Abstract

We report a case of Bartonella quintana endocarditis in a homeless man with congenital bicuspid aortic valve and significant cat exposure living in downtown San Diego, California.

Keywords: Bartonella quintana, culture-negative endocarditis, homeless

Case Description

A 48-year-old man presented to an emergency department in San Diego, California, in early 2019 with dyspnea, leg swelling, and an episode of chest pressure that reminded him of a heart attack that he suffered in 2012. He also endorsed fever, cough, and orthopnea for 1 month, and an unintentional 13.6 kg weight loss over the previous 6 months. Homeless for the past 2 years, he slept on the streets of downtown San Diego sharing blankets and pet cats among a group of friends. He had worked at his sister's horse ranch 20 years ago but denied farm animal exposure since then. Substance use included half a pack of cigarettes per day and one to two alcoholic drinks per month, but no intravenous drug use. On examination, he was afebrile and had conjunctival injection, poor dentition, a diastolic heart murmur, signs of fluid overload, and a petechial rash of bilateral lower extremities.

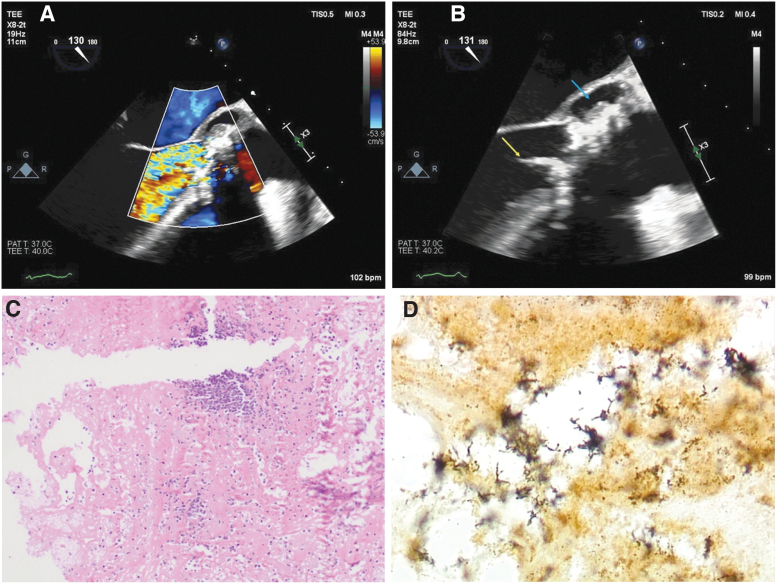

The cardiology service admitted the patient for evaluation and management of new onset heart failure. Transthoracic echocardiogram demonstrated a congenital bicuspid aortic valve with severe regurgitation, calcification, and a mobile echodensity prolapsing into the left ventricular outflow tract. Transesophageal echocardiogram confirmed the presence of mobile vegetations on bilateral aortic valve leaflets with associated perivalvular abscess (Fig. 1). Abdominal CT revealed splenomegaly of 14.4 cm and a 9 mm wedge-shaped splenic infarct. Blood cultures were collected before initiation of vancomycin, aztreonam, and metronidazole, chosen based on the patient's reported penicillin allergy. One blood culture bottle grew Staphylococcus pettenkoferi, and follow-up cultures were negative at 5 days incubation. A fourth generation HIV serology screen was negative.

FIG. 1.

Aortic valve echocardiography and surgical pathology. (A) Transesophageal echocardiogram midesophageal atrioventricular long axis view with Doppler of the aortic valve demonstrating severe regurgitation (yellow-orange-red turbulent flow). (B) Transesophageal echocardiogram midesophageal long axis view of the calcified bicuspid aortic valve with mobile vegetation (yellow arrow) and perivalvular abscess (blue arrow). (C) H&E stain at 10 × magnification demonstrating chronic inflammation. (D) Steiner stain at 100 × magnification demonstrating abundant pleomorphic rods. H&E, hematoxylin and eosin. Color images are available online.

Per infectious disease consultant recommendations, antibiotics were changed to vancomycin and ceftriaxone for coverage of S. pettenkoferi as well as streptococcal species and haemophilus aggregatibacter cardiobacterium eikenella kingella (HACEK) organisms. Additional work-up included Bartonella henselae and Coxiella burnetti serology performed at ARUP Laboratories in Salt Lake City, Utah. B. henselae IgG resulted as indeterminate with a negative IgM. C. burnetti IgG resulted as negative in phase I and indeterminate in phase II with negative IgM in both phases.

Owing to these indeterminate results, epidemiologic risk factors, and rise in erythrocyte sedimentation rate (ESR) from 43 to 109 mm/h, Bartonella quintana serology was added onto the original serum sample, and doxycycline 200 mg/day and gentamicin 3 mg/kg per day were added empirically on hospital day 12. The patient then underwent bovine aortic valve replacement with mitral and tricuspid valve repair the same day. The aortic valve tissue was soft and friable with complete dehiscence of bilateral coronary cusps of the annulus and an abscess under bilateral commissures. At the end of surgery, the patient went into shock with disseminated intravascular coagulation. Despite maximal support with extracorporeal membrane oxygen, mechanical ventilation, vasopressors, and continuous renal replacement therapy, the patient's condition continued to decline, and he died due to cardiac arrest 2 days after surgery.

Postmortem, B. quintana indirect fluorescent antibody testing resulted as positive with an IgG titer of 1:1024 and IgM of 1:256. Pathologic analysis of the aortic valve revealed chronic active inflammation with abundant pleomorphic bacilli visualized with Steiner stain (Fig. 1). Bacterial culture of the heart valve grew Staphylococcus epidermidis, suspicious for a contaminant as the species did not match the S. pettenkoferi that grew in blood culture. Bacterial, fungal, and nontuberculous mycobacterial PCR performed on a frozen heart valve specimen by the University of Washington detected B. quintana with 16s RNA gene and ribC primer set, further confirming the diagnosis.

Discussion

B. quintana infection manifestations include trench fever, bacillary angiomatosis, chronic bacteremia, lymphadenopathy, and endocarditis (Foucault et al. 2006). Long before identification of the causative agent, descriptions of trench fever from World War I identified exposure to the human body louse (Pediculus humanus) and sharing beds as significant risk factors for infection (Byam and Lloyd 1920). Sharing blankets with homeless friends suggested possible exposure to body lice; none were seen on this patient, but this does not rule out prior infestation.

Cat exposure added B. henselae to the differential but may also help to explain transmission of B. quintana that has been detected in cat dental pulp, cat fleas (Ctenocephalides felis), and in blood cultures from a woman after a feral cat bite (La et al. 2005, Breitschwerdt et al. 2007, Kernif et al. 2014). Flea-borne Rickettsia typhi, murine typhus, would be considered in the broad differential of unexplained fever, but would not present as endocarditis. There has been an ongoing outbreak of flea-borne typhus in California, particularly in Los Angeles county, but only one case was diagnosed in San Diego in 2019 (California Department of Public Health 2019).

Homelessness was an important clue to the correct diagnosis. A study of 71 homeless patients in Marseilles, France, demonstrated elevated B. quintana titers in 30% and positive B. quintana cultures in 14% (Broqui et al. 1999). The 1993 outbreak in 10 homeless alcoholic patients in Seattle, Washington, represented the first reported B. quintana cases among HIV-negative patients in the United States (Jackson et al. 1996). A 33.3% prevalence of B. quintana detected by PCR in body lice of homeless persons in San Francisco (Bonilla et al. 2009) further supports consideration for this infection in urban populations in California.

Bicuspid aortic valve disease is associated with a higher rate of infective endocarditis when compared with a structurally normal aortic valve (Becerra-Muñoz et al. 2017). Although a coagulase-negative staphylococcus species grew in one blood culture bottle, we pursued further work-up for culture-negative endocarditis because of risk for exposure to B. quintana and B. henselae as well as rising inflammatory markers while on vancomycin and ceftriaxone. In a prospective study of 819 patients with suspected blood culture negative endocarditis, 19.7% of cases with an identified etiologic agent tested positive for Bartonella species by indirect fluorescent antibody, Western blot or PCR (Fournier et al. 2010). Pathology of the aortic valve was suggestive of Bartonella spp. with pleomorphic bacilli identified by silver stain, but these findings are not genus or species-specific.

Final diagnosis was achieved using B. quintana indirect fluorescent antibody performed at ARUP. Microbiologic techniques to identify this fastidious intracellular gram-negative rod include axenic culture, cell culture, and prolonged incubation on blood agar, but serologic methods are more often used to diagnose infection (Foucault et al. 2006). In this case, concurrent B. henselae and C. burnetti serology both resulted as indeterminate. Cross-reactivity of B. quintana with B. henselae serology is 62% (Jackson et al. 1996), but as this case demonstrates, an indeterminate B. henselae serology does not exclude the diagnosis of B. quintana. Therefore, while awaiting laboratory confirmation, empiric initiation of the recommended regimen of doxycycline and gentamicin (Foucault et al. 2006) should, therefore, be considered in the appropriate clinical situation.

Acknowledgments

We thank Dr. Grace Lin and Dr. David Pride from the UC San Diego Health Department of Pathology for providing pathology slide images. We also thank Dr. Joseph Vinetz from Yale School of Medicine for providing helpful comments during article editing.

Author Disclosure Statement

No conflicting financial interests exist.

Funding Information

K.P. is supported by the following grant: NIH T32 AI 007036.

References

- Becerra-Muñoz VM, Ruíz-Morales J, Rodríguez-Bailón I, Sánchez-Espín G, et al. Infective endocarditis in patients with bicuspid aortic valve: Clinical characteristics, complications, and prognosis. Enferm Infecc Microbiol Clin 2017; 35:645–650 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bonilla DL, Kabeya H, Henn J, Kramer VL, et al. Bartonella quintana in body lice and head lice from homeless persons, San Francisco, California, USA. Emerg Infect Dis 2009; 15:912–915 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Breitschwerdt EB, Maggi RG, Sigmon B, Nicholson WL. Isolation of Bartonella quintana from a woman and a cat following putative bite transmission. J Clin Microbiol 2007; 45:270–272 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Broqui P, Lascola B, Roux V, Raoult D. Chronic Bartonella quintana bacteremia in homeless patients. N Engl J Med 1999; 340:184–189 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Byam W, Lloyd L. Trench fever: Its epidemiology and endemiology. Proc R Soc Med 1920; 13(Sect Epimiol Soc Med):1–27 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- California Department of Public Health. Human flea-borne typhus cases in California. 2019. Available at: www.cdph.ca.gov/Programs/CID/DCDC/CDPH%20Document20%Library/Flea-borneTyphusCaseCounts.pdf Accessed October16, 2019

- Foucault C, Brouqui P, Raoult D. Bartonella quintana characteristics and clinical management. Emerg Infect Dis 2006; 12:217–223 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fournier PE, Thuny F, Richet H, Lepidi H, et al. Comprehensive diagnostic strategy for blood culture-negative endocarditis: A prospective study of 819 new cases. Clin Infect Dis 2010; 51:131–140 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jackson LA, Spach DH, Kippen DA, Sugg NK, et al. Seroprevalence to Bartonella quintana among patients at a community clinic in downtown Seattle. J Infect Dis 1996; 173:1023–1026 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kernif T, Leulmi H, Socolovschi C, Berenger JM, et al. Acquisition and excretion of Bartonella quintana by the cat flea, Ctenocephalides felis felis. Mol Ecol 2014; 23:1204–1212 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- La VD, Tran-Hung L, Aboudharam G, Raoult D, et al. Bartonella quintana in domestic cat. Emerg Infect Dis 2005; 11:1287–1289 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]