Abstract

Background

Indoleamine 2,3-dioxygenase (IDO) is a rate-limiting enzyme in the metabolism of tryptophan into kynurenine. It is considered to be an immunosuppressive molecule that plays an important role in the development of tumors. However, the association between IDO and solid tumor prognosis remains unclear. Herein, we retrieved relevant published literature and analyzed the association between IDO expression and prognosis in solid tumors.

Methods

Studies related to IDO expression and tumor prognosis were retrieved using PMC, EMbase and web of science database. Overall survival (OS), time to tumor progression (TTP) and other data in each study were extracted. Hazard ratio (HR) was used for analysis and calculation, while heterogeneity and publication bias between studies were also analyzed.

Results

A total of 31 studies were included in this meta-analysis. Overall, high expression of IDO was significantly associated with poor OS (HR 1.92, 95% CI 1.52–2.43, P < 0.001) and TTP (HR 2.25 95% CI 1.58–3.22, P < 0.001). However, there was significant heterogeneity between studies on OS (I2 = 81.1%, P < 0.001) and TTP (I2 = 54.8%, P = 0.007). Subgroup analysis showed lower heterogeneity among prospective studies, studies of the same tumor type, and studies with follow-up periods longer than 45 months.

Conclusions

The high expression of IDO was significantly associated with the poor prognosis of solid tumors, suggesting that it can be used as a biomarker for tumor prognosis and as a potential target for tumor therapy.

Keywords: Meta-analysis, IDO, Solid tumor, Survival

Background

Indoleamine 2,3-dioxygenase (IDO) is an intracellular and immunosuppressive rate-limiting enzyme in metabolism of tryptophan to kynurenine [1]. Tryptophan is an essential amino acid in protein synthesis and many important metabolic processes and cannot be synthesized in vivo. The main metabolic pathway for tryptophan in mammals is the kynurenine pathway, and this pathway requires participation of members from the IDO family. The IDO family of genes includes IDO1 and IDO2. IDO1 has higher catalytic efficiency than IDO2 and is more abundant in tissues [2]. In this systematic review and meta-analysis, the term ‘IDO’ will refer to IDO1.

IDO can exert immunosuppressive effects through a variety of mechanisms. The high expression and activity of IDO leads to a large consumption of tryptophan in the cell microenvironment, which makes the cells in a “tryptophan starvation” state. Depletion of tryptophan causes T cells arrest in the G1 phase of cell cycle, thereby inhibiting T cell proliferation. The main metabolite of tryptophan degradation, kynurenine, also has a direct toxic effect on T cells and induces T cell apoptosis. Kynurenine is also a natural ligand for aryl hydrocarbon receptors. By activating aryl hydrocarbon receptors, kynurenine can regulate the differentiation direction of Th17/Treg cells, thereby promoting the balanced differentiation of Th17/Treg to Treg cells [3–5].

IDO plays an important role in a variety of disease processes such as chronic inflammatory diseases, infection, and cancer [4, 6–8]. Increased expression of IDO is observed in many types of tumors, including colorectal, hepatocellular, ovarian and melanomas [5]. Tumors with high expression of IDO tend to increase metastatic invasion and have a poor clinical outcome in cancer patients. IDO is considered to be a new target for tumor therapy, and inhibition of IDO activity by using IDO inhibitors can increase patient survival [9–11].

Although IDO-targeted tumor therapy strategies are currently being developed, the association between expression level of IDO in tumor tissues and prognosis of patients remains unclear. Therefore, we constructed this meta-analysis to explore the correlation between IDO expression and tumor prognosis.

Methods

Search strategy

The present systematic review and meta-analysis was conducted and reported according to the standards of quality detailed in the Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses (PRISMA) statement [12]. Comprehensive and systematic search of published literature using the following database, such as PMC, Embase, and Web of Science (up to May 31, 2019). We used keyword such as: (“IDO” or Indoleamine 2,3-dioxygenase) AND (cancer or carcinoma or tumor or neoplasms) AND prognosis to search in the database. The retrieved information of relevant literature was downloaded and imported into the literature management software for further browsing and screening.

Inclusion criteria

Studies included in this meta-analysis needed to meet the following inclusion criteria: 1) The included literature needed to provide appropriate prognostic indicators in evaluating the expression of IDO and prognosis of solid tumors, such as overall survival (OS), progression-free survival (PFS), disease-free survival (DFS) or relapse-free survival (RFS). 2) The included literature needed to provide hazard ratios (HRs) with 95% confidence intervals (CIs). 3) The included literature needed to provide criteria for defining IDO expression as positive and negative, or strong and weak expression.

Exclusion criteria

This meta-analysis had the following exclusion criteria: 1) The type of literature was not a research article but the following types:reviews, case reports, letters, editorials, and meeting abstracts; 2) Animal experiments or in vitro experiments rather than patient-based clinical studies; 3) HRs and 95% CI were not directly provided in the study; 4) Research was not published in English; 5) Sample size was too small, less than 50; 6) IDO expression was not detected in tumor tissues.

Data extraction

The data extraction included in the studies were independently completed by two researchers according to the same criteria, and if there was inconsistency, a group discussion was conducted. This meta-analysis used two outcome endpoints: OS (overall survival) and TTP (time to tumor progression). Since PFS, DFS and RFS are similar outcome endpoints, we in this meta-analysis used the same prognostic parameter TTP to represent them. We extracted the following information from each study: first author’s name, publication year, country, cancer type, case number, study type, IDO detection method, cut off values for IDO expression, endpoints and HR. When the study provided HR for both univariate and multivariate analyses, we preferred results from multivariate analysis. The main features for these eligible studies are summarized in Fig. 1. Quality assessment for the included studies using the Newcastle-Ottawa Scale (NOS) [13]. According to the NOS system, the quality judgment for the studies were based on three parts: selection of study groups (4 points), comparability of study groups (2points), and outcome assessment (3 points). Studies with NOS scores above 5 were considered to have higher quality.

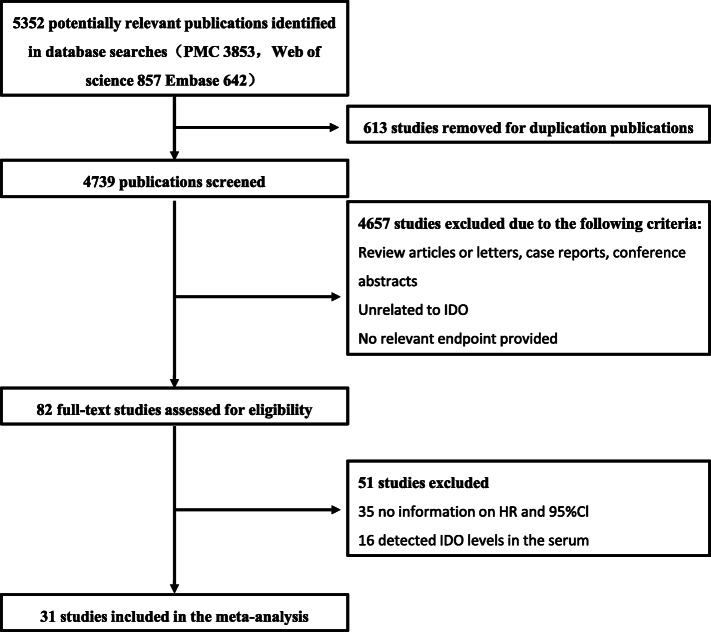

Fig. 1.

The flow chart of the selection process in our meta-analysis

Statistical analysis

Combined HR and 95% CI were used to assess the effect of IDO expression on tumor prognosis. HR > 1 and 95% CI did not overlap 1 indicating that overexpression of IDO had a negative impact on tumor prognosis. Heterogeneity analysis using the Q test, and P < 0.1 was considered statistically significant. The heterogeneity was evaluated according to I2. When I2 was 0–50%, it showed no or moderate heterogeneity, and when I2 > 50%, it showed significant heterogeneity. According to the I2 and P values, different effect models were used. When I2 > 50%, or P < 0.1, a random effects model was used. Otherwise we used a fixed effect model when the heterogeneity was low or there was no heterogeneity. Begg’s test and Egger’s test were used to determine if there was a potential publication bias in the selected studies. Sensitivity analysis was used to assesse the stability of results by excluding one study at a time. All statistical analysis and data generation were done using STATA software (StataMP 14, USA).

Results

Description of selected studies

Figure 1 shows our literature search and screening strategy. After removing 613 duplicate studies, a total of 4739 studies were further explored for the title and abstract. A total of 4657 studies were excluded due to non-conformity or irrelevant topics. 82 studies conducted further full-text evaluations, 35 of which were excluded due to lack of HR information on HR and 95% Cl, 16 studies were excluded because of detected IDO levels in the serum. Therefore, the final 31 studies included a total of 3939 patients for meta-analysis to analyze the association between IDO expression and prognosis in solid tumor patients [14–44].

The 31 studies included in this meta-analysis were derived from 10 countries, 6 studies originating from Europe (respectively from Belgium, Netherlands, Poland, Croatia and Germany), 18 from Asia (10 from China; and 8 from Japan), 2 from Africa (Tunisia), 3 from USA, 2 from Australia. All of these studies were published between 2006 and 2019. As for the cancer types, among the studies, esophageal cancer was the most common type of cancer (n = 4), followed by endometrial cancer, colorectal cancer, melanoma, and vulvar squamous cell carcinoma (n = 2). Other tumor types were involved in one study each. Since PFS, DFS and RFS are similar outcome endpoints, we used TTP to represent them in this meta-analysis. In these studies, 3 studies used polymerase chain reaction (qRT-PCR) to detect IDO expression in tumor tissues, while the other 28 studies used immunohistochemistry (IHC) staining to detect IDO expression. 28 datasets had information on OS, and 14 had information on TTP (PFS /DFS). According to NOS tool, we systematically evaluated the quality of the included studies, and all of these studies had high quality and the NOS scores were between 6 and 9 points. (Table 1).

Table 1.

Characteristics of the patients included in the meta-analysis

| Study | Year | Country | Cancer type | Case (n) | Age (Median/Mean, years) | Tumor stage (I/II/III/IV) |

Follow-up (Median/Mean, months) | Study type | Method | Cut off value | Endpoints | NOS |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Gerald. et al | 2006 | Austria | Colorectal cancer | 143 | NA | 29/24/78/12 | 51.8a | Retrospective | IHC |

High expression: score (5–12) Low expression: score (0–4) |

OS | 8 |

| K. et al | 2006 | Japan | Endometrial cancer | 80 | 57.2a | 54/10/10/6 | 71.6b | Retrospective | IHC |

High expression: score (4–6) Low expression: score (0–3) |

OS, PFS | 8 |

| Rainer. et al | 2007 | Japan | Renal cell carcinoma | 55 | NA | 22/33 | NA | Retrospective | qPCR | High expression: Above the 80th percentile | OS | 6 |

| Ke. et al | 2008 | China | Hepatocellular carcinoma | 138 | NA | NA | NA | Retrospective | IHC |

High expression: score (5–9) Low expression: score (0–4) |

OS | 8 |

| Kazuhiko. et al | 2008 | Japan | Endometrial Cancer | 65 | 57.7a | 44/6/9/6 | 72b | Retrospective | IHC |

High expression: score (4–5) Low expression: score (0–3) |

OS, PFS | 8 |

| Hiroshi. et al | 2009 | Japan | Osteosarcoma | 47 | 15b | 0/47/0/0 | 67.4b | Retrospective | IHC |

High expression: score (4) Low expression: score (0–3) |

OS | 7 |

| Tomoko. et al | 2010 | Japan | Cervical cancer | 112 | NA | 67/45/0/0 | NA | Retrospective | IHC | High expression: > 50% of tumor cells were stained | OS, PFS | 7 |

| Jacek. et al | 2011 | Poland | Vulvar squamous cell carcinoma | 76 | 69.5b | NA | 51.23b | Retrospective | IHC | > 50% of tumor cells were stained with clusters of higher intensity of expression | OS | 8 |

| Reinhart. et al | 2011 | Belgium | Melanoma | 116 | 52b | NA | 71b | Prospective | IHC | Almost none/weak versus strong IDO expression | OS, PFS | 9 |

| Renske. et al | 2012 | Netherland | Endometrial carcinoma | 355 | 64b | 196/58/77/44 | 63.6b | Prospective | IHC |

High expression: score (4–6) Low expression: score (0–3) |

DFS | 8 |

| Jin. et al | 2013 | China | Laryngeal squamous cell carcinoma | 187 | 52.4b | 20/58/88/21 | 48.56a | Retrospective | IHC |

High expression: score (3–4) Low expression: score (0–2) |

OS, DFS | 9 |

| Yunlong. et al | 2015 | China | Esophageal squamous cell cancer | 196 | 54b | 113(I–II)/83(III–IV) | NA | Prospective | IHC |

High expression: score (5–12) Low expression: score (0–4) |

OS | 8 |

| Maciej. et al | 2015 | Poland | Melanoma | 48 | 56.9b | NA | 30.3b | Retrospective | IHC | High expression: score > 47.39 Low expression: score ≤ 47.39 | OS | 6 |

| Ahlem. et al | 2016 | Tunisia | Nasopharyngeal carcinoma | 71 | NA | 10(I–II)/53(III–IV) | 30b | Prospective | IHC |

High expression: score (4–5) Low expression: score (0–3) |

OS, PFS | 7 |

| Hao. et al | 2016 | China | Gastric adenocarcinoma | 357 | 60.3a | 80/79/198/0 | 41b | Retrospective | IHC | With the X-tile software, the cut-off point was 282, 51% patients were separated into the IDO high expression subgroup | OS | 7 |

| Tao. et al | 2017 | China | Pancreatic cancer | 80 | NA | 10(I–II)/53(III–IV) | 40b | Prospective | IHC |

High expression: score (> 4) Low expression: score (≤4) |

OS | 8 |

| Tvrtko. et al | 2017 | Croatia | Bladder carcinomas | 74 | 65.3a | NA | NA | Prospective | qPCR | IDO-positive group, in which expression of IDO gene was detected, regardless of the level of expression. | OS | 7 |

| Daniel. et al | 2017 | USA | Breast cancer | 362 | NA | 278(I–II)/63(III–IV) | NA | Retrospective | IHC | Median cut-point was used to stratify IDO1 scores in low and high statuses. | OS | 8 |

| Lijie. et al | 2017 | USA | Glioblastoma | 148 | NA | NA | NA | Prospective | qPCR | IDO1 mRNA levels were stratified into IDO1- low and -high expressing groups based on the determined cutoff values. | OS | 8 |

| Wenjuan. et al | 2018 | China | Colorectal cancer | 95 | NA | NA | NA | Retrospective | IHC |

High expression: score (2–3) Low expression: score (0–1) |

OS | 7 |

| Yufeng. et al | 2018 | Taiwan (China) | Thymic carcinoma | 69 | 54a | 1/3/45/20 | 46b | Retrospective | IHC |

High expression: score (2–3) Low expression: score (0–1) |

OS, PFS | 8 |

| Hiroto. et al | 2018 | Japan | Esophageal cancer | 182 | 66.5a | 69/63/41/9 | NA | Retrospective | IHC |

High expression: score (2–3) Low expression: score (0–1) |

RFS | 7 |

| Yuki. et al | 2018 | Japan | Esophageal Cancer | 305 | 66a | 123/80/102/0 | 44.4b | Prospective | IHC | (0; no expression, 1; weak expression, 2; moderate expression or 3; strong expression) | OS | 9 |

| Masaaki. et al | 2018 | Japan | Gastric Cancer | 60 | 67.8a | 0/0/60/0 | 41a | Retrospective | IHC | A total score of greater than 4+ was defined as IDO positive expression | OS, DFS | 8 |

| Tamkin. et al | 2019 | Australia | Malignant pleural mesothelioma | 67 | 65b | NA | NA | Retrospective | IHC |

Negative Positive (> 0%) |

OS | 7 |

| Wenjuan. et al | 2019 | China | Adenosquamous Lung Carcinoma | 183 | 58b | 52/41/71/19 | NA | Retrospective | IHC | High- and low-expression based on the determined cutoff values. | OS | 8 |

| Devarati. et al | 2019 | USA | Anal cancer | 63 | 61b | 7/24/9/21 (2 unknown) | 35b | Retrospective | IHC | Positive (> 50% IDO1 expression) | OS | 8 |

| Julia. et al | 2019 | Germany | Rectal cancer | 91 | 64b | NA | NA | Retrospective | IHC |

High expression: score (3–6) Low expression: score (0–2) |

OS, DFS | 8 |

| Nadia. et al | 2019 | Tunisia | Vulvar squamous cell carcinoma | 61 | 65.61a | 29/4/26/2 | NA | Retrospective | IHC |

High expression: score (3) Low expression: score (0–2) |

OS, DFS | 7 |

| Sha. et al | 2019 | China | Esophageal squamous cell carcinoma | 158 | 56b | 0/34/124/0 | 40.2b | Retrospective | IHC | Positive (> 50% IDO1 expression) | RFS | 8 |

| Yuhshyan. et al | 2019 | Taiwan (China) | Bladder cancer | 108 | 68a | 45/43/19/1 | 45b | Retrospective | IHC | Strongly Positive (> 25% IDO1 expression) | OS, PFS | 8 |

Abbreviations: IHC Immunohistochemistry, qPCR Quantitative Real Time Polymerase Chain Reaction, NOS Newcastle-Ottawa Scale, OS overall survival, DFS disease free survival, PFS progression free survival. a Mean, b Median. NA: Not Available

Impact of IDO expression on cancer prognosis

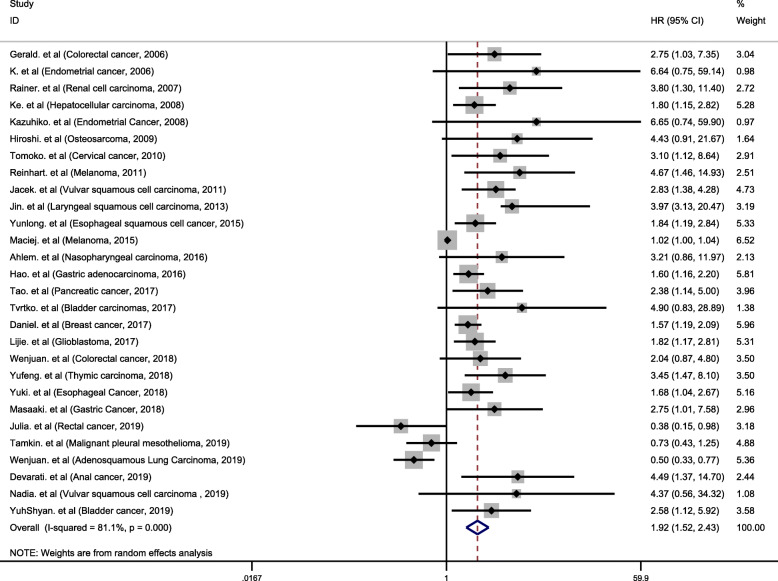

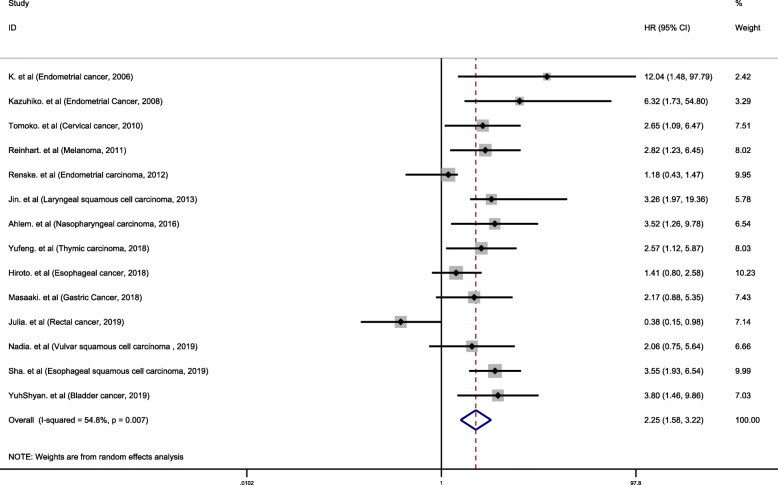

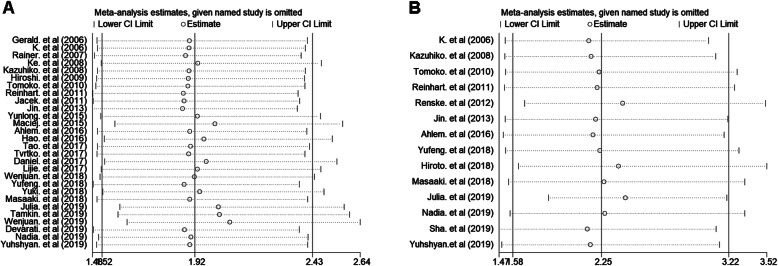

In the included studies, a total of 28 studies analyzed the association between IDO expression and OS. Of these 28 studies, 3 studies with HR < 1 [38, 39, 41], and 18 studies with HR > 2 [14–16, 18–22, 24, 27, 29, 30, 33, 34, 37, 42–44]. We performed a meta-analysis of 28 studies. Since I2 values was 81.1%, the random effects model was used to calculate the pooled HR and 95% CI. The combined analysis of 28 datasets indicated that compared with IDO negative/low expression, IDO positivity/high expression was highly correlated with poor prognosis in cancer patients (pooled HR 1.92, 95% CI 1.52–2.43, P < 0.001) (Fig. 2). A total of 14 studies were used to assess the association between IDO expression and TTP. We calculated the pooled HR using a random effects model, because the heterogeneity test indicated an I2 value of 54.8% and a P value of 0.007. The results indicated that high expression of IDO was highly correlated with poor prognosis of TTP (pooled HR = 2.25, 95% CI 1.58–3.22, P < 0.001) (Fig. 3).

Fig. 2.

Meta-analysis of impact of IDO expression on prognosis of patients with solid tumors. Forest plot of HRs for correlation between IDO expression and OS in solid tumor patients. Results are presented as individual and metaHR, and 95% CI. The random-effects model was used. The square size of individual studies represented the weight of the study. Vertical lines represent 95% CI of the pooled estimate. The diamond represents the overall summary estimate, with the 95% CI given by its width

Fig. 3.

Forest plot of HRs for correlation between IDO expression and TTP in solid tumor patients. Results are presented as individual and metaHR, and 95% CI. The random-effects model was used. The square size of individual studies represents the weight of the study. Vertical lines represent 95% CI of the pooled estimate. The diamond represents the overall summary estimate, with the 95% CI given by its width

Subgroup analysis

Since the results from the meta-analysis indicated significant heterogeneity, we performed heterogeneity analysis in order to identify potential factors that may cause heterogeneity. We classified the included studies and performed heterogeneity analysis based on study location, detection method, sample size, study type, cancer type, age, follow-up periods and study quality. Subgroup analysis showed that the high expression of IDO was highly correlated with poor OS and TTP, but the heterogeneity was not significantly reduced according to different study locations, detection method, sample size grouping, average age and study quality. However, in a prospective study group, we found that high expression of IDO was highly correlated with poor OS prognosis (HR1.98, 95% CI 1.57–2.49, P < 0.001) and there was no heterogeneity (I2 = 0%, P = 0.6) (Table 2). Subgroup analysis showed that there was no heterogeneity among bladder cancer, colorectal cancer, endometrial cancer and esophageal cancer studies. Heterogeneity was also significantly reduced among studies of the same type of tumor, such as digestive system tumors and reproductive system tumors (Table 2). In addition, there was no significant heterogeneity (HR 3.41, 95% CI 2.41–4.83, P < 0.001. I2 = 0%, P = 0.97) between studies with an average follow-up period of more than 45 months (Table 2).

Table 2.

Hazard ratio for the association between IDO overexpression and solid tumors prognosis

| Stratified analysis | Effect size | NO. of study | Cases | HR | Heterogeneity | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Pooled HR (95% CI) | P value | I2 (%) | p value | ||||

| All studies | |||||||

| OS | OS | 28 | 3457 | 1.92 (1.52–2.43) | < 0.001 | 81.1 | < 0.001 |

| TTP | TTP | 14 | 1815 | 2.25 (1.58–3.22) | < 0.001 | 54.8 | 0.007 |

| Study location | |||||||

| Asia | OS | 16 | 2137 | 2.12 (1.54–2.92) | < 0.001 | 68.5 | < 0.001 |

| TTP | 9 | 1121 | 2.48 (1.74–3.55) | < 0.001 | 11.4 | 0.342 | |

| Other countries | OS | 12 | 1320 | 1.66 (1.17–2.37) | 0.005 | 82.2 | < 0.001 |

| TTP | 5 | 694 | 1.99 (1.32–2.98) | 0.001 | 14.3 | 0.323 | |

| Detection method | |||||||

| IHC | OS | 25 | 3180 | 1.86 (1.46–2.38) | < 0.001 | 81.3 | < 0.001 |

| TTP | 14 | 1815 | 2.25 (1.58–3.22) | < 0.001 | 54.8 | 0.007 | |

| qPCR | OS | 3 | 277 | 2.11 (1.42–3.13) | < 0.001 | 17.7 | 0.297 |

| Sample size | |||||||

| < 70 | OS | 9 | 535 | 2.25 (1.31–3.88) | 0.003 | 75.5 | < 0.001 |

| TTP | 4 | 255 | 2.49 (1.51–4.10) | < 0.001 | 0.0 | 0.72 | |

| 70–120 | OS | 10 | 903 | 2.37 (1.42–3.95) | 0.001 | 55.9 | 0.02 |

| TTP | 6 | 578 | 2.43 (1.09–5.44) | 0.03 | 72.8 | 0.003 | |

| > 140 | OS | 9 | 2019 | 1.60 (1.18–2.18) | 0.003 | 75.8 | < 0.001 |

| TTP | 4 | 882 | 1.98 (1.12–3.51) | 0.019 | 63.2 | 0.043 | |

| Study type | |||||||

| Retrospective | OS | 21 | 2807 | 1.82 (1.39–2.40) | < 0.001 | 81.5 | < 0.001 |

| TTP | 11 | 1273 | 2.32 (1.50–3.60) | < 0.001 | 57.9 | 0.008 | |

| Prospective | OS | 7 | 650 | 1.98 (1.57–2.49) | < 0.001 | 0 | 0.6 |

| TTP | 3 | 542 | 2.09 (1.03–4.23) | 0.04 | 56.2 | 0.102 | |

| Cancer type | |||||||

| Digestive system tumor | OS | 10 | 1528 | 1.79 (1.38–2.31) | < 0.001 | 40.8 | 0.085 |

| Reproductive system tumor | OS | 6 | 756 | 2.39 (1.53–3.72) | < 0.001 | 34.9 | 0.175 |

| Bladder cancer | OS | 2 | 182 | 2.90 (1.32–6.15) | 0.006 | 0.0 | 0.521 |

| Colorectal cancer | OS | 2 | 238 | 2.32 (1.22–4.42) | 0.01 | 0.0 | 0.655 |

| Endometrial cancer | OS | 2 | 145 | 6.64 (1.41–31.27) | 0.017 | 0.0 | 0.99 |

| Esophageal cancer | OS | 2 | 501 | 1.76 (1.28–2.43) | 0.001 | 0.0 | 0.79 |

| Esophageal cancer | TTP | 2 | 340 | 2.23 (0.91–5.49) | 0.081 | 77.9 | 0.033 |

| Gastric Cancer | OS | 2 | 417 | 1.68 (1.22–2.32) | 0.001 | 1.5 | 0.314 |

| Melanoma | OS | 2 | 164 | 1.95 (0.45–8.49) | 0.376 | 84.8 | 0.01 |

| Vulvar squamous cell carcinoma | OS | 2 | 137 | 2.92 (1.69–5.04) | < 0.001 | 0.0 | 0.69 |

| Age (Mean/Median) | |||||||

| < 60 years | OS | 9 | 991 | 2.02 (1.22–3.36) | 0.007 | 83.6 | < 0.001 |

| > 60 years | OS | 10 | 1262 | 1.76 (1.16–2.67) | 0.008 | 68.8 | 0.001 |

| Follow-up (Median/Mean) | |||||||

| ≤ 45 months | OS | 8 | 1092 | 1.90 (1.29–2.78) | 0.001 | 79.4 | < 0.001 |

| > 45 months | OS | 8 | 783 | 3.41 (2.41–4.83) | < 0.001 | 0.0 | 0.97 |

| Study quality | |||||||

| NOS score > 7 | OS | 18 | 2825 | 2.00 (1.48–2.69) | < 0.001 | 72.6 | < 0.001 |

| NOS score ≤ 7 | OS | 10 | 632 | 1.75 (1.20–1.57) | < 0.001 | 72.4 | < 0.001 |

Abbreviations: HR hazard ratio, CI confidence interval, OS overall survival, TTP time to tumor progression, IHC Immunohistochemistry, qPCR Quantitative Real Time Polymerase Chain Reaction

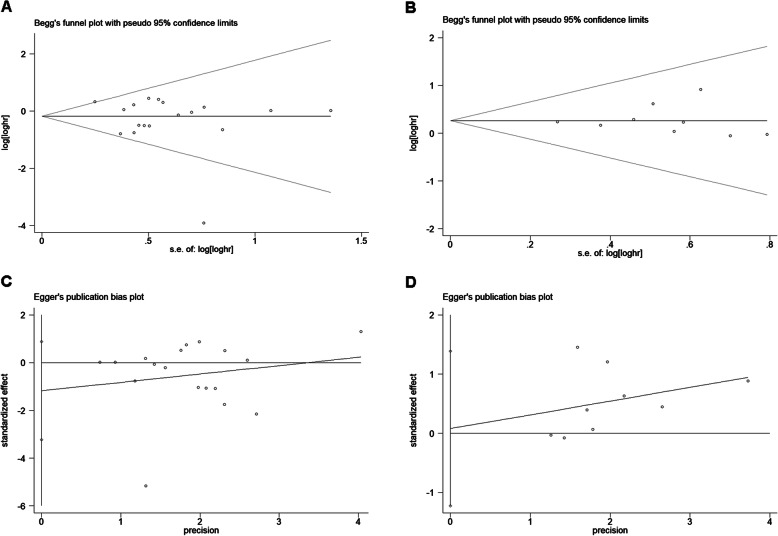

Publication bias and sensitivity analysis

Evaluation of publication bias between studies was done using Begg’s funnel plot and Egger’s test. The shape of the OS and TTP funnel plots were not significantly asymmetrical, and the Egger’s test indicated OS (P = 0.47) and TTP (P = 0.89). These results suggested that there was no significant publication bias in the meta-analysis of IDO expression in relation to OS and TTP prognosis (Fig. 4). Sensitivity analysis refers to the removal of a study each time to analyze the impact of individual studies on the stability of meta-analysis results. Sensitivity analysis showed that no single study had a significant impact on the conclusions of this meta-analysis (Fig. 5).

Fig. 4.

Begg’s funnel plots and Egger’s publication bias plots for studies involved in the meta-analysis. Begg’s funnel plots for the studies included in meta-analysis regarding. OS (a) and TTP (b). Each hazard ratio (HR) was plotted on an HR scale against its standard error (SE). The horizontal lines indicate the pooled estimate of the overall HR, with the sloping lines reflecting the expected 95% confidence interval for a given SE. Egger’s publication bias plots for the studies included in meta-analysis regarding OS (c) and TTP (d). The 95% confidence intervals of the regression line’s y intercept include zero, P values were 0.59 and 0.89, respectively, indicating that there was no evidence of publication bias

Fig. 5.

Sensitivity analysis of the meta-analysis. a Overall survival. b Time to tumor progression. The vertical axis at 1.98 and 2.25 indicates the overall HR, and the vertical lines on either side of 1.98 and 2.25 indicate the 95% CI. Every hollow round indicates the pooled HR when the left study was omitted in a meta-analysis with a random model. The two ends of every broken line represent the respective 95% CI

Discussions

In this study, we systematically assessed IDO expression level and prognostic indicators of 3939 solid tumor patients from 31 different studies. Our results showed that high expression of IDO predicted poor OS and TTP in cancer patients. However, the results from this meta-analysis indicated that there was significant heterogeneity among these studies. The Begg’s funnel plot and Egger’s test showed that there was no significant publication bias in this meta-analysis, and the sensitivity analysis showed that no single study can influence the conclusion of this meta-analysis.

High expression of IDO was highly correlated with poor prognosis of OS and TTP. However, the heterogeneity was also obvious. It was not difficult to understand that there will be heterogeneity in our study. In 31 studies, a total of 10 tumor types were included, and the role of IDO in different tumors may be inconsistent. For example, three studies have concluded to the contrary. In addition, the study type, IDO test method, number of patients included, follow-up period, and study quality were different in each study, all these factors can lead to heterogeneity. To this end, we performed a subgroup analysis to explore the source of heterogeneity. Subgroup analysis showed that the study location, sample size, and age were not sources of heterogeneity. For OS, no heterogeneity in prospective studies and follow-up period over 45 months studies. These results indicate that the type of study and follow-up period were the reasons for the heterogeneity in this meta-analysis. In addition, in the same type of tumor research (such as digestive system tumors and reproductive system tumors), there was no obvious heterogeneity. Subgroup analysis also showed no heterogeneity in bladder cancer, colorectal cancer, endometrial cancer and esophageal cancer, gastric cancer and vulvar squamous cell carcinoma studies. The difference in study quality may also be the cause of heterogeneity. To this end, we used the NOS score to evaluate the quality of each study and performed a subgroup analysis based on the NOS score. We found that the high-scoring study group did not significantly reduce heterogeneity. Therefore, in this meta-analysis, the quality of study is not the main reason for heterogeneity.

Our study further enhanced the view that high expression of IDO has a poor prognosis for cancer patients by performing meta-analysis on a large number of research data. In addition, this meta-analysis also gives hints on several other aspects. First, the high expression of IDO may be a universal prognostic biomarker for solid tumors. We analyzed 10 different types of solid tumors, including colorectal cancer, endometrial cancer, renal cell carcinoma, hepatocellular carcinoma, etc. Secondly, we verified that both Asian patients and other country patients harboring high expression of IDO were highly correlated with poor prognosis in patients with solid tumors, which did not vary because of ethnic differences. Moreover, our results suggested that the IDO expression can be used as a more widely prognostic biomarker. Finally, this study suggested that IDO had the potential to develop into a prognostic biomarker and a therapeutic target for solid tumors.

It should be noted that, there were limitations in this meta-analysis. First, the definitions of IDO positive and high expression were not completely consistent between studies, which may cause heterogeneity between studies. Secondly, due to limitations from the other included studies and large number of tumor types, we were unable to perform a subgroup analysis for each type of tumor. Thirdly, we extracted the HRs data directly from the original literature, and these data were reliable than calculated HRs indirectly deducted from the literature. However, some studies did not provide complete data and were excluded from statistics, hence some missing information might have reduced the power of IDO as a prognostic biomarker in solid tumor patients.

Conclusions

In summary, this meta-analysis clearly demonstrated that the high expression of IDO in tumor tissues was closely related to poor survival of tumor patients. Our study suggested that IDO may be used as a potential tumor prognostic biomarker and tumor treatment target.

Acknowledgements

Not applicable.

Abbreviations

- IDO

Indoleamine 2,3-dioxygenase

- OS

Overall survival

- TTP

Time to progression

- HR

Hazard ratio

- CI

Confidence interval

- Tregs

Regulatory T-cells

- 1-MT

1-methyltryptophan

- DSS

Disease-specific survival

- RFS

Relapse-free survival

- DFS

Disease-free survival

- TTR

Time to recurrence

- NOS

Newcastle-Ottawa Scale

Authors’ contributions

SW, HS and JJW conceived of the idea, designed the study, defined the search strategy and selection criteria, and were the major contributors in writing the manuscript. SW and JW performed the literature search and the analyses. All the authors contributed to the writing and editing of the manuscript. All authors read and approved the final manuscript, and ensured that this is the case.

Funding

This work is supported by the National Natural Science Foundation (81601765, 81572074) and Jiangsu Province Postdoctoral Science Foundation (1601155B), including the design of the study and collection, analysis, and interpretation of data and in writing the manuscript.

Availability of data and materials

All data generated or analyzed during this study are included in this published article. The datasets used and/or analysed during the current study available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

Ethics approval and consent to participate

This research work constitutes a meta-analysis of published data and does not include any studies with human participants or animals performed by any of the authors. Hence, no informed consent was required to perform this study.

Consent for publication

Not applicable.

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Footnotes

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Sen Wang and Jia Wu contributed equally to this work.

Contributor Information

Han Shen, Email: shenhan10366@sina.com.

Junjun Wang, Email: wangjunjun9202@163.com.

References

- 1.Munn DH, Mellor AL. Indoleamine 2,3 dioxygenase and metabolic control of immune responses. Trends Immunol. 2013;34(3):137–143. doi: 10.1016/j.it.2012.10.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Ball HJ, Yuasa HJ, Austin CJ, Weiser S, Hunt NH. Indoleamine 2,3-dioxygenase-2; a new enzyme in the kynurenine pathway. Int J Biochem Cell Biol. 2009;41(3):467–471. doi: 10.1016/j.biocel.2008.01.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Mbongue J, Nicholas D, Torrez T, Kim N, Firek A, Langridge W. The role of Indoleamine 2, 3-Dioxygenase in immune suppression and autoimmunity. Vaccines. 2015;3(3):703–729. doi: 10.3390/vaccines3030703. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Nguyen NT, Nakahama T, Le DH, Van Son L, Chu HH, Kishimoto T. Aryl hydrocarbon receptor and Kynurenine: recent advances in autoimmune disease research. Front Immunol. 2014;5:551. doi: 10.3389/fimmu.2014.00551. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Munn DH, Mellor AL. IDO in the tumor microenvironment: inflammation, counter-regulation, and tolerance. Trends Immunol. 2016;37(3):193–207. doi: 10.1016/j.it.2016.01.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Boasso A, Herbeuval JP, Hardy AW, Anderson SA, Dolan MJ, Fuchs D, Shearer GM. HIV inhibits CD4+ T-cell proliferation by inducing indoleamine 2,3-dioxygenase in plasmacytoid dendritic cells. BLOOD. 2007;109(8):3351–3359. doi: 10.1182/blood-2006-07-034785. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Mehraj V, Routy JP. Tryptophan catabolism in chronic viral infections: handling uninvited guests. Int J Tryptophan Res. 2015;8:41–48. doi: 10.4137/IJTR.S26862. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.von Bubnoff D, Bieber T. The indoleamine 2,3-dioxygenase (IDO) pathway controls allergy. ALLERGY. 2012;67(6):718–725. doi: 10.1111/j.1398-9995.2012.02830.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Platten M, von Knebel DN, Oezen I, Wick W, Ochs K. Cancer immunotherapy by targeting IDO1/TDO and their downstream effectors. Front Immunol. 2015;5:673. doi: 10.3389/fimmu.2014.00673. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Jiang T, Sun Y, Yin Z, Feng S, Sun L, Li Z. Research progress of indoleamine 2,3-dioxygenase inhibitors. Future Med Chem. 2015;7(2):185–201. doi: 10.4155/fmc.14.151. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Liu X, Newton RC, Friedman SM, Scherle PA. Indoleamine 2,3-dioxygenase, an emerging target for anti-cancer therapy. Curr Cancer Drug Targets. 2009;9(8):938–952. doi: 10.2174/156800909790192374. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Moher D, Liberati A, Tetzlaff J, Altman DG. Preferred reporting items for systematic reviews and meta-analyses: the PRISMA statement. Int J Surg. 2010;8(5):336–341. doi: 10.1016/j.ijsu.2010.02.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Stang A. Critical evaluation of the Newcastle-Ottawa scale for the assessment of the quality of nonrandomized studies in meta-analyses. Eur J Epidemiol. 2010;25(9):603–605. doi: 10.1007/s10654-010-9491-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Brandacher G. Prognostic value of Indoleamine 2,3-Dioxygenase expression in colorectal Cancer: effect on tumor-infiltrating T cells. Clin Cancer Res. 2006;12(4):1144–1151. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-05-1966. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Ino K, Yoshida N, Kajiyama H, Shibata K, Yamamoto E, Kidokoro K, Takahashi N, Terauchi M, Nawa A, Nomura S, et al. Indoleamine 2,3-dioxygenase is a novel prognostic indicator for endometrial cancer. Br J Cancer. 2006;95(11):1555–1561. doi: 10.1038/sj.bjc.6603477. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Riesenberg R, Weiler C, Spring O, Eder M, Buchner A, Popp T, Castro M, Kammerer R, Takikawa O, Hatz RA, et al. Expression of indoleamine 2,3-dioxygenase in tumor endothelial cells correlates with long-term survival of patients with renal cell carcinoma. Clin Cancer Res. 2007;13(23):6993–7002. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-07-0942. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Pan K, Wang H, Chen MS, Zhang HK, Weng DS, Zhou J, Huang W, Li JJ, Song HF, Xia JC. Expression and prognosis role of indoleamine 2,3-dioxygenase in hepatocellular carcinoma. J Cancer Res Clin Oncol. 2008;134(11):1247–1253. doi: 10.1007/s00432-008-0395-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Ino K, Yamamoto E, Shibata K, Kajiyama H, Yoshida N, Terauchi M, Nawa A, Nagasaka T, Takikawa O, Kikkawa F. Inverse correlation between tumoral indoleamine 2,3-dioxygenase expression and tumor-infiltrating lymphocytes in endometrial cancer: its association with disease progression and survival. Clin Cancer Res. 2008;14(8):2310–2317. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-07-4144. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Urakawa H, Nishida Y, Nakashima H, Shimoyama Y, Nakamura S, Ishiguro N. Prognostic value of indoleamine 2,3-dioxygenase expression in high grade osteosarcoma. CLIN EXP METASTAS. 2009;26(8):1005–1012. doi: 10.1007/s10585-009-9290-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Inaba T, Ino K, Kajiyama H, Shibata K, Yamamoto E, Kondo S, Umezu T, Nawa A, Takikawa O, Kikkawa F. Indoleamine 2,3-dioxygenase expression predicts impaired survival of invasive cervical cancer patients treated with radical hysterectomy. Gynecol Oncol. 2010;117(3):423–428. doi: 10.1016/j.ygyno.2010.02.028. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Sznurkowski JJ, Awrocki A, Emerich J, Sznurkowska K, Biernat W. Expression of indoleamine 2,3-dioxygenase predicts shorter survival in patients with vulvar squamous cell carcinoma (vSCC) not influencing on the recruitment of FOXP3-expressing regulatory T cells in cancer nests. Gynecol Oncol. 2011;122(2):307–312. doi: 10.1016/j.ygyno.2011.04.050. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Speeckaert R, Vermaelen K, van Geel N, Autier P, Lambert J, Haspeslagh M, van Gele M, Thielemans K, Neyns B, Roche N, et al. Indoleamine 2,3-dioxygenase, a new prognostic marker in sentinel lymph nodes of melanoma patients. Eur J Cancer. 2012;48(13):2004–2011. doi: 10.1016/j.ejca.2011.09.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.de Jong RA, Kema IP, Boerma A, Boezen HM, van der Want JJ, Gooden MJ, Hollema H, Nijman HW. Prognostic role of indoleamine 2,3-dioxygenase in endometrial carcinoma. Gynecol Oncol. 2012;126(3):474–480. doi: 10.1016/j.ygyno.2012.05.034. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Ye J, Liu H, Hu Y, Li P, Zhang G, Li Y. Tumoral indoleamine 2,3-dioxygenase expression predicts poor outcome in laryngeal squamous cell carcinoma. Virchows Arch. 2013;462(1):73–81. doi: 10.1007/s00428-012-1340-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Jia Yunlong, Wang Hongyan, Wang Yu, Wang Tingting, Wang Miao, Ma Ming, Duan Yuqing, Meng Xianli, Liu Lihua. Low expression of Bin1, along with high expression of IDO in tumor tissue and draining lymph nodes, are predictors of poor prognosis for esophageal squamous cell cancer patients. International Journal of Cancer. 2015;137(5):1095–1106. doi: 10.1002/ijc.29481. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Pelak MJ, Śnietura M, Lange D, Nikiel B, Pecka KM. The prognostic significance of indoleamine-2,3-dioxygenase and the receptors for transforming growth factor β and interferon γ in metastatic lymph nodes in malignant melanoma. Pol J Pathol. 2015;4:376–382. doi: 10.5114/pjp.2015.57249. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Ben-Haj-Ayed A, Moussa A, Ghedira R, Gabbouj S, Miled S, Bouzid N, Tebra-Mrad S, Bouaouina N, Chouchane L, Zakhama A, et al. Prognostic value of indoleamine 2,3-dioxygenase activity and expression in nasopharyngeal carcinoma. Immunol Lett. 2016;169:23–32. doi: 10.1016/j.imlet.2015.11.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Liu H, Shen Z, Wang Z, Wang X, Zhang H, Qin J, Qin X, Xu J, Sun Y. Increased expression of IDO associates with poor postoperative clinical outcome of patients with gastric adenocarcinoma. Sci Rep. 2016;6:21319. doi: 10.1038/srep21319. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Zhang T, Tan XL, Xu Y, Wang ZZ, Xiao CH, Liu R. Expression and prognostic value of Indoleamine 2,3-dioxygenase in pancreatic Cancer. Chin Med J. 2017;130(6):710–716. doi: 10.4103/0366-6999.201613. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Hudolin T, Mengus C, Coulot J, Kastelan Z, El-Saleh A, Spagnoli GC. Expression of Indoleamine 2,3-Dioxygenase gene is a feature of poorly differentiated non-muscle-invasive Urothelial cell bladder carcinomas. Anticancer Res. 2017;37(3):1375–1380. doi: 10.21873/anticanres.11458. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Carvajal-Hausdorf DE, Mani N, Velcheti V, Schalper KA, Rimm DL. Objective measurement and clinical significance of IDO1 protein in hormone receptor-positive breast cancer. J IMMUNOTHER CANCER. 2017;5(1):81. doi: 10.1186/s40425-017-0285-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Zhai L, Ladomersky E, Lauing KL, Wu M, Genet M, Gritsina G, Gyorffy B, Brastianos PK, Binder DC, Sosman JA, et al. Infiltrating T cells increase IDO1 expression in Glioblastoma and contribute to decreased patient survival. Clin Cancer Res. 2017;23(21):6650–6660. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-17-0120. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Ma W, Wang X, Yan W, Zhou Z, Pan Z, Chen G, Zhang R. Indoleamine-2,3-dioxygenase 1/cyclooxygenase 2 expression prediction for adverse prognosis in colorectal cancer. WORLD J GASTROENTERO. 2018;24(20):2181–2190. doi: 10.3748/wjg.v24.i20.2181. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Wei Y, Chu C, Chang C, Lin S, Su W, Tseng Y, Lin C, Yen Y. Different pattern of PD-L1, IDO, and FOXP3 Tregs expression with survival in thymoma and thymic carcinoma. Lung Cancer. 2018;125:35–42. doi: 10.1016/j.lungcan.2018.09.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Takeya H, Shiota T, Yagi T, Ohnishi K, Baba Y, Miyasato Y, Kiyozumi Y, Yoshida N, Takeya M, Baba H, et al. High CD169 expression in lymph node macrophages predicts a favorable clinical course in patients with esophageal cancer. Pathol Int. 2018;68(12):685–693. doi: 10.1111/pin.12736. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Kiyozumi Yuki, Baba Yoshifumi, Okadome Kazuo, Yagi Taisuke, Ishimoto Takatsugu, Iwatsuki Masaaki, Miyamoto Yuji, Yoshida Naoya, Watanabe Masayuki, Komohara Yoshihiro, Baba Hideo. IDO1 Expression Is Associated With Immune Tolerance and Poor Prognosis in Patients With Surgically Resected Esophageal Cancer. Annals of Surgery. 2019;269(6):1101–1108. doi: 10.1097/SLA.0000000000002754. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Nishi M, Yoshikawa K, Higashijima J, Tokunaga T, Kashihara H, Takasu C, Ishikawa D, Wada Y, Shimada M. The impact of Indoleamine 2,3-dioxygenase (IDO) expression on stage III gastric Cancer. Anticancer Res. 2018;38(6):3387–3392. doi: 10.21873/anticanres.12605. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Ahmadzada T, Lee K, Clarke C, Cooper WA, Linton A, McCaughan B, Asher R, Clarke S, Reid G, Kao S. High BIN1 expression has a favorable prognosis in malignant pleural mesothelioma and is associated with tumor infiltrating lymphocytes. Lung Cancer. 2019;130:35–41. doi: 10.1016/j.lungcan.2019.02.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Ma W, Duan H, Zhang R, Wang X, Xu H, Zhou Q, Zhang L. High expression of Indoleamine 2, 3-Dioxygenase in Adenosquamous lung carcinoma correlates with favorable patient outcome. J Cancer. 2019;10(1):267–276. doi: 10.7150/jca.27507. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Mitra D, Horick NK, Brackett DG, Mouw KW, Hornick JL, Ferrone S, Hong TS, Mamon H, Clark JW, Parikh AR, et al. High IDO1 expression is associated with poor outcome in patients with anal cancer treated with definitive chemoradiotherapy. Oncologist. 2019;24(6):e275–e283. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 41.Schollbach J, Kircher S, Wiegering A, Seyfried F, Klein I, Rosenwald A, Germer C, Löb S. Prognostic value of tumour-infiltrating CD8+ lymphocytes in rectal cancer after neoadjuvant chemoradiation: is indoleamine-2,3-dioxygenase (IDO1) a friend or foe? Cancer Immunol Immunother. 2019;68(4):563–575. doi: 10.1007/s00262-019-02306-y. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Boujelbene N, Ben Yahia H, Babay W, Gadria S, Zemni I, Azaiez H, Dhouioui S, Zidi N, Mchiri R, Mrad K, et al. HLA-G, HLA-E, and IDO overexpression predicts a worse survival of Tunisian patients with vulvar squamous cell carcinoma. HLA. 2019;94(1):11–24. doi: 10.1111/tan.13536. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Zhou Sha, Zhao Lei, Liang Zhaohui, Liu Songran, Li Yong, Liu Shiliang, Yang Hong, Liu Mengzhong, Xi Mian. Indoleamine 2,3-dioxygenase 1 and Programmed Cell Death-ligand 1 Co-expression Predicts Poor Pathologic Response and Recurrence in Esophageal Squamous Cell Carcinoma after Neoadjuvant Chemoradiotherapy. Cancers. 2019;11(2):169. doi: 10.3390/cancers11020169. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Tsai Y, Jou Y, Tsai H, Cheong I, Tzai T. Indoleamine-2,3-dioxygenase-1 expression predicts poorer survival and up-regulates ZEB2 expression in human early stage bladder cancer. Urol Oncol. 2019;37(11):810.e17–810.e27. doi: 10.1016/j.urolonc.2019.05.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Data Availability Statement

All data generated or analyzed during this study are included in this published article. The datasets used and/or analysed during the current study available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.