Abstract

The lack of effective therapies for moderate-to-severe traumatic brain injuries (TBIs) leaves patients with lifelong disabilities. Neural stem cells (NSCs) have demonstrated great promise for neural repair and regeneration. However, direct evidence to support their use as a cell replacement therapy for neural injuries is currently lacking. We hypothesized that NSC-derived extracellular vesicles (NSC EVs) mediate repair indirectly after TBI by enhancing neuroprotection and therapeutic efficacy of endogenous NSCs. We evaluated the short-term effects of acute intravenous injections of NSC EVs immediately following a rat TBI. Male NSC EV-treated rats demonstrated significantly reduced lesion sizes, enhanced presence of endogenous NSCs, and attenuated motor function impairments 4 weeks post-TBI, when compared with vehicle- and TBI-only male controls. Although statistically not significant, we observed a therapeutic effect of NSC EVs on brain lesion volume, nestin expression, and behavioral recovery in female subjects. Our study demonstrates the neuroprotective and functional benefits of NSC EVs for treating TBI and points to gender-dependent effects on treatment outcomes, which requires further investigation.

Keywords: extracellular vesicles, neural stem cell, neuroprotection, TBI

Introduction

Moderate-to-severe traumatic brain injuries (TBIs) have an estimated financial burden of over $70 billion per year due to the permanent disability and medical costs associated with the injury,1 making it a major public health problem. TBI severity depends not only on the extent of primary brain tissue damage, but also on the secondary molecular injury cascades, which can persist for several months to years following a TBI, exacerbating tissue damage, dysfunction, and contributing to the reduced life expectancy of TBI survivors.2 Therapeutic interventions during the acute phase of TBI are therefore crucial to minimizing secondary injury and improving prognosis.3

Neural stem cell (NSC) transplantation has been actively explored as a means to replace lost neurons and reduce secondary injury after TBI.4 Although acute functional benefits were demonstrated in these studies,5,6 immune rejection, low cell engraftment, as well as the invasive delivery of transplanted NSCs remain major challenges that need to be overcome in order to achieve chronic functional recovery.4 In parallel to these issues, a growing body of recent evidence also suggests that NSCs are more likely promoting functional recovery not directly via cell replacement and differentiation, but indirectly via “bystander” signaling mediated by NSC-secreted factors and paracrine mechanisms.7 NSC EV treatment has been demonstrated to promote neural tissue preservation and functional recovery after ischemic stroke in mouse and pig models.8,9 Intravenously administered NSC EVs preferentially accumulate at the injury penumbra, and are suspected to be taken up by recipient cells.8 NSC EVs do not pose threats associated with uncontrolled growth or immune rejection and are able to cross the blood–brain barrier (BBB),10 which allows for less invasive methods of delivery and repeated treatments if desired. Due to their neuroprotective and immunomodulatory properties, NSC EVs could present a viable “cell-free” therapy for TBI and an alternative to direct stem cell transplantation.

Sexual dimorphism between male and female brains contributes to sex-dependent differences in outcomes following TBI, suggesting innate differences in brain repair and compensatory mechanisms.11 A number of clinical studies report worsened TBI outcomes in women than in men, with increased risk of death in women experiencing moderate-to-severe TBIs.12,13 Sexual dimorphism in TBI pathology is also reflected in the altered microglial and macrophage activation patterns in males versus females as reported in recent pre-clinical studies.14,15 In contrast to the above reports, the neuroprotective effects of female hormones such as estrogen and progesterone have also been linked to reduced mortality after TBI in women when compared with age-matched men.16 The complex pathophysiological manifestations of different TBI types along with the sex-dependent changes in brain structure, chemistry, neuroinflammation, and recovery, warrant the need for better pre-clinical study-design criteria in order to comprehensively understand the sex-dependent manifestations of TBI and the effects of novel therapeutics on recovery.

In this study, we conducted controlled cortical impact (CCI) injuries to the rat motor cortex and intravenously administered size-constrained NSC EVs to male and female rats acutely post-TBI. We longitudinally assessed functional recovery using a beam-walk test over a 4-week period and performed terminal immunohistochemical assessments to quantify changes in lesion size, glial scar formation, NSC presence, and angiogenesis.

Methods

Extracellular vesicle isolation

Human embryonic H9 cells were differentiated into NSCs using standard procedures previously published.9 Medium was harvested from NSC cultures every 24 h from a single passage. Media was filtered through a 0.22-μm filter and then further enriched by ultrafiltration using a Tangential Flow Filtration (TFF) system (all from Spectrum Laboratories, Rancho Dominguez, CA) and filtrate was subsequently washed with 10 X HyCloneTM DPBS (Thermo Fisher Scientific). NSC EV size and concentration were verified using nanoparticle tracking analysis via a NanoSight NS300 instrument (Malvern Panalytical, Malvern, UK). NSC EVs were diluted 1:100 in phosphate-buffered saline (PBS), mixed thoroughly via trituration, and advanced through the microfluidic detection chamber at a controlled rate using a syringe pump. Analysis was performed using NTA software (Malvern), and reported values are average values from five individual 60-sec recordings (Supplementary Fig. S1). The resulting concentrated extracellular vesicles were aliquoted and stored at -20°C until needed for treatments.

In vitro scratch wound assay

A scratch wound assay was performed using procedures adapted from previously published methods.17 Briefly, human neural progenitor cells (hNP1; ArunA Biomedical, Inc., Athens, GA) were cultured and expanded as described above and passaged onto 24-well plates (Fisher Scientific, Waltham, MA) coated with Matrigel (Corning, Corning, NY). When confluent, a vertical scratch was made through the center of each well using a P200 pipette tip (Mettler Toledo, Columbus, OH). Culture media was replaced with fresh media either with or without the addition of NSC EVs (approximately 2 × 108 EVs/well), and wells were imaged immediately and at the same locations 48 h later. The area of the “scratch wound” was calculated using ImageJ (National Institutes of Health [NIH], Bethesda, MD) by outlining the area without cells and using the “Measure” function on all images, and closure was calculated by dividing the area at T0 by the area at T48. Experiment was repeated thrice (n = 10).

CCI induced TBI of the rat motor cortex

All animal work and procedures were approved by the University of Georgia Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee and were in accordance with the NIH. Power analysis on preliminary animal behavior and tissue changes indicated that n = 7 per group would be sufficient to reach a cut off of 1 - ß = 0.8. We then included n = 8 rats per group to account for optimal reduction of effect size and for additional variability in our assays. Twenty-four male and 24 female adult Sprague-Dawley rats (250 ∼ 270 g; Envigo) were randomly assigned to one of the following groups: 1) CCI (sham) control (male = 8, female = 8); 2) vehicle (isotonic PBS)-treated (male = 8, female = 8); and 3) NSC EV-treated group (male = 8, female = 8). A focal CCI injury was induced using a custom-built pneumatic impactor that has been characterized by us previously.18 Briefly, the animal was anesthetized with 2-3% isoflurane, and received a craniotomy to expose the left hindlimb motor cortex region in the right hemisphere (bregma 0, 1.5 mm lateral from the midline as the center of the impact).19 A 3mm diameter tip was pneumatically actuated at an average velocity of 2.17m/sec with the average cortical dwell time of 250 msec to create an injury depth of 2 mm. Excess blood was removed and the craniotomy site was covered with 0.5% sterile seakem agarose (Lonza, NH). The incision was closed using nylon fiber sutures (ACE, MA). NSC EV-treated and vehicle-treated rats received three doses of either NSC EV (4e10EVs/kg in 1.6 mL) or vehicle (isotonic PBS; 1.6 mL) via tail vein using a 3 mL syringe attached to a 26 G needle at 4-6 h, 24-26 h, and 48-50 h post-CCI. The volume injected was necessary (given our TFF system EV concentration efficiency) to achieve the desired dose of 4e10 EVs/kg, which was chosen based on our previous in vivo EV studies.8,9

Motor function assessments

The animal's fine motor coordination and ability to maintain balance were assessed via a beam walk test. All animals were trained for 3 consecutive days prior to CCI, and the performance was measured on 4, 7, 14, 21, and 28 days post-CCI. The animal was placed at the bottom of a 1-m long beam tilted at 30 degrees angle and allowed to climb up the beam into a black box located at the end of the beam. The number of foot faults, falls, as well as the time to complete the task and final distance climbed were documented. Data was analyzed by the primary experimenter and confirmed by a second experimenter via video recording. All experimenters and animal handlers were blinded to treatment groups. One outlier in each male group (NSC EV-treated, vehicle and control) was detected using univariate approach (RStudio Inc., MA), confirmed using expected behavioral impact of TBI and excluded from analysis.

Tissue collection

Four weeks post-CCI, animals were euthanized via transcardial perfusion with 4% paraformaldehyde. Once the perfusion was completed, the brain was extracted and incubated in PBS with 30% sucrose at 4°C until saturated. It was embedded in Optimal Cutting Temperature compound (Thermo Fisher, NH) and flash frozen in liquid nitrogen. Extracted brains were sectioned at 15-μm thickness using a cryostat (Leica Biosystems, IL).

Hematoxylin and eosin staining

Hematoxylin and eosin staining was used to determine the lesion area of the coronal sections between bregma +0.5 mm and -0.5 mm. The “Measure” function in ImageJ (NIH, Bethesda, MD) was used to calculate the area of the lesion by overlaying the contralateral hemisphere to the injured hemisphere, and outlining the missing tissue (N = 96; 48 animals, two sections per animal). Remaining tissue was estimated as a lost tissue area in mm2 and percentage of remaining intact cortex. An outlier in male NSC EV–treated animal cohort was detected using the univariate approach (Rstudio Inc., MA) and excluded from analysis.

Immunohistochemistry

Non-consecutive sections were rinsed with PBS three times and incubated in blocking buffer (PBS with 0.5% Triton-X100 containing 4% bovine serum albumin or 4% goat serum) for an hour. Sections were then incubated in blocking buffer containing primary antibodies against glial fibrillary acidic protein (GFAP; Z0334; 1:500), NeuN (ABN91; 1:500), CD68 (MCA341R; 1:100), RECA-1 (MCA970R; 1:200), COL IV, nestin (AF2736; 1:1000), Sox1 (ab87775; 1:500), and Flk-1 (sc-315; 1:250) overnight at 4°C. The next day, sections were rinsed with washing buffer (PBS with 0.5% Triton-X100) three times followed by an hour of blocking. Sections were incubated in blocking buffer containing AlexaFluor 488 (Life Technologies, CA), AlexaFluor 555 (Life Technologies, CA), and AlexaFluor 647 (Life Technologies, CA) for secondary binding. The sections were rinsed again with washing buffer, counterstained with NucBlue (Life Technologies, CA), and mounted with fluoromount-G (SouthernBiotech, AL). Images were obtained using the Leica DM microscopy system (Leica Microsystems Inc., IL). Volocity Software (PerkinElmer, MA) was used to process the raw images obtained for fluorescence expression. GFAP line intensity values were obtained using the MATLAB Image Processing Toolbox (Mathworks, MA)20; n = 5 (two slides/animal, total 30 animals × 2 slides = 60 slides) was used for GFAP intensity analysis.

Composite scores

For all groups, a total of 11 variables were obtained from behavioral assessments at Day 28 (Beam walk completion time, distance, number of falls, left hindlimb faults, right hindlimb faults, left forelimb faults and right forelimb faults) and histological data (Lesion volume, nestin, vascular endothelial growth factor receptor 2 [VEGFR2], and GFAP expression). We then computed composite scores summarizing the overall recovery of the animals using two popular dimensionality reduction methods (R-package): The Fisher linear discriminant analysis (LDA) and principal component analysis (PCA). Using a linear classifier (multi-variate normal density fitting with a pooled estimate of covariance; Mathworks, Inc.) and a leave-one-out cross-validation approach, we computed the accuracy (true positive over total sample in percentage) and the sensitivity (true positive over the sum of true positive and false negative, in percentage) to assess the best separating variable combination. The dimensionality reduction approaches used the first two components with the highest explained variance for both LDA and PCA. Classification results were computed separately for male and female data.

Statistical analysis

For all group comparisons, Kolmogorov-Smirnov and Levene's tests were performed to test for normality and equality of variance, respectively. When sample size and normality were verified, parametric tests were performed for two or three sample comparisons (Student's t-test, one-way analysis of variance [ANOVA]), and non-parametric tests were used otherwise (i.e., Wilcoxon rank sum test, ANOVA on ranks). For multiple factor conditions, two-way ANOVA and repeated measure ANOVA (rmANOVA) were performed. Post hoc multiple comparisons were performed using Holm-Sidak test, which adjusts the significance level for multiple comparisons and provides tighter bounds. Holm-Sidak test can be used for both pairwise comparisons and comparisons versus a control group. Tukey nonparametric comparison was used as a post-hoc test in ANOVA on ranks. Pearson's correlation was used for correlations between VEGFR2 percentage expression area and nestin percentage expression area. A p value lower than 0.05 was considered significant and all statistical tests were performed using Sigmaplot (Systat Software, Inc., CA) and R-studio (RStudio Inc., MA). All values are reported as mean ± standard error of the mean and n = 8 per group unless otherwise specified.

Results

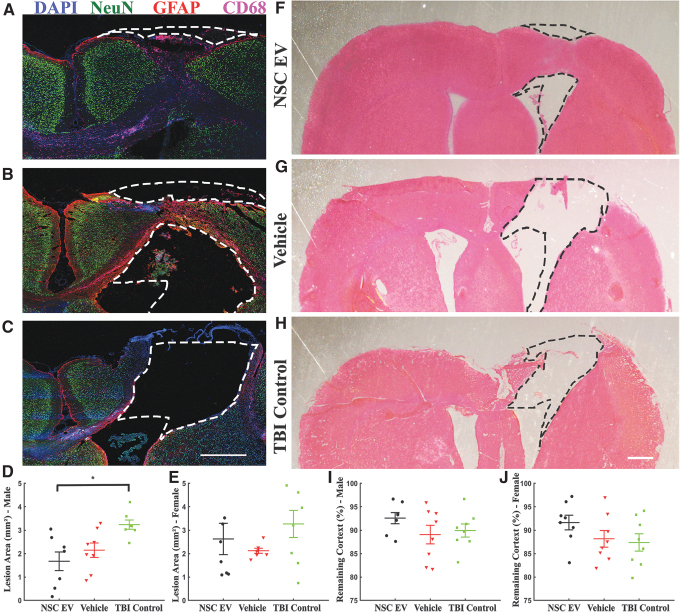

NSC EV treatment reduced lesion volume in both males and females

We examined whether acute intravenous administration of NSC EVs would help to reduce TBI lesion area in a rat TBI model. Rats received a CCI injury targeting the left hindlimb motor cortex, followed by three NSC EV injections at 6-h, 24-h, and 48-h intervals of either NSC EVs or vehicle (isotonic PBS; Fig. 1). Isotonic PBS was chosen as the vehicle in accordance with standard EV isolation protocols (see the Methods section), and TBI control rats did not receive any injections. We terminally quantified the average lesion area for each group at the end of 4 weeks (Fig. 2). Using direct quantification of the lost tissue area at 4 weeks post-injury compared with the contralateral hemisphere (Fig. 2D), we observed a decreased lesion area in NSC EV-treated males (1.675 ± 0.398 mm2; p = 0.011, one-way ANOVA) compared with vehicle-treated males (2.147 ± 0.308 mm2; p = 0.054) and control TBI males (3.237 ± 0.193 mm2; p = 0.011). We detected a marginal increase in spared tissue (spared tissue as a percentage of remaining cortex; Fig. 2F-H) in the NSC EV-treated group (Fig. 2I; 90.692 ± 2.192%) compared with both vehicle-treated (89.052 ± 1.986%) and TBI control (89.925 ± 1.400%) males. NSC EV-treated females also demonstrated reduction in lesion sizes and increase in spared tissue, although no significant differences were found (Fig. 2E and Fig. 2J; p = 0.250, one-way ANOVA). Additionally, in contrast to TBI control and vehicle-treated rats, which mostly exhibited tissue cavitation at the site of impact (Fig. 2B, 2C), NSC EV-treated rats exhibited maintenance of the cortical structure with a majority of the tissue consisting of CD68+ and GFAP+ cells and a minority of NeuN+ cells (Fig. 2A).

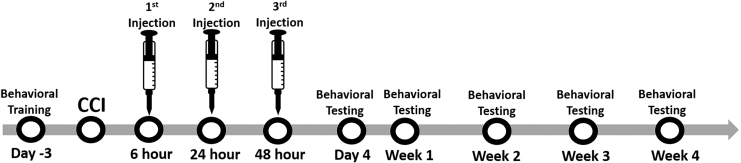

FIG. 1.

Experimental schedule. Animals were pre-trained on the beam-walk test prior to controlled cortical impact (CCI) induction. Following behavioral pre-training, a left hindlimb deficit was induced via CCI to the rat motor cortex. Animals were randomly assigned to one of the following treatment groups: neural stem cell–derived extracellular vesicle (NSC EV), vehicle, or TBI control. Three doses of NSC EV (4e10 EVs/kg) or vehicle at 6 h, 24 h, and 48 h post-CCI were injected via tail vein. No injections were administered to the traumatic brain injury control rats following CCI. Behavioral assessment was performed on 4, 7, 14, 21, and 28 days post-CCI.

FIG. 2.

Acute intravenous administration of neural stem cell–derived extracellular vesicles (NSC EVs) reduced tissue loss in male traumatic brain injury (TBI) rats. Contralateral hemisphere was overlaid to the injured hemisphere to outline the lesion and to estimate the volume of tissue lost. Representative images of (A) male NSC EV-treated, (B) male vehicle-treated, and (C) male control brain tissue stained for neurons (NeuN; green), reactive astrocytes (glial fibrillary acidic protein; red), macrophages and microglia (CD68; magenta) and 4′,6-diamidino-2-phenylindole counterstain (blue). Scale bar = 1 mm. (D, E) NSC EV-treated rats demonstrated a significant decrease in lost tissue compared with TBI control rats; females showed a similar, although non-significant, trend to males. Representative hematoxylin and eosin stained images of (F) male NSC EV-treated, (G) male vehicle-treated, and (H) male control brain tissue. Scale bar = 500 μm. (I, J) NSC EV-treated rats demonstrated a marginal increase in preserved tissue compared with vehicle-treated or TBI control rats in both males and females. *p < 0.05. Color image is available online.

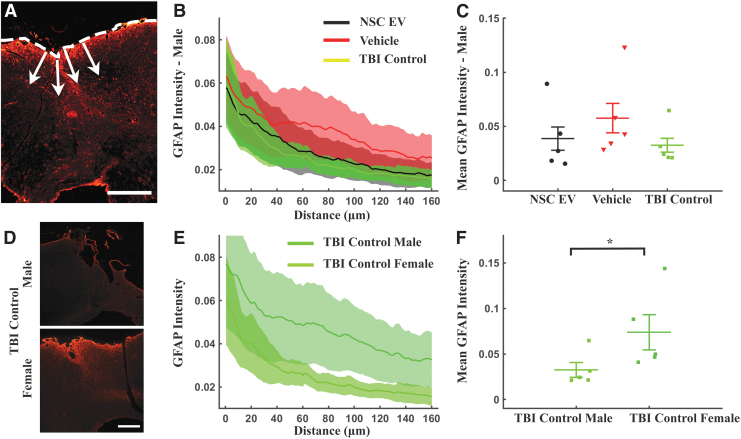

NSC EV treatment had little effect on GFAP expression

We quantified the fluorescence intensity of GFAP+ astroglial scar across all groups and treatments using lines drawn perpendicularly to the tangent of the TBI penumbra (Fig. 3A) and plotted the integrated GFAP+ intensity as the intensity summation over a distance of 160 μm (Fig. 3B, 3E). Expectedly, we observed a monotonic decrease in GFAP expression from the site of injury over a 160 μm distance across all treatment groups (Fig. 3B, 3E). Average GFAP expression in the perilesional area showed no significant difference in males (p = 0.281, ANOVA on ranks; Fig. 3C). However, male vehicle-treated rats (0.0574 ± 0.0172) expressed relatively higher expression of GFAP indicating thicker scarring of the tissue, in comparison to NSC EV-treated (0.0386 ± 0.0135) and control (0.0324 ± 0.0082). No treatment effect was also detected on GFAP expression among female groups (p = 0.181, ANOVA on ranks, data not shown). Interestingly, the overall GFAP intensity was higher in female TBI control rats (0.0739 ± 0.0197), compared with male TBI control (0.0324 ± 0.0082, p = 0.0422, t-test; Fig. 3D-F).

FIG. 3.

Neural stem cell–derived extracellular vesicle (NSC EV) treatment did not affect local glial fibrillary acidic protein (GFAP) expression. (A) Fluorescence intensity values were obtained along lines (arrows) drawn perpendicularly to the lesion (dashed line) and to a distance of 160 μm away from the lesion site. Scale bar = 500 μm. (B) The GFAP intensity values from the impact site (0 μm) to 160 μm away from the center of the injury demonstrated decreasing expression of GFAP in male groups. (C) Mean intensity in the perilesional area showed no significant differences in GFAP intensity across three treatment groups in male rats. (D) Representative images of GFAP staining intensity differences in male traumatic brain injury (TBI) control (upper) and female TBI control (lower) brain tissue. Scale bar = 200 μm. (E, F) The mean intensity in the perilesional GFAP response following TBI was lower over the entire depth in TBI control males compared with females indicating intrinsic gender differences. *p < 0.05. Color image is available online.

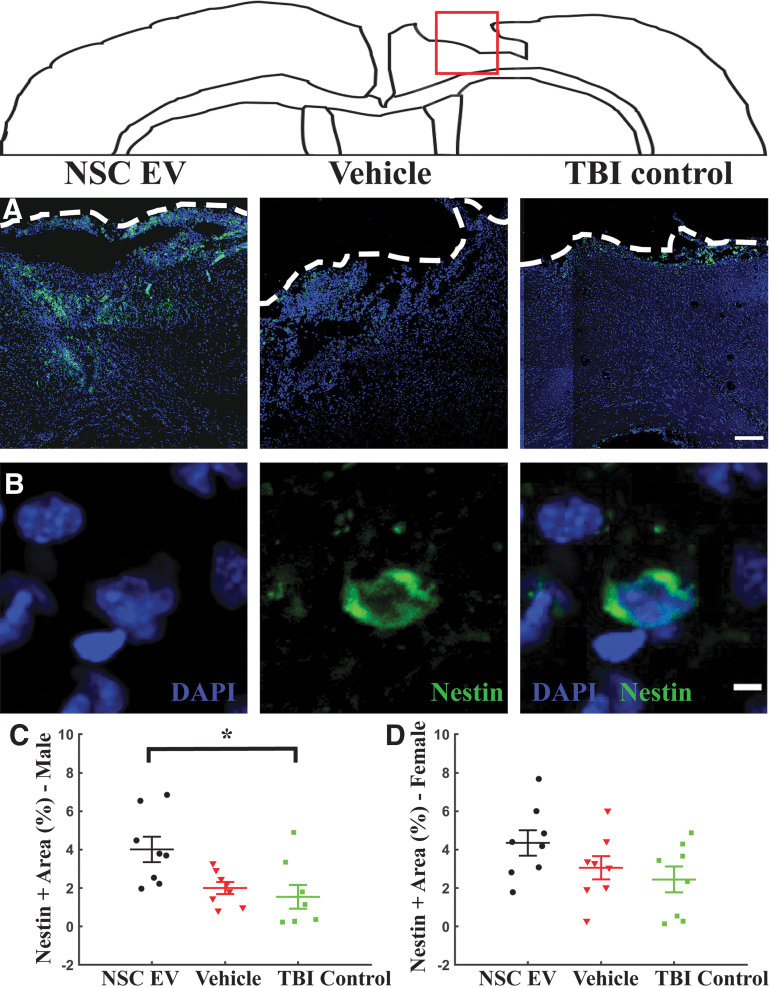

NSC EV treatment enhanced the presence of NSCs near the lesion site

We quantified the effects of NSC EV treatment on the presence of NSCs around the site of injury using nestin immunostaining (Fig. 4). Expression of nestin in NSC EV-treated male rats at the perilesional area was significantly enhanced (Fig. 4C; 4.01 ± 0.66%; p = 0.011, one-way ANOVA) when compared with the TBI control male rats (1.54 ± 0.61%; p = 0.014, Bonferroni test), while a strongly trending increase also was observed when compared with vehicle-treated male rats (2.00 ± 0.31%; p = 0.053, Bonferroni test). Nestin expression among female groups exhibited a moderate trend in the same direction, with relatively higher nestin expression observed in NSC EV-treated female rats (Fig. 4D; 4.35 ± 0.66%), followed by vehicle-treated (3.06 ± 0.70%), and TBI control female rats (2.44 ± 0.68%); however, these results were not statistically significant despite the moderate trend (p = 0.145, one-way ANOVA). These results suggest that NSC EVs promoted endogenous NSC migration to the site of injury in males, a response to injury that has been noted previously.21 We subsequently performed two-dimensional scratch wound assays on human NSCs and quantified NSC EV-dependent cell migration (Supplementary Fig. S2). We observed that NSC EV treatment significantly increased migration into the scratch-induced lesion at the end of 48 h, with an average closure of 60.0 ± 3.5% observed in the NSC EV-treated group when compared with 48.2 ± 3.7% (Supplementary Fig. S2E; p = 0.0244, two-tailed t-test) for the untreated control group. These results indicate that NSC EV treatment enhanced cell migration within the scratch induced lesion, corroborating the observed enhanced migration of endogenous NSCs to the injury site.

FIG. 4.

Endogenous neural stem cell (NSC) presence was significantly enhanced by NSC-derived extracellular vesicle (NSC EV) treatment. Representative coronal brain section images corresponding to the red box surrounding the lesion area stained for (A) nestin (green) merged with 4′,6-diamidino-2-phenylindole counterstain (blue). White dashes outline injury penumbra. Scale bar = 250 μm. (B) Nestin staining at a higher magnification. Scale bar = 5 μm. (C) Quantification of the mean nestin expression over tissue area at the site of the injury revealed significantly increased nestin expression in NSC EV-treated male rats when compared with the TBI control males and a strongly trending increase over vehicle-treated males. (D) A similar trend was observed in female rats. *p < 0.05. Color image is available online.

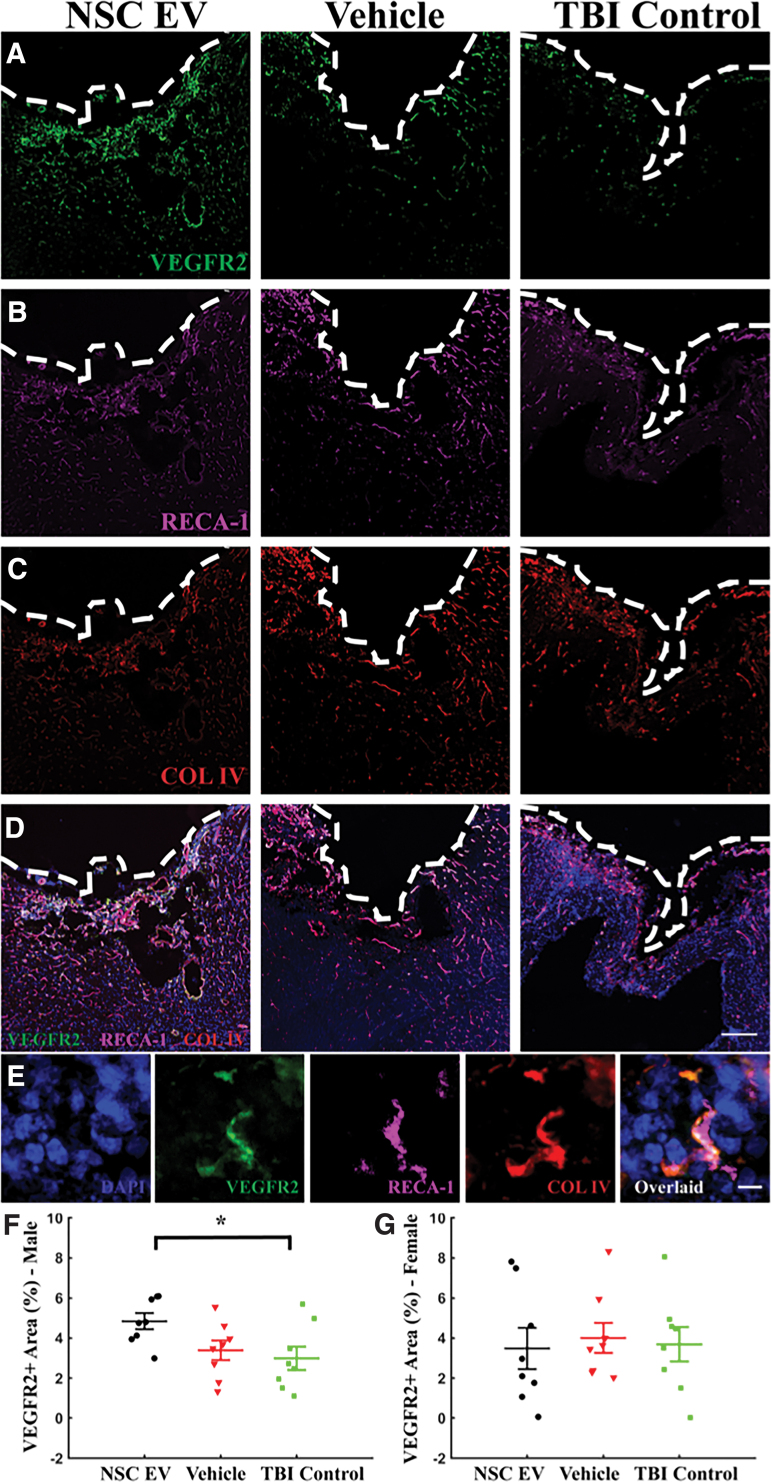

NSC EV treatment enhanced VEGFR2 expression around the lesion site in male rats

To analyze the effects of NSC EV treatment on angiogenesis and vascular density, we quantified the expression of sprouting endothelial cell marker, vascular endothelial growth factor receptor 2 (VEGFR2/Flk-1/KDR), as well as total endothelial markers RECA-1 and collagen IV (Col-IV) via immunohistochemistry (Fig. 5). In males, the NSC EV-treated group exhibited significantly increased VEGFR2 expression (Fig. 5F; 4.84 ± 0.40%; p = 0.038, one-way ANOVA) when compared with the TBI control group (2.99 ± 0.58%; p = 0.047, Bonferroni) and moderately increased VEGFR2 expression compared with the vehicle-treated group (3.39 ± 0.50%; p = 0.155, Bonferroni). In contrast, we did not observe differences in RECA-1 or Col-IV expression (p = 0.267, and p = 0.479, respectively, one-way ANOVA, n = 5 per group). In females, we did not detect any statistical differences in VEGFR2, RECA-1, or Col-IV (p = 0.617, p = 0.941, p = 0.525, respectively; one-way ANOVA; n = 8, 5, and 5, respectively) among the groups. Although NSC EV treatment significantly increased VEGFR2 expression in males, this increase did not result in a detectable increase of total vascular density at the 4-week experimental end-point as determined by RECA-1 and Col-IV expression. Interestingly, a positive correlation was revealed between VEGFR2 and nestin expression in male animals (Supplementary Fig. S3A; r = 0.632, p = 0.001, Pearson), while in females, no trend was detected (Supplementary Fig. S3B; r = -0.049, p = 0.820, Pearson).

FIG. 5.

Vascular endothelial growth factor receptor 2 (VEGFR2; Flk-1) staining showed an increased local VEGF activity in neural stem cell–derived extracellular vesicle (NSC EV)-treated male rats. Representative images of (A) VEGFR2 (green), (B) RECA-1 (magenta) and (C) COL IV (red) from each male treatment group. (D) All channels overlaid and counterstained with 4′,6-diamidino-2-phenylindole (blue). Scale bar = 250 μm. (E) At a higher magnification. Scale bar = 10 μm. (F) Enhanced local expression of VEGFR2 was observed in male NSC EV-treated rats, while (G) female rats showed no significant difference. *p < 0.05. Color image is available online.

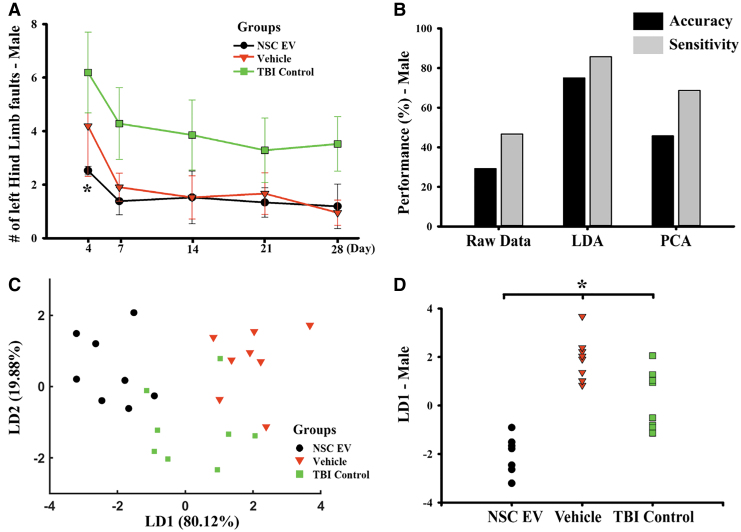

NSC EV treatment improved motor function recovery in male rats

Motor recovery of rats was assessed over a 4-week period using a beam-walk test to assess the impact of NSC EV injection on functional recovery in animals (Fig. 6). We observed a reduced number of left hindlimb faults in NSC EV-treated male rats on Day 4 post-TBI (Fig. 6A; 2.52 ± 0.16; two-way RM ANOVA), when compared with the TBI control group (6.19 ± 1.51; p = 0.046, Holm-Sidak), but only a slight non-significant reduction compared with the vehicle-treated group (4.19 ± 1.88; p = 0.258, Holm-Sidak). The difference in the number of left hindlimb faults among groups decreased over time, following a similar recovery trajectory.

FIG. 6.

Neural stem cell–derived extracellular vesicle (NSC EV) treatment significantly improved behavioral and global indexes of recovery in traumatic brain injury (TBI) males. (A) NSC EV-treated male rats subjected to a beam walk test exhibited motor function recovery. At Day 4, NSC EV-treated males exhibited significantly reduced motor balance deficit when compared with the TBI control, but not to vehicle-only controls. (B) Performance of a linear Fisher classification using raw data (11 variables), LDA dimensionality reduction (2 first components with highest explained variance) and PCA dimensionality reduction (2 first principal components with highest explained variance). LDA-based classification outperformed raw data and PCA. (C) Significant separation was observed between male NSC EV-treated, vehicle-treated and TBI control rats using LDA composite scores (dimensionality reduction). (D) Group separation using LD1 revealed significance. *p < 0.05. LDA, linear discriminant analysis; PCA, principal component analysis. Color image is available online.

Both lesion area and left hindlimb foot faults exhibited similar trends among groups, with the NSC EV-treated group retaining moderately more cortical tissue than the vehicle-treated and control groups as well as exhibiting slightly fewer left hindlimb faults. We therefore performed a regression analysis in order to investigate the correlation between lesion size and increased number of foot faults (Supplementary Fig. S4). The NSC EV-treated group showed a moderate correlation (r = -0.567, p = 0.185) with a strong negative slope, reflecting the expected relationship. The other two groups, however, had milder slopes, suggesting that for a given lesion size, NSC EV-treated animals showed improved recovery (fewer left hindlimb faults). While more investigation is needed to determine mechanisms, these results indicate that NSC EV treatment provided recovery benefits that cannot solely be predicted by lesion area or left hindlimb faults.

In accordance with our histological data, female rats demonstrated a rather complex recovery trend that was quite different from that observed in males (Supplementary Fig. S5A). Statistically significant differences were not detected on any tested day due to large variability within female treatment groups. Together, these results indicate that NSC EV injection acutely improved motor function recovery in NSC EV-treated males.

LDA demonstrated clustering of male NSC EV-treated rats

We used principal component analysis22 (PCA) and linear discriminant analysis (LDA)23 in an effort to reduce biomarkers (total number of markers = 11; sample size = 24) and achieve integrated visualization of changes following treatments (Fig. 6B-D). We limited our analysis to the first two components (Fig. 6B; correlation matrix-based model) of PCA and LDA modeling over the last day of the experiment (28 days) for correspondence between behavioral measures and histology. Classification using raw data (37.5% accuracy, 60.0% sensitivity), PCA-derived values (29.2% accuracy, 53.8% sensitivity), and LDA-derived values (75.0% accuracy, 53.8% sensitivity) suggested that LDA dimensionality reduction captures the effect of NSC EV treatment the best and was able to separate the group difference based on the given variables (Fig. 6B). We observed that the linear discriminant 1 (LD1, 80.12% explained variable) showed a significant separation in treatment groups (Fig. 6C, 6D; p < 0.001, one-way ANOVA) in males but not females (Supplementary Fig. S5). The LD1 major contribution was observed to be from variables measured in VEGFR2 and nestin expression. These results indicate that enhanced NSC mobilization is the major contributing factor in the recovery of NSC EV-treated males.

Discussion

NSC therapy has long been considered to hold great promise for TBI, although much of this evidence has been restricted to pre-clinical animal studies. The lack of clinical translation of NSC and other cell-based therapies for TBI could be attributed to an inadequate understanding of the mechanisms of repair, which, unlike pharmacological monotherapies, are multifaceted. Evidence suggests that NSC-mediated repair and neuroprotection takes effect not only due to cell replacement, but largely via secreted growth factors and NSC EVs carrying therapeutic genes and proteins.24,25 NSC EVs carry a cargo of neuroprotective proteins and RNA that have the potential to modulate the gene expression of recipient injured cells,26 which is one of the main therapeutic mechanisms of transplanted NSCs.27 NSC EVs do not require the same degree of technical skill, time, and expense that is required for NSC expansion, storage, and handling,28 but confer similar functional benefits and modulation of the injury environment.29 For all these reasons, NSC EVs have enormous potential for clinical translation. In this study, we explored the acute neuroprotective and functional benefits of administering NSC-derived EVs after TBI and observed sex-dependent neuroprotective effects of intravenously-delivered NSC EVs in age-matched male and female rats.

The substantial brain tissue loss that occurs immediately and in the days to weeks following a TBI leads to significant long-term functional impairments. Protecting the brain from undergoing long-term damage has been the focus of several pre-clinical and clinical studies. However, pharmacological agents designed to promote neuroprotection have largely failed in clinical trials, likely due to inadequate consideration of TBI severity, timing of administration and route of delivery, temporal assessment of functional outcomes, and the effects of age, sex, and other dependent variables.30 In the case of TBI, reduced time to definitive care leads to a better recovery trajectory.31 Further, temporal delays due to inaccessibility to emergency care, or time lost during injury evaluation could have significant long-term implications.32,33 The administration of NSC EVs could potentially serve as an effective neuroprotective agent in the critical care setting. Here, the neuroprotective effects of NSC EV treatment was demonstrated via significant behavioral and tissue level changes, including reduction of lesion size and increased VEGFR2 and nestin expression 4 weeks post-TBI. Interestingly, the analysis of lesion area in female rats revealed a large variation in therapeutic effect across groups, which may be related to the unsynchronized estrous cycle of female rats at the time of the CCI. Since female sex hormone concentrations at the time of injury induction has been demonstrated to have a prominent impact on TBI outcome,34,35 fluctuating hormone levels in female rats may have masked the treatment effects of NSC EVs.

Antibodies against GFAP are commonly used to mark activated astrocytes, which coalesce to form astroglial scar around central nervous system (CNS) injuries.36 The dogma that astroglial scarring inhibits axonal regeneration is now in debate. Contrary to its neurite-inhibiting qualities, the potential benefit of astroglial scarring in axon regeneration was recently demonstrated in spinal cord lesions.37 TBI induces clear gradients in the expression of reactive astrocytes from the injury site.38 These astrocytes are highly heterogeneous and are proposed to perform complex functions in immune modulation, BBB regulation, and neural circuit reorganization.38 Since hypertrophic reactive astrocytes selectively upregulate GFAP as a function of distance from the lesion site, we used line intensity analysis to accurately capture the spatial distribution of GFAP staining intensity from the lesion boundary to the perilesional space.39 Our results demonstrated that NSC EVs neither enhance nor reduce the expression of GFAP at the lesion site and this expression has no major implication in NSC EV mediated-recovery.

We speculate that this lack of difference in GFAP expression is likely due to the sub-acute, 4-week time course of study and the fact that scar composition and pro-inflammatory responses are still evolving during this period.40,41 Disparity between GFAP expression in male and female control TBI rats is expected due to fundamental structural differences in male and female brains.42 Studies addressing sexual dimorphism in glial activation following TBI suggest that inflammatory responses, including glial activation, differ in male and female brains. When compared with males, the age and estrous cycle of females are known to directly influence the increase, decrease, or maintenance of local GFAP expression at the lesion site.15,43 This complex regulation of GFAP response in female subjects makes it challenging to interpret the role of GFAP expression in terms of injury recovery outcome. Our study implies that GFAP expression associates differentially to functional recovery in male rats versus female rats following TBI. Although GFAP is widely accepted as a pro-inflammatory astroglial scarring response following TBI in pre-clinical studies, our results suggest that it is not a strong indicator of recovery at the 4-week sub-acute end-point after TBI as evaluated in this study.

EVs derived from mesenchymal stem cells have been previously shown to increase cell migration of multiple cell types.44,45 In addition, the presence of integrin involved in regulation of cell migration recently has been reported in NSC EVs.8,46 This observation, taken together with considerable evidence demonstrating that endogenous TBI repair mechanisms involve NSC migration to the perilesional area,47 is suggestive of the role of NSC EVs in enhancing endogenous NSC migration to the site of the injury. We have previously demonstrated the proclivity of NSC EVs to home to injured brain tissue in a rodent stroke model.48 Homing of NSC EVs to the lesion site suggests that NSC EVs also may contribute locally to neuroprotection and improved therapeutic outcomes, though further exploration is needed to determine specific mechanisms underlying these benefits. This implication also supports the suggestion that endogenous migrated NSCs exert neuroprotective effects at the lesion site via secretion of endogenous NSC EVs. Indeed, while endogenous migration was not directly examined, analysis of in vivo nestin immunohistochemistry (Fig. 4) in combination with the in vitro scratch wound assay (Supplementary Fig. S2) strongly suggested that NSC EVs promoted endogenous NSC migration. This increased presence of NSCs in the perilesional area could be one of the contributing factors to neuroprotective outcomes, as has been shown previously.21

An increase in NSC migration to the injured area may contribute to recovery via enhanced neurogenesis and paracrine effects, including endogenous NSC EV secretion from the migrated cells, similar to the repair mechanisms that have been reported in previous TBI studies.49 An increased level of proliferation and neurogenesis at the NSC niche and migration of NSCs to the injured cortex area have been reported after TBI.47 Stem cell-derived NSC EVs have been demonstrated to enhance endogenous neurogenesis and neurite outgrowth by microRNA (miRNA) transfer,50 suggesting miRNA transfer as a likely mechanism. However, the heterogeneity of NSC EV content renders the identification of a specific molecular pathway that leads to enhanced NSC migration challenging. Our results support these previous findings and suggest that NSC EV treatment directly contributes to the proliferation of locally-recruited NSCs, likely via similar mechanisms as reported previously. Further investigation is necessary to identify and characterize the relevant cargo in NSC EV for a better understanding of the mechanisms involved.

VEGF mediates many different receptor-specific functions, and binding of VEGF/VEGFR2 is implicated in elevation of mitogenic and angiogenic activities.51 VEGFR2 expressed in endothelial cells increases proliferation and migration upon binding, leading to neovascularization and vasculature rearrangement. Similarly, VEGFR2 expressed in NSCs supports the proliferation and migration of NSCs.52 Further, upregulation of VEGF and VEGFR2 around the lesion is associated with post-traumatic angiogenesis and neurogenesis after TBI.53,54 We observed a positive correlation between VEGFR2 and nestin expression around the site of injury in NSC EV-treated rats (Supplementary Fig. S3A) potentially suggesting an increase in VEGFR2-dependent NSC proliferation and recruitment after TBI, though NSC proliferation was not directly measured in this study. Although there was no detectable increase in vasculature density in the perilesional area, we cannot exclude the modulatory role VEGF plays on functional remodeling of vasculature, and vascular permeability.55 Taken together, NSC EV treatment increased VEGF/VEGFR2 activity, which we speculate may contribute to neuroprotection.

Since TBI lesions were induced in the primary motor cortex, we investigated the behavioral performance on a motor task and correlated the tissue-level changes to functional recovery following TBI. Overall, NSC EVs had an acute effect in reducing the severity of functional deficits over a 4-week period compared with the control group in males (Fig. 6). Pre-clinical and clinical studies for cell-based therapies have investigated the underlying mechanisms of stem cell-initiated cognitive and motor function recovery and confirmed that cell replacement is not the sole means of injury repair.56 The release of anti-inflammatory trophic factors, as well as gene and protein transfer by NSCs, also have been reported to contribute to functional repair of TBI.25 In addition to systemically-delivered NSC EVs, endogenous NSCs that migrate to the lesion site, which were identified via nestin expression, likely contribute to bystander signaling. Hence, functional recovery of TBI animals can be credited to the direct neuroprotective paracrine effect of NSC EVs, in combination with the endogenous NSC bystander effect indirectly enhanced by NSC EV treatment.

Using LDA, we assessed the combined effect of NSC EV treatment on immunohistochemical and behavioral changes. Females demonstrated no distinguishable differences in response to NSC EV treatment, while male NSC EV-treated rats showed separation from both the vehicle-treated and TBI control groups. In combination with individual null hypothesis testing (NHT)–based assessment, we confirmed that NSC EV treatment has a marked beneficial effect on male rats. The contributing variables that carried most of the weight in LD1 were related to the beam-walk test, indicating that NSC EV treatment had a pronounced effect on motor recovery that isolated NSC EV-treated rats from the other groups. Although individual beam-walk measurements may not appear significant in NHT-based tests, combining these measurements allowed us to reduce the intrinsic noise collected from biological data, and helped evaluate the true treatment effects.

In this study, the vehicle-treated male rats (injection control group) demonstrated an unexpected positive behavioral recovery, with trends that aligned closer to NSC EV-treated rats rather than TBI control rats at later time-points (Days 14, 21, and 28), which also is reflected in LDA. The Guidelines for the Management of Severe Traumatic Brain Injury indicates the use of osmotic therapy for the treatment for intracranial hypertension after TBI.57 While hypertonic solutions (i.e., hypertonic saline or mannitol) have been used extensively in an attempt to reduce intracranial pressure (ICP), recent sources suggest that reduction of ICP may not offer many significant benefits over isotonic solutions (particularly normal saline) and have associated concerns, such as increased infection risk.58–61 Results from isotonic fluid therapy studies in TBI patients suggest that there is indeed a therapeutic benefit of isotonic fluid therapy in restoring blood pressure and volume without substantial risk of increasing ICP (a primary concern with hypotonic solutions administration). In this study, isotonic PBS was used as vehicle, and we speculate that the acute systemic administration of a large volume of PBS (∼4.8 mL over 48 h) to TBI rats may have contributed to tissue protection and the moderate improvement in behavioral recovery observed in vehicle treated animals, when compared with TBI control rats.

Increasing attention is being paid to the role of sex differences in TBI outcomes. Clinical studies reveal inconsistent results relating injury severity and mortality in the female population in comparison to age-matched males, and yet female populations are understudied in pre-clinical research.11,12,62 Estrogen and progesterone can cross the blood–brain barrier, bind to hormone receptors widely expressed in the brain, and act as neuromodulators, reducing cell death and brain edema, and ultimately improving functional recovery in rodent TBI models.63 Estrogen and progesterone have been reported to provide neuroprotection post-TBI, although a large clinical trial recently concluded that there was no clinical benefit to progesterone treatment after severe TBI.16,63,64 In our study, we sought to include age-matched females with consideration for hormone-mediated disparities in TBI prognosis and potential responses to NSC EV-based treatment. TBI inductions were therefore intentionally not matched to the estrous cycle of females. The large variations in immunohistochemical and behavioral response observed within the female population are likely due to hormonal and neuroendocrine changes that took effect during the time course of the assessment. In conclusion, male rats responded more sensitively to NSC EV treatment, while NSC EV treatment appeared to have variable effects on females. From these results, we infer that female hormones might introduce significant effects and that additional studies would be required to fully elucidate these effects in future pre-clinical studies.

In conclusion, acute intravenous injections of human NSC EVs increased the migration of endogenous NSCs to the lesion site and increased VEGF activity in male TBI rats, which promoted recovery of motor function. The therapeutic benefit of NSC EVs following TBI was significant in male rats, but variable in females. The potential role of female sex hormones in masking the therapeutic effects of NSC EVs should be considered in the design of future studies evaluating the pre-clinical and clinical potential of NSC EV therapy for TBI.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

We would like to acknowledge Timothy Maughon, Brian Jurgielewicz, LaDonya Jackson, and Allison Andrews, for technical assistance with surgeries and behavioral testing.

Funding Information

This work was funded in part by a seed grant from the regenerative engineering in medicine (REM) partnership, and an NIH R01 award (R01NS099596) to LK.

Author Disclosure Statement

S.L.S. has submitted a patent filing on the NSC EVs, and this technology is licensed from the UGA Research Foundation by ArunA Biomedical, Inc. S.L.S. is affiliated with ArunA Biomedical, Inc. and owns equity in the company.

For the other authors, no competing financial interests exist.

Supplementary Material

References

- 1. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC). (2013). CDC grand rounds: reducing severe traumatic brain injury in the United States. MMWR Morb. Mortal. Wkly. Rep. 62, 549–552 [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Brooks J.C., Shavelle R.M., Strauss D.J., Hammond F.M., and Harrison-Felix C.L. (2015). Long-term survival after traumatic brain injury part II: life expectancy. Arch. Phys. Med. Rehabil. 96, 1000–1005 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Loane D.J. and Faden A.I.Neuroprotection for traumatic brain injury: translational challenges and emerging therapeutic strategies. (2010). Trends Pharmacol. Sci. 31, 596–604 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Reis C., Gospodarev V., Reis H., Wilkinson M., Gaio J., Araujo C., Chen S., and Zhang J.H. (2017). Traumatic brain injury and stem cell: pathophysiology and update on recent treatment modalities. Stem Cells Int. 2017, 6392592. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Haus D.L., López-Velázquez L., Gold E.M., Cunningham K.M., Perez H., Anderson A.J., and Cummings B.J. (2016). Transplantation of human neural stem cells restores cognition in an immunodeficient rodent model of traumatic brain injury. Exp. Neurol. 281, 1–16 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Xiong L.L., Hu Y., Zhang P., Zhang Z., Li L.H., Gao G.D., Zhou X.F., and Wang T.H. (2018). Neural stem cell transplantation promotes functional recovery from traumatic brain injury via brain derived neurotrophic factor-mediated neuroplasticity. Mol. Neurobiol. 55, 2696–2711 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Baraniak P.R. and McDevitt T.C. (2010). Stem cell paracrine actions and tissue regeneration. Regen. Med. 5, 121–143 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Webb R.L. Kaiser E.E., Jurgielewicz B.J., Spellicy S., Scoville S.L., Thompson T.A., Swetenburg R.L., Hess D.C., West F.D., and Stice S.L. (2018). Human neural stem cell extracellular vesicles improve recovery in a porcine model of ischemic stroke. Stroke 49, 1248–1256 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Webb R.L. Kaiser E.E., Scoville S.L., Thompson T.A., Fatima S., Pandya C., Sriram K., Swetenburg R.L., Vaibhav K., Arbab A.S., Baban B., Dhandapani K.M., Hess D.C., Hoda M.N., and Stice S.L. (2017). Human neural stem cell extracellular vesicles improve tissue and functional recovery in the murine thromboembolic stroke model. Transl. Stroke Res. 9, 530–539 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Lai C.P. and Breakefield X.O. (2012). Role of exosomes/microvesicles in the nervous system and use in emerging therapies. Front. Physiol. 3, 228. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Slewa-Younan S., Green A.M., Baguley I.J., Gurka J.A., and Marosszeky J.E. (2004). Sex differences in injury severity and outcome measures after traumatic brain injury. Arch. Phys. Med. Rehabil. 85, 376–379 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Munivenkatappa A., Agrawal A., Shukla D.P., Kumaraswamy D., and Devi B.I.Traumatic brain injury: does gender influence outcomes? (2016). Int. J. Crit. Illn. Inj. Sci. 6, 70–73 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Vagnerova K., Koerner I.P., and Hurn P.D. (2008). Gender and the injured brain. Anesth. Analg. 107, 201–214 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Caplan H.W., Cox C.S., and Bedi S.S. (2017). Do microglia play a role in sex differences in TBI? J. Neurosci. Res. 95, 509–517 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Villapol S., Loane D.J., and Burns M.P. (2017). Sexual dimorphism in the inflammatory response to traumatic brain injury. Glia 65, 1423–1438 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Raghava N., Das B.C., and Ray S.K. (2017). Neuroprotective effects of estrogen in CNS injuries: insights from animal models. Neurosci. Neuroecon. 6, 15–29 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Liang C.C., Park A.Y., and Guan J.L. (2007). In vitro scratch assay: a convenient and inexpensive method for analysis of cell migration in vitro. Nat. Protoc. 2, 329–333 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Betancur M.I., Mason H.D., Alvarado-Velez M., Holmes P.V., Bellamkonda R.V., and Karumbaiah L. Chondroitin sulfate glycosaminoglycan matrices promote neural stem cell maintenance and neuroprotection post-traumatic brain injury. (2017). ACS Biomater. Sci. Eng. 3, 420–430 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Fonoff E.T., Pereira J.F. Jr, Camargo L.V., Dale C.S., Pagano R.L., Ballester G., and Teixeira M.J. (2009). Functional mapping of the motor cortex of the rat using transdural electrical stimulation. Behav Brain Res. 202, 138–141 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Karumbaiah L., Saxena. T., Carlson D., Patil K., Patkar R., Gaupp E.A., Betancur M., Stanley G.B., Carin L., and Bellamkonda R.V. (2013). Relationship between intracortical electrode design and chronic recording function. Biomaterials 34, 8061–8074 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Dixon K.J., Theus M.H., Nelersa C.M., Mier J., Travieso L.G., Yu T.S., Kernie S.G., and Liebl D.J. (2015). Endogenous neural stem/progenitor cells stabilize the cortical microenvironment after traumatic brain injury. J. Neurotrauma 32, 753–764 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Lever J., Krzywinski M., and Atman N. (2017). Points of significance: principal component analysis. Nat. Methods 14, 641–642 [Google Scholar]

- 23. Liu L., Tang L., Dong W., Yao S., and Zhou W. (2016). An overview of topic modeling and its current applications in bioinformatics. Springerplus 5, 1608. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Yamashita T., Takahashi Y., and Takakura Y. (2018). Possibility of exosome-based therapeutics and challenges in production of exosomes eligible for therapeutic application. Biol. Pharm. Bull. 41, 835–842 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Gennai S., Monsel A., Hao Q., Liu J., Gudapati V., Barbier E.L., and Lee J.W,. (2015). Cell-based therapy for traumatic brain injury. Br. J. Anaesth. 115, 203–212 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Valadi H., Ekström K., Bossios A., Sjöstrand M., Lee J.J., and Lötvall J.O. (2007). Exosome-mediated transfer of mRNAs and microRNAs is a novel mechanism of genetic exchange between cells. Nat. Cell. Biol. 9, 654–659 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Reekmans K., Praet J., Daans J., Reumers V., Pauwels P., Van der Linden A., Berneman Z.N., and Ponsaerts P. (2012). Current challenges for the advancement of neural stem cell biology and transplantation research. Stem Cell Rev. 8, 262–278 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Driscoll D., Farnia S., Kefalas P., and Maziarz R.T. (2017). Concise review: the high cost of high tech medicine: planning ahead for market access. Stem Cells Transl. Med. 6, 1723–1729 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Sutterlin C.E., 3rd Field, A., Ferrara L.A., Freeman A.L., and Phan K. (2016). Range of motion, sacral screw and rod strain in long posterior spinal constructs: a biomechanical comparison between S2 alar iliac screws with traditional fixation strategies. J. Spine Surg. 2, 266–276 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Zoerle T., Carbonara M., Zanier E.R., Ortolano F., Bertani G., Magnoni S., and Stocchetti N. (2017). Rethinking neuroprotection in severe traumatic brain injury: toward bedside neuroprotection. Front. Neurol. 8, 354. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Hammell C.L. and Henning J.D. (2009). Prehospital management of severe traumatic brain injury. BMJ 338. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Matsushima K., Inaba K., Siboni S., Skiada D., Strumwasser A.M., Magee G.A., Sung G.Y., Benjaminm E.R., Lam L., and Demetriades D. (2015). Emergent operation for isolated severe traumatic brain injury: does time matter? J. Trauma Acute Care Surg. 79, 838–842 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Kejriwal R. and Civil I. (2009). Time to definitive care for patients with moderate and severe traumatic brain injury—does a trauma system matter? N. Z. Med. J. 122, 40–46 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Maghool F., Khaksari M., and Siahposht Khachki A. (2013). Differences in brain edema and intracranial pressure following traumatic brain injury across the estrous cycle: involvement of female sex steroid hormones. Brain Res. 1497, 61–62 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Wagner A.K., Willard L.A., Kline A.E., Wenger M.K., Bolinger B.D., Ren D., Zafonte R.D., and Dixon C.E. (2004). Evaluation of estrous cycle stage and gender on behavioral outcome after experimental traumatic brain injury. Brain Res. 998, 113–121 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Sofroniew M.V. and Vinters H.V. (2010). Astrocytes: biology and pathology. Acta Neuropathol. 119, 7–35 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. Anderson M.A., Burda J.E., Ren Y., Ao Y., O'Shea T.M., Kawaguchi R., Coppola G., Khakh B.S., Deming T.J., and Sofroniew M.V. (2016). Astrocyte scar formation aids central nervous system axon regeneration. Nature 532, 195–200 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38. Burda J.E., Bernstein A.M., and Sofroniew M.V. (2016). Astrocyte roles in traumatic brain injury. Exp. Neurol. 275 Pt 3, 305–315 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39. Karumbaiah L., Saxena T., Carlson D., Patil K., Patkar R., Gaupp E.A., Betancur M., Stanley G.B., Carin L., and Bellamkonda R.V. (2013). Relationship between intracortical electrode design and chronic recording function. Biomaterials 34, 8061–8074 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40. Villapol S., Byrnes K.R., and Symes A.J. (2014). Temporal dynamics of cerebral blood flow, cortical damage, apoptosis, astrocyte-vasculature interaction and astrogliosis in the pericontusional region after traumatic brain injury. Front. Neurol. 5, 82. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41. Erturk A., Mentz S., Stout E.E., Hedehus M., Dominguez S.L., Neumaier L., Krammer F., Llovera G., Srinivasan K., Hansen D.V., Liesz A., Scearce-Levie K.A., and Sheng M. (2016). Interfering with the chronic immune response rescues chronic degeneration after traumatic brain injury. J. Neurosci. 36, 9962–9975 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42. Rabinowicz T., Petetot J.M., Gartside P.S., Sheyn D., Sheyn T., and de C.M. (2002). Structure of the cerebral cortex in men and women. J. Neuropathol. Exp. Neurol. 61, 46–57 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43. Acaz-Fonseca E., Duran J.C., Carrero P., Garcia-Segura L.M., and Arevalo M.A. (2015). Sex differences in glia reactivity after cortical brain injury. Glia 63, 1966–1981 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44. Sung B.H., Ketova T., Hoshino D., Zijlstra A., and Weaver A.M. (2015). Directional cell movement through tissues is controlled by exosome secretion. Nat. Commun. 6, 7164. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45. Shabbir A., Cox A., Rodriguez-Menocal L., Salgado M., and Van Badiavas E. (2015). Mesenchymal stem cell exosomes induce proliferation and migration of normal and chronic wound fibroblasts, and enhance angiogenesis in bitro. Stem Cells Dev. 24, 1635–1647 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46. Webb D.J., Parsons J.T., and Horwitz A.F. (2002). Adhesion assembly, disassembly and turnover in migrating cells—over and over and over again. Nat. Cell. Biol. 4, E97–100 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47. Chang E.H. Adorjan I., Mundim M.V., Sun B., Dizon M.L., and Szele F.G. (2016). Traumatic brain injury activation of the adult subventricular zone neurogenic niche. Front. Neurosci. 10, 332. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48. Webb R.L., Kaiser E.E., Scoville S.L., Thompson T.A., Fatima S., Pandya C., Sriram K2, Swetenburg R.L., Vaibhav K., Arbab A.S., Baban B., Dhandapani K.M., Hess D.C., Hoda M.N., and Stice S.L. (2018). Human neural stem cell extracellular vesicles improve tissue and functional recovery in the murine thromboembolic stroke model. Transl. Stroke Res. 9, 530–539 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49. Addington C.P., Roussas A., Dutta D., and Stabenfeldt S.E. (2015). Endogenous repair signaling after brain injury and complementary bioengineering approaches to enhance neural regeneration. Biomark. Insights 10, 43–60 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50. Xin H., Li Y., Buller B., Katakowski M., Zhang Y., Wang X., Shang X., Zhang Z.G., and Chopp M. (2012). Exosome-mediated transfer of miR-133b from multipotent mesenchymal [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 51. Nowacka M.M. and Obuchowicz E. (2012). Vascular endothelial growth factor (VEGF) and its role in the central nervous system: a new element in the neurotrophic hypothesis of antidepressant drug action. Neuropeptides 46, 1–10 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52. Wittko-Schneider I.M., Schneider F.T., and Plate K.H. (2013). Brain homeostasis: VEGF receptor 1 and 2-two unequal brothers in mind. Cell. Mol. Life Sci. 70, 1705–1725 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53. Skold M.K., von Gertten C., Sandberg-Nordqvist A.C., Mathiesen T., and Holmin S. (2005). VEGF and VEGF receptor expression after experimental brain contusion in rat. J. Neurotrauma 22, 353–367 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54. Lee C. and Agoston D.V. (2010). Vascular endothelial growth factor is involved in mediating increased de novo hippocampal neurogenesis in response to traumatic brain injury. J. Neurotrauma 27, 541–553 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55. Ma Y., Zechariah A., Qu Y., and Hermann D.M. (2012). Effects of vascular endothelial growth factor in ischemic stroke. J. Neurosci. Res. 90, 1873–1882 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56. Harting M.T., Baumgartner J.E., Worth L.L., Ewing-Cobbs L., Gee A.P., Day M.C., Cox C.S. Jr. (2008). Cell therapies for traumatic brain injury. Neurosurg. Focus 24, E18. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57. Haddad S.H. and Arabi Y.M. (2012). Critical care management of severe traumatic brain injury in adults. Scand. J. Trauma Resusc. Emerg. Med. 20, 12. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58. Bhatoe H.S. (2005). Intravenous fluids in head injury. Indian J. Neurotraum 2, 1–2 [Google Scholar]

- 59. Zornow M.H. and Prough D.S. (1995). Fluid management in patients with traumatic brain injury. New Horiz. 3, 488–498 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60. Qureshi A.I., Suarez J.I., Castro A., and Bhardwaj A. (1999). Use of hypertonic saline/acetate infusion in treatment of cerebral edema in patients with head trauma: experience at a single center. J. Trauma 47, 659–665 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61. Coritsidis G., Diamond N., Rahman A., Solodnik P., Lawrence K., Rhazouani S., and Phalakornkul S. (2015). Hypertonic saline infusion in traumatic brain injury increases the incidence of pulmonary infection. J. Clin. Neurosci. 22, 1332–1337 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62. Wright D.W., Espinoza T.R., Merck L.H., Ratcliff J.J., Backster A., and Stein D.G. (2014). Gender differences in neurological emergencies part II: a consensus summary and research agenda on traumatic brain injury. Acad. Emerg. Med. 21, 1414–1420 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63. Brotfain E., Gruenbaum S.E., Boyko M., Kutz R., Zlotnik A., and Klein M. (2016). Neuroprotection by estrogen and progesterone in traumatic brain injury and spinal cord injury. Curr. Neuropharmacol. 14, 641–653 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64. Wei J. and Xiao G.M. (2013). The neuroprotective effects of progesterone on traumatic brain injury: current status and future prospects. Acta Pharmacol. Sin. 34, 1485–1490 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.