Abstract

Background

Rice is a chilling-sensitive crop that would suffer serious damage from low temperatures. Overexpression of the Lsi1 gene (Lsi1-OX) in rice enhances its chilling tolerance. This study revealed that a serine hydroxymethyltransferase (OsSHMT) mainly localised in the endoplasmic reticulum (ER) is involved in increasing tolerance to chilling.

Results

A higher transcription level of OsSHMT was detected in Lsi1-OX rice than in the wild type. Histone H1 and nucleic acid binding protein were found to bind to the promoter region of OsSHMT and regulate its expression, and the transcription levels of these proteins were also up-regulated in the Lsi1-OX rice. Moreover, OsSHMT interacts with ATP synthase subunit α, heat shock protein Hsp70, mitochondrial substrate carrier family protein, ascorbate peroxidase 1 and ATP synthase subunit β. Lsi1-encoded protein OsNIP2;1 also interacts with ATP synthase subunit β, and the coordination of these proteins appears to function in reducing reactive oxygen species, as the H2O2 content of transgenic OsSHMT Arabidopsis thaliana was lower than that of the non-transgenic line under chilling treatment.

Conclusions

Our results indicate that ER-localised OsSHMT plays a role in scavenging H2O2 to enhance the chilling tolerance of Lsi1-OX rice and that ATP synthase subunit β is an intermediate junction between OsNIP2;1 and OsSHMT.

Keywords: Rice, Chilling, Serine hydroxymethyltransferase, ROS, Protein-protein interactions

Background

Plants require a given temperature range for normal growth and development, and sudden changes in temperature can cause growth inhibition and even death [1]. Cold spells in late spring are examples of sudden drops in temperature over a short time and can adversely affect the growth of rice. Some varieties of rice, mainly those in the indica subspecies, are particularly sensitive to low temperatures [2, 3]. Continuous chilling of crop plants has been shown to result in increased reactive oxygen species (ROS) and cell membrane peroxidation and to affect the expression of chloroplast genes, inhibiting photosynthesis [4]. Such ROS include O2−, H2O2 and OH− [5].

Fang et al. [6] documented that chilling treatment inhibited the expression of chlorophyll synthesis genes and promoted the expression of proteasome genes from temperature-sensitive Dular rice (Oryza sativa ssp. indica), leading to chloroplast damage, chlorophyll degradation, loss of green colour and partial degradation of RNA in leaves. Cui et al. [7] found that the whitening of Dular leaves under chilling stress was associated with the deletion of the gene coding sequence of pentatricopeptide (LOC_Os09g29825.1), which is an RNA-binding protein, and the gene coding sequence missed 8 bases relative to that from Nipponbare rice, resulting in a frameshift mutation of the coding sequence and deactivation of the protein function. The mutant gene was named DUA1. Inactivation of the DUA1 protein in Dular rice leads to a loss of RNA editing capacity under chilling stress, resulting in rice seedlings that exhibit chloroplast development defects and leaf chlorosis. When the silicon-absorbing gene (Lsi1) was over-expressed in Dular rice, the chilling tolerance of the transgenic line was significantly improved, and the leaves maintained their fresh green colour under chilling treatment. The expression of genes from the photosynthesis pathway of transgenic rice was enhanced under low temperature stress, and the expression of genes involved in the proteasome was down regulated. In addition, the transcription level of the gene encoding serine hydroxymethyltransferase (SHMT, LOC_Os03g52840) was up-regulated in the transgenic rice, but down-regulated in the wild-type, and the expression of its corresponding miRNA changed in an opposite way, indicating that OsSHMT may be involved in regulating the chilling-tolerance of Dular [6].

SHMT is widely distributed in plants [8]. The enzyme catalyses the reversible exchange between serine and glycine (glycine CH2-THF H2O↔serine THF) [9, 10], and these two amino acids are precursors of chlorophyll, tryptophan and ethanolamine [11]. Therefore, SHMT plays an important role in the photorespiration processes of plants [12]. Studies have found that a mitochondrial serine hydroxymethyltransferase gene mutation in rice (osshm1) causes blockage of the photorespiration pathway, thereby affecting the Calvin cycle and the efficiency of light energy; excess light in the chloroplast then leads to the accumulation of ROS, resulting in disruption of chloroplast development and fewer and smaller chloroplasts with less grana [13].

In addition, SHMT plays a positive role in regulating plants’ resistance to stress. In Arabidopsis, expression of NADH dehydrogenase was shown to be inhibited by chilling, leading to the continuous accumulation of ROS, suppressing the transcription of cold-response genes and hypersensitivity to chilling [14]. SHMT activity contributes to a reduction of ROS accumulation in the chloroplast and therefore reduces oxidative damage [15]; as a second messenger, a reduction in ROS would also prevent the transmission of the chilling signal and reduce the damage caused by ROS. The recessive mutation shmt1–1 in Arabidopsis results in abnormal regulation of cell death, leading to chlorotic and necrotic diseases under various environmental conditions, and mutants that carry the shmt1–1 allele exhibit more H2O2 accumulation than wild-type plants under salt stress, resulting in greater chlorophyll loss [16]. To the best of our knowledge, the specific role of OsSHMT in the regulation of rice cold resistance has not been reported.

In this study, an OsSHMT gene (LOC_Os03g52840) from rice was amplified, the subcellular localisation of OsSHMT was investigated, and proteins that bind to the promoter region of OsSHMT were obtained. The proteins that interact with OsSHMT were also investigated to indicate the regulation network of OsSHMT in rice under chilling stress, revealing the possible role of OsSHMT in scavenging H2O2 to improve cold resistance in rice.

Results

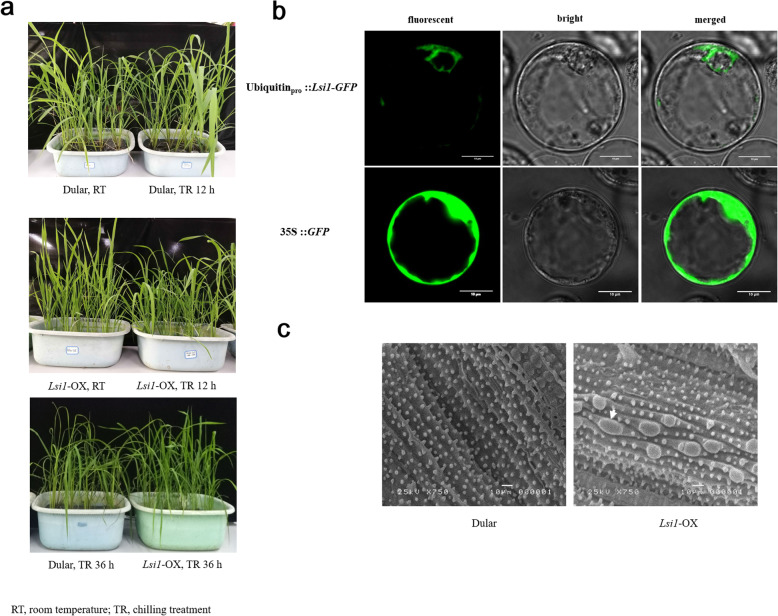

Chilling tolerance of Dular and Lsi1-OX rice

The Dular and Lsi1-OX transgenic lines presented different tolerances to the chilling treatment of 4 °C for 36 h. Most of the leaves from the Dular rice became whiter, whilst the Lsi1-OX line maintained tolerance to chilling (Fig. 1a). Further studies showed that the Lsi1 overexpression vector was driven by the ubiquitin promoter, and the translate OsNIP2;1 was localised in the cytoplasm (Fig. 1b), which differs significantly from the original localisation in the cell membrane [17]. This result suggests that OsNIP2;1 may have more roles than its initial function, which belongs to the aquaporin family and controls silicon accumulation in rice [17]. Scanning electron microscope (SEM) images of the leaves revealed that silica bodies in the Lsi1-OX rice leaves were bigger than those of the Dular rice (Fig. 1c).

Fig. 1.

Phenotypic changes in the leaves under chilling treatment (a), subcellular localisation of Lsi1 driven by ubiquitin promoter (b) and SEM images of the leaf surface of Dular and Lsi1-OX (c). The Dular rice and the transformed Lsi1-OX line were treated at 4 °C for 36 h and the phenotypic changes in the leaves of the two rice lines were compared (a). Lsi1 was fused with GFP and inserted into a modified pCambia 1301 vector in which the Lsi1 gene was transcribed by the ubiquitin promoter. The recombinant Lsi1 expression vector was transformed in the rice protoplast and subcellular localisation of OsNIP2;1 was detected using laser scanning confocal microscopy (b). SEM images of the surfaces of the two rice leaves were compared to determine the differences in silica deposition (c)

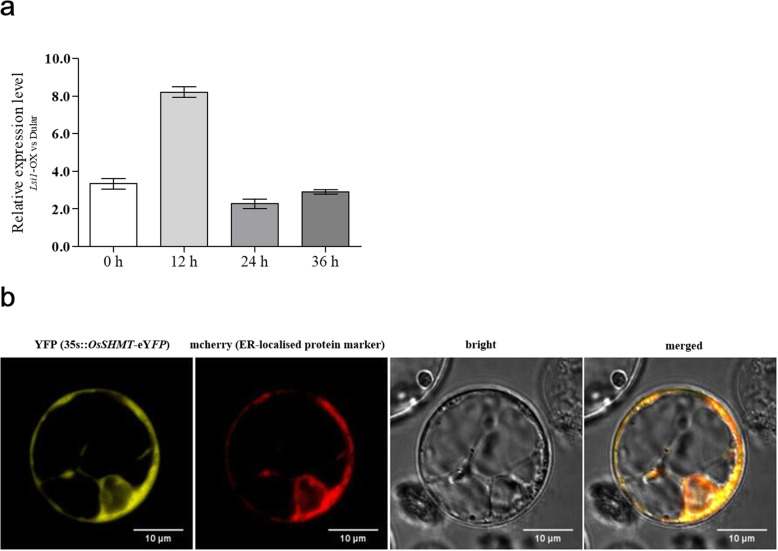

Subcellular localisation of OsSHMT

Overexpression of Lsi1 in Dular rice results in changes in the expression of thousands of genes [6], including the OsSHMT gene. Expression of OsSHMT was up-regulated in the Lsi1-OX rice in comparison with the Dular rice (Fig. 2a). Subcellular localisation of OsSHMT (LOC_Os03g52840) in the rice protoplast then showed that yellow fluorescence was concentrated around the nucleus, and no obvious endonuclear fluorescence was observed, whereas significant yellow fluorescence was seen in the whole nucleus in the rice protoplast transformed with the eYFP vector (Fig. S1). This suggested that OsSHMT was localised on the endoplasmic reticulum around the nucleus. Further co-localisation of the endoplasmic reticulum marker protein with mcherry indicated that OsSHMT was widely distributed in the endoplasmic reticulum, as the mcherry fluorescence from the marker protein and yellow fluorescence from OsSHMT infused with eYFP was completely overlapping (Fig. 2b). OsSHMT is involved in the photorespiratory processes of plants, and existing studies have suggested that the protein is localised to mitochondria, chloroplasts and cytoplasm. The results of this study complement those findings.

Fig. 2.

Relative expression of OsSHMT in the Lsi1-OX rice line and Dular rice (a) and subcellular co-localisation of OsSHMT protein with endoplasmic reticulum marker protein (b). Changes in the gene expression level of OsSHMT before chilling treatment and after treatment for 12, 24 and 36 h were compared for Lsi1-OX and Dular rice (a). OsSHMT was fused with eYFP and inserted into pCambia 2300 to construct the recombinant vector for OsSHMT expression and detect subcellular protein localisation. The recombinant vector was transformed into rice protoplast for transient expression, together with a mcherry fused ER localised protein as a marker. Yellow fluorescence and mcherry fluorescence were respectively detected and then merged to validate the OsSHMT subcellular localisation (b)

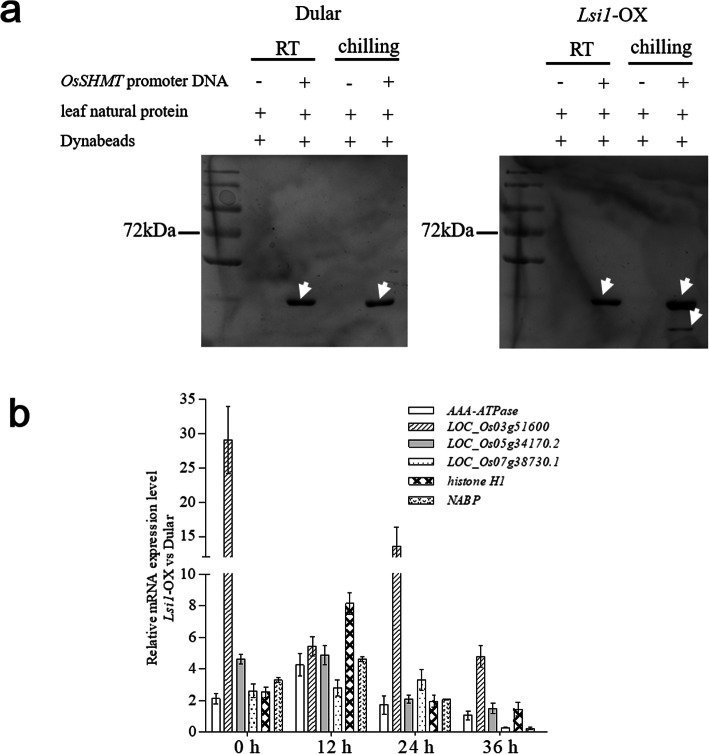

Promoter region of OsSHMT and the binding proteins

The promoter region 2597 bp upstream of the CDS of the OsSHMT gene from Dular rice was amplified and labelled with biotin at the 5′ flanking region of this DNA fragment (Table S1). According to the DNA pull-down results, compared with the control group at room temperature, chilling treatment of Lsi1-OX induced more proteins to bind to the promoter region of OsSHMT. In contrast, chilling treatment of the Dular rice had no significant effect on the proteins binding to the promoter (Fig. 3a). Identification of the proteins showed that retrotransposon protein (Ty3-gypsy subclass), glyceraldehyde-3-phosphate dehydrogenase, and AT hook motif protein were identified from both the Lsi1-OX and Dular rice under chilling treatment or room temperature conditions; however, some proteins, such as histone H1, nucleic acid binding protein (NABP) and tubulin/FtsZ domain-containing protein (LOC_Os03g51600.1) were only identified from the chilling-treated Lsi1-OX group; another tubulin/FtsZ domain-containing protein (LOC_Os05g34170.2) was identified from the chilling-treated Lsi1-OX and Dular groups and from the Dular group at room temperature. AAA-type ATPase family protein was identified from the Dular group at room temperature but not from the chilling-treated Dular group, and this protein was induced in the chilling-treated Lsi1-OX group in comparison with its control group at room temperature (Table 1). The tubulin/FtsZ domain-containing proteins (LOC_Os03g51600.1, LOC_Os05g34170.2, LOC_Os07g38730.1), histone H1 and NABP were selected to analysis their gene expression level on the two rice. A comparison of the gene transcription levels in Dular and Lsi1-OX rice after chilling treatment for 12, 24 and 36 h in comparison with 0 h, revealed opposite trends in the two rice lines, and the gene expression level was up-regulated in the Lsi1-OX rice in comparison with Dular rice under the same treatment conditions (Fig. 3b). The results indicate that these genes act in combination to exert a positive role in the regulation of OsSHMT expression.

Fig. 3.

Proteins binding on the OsSHMT-promoter in Dular and Lsi1-OX rice and the differences in transcription level between the two types of rice. The promoter region of OsSHMT was amplified using the specific primers with biotin labelled at the 5′ end and then fused with Streptavidin-coupled Dynabeads and natural leaf proteins from Dular or Lsi1-OX rice. The protein and DNA complex mixture was extracted and incubated with OsSHMT promoter-containing Dynabeads and fished using a magnetic frame to collect the proteins and then separated by SDS-PAGE (a). qPCR was conducted to determine the change in the transcription levels of AA-ATPase, histone H1, nucleic acid binding protein (NABP) and tubulin/FtsZ domain containing protein (LOC_Os03g51600, LOC_Os05g34170, LOC_Os07g38730) for Lsi1-OX and Dular rice under chilling treatment of different durations (d)

Table 1.

Proteins binding on the OsSHMT gene promoter from Dular and Lsi1-OX

| Protein ID | Unique peptide number | Unique spectra number | Coverage | Description |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Dular, RT | ||||

| LOC_Os03g58470.1 | 11 | 121 | 0.3481 | retrotransposon protein, putative, Ty3-gypsy subclass, expressed |

| LOC_Os04g58730.1 | 4 | 6 | 0.1527 | AT hook motif domain containing protein, expressed |

| LOC_Os03g03720.1 | 4 | 4 | 0.1261 | glyceraldehyde-3-phosphate dehydrogenase, putative, expressed |

| LOC_Os12g37260.1 | 3 | 3 | 0.0434 | lipoxygenase 2.1, chloroplast precursor, putative, expressed |

| LOC_Os11g47970.1 | 3 | 3 | 0.0687 | AAA-type ATPase family protein, putative, expressed |

| LOC_Os04g42320.1 | 3 | 3 | 0.0414 | AT hook motif family protein, expressed |

| LOC_Os07g08710.1 | 3 | 3 | 0.1871 | AT hook-containing DNA-binding protein, putative, expressed |

| Dular, chilling | ||||

| LOC_Os03g58470.1 | 10 | 130 | 0.3311 | retrotransposon protein, putative, Ty3-gypsy subclass, expressed |

| LOC_Os04g58730.1 | 4 | 8 | 0.1527 | AT hook motif domain containing protein, expressed |

| LOC_Os07g08710.1 | 4 | 9 | 0.223 | AT hook-containing DNA-binding protein, putative, expressed |

| LOC_Os05g34170.2 | 4 | 7 | 0.1036 | tubulin/FtsZ domain containing protein, putative, expressed |

| LOC_Os03g03720.2 | 3 | 4 | 0.1226 | glyceraldehyde-3-phosphate dehydrogenase, putative, expressed |

| Lsi1-OX, RT | ||||

| LOC_Os03g58470.1 | 10 | 145 | 0.3447 | retrotransposon protein, putative, Ty3-gypsy subclass, expressed |

| LOC_Os04g42320.1 | 6 | 9 | 0.0674 | AT hook motif family protein, expressed |

| LOC_Os01g72049.1 | 5 | 5 | 0.1975 | retrotransposon, putative, centromere-specific, expressed |

| LOC_Os05g34170.2 | 3 | 4 | 0.0811 | tubulin/FtsZ domain containing protein, putative, expressed |

| LOC_Os07g38730.1 | 2 | 2 | 0.0444 | tubulin/FtsZ domain containing protein, putative, expressed |

| Lsi1-OX, chilling | ||||

| LOC_Os03g58470.1 | 15 | 205 | 0.3823 | retrotransposon protein, putative, Ty3-gypsy subclass, expressed |

| LOC_Os05g51850.1 | 8 | 8 | 0.1413 | AT hook-containing DNA-binding protein, putative, expressed |

| LOC_Os04g58730.1 | 7 | 10 | 0.2506 | AT hook motif domain containing protein, expressed |

| LOC_Os11g47970.1 | 6 | 6 | 0.1309 | AAA-type ATPase family protein, putative, expressed |

| LOC_Os01g72049.1 | 6 | 6 | 0.1975 | retrotransposon, putative, centromere-specific, expressed |

| LOC_Os04g42320.1 | 6 | 7 | 0.0721 | AT hook motif family protein, expressed |

| LOC_Os07g08710.1 | 5 | 9 | 0.2662 | AT hook-containing DNA-binding protein, putative, expressed |

| LOC_Os04g49990.1 | 4 | 5 | 0.2507 | AT hook motif domain containing protein, expressed |

| LOC_Os05g34170.2 | 4 | 5 | 0.1059 | tubulin/FtsZ domain containing protein, putative, expressed |

| LOC_Os08g40150.1 | 3 | 3 | 0.1102 | AT hook motif domain containing protein, expressed |

| LOC_Os04g38600.2 | 3 | 3 | 0.1111 | glyceraldehyde-3-phosphate dehydrogenase, putative, expressed |

| LOC_Os06g04020.1 | 3 | 3 | 0.1458 | histone H1, putative, expressed |

| LOC_Os03g52490.1 | 2 | 2 | 0.098 | nucleic acid binding protein, putative, expressed |

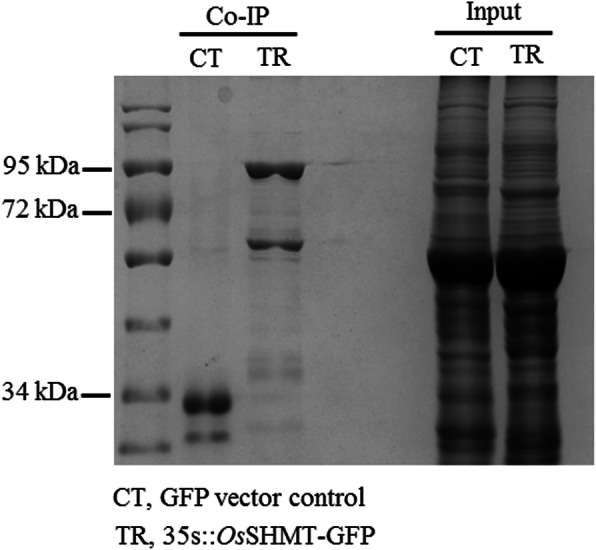

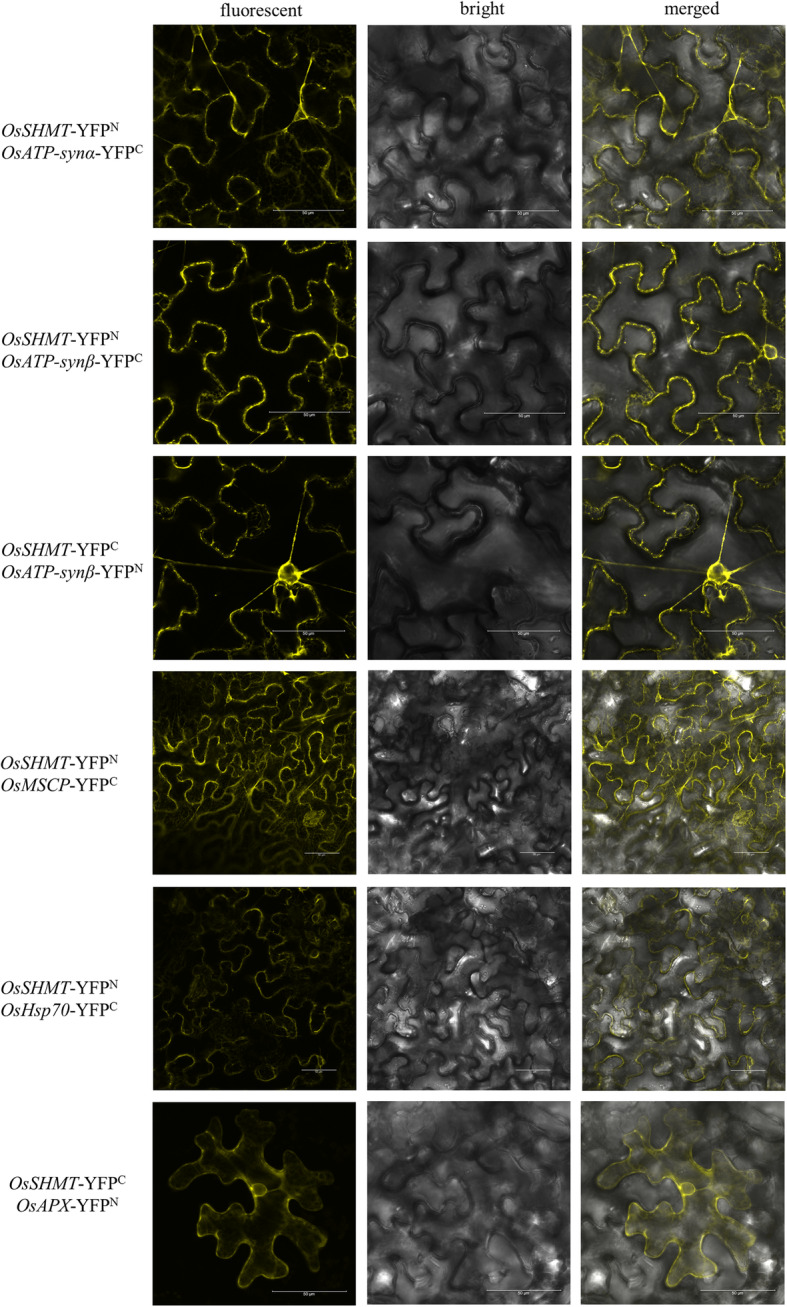

Proteins interacting with OsSHMT

Based on the GFP-TRAP method to obtain the proteins interacting with OsSHMT, it was found that several proteins co-precipitated with OsSHMT, in comparison with the GFP-vector control (Fig. 4; Table S2). Some of these proteins, including ATP synthase α subunit, ATP synthase β subunit, heat shock protein 70, mitochondrial substrate carrying family protein E, ascorbate peroxidase 1, are defense proteins that interact with OsSHMT protein (Table 2). Further determination of the interaction of OsSHMT with ATP synthase subunit α, ATP synthase subunit β, Hsp70, MSCP and APX from the rice showed that yellow fluorescence was detected in the leaves of tobacco infected with OsSHMT and each of these proteins respectively. No fluorescence was detected in the control group, demonstrating that OsSHMT positively interacts with the above proteins (Fig. 5). The results indicate that OsSHMT interacted with defence-related proteins in rice, including APX, MSCP, HSP70 and ATP synthase, to jointly regulate chilling resistance.

Fig. 4.

Protein interactions with OsSHMT in Arabidopsis thaliana. The recombinant vector of OsSHMT fused with GFP was used to genetically transform Arabidopsis thaliana and T3 homozygous transgenic lines were taken to isolate proteins interacting with OsSHMT. A vector containing only GFP without OsSHMT was used as a control to transform into A. thaliana to obtain the transformed lines. Natural leaf proteins from OsSHMT transgenic A. thaliana and GFP transgenic A. thaliana were respectively extracted and incubated with GFP-Trap agarose beads to reveal the proteins interacting with OsSHMT

Table 2.

The target protein from rdr6 interacted with OsSHMT identified by LC-MS

| Accession | Description | Sum PEP Score | Coverage | Peptides | PSMs | Unique Peptides |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| ATCG00480.1 | ATP synthase subunit beta | 39.443 | 50.60241 | 19 | 35 | 18 |

| ATCG00120.1 | ATP synthase subunit alpha | 30.137 | 26.82446 | 13 | 28 | 11 |

| AT1G07890.2 | ascorbate peroxidase 1 | 9.281 | 37.6 | 7 | 8 | 7 |

| AT5G02490.1 | Heat shock protein 70 (Hsp 70) family protein | 15.568 | 9.035222 | 5 | 7 | 5 |

| AT5G46800.1 | Mitochondrial substrate carrier family protein | 5.09 | 10 | 4 | 4 | 4 |

| ATCG00480.1 | ATP synthase subunit beta | 6.277 | 8.634538 | 3 | 3 | 3 |

Fig. 5.

Bimolecular fluorescence complementation validation of the bio-interaction of OsSHMT and ATP synthase subunit α, ATP synthase subunit β, Hsp70, MSCP and APX from rice. To validate the positive interaction of OsSHMT with ATP synthase α subunit (ATP-synα), ATP synthase β subunit (ATP-synβ), heat shock protein 70, mitochondrial substrate carrying family (MSCP) protein E and ascorbate peroxidase (APX) in rice, their genes were amplified from Dular rice and respectively infused with the N-terminal or C-terminal of YFP to construct YFPn- and YFPc-containing recombinant vectors for bimolecular fluorescence complementation (BiFC), according to transient transformation in the leaves of Nicotiana benthamiana. The YFP fluorescence was detected using laser confocal microscopy under 488-nm excitation light

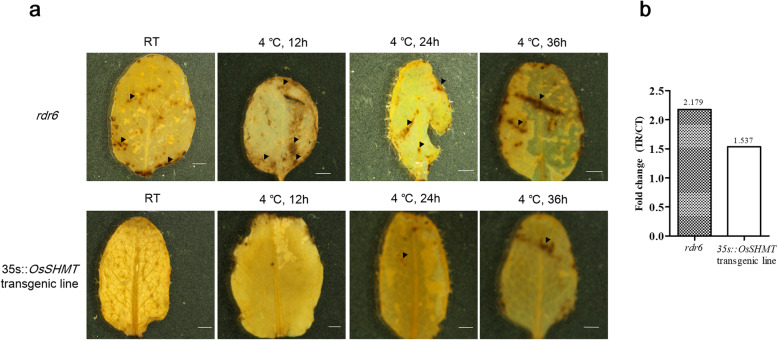

H2O2 content in the OsSHMT transgenic A. thaliana and wild type

To further indicate the function of OsSHMT in scavenging H2O2, wildtype A. thaliana and positive transgenic T3A. thaliana seedlings were exposed to a temperature of 4 °C for 12, 24 and 36 h. The leaves of the wild type showed more reddish-brown spots after Diaminobenzidine (DAB) staining. The transgenic line also showed reddish-brown spots, but the spots were small in size and number (Fig. 6a). Determination of the leaf H2O2 content of the transgenic line and wild type of A. thaliana showed that the increase in H2O2 in the transgenic line of A. thaliana after chilling treatment was significantly lower than that of the wild type that underwent the same treatment (Fig. 6b).

Fig. 6.

DAB staining of leaves of OsSHMT transgenic and wild type A. thaliana (a) and the H2O2 content in the leaves (b). OsSHMT transgenic Arabidopsis thaliana and its wild-type were exposed to 0 °C for 12, 24 and 36 h, and leaves were sampled and stained with DAB, after which the chlorophyll in the leaves was dissolved using ethanol, leaving dark brown precipitate on the leave. Arrowheads indicate reddish-brown spots. Bar = 1 mm. The H2O2 content in the leaves was determined using an H2O2 determination kit (Solarbio Life Sciences)

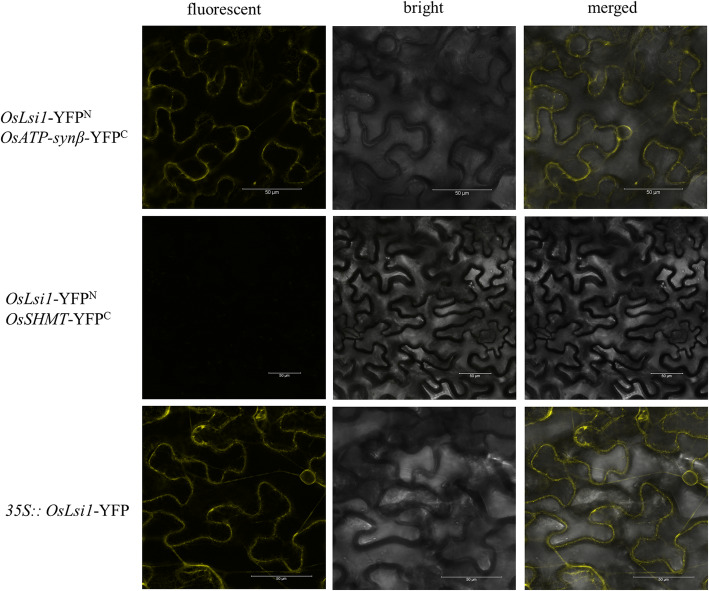

OsNIP2;1 interacts with ATP synthase subunit β from rice

Lsi1 encodes the aquaporins protein OsNIP2;1, which is a nodulin 26-like intrinsic protein (NIP) and is localised in the membrane of the cell. Overexpression of Lsi1 in Dular rice using a ubiquitin promoter resulted in the cytoplasm localisation of this protein, enabling OsNIP2;1 to play multiple roles. The interaction between OsNIP2;1 and OsSHMT was also investigated. The results showed no direct interaction between OsNIR2;1 and OsSHMT. However, OsNIP2;1 interacted with ATP-synβ, a protein that also interacts with OsSHMT, and the results indicate that ATP-synβ acts as an intermediate junction between OsNIP2;1 and OsSHMT (Fig. 7).

Fig. 7.

Bimolecular fluorescence complementation validates the bio-interaction of OsNIP2;1 and ATP-synβ. Lsi1 was infused with the N-terminal domain of YFP and ATP synthase subunit β and OsSHMT was infused with the C-terminal domain of YFP. Lsi1 with N-terminal domain was then co-expressed with ATP synthase subunit β or OsSHMT with the C-terminal domain of YFP, respectively, in the leaves of Nicotiana benthamiana for 48 h, and YFP fluorescence was detected using laser confocal microscopy under 488-nm excitation light. The subcellular localisation of Lsi1 was also detected in the leaves of Nicotiana benthamiana

Discussion

Plant suffers from low-temperature frequently results in the accumulation of ROS, which would lead to lipid peroxidation of the cell membrane. Our studies here indicated that OsSHMT functions in scavenging H2O2 in the plant. OsSHMT has been declared to be localised in the mitochondria, chloroplast, cytoplasm, nucleus, plasma membrane and cytosol [13, 18, 19], and participates in the photorespiration pathway. Besides, our present study indicated that OsSHMT is also localised in the endoplasmic reticulum, which is the main organelle for protein and lipid synthesis, membrane biogenesis, xenobiotic detoxification and cellular calcium storage [20]. The activity of OsSHMT in scavenging H2O2 is considered to be prominent when the rice undergoes chilling stress.

With scavenging of H2O2, OsSHMT was found to be interacted with a couple of proteins. Among these interacted proteins, APX is the one with ROS-scavenging activity. In Arabidopsis thaliana, the cytosolic ascorbate peroxidase 1 (APX1) is a central component of the H2O2-scavenging system, absence of APX1 in the knock-out lines lead to the collapse of the chloroplast H2O2 clearance system, thereby increasing levels of H2O2 and oxidative proteins [21]. The heat shock protein Hsp70 also interacts with OsSHMT. Hsp70 is a molecular chaperone protein and plays a critical role in stress tolerance [22]; in rice, chloroplast-localised Hsp70 is essential for chloroplast development under high-temperature conditions, whilst overexpression of mitochondrial HSP70 in rice suppresses programmed cell death [23, 24]. It is therefore suggested that the multiple functions of Hsp70 contribute to enhancing rice chilling tolerance. As ATP is required in the catalytic reaction to scavenging ROS, OsSHMT also interacts with subunit α and subunit β of ATP synthase. These subunits are widely distributed in mitochondria and chloroplasts, and the synergistic effect of subunits function in produced ATP from ADP in the presence of a proton gradient across the membrane, which is generated by electron transport complexes of the respiratory chain [25], and the mitochondrial substrate carrier family proteins catalyse the passage of hydrophilic compounds such as ADP/ATP across the inner mitochondrial membrane [26]. The coordination of these proteins appears to provide ATP for OsSHMT activating in scavenging H2O2.

As the dominant role of OsSHMT in scavenging H2O2, increasing expression level of OsSHMT contributes to enhance its capacity. Gene expression of OsSHMT was higher in the Lsi1-OX rice than that in its wild-type Dular [6]. The different expression level of OsSHMT from these two rice lines mainly attributes to the expression of transcription regulators to OsSHMT. NABP and histone H1 were two transcription regulators binding on the promoter of OsSHMT. NABP has a dual role in regulation of gene expression at the transcriptional and posttranscriptional levels [27, 28]. Histones in eukaryotes are structural proteins that bind to DNA to construct chromatin nucleosomes. Histone H1 is commonly considered a transcriptional repressor because it prevents transcription factors and chromatin remodelling complexes from entering DNA [29]. Some other proteins, including AAA-ATPase family proteins and tubulin/FtsZ domain containing protein, were co-occurrence in these DNA-binding proteins. Tubulin is the main component of plant microtubules, which plays an important part in the regulation of stress tolerance and thus responds to a variety of intracellular and external stimuli [30–32]. Higher transcriptional levels of these genes in the Lsi1-OX rice than those in Dular, suggesting that these factors have a positive impact in regulating the expression of OsSHMT gene. Whether these proteins are precisely or indirectly linked to the OsSHMT gene promoter remains to be revealed.

Overexpression of Lsi1 in the Dular results in the endoplasmic reticulum localisation of Lsi1-encoded Nod26-like intrinsic protein (OsNIP2;1). Since OsSHMT is also localised on the endoplasmic reticulum, the interactions of ATP synthase β subunit respectively with OsNIP2;1 and OsSHMT, indicating that OsNIP2;1 can indirectly cooperate with OsSHMT through the ATP synthase β subunit, and that OsSHMT interacts with defence and anti-oxidation related proteins to regulate the chilling resistance of rice and ensure its normal growth and development. The increase in OsSHMT expression and its constructive role in scavenging H2O2 provides partial assistance to rescue the loss of chilling resistance in Dular rice due to the inactivation of DUA1.

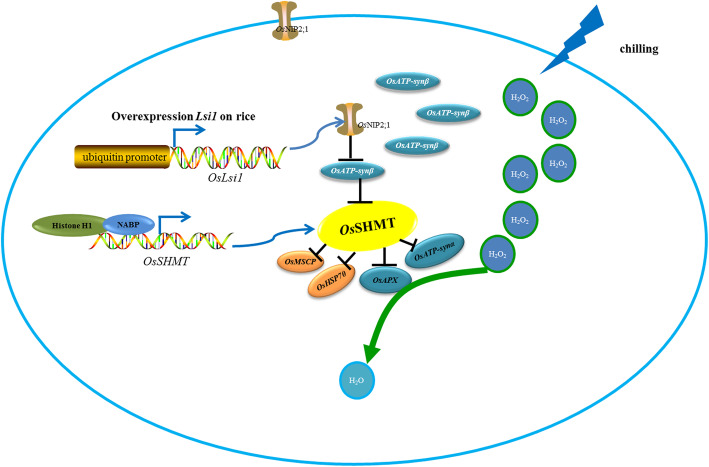

Conclusions

Overexpression of Lsi1 in chilling-sensitive Dular rice resulted in the plasma membrane-localized OsNIP2;1 protein expressed in the cytoplasm, which would enable OsNIP2;1 to perform multiple roles. The expression of OsSHMT was up-regulated in the Lsi1-OX line in comparison with the Dular line. The differential gene expression level of OsSHMT may be transcriptionally regulated by NABP, and histone H1. In addition, OsSHMT interacts with APX, Hsp70, ATP-synα, ATP-synβ and MSCP to scavenge H2O2, and ATP-synβ interacts with OsNIP2;1. Even OsSHMT does not directly interact with OsNIP2;1, ATP synthase subunit β is an intermediate junction between OsNIP2;1 and OsSHMT (Fig. 8).

Fig. 8.

Schematic summary of the role of OsSHMT in the regulation of rice chilling tolerance. OsSHMT interacts with APX, HSP70, MSCP, ATP-synα and ATP-synβ to scavenge H2O2. ATP-synβ also interacts with OsNIP2;1 in the cytoplasm when the ubiquitin promoter is used to overexpress Lsi1 in the rice

Methods

Plant materials and treatments

In this study, Dular rice (Oryza sativa L. subsp. indica) and its transgenic line with Lsi1 overexpression (Lsi1-OX) were used; Dular rice is saved at Fujian Agriculture and Forestry Universtiy (Fuzhou, China) and the Lsi1-OX transgenic line of Dular was germinated in our previous studies [33]. Arabidopsis thaliana with an RNA-dependent RNA polymerase 6 gene mutation (rdr6) [34] and Nicotiana benthamiana [35] were also used in this study.

The Dular and Lsi1-OX rice seeds were sterilised with 25% sodium hypochlorite solution (W/V) for 30 min and washed with sterile water to remove any residues. The sterilised seeds were soaked overnight at 30 °C in an incubator. The seeds were germinated and sown in black pots filled with a hydroponic nutrient solution suspended in a polyethylene mesh. The pots were placed in an artificial climate chamber for 10 days, during which a temperature of 26 °C was maintained for 14 h and darkness was maintained for 10 h at 22 °C. The relative humidity in the chamber was maintained at about 85%. The nutrient solution was changed weekly, and the pH was maintained between 5.5 and 6.0 throughout the experiment.

When the rice had reached the three-leaves stage, the Lsi1-OX and wild-type Dular that treated at 12 °C/10 °C (day/night) were set as treatment groups, and the control groups were these two rice lines that placed in another chamber with day/night temperatures of 26 °C/22 °C. Both the treatment and the control groups for each rice line had four replicates and they were both repeated three times in the same growth chamber.

Protein sub-localisation

The coding DNA sequence of OsSHMT (LOC_Os03g52840) was amplified and fused with eYFP in the pCambia2300 to construct a recombinant 35S::OsSHMT-eYFP vector for rice protoplast transformations. Subcellular localisation of OsSHMT was detected using confocal laser scanning microscopy. An organelle-specific protein marker (mcherry) was co-localised with OsSHMT to validate the above results. At the same time, a blank vector that contained only the yellow fluorescent protein gene was separately transferred into the rice protoplast to serve as a reference. The rice protoplasts were cultured at 28 °C for 48 h. The distribution of yellow fluorescence in the protoplast was observed by laser confocal microscopy to determine the subcellular localisation of OsSHMT protein.

DNA pull-down fishes transcription regulators binding to the promoter of OsSHMT

The second-topmost leaves of the four replicates were respectively sampled at 48 h after chilling treatment. These rice leaves were quickly frozen in liquid nitrogen. The natural leaf proteins of Dular and Lsi1-OX were extracted using Pi-IP buffer (50 mM Tris·Cl, 150 mM NaCl, 1 mM EDTA pH 8.0, 1% Triton X-100, 1 mM PMSF, 1× EDTA-free Protease Inhibitor Cocktail, Roche, Merck) (Method S1). The promoter region (2549 bp upstream of the CDS of OsSHMT) was cloned from the genomic DNA of Dular, and the interacting proteins on the promoter were obtained following the protocols of our previous studies [36].

Quantitative PCR to determine gene expression level

Total RNA from Dular and Lsi1-OX rice exposed to a temperature of 15 °C for 12, 24 and 36 h was extracted using Trizol and reverse-transcribed into cDNA using TransScript One-Step gDNA Removal and cDNA Synthesis SuperMix. The control groups were grown at 26 °C for 12, 24 and 36 h. Specific primers for tubulin/FtsZ domain containing protein (LOC_Os03g51600, LOC_Os05g34170, LOC_Os07g38730), histone H1 and nucleic acid binding protein (NABP) are listed in Table S3; the β-actin gene was taken as the reference. The qPCR reaction system was prepared using TransStart Tip Green qPCR SuperMix and an Eppendorf realplex4 instrument. The reaction process was as follows: pre-denaturation at 94 °C for 30 s, denaturation at 94 °C for 5 s, annealing at 55 °C for 15 s, extension at 72 °C for 10 s; 42 cycles. When the amplification was finished, analysing of the melting curve was conducted and specificity of the product was determined based on the melting curve. Each candidate mRNA was set with four independent replicates. The relative expression of the gene was calculated by the 2-△△Ct method with the threshold cycle values (Ct) of each candidate mRNA in both the control and test samples [37].

Arabidopsis thaliana transformation

The CDS of OsSHMT was amplified and inserted into modified pCambia3301 (with 35 s promoter) to construct the recombinant vector for Arabidopsis thaliana transformation using the floral dip protocols described by Clough and Bent [38]. Natural leaf proteins were extracted from a T3 generation homozygote of OsSHMT transgenic A. thaliana and incubated with GFP-Trap agarose (Chromotek) to collect putative interacting proteins.

Bimolecular fluorescence complementation (BiFC) validates rice protein interactions

BiFC was conducted to validate the possible interactions between OsSHMT and the proteins identified from the Co-IP results. The genes that encode these proteins were cloned from Dular rice, construction of recombinant vectors for each gene and the subsequent protocols for BiFC are available in our previous studies [36].

DAB staining and determination of H2O2 content

Detection of H2O2 in leaves was conducted using diaminobenzidine (DAB) staining; OsSHMT transgenic A. thaliana and its wild type were treated at 4 °C for 12, 24 and 36 h. The treatment was repeated three times in the same growth chamber. Leaves from these two lines were sampled and immersed in 50 mg/L DAB solution by vacuum-pumping for 1 h and incubated overnight at room temperature. These leaves were then decolourised with 95% ethanol in a water bath at 80 °C, and the reddish brown spots in the transgenic leaves and wild-type leaves were observed using an integrated microscope (Nikon, SMZ18). The H2O2 content in the 12 h-treated leaves of the transgenic line and the wild type were determined using an H2O2 determination kit (Solarbio Life Sciences).

Primer sequences

A list of the primers is provided in Table S3.

Supplementary information

Additional file 1 Fig. S1 Subcellular localisation of OsSHMT protein in rice protoplast

Additional file 2 Table S1 Sequence of OsSHMT gene promoter from Dular. Table S2 Proteins interacted with OsSHMT in the OsSHMT transgenic A. thaliana using GFP-Trap Co-IP. Table S3 Primers used in this study

Additional file 3 Methods S1 Extraction of rice leaf protein

Additional file 4 Electronic Supplementary Material 1. Full length gel presents proteins binding on the OsSHMT-promoter in Dular

Additional file 5 Electronic Supplementary Material 2. Full length gel presents proteins binding on the OsSHMT-promoter in Lsi1-OX transgenic line

Additional file 6 Electronic Supplementary Material 3. Full length gel presents protein interactions with OsSHMT in Arabidopsis thaliana

Acknowledgements

We thank Basic Forestry and Proteomics Research Centre in Fujian Agriculture and Forestry University for providing seeds of Arabidopsis thaliana and Nicotiana benthamiana, and green house for the plant growth.

Abbreviations

- APX

Ascorbate peroxidase

- BiFC

Bimolecular fluorescence complementation

- DAB

Diaminobenzidine

- ER

Endoplasmic reticulum

- Lsi1

Low silicon gene 1

- OX

Overexpression

- SHMT

Serine hydroxymethyltransferase

- NIP

Nodulin 26-like intrinsic protein

- ROS

Reactive oxygen species

- NABP

Nucleic acid binding protein

- HSP70

Heat shock protein 70

Authors’ contributions

CF and WL designed the experiments. PZ, LL and CF performed most of experiments and analyzed the data. LY, DM, XY and ZL assisted in experiments and discussed the results. CF and WL wrote the manuscript. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Funding

This work was supported by the National Natural Science Foundation of China (Grant No. 31871556), the Outstanding Youth Scientific Fund of Fujian Agriculture and Forestry University (Grant No. xjq201805), Open Project Program of the Key Laboratory of Ministry of Education for Genetics, Breeding and Multiple Utilization of Crops, College of Crop Science, Fujian Agriculture and Forestry University (Grant No. GBMUC-2018-001), Fujian-Taiwan Joint Innovative Center for Germplasm Resources and Cultivation of Crop (FJ 2011 Program, No. 2015–75), Foundation for the Science and Technology Innovation of Fujian Agriculture and Forestry University (Grant No. CXZX2017310, CXZX2017145, CXZX2018042), and Foundation of Institute of Modern Seed Industrial Engineering. The funders had no role in study design, data collection and analysis, data interpretation, or in writing of the manuscript.

Availability of data and materials

All data generated during this study are included in this published article and its supplementary information files, and the raw data used or analysed during the current study available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

Ethics approval and consent to participate

Not applicable.

Consent for publication

Not applicable.

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Footnotes

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Changxun Fang and Pengli Zhang contributed equally to this work.

Supplementary information

Supplementary information accompanies this paper at 10.1186/s12870-020-02446-9.

References

- 1.Hatfield JL, Prueger JH. Temperature extremes: effect on plant growth and development. Weather Clim Extr. 2015;10:4–10. doi: 10.1016/j.wace.2015.08.001. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Zhao XQ, Wang WS, Zhang F, Zhang T, Zhao W, Fu BY, Li Z-K. Temporal profiling of primary metabolites under chilling stress and its association with seedling chilling tolerance of rice (Oryza sativa L.) Rice. 2013;6:23. doi: 10.1186/1939-8433-6-23. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Wang D, Liu J, Li C, Kang H, Wang Y, Tan X, Liu M, Deng Y, Wang Z, Liu Y, Zhang D, Xiao Y, Wang G-L. Genome-wide association mapping of cold tolerance genes at the seedling stage in rice. Rice. 2016;9:61. doi: 10.1186/s12284-016-0133-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Gill SS, Tuteja N. Reactive oxygen species and antioxidant machinery in abiotic stress tolerance in crop plants. Plant Physiol Biochem. 2010;48:909–930. doi: 10.1016/j.plaphy.2010.08.016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Glasauer A, Chandel NS. ROS. Curr Biol. 2013;23:R100–02. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 6.Fang CX, Zhang PL, Jian X, Chen WS, Lin HM, Li YZ, Lin WX. Overexpression of Lsi1 in cold-sensitive rice mediates transcriptional regulatory networks and enhances resistance to chilling stress. Plant Sci. 2017;262:115–126. doi: 10.1016/j.plantsci.2017.06.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Cui X, Wang Y, Wu J, Han X, Gu X, Lu T, Zhang Z. The RNA editing factor DUA 1 is crucial to chloroplast development at low temperature in rice. New Phytol. 2019;221:834–849. doi: 10.1111/nph.15448. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Kopriva S, Bauwe H. Serine hydroxymethyltransferase from Solanum tuberosum. Plant Physiol. 1995;107:271. doi: 10.1104/pp.107.1.271. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Oliver DJ. The glycine decarboxylase complex from plant mitochondria. Annu Rev Plant Biol. 1994;45:323–337. doi: 10.1146/annurev.pp.45.060194.001543. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Bourguignon J, Rebeille F, Douce R. Serine and glycine metabolism in higher plants. In: Singh BK, editor. Plant amino acids: Biochemistry and biotechnology. New York: Marcel Dekker, Inc; 1998. pp. 111–146. [Google Scholar]

- 11.Bauwe H, Kolukisaoglu U. Genetic manipulation of glycine decarboxylation. J Exp Bot. 2003;54:1523–1535. doi: 10.1093/jxb/erg171. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Kisaki T, Imai A, Tolbert NE. Intracellular localization of enzymes related to photorespiration in green leaves. Plant Cell Physiol. 1971;12:267–273. [Google Scholar]

- 13.Wang D, Liu H, Li S, Zhai G, Shao J, Tao Y. Characterization and molecular cloning of a serine hydroxymethyltransferase 1 (OsSHM1) in rice. J Integr Plant Biol. 2015;57:745–756. doi: 10.1111/jipb.12336. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Lee B, Lee H, Xiong L. A mitochondrial complex I defect impairs cold-regulated nuclear gene expression. Plant Cell. 2002;14:1235–1251. doi: 10.1105/tpc.010433. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Zhou H, Zhao J, Yang Y, Chen C, Liu Y, Jin X, Chen L, Li X, Deng XW, Schumaker KS, Guo Y. Ubiquitin-specific protease16 modulates salt tolerance in Arabidopsis by regulating Na+/H+ antiport activity and serine hydroxymethyltransferase stability. Plant Cell. 2012;24:5106–5122. doi: 10.1105/tpc.112.106393. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Moreno JI, Martín R, Castresana C. Arabidopsis SHMT1, a serine hydroxymethyltransferase that functions in the photorespiratory pathway influences resistance to biotic and abiotic stress. Plant J. 2005;41:451–463. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-313X.2004.02311.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Ma JF, Tamai K, Yamaji N, Mitani N, Konishi S, Katsuhara M, Ishiguro M, Yoshiko M. Masahiro YA silicon transporter in rice. Nature. 2006;440:688. doi: 10.1038/nature04590. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Besson V, Neuburger M, Rebeille F, Douce R. Evidence for three serine hydroxymethyltransferases in green leaf cells. Purification and characterization of the mitochondrial and chloroplastic isoforms. Plant Physiol Biochem. 1995;33:665–673. [Google Scholar]

- 19.Zhang Y, Sun K, Sandoval FJ, Santiago K, Roje S. One-carbon metabolism in plants: characterization of a plastid serine hydroxymethyltransferase. Biochem J. 2010;430:97–105. doi: 10.1042/BJ20100566. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Mandl J, Mészáros T, Bánhegyi G, Csala M. Minireview: endoplasmic reticulum stress: control in protein, lipid, and signal homeostasis. Mol Endocrinol. 2013;27:384–393. doi: 10.1210/me.2012-1317. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Davletova S, Rizhsky L, Liang H, Shengqiang Z, Oliver DJ, Coutu J, Shulaev V, Schlauch K, Mittler R. Cytosolic ascorbate peroxidase 1 is a central component of the reactive oxygen gene network of Arabidopsis. Plant Cell. 2005;17:268–281. doi: 10.1105/tpc.104.026971. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Rana RM, Iqbal A, Wattoo FM, Khan MA, Zhang H. HSP70 mediated stress modulation in plants. In: Asea AAA, Kaur P, editors. Heat shock proteins and stress. Cham: Springer; 2018. pp. 281–290. [Google Scholar]

- 23.Kim SR, An G. Rice chloroplast-localized heat shock protein 70, OsHsp70CP1, is essential for chloroplast development under high-temperature conditions. J Plant Physiol. 2013;170:854–863. doi: 10.1016/j.jplph.2013.01.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Qi Yaocheng, Wang Hongjuan, Zou Yu, Liu Cheng, Liu Yanqi, Wang Ying, Zhang Wei. Over-expression of mitochondrial heat shock protein 70 suppresses programmed cell death in rice. FEBS Letters. 2010;585(1):231–239. doi: 10.1016/j.febslet.2010.11.051. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Junge Wolfgang, Lill Holger, Engelbrecht Siegfried. ATP synthase: an electrochemical ransducer with rotatory mechanics. Trends in Biochemical Sciences. 1997;22(11):420–423. doi: 10.1016/S0968-0004(97)01129-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Palmieri F, Pierri CL, De Grassi A, Nunes-Nesi A, Fernie AR. Evolution, structure and function of mitochondrial carriers: a review with new insights. Plant J. 2011;66:161–181. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-313X.2011.04516.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Wang L, Xu YY, Zhang C, Ma QB, Joo SH, Kim SK, Xu ZH, Chong K. OsLIC, a novel CCCH-type zinc finger protein with transcription activation, mediates rice architecture via brassinosteroids signaling. PLoS One. 2008;3:e3521. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0003521. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Reichel M, Liao Y, Rettel M, Ragan C, Evers M, Alleaume A-M, Horos R, Hentze MW, Preiss T, Millar AA. In planta determination of the mRNA-binding proteome of Arabidopsis etiolated seedlings. Plant Cell. 2016;28:2435–2452. doi: 10.1105/tpc.16.00562. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Burley SK, Xie X, Clark KL, Shu F. Histone-like transcription factors in eukaryotes. Curr Opin Struct Biol. 1997;7:94–102. doi: 10.1016/S0959-440X(97)80012-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Goddard RH, Wick SM, Silflow CD, Snustad DP. Microtubule components of the plant cell cytoskeleton. Plant Physiol. 1994;104:1–6. doi: 10.1104/pp.104.1.1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Livanos P, Galatis B, Apostolakos P. The interplay between ROS and tubulin cytoskeleton in plants. Plant Signal Behav. 2014;9:e28069. doi: 10.4161/psb.28069. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Wang C, Zhang LJ, Huang RD. Cytoskeleton and plant salt stress tolerance. Plant Signal Behav. 2011;6:29–31. doi: 10.4161/psb.6.1.14202. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Fang CX, Wang QS, Yu Y, Li QM, Zhang HL, Wu XC, Chen T, Lin WX. Suppression and overexpression of Lsi1 induce differential gene expression in rice under ultraviolet radiation. Plant Growth Regul. 2011;65:1–10. doi: 10.1007/s10725-011-9569-y. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Tantikanjana T, Rizvi N, Nasrallah ME, Nasrallah JB. A dual role for the S-locus receptor kinase in self-incompatibility and pistil development revealed by an Arabidopsis rdr6 mutation. Plant Cell. 2009;21:2642–2654. doi: 10.1105/tpc.109.067801. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Goodin MM, Zaitlin D, Naidu RA, Lommel SA. Nicotiana benthamiana: its history and future as a model for plant–pathogen interactions. Mol Plant Microbe In. 2008;8:1015–1026. doi: 10.1094/MPMI-21-8-1015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Fang CX, Yang LK, Chen WX, Li LL, Zhang PL, Li YZ, He HB, Lin WX. MYB57 transcriptionally regulates MAPK11 to interact with PAL2;3 and modulate rice allelopathy. J Exp Bot. 2020;71:2127–2141. doi: 10.1093/jxb/erz540. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Livak Kenneth J., Schmittgen Thomas D. Analysis of Relative Gene Expression Data Using Real-Time Quantitative PCR and the 2−ΔΔCT Method. Methods. 2001;25(4):402–408. doi: 10.1006/meth.2001.1262. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Clough SJ, Bent AF. Floral dip: a simplified method for agrobacterium-mediated transformation of Arabidopsis thaliana. Plant J. 1998;16:735–743. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-313x.1998.00343.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Additional file 1 Fig. S1 Subcellular localisation of OsSHMT protein in rice protoplast

Additional file 2 Table S1 Sequence of OsSHMT gene promoter from Dular. Table S2 Proteins interacted with OsSHMT in the OsSHMT transgenic A. thaliana using GFP-Trap Co-IP. Table S3 Primers used in this study

Additional file 3 Methods S1 Extraction of rice leaf protein

Additional file 4 Electronic Supplementary Material 1. Full length gel presents proteins binding on the OsSHMT-promoter in Dular

Additional file 5 Electronic Supplementary Material 2. Full length gel presents proteins binding on the OsSHMT-promoter in Lsi1-OX transgenic line

Additional file 6 Electronic Supplementary Material 3. Full length gel presents protein interactions with OsSHMT in Arabidopsis thaliana

Data Availability Statement

All data generated during this study are included in this published article and its supplementary information files, and the raw data used or analysed during the current study available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.