Abstract

Background:

Coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) caused by the novel severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2 (SARS-CoV-2) has rapidly become pandemic, with substantial mortality.

Objective:

To evaluate the pathologic changes of organ systems and the clinicopathologic basis for severe and fatal outcomes.

Design:

Prospective autopsy study.

Setting:

Single pathology department.

Participants:

11 deceased patients with COVID-19 (10 of whom were selected at random for autopsy).

Measurements:

Systematic macroscopic, histopathologic, and viral analysis (SARS-CoV-2 on real-time polymerase chain reaction assay), with correlation of pathologic and clinical features, including comorbidities, comedication, and laboratory values.

Results:

Patients' age ranged from 66 to 91 years (mean, 80.5 years; 8 men, 3 women). Ten of the 11 patients received prophylactic anticoagulant therapy; venous thromboembolism was not clinically suspected antemortem in any of the patients. Both lungs showed various stages of diffuse alveolar damage (DAD), including edema, hyaline membranes, and proliferation of pneumocytes and fibroblasts. Thrombosis of small and mid-sized pulmonary arteries was found in various degrees in all 11 patients and was associated with infarction in 8 patients and bronchopneumonia in 6 patients. Kupffer cell proliferation was seen in all patients, and chronic hepatic congestion in 8 patients. Other changes in the liver included hepatic steatosis, portal fibrosis, lymphocytic infiltrates and ductular proliferation, lobular cholestasis, and acute liver cell necrosis, together with central vein thrombosis. Additional frequent findings included renal proximal tubular injury, focal pancreatitis, adrenocortical hyperplasia, and lymphocyte depletion of spleen and lymph nodes. Viral RNA was detectable in pharyngeal, bronchial, and colonic mucosa but not bile.

Limitation:

The sample was small.

Conclusion:

COVID-19 predominantly involves the lungs, causing DAD and leading to acute respiratory insufficiency. Death may be caused by the thrombosis observed in segmental and subsegmental pulmonary arterial vessels despite the use of prophylactic anticoagulation. Studies are needed to further understand the thrombotic complications of COVID-19, together with the roles for strict thrombosis prophylaxis, laboratory, and imaging studies and early anticoagulant therapy for suspected pulmonary arterial thrombosis or thromboembolism.

Primary Funding Source:

None.

The clinicopathological basis for morbidity and mortality with SARS-CoV-2 infection is not well understood. This study reports the clinical and autopsy findings of patients who died of COVID-19.

The pandemic spread of the severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2 (SARS-CoV-2) causing coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) has, within a few months, led to a global health and economic crisis (1–3). COVID-19 is usually characterized by symptoms of acute respiratory infection, such as fever, headache, dry cough, and shortness of breath, but may show further symptoms involving the gastrointestinal tract (gastroenteritis-like, with vomiting and diarrhea, or a hepatitis-like picture) and the central nervous system (most notably anosmia) (4–8). Only a small subset of infected individuals becomes severely ill, requiring intensive care and with risk for death, but this number may increase dramatically through the high transmission rate of the virus (8–10). Although advanced age and certain comorbid conditions, such as diabetes mellitus and cardiovascular diseases, have been identified as risk factors for adverse outcome and death, the individual clinical course can be highly unpredictable and dynamic, with rapid deterioration of the respiratory and hemodynamic condition (10–14).

So far, very little is known about the pathologic findings underlying the clinical presentation of severe COVID-19. Only a few reports on surgical specimens and autopsy cases have been published over the past few months, and detailed information is still limited (15–17) and was in part obtained by postmortem core biopsies (18, 19). More insights from autopsies have become available from the 2003 SARS-CoV-1 epidemic, showing that patients with fatal outcome predominantly had diffuse alveolar damage characterized by edema, hyaline membranes, and proliferation of pneumocytes and fibroblasts (20). Nevertheless, the pattern of organ damage caused by SARS-CoV-2 and occurring in patients with COVID-19 is still incompletely understood. In light of the currently limited options for effective antiviral treatment, it may be critical to better understand the morphologic basis for severe and fatal COVID-19 outcomes (21).

The aim of this detailed autopsy study was to unravel the clinicopathologic basis for adverse outcomes in patients with a fatal course of COVID-19 by evaluating the gross and microscopic findings in correlation with their clinical phenotypes. We used a prospectively designed systematic approach to perform the autopsies and to study organ changes macro- and microscopically and relate them to key clinical features. Moreover, we provide a comprehensive and systematic clinicopathologic evaluation of key multiorgan involvement and failure in COVID-19.

Methods

Case Selection and Autopsy Material

The study was prospectively designed, and all autopsies on patients with COVID-19 in our hospital were done according to the same protocol.

The Hospital Graz II is the second largest public and academic teaching hospital in the region of Styria, Austria (1.2 million inhabitants) and was designated the COVID-19 center of the region at the beginning of the outbreak of the pandemic. From 28 February to 14 April 2020, 242 patients with COVID-19 were treated in our hospital, of whom 48 died. Autopsy was performed in 11 of the 48 deceased patients (23%), of whom 10 were selected at random; in 1 case, the treating intensive care specialist requested autopsy. The number of patients randomly selected for autopsy was influenced by the daily number of deceased patients, together with our infrastructural, time, and personnel constraints. There were no medical exclusion criteria. According to federal Austrian hospital law, an autopsy in a public hospital is mandatory without requirement of an informed consent by the relatives when the cause of death is unclear, scientific or public interest is present, or health authorities or a court order the autopsy. Nevertheless, religious reasons or an explicit wish from the patients' relatives to abstain from autopsy would be respected, if possible. In this study, autopsy was performed in accordance with the law owing to the unknown cause of death, and to both scientific and public interest in a novel disease. No informed consent was obtained from the families. All performed procedures and investigations were in accordance with the ethical standards of the institutional research committee and with the 1964 Declaration of Helsinki and its later amendments.

All patients fulfilled the World Health Organization criteria for COVID-19 (www.who.int).and presented with fever and acute respiratory symptoms, including cough, dyspnea, and hypoxia on pulse oximetry. All tested positively for SARS-CoV-2 RNA by polymerase chain reaction (PCR) assay either before or at admission to our hospital. The clinical information was retrieved from the electronic files of the hospital information system (MEDOCS) of the Styrian hospital corporation and was carefully reviewed by 2 of the treating specialists for internal medicine.

Swabs were collected by using the Copan ESwab collection system containing 1 mL of transport medium. Samples were tested for SARS-CoV-2 RNA at the Molecular Diagnostics Laboratory, Medical University of Graz, within 12 hours of arrival. Presence of SARS-CoV-2 RNA was determined by real-time PCR using the in vitro diagnostics/Conformité Européenne–labeled Cobas SARS-CoV-2 Test (Roche) for use on the Cobas 6800/8800 Systems (Roche Molecular Diagnostics) (22, 23). Selective amplification of target nucleic acid from the sample was achieved by the use of target-specific forward and reverse primers for ORF1a/b nonstructural region that is unique to SARS-CoV-2. In addition, a conserved region in the structural protein envelope E-gene was chosen for pan-Sarbecovirus detection. The pan-Sarbecovirus detection sets also detect SARS-CoV-2 virus.

Autopsy Procedure

To reduce the probability of transmission of active virus, the autopsies were performed at earliest 48 hours after death. For the autopsies, we used protective measures similar to those used when caring for our patients with COVID-19, according to World Health Organization guidelines (https://app.who.int). The same team carried out all autopsies. The autopsy procedure was consistent for all cases and consisted of removal of the thoracic situs and a modified in situ technique for the abdominal situs. The brain was dissected in only 1 patient, in whom a cerebral insult was suspected. During the autopsy, swabs for SARS-CoV-2 RNA testing were taken from the pharynx and both lungs (bronchial system) as well as the gallbladder and the colon.

Tissue Processing for Histopathologic Examination

The lungs in total and tissue samples from other organs (heart, kidneys, liver, pancreas, spleen, thyroid, submandibular glands, adrenals, gallbladder, small and large intestine) were fixed in 4% buffered formalin for histopathologic examination. After fixation, the lungs were dissected systematically from the apex to the basis and multiple samples were processed for histopathologic examination (hematoxylin and eosin and special stains). Immunohistochemistry was performed on a Ventana BenchMark Ultra system.

Role of the Funding Source

The study did not receive funding.

Results

Clinical Findings

Key clinical findings are summarized in Table 1. The age of the patients undergoing autopsy ranged from 75 to 91 years (median, 80.5 years; mean, 81.5 years); 8 patients were male, and 3 were female. The duration of COVID-19 disease ranged from 4 to 18 days (mean, 8.5 days). Among coexisting diseases, arterial hypertension (9 patients) and type 2 diabetes mellitus (5 patients) were most common, followed by cerebrovascular disease (history of ischemic stroke in 4 patients) and dementia (4 patients). Chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD), coronary heart disease, history of malignant disease (Hodgkin lymphoma and transitional cell carcinoma of the urinary bladder) were also present; 1 patient had a history of pulmonary embolism. Body mass index (BMI) could only be assessed in 3 of the 11 patients, but nutritional status was routinely assessed during the inspection of the corps before the autopsy. Two patients were considered obese, of whom 1 had a BMI of 33 kg/m2; the other 9 were considered in good nutritional status, 2 of whom had a BMI of 27 kg/m2 and 30 kg/m2.

Table 1. Clinical and Laboratory Characteristics.

Of the whole group of 48 deceased patients (all of whom were white), 30 were male and 18 female, with a mean age of 81.75 years (range, 66 to 94 years); 14 had a history of a cerebrovascular stroke, 14 had coronary artery disease, 21 had a history of diabetes, 36 had arterial hypertension, 11 had chronic respiratory diseases (COPD), 7 had pulmonary embolism, and 12 had a history of previous malignant diseases.

Because of severe comorbidities, 2 of the patients were treated in the intensive care unit, including invasive mechanical ventilation; the others were treated in a dedicated hospital ward for infectious diseases, where they received oxygen and nasal high-flow therapy using the AIRVO 2 system (Fisher & Paykel Healthcare Systems). The selection of patients for intensive care was discussed daily by an institutional review board, including 2 intensivists and the attending physician of the special ward.

Clinical laboratory data after admission are shown in Table 1. Frequent findings were lymphopenia; low eosinophil and monocyte values; and reduced erythrocyte count, hemoglobin, and hematocrit. Levels of C-reactive protein, ferritin, procalcitonin, liver enzymes, and lactate dehydrogenase were frequently elevated. Renal function was frequently abnormal. Fibrinogen and D-dimer levels were also frequently elevated, but the Quick value, international normalized ratio, and activated partial thromboplastin time were rarely abnormal.

Chest radiography was performed in 9 patients and showed features of bilateral (5 of 8 patients) or unilateral (3 of 8 patients) pneumonia; 1 patient showed no clear pneumonic changes. Echocardiograms were normal or had nonspecific findings; 2 patients had left bundle branch block, and no patient showed signs of cardiac ischemia. Venous thromboembolic disease was not suspected antemortem in any of the patients.

Concomitant medication use is shown in Appendix Table 1 (available at Annals.org). Notably, all patients received either anticoagulant or antiaggregant therapy or a combination of both. Two patients received anticoagulant therapy before admission because of history of pulmonary embolism (1 patient) and recent orthopedic surgery (1 patient). Antiaggregant therapy was given in 7 patients before admission because of cardiovascular or cerebrovascular disorders. The anticoagulants received before or after admission were exclusively at prophylactic doses. Individual treatment of preexisting chronic medical illnesses before acquisition of COVID-19 included ACE inhibitors or AT1-receptor blockers or sartans, antidiabetic drugs or insulin, statins, and xanthine oxidase inhibitors. Appendix Table 1 also shows the medications patients received during hospitalization on a COVID-19 ward or in the intensive care unit: antipyretics, antimicrobials (mostly β-lactams, carbapenems, and macrolides, as well as hydroxychloroquine in 3 patients), sedatives or muscle relaxants, and vasopressors, among others.

Appendix Table 1. Use of Concomitant and COVID-19–Related Medications.

Pathologic Findings

Table 2 shows the key pathologic findings.

Table 2. Pathologic Findings.

Lungs

Weight ranged from 420 g to 1460 g (mean, 998 g) for the right lung and from 340g to 1200 g (mean, 795 g) for the left lung (normal weights for each lung lobe are 180 g ± 57 g, as determined radiologically and postoperatively) (24). Macroscopically, we found a similar appearance in 9 of the patients, showing massive bilateral congestion and hypostasis with reddish-blue surface and cut surface except for the anterior and apical segments as well parts of the medium lobe and the lingula, which were grayish-red and better ventilated. In the 2 remaining patients, the lungs were well ventilated, except for atelectasis and mild hypostasis in the dorsobasal segments. Moderate emphysematous changes were seen diffusely in all lungs, with severe emphysema in 3 patients. The bronchial system contained in most cases viscous mucus. The pleura was inconspicuous except for fibrous adhesions in 7 patients, pleural effusion was absent in all but 1 patient which showed 20 mL of serous effusion. The most striking feature was the presence of thrombotic material in branches of the pulmonary arteries in all cases. These findings varied in extent from focal to extensive (Figure 1, A), and pulmonary infarctions were present in all but 3 patients (Figure 1, B). Vessels of all size were involved, and the thrombotic material was often grossly visible, particularly after formalin fixation of the lung tissue (Figure 1, A and B).

Figure 1.

Pulmonary thrombosis. A.

A cross-section through the lung shows massive thrombosis of medium-sized to large arteries (arrows). B. A peripheral artery and its branches (arrows) are obliterated by thrombosis, and the supplied region is infarcted (asterisks). Note the emphysematous changes in both lungs (formalin-fixed specimens).

Histologically, the lungs showed a heterogeneous pattern of changes, with different stages of diffuse alveolar damage with edema, hyaline membranes, and proliferation of pneumocytes and fibroblasts (Figure 2, A to C). Hyaline membranes were found in all cases, and in areas of proliferation admixed with proliferated pneumocytes, macrophages, lymphocytes, plasma cells, neutrophils, fibroblasts, and collagen (Figure 2, B and C). The degree of organization was more intense after a longer duration of disease. Extensive corpora amylacea were found in 4 patients (Figure 2, C). Multiple thrombi were present in small to mid-sized pulmonary arteries, and the vessel wall was partially infiltrated by neutrophils (Figure 3, A and B). In 8 patients, the adjacent lung tissue showed hemorrhage and infarction (Figure 3, C). In 1 of these patients, who was cared for in the intensive care unit, the infarction showed recognizable demarcation on gross examination. Because the thrombotic material filled out the lumen of the affected pulmonary arteries (Figure 1, A and B), it was considered thrombotic rather than embolic. Some of the thrombi were neither fixed to the arterial wall nor histologically organized by macrophages or granulation tissue and, therefore, were no older than a few hours. Others showed reactive neutrophil infiltrates (Figure 3, A and B). Thrombi in small arteries were also found close to or within areas of organization (Figure 3, D). In 1 patient with multiple infarctions, we could not exclude the possibility that the thrombus observed in a branch of the right pulmonary artery was embolic. We excluded a putative embolic source from the pelvic and large femoral veins but did not dissect the veins of the lower leg. Bronchopneumonia associated with infarction was found in 6 patients, ranging from focal to confluent (Figure 3, C).

Figure 2.

Stages of diffuse alveolar damage. A.

Early, with edema and hyaline membranes (original magnification, × 100). B. Intermediate, with proliferation of pneumocytes admixed with lymphocytes and neutrophils, organizing a residual hyaline membrane (original magnification, × 100). C. Late, with proliferation of fibroblasts (original magnification, × 200). Hematoxylin–eosin staining.

Figure 3.

Thrombosis of pulmonary arteries of various size. A.

Thrombosis of a dilated mid-sized pulmonary artery without subsequent infarction. The surrounding lung tissue is in part edematous (original magnification, × 10). B. A small pulmonary artery is obliterated by a thrombus, which is infiltrated by neutrophils (original magnification, × 100). C. Pulmonary artery with thrombosis and infarction and pneumonia of the surrounding lung tissue (original magnification, × 10; corresponding histology to Figure 1, B). D. Microthrombi of small arteries in areas of diffuse alveolar damage (original magnification, × 100). Hematoxylin–eosin staining.

Heart

The weight of the heart ranged from 280 g to 690 g (mean, 483 g; normal weight, 250 to 350 g). All patients had hypertrophy of both ventricles, with predominance of left ventricular hypertrophy, showing a wall thickness measured 1 cm beneath the mitral valve ranging from 14 to 22 mm. The myocardial hypertrophy was reflected histologically by enlargement of myocytes with nuclear polymorphism. In 10 patients, both ventricles were massively dilated. Patchy myocardial fibrosis of various extent in 10 patients. In 1 patient, intraventricular endocardial mural thrombi were found, but without ischemic changes of the adjacent myocardium. Neither acute myocardial necrosis nor inflammatory changes were found, except in 1 patient with a focus of fragmented cardiomyocytes with lymphocytic and granulocytic reaction. Isolated massive cardiac amyloidosis was incidentally found in a 91-year-old man and was confirmed by positive Congo red stain and immunoreactivity for amyloid P.

Peritoneal Cavity

The peritoneal cavity was inconspicuous and free of ascites in all patients. The small and large bowel and the gallbladder were also histologically normal. Focal pancreatitis was found in 4 patients, with necrosis of pancreatic parenchyma and adjacent adipose tissue and calcifications.

Liver

Steatosis was found in all patients, involving 5% to 60% of the hepatocytes, predominantly macrovesicular; in 1 patient, it was microvesicular and predominantly located pericentrally but also periportal. Chronic congestion was detected in 8 patients (73%). Hepatocyte necrosis was massive confluent and panlobular in 1 patient, focal in 2 patients (and associated with central vein thrombosis in 1 patient [Figure 4, A]), and in single cells in 4 patients with a predominant pericentral location. Kupffer cells were activated in all patients and showed nodular proliferation in 70%. Cholestasis with canalicular bile plugs was found in 7 patients. Portal changes were present in 9 patients and included a mild to moderate lymphocytic infiltrate, mild nuclear pleomorphism of cholangiocytes, and ductular proliferation with portal or incomplete septal fibrosis.

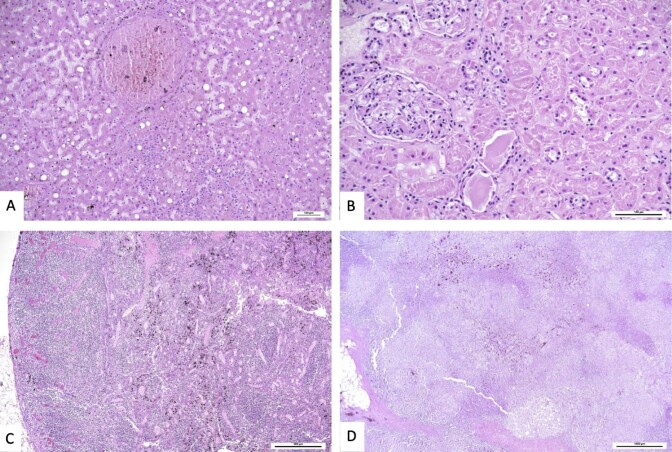

Figure 4.

Other involved organs. A.

Thrombosis of a central vein with focal necrosis of liver cells at 6 hours. Macrovesicular steatosis and focal canalicular bile plugs (original magnification, × 100). B. Acute tubular injury showing necrosis and regeneration of the proximal tubules. Some tubules contain proteinaceous material (original magnification, × 200). C. Lymphocyte depletion of a hilar lymph node, with absence of germinal centers and dilated vessels and sinuses (original magnification, × 40). D. The same patient showed adrenocortical hyperplasia with a nodular pattern (original magnification, × 20). Hematoxylin–eosin staining.

Kidneys

The most frequent findings were alterations of the proximal tubules ranging from swelling of the tubular epithelium to necrosis and regenerating changes with flattened tubular epithelium (Figure 4, B). Focally, the tubules were filled with proteinaceous masses. Benign nephrosclerosis was found in all patients and nodular glomerulosclerosis (Kimmelstiel–Wilson syndrome) in 4 patients, of whom 3 had type 2 diabetes mellitus.

Other Organs

The hilar and posterior mediastinal lymph nodes were enlarged and anthracotic in all cases, but histologically, they showed lymphocyte depletion with complete absence of germinal centers (Figure 4, C). This was associated with dilation of sinuses and vessels and partially with bleeding. The spleen showed white pulp atrophy due to lymphocyte depletion in 10 patients. In addition, areas of hemorrhage with acute or chronic congestion were noted, the latter with fibrosis. The submandibular glands showed a mild to moderate degree of lipomatosis. The thyroid was normal in 8 patients; 3 had nodular goiter. The adrenal cortex, in particular the zona fasciculata, was hyperplastic in 6 patients (86%), of whom 2 showed a slightly nodular pattern (Figure 4, D). The bone marrow showed normal hemopoiesis, with a reactive lymphocytic infiltrate in 1 patient. The brain was analyzed in 1 patient only and showed atrophy and arteriosclerotic changes but no acute alterations.

Microbiological Findings

Results of PCR are shown in Appendix Table 2 (available at Annals.org). Testing detected SARS-CoV-2 RNA on the pharyngeal swabs from 10 patients and on the bronchial system swabs from all patients. In addition, SARS-CoV-2 RNA was found in 1 patient on a swab from the colon mucosa; on 2 other swabs from the colon, the assay was inconclusive owing to assay interference by inhibitors. No SARS-CoV-2 RNA was found in bile obtained from the gallbladder in 4 patients.

Appendix Table 2. Postmortem Microbiology: Results of Polymerase Chain Reaction Assay for SARS-CoV-2.

Discussion

Autopsy rapidly regains its importance when novel diseases arise, but access may by limited during a pandemic (20). In this study, we performed autopsies on 11 of 48 deceased patients with COVID-19, 10 of whom were randomly selected over 5 weeks, and we systematically analyzed the pathologic findings in correlation with the clinical features. The pathologic findings showed a peculiar pattern of distribution, which predominantly affected the lungs but also involved the kidneys, the liver, and the lymphatic system.

Human cells are infected by SARS-CoV-2 through angiotensin-converting enzyme-2 (ACE-2) receptors, which are localized in such cell types as alveolar epithelium, renal tubular epithelium, hepatocytes, biliary epithelium, and enterocytes (25–27). A similar mechanism was proposed for SARS-1, which could be detected particularly in lungs, kidneys, and the gastrointestinal tract (28). Of note, the pattern of pathologic changes found in our study includes profound acute changes in lung and kidney but not in the gastrointestinal tract and the heart, which is similar to the findings of SARS-1 studies. Moreover, it is important to distinguish acute pathologic changes (attributed to COVID-19) from chronic underlying changes (potentially predisposing to a fatal course of COVID-19) and nonspecific secondary changes related to hypotension or sepsis.

A major acute pathologic finding was bilateral diffuse alveolar damage (DAD), characterized by alveolar edema, hyaline membranes, and proliferation of pneumocytes and fibroblasts in a heterogeneous distribution. This pattern of reaction of the alveolar system can be caused by various pathogenic agents, such as hypoxia; toxic inhalants; drugs; and infection, including with such viruses as SARS-1 (29). Early changes of DAD were recently reported for COVID-19 (16, 17). Notably, the most striking and unexpected finding was the obstruction of pulmonary arteries by thrombotic material present at both the macroscopic and microscopic level in all cases. In most of the cases, this key finding was associated with lung parenchymal bleeding and hemorrhagic infarction. Pulmonary infarction was complicated by bronchopneumonia in almost one half of the cases, although it was mostly focal. It is very likely that emphysema, which was found in all patients to some degree, may have aggravated the course of COVID-19. Of note, the combination of both alveolar and vascular changes could explain the rapid and sometimes unpredictable clinical deterioration seen in some severe COVID-19 cases (14).

The key finding of thrombosis in small to mid-sized pulmonary arteries was unexpected. On the basis of the occurrence of this finding in all patients, we assume that these thrombotic events were disease-related and were the immediate cause of death, through acute pulmonary hypertension and cessation of pulmonary circulation. Notably, pulmonary thrombosis and thromboembolisms have been reported from autopsies of patients with SARS-1 (29), but until now, not of patients with COVID-19 (15, 19). A recent autopsy study by Wichmann and colleagues (30) reported a high incidence of venous thrombosis and found pulmonary embolism as the cause of death in one third of the cases. However, we consider our findings to be caused by thrombosis rather than by thromboembolism, because most vessels were completely occluded by thrombotic material and small arteries were involved, with a diameter less than 1 mm. Our observation became apparent only by careful and systematic dissection of the formalin-fixed lungs and subsequent histologic examination of numerous samples, which might not have been performed by other researchers. Notably, pulmonary microthrombosis was observed in all cases in Wichmann and colleagues' study (30).

However, the mechanisms leading to pulmonary arterial thrombosis and coagulopathy in COVID-19 are not yet completely understood. There appears to be a causal relationship with the inflammatory and reparative processes involving DAD, because thrombi are frequently detected in small pulmonary arteries, most likely secondary to endothelial damage (31). The endothelial damage could also be related to direct viral infection of the endothelial cells, which express ACE-2 receptors, or to a host response, as recently proposed (32). Furthermore, the alveolar fibrin deposition in DAD may affect the delicate local balance of fibrinolysis and coagulation (33). A combination of alveolar and endothelial damage of smaller vessels may be followed by microvascular pulmonary thrombosis, which could then extend to larger vessels. Microthrombi in small pulmonary arterioles have been reported in recent COVID-19 cases, but large-vessel involvement has so far been only reported in rare cases diagnosed radiologically by using CT angiography (13, 34, 35). Elevated D-dimer levels greater than 2500 µg/L were determined to detect all patients with pulmonary embolism and might be a valuable selection criterion for CT angiography to detect thrombosis of segmental or subsegmental pulmonary arteries, leading to efficient treatment (36). Recently, “MicroCLOTS” (microvascular COVID-19 lung vessels obstructive thromboinflammatory syndrome) was proposed as a new name for severe pulmonary COVID-19, but this term does not acknowledge the clinically important feature of mid-sized and larger pulmonary vessel involvement revealed by our study, with all hemodynamic and respiratory consequences (37).

Patients with severe COVID-19 can develop COVID-19–associated coagulopathy (CAC), with features of both disseminated intravascular coagulation and thrombotic microangiopathy, resulting in widespread microvascular thrombosis that may involve the liver (as in 1 of our patients) and consumption of coagulation factors (38). Moreover, antiphospholipid antibodies (not tested in our patients) may also contribute to CAC (39). Recent data suggest that abnormal coagulation variables are associated with poor prognosis in patients with COVID-19 pneumonia, whereas anticoagulant treatment is associated with decreased mortality (40, 41). Notably, our patients experienced thrombosis despite prophylactic anticoagulant treatment.

Chronic organ changes of the kidneys and the liver may have contributed to fatal outcomes. These were related to preexisting arteriosclerosis and arterial hypertension and included benign nephrosclerosis; diabetes mellitus type 2; and metabolic disorders, such as nodular glomerulosclerosis and hepatic steatosis with and without fibrosis and ductular proliferation. In contrast to previous reports, severe obesity was not characteristic in our cohort (42). Acute renal tubular injury, which was also reported with SARS-1, seems to be related to hypoxia and causal for terminal renal failure rather than viral induced through the high expression of ACE-2 receptors in the epithelium of the tubules (25, 28). Acute hepatocyte necrosis as well as cholestasis should be more likely attributed to hypoxia or sepsis, also caused by central vein thrombosis and systemic inflammation rather than to a direct viral effect (43). As in the systemic inflammatory response syndrome and sepsis, liver involvement (frequently seen in our patients) could have an independent prognostic role by altering the secretion of acute phase reactant, cytokines or other inflammatory mediators, and coagulation factors and could subsequently contribute to thrombosis of subsegmental and segmental pulmonary arteries (44, 45).

The intestine was not altered in our patients, although we detected viral RNA in a swab from normal colonic mucosa. Focal pancreatic involvement appeared without clinical symptoms in about one third of our cases. The frequent depletion of lymphocytes in lymph nodes and spleen as reported in SARS-1 concurs with lymphopenia and may be similar to that in SARS-1, caused by at least in part by increased endogenous secretion of cortisol through the hypothalamic–pituitary–adrenal axis, associated with hyperplasia of the adrenal cortex (29, 46).

In conclusion, the lungs can be considered the major target organ of severe COVID-19, reacting with DAD and affected by thrombosis in subsegmental and segmental pulmonary arteries. The combination of both of these phenomena could explain the rapid clinical deterioration in severe COVID-19 and may call for more proactive expansion of current anticoagulation strategies that also consider therapeutic doses or even thrombolytic therapy (47–49). Subsequently, these severe pulmonary changes seem to lead to multiorgan failure involving especially the kidneys and, less frequently, the liver. Strict thrombosis prophylaxis, close laboratory and imaging studies, and early anticoagulant therapy for suspected cases of pulmonary arterial thrombosis or venous thromboembolism should be considered. Further studies are needed to confirm these findings and to unravel the detailed mechanisms involved in this broad spectrum of organ damage caused by SARS-CoV-2.

Biography

Acknowledgment: The authors thank Mr. Helmut Adler for his diligent autopsy assistance and Mrs. Stephanie Rinner and her biomedical analyst team for their skilled laboratory work. Above all, they dedicate this study to all fellow physicians and nurses fighting for the lives of their patients with COVID-19.

Disclosures: Dr. Lax reports personal fees from Roche, AstraZeneca, Novartis, and Biogena outside the submitted work. Dr. Koelblinger reports personal fees from CSL Behring and Eumedics outside the submitted work. Dr. Trauner reports personal fees from BiomX, Boehringer Ingelheim, Genfit, Novartis, and Regulus; grants, personal fees, and other from Falk; grants, personal fees, and other from Gilead and Intercept; other from AbbVie and Shire; and grants from Cymabay and Takeda outside the submitted work. Authors not named here have disclosed no conflicts of interest. Disclosures can also be viewed at www.acponline.org/authors/icmje/ConflictOfInterestForms.do?msNum=M20-2566.

Editors' Disclosures: Christine Laine, MD, MPH, Editor in Chief, reports that her spouse has stock options/holdings with Targeted Diagnostics and Therapeutics. Darren B. Taichman, MD, PhD, Executive Editor, reports that he has no financial relationships or interests to disclose. Cynthia D. Mulrow, MD, MSc, Senior Deputy Editor, reports that she has no relationships or interests to disclose. Eliseo Guallar, MD, MPH, DrPH, Deputy Editor, Statistics, reports that he has no financial relationships or interests to disclose. Jaya K. Rao, MD, MHS, Deputy Editor, reports that she has stock holdings/options in Eli Lilly and Pfizer. Christina C. Wee, MD, MPH, Deputy Editor, reports employment with Beth Israel Deaconess Medical Center. Sankey V. Williams, MD, Deputy Editor, reports that he has no financial relationships or interests to disclose. Yu-Xiao Yang, MD, MSCE, Deputy Editor, reports that he has no financial relationships or interest to disclose.

Reproducible Research Statement: Study protocol and statistical code: Not available. Data set: Available from Dr. Lax (e-mail, sigurd.lax@kages.at or sigurd.lax@jku.at) on reasonable request.

Corresponding Author: Sigurd F. Lax, MD, PhD, Department of Pathology, Hospital Graz II, Goestingerstrasse 22, AT-8020 Graz, and Institute of Pathology and Molecular Pathology, Johannes Kepler University, Huemerstrasse 3-5, AT-4020 Linz, Austria; e-mail, sigurd.lax@kages.at or sigurd.lax@jku.at.

Current Author Addresses: Drs. Lax, Skok, and Bargfrieder: Department of Pathology, Hospital Graz II, Goestingerstrasse 22, AT-8020 Graz, Austria.

Drs. Zechner and Kaufmann: Department of Internal Medicine, Hospital Graz II, Academic Teaching Hospital of the Medical University of Graz, Goestingerstrasse 22, AT-8020 Graz, Austria.

Dr. Kessler: Diagnostic & Research Institute of Hygiene, Microbiology and Environmental Medicine, Medical University of Graz, Neue Stiftingtalstrasse 6, AT-8010 Graz, Austria.

Dr. Koelblinger: Department of Anesthesiology, Hospital Graz II, Academic Teaching Hospital of the Medical University of Graz, Goestingerstrasse 22, AT-8020 Graz, Austria.

Dr. Vander: Institute of Hospital Hygiene and Microbiology, Styrian Hospital Corporation, Stiftingtalstrasse 14, AT-8010 Graz, Austria.

Dr. Trauner: Division of Gastroenterology and Hepatology with Intensive Care 13H1, Department of Internal Medicine III, Vienna General Hospital, Medical University of Vienna, Waehringerguertel 18-20, AT-1090 Vienna, Austria.

Author Contributions: Conception and design: S.F. Lax, K. Skok, M. Trauner.

Analysis and interpretation of the data: S.F. Lax, K. Skok, P.M. Zechner, H.H. Kessler, N. Kaufmann, C. Koelblinger, K. Vander, U. Bargfrieder, M. Trauner.

Drafting of the article: S.F. Lax, K. Skok, M. Trauner.

Critical revision for important intellectual content: S.F. Lax, P.M. Zechner, M. Trauner.

Final approval of the article: S.F. Lax, K. Skok, P.M. Zechner, H.H. Kessler, N. Kaufmann, C. Koelblinger, K. Vander, U. Bargfrieder, M. Trauner.

Provision of study materials or patients: S.F. Lax, K. Vander.

Administrative, technical, or logistic support: S.F. Lax, K. Skok, P.M. Zechner, H.H. Kessler.

Collection and assembly of data: S.F. Lax, K. Skok, P.M. Zechner, N. Kaufmann, C. Koelblinger, U. Bargfrieder, M. Trauner.

Footnotes

This article was published at Annals.org on 14 May 2020.

References

- 1. doi: 10.7326/M20-1715. Cunningham CO, Diaz C, Slawek DE. COVID-19: the worst days of our careers. Ann Intern Med. 2020. [PMID: 32282870] doi:10.7326/M20-1715. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 2. doi: 10.1038/s41586-020-2012-7. Zhou P, Yang XL, Wang XG, et al. A pneumonia outbreak associated with a new coronavirus of probable bat origin. Nature. 2020;579:270-273. [PMID: 32015507] doi:10.1038/s41586-020-2012-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 3. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa2001017. Zhu N, Zhang D, Wang W, et al; China Novel Coronavirus Investigating and Research Team. A novel coronavirus from patients with pneumonia in China, 2019. N Engl J Med. 2020;382:727-733. [PMID: 31978945] doi:10.1056/NEJMoa2001017. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 4. doi: 10.1136/gutjnl-2020-320926. Jin X, Lian JS, Hu JH, et al. Epidemiological, clinical and virological characteristics of 74 cases of coronavirus-infected disease 2019 (COVID-19) with gastrointestinal symptoms. Gut. 2020;69:1002-1009. [PMID: 32213556] doi:10.1136/gutjnl-2020-320926. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 5. doi: 10.1136/gutjnl-2020-321013. Lin L, Jiang X, Zhang Z, et al. Gastrointestinal symptoms of 95 cases with SARS-CoV-2 infection. Gut. 2020;69:997-1001. [PMID: 32241899] doi:10.1136/gutjnl-2020-321013. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 6. doi: 10.1001/jamaneurol.2020.1127. Mao L, Jin H, Wang M, et al. Neurologic manifestations of hospitalized patients with coronavirus disease 2019 in Wuhan, China. JAMA Neurol. 2020. [PMID: 32275288] doi:10.1001/jamaneurol.2020.1127. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 7. doi: 10.1111/liv.14455. Zhang Y, Zheng L, Liu L, et al. Liver impairment in COVID-19 patients: a retrospective analysis of 115 cases from a single centre in Wuhan city, China. Liver Int. 2020. [PMID: 32239796] doi:10.1111/liv.14455. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 8. doi: 10.1056/NEJMc2001737. Zou L, Ruan F, Huang M, et al. SARS-CoV-2 viral load in upper respiratory specimens of infected patients [Letter]. N Engl J Med. 2020;382:1177-1179. [PMID: 32074444] doi:10.1056/NEJMc2001737. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 9. doi: 10.7326/M20-1738. Matheny Antommaria AH, Gibb TS, McGuire AL, et al; for a Task Force of the Association of Bioethics Program Directors. Ventilator triage policies during the COVID-19 pandemic at U.S. hospitals associated with members of the Association of Bioethics Program Directors. Ann Intern Med. 2020. [PMID: 32330224] doi:10.7326/M20-1738. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 10. doi: 10.1001/jamainternmed.2020.0994. Wu C, Chen X, Cai Y, et al. Risk factors associated with acute respiratory distress syndrome and death in patients with coronavirus disease 2019 pneumonia in Wuhan, China. JAMA Intern Med. 2020. [PMID: 32167524] doi:10.1001/jamainternmed.2020.0994. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 11. doi: 10.1016/S2213-2600(20)30161-2. Phua J, Weng L, Ling L, et al; Asian Critical Care Clinical Trials Group. Intensive care management of coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19): challenges and recommendations. Lancet Respir Med. 2020;8:506-517. [PMID: 32272080] doi:10.1016/S2213-2600(20)30161-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 12. doi: 10.7326/M20-1239. Wolf MS, Serper M, Opsasnick L, et al. Awareness, attitudes, and actions related to COVID-19 among adults with chronic conditions at the onset of the U.S. outbreak: a cross-sectional survey. Ann Intern Med. 2020. [PMID: 32271861] doi:10.7326/M20-1239. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 13. doi: 10.1148/ryct.2020200067. Xie Y, Wang X, Yang P, et al. COVID-19 complicated by acute pulmonary embolism. Radiol Cardiothorac Imaging. 2020. doi:10.1148/ryct.2020200067. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 14. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(20)30566-3. Zhou F, Yu T, Du R, et al. Clinical course and risk factors for mortality of adult inpatients with COVID-19 in Wuhan, China: a retrospective cohort study. Lancet. 2020;395:1054-1062. [PMID: 32171076] doi:10.1016/S0140-6736(20)30566-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 15. doi: 10.1093/ajcp/aqaa062. Barton LM, Duval EJ, Stroberg E, et al. COVID-19 autopsies, Oklahoma, USA. Am J Clin Pathol. 2020;153:725-733. [PMID: 32275742] doi:10.1093/ajcp/aqaa062. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 16. doi: 10.1016/j.jtho.2020.02.010. Tian S, Hu W, Niu L, et al. Pulmonary pathology of early-phase 2019 novel coronavirus (COVID-19) pneumonia in two patients with lung cancer. J Thorac Oncol. 2020;15:700-704. [PMID: 32114094] doi:10.1016/j.jtho.2020.02.010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 17. doi: 10.1016/S2213-2600(20)30076-X. Xu Z, Shi L, Wang Y, et al. Pathological findings of COVID-19 associated with acute respiratory distress syndrome. Lancet Respir Med. 2020;8:420-422. [PMID: 32085846] doi:10.1016/S2213-2600(20)30076-X. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 18. doi: 10.7326/M20-0533. Zhang H, Zhou P, Wei Y, et al. Histopathologic changes and SARS-CoV-2 immunostaining in the lung of a patient with COVID-19 [Letter]. Ann Intern Med. 2020;172:629-632. [PMID: 32163542] doi:10.7326/M20-0533. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 19. doi: 10.1038/s41379-020-0536-x. Tian S, Xiong Y, Liu H, et al. Pathological study of the 2019 novel coronavirus disease (COVID-19) through postmortem core biopsies. Mod Pathol. 2020. [PMID: 32291399] doi:10.1038/s41379-020-0536-x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 20. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(03)13413-7. Nicholls JM, Poon LL, Lee KC, et al. Lung pathology of fatal severe acute respiratory syndrome. Lancet. 2003;361:1773-8. [PMID: 12781536] [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 21. doi: 10.1001/jama.2020.6019. Sanders JM, Monogue ML, Jodlowski TZ, et al. Pharmacologic treatments for coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19): a review. JAMA. 2020. [PMID: 32282022] doi:10.1001/jama.2020.6019. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 22. doi: 10.2807/1560-7917.ES.2020.25.9.2000152. Pfefferle S, Reucher S, Nörz D, et al. Evaluation of a quantitative RT-PCR assay for the detection of the emerging coronavirus SARS-CoV-2 using a high throughput system. Euro Surveill. 2020;25. [PMID: 32156329] doi:10.2807/1560-7917.ES.2020.25.9.2000152. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 23. doi: 10.1128/JCM.00599-20. Poljak M, Korva M, Knap Gašper N, et al. Clinical evaluation of the cobas SARS-CoV-2 test and a diagnostic platform switch during 48 hours in the midst of the COVID-19 pandemic. J Clin Microbiol. 2020. [PMID: 32277022] doi:10.1128/JCM.00599-20. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 24. doi: 10.5152/dir.2013.149. Sverzellati N, Kuhnigk JM, Furia S, et al. CT-based weight assessment of lung lobes: comparison with ex vivo measurements. Diagn Interv Radiol. 2013;19:355-9. [PMID: 23748036] doi:10.5152/dir.2013.149. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 25. doi: 10.1016/s0014-5793(02)03640-2. Harmer D, Gilbert M, Borman R, et al. Quantitative mRNA expression profiling of ACE 2, a novel homologue of angiotensin converting enzyme. FEBS Lett. 2002;532:107-10. [PMID: 12459472] [DOI] [PubMed]

- 26. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2020.02.052. Hoffmann M, Kleine-Weber H, Schroeder S, et al. SARS-CoV-2 cell entry depends on ACE2 and TMPRSS2 and is blocked by a clinically proven protease inhibitor. Cell. 2020;181:271-280.e8. [PMID: 32142651] doi:10.1016/j.cell.2020.02.052. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 27. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(20)30251-8. Lu R, Zhao X, Li J, et al. Genomic characterisation and epidemiology of 2019 novel coronavirus: implications for virus origins and receptor binding. Lancet. 2020;395:565-574. [PMID: 32007145] doi:10.1016/S0140-6736(20)30251-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 28. doi: 10.1002/path.1560. Ding Y, He L, Zhang Q, et al. Organ distribution of severe acute respiratory syndrome (SARS) associated coronavirus (SARS-CoV) in SARS patients: implications for pathogenesis and virus transmission pathways. J Pathol. 2004;203:622-30. [PMID: 15141376] [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 29. doi: 10.5858/2004-128-195-AODDTS. Chong PY, Chui P, Ling AE, et al. Analysis of deaths during the severe acute respiratory syndrome (SARS) epidemic in Singapore: challenges in determining a SARS diagnosis. Arch Pathol Lab Med. 2004;128:195-204. [PMID: 14736283] [DOI] [PubMed]

- 30. doi: 10.7326/M20-2003. Wichmann D, Sperhake JP, Lütgehetmann M, et al. Autopsy findings and venous thromboembolism in patients with COVID-19: a prospective cohort study. Ann Intern Med. 2020. [PMID: 32374815] doi:10.7326/M20-2003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 31. Tomashefski JF Jr, Davies P, Boggis C, et al. The pulmonary vascular lesions of the adult respiratory distress syndrome. Am J Pathol. 1983;112:112-26. [PMID: 6859225] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 32. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(20)30937-5. Varga Z, Flammer AJ, Steiger P, et al. Endothelial cell infection and endotheliitis in COVID-19 [Letter]. Lancet. 2020;395:1417-1418. [PMID: 32325026] doi:10.1016/S0140-6736(20)30937-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 33. doi: 10.1097/01.CCM.0000057846.21303.AB. Idell S. Coagulation, fibrinolysis, and fibrin deposition in acute lung injury. Crit Care Med. 2003;31:S213-20. [PMID: 12682443] [DOI] [PubMed]

- 34. doi: 10.1111/jth.14844. Dolhnikoff M, Duarte-Neto AN, de Almeida Monteiro RA, et al. Pathological evidence of pulmonary thrombotic phenomena in severe COVID-19 [Letter]. J Thromb Haemost. 2020. [PMID: 32294295] doi:10.1111/jth.14844. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 35. doi: 10.1148/radiol.2020201544. Grillet F, Behr J, Calame P, et al. Acute pulmonary embolism associated with COVID-19 pneumonia detected by pulmonary CT angiography. Radiology. 2020:201544. [PMID: 32324103] doi:10.1148/radiol.2020201544. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 36. doi: 10.1148/radiol.2020201561. Leonard-Lorant I, Delabranche X, Severac F, et al. Acute pulmonary embolism in COVID-19 patients on CT angiography and relationship to D-dimer levels. Radiology. 2020:201561. [PMID: 32324102] doi:10.1148/radiol.2020201561. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 37. doi: 10.51893/2020.2.pov2. Ciceri F, Beretta L, Scandroglio AM, et al. Microvascular COVID-19 lung vessels obstructive thromboinflammatory syndrome (MicroCLOTS): an atypical acute respiratory distress syndrome working hypothesis. Crit Care Resusc. 2020. [PMID: 32294809] [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 38. doi: 10.1111/jth.14810. Thachil J, Tang N, Gando S, et al. ISTH interim guidance on recognition and management of coagulopathy in COVID-19. J Thromb Haemost. 2020;18:1023-1026. [PMID: 32338827] doi:10.1111/jth.14810. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 39. doi: 10.1056/NEJMc2007575. Zhang Y, Xiao M, Zhang S, et al. Coagulopathy and antiphospholipid antibodies in patients with Covid-19 [Letter]. N Engl J Med. 2020;382:e38. [PMID: 32268022] doi:10.1056/NEJMc2007575. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 40. doi: 10.1111/jth.14817. Tang N, Bai H, Chen X, et al. Anticoagulant treatment is associated with decreased mortality in severe coronavirus disease 2019 patients with coagulopathy. J Thromb Haemost. 2020;18:1094-1099. [PMID: 32220112] doi:10.1111/jth.14817. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 41. doi: 10.1111/jth.14768. Tang N, Li D, Wang X, et al. Abnormal coagulation parameters are associated with poor prognosis in patients with novel coronavirus pneumonia. J Thromb Haemost. 2020;18:844-847. [PMID: 32073213] doi:10.1111/jth.14768. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 42. doi: 10.1002/oby.22831. Simonnet A, Chetboun M, Poissy J, et al; Lille Intensive Care COVID-19 and Obesity study group. High prevalence of obesity in severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus-2 (SARS-CoV-2) requiring invasive mechanical ventilation. Obesity (Silver Spring). 2020. [PMID: 32271993] doi:10.1002/oby.22831. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 43. doi: 10.1002/hep.30824. Horvatits T, Drolz A, Trauner M, et al. Liver injury and failure in critical illness. Hepatology. 2019;70:2204-2215. [PMID: 31215660] doi:10.1002/hep.30824. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 44. Jiang X, Coffee M, Bari A, et al. Towards an artificial intelligence framework for data-driven prediction of coronavirus clinical severity. CMC: Computers, Materials & Continua. 2020;63:537-51. doi:10.32604/cmc.2020.010691.

- 45. doi: 10.1111/liv.14470. Sun J, Aghemo A, Forner A, et al. COVID-19 and liver disease. Liver Int. 2020. [PMID: 32251539] doi:10.1111/liv.14470. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 46. doi: 10.1016/j.mehy.2008.03.019. Panesar NS. What caused lymphopenia in SARS and how reliable is the lymphokine status in glucocorticoid-treated patients? Med Hypotheses. 2008;71:298-301. [PMID: 18448259] doi:10.1016/j.mehy.2008.03.019. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 47. doi: 10.1111/jth.14860. Barrett CD, Moore HB, Yaffe MB, et al. ISTH interim guidance on recognition and management of coagulopathy in COVID-19: a comment [Letter]. J Thromb Haemost. 2020. [PMID: 32302462] doi:10.1111/jth.14860. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 48. doi: 10.1016/j.jacc.2020.04.031. Bikdeli B, Madhavan MV, Jimenez D, et al. COVID-19 and thrombotic or thromboembolic disease: implications for prevention, antithrombotic therapy, and follow-up. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2020. [PMID: 32311448] doi:10.1016/j.jacc.2020.04.031. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 49. doi: 10.1111/jth.14828. Wang J, Hajizadeh N, Moore EE, et al. Tissue plasminogen activator (tPA) treatment for COVID-19 associated acute respiratory distress syndrome (ARDS): a case series. J Thromb Haemost. 2020. [PMID: 32267998] doi:10.1111/jth.14828. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]