Abstract

CCD photometry observations were made of two Hungaria asteroids in 2013 April and May. 4765 Wasserburg was found to be a previously undiscovered binary with a primary period of 3.6231 ± 0.0005 h and a satellite orbital period of 15.97 ± 0.02. What makes this a particularly interesting find is that the asteroid is one member of an asteroid pair (Vokrouhlický and Nesvorný 2008). The suspected Hungaria binary is (12390) 1994 WB1. Data from 2013 indicate the possibility of a satellite with an orbital period of 15.94 h and a primary rotation period of 2.462 h. However, analysis of data from 2008 does not show a satellite and found a period of 15.20 h. At best, 1994 WB1 is an “asteroid of interest.”

CCD photometric observations of two Hungaria asteroids were made in 2013 April and May at the Center for Solar System Studies (CS3) located in Landers, CA. These were follow-up observations to provide additional data for spin axis modeling and to check for previously undetected satellites as part of a long-term study of these inner main-belt asteroids conducted by Warner (see Warner et al., 2009a).

Image processing and measurement as well as period analysis were done using MPO Canopus (Bdw Publishing). The period analysis is based on the FALC algorithm developed by Harris (Harris et al. 1989). Master flats and darks were applied to the science frames prior to measurements. The images were acquired almost exclusively by Stephens, who also did the initial image measurements that produced the data sets. Warner did the final analysis using the dual-period search feature of MPO Canopus. Conversion to an internal standard system with approximately ±0.05 mag zero point precision was accomplished using the Comp Star Selector in MPO Canopus and the MPOSC3 catalog provided with that software. The magnitudes in the MPOSC3 are based on the 2MASS catalog converted to the BVRcIc system using formulae developed by Warner (2007c).

In the plots presented below for the presumed primary of the binary system, the “Reduced Magnitude” is Johnson V corrected to unity distance by applying −5*log (rΔ) to the measured sky magnitudes with r and Δ being, respectively, the Sun-asteroid and Earth-asteroid distances in AU. For plots showing the lightcurve due to the proposed satellite, differential magnitudes are used, with the zero point being the average magnitude of the lightcurve for the primary. The primary body magnitudes were normalized to the phase angle given in parentheses, e.g., alpha(6.5°), using G = 0.15, unless otherwise stated. The horizontal axis is the rotation phase, ranging from −0.05 to 1.05.

4765 Wasserburg.

This Hungaria asteroid is one member of an asteroid pair (Vokrouhlický and Nesvorný 2008). The other member is (350716) 2001 XO105. For an in-depth discussion about the formation and characteristics of asteroid pairs, see Pravec and Nesvorný (2009) and Pravec et al. (2010).

Wasserburg had been observed several times before 2013, e.g., Warner (2007, 2010), Pravec et al. (2010). No satellite was reported as a result of those observations, analysis of all of which found a period of 3.625 h, in agreement with the results from our analysis. Observations made by Donald Pray and analysis by Pravec in 2013 consisted of one night in March and April and two in May, or within a few weeks prior to ours. They showed an interesting evolution of the primary lightcurve but no apparent deviations due to a satellite. Again the period was found close to 3.625 h.

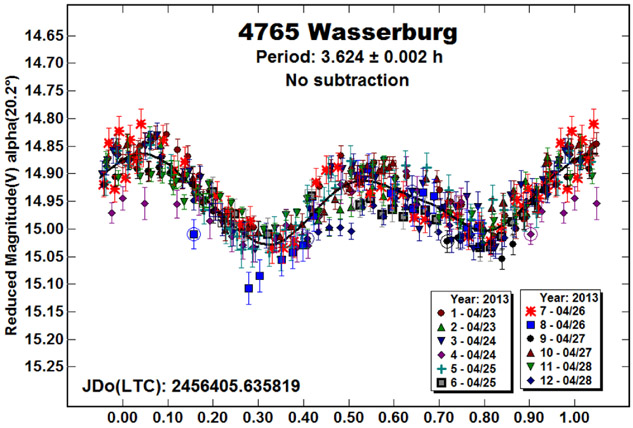

Figure 1 shows the lightcurve the asteroid using a single-period analysis from our data set obtained by Stephens using a 0.35-meter Schmidt-Cassegrain (SCT) and SBIG STEL-1001E CCD camera.. In many cases, there would be good reason to suspect that the scatter about the mean curve (solid black line) was due to systematic or random noise. However, small satellites can produce deviations on the order of only 0.02-0.03 mag, about the limit for detection using only lightcurve photometry (Pravec et al. 2006). Therefore, to be certain, a dual period analysis was done. This amounts to finding a period, such as shown in Figure 1, and then subtracting the Fourier model lightcurve from the data and doing a second search. This can lead to finding something that may resemble mutual events (occultations and/or eclipses due to a satellite) or, if the viewing geometry is not right, a continuous lightcurve showing a symmetrical “upbowing.” The latter is due to an elongated satellite that is tidally-locked to its orbital period. It’s also possible that a second period, not integrally commensurate with the primary period can be found. This would be due to a satellite that is elongated but not tidally-locked to the orbital period.

Figure 1.

The lightcurve for 4765 Wasserburg without subtracting the effects of the proposed satellite.

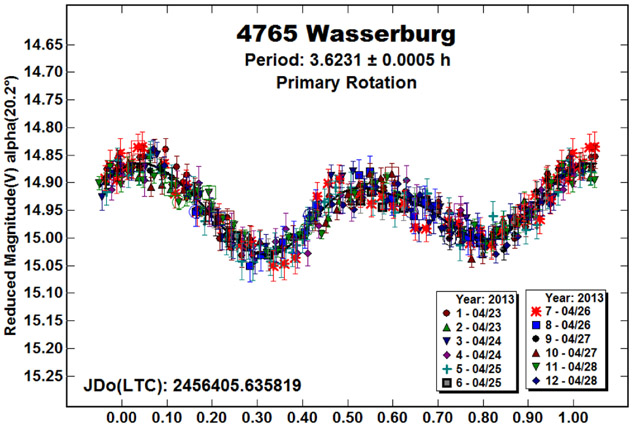

If a second period is found, an iterative process is used by subtracting period 2 to find a new period 1 and the resulting model curve used to find a new model 2 curve. The process continues until the two periods and lightcurves stabilize. Figure 2 shows the result after this iterative process for period 1, or the lightcurve due only to the rotation of the proposed primary body. The amplitude is 0.17 ± 0.01 mag and the period 3.6231 ± 0.0005 h. Note the significant improvement in the fit to the Fourier model curve.

Figure 2.

The lightcurve for 4765 Wasserburg after subtracting the effects due to the proposed satellite.

Figure 3 shows the result of subtracting the Fourier model curve for period 1 from the data set. The overall shape indicates the upbowing mentioned above but with two sharp drops separated by one-half the period. These are the result of the mutual events. Note that the depth of the drop at 0.3 rotation phase is slightly shallower than the one at 0.8. The amplitude of the shallower event can give an estimate on the size ratio of the two bodies. Since neither event is flat-bottomed, indicating a total event, then the ratio estimate is for a lower limit. Assuming the depth of the shallow event is 0.03 mag, this gives Ds/Dp ~ 0.16 ± 0.02.

Figure 3.

The lightcurve due to the proposed satellite of 4765 Wasserburg. The mutual events are seen at 0.3 and 0.8 rotation phase.

The viewing aspect for an asteroid is often given by the phase angle bisector (PAB), which is the vector that is mid-way between the asteroid-Sun and asteroid-Earth vectors. When the PAB longitude (LPAB) is nearly the same, or 180° removed, from a previous set of observations, the amplitude of an asteroid’s lightcurve will be about the same as will be the viewing geometry regarding the orbital plane of a satellite. The observations prior to 2013 fit these criteria. The amplitude of the lightcurves were about 0.57 mag. In 2013, however, the LPAB was about 90° from the line joining the previous data sets and, as might be expected, the amplitude of the lightcurve was considerably less, only 0.17 mag at the time of our observations. This may also account for why a satellite was not previously found. In 2013, LPAB was ~205°. This gives a good indication of the orientation of the spin axis, i.e., it is near 205° (or 25°).

The large amplitude of the primary in years prior to 2013 gives an a/b ratio for a triaxial ellipsoid of about 1.7. This would make this among the more elongated primaries among the small (D < 10 km) binaries.

(12390) 1994 WB1.

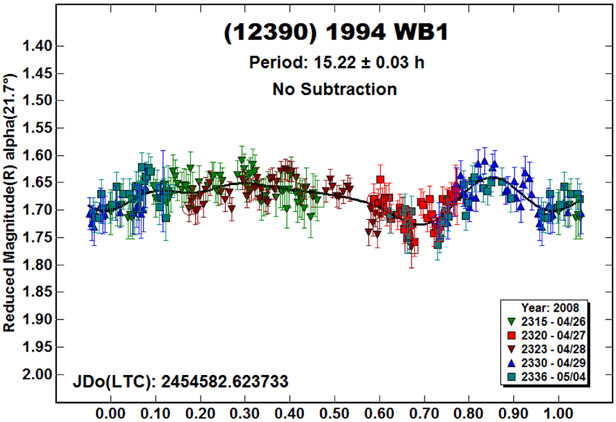

This Hungaria was observed by Warner (2008) in 2008 April. At that time, a period of 15.22 h and amplitude of 0.08 mag were reported (Figure 4). The unusual shape of the curve was noteworthy but there was no evidence of a second body.

Figure 4.

The original 2008 lightcurve for (12390) 1994 WB1.

Stephens observed 1994 WB1 on 16 nights between 2013 May 5 and June 3 using a 0.4-meter SCT and either an SBIG STL-1001E or Finger Lakes Instruments FLI-1001E CCD camera. Warner observed on June 4 using a 0.35-meter SCT and STL-1001E camera.

As more data became available, analysis found a period of 15.9 h and what appeared to be parts of mutual events due to a satellite. Being so close to a 3:2 ratio with an Earth day, observations every other night covered essentially the same part of the curve. Thus the effort to get full coverage of the lightcurve was slow.

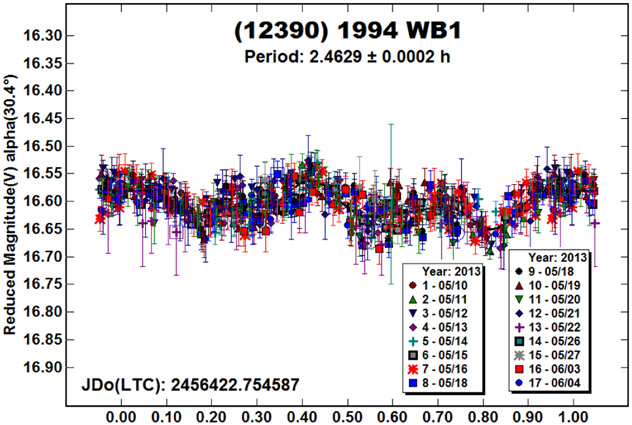

Figure 5 shows the results of our analysis using 17 data sets. The proposed primary shows an unusually-shaped curve with three apparent maximums. The period of 2.4629 ± 0.0002 h fits well with the range expected for the primary of a small binary system, as does the amplitude of 0.09 mag, which indicates the primary is approximately spheroidal. However, as seen above for 4765 Wasserburg, it’s possible, though not likely in this case because of the shape of the lightcurve, that the primary is more elongated than the amplitude implies.

Figure 5.

The lightcurve for the proposed primary of 1994 WB1.

Figure 6 shows the results of subtracting the proposed primary lightcurve from the data set. The curve is essentially flat between the apparent drops at about 0.35 and 0.85 rotation phase. It is a concern that these “events” were seen towards the beginning or ends of runs and that there is incomplete coverage. We reached out to some observers in Europe but they were not able to help for various reasons. Therefore, we could not get pass the almost exact 3:2 commensurability to fill in the missing pieces of the puzzle.

Figure 6.

The lightcurve (2013 data) for 1994 WB1 after subtracting the Fourier model for period 1.

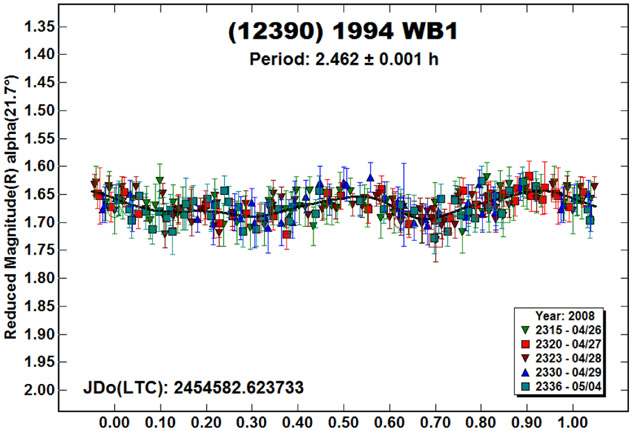

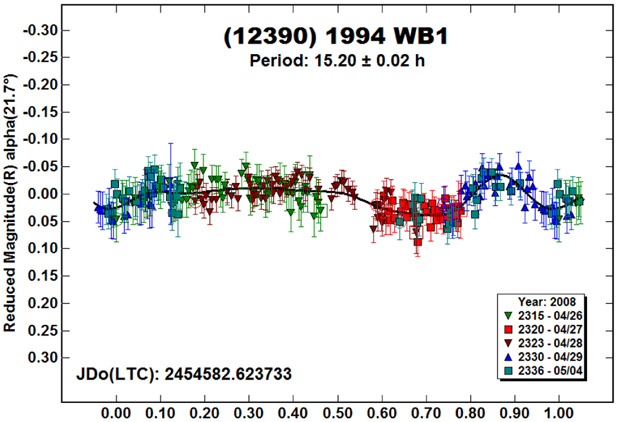

More important, the period of 15.94 h is considerably different from that obtained in 2008. Using these results, we re-analyzed the data set from 2008 to see if the older data set could be matched to the 2013 results. A period of 2.462 h could be extracted, which is in good agreement with the 2013 result (Figure 7) but it has a very low amplitude. Furthermore, when subtracting that Fourier model curve from the data, we found a period of 15.20 h for a secondary period (Figure 8) with a shape very similar to the original lightcurve. If anything the period spectrum found a “worst case solution” for a period near 15.9 h. The two data sets just could not be reconciled with one another.

Figure 7.

A proposed 2008 lightcurve for 1994 WB1.

Figure 8.

The 1994 WB1 lightcurve (2008) after subtracting P1.

Since the data sets from 2008 and 2013 do not produce the same results, and because there is good cause for doubt about the 2013 results, we cannot say with certainty that this is a binary asteroid nor make a reasonable estimate of a size ratio. For now, it must remain an “asteroid of interest” for which observations at future apparitions are strongly encouraged.

Acknowledgements

The purchase of the FLI-1001E CCD camera used by Stephens at the CS3 site was made possible by a 2013 Gene Shoemaker NEO Grant from the Planetary Society. Funding for Warner was provided by NASA grant NNX10AL35G and National Science Foundation Grant AST-1032896.

Contributor Information

Brian D. Warner, Center for Solar System Studies – Palmer Divide Station, 17995 Bakers Farm Rd., Colorado Springs, CO 80908 USA

Robert D. Stephens, Center for Solar System Studies / More Data, Rancho Cucamonga, CA USA

References

- Harris AW, Young JW, Bowell E, Martin LJ, Millis RL, Poutanen M, Scaltriti F, Zappala V, Schober HJ, Debehogne H, and Zeigler KW (1989). “Photoelectric Observations of Asteroids 3, 24, 60, 261, and 863.” Icarus 77, 171–186. [Google Scholar]

- Pravec P, Wolf M, and Sarounova L (2010, 2013). http://www.asu.cas.cz/~ppravec/neo.htm

- Pravec P and Vokrouhlický D (2009). “Significance analysis of asteroid pairs.” Icarus 204, 580–588. [Google Scholar]

- Pravec P, Vokrouhlický D, Polishook D, Scheeres DJ, Harris AW, Galád A, Vaduvescu O, Pozo F, Barr A, Longa P, Vachier F, Colas F, Pray DP, Pollock J, Reichart D, Ivarsen K, Haislip J, Lacluyze A, Kušnirák P, Henych T, Marchis F, Macomber B, Jacobson SA, Krugly Yu.N., Sergeev AV, and Leroy A (2010). “Formation of asteroid pairs by rotational fission, Nature 466, 1085–1088. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vokrouhlický D and Nesvorný D (2008). “Pairs of asteroids probably of a common origin.” Astron. J 136, 280–290. [Google Scholar]

- Warner BD (2007). “Asteroid Lightcurve Analysis at the Palmer Divide Observatory - September-December 2006.” Minor Planet Bul. 34, 72–77. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Warner BD (2008). “Asteroid Lightcurve Analysis at the Palmer Divide Observatory: February-May 2008.” Minor Planet Bul. 35, 163–167. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]