Abstract

Background: Widespread community engagement in advance care planning (ACP) is needed to overcome barriers to ACP implementation.

Objective: Develop, implement, and evaluate a model for community-based ACP in rural populations with low English language fluency and health care access using lay patient navigators.

Design: A statewide initiative to improve ACP setting/subjects—trained in a group session approach, bilingual patient navigators facilitated 1-hour English and Spanish ACP sessions discussing concerns about choosing a surrogate decision maker and completing an advance directive (AD). Participants received bilingual informational materials, including Frequently Asked Questions, an AD in English or Spanish, and Goal Setting worksheet.

Measurement: Participants completed a program evaluation and 4-item ACP Engagement Survey (ACP-4) postsession.

Results: For 18 months, 74 ACP sessions engaged 1034 participants in urban, rural, and frontier areas of the state; 39% were ethnically diverse, 69% female. A nurse or physician co-facilitated 49% of sessions. Forty-seven percent of participants completed an ACP-4 with 29% planning to name a decision maker in the next 6 months and 21% in the next 30 days; 31% were ready to complete an AD in the next 6 months and 22% in the next 30 days. Evaluations showed 98% were satisfied with sessions. Thematic analysis of interviews with facilitators highlighted barriers to delivering an ACP community-based initiative, strategies used to build community buy-in and engagement, and ways success was measured.

Conclusion: Patient navigators effectively engaged underserved and ethnically diverse rural populations in community-based settings. This model can be adapted to improve ACP in other underserved populations.

Keywords: advance care planning, implementation science, Latino/a, lay patient navigator, rural

Introduction

Advance care planning (ACP) is a process that supports adults at any age or stage of health in understanding and sharing their personal values, life goals, and preferences regarding future medical care.1 Widespread community engagement in ACP is achievable in U.S. communities such as La Crosse, Wisconsin through multifaceted approaches.2 However, there may be significant statewide variation, including limited reach and uptake of ACP among rural or racially and ethnically diverse populations.3–6 From a community engagement and public health perspective, the value of community-based ACP initiatives is the potential for uptake and spread that leads to culture change within a population that have limited trust or access to traditional health care settings.

In the western United States, the state of Colorado has 64 counties of which 24 and 23 are considered rural (a nonmetropolitan county with no cities of >50,000 residents) and frontier areas (a county with a population density of ≤6 residents per square mile), respectively.7 Out of Colorado's population of 5.4 million citizens, 21% identify as Latino/a, and 750,000 live in rural/frontier areas.7 Because ACP initiatives are often sponsored by urban- or suburban-based health care institutions, rural populations are less likely to have access to health care practitioner-facilitated ACP discussions. Laypersons, including navigators, volunteers, community health workers, or peer educators, can provide support and health-related education, including ACP conversations and palliative care in community settings.8,9 In addition, patient navigation models for palliative care have been well developed as a culturally tailored primary palliative care model for Latino/as with serious illnesses.10,11 Given the lack of community-based initiatives to engage rural Latino/a communities in ACP, we developed and implemented a culturally tailored community program. This article describes the individual and community-level reach and lessons learned to support iterative development of community-based ACP implementation strategies that can be adopted by other communities.

Methods

The project's goal was to increase ACP engagement in targeted underserved rural communities in Colorado utilizing implementation science strategies employed through an interdisciplinary team (nurse, physicians, research assistant, and patient navigators) with expertise in ACP, palliative care patient navigation research, and a community-based culturally sensitive participatory action network.

Targeted rural Latino/a community engagement intervention

This outreach engagement initiative, targeting some of the most medically underserved populations in Colorado based on ethnic diversity and lower socioeconomic status, was reviewed by the Colorado Multiple Institutional Review Board (17-0265) and determined to be exempt nonhuman subjects' research. Our implementation strategy utilized two bilingual palliative care lay patient navigators, based on the western slope and northeastern Colorado, to facilitate ACP community sessions in English and Spanish using an ACP group session approach.12,13 Patient navigators conducted ACP group sessions in conference rooms located in clinic-based spaces, churches, community centers, senior centers, nursing homes, schools, area health education centers, businesses, libraries, metropolitan districts, home care agencies, homes, homeless shelters, and other community-based sites. They accomplished this work through culturally tailored education, building rapport and trust, and by being part of the local community. Participation was strictly voluntary; compensation was not provided to participants. A palliative care nurse (R.M.F.) or physician (S.M.F.) also attended and presented some of the larger and predominantly English sessions. This statewide outreach component significantly benefited from the experience, training, and community engagement our patient navigators had developed through previous and current research study work.8,9,14

The sessions were based on an adapted ACP group visit model.12,13 Facilitated groups lasted ∼1 hour within a comfortable and confidential space. Materials provided included a bilingual poster or PowerPoint presentation, Frequently Asked Questions handout, a Goal Setting worksheet, and a comprehensive easy-to-use advance directive (AD) in English or Spanish that could be completed at home.15,16 After a brief presentation, group members were invited to discuss their understanding and concerns about ACP, including examples of both positive and difficult personal experiences, and share examples of times when an AD had been completed and when it had not. Participants were encouraged to choose and document a Medical Durable Power of Attorney, as a preferred surrogate decision maker if unable to speak for themselves, and to discuss the question: “What would your surrogate(s) decision maker(s) need to know about your values and care preference to make the best decisions for your healthcare?”

Evaluation

Postsession, participants were asked to voluntarily complete an evaluation and the ACP Engagement 4-item Survey (ACP-4).17 All data were collected and managed using Research Electronic Data Capture (REDCap), a HIPAA-compliant web-based tool, hosted at the University of Colorado Anschutz Medical Campus.18 Primary project outcomes are the number of sessions conducted, number of participants reached, session evaluation including participant demographics, and ACP-4 Engagement Survey findings. Participants were also asked to voluntarily provide an e-mail or U.S. Postal Service mailing address for a short 6-week follow-up survey (ACP-4) to determine if an AD had been completed. At least 6 weeks after participants completed a session, the 4-question survey was either mailed (with a stamped return envelope) or e-mailed (REDCap survey) to the participant for completion. All follow-up data were recorded in REDCap.

A qualitative evaluation was conducted with the ACP session facilitators (two patient navigators, nurse, and physician) using the Promoting Action on Research Implementation in Health Services (PARHIS) framework to identify and evaluate successes of and barriers to project implementation.19,20 This was accomplished through four key informant interviews and engaging stakeholders in self-reflection regarding critical aspects of implementation and the related nature of needed change. Two team members (S.R.J. and F.A.B.) individually read and coded all transcripts using both a priori codes informed by topics from the semistructured interview guides (Supplementary Appendix SA) and emergent codes that were identified organically as coders read the transcripts. To reach consensus, the coders met twice to review notes and codes in an iterative manner.

Results

ACP sessions and participants

Between March 2017 and September 2018, we scheduled 74 ACP community sessions in multiple locations throughout Colorado (Fig. 1) with a total of 1034 participants in attendance. The average session was an hour in length and held in a community setting. Although the ACP sessions were predominantly conducted in English (69%), the remaining sessions were conducted in Spanish (8%) or were bilingual (23%). Session attendance ranged from 0 to 98 participants with an average of 19/session; seven scheduled meetings had no participants with only the community organizer in attendance. Of 1034 participants, 560 (54%) reported their demographics and completed the session evaluation (Table 1). The average participant was female (69%), Caucasian (61%) and had a mean age of 43.6 (±18.7) years. Thirty nine percent were ethnically diverse with 29% identifying as Latino/a. Evaluations showed 57% of participants were extremely satisfied, 41% satisfied, with 98% reporting the session was the right length of time.

FIG. 1.

Session locations. Data source information: site addresses were collected and grounded by the State Office of Rural Health, current as of January 2016. *Indicates counties where sessions were presented.

Table 1.

Demographics and Session Feedback

| ACP sessions | n (%) |

|---|---|

| Planned sessions | 74 |

| Participants who attended sessions | 1034 |

| Community participants | 743 (72) |

| Health care workers | 291 (28) |

| Participants/session (mean ± SD) | 18.9 ± 12.8) |

| Participants/session (range) | 0–98 |

| Length minutes (mean ± SD) | 60.0 ± 3.9) |

| Co-facilitated by nurse or physician | 36 (49) |

| Location | |

| Libraries | 17 (23) |

| Community centers | 13 (18) |

| Senior centers | 13 (18) |

| Schools (health care workers: LPN, CNA, MA) | 9 (12) |

| Businesses | 7 (9) |

| Metropolitan districts | 3 (4) |

| Clinics | 3 (4) |

| Homeless shelters | 2 (3) |

| Home care agencies | 2 (3) |

| Houses | 2 (3) |

| Area health education center | 1 (1) |

| Nursing homes | 1 (1) |

| Churches | 1 (1) |

| Language | |

| English | 51 (69) |

| Spanish | 6 (8) |

| Bilingual | 17 (23) |

| Participants | |

|---|---|

| Number of participants who completed surveys |

560 |

| Age, years (mean ± SD) |

43.6 ± 18.7 |

| Female gender |

383 (69.1) |

| Ethnicity, n (%) | |

| Caucasian |

343 (61.2) |

| Latino |

160 (28.6) |

| Other |

21 (3.7) |

| Native American/Alaskan Native |

16 (2.8) |

| Asian |

10 (1.8) |

| African American |

8 (1.4) |

| Pacific Islander/Native Hawaiian | 3 (0.5) |

| Participant satisfaction | n (%) |

|---|---|

| How satisfied were you with the ACP session? |

531 |

| Extremely satisfied |

303 (57) |

| Satisfied |

220 (41) |

| Somewhat satisfied |

8 (2) |

| Was the length of the session…? |

528 |

| About right |

518 (98) |

| Too long |

5 (1) |

| Too short | 5 (1) |

ACP, advance care planning; n, number; SD, standard deviation.

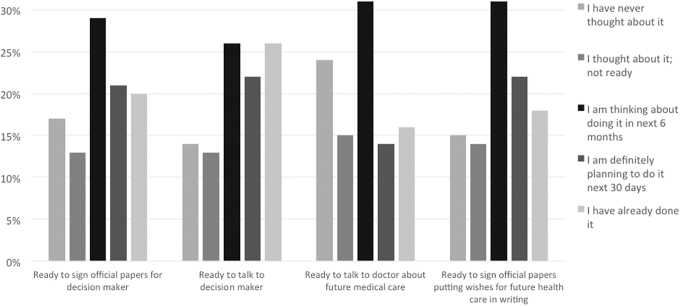

ACP engagement

Four hundred eighty-four (47%) participants completed an ACP-4 Engagement Survey (Fig. 2). When asked about naming a surrogate decision maker, 29% planned on doing so in the next 6 months and 21% in the next 30 days. When queried about readiness to talk about future health care decisions with a surrogate decision maker or provider, 26% were ready to talk about future health care decisions with decision maker in the next 6 months and 22% in the next 30 days; 31% were ready to talk to their provider about health care preferences in the next 6 months and 14% in the next 30 days. Finally, when asked about readiness to complete an AD, 31% were ready to complete an AD in the next 6 months and 22% in the next 30 days.

FIG. 2.

Responses to the ACP-4 Engagement Survey immediately postsessions (47% participants completed). ACP, advance care planning.

Only 36 participants asked for a follow-up survey to be mailed, and ∼205 participants requested that the survey be sent by e-mail. The surveys were mailed once. The e-mailed surveys were followed up with two reminder e-mails 1 week after the previous survey was sent, if not completed. Surveys were sent at least 6 weeks after the ACP session the participant attended. Only 31 follow-up surveys were completed and returned to the study team.

Qualitative evaluation

Session facilitators described barriers to delivering an ACP community-based initiative, strategies used to build buy-in and engagement in communities, and the ways they measured success of the initiative. These themes are described as follows; specific quotes are displayed in Table 2.

Table 2.

Common Themes

| Themes | Quotes |

|---|---|

| Barriers to delivering an ACP community-based initiative | “Barriers were… we just really had to get them interested in wanting to hear about an advance care directive, because, you know, ‘obviously we don't think about this until we're sick or our family member is sick,’ and I think just to get them to be able to focus and just hear us out. That was a big hurdle just to get them there.” |

| “Part of it is just having patients see a navigator as someone that is more like them than unlike. If I come in from the university and I feel it, and I hadn't asked them exactly what they feel, but like this ivory tower thing comes to mind. I can sit and say to the end of days like, ‘this is important, you should do this.’ Whereas someone who they see as like, oh, you live in the mountains too… and you're saying it's important and you've done it, I'm listening now.” | |

| Strategies used to build “buy-in” | “Basically, we broke it down to networking. I would go out to community meetings that they [local organizations] have, and I did get connected with a couple of people-business organizations were a great one. We had a senior community center where we presented and that was a great opportunity because at the same time, HR was going over insurance and we kind of jumped on that loop, and that was kind of like an extra benefit for them. It gave a positive spin on [it]; we're helping them, and they were helping us at the same time.” |

| “I tried to make it personal. I would say, like for instance, ‘before I started working this kind of work, I did not think about an advance care directive. I didn't even know what it was. Now once I found out about it and got myself educated on it, then it was easier for me to be able to provide the services.” | |

| “I think what worked well was having the questions and the answers [to] like ‘what should I do with this form after? Why should I have an advance care directive? What do I do with an advance care directive?’ Those kinds of questions, everything incorporated together.” | |

| “When I went to talk to the senior citizens, I think they were having fun with it. They were just such a crack up, I feel like they love to joke about that. And so, I think just even talking about somebody else making those decisions for you, but again, you bring it back, ‘well that's why we have advance directives, and that's why you appoint somebody as your healthcare agent.’ I just loved playing back off of that.” | |

| “I tried to make it as casual, not so military, just getting people's attention and maybe cracking a joke here and there. You just got to… anything to break the ice.” | |

| Measuring success | “I did have a couple individuals come up and say, I speak Spanish and it's so good to talk to somebody and just speak about advance care planning. They even asked for extra advance directives, which is awesome. I really liked the advance directives because they're bilingual, if you flip, one page is in Spanish, and that really helped a lot.” |

| “This elderly couple were like, should we take this to our lawyers? And I know that they wanted to talk to their doctor because they did have kind of like specialized questions that we've talked about. And [I] just kind of go back to the basics and tell them…. definitely go talk to your medical provider about those, and so that was just a great way to engage them in starting to get that conversation going.” | |

| “I did receive phone calls every once in a while, and that was mostly like, ‘hey, I was in your session, could you please send me more advance directives?’ And I definitely sent those out to them, or even dropped them off at their house.” | |

| “Just local people that I knew before even I was doing the presentations, people that are my friends that went to my session…. well, when I've seen them, I'm like, ‘hey, did you fill out your advance care directive? Yes or no?’ They looked at me and they are like, ‘oh, we haven't done it yet.’ But at least they have it there, you know?” | |

| “Spent a few nights out on the road, because the sessions would be like three days in a row, I would have maybe 9 or 10 different sessions, which was great…. I mean, that's a long drive, just exhausting.” |

Barriers to delivering an ACP community-based initiative

Although the two patient navigators live and work in their communities, barriers to engaging and accessing local populations often transcended their relatedness and made it difficult to build interest in ACP. Bilingualism and biculturalism were key components of their ability to relate to audiences at large, yet some beliefs participants held about delaying medical planning limited their ability to relate to ACP. One of the academic faculty facilitators not from communities in the project described occasionally feeling a challenging tension of recognizing her own “outsider” status coming from an academic university setting and facilitating sessions in smaller rural multicultural areas attempting to educate and engage a fundamentally different population.

Strategies used to build buy-in

Patient navigators learned and practiced different strategies over the course of their work that helped build interest and trust with local groups. Several described the barrier of relying on “cold calling” to connect with organizations, and shared approaches they used to initiate warmer connections with local groups, such as “tacking on” to pre-existing employee initiatives in local businesses. Patient navigators also shared tactics they used to subsequently build interest and communicate the relevance of ACP to participants in sessions, such as using personal stories to connect with participants. Integrating humor and adopting a casual approach also created a sense of safety and comfort while discussing a difficult topic. Other key strategies patient navigators employed included tailoring information to different populations, allowing enough time for questions, arranging seating in circle style to encourage conversation, paying attention to body language as cueing engagement levels, and using both bilingual written materials and bilingual verbal communication.

Measuring success

Patient navigators defined their goals for the project as hoping to initiate cultural change around ACP as a process that benefits all individuals, especially those in rural multicultural areas of Colorado. Interviews revealed the informal and indirect ways in which navigators measured whether this was occurring in real time. One patient navigator specifically addressed the successful use of bilingual ADs in sessions. Patient navigators considered participant question-asking, intent to follow up with health care providers, and follow up contact directly with patient navigators as successful examples of ACP engagement.

Some aspects of the initiative that felt less successful to patient navigators over time also emerged. The team's capacity was limited to cover multiple sessions throughout the state, which may be a limiting factor to initiating widespread culture change. One patient navigator also noted the slow spread of culture change yet was not entirely discouraged by the speed alone and noted that it may potentially be indicative of a positive “ripple” effect. Patient navigators also expressed that receiving formal feedback, such as survey data from session participants, was a challenge due to low response rates.

Discussion

Overall, the project team was successful in reaching >1000 community dwelling people across Colorado, utilizing a relatively small team over the course of a year and a half. This reach included urban, rural, and frontier areas of the state. More than half of the participants who completed postsession evaluations reported that they intended to complete some form of ACP within the next 6 months. Furthermore, responding participants also reported satisfaction with the sessions. This is particularly important as the majority of the larger group sessions were conducted during a standing meeting time; therefore, participants were not necessarily seeking ACP information.

Considerable strengths of our program include the use of a trained layperson patient navigator to facilitate group discussions and our use of a group visit model that can be adopted in other communities. However, the patient navigators often preferred to have the nurse and physician co-facilitate, requiring more faculty participation than initially planned. As time went on, the patient navigators became more comfortable facilitating group sessions. Group size also influenced patient navigator comfort with facilitation. Navigators reported the ideal group size was 10–20 participants. The larger groups (≥20 participants) were more likely comprising a convenience sample during a pre-existing regularly scheduled meeting at a local business, school, or long-term care setting. The smaller groups (<20) tended to be less predictable in attendance with several scheduled sessions having very few to no attendees. This proved problematic as patient navigators may have traveled considerable distances to facilitate the session.

The purpose of this project was to engage diverse community dwelling adults living in geographically broad areas in ACP. An inherent challenge in this work, in general, is determining the target population. Engaging younger people in this topic is particularly challenging. However, in looking back over Supreme Court cases that formed the legal foundation for ACP, many of the plaintiffs were the representatives of previously healthy young women, demonstrating the relevance to any adult, regardless of age or health. The patient navigators recognized and empathized with the reluctance of younger people to attend the sessions. The greatest success in facilitating attendance of a wide age range of group participants was to leverage an existing regularly scheduled meeting. Publicly advertised group sessions in libraries or community centers usually resulted in a modest turnout. However, leveraging relationships with businesses and existing groups to focus one of their usual meetings on the topic of ACP was highly successful leading to high participation and engagement. Working with state-funded area health education centers was also efficacious.

There has been a growing interest in raising community awareness of ACP for well adults. Programs including The Conversation Project and Common Practice's “Hello” game target community dwelling adults largely outside the medical setting.21,22 Research to date on these programs suggest that engaging in these activities leads to increased ACP and more conversations about death and dying.13,23,24 The publicly available Prepare for Your Care website is specifically tailored for a low health literacy audience with the videos and ACP content accessed in English or Spanish.25 Published results, to date, on the impact of Prepare for Your Care demonstrate that people assigned to receive the Prepare intervention were more engaged in ACP and more likely to complete an AD compared with those who were simply provided written materials.15 However, the studies were anchored in the primary care medical setting and not in broader community settings.

Notably, programs using community-based trained laypersons, volunteers, or navigators for ACP or end-of-life conversations have been feasible and well received by the trained individuals.8 Such programs have been reported from the United States, the United Kingdom, Canada, and Uganda, although the longer-term impact and sustainability of these programs is unknown.26–29 Furthermore, these programs focused on persons facing serious illness, not healthy community dwelling adults, as ours did. Overall, each of these publicly facing and offered ACP options may appeal to a particular person or community. For example, in the small community of La Crosse, Wisconsin ACP rates increased from 4% to 96% for a 30-year period largely through community conversations based on their Respecting Choices© model.2,30 Offering and increasing various model options to promote widespread ACP engagement at the community level will contribute to the movement toward culture change.

We acknowledge the challenge of our patient navigator-led group ACP sessions in enacting culture change in that this model depends on direct personnel involvement. Future work may consider a train-the-trainer model where existing local patient navigators or community health workers travel to receive training on conducting ACP group sessions bringing this training back to their own communities. This would also address the challenge of difficult travel (distance and at times weather) to reach some of the more remote frontier sites only to realize very low participant turnout. Although our team had limited capacity to travel to repeat visits to remote frontier locations that had low turnout, a local trained navigator could build success over time.

Limitations

Our program and evaluation have some limitations. First, only half of all participants completed the postsession survey, which could lead to unknown biases; those who may have been more engaged in the topic may have been more likely to complete the survey after the session. Far more significant is the very low rates of contact information for long-term follow-up survey and for even lower rates of completion for the long-term follow-up survey (3% of total participants). Participants were reluctant to share personal contact information and the qualitative evaluation was not able to include community participants. Finally, as a no-cost community-based educational initiative, this model is not a self-sustaining model for ongoing community engagement in ACP. Although this model leveraged and utilized community resources, including space, publicity, and volunteer community organizers, patient navigator time and travel were necessary program expenses. Once the funding period for the project was complete, it was not possible to continue to conduct sessions. However, presentation materials were shared with those wishing to share resources in their communities.

Implications

Our program reached underserved populations in Colorado as measured by ethnic diversity and socioeconomic status. Bilingual bicultural patient navigators effectively engaged underserved diverse populations in ACP in rural community settings. This model of ACP community engagement can be readily adapted by other health care settings and underserved populations to improve ACP completion and engagement.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

We thank our patient navigators, Diane Pacheco and Jeannette Rodriguez, for their dedication in ACP outreach and engagement. We also thank Rebecca Sudore, MD, for the use of the English and Spanish versions of the Easy to Read AD and ACP-4 survey that she developed.

Funding Information

This study was supported by a Colorado Health Foundation grant (25A5182) and in part by the National Institutes of Health (K76AG054782), Department of Veterans Affairs, and the NIH/NCRR Colorado CTSI Grant No. UL1 RR025780. The funders had no role in study design, data collection, analysis, interpretation, writing of the article, or decision to submit for publication. The contents of this article do not represent the views of the NIH, U.S. Department of Veterans Affairs or the U.S. Government.

Author Disclosure Statement

No competing financial interests exist.

Supplementary Material

References

- 1. Sudore RL, Lum HD, You JJ, et al. : Defining advance care planning for adults: A consensus definition from a multidisciplinary Delphi panel. J Pain Symptom Manage 2017;53:821..e1–832.e1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Hammes BJ, Rooney BL: Death and end-of-life planning in one midwestern community. Arch Intern Med 1998;158:383–390 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Clark MA, Person SD, Gosline A, et al. : Racial and ethnic differences in advance care planning: Results of a statewide population-based survey. J Palliat Med 2018;21:1078–1085 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Christensen KL, Winters CA, Colclough Y, et al. : Advance care planning in rural Montana: Exploring the nurse's role. J Hosp Palliat Nurs 2019;21:264–271 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Kirby S, Barlow V, Saurman E, et al. : Are rural and remote patients, families and caregivers needs in life-limiting illness different from those of urban dwellers? A narrative synthesis of the evidence. Aust J Rural Health 2016;24:289–299 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Mahaney-Price AF, Hilgeman MM, Davis LL, et al. : Living will status and desire for living will help among rural Alabama veterans. Res Nurs Health 2014;37:379–390 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Center CRH: Snapshot of Rural Health in Colorado. State Office of Rural Health, 2019. www.coruralhealth.org (Last accessed December10, 2019)

- 8. Somes E, Dukes J, Brungardt A, et al. : Perceptions of trained laypersons in end-of-life or advance care planning conversations: A qualitative meta-synthesis. BMC Palliat Care 2018;17:98. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Fischer SM, Sauaia A, Kutner JS: Patient navigation: A culturally competent strategy to address disparities in palliative care. J Palliat Med 2007;10:1023–1028 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Fischer SM, Kline DM, Min SJ, et al. : Effect of Apoyo con Carino (support with caring) trial of a patient navigator intervention to improve palliative care outcomes for Latino adults with advanced cancer: A randomized clinical trial. JAMA Oncol 2018;4:1736–1741 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Cervantes L, Chonchol M, Hasnain-Wynia R, et al. : Peer navigator intervention for Latinos on hemodialysis: A single-arm clinical trial. J Palliat Med 2019;22:838–843 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Lum H, Sudore R, Matlock D, et al. : A group visit initiative improves advance care planning documentation among older adults in primary care. J Am Board Fam Med 2017;30:480–490 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Lum HD, Jones J, Matlock DD, et al. : Advance care planning meets group medical visits: The feasibility of promoting conversations. Ann Fam Med 2016;14:125–132 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Fischer SM, Min SJ, Atherly A, et al. : Apoyo con Carino (support with caring): RCT protocol to improve palliative care outcomes for Latinos with advanced medical illness. Res Nurs Health 2018;41:501–510 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Sudore RL, Schillinger D, Katen MT, et al. : Engaging diverse English- and Spanish-speaking older adults in advance care planning: The PREPARE randomized clinical trial. JAMA Intern Med 2018;178:1616–1625 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Sudore RL, Landefeld CS, Barnes DE, et al. : An advance directive redesigned to meet the literacy level of most adults: A randomized trial. Patient Educ Couns 2007;69:165–195 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Sudore RL, Heyland DK, Barnes DE, et al. : Measuring advance care planning: Optimizing the advance care planning Engagement Survey. J Pain Symptom Manage 2017;53:669..e8–681.e8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Harris PA, Taylor R, Thielke R, et al. : Research electronic data capture (REDCap)—A metadata-driven methodology and workflow process for providing translational research informatics support. J Biomed Inform 2009;42:377–381 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Stetler CB, Damschroder LJ, Helfrich CD, Hagedorn HJ: A guide for applying a revised version of the PARIHS framework for implementation. Implement Sci 2011;6:99. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Helfrich CD, Damschroder LJ, Hagedorn HJ, et al. : A critical synthesis of literature on the promoting action on research implementation in health services (PARIHS) framework. Implement Sci 2010;5:82. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Common Practice: https://commonpractice.com/collections/hello-game. (Last accessed December10, 2019)

- 22. The Conversation Project: https://theconversationproject.org. (Last accessed August29, 2019)

- 23. Van Scoy LJ, Reading JM, Hopkins M, et al. : Community game day: Using an end-of-life conversation game to encourage advance care planning. J Pain Symptom Manage 2017;54:680–691 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Van Scoy LJ, Reading JM, Scott AM, et al. : Conversation game effectively engages groups of individuals in discussions about death and dying. J Palliat Med 2016;19:661–667 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Prepare for Your Care: https://prepareforyourcare.org/welcome. (Last accessed August29, 2019)

- 26. Rocque GB, Dionne-Odom JN, Sylvia Huang CH, et al. : Implementation and impact of patient lay navigator-led advance care planning conversations. J Pain Symptom Manage 2017;53:682–692 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Jones P, Heaps K, Rattigan C, Di M-M: Advance care planning in a UK hospice: The experiences of trained volunteers. Eur J Palliat Care 2015;22:144–151 [Google Scholar]

- 28. Jack BA, Kirton J, Birakurataki J, Merriman A: ‘A bridge to the hospice’: The impact of a Community Volunteer Programme in Uganda. Palliat Med 2011;25:706–715 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Claxton-Oldfield S, Jones R: Holding on to what you have got: Keeping hospice palliative care volunteers volunteering. Am J Hosp Palliat Care 2013;30:467–472 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Hammes BJ, Rooney BL, Gundrum JD: A comparative, retrospective, observational study of the prevalence, availability, and specificity of advance care plans in a county that implemented an advance care planning microsystem. J Am Geriatr Soc 2010;58:1249–1255 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.