesis G. Environmental tobacco smoke exposure and perinatal outcomes: a systematic review and meta-analyses. Acta Obstet Gynecol Scand. 2010;89(4):423–441. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.U.S. Department of Health and Human Services. The health consequences of involuntary exposure to tobacco smoke: A report of the surgeon general. 2006; Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, National Center for Chronic Disease Prevention and Health Promotion, Office on Smoking and Health, 2006. [Google Scholar]

- 13.Shariat M, Gharaee J, Dalili H, Mohammadzadeh Y, Ansari S, Farahani Z. Association between small for gestational age and low birth weight with attention deficit and impaired executive functions in 3–6 years old children. J Matern Fetal Neonatal Med. 2019;32(9):1474–1477. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Simons E, To T, Moineddin R, Stieb D, Dell SD. Maternal Second-Hand Smoke Exposure in Pregnancy Is Associated With Childhood Asthma Development. J Allergy Clin Immunol Pract. 2014;2(2):201–207. e203. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Steyn KdW Thea; Saloojee Yussuf; Nel Hannelie; Yach Derek. The influence of maternal cigarette smoking, snuff use and passive smoking on pregnancy outcomes: the Birth To Ten Study. Paediatr Perinat Epidemiol. 2006;20:90–99. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Kabir Z, Connolly GN, Alpert HR. Secondhand smoke exposure and neurobehavioral disorders among children in the United States. Pediatrics. 2011;128(2):263–270. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Yolton K, Dietrich K, Auinger P, Lanphear BP, Hornung R. Exposure to environmental tobacco smoke and cognitive abilities among US children and adolescents. Environ Health Perspect. 2005;113(1):98. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Soliman S, Pollack HA, Warner KE. Decrease in the prevalence of environmental tobacco smoke exposure in the home during the 1990s in families with children. Am J Public Health. 2004;94(2):314–320. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Pirkle JL, Bernert JT, Caudill SP, Sosnoff CS, Pechacek TF. Trends in the exposure of nonsmokers in the US population to secondhand smoke: 1988–2002. Environ Health Perspect. 2006;114(6):853. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Fergusson DM, Horwood LJ, Lynskey MT. Maternal smoking before and after pregnancy: effects on behavioral outcomes in middle childhood. Pediatrics. 1993;92(6):815–822. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Park S, Cho SC, Hong YC, et al. Environmental tobacco smoke exposure and children’s intelligence at 8–11 years of age. Environ Health Perspect. 2014;122(10):1123–1128. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Gerard A. Gioia PKI, Steven C. Guy, Lauren Kenworthy . Behavior Rating Inventory of Executive Function Professional Manual. Lutz, FL: PAR; 1996. [Google Scholar]

- 23.Diamond A. Executive functions. Annu Rev Psychol. 2013;64:135–168. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Piper BJ, Corbett SM. Executive function profile in the offspring of women that smoked during pregnancy. Nicotine Tob Res. 2011;14(2):191–199. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Benowitz NL. Cotinine as a biomarker of environmental tobacco smoke exposure. Epidemiol Rev. 1996;18(2):188–204. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Braun JM, Kalloo G, Chen A, et al. Cohort profile: the Health Outcomes and Measures of the Environment (HOME) study. Int J Epidemiol. 2017;46(1):24–24. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Bernert JT, McGuffey JE, Morrison MA, Pirkle JL. Comparison of serum and salivary cotinine measurements by a sensitive high-performance liquid chromatography-tandem mass spectrometry method as an indicator of exposure to tobacco smoke among smokers and nonsmokers. J Anal Toxicol. 2000;24(5):333–339. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Cole SR, Chu H, Nie L, Schisterman EF. Estimating the odds ratio when exposure has a limit of detection. Int J Epidemiol. 2009;38(6):1674–1680. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Beck AT, Steer RA, Brown GK. Beck Depression Inventory - II. San Antonio, TX: The Psychological Corporation; 1996Reynolds C, Kamphaus R. Behavior Assessment [Google Scholar]

- 30.Wechsler W. Wechsler Abbreviated Scale of Intelligence. San Antonio: The Psychological Corporation; 1999. [Google Scholar]

- 31.Caldwell BM, Bradley RR. Home Observation for the Measured Environment. Little Rock, AR: University of Arkansas at Little Rock; 1984. [Google Scholar]

- 32.System for Children, (BASC-2) Handout. AGS Publishing. 2004;4201:55014–51796. [Google Scholar]

- 33.Gioia Gerald A. Behavior rating inventory of executive function: Professional manual. Psychological Assessment Resources, Incorporated, 2000. [Google Scholar]

- 34.Lanphear BP, Hornung R, Khoury J, Yolton K, Baghurst P, Bellinger DC, Canfield RL, Dietrich KN, Bornschein R, Greene T, Rothenberg SJ, Needleman HL, Schnaas L, Wasserman G, Graziano J, & Roberts R. (2005). Low-Level Environmental Lead Exposure and Children’s Intellectual Function: An International Pooled Analysis. Environ Health Perspect. 2005;113(7):894–899. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Skogerbø Å, Kesmodel US, Wimberley T, et al. The effects of low to moderate alcohol consumption and binge drinking in early pregnancy on executive function in 5 year old children. Br J Obstet Gynaecol. 2012;119(10):1201–1210. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Milberger S, Biederman J, Faraone SV, Chen L, Jones J. Is maternal smoking during pregnancy a risk factor for attention deficit hyperactivity disorder in children? Am J Psychiatry. 1996;153(9):1138. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Rodriguez A, Bohlin G. Are maternal smoking and stress during pregnancy related to ADHD symptoms in children? J Child Psychol Psychiatry. 2005;46(3):246–254. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Thapar A, Fowler T, Rice F, et al. Maternal smoking during pregnancy and attention deficit hyperactivity disorder symptoms in offspring. Am J Psychiatry. 2003;160(11):1985–1989. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Aguiar A, Eubig PA, Schantz SL. Attention deficit/hyperactivity disorder: a focused overview for children’s environmental health researchers. Environ Health Perspect. 2010;118(12):1646. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Toplak ME, Bucciarelli SM, Jain U, Tannock R. Executive functions: performance-based measures and the behavior rating inventory of executive function (BRIEF) in adolescents with attention deficit/hyperactivity disorder (ADHD). Child Neuropsychol. 2008;15(1):53–72. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Willcutt EG, Doyle AE, Nigg JT, Faraone SV, Pennington BF. Validity of the executive function theory of attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder: a meta-analytic review. Biol Psychiatry. 2005;57(11):1336–1346. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Braun JM, Kahn RS, Froehlich T, Auinger P, Lanphear BP. Exposures to environmental toxicants and attention deficit hyperactivity disorder in US children. Environ Health Perspect. 2006;114(12):1904. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]